Abstract

This paper addresses what Akhil Gupta calls the ‘temporality of infrastructure’ or ‘infrastructure as an open-ended process’ by examining changes in the spatiotemporal configuration of a telecommunications network in Papua New Guinea (PNG). It describes the arrival of Digicel Group Ltd, a privately owned foreign company, in response to the PNG government's 2005 decision to allow competition in the market for mobile communications, and it charts the ensuing rapid uptake of mobile phones by users who previously had no access to telecommunications services. It demonstrates how between the years 2007 and 2017, different forms and degrees of connectivity were produced through shifts in network infrastructure: from 2G to 4G LTE technologies; from basic handsets to smartphones; and from the sale of prepaid vouchers (‘flex cards’) by airtime resellers to purchases of airtime online and at ATMs by mobile users. These shifts widened a digital divide between urban and rural areas that deferred if not denied the promise of national coevalness regardless of where one resides. That is, not only infrastructural time but also ‘infrastructural citizenship’, to use Charlotte Lemanski's term, came to be imagined, represented, and lived as a function of one's location in a network of uneven connections.

Introduction

In an insightful article that addresses issues I take up here, anthropologist Katrien Pype (Citation2021) offers a telling story of digital disconnection. Junior, one of Pype's friends and research participants in Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo), had gone silent. Junior usually communicated with Pype on his Android mobile phone through a WhatsApp account. It turned out that Junior was unable to contact Pype because every time he tried to open his WhatsApp account, a small screen popped up and required Junior to update his application. Junior did not have the means to pay for the update and therefore ‘had no other choice than being offline for a while until he had collected the money’ (Pype Citation2021, 1207). Junior's inability to update, and thus his involuntary disconnection, left him out of sync, unable ‘to set to the right day’ (la mise à jour). It was as if Junior had been left behind, stranded at some earlier developmental stage with and by an antiquated technology.

A similar sense of disconnection is commonly expressed spatially in Papua New Guinea (PNG) through the Tok Pisin idiom of las ples (‘last place’). There is, in fact, a vigorous competition for last place all across the country, as different communities profess their marginality and complain about their exclusion from the promises of modernity and development. Don Kulick's (Citation1992) poignant account suggests that it is perhaps the Gapun villagers living in the sago swamps of the lower Sepik River who are the dubious winners of this competition. Consider how one old Gapun man, Kruni, contrasted his existence with that of White people in ‘the countries’—places like Japan, America, and Germany:

We’re the last country. And the way of life, too. In the countries, it's good. There's no work. Like what we do here—carry heavy things around on our shoulders, walk through the jungle like pigs. No. You all just sit, drive around in cars. . . Houses. You all live in good houses. They have rooms in them, toilets. But us here, no. We haven't come up a little bit. God papa hasn't changed us yet. We’re still inside the Big Darkness. We still live in the same way our fathers from a long time ago lived. Just like wild pigs. (Kulick Citation1992, 55)

Wilk contrasts colonial time with ‘TV time’. In the case that Wilk presents from Belize, the former colony British Honduras, watching television via satellite networks enabled a new in-sync experience: ‘Watching the [Los Angeles] Lakers [basketball] playoff on a TV in Belize City, there is an immediacy of experience, an emotional involvement in the present on an equal basis with viewers in Los Angeles and New York’ (Wilk Citation1994, 99). TV time thus makes it difficult to reckon the difference between Belize and the US in terms of asynchronicity (if not, however, in terms of distance and culture).

The arrival of satellite television in Belize can be instructively compared with the arrival of Digicel Group Ltd, a privately owned foreign company, in response to the PNG government's 2005 decision to open the market for mobile communications to competition (see Foster and Horst Citation2018). Digicel pledged to make telecommunications available to populations, rural as well as urban, that never before could afford or access phone service, let alone mobile phone service. In the immediate years after Digicel's arrival, differences between rural and urban residents, and between more affluent and less affluent citizens, were attenuated although certainly not eliminated. For the first time, some villagers in remote areas could communicate in real time with their relatives in the city, all thanks to Digicel's substantial investment in a sprawling network of 2G cell towers and its heavy subsidy of basic Nokia and Motorola handsets.

As Paula Uimonen (Citation2015, 37) says with regard to Africa: ‘In the absence of other forms of modern infrastructure (e.g. educational institutes, health care facilities, roads and transport systems), mobile infrastructure offer at least a semblance of accomplishment, offering citizens a sense of progress and inclusion’ (see also Fredericks and Diouf Citation2014; Wafer Citation2012). Put differently, Digicel revived the promise of coevalness (Fabian Citation1983) implicit in Benedict Anderson’s (Citation1991) well known formulation of the nation as an imagined community. Almost all citizens could hope to experience national simultaneity, the empty homogenous time through which the nation calendrically moves. Put differently, the PNG state had at last delivered the desirable kind of modern and inclusive ‘infrastructural citizenship’ (Lemanski Citation2018) that formal Independence in 1975 had anticipated—albeit by relinquishing its monopoly on telecommunications and creating a competitive market.

Infrastructural citizenship, a term and idea developed in the writings of urban geographer Charlotte Lemanski (e.g. Citation2018, Citation2022), refers to how everyday access to and use of infrastructure reflects and enacts one's status as a citizen. As Lemanski (Citation2022, 936) puts it, ‘. . . the state is materially and visibly represented through everyday (in)access to public infrastructure, while the state imagines and plans for citizens primarily as infrastructure claimants, consumers and complainers’. It is often the case, for example, that people with restricted citizenship rights (immigrants and slum-dwellers) encounter limited access to public infrastructure and sometimes use infrastructure as a tool of protest, as in blocking roads or bypassing metering devices. Infrastructure thus materialises the relationship between states and marginalised citizens in the mundane form of frequent power failures, gaping potholes, and unclean water. By contrast, the arrival of Digicel materialised a relationship between the PNG state and an increasing number of its citizens, in which both parties lived up to their moral obligations to each other.

Fast forward: Ten years later in 2017, the national unity that Digicel had gone a long way towards realising was giving way to varying forms and degrees of connectivity. The promise of coevalness was undermined by infrastructural changes that left all people in some places and some people in all places out of sync, involuntarily disconnected from the synchronicity promised by digital technology in general and Digicel in particular. Whereas for a brief moment it seemed like a one-to-one correspondence would emerge between physical space and Hertzian space, the two topographies were becoming disjoined and distinct from each other (see Meese, Wilken, and Chan Mow Citation2019). In other words, infrastructural citizenship with its attendant claim to national belonging was becoming once again differentiated and exclusive.

In this article, I aim to demonstrate how between the years 2007 and 2017, different forms and degrees of connectivity were produced through related shifts in media infrastructure: from 2G to 4G LTE technologies; from basic handsets to smartphones; and from the sale of prepaid scratch-off vouchers (‘flex cards’) by airtime resellers to purchases of data online and at ATMs by mobile users. These shifts—signs and sources of media convergence—coincided with Digicel's evolution from a pure mobile telecommunications company to a ‘total communications and entertainment provider’ (Digicel Group Ltd Citation2015). These shifts also entrenched a digital divide between urban and rural areas (see Curry, Dumu, and Koczberski Citation2016) that deferred if not denied the dream of national coevalness regardless of where one resides (Fabian Citation1983). That is, not only infrastructural time but also infrastructural citizenship came to be imagined, represented and lived as a function of one's location inside or outside of a network of uneven connections. Not all citizens were treated equally. For people living in PNG's last places, this condition entails a kind of perpetual ‘suspension’, in which the ‘ever-present gap between the start and completion of infrastructure projects’ is never closed (Gupta Citation2015). Instead, people occupy ‘the suspension between what was promised and what will actually be delivered’ (Gupta Citation2018, 70). Such a state of suspension entails an allochronism that, I suggest, prompts a variety of efforts by an assortment of different actors to get in sync.

Digicel: Arrival and Rollout

Digicel did not introduce mobile phone service to PNG. It had been available through Pacific Mobile Communication Company Ltd (PMC), a subsidiary of Telikom PNG, the state-owned telecommunications provider. PMC launched GSM service—confusingly marketed at different times as BeMobile, ‘B’ Mobile, B-Mobile, or bmobile—in May 2003, but it remained concentrated in a few urban areas and came at high costs to subscribers for poor quality reception. (It is worth noting that PNG is the least urbanised country in the world.) Amanda Watson (Citation2011, 47) reports that ‘at one stage [PMC's] switch in Port Moresby had nearly reached its maximum designated technical capacity of only 50,000 subscribers and their computer system was becoming overloaded, with no additional users being taken on (Pacific Mobile Communications Company Ltd 2005)’. Paul Barker (Citationn.d.) reports that by mid-2007, on the eve of Digicel's operations in PNG, Telikom supplied only 65,000 fixed lines while PMC had 160,000 subscribers in a country of about 6.9 million people. Other estimates of mobile phone subscriptions circa 2006 are lower at 130,000–140,000 (Duncan Citation2013); 100,000 (Cave Citation2012); or even 60,000 (Suwamaru Citation2015).

Many Papua New Guineans more than ten years later bitterly remembered PMC's service as restricted to ‘big shots’ only (see Martin Citation2013). The start-up package that included a SIM card and 100 min of airtime cost PGK125 (about USD44 in 2007), an amount far beyond the reach of most Papua New Guineans. Mobile phones were, in effect, potent and portable symbols of wealth disparity and urban elites, not to mention plain evidence of an incompetent and uncaring state incapable of bringing development to the people and meeting its moral obligations to all citizens.

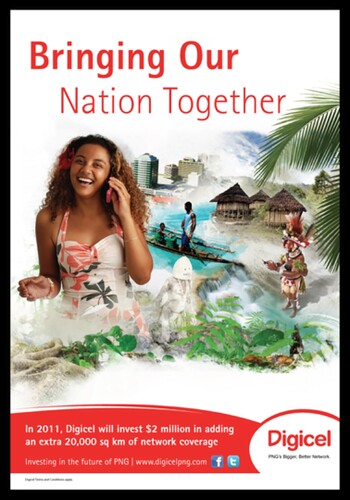

The arrival of Digicel disrupted the status quo. A sense of world-historical change is captured in the company's energetic PNG launch video (Digicel PNG Citation2014) and in the bold front-page declaration circulated in newspapers at the commencement of operations in July 2007, when Digicel's licence was unsuccessfully challenged by Telikom: Digicel Is Here to Stay! Although Digicel began operating its first retail stores in the main urban centres of Port Moresby and Lae, it had by the time of its launch built a network of towers that stretched into rural areas of PNG, where about 85 per cent of the population lives. It was, in other words, now possible for urban workers to call their village relatives without the latter having to find their way to town and wait on a long line for a public pay phone that might not very well work. Digicel was able to proclaim with all plausibility that its mission was to unite the nation, to realise the ideal of a territorially cohesive space, integrated by a modern telecommunications infrastructure (). That is, a foreign and privately owned company asserted itself in national popular terms that actually made good sense to many people.

Digicel advertised the progress it was making on its mission in two complementary ways, each of which conveys both the promise of coevalness and the gradual, inevitable fulfilment of this promise. First, Digicel issued full-page notices in PNG's two major newspapers whenever it had expanded its operations into one of the country's provincial centres. These ads announced and foreshadowed the inclusion of more and more national territory within the same temporal frame. That is, more and more Papua New Guineans were being put in sync with each other. This step-by-step progress implied a time when every town and village would be integrated within the Digicel network, when the physical and Hertzian space of the nation aligned with each other perfectly ().

Second, Digicel issued maps that offered a graphic depiction of how more and more territory was disappearing under red swatches indicating network coverage. Updated coverage maps communicated the same progress as that signalled in the newspaper ads but by different visual means. That is, the national silhouette of PNG was becoming progressively monochromatic, like one of the mosaic tiles that comprise political maps in which each nation is a uniform colour distinct from that of bordering nations (see Anderson Citation1991, 170 ff.). These maps also provided a handy way to make comparisons between Digicel and its competitor, bmobile, and thereby confirm Digicel's marketing boast to be the ‘bigger and better network’.Footnote1 These representations effectively displayed what in other contexts is sometimes called the ‘penetration rate’ of mobile phones—the number of users per 100 people in a given population. What is important to note about penetration rates is that they point towards the future. From a corporate perspective, they conjure up continued growth and increased revenues. This peculiar way of imagining national populations characterised, for example, the expansion of The Coca-Cola Company in the Global South during the 1990s. A company executive could thus justify expanding into Asian markets by observing that ‘While the per capita consumption of Indonesia . . . is a far cry from Australia, it has a 7 per cent growth in domestic product and, with a population of 180 million, that represents excellent opportunities during the next few years’ (quoted in Foster Citation2008, 103).

In the beginning, Digicel's project of putting people in sync with each other was primarily a national project. Subsequently, it became an international one. Network connectivity offered the opportunity to be in sync not only with everyone in PNG but also with diasporic friends and relatives living abroad—in ‘the countries’ to which Kruni unfavourably compared his homeland. Friends and family overseas were encouraged to ‘send top up home’ and become eligible to win prizes (see Foster Citation2018, 114). Just like Belizeans watching the Los Angeles Lakers, resident Papua New Guineans could then share experiences in real time with folks in Australia or the United States. This promise of international coevalness is comparable to that offered to Papua New Guineans by Christianity: membership in a transnational or global community that includes people living in modern places—Kruni's ‘countries’—who do not suffer the injuries of colonial time (see Robbins Citation1998).

In short, the years immediately following Digicel's arrival were a period of increasing digital equality and expanding infrastructural citizenship. Inclusion in the national space–time was extended to more people than ever before, and the possibility of a future in which just about everyone was included seemed thinkable. It was during this period that Digicel enjoyed almost universal affection among Papua New Guineans.

By contrast, Telikom—despite its efforts to control the public narrative by remarketing itself as the nationally owned network operator—attracted almost universal disdain.Footnote2 Telikom represented itself in ads that were part of a concerted ‘rebranding’ as the true national carrier, using the tagline ‘Always Here!’ to remind folks that the company had always been there to serve the people. Hence the message of one full-page ad, appropriately placed on Independence Day weekend in September 2007, that pictured two Telikom workers surveying the mountain valley below from atop a dizzyingly high tower: ‘Through some challenging situations, we've Built a Network for the Last 52 Years, and We'll Always Be Here for You’. The rebranding exercise acknowledged past shortcomings such as slowness in repairing faulty landlines, regarding which one company representative commented: ‘We say thank you for your patience and continued loyalty to Telikom’. As then CEO Peter Loko put it, he wished consumers to see Telikom ‘for what we are today, not what we might have looked like earlier’ (The National Citation2007).

Digicel's ability to deliver modernity to the masses ultimately trumped Telikom's appeal to economic nationalism. It was indeed Digicel, not Telikom, that was uniting the nation. Within two years, Telikom was compelled to sell half its shares in Bmobile in what proved to be a bootless effort to improve the company's competitiveness by bringing in private investors.Footnote3

Uneven Digital Times and Topographies: 3G and Smartphones

Digicel's offer of simultaneity was never equally available to everyone with a working mobile phone and network coverage. The service, after all, is not free. And it must also be acknowledged how temporal discrimination was always baked into the company's service charges. There is a significant difference, for instance, between the rates charged for calls during peak hours and off-peak calls. Such a disparity could make a significant difference for how people feel connected or in sync with each other. Consider the comments of one woman who felt slighted by her boyfriend making calls after 11PM, when Digicel users could take advantage of a late-night promotion that provided 100 free minutes of talk time (see Foster Citation2018). This woman complained that her boyfriend was in effect telling her that she was not worth the price of a call for which the boyfriend had to spend prepaid airtime. Pype (Citation2021), who reports a similar case from Kinshasa, has observed that the peak/off peak distinction divides the world of mobile users into those who operate openly by day and those who, like netherworld denizens, operate under cover of darkness.

The space–time of Digicel coverage in many rural areas and some urban locations was similarly heterogeneous. Reception might be available only during limited times of day, such as dusk and dawn. Mobile users were often required to seek out certain spots where reception was possible, climbing hills or trees to find a signal (see Lipset Citation2018). Such tenuous connectivity, which generates an array of disparate and unshared spatiotemporal configurations, is erased by the seductive smoothness of coverage maps. Right from the start, then, there were multiple gradations in network connectivity (see Warschauer Citation2003). Digital divides appeared among users with connectivity as well as between the connected and unconnected.

Digital divides that sorted mobile users into unequal categories began to proliferate after 2011, when Digicel began to make 3G mobile broadband services more widely available. Steep drops in the price of new entry-level smartphones as well as a robust market for previously owned (often pickpocketed) handsets helped to increase access to wireless Internet, especially in urban areas where access to 3G towers was more available and reliable. In July 2014, Digicel was offering an Alcatel Onetouch Pixi (equipped with 3G touchscreen, 512MB internal memory, 256 MB RAM, and a microSD slot) for 149 kina (about USD 48). This smartphone was subsidised by and, of course, locked to the Digicel network. By mid-2016, a Digicel official estimated that the company served 700,000–800,000 smartphone subscribers (pers. comm. May 2016). Catherine Highet et al. (Citation2019) put the number of smartphones in 2018 lower at 600,000, with 22 per cent of connections by smartphone and an 11.75 per cent market penetration rate for mobile Internet unique subscribers.

The spread of smartphones is indicated by the 2022 statistics found on the website of ‘We Are Social’, a global agency specialising in social media marketing (https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-papua-new-guinea). The agency estimated some 3.32 million ‘mobile connections’ (not unique subscribers) or 36 per cent of the estimated population of 9.21 million. 55.2 percent of these connections were broadband connections. Of an estimated 1.03 million active social media users (11.2 per cent of the population), 96 per cent accessed platforms such as Facebook—by far the most popular in PNG—via mobile phones. But the distribution of smartphones indicated here is highly uneven: ‘Internet usage is skewed towards urban centres, with almost 70 per cent of internet users residing in the cities of Port Moresby and Lae’ (Highet et al. Citation2019, 24). These users, moreover, are more than likely to be men under the age of 34.

The spread of smartphones entrained other new distinctions, including an invidious comparison between basic or simple handsets and smartphones. That is, the simple phone (or ‘button phone’) began to materialise a particular kind of person, namely, a simple person—one who poked at buttons rather than swiped screens. These simple users were stereotypically imagined as older, rural, and non-literate—women more often than men; they used the phone exclusively for voice calls, recognising only the green and red functions (answer and disconnect) on the phone. The subjective force of this distinction can be sensed in the autobiographical essay of a woman named Laripape, whose parents favoured their church mates and younger son with gifts and money but denied Laripape's requests for support with her studies at the University of Papua New Guinea: ‘I asked for a phone and was bought a button phone with no Internet browser for research while my little brother was given touch screen phones one after another’ (The National Citation2019). Laripape's button phone sensuously signified her sense of exclusion from her own family.

Laripape and other button phone users had become signs of another time. One can get a better sense of how the stalwart basic handsets that once symbolised a democratic modernity came to represent a prior stage of evolution from a Facebook post that appeared during the pandemic on a Fijian colleague's page: ‘Imagine if this #Lockdown happened 15 years ago, stuck at home with a Nokia 3310 and a plan for 100 sms and 300 minutes of calls!’ Ten years after Digicel's arrival, many university students with whom I spoke would similarly, although positively, associate simple phones with the past, recalling their first basic handsets—the Konka C625 and the ZTE Coral 100—with a dash of nostalgia for a time of childhood innocence.

* * *

My colleague's Facebook post indicates a second new distinction that began to emerge after 2011, namely, that between airtime for phone calls and text messaging, and data for Internet access. Mobile users with 3G-enabled handsets purchased data credits to browse the web or post photos to Facebook, to which Papua New Guineans took ‘with gusto’ (Logan and Suwamaru Citation2017, 289). These users, moreover, began to employ the Internet for making voice calls and sending messages and photos via WhatsApp and Viber, thus reducing their use of Digicel's voice and short message services (SMS). From the company's point of view, this transition from telephony to data was a fundamental change in the source of its revenues but not necessarily one that threatened the bottom line. Watson (Citation2017a) asked Gary Seddon, a senior manager at Digicel, about the threat that Voice over Internet Protocol (VOIP) posed to the company's income from voice calls and text messages. Seddon replied:

It encourages data consumption, so you will see greater data growth. It is a growing medium of communication in PNG; one that we embrace. But let's not forget that conventional voice and SMS services are still incredibly important in PNG. The populations that are outside of 3G and 4G zones still rely heavily on our 2G based services. There remains a lot of the country to appropriately cover, despite Digicel's considerable investment, presently exceeding PGK2.5billion.

In anticipation of the Pacific Games, Digicel announced a USD3 million upgrade of network capacity in Port Moresby, and a separate USD13.4 million investment in 56 LTE sites also in Port Moresby. The company added new towers and increased the capacity of existing towers in the vicinity of stadiums and other event venues. CEO Maurice McCarthy exclaimed ‘The beauty of this investment on the network is that it will benefit the citizens of Port Moresby long after the games are over with faster more reliable internet speed and consistent coverage’ (Post-Courier Citation2015b). McCarthy further noted that Digicel's investment would allow Port Moresby to host ‘many more large scale events which have high traffic periods’ and which in the past have placed ‘enormous pressure on the network's capacity’. Proper infrastructural citizenship was thus a material reality—if only for ‘the citizens of Port Moresby’. Much like the annual Independence Day celebrations that the company sponsors, the Pacific Games offered Digicel a platform on which to represent itself as attentive to the needs of the nation, including the infrastructure necessary for development.

By contrast, 2G towers in rural areas were upgraded slowly and selectively. Digicel CEO John Mangos told me in 2015 that rural towers were upgraded depending on use (pers. comm.). If a tower were mainly being used for voice calls and text messages, then it was not upgraded. Highet et al. (Citation2019, 22) report that average monthly revenue per user (ARPU) in rural and remote PNG is between USD.60 and USD.90, which ‘makes the business case for tower deployments and operations complex without external subsidies’. And even if a tower were upgraded, rural residents would have to contend with the demands of recharging their power-hungry smartphone batteries with almost no access to the electrical grid. Ryan Murdock (Citation2022) notes that between 10 and 15 per cent of PNG's population has access to on-grid electricity, although 60 per cent of the population ‘is connected if off-grid solar products are considered’.

In 2018, 2G services were still common in rural areas, where the bulk of PNG's population lives; some of these towers were originally made possible by the universal services fund created by a tax on the gross revenues of Digicel and other mobile network operators. 2G connections accounted for 55.5 per cent of the market in PNG, with 3G and 4G connections each accounting for about 25 per cent (Oxford Business Group Citation2019). Digicel reportedly aimed to cover 80 per cent of PNG's population with 3G by 2020 as well as to upgrade 173 towers from 3G to 4G. bmobile, which competes respectably with Digicel in urban areas, aimed to command 20 per cent of the 4G market by 2019, a goal made more possible by absorbing Telikom's 4G services and some 400 base stations (Oxford Business Group Citation2019), in which Telikom had invested when migrating its short-lived and unsuccessful CDMA Citifon service (2011–2016). (Telikom exited the mobile market in 2019, leaving Digicel and bmobile as the only two competitors.) Given the disruptions caused by COVID-19, it is unclear if these goals have been achieved.

* * *

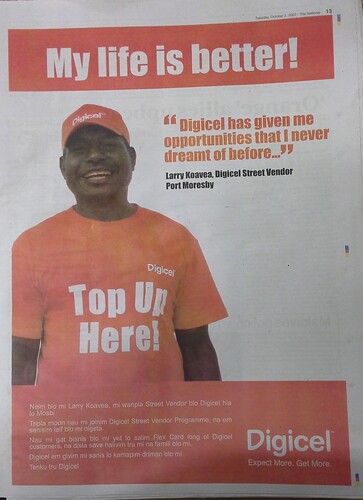

The transition to data also poses challenges to the human infrastructure of telecommunications networks in PNG. That is, the spread of smartphones and increase in Internet use threatens the livelihoods of street vendors who sell prepaid scratch-off vouchers (‘flex cards’) (see Bai-Magea Citation2019) (). These street vendors were instrumental in Digicel's original rollout in PNG, making airtime credit widely available for purchase at all hours in urban settings. Digicel featured its street vendor programme in its early advertising, suggesting that a person could realise their dreams by becoming part of the company's infrastructural assemblage ():

My name is Larry Koavea. I am a Digicel Street Vendor here in Port Moresby.

Three months ago I joined the Digicel Street Vendor Programme, and it completely changed my life.

Now I have my own business selling Flex Cards to Digicel customers, and this has truly helped me and my family.

Digicel has given me the chance to realize my dreams.

Thanks a lot, Digicel. [Author's translation from Tok Pisin]

In addition, new forms of ‘self-care’—quite different from the kind of personal care that street vendors afford their regular customers (see Thomas et al. Citation2018)—began to be promoted. In January 2017, Digicel launched the My Digicel App for smartphone users, promising customers an efficient tool for ‘managing their Digicel life’ (The National Citation2017). Several months later, the company introduced a menu that would allow customers, including users of basic handsets, to assist themselves with queries relating to data and top up, among other things. (Dial *123#. 24/7. Free. A list of frequently asked questions appears on the phone's screen.) The company invested in efforts to give ‘effective tools’ to customers for self-care, that is, to encourage customers to use their apps instead of speaking with customer care agents or visiting Digicel stores (see SWRVE Citation2020). The transition to online credit purchases and self-care thus threaten to eliminate a form of livelihood that Digicel once promoted as a sign of its commitment to making the dreams of ordinary citizens come true. That is, the infrastructure that once promised inclusive citizenship has become a source of exclusion.

In sum, the transition from telephony to data advantaged urban residents over rural residents, and further expanded a digital divide that Digicel's arrival in PNG was originally hailed for closing. What has taken shape since the introduction of mobile broadband service to PNG in 2011 is an uneven mediascape in which rural areas, provincial towns, and major cities are differentiated or zoned by their access to 2G, 3G, and 4G LTE, respectively. The initial telecommunications democracy that Digicel began to establish in 2007, in which the same 2G towers served all citizens equally, has yielded to a more hierarchical arrangement in which one's location in town or in the bush determines the quality of one's infrastructural citizenship.

Overcoming Allochronism

Coverage maps and penetration rates figure in how mobile network operators (MNOs) represent themselves to their stakeholders. For example, bmobile, the PNG state-owned MNO, includes a coverage map on its website with the hopeful proviso that the map ‘may vary from time to time as the coverage expands around PNG’.Footnote5 Similarly, Digicel included penetration rates for all of its markets in the information filed as part of an aborted initial public offering of stock (Digicel Group Ltd Citation2015). Penetration rates below 100 per cent signal to investors the potential for expanding markets and growing revenues. Hence the comments of Telstra International CEO Oliver Camplin-Warner on his company's acquisition of Digicel Pacific in 2022 (discussed below): ‘When I look at the growth opportunities moving forward, one of the key ones … is around mobile penetration. When we look at mobile penetration in PNG today, it sits around the 30% mark. So, we see a significant opportunity to leverage the extensive network footprint that they [Digicel] have rolled out’ (Business Advantage PNG Citation2021c).

By the same token, low penetration rates are equally read as indicators of a disturbing lack of development. For example, an intelligence report issued by the Groupe Speciale Mobile Association (GSMA) interprets PNG's penetration rate as evidence of a ‘connectivity gap’: ‘with a subscriber penetration rate of 30%, [PNG] is home to the majority of the unconnected population across the [Pacific Islands] region’ (GSMA Citation2019, 3). That is, rates unavoidably imply their corollary: if 30 per cent of the population has a mobile subscription, then 70 per cent does not. Rates, moreover, can move in two directions: an estimated 1.4 million SIM cards were deactivated when PNG government-mandated registration laws went into effect (Bryden Citation2021, 33). Similarly, coverage maps identify places that are presently unconnected, where people live in the time of suspension (Gupta Citation2015). Maps and rates thus indicate allochronism—the condition of being out of sync with the rest of the national community and perforce the rest of the modern world; they communicate, visually and numerically, the inequities of infrastructural citizenship.

The time of suspension, Gupta (Citation2018, 72) suggests, is one of temporal openness to different outcomes; ‘completion’ of the infrastructure is only one possibility and the future is unknowable. It is not surprising, then, to learn that a cursory survey of the digital landscape in PNG reveals a range of creative attempts to overcome allochronism and to pull the future into the present. One of these attempts notably recalls the cargo cult activities for which Melanesia is famous. Borut Telban and Daniela Vávrová (Citation2014) have described how Karawari people in East Sepik Province use mobile phones to make contact with deceased relatives. Such contact, if made, would enable the deceased to funnel material resources and powerful knowledge to the living and thus ensure a life of prosperity. Hence the strong desire of Karawari for Digicel to extend network coverage to their area by building a cell tower nearby—a desire that conveys clearly the way in which infrastructures materialise anticipations of a better future, promising new means to realise old hopes and dreams.

More prosaic attempts to extend coverage have been undertaken by private groups with unusual resources and infrastructural needs. In Lihir Island, for example, site of one of the world's largest gold mines, the landowner-owned company Anitua was able to secure a low-latency satellite terminal to deliver connectivity across the island (Business Advantage PNG Citation2021a). In this sense Anitua acted no differently than Digicel itself, which was compelled to invest in satellite technology in order to sidestep the monopoly on international undersea fibre optic cables exercised first by the state-owned company Telikom and subsequently by the state-owned entity DataCo. Such workarounds are also common at sites of development projects scattered across PNG (Beer and Schwoerer Citation2022), thus adding to the unevenness of the mediascape in which an oasis of high-speed connectivity can exist amidst stretches of territory not or ‘not yet’ covered by the Digicel network, depending on one's perspective.Footnote6

There are also public–private solutions to allochronism. Public–private partnerships are often touted as win–win arrangements for overcoming the problem of incomplete coverage. Public good and private interest are allegedly satisfied at the same time; the market delivers development to the people and profits to businesses. In PNG, the same not so invisible hand also generates political capital for members of parliament (MPs) who choose to make a deal through Service Improvement Programme (SIP) funds assigned by the national government to their districts. Newspaper reports periodically announce how an MP has contracted with Digicel to erect a tower in his (always his) district. The contract stipulates that Digicel covers half of the PGK 1 million cost while local MPs cover the other half. Photos feature the handing over of a cheque from the MP to a Digicel representative. The exchange enables the MP to redeem his campaign promise to bring development to the district—from Telefomin to Tagula—while at the same time subsidising the expansion of Digicel's network. In this way, the MP moves the hands of the ‘infrastructural clock’ (Gupta Citation2018) ahead, bringing his district out of last place, out of the past and into the present of modern infrastructural citizenship.

Finally, there are state-directed public initiatives to overcome allochronism, several of which have been undertaken as part of PNG's construction of a National Transmission Network (NTN). These initiatives include a major capital-intensive expansion of the fibre optic network connecting PNG internationally as well as connecting locations within PNG (Watson Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Such initiatives are in one sense typical of the old-fashioned developmental state that materialises its relationship to citizens through the provision of a modern infrastructure for water, electricity, transport, and so forth. But these particular initiatives notably entangle the PNG state in a dense web of geopolitical relations that condition, if not actually dictate, the state's capacity to distribute the benefits of infrastructural citizenship. For example, the Kumul Submarine Cable Network, completed in 2021 and linking 14 coastal provincial capitals within PNG to the national capital, has been funded through 85 per cent concessional loan financing from China's EXIM Bank.Footnote7 The Chinese company Huawei Marine was contracted for the project. However, the Coral Sea Cable System, completed in 2019 and linking Port Moresby (PNG) and Honiara (Solomon Islands) to Sydney (Australia), was majority funded by the Australian government in an explicit move to prevent Huawei Marine from undertaking the construction. The PNG state's attempt to overcome allochronism by upgrading its telecommunications network and putting its citizens in sync with each other is thus encompassed by larger political and economic interests.

The impact of geopolitical considerations on PNG's infrastructural capacity extends beyond the undersea fibre optic network. The concerns of the Australian government and its allies to limit the influence of China in the affairs of Pacific Islands countries have led to an infrastructural intervention of which the Coral Sea cable is only one example. As if in response to President Xi Jinping's state visit to PNG in 2018 (and PNG's involvement in China's Belt and Road Initiative), Australia along with the US, Japan, and Aotearoa New Zealand announced at the APEC Leaders’ Summit in Port Moresby their pledge to electrify PNG. The PNG Electrification Partnership aims to connect 70 per cent of the country's population to electricity by 2030 (Murdock Citation2022).

In 2022, Australia's infrastructural intervention continued when a subsidiary of Telstra Corporation Ltd completed its acquisition of Digicel's operations in the Pacific Islands (Digicel Pacific Ltd), including Digicel's largest Pacific market in PNG.Footnote8 Telstra, an Australian telecommunications company, contributed USD270 million to the deal, while the Australian government contributed USD1.33 billion. The Australian Financial Review, like many other commentators, noted that the Australian taxpayers were effectively assuming the risks involved in the purchase but observed that ‘this is because of fears that Digicel, which came under immense pressure when mobile phone traffic plunged in the tourist-dependent Pacific region at the height of the pandemic, may have been used to spy on Australia's neighbours if it fell into Beijing's hands’ (Baird and Tillett Citation2022). Other commentators similarly admitted that Telstra benefitted handsomely from the Australian government's huge subsidy but also wondered whether the deal would prove beneficial for the people of PNG (Howes Citation2021; Sora and Pryke Citation2021). Would Telstra operate its mobile network in PNG in such a way as to include more of the population by reducing prices and expanding access to rural areas? Would Telstra, in other words, afford full infrastructural citizenship to people excluded by changes in the telecommunications network since 2007 and thus restore the promise of national coevalness?

Conclusion: The Limits of Infrastructural Citizenship

The question of infrastructural citizenship bears consideration in light of the 2016 UN declaration that access to the Internet is a human right (Howell and West Citation2016). This declaration focused on governmental responsibility for ensuring that citizens are not denied access to the Internet as a means for free political expression; it did not, however, obligate governments to provide access to all citizens, especially the poorest. Despite efforts like that of the Mexican government to make good on its 2013 constitutional amendment defining access to the Internet as a human right (Barry Citation2020), approximately one third of the world's population in 2022 did not use the Internet (https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/2022/05/30/gcr-chapter-2/).

In PNG, according to the report of Highet et al. (Citation2019), access to the Internet and more generally to basic telecommunication services is highly uneven. In a population estimated by the report at 7.6 million in 2018, there are 2,525,643 unique subscribers—a market penetration rate of almost 30 per cent. Almost one million mobile Internet unique subscribers yield a market penetration rate of 11.75 percent. But the majority of connections by mobile technology were 2G (55.54 percent), with 3G connections at 22.91 percent and 4G connections at 21.55 percent. In other words, the majority of the population was not connected and the majority of the population that was connected was connected on 2G. These statistics, to repeat, reflect digital divides between urban and rural areas and between data users and voice users; 70 per cent of Internet users reside in the two major cities of Port Moresby and Lae (Highet et al. Citation2019, 24). The situation in 2018 thus recalled the situation in PNG before the arrival of Digicel, in which mobile phone use was restricted to city-dwelling big shots.

As Sarah Logan and Miranda Forsyth (Citation2018, 18) note, access to the Internet—largely via mobile phones—is crucial in countries such as PNG for development-related projects ‘in diverse areas such as maternal health, microfinance, and teacher education’. Access to and affordability of mobile phones is thus increasingly a prerequisite of full infrastructural citizenship. In PNG, however, it is the corporation and not the state whose actions bear upon the lived reality of infrastructural citizenship with regard to telecommunications: ‘In a country like PNG where the state does not have the capacity or the will to address infrastructure deficiencies, corporate interests have been able to insert themselves into citizens’ lives, for good or bad, introducing great change but also precariousness’ (Logan and Forsyth Citation2018, 20). Digicel, which controls around 90 per cent of the mobile market and owns its towers and terminals, rather than the PNG state, determines the terms and conditions on which infrastructural citizenship and the promise of national coevalness and being in sync are offered. And despite its non-trivial investment in corporate social responsibility through the activities of the Digicel Foundation in building schoolrooms and promoting gender equity (see Watson Citation2017b), the company remains a for-profit business. It is guided in the last instance by its commercial interests, which of course prompted the sale of Digicel Pacific Ltd to Telstra.

The acquisition of Digicel Pacific by Telstra reset the infrastructural clock. CEO Oliver Camplin-Warner affirmed Telstra's commitment to ‘building a strong and sustainable PNG’ by announcing that an additional new 115 towers would be constructed across the country in the next two years (Post-Courier Citation2022). He said that ‘This investment will mean continued improvements to 4G coverage, particularly in rural areas, which will bring with it opportunities to improve health, education, agricultural, commerce and cultural outcomes through the use of technology’. Colin Stone, CEO of Digicel PNG, noted that ‘Telstra has experience connecting regional and remote customers in challenging geographies across mountains, deserts, rainforests and coastlines’ (Post-Courier Citation2022). The telos of national coevalness was thus reinvoked and projected into a near future.

A hopeful future of greater connectivity has also been conjured by the launch in April 2022 of a credible potential competitor to Digicel in PNG, Digitec Communications Ltd trading as Vodafone PNG.Footnote9 CEO Pradeep Lal spoke the familiar language of projected growth: ‘According to GSMA reports, market penetration here is about 37 per cent of the population . . . Fiji is at 130 per cent mobile penetration—the same as Australia and New Zealand. Vanuatu and Samoa are at 100 per cent. PNG can very easily reach between 80 and 90 per cent mobile penetration in the next couple of years’ (Business Advantage PNG Citation2022). Like the Coca-Cola executive contemplating soft drink sales in Indonesia, Pradeep could interpret the absence of his product in the market as an opportunity rather than a liability.

Vodafone PNG's promotion of its rollout likewise recalled Digicel's 2007 strategy of tracking its ink-stain spread across the national territory. Vodafone PNG documented its premiere in Port Moresby and then its roadshow teams working in other parts of the country, although the company's promotion unfolded on Facebook rather than in printed newspapers. Social media, however, afforded users the opportunity to question the reality of a slowly growing area of even coverage implied in Vodafone PNG's promotions. For example, a message announcing a new tower and welcoming Vodafone's service to villages in the Aroma Coast area south of the national capital was recirculated with a complaint about blackspots in Vodafone's coverage of Port Moresby. Some commenters complained about slow Internet speeds or lack of reception in particular locations of Port Moresby, and one commenter joked that the Aroma villagers only need the tower for voice calls not data calls, thus deeming antiquated technology appropriate for rural areas. These comments together suggest that infrastructure is indeed an incomplete process, but not quite in the same way that Pradeep Lal, thinking of penetration rates, might have in mind.

These comments also suggest something about the infrastructure for mobile telecommunications, specifically, in PNG and elsewhere, namely, the frequency with which upgrading is required. Maintenance of trunk infrastructure is always necessary, of course, even if less visible than initial construction (Gupta Citation2018). But once sewer or electrical lines are laid, they usually do not require constant upgrading that threatens to exclude some users from access to full service. This threat looms not only in PNG but also in countries of the Global North such as the US, where the imminent shutdown of 3G wireless networks is anticipated to affect older and low-income Americans disproportionately (Zakrzewski Citation2021).

Constant upgrading puts infrastructural citizenship at risk in the same way that it compromised Junior's ability to communicate with Katrien Pype on WhatsApp. Moreover, telecommunication infrastructure is unlike other kinds of infrastructure inasmuch as it is difficult to hack. That is, it is one thing to jerry rig connections to water pipes or electrical lines (see, for example, von Schnitzler Citation2008), or to build makeshift housing or squat on state-owned land—all creative forms of popular protest against limitations on infrastructural citizenship. It is another thing to build one's own telecommunications network or even to erect a cell tower: Not impossible (see González Citation2020), but beyond the means of even the most insurgent of citizens. The infrastructural precariousness that Logan and Forsyth (Citation2018) note is therefore not only a function of corporate control but also a consequence of the material specificities of mobile telecommunication networks.

How can this precariousness be mitigated? Answers to this question highlight the formidable challenges that both ordinary Papua New Guineans and the PNG state face in negotiating the terms of infrastructural citizenship. On the one hand, Logan and Forsyth (Citation2018) call for a reduction in the influence of corporations like Digicel in determining the shape of telecommunications networks. They wish for more state regulation rather than less but worry that ‘Papua New Guineans are at the mercy of a corporation, over which their own government appears to have limited control’ (Logan and Forsyth Citation2018, 20). On the other hand, Denis O’Brien, Digicel Group Ltd's founder and chairman, calls on governments to lower the barriers to private investment, such as high spectrum license fees (ITU News Citation2015). In his role as a member of the UN Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, O’Brien strenuously championed the idea that access to the Internet is a human right. But O’Brien represented Digicel as a victim of other corporations in realising this goal. He demanded that over-the-top (OTT) players such as Google, Facebook, and Skype, who free ride on the rails laid down by mobile network operators, pay their fair share. It is difficult to decide whether Logan and Forsyth's vision of effective regulation by the PNG state or O’Brien's proposal for Google and Facebook to subsidise telecom companies is more fanciful.

Digicel has over the years of its operation in PNG benefited from low-cost loans offered by the World Bank's International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). But this type of loan is not available to governments, only to private sector-led projects. The latest state-led projects in PNG to upgrade the undersea fibre optic network have been made possible by dubious loans from China or—like the sale of Digicel Pacific Ltd to Telstra—by the largesse of Australian taxpayers. The price of financial aid to extend infrastructural citizenship to the people of Papua New Guinea has been to render the PNG state a pawn in a game of geopolitical chess.

* * *

As a counterpoint to Junior's involuntary disconnection described at the beginning of this article, I offer my own experience of privileged connectivity. On a recent trans-Pacific flight, I was amazed to discover that it was possible to use my smartphone while in flight to send messages by Wi-Fi on Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp for free. I was able to communicate with friends in Australia about my arrival while following the score of a football game through updates from my family in the United States. At more than 30,000 feet in the air and 500 miles per hour, I was in sync across multiple time zones and vast distances.

This spatiotemporal privilege is hardly common, despite the spread of smartphones to places well beyond Kruni's ‘countries’ (Miller et al. Citation2021), including some of the out of the way corners of Oceania. Consider in this regard, and by way of concluding, another counterpoint: the ambiguous example of rural Lau Lagoon villagers in Malaita, Solomon Islands. Lau villagers have embedded smartphones in their everyday lives despite lacking the financial means to make frequent calls and the capacity to access the Internet (Hobbis Citation2020)—an incapacity that materialises the state's broken promise of infrastructural citizenship (Ketterer Hobbis Citation2018). Their precarious connectivity notwithstanding, Lau villagers make full use of the multi-media and computational affordances of smartphones, watching videos, listening to music, playing games, doing calculations, and sharing photos (as well as using the flashlight). Lau villagers might thus take advantage of the subsidies that telco companies pay in the expectation that availability of inexpensive handsets will stimulate data usage. These offline uses of smartphones perhaps do amount to a so-called hack of the telecommunications infrastructure. But the hack is, in the end, a symptom of failed infrastructural citizenship: an appropriation of the network from which the villagers are, for the most part, disconnected.

Acknowledgements

Versions of this paper were presented at seminars hosted by the Institute of Society and Culture, Western Sydney University, and the Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. I thank the audiences at these presentations for their insights and questions. I also thank for their constructive comments and collegial support: Heather Horst, Amanda Watson, Malini Sur, David Lipset, and two anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 An image of Digicel's coverage map circa 2015 can be found in Foster and Horst (Citation2018).

2 In Fiji, however, Digicel was unable to devise an effective counter narrative to the state-owned company's claim to represent the nation (see Horst Citation2018).

3 In 2013, the PNG government acquired 85 per cent of the shares of Bemobile Ltd, which operates in both PNG and Solomon Islands. In 2014, Bemobile signed a non-equity partnership with Vodafone Group Plc, which lasted until 2019. In 2017, the PNG government announced the amalgamation of bmobile–Vodafone and Telikom along with DataCo., a state-owned entity created in 2014 to provide wholesale ICT services, under a new name, Kumul Telikom. In 2021, bmobile and Telikom merged as Telikom Ltd and Kumul Telikom Holdings Ltd was abolished.

4 I speculate that this development would have been further stimulated by COVID-19 lockdowns, as the previously mentioned Facebook post implies.

5 https://www.bmobile.com.pg/NetworkCoverage?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1, accessed 3 February 2023.

6 Cox et al. (Citation2022, 194) emphasise the geographical diversity or ‘patchwork quilt’ of economic activity in PNG, a useful modulation of a too stark binary contrast between urban and rural spaces.

7 This debt burden, estimated at USD270 million but possibly more (see Wall Citation2020), has impeded the efforts of DataCo to reduce wholesale Internet prices and fund further expansion of the NTN (see Business Advantage PNG Citation2021b).

8 Telstra planned to continue trading under the Digicel brand name (Business Advantage PNG Citation2021c).

9 Vodafone PNG (Digitec Communications Limited) is a subsidiary of Amalgamated Telecom Holdings (ATH) and Austel Investment Pty Limited. ATH has delegated the operation and management of the business to its subsidiary Vodafone Fiji Pte Limited, the largest mobile telecommunications provider in Fiji (https://vodafone.com.pg/about, accessed 14 September 2022).

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. ed. New York: Verso.

- Bai-Magea, Wendy. 2019. “Making a Living in Urban Papua New Guinea: Community, Creativity and the Provision of Mobile Phone Goods and Services in Goroka.” BA (Hons) thesis, University of Goroka.

- Baird, Lucas, and Andrew Tillett. 2022. “Telstra Complete 2.4b Digicel Deal.” Australian Financial Review, July 14. Accessed 10 November 2022. https://www.afr.com/companies/telecommunications/telstra-completes-2-4b-digicel-deal-20220714-p5b1h0.

- Barker, Paul. n.d. Reform in PNG – The Digicel Story. Port Moresby, PNG: Institute of National Affairs.

- Barry, Jack J. 2020. “COVID-19 Exposes Why Access to the Internet is a Human Right.” Open Global Rights, 26 May. Accessed 9 November 2022. https://www.openglobalrights.org/covid-19-exposes-why-access-to-internet-is-human-right/.

- Beer, Bettina, and Tobias Schwoerer. 2022. Capital and Inequality in Rural Papua New Guinea. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bryden, Natalie. 2021. Papua New Guinea: Telecoms, Mobile and Broadband – Statistics and Analyses. Sydney: Paul Budde Communication.

- Business Advantage PNG. 2021a. “Inside View: Satellite Technology a ‘Game Changer’ for Papua New Guinea.” May 24. Accessed 10 November 2022. https://www.businessadvantagepng.com/inside-view-satellite-technology-a-game-changer-for-papua-new-guinea/.

- Business Advantage PNG. 2021b. “Five Things We Learned from Our Papua New Guinea Telecommunications Update.” May 10. Accessed 10 November 2022. https://www.businessadvantagepng.com/five-things-we-learned-from-our-papua-new-guinea-telecommunications-update/.

- Business Advantage PNG. 2021c. “What are Telstra’s Plans for Digicel Pacific?” 26 0ctober. Accessed 1 December 2022. https://www.businessadvantagepng.com/what-are-telstras-plans-for-digicel-pacific/.

- Business Advantage PNG. 2022. “Vodafone’s K3 Billion Investment to Expand Papua New Guinea’s Telco Market.” April 27. Accessed 10 November 2022. https://www.businessadvantagepng.com/vodafones-k3-billion-investment-to-expand-papua-new-guineas-telco-market/.

- Cave, Danielle. 2012. Digital Islands: How the Pacific’s ICT Revolution is Transforming the Region. Sydney: Lowy Institute for International Policy.

- Cox, John, Grant W. Walton, Joshua Goa, and Dunstan Lawihin. 2022. “Uneven Development and Its Effects: Livelihoods and Urban and Rural Spaces in Papua New Guinea.” In Papua New Guinea: Government, Economy and Society, edited by Stephen Howes, and Leksmi N. Pillai, 193–222. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Curry, George N., Elizabeth Dumu, and Gina Koczberski. 2016. “Bridging the Digital Divide: Everyday Use of Mobile Phones Among Market Sellers in Papua New Guinea.” In Communicating, Networking: Interacting, edited by Margaret E. Robertson, 39–52. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45471-9.

- Digicel Group Limited. 2015. Form F-1, Registration Statement. Washington, DC: Securities and Exchange Commission.

- Digicel PNG. 2014. “Digicel PNG Launch Video 2007.” You Tube video, 3:48, March 21, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = dqNFTrMv5Q0.

- Fredericks, Rosalind, and Mamadou Diouf. 2014. “Introduction.” In The Arts of Citizenship in African Cities: Infrastructures and Spaces of Belonging, edited by Mamadou Diouf, and Rosalind Fredericks, 1–23. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Duncan, Ronald. 2013. “Telecommunications in Papua New Guinea.” In Priorities and Pathways in Service Reform: Part II—Political Economy Studies, edited by Christopher Findlay, 27–44. Hackensack, New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing.

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Foster, Robert J. 2008. Coca-Globalization: Following Soft Drinks from New York to New Guinea. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foster, Robert J. 2018. “Top-Up: The Moral Economy of Prepaid Mobile Phone Subscriptions.” In The Moral Economy of Mobile Phones: Pacific Islands Perspectives, edited by Robert J. Foster, and Heather H. Horst, 107–125. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Foster, Robert J., and Heather A. Horst. 2018. The Moral Economy of Mobile Phone: Pacific Islands Perspectives. Canberra: ANU Press.

- González, Roberto J. 2020. Connected: How a Mexican Village Built Its Own Cell Phone Network. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- GSMA. 2019. The Mobile Economy Pacific Islands 2019. https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GSMA_MobileEconomy2020_Pacific_Islands.pdf.

- Gupta, Akhil. 2015. “‘Suspension.’ Theorizing the Contemporary.” Fieldsights, September 24. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/suspension.

- Gupta, Akhil. 2018. “The Future in Ruins: Thoughts on the Temporality of Infrastructure.” In The Promise of Infrastructure, edited by Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, 62–79. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Highet, Catherine, Michael Nique, Amanda H.A. Watson, and Amber Wilson. 2019. Digital Transformation: The Role of Mobile Technology in Papua New Guinea. London: GSMA.

- Hobbis, Geoffrey. 2020. The Digitizing Family: An Ethnography of Melanesian Smartphones. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Horst, Heather A. 2018. “Creating Consumer-Citizens: Competition, Tradition, and the Moral Order of the Mobile Telecommunications Industry in Fiji.” In The Moral Economy of Mobile Phones: Pacific Islands Perspectives, edited by Robert J. Foster, and Heather H. Horst, 73–92. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Howell, Catherine, and Darrell M. West. 2016. “The Internet as a Human Right.” Brookings, 11 July. Accessed 8 November 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2016/11/07/the-internet-as-a-human-right/.

- Howes, Stephen. 2021. “Australia Buys Digicel, PNG’s Mobile Monopoly.” Devpolicyblog, 26 October. Accessed 8 November 2022. https://devpolicy.org/australia-buys-digicel-pacific-pngs-mobile-monopoly-20211026/.

- ITU News. 2015. “Leader Interview with Denis O’Brien.” No. 1 (January/February). https://www.itu.int/bibar/ITUJournal/DocLibrary/ITU011-2015-01-en.pdf, accessed 10 November 2022.

- Ketterer Hobbis, Stephanie. 2018. “Mobile Phones, Gender-Based Violence, and Distrust in State Services: Case Studies from Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 59 (1): 60–73. doi:10.1111/apv.12178

- Kulick, Don. 1992. Language Shift and Cultural Reproduction: Socializations, Self and Syncretism in a Papua New Guinean Village. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lemanski, Charlotte. 2018. “Infrastructural Citizenship: Spaces of Living in Cape Town, South Africa.” In The Routledge Handbook on Spaces of Urban Politics, edited by Kevin Ward, Andrew E. G. Jonas, Byron Miller, and David Wilson, 350–360. London: Routledge.

- Lemanski, Charlotte. 2022. “Infrastructural Citizenship: Conceiving, Producing and Disciplining People and Place via Public Housing, from Cape Town to Stoke-on- Trent.” Housing Studies 37 (6): 932–954. doi:10.1080/02673037.2021.1966390.

- Lipset, David. 2018. “A Handset Dangling in a Doorway: Mobile Phone Sharing in a Rural Sepik Village (Papua New Guinea).” In The Moral Economy of Mobile Phones: Pacific Islands Perspectives, edited by Robert J. Foster, and Heather H. Horst, 19–37. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Logan, Sarah, and Miranda Forsyth. 2018. “Access All Areas? Telecommunications and Human Rights in Papua New Guinea.” Human Rights Defender 27 (3): 18–20.

- Logan, Sarah, and Joseph Suwamaru. 2017. “Land of the Disconnected: A History of the Internet in Papua New Guinea.” In The Routledge Companion to Global Internet Histories, edited by Gerard Goggin, and Mark McLelland, 284–295. New York: Routledge.

- Martin, Keir. 2013. The Death of the Big Men and the Rise of the Big Shots: Custom and Conflict in East New Britain. New York: Berghahn.

- Meese, James, Rowan Wilken, and Ioana Chan Mow. “Uneven Topologies of Communication: Mobiles and Transnational Location in Samoa.” In Location Technologies in International Context, edited by Rowan Wilken, Gerard Goggin, and Heather Horst, 93–107. New York: Routledge.

- Miller, Daniel, Laila Abed Rabho, Patrick Awondo, Maya de Vries, Marília Duque, Pauline Garvey, Laura Haapio-Kirk, et al. 2021. The Global Smartphone: Beyond a Youth Technology. London: UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787359611.

- Murdock, Ryan. 2022. “Disconnected: Electrification in Papua New Guinea.” Harvard International Review. 16 May. Accessed 9 November 2022. https://hir.harvard.edu/electrification-in-papua-new-guinea/.

- Oxford Business Group. 2019. “Infrastructure Investments and Increased Competition to Support Burgeoning Digital Economy in Papua New Guinea.” In The Report: Papua New Guinea 2019. Accessed 9 November 2022. https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/new-connections-key-infrastructure-investments-and-increased-competition-are-expected-support.

- Post-Courier. 2015a. “Smartphone Sales Through the Roof.” July 13.

- Post-Courier. 2015b. “Digicel Upgrades Network.” June 29.

- Post-Courier. 2022. “Telstra Takes Over Digicel.” July 15.

- Pype, Katrien. 2021. “(Not) In Sync—Digital Time and Forms of (Dis-)connecting: Ethnographic Notes from Kinshasa (DR Congo).” Media, Culture & Society 43 (7): 1197–1212. doi:10.1177/0163443719867854.

- Robbins, Joel. 1998. “On Reading ‘World News’: Apocalyptic Narrative, Negative Nationalism and Transnational Christianity in a Papua New Guinea Society.” Social Analysis 42 (2): 103–130.

- Sora, Mihai, and Jonathan Pryke. 2021. “Telstra’s Digicel Pacific Challenge.” Lowy Institute. Accessed 9 November 2022. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/telstra-s-digicel-pacific-challenge.

- Suwamaru, Joseph. 2015. Aspects of Mobile Phone Usage for Socioeconomic Development in Papua New Guinea. SSGM Discussion Paper 2015/11. Canberra: Australian National University. https://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2016-07/dp_2015_11_suwamaru_proof2.pdf.

- SWRVE. 2020. Digicel Generates Over 941 K New Plan Purchases and Triples Engagement with Real-Time Relevance. Case Study. https://www.gsma.com/membership/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Swrve-Digicel-Case-Study-A4.pdf.

- Telban, Borut, and Daniela Vávrová. 2014. “Ringing the Living and the Dead: Mobile Phones in a Sepik Society.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 25 (2): 223–238. doi:10.1111/taja.12090

- The National. 2007. “Telikom’s New Image.” September 12.

- The National. 2017. “Digicel PNG Launches My Digicel Application.” January 20.

- The National. 2019. “He was a Doting Dad.” September 2.

- Thomas, Verena, Jackie Kauli, Wendy Bai Magea, Robert Foster, and Heather Horst. 2018. Mobail Goroka. Goroka, PNG: Center for Social and Creative Media, University of Goroka.

- Uimonen, Paula. 2015. “‘Number Not Reachable’: Mobile Infrastructure and Global Racial Hierarchy in Africa.” Journal des Anthropologues 142–143: 29–47. doi:10.4000/jda.6197

- von Schnitzler, Antina. 2008. “Citizenship Prepaid: Water, Calculability and Techno-Politics in South Africa.” Journal of Southern African Studies 94 (4): 899–917. doi:10.1080/03057070802456821

- Wafer, Alex. 2012. “Discourses of Infrastructure and Citizenship in Post-Apartheid Soweto.” Urban Forum 23: 233–243. doi:10.1007/s12132-012-9146-0

- Wall, Jeffrey. 2020. “China’s ‘Debt Trap Diplomacy’ is About to Challenge Papua New Guinea—and Australia.” The Strategist. Australian Strategic Policy Institute. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinas-debt-trap-diplomacy-is-about-to-challenge-papua-new-guinea-and-australia/.

- Warschauer, Mark. 2003. “Dissecting the ‘Digital Divide’: A Case Study in Egypt.” The Information Society 19: 297–304. doi:10.1080/01972240309490

- Watson, Amanda H. A. 2011. “The Mobile Phone: The New Communication Drum of Papua New Guinea.” PhD thesis, Queensland University of Technology.

- Watson, Amanda H. A., and Gary Seddon. 2017. “Ten Years in Papua New Guinea: In Conversation with Digicel.” Devpolicyblog, 31 July. Accessed 9 November 2022. https://devpolicy.org/ten-years-papua-new-guinea-conversation-digicel-20170731/.

- Watson, Amanda H. A., and Beatrice Mahuru. 2017. “Corporate Philanthropy in Papua New Guinea: In Conversation with the Digicel Foundation.” Devpolicyblog, 30 May. Accessed 9 November 2022. https://devpolicy.org/corporate-philanthropy-papua-new-guinea-conversation-digicel-foundation-20170530/.

- Watson, Amanda H. A. 2021a. “Undersea Internet Cables in the Pacific Part 1: Recent and Planned Expansion.” In Brief 2021/19. Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. https://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2021-08/undersea_internet_cables_in_the_pacific_part_1_-_recent_and_planned_expansion_amanda_h_a_watson_department_of_pacific_afffairs_in_brief_2021_19.pdf.

- Watson, Amanda H. A. 2021b. “Undersea Internet Cables in the Pacific Part 2: Cybersecurity, Geopolitics and Reliability.” In Brief 2021/20. Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. https://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2021-08/undersea_internet_cables_in_the_pacific_part_2_-cybersecurity_geopolitics_and_reliability_amanda_h_a_watson_department_of_pacific_afffairs_in_brief_2021_20.pdf.

- Wilk, Richard. 1994. “Colonial Time and TV Time: Television and Temporality in Belize.” Visual Anthropology Review 10 (1): 94–102. doi:10.1525/var.1994.10.1.94

- Zakrzewski, Cat. 2021. “3G Shutdowns Could Leave Most Vulnerable Without a Connection.” Washington Post, November 13. Accessed 9 November 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/11/13/3g-service-ending-fcc/.