ABSTRACT

Sub-standard living conditions among migrant workers have become a structural feature all over Europe. Although this has attracted the attention of many scholars, there is a lack of studies on the complex relations between various stakeholders in governing housing. This study fills this gap by analysing this housing issue from a governance network perspective. Through an analysis of policy documents and interviews with twenty-one stakeholders, we investigated institutional and strategic complexities. The results show that decision-making is complicated by unclear institutional accountability patterns and the diverging strategic interests of various stakeholders. The interrelationship between the loosely defined institutional setting (structure) and the varying interests of involved actors (agency) has led to a policy impasse that is difficult to breach. We argue that a reconsideration of existing accountability patterns is needed to reduce sub-standard housing conditions among migrant workers in the Netherlands.

Introduction

Since the gradual expansion of the European Union (EU) to Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries after 2003, annual intra-EU mobility has steadily increased. Despite the advantages of intra-EU mobility (European Commission Citation2021), the increasing demand for CEE labour migration has been accompanied by increasing reports of sub-standard housing conditions in multiple receiving countries, and the European Policy Institute (Citation2020) even concluded that sub-standard living conditions among migrant workers have become a structural feature all over Europe. The Netherlands faced the largest relative increase in intra-EU mobility (9%) between 2017 and 2018 in the EU (European Commission Citation2021), and annual intra-EU inflows have increased from just over 25,000 in 2004 to almost 125,000 in 2019 (Statistics Netherlands Citation2021b). To meet labour demands, Statistics Netherlands expects this trend to continue. However, like in other receiving countries, a recent report commissioned by the Dutch government concluded that CEE migrant workersFootnote1 in the Netherlands often live in precarious housing conditions (Booster Team Migrant Workers Citation2020). The report proposed fifty recommendations to improve the living conditions of migrant workers. Yet, a decade before this publication, similar recommendations were put forward by another parliamentary committee in the Netherlands (undefinedCommittee Lessons from Recent Labour Migration Citation2011). Therefore, a significant policy impasse has arisen (Susskind and Cruikshank Citation1987).

Previous studies that explored complications in the provision of housing for particular target groups have mostly done so by studying the development of housing systems. Kemeny (Citation2001) argues that housing systems are shaped within particular welfare regimes. These regimes are a result of economic, political, social, and ideological power balances and it is assumed that the interplay between these power balances determines how housing is organized (Stephens Citation2020). Consequentially, cross-country differences in power balances offer an explanation for diverging housing systems (Kemeny Citation2006). Yet, the housing systems perspective disregards the diverging interests and perceptions among involved actors within countries that make the current policy problem especially “wicked” (Poppelaars and Scholten Citation2008). However, this is becoming more and more relevant in the housing domain due to increasing interdependencies between public, private, and civil stakeholders (Mullins and Rhodes Citation2007). In addition, the provision of housing for migrant workers involves interdependencies between actors across multiple regimes, such as the welfare regime (Esping-Andersen Citation1990), migration regime (Sainsbury Citation2006), and housing regime (Kemeny Citation2001). Since the housing systems perspective overlooks these interdependencies, it is unable to identify the causes of the policy impasse.

As an alternative, this study develops a governance network perspective to gain more insight into the interaction process in which the provision of housing for migrant workers is negotiated. By focusing on the social relations among involved actors, this perspective enables us to shed light on the interdependencies and the diverging interests and perceptions among involved stakeholders (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016). Moreover, it enables us to study the duality of structure; institutional arrangements (structure) set the framework in which stakeholders pursue their strategic interests, while this pursuit (agency) subsequently transforms institutional arrangements (Giddens Citation1984). Institutional arrangements in the provision of housing for migrant workers are investigated by looking into accountability patterns. Within the field of public administration, accountability patterns have been considered as a crucial institutional arrangement affecting the actions of decision makers (Bovens Citation2010; Papadopoulos Citation2007; Yang Citation2012). The agency of stakeholders is investigated by studying the strategic interests and corresponding strategies of involved actors (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016). By explicitly paying attention to the interconnection between structure and agency within the governance network, we try to shed light on the mechanisms underlying the current policy impasse.

While the suitability of network perspectives in the field of housing has been underlined earlier, they have not yet emerged as a widely used theoretical approach (Mullins and Rhodes Citation2007). We aim to contribute to the application of network approaches in the housing domain by developing a governance network perspective that takes the interrelationship between the institutional setting and the strategic interests of stakeholders into account. In doing so, we also aim to contribute to the existing governance network literature by perceiving accountability as an endogenous phenomenon (Yang Citation2012); accountability structures constitute the institutional setting in which actors make decisions, while concurrently, the actions of actors (agency) transform the accountability structure. Therefore, we build on earlier frameworks that studied institutional and strategic complexities separately (e.g. Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016). Through our framework, we intend to identify points of intervention to reduce housing precarity among migrant workers in the Netherlands, as well as the wider EU. Recent studies have analysed the institutional factors underlying the vulnerable working conditions of migrant workers across the EU (Berntsen and Skowronek Citation2021; Lombard Citation2023; Palumbo, Corrado, and Triandafyllidou Citation2022) and the factors underlying the insecure housing trajectories of individual migrant workers (Manting, Kleinepier, and Lennartz Citation2022; Szytniewski and van der Haar Citation2022; Ulceluse, Bock, and Haartsen Citation2022). We build on these studies by studying housing precarity among migrant workers through a governance network perspective.

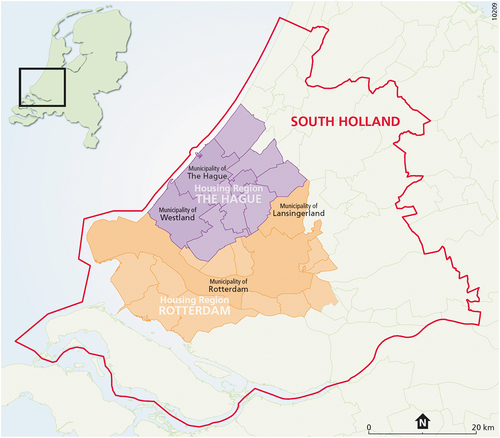

The framework is applied to the Rotterdam/The Hague Region in the province of South Holland. The province of South Holland hosts the largest number of migrant workers in the Netherlands and most of them reside in the Rotterdam/The Hague Region (Statistics Netherlands Citation2021a). They are mainly employed in labour-intensive industries such as the horticultural, logistics, meat processing, and construction sector. While these industries are mostly situated in the less urbanized areas of the region, migrant workers mainly find housing in urban areas due to the supply of private housing (PBLQ Citation2020). Therefore, the facilitation of housing for migrant workers is a regional policy issue. The governance network was studied through an analysis of policy documents and debates, by attending public conferences, and by conducting twenty-one interviews with involved stakeholders between September 2021 and January 2022.

Stakeholders Involved in the Provision of Housing for Migrant Workers in the Rotterdam/The Hague Region

The majority of migrant workers (60%) coming to the Netherlands find employment through an employment agency. In some sectors, such as the horticultural sector, this percentage is higher (90%). These employment agencies often offer “package deals” to migrant workers, consisting of a place to work, lodging, healthcare, and transport to and from work (Booster Team Migrant Workers Citation2020). Most migrant workers are lodged in the existing housing stock (SNF Citation2022). Often employment agencies rent a dwelling from a private proprietor and subsequently sublet it to multiple migrant workers. Migrant workers without a package-deal contract may also directly find lodging from a private proprietor. Due to the increasing scarcity in the housing market, lodging for migrant workers is increasingly developed outside the regular housing stock. Employment agencies may arrange housing in holiday parks, temporary container dwellings, or specifically developed campus-like residential buildings (Booster Team Migrant Workers Citation2020). They can develop such sites themselves or rent a site from a specialized company.

Private stakeholders that want to develop housing for migrant workers or that want to arrange housing in the existing stock are bound to regulations. These regulations are determined by public stakeholders on multiple levels of governance, namely, the national government, the province of South Holland, the housing regions Rotterdam and The Hague, and individual municipalities in the region. The development of housing has to a large extent been decentralized in the Netherlands. Through the development of laws and regulations, the national government determines the capabilities and juridical instruments of actors at other levels of governance. While the previous cabinet argued that governmental intervention in the housing market was no longer necessary,Footnote2 the current government has firm ambitions regarding the development of housing for vulnerable groups such as migrant workers. Next to stimulating municipalities financially to accelerate the development of housing, the government has plans for obligatory regional visions on the provision of housing for vulnerable groups. In these visions, municipalities would need to map the housing demand of migrant workers in the region and make binding performance agreements (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations Citation2022).

Similar to the national government, the province influences the provision of housing by setting specific regulations that municipalities need to follow. For example, the province determines in which areas the development of housing is allowed (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations Citation2021). In exceptional cases, the province has the opportunity to actively steer municipal decision making but such instruments are avoided as much as possible. Instead, the province tries to reach agreements with municipalities through deliberation (Randstad audit office Citation2019). At the regional level, municipalities collaborate in regional housing partnerships. The area that is studied consists of two housing regions, the Rotterdam region, consisting of the municipality of Rotterdam and thirteen surrounding municipalities, and the The Hague region, consisting of The Hague and eight surrounding municipalities (see ). The national government sees regional cooperation as essential in the provision of housing for migrant workers because their daily urban systems transcend municipal borders; they may live in a particular municipality due to the accessibility of housing while working elsewhere in the region due to the availability of work. Additionally, a lack of cooperation may lead to spill over effects. If one municipality allows the development of housing for migrant workers while other municipalities in the region do not, that municipality may attract migrant workers from all over the region. Housing regions are less formalized than other levels of governance and are not directly elected but composed of municipally elected representatives. Decisions within the housing regions need formal ratification by the councils of individual municipalities. Within the framework set by higher levels of governance, municipalities decide where, when, and how housing for migrant workers is facilitated. Municipalities can set enforceable guidelines about the development of new housing sites for migrant workers and can regulate their housing stock by implementing rules on subletting (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations Citation2021).

Since migrant workers often find housing through package deals with employment agencies, trade unions are involved as civil stakeholders. Through collective labour agreements, they negotiate with employer organizations about the requirements of migrant worker housing quality marks such as the notice period after which someone has to leave employer-provided housing, the number of square metres per person, and the number of persons per bedroom (Federation of Dutch Trade Unions Citation2020). Public stakeholders are unable to intervene in these negotiations (Government of the Netherlands Citation2021).

Theoretical Background

The current study investigates the provision of housing for migrant workers through a network governance perspective. Klijn and Koppenjan (Citation2016, 5–6) distinguish between four dominant meanings of the term “governance” across the literature. The term has been used to describe (1) a properly functioning government; (2) a form of governing where the role of the government is to steer rather than to row (new public management); (3) a form of governing that involves interaction across actors at various levels of government (multi-level government); and (4) a form of governing that takes place in networks of various public, private, and civil actors (network governance).

The current study is in line with the fourth conceptualization of governance. We believe this is apt as throughout Europe, the role of central governments in the provision of housing has decreased. This has involved the decentralization of tasks and responsibilities to other layers of government (Doherty Citation2004; van Bortel Citation2009). In addition, the relation between public and private stakeholders has changed since the 1980s. There used to be a hierarchical relation between public and private stakeholders; public stakeholders developed blueprints that private stakeholders implemented. Currently, the provision of housing occurs in an interactive policy network with collaboration and contracts between public and private stakeholders (Verhage Citation2003). Additionally, local governments are increasingly dependent upon private investments because of decreasing generic government budgets (Kokx and Van Kempen Citation2010).

This shift towards governance has resulted in increasingly complex interaction processes between public, private, and civil actors with diverging interests and perceptions (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016). These interaction processes occur in governance networks which have been conceptualized variously across the literature, but conceptualizations generally emphasize the involvement of public, private, and civil stakeholders in decision making processes (see, for example, Blanco, Lowndes, and Pratchett Citation2011, 299; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2007, 8–11). We broadly define governance networks as “networks of enduring patterns of social relations between actors involved in dealing with a problem, policy, or public service” (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016, 4). Other scholars have contrasted decision making within governance networks with decision making through hierarchical steering and competitive market dynamics (Sørensen and Torfing Citation2005). Our conception is not confined to networked forms of governance as they build on rather than replace other forms of governance (Driessen et al. Citation2012). Yet, as described in the previous section, the involved stakeholders are to a large extent interdependent. Because of these interdependencies, cooperation is required to enable collective action (Van Bueren, Klijn, and Koppenjan Citation2003). Klijn and Koppenjan (Citation2016) argue that the absence of collective action can be explained by different types of complexity within governance networks. The current study focuses on conflicts within the institutional and strategic domain and on the interrelationship between the two domains.

Institutional Dimension

Institutions can be defined as “systems of rules that structure the course of actions that a set of actors may choose” (Scharpf Citation1997, 38). Within these institutions, rules are perceived as “fixed and generalizable procedures for interaction” (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016, 105). Due to the diversity of involved actors in governance networks, they originate from different institutional backgrounds. Consequentially, actors within a governance network may adhere to a diverging set of rules and this may result in institutional complexity (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016).

We study the institutional dimension by investigating accountability patterns. Accountability is defined as: “a relationship between an actor and a forum, in which the actor has an obligation to explain and to justify his or her conduct, the forum can pose questions and pass judgement, and the actor may face consequences” (Bovens Citation2007, 450). Since institutions form a system of rules that structure interactions processes, institutions define the roles and responsibilities of the actors. Because accountability means being held responsible, accountability patterns can reveal both the written and unwritten rules within a particular institutional setting. Accountability patterns are seen as a mechanism affecting the behaviour of stakeholders within the governance network that ensure that decision-makers behave responsively anticipating the costs of unresponsive behaviour (Bovens Citation2010; Papadopoulos Citation2007). Our definition of accountability contrasts with conceptualizations of accountability as a virtue that is to be evaluated (Bovens Citation2010). This latter conceptualization of accountability has received considerable attention within the literature and many studies have emphasized tensions between networked forms of governance and the ideal of “democratic accountability” (e.g. Aarsæther et al. Citation2009; Esmark Citation2007; Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2012; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2005). However, this normative discussion falls outside of the scope of the current study.

Issues within the institutional dimension may arise due to accountability excesses or deficits. Accountability excesses occur when a dysfunctional mixture of accountability mechanisms is in place. An actor may, for example, be expected to justify their conduct to multiple forums that use conflicting criteria to evaluate conduct. In contrast, accountability deficits occur when accountability arrangements are lacking. This occurs when an actor has no obligation to explain and justify conduct or when a forum is unable to pass judgement (Bovens Citation2007). Because accountability mechanisms affect the behaviour of stakeholders, they can help in illuminating the mechanisms underlying the current policy impasse.

A distinction can be made between three accountability patterns, namely, vertical, horizontal, and public-private (Kang and Groetelaers Citation2018). In a vertical accountability pattern, the forum wields formal power over the actor (Bovens Citation2007). This is the case when there is a hierarchical relationship between an actor and a forum, which may exist between governments at different vertical layers. An example of such a hierarchical relationship is the ability of provinces to intervene in municipal decision making if municipalities are neglecting their responsibilities (Randstad audit office Citation2019). Such a relation resembles the notion of “government” as a formalized approach to steering the public domain (Edelenbos and Teisman Citation2008). Increased decentralization and privatization have led to a decrease in vertical accountability patterns and an increase in horizontal and public-private accountability patterns.

The second pattern is horizontal accountability. In contrast to vertical accountability, horizontal accountability refers to a situation where the accountee is not hierarchically superior to the accountor (Schillemans Citation2011). This is the situation when public stakeholders at the same level of governance account to each other. In such situations, formal obligations to render account are often missing and accounting occurs voluntarily; it is rendered due to a morally felt obligation (Bovens Citation2007). This notion of accountability is more fluid and stakeholders negotiate with each other on the subject of accountability (Kang and Groetelaers Citation2018). Inter-municipal agreements regarding the provision of housing in a region are an example of a horizontal accountability pattern in the Netherlands. These agreements are reached through deliberation (Klok et al. Citation2018; Levelt and Metze Citation2014). Municipalities can pass judgement on each other but are unable to implement formal penalization.

Lastly, accountability patterns exist between public and private stakeholders. With the shift from a providing state to an enabling state, the relationship between public and private stakeholders has changed. These developments have resulted in increasingly reciprocal accountability patterns. On the one hand, public parties induce private parties to behave in a socially desirable way (Kang and Groetelaers Citation2018). Municipalities can, for example, compel developers to follow particular regulations in the development of housing for migrant workers and municipalities may penalize developers that violate these regulations. On the other hand, private parties can urge public stakeholders to provide a “good business climate” by threatening them with the prospect that they will otherwise take their investments elsewhere (Harvey Citation1989). Employer organizations may, for example, put pressure on public stakeholders to implement particular policy measures through media campaigns (Jacobs, Kemeny, and Manzi Citation2003). Although public parties are formally accountable to their voters, the increasing dependency of public parties on the resources of private parties may have changed this situation (Papadopoulos Citation2010). gives a schematic overview of the three types of accountability patterns in the current study. Since public-private accountability may involve both vertical and horizontal patterns of accountability, it is displayed as a diagonal pattern.

Strategic Dimension

Decreasing hierarchical accountability patterns in the provision of housing for migrant workers have led to increasing space for negotiation within the governance network (Haffner and Elsinga Citation2009). However, stakeholders have diverging perceived strategic interests which they base on “the beliefs, images, and opinions that they have of their environment, the problems and opportunities within it, the other actors involved, and their dependencies upon them” (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016, 76). Rhodes (Citation2007) argues that public, private, and civil stakeholders evaluate their environment based on different criteria. While economic considerations form an important decision factor for developers, socio-political pressures may be decisive for public stakeholders. Related to this, public stakeholders on different levels of governance can have conflicting interests and tensions may arise when nationally set policies do not align with local interests (Kokx and Van Kempen Citation2010). Previous research found major differences of opinion among European, national, and local governments regarding the economic and socio-political consequences of CEE migration (Engbersen et al. Citation2017). Within the field of migration studies, there has been an increasing interest in the local dimension of migration and diversity. This “local turn” involves the acknowledgement that governance challenges associated with migration usually manifest themselves at the local level (Caponio, Scholten, and Zapata-Barrero Citation2019; Myrberg Citation2017; Schiller and Çağlar Citation2009). In addition, it is underlined that the challenges that local governments face are dependent upon local specifics, and because of that, local governments have their own agendas (Zapata-Barrero, Caponio, and Scholten Citation2017). For example, Money (Citation1997) argues that rapid increases in the number of immigrants may cause local opposition, whereas local demand for immigrant labour may lead to local support for immigration.

Despite diverging interests, actors within a governance network are interdependent. For this reason, stakeholders employ strategies in pursuit of their interests (Rhodes Citation2007). Strategies can be targeted at three components of the decision-making process (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016). First, they can be aimed at influencing the perceptions and behaviour of other actors in the network. Through lobbying, private parties may try to influence public decision-making (Van Bueren, Klijn, and Koppenjan Citation2003). Second, strategies can be aimed at the content of problem formulations and the solutions considered within the network. For instance, municipalities in the Rotterdam/The Hague region organized a summit in 2011 to raise public awareness and attention to the local consequences of CEE migration (Snel, van Ostaijen, and 't Hart Citation2019). Third, strategies may be aimed at the interaction process in which a particular issue is discussed. As an example, stakeholders that are dissatisfied with current policies may search for another setting to present alternative policy proposals. Pralle (Citation2003) refers to this as “venue shopping”. Local governments that are unable to achieve certain policy preferences at their own level can try to move the discussion to another level of government (Scholten et al. Citation2018). Another way to influence the interaction process is to stall decision-making. Within a regional government, particular municipalities may have an interest in waiting for better opportunities or in being excluded from decision-making. Particular stakeholders may have an interest in maintaining the status quo (Haffner and Elsinga Citation2009; Levelt and Metze Citation2014).

The Interrelationship Between the Institutional and Strategic Dimension

Following the previous, the provision of housing for migrant workers is negotiated within a governance network that involves multiple types of accountability patterns and stakeholders with diverging interests and strategies. However, the institutional and strategic dimension are not independent but mutually impact each other (Yang Citation2012). In line with structuration theory (Giddens Citation1984), accountability patterns within the institutional dimension affect the behaviour of actors as they base their decisions on the institutional setting they acknowledge (Bovens Citation2010; Healey and Barrett Citation1990). Simultaneously, stakeholders acknowledge particular accountability patterns while disregarding others and this process transforms the existing accountability structure. A schematic overview of the interrelationship between agency and structure is shown in .

Due to the interrelationship, accountability should not be treated as an exogenous factor but as an endogenous phenomenon. By perceiving it as an endogenous phenomenon, it can be investigated how accountability is produced and reproduced by stakeholders (Yang Citation2012). The production of accountability can be seen as an ongoing political process where stakeholders pressure each other and where power plays a vital role. Particular stakeholders gain the right to hold other stakeholders to account while other stakeholders do not gain this right (Etzioni Citation1975). According to Torfing et al. (Citation2012), governance networks are ridden with power struggles. Yet, the perspective that the conception of accountability structures can also be conceived as a power struggle has only received scant attention across the literature (Yang Citation2012). However, the production and reproduction of particular accountability structures may be an important means to exert power.

Methods

The current study is based on a combination of desk research and semi-structured interviews with involved stakeholders. Relevant documents, debates, and conferences were identified by searching for keywords in databases of the national government, the province of South Holland, and municipalities in the region.Footnote3 Subsequently, these data were used to identify relevant publications by private and civil stakeholders. In total, 155 policy materials were consulted and an overview of twenty principal materials can be found in Appendix A. We analysed the data by linking it to issues relating to our theoretical framework.

Concurrently, interview participants were identified based on the used material. Actors who were involved in public discussions about the topic were personally invited for an interview. We strived for a selection of public, private, and civil stakeholders representational of the governance network. Public stakeholders at the national, provincial, regional, and municipal level were included. We included rural (Lansingerland and Westland) and urban (Rotterdam and The Hague) municipalities from both regions and the position of other municipalities was discussed with stakeholders at the regional level. On the private level, we conducted interviews with representatives of employer organizations and a large employment agency, as these two stakeholder types form the basis of the migration industry (McCollum and Findlay Citation2018). On the civil level, we interviewed a representative of a local grassroots organization in The Hague, as well as a trade union with a national campaign for the improvement of the position of migrant workers in the Netherlands. gives an overview of all participants,Footnote4 a total of twenty-one stakeholders were interviewed between September 2021 and January 2022. The interviews lasted for approximately one hour and were conducted both offline and online due to COVID-19 regulations.

Table 1. Overview of interview participants.

Interviews were structured based on the developed theoretical framework, but each interview guide was tailored to individual stakeholders on the grounds of desk research and earlier interviews. At the beginning, the institutional dimension was discussed with stakeholders. They were asked in which arenas they discuss the provision of housing for migrant workers, what sorts of decisions are made in these arenas, and whether they believe other stakeholders are currently taking sufficient responsibility. After discussing the institutional dimension, the focus of the interview shifted to the strategic dimension. In this part of the interview, stakeholders were asked about their strategic interests and the strategies they employ to influence other actors.

Interview data were initially coded based on the institutional and strategic dimension. After that, codes in the institutional dimension were subdivided into three types of accountability patterns based on earlier research (Kang and Groetelaers Citation2018): vertical, horizontal, and public-private. In the strategic dimension, a distinction was made between three types of interests: economic interests, socio-political interests, and interests in the status quo (Haffner and Elsinga Citation2009; Kokx and Van Kempen Citation2010; Levelt and Metze Citation2014; Rhodes Citation2007). These strategic interests became apparent through an abductive inquiry that involved an analysis of the empirical data and existing literature (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow Citation2013, 28). In other words, the three types of interests were identified by going back and forth between the empirical data and the existing literature. To enhance the validity of our findings, preliminary results of the analysis were shared with two experts in the fieldFootnote5 (Creswell and Miller Citation2000).

Results

Institutional Dimension: Public and Private Accountability Deficits

During the interviews, it became clear that stakeholders mostly agreed on a particular set of recommendations to improve the housing conditions of migrant workers put forward by the Booster Team Migrant Workers (Citation2020). While the stakeholders to a substantial extent agreed on potential solutions, they had conflicting perceptions about the desirability of different accountability arrangements. These conflicting perceptions are illustrated through the three earlier described accountability patterns.

Horizontal Public Accountability

In the Netherlands, municipalities are responsible for their own housing stock. However, leaving the facilitation of sufficient housing for migrant workers as a local responsibility has led to an unfair situation according to stakeholders in Rotterdam and The Hague. Due to the supply of affordable private housing in the two cities, investors have bought up housing in inner-city neighbourhoods. A policy expert in Rotterdam (R10) argued: “The problem is that only 21% of the migrant workers living in Rotterdam work within municipal boundaries (…) it would be nice if the municipalities where they work take responsibility for housing”.

Westland and Lansingerland are the two municipalities in the region where the largest number of migrant workers work. Aldermen in both municipalities agree that they have a responsibility in the provision of housing for migrant workers (R11, R13). However, the Lansingerland alderman sees the provision of sufficient housing for migrant workers as a responsibility for all municipalities in the region. The jobs that migrant workers fill contribute to the provision of services in the region. For example, most supermarkets in the region are supplied by distribution centres in Lansingerland (R13). Due to the high number of migrant workers working in Lansingerland they cannot facilitate housing for all of them, and she noted that: “there are also a lot of municipalities [in the region] that simply do not want to facilitate housing at all” (R13). Thus, municipalities negotiate about the horizontal accountability structure (Kang and Groetelaers Citation2018); while Rotterdam and The Hague argue that Westland and Lansingerland should do more, Lansingerland argues that other municipalities in the region should do more.

Vertical Public Accountability

Actors in Rotterdam, The Hague, and Lansingerland agree that coordination from higher levels of government is necessary. A policy expert in The Hague (R8) pled for more coordination from the province and argued that in her opinion “the province acts too reserved about this”. While stakeholders in Rotterdam (R10) and Lansingerland (R13) pled for discussing the issue within their housing region: “We are now working on putting this on the agenda at the regional tables and we want to organize discussions about the topic there. Unfortunately, this has not yet succeeded” (R10).

Stakeholders at the province were not willing to take a coordinative role and argued that: “we believe that every municipality has a responsibility and that it should be discussed within a region” (R4). To stimulate regional cooperation, they have asked all housing regions to develop a vision for the provision of housing for migrant workers (R4, R7).

Hence, the province sees a major role for the housing regions, however, the chair of the housing region Rotterdam (R6) has reacted with restraint to this task: “At a certain point we said: ‘We really cannot take it anymore’. Partly also because it is not a problem for the entire region and for every city.” Similarly, a policy expert (R7) at the housing region Rotterdam argued that it is not their responsibility to make decisions about the distribution of migrant workers: “We have a voluntary partnership; you shouldn’t push such a mandatory distribution discussion to it”. Consequently, in their regional housing vision, they stated that their “ambition is the sum of what the municipalities themselves think is necessary.” According to R7, municipalities within the region are unable to reach an agreement because “if you want to force something down someone’s throat, but he keeps his mouth shut, the discussion stops”. In line with this, a policy expert in The Hague said: “if you talk about numbers, you will not reach an agreement” (R8). For that reason, the municipalities in The Hague housing region decided to turn to an external consultancy agency.

While multiple municipalities in the Rotterdam/The Hague region have pled for increased vertical coordination, it remains difficult to reach regional agreements. Neither the province nor the two housing regions seem to be capable or willing to take a coordinative role, this has resulted in an absence of vertical accountability patterns (Bovens Citation2007).

Public-Private Accountability

Public stakeholders did agree on another solution to increase the provision of housing for migrant workers. According to them, employers that hire migrant workers “also have a responsibility in organizing proper housing” (R13). Public stakeholders argued that employers are currently not taking sufficient responsibility. In addition, R7 and R13 argued that employers deliberately leave the provision of housing to municipalities.

Despite agreement among public stakeholders that private stakeholders should take more responsibility, they are not legally obliged to facilitate housing. Therefore, municipalities can only induce them to behave in a socially desirable way (Kang and Groetelaers Citation2018) through moral appeals. An issue for Rotterdam and The Hague is that they do not have an overview of local employers that employ migrant workers (R8, R9). Moreover, most migrant workers living in Rotterdam and The Hague work in other municipalities, a policy expert in Rotterdam (R9) argued that this “makes it difficult to conduct a one-on-one conversation” with a specific employer.

Another factor that complicates private accountability is that approximately 60% of the migrant workers working in the Netherlands work via employment agencies (Booster Team Migrant Workers Citation2020). Moreover, companies sometimes outsource activities to other companies. The largest e-commerce company in the Netherlands has, for example, outsourced distribution to a specialized company. When R2 addressed the e-commerce company about the housing conditions of migrant workers working for their company, they said that they were not the employer of these migrant workers and that they should not be addressed. When the company specialized in logistics was addressed, they said that they were not responsible because the migrant workers were employed by an employment agency. Therefore, it is difficult to link housing demand to a specific company.

While public stakeholders agreed that private stakeholders should take more responsibility for facilitating sufficient housing for migrant workers, private stakeholders point in the opposite direction. They argue that municipalities are responsible for housing shortages for migrant workers. According to them, municipalities are often unwilling to facilitate housing for migrant workers, and this hinders development (R14, R15, R19). For private developers, it is often unclear which demands migrant worker housing should meet and this makes it difficult to obtain a permit (R4, R15). Consequentially, only 10–15% of the new housing initiatives for migrant workers are currently realized according to a study by Greenports Nederland (R15).

Strategic Dimension: Clashing Interests

Due to the lack of functioning accountability mechanisms, stakeholders can pass housing responsibilities onto others. This accountability deficit enables stakeholders to pursue their strategic interests by employing particular strategies. By going back and forth between the existing literature (Haffner and Elsinga Citation2009; Kokx and Van Kempen Citation2010; Levelt and Metze Citation2014; Rhodes Citation2007) and the empirical data, we made a distinction between three main types of interests, namely economic interests, socio-political interests, and interests in the status quo.

Economic interests

Multiple stakeholders have economic interests in the provision of housing for migrant workers. Housing is a prerequisite for employers and employment agencies to attract migrant workers (R11, R14, R15). A shortage of housing in the Netherlands may be a cause for migrant workers to choose another country (R14, R17).

To prevent expanding labour shortages, the development of housing for migrant workers is in the interest of private parties. They employ multiple strategies to pursue this interest. One strategy is to raise the urgency of the matter. R15 said that the primary concern of Greenports Netherlands is that “that the issue remains in the spotlight”. This can be achieved by emphasizing the importance of labour migration. During the interviews, multiple stakeholders underlined that migrant workers are essential for the Dutch economy (R14, R15, R17, R18, R19). Another approach to raise the urgency is to emphasize current housing shortages. For example, one private foundation estimated the housing shortage for migrant workers at 120.000–150.000 (Expertise Centre Flexible Living Citation2019).

An alternative strategy that private stakeholders employ is to lobby for their solutions at public stakeholders. The development of housing sites for migrant workers is hindered by the lack of municipal regulations (R15). In Westland and Lansingerland, a policy framework for the development of migrant worker housing was formulated after a plea from the horticultural sector and employment agencies (R13, R17). Relatedly, multiple private parties have pled for an obligation for all municipalities to facilitate housing for a particular number of migrant workers because not all municipalities are willing to facilitate housing. In their view, the national government and the province should maintain this municipal obligation (R14, R15, R19). Private parties publicly plea for this solution by publishing white papers (Greenports Netherlands Citation2021; Work Force Citation2021) and by speaking with national politicians (Committee of Social Affairs and Employment Citation2021).

Next to private stakeholders, particular public stakeholders also have an economic interest in the facilitation of housing for migrant workers. The local economies of Westland and Lansingerland depend upon labour migration (R11, R13). For these municipalities, it is becoming increasingly important to facilitate housing for migrant workers, because housing shortages may stimulate them to choose another country of destination (R13) or to remain in their country of origin (R11).

Both municipalities are actively stimulating the development of housing for migrant workers. According to the former mayor of Westland, many plans were not realized in the past due to local resistance (R19). However, the current alderman said that they “are really making progress, especially since last year” (R11). One aspect that contributed to this is that Westland and Lansingerland are increasingly granting permission to develop housing for migrant workers via the use of temporary permits. These permits are easier to issue and can be granted directly by the executive board of a municipality and do not require voting in the municipal council (R11). Another strategy to prevent local resistance has been to facilitate the development of housing for migrant workers outside the built environment (R4, R13). So, the local labour demand has resulted in political support for immigration (Money Citation1997).

Socio-Political Interests

In contrast to municipalities that underline economic interests, the municipalities of Rotterdam and The Hague emphasize two types of externalities resulting from labour migration. The first externality that both cities emphasize is that the provision of housing for migrant workers has detrimental effects on particular neighbourhoods. Due to the comparatively large and affordable private housing stock in the two cities, investors buy single-family dwellings in these neighbourhoods and sublet them to migrant workers, causing pressure on the local housing market (Municipality of Rotterdam Citation2021; Municipality of The Hague Citation2020; R6). In addition, it is argued that the influx of migrant workers damages the social cohesion of already vulnerable neighbourhoods (R8). Another issue for the two cities is that migrant workers are increasingly found to be living in overcrowded dwellings, resulting in unsafe situations and local nuisances such as noise disturbances (R8, R9). Lastly, commuting migrant workers cause traffic congestion in inner-city neighbourhoods (Municipality of The Hague Citation2020). The second externality the two cities draw attention to are the precarious housing conditions of migrant workers. The Municipality of Rotterdam (Citation2021) has, for example, developed a policy program named “Working on a dignified existence”. The goal of the program is to improve the living conditions of migrant workers in Rotterdam. These two externalities have put the topic on the local political agenda. In recent debates in the municipal councils of Rotterdam and The Hague, multiple resolutions have been proposed to improve the societal position of migrant workers (Of Rotterdam Citation2021b; Municipality of The Hague Citation2021).

Hence, the two cities have an interest in reducing perceived neighbourhood nuisances and improving the housing conditions of migrant workers. This has resulted in two types of strategies. First, they are actively trying to regulate their housing stock by restricting investors from buying up and subletting new dwellings, increasing the capacity of departments enforcing regulations, and lobbying at the national government for more regulatory instruments (Municipality of The Hague Citation2020; Municipality of Rotterdam Citation2021). Second, the municipalities point at surrounding municipalities by arguing that they are confronted with the burdens of labour migration, while the economies of surrounding municipalities reap the benefits. The two cities have explicitly included lobbying for a “fair” distribution of migrant workers over the region in their public policy (Municipality of The Hague Citation2019; Municipality of Rotterdam Citation2021). Another strategy through which The Hague strives for a “fair” distribution is by lobbying for a policy change at the provincial level that would make it obligatory for municipalities in the region to make plans about the provision of housing for migrant workers before the settlement of a new company (Municipality of The Hague Citation2021). The latter two strategies show that the cities search for solutions at other levels of government (Pralle Citation2003).

Interest in the Status Quo

Whereas municipalities with economic and socio-political interests have an interest in changing the current state of affairs, this is less pertinent for other municipalities in the region. A consultant that is trying to reach an agreement concerning a fair distribution on behalf of the housing region The Hague (R17) argued that “[municipality x] has no interest whatsoever in committing itself to this. Why would they? Yes, potentially the feeling that they might be better off when negotiating about a different topic in their relationship with [municipality y], but [municipality x] has no interest in the subject itself.” Therefore, particular municipalities have an interest in maintaining the status quo. This is in line with earlier findings in the Netherlands (Haffner and Elsinga Citation2009; Levelt and Metze Citation2014). Municipalities may prefer to stay uninvolved in the matter fearing increased pressure on the local housing market (R6, R10), traffic congestions (R6), or social upheaval due to the political sensitivity surrounding the topic (R8, R14, R15, R17, R18).

Municipalities want to base regional agreements about the dispersion of migrant workers on the current distribution of migrant workers working and living in the region. The underlying idea is that municipalities with economies that depend on migrant workers should facilitate housing, while other municipalities have a smaller responsibility. For this reason, the province has commissioned a consultancy office to investigate the current distribution (PBLQ Citation2020). Despite the study, municipalities disagree about the numbersFootnote6 (R3). During a council meeting at the municipality of Rotterdam, the alderman argued “We also do not know the exact numbers due to a lack of registration. But those estimates of ours are – we think – fairly accurate, so we are sticking to our numbers” (Of Rotterdam Citation2021a). While R8 stated: “There are also municipalities in the region that say, ‘I have no migrant workers at all’”. Hence, municipalities try to use data suiting their interests. In addition, discussions about the numbers can be used to delay decision-making (R7, R17).

Next to public stakeholders, particular private stakeholders have an interest in the status quo. As discussed earlier, the majority of migrant workers in the Netherlands are employed via employment agencies. Multiple stakeholders argued that employers hiring migrant workers through employment agencies purposively pass the issue of arranging housing onto employment agencies and prefer to remain uninvolved (R1, R6, R7, R17). Employers assume that housing is arranged well (R15), but in the case of housing abuses, there is no “supply chain responsibility” in place, which means that employers cannot be held accountable for abuses in housing arranged by employment agencies (R2).

Private stakeholders are able to protect this status quo by lobbying for their interests. The chair of the Booster Team Migrant Workers (R1) admitted that implementing additional demands for migrant worker housing will result in additional costs for employers. Consequentially, the chair of the Agricultural and Horticultural Association (R19) fears that these changes will affect the business models of farmers and horticulturalists and said: “it would absolutely be too far-reaching to add these costs. (…) we are not going to do this and will resist this.” Next to resisting legal changes, another option for private stakeholders to protect the status quo is to agree to non-binding agreements. For example, a decade ago multiple stakeholders, among which large employer organizations, came to a declaration of intent to improve the housing conditions of migrant workers (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations Citation2012). R1 criticized this declaration arguing that “intentions and self-regulation are all neoliberal words that in practice mean; nice then we don’t have to do anything”.

Besides lobbying, private stakeholders can exert influence through negotiations about collective labour agreements. In these collective labour agreements, employer organizations and unions negotiate specific housing-related requirements. However, the employer organizations and unions are currently not able to reach an agreement (R1, R21).

Conclusion

Precarious housing conditions among migrant workers in the Netherlands have been a policy issue since the expansion of the EU in 2004 (Booster Team Migrant Workers Citation2020; Committee Lessons from Recent Labour Migration Citation2011). The current study has investigated this policy impasse through a governance network perspective (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016). We found that a major explanation for the persistence of the impasse is the interrelationship between the loosely defined institutional setting and the pursuit of strategic interests by involved actors. Since accountability structures are not clearly defined, public and private actors have the agency to pursue their interests. Concurrently, this pursuit produces and reproduces particular accountability structures that align with their interests (Yang Citation2012). The lack of willingness among municipalities in the Rotterdam region to discuss the provision of housing for migrant workers and the fact that an external consultancy agency was needed in the The Hague region exemplifies this. By leaving the topic undiscussed, municipalities in the two regions protect the status quo and reproduce existing accountability deficits.

The findings of the current study demonstrate the value of network approaches within the housing domain. Following Mullins and Rhodes (Citation2007), network perspectives are crucial in understanding decision-making within the housing domain due to the diversity of involved public, private, and civil stakeholders and the interdependencies among them. While we agree with Stephens (Citation2020) that housing systems are the result of economic, political, social, and ideological power balances, our approach enabled us to shed light on the mechanisms underlying these power balances. In line with earlier research that employed network perspectives, we found that stakeholders use various strategies to exert influence on each other in pursuit of their interests (Rhodes Citation2007; Scholten et al. Citation2018). Our work expands on this by demonstrating the empirical value of perceiving accountability as an endogenous phenomenon that evolves through a struggle for power. This becomes apparent by the pleas of Rotterdam and The Hague for regional accountability structures that would, in their opinion, distribute the burdens and benefits of labour migration more fairly. Another example are employers that lobby for municipal obligations to facilitate the development of housing for migrant workers.

Consistent with earlier research on the local turn in migration studies, our findings demonstrate that challenges surrounding the provision of housing for migrant workers manifest themselves at the local level (Caponio, Scholten, and Zapata-Barrero Citation2019; Schiller and Çağlar Citation2009). The results also align with earlier work that emphasized that political support for immigration is dependent upon the local setting (Money Citation1997). A potential limitation of the current study is the focus on the Rotterdam/The Hague region whereas precarious housing conditions among migrant workers are a policy problem across the Netherlands and the EU (Booster Team Migrant Workers Citation2020; European Policy Institute Citation2020). Yet, we believe our findings are relevant in a wider context as they provide a framework to study policy impasses in the provision of housing in other settings. In addition, our findings demonstrate that while local governments have increasingly gained responsibility in the governance of housing and migration (Doherty Citation2004; Zapata-Barrero, Caponio, and Scholten Citation2017), they are not always able to deal with issues that have been delegated to them from above.

The conclusions of the current study give little reason to believe that the policy impasse will soon be resolved. Yet, the national government has recently proposed a plan to stimulate municipalities to facilitate housing suitable for migrant workers. In the coming years, municipalities will become obligated to map the local migrant worker housing demand and develop regional visions on the facilitation of housing for migrant workers. Provinces will become responsible for overseeing these regional visions (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations Citation2022). Based on our findings, it is to be expected that this plan will only be successful if formal accountability patterns are implemented that include means of enforcement in the case of neglected responsibilities. The fact that this has not happened in the past, despite the persistence of housing precarity among migrant workers, shows that accountability structures are inflexible and arise through a struggle for power.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the research project “Urban Housing of Migrants in China and the Netherlands”. We want to thank all the consortium members for their suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper. In addition, we would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. For the sake of readability, the term “migrant workers” will be used in the remainder of this paper.

2. In 2017, the minister responsible for housing stated that the housing market was “fixed” and that governmental intervention was no longer warranted.

3. National government: https://www.tweedekamer.nl/zoeken;

Province of South Holland: https://pzh.notubiz.nl/zoeken;

Municipalities: https://zoek.openraadsinformatie.nl/.

4. The identities of participants in public positions have not been anonymized to enable us to present the statements of respondents in the right context. We obtained explicit oral or written permission beforehand.

5. Findings were shared with the chairman of the Booster Team Migrant Workers (Emile Roemer) and an expert in wicked policy problems (Prof. Wim van de Donk) who was previously involved in the provision of housing for migrant workers in North Brabant as provincial governor.

6. It is difficult to estimate the precise number of migrant workers in municipalities due to incomplete municipal registers. The registers are incomplete because migrant workers who are planning to stay for less than four months are not legally obliged to register their address (PBLQ Citation2020).

References

- Aarsæther, N., H. Bjørnå, T. Fotel, and E. Sørensen. 2009. “Evaluating the Democratic Accountability of Governance Networks: Analysing Two Nordic Megaprojects.” Local Government Studies 35 (5): 577–594. doi:10.1080/03003930903227394.

- Berntsen, L., and N. Skowronek. 2021. “State-Of-The-Art Research Overview of the Impact of COVID-19 on Migrant Workers in the EU and the Netherlands.” Nijmegen Sociology of Law working paper series.

- Blanco, I., V. Lowndes, and L. Pratchett. 2011. “Policy Networks and Governance Networks: Towards Greater Conceptual Clarity.” Political Studies Review 9 (3): 297–308. doi:10.1111/j.1478-9302.2011.00239.x.

- Booster Team Migrant Workers. 2020. Geen Tweederangsburgers. Aanbevelingen Om Misstanden Bij Arbeidsmigranten in Nederland Tegen Te Gaan. [No Second Class Citizens. Recommendations to Combat Abuses Among Migrant Workers in the Netherlands.]. The Hague: Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid.

- Bovens, M. 2007. “Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework.” European Law Journal 13 (4): 447–468. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x.

- Bovens, M. 2010. “Two Concepts of Accountability: Accountability as a Virtue and as a Mechanism.” West European Politics 33 (5): 946–967. doi:10.1080/01402382.2010.486119.

- Caponio, T., P. Scholten, and R. Zapata-Barrero. 2019. The Routledge Handbook of the Governance of Migration and Diversity in Cities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Committee Lessons from Recent Labour Migration. 2011. Arbeidsmigratie in goede banen. [Labour migration in the right direction]. The Hague: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- Committee of Social Affairs and Employment. 2021. Verslag van een rondetafelgesprek 28 June 2021 [Report of a round table discussion 28 June 2021]. The Hague: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- Creswell, J. W., and D. L. Miller. 2000. “Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry.” Theory into Practice 39 (3): 124–130. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2.

- Doherty, J. 2004. “European Housing Policies: Bringing the State Back In?” European Journal of Housing Policy 4 (3): 253–260. doi:10.1080/1461671042000307242.

- Driessen, P. P., C. Dieperink, F. Van Laerhoven, H. A. Runhaar, and W. J. Vermeulen. 2012. “Towards a Conceptual Framework for the Study of Shifts in Modes of Environmental Governance–Experiences from the Netherlands.” Environmental Policy and Governance 22 (3): 143–160. doi:10.1002/eet.1580.

- Edelenbos, J., and G. R. Teisman. 2008. “Public-Private Partnership: On the Edge of Project and Process Management. Insights from Dutch Practice: The Sijtwende Spatial Development Project.” Environment and Planning C, Government & Policy 26 (3): 614–626. doi:10.1068/c66m.

- Engbersen, G., A. Leerkes, P. Scholten, and E. Snel. 2017. “The Intra-EU Mobility Regime: Differentiation, Stratification and Contradictions.” Migration Studies 5 (3): 337–355. doi:10.1093/migration/mnx044.

- Esmark, A. 2007. “Democratic Accountability and Network Governance—problems and Potentials.” In Theories of Democratic Network Governance, 274–296. Springer.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Etzioni, A. 1975. “Alternative Conceptions of Accountability: The Example of Health Administration.” Public Administration Review 35 (3): 279–286. doi:10.2307/974763.

- European Commission. 2021. Annual Report on Intra-EU Labour Mobility 2020. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Policy Institute. 2020. Are Agri-Food Workers Only Exploited in Southern Europe? Case Studies on Migrant Labour in Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden. Brussels: Open Society Foundations.

- Expertise Centre Flexible Living. 2019. Routekaart naar goede huisvesting voor EU-arbeidsmigranten. [Roadmap to good housing for EU migrant workers]. Hilversum: Expertisecentrum Flexwonen.

- Federation of Dutch Trade Unions. 2020. Eerlijke arbeidsmigratie in een socialer Nederland [Fair labor migration in a more social Netherlands]. Utrecht: FNV.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Government of the Netherlands. 2021. Jaarrapportage Arbeidsmigranten 2021 [Annual Report Migrant Workers 2021]. The Hague: Rijksoverheid.

- Greenports Netherlands. 2021. Kernboodschap Bouwen, bouwen, bouwen! [Key message Build, build, build!]. Zoetermeer: Greenports Nederland.

- Haffner, M., and M. Elsinga. 2009. “Deadlocks and Breakthroughs in Urban Renewal: A Network Analysis in Amsterdam.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 24 (2): 147–165. doi:10.1007/s10901-009-9137-1.

- Harvey, D. 1989. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annaler Series B, Human Geography 71 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583.

- Healey, P., and S. M. Barrett. 1990. “Structure and Agency in Land and Property Development Processes: Some Ideas for Research.” Urban Studies 27 (1): 89–103. doi:10.1080/00420989020080051.

- Jacobs, K., J. Kemeny, and T. Manzi. 2003. “Power, Discursive Space and Institutional Practices in the Construction of Housing Problems.” Housing Studies 18 (4): 429–446. doi:10.1080/02673030304252.

- Kang, V., and D. A. Groetelaers. 2018. “Regional Governance and Public Accountability in Planning for New Housing: A New Approach in South Holland, the Netherlands.” Environment & Planning C: Politics and Space 36 (6): 1027–1045. doi:10.1177/2399654417733748.

- Kemeny, J. 2001. “Comparative Housing and Welfare: Theorising the Relationship.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 16 (1): 53–70. doi:10.1023/A:1011526416064.

- Kemeny, J. 2006. “Corporatism and Housing Regimes.” Housing, Theory and Society 23 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/14036090500375423.

- Klijn, E.H., and J. Koppenjan. 2012. “Governance Network Theory: Past, Present and Future.” Policy & Politics 40 (4): 587–606. doi:10.1332/030557312X655431.

- Klijn, E. H., and J. Koppenjan. 2016. Governance Networks in the Public Sector. London: Routledge.

- Klok, P., B. Denters, M. Boogers, and M. Sanders. 2018. “Intermunicipal Cooperation in the Netherlands: The Costs and the Effectiveness of Polycentric Regional Governance.” Public Administration Review 78 (4): 527–536. doi:10.1111/puar.12931.

- Kokx, A., and R. Van Kempen. 2010. “Dutch Urban Governance: Multi-Level or Multi-Scalar?” European Urban and Regional Studies 17 (4): 355–369. doi:10.1177/0969776409350691.

- Levelt, M., and T. Metze. 2014. “The Legitimacy of Regional Governance Networks: Gaining Credibility in the Shadow of Hierarchy.” Urban Studies 51 (11): 2371–2386. doi:10.1177/0042098013513044.

- Lombard, M. 2023. “The Experience of Precarity: Low-Paid Economic migrants’ Housing in Manchester.” Housing Studies 38 (2): 307–326. doi:10.1080/02673037.2021.1882663.

- Manting, D., T. Kleinepier, and C. Lennartz. 2022. “Housing Trajectories of EU Migrants: Between Quick Emigration and Shared Housing as Temporary and Long-Term Solutions.” Housing Studies 1–21. doi:10.1080/02673037.2022.2101629.

- McCollum, D., and A. Findlay. 2018. “Oiling the Wheels? Flexible Labour Markets and the Migration Industry.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (4): 558–574. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1315505.

- Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. 2012. Nationale verklaring van partijen betrokken bij de (tijdelijke) huisvesting van EU-arbeidsmigranten [National declaration of parties involved in the (temporary) accommodation of EU migrant workers]. The Hague: Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties.

- Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. 2021. Handreiking Huisvesting van Arbeidsmigranten [Guide to Housing Migrant Workers]. The Hague: Ministerie Van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties.

- Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. 2022. Programma ‘Een thuis voor iedereen’ [Program ‘A home for everyone‘]. The Hague: Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties.

- Money, J. 1997. “No Vacancy: The Political Geography of Immigration Control in Advanced Industrial Countries.” International Organization 51 (4): 685–720. doi:10.1162/002081897550492.

- Mullins, D., and M. Lee Rhodes. 2007. “Special Issue on Network Theory and Social Housing.” Housing, Theory and Society 24 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/14036090601002264.

- Municipality of Rotterdam. 2021. Werken Aan Een Menswaardig Bestaan. Actieprogramma EU-Arbeidsmigranten 2021-2025 [Working on a Dignified Existence. Action Program EU Migrant Workers 2021-2025]. Rotterdam: Gemeente Rotterdam.

- Municipality of The Hague. 2019. Samen voor de stad Coalitieakkoord 2019-2022, Together for the city Coalition Agreement 2019-2022. The Hague: Gemeente Den Haag.

- Municipality of The Hague. 2020. Voortgangsrapportage aanpak huisvesting arbeidsmigranten [Progress report on migrant workers’ housing]. The Hague: Gemeente Den Haag.

- Municipality of The Hague. 2021. Commissievergadering Ruimte 31-03-2021 Voortgangsrapportage Aanpak Huisvesting Arbeidsmigranten [Committee Meeting Spatial Planning 31-03-2021 Progress Report on Migrant workers’ Housing]. The Hague: Gemeente Den Haag.

- Myrberg, G. 2017. “Local Challenges and National Concerns: Municipal Level Responses to National Refugee Settlement Policies in Denmark and Sweden.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 83 (2): 322–339. doi:10.1177/0020852315586309.

- Of Rotterdam, M. 2021a. Vergadering WIISA 19-05-2021 Actieprogramma EU-Arbeidsmigranten [WIISA Meeting 19-05-2021 Action Program EU Migrant Workers]. Rotterdam: Gemeente Rotterdam.

- Of Rotterdam, M. 2021b. Raadsvergadering 20-05-2021 Voortgangsrapportage Huisvesting Arbeidsmigranten [Council meeting 20-05-2021 Progress Report Housing Migrant Workers]. Rotterdam: Gemeente Rotterdam.

- Palumbo, L., A. Corrado, and A. Triandafyllidou. 2022. “Migrant Labour in the Agri-Food System in Europe: Unpacking the Social and Legal Factors of Exploitation.” European Journal of Migration and Law 24 (2): 179–192.

- Papadopoulos, Y. 2007. “Problems of Democratic Accountability in Network and Multilevel Governance.” European Law Journal 13 (4). doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00379.x.

- Papadopoulos, Y. 2010. “Accountability and Multi-Level Governance: More Accountability, Less Democracy?” West European Politics 33 (5): 1030–1049. doi:10.1080/01402382.2010.486126.

- PBLQ. 2020. EU-Arbeidsmigranten in de Provincie Zuid-Holland [EU Migrant Workers in the Province of South Holland]. The Hague: PBLQ.

- Poppelaars, C., and P. Scholten. 2008. “Two Worlds Apart: The Divergence of National and Local Immigrant Integration Policies in the Netherlands.” Administration & Society 40 (4): 335–357. doi:10.1177/0095399708317172.

- Pralle, S. B. 2003. “Venue Shopping, Political Strategy, and Policy Change: The Internationalization of Canadian Forest Advocacy.” Journal of Public Policy 23 (3): 233–260. doi:10.1017/S0143814X03003118.

- Randstad audit office. 2019. Bouwen aan regie. Onderzoek naar de provinciale rol op het gebied van wonenResearch into the provincial role in the field of housing], [Developing direction. Amsterdam: Randstedelijke Rekenkamer.

- Rhodes, M. L. 2007. “Strategic Choice in the Irish Housing System: Taming Complexity.” Housing, Theory and Society 24 (1): 14–31. doi:10.1080/14036090601002876.

- Sainsbury, D. 2006. “Immigrants’ Social Rights in Comparative Perspective: Welfare Regimes, Forms in Immigration and Immigration Policy Regimes.” Journal of European Social Policy 16 (3): 229–244. doi:10.1177/0958928706065594.

- Scharpf, F. W. 1997. Games Real Actors Play: Actor-Centered Institutionalism. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Schillemans, T. 2011. “Does Horizontal Accountability Work? Evaluating Potential Remedies for the Accountability Deficit of Agencies.” Administration & Society 43 (4): 387–416. doi:10.1177/0095399711412931.

- Schiller, N. G., and A. Çağlar. 2009. “Towards a Comparative Theory of Locality in Migration Studies: Migrant Incorporation and City Scale.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (2): 177–202. doi:10.1080/13691830802586179.

- Scholten, P., G. Engbersen, M. van Ostaijen, and E. Snel. 2018. “Multilevel Governance from Below: How Dutch Cities Respond to Intra-EU Mobility.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (12): 2011–2033. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341707.

- Schwartz-Shea, P., and D. Yanow. 2013. Interpretive Research Design: Concepts and Processes. New York and London: Routledge.

- Snel, E., M. van Ostaijen, and M. ‘t Hart. 2019. “Rotterdam as a Case of Complexity Reduction: Migration from Central and Eastern European Countries” In Coming to Terms with Superdiversity, edited by P. Scholten, P. Van de Laar, 153–170. Cham: Springer.

- SNF. 2022. Nu 700 ondernemingen met SNF-keurmerk met meer dan 100.000 bedden. [Now 700 SNF-certified companies with over 100,000 beds]. Tilburg: Stichting Normering Flexwonen.

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2005. “The Democratic Anchorage of Governance Networks.” Scandinavian Political Studies 28 (3): 195–218. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.2005.00129.x.

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2007. Theories of Democratic Network Governance. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Statistics Netherlands. 2021a. CBS Migrantenmonitor 2019, Statistics Netherlands Migrant Monitor 2019. The Hague: CBS.

- Statistics Netherlands. 2021b. Vooral Minder Immigranten van Buiten de EU [Fewer Immigrants from Outside the EU]. The Hague: CBS.

- Stephens, M. 2020. “How Housing Systems are Changing and Why: A Critique of Kemeny’s Theory of Housing Regimes.” Housing, Theory and Society 37 (5): 521–547. doi:10.1080/14036096.2020.1814404.

- Susskind, L., and J. Cruikshank. 1987. Breaking the Impasse. New York: Basic books.

- Szytniewski, B., and M. van der Haar. 2022. “Mobility Power in the Migration Industry: Polish workers’ Trajectories in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (19): 4694–4711. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2061931.

- Torfing, J., B. Guy Peters, J. Pierre, and E. Sørensen. 2012. Interactive Governance: Advancing the Paradigm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ulceluse, M., B. Bock, and T. Haartsen. 2022. “A Tale of Three Villages: Local Housing Policies, Well‐being and Encounters Between Residents and Immigrants.” Population, Space and Place 28 (8): e2467. doi:10.1002/psp.2467.

- van Bortel, G. 2009. “Network Governance in Action: The Case of Groningen Complex Decision-Making in Urban Regeneration.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 24 (2): 167–183. doi:10.1007/s10901-009-9138-0.

- Van Bueren, E. M., E. Klijn, and J. F. Koppenjan. 2003. “Dealing with Wicked Problems in Networks: Analyzing an Environmental Debate from a Network Perspective.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 13 (2): 193–212. doi:10.1093/jopart/mug017.

- Verhage, R. 2003. “The Role of the Public Sector in Urban Development: Lessons from Leidsche Rijn Utrecht (The Netherlands).” Planning Theory & Practice 4 (1): 29–44. doi:10.1080/1464935032000057191.

- Work Force, O. 2021. Position paper rondetafelgesprek 28-06-2021 [Position paper round table discussion 28-06-2021]. The Hague: Commissie voor Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid.

- Yang, K. 2012. “Further Understanding Accountability in Public Organizations: Actionable Knowledge and the Structure–Agency Duality.” Administration & Society 44 (3): 255–284. doi:10.1177/0095399711417699.

- Zapata-Barrero, R., T. Caponio, and P. Scholten. 2017. “Theorizing the ‘Local Turn’in a Multi-Level Governance Framework of Analysis: A Case Study in Immigrant Policies.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 83 (2): 241–246. doi:10.1177/0020852316688426.