Abstract

This article portrays the exchange of objects (trees), which creates trust and belonging between Butonese migrant farmer tenants, who are often Muslims, and Indigenous groups (landowners) in Maluku. The multifunctionality of trees and the flexibility of the land tenure system in Maluku have shaped the Butonese migrants’ sense of belonging and established their social and economic relations with the host society that provides the land. The ability of Butonese farmers to manage the landscape, especially by taking care of the trees, has made it possible for them to live consistently in Maluku for more than a century. Communal conflicts in the 2000s sought to expel them from the Maluku archipelago. Instead of returning to their origins in Sulawesi Island, their sense of belonging with the trees helped them to re-emerge and reconstitute mutual relations with their predominantly Christian Malukan landlords (tuan dusun).

Introduction

Malukans have a long history of relying on trees as a resource in economic exchanges and reciprocal relationships. Cloves, nutmeg, and copra have not only helped Malukans get acquainted with the world of commerce (Donkin Citation2003; Kadir Citation2018) but these tree commodities have also attracted migrants from outside the Malukan archipelago to seek their fortune. Of those migrants who came to farm and trade, the majority are from Bugis and Buton in Sulawesi. Waves of Sulawesi migrants have lived throughout the Malukan archipelago since at least the beginning of the seventeenth century (Ellen Citation2003). Historians have even estimated that people from Sulawesi migrated to Eastern Indonesia as a result of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) conquering Makassar from 1667 to 1669 (Andaya Citation1995, 116–117; Sutherland Citation2021, 155–157). In Southeast Asia, including Eastern Indonesia, the inclusion of newcomers has to do with labour scarcity (Reid Citation1995; Carnegie Citation2010, 453).

Over time, villages across Maluku appear to have sustained cooperative relations of coexistence since they required extra labour to take care of the abundant land and forests. Malukan villagers welcomed certain migrants as labourers in spite of their different ethnicity and religion. The local Malukans provided them with vacant land along the boundaries of large Malukan villages. On Ambon Island (Adam Citation2010), Buru Island (Grimes Citation2006), and Banda Island (Winn Citation2008), in order to work the land, migrant farmers obtained permission through customary land agreements (tanah dati/petuanan).Footnote1 In a gesture of reciprocity, the migrants contributed a share of their profits from terrestrial and marine production to the head/leader of the petuanan.

Migrants took advantage of land outside customary law holdings by planting a variety of crops. As in the case of Hila and Kaitetu villages on Ambon Island, the Butonese were even able to buy some land privately to cultivate vegetables rather than long-term crops (Brouwer Citation1998). The Butonese communities in Seram and surrounding islands focused on cultivating vegetables and cassava instead of long-term crops, given that migrant communities under Malukan customary law held a secondary position in user rights to land. The vegetable crops not only required smaller investment but were also less exposed to risk of dispute over ownership of land. The Malukans welcomed the arrival of migrant Butonese, hiring them through sharecropping agreements to pick the fruit from their fruit trees (Adam Citation2010, 191).

This article focuses on the proposition that tree crops sustain relations of mutuality in Malukan landscapes. These crops play a role in changing the landscape and can even become the property of the migrants who, when they first came to Maluku, did not have the right to own land. In this article, I question how the system and nature of property rights in Maluku allow migrants to establish reciprocal relations by sharing crops and, thus, have a sense of belonging to the trees and land in Maluku. I argue that even though such reciprocal relations, forged over generations, could not prevent the ethnic and religious conflict that happened during the transition era in 1999, both Malukan and Butonese farmers have developed their own ways to recover their social relations and economic transactions. I show how these tree crops have allowed Butonese migrants who had fled the conflict to become reconciled with their Malukan landlords (tuan dusun).

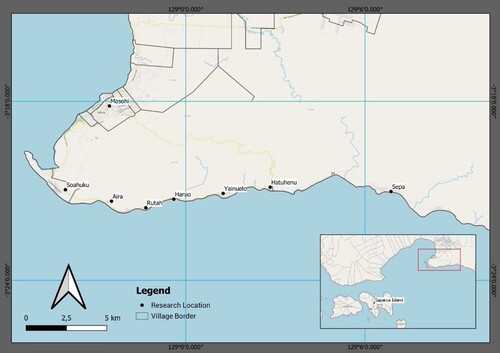

I carried out research from 2015 on Seram Island, Central Maluku, where I interviewed Butonese farmers, Malukan tuan dusun, tree cultivators, hamlet heads (raja), and traders who bought tree-crop products.Footnote2 I also obtained secondary data from two local newspapers, Ambon Ekspress and Suara Maluku, from October 2016 to October 2019, especially regarding fluctuations in copra prices, the condition of farmers in Maluku, and inter-ethnic relations between local Malukans and farmers of Butonese descent.

I spent a considerable amount of time in two Butonese migrant villages, Aira and Yanuielo, located in South Seram Island. Aira is a hamlet of Soahuku village. The population of Aira had increased because many displaced Butonese from Saparua in the Nusalaut islands moved there during the conflict between Muslims and Christians. In 2015, Aira comprised 230 heads of household, predominantly Muslim, while Soahuku village, which provided land to the Butonese, was a Christian village. Soahuku as ‘patron’ village provided living space, protection, and land for the Butonese to work. During periods of political turbulence, including the Japanese occupation in 1945, the communist massacre from 1965 to 1966, and the sectarian conflict in 1998, the raja of Soahuku gave permission for Butonese to live in this village. In Aira, many of the copra farmers still work the land owned by Christians in Soahuku ().

Property Rights in Maluku

Malukan property relationships operate within a diverse and flexible agro-economic system. Different tree resources may be subject to the same property law, but they have widely divergent functions for social continuity and economic security (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation1999, Citation2007). Tree crops include a bundle of rights that reflect relations of kinship, patron and client, neighbourhood, and membership in religious or ethnic groups.

In Maluku, a distinction between public and private spheres of law is not always made. Cornelis van Vollenhoven, a Dutch legal scholar who worked on legal land systems in the East Indies, identified adjustable Indigenous adat/customary land. Under indirect rule, the Dutch authorities gave more power to customary laws and avoided imposing a single jurisdiction over Indigenous people and their adat laws (Li Citation2000). Van Vollenhoven pointed out that, unlike property ownership in Western legal systems, Indonesian Indigenous rights of possession did not distinguish private and collective ownership, which made the land easily transferrable between the collective and the individual (von Benda-Beckmann 2019). Likewise, a migrant could claim Malukan land and trees because of the more flexible jurisdiction (especially in majority Muslim villages) (Cooley Citation1969). These rights of possession made property status less restrictive and somewhat ambiguous. This fluid arrangement was enhanced by the lack of formal representation and political organisation in Maluku, with the result that property disputes were not easily contestable. This flexibility was shown where new cultivation of gardens or permanent crops on customary land was allowed merely with the consent of the landlord (tuan dusun). In return, the migrants offered cash payments, as well as political support (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation1994, 598).

In general, customary land tenure in Central Maluku recognises three forms of land rights (Effendi Citation1987). The first form comprises dati/petuanan land or collectively owned land, which belongs to several clans (marga). As the common property of a group of clans, petuanan land is not subject to certification. The second form of land rights concerns tanah marga or clan-owned land. The management of clan-owned land is regulated by the clan head. The third form, tanah pusaka, comprises land that belongs to individuals or a nuclear family. Tanah pusaka is mostly granted through patrilineal inheritance. In Maluku, land is inherited through the male line; however, it can be transferred between clans through marriage (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation1999). This customary system is also then integrated with Islamic laws (fiqh), where daughters are entitled to half the share of land that their brothers receive. However, because the eldest male generally organises the land inheritance, arrangements for granting inherited land to sisters can be flexible depending on the closeness of relations between the eldest brother and his sisters. Elders give the right to access land individually to their junior members, thus disputes about trees and land are more about personal rights. One reason for elders giving their sons separate gardens is to prevent inheritance conflict among themselves.

Each Malukan individual who belongs to a clan has the right to collect forest products from the land such as wood, rattan, honey; to hunt wild animals; and to gather tree products that grow wild, including medicinal plants. They can also clear the land and work the land continuously. With the awareness of the village head (kepala negeri), an individual can turn a piece of tanah petuanan into individual ownership, but only by proving themselves through opening the forest and turning it into a garden dusun (secondary forest for permanent crops). The process of working to clear forest land is called parusa. Parusa land is thus in transition from forest land to private or collective property. Extensive forest land occurs throughout Eastern Indonesia, and the limited number of workers creates an unwritten collective agreement that land can become private property if somebody devotes their energy caring for and cultivating the land properly (Li Citation2014). Through parusa work, the clan over generations may turn the land into pusaka. In this situation, a village head may issue a permit releasing a piece of land for private ownership by future generations of a clan.

Within communal inherited property, petuanan land, there is also self-acquired property, which can be restructured into individually-owned property, facilitating the marketability and profit-oriented production of cash crops. Over time, cultivators change the land status to private property ‘silently’ rather than through a formal legal process (Effendi Citation1987, 93). In general, the cultivator does not have an official certificate stating that the land they cultivate is their personal property. This is because the community has not yet recognised the concept of ‘property rights’ in a formal legal sense, e.g. land certification.Footnote3 However, not all land certifications in Maluku are derived from petuanan land, as customary and state laws are different. Even though land certification in Maluku aims to follow state procedure, arguably the more important task is to make land an asset that can be rented or sold to potential buyers (Tihurua Citation2018). One reason for this transformation to private land ownership is population pressure owing to the coming of migrants from Sulawesi and Java, which has increased the demand for cash cropping land.

This land tenure system stems from the nature of customary laws (adat), which are flexible in accommodating great changes occurring within communities. Although certification is a state procedure, and very different from adat processes, adat can pragmatically transform economic events that occur in the villages (Frost Citation2004). Thus, the transformation of land ownership from communal to private has been facilitated by various influences: the introduction of cash cropping that began in 1980; land scarcity due to the influx of migrants (especially in the coastal areas since the 1970s); and market individualism that has allowed the sale of land, which has been happening since the 1980s (Ellen Citation1997).

This complexity, and the flexibility of the relationship between land and trees, is shown in the different layers of property based on the respective functions of land and trees and their mutual interrelationships (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation1999, 26). In other words, the status and definition of land is determined by the types of tree crops that grow on the land and the nature of labour deployed. From my observations and conversations, Malukans in general have three different terms for land: forest (hutan), secondary forest (dusun), and garden (kebun).

Hutan refers to forest that remains potentially unused and still owned as Malukan customary land or petuanan land. The Malukan divides forest or hutan into two: ewang refers to primary forest, and aong is secondary forest (Tihurua Citation2019, 25–26). Ewang is forest commonly owned under the management of traditional village administration or negeri petuananan, while aong refers to forest managed by a Malukan individual that is the property of the clan or individual who takes care of it.

Dusun refers to land that is cultivated with permanent crops or tanaman umur panjang. The life span of these crops is between twenty to thirty years and includes cloves, nutmeg, coconut, sago, and many other trees. A kebun, or garden, is planted with short-term crops or tanaman umur pendek (literally short-age crops). These are typically garden vegetables such as chili peppers, tomatoes, cabbage, and ground crops such as peanuts, eggplants, and cucumbers. The land use definitions of kebun and dusun often change depending on the transformation of the trees that people plant. A kebun can become a dusun when farmers convert from short-term to long-term crops. The definition is very fluid because migrant farmers who rent the land usually cultivate both long- and short-term crops in the same location.

It is also possible for kebun and dusun to revert to hutan; for instance, if the land is abandoned because of a long conflict such as in 1999. The land is left for shifting cultivation and reverts to hutan while its fertility is restored. When dusun are abandoned and revert to hutan, the status of the land is called ewang. Another possibility is that the land is abandoned when the productivity of commercial crops starts to decline, perhaps attacked by pests. In these cases, the abandoned land turns into forest (Matinahoru Citation2013). During this ewang period, the status of the land reverts to petuanan.

The central feature of Malukan terrestrial-based economies is long-term crops planted in dusun. There is adaptability in the village economy in selection of the most profitable crop commodities (Rudyansjah and Tihurua Citation2019). In the sites where I conducted research, kebun are mostly created by Butonese sharecroppers, while dusun can be created by both local Malukans and sharecroppers. However, Maluku villagers also have kebun. In addition to sago and cassava, which are the dominant local foodstuffs (Ellen and Soselisa Citation2012), they also plant chilies, tomatoes, cucumber, and mung beans, but the scale of cultivation is not as extensive as that practised by Butonese migrants. Additionally, in Malukan villages where Butonese migrants have resided for generations, most landowners have entered into agreements with Butonese to farm their land.

Many Butonese have gained the trust of Malukan tuan dusun by taking care of their idle land. Gardens (kebun) become the means through which Butonese farmers win their trust and enhance their caring activities. In these gardens, careful cultivation takes place through the sharecropping system. Gardens are the beginning of Butonese efforts to organise their territory as migrants, as well as a way for them to grow a sense of rural entrepreneurship in the place where they live. In their gardens the Butonese plant coconut trees with a variety of fruit trees and short-age crops, including mustard greens, mung beans, chili peppers, peanuts, and spinach. These short-age crops are sold easily in the market and bring in immediate cash.

Butonese sharecropping can persist through multiple generations, with the system of exchange and trust becoming consolidated over generations. Children who inherit land from their parents usually continue the rent system with those Butonese entrusted by their parents. In Aira, one of the elders, Wa Ina, a first generation Butonese woman resident since 1966, told me that she and her late husband had cultivated the garden provided by their tuan dusun, caring for the latter’s crops (tanda mata) while interspersing these with her own new tree crops, the land remaining with the tuan dusun. In the long run, long-term crop cultivation turned into balanced mutual service. Alongside the coconut and nutmeg trees, Wa Ina had also planted durian, langsat (duku), mangosteen, and mango—the yield of which both her family and the tuan dusun’s offspring could enjoy.

The ownership of property becomes ambiguous when migrant farmers cultivate long-term crops on their rented land. Caring for the landlord’s garden is an act that resembles a gift but is actually a future investment wherein the Butonese farmers project the bond with their Malukan tuan dusun continued in future generations. The next generation of Butonese farmers perceive their rights to the trees because they or their parents cultivated the land. The trees belong to them since they have engaged in more intensive clearing, burning, and gardening than their landlords. In this way, trees become Butonese property since the preceding generation cultivated them. For Butonese farmers, the tree crops, including fruit trees that they cultivated on Malukan land, are a gift to the tuan dusun, but this kind of gift is enigmatic because the Butonese as givers later have the right to full ownership of the trees. Some trees were planted by local Malukans and always remained their property, while other trees were planted by the sharecropper and became their property—although the land never became their property. During fieldwork, I met young people in Soahuku village who were the Malukan tuan dusun of the Buton tenants in Aira, a patron-client relationship inherited from their parents. The process of transferring land ownership, however, is certainly unsettling for local Malukans. Some villages such as Saparua have only small tracts of land and, consequently, many Butonese became displaced during the 1999 conflict.

Marketing Crops

Compared to local Malukans, the Butonese were enthusiastic about the agricultural intensification project, especially short-term crop production. They maximised their vegetable crop production by using pesticides and herbicides (Bertrand Citation1995). Compliance with modern farming, as sponsored through state development projects, was a strategic way for them to be recognised as Indonesian citizens, as they did not have customary rights to own the land like Malukan clans. For being industrious in their work, enthusiastic towards development projects, and carefully managing their trees, the rural Butonese have increased their economic productivity. The migrant farmers are also more concerned about taking care of the trees growing in kebun and dusun as these bring economic profit to them. They measure the value of the garden based on the trees that are growing there.

Transactions with tuan dusun are generally conducted using two systems. In the first, they rent land which they then plant with long-term trees, such as clove or coconut, or they rent land already planted with trees. In this rental system, the farmer pays rent in advance to the tuan dusun. Farmers cannot assess the value of empty land that has no trees growing on it;Footnote4 thus, they basically rent both land and trees. When they rent the land planted with coconut trees, the contracted rent of trees between the tuan dusun and the Butonese farmer is determined by the number and quality of the trees, as evidenced by the density of the coconuts on a single tree. Farmers usually rent coconut trees when they are ready to bear fruit. If they see that the coconut trees are old and appear ready to fall to the ground, it means the quality is inferior and the rent will be correspondingly lower. Farmers tend to rent trees with coconut shoots that look ready to grow bigger. They are looking for young greenish ones rather than old ones that look dark-brownish. One of the reasons why Malukan landholders rent out coconut trees into Butonese care is that there are not enough trusted workers to care for such a large number of trees.

Another reason relates to the profit-sharing system wherein the farmer provides their labour services by taking care of the dusun or kebun, with the harvest income divided 50:50 between farmer and tuan dusun. Both parties can predict the yield and net income they can earn after deducting costs for the harvest operation. Farmers can estimate that one tonne of dry copra can be produced from around 450 coconuts. During a long drought, the size of the coconut shrinks, reducing the yield to 550 coconuts per tonne, meaning sixty coconut trees will produce between 400–500 kilograms. If the price of copra is Rp. 6500 per kilogram (in 2018/2019), then farmers multiply this by 500 kilograms, which means they will earn approximately Rp. 3,250,000. The farmer will then share half of this amount with the tuan dusun. To sum up, after deducting the costs of paying the climbers plus transportation, farmers will receive Rp. 1,500,000.

From the perspective of the Malukan villages where Butonese migrants have resided for generations, leaving land in the care of Butonese farmers creates an obligation for the Butonese as migrants. The Malukans, as host, provide hospitality to their foreign guests, the Butonese, by allowing them to work on a piece of land. In return, the guest shares the harvest with the host, who has provided the land.

Property Relations and Conflict

Compliance with state projects has led migrant ethnic groups to become more successful in rural entrepreneurship. Their success in local economies has made them a target of negative sentiments, especially during the hard economic times in 1998. In Christian villages, Butonese and Bugis were consequently blamed for the failure of Christian Malukans in political and economic matters. Many Christians experienced difficulty accessing formal sector positions as teachers, civil servants, and private office workers in competition with migrants who had been able to improve the rural economy, access higher education, and get into jobs in the formal sector (Adam Citation2010; Sholeh Citation2003). The wave of Sulawesi migrants to the Central Malukan archipelago put pressure on land availability and changed property relations. Based on fieldwork conducted in the 1960s, Dutch scholar Chris van Fraassen noted that on the island of Saparua, Central Maluku, many local people were confronted with limited access to land and were forced to search for jobs outside agriculture (Adam Citation2010, 17). This increasing land scarcity was also noted by legal anthropologist Franz von Benda Beckmann when conducting fieldwork in the Ambonese village of Hila in the 1980s. Von Benda-Beckmann and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann (2007) noted that scarcity of land in Central Maluku had led to local Malukans increasingly wresting control over the land from the migrants.

Many traditional village heads (raja), especially those who live on smaller islands, worry that cultivating slow-maturing trees incites tension and disputes over belonging between the host society and the outsiders. Therefore, to avoid disputes of belonging, and because of the limited amount of land, many raja prohibit migrant farmers from cultivating long-age crops.Footnote5 These raja only allow migrants to cultivate vegetable crops, which have easier and clearer contractual accounts.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, the arrival of three ethnic groups, abbreviated as BBM (Buton, Bugis, Makassar), but especially Butonese migrants, contributed significantly to land pressures and conflicts with Malukans regarding land rental contracts (Ellen Citation1997). BBM not only demographically increased the Muslim portion of the population, but they also dominated economic livelihoods and market exchanges throughout the rural and urban areas (Kadir Citation2017). The massive influx of Butonese migrants who dominate tree cultivation has given rise to a sense of common jealousy and threat among local Malukans. This dominance stems from harvesting arrangements that are often favourable to the BBM. When the prices of cloves or copra rise, they can save their profit to expand their leases. Although they do not necessarily end up owning the land, dominance of tree leases often leads to disputes and jealousy among the Malukans. In the village of Hila on Ambon Island, relations between Butonese communities and Muslim Malukans have always been tense. Low-level violence, manifesting in verbal and physical aggression, often occurred in several villages with Butonese populations (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation2007).

The influx of Butonese migrants, who become intensely engaged in the planting and care of trees on rented Malukan land, has often spurred land dispute cases. These disputes occur due to the verbal agreements conducted between Malukans and Butonese regarding the land and trees. Most of the incidents stem from disputed interpretations of institutional arrangements for managing crop resources (von Benda-Beckmann Citation1991, 250–252). Therefore, to avoid disputes over property, migrant farmers have sought to ‘legalise’ their tree holdings by recording all of the rental agreements on a stamped receipt.

Tree crops and land represent two different kinds of ownership that can lead to disputes between Butonese tenants and Malukan tuan dusun (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation1994, 597). Throughout Central Maluku, including Seram, most of the disputes concern the duration of contracts and tree yields that differ from the pre-harvest agreements (Hospes Citation1996, 20). The migrant farmers are very aware of the uncertainties and risks in clove and coconut production. They rent clove and coconut trees in advance at a much lower price than during the harvest. The length of the lease period often leads the tuan dusun to revise the agreement, midway, especially when the price of crops on the leased land skyrockets. Farmers note that the price of copra and clove are volatile, with the ups and downs of price determined by Chinese middlemen. Rental agreements depend on the length of time and the number of trees. The more trees they rent, the cheaper the price and the longer the period of the contract. Butonese farmers with more money can rent many more trees, and for longer periods. One of the land disputes that occurred during my research concerned a long lease contract, more than four years, and when the tuan dusun learned that both copra and clove prices had increased dramatically, they raised the rental price in the middle of the contract.

In the 1990s, disputes about land and tree ownership rights between migrants and locals were still seen as personal and did not extend politically into inter-ethnic conflict. During the process of these disputes, the rest of the villagers were mere onlookers. If a dispute over rent of land was not resolved, the parties would take it to the highest village authority or to court (von Benda-Beckmann 1991).

In 2000, the communal conflict that initially began in Ambon, the capital of Maluku, finally spread to many islands around Ambon, including Saparua and Seram islands. Due to the low intensity of the conflict, the mutual work between Malukans and migrants continued but was finally destroyed by the larger ethnic conflict of 2000. While the conflict largely arose from outside these communities, it still destroyed the mutual respect that had been built over generations. The conflict in Seram Island broke out in 2001. The conflict also spread to Saparua Island in 2001, causing Butonese communities to leave the island. The Christian majority attacked and burned six Butonese hamlets. The aggressiveness of Buton farmers in leasing clove trees throughout the 1990s had created anxiety among Saparua people that one day their lands would be bought and controlled by Butonese farmer communities. This anxiety was realised when conflict broke out in Saparua in 2001. Seeing the situation on neighbouring islands, where Christian Islamic conflicts had broken out, the Saparua people finally made the decision to expel these Buton Muslims. The Butonese fled the island on motorboats across the Arafura Sea to South Seram. Rather than returning to their place of origin in Buton, Southeast Sulawesi, the displaced Butonese from six villages in Saparua Island moved to other Butonese kampong on Seram Island, just north of Saparua. There they were familiar with the social structures in Saparua where they had been tenants. Through trees, the Butonese could be incorporated within the system of exchanges built over generations with Malukan tuan dusun.

Blair Palmer (Citation2004) noted that communal conflict also led hundreds of thousands of Butonese descendants to flee to Buton, Southeast Sulawesi Province, but they felt alienated and eventually returned to Maluku. Apart from incompatibility with the social conditions and farming system in Buton, these refugees missed their dusun (land predominantly cultivated with trees) in Maluku where, through long-term crop activities, they had built systems of debt, care, investment, and reciprocity sustained intergenerationally.

Reconstituting Property Systems in the Aftermath of Conflict

During these times of conflict, both Muslims and Christians were victims. In the beginning, Butonese houses in the Saparua islands across from Seram Island were burned to the ground. After the Butonese left Saparua, the Christian Saparua took over their trees but only for one harvest due to the vast area of land used by Butonese and the lack of local Malukan labour to take care of the trees. Many clove and coconut trees were abandoned and died. In Aira, farmers who had become refugees owing to the conflict did not have enduring relationships based on trees with their tuan dusun, the Christians of Soahuku, and, therefore, had to build trust with them in order to gain tenancy rights.

I argue that tree crops can enable social agency not only by generating income but also by reconnecting people in the aftermath of conflict and making it possible for migrants and locals to reconstruct their disrupted sharecropping. Tree sharecropping has become a way for Butonese farmers to both earn recognition as Malukan citizens and cultivate their sense of belonging. Sharecropping can be seen as an old system of agriculture, prevalent before the emergence of a more progressive agrarian system based on fixed rents and wages (Robertson Citation1980, 412). In the context of Maluku, I observed sharecropping as a tradition that ties Butonese farmers to their Malukan tuan dusun, even though the conflict had disrupted this kind of reciprocity. The tuan dusun, as the supplier of land, needs Butonese because of the lack of local Malukan labourers willing to take care of vast expanses of land. Rather than being a way to extract a surplus from farmers, sharecropping helps to maintain mutual obligations and profit sharing between Malukan landholders and Butonese farmers as tenants. Butonese farmers tend to see sharecropping from the perspectives of care and investment. Cultivating long-term trees becomes part of the process of reconfiguring personal identities while framing a sense of belonging to the Malukan land.

To describe the reconstruction after the conflict, I will start with the story of La Udin,Footnote6 who was expelled from Saparua during the conflict. La Udin, a refugee farmer who arrived in 2001, obtained permission to work on land in Aira that was owned by a Christian landowner in Soahuku. Tuan dusun in Soahuku provided for displaced Butonese farmers in Aira not only due to the land’s relative abundance but also because of their parents’ long experience working with Butonese tenants. Soahuku tuan dusun realised that Butonese in Aira could be trusted to grow and maintain trees. The tuan dusun accepted these Butonese refugees due to the scarcity of labour, especially in the aftermath of conflict that had resulted in abandonment of the land and trees for years. Soahuku tuan dusun accepted Butonese refugees to live on their land in order to increase the number of trusted labourers and, in doing so, gained through either the division of income or through rent, depending on the agreement made (Kadir Citation2019).

One of the initial ways that migrants gain the trust of landowners is through pameri. Pameri is an act of care and performance that shows responsibility by taking care of the land. Through pameri, La Udin showed the landowner that he could look after the land and not let it turn into secondary forest, neglected as a consequence of the conflict. La Udin, like other Butonese farmers, considered pameri as a way to ‘set apart the garden’ (menyimpan kebun), treating the garden with the same energy as they would the cleaning of a Malukan’s house. To the Butonese farmers, pameri is important to show their sense of care for the land they rent. In the long term, the aim of pameri is to make the tuan dusun happy. The tenant earns the respect of the tuan dusun when the tuan dusun checks his land and sees the tenant's careful cultivation. During such a visit, the tuan dusun also assesses how their land is taken care of through pameri.

Malukans entrust the Butonese to take care of their land; according to Butonese elders because planting trees is a tanda mata (emblem or momento) that signifies their gratitude to the tuan dusun. Planting fruit trees (pohon buah-buahan) alongside the tree commodities returns the favour (balas budi) of generosity by the tuan dusun who provided land. Cultivating non-commercial trees around the commercial ones is a responsible practice of care and belonging. When La Udin cultivated long-age crops, he cultivated additional trees as a performance of care to impress the tuan dusun. For example, nutmeg trees need shade trees around them to grow well. Butonese farmers voluntarily cultivate kenari (canarium ovatum) and durian trees, which are the most common shade trees to protect the growth of nutmeg trees. Unlike commercial crops, fruit trees are mostly seen as gifts but are actually an investment to earn the respect of tuan dusun. These trees are not harvested in a seasonal, mass way like cloves, nutmeg, and coconut. The farmers who plant the trees around the nutmeg own them and have the rights to harvest those trees, while tuan dusun need to ask permission if they want to pick them. Planting trees, therefore, is a means for Butonese farmers to gain respect, as well as extend their rental periods with the tuan dusun. While the fruit harvested from pohon buah-buahan does not have high value in the market, fruit trees are cultivated to lubricate social relations. (Durian also commands a high price in the market, but its harvest is not as reliable as that of copra and spices.)

In contrast, cloves and nutmeg—spices or rempah-rempah—have a long history as a high-value commodity in the global market (Kadir Citation2018). Therefore, their planting is significantly more extensive than those of fruit trees, and they remain the property of the landlord. The gift trees planted by the Butonese reflect exactly what Annette Weiner (Citation1992) describes as ‘keeping while giving’. The fruit trees are inalienable possessions, and as tanda mata they are given as investments that retain ties to the cultivators. As an investment, fruit trees cultivated around nutmeg and coconut trees cannot be fully commercialised and disengaged from the cultivators. The cultivation built around the moral code of care and giving provides the Butonese farmer rights over what they have cultivated, which, in turn, subsequently contributes to the long term of a contract, often culminating in the acquisition of the land itself. As an investment, coconut trees and other fruit trees around them are ‘immoveable property’ that become associated with the cultivators. Ellen (Citation1978, 175) pointed out that newly planted trees and palms are productive for up to 50–70 years, even longer. The land on which these trees grow thus can be passed down and inherited by the next generation of the person who planted the trees. The Butonese implement their vision by ‘keeping while giving’. Thus Butonese farmers cultivate relations of hope with their Malukan tuan dusun. In the first year of tenancy, La Udin rented a kebun. He cultivated chili peppers, vegetables, and cassava for his own consumption and to make some money. In the first season, La Udin harvested three thousand chili plants on the basis of a one-year contract with his tuan dusun. After a long tenancy of about ten years, he was finally allowed to cultivate long-age crops and started to plant coconut trees. In 2015–2017, during my fieldwork, La Udin was caring for three dusun that were mostly cultivated with coconut trees.

When Butonese farmers rent land to cultivate as an orchard with short-term crops, the tuan dusun often asks them to cultivate long-term crops also. Being allowed to grow long-term crops demonstrates growing trust between tuan dusun and Butonese farmers. However, it sometimes takes a long time for tuan dusun to sufficiently trust Butonese farmers to cultivate their land. Trust grows only after seeing the performance of the Butonese farmers. Once trustworthiness has been established, tuan dusun expect that production of long-term crops will extend to an ongoing intergenerational profit-sharing relationship between the children of the tuan dusun, as owner of the land, and the children of the Butonese farmers as the labourers or renters of the land. The production and processing of coconuts makes the intense relations between Butonese and Christians possible. Coconuts are usually harvested three times annually. Farmers use the coconuts that drop off the palm before harvest time only for their household needs, such as making coconut oil. Each month tenant farmers may harvest from up to three different pieces of rented land. For one harvest, La Kumang, my fieldwork host, produced at least one ton (1000 kilograms) of copra at the rate of 6000 rupiah per kilogram. Thus, each harvest, La Kumang earned six million rupiah, of which he gave his tuan dusun half.

Although the price of copra is not as high as the price of cloves, copra produce is reliable because it can be harvested during the long dry season. The division of profit from cloves and coconut is the same based on the profit sharing between the tuan dusun and the tenant farmer. After harvest, the farmers split half the money from the harvest and hand it over with a sales receipt to their tuan dusun. Unlike cloves, which can only be harvested once every year or two, copra can be harvested three to four times each year. This leads the Butonese tenants to meet their Christian tuan dusun more often, at least once a month, to discuss variations in the sharing and debt mechanisms that usually take place before the harvest.

In sharecropping tree crops, I found that even following the conflict, Christians and Muslims were able to build ongoing reciprocal relationships. After taking refuge in Buton, Sulawesi Island, for one year, La Kumang returned to Maluku. He continued sharecropping with the Christian tuan dusun in Soahuku village as he had done before the conflict. As a Butonese tenant, he had four contracts: three contracts with Christians in Soahuku and one with a Chinese trader from Soahuku living in Dobo in the Aru Islands.

The intimacy of the relationship between Christian landowners and Butonese tenant farmers is expressed through flexibility in relation to borrowing and paying land rents. Wa Lija, La Kumang’s wife, who usually handled her husband’s income, told me that if their Christian landowner in Soahuku needed cash, all he needed to do was buang suara (literally, ‘throw the voice’) to let her know about his needs. A couple of days before the copra harvest, Pieca, one of the Christian landowners, came to La Kumang’s house to buang suara. He needed cash for his daughter’s imminent wedding. Pieca and his wife drove motorbikes, and they often brought small gifts for La Kumang’s wife. I could see the intimacy in their relationship during their conversation together. Unlike a formal guest who would usually sit in the living room, Pieca and his wife came directly to La Kumang’s back door towards the kitchen. La Kumang’s wife gave fish and cash to Pieca’s wife—cash worth three times as much as the copra harvest, as an advance rental payment equivalent to a one-year land contract. (In the forthcoming copra harvest, La Kumang would not have to share any money with Pieca.)

Another landowner, Petra, asked La Kumang to rent his garden for ten million rupiah. Petra needed cash to support her son who wanted to enlist in the army. It was very common for parents to spend tens of millions of rupiah to get their sons admitted into the army or employed as a civil servant. In 2017, La Kumang only had four million rupiah, so he undertook to pay the remaining six million rupiah when the copra was harvested.

There are various types of cropping contracts between Butonese farmers and Christian tuan dusun. Mostly the Butonese share 50:50 of yields with the landowners, but if a Butonese farmer has more cash he usually rents the land for between 1–10 years. The credit paid by Butonese farmers in advance ensures that the Malukan landowners, out of economic hardship, gradually sell their land to Butonese farmers, especially when the price of cloves falls in the market. These various contracts demonstrate trust between Butonese farmers and Malukan tuan dusun, but in the terms of the exchange the contracts are purely transactional.

Although the conflict in Maluku provoked from outside has created a deep polarisation between Islam and Christianity (Bertrand Citation2002; Kadir Citation2013), it has not permanently stopped communication between these migrant farmers and Malukan landholder groups. Disputes regarding land rents occurred more often between individuals. The disputes I observed during fieldwork were exactly like those prior to the conflict period in 1999, as described by von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann (Citation2007). The scale of these individual disputes did not lead to communal conflict but, rather, reflect mutual misinterpretation in individual negotiations between landowners and tenants.

Conclusion

The system of property rights in Maluku is flexible and adaptive to changes in commodity crop prices for cloves, copra, and short-age crops. Customary (adat) law adapts in accordance with social needs. In the context of sharecropping, this has allowed migrant farmers to build reciprocity with Malukans, thereby improving migrant capacity to access land and creating a sense of ownership of the trees that grow on the land under their care. Additionally, the ability and willingness of the migrant community, especially Butonese farmers, to mobilise their energy to convert forests into gardens and plant them with coconut, as well as short-term crops, shows the entrepreneurial spirit of these farmers in response to market needs. Prior to the conflict in 2000, while individual disputes regarding agreements in property and land rent matters existed, the scale of conflict neither spread across villages nor caused massive displacement.

The large-scale conflicts in 2000 were triggered by external rather than internal influences, with the previous tensions between Malukans and migrant farmers directed at property issues not religion. However, the religious conflict in 2000 fuelled pre-existing sentiment and jealousy towards the Butonese migrant community, who were more successful in monetising coconut trees and short-term crops.

Following the conflict, displaced peoples have sought to reconstitute their relations with local Malukans through negotiating to grow perennial cash crops while respecting the land rights of owners by sharing income. This has been successful among the Bugis and Butonese settlers on Christian land but has not taken place where Christians were displaced from Muslim land.

Belonging based on the cultivation of trees is one of the reasons that Butonese descendants continue to be entangled with Malukan land. As a form of social agency, tree crops function to generate income and to reconnect people in the aftermath of conflict. Trees constitute a means for restoring harmonious relations among distinct ethno-religious groups where landowners depend on crop sharing with migrant farmers and are content with a share of the harvest income. Where such economic cooperation has not developed, ethnic harmony is much more difficult to achieve.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Patrick Guinness for his engagement in intensive conversation regarding the substance of this article, and for transforming the draft into a well-polished manuscript. Thanks are also due to the journal's anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive comments and the journal’s editorial office for preparing the manuscript for publication. Finally, thanks to Charlotte Blackburn for proofreading the draft before initial submission.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 All non-English terms in this article are in Indonesian.

2 Ethical clearance was obtained for this research from the Centre for Culture and Frontier Studies (CCFS) at Universitas Brawijaya, which gained research permission from Badan Kesbangpol, Kabupaten Maluku Tengah (Agency of National Unity and Politics, Central Maluku Regency). During fieldwork the author showed the permission letter from Kesbangpol in the process of obtaining consent from research informants.

3 Sitorus notes that the increase of land certifications in Maluku shows the massive shift towards individualisation of land ownership. In 2018, he estimated for Maluku Province 685,070 designated properties including 411,223 with certificate (Sitorus Citation2019, 227).

4 In 2018, the price of one kinta, which equals ten by fifteen metres, ranged from six to ten million rupiah. The price of land increases based on the number of good quality coconut trees growing, and decreases based on its proximity to urban areas. Yainuelo’s greater distance from the capital of Central Maluku, compared to Aira, is demonstrated in comparatively lower land values (one kinta of land in Yainuelo cost 2.5–3 million rupiah, lower than Aira).

5 For example, Raja Gorom in East Seram Island prohibited outsiders from cultivating long-age crops (Ellen Citation2003).

6 Pseudonyms are used throughout this article.

References

- Adam, Jeroen. 2010. “Communal Violence, Forced Migration and Social Change on the Island of Ambon, Indonesia.” PhD diss., Ghent University.

- Andaya, Leonard Y. 1995. “The Bugis Makassar Diasporas.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 68 (1): 119–138.

- Bertrand, Jacques. 1995. “Compliance, Resistance, and Trust: Peasants and the State in Indonesia.” PhD diss., Princeton University.

- Bertrand, Jacques. 2002. “Legacies of the Authoritarian Past: Religious Violence in Indonesia's Moluccan Islands.” Pacific Affairs 75 (1): 57–85.

- Brouwer, A. 1998. “From Abundance to Scarcity. Sago, Crippled Modernization and Curtailed Coping in an Ambonese Village.” In Old World Places, New World Problems. Exploring Issues of Resource Management in Eastern Indonesia, edited by S. Pannel, and F. von Benda-Beckmann, 336–387. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Carnegie, Michelle. 2010. “Living with Difference in Rural Indonesia: What Can be Learned for National and Regional Political Agendas?” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 41 (3): 449–481.

- Cooley, Frank L. 1969. “Village Government in the Central Moluccas.” Indonesia 7: 139–163.

- Donkin, R. A. 2003. Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices up to the Arrival of Europeans. Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society.

- Effendi, Ziwar. 1987. Hukum Adat Ambon-Lease. Jakarta: Pradnya Paramita.

- Ellen, Roy. 1978. Nuaulu Settlement and Ecology. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Ellen, Roy. 1997. “The Human Consequences of Deforestation in the Moluccas.” Civilisations 44 (1–2): 176–193.

- Ellen, Roy. 2003. On the Edge of the Banda Zone: Past and Present in the Social Organization of a Moluccan Trading Network. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Ellen, Roy Frank, and Hermien L. Soselisa. 2012. “A Comparative Study of the Socio-Ecological Concomitants of Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz) Diversity, Local Knowledge and Management in Eastern Indonesia.” Ethnobotany Research and Applications 10 (March): 015–035. https://ethnobotanyjournal.org/index.php/era/article/view/640.

- Frost, Nicola. 2004. “Adat di Maluku: nilai baru atau eksklusivisme lama?” Antropologi Indonesia: Majalah Antropologi Sosial Dan Budaya Indonesia 28 (74): 1–11.

- Grimes, Barbara Dix. 2006. “Mapping Buru: The Politics of Territory and Settlement on an Eastern Indonesian Island.” In Sharing the Earth, Dividing the Land, edited by Thomas Reuter, 135–155. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Hospes, Otto. 1996. “People That Count: Changing Savings and Credit Practices in Ambon, Indonesia.” PhD diss., Wageningen Agricultural University.

- Kadir, Hatib Abdul. 2013. “Muslim-Christian Polarization in the Post Conflict Society-Ambon.” Jurnal Universitas Paramadina 10 (3): 824–838.

- Kadir, Hatib Abdul. 2017. “Gifts, Belonging, and Emerging Realities Among ‘Other Moluccans’ During the Aftermath of Sectarian Conflict.” PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz.

- Kadir, Hatib Abdul. 2018. “History of the Moluccan's Cloves as a Global Commodity.” Kawalu: Journal of Local Culture 5 (1): 63.

- Kadir, Hatib Abdul. 2019. “Hierarchical Reciprocities and Tensions Between Migrants and Native Moluccas Post-Reformation.” Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights 3 (2): 344–359.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2000. “Articulating Indigenous Identity in Indonesia: Resource Politics and the Tribal Slot.” Comparative Studies in Society and History: An International Quarterly 42 (1): 149–179.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2014. Land's End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Matinahoru, J. M. 2013. “Studi Perladangan Berpindah dari Suku Wemale di Kecamatan Inamosol, Kabupaten Seram Bagian Barat.” Agrologia 2 (2): 86–94.

- Palmer, Blair. 2004. “Migrasi dan identitas: perantau Buton yang kembali ke Buton setelah konflik Maluku 1999–2002.” Antropologi Indonesia: Majalah Antropologi Sosial Dan Budaya Indonesia 28 (74): 94–109.

- Reid, Anthony. 1995. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Robertson, A. F. 1980. “On Sharecropping.” Man 15 (3): 411–429.

- Rudyansjah, Tony, and Zulkarnain Tihurua. 2019. “Money and Masohi: An Anthropological Review of Copra Commodity Management.” Wacana: Journal of the Humanities of Indonesia 20 (3): 507–524.

- Sholeh, Badrus. 2003. “Ethno-religious Conflict and Reconciliation: Dynamics of Muslim and Christian Relationships in Ambon.” MA diss., Australian National University.

- Sitorus, Oloan. 2019. “Kondisi aktual penguasaan tanah ulayat di Maluku: Telaah terhadap gagasan pendaftaran tanahnya.” Bhumi, Jurnal Agraria dan Pertanahan 5 (2): 222–229.

- Sutherland, Heather. 2021. Seaways and Gatekeepers: Trade and State in the Eastern Archipelagos of Southeast Asia, c.1600–c.1906. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Tihurua, Zulkarnain. 2018. “Land Certification a Ticking Time Bomb.” Jakarta Post, September 13. https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2018/09/13/land-certification-a-ticking-time-bomb.html.

- Tihurua, Zulkarnain. 2019. “Lanskap Budaya Komoditas Kopra. Tinjauan Antropologis Terhadap Dinamika Komoditas Kopra di Yainuelo.” BA diss., Indonesia University.

- von Benda-Beckmann, Franz. 1991. “Pak Dusa’s Law: Thoughts on Legal Knowledge and Power.” In Ethnologie im Widerstreit: Kontroversen über Macht, Geschäft, Geschlecht in Fremden Kulturen. Festschrift für Lorenz G. Löffler, edited by E. Berg, J. Lauth, and A. Wimmer, 215–227. München: Trickster Verlag.

- von Benda-Beckmann, F., and K. von Benda-Beckmann. 1994. “Property, Politics and Conflict: Ambon and Minangkabau Compared.” Law and Society Review 28: 589–607.

- von Benda-Beckmann, F., and K. von Benda-Beckmann. 1999. “A Functional Analysis of Property Rights, with Special Reference to Indonesia.” In Property Rights and Economic Development: Land and Natural Resources in Southeast Asia and Oceania, edited by T. van Meijl, and F. von Benda-Beckmann, 15–57. London: Kegan Paul International.

- von Benda-Beckmann, Franz, and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann. 2007. Social Security Between Past and Future: Ambonese Networks of Care and Support. Berlin: Lit.

- Weiner, Annette. 1992. Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping While Giving. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Winn, Phillip. 2008. “Butonese in the Banda Islands: Departure, Mobility, and Identification.” In Horizons of Home: Nation, Gender and Migrancy in Island Southeast Asia, edited by P. Graham, 85–100. Melbourne: Monash University Publishing.