ABSTRACT

The Participatory Occupational Justice Framework (POJF) was first developed and published in 2005 as a scholarly collaboration between Townsend and Whiteford and has since developed over several iterations. It was created to provide the basis for reflective and collaborative action to address instances of occupational injustice, rather than a prescription for intervention. Importantly, the POJF identifies social inclusion as the outcome or “ends” of the processes identified within it. Foundational to the POJF is a critical epistemology aimed at ensuring that those using the framework are cognisant of the power relations ever present in the complex, multi layered environments in which actions to tackle occupational injustices occur. In this article, the authors discuss its key concepts and core processes, and outline the critical, epistemic foundations underpinning the POJF. We then move on to present three case narratives drawn from very different contexts to illustrate how it can be a powerful tool for transformative change at different structural levels in society.

TAMBIÉN PUBLICADO EN ESPAÑOL:

The central purpose of the Participatory Occupational Justice Framework (POJF) is to facilitate social inclusion by raising awareness of and addressing occupational injustices. While it may be self-evident that advancing occupational justice is dependent upon a philosophical commitment, indeed an “agenda” of inclusion (Hocking, Citation2017), social inclusion is a term influenced by a multiplicity of discourses. Put simply, social inclusion focuses on ensuring people having opportunities, resources and capabilities to fully participate in life and that they are supported to be contributing citizens in the society in which they live (Australian Social Inclusion Board, Citation2010; Pereira, Citation2015, Citation2017; Whiteford & Pereira, Citation2012). Social inclusion can also be understood as recognition, capabilities, opportunity, resources, choice, participation, solidarity, rights, and citizenship (Pereira, Citation2015; Pereira & Whiteford, Citation2013; Whiteford & Pereira, Citation2012). Whilst beyond the scope of this article, a full discussion of the centrality of capabilities, opportunities, resources and environments in efforts aimed at addressing occupational injustices and advancing social inclusion are presented by Pereira (Citation2017) in the CORE (capabilities, opportunities, resources, and environments) approach to enablement. Philosophically, the POJF and CORE are closely aligned (Pereira & Whiteford, Citation2018).

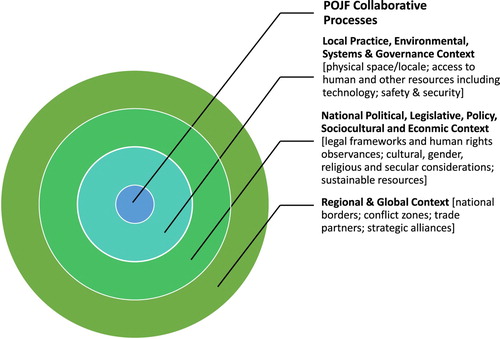

How the POJF is used relates to the processes that underpin it. Ultimately, it is intended as a blueprint for action and differs from other models and frameworks in some significant ways. Besides philosophical and ideological differences pertaining to power sharing, outcome identification and politicisation of effort (as discussed in the next section), one of the key differences of the POJF is its non-linearity. To reinforce the non-linear progression of movement through these processes and the fact that there is no set starting point (reflecting the often organic nature of community interactions), this is usually represented visually in a circular format (see and ; also Townsend & Whiteford, Citation2005; Whiteford & Townsend, Citation2011; Whiteford, Townsend, Bryanton, Wicks, & Pereira, Citation2017). In broad outline, its collaborative, enabling processes are to raise consciousness of occupational injustice, engage collaboratively with partners, mediate on an agreed plan, strategize how to find resources, support implementation and continuous evaluation, and inspire advocacy for sustainability or closure.

Although non-linear, we acknowledge that a typical start would be raising consciousness with respect to a scenario of occupational injustice in a given context. Similarly, a typical closing process would be closure and agreement based on evaluation from all partner perspectives. Ideally, evaluations should address mechanisms to support longer-term sustainability through the use of context appropriate resources for, as Rushford and Thomas (Citation2016) argued, the pursuit of occupational justice must necessarily consider issues of sustainability at all levels inter alia.

As well as being non-linear, the processes may also be re-enacted or adjusted depending on specific contextual forces and events. For this reason, contextual drivers are also foregrounded in the POJF and are identified as the local practice and systems context, and the national, regional, and global socio-cultural, economic and political context (). These contextual “frames” exert a powerful influence on occupation-focussed practitioners and differ dramatically from country to country. At a systems level they may include, for example, availability of resources – fiscal and human, professional regulation, professional organisations and labour unions, institutional codes of ethics and governance regimes. More broadly, contextual influences can also include the prevailing economic ideologies and related policies, cultural and faith-based belief systems that govern social and occupational behaviour, health and social network supports, educational systems and structures, use of social media, telecommunications and transportation, and environmental protections as well as primary resource management. Understanding the complex interactions between these drivers relative to emancipatory action requires a critical epistemic stance. The critical epistemological “Articles” underpinning the POJF are discussed in the next section.

Critical Epistemological Foundations of the POJF

As stated earlier, the POJF was developed with an acknowledgement that advancing occupational justice is an endeavour that cannot be undertaken without a critical orientation, which has been noted as a strength of the POJF within the broader occupational science discourse (Durocher, Gibson, & Rappolt, Citation2014). The need for epistemological reflexivity (Kinsella & Whiteford, Citation2009) has been reinforced more recently by Farias, Laliberte Rudman, and Magalhães (Citation2016) who pointed out that, in order to avoid inadvertent hegemony, “addressing the epistemological foundations that underlie our work is essential to move toward developing and implementing transformative and justice oriented practices in an attempt to more fully consider the complexities of people’s everyday lives” (p. 240).

The six Articles presented in represent a distillation of ways of knowing, being and doing consistent with a critical epistemological basis. These have been developed from earlier iterations of the POJF (Townsend & Whiteford, Citation2005; Whiteford & Townsend, Citation2011; Whiteford et al., Citation2017). Importantly, the first Article foregrounds human rights as central.

Table 1. Epistemological foundations of the POJF

The Articles are, to some extent, aspirational. They do, however, provide a basis against which occupation focussed practitioners can reflect on everyday practices – and the practice architectures (Kemmis & Mutton, Citation2012) within which they take place – that either enable or constrain truly emancipatory action. The POJF, based on a commitment to these articles, is intended to serve as a blueprint for such action. In the next section, we present three case illustrations of how the POJF has been used in different ways but with a common aim of addressing occupational injustices and enhancing social inclusion. See for an overview of their contexts, POJF focus and participants.

Table 2. Summary of POJF case illustrations and contexts

Case illustration 1: Cycling Sisters

Context: Community based programme in Western Sydney, Australia

POJF process focus: Strategize mobilisation of resources

Participants: Muslim women experiencing discrimination and resultant occupational deprivation

In the aftermath of a tragic incident involving a self-proclaimed ISIS sympathiser in Sydney, Australia, Muslim women (especially those wearing hijab) experienced greater levels of overt discrimination whilst in public places. A corollary of this was that many felt anxious going about their everyday occupations in public and began avoiding anything but absolutely necessary outings. Collectively, as identified by Rahal (who was at that time working as an occupational therapy student in Western Sydney) the women were experiencing occupational deprivation relative to the prevailing social climate at the time which had – as a response to recent events – a distinctly overt anti-Muslim flavour. Over time, Rahal worked in planning with the group of women to empower themselves through occupational participation in the public sphere: as a cycling collective (Rahal & Whiteford, Citation2017). The collective subsequently named themselves Cycling Sisters and became a high profile group with other, non-Muslim women joining due to the sense of safety and solidarity experienced by members.

Key outcomes

Cycling Sisters now has several “chapters” in other parts of New South Wales in Australia, and has attracted sponsorship for cycling jerseys and t-shirts. They have a social media presence and are fully self-sufficient. Most recently, new groups have formed of women who swim and bushwalk together.

Rahal’s reflective insights

A 2015 project required occupational therapy students to research a project of their own interest with a focus on “changing the world, one occupational therapist at a time”. Having developed a thorough passion for occupational justice and how its absence strips meaning and purpose from individuals’ lives, I naturally based my research on an issue I, and many people I knew, faced on a regular basis: Islamophobia in Australia and its occupational and mental health implications on Muslim women. The project focused on the growing absence of visibly identifiable Muslim women (any wearing a hijab or niqab) from the community. Instead, they only frequented highly Muslim populated areas and/or retreated from society all together after acts of terrorism were committed, in Australia or abroad. Broadcasts across all forms of paper and digital media, for days at a time, were usually followed by weeks of politicians and leaders using language such as “terrorism”, “team Australia” and “Sharia” to create an “us” and “them” mentality across the Australian population.

Recognising this phenomenon as textbook occupational deprivation, described by Whiteford (Citation2000) as “a state in which people are precluded from opportunities to engage in occupations of meaning due to factors outside their control” (p. 200), I created an experimental cycling Facebook group called Sydney Cycling Sisters (SCS). The goal was to encourage Muslim women of all backgrounds, shapes and sizes back into the wider community through participation in bike riding in a safe and fun environment. With 150 “likes” on the Facebook page, the first ride attracted three women including myself. An official launch of the group was planned for 16 May 2015 and promoted through a strong online presence via the SCS Facebook page. An online registration form was developed through Google Docs. Thirty-four women registered to attend, with 21 taking part on the day. The event was an enormous success and overnight the likes doubled, as women become excited and motivated by the photographs posted on line.

Sydney Cycling Sisters, which is inclusive of all women, has since participated in the Sydney to Gong ride 3 years in a row, raising close to $10,000.00 for Multiple Sclerosis research, and enriching the participants’ experience as feelings of inclusiveness through contribution are increased. The group has also participated in three consecutive annual Heart Foundation Gear up Girl rides, The Spring Cycle, The Tumut Cycle Classic and regular organised rides throughout Sydney, where they have become recognised and well received by the broader cycling community. Sydney Cycling Sisters have also attracted media attention, including a radio and television interviews ().

SCS is an example of how POJF can be used to facilitate a participatory driven initiative to guide groups at risk of marginalisation by providing them with tools to organically navigate their own successful occupations and find meaning once again. The group continues to use Facebook to recruit new riders and celebrate their successes (). SCS now also has Whatsapp groups to communicate about rides or anything cycling related, to organise and lead rides, and to discuss the direction the group is heading.

Case illustration 2: Occupation focussed life skills programme

Context: Non-Government Organisation (NGO) leading a state-wide refugee resettlement collaboration in Queensland, Australia

POJF process focus: Raise consciousness of occupational injustice

Participants: Newly arrived people from refugee/forced migration backgrounds

Through her work with people experiencing forced migration and the many impacts involved in the occupational transition (Suleman & Whiteford, Citation2013), Suleman identified that one of the biggest impediments to full participation was a lack of familiarity with Australian law, and health, welfare and transport systems, and the skills to negotiate them. Based on stakeholder experiences and feedback, with colleagues Suleman developed the Life Skills Program aimed at providing new arrivals with a toolkit to not only survive, but to ultimately flourish, in their new environments. Supported by the considered use of interpreters and cultural support workers, the programme runs over the equivalent of 3 days and, as well as covering core skills, facilitates connectedness with others through community building events such as barbecues and picnics (). Where there are special needs, however (such as a family who has a child with a significant disability), participants cover content with facilitators in either libraries or their own homes. Participants have their awareness, knowledge and application assessed at the end of the programme through both informal, non-threatening approaches (such as group quizzes) as well as more thorough formal strategies (including written assessments). Participants may be individuals, couples or family units, but the ethos developed by Suleman and colleagues is one of collaboration and co-occupational engagement.

Figure 5. Life Skills program for Humanitarian Settlement Programme participants in session at Multicultural Development Australia

Key outcomes

The Life Skills Programme run within Multicultural Development Australia, an NGO in Queensland Australia, was developed in its current form in 2011 and, through Suleman’s input, has been informed by the POJF over time. The programme has received funding (indicative of the POJF Process Mobilize Resources) from federal sources and is recognised as having provided an excellent basis from which participants are able to engage in occupations of meaning and necessity in their new communities. It is estimated that, to date, approximately 6,000 people who have arrived in Queensland, Australia through the Humanitarian Settlement Service have successfully completed the Life Skills Programme.

Suleman’s reflective insights

Multicultural Development Australia forefronts the broad aim of engaging the Queensland multicultural community in positive and productive ways. This is demonstrated through various programmes including individual case management, skill development and training, community engagement, youth support and employment. These facets of the organisation all have underpinnings in enabling marginalized groups of people to participate as valued members of society and implicitly working towards an occupationally just world.

Although the life skills programme is part of a larger government-funded settlement service, the organisation has developed a collaborative method of delivering the programme to enable learning, skill development and empowerment. While the programme focuses on areas of knowledge, skills and attitudes needed for life in Queensland, it is motivated by issues of occupational injustice because without a certain skillset and knowledge base, life in Queensland (or a new country anywhere in the world) would be limited in equitable opportunities and privileges to participate meaningfully in everyday life. This is not to say that new arrivals could not flourish without input; but community-based programmes such as the life skills programme in fact supports the strengths and therefore settlement experience of all new arrivals. It provides inclusive opportunities to learn and ask questions, a safe environment to connect with culturally and linguistically diverse communities other than their own, and the resources to put their best foot forward in a life-long journey toward realising their potential in a new environment. At an organisational level the multiple disciplines and professions – from social work to international development – bring with them multiple influences of the various sciences. Increasingly, however, I have introduced an occupational perspective into my work at Multicultural Development Australia and this is being recognised cross-organizationally for its universality and application beyond life skills and across all aspects of settlement (Suleman & Suleman, Citation2017). The potential for knowledge exchange between workers from different disciplinary backgrounds is significant as, in the relatively new field of resettlement, new knowledge is being generated on a daily basis.

The principles of the POJF consequently run parallel to Multicultural Development Australia’s settlement goals and more specifically to the life skills programme. As Whiteford and Townsend (Citation2011) explained, the need for a framework that moves beyond processes that target performance components or individual function, and focuses instead on social inclusion, was much needed for an occupational perspective to be embraced in a settlement context. The framework also adopted language common across various professions and therefore the potential for understanding is great, in what is still considered to be an emerging area of practice. Considerations of population-based data in the POJF categorise the framework as one that can be used in areas where the local but also global contexts are contiguously significant, as is the case with refugee resettlement. A recent longitudinal study of humanitarian migrants conducted by Australia’s Department of Social Services (Citation2017) has generated locally situated but internationally significant findings, illuminating those factors that helped and hindered settlement and therefore engagement in everyday life in Australia. A snapshot of the data indicated that enabling factors for settlement included feeling safe (79%), their children being happy (60%), having family in Australia (52%), feeling welcome in the community (48%), and having good living conditions (45%). Barriers to settlement included language barriers (66%), worrying about family or friends overseas (51%), being homesick (33%), lack of employment opportunities (28%) and financial problems (28%).

Such information can be powerful in informing better collaborative planning, delivery and evaluation of a life skills programme where the main aim is to address occupational injustices related to settlement stressors associated with political, structural and environmental constraints. In other words, using population data in conjunction with a guiding framework such as the POJF and collaborative approaches with newly arrived families and individuals, targeted programmes can be designed to directly address both peoples’ occupational needs and capabilities to engage meaningfully in their new environment.

Case illustration 3: Occupation focussed practice initiative

Context: State Government funded forensic mental health service

POJF Process Focus: Support implementation and continuous evaluation

Participants: Occupational therapists working in a forensic hospital in New South Wales Australia

Although the rehabilitation unit where Jones and her fellow occupational therapists worked was purpose built for forensic patients (where the term “patient” is used very specifically as the unit is situated close to a prison and being a patient is an important differentiator), over time the rehabilitative aim had diminished. Although this was due to a range of institutional factors outside the control of the occupational therapy team, they collectively experienced a “drift” from occupation itself. A number reflected that they had become, unwittingly, “hegemonic agents” and as such were inadvertently reinforcing powerful discourses that in some ways marginalised the occupational needs of their patients. A critical turning point came when, through engaging with occupational literature and specifically, the POJF, the team decided to refocus on occupation.

The approach the team took was Practice Based Enquiry, which has been noted by scholars as requiring a strong commitment over time but through which significant practice transformation can occur (Perkes et al., Citation2015). The process is both a form of evaluation of current practice – in all its complexity – as well as an interrogation of the key assumptions underpinning it and the philosophical and theoretical bases informing it. Iterative cycles of reflection, critique, and transformative action occur, with data being captured in the form of practice narratives, group discussions, written reflections and practice artefacts (formal reports and protocols, for example). Early in the process, participating staff galvanised into action through the formation of a Community of Practice Scholars, collectively pursuing the aim of “reclaiming occupation” in their service in order to better meet the occupational needs of their patients. Inter alia, a strong commitment to a human rights frame as a basis for action, was also centralised.

Key outcomes

Since participating occupational therapists at the forensic hospital commenced on their journey of reclaiming occupation in the service they provide, they have become clearer about their unique contribution in the institution; provided more occupation focussed opportunities for patients including a café, recycled clothing shop and market garden; are more confident in using occupation focussed language to describe their work; are more effective in their communications with other team members and with management; and have become practice scholars within the public domain, disseminating and discussing their work through publications and conference presentations.

Jones’ reflective insights

The POJF provided a scaffold to support us in conceptualising access to occupations as a basic human right. It helped us to identify that this is (and should be) our utmost goal, not only at work but also in life. In the forensic context, occupational injustice was something we had observed and felt uncomfortable with for a significant period of time, but did not have a name for. The POJF has raised awareness of this injustice, and helped us to prioritise the need to combat its effects by developing strategic actions to make the necessary changes. Through utilising the POJF, we adopted this new way of thinking, which gave us the permission, strength and structure to address the occupational injustice we observed.

The occupational therapy team has significantly changed focus from a narrow and individualistic approach to advocating for the needs of a vulnerable population within society. Whereas previously our scope was thought to be the prescription of meaningful activity to the individual, with very limited choice due to the environmental restrictions, the POJF allowed us to broaden our reach, yet sharpen the focus on providing opportunities to engage in occupation so that the health and well-being of this population can improve. See and .

We utilised a practice based enquiry approach to evaluate current practices within our unique “microcosm”. Like any institution, the hospital had its own unique political, social and physical complexities. There were assumptions and unspoken rules that were not regularly challenged or reviewed, and therefore a certain type of culture had been created. We formed a safe and non-threatening environment with a Community of Practice Scholars, and were able to engage in critical reflection of practice. This was also a very useful way to practice the techniques needed to challenge the effects of institutionalisation on our professional beliefs, behaviours and expectations and, ultimately, reduce the impacts of institutionalisation on patients’ lives. Subsequently we have been able to contribute to enhancing patients’ abilities to participate in a meaningful life following release into the community, and to maintain or regain their occupational identity as people who can contribute to the community and be an asset to society.

The practice based enquiry approach brought a sense of shared purpose. We achieved a greater sense of cohesion as we developed a common vision of an occupationally-just service. As a team, we developed a greater sense of purpose; with that purpose came a stronger conviction about what was “right” to provide; which in turn gave us strength in character and voice in justifying our unique contribution to patient care, and our expectations of the multidisciplinary team. Our recently graduated practitioners have developed a strong professional identity with occupation at the core and occupational justice as a foundation to their approach.

The most significant shift in our thinking, as a team, has been in regards to every person having the right to engage in occupations. This should occur, no matter how restrictive the environment, and is necessary to maintain function and physical and psychological well-being. We now feel so strongly about the occupational needs and rights of not only every individual that we work with, but of this population as a whole, that we have committed to publicly sharing our journey – our experiences and learnings – and to encouraging other practitioners that we meet to do the same. We owe it to our patients, but importantly to our profession, to share with the world our professional contribution to eradicating the occupational injustices that occur.

Conclusion

Occupational justice as a concept has emerged in literature since the late 1990s (Durocher et al., Citation2014) and, alongside other discursive contributions, has been promulgated through the development of the POJF from 2005 to the present day. In this article, we have presented an overview of the POJF including an indication of the critical epistemology that underpins it in the form of linked Articles, the first of which is unambiguously focussed on human rights. Such a prioritised focus is necessary in support of moral claims relative to occupational participation and inclusion (Galvin, Wilding, & Whiteford, Citation2011; Hammell, Citation2015; Hocking, Citation2017).

From the case illustrations presented, the authors hope to reinforce the utility of the POJF across settings and contexts. Whilst community, NGO and institutional environments vary enormously in everything from resource availability to systems of governance to legislated compliance requirements, justice focussed action is still possible when galvanised by a unifying set of principles and a critical orientation to power relationships. Indeed, the original architects of the framework had the intention that it act to stimulate thoughtful interaction between groups of people for transformative ends whatever the context; sociocultural, political or economic (Townsend & Whiteford, Citation2005). The intention was also that collaborative dialogue underpin all aspects of all the processes, all of the time.

Such intentions are clearly aspirational. In order to advance understandings of how the POJF can be a relevant and valued tool through which occupational justice can be advanced, however, continued research and scholarship is clearly requisite. A priority in such research will be to engage with stakeholders currently excluded or denied occupational opportunities, such as those in the case studies presented in this article, to more fully illuminate the diversity of their lived experiences and concomitant concerns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Gail Whiteford http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6136-1844

References

- Australian Social Inclusion Board. (2010). Social inclusion in Australia: How Australia is faring. Canberra, Australia: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Department of Social Services. (2017). Building a new life in Australia (BNLA): The longitudinal study of humanitarian migrants. Retrieved from https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/defaultfiles/documents/11_2017/17385_dssbnla_report-web-v2-pdf

- Durocher, E., Gibson, B. E., & Rappolt, S. (2014). Occupational justice: A conceptual review. Journal of Occupational Science, 21(4), 418–430. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2013.775692

- Farias, L., Laliberte Rudman, D., & Magalhães, L. (2016). Illustrating the importance of critical epistemology to realize the promise of occupational justice. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 36(4), 234–243.

- Galvin, D., Wilding, C., & Whiteford, G. (2011). Utopian visions/dystopian realities: Exploring practice and taking action to enable human rights and occupational justice in a hospital context. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58, 378–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00967.x

- Hammell, K. W. (2015). Participation and occupation: The need for a human rights perspective. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 82(1), 4–5. doi: 10.1177/0008417414567636

- Hocking, C. (2017). Occupational justice as social justice: The moral claim for inclusion. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(1), 29–42. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2017.1294016

- Kemmis, S., & Mutton, R. (2012). Education for sustainability (EfS): Practice and practice architectures. Environmental Education Research, 18(2), 187–207. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2011.596929

- Kinsella, A., & Whiteford, G. (2009). Knowledge generation and utilisation in occupational therapy: Towards epistemic reflexivity. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56, 249–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00726.x

- Pereira, R. B. (2015, November). Enabling social transformation through occupation for citizens living with mental illness. Keynote address presented at the Occupational Therapy Australia Mental Health Forum: Mental Health OT – Supporting participation, wellbeing and inclusion. University of Technology Sydney, Sydney Australia.

- Pereira, R. B. (2017). Towards inclusive occupational therapy: Introducing the CORE approach for inclusive and occupation-focused practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64, 429–435. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12394

- Pereira, R. B., & Whiteford, G. E. (2013). Understanding social inclusion as an international discourse: Implications for enabling participation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(2), 112–115. doi: 10.4276/030802213X13603244419392

- Pereira, R. B., & Whiteford, G. E. (2018). Advancing understandings of inclusion and participation through situated research. In N. Pollard, H. van Bruggen, & S. Kantartzis (Eds.), Occupation-based social inclusion. London: Whiting & Birch.

- Perkes, D., Whiteford, G., Charlesworth, G., Weekes, G., Jones, K., Brindle, S., … Ray, M. (2015). Occupation-focussed practice in justice health and forensic mental health: Using a practice-based enquiry approach. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 71(2), 101–107. doi: 10.1080/14473828.2015.1103464

- Rahal, C., & Whiteford, G. (2017, July). Tackling racism, occupational deprivation and advancing occupational justice. Paper presented at the 27th National Occupational Therapy Conference. Perth, Australia.

- Rushford, N., & Thomas, K. (2016). Occupational stewardship: Advancing a vision of occupational justice and sustainability. Journal of Occupational Science, 23(3), 295–307. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2016.1174954

- Suleman, A., & Suleman, S. (2017, October). Why orientation is critical to settlement success: An occupational therapy perspective. Paper presented at the Humanitarian Settlement Program Forum, Brisbane, Australia.

- Suleman, A., & Whiteford, G. E. (2013). Understanding occupational transitions in forced migration: The importance of life skills in early refugee resettlement. Journal of Occupational Science, 20(2), 201–210. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2012.755908

- Townsend, E., & Whiteford, G. (2005). A participatory occupational justice framework: Population–based processes of practice. In F. Kronenberg, S. Simό Algado, & N. Pollard (Eds.), Occupational therapy without borders: Learning from the spirit of survivors (pp. 110–126). London, UK: Elsevier.

- Whiteford, G. (2000). Occupational deprivation: Global challenge in the new millennium. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(5), 200–204. doi: 10.1177/030802260006300503

- Whiteford, G. E., & Pereira, R. B. (2012). Occupation, inclusion and participation. In G. E. Whiteford & C. Hocking (Eds.), Occupational science: Society, inclusion, participation (pp. 187–207). Chichester, UK: Blackwell.

- Whiteford, G., & Townsend, E. (2011). Participatory Occupational Justice Framework (POJF 2010): Enabling occupational participation and inclusion. In F. Kronenberg, N. Pollard, & D. Sakellariou (Eds.), Occupational therapies without borders - Volume 2: Towards an ecology of occupation-based practices (pp. 65–84). London, UK: Elsevier.

- Whiteford, G., Townsend, E., Bryanton, O., Wicks, A., & Pereira, R. (2017). The Participatory Occupational Justice Framework: Salience across contexts. In D. Sakellariou & N. Pollard (Eds.), Occupational therapy without borders: Integrating justice and inclusion with practice (2nd ed., pp. 163–174). London: Elsevier.