For more than five years, I have been working with collaborator Victoria Pham on a project titled Re:Sounding. As artist-researchers, our work continues to bring together collaborators, organisations, and very different communities to reinvigorate, reclaim, and rematriate the sounds and musical culture of instruments held in museum and private collections.Footnote1 Our work began with the Đông Sơn drums, a group of Bronze Age instruments that were primarily excavated from the Red River Delta in the north of Vietnam during French occupation and collected from various tribes and cultures throughout Southeast Asia.

As the children of boat people, Victoria and I regularly heard stories about these mythical bronze drums. Instead of focusing on the traumas of the war, our families told us stories about fantastical instruments that carried the sound of thunder from the ancient times of the Đại Việt, ancestors to the Vietnamese Kinh majority three thousand years ago. These drums could summon thunderstorms and lightning, simultaneously bringing harvest rains and releasing wild torrents capable of washing away enemy invaders. Despite these stories, our parents had only ever seen archaeological and ethnographic photographs of Đông Sơn drums in old schoolbooks. In the aftermath of decolonial ruptures during the 1950s and 1960s, these drums had by then been largely looted or systematically ‘rescued’ for ethnographic and scientific study elsewhere. It was not until 2016, whilst visiting me during a funded travelling fellowship (from the Samstag Museum of Art and the University of South Australia) that my parents had their first encounter with a Đông Sơn drum. As tourists marking off the must dos of New York City, we happened on a small example of this mythical drum, displayed in the Florence and Herbert Irving Southeast Asian Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. My parents were unlikely to be motivated enough to visit similar museums back in Australia, but in this instance, visiting me during my arts research residency, they were willing to participate in popular high art and culture.

Spot lit and arranged alongside other Bronze Age artefacts, this Đông Sơn drum was silently displayed behind thick museum glass. Contradicting the mythical and percussive maelstrom that my parents had stoked in my childhood imagination, the devotional silence and curatorial muting of this instrument felt acutely lonely. Especially poignant for musical instruments, the silent display of different cultures and peoples inside dominant institutions of empire and conquest is an aesthetic norm in museums the world over. How ethnographic displays enact institutional frameworks of preservation, containment, and conservation is well described by Aboriginal and First Nations researchers including Yorta Yorta woman and curator Kimberley Moulton. Writing on the inappropriate taking, holding, and management of Aboriginal materials and ancestor remains in museums throughout the world, Moulton notes:

In the age of ‘enlightenment’ and the ‘discovery’ of Australia, anthropologists, early explorers, amateur collectors, and missionaries began taking, trading and buying objects and human remains, often in circumstances that were incredibly unethical. The UK has a significant collection of early Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island cultural material, including important pieces from the south-east of Australia. These items were collected both for their study and their aesthetic and whilst they are from our past they also represent our present. For some people, our identity and culture are inherently linked to these objects. They are a tangible connection to our ancestors and embody the cultural connection we have to our history and to our reality.Footnote2

Two decades ago, writing on the predicament of diversity and access at the Art Gallery of NSW in relation to their 2001 exhibition on Buddhist art, Ien Ang notes the inherent flaw of institutions dealing with the growing diversity of audiences under a contemporary managerial model of social inclusion: ‘When governments [the principle funding bodies of these institutions] talk about managing diversity, they generally refer to the need to somehow recognize and accommodate these differences within the conduct of public administration … Indeed, today’s museums are under intense pressure to prove their relevance for multicultural constituencies’.Footnote3 Yet these museums and their curatorial models continue to resort to a colonial methodology via the ‘institutionalization and dissemination of a single high culture, which would confirm the lowliness of the cultures of the outsiders—the working classes, immigrants, and so on’.Footnote4

Recently, Ang has written on how little has changed during the intervening two decades. Ang notes the persistent institutional ambivalence towards addressing societal changes that still uphold continuing marginalisation:

To be included does not mean becoming an integral part of the mainstream; it means to be content with hovering on the periphery of the mainstream. In other words, the vision of inclusion is limited because it does not undermine the hegemony of the dominant culture; instead, it shores it up by containing diversity within its allocated box.Footnote5

To groups unfamiliar with these museum spaces, the academic distinctions between, say, the Art Gallery of NSW and the Australian Museum remains functionally unclear. Externally, these institutions are fronted by sandstone façades replicating the orders of Classical Greek antiquity.Footnote7 These collecting institutions are also continuously and conspicuously expanding, building equally monumental additions in glass and steel. The functional differences between the academic, pedagogic, and social endeavours of a natural history museum (like the Australian Museum) in comparison to a public art museum (like the Art Gallery of NSW) are lost on communities whose cultural objects end up on display in both types of institutions. These collecting institutions have inherited significant holdings of our art objects, materials, artefacts, and instruments throughout periods of colonial conquest. Both institutions continue to curatorially and pedagogically segregate non-Western materials from mainstream narratives. And as our cultural materials continue to oscillate somewhere between the ethnographic, anthropological, and prehistoric, our cultures are themselves predominantly presented as not contemporary.

Distinguishing between the traditional roles of art, natural history, and ethnographic museums is irrelevant when it comes to non-Western, non-Anglo Celtic inheritance, where the coloniality of the architectural and curatorial vision has remained largely unchanged beyond the rhetoric of inclusion. Even when acting as public repositories for the most significant and sacred artefacts of our cultural heritage, such as the Đông Sơn drum, the barriers of museums in Australia and abroad still excludes people like my parents and myself. To diasporic people resettled here, the distance from our home culture is not only geographical but one continuously exacerbated by ongoing institutional ambivalence, exclusion, and separation of cultural materials from their communities.

Repatriation

The consequences of scholarly conquest and colonial extraction by French archeaologists, ethnographers, and scientists throughout the 1930s, and then the illicit trade of antiquities and cultural materials throughout the regional conflicts between the 1940s and 1980s in Southeast Asia, has led to a significant number of Đông Sơn bronze drums in collections and institutions outside of Vietnam. Unsurprisingly, Paris accounts for many examples held at the Musée national des arts asiatiques–Guimet, the Musée du quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, and the Musée Cernuschi. Other examples are in Europe, North America, and Australia. The provenance of these bronze drums is generally traceable to the 1950s, coinciding with the French Decolonial Wars, and the 1970s during the Vietnam-American War.Footnote8 The Australian Museum and the Art Gallery of NSW together have three large examples of Asian bronze drums with a similar provenance; entering their collections as donations and gifts throughout periods of regional conflict and disruption.

It seems that as my family, along with hundreds and thousands of Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Southeast Asian refugees were being displaced internally and internationally, there was a concurrent and parralel flow of our cultural artefacts and materials into the major collecting institutions of the West. Dispersed from their homelands, these materials had inadvertently accompanied us, ending up in extraordinarily close proximity to the places where we were resettled. Whilst my family was engaging with people smugglers, art dealers and antiques traders were simultaneously engaging with looters to traffic cultural objects out of these regional conflict zones. It is important to note how institutional protections afforded to smuggled antiquities was, by contrast, absent at a policy level in regard to offshore detention centres and the treatment of refugees seeking asylum in Australia. The distinct violence and lack of protections afforded for human cargo reflects a persistent political unwillingness to challenge the hegemony of a dominant culture that continuously distinguishes and absolves itself from the recent post-colonial upheavals of the region.

Australian museums, like so many institutions, are now scrambling to reassess and review dubious paper trails left by former directors, affiliated art dealers, auction houses, arts donors, researchers, and publications to verify the provenance of their collections. This follows the many decades of work done by First Nations activists and leaders who have managed to turn the tide in repatriating ancestor remains and sacred objects back to their traditional owners, and the frequency of public scandals flowing from the release of incriminating files such as the Pandora papers, linking museum boards and donors to convicted art dealers and traffickers such as Subhash Kapoor and the now deceased collector and antiquities expert Douglas Rochford, the details of which are all now in the public domain.Footnote9 These developments are forcing major collecting museums to pay closer attention to accusations concerning the theft of cultural materials and their acquisitions policies. Calls for repatriation and restitution are increasingly integral to the basic social contract of higher research, and the wider expectation for museums and public institutions to not cause harm or cultural trauma for their diverse staff, audiences, and patrons.

It could be argued that the momentum towards this global demand for the repatriation of objects was only possible because of advocacy by Aboriginal activists in Australia during the 1970s. Paul Turnbull notes that the call to return Aboriginal ancestor remains was documented by British colonists as far back as 1892.Footnote10 However, it took the persistent effort and campaigning of communities right up to 1976 to achieve the first return of ancestor remains and the burial of Truganini from the Tasmanian Museum by the Nuenonne people. This watershed moment

proved to be the beginning of long and determined campaigning by Indigenous Australians which has seen the gradual repatriation of ancestral bodily remains from Australian and overseas scientific collections. Since the mid 1970s, the remains of around 5000 people held in Australian museum and medical school collections have been the focus of repatriation negotiations.Footnote11

The Glass Cabinet

Kept silent behind museum glass, or out of sight in the storage facilities of museums and private collections, the Đông Sơn drum to Victoria and me represents the ongoing cultural isolation and social containment still felt by many Vietnamese refugees and migrants resettled into numerous colonial-settler contexts in the West. As artists from non-Anglo-Celtic or non-English-speaking backgrounds, Victoria and I find ourselves regularly curated into group shows and paraded in Australian exhibitions and art events to represent our ‘diverse communities.’Footnote13 Temporarily curated and transplanted into predominantly white spaces, our cultural difference is made present and visible for the aesthetics of diversity that actually continues to privilege Western organisations and their funding bodies.

Every now and then, pulled out of the suburbs, we are tasked with retelling refugee stories and fulfilling testimonials of colonial trauma—so long as it serves what Aruna D’Souza describes as a grand narrative of contemporary colonial-settler transformation. To D’Souza, this parasitic version of curatorial containment explicitly repurposes the visibility of racialised bodies to ensure institutional relevance in late-capitalist diversity and culturally inclusive funding policies.Footnote14 Both inside and outside the museum, our bodies are marked as different by racial discourses and a politic that somehow always puts us on display (and keeps us under surveillance) within the colonial-settler context. This inescapable self-consciousness, and the sensation and phenomenology of existing with racialised difference has been described by Sara Ahmed.Footnote15 The spectacle of being on display, accompanied by our short artists bios and artist statements concerning our cultural output, is not far from the wall labels and didactics of ethnographic objects inside a display cabinet. Akin to the ethnographic object, we, as ethnic subjects, are also on display.

Stéphanie Cassilde notes the chilling impact of how non-Anglo Australians are regularly asked ‘Where are you from? … followed up with, but where are you really from?’Footnote16 Deployed as an act of innocuous Anglo-curiosity, this benign statement follows a line of inquisition that ultimately forces racialised subjects into public scrutiny. If you appease the interrogator by clarifying your difference, stating your cultural and ethnic background, then you prove to them that you are indeed different and not of this place; you know your role as a compliant subject. If you refuse this line of casual grilling, you ultimately confirm suspicions about your difference because you lack a sense of humour, are overreactive, unreasonable, and socially deviant. Cultural and racial difference is for some people always on display. It is unconsciously policed or consciously deployed by majoritarian citizens who feel their unequivocal birth right within the settler colony. Foundational to this colonial hierarchy is what Catriona Ross calls ‘the historical and cultural unconsciousness of an anxious settler nation’, a nation still carrying the fear that having colonised this place, the children of those colonisers are themselves under threat of being colonised by racial others.Footnote17 The profound existential anxiety of the settler nation is perhaps best encapsulated in the poetry and rhetoric of recent trans-Pacific border and identity politics.

The Rose Garden

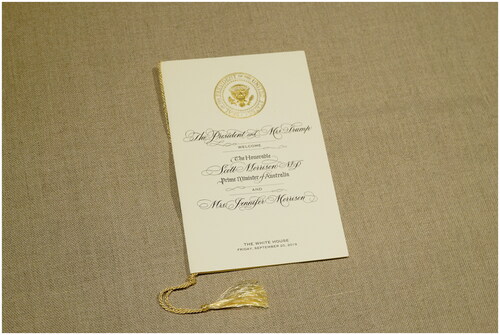

On 20 September 2019, the then President the United States, Donald Trump, along with his wife Melania, held a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden to welcome the then Honourable Scott Morrison MP (Prime Minister of Australia) and Mrs Jennifer Morrison. With two heads of state whose policy slogans were to ‘Make America Great Again’(Trump) and ‘How good is Australia! How good are Australians!’ (Morrison),Footnote18 the blatantly racist and nationalistic border policies espoused by these trans-Pacific partners were summarised by the Presidential dinner address:

Our two countries were born out of a vast wilderness … From the wide-open landscapes of the West and the Outback rose up cowboys and sheriffs, rebels and renegades, miners and mountaineers. Against incredible hardships, our people have produced abundant harvests, pushed the bounds of science and exploration, and created timeless masterpieces of art, music, and culture. The defiant spirit of our people has also armed our nations with the strength to overcome any foe that dares to trample on our sovereignty, threaten our citizens, or challenge our freedom.

… In June of 1940, during the Second World War, a renowned Australian writer published a song in the Australian Women’s Weekly. The song rallied the entire nation, and it remains an inspiration to patriots everywhere…

As many of our friends with us here tonight know well, the acclaimed Australian author who penned these beautiful lines was Dame Mary Gilmore, and her great-great-nephew is Prime Minister Morrison. (Applause.)Footnote19

The most revealing part of Trump’s address is a renewed pronouncement of border defence and violence: ‘The defiant spirit of our people has also armed our nations with the strength to overcome any foe that dares to trample on our sovereignty.’ A spirit that ignores Indigenous Sovereignty and clings to the nationalism of the White Australia of Scott Morrison’s great aunt, Dame Mary Gilmore.

The Nguyen Collection Of Anglo-Australian Arts

shows the invitation to the Rose Garden ceremony at the White House. Purchased from eBay in 2022, the document is part of the Nguyễn Collection of Anglo-Australian Arts (NCoAAA). Evolving as a series of minor responses to the illicit trade, theft, and collection of ethnographic and cultural materials by colonial museums and collectors, the NCoAAA inverts the power dynamic of Western object collection.Footnote20 Privately and quietly purchasing the small miscellanies of convict history, Australian Federation, the White Australia Policy, and the contemporary border policies of recent decades, the NCoAAA conceptually inverts expectations of who collects. This intervention proposes how immigrants and refugees without the social and nationalist birth-right to ‘sit on our stockyard rail’ and inherit the ‘harvests’ of white colonists and pioneers can simply purchase and own the cultural heritage of our host country. A form of small but cumulative cultural expropriation, this act of collection mischief is intended to disrupt the ethnographic and curatorial order.

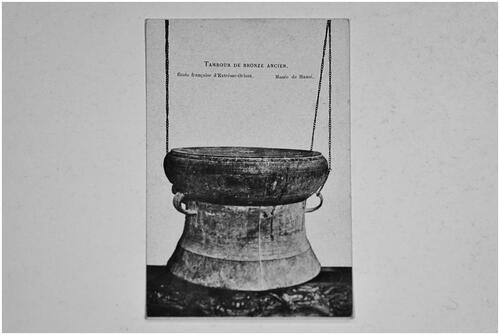

Figure 1. Postcard donated by Phuong Ngo to Re:Sounding Tambour De Bronze Ancien (1933). French Indochinese postcard. (Photograph of donated postcard, courtesy James Nguyen and Victoria Pham).

Figure 2. Official invitation, The President and Mrs Trump Welcome the Honourable Scott Morrison MP Prime Minister of Australia and Mrs Jennifer Morrison, The White House, 20 September 2019. Courtesy the Nguyen Collection of Anglo-Australian Arts. (Image courtesy James Nguyen).

Figure 3. Art Gallery of NSW storage facility, visiting the collection of two large Frog Drums, 2018. The artists were invited to photograph and document the encounter, but not touch or handle the drums. (Photographic documentation of site visit is courtesy of Sheila Pham).

Figure 4. Audience inspection of a Đông Sơn drum. Footscray Community Arts Centre, 2021. (Photographic documentation of community performance courtesy of James Nguyen and Victoria Pham).

As a conceptual extension of Michel Foucault’s discourse on incarceration and containment into Edward Said’s concept of Orientalism, the Nguyễn Collection purchases, takes hostage of, and sarcastically fetishes the Antipodean-Occident.Footnote21 In the hands of a non-Anglo Australian collector, the curiosities and materials of Anglo-Australia could be re-curated and deployed to counter recurrent and ongoing forms of nationalistic fervour, white supremacy, and settler-colonial denial. This poses the question of who ultimately has the right to participate in, and to collect, culture. When White Australian heritage becomes the ethnographic subject, and subjected to collection by non-Anglo others, then perhaps Anglo-Australia might feel what it means to have their cultural heritage separated, striped away, and ultimately kept out of reach.

Buy Back Schemes

In an attempt to gain access to the collection of Đông Sơn bronze drums at the Art Gallery of NSW, Victoria and I started approaching curators, musicians, and other artistic collaborators to find out how these drums could be sounded and heard again. Proposing the concept of ‘sound repatriating’ as a way to work with diasporic communities across Australia, Vietnam, and Southeast Asia, as opposed to the conventional ‘object repatriation’ to a source community, Victoria and I wanted to gain institutional approval to record a small sample of drum sounds from these instruments held in museum collections, which could then be shared with diaspora communities.

After participating in a series of meetings, we were finally granted access, and given supervised viewings of instruments in the storage facilities of the Art Gallery of NSW, and also later at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, at the University of Cambridge. Despite this, after five years of negotiations Victoria and I are yet to receive the approval to touch the surface or record any sound from these drums. Reminiscent of Foucault’s writing on incarceration, we were granted visitation rights to these instruments, but could never be permitted to physical touch or play our cultural instruments.

Had we solely defaulted to the institutional gatekeeping of various museum boards and executive committees, we may well have resigned the Đông Sơn drum to perpetual silence. Considering the bureaucratic and administrative materiality of engaging with these museums, our project could have existed as a high art, high concept, academic, and speculative exercise. The coolness of this type of institutional acquiescence simply felt wrong. Victoria and I eventually decided that for this work to be more than an academic exercise, we had to record the noise and sound of the Đông Sơn drum. The work of accessing long forgotten or dormant cultural sounds must somehow transcend institutional critique and maintain ongoing connections with our Vietnamese community. To us, cultural reclamation demanded a break from the detached and liminal speculations of artworld ‘contact zones’ as described by James Clifford.Footnote22 We wanted physical access—actual contact with our instruments. We wanted a percussive, visceral, and haptic engagement to embody the cultural practices denied to us. After all, these drums are instruments, and as instruments they are intended to be sounded and played.

As noted by Robin Boast, when dealing with museum conservation policy, it is ultimately ‘the institution that controls the calibration and use’ of the collections they own.Footnote23 It is the structural impulse of these institutions to deploy a kind of silence to manage away what they cannot control—that is, the noisy human networks and social imperatives seeking to presence physical contact and visceral action in these spaces. The Nguyễn Collection of Anglo-Australian Arts was one way to exert a kind of cultural retribution against the defence of Anglo-colonial birthright and access. In thinking through the institutional enterprise that constitutes the vast collections of major museums, Boast notes that even when these museums allow access, it is inevitably according to the museums’ terms: ‘The act of museums allowing source community voices simply continues to silence the stories of violence and degradation that were the colonial past.’Footnote24

Ultimately, it was the various conservation policies, insurance concerns, and administrative objectives imposed at board level that prevented us as artist-researchers—and our diasporic communities, cultural collaborators, other Vietnamese musicologists, contemporary composers, musicians, and producers who were all wanting to hear these instruments—from achieving our objective. Despite our work to gain the trust and support of museum staff, especially the academic openness of curators and conservationists working in the Department of Asian Art at the Art Gallery of NSW, we were hindered by endless administrative obfuscations that ensured these instruments stayed untouched, unplayed, and ultimately, unsounded.

This prompted members of my family and I to seek alternative options to access these instruments. By pursuing the basic strategy of buying up cultural materials, as I had with the NCoAAA, my extended family started to pool money together with the goal of acquiring one of these drums on the open market. Trawling through online auction sites, including Invaluable.com and Drouot.com, we started subscribing to auctions and setting up search notifications from local private estate sales. Within just a few months, we tracked a number of Đông Sơn drums being exchanged by collectors in Australia, North America, Japan, Germany, and France. With the collective contributions of our families, Victoria and I eventually managed to acquire two examples of these fabled Đông Sơn drums at auction.

There is a shocking perversity in how the museum failed to facilitate workable access to their collections, leaving little option for Victoria and me beyond the concerted and collective effort of our less well-resourced families. The lack of access to institutional collections meant that the financial burden and time-consuming process of scouring auctions for our own cultural instruments was fundamentally placed onto a group of artists and their families. Perhaps it is the privatisation of cultural access, of deferring all risk onto those already institutionally excluded, that again breaks the trust of communities and our desire to engage with ambivalent institutions that hold our cultural inheritance.

For the Vietnamese diaspora in Australia, there is no government agency or cultural safety net beyond our own diasporic and family networks in which to counter the administrative indifference of these public institutions. As artists and people from diasporic communities, it comes down to paying for access, and participating with our own culture on our own terms. Because we now collectively own these instruments, we gain a level of autonomy. By adopting the economic route to find gainful access, Victoria and I and our families inevitably call into question the role and ethics of the contemporary museum. When institutions are patently unable to fulfil the duty of care and facilitate supported and meaningful contact with their dubiously acquired objects, then who are these publicly funded institutions ultimately serving? More importantly, if these institutions are unable to match the level of community engagement that a pair of artists can organise amongst their untrained and art-hesitant families and friends, then are these institutions demonstrating value for money? It might be more economical to allocate funding to facilitate communities to directly buy back their own cultural materials, rather than making them constantly seek approval and permission to work within the cumbersome infrastructures of institutional constraint and disappointment.

Once we paid for the drums and started to share our performances online and at live performances, we were approached by multiple institutional partners to present our project at various public events with ‘public engagement’ opportunities. This will be discussed in depth a little later on, but ironically, all these museums proposed that their collection of institutional Đông Sơn drums could be taken out from storage and redisplayed, so long as own drums and digital recordings were made accessible to the public. Once again, these institutions were keen on engagement only if the material and economic risks, and the implications of public liability were ultimately absorbed by us and our diasporic communities.

Noting the rhetorical spectacle of these public events, museums remain culturally impenetrable, according to Sara Ahmed.Footnote25 The moment that there is a request to actually have collections opened up to scrutiny or be utilised in a way that even slightly challenges traditional paternalistic approaches to conservation, these museums resort to bureaucratic deferrals. Candice Hopkins’ contribution as a panellist at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 2018 is particularly insightful. As a Carcross-Tagish woman and contemporary art curator, Hopkins noted,

I don’t want us to all have the same assumed definition of what an institution is or will be … we need to shape these spaces in the way we want to see them shaped … as opposed to thinking that we are always having to react or subvert them, because we can do something else.Footnote26

Insiders and Outsiders

Of the two Đông Sơn drum examples that we currently have in our possession, the first can be traced back to Indonesia, having been purchased there in the 1980s by a Sydney collector. The other is a much older, more fragile example that we acquired from an auction house in Paris. This second example is described as being excavated in in the 1950s from Thanh Hóa, my father’s hometown in Northern Vietnam. Both these instruments carry profoundly different provenance stories of displacement.

Bringing together a team of professional percussionists, sound engineers, musicians, composers, and musicologists from Australia, Vietnam, and other parts of Southeast Asia, we eventually managed to navigate the border restrictions across recurrent pandemic lockdowns to finally play and share these instruments. We have developed and presented a digital archive of sound recordings we collected from our drums. To date, Victoria and I have shared over fifty open access sound samples, and have commissioned a series of compositions and performances with bands and musicians based in Vietnam, Indonesia, and Australia with funding from the Australian Council for the Arts, Arts NSW, Arrow Collective, and BLEED, a festival project by Campbeltown Arts Centre and Arts House Melbourne. Alongside a number of arts organisations willing to support our shareable and digital sound database, we are challenging conventional assumption about cultural authenticty and reclamation. As technological marvels of the Bronze Age, the Đông Sơn drum was created, traded, practiced, and continuously reinvented throughout its three thousand years of existence. Embedded into countless cultural practices beyond northern Vietnam, Southern China, Myanmar, and across Oceanic Southeast Asia from Indonesia to Papua, these drums were commodities and socio-political tools of trade, technology, and communication. Like the cultural innovations of these ancestral instruments, our collaborations with contemporary musicians and performers throughout Vietnam, Southeast Asia, and Australia continue to follow the sonic diversity of instruments that have always crossed tribal boundaries and musical traditions.

Now existing as a suite of downloadable and shareable database of stems and two live-streamed and archived online performances, our proposal for cultural maintenance and practice is one that is intrinsically rooted in the technological present.Footnote27 Unlike ethnographic representations that consign our culture to an extinct, distant and silent past, the digital capacity to destabilise, reconnect, and collectivise a digital and open-source sound archive has the ability to subvert the colonial and nationalistic imperatives of institutional ownership and preservation.Footnote28

Our drums and sound archives are beginning to accumulate a sonic life and repertoire that coexists and expands inside, outside, and alongside an array of institutions, museums and organisations, ranging from Fairfield Arts Centre, Footscray Community Arts Centre, the Sydney Opera House, the Australian War Memorial, and the Australian-Vietnamese Community in Australia, the Samstag Museum of Art in Adelaide, and BLEED (Biennial Live Event in the Everyday Digital), an inter-institutional online festival of sound and art with audiences in Vietnam, Indonesia, Australia, North America, and Europe. Working with and across these various institutions, as well as sharing our instruments with members of our families, friends, and communities of musicians and sound artists, we have opened up conversations and approaches far beyond the museum display case. Even though we rely on established institutional models to connect and find audiences for this work, we still value most the human networks and introductions that these opportunities have consolidated for Re:Sounding.

Rematriation

The impact of these collaborations has meant that one of our collaborators, Rắn Cạp Đuôi, a punk band from Sàigòn, Vietnam, has been able to leverage their involvement with both us and BLEED and gain British Council funding to record and tour new music in Europe. We also shared many exchanges and conversations with composers, especially Bagus Mazasupa (based in Jogjakarta, Indonesia), who informed us that throughout the Bronze Age, the Đông Sơn drum was widely traded and fastidiously collected by Indonesian tribes, who called these drums Gong Nakara. Overtime, collections of bronze Gong Nakara created a rich tonal resource, compelling local musicians to develop and invent a new artform called gamelan. A unique national musical tradition of Indonesia, gamelan was only possible as part of the Austronesian Bronze Age technologies, trade, and artistic contribution. Facilitated by ancient collections of Đông Sơn drums from their Vietnamese counterparts, Indonesian chiefs and musicians used these drums to invent and cultivate an entirely new musical tradition. If Đông Sơn drums had been collected and horded in Indonesia according to contemporary models of silent conservation and preservation, then the culturally distinct evolution of gamelan would never have materialised.

This is where the First Nations concept of rematriation comes into play. The argument for the repatriation of institutionally held collections of Đông Sơn drums back to Vietnam, from one colonial institution in Australia to a state-of-the-art national museum in Vietnam, is becoming more and more persuasive. However, this does not ensure that the dynamic sonic potential, transnational custodianship, and interwoven cultural ties, practices, and networks associated with these ancient instruments will be automatically assured. Although principally used to describe maintaining a connection to Ancestral Lands and ceremonies that strengthen and support the multigenerational restoration of care for country and care for community, Shawnee-Lenape Law Maker Steven Newcombe, describes rematriation as a concept that ‘acknowledges that our ancestors lived in spiritual relationship with our lands for thousands of years, and that we have a sacred duty to maintain that relationship’ through cultural practices for the benefit of future generations.Footnote29 Antithetical to this holistic approach to reclaiming cultural practice and connection, contemporary drivers for modern archaeology and repatriating objects back to the Global South are regularly deployed as economic levers to pacify potential economic trade-partners,Footnote30 and to facilitate the instrumentalisation of these objects for nationalistic and nation-building projects.Footnote31 Such global negotiations often neglect the ongoing ceremonial practices of First Nations tribes throughout Asia (including the Karen in Myanmar and the Muong in the highlands of Vietnam) beyond the museum context.

Can these trade deals and repatriation exchanges ensure that traditional instruments continue to have a place in our contemporary digital and cultural life? Like our ancestors, these instruments still hold the inventive and cross-border reverberations of our contemporary imagination. The resounding of the Đông Sơn drums that we purchased continue to help us reconnect with important knowledge about the dynamic and inventive contemporaneity of these instruments’ ancient sounds.

Australian War Memorial

After Victoria and I presented Re:Sounding at BLEED in 2020, we received a request to lend one of the Đông Sơn drums for a performance at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The email came from the director and composer of The Vietnam Requiem. The project was part of a series of new compositions dedicated to the recent wars that Australians had participated in. As we had expected, this project was commissioned to bring multiple refugee and migrant communities into the War Memorial. Victoria and I had obvious reservations, thinking about Sara Ahmed’s description of being included in these institutional structures only to satisfy the interests of these institutions.Footnote32 Here, the tokenistic inclusion of a war instrument—the Đông Sơn drum—which belonged to communities displaced by wars that Australians had participated in, felt immediately dubious.

However, after much discussion, Victoria and I realised that in a way, the two drums in our collection had become a community resource. In organising our work around these drums, we were perhaps an accidental museum. It would be hypocritical if we functioned like the museums we could not access. We ultimately decided to meet up with the project lead for the Vietnam Requiem, leaving the prospect of sharing our instruments open so long as we were satisfied that it would benefit the Vietnamese community in Australia. Over numerous meetings we very quickly realised that this project had attracted much more interest from the senior members and elders of the Vietnamese Community—people who we ourselves had particular trouble reaching out to. Many of the Vietnamese community involved, like my family, were Bác 54 and affiliated with the South Vietnam military—that is, with a particular political perspective that was essentially anti-Communist, pro-nationalistic (for Australia and South Vietnam), and prioritised conservative values. The recognition that the Vietnam Requiem offered to this part of the Vietnamese-Australian diaspora was one of pride and validation.

The research and common cultural background that Victoria and I shared with this part of the Vietnamese community could never offer to these elders the level of cultural and social validation of the Requiem. Swallowing our pride, we decided to support the project because we knew that parts of our own community would inevitably respect and admire a renowned Anglo-Australian composer over the work of emerging artists from their own community.

By taking part in The Vietnam Requiem, we were introduced to a whole generation of musicians and composers from the Vietnamese diaspora in Australia that we would never have otherwise been able to connect with. Through this project, Victoria and I were introduced to dissident musician Phan Van Hung. Hung talked to us about cultural reclamation and how the Vietnamese folk music that many musicians were trying to reclaim is now completely written and taught with Western notation. To Hung, even the process of reclaiming our music and songs was inevitably contained within a Western framework of musical notation and literacy. What we think we hear as folk was in fact a hybrid reduction ultimately tailored to suit the Western ear, its tastes, and sonic conventions.

Dylan Robinson similarly describes the pervasive impact of Western listening on the epistemic, cultural, historical, legal, and health complications of the displacement of traditional song and the violations and ongoing consequences of real-world colonial listening.Footnote33 The risk of sharing our Đông Sơn drum within the inconvenient and culturally risky politics of the Australian War Memorial meant that Victoria and I could have these conversations with senior Vietnamese musicians and composers. We made new connections with parts of the Vietnamese communities that gave us surprising insights into the complexities involved in sound reclamation. The compromises and risk taking that is necessary in order to engage with our own community and work with the overt nationalism at the Australian War Memorial was demanding. Ultimately, our project requires continuous, collective, and personal risk taking. It also requires novel and contradictory relationships with problematic institutions in order to ensure imperfect modes of diverse access and cultural practice.

Diasporic Resonance

By working imperfectly inside, outside, and alongside the museum to activate the Đông Sơn drum, Victoria and I managed to work and learn from multiple partners, collaborators and communities. This meant that we were able to engage in embodied forms of dialogue and practice. The difficult situation is that our families and communities around us, although deeply connected and invested in this project, ultimately lack the resources, power, and authority that only large institutions and their major collections of ethnographic and cultural materials can offer. Their capacity to take collective risk and innovatively bring together local and dispersed communities to sound once silent drums and expand our project through word of mouth, online links, and local community performances is inevitably limited and lacks the scale and curatorial reach of a major organisation. The Đông Sơn drum and all of the ‘ethnic’ instruments held captive inside museums have a power, history, and a cultural knowledge that far exceed what Victoria and I and our collaborators can uncover. We cannot resound all institutionalised instruments. Nor can we even imagine to comprehensively explore and listen to the two drums we have purchased in their historic totality. However, these instruments, like the ancestors that created and gave them life, still live through the small contributions that have helped us to shape digital and social resources for future practitioners and communities.

Victoria and I do not have or want to claim any form of authority over these instruments or control how they might be preserved, used, or kept or contained by institutions and communities into the future. In a way, our very ears, and the ways in which diasporic peoples have been raised in parallel with these similarly dispersed and silenced instruments, are irrevocably changed by the Westernisation and alienation of how we listen. Calling to mind the ‘hungry listening’ of First Nations song lines and ontologies as described by Dylan Robinson, our ears are starved of the auditory connections with our ancestors. We cannot hear their instruments. And as much as these museums are hungry to capture things that threaten their institutional authority, we have learnt that sound reparation demands a level of risk, nuance, and imperfect compromise that is not only uncomfortable, but demands much more from our public institutions, and more importantly, more from us as people bound to our communities.

Along this journey, we have come to realise that although we can occasionally exist outside of the museum, we cannot exist outside of our families, and the diasporic communities and raucous networks of collaborators, researchers, and practitioners who viscerally give meaning to these connections. Reclaiming the instruments of our ancestors and reclaiming how we generate sounds and learn again to listen, is more demanding than what these museums are willing to do. We not only have to risk physically damaging and destroying the instruments we have bought in order to break the greater risk of imposed institutional silence. This process, although profoundly fun, thrilling, and experimental, has the potential to put ourselves, our collaborators, and our communities at risk. What we hope for is the collective capacity to expose our ears to instruments that have sat silent for a long time, and to break up the modes of listening that we have become accustomed to as people resettled far from our homelands. Perhaps, like our ancestors, the risk of breaking these precious instruments and creating a noisy and uncomfortable racket is absolutely necessary to preserve culture and our struggle for existence. The risk of object destruction, of being offensive, of trespassing cultural taboos, might all be necessary to prise apart the convenience of institutional silence.

If nothing else, the deafening clang of metal rods striking the surface of the Đông Sơn drum has the capacity to conjure up the stormy and troublesome question of object repatriation and the possible practice of cultural rematriation. For diasporic communities estranged from their homelands, this is something that we continue to learn from and be engaged with through the groundwork of our Indigenous and First Nations colleagues and their forebears. The noise from these drums will always call us to attention, but more importantly, bring us closer together—either in curiosity, or in alarm. These drums teach us to focus and concentrate on what is important for people who are under threat of losing their existence and the right to have a future. Strangely, it is the courage to engage with new technology and absorb the risks and mistakes of experimentation where we can start to make the most of what has been taken away from us.

Notes

1 Rematriation is a First Nations concept that addresses the conceptual limits of repatriation. Adapted from the return of prisoners of war and unknown soldiers after WWI and WWII, the term repatriation usually describes the return of ancestor remains and sacred cultural materials back to traditional owners. According to Shawnee Lenape writer Steven Newcombe, and Ngarinyin Gija academic Dr Vanessa Russ, repatriation often involves bringing ancestor remains and cultural materials back to Stolen Lands and ongoing settler-colonial legacies that continue to enact violence, exploitation, and genocide on First Nations communities and knowledge systems. Rematriation demands institutional and societal guarantees to support and strengthen the multigenerational restoration of First Nations cultural practice, knowledge networks, and spiritual custodianship against expedient policies that merely seek to dispose of and absolve the state from the multifaceted responsibilities of inheriting other peoples’ ancestral remains and cultural materials.

2 Kimberley Moulton, ‘Reframing Aboriginal Cultural Material Through Contemporary Art’, Hester Magazine, 1 August 2014, http://hestermagazine.com/2014/08/01/reframing-aboriginal-culturalmaterial-through-contemporary-art/.

3 Ien Ang, ‘The Predicament of Diversity: Multiculturalism in Practice at the Art Museum’, Ethnicities 5, no. 3 (2005): 2, https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796805054957.

4 Ibid., 3.

5 Ien Ang, ‘Unruly Multiculture: Struggles for Arts and Media Diversity in the Anglophone West’, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, 18 July 2022, 34, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1271.

6 Ibid., 13.

7 Ionian design motifs for the AGNSW, and Corinthian at the Australian Museum.

8 The Art Gallery of NSW has two bronze drums that had previously been labelled as Vietnamese Dong Son drums; after interacting with our collaboration for Re:Sounding, the updated description now reads: ‘Frog Drum, Guangxi Province, China, Unknown Ethnic Minority, circa 500 CE–1000 CE.’ The only consistent pieces of information on these drums are their accession numbers and their record of provenance as a ‘Gift of Dr J. L. Shellshear, 1954.’ For many Vietnamese, the year 1954 is associated with the catastrophic internal displacement of Northern Vietnamese into the South of Vietnam following the defeat of the France and the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. ‘Drum, circa 500 CE–1000 CE, Artist: Unknown, China’, Art Gallery of New South Wales, https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/9032/ (accessed 21 January 2022).

9 Vicki Oliveri et al., ‘Art Crime: Discussion on the Dancing Shiva Acquisition’, Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice 6, no. 4 (2020): 307–319, https://doi.org/10.1108/jcrpp-03-2020-0033; Malia Politzer and Peter Whoriskey, ‘Global Hunt for Looted Treasures Leads to Offshore Trusts’, The Washington Post, 5 October 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2021/met-museum-cambodian-antiquities-latchford/.

10 Cressida Fforde, Jane Hubert, and Paul Turnbull, The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2002), 63–86.

11 Paul Turnbull, ‘Managing and Mapping the History of Collecting Indigenous Human Remains’, The Australian Library Journal 65, no. 3 (2016): 205, https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.2016.1207714.

12 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 12.2: States shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with Indigenous peoples concerned. ‘UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’, Australian Human Rights Commission, https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/un-declaration-rights-indigenous-peoples-1 (accessed 23 February 2023).

13 From my experience of working with multiple Australian arts organisations this sentiment is quite dubious, as I am often not told which communities we are explicitly representing but implicitly told to represent my cultural backgrounds through diverse artistic commissions.

14 Aruna D’Souza, ‘A Feminist Diary’, Canadian Art, 21 February 2019, https://canadianart.ca/essays/a-feminist-diary/.

15 Sara Ahmed, ‘A Phenomenology of Whiteness’, Feminist Theory 8, no. 2 (2007): 149–168.

16 Stéphanie Cassilde, ‘Where Are You from?’, in The Melanin Millennium, ed. Ronald E. Hall (Dordrecht: Springer, 2012), 116, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4608-4_8.

17 Catriona Ross, ‘Prolonged Symptoms of Cultural Anxiety: The Persistence of Narratives of Asian Invasion within Multicultural Australia’, Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, no. 5 (2006): 86, https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/JASAL/article/view/10168.

18 Scott Morrison, ‘How Good Is Australia! How Good Are Australians! Thank You! 🇦🇺’, Twitter, posted 18 May 2019, https://twitter.com/ScottMorrisonMP/status/1129765164302176260.

19 U.S. Embassy in Canberra, ‘Remarks by President Trump and Prime Minister Morrison of Australia at State Dinner’, U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Australia, 20 September 2019, https://au.usembassy.gov/remarks-by-president-trump-and-prime-minister-morrison-of-australia-at-state-dinner/.

20 The term minor here refers to the minority strategies of annunciation and presencing as articulated by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, in reference to the politically subversive potential of ‘minor literature’, whereby the minor retains autonomy and resistance within a majoritarian structure.

21 Sayyed Rahim Moosavinia, Karlis Racevskis, and Sasan Talebi, ‘Edward Said and Michel Foucault: Representation of the Notion of Discourse in Colonial Discourse Theory’, Journal of Research in Applied Linguistics 10, no. 2 (2019): 182–183.

22 James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 188–219.

23 Robin Boast, ‘Neocolonial Collaboration: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited’, Museum Anthropology 34, no. 1 (2011): 65, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01107.x.

24 Ibid., 65.

25 Sara Ahmed, On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

26 Candice Hopkins, in ‘Beyond the Guest Appearance: Continuity, Self-Determination, and Commitment to Contemporary Native Art’, a panel featuring Nicholas Galanin, Ashley Holland, Candice Hopkins, and Steven Loft, moderated by Dyani White Hawk, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN, 27 February 2018. ‘Beyond the Guest Appearance: Continuity, Self-Determination, and Commitment to Contemporary Native Art’, Walker Art Center, video, 2 hr 2 min 5 sec, https://walkerart.org/magazine/panel-discussion-native-arts-nicholas-galanin-ashley-holland-candice-hopkins-steven-loft (accessed 24 February 2023).

27 An audio stem is a discrete or grouped sequence of sounds mixed together as a single audio unit.

28 Jacob W. Gruber, ‘Ethnographic Salvage and the Shaping of Anthropology’, American Anthropologist 72, no. 6 (1970): 1290–1299, https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1970.72.6.02a00040.

29 Steven Newcomb, ‘Perspectives: Healing, Restoration, and Rematriation’, American Indian Ritual Object Repatriation Foundation News & Notes (Spring/Summer 1995), 3, http://ili.nativeweb.org/perspect.html.

30 Uzi Baram and Yorke Rowan, ‘Archaeology after Nationalism: Globilization and the Consumption of the Past', in Marketing Heritage: Archaeology and the Consumption of the Past, ed. Yorke Rowan and Uzi Baram (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2004), 5–9.

31 Elizabeth Lillehoj, ‘Stolen Buddhas and Sovereignty Claims’, in Art and Sovereignty in Global Politics, ed. Douglas Howland, Elizabeth Lillehoj, and Maximilian Mayer (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 141–167, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95016-4_6.

32 Ahmed, On Being Included, 32.

33 Dylan Robinson, Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 37–76.