Castaways and Cross-Cultural Interactions

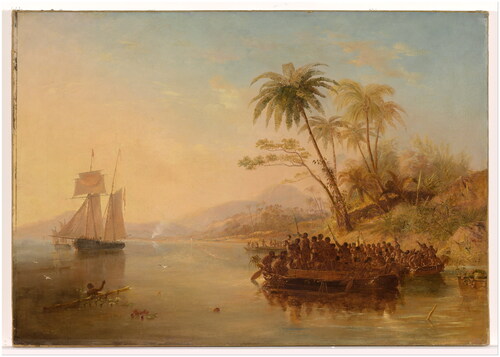

Prominent British maritime artist John Wilson Carmichael’s (1799–1868) two paintings, The Rescue of William D’Oyly, by the Isabella, from Murray Island, Torres Strait, 1836 (1839, ), and The Rescue of William D’Oyly (1841, ), depict a dramatic and once widely known episode in colonial Australian history. In 1834, whilst en route from Sydney to India, the barque Charles Eaton was destroyed in rough seas on a reef near the eastern tip of Cape York in northern Australia. It was unknown if there were survivors, although contradictory reports suggested that there might yet be hope. Almost two years later, in June 1836, the Government Schooner Isabella arrived at Mer (Murray Island) where Captain Lewis and his crew found two of the survivors, William D’Oyly (aged four) and John Ireland (aged seventeen), who were living with the Meriam people.Footnote1 Struggling to recall English, Ireland related his memories of events that ensued following the Charles Eaton’s demise, including the killing of all the adult survivors and John and William’s subsequent adoption into a Meriam family.

Figure 1. J. W. Carmichael, The Rescue of William D’Oyly, by the Isabella, from Murray Island, Torres Strait, 1836, 1839. Oil on canvas, 44.2 x 70.4 cm. Sydney: Silentworld Foundation. Photo: Silentworld Foundation.

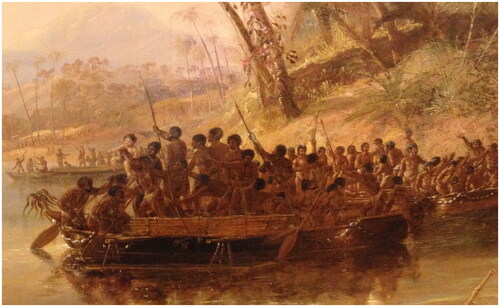

Figure 2. J. W. Carmichael, The Rescue of William D’Oyly, 1841. Oil on canvas, 73.9 x 105.4 cm. National Gallery of Australia. Photo: Wiki commons.

John Ireland’s tale, which encompassed violence that fed colonial fears, as well as expressions of great compassion involving the adoption and care of the boys, captured public attention in Australia and abroad. Written accounts of the shipwreck and its aftermath included Ireland’s testimony (published as a children’s book), reports from rescue ship personnel, newspaper articles, pamphlets and other publications.Footnote2 There do not appear to be any publicly available paintings of the event apart from those by Carmichael, which are examined here. Like the written accounts, Carmichael’s works envisaged these encounters from a European worldview, and there is little documentary material revealing Islander perspectives of the events, although some information is conveyed through the European accounts, albeit in a mediated way. The artworks dramatically depict the boys’ rescue, presenting a seemingly joyful conclusion to a narrative of loss and recovery. However, the broader encounters underlying these scenes reflect a more complex series of engagements between Torres Strait Islanders and Europeans in nineteenth century Australia.

This essay examines Carmichael’s paintings in conjunction with several of the written accounts to consider how the artist highlights some aspects of the incident at the expense of others. It is argued that through this selective emphasis, Carmichael conveys a triumphal image of empire, foregrounding heroic rescue from a state of captivity rather than care, and reinforcing European views of cross-cultural interactions in colonial Australia. A textual analysis of the works is undertaken to highlight codes and conventions within the paintings that collectively communicate these ideas.

There is much to be gleaned from examining the role of images in supporting the colonial project and expressing attitudes about cultural and racial difference. In European Vision and the South Pacific, Bernard Smith notably demonstrated how paintings, illustrations, scientific images, and the conventions they employ were central in underpinning European perceptions of the South Pacific from the eighteenth century onwards.Footnote3 Building on Smith’s work, the 1985 publication Seeing the First Australians argued that European and settler images of Indigenous Australians have been mediated by ‘social, cultural and political preoccupations’ and reflect a failure to see.Footnote4 Continuing in this vein, a considerable body of scholarship has addressed the role of art and visual culture in representing European and Indigenous interactions in colonial Australia.Footnote5 Analysis of colonial images can provide insights into how British imperial power was exercised and shed light on colonial views of cultural ‘Others’ and of the ways in which ‘images of such Others were fashioned and disseminated’.Footnote6

Ireland and D’Oyly were recovered in 1836, the same year that arguably Australia’s best-known castaway, Eliza Fraser, was ‘rescued’ after spending several weeks with Butchulla and Kabi Kabi people on K’gari (Fraser Island) and the adjacent region. Written and visual accounts of this episode were often sensationalised and constructed as captivity narratives with related tropes of savagery and cannibalism, casting Fraser as the helpless victim of Indigenous aggression.Footnote7 One such narrative was by British journalist John Curtis, who linked the Fraser and Charles Eaton stories, arguing for the need for ‘civilising’ forces to subdue Indigenous Australians and convert them to Christian ways. Such representations supported arguments for dispossession and continue to feed into present day prejudices.Footnote8

Torres Strait Islander academic Professor Martin Nakata details how some texts describing the fate of Charles Eaton castaways invoked emotive language that emphasised barbaric savagery and cannibalism.Footnote9 Nakata argues that this focus influenced subsequent accounts, such as reports from the Haddon anthropological expeditions in the late nineteenth century, and later twentieth century historical scholarship, positioning ‘the Islander lifeworld […] in relation to colonial’ understandings.Footnote10 Carmichael’s Rescue paintings are examined here to consider how they contribute to a wider body of colonial maritime imagery that represents cross-cultural encounters through particular ‘frames’, reinforcing asymmetrical power relations and influencing European perceptions of Australian First Nations peoples, inscribing them, as Nakata attests, ‘in a historical schema that is not their own’.Footnote11

Shipwreck and Castaway Narratives

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as imperial expansion increased, shipwrecks were a common occurrence. Texts exploring this subject, including the fate of survivors and interactions with First Nations peoples, garnered considerable public interest and formed a popular genre within the burgeoning mass print culture.Footnote12 Additionally, shipwreck and castaway narratives, both visual and written, were distinctive in reflecting a form of rupture from the status quo. Maritime historian Margarette Lincoln argues that they recorded ‘moments of crisis in which social conventions are tested in isolation from the conditions that normally support them’.Footnote13 As a consequence, assumptions about national character, social roles, and civilised behaviour were challenged and placed at risk. In colonial-era accounts, anxieties were further exacerbated when shipwreck survivors encountered First Nations peoples, triggering fears of the unknown uncivilised other and perpetuating stereotypes of inhumane, unfeeling savages.Footnote14 As such, dramatic stories and imagery involving contact or captivity often contributed to ‘the process of “fixing” relations between Europe and other continents’ and the formation of racial stereotypes.Footnote15

Shipwreck and castaway incidents also unsettled a sense of British naval and commercial maritime prowess, which was significant in underpinning the nation’s military and economic power and sense of national identity.Footnote16 The expansion of empire was accompanied by a ‘burgeoning maritime mythology’, reflecting an ‘image of the British as a sea-faring people, a Providentially-favoured island race whose resourcefulness, resilience and moral character derived in no small part from the challenges they encountered on the sea’.Footnote17 Consequently, depictions of maritime rescue from shipwreck events and an implied return to civilisation could reaffirm this potent national image, reasserting a sense of moral certainty and imperial dominance. Such images also contributed to the broader field of colonial maritime imagery which, Geoffrey Quilley argues, played a central role in championing British imperial ambitions.Footnote18 Accordingly, historical conditions, public interest, and the dramatic power of shipwreck and survivor tales made them a worthy subject matter for artists.

In colonial Australia, shipwreck and castaway narratives involving interactions with Indigenous Australians, such as the Eliza Fraser and Charles Eaton episodes, also captured the public imagination while also fuelling fears and misunderstandings. Despite such anxieties, there were various instances in which European castaways survived because of the sustained assistance they received from Indigenous Australians.Footnote19 In 1823, for example, convicts Pamphlett, Parsons and Finegan were substantially aided by various First Nations groups in the Moreton Bay region. Shipwreck survivor Barbara Thompson lived with the people of Muralug (Prince of Wales Island) for several years from 1844, and castaways James Morrill and Narcisse Pelletier each spent seventeen years living with First Nations peoples in different parts of far north Queensland from 1846 and 1858 respectively.

Although this support was sometimes acknowledged in colonial accounts, interactions in which Europeans were dependent on First Nations’ knowledge and care often unsettled distinctions that colonial frontier societies sought to maintain between settlers and the original inhabitants.Footnote20 Most narratives were inevitably mediated by the individual and cultural lens of the writer or artist and, as such, informed by the oppositional constructs of ‘civilised European’ and ‘primitive savage’. Such perspectives also underpinned the composition of Carmichael’s Rescue paintings.

The Wreck of the Charles Eaton

Before examining Carmichael’s works, the incidents surrounding the wreck of the Charles Eaton and its aftermath will be briefly outlined to better clarify the subject and context of the paintings. In August 1834, fourteen-year-old cabin boy John Ireland was aboard the barque Charles Eaton when it was wrecked on Great Detached Reef near Raine Island.Footnote21 The ship, which was in the service of the British East India Company, had berthed at Cape Town, Hobart Town, and Sydney before voyaging north along the east coast of Australia en route to China and India. As it became clear that the Charles Eaton could not be saved, a raft was constructed, although it couldn’t hold all the survivors. Those who departed included the ship’s captain and British passengers Captain Thomas D'Oyly of the Bengal Artillery, his wife Charlotte, and their sons George (aged eight) and William (aged almost three).Footnote22 A week later a second raft was built from the wreckage and was subsequently approached by some Torres Strait Islander men, who guided the crew to Boydan Island, where all the survivors on this raft were killed by the Islanders, apart from Ireland and another cabin boy, John Sexton. The boys then witnessed the ritual anthropophagy of the adult castaways.Footnote23 Ireland and Sexton were subsequently taken to Pullan Island, where they found the D’Oyly brothers being cared for by local women, although a similar fate had befallen the adults from the first raft. Some historians have suggested that the castaways were likely slain because of prior violent encounters that led the Islanders to believe Europeans and their weapons were highly dangerous.Footnote24

The boys were eventually paired off. Ireland and William D’Oyly were given the names Waki and Uass and subsequently traded, for two bunches of bananas, to a powerful man named Duppa from Mer (Murray Island).Footnote25 Duppa and his wife Panney adopted and cared for the boys, along with their own five children. William was also looked after by a neighbour called Oby and a strong bond grew up between them, so much so that the child ‘seemed here to have quite forgotten his father and mother’.Footnote26 Over the next two years, the boys learned the local language and integrated into the daily life of the Meriam people. William played with the other children and Ireland learned important skills. In his testimony, Ireland explained the extensive care he received:

My new master, (I should have called him father, for he behaved to me as kindly as he did to his sons) gave me a canoe, about sixty feet long, which he purchased in New Guinea […] He also gave me a piece of ground on which he taught me to grow yams, bananas and cocoa-nuts, […] he taught me to shoot with the bow and arrow, and to spear fish.Footnote27

Maritime artist John Wilson Carmichael (1799–1868)

This is the setting for Carmichael’s luminous paintings, although the scenes they depict differ in significant ways from the main written accounts, which, although mediated, provide some indication of the Islanders’ perspectives. The first Rescue painting was created in 1839, not long after William was returned to the care of relatives in Britain in December 1838. Newspaper reports of this event provided closure for members of the British public who had ‘felt a deep interest in the fate of the Charles Eaton’.Footnote31 It is likely that Carmichael may have drawn on such reports to inform the Rescue paintings.Footnote32 He also held an extensive library, including Voyages of Cook, so it is possible he may have acquired or viewed some of the accounts of the Charles Eaton rescue published soon after the event. Carmichael sought accuracy in his works, which led him to paint a second version of a famous shipwreck rescue off the British Coast after he became aware of more precise details of the event. This also enabled him to focus more on the rescuers rather than the wreck, as the former had ‘captured the public’s imagination’.Footnote33 Public interest and perceptions would most likely have influenced Carmichael’s choices in subject matter for the Rescue paintings, and the second version may also have been informed by further research.

At the time, Carmichael was an established artist who primarily specialised in maritime subjects. The son of a shipwright, he was born in Newcastle-on-Tyne and apprenticed in his father’s trade to Newcastle shipbuilders Richard Farrington & Brothers. From an early age he had direct experience of the sea in a variety of vessels, which enhanced his familiarity with the maritime world. Encouraged by the Farringtons and Newcastle's leading landscape painter, Thomas Miles Richardson, Carmichael took up painting and steadily built a reputation while generating a prolific output. Between 1835 and 1839 he exhibited a total of 21 paintings at the Royal Academy, although the 1839 Charles Eaton painting was not amongst them. Encouraged by his success, Carmichael moved to London in 1846 to advance his career, although he eventually returned to northern England where his work was ultimately more popular.Footnote34

Like many nineteenth-century British maritime artists, Carmichael undertook extensive research and sought precision in representing watercraft and the effects of weather. He was influenced by seventeenth-century Dutch sea and landscape painting, as well as British Romanticism, particularly the work of J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851). Along with other British maritime artists, Carmichael employed compositional techniques found in Dutch painting, such as alternating sections of sunlight and shadow to lead the eye into an image. Additionally, elements were introduced to enliven the foreground, such as floating buoys, drifting wreckage, and scattered seagulls. Clouds could be imaginatively rendered to create a sense of atmosphere to ‘set the mood for the entire picture’.Footnote35 In the Rescue works, Carmichael is attentive to detail and technical accuracy in his depiction of watercraft. They feature as dominant elements within visual narratives that also incorporate various invented elements.

Carmichael’s Rescue paintings could also be considered within the context of the imperial picturesque. Historian Jeffrey Auerbach posits that conventions of the picturesque, common in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century British and European landscape painting, were applied as a lens through which visualisations of varied locations throughout the British Empire were presented ‘in remarkably similar ways’. Picturesque paintings involved the structuring of nature according to prescribed conventions of proportion and composition, and the inclusion of soft lighting reflective of the ‘golden light of the Roman Campagna’. William Hodges’ Tahiti Revisited (c. 1776), with its distinct foreground, strong midground, hazy rugged mountainous background, harmonious balance, and distinct directional lines is cited as one example of this trope applied to a depiction of distant lands. Auerbach argues that although some exotic elements were incorporated in such works, the familiar idiom of the picturesque as applied to representations of the diverse reaches of the British Empire functioned to homogenise these territories, creating a sense of familiarity that played down fears of conflict and difference.Footnote36

Although they are primarily maritime rather than landscape paintings, it could be argued that aspects of the imperial picturesque are manifest in the Rescue paintings, with their distinctive division of space into differentiated foreground, midground, and muted background, leading lines and Italianate lighting. Unlike Hodges, who was a member of Cook’s second Pacific voyage and was thus able to view the Tahitian and other Pacific landscapes first-hand, Carmichael never visited Australia, so the Rescue paintings were informed by his imagination, available information, and prevailing cultural perspectives. Another Carmichael work, ‘Erebus’ and ‘Terror’ in New Zealand, August 1841 (c. 1847), based on the James Clark Ross expedition (1839–42) exploring Antarctic waters, employs a similar compositional structure, soft luminous lighting, and joyful mood. The work, which is now housed in the collection of the Royal Museums Greenwich, is described as exuding ‘an air of calm and peaceful stillness, tinged with a golden glow indicating that the meeting between the visiting ships and local people is one of friendship’. However, this framing by Carmichael differs from Ross’s 1847 account of the expedition, which referred to the Māori as hostile and intent on driving the Europeans from their land.Footnote37 In a similar way, the Rescue paintings emphasise a benevolent calm rather than the shared emotions of grief portrayed in the written narratives.

In conjunction with conventions of the imperial picturesque, elements of Romanticism are also evident in the Rescue paintings in the glowing atmosphere, exotic subject matter, implied extremes of experience faced by the castaways, and the dwarfing of the human drama within a vast natural scene. In both works, the Isabella is anchored in calm waters, and the soft lighting and muted pastel colourings evoke a tranquil idyll. They represent scenes imagined through European eyes, in part because they are more suggestive of European atmospheric conditions than the intense light of tropical Australia. Accounts differ regarding the time when William was brought to the ship. According to the log of one of the Isabella’s crew it was at about 11 am, whereas maritime historian Alan McInnes claims it was 4 pm.Footnote38 Carmichael’s rendering of golden-hued, low angled lighting implies early morning or evening, perhaps evoking the idea that the rescue of William (and John) represents closure and the dawning of a better life on their return to ‘civilisation’.

In creating the Rescue works, Carmichael also responded to, was influenced by, and benefitted from broader socio-economic and historical conditions. With the growth of British imperialism there was an increasing demand for maritime subjects, including striking scenes of the outer reaches of empire and imagery that affirmed a sense of imperial power and maritime mastery.Footnote39 Many of the artist’s patrons were mining engineers, industrialists, and landowners, whose wealth was directly or indirectly boosted by British imperial expansion. The original owner of the Rescue of William D’Oyly was William Cochran Carr, who profited from Britain’s industrial and imperial ascendancy. The young farmer and businessman from the Newcastle area later became a firebricks manufacturer and owner of the Benwell Colliery. His wife’s name, Isabella, was the same as that of the rescue ship, which may have added a personal connection to the subject matter.Footnote40

The Imperial Gaze: Seeing and Being Seen

Besides encompassing elements of the imperial picturesque, both the Rescue paintings could be considered as encapsulating aspects of the imperial gaze. Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright explain the field of the gaze in relation to images as encompassing practices of ‘relational looking’. Such processes, they argue, involve power relations, giving viewers of images ‘a sense of themselves as individual human subjects in the world in a particular historical moment and cultural context’—in this case at the height of British colonial expansion.Footnote41 Referring to British explorers’ narratives of ‘“discoveries” which were “won” for England’, Mary Louise Pratt envisages a surveying and subordinating ‘imperial eye’ enacted by a male explorer who looks down at the landscape and, by implication, the indigenous peoples within it. According to Pratt, these practices envisage a ‘relation of mastery predicated between the seer and the seen’.Footnote42 In a similar vein, E. Ann Kaplan also conceives of colonialism’s ‘imperial gaze’ as relational looking: ‘a one way subjective vision’ influenced by the observer’s value system and as such representing a kind of not knowing, or denial of ‘other’ perspectives.Footnote43

The composition of Carmichael’s Rescue paintings, whether consciously or not, is informed by cultural attitudes and conveys such ‘relations of mastery’. Although the titles emphasise young William, the Government Colonial schooner Isabella features as the locus of power in both works, and each painting has been constructed to lead the viewer’s eye directly to it. In the earlier work the Isabella is prominent because of its size, but this is reinforced by the angling of the canoes, the Islanders’ gesturing arms, the directional positioning of the ship’s distant cutter, and the foreground grouping of locals around a slanted semi-submerged log. Together with the shadowy reflections of the ship’s sails, these elements lead diagonally to the towering splendour of the Isabella, with its vivid red British ensigns hanging vertically to indicate a calm environment, despite the excitement displayed by all involved in this drama. In the 1841 work, the Islander outriggers located in the foreground give more emphasis to the tiny figure of William. However, a similar use of diagonals to position the outriggers and gesturing arms of the Islanders again directs the viewer’s gaze to the Isabella. In both paintings the ship’s guns are visible, signalling the power of the colonial government while also referencing actual events.

The emphasis in the titles on D’Oyly over Ireland can be associated with class differences: Ireland was a lowly-ranked crew member, whereas D’Oyly was the infant son of a well-connected British military captain. A key factor influencing the despatch of the Isabella had been the advocacy of William’s uncle, who implored the lords of the Admiralty to fund the rescue of the shipwrecked people ‘from the hands of the savages’.Footnote44 So although the perceived capture of any British subject was considered alarming, the fate of the orphaned William was given significant attention.Footnote45

Carmichael’s paintings also present visible racial and cultural distinctions even though accounts indicate that the boys had been acculturating into Meriam life both socially and visually. In their two years on Mer their physical appearance had changed considerably.Footnote46 Ireland explains that the effect of the sun on William’s skin ‘became very apparent. In a few months he could not be distinguished by his colour from the other children; his hair being the only thing by which he could be known at a distance, from its light colour’.Footnote47 William Brockett, a visitor on the Isabella who wrote an account of the rescue mission, observed that young William ‘appeared much burnt by the sun’, while another report described John as having ‘skin the colour of mahogany’.Footnote48 However, in Carmichael’s images a pudgy, pink-skinned, dark-haired, and passive William is held aloft, and both boys are differentiated from their adopted carers through their lack of tribal ornaments and the paleness of their skin.Footnote49

John, who only appears in the earlier painting, is also distinguished by his pristine white shirt, which contrasts dramatically with the dark, decorated bodies of the Islanders.Footnote50 Clothing, or the lack of it, was another marker of difference within colonialism’s imperial gaze. Within this form of relational looking, an absence of clothing and the presence of tribal ornamentation signified primitivism, savagery, and a lack of civilisation and Christian morality in non-European others.Footnote51 Ireland explains that on Mer his ears had been pierced and hung with tassels and his body was adorned with various ornaments, while elsewhere he was described as being ‘naked, with the exception of a piece of skin round his waist’.Footnote52 Despite this, Carmichael presents Ireland as clothed, seemingly maintaining his connection to European society and Christian respectability and reinforcing perceived binaries of civilised and savage ().

Heroic Rescue

With their luminous golden atmosphere, Carmichael’s paintings convey a celebratory mood as the Islanders’ outstretched arms reach towards the Isabella, seemingly suggesting a communal willingness to return the child. In this sense the artist’s depictions differ from written accounts, which outline the Islanders’ reluctance and distress in parting with the child. There are only minor elements that nuance this narrative. In the 1839 painting, one Islander has his arm around another, seemingly comforting him and possibly referencing Duppa or Oby. In the 1841 work, a tiny figure on the distant Isabella lifts an iron axe—part of the exchange negotiations. The Rescue paintings evoke an image of benevolent power and triumph over peoples and territory, rather than conveying the deep grief and pain experienced by the boys and their adopted family and friends. Despite referring to the boys being ‘saved from Indian slavery’, the various texts paradoxically also remark on the kindness of Duppa and the Meriam people and acknowledge their shared sorrow. According to King’s government report, when William was finally brought to the beach ‘surrounded by the natives’, he was held in the arms of a young man ‘who seemed by his kissing him to be very sorrowful at the idea of giving him up’. William ‘seemed frightened […] and did not like parting with his old black friends’. Conveyed to the ship by an anguished Oby, the tearful child clung to his protector’s neck and pointed back to shore.Footnote53 However, in both paintings William is held away from his carer’s raised arms and instead of pointing sorrowfully to shore, the child directs his outstretched arm towards the ship, a symbol of British imperial power and the conduit for his return to civilisation ().

Figure 4. J. W. Carmichael, The Rescue of William D’Oyly (1841). Image detail. National Gallery of Australia. Photo: Wiki commons.

The term ‘rescue’ in the titles implies the notion of captivity, yet Ireland informed Captain Lewis that on Mer he and William experienced ‘great […] and even parental kindness’, and that he was indebted to Duppa ‘for his life and protection’.Footnote54 The rescue mission brought conflicting emotions for the boys; although Ireland indicated ‘a desire to leave’ his island life, Brockett describes the youth as expressing ‘mingled emotions of fear and delight’ once aboard the Isabella.Footnote55 Meanwhile, on reaching the ship William was given clothes to wear and, according to Ireland, he ‘looked very curious’ and ‘they made him feel uncomfortable’. The Meriam people expressed great sadness regarding the loss of Waki and Uass, and Duppa and Oby were deeply distraught. Oby sobbed when William was finally brought to the ship, and Ireland relates that Duppa ‘cried, hugged me, and then cried again; at last he told me to come back soon’.Footnote56 Despite this testimony, Carmichael focuses on a heroic narrative of reclamation, obscuring the intense grief and sadness experienced by the boys and their adopted family at their permanent separation.

Ways of Seeing

Carmichael’s rendering of the Rescue paintings was shaped by particular ways of seeing, consciously or unknowingly encompassing personal and cultural perspectives. The paintings represent two examples of a wider body of colonial and, more specifically, maritime and castaway imagery that envisioned cross-cultural encounters from a Eurocentric worldview. As discussed earlier, castaway tales such as Eliza Fraser’s experiences were often presented as captivity narratives, reinforcing oppositional constructs of ‘civilised’ and ‘savage’ that subsequently supported arguments for violence and subjugation.Footnote57 While Fraser’s story has been extensively re-examined in multiple formats, with interpretations of the encounter shifting over time and from different perspectives, the case of the Charles Eaton castaways and the related Carmichael paintings, one of which is held by the National Gallery of Australia, have received less critical attention.Footnote58 And while First Nations artists and writers such as Fiona Foley and Larissa Behrendt have employed creative practice to speak back to the Fraser testimony, it would be valuable to consider Carmichael’s paintings in the context of contemporary responses by Torres Strait Islander artists. In their imaginative animated documentary K’gari, Foley and Behrendt employ interactive elements, asking viewer/participants to ‘help erase the myth that influenced history’ by clicking a mouse to shatter and erase the on-screen text derived from Fraser’s sensationalised account. A Butchulla perspective of the events is provided to counter Fraser’s falsities and misunderstandings, and the documentary calls for Fraser Island to be returned to its Butchulla name of K’gari.Footnote59 Although Ireland’s account of the Charles Eaton incident is less sensationalised than Fraser’s, records of this historical episode have primarily been mediated by European/White Australian worldviews, so there is a need for Torres Strait Islander perspectives of these events to be more widely known and understood.

In retelling aspects of the Charles Eaton saga, Carmichael does not focus on violence as was often the case in other Australian castaway tales. Nevertheless, in romanticising the scene with its luminous atmosphere, and by foregrounding the government ship and its heroic rescue mission, he normalises and affirms the British sense of moral certitude in its maritime and imperial power. In these dramatic scenes, the artist depicts the actors as working collectively to facilitate the return of the boys. By presenting the Islanders as enthusiastically participating in the return of William, he seemingly denies their agency in the events, revealing assumptions of the rightness of recovery from a state of perceived captivity rather than care.

The downplaying of the humanity of this encounter, with its shared emotions of grief, compassion, and parental devotion, implies the kind of not knowing or denial of ‘other’ that Kaplan addresses in her examination of the imperial gaze.Footnote60 While visual signifiers of difference such as whiteness and clothing enable the castaways to stand out within the images, they also emphasise distinctions between civilised and savage, and deny the boys’ acculturation within Meriam society—a situation that would unsettle those oppositional constructs and fixed notions of the ‘other’. In ways such as this, Carmichael’s paintings consciously or unconsciously frame their narratives in very specific ways, reinforcing colonial perceptions of First Nations Australians and denying the shared humanity of this complex and moving encounter.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank curatorial staff at the Silentworld Foundation, the National Gallery of Australia, and the National Library of Australia for access and assistance in supporting research undertaken for this paper. The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lisa Chandler

Lisa Chandler is Adjunct Associate Professor in Art and Design at the University of the Sunshine Coast (USC). She was foundation director of the USC Gallery and has curated numerous exhibitions including co-curating the award-winning touring exhibition East Coast Encounter: re-imagining 1770. She has published widely on art, curatorship and visual culture and was the recipient of the inaugural curatorial research fellowship at the National Library of Australia. Lisa was leader of USC’s first arts and humanities research group and Deputy Head of the School of Creative Industries. She is a Senior Fellow, Higher Education Academy and has received multiple university and national teaching awards.

Notes

1 Various spellings of ‘D’Oyly’ exist in accounts, with the most common variant being D’Oyley. For consistency with the painting titles, ‘D’Oyly’ will be used here. John Ireland is also referred to as Jack in some texts. The boys’ ages are from Veronica Peek, ‘Charles Eaton: Wake for the Melancholy Shipwreck’, https://veronicapeek.com/. In her regularly updated site, Peek provides extensive scholarship examining many facets of this event.

2 Accounts include William Edward Brockett, Narrative of a Voyage from Sydney to Torres’ Straits: In Search of the Survivors of the Charles Eaton, in His Majesty’s Colonial Schooner Isabella, C.M. Lewis, Commander (Sydney: Henry Bull, 1836); Phillip Parker King, A Voyage to Torres Strait in Search of the Survivors of the Ship Charles Eaton… (Sydney: William Evans, 1837); Thomas Wemyss, Narrative of the Melancholy Shipwreck of the Ship Charles Eaton: and the Inhuman Massacre of the Passengers and Crew: With an Account of the Rescue of Two Boys from the Hands of the Savages in an Island in Torres Straits (Stockton: W. Robinson, 1837); ‘Police’, Times, 31 August 1837, 6; and John Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans: a True Narrative of the Shipwreck and Sufferings of John Ireland and William Doyley, Who Were Wrecked in the Ship Charles Eaton, on an Island in the South Seas (New Haven: S. Babcock, 1845 edition).

3 Bernard Smith, European Vision and the South Pacific 1768–1850 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960).

4 Ian Donaldson and Tamsin Donaldson, eds., Seeing the First Australians (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1985), 15.

5 Examples of scholarship addressing art and visual culture in colonial Australia include Nicholas Thomas, Possessions: Indigenous Art/Colonial Culture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999); Jane Lydon, ed., Calling the Shots: Aboriginal Photographies (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2014); John Maynard, True Light and Shade: An Aboriginal Perspective of Joseph Lycett’s Art (Canberra: National Library of Australia Publishing, 2014); and Tim Bonyhady and Greg Lehman, The National Picture: The Art of Tasmania’s Black War (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2018).

6 Carl Thompson, ed., Romantic-Era Shipwrecks (Nottingham: Trent Editions, 2007), 4.

7 See, for example, Eliza Fraser, Narrative of the Capture, Sufferings, and Miraculous Escape of Mrs Eliza Fraser (New York: Charles S. Webb, 1837).

8 John Curtis, Shipwreck of the Stirling Castle (London: George Virtue, 1838). For further discussion of Curtis’s shaping of the narratives see Lynette Russell, ‘“Mere Trifles and Faint Representations”: the Representations of Savage Life Offered by Eliza Fraser’, in Constructions of Colonialism: Perspectives on Eliza Fraser’s Shipwreck, ed. Ian J. Niven, Lynette Russell and Kay Schaffer (London: Leicester University Press, 1998), 51–62; Iain McCalman, The Reef: A Passionate History (Melbourne: Penguin Books, 2013); and Larissa Behrendt, Finding Eliza: Power and Colonial Storytelling (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2016).

9 Martin Nakata, Disciplining the Savages, Savaging the Disciplines (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2007), 11.

10 Ibid., 7, 18–19, 123.

11 Ibid., 11.

12 Margarette Lincoln, ‘Shipwreck Narratives of the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century: Indicators of Culture and Identity’, British Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 20 (1997): 155–172; Thompson, ed., Romantic-Era Shipwrecks, 4.

13 Lincoln, ‘Shipwreck Narratives of the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century’, 155.

14 See, for example, discussion of the Eliza Fraser saga in Russell, ‘“Mere Trifles and Faint Representations”’ and Behrendt, Finding Eliza.

15 Lincoln, ‘Shipwreck Narratives of the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century’, 165.

16 Lincoln, ‘Shipwreck Narratives of the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century’; Thompson, Romantic-Era Shipwrecks.

17 Thompson, Romantic-Era Shipwrecks, 6.

18 Geoffrey Quilley, Empire to Nation: Art, History, and the Visualization of Maritime Britain, 1768–1829 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011).

19 For an overview of multiple instances of castaway encounters with Indigenous Australians see John Maynard and Victoria Haskins, Living with the Locals: Early Europeans’ Experience of Indigenous Life (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2016).

20 Anna Johnston and Alan Lawson, ‘Settler Colonies’, in A Companion to Postcolonial Studies, ed. Henry Schwarz and Ray Sangeeta (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000), 360–376; Lorenzo Veracini, Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

21 Allan McInnes, ‘The Wreck of the “Charles Eaton”’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland 11, no.4 (1981): 21–50.

22 The ship’s surgeon and two crew members were also aboard. It is possible that this group may have deserted the remaining crew. Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 14.

23 As indicated earlier in this essay, the term ‘cannibalism’ has become a loaded one. The Islanders ate pieces from the heads and the eyes. Ireland later learned that this was customary practice used to instil courage against enemies. Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans.

24 Wemyss, Narrative of the Melancholy Shipwreck; Peek, ‘Charles Eaton’; Maynard and Haskins, Living with the Locals. Much later, Ireland learned that Meriam people had been killed by Europeans. Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 42, 48.

25 Ireland later received word that Sexton and George did not survive. They had likely died from malnutrition or as a result of inter-tribal warfare. Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 55–6; Peek, ‘Charles Eaton’.

26 Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 35–36.

27 Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 36.

28 Six of the crew initially deserted the Charles Eaton by stealing the only remaining lifeboat and reached Timor Laut and eventually Batavia, where they passed on news of the wreck.

29 King, A Voyage to Torres Strait, 2–3; Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 56.

30 King, A Voyage to Torres Strait, 15, 18.

31 Anon., ‘The Ship “Charles Eaton”’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, letter to the editor, 20 April 1839, 3. William was accompanied by Captain Lewis on the perilous voyage, which included a narrow escape from shipwreck.

32 For contemporaneous accounts of the Charles Eaton rescue see note 2.

33 This British rescue painting focused on the wreck of the Forfarshire off the Northumberland coast in 1838 and the subsequent rescue of nine crew by lighthouse keeper William Darling and his daughter Grace. Diana Villar, John Wilson Carmichael, 1799–1868 (Portsmouth: Carmichael and Sweet, 1995), 38–42.

34 Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their Work from its Foundation in 1769 to 1904 (London: Henry Graves and Co and George Bell and Sons, 1905); James Taylor, Marine Painting: Images of Sail, Sea and Shore (London: Studio Editions, 1995); Villar, John Wilson Carmichael; Andrew Greg ‘John Wilson Carmichael’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004. www.oxforddnb.com.

35 David Cordingly, Painters of the Sea (London: Lund Humphries, 1979), 11–13, 25; David Cordingly, Marine Painting in England, 1700–1900 (London: Studio Vista, 1974); Andrew Greg, John Wilson Carmichael 1799–1868: Painter of Life on Sea and Land (Tyne and Wear: Tyne and Wear Museums, 1999).

36 Jeffrey Auerbach, ‘The Picturesque and the Homogenisation of Empire’, The British Art Journal, 5, no.1 (2004): 47–54.

37 Royal Greenwich Museums, ‘“Erebus and “The Terror” in New Zealand, August 1841’, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-12705 (accessed 29 March 2023).

38 Anon., ‘Voyage of the Government Schooner “Isabella” in Search of the Survivors of the “Charles Eaton”’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 20 October 1836, 4; McInnes, ‘The Wreck of the “Charles Eaton”’, 35.

39 Villar, John Wilson Carmichael; Quilley, Empire to Nation.

40 Hordern House, ‘Carmichael, J. W. The Rescue of William D’Oyly, by the Isabella, from Murray Island, Torres Strait, 1836’, notes on the painting (Sydney: Hordern House, n.d.); The National Archives, ‘William Cochrane Carr Ltd’, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/19627276-8caa-479e-b503-19bb5a590c59 (accessed 29 March 2023).

41 Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, second ed. (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 94, 103.

42 Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, 1992), 201–204.

43 E. Ann Kaplan, Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film and the Imperial Gaze (New York & London: Routledge, 1997), xvi–xvii.

44 King, A Voyage to Torres Strait, ii.

45 In the appendix to Narrative of the Melancholy Shipwreck, 41, Wemyss proclaims that the case excited ‘the most fearful and extraordinary anxiety’. See also Anon., ‘Visit of the Child Whose Parents Were Murdered by the Savages at Torres Straits to the Lord Mayor’, Commercial Journal and Advertiser, 22 May 1839, 4.

46 King, A Voyage to Torres Strait, 2.

47 Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 39, 46–47.

48 Brockett, Narrative of a Voyage from Sydney to Torres’ Straits, 15; Anon., ‘The “Charles Eaton”’, Australian (Sydney), 28 April 1837, 2.

49 This also enables the viewer to locate John and William more readily within the panorama.

50 The 1839 version represents a departure from the written accounts, which indicate that Ireland was on the Isabella when William was eventually brought to the ship a day later.

51 See Rod Macneil, ‘“Our Fair Narrator” Down-under: Mrs Fraser’s Body and the Preservation of the Empire’, in Constructions of Colonialism: Perspectives on Eliza Fraser’s Shipwreck, ed. Ian J. Niven, Lynette Russell and Kay Schaffer (London: Leicester University Press, 1998), 63–76; and Philippa Levine, ‘States of Undress: Nakedness and the Colonial Imagination’, Victorian Studies 50, no. 2 (2008): 189–219.

52 Anon. ‘The “Charles Eaton”’, 2; Ireland relates that once on board the Isabella he was given a shirt, trousers and a straw hat. Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 47, 57.

53 King, A Voyage to Torres Strait, i, 19.

54 King, A Voyage to Torres Strait, 4.

55 Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 51; Brockett, Narrative of a Voyage from Sydney to Torres’ Straits, 13.

56 Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, 58, 61. Ireland and William were taken to Sydney and eventually returned to England.

57 Behrendt, Finding Eliza, 54.

58 For a discussion of contrasting creative interpretations of the Fraser encounter see Jude Adams, ‘Home Ground and Foreign Territory: The Works of Fiona Foley and Sidney Nolan’, in Constructions of Colonialism: Perspectives on Eliza Fraser’s Shipwreck, ed. Ian J. Niven, Lynette Russell and Kay Schaffer, Ian J. Niven, Lynette Russell and Kay Schaffer (London: Leicester University Press, 1998).

59 See K’gari: The Real Story of a True Fake, written by Fiona Foley and Larissa Behrendt, directed by Boris Etingof, Studio Breeder and SBS Online Documentary and SBS Digital Creative Labs, https://www.sbs.com.au/kgari/.

60 Kaplan, Looking for the Other, xvi–xvii.