ABSTRACT

Using a Systematic Quantitative Literature Review (SQLR) approach, this article consolidates studies on the job characteristics (top-down process of job design) and job crafting (bottom-up process of job design) components of sport-related jobs. The SQLR maps the emerging research topic of job design in sport and provides a research direction agenda to guide scholarship. Out of 5,974 retrieved documents, a total of 187 academic articles published in English journals between 1988 and 2021 matched the selected terms in title or abstract or keywords. Following a deductive coding process using NVivo 12, the results demonstrated that previous research has been undertaken mainly over the last 15 years with a focus on job characteristics (77%) compared with job crafting (23%). The emphasis in prior research is placed on: (1) sport managers’ “task” and “knowledge” job characteristics; (2) coaches’ “social” job characteristics; (3) referees’ “contextual” job characteristics, and (4) athletic trainers’ “work – life crafting”. Findings were used to develop two models representing the top-down and bottom-up processes of job design in sport. The top-down model illustrates that: task and knowledge job characteristics influence attitudinal and behavioural outcomes; contextual job characteristics build only well-being outcomes; and social job characteristics predict a wide range of job outcomes. The bottom-up model highlights the significance of approach relational crafting, avoidance task crafting and work – life crafting in shaping behavioural and well-being outcomes. The most understudied area is job crafting among sport volunteers, a gap worth examining further in future research.

1. Introduction

Job design, as described by Morgeson and Campion (Citation2021), refers to the way in which work is structured, organised, experienced, and carried out. This practice is acknowledged as a crucial aspect of human resource management (HRM) within sport organizations, as it has been shown to enhance employee job satisfaction and commitment (Oldham & Fried, Citation2016) and address issues related to turnover (Chelladurai & Kim, Citation2022). Job design is comprised of the top-down (e.g., job characteristics model theory – Hackman & Oldham, Citation1976) and bottom-up (e.g., job crafting theory – Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001) processes.

Specifically, job design research in sport includes studies on both job characteristics and job crafting across a wide range of individuals engaged in voluntary or paid work. This includes sport employees (Hwang & Jang, Citation2020), coaches (Prochnow et al., Citation2020), referees (Loghmani et al., Citation2017, Citation2021), athletic trainers (Mazerolle & Hunter, Citation2018) and event volunteers (Cuskelly et al., Citation2021; Neufeind et al., Citation2013). While job design has been extensively covered in the sport management literature by Chelladurai and Kim (Citation2022), the current understanding of job design mainly focuses on task and knowledge characteristics. Hence, there are opportunities for job design researchers to explore other aspects of job design such as social and contextual job characteristics as well as job crafting (Taylor et al., Citation2015).

Furthermore, sport-specific job design studies have extended our understanding of the nature of different sports jobs, workers’ reactions to their job descriptions (Chelladurai & Kim, Citation2022), and the causes (e.g., personality, social support, workaholism) of job crafting (Taylor et al., Citation2021). Such understanding has provided targeted guidelines for recruitment (Cuskelly et al., Citation2021) and retention (Loghmani et al., Citation2022) of staff/volunteers in sport organisations and events. This line of job design work is important because sports jobs are different to other jobs in terms of work environments (i.e., government dependent NSOs, voluntary sport clubs), domains (match official compared to sport coach) and scope/level (coaching a local sport team compared to coaching a professional sports team) (Chelladurai & Kim, Citation2022). As a result, the unique nature of sports jobs mentioned above may influence the reactions of individuals (both voluntary and paid staff) to job characteristics and job crafting. For instance, volunteer coaches working at grassroots or community level typically have a broader range of responsibilities and may focus on providing a positive and inclusive experience for participants, while professional coaches at the elite level often have more specialised roles and emphasise performance-oriented training and competition, which may involve higher levels of pressure and expectations (Sotiriadou et al., Citation2023). Hence, job characteristics and job crafting may differ as community-level and volunteer coaches prioritise community engagement and development, whereas elite-level and professional coaches prioritise performance outcomes and athlete development. Despite acknowledging the differences, research on job design in the sport industry does not offer a comprehensive understanding of how volunteers and paid staff working at different levels of sports differ in their perception of job characteristics and the way they craft their roles.

Although job design is only one aspect of HRM in sport and recreation (Chelladurai & Kim, Citation2022; Taylor et al., Citation2015), the above studies highlight the growing research interest in, and impact of, this work on the field. Although there have been significant contributions to the field, the existing literature on job design is disjointed and lacking structure due to the broad nature of the topic. As a result, previous research has tended to focus on specific elements of job design within certain stakeholder groups, such as interdependence in the coach-athlete relationship (Nicholls & Perry, Citation2016). Consolidating this knowledge can advance our understanding of the structure and nature of different sports jobs, and enable informed modifications to job analysis, competency modelling, and job specifications. Additionally, such consolidation may guide other HRM practices in sport, including training, retention, promotion, and performance management (Chelladurai & Kim, Citation2022). A systematic review and synthesis of existing work is needed to connect related studies, identify knowledge gaps, propose future research directions, and shape implications for practice. This will help to reveal gaps in the literature and identify opportunities for further research to advance the field. Thus, this paper aims to systematically review and holistically collate the existing research on job design in sport and provide an agenda for further research.

2. Scope of job design in sport

illustrates that the scope of job design in sport represents the interaction of job design processes (e.g., job characteristics and job crafting), the sport industry (e.g., professional and consumer services) and individuals working in sport industry (i.e., volunteers and paid staff).

The terms job analysis, job design, and job specifications are often used interchangeably. Job analysis deals with collecting and analysing information about the content, human requirements, and the context of jobs. Job specification determines the employees’ skills, knowledge and behavioural requirements (Sanchez & Levine, Citation2009). Job design focuses on “tasks or activities that employees complete for their organisations on a daily basis” to achieve organisational and individual positive outcomes (Oldham & Fried, Citation2016, p. 20). The purpose of job analysis and job specifications is to recruit and select the right person by gathering the information on the job and operators’ responsibilities, generating the job description and outlining the candidate’s competencies (e.g., skills, abilities, education and experiences) that are necessary to qualify for the specific job (Sanchez & Levine, Citation2009). However, the purpose of job design is to increase employee job satisfaction, engagement, and commitment; whilst decreasing turnover and burnout by considering the “actual structure of jobs” (Oldham & Fried, Citation2016, p. 20). It is outside the scope of this study to expand and explore all these areas of research. The focus of this paper is on job design as it refers to work itself and contributes to human resource retention, promotion, and performance, providing sport organisations with guidelines to overcome employee turnover issues through modifying the structure of the job (Chelladurai & Kim, Citation2022).

2.1. Job design processes and dominant approaches

Following the emergence of the job design concept, a wide range of theories were proposed to better understand job design applications for both employees and organisations Morgeson & Campion,Citation2021). These theories are divided into two categories, explaining the top-down and bottom-up processes of job design. The theories related to top-down processes delineate one job description for everyone that can be designed by managers, whereas bottom-up process-based theories focus on individual and unique job design undertaken by employees (Oldham & Fried, Citation2016). Job characteristics theory (JCT) has become a widely applied top-down approach to job design (Hackman & Oldham,Citation1976). According to JCT, the actual structure of a given job encompasses important characteristics that can shape the psychological states of employees and lead to attitudinal, behavioural, well-being and organisational outcomes (Morgeson & Campion, Citation2021). For example, task significance increases the meaningfulness of work, and job autonomy can develop the sense of responsibility. Creating psychological states of meaningfulness of the work and responsibility contributes to employees’ job satisfaction, engagement and well-being. provides a definition of each job characteristic with an exemplar in a sport-related job.

Table 1. Definition and terminology of each job characteristic with an example of a sport-related job.

As opposed to JCT, job crafting theory has become a well-accepted approach to job design from a bottom-up process perspective (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001). As a hierarchical structure, job crafting is reflected by approach crafting, avoidance crafting and work – life and leisure crafting (Lazazzara et al., Citation2020). outlines each form of job crafting in conjunction with an example of a sport-related job. Thus, understanding the concept of job design depends on comparing top-down and bottom-up theories. Application of these theories and subsequent implementations have played a transformative role for sport organisations and employees in terms of achieving positive job outcomes.

Table 2. Definition and terminology of each job crafting form with an example of a sport-related job.

2.2. Sport industry: professional/consumer services delivered by sport organisations

Sport industry includes both community/grassroots and professional/elite levels within which sport is played. Grassroots sports are community-based activities at a local level, while professional sports involve highly skilled athletes competing at the highest level. Sport organisations require a wide range of employees with different job characteristics to deliver consumer services (e.g., Registrar) and professional services (e.g., Coaching, Refereeing) to their clients (Chelladurai & Kim, Citation2022). Developing grassroots sports is crucial for sustaining professional sports by serving as talent pools for identifying and nurturing athletes who may transition to the professional level (Sotiriadou et al., Citation2023). Taylor et al. (Citation2015) argued that professional and consumer services can be offered across profit, not-for-profit, public, private sectors, and span large or small sport organisations. Sport services are also offered on a global or small/regional scale, ranging from one-day tournaments to year-round championships, amateur or professional competitions, and mega-events for spectators and participants (Thomson et al., Citation2019). Such figures demonstrate sport organisations need both paid and voluntary staff with high levels of job satisfaction to operate their events.

2.3. Volunteers and paid staff/professionals in sport

Individuals in the sport industry provide their labour and time either on a paid basis as employees or as volunteers. Paid sport staff seek job security (Loghmani et al., Citation2022), whereas volunteers work in sport industry due to active sport participation, empowerment and task fit, and solidarity and satisfaction (Cuskelly et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, Chelladurai and Kim (Citation2022) found that both volunteers and paid staff are important for delivering sport services, as they tend to know, act and learn new skills from their jobs. The importance of sport volunteers and paid staff, as outlined above, highlights the need to investigate their job design. This review is therefore focused on job design research undertaken in the sport industry and among voluntary and paid staff in sport.

3. Methods

This study utilised a Systematic Quantitative Literature Review (SQLR) (Pickering & Byrne, Citation2014), which is widely used method in sport management (Mollah et al., Citation2021; Nolan et al., Citation2022; Thomson et al., Citation2019). As such, the SQLR approach was deemed appropriate for this research and to achieve our aim to produce a comprehensive and integrative review of extant job design literature. depicts each of SQLR steps taken in this study. Steps 1 and 2 include the scope of the review “job design in sport” and seven research questions (RQs):

Figure 2. The SQLR steps (Pickering & Byrne, Citation2014) taken in this study.

RQ1:

Who has conducted job design research in sport, when and where?

RQ2:

What theoretical frameworks/models have underpinned the research?

RQ3:

What research design approaches, samples and context were used?

RQ4:

What research has been conducted on the job design elements in voluntary and paid staff within the context of sport?

RQ5:

What job characteristics and job crafting types have been explored following by top-down and bottom-up processes of job design in sport literature, and what have been the antecedents, outcomes, mediators, and moderators (job characteristics and job crafting components)?

RQ6:

What are the key relationships between identified variables (the two models that show the relationships between above factors)?

RQ7 :

What research remains to be conducted to further inform and advance this field both theoretically and in practice?

To identify keywords (Step 3), we utilised terms related to the sport industry, as well as voluntary and paid staff (see ). Additionally, job characteristics and job crafting components from were used to determine 28 distinct keyword categories. Step 4 in the SQLR revolved around choosing databases for searching and retrieving the relevant documents. A combination of different databases was selected to facilitate a thorough search which is both comprehensive and can be cross-checked (Pickering & Byrne, Citation2014). Step 5 of the SQLR involved setting inclusion and exclusion criteria to assess retrieved documents and construct the final sample of articles. The inclusion parameters for this study required the full-text papers to be original research because “the research results have been peer-reviewed and that the papers are primary sources” (Pickering & Byrne, Citation2014, p. 543). Grey literature sources, such as unpublished dissertations and conference papers, may contain theoretical frameworks and research designs, but other types of grey literature like industry reports or book chapters do not necessarily include these essential research concepts. Therefore, grey literature has been excluded from this review to ensure that the authors can effectively address research questions RQ2 and RQ3 with high-quality and reliable data. Also, research articles in languages other than English were excluded from the literature sampling process. The year 1988 was chosen as the starting point for data collection because it coincided with the first published article (Parsons & Soucie, Citation1988) regarding job design in sport. To retrieve the relevant articles, we followed a specific search process in consultation with a librarian expert. Firstly, we searched sport industry terms. Secondly, we searched sport workers. Thirdly, we combined these two categories to create the sport context. Fourthly, we categorised job design terms and their synonyms into 28 search strings and conducted separate searches. Using different search strings was necessary as job characteristics and job crafting terms have distinct meanings, and including all terms in a single search string could lead to errors. Lastly, we separately combined each of 28 job design terms with the sport context. This process was repeated across five selected databases, in which the potential documents were retrieved 259 times ([1 + 1 + 1 + 28 + 28]×5). At the conclusion of the search process, 5,974 documents were initially retrieved from the selected databases, with Scopus (n = 2,666; rate = 45%) returning the most results. After excluding documents according to the established exclusion criteria (see ), a total of 187 articles were retained and readied for analysis.

To gauge the quality and mitigate selection bias within the final sample of articles, we employed the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist designed for cohort studies (CASP, Citation2018). Despite CASP’s limitations, such as a potential lack of depth in capturing specific nuances of studies, its selection was driven by its comprehensive nature and suitability for evaluating methodological rigour (Tod et al., Citation2022). The CASP checklist encompasses 12 key questions (Q): (Q1) Did the study address a clearly focused issue?, (Q2) Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way?, (Q3) Was the exposure accurately measured to minimise bias?, (Q4) Was the outcome accurately measured to minimise bias?, (Q5a) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors?, (Q5b) Have they taken into account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis?, (Q6a) Was the follow up of subjects complete enough?, (Q6b) Was the follow up of subjects long enough?, (Q7) What are the results of this study?, (Q8) How precise are the results?, (Q9) Do you believe the results?, (Q10) Can the results be applied to the local population?, (Q11) Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence?, and (Q12) What are the implications of this study for practice? These questions were systematically applied to the final sample of articles.

Each author conducted individual assessments, followed by a collaborative meeting to collectively evaluate the included studies against the 12 CASP questions. During the critical appraisal process, we followed the guidelines outlined by Tod et al. (Citation2022). This involved constructing a table where each study was listed in rows and the CASP criteria were listed in columns. Our assessments for each question were summarised as “Yes”, “Can’t tell”, or “No”. To visualise the CASP assessment outcomes, we opted for a bar chart, as it effectively illustrates the strengths and weaknesses across the included studies in our review (Tod et al., Citation2022). depicts the percentage of studies that met each CASP criterion with a “Yes” response. Notably, all the included studies collectively achieved nearly 88% of the CASP criteria, underscoring their adequate quality for subsequent analysis.

Figure 3. Percentage of studies meeting each critical appraisal criterion included in CASP checklist.

To undertake the sixth step of SQLR, a total of 61 initial categories and subcategories was created based on the RQs 1–6. In accordance with Pickering and Byrne’s (Citation2014) guidelines, the research team developed the initial categories in discussion with each other during the process of data categorisation. Using Pickering and Byrne’s (Citation2014) processes, approximately 10 per cent (n = 20) of the total sample of articles were initially reviewed (Step 7) to test the efficiency of potential categories/themes and quantify the number of articles that could be put into the identified categories/themes (Step 8). To address RQ1 and RQ5, the 20 articles were categorised using direct data extraction, referring to the same words or concepts extracted by the author(s).

To address the remaining research questions, the 20 sample articles were categorised using a combination of direct data extraction and interpretation. Based on the initial review of 20 sample articles, the meaningful categories/themes “job characteristic”, “job crafting”, “antecedents”, “mediators”, ‘moderators, “outcomes” and “key relationship” were coded through a deductive coding process in accordance with the integrative and comprehensive models of job design (Grant et al., Citation2011) and job crafting (Lazazzara et al., Citation2020). To increase the trustworthiness of the coding process, the lead author implemented a rigorous code-checking system applied across the research team. This involved a debate between researchers for identifying, revising and validating the categories (Thomson et al., Citation2019). Once the research team reached a consensus throughout the process of categorisation (Step 8), the lead author proceeded coding all remaining articles (Step 9). Such categorisation enabled the authors to follow Step 10 of the SQLR by developing top-down (job characteristics) and bottom-up (job crafting) models of job design as they apply in sport and draft the manuscript (Steps 11–15).

As there were many articles identified (n = 187), NVivo 12 was used to manage the data, categorise the articles, and determine the word frequency of article title and keywords. In addition, the coding data extracted from NVivo 12 were exported to an Excel spreadsheet to run frequencies and visualise the dataFootnote1.

4. Results

The result section includes bibliographic information and matrices of job design elements on volunteers and paid staff, followed by conceptual models for future research.

4.1. Bibliographic information

In total, 155 unique first authors and 126 individual affiliated universities were identified. Organised by number of articles and then by alphabetical order, the first authors with three or more articles were: Stephanie M. Mazerolle (n = 14, University of Connecticut, USA); Javier Mallo (n = 4, Polytechnic University of Madrid, Spain); Ausra Lisinskiene (n = 3, Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania); Mohsen Loghmani (n = 3, Shafagh Institute of Higher Education, Iran); and David Rainey (n = 3, John Carroll University, USA).

There is a clear bias regarding Western culture-related regions, with North America (n = 67), Europe (n = 64), and Australia and New Zealand (n = 29) accounting for almost 85 per cent of the literature sample. The regions/continents with the lowest research outputs based on the home location of the first authors were Africa (n = 1), Central America (n = 1) and South America (n = 3). Located in a non-Western region, Asian universities/institutions (n = 29) have made the greatest contribution to developing job design as an area of study in the sport.

As shown in , an accelerating trend of publications was observed from 2007 onwards, reaching its highest point in 2021 (29 articles). Although the 34-year average is low (i.e., 5.5 articles per year), the average number of articles published over the last 10 years (i.e., 15 articles per year) and five years (i.e., 18.6 articles per year) illuminates the emerging body of knowledge that is developing in the job design research field in sport literature.

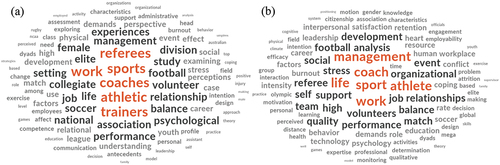

4.2. Article title and keyword

displays the terms “sport”, “coach”, “athletic trainer”, “work”, “football”, “referee”, “volunteer”, “life” and “management” were the most used words within the article titles and keywords, counted 545 (out of 3001 total words used in titles and keywords) times across 187 articles. The above findings revealed a centrality of research as it relates to work management of coaches, referees, and volunteers in the sport industry.

4.3. Theoretical frameworks/models used in the literature

In total, 62 different theories/models were identified across almost half of the sample articles (n = 92), with the rest of articles (n = 95) not including any specific theories. The four most common theories/models that informed the identified articles were the Actor – Partner Interdependence (A – PI) Approach (n = 10); Job Characteristics Model (JCM) Theory (n = 8); Self-Determination Theory (S-DT) (n = 5); and Psychological Contract Theory (PCT) (n = 3). These theories/models were predominantly used to investigate social job characteristics such as interdependence and social support, as well as approach relational crafting.

4.4. Methodologies

The identified articles used quantitative (n = 97), qualitative (n = 68) and mixed-method (n = 19) approaches. The included articles used mostly quantitative research methods (n = 21). Almost 90 per cent (n = 168) of sample articles collected data using surveys (n = 96) or interviews (n = 76). The remaining articles collected data using audio/video recordings (n = 23); archive and organisational documents (n = 5); observation and fieldnotes (n = 5); and reflective letters (n = 1).

In addition to research design, the sample articles presented the research context in the Method section. Of 187 articles in the literature sample, only 15 articles focused on sport events (mega-event, n = 6; local/national event, n = 6; competition/tournament, n = 2; hallmark event, n = 1). Most of the articles were in the context of sport organisations/teams (national/elite level, n = 115; community level, n = 60). Further to the research context, the results indicate that the articles in the sample have mainly used job design concepts among sport coaches/instructors (n = 77), followed by sport administrators and employees (n = 43), referees/umpires (n = 38), athletic trainers (n = 24) and event volunteers (n = 13).

Data have been collected from 31 unique countries across the literature sample. The regions with highest number of data collection were: (1) Europe (UK, n = 24; Spain, n = 6; Germany, n = 5; Greece, n = 5; Sweden, n = 4; Turkey, n = 4; Lithuania, n = 3; Poland, n = 3; France, n = 2; Italy, n = 2; Portugal, n = 2; Russia, n = 2; Switzerland, n = 2; Belgium, n = 1; Croatia, n = 1; Finland, n = 1; Israel, n = 1; and Norway, n = 1); (2) North America (USA, n = 50; and Canada, n = 12); (3) Oceania (Australia, n = 26; and New Zealand, n = 4); (4) Asia (Iran, n = 10; China, n = 8; Singapore, n = 3; Japan, n = 2; North Korea, n = 1; and South Korea, n = 1); (5) South America (Brazil, n = 3); (6) Africa (South Africa, n = 1); and (7) Central America (Mexico, n = 1).

4.5. The matrix of job design elements on volunteers and paid staff

In , a matrix of job design elements examined on both volunteers and paid sport staff is displayed. The matrix indicates that most of the sample articles (n = 201) were concentrated on job characteristics (upper section of the matrix), with only 62 articles focusing on job crafting (lower section of the matrix). The right side of the matrix shows that there are 197 job design elements that have been investigated among paid sport staff, whilst 66 job design elements were centred on sport volunteers. Job characteristics research revolves around paid sport coaches (top right quadrant) and volunteer referees/umpires (top left quadrant), whilst the most of job crafting research pertained to paid athletic trainers (bottom right quadrant) and voluntary and paid sport coaches (bottom left quadrant) (also, see bold highlighted areas in ). However, there were no articles investigating job characteristics and job crafting among volunteer sport managers/club employees and officials, nor athletic trainers.

Figure 6. Matrix of job design elements on volunteers and paid sport staff.

Based on , there were 87 (out of 201) job characteristics articles that investigated social characteristics (e.g., social support and interdependence), especially among paid sport coach. In contrast, 27 (out of 62) articles on job crafting components examined work – life crafting among athletic trainers. These results indicate that the approach and avoidance job crafting have been relatively neglected in the sport literature. also outlines the matrix of categorised articles demonstrating the emphasis in prior research is placed on (1) sport managers’ “task” and “knowledge”; (2) coaches’ “social”; and (3) referees’ “contextual” job characteristics.

Table 3. The matrix of job design elements on position title.

Furthermore, the 46 individual antecedents (e.g., job expectation, credentials), the 14 unique mediators (e.g., psychological states), the seven moderators (e.g., individual differences and career stages) and the 29 unique outcomes/consequences (e.g., job satisfaction and well-being) have been identified and coded 267 times across the 187 sample articles reviewed. The above findings shape key relationships and thereby conceptual models, which are presented in next section.

5. The two conceptual models of the study

Upon analysing the significant associations between job characteristics, job crafting components, as well as their antecedents and outcomes, two conceptual models have emerged. These models represent the top-down and bottom-up processes of job design research within the context of sports.

5.1. The top-down model of job design in sport (job characteristics)

In the top-down model of job design (job characteristics), there are direct and indirect relationships between job characteristics and outcomes. In terms of the direct relationships (light grey in ), the data showed that social and interdependence directly influence attitudinal and behavioural such as cultural awareness, performance, growth satisfaction, job satisfaction, retention, organisational commitment, and leadership off the field (n = 13). In addition to attitudinal (n = 6) and behavioural (n = 4) job outcomes, social support directly led to organisational (n = 3) and well-being (n = 3) outcomes (e.g., sport diplomacy, inclusion, return to sport, health, burnout, and stress). Only one article investigated the direct effect of interaction on performance. Furthermore, contextual, and additional job characteristics such as “ergonomics”, “work condition”, “physical demands” and “time pressure” were able to directly shape only the well-being outcomes (e.g., stress, vocal health, and burnout) (n = 25).

Figure 7. The top-down model of job design in sport (job characteristics).

Second, the top-down model of job design in sports illustrates the mediating factors that facilitate the indirect relationship between job characteristics and outcomes. illustrates that the greatest number of antecedents identified in the literature sample are associated with social characteristics, especially “Interdependence” (n = 10) and “Social Support” (n = 6). Job expectations (n = 6) and credential (n = 3) are the most important factors affecting the task and knowledge job characteristics.

In addition, the results show that 18 articles addressed the relationship between task characteristics and job outcomes, while only three articles focused on knowledge characteristics and their outcomes. Psychological states and job involvement were the main mediators for those relationships. Apart from task and knowledge job characteristics, only interdependence, interaction and work conditions had mediators for job outcomes such as satisfaction, turnover intention, and organisational commitment. Nine articles examined factors that moderate the relationship between job characteristics and outcomes, such as individual roles, volunteer types, gender, social satisfaction, sport type, experience, and age.

5.2. The bottom-up model of job design in sport (job crafting)

Unlike the top-down model, there are no significant mediators for the bottom-up model of job design in sport. illustrates that “social support”, and “approach relational crafting” are the main antecedents of job crafting, as they can lead to work – life crafting and thus build the behavioural and well-being outcomes. Only approach task crafting and leisure crafting did not have any antecedents.

The results also show that work – life crafting (n = 10), approach relational crafting (n = 9) and avoidance task crafting (n = 7) are the most important job crafting techniques (26 of 36 articles) in terms of job outcomes’ prediction. However, only behavioural (e.g., performance) and well-being (e.g., burnout, stress) outcomes were predicted by job crafting components, whereas organisational and attitudinal job outcomes have been neglected and deserve further investigation. Only one factor, “career stages”, could moderate the relationship between job crafting and job outcomes.

6. Discussion

This paper examined the current state of job design research in sport by systematically collating and analysing bibliographic details, theoretical frameworks, research designs, job characteristics, job crafting and key relationships across extant literature. Although such analysis demonstrated the novelty of job design scholarship in sport, the sample articles indicate some patterns that help extend the body of knowledge. We discuss the theoretical and practical contributions that address RQ7 and point out underdeveloped areas which would benefit from further research. We conclude with highlighting the study limitations.

6.1. Bibliographic information

Understanding the lead authors’ perspective of job design research is crucial. The low number of first authors shows that job design in sport is not considered the focus of research from the viewpoint of sport scholars. Single authors had a narrow focus on one specific aspect of job design and on specific sport stakeholders. Such a narrow focus can be explained by the fact that job design includes different job characteristics and job crafting components that need to be conceptualised and then tested in separate in-depth studies (Morgeson & Campion, Citation2021; Oldham & Fried, Citation2016). It is therefore expected that the identified first authors will continue to conduct research on the specific job design area in which they work, in wider populations in the sport such as club officials, boards and club/event volunteers.

Most of the sample articles were published from year 2007 onwards. Such a pattern has been observed in relationship quality in sport (Nolan et al., Citation2022), sport tourism (Mollah et al., Citation2021) and sport event legacy (Thomson et al., Citation2019) literature, signalling the simultaneous growth of different areas of the sport management field in the early twenty-first century.

6.2. Theoretical framework used in the literature

Generally, theories and models used in the sample articles were singularly cited, as almost 80 per cent (n = 50) of theoretical frameworks/models were incorporated only once. This finding indicates that the existing literature lacks a definitive theory or framework pertaining to job design in the context of sports. The singular cited theories may also indicate a narrow focus of first authors conducting job design research in sport. For instance, Nicholls and Perry (Citation2016) applied A – PI to show that job characteristic “interdependence”, in the form of the coach – athlete relationship, is more important to coaches than it is to athletes in predicting dyadic coping and stress appraisal. However, being outside original job design theories, the specific theoretical approaches do not directly contribute to the field. In Nicholls and Perry’s (Citation2016) study, job characteristic “interdependence” was investigated through the coach – athlete relationship, rather than via job design theories. In contrast, Loghmani et al. (Citation2021) combined an out-of-area perspective (i.e., career dynamic perspective posed by Fried et al., Citation2007) with JCM and job crafting theories to measure how talented individuals can become elite football referees. Therefore, it may be beneficial to integrate the main theories of job design, such as the job characteristics model and job crafting, with other relevant theories.

6.3. Methodologies

The findings revealed that there was a balance between using qualitative and quantitative methods in sample articles which is justifiable, as the job design concept needed to be conceptualised and then tested (Morgeson & Campion, Citation2021). However, there is a lack of empirical/experimental research methods (e.g., action research, quasi-experimental method, longitudinal design) in this area. These methods can assist researchers in broadening the job design theories utilised in sports by recognising changes over time and encouraging cooperation with practitioners (Grant & Wall, Citation2009).

Despite a reasonable diversity of data and generalisability of the job design concept in sport between and within the continents/regions of Europe, North America, Asia and Oceania, cultural biases were also observed. Research investigating job crafting components and the social and contextual job characteristics only analysed data from European and North American countries (Prochnow et al., Citation2020), while task and knowledge job characteristics were more typically collected from Asian participants (Hwang & Jang, Citation2020; Loghmani et al., Citation2017). To address the mentioned bias, future research is anticipated to collect task and knowledge characteristics from European and North American participants, as well as social and contextual characteristics from Asian participants. As the United States and European societies are future-oriented (Fried et al., Citation2007), it appears that culture can moderate the relationship between job design practices and outcomes.

6.4. Matrix of job design elements in voluntary and paid sport staff

The findings revealed that research interest in job characteristics is heavily dependent on the types of job position. Sport managers and employees need task and knowledge job characteristics for better decision-making and in completing routine tasks (Hwang & Jang, Citation2020). Coaches and athletic trainers are expected to use their social job characteristics to communicate effectively with players, as this relationship helps coaches to encourage and increase the athlete’s capacity (Nicholls & Perry, Citation2016). Referees need to pay attention to contextual job characteristics to remain in their careers by overcoming negative work conditions, physical demands, and time pressures (Loghmani et al., Citation2021).

Unlike job characteristics, job crafting depends on paid sport staff. For instance, full-time coaches, match officials and sport instructors craft their jobs through goal setting at early and later career stages (Case & Branch, Citation2003; Loghmani et al., Citation2021). Administrators and paid employees in sport organisations craft their jobs through delegating their tasks, managerial activities and decisions (Case & Branch, Citation2003). Although paid sport staff undertake the vast majority of job crafting techniques, volunteer coaches undertake mostly avoidance relational crafting through mechanisms which separate them from others (e.g., spending time alone and turning off their phones) (Potts et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it is concluded that paid sport staff are more likely to job craft, because they are engaged in regular work and need to identify ways to break up their work routine (Fried et al., Citation2007).

From the above discussion, it is evident that the area of job crafting knowledge among sport volunteers is often neglected. Since volunteers play a critical role in both sport events and sport organisations (Cuskelly et al., Citation2021), researching the changes that volunteers actively want to make to their job designs is crucial for promoting engagement, job satisfaction, resilience, and thriving. Therefore, volunteer job crafting research should be considered an essential area of future research. Filling these gaps would help sport and event managers to understand how to increase the productivity of the sport industry and provide opportunities for volunteers to feel motivated and avoid burnout, as well as reducing volunteer attrition.

6.5. Job design models in sport

The results showed that job design influences job outcomes of voluntary and paid staff in sport through three types of effects. Following sections discuss each of effects.

6.5.1. Top-down model of job design in sport: direct effects of job characteristics

Among job characteristics, social (i.e., interdependence and social support) and contextual (i.e., work conditions, ergonomics and physical demands) job characteristics directly influenced job outcomes. Studies investigated direct effect of interdependence on outcomes are limited to community- and elite-sport levels. In community sport clubs, interdependence in forms of social cohesion, community networks and cooperation can lead to volunteer (e.g., executive committee members) job satisfaction, cultural awareness and coach commitment (Doherty & Carron, Citation2003). In elite-level sport, there is interdependence based on coach-athlete relationship and coach-board cooperation in which they build positive behaviours of closeness, commitment and complimentarily, athlete performance and leadership off the field (Molan et al., Citation2016).

Although the “interdependence” could only predict attitudinal and behavioural outcomes, “social support” directly advances sport coaches’ well-being and organisational outcomes such as sport diplomacy (Kuo & Kuo, Citation2020). Another group of research showcased the profound effects of social support on retention of sport employees who are LGBT and volunteered in major sport events (Melton & Cunningham, Citation2014). Finally, contextual job characteristics and time pressure affect only well-being outcomes such as stress, vocal health and judgement among sport coaches and match officials (Prochnow et al., Citation2020).

Future research should focus on investigating the direct relationships between different factors and job outcomes in various sports-related roles. Specifically, (1) the link between contextual characteristics and attitudinal, behavioural, and organizational job outcomes among match officials; (2) the association between task and knowledge job characteristics and job outcomes among sport managers, club officials, sport coaches, match officials, and athletic trainers; (3) the impact of interaction and feedback from others on job outcomes among sport coaches; and (4) the influence of all job characteristics on job outcomes among sport event volunteers. Addressing these relationships would provide valuable insights for improving job design and enhancing job outcomes in various sports-related roles.

6.5.2. Top-down model of job design in sport: indirect effects of job characteristics

Based on the top-down model of job design (see ), actor and partner effects are the most important antecedent predicting interdependence between coach and athletes (Nicholls & Perry, Citation2016). Despite these advantages, the findings revealed that no antecedents predict, and no outcomes are achieved from, the other social job characteristics, including “interaction” and “others” feedback’. Only one article showed that interaction between employees and customers in sport organisations can lead to service quality and consumer citizenship behaviour and satisfaction (Kim & Byon, Citation2018).

Sport volunteer expectations are the most important antecedents for the task and knowledge job characteristics. Egli et al. (Citation2014), for instance, found that the volunteers seeking the internal incentives and recognition were more likely to react favourably to the task, knowledge, and contextual job characteristics, while volunteers seeking participation and communication and support tend to react favourably to the social job characteristics. Unlike social job characteristics, task and knowledge job characteristics were unable to directly build work consequences, as they require some mediators, such as psychological states (Loghmani et al., Citation2017) and organisational identification (Hwang & Jang, Citation2020).

The results showed that most mediators are associated with the relationship between task and characteristics and attitudinal outcomes (e.g., growth satisfaction, job satisfaction and internal work motivation) (Hwang & Jang, Citation2020; Loghmani et al., Citation2017; Neufeind et al., Citation2013). However, social job characteristics (i.e., interdependence and interaction) and work conditions can increase the behavioural and attitudinal outcomes through building job satisfaction. Therefore, job satisfaction can act as both a mediating variable as well as an outcome. Specifically, job satisfaction is a mediator in the relationship between social job characteristics and turnover intentions and organisational commitment. However, job satisfaction can also be an outcome of task characteristics and organisational identification. It is expected that future research will focus on knowledge job characteristics and their organisational and wellbeing job outcomes. Moreover, social and contextual job characteristics need to be tested by mediators to predict job outcomes.

The previous studies found that individual roles and volunteer types moderate the relationship between the task and knowledge job characteristics, and psychological states and job outcomes among sport managers and event volunteers (Neufeind et al., Citation2013), whereas experience, age, gender, and sport type (Laborde et al., Citation2017) are the moderators that relate to social job characteristics and sport coaches. For example, the genuine episodic volunteers experiencing high task identity and low job autonomy tend to be volunteers at future events, while the job characteristic “task significance” is important for long-term committed volunteers’ intention to volunteer at an event (Neufeind et al., Citation2013). Laborde et al. (Citation2017) found that female and team sport coaches provide more social support than male and individual sport coaches. The above studies demonstrate opportunities to build on existing work by considering moderators among the wider population, especially referees and athletic trainers.

6.5.3. Job crafting model in sport

The bottom-up model of job design developed in this study (see ) shows that individual psychological states coming from perceived secrecy (Brown & Knight, Citation2022), off-field experiences and low levels of job characteristics (Loghmani et al., Citation2021) are the most important antecedents for approaching job crafting. The avoidance job crafting behaviours were caused by a combination of individual psychological states and management perceptions. According to Lazazzara et al. (Citation2020), the above causes of approach crafting are termed “proactive behaviours”, while the others are termed “reactive behaviours”. As the above causes have been explored once, it is highly recommended that future researchers comprehensively identify the proactive and reactive behaviours involved in predicting the job crafting techniques.

Interestingly, finding reveals that social support and interdependence encourage sport workers – especially athletic trainers – to undertake work – life crafting (Mazerolle & Hunter, Citation2018), in addition to directly creating organisational, behavioural, attitudinal and well-being outcomes (Nicholls & Perry, Citation2016). Work-life crafting highlights the importance of job crafting because it advances many outcomes such as retention (Mazerolle et al., 2018), performance (Loghmani et al., Citation2021) and well-being (Potts et al., Citation2019). However, research demonstrated that approach relational crafting and avoidance task crafting can lead to behavioural and well-being outcomes among sport professionals (Case & Branch, Citation2003). In terms of moderating role of career stages, Loghmani et al. (Citation2021) argued that early career football referees individually craft their job through career-based goal setting. However, elite football referees collectively craft their job through avoiding relationship with media and game-based goal setting at later stages of their careers. Based on the above results, it is expected that the future researchers deeply explore the two-way relationships between other job characteristics and job crafting techniques. Such exploration will expand the knowledge regarding how top-down and bottom-up processes of job design are interactively interrelated.

6.6. Limitations

This study has methodological limitations, as some relevant articles may have excluded since they were only retrieved based on selected key terms in the title, abstract and keywords. Hence, it is likely that some articles that were conceptually relevant may have been excluded. Second, the search resulted in papers that met the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Although this approach was comprehensive, it is possible some relevant articles were omitted. Finally, this review did not focus on terms of antecedents (e.g., competency modelling, job analysis) and consequences (e.g., job satisfaction, commitment) of job design. This review emphasised the job design itself to identify unique antecedents and consequences, in addition to conceptualising the job characteristics and job crafting in sport.

6.7. Conclusion

This SQLR develops two sport-specific job design models by reviewing scholarship in sport job design. The models were derived through the comprehensive synthesis of the literature, yielding several significant propositions:

Proposition 1:

Task and knowledge job characteristics lead to psychological states, resulting in attitudinal and behavioural outcomes among sport managers, match officials, and event volunteers.

Proposition 2:

Social support and interdependence are the most critical job characteristics in sport. They are predicted by many antecedents, directly linked to all types of job outcomes, and may cause work-life crafting among coaches and athletic trainers.

Proposition 3:

Attitudinal and behavioural outcomes are achieved through task and knowledge job characteristics, while well-being outcomes are achieved through contextual job characteristics and all job crafting techniques.

Proposition 4:

The type of human resource in sport (voluntary vs paid staff) and job positions (match officials, sport coaches, athletic trainers, sport employees) moderate the direct and indirect effects of job design.

Proposition 4a:

The relationship between social support and interdependence and outcomes are stronger among paid sport coach.

Proposition 4b:

Contextual job characteristics is vital for paid match officials.

Proposition 4c:

Task and knowledge job characteristics more likely predict outcomes among volunteer match officials and paid employees.

Proposition 4d:

Work-life crafting among paid athletic trainers and approach relational crafting and avoidance task crafting among paid sport coaches estimate job outcomes.

Collectively, top-down model showed that solving employee’s attraction and retention in sport depends on stimulating specific job characteristics in specific volunteers and paid sport staff. For example, “social support” works for sport coaches, whereas “physical demand” is appropriate for match officials. However, bottom-up model illustrated that job crafting applies in only paid sport staff and reflects the relational crafting. Despite critical differences, this review demonstrated that the top-down and bottom-up models can be complementary. They are mostly applicable in western cultures, as only task and knowledge job characteristics apply in eastern societies. The scholarship on job design developed in this review can serve as a valuable guide for sport scholars and practitioners in attracting and retaining human resources. By testing and implementing these guidelines in both theoretical and practical settings, they can effectively improve job design in sports organisations.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the ‘Griffith Institute for Tourism (GIFT)’ for supporting the development of the paper. The authors are also grateful for the efforts of Professor Catherine Pickering in organising several workshops on systematic quantitative literature review at Griffith University. Such efforts provided a great opportunity for the authors to undertake the present review. Further, the authors appreciate the kind assistance from Michelle DuBroy, the Griffith Discipline Librarian, for the search process and data collection. Last but not least, the authors would like to thank both anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback during the review process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohsen Loghmani

Mohsen Loghmani is an HDR Candidate in the Department of Tourism, Sport & Hotel Management at Griffith University. His PhD research is about job crafting in non-profit context and its influence on volunteer engagement within the community/voluntary sport clubs. He completed a master’s degree of Sport Management at University of Guilan, Iran, and Bachelor of Sport Sciences at Kerman Technical and Vocational University, Iran.

Popi Sotiriadou

Popi Sotiriadou is an Associate Professor in the Department of Tourism, Sport & Hotel Management at Griffith University. She is well-known expert in managing high performance sport, event and athlete well-being, and organisational capacity to attract, retain and nurture athletes/sport development.

Jason Doyle

Jason Doyle is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Tourism, Sport & Hotel Management at Griffith University. His research areas include sport and event consumer behaviour, strategic marketing and branding, and the impact of consumption on social-psychological well-being.

Notes

1 Supplementary materials related to comprehensive search strings, exemplar of searching process, data extraction approach, sample articles list, detailed findings are available on request.

References

- Brown, N., & Knight, C. J. (2022). Understanding female coaches’ and practitioners’ experience and support provision in relation to the menstrual cycle. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 17(2), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541211058579

- Case, R., & Branch, J. D. (2003). A study to examine the job competencies of sport facility managers. International Sports Journal, 7(2), 25. https://www.proquest.com/docview/219913432?accountid=14543&parentSessionId=mbv2VrzzlKeSpTt19ezQ6xIXlslib2x%2FuQ90oE%2Bjb9w%3D.

- Chelladurai, P., & Kim, A. C. H. (2022). Human resource management in sport and recreation. Human Kinetics.

- Critical appraisal skills programme. (2018). Accessed 4 05 2021. https://casp-uk.net/wpcontent/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018

- Cuskelly, G., Fredline, L., Kim, E., Barry, S., & Kappelides, P. (2021). Volunteer selection at a major sport event: A strategic human resource Management approach. Sport Management Review, 24(1), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2020.02.002

- Doherty, A. J., & Carron, A. V. (2003). Cohesion in volunteer sport executive committees. Journal of Sport Management, 17(2), 116–141. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.17.2.116

- Egli, B., Schlesinger, T., & Nagel, S. (2014). Expectation-based types of volunteers in Swiss sports clubs. Managing Leisure, 19(5), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2014.885714

- Fried, Y., Grant, A. M., Levi, A. S., Hadani, M., & Slowik, L. H. (2007). Job design in temporal context: A career dynamics perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 28(7), 911–927. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.486

- Grant, A. M., Fried, Y., & Juillerat, T. (2011). Work matters: Job design in classic and contemporary perspectives.

- Grant, A. M., & Wall, T. D. (2009). The neglected science and art of quasi-experimentation: Why-to, when-to, and how-to advice for organizational researchers. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 653–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428108320737

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7

- Hwang, J., & Jang, W. (2020). The effects of job characteristics on perceived organizational identification and job satisfaction of the organizing committee for the Olympic games employees. Managing Sport and Leisure, 25(4), 290–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1723435

- Kim, K. A., & Byon, K. K. (2018). A mechanism of mutually beneficial relationships between employees and consumers: A dyadic analysis of employee–consumer interaction. Sport Management Review, 21(5), 582–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.01.003

- Kuo, C., & Kuo, H. (2020). Sport diplomacy and survival: Republic of China table tennis coaches in Latin America during the cold war. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 37(14), 1479–1499. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2020.1860943

- Laborde, S., Guillén, F., Watson, M., & Allen, M. S. (2017). The light quartet: Positive personality traits and approaches to coping in sport coaches. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 32, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.06.005

- Lazazzara, A., Tims, M., & De Gennaro, D. (2020). The process of reinventing a job: A meta–synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 103267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.01.001

- Loghmani, M., Cuskelly, G., & Webb, T. (2021). Examining the career dynamics of elite football referees: A unique identification profile. Sport Management Review, 24(3), 517–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1879556

- Loghmani, M., Cuskelly, G., & Webb, T. (2022). Human resource retention in sport: The impact of self-reflective job titles on job burnout and security. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2093931

- Loghmani, M., Taylor, T., & Ramzaninejad, R. (2017). Job characteristics and psychological states of football referees: Implications for job enrichment. Managing Sport and Leisure, 22(5), 342–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1426488

- Mazerolle, S. M., & Hunter, C. (2018). Work-life balance in the professional sports setting: The athletic trainer’s perspective. International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training, 23(4), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijatt.2016-0113

- Melton, E. N., & Cunningham, G. B. (2014). Who are the champions? Using a multilevel model to examine perceptions of employee support for LGBT inclusion in sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 28(2), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2012-0086

- Molan, C., Matthews, J., & Arnold, R. (2016). Leadership off the pitch: The role of the manager in semi-professional football. European Sport Management Quarterly, 16(3), 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2016.1164211

- Mollah, M. R. A., Cuskelly, G., & Hill, B. (2021). Sport tourism collaboration: A systematic quantitative literature review. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 25(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2021.1877563

- Morgeson, F. P., & Campion, M. A. (2021). Job and team design Salvendy, Gavriel, Karwowski, Waldemar . Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics Fifth Edition (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 383–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119636113.ch15

- Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of applied psychology, 91(6), 1321.

- Neufeind, M., Güntert, S. T., & Wehner, T. (2013). The impact of job design on event volunteers’ future engagement: Insights from the European football championship 2008. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13(5), 537–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.837083

- Nicholls, A. R., & Perry, J. L. (2016). Perceptions of coach–athlete relationship are more important to coaches than athletes in predicting dyadic coping and stress appraisals: An actor–partner independence mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 447. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00447

- Nolan, J. I., Doyle, J., & Riot, C. (2022). Relationship quality in sport: A systematic quantitative literature review. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2130956

- Oldham, G. R., & Fried, Y. (2016). Job design research and theory: Past, present and future. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 136, 20–35.

- Parsons, C. A., & Soucie, D. (1988). Perceptions of the causes of procrastination by sport administrators. Journal of Sport Management, 2(2), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2.2.129

- Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2014). The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 534–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841651

- Potts, A. J., Didymus, F. F., & Kaiseler, M. (2019). Exploring stressors and coping among volunteer, part-time and full-time sports coaches. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(1), 46–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1457562

- Prochnow, T., Oglesby, L., Patterson, M. S., & Umstattd Meyer, M. R. (2020). Perceived burnout and coping strategies among fitness instructors: A mixed methods approach. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(5), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1825986

- Sanchez, J. I., & Levine, E. L. (2009). What is (or should be) the difference between competency modeling and traditional job analysis? Human Resource Management Review, 19(2), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.10.002

- Sotiriadou, P., Thrush, A., & Hill, B. (2023). The attraction, retention, and transition of elite sport development pathways in surfing in Australia. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2023.2190755

- Taylor, T., Doherty, A., & McGraw, P. (2015). Managing people in sport organizations: A strategic human resource management perspective. Routledge.

- Taylor, E., Huml, M., Cohen, A., & Lopez, C. (2021). The impacts of work–family interface and coping strategy on the relationship between workaholism and burnout in campus recreation and Leisure employees. Leisure Studies, 40(5), 714–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.1879908

- Thomson, A., Cuskelly, G., Toohey, K., Kennelly, M., Burton, P., & Fredline, L. (2019). Sport event legacy: A systematic quantitative review of literature. Sport Management Review, 22(3), 295–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.011

- Tod, D., Pullinger, S., & Lafferty, M. E. (2022). A systematic review of the qualitative research examining stakeholders’ perceptions of the characteristics of helpful sport and exercise psychology practitioners. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2022.2145575

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. The Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/259118

- Zhang, F., & Parker, S. K. (2019). Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. Journal of organizational behavior, 40(2), 126–146.