ABSTRACT

This study explored the characteristics and consequences of criminogenic problem gambling in Sweden. All verdicts (N = 283,884) delivered by Swedish general courts between 2014 and 2018 were subjected to a key word search for the term ‘problem gambling’ and its synonyms. Verdicts that met the search criterion (n = 1,232) were inspected manually and cases in which problem gambling clearly was the main cause for committing crime (n = 282) were analyzed quantitatively. The most common types of crimes were fraud and embezzlement (67%). Each year around 400 individuals, companies, and organizations became victims of gambling-driven crimes, with nonprofit organizations being the most severely affected. Those convicted for such crimes were older, and to a greater extent female and first-time offenders, compared to national statistics on crimes in general. This suggests that in Sweden, middle-aged women are a high-risk group for severe gambling problems that should be monitored particularly closely by gambling companies for indications of problematic gambling. We conclude that although crimes driven by problem gambling are relatively rare in the justice system, they bring considerable harm to victims and the perpetrators themselves.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Gambling can be associated with crime in at least five ways (Banks & Waugh, Citation2019; Spapens, Citation2008). First, gambling can be offered to the public by individuals, organizations, or commercial companies without a legal permit. Second, the provision of gambling with a legal permit can be conducted in an unlawful way. Thirdly, gambling activities can in various ways be infiltrated by criminal individuals or organizations, with the purpose of money laundering, match fixing, and other illicit schemes. Fourthly, gambling can be part of a criminal lifestyle and/or driven by the same psychological traits that predispose an individual to criminal behavior. Finally, excessive gambling can lead individuals to commit crimes, that is, criminogenic problem gambling, which is the subject of this study.

Previous studies of this issue have used a number of different methodological approaches and data sources. The main lines of inquiry have been: studies of forensic populations (Banks et al., Citation2019; Riley et al., Citation2017; Widinghoff et al., Citation2018), research on treatment-seeking people with problem gambling (PG) (Lind & Kääriäinen, Citation2018; Mestre-Bach et al., Citation2018), population, registry, and public health studies (Laursen et al., Citation2016; Martins et al., Citation2014), mixed methods studies, including analysis of newspaper reporting (Albanese, Citation2008; Binde, Citation2016b), analyses of police reports and records (Kuoppamäki et al., Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2003), and studies of court documents, as in this study.

These studies have consistently produced three main findings. First, criminality is more common among individuals with PG than among the general population. Studies from various jurisdictions and time periods have shown that among those who seek help for PG, between 20% and 60% have committed crimes to fund their gambling (Lind & Kääriäinen, Citation2018). Second, in addition to, or instead of, a causal link between PG and crime, there can be additional factors – psychological, a personality trait, or a social context – that predisposes an individual both for PG and for committing crime (Adolphe, Khatib, et al., Citation2019; Kryszajtys et al., Citation2018; Lind et al., Citation2015). For example, antisocial personality disorder (Mishra et al., Citation2011; Widinghoff et al., Citation2018), impulsivity (Ellis et al., Citation2018), greater risk-taking behavior (Mestre-Bach et al., Citation2018) and social disadvantages (Lind et al., Citation2021). Third, people with PG are overrepresented among perpetrators of specific types of crimes, particularly, fraud and embezzlement, which is in line with the findings of the present study.

This study aimed to explore the characteristics and consequences of criminogenic PG in Sweden. The term ‘criminogenic’ refers to something that tends to cause the perpetration of crime. The more specific research objectives were to find out what types of such crimes are committed, what characterizes perpetrators and victims, what are the harms in economic and other terms, and what kinds of sanctions are imposed on those found guilty. Knowledge about the characteristics of criminogenic PG is useful for the regulation of gambling, the prevention of PG, the ability of courts to arrive at fair and appropriate rulings in cases that involve people who gamble, and for gambling companies that wish to proactively counteract excessive and harmful gambling among their customers. It also provides insight into the nature and consequences of severe PG.

In this study, data were extracted from verdicts delivered by general courts. To our knowledge, there are about 10 previous studies based on verdicts and prosecutions. Most of them focused on property crimes such as embezzlement and fraud (Marshall & Marshall, Citation2003; Sakurai & Smith, Citation2003; Smith et al., Citation2003; Warfield, Citation2008, Citation2011). Three studies, all from Australia (Crofts, Citation2002, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Law, Citation2010; Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Citation2013), resemble our study as they were more general in scope and based on court documents. These studies found that criminogenic PG caused mainly fraud and other property offenses, and the majority of offenders were men. The specific contribution of this study, which was based on a greater number of cases than any previous investigation, is the detailed analysis of the perpetrators’ age and gender, the thorough comparison of our results with national statistics on crime and the close examination of the types of crimes and victims.

Method

Material

The primary data comprised all verdicts (N = 283,884) delivered by Swedish general courts on all levels in the five-year period from 2014 to 2018. The verdicts were available in the form of searchable PDF-files in the JUNO database and accessible online via the Stockholm University Library.

A verdict delivered by a Swedish district court is presented in a document that can be less than 10 pages and as long as several hundred pages. Verdicts from courts of appeal may consist of only a statement that the court agrees with the district court, or include lengthy discussions if not. The verdict of the district court is always attached.

A district court verdict includes stories about the crime told by the offender, victims, and witnesses, as well the presentation of physical and other evidence. Court discussions can be brief or elaborate depending on the evidence and confession of crimes. A picture – sketchy or detailed – is rendered of the crime, along with the people involved. The defendant, victims, witnesses, and evidence (e.g. online casino account statements) may tell or suggest that PG was the driving force behind the commitment of crime; the court may agree, question this, or make no comment.

The final part of the verdict concerns the sanctions. Mitigating and aggravating circumstances of the crime are discussed and weighted against each other. Often the assessment of the Prison and Probation Service, of the social and mental status of the offender, is referred to; this statement is sometimes attached to the verdict. In recent years, this assessment includes a check-box for PG. If a psychiatric evaluation of the offender has been conducted, its main result is stated. If the crime is not so severe that the law’s prescribed level of punishment is imprisonment, the court discusses alternatives such as fines, probation, and various forms of treatment and help for psychiatric conditions, addictions, or social maladjustments.

We compared, wherever relevant and possible, the results from our study with national statistics on crime in general. All such data were obtained from the website of the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brå) in the form of electronic spreadsheets covering selected years, populations, and variables (https://www.bra.se/).

The study was given ethics approval from the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2018/2021-31/5).

Coding

The search function in the JUNO database was used to find verdicts in general courts where any of the three most common Swedish terms for PG appeared (‘spelproblem,’ ‘spelmissbruk,’ ‘spelberoende’). The search yielded 1,232 verdicts with a total of approximately 35,000 pages. Our available time and resources did not allow us to code this extensive material in the conventional manner, that is, two individuals separately examining and coding each verdict. Instead, we divided the verdicts into blocks covering six months, of which each was allocated to one of the three researchers, who manually inspected the verdicts, sorted them into one of four categories () and coded the data. The accuracy of this sorting was verified by another researcher, who also checked that data had been entered correctly. As to the first three categories, the verifier occasionally noticed errors in the coder’s categorizations within these, but there was virtually no actual disagreement. The sorting into categories three and four was discussed in 32 cases out of a total of 842 verdicts/cases in these two categories, that is, in 4% of cases. Coder and verifier first discussed the case and if disagreement persisted, all three researchers discussed the case until consensus was reached. In delicate borderline cases, we choose not to classify as criminogenic PG, to ensure that this category did not include debatable cases. The four categories were the following.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing the sequence in which cases of criminogenic problem gambling were identified.

Irrelevant (221 verdicts): The verdict was unrelated to PG. For example, ‘problem gaming’, not ‘problem gambling’, was mentioned, or it was stated that the defendant had no gambling problem.

Miscellaneous (130 verdicts): someone or something mentioned in the verdict had to do with PG but the perpetrator of the crime had no PG, or the prosecuted person was found not guilty. For example, the victim of crime had gambling problems or the prevention of PG was emphasized in a case involving illegal gambling machines.

Association (560 verdicts): the perpetrator had, or may have had, before or at the time of the crime, a gambling problem, but the court did not write that PG was the main reason for the commitment of crime. In this category, there were numerous cases in which perpetrators told stories about gambling, gambling debts, and problems, which were dismissed by the court as being untrue. Such stories appeared to have been told mostly to explain monetary transactions involving proceeds from drug crimes or to claim that crimes were committed under threat from creditors of gambling debts and therefore not punishable. There were also many verdicts in which the court noted that the defendant probably or evidently had a gambling problem but did not consider this to be the main cause for committing the crime. Finally, there were verdicts in which the court did not comment on stories about PG. This might be because the court did not consider these stories – true or not – relevant when deciding on the sanction or when expounding the rationale for the judgment.

Criminogenic PG (282 cases, verdicts on the same case delivered by a district and a court of appeal combined): our strict definition to identify cases of criminogenic PG was that the court explicitly stated that excessive gambling was the main driving force of the crimes. Thus, in these cases, it was clear beyond reasonable doubt that PG caused the commitment of crime and that most of the proceeds from this had been used for gambling, or for covering pressing gambling debts or critical financial shortfalls caused by PG. To illustrate, the following are citations from three different verdicts: ‘ … all this criminality originates in NN’s severe gambling problems,’ ‘NN’s criminality is fully linked to his [gambling] addiction,’ and ‘NN has told the following. He committed the present offenses because of a need of money to finance his gambling addiction. … When evaluating NN’s statements, the District Court finds that his confession is fully supported by the [police] investigation presented.’

Data on each of the 282 cases of criminogenic PG were entered in an MS Excel spreadsheet. It contained information about the cases (such as verdict number and the name of courts), the perpetrators (such as gender, age, and previous criminality), the victims, the harms caused in economic terms, and other potentially relevant factors.

In cases where two or more perpetrators, of which only one committed crime because of PG, were sanctioned to be jointly and severally liable to pay damages, only the proportion of the defendant with criminogenic PG was coded as economic harm to victims. When a verdict concerned several crimes, of which only some had been committed because of PG, we only coded data pertaining to the PG crimes. When a case included crimes of different types and/or victims of different kinds, these were coded as primary, secondary, and tertiary, according to the severity in economic terms, as this was specified in the list of crimes and victims given in the first part of a verdict. For example, if a perpetrator had embezzled a total amount of SEK 842,385 and committed thefts for a total amount of SEK 18,516, then embezzlement was coded as primary crime and theft as secondary.

Analysis

The statistical analyses presented in this article are frequency counts, averages, and median values of factor variables, pertaining to all cases or subsets thereof. Also, chi-squared tests were performed as well as t-tests to explore the differences between the groups in the sample as well differences and similarities between our sample and crime statistics on a national level. All analyses were carried out in Excel and SPSS V.25. Since several chi-squared tests and t-test were carried out, the significance level was adjusted for 100 comparisons to p = .0005. The significance level presented for each test will be p = .000, which means that it is p = .0005 or lower. The prerequisites discussed by Armstrong (Citation2014) for Bonferroni corrections were met.

The chi-square and t-tests rests on the null hypotheses. In this study, it essentially means that we compared the distribution of values that we found with a hypothetical random distribution. This gives an indication of the robustness of our results, that is, to what degree they are likely to reflect factors in the real world or may be the result of random variation. However, it should be kept in mind that our 282 cases are a complete sample; they were all cases over the five-year period that met the criteria for being criminogenic PG. They constituted the reality of criminogenic PG in Sweden, according to our data and definition, over these years. Thus, even if a distribution of values does not reach statistical significance, compared with the null hypothesis, the distribution was the reality that Swedish courts faced and that can be considered now in retrospect by those with an interest in understanding the relationships between PG and crime in Sweden.

Results

Prevalence

The number of criminogenic PG cases, over the five-year period from 2014 to 2018, was the following for each year, respectively: 47, 50, 59, 63, and 63. Although the number of cases increased from 47 in 2014 to 63 in 2018, with an average 56 cases per year, this increase is not big enough to be confidently regarded as a trend (SD = 7.47). Nor did we find any clear trend over the five-year period for any other variable. During the same period, the total number of judgments in general courts in Sweden was, according to Brå, fairly stable with an average 59,000 judgments per year. Thus, the proportion of criminogenic PG cases in relation to the total number of judgments in general courts was also fairly stable, at 0.1%.

Perpetrator characteristics

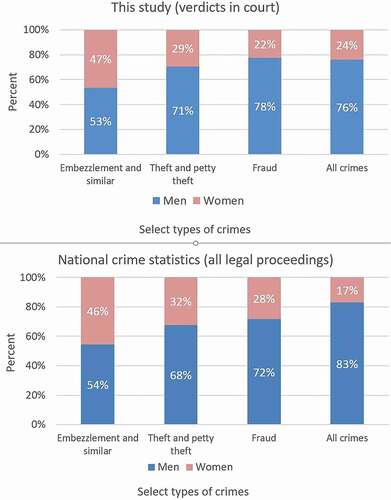

For the five-year period, 76% of the perpetrators in the criminogenic PG cases were men and 24% were women. The proportion of women was notably higher than in national statistics on convictions in general during the same period, where 16% of the offenders were female which is a statistically significant difference (χ2 (1, N = 294,884) = 16.882, p = .000).

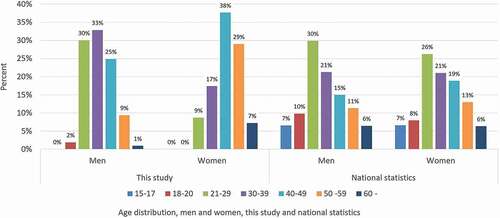

The mean age of the perpetrators in the criminogenic PG cases was 39 years, with 36 years (SD = 10) for men and 46 years (SD = 11) for women; this age difference between men and women was statistically significant, t(280) = −6.755, p = .000. shows the percentages of convicted men and women in different age groups in this study compared with national crime statistics. While the national statistics show only minor differences between the sexes as to the proportions of crimes committed in the seven age spans, there were noteworthy and statistically significant differences in our study (χ2 (5, n = 282) = 40.67, p = .000). Also, there was a significant difference between the men in our study and the national crime statistics when it comes to age groups (χ2 (6, N = 249,223) = 65.87, p = .000) and the same was true for women in the sample compared to the national crime statistics (χ2 (6, N = 45,919) = 45.34, p = .000). Sixty-seven percent of female perpetrators in our study were 40–59 years old, which is twice as much as the proportion of male offenders in this age span (34%). This also differs notably from national crime statistics, where close to half of the convicted females were in the age 21 to 39 years. Another noteworthy finding was that there were very few convicted in age ranges 15–17 and 18–20 years (all of them males), perpetrator ages which in national crime statistics account for 15% (females) and 17% (males) of crimes ruled in general courts.

Figure 2. Comparison of gender and age distribution between criminogenic PG sentences in this study and national statistics on sentences in district courts, 2014–2018, percentages.

The verdicts stated the defendant’s registered address at the time of trial. This might not have been their address at the time when the crime was committed, but we assumed there was no bias in moving to bigger or smaller cities among the defendants between the time of committing crimes and being sentenced, and therefore analyzed the data. Twenty-six percent of the offenders lived in one of Sweden’s three largest cities, which is about the same proportion as the general population. However, although not statistically significant compared with the null hypothesis, the proportion of women was bigger among perpetrators living in communities with less than 10,000 inhabitants (30%) than the proportion of women among all the 282 cases (24%). The mean age of these females (n = 21) was 49 years, thus older than the average age of all females in the study (46 years), although the difference in age between the two groups was not statistically significant, t(67) = 1.56, p = .12. Notably, 81% (n = 17) of these women had no criminal record, which was a somewhat larger proportion than in the whole group (see below).

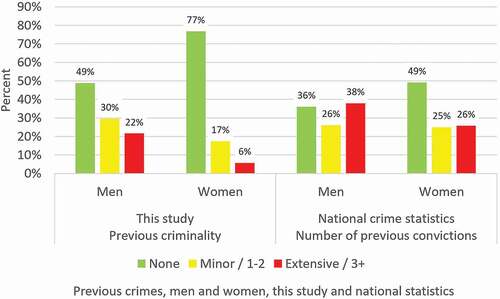

In this study, we coded ‘previous criminality’ as ‘None’, ‘Minor’, or ‘Extensive’, based on the number of prior convictions mentioned in the verdict and the number of separate crimes to which they referred. In the criminogenic PG cases, 56% of the perpetrators had no prior convictions, 27% had minor, and 18% had extensive previous criminality.

In national crime statistics, the number of previous convictions in the past ten years is available for those found guilty in court. ‘No previous convictions’ is thus essentially the same as our ‘None’ category of previous criminality, while our ‘minor’ and ‘extensive’ previous criminality is roughly comparable to 1–2 previous convictions and three or more previous convictions, respectively. shows data from our study compared with national crime statistics.

Figure 3. Comparison of previous criminality and previous convictions between this study and national crime statistics, 2014–2018, percentages.

Again, women in the criminogenic PG group stood out. Compared to men, the proportion of first-time female offenders was notably higher (77% women and 49% men), and the same was true when compared to female convicts in national statistics during the same time period (49%). The differences between men and women among our cases, regarding previous criminality, were statistically significant (χ2 (2, n = 282) = 17.58, p = .000). The proportion of women with extensive previous criminality was substantially lower in the criminogenic PG group (6%) than in national crime statistics on those with three or more convictions (26%). There were similar differences between men in the criminogenic PG group compared with men in national crime statistics, but not so pronounced. However, both these differences were statistically significant; as to men: χ2 (2, n = 248,683) = 25.62, p = .000, and as at to women: χ2 (2, n = 45,919) = 23.01, p = .000.

Types of crimes

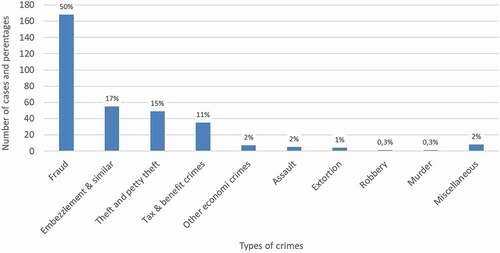

The most common type of crime caused by criminogenic PG was fraud (50% of the cases), followed by embezzlement and similar offenses (17%), thefts of varying severity (15%), and tax and benefit crimes (11%; ). There were a few cases of other economic crimes, assault, extortion, and miscellaneous crimes, such as drug trafficking, as well as one case each of robbery and murder.

Nearly all these crimes were committed to procure money. A few were committed for other gambling-related reasons, for example, assault in connection with domestic quarrels about excessive gambling and infliction of damage on gambling equipment in frustration over big losses. This distribution of types of crimes is very different from that shown by national crime statistics. For example, two of the most common types of crimes in national statistics are minor drug offense and unlawful driving, each constituting slightly more than 10% of all legal proceedings; conversely, the most common type in our study was fraud with 50% of the cases, which in national statistics amounted to only 1% of all legal proceedings.

The proportion of men and women in selected types of offenses, among the cases of criminogenic PG in this study compared with national crime statistics for the same time period, is shown in . The numbers are not perfectly comparable because our study concerned cases ruled in court while the national statistics refer to all kinds of legal proceedings, that is, in addition to convictions it includes abstention from prosecution and summary imposition of a fine. No large differences were found between the results from our study and national crime statistics. The most notable observation is that while men are strongly over-represented when it comes to crime in general, this does not hold true for embezzlement and larceny by servant, which, both in our study and in national statistics, had roughly the same proportion of men and women among the offenders.

Types of victims

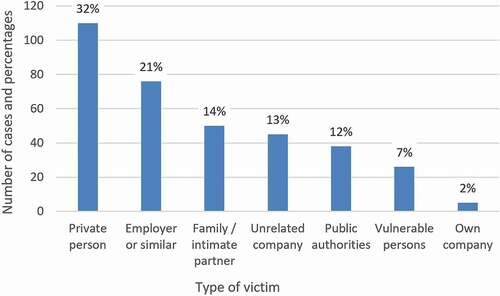

On average, 408 separate victims were directly affected per year, which means approximately seven victims per case. However, since some of the cases had a very high number of victims – the highest number was 68 in a case of frauds committed at an online secondhand market – the median value was lower at two victims per case. It is important to note that affected employers or organizations as well as ‘Public authorities’ (state, county, municipality, tax and benefit authorities, etc.) were coded as a single victim, although the crime in reality could directly or indirectly affect many individuals.

As described earlier, we coded the types of victims directly affected by the crime as primary, secondary, and tertiary, according to the severity in which victims were affected. In 85% of cases, there were just one type of victim (primary); in 14% of cases, there were two types of victims (primary and secondary); and in 1%, there were three types of victims (primary, secondary, and tertiary). Thus, the perpetrators usually focused on just one type of victims, although these could be subject to different kinds of crimes.

Among the cases of criminogenic PG, 32% of the primary victims were ‘private person’, that is, neither a current or previous family member, nor a specifically vulnerable person (). These individuals could be completely unknown people, who were subjected to, for example, fraud committed via the internet, but also neighbors, coworkers, and acquaintances. Employers and nonprofit organizations (NPO) were primary victims in 21% of the cases, as the crimes were committed in the workplace or at an organization where the perpetrator held a position of trust. Family members and current or former intimate partners were primary victims in 14% of the cases. ‘Unrelated companies’ – companies at which the convicted person did not work – were primary victims in 13% of the cases. Twelve percent of the offenses were directed primarily at public authorities, typically tax and benefit crimes, and smuggling. The category ‘Vulnerable persons’ included, for example, persons under guardianship of the perpetrator and elderly people in a nursing home where the perpetrator worked; these were 7% of the primary victims. Only 2% of the crimes affected primarily the perpetrator’s own company (accounting violations and similar), which often meant that the company was bankrupted and business partners and creditors were financially harmed. These proportions were about the same when secondary and tertiary victims were also considered.

Economic harm

The economic harm from criminogenic PG was calculated from information in the verdict on how much money the perpetrator had unlawfully acquired and/or had to pay in damages. Here, the victim is the one who finally was economically affected by the crime, for example, a bank in a case where a private person (direct victim) had been exposed to credit card fraud. The indirect costs and harms to society at large were not included, for example, costs for the judicial and correctional systems.

shows the economic harm caused by criminogenic PG across different categories of affected. The total yearly average was 40 million SEK, where companies suffered the largest harm, 27 million per year (SEK 1 million is roughly equivalent to EUR 96,400 and USD 114,000). There was one case with SEK 21 million lost; this was an employee at a bank who embezzled money and spent it all on online gambling. However, considering the median value, it were the NPOs that stood out as the most severely affected, with close to SEK 450,000 in economic harm. In one of these cases, more than SEK 6 million was embezzled by the treasurer at an organization that helped vulnerable children in poor countries. Family members and intimate partners typically lost relatively small sums, although there was one case with loss of over three million SEK.

Table 1. Economic harm from criminogenic problem gambling (SEK). Median values do not include cases in which there were no economic harm, such as assault.

Penalties

While a few perpetrators already had, at the time of trials, made good economic harm caused by their crime, most of them had not and were sentenced to pay damages to the injured party, that is, compensate in money for loss or injury. Some were sentenced to pay fines. If a crime is punishable by a prison sentence, an offender must pay a minor fee to the Fund for Victims of Crime. The cost for the defense lawyer has to be paid by those who can afford it, otherwise this cost is covered by public funds. We calculated the sum of damages to be paid, penalties and costs, which represent the sum of money that an offender had to pay as a result of committing the crime and being sentenced for it. The average sum per offender was SEK 479,967 and the median sum was SEK 39,321. The highest sum an offender was sentenced to pay was SEK 21,257,499.

Additionally, not included in these calculations, was the interest on damages from the time when damage was done. At present, this interest rate is about 7%. Thus, all damages to be paid were in reality larger than the figures reported in this study. Many of these compensations continued to grow larger after the verdict even if the offender regularly made payments, for example, as a result of an attachment of salary.

In 52% of the 282 criminogenic PG cases, the offender was sentenced to probation and/or community service. Imprisonment was the sentence in 26% of the cases (median length: 15 months). In 17% of cases, the sentence was only conditional or consisted of only fines. A court-imposed care order was issued in 4% of cases, which meant that the offender had to spend time in a closed residential care institution specialized in treating addictions.

Of specific interest to this study was to assess to what extent courts decided on treatment for PG. In 40% of the criminogenic PG cases, probation included treatment in an outpatient care PG program. Such programs are run by local parole offices, local, and regional health services, mutual support societies, or are included in a more general addiction treatment. In 18% of the cases, no PG treatment was mandated, and there was no prison sentence, because the offender had quit gambling, with or without external support, and did not suffer from PG any more. The crime was so severe in 17% of the cases that no sanction other than imprisonment could be considered. No PG treatment was mandated in 6% of cases because the offender already participated in such treatment. In another 5% of the cases, PG treatment could have been a possible sanction but because the offender had previously been offered such treatment without any effect, the court decided on a prison sentence. In 4% of the cases, treatment in a residential care institution was stipulated. Some offenders (3%) objected to treatment and thus did not receive any. Finally, in 3% of cases, it was unclear from the verdict why no PG treatment was mandated. In 2% of cases, the court wrote that there was no suitable PG treatment available, and 2% of the offenders were sentenced to treatment for addictions other than PG and/or psychiatric conditions. In summary, close to half of the offenders were sentenced to some form of treatment for PG or related disorders while about a quarter of them ended up in prison. As to those imprisoned, treatment for PG is in principle available on request; some prisons seem to have a reputation of offering better PG treatment than others.

Discussion

Prevalence

This study was a comprehensive survey of all verdicts in Swedish general courts over a five-year period, focusing on cases in which PG was, according to the court, the root cause of criminality. With 282 such cases, it is to our knowledge the largest study of its kind in any jurisdiction.

The variation in cases between 2014 and 2018 was too little to be considered a trend. Therefore, we do not speculate on how the distribution of cases over the five-year period might reflect the variations in PG incidence, prevalence, and recovery in Sweden over these years.

Perpetrator characteristics

About three-quarters of the perpetrators of gambling-driven crimes were men and one-quarter were women. This proportion is similar to that found in comparable studies from Australia (Law, Citation2010; Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Citation2013) and roughly the same as the proportion of men and women with PG according to the 2015 Swedish prevalence study (20% and 80%, respectively, Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2016, Table 2.3). However, the 2018 Swedish prevalence study showed, that approximately half of the individuals with problem and moderate risk gambling (PGSI 3+, Ferris & Wynne, Citation2001) were women, except in the age group 18–24 where men still dominated (Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2019). If the proportion of women also increased among those with severe and thus potentially criminogenic PG, this might be too recent to be clearly reflected in PG-driven criminality detected and judged in court.

Nevertheless, a main finding in our study is that female perpetrators were significantly older than male perpetrators; they were also older than female perpetrators in national crime statistics. This is consistent with the picture – rendered by results from prevalence studies – that a specific and growing group of females with PG in Sweden are middle-aged women who gamble on online slots and online casino (Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2019; Håkansson & Widinghoff, Citation2020).

Our observations that the proportion of females was slightly elevated among perpetrators living in communities with less than 10,000 inhabitants, that these were on average three years older than all females in our study, and that 81% had no criminal record may reflect this picture. It is likely that these were mostly middle-aged females from all walks of life, living in communities with few if any possibilities for gambling in physical venues, who started to gamble online and subsequently developed PG. This can be expected when a new part of the population is exposed to particular risky forms of gambling (Abbott et al., Citation2018). Regular online casino gambling is still an unusual activity among Swedes; only about 1% of the adult population participated at least once a month in 2018. However, 61% of these regular gamblers were people with problem or moderate risk gambling (Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2019). More generally, female perpetrators being significantly older than men in our study likely also is an effect of the onset of PG being later for females than for men (Sundqvist & Rosendahl, Citation2019).

There are several probable reasons for the very few cases of young perpetrators in our study. First, the age limit for gambling is 18 years. Second, gambling among Swedish youth and young adults has become increasingly uncommon (Svensson & Zetterqvist, Citation2019). Third, in many cases, it will take a few years for gambling to escalate from a harmless level to a harmful and criminogenic level.

Compared with national statistics, the perpetrators in our study were to a larger extent first-time offenders or had only a few previous convictions; this was especially so among women, of which 77% were first-time offenders and only 6% had extensive previous criminality. Most of the cases appeared to correspond to the scenario that the perpetrator had developed severe gambling problems and therefore a need for money so great and urgent that criminal acts emerged as a viable option. These people would most likely not have committed crimes unless they had gambling problems, and our study suggests that the most likely scenario, after the first conviction, is that the offender no longer gambles excessively and does not commit further crimes. The low proportion of perpetrators with extensive previous criminality also supports this interpretation – this subgroup is probably not characterized by offenders with a criminal lifestyle, but consists mainly of people with severe and persistent gambling problems. Another explanation for the high degree of first-time offenders could be the high incidence (i.e. new cases) of people with PG in the population. There appear to be no recent data on this, but over the one- or two-year period 2008/09-2009/2010, 79% of individuals with problem and moderate-risk gambling in Sweden were estimated to be new cases while 21% had persistent problems (Abbott et al., Citation2018).

Types of crimes, victims, and harm

As in previous studies of a similar kind (Crofts, Citation2002, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Law, Citation2010; Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Citation2013), fraud was the most common type of crime in this study (50% of the cases). This is not surprising, as many kinds of fraud, such as when committed on online secondhand markets, quickly produce cash and do not need much preparation, skill, courage, or physical strength. The next most common crimes were embezzlement and similar offenses. In these cases, the proverb ‘opportunity makes the thief’ applies. As several studies have shown (Binde, Citation2016a; Crofts, Citation2003b; Lesieur, Citation1984), the typical scenario is that the trusted employee or member of a NPO, who develops a gambling problem, needs cash, finds an opportunity to ‘borrow’ money at the place of work or at the organization, and gets trapped in a downward spiral of increasingly excessive gambling and thefts of money. Unlike crime in general, where the proportion of men is much greater than women (), there were about the same proportion of men and women among those who commit embezzlement and similar crimes in our study as well as in national statistics. A comparable study from Australia showed similar results, with 42% females (Warfield, Citation2008). Women’s higher prosecution rate for embezzlement could be due to female dominance in professions such as cashier and accountant (Bäckman et al., Citation2018). More generally, our findings on the proportion of men and women in three common types of crimes (embezzlement, theft and fraud) did not differ significantly from the proportion in national crime statistics. This indicates that there may be no apparent PG-specific gender factor affecting the choice of what money-generating crime to commit.

This article focuses on quantitative findings from the study and thus does not cover non-monetary harm, such as the emotional suffering and distress of people being victims of PG-driven crimes and charities losing their good reputation when money donated to them are revealed to finance excessive gambling rather than good causes. The non-monetary harm may by victims be experienced as harder to take than the monetary harm.

Penalties

The sanction for crimes that need not be punished by imprisonment nearly always included treatment for PG, if the perpetrator had not already successfully stopped gambling, was not already in treatment, agreed to treatment, or had received treatment before but had not shown improvement. With a few exceptions, treatment in some form was available, provided by probation offices, healthcare providers or mutual support societies.

The real extent of PG-driven criminality

This study shows only the minimum extent of criminogenic PG in Sweden. PG leads to crimes that are (a) not detected, (b) detected but not reported to the police, (c) reported to the police but not possible to investigate, (d) are subjected to other judicial procedures than in court, (e) ruled in court but the defendant was declared not guilty because of insufficient evidence, (f) ruled in court where the perpetrator was found guilty but PG was not mentioned in the written verdict, and (g) ruled in court where PG was mentioned but not explicitly said by the court to be the driving force behind the criminality. As to the last of these points, such cases may very well be present among the 560 verdicts in our study coded as ‘association’.

Undoubtedly, the cases covered by this study are merely the tip of the iceberg of crimes committed because of PG. A previous Swedish study (Binde, Citation2016b) on criminogenic PG committed in the workplace or in a NPO estimated that the real extent of such criminality was at least ten times higher than the number of cases that came to public attention when newspapers reported on cases in general courts. It should also be considered that, in addition to pure criminogenic PG, there are probably cases in which PG increases the frequency and scale of already established criminal behavior, rather than being its root cause, as well as cases in which the development of PG becomes the tipping-point into criminality which subsequently is driven mainly by other factors.

Implications for criminology

The General Theory of Crime (formulated by Michael Gottfredson and Travis Hirshie, see Piquero, Citation2009), is based on the assumption that failure in self-control is the key correlation of criminal offending. The theory has three key postulates: (1) criminal behavior peaks in late adolescent and then declines, (2) criminality early in life predicts criminality later in life; (3) there is high versatility in crime and associated deviant behaviors, such as drug use. Our results are not in line with these postulates when it comes to the age profile of offenders, their crime careers, and their versatility in crime. Instead, what we have found fits quite well with the findings of sociological studies of male embezzlers (Cressey, Citation1973) and female embezzlers (Zietz, Citation1981). Basic assumptions in these studies are that the social context of the perpetrator, as well as processual factors in the crime scenario (as to gambling, see: Binde, Citation2016a) are crucial for understanding why people commit these specific types of crimes. The details of psychological and sociological correlates, on the individual level, of PG-driven criminality could be interesting to explore within a criminological theoretical framework.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that it is a comprehensive survey based on all verdicts in Swedish general courts over a five-year period. Compared with previous studies based on similar data (Law, Citation2010; Crofts, Citation2002, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Citation2013), our study was based on a larger number of cases and verdicts from courts on all levels. We have also paid close attention to gender and have compared many of our results with national crime statistics, thereby showing the specific character of crimes driven by PG.

Because we focused on the 282 verdicts in which it was clear, beyond reasonable doubt, that the main reason for committing crimes was PG, the study produces reliable results regarding the character of such criminality. Our precise criteria of which cases to include and exclude from analysis also makes it possible to replicate the study in other countries where there is access to comparable court documents, as well as in the future in Sweden. Adding to the reliability of our results is that data extracted from the verdicts are either facts – such as gender, age, type of crime, and penalty – or intentions, motivations, circumstances, and activities that courts, after careful deliberation, have regarded as factual.

However, we cannot be sure that the views of the courts always were accurate; certainly, there are in the justice system cases in which courts have decided wrongly or failed to correctly evaluate important pieces of evidence. Some defendant might have committed gambling-driven crimes without there being any trace of that particular motive in the police investigation, and for some reason wishing not to bring this up in court. Furthermore, supplementary data, such as the offender’s view on the verdict, if he or she had been asked about it, were not available.

The study of criminogenic PG presents notable conceptual challenges, with multi-directional interactions between factors on the individual, psychological, sociological and cultural levels, as well as factors relating to risk/benefit balances for committing various crimes; this study cannot show this complexity. As noted above, our study cannot say much about cases in which PG only partially contributes to criminality driven mainly by other factors, and it does not provide a precise idea of the true extent of criminogenic PG in Sweden. For that purpose, research with a different design is needed, such as a self-report study of people who have recovered from PG. It is also a limitation that the verdicts did not provide information on some potentially relevant factors such as level of education and income.

Conclusion and policy implications

Much suffering can be caused to individuals who are victims of criminogenic PG, and companies and organizations lose substantial amounts of money. Perpetrators sometimes state in court that gambling has ruined their life, as in cases where big damages have to be paid and imprisonment awaits. As to the harm and suffering inflicted on the perpetrator’s family, the verdicts tell little, but it is well known that significant others are often greatly affected by PG (Holdsworth et al., Citation2013).

A troubling finding in our study is that middle-aged women were overrepresented among the perpetrators; most of them were first-time offenders. This is likely a recent development, caused by an increase in online casino and online slots gambling among such women. This high-risk group should be monitored particularly closely by online gambling companies for indications of problematic gambling. Another finding is that NPOs appear to be especially heavily affected by PG driven crimes committed by employees or trusted members. Thus, such organizations should increase their awareness of the risks of crimes being committed and establish effective control functions regarding those who manage their finances (Binde, Citation2016c). More generally, companies and organizations should be sensitive to the risk of their employees having alcohol, drug and gambling problems, as this not only negatively affects their work performance and might compromise workplace safety but because the workplace is a fruitful arena for the early prevention of such problems, before they have escalated to a severely harmful level (Binde, Citation2016c). For example, large companies and organizations should consider setting up confidential employee helplines or at least promoting national helplines.

A policy implication of this study is that gambling companies should do their utmost to prevent excessive gambling among their customers and that regulatory authorities should impose a very high standard for such prevention.

As we have described, there were numerous verdicts in the ‘associated’ category where the court had not discussed PG when presenting the rationale for the sanctions chosen. This suggests that increased knowledge about PG would benefit the decision-making of general courts. However, there seem to be little prospect in Sweden for introducing special gambling courts, as in some federal states in the USA (Laux, Citation2019; Moss, Citation2016) and in the state of South Australia (Adolphe, van Golde, et al., Citation2019). In Sweden, there is since long the generally accepted juridical standpoint that there should be no special courts for specific types of criminal offenses (Håkanson, Citation2015). There seem to be no recent studies in Sweden on the quality of, and the perceived and actual availability of, PG treatment in prisons

This study shows that PG has a noteworthy capacity to put individuals on a path that leads to increasing troubles, harm, and eventually crime. Although such cases are rare among all other crimes brought to courts, criminogenic PG causes considerable harm among those with PG, their significant others, and the victims.

Funding sources

Funding for this study was provided within the frame of the Swedish program grant ‘Responding to and Reducing Gambling Problems – Studies in Help-seeking, Measurement, Comorbidity and Policy Impacts’ (REGAPS) financed by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forte), grant number [2016-07091].

Constraints on publishing

No constraints on publishing were declared by the authors in relation to this manuscript.

Competing interests

Per Binde has no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this article. The author has no current or past affiliations with the industry. All his research funding has come from government funded research or public health agencies, with the exception of a minor grant, for writing a research review, received in 2014 from the Responsible Gambling Trust in the UK, which is an independent national charity funded by donations from gambling companies. Jenny Cisneros Örnberg has no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this article. The author has no current or past affiliations with the industry. All her research funding has come from government funded research. David Forsström has no conflicts of interest in relation to this article. However, David Forsström is currently funded by the Svenska Spel Research Council, which is an independent council that is funded by the Swedish gambling company Svenska Spel.

Preregistration statement

No preregistration was declared by the authors in relation to this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ulla Romild at the Public Health Agency of Sweden for advice on statistical issues and information about recent results from Swedish prevalence studies.

Data availability statement

No data set was declared by the authors in relation to this manuscript.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Per Binde

Dr Per Binde is Associate Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. His interest in gambling is broad, but with a focus on the cultural dimension of gambling and its social contexts. Research areas include problem gambling, mutual support, gambling advertising, and gambling and crime.

Jenny Cisneros Örnberg

Dr Jenny Cisneros Örnberg, Associate Professor at the Department of Public Health Sciences, Stockholm University is the principal investigator for the research program REGAPS (Responding to and Reducing Gambling Problems Studies). Her research interests include domestic and international policy-making in the field of public health, with a focus on regulation and law.

David Forsström

Dr David Forsström is currently doing a post doc at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet and works as a researcher at the Department of Psychology at Stockholm university. He is a psychologist and his main research interests are responsible gambling and esports betting.

References

- Abbott, M., Romild, U., & Volberg, R. (2018). The prevalence, incidence, and gender and age-specific incidence of problem gambling: Results of the Swedish Longitudinal Gambling Study (Swelogs). Addiction, 113(4), 699–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14083

- Adolphe, A., Khatib, L., van Golde, C., Gainsbury, S. M., & Blaszczynski, A. (2019). Crime and gambling disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(2), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9794-7

- Adolphe, A., van Golde, C., & Blaszczynski, A. (2019). Examining the potential for therapeutic jurisprudence in cases of gambling-related criminal offending in Australia. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 31(2), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2019.1603071

- Albanese, J. S. (2008). White collar crimes and casino gambling: Looking for empirical links to forgery, embezzlement, and fraud. Crime, Law and Social Change, 49(5), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-008-9113-9

- Armstrong, R. A. (2014). When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics, 34(5), 502–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12131

- Bäckman, O., Hjalmarsson, R., Lindqvist, M. J., & Pettersson, T. (2018). Könsskillnader i brottslighet – Hur kan de förklaras? [Gender differences in crime – How should they be explained?]. Ekonomisk Debatt, 46(4), 67–78. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1277209/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Banks, J., Waters, J., Andersson, C., & Olive, V. (2019). Prevalence of gambling disorder among prisoners: A systematic review. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 64(12), 1199–1216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X19862430

- Banks, J., & Waugh, D. (2019). A taxonomy of gambling-related crime. International Gambling Studies, 19(2), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2018.1554084

- Binde, P. (2016a). Gambling-related embezzlement in the workplace: A qualitative study. International Gambling Studies, 16(3), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2016.1214165

- Binde, P. (2016b). Gambling-related employee embezzlement: A study of Swedish newspaper reports. Journal of Gambling Issues, No. 34, 12–31. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2016.34.2

- Binde, P. (2016c). Preventing and responding to gambling-related harm and crime in the workplace. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 33(3), 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1515/nsad-2016-0020

- Cressey, D. R. (1973). Other people’s money: A study in the social psychology of embezzlement. The Free Press.

- Crofts, P. (2002). Gambling and criminal behaviour: An analysis of local and district court cases (report submitted to the New South Wales Racing and Gaming Authority). Casino Community Benefit Fund.

- Crofts, P. (2003a). Problem gambling and property offences: An analysis of court files. International Gambling Studies, 3(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356347032000142289

- Crofts, P. (2003b). White collar punters: Stealing from the boss to gamble. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 15(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2003.12036276

- Ellis, J. D., Lister, J. J., Struble, C. A., Cairncross, M., Carr, M. M., & Ledgerwood, D. M. (2018). Client and clinician-rated characteristics of problem gamblers with and without history of gambling-related illegal behaviors. Addictive Behaviors, 84(September), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.017

- Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: Final report. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. (2016). Tabellsammanställning för Swelogs prevalensstudie 2015. [Summary of tables, the Swelogs prevalence study 2015.].

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. (2019). Resultat från Swelogs 2018 (PPT presentation). Folkhälsomyndigheten. [Results from Swelogs 2018 (PPT presentation)]. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/globalassets/livsvillkor-levnadsvanor/andts/spel/swelogs/resultat-swelogs-2018-2019.pdf

- Håkanson, H. (2015). Specialdomstolar i samtiden: En komparativ studie av Migrationsöverdomstolens samt Mark- och miljööverdomstolens prejudikatbildningsfunktion (examensarbete på juristprogrammet) [Special courts in the present age: A comparative study of the settling of case law by the Migration Court of Appeal and the Land and Environmental Court of Appeal (master thesis)]. Juridiska fakulteten, Lunds universitet. http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/8513933/file/8567319.pdf

- Håkansson, A., & Widinghoff, C. (2020). Over-indebtedness and problem gambling in a general population sample of online gamblers. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(7), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00007

- Holdsworth, L., Nuske, E., Tiyce, M., & Hing, N. (2013). Impacts of gambling problems on partners: Partners’ interpretations. Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health, 3(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/2195-3007-3-11

- Kryszajtys, D. T., Hahmann, T. E., Schuler, A., Hamilton-Wright, S., Ziegler, C. P., & Matheson, F. I. (2018). Problem gambling and delinquent behaviours among adolescents: A scoping review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 34(3), 893–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9754-2

- Kuoppamäki, S.-M., Kääriäinen, J., & Lind, K. (2014). Examining gambling-related crime reports in the National Finnish Police Register. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(4), 967–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9393-6

- Laursen, B., Plauborg, R., Ekholm, O., Larsen, C. V. L., & Jeul, K. (2016). Problem gambling associated with violent and criminal behaviour: A Danish population-based survey and register study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9536-z

- Laux, K. (2019). Gambling addiction: Increasing the effectiveness and popularity of problem gambling diversion in Nevada courts. UNLV Gaming Law Journal, 9(2), 247–268. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1156&context=glj

- Law, M. (2010). Nothing left to lose: Problem gambling and crime. Anglicare Tasmania.

- Lesieur, H. R. (1984). The Chase: Career of the compulsive gambler (2nd ed.). Schenkman.

- Lind, K., Hellman, M., Obstbaum, Y., & Salonen, A. H. (2021). Associations between gambling severity and criminal convictions: Implications for the welfare state. Addiction Research & Theory, 29(6):, 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2021.1902995

- Lind, K., & Kääriäinen, J. (2018). Cheating and stealing to finance gambling: Analysis of screening data from a problem gambling self-help program. Journal of Gambling Issues, No. 39, 235–257. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2018.39.9

- Lind, K., Kääriäinen, J., & Kuoppamäki, S.-M. (2015). From problem gambling to crime? Findings from the Finnish National Police Information System. Journal of Gambling Issues, No. 30, 98–123. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2015.30.10

- Marshall, J., & Marshall, A. (2003). Gambling and crime in South Australia. In Study into the relationship between crime and problem gambling: A report to the minister (Appendix B). Independent Gambling Authority.

- Martins, S. S., Lee, G. P., Santaella, J., Liu, W., Ialongo, N. S., & Storr, C. L. (2014). Age of first arrest varies by gambling status in a cohort of young adults. American Journal on Addictions, 23(4), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12121.x

- Mestre-Bach, G., Steward, T., Granero, R., Fernández-Aranda, F., Talón-Navarro, M. T., Cuquerella, À., Baño, M., Moragas, L., del Pino-Gutiérrez, A., Aymamí, N., Gómez-Peña, M., Mallorquí-Bagué, N., Vintró-Alcaraz, C., Magaña, P., Menchó, J. M., & Jiménez-Murcia, S. (2018). Gambling and impulsivity traits: A recipe for criminal behavior? Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(6), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00006

- Mishra, S., Lalumière, M. L., Morgan, M., & Williams, R. J. (2011). An examination of the relationship between gambling and antisocial behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(3), 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9217-x

- Moss, C. B. (2016). Shuffling the deck: The role of the courts in problem gambling cases. UNLV Gaming Law Journal, 6(2), 145–175. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/glj/vol6/iss2/2

- Piquero, A. R. (2009). A general theory of crime and public policy. In H. D. Barlow & S. H. Decker (Eds.), Criminology and public policy: Putting theory to work (pp. 29–42). Temple University Press.

- Riley, B. J., Larsen, A., Battersby, M., & Harvey, P. (2017). Problem gambling among female prisoners: Lifetime prevalence, help-seeking behaviour and association with incarceration. International Gambling Studies, 17(3), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2017.1343367

- Sakurai, Y., & Smith, R. G. (2003, June). Gambling as a motivation for the commission of financial crime. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, No. 256, 1–6. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2003-06/apo-nid7325.pdf

- Smith, G., Wynne, H., & Hartnagel, T. (2003). Examining police records to assess gambling impacts: A study of gambling-related crime in the city of Edmonton. Alberta Gaming Research Institute.

- Spapens, T. (2008). Crime problems related to gambling: An overview. In T. Spapens, A. Littler, & C. Fijnaut (Eds.), Crime, addiction and the regulation of gambling (pp. 19–54). Martinus Nijhoff.

- Sundqvist, K., & Rosendahl, I. (2019). Problem gambling and psychiatric comorbidity – Risk and temporal sequencing among women and men: Results from the Swelogs case–control study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(3), 757–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09851-2

- Svensson, J., & Zetterqvist, M. (2019). Spel om pengar bland unga. [Youth gambling.] CAN Fokusrapport 03. CAN. https://www.can.se/app/uploads/2020/01/can-fokusrapport-03-spel-om-pengar-bland-unga.pdf

- Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. (2013). Problem gambling and the criminal justice system.

- Warfield, B. (2008). Gambling motivated fraud in Australia 1998 – 2007.

- Warfield, B. (2011). Gambling motivated fraud in Australia 2008 – 2010.

- Widinghoff, C., Berge, J., Wallinius, M., Billstedt, E., Hofvander, B., & Håkansson, A. (2018). Gambling disorder in male violent offenders in the prison system: Psychiatric and substance related comorbidity. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(2), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9785-8

- Zietz, D. (1981). Women who embezzle or defraud: A study of convicted felons. Praeger.