Abstract

Background. Poor maternal self-rated health in healthy women is associated with adverse neonatal outcomes, but knowledge about self-rated health in pregnant women with congenital heart disease (CHD) is sparse. This study, therefore, investigated self-rated health before, during, and after pregnancy in women with CHD and factors associated with poor self-rated health. Methods. The Swedish national registers for CHD and pregnancy were merged and searched for primiparous women with data on self-rated health; 600 primiparous women with CHD and 3062 women in matched controls. Analysis was performed using descriptive statistics, chi-square test and logistic regression. Results. Women with CHD equally often rated their health as poor as the controls before (15.5% vs. 15.8%, p = .88), during (29.8% vs. 26.8% p = .13), and after pregnancy (18.8% vs. 17.6% p = .46). None of the factors related to heart disease were associated with poor self-rated health. Instead, factors associated with poor self-rated health during pregnancy in women with CHD were ≤12 years of education (OR 1.7, 95%CI 1.2–2.4) and self-reported history of psychiatric illness (OR 12.6, 95%CI 1.4–3.4). After pregnancy, solely self-reported history of psychiatric illness (OR 5.2, 95%CI 1.1–3.0) was associated with poor self-rated health. Conclusion. Women with CHD reported poor self-rated health comparable to controls before, during, and after pregnancy, and factors related to heart disease were not associated with poor self-rated health. Knowledge about self-rated health may guide professionals in reproductive counselling for women with CHD. Further research is required on how pregnancy affects self-rated health for the group in a long-term perspective.

Introduction

Self-rated health is a marker for patients’ subjective assessment of their general health and well-being [Citation1,Citation2] and may be used in a broader range of situations, including risk assessment to predict morbidity and mortality [Citation1,Citation3]. The concept involves social background, physical health, and psychosocial factors [Citation1], usually rated via a single question on a five-level Likert scale ranging from excellent to very poor [Citation1,Citation2]. For women enrolled in antenatal care in Sweden, including women with congenital heart disease (CHD), data on self-rated health has been collected since 2014 [Citation4].

Approximately one in 100 children are born with CHD, making it the most common malformation among newborns. Due to improved paediatric cardiac care, 97% of all children born with CHD reach adulthood, predominantly in high-income countries [Citation5]. As a consequence, more women with CHD become pregnant, with the number expected to increase further in the coming years [Citation6]. Therefore, the reproductive health in this growing group requires increased attention.

During pregnancy, a woman’s body undergoes a series of important hemodynamic changes, although physiologic and expected, that may pose a problem in women with CHD [Citation7,Citation8]. As a result, in comparison to their counterparts without CHD, women with CHD are exposed to an increased risk of cardiovascular complications during pregnancy and childbirth, such as heart failure, arrhythmia, and thromboembolic events [Citation7,Citation9]. There are also increased risks for the foetus and child, including preterm birth (16%), low birth weight (8%), and stillbirth (1%) [Citation7,Citation9]. Moreover, previous studies have shown that poor maternal self-rated health in the general population is associated with neonatal risks, mainly low birth weight and preterm birth [Citation10].

In spite of the potential health challenges of living with CHD, the group reports a generally high quality of life [Citation11,Citation12]. However, those suffering from symptomatic heart disease assess their quality of life as worse than those without symptoms [Citation11,Citation12]. Quality of life among adults with CHD and the general population has been found to relate more closely to sociodemographic factors than to comorbidities or the severity of the cardiac condition [Citation10,Citation13]. Nevertheless, due to their experiences and potential difficulties in life, adults with CHD are at higher risk for post-traumatic stress disorder than the general population [Citation14], and pregnant women with CHD have an increased risk of postpartum emotional distress [Citation15].

Despite the impact of pregnancy and childbirth on women with CHD and the risks related to poor self-rated health among women in general, self-rated health in pregnant women with CHD is a relatively unexplored area. This study, therefore, aimed to investigate self-rated health before, during, and after pregnancy in primiparous women with CHD, as well as factors associated with poor self-rated health in these women.

Methods

Study design and selection criteria

The present study was register-based, using data from the Swedish Register of Congenital Heart Disease (SWEDCON) and the Swedish Pregnancy Register. Inclusion criteria for women with CHD were (i) diagnosed with structural CHD (at least one visit to a heart clinic aged ≥18 years), (ii) primiparity, (iii) and having given birth after 22 + 0 weeks of gestation. Controls were matched by municipality of residence, age, parity, and had given birth after 22 weeks of gestation.

Registers

SWEDCON is a longitudinal register collecting data on patients with CHD from their first diagnosis and throughout life. Examples of data in the register include diagnosis, interventions, symptoms related to heart disease, sociodemographic factors, cardiovascular drugs, and New York Heart Association functional classification (NYHA class) [Citation16]. In 2020, the register covered 15,132 individuals aged >18 years, of whom 48% were women.

The Swedish Pregnancy Register is a national quality register that has existed in its current form since 2014. It covers >98% of all births after 22 + 0 gestational weeks within 16 of the 20 Swedish health care regions participating in the register during the study period. The register consists of prospectively collected data regarding the health status of the women as well as data on the pregnancy, labour, birth, and 6–18 weeks into the postpartum period [Citation4]. The present study included data from the Swedish Pregnancy Register between 2014 and 2019.

Data collection

Upon registration at an antenatal clinic, women receive oral and written information about the Swedish Pregnancy Register. They are then encouraged to rate their current health (i.e. during the pregnancy) and, retrospectively, three months before pregnancy. Information about self-rated health after pregnancy is obtained six to 18 weeks after birth. Health status, such as, sociodemographics, age, diagnoses, BMI, self-reported history of psychiatric illness, and reproductive background are also recorded and downloaded from the electronic medical record into the register. Information about the pregnancy, labour, birth, and postpartum period are continuously transferred into the register. In addition to standard antenatal care visits, women with comorbidities or complications during pregnancy, are also followed by the specialist maternity clinic, where an individual assessment is made continuously during pregnancy.

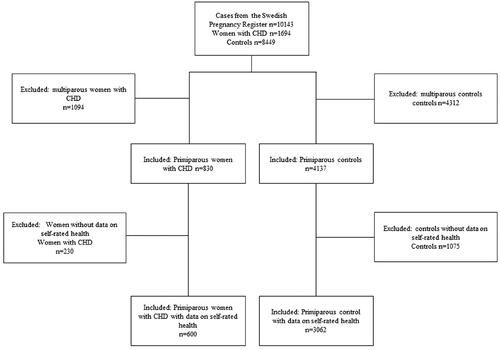

In this study, data from SWEDCON and the Swedish Pregnancy Register were merged to reveal 1694 women with structural CHD, and matched with 8449 controls. Included in the analysis are thus primiparous women where data on self-rated health before, during, and after pregnancy was obtained, ending with a final population of 600 women with CHD and 3062 controls ().

Exposure and outcomes

In the Swedish Pregnancy Register, self-rated health is graded as very good, good, neither good nor poor, poor, and very poor. In line with earlier research [Citation10,Citation17], the five levels were dichotomized into two groups: very good/good (good self-rated health) and neither good nor poor/poor/very poor (poor self-rated health). Outcomes included in the study were symptoms and limitations related to CHD, diagnosed comorbidities, obstetric complications, and sociodemographic characteristics (). From the Swedish Pregnancy Register data on comorbidities and sociodemographic information, registered at the first visits in antenatal care, and data on birth and obstetric complications, registered after delivery was collected. Because of the increased risks of moderate and severe CHD during pregnancy [Citation8], the complexity of the heart disease was classified into mild (n = 456, 76%) and moderate/severe (n = 144, 24%) according to guidelines [Citation18]. Information regarding CHD was collected by the cardiology clinic at the visit closest to delivery, which was 6–29 months (mean 26 months) before delivery for women with mild complexity and 3–9 months (mean 6 months) for those with moderate or severe complexity.

Table 1. Overview of characteristics in primiparous women with CHD and controls.

Statistical analysis

All calculations were performed using version 28 of IBM SPSS (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The data were assessed for normality, and standard descriptive statistics were applied to compare means and ratios. Maternal age and BMI were analysed as continuous variables. Univariable logistic regression was used to evaluate independent variables for potential associations with the dependent variable (self-rated health). Variables with a p-value <.1 in the univariable regression were included in a multivariable model, which was further assessed in a manual backward manner. Multi-collinearity was continuously assessed. The null hypothesis was rejected for p-values <.05.

Results

This register study included 600 primiparous women with CHD and 3062 primiparous controls, with a mean age when giving birth at 28.7 ± 4.4 years for women with CHD and 28.5 ± 4.4 years for controls (). The proportion of women who rated their health as poor was similar among women with CHD and controls before (15.5% vs. 15.8%, p = .88), during (29.8% vs. 26.8%, p = .13), and after pregnancy (18.8 vs. 17.6 p = .46) (). None of the variables related to the heart disease were associated with poor self-rated health.

Table 2. Self-rated health in primiparous women with CHD and primiparous controls.

Factors associated with poor self-rated health during pregnancy among women with CHD in the univariable logistic regression analysis were self-reported history of psychiatric illness (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.49–3.54, p = <.001) and ≤ 12 years of education (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.5, p = <.002) (). The multivariable model revealed self-reported history of psychiatric illness (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.4–3.4, p = <.001) and ≤12 years of education (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.4, p = <.007) as still associated with poor self-rated health during pregnancy (). After pregnancy, univariable logistic regression indicated higher maternal age (OR 1.0, 95% CI 1.0–1.1, p = .01) and self-reported history of psychiatric illness (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–3.0, p = .022) as associated with poor self-rated health (). The only factor that remained associated with poor self-rated health after pregnancy in the multivariable model was self-reported history of psychiatric illness (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–3.0, p = .022) ().

Table 3. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression model with poor self-rated health during pregnancy in primiparous women with CHD as the dependent variable.

Table 4. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression model with poor self-rated health after pregnancy in primiparous women with CHD as the dependent variable.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate self-rated health before, during, and after pregnancy in women with CHD compared with controls, as well as factors associated with poor self-rated health for women with CHD. The results show that women with CHD rated their health as being comparable to controls before, during, and after pregnancy.

Poor self-rated health was associated with ≤12 years of education and history of psychiatric illness. However, neither the complexity of CHD nor other factors related to CHD (e.g. symptoms and cardiovascular medication) were associated. These results also align with previous findings among adults with CHD and pregnant women without CHD, where social background factors such as low level of education, unemployment, and being a single were associated with poor self-rated health [Citation10,Citation13]. To check whether the controls’ reasons for poor self-rated health differed from the cases in this sample, analyses were also conducted for the control group, and even for them, sociodemographics were more indicative of poor self-rated health than comorbidities or obstetric complications.

In accordance with the present results, a low educational level is a well-known risk factor for poor self-rated health in the general population [Citation19], and pregnant women with poor self-rated health are also described as more likely to have a low educational level than those reporting good self-rated health [Citation20]. This study’s results, however, show that educational level is associated with poor self-rated health during pregnancy but not after pregnancy. In line with this, healthy pregnant women with low educational level show a similar pattern, where the risk of poor self-rated health decreases after pregnancy [Citation21]. Self-reported history of psychiatric illness was the only factor associated with poor self-rated health both during and after pregnancy, and this mirrors findings for pregnant women in general, with mental health problems such as depression also affecting their poor self-rated health [Citation22]. Concerning this result, it is worth noting that the significant haemodynamic changes that may primarily affect women with CHD appear later in pregnancy [Citation8], and information on self-rated health is requested at one of the first maternity care visits in early pregnancy. At that point in pregnancy, women with CHD may feel as affected by the pregnancy as any other pregnant woman. Social factors such as low educational level and psychiatric illness may influence poor self-rated health more strongly than other health related conditions perceived as common for women with CHD.

This study shows no difference in poor self-rated health between different complexities of heart lesions. Women who are highly affected by their heart disease, might have been advised not to be pregnant [Citation7]. Therefore, women with CHD who participated in the present study may be a favourable group with CHD, being able to go through a pregnancy and childbirth, and therefore the heart disease did not show association with poor self-rated health. Furthermore, the women with CHD were relatively young, and thus not yet exposed to comorbidities and complications, and previous findings confirm higher maternal age in women with CHD increases obstetric risks during pregnancy [Citation23]. Young people with chronic disease have previously been shown to struggle with, for example, relationships and parenting [Citation24]. However, mentioned research also describes those with visible chronic disease as having more struggles [Citation24], which is not the case for women with CHD, as the disease is more or less invisible.

Limitations

Only primiparous women were included in present study and that might have impacted the results positively, as earlier population-based research show associations between multiparous women and poor self-rated health [Citation21]. As in several register studies, missing data was a potential problem. However, the distribution of other factors was comparable between those with and without data, and did not obviously cause selection bias. When women with and without data on symptoms and self-rated health were controlled, there were no differences in either age, sociodemographic, obstetric complications, or factors related to heart disease. Women’s ratings of their health may have been influenced by orally reporting this to the midwives during the antenatal visits, but this would most likely have occurred similarly in both women with CHD and controls.

Conclusion

Women with CHD rated their health comparable to controls, before during and after pregnancy. Factors related to the heart disease were also not causes of poor self-rated health, instead, the factors that were of importance were ≤12 years of education and history of psychiatric illness. This new knowledge can assist professionals within maternity care in their guidance in reproductive counselling and family planning for women with CHD. As many women with CHD rated their health as good, professionals must be aware that the heart disease does not overshadow normal aspects of the pregnancy process. Further research is needed on how pregnancy in women with CHD affects self-rated health in a long-term perspective.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Ref: 2020-00701) and adhered to the principles for medical research as described in the Declaration of Helsinki [Citation25]. All women included in the Swedish Pregnancy Register are asked about participation in the register on their first visit in antenatal care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fayers PM, Sprangers MAG. Understanding self-rated health. Lancet. 2002;359(9302):187–188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07466-4.

- Bowling A. Just one question: if one question works, why ask several? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(5):342–345. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.021204.

- DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, et al. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(3):267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x.

- Stephansson O, Petersson K, Björk C, et al. The swedish pregnancy register – for quality of care improvement and research. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97(4):466–476. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13266.

- Mandalenakis Z, Giang KW, Eriksson P, et al. Survival in children with congenital heart disease: have we reached a peak at 97%? J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(22):e017704-e. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017704.

- Bottega N, Malhamé I, Guo L, et al. Secular trends in pregnancy rates, delivery outcomes, and related health care utilization among women with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019;14(5):735–744. doi: 10.1111/chd.12811.

- Haberer K, Silversides CK. Congenital heart disease and women’s health across the life span: focus on reproductive issues. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35(12):1652–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.10.009.

- Canobbio MM, Warnes CA, Aboulhosn J, et al. Management of pregnancy in patients with complex congenital heart disease: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association. Circulation. 2017;135(8):e50–e87. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000458.

- Lammers AE, Diller G-P, Lober R, et al. Maternal and neonatal complications in women with congenital heart disease: a nationwide analysis. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(41):4252–4260. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab571.

- Viirman F, Hesselman S, Wikström AK, et al. Self‐rated health before pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes in Sweden: a population‐based register study. Birth. 2021;48(4):541–549. doi: 10.1111/birt.12567.

- Berghammer M, Karlsson J, Ekman I, et al. Self-reported health status (EQ-5D) in adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2011;165(3):537–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.002.

- Moons P, Luyckx K. Quality‐of‐life research in adult patients with congenital heart disease: current status and the way forward. Acta Paediatr. 2019;108(10):1765–1772. doi: 10.1111/apa.14876.

- Apers S, Kovacs AH, Luyckx K, et al. Quality of life of adults with congenital heart disease in 15 countries: evaluating country-specific characteristics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(19):2237–2245. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.477.

- Liu A, Diller G-P, Moons P, et al. Changing epidemiology of congenital heart disease: effect on outcomes and quality of care in adults. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;20(2):126–137. doi: 10.1038/s41569-022-00749-y.

- Freiberg A, Beckmann J, Freilinger S, et al. Psychosocial well-being in postpartum women with congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2022;12(4):389–399. doi: 10.21037/cdt-22-213.

- Bodell A, Björkhem G, Thilén U, et al. National quality register of congenital heart diseases – can we trust the data? J Congenit Heart Dis. 2017;1(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40949-017-0013-7.

- Schytt E, Waldenström U. Risk factors for poor self-rated health in women at 2 months and 1 year after childbirth. J Womens Health. 2007;16(3):390–405. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0030.

- Baumgartner H, de Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(6):563–645. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554.

- Vonneilich N, Lüdecke D, von Dem Knesebeck O. Educational inequalities in self-rated health and social relationships – analyses based on the European social survey 2002-2016. Soc Sci Med. 2020;267:112379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112379.

- Teoli DA, Zullig KJ, Hendryx MS. Maternal fair/poor self-rated health and adverse infant birth outcomes. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(1):108–120. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2013.862796.

- Khalaf A, Johansson M, Ghani RMA, et al. Self-rated health in swedish pregnant women: a comprehensive population register study. British Journal of Midwifery. 2022;30(6):306–315. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2022.30.6.306.

- Lee E, Song J. The effect of physical and mental health and health behavior on the self-rated health of pregnant women. Healthcare. 2021;9(9):1117. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9091117.

- Kloster S, Andersen AMN, Johnsen SP, et al. Advanced maternal age and risk of adverse perinatal outcome among women with congenital heart disease: a nationwide register‐based cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2020;34(6):637–644. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12672.

- Pinquart M. Achievement of developmental milestones in emerging and young adults with and without pediatric chronic illness—A meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39(6):577–587. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu017.

- World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194.