ABSTRACT

Recent political processes have rendered people with dementia an increasingly surveilled population. Surveillance is a contentious issue within dementia research, spanning technological monitoring, biomarker research and epidemiological data gathering. This paper explores surveillance in the relationships of people affected by dementia, how older relatives both with and without diagnoses are surveilled in everyday interactions, and the importance of expectations in guiding surveillance. This paper presents data from 41 in-depth interviews with people affected by dementia living in the community in the United Kingdom. Agedness was a key contributor to expectations that a person may have dementia, based on previous experiences, media accounts and wider awareness. Expectations provoked surveillance in interactions, with participants looking for signs of dementia when interacting with older relatives. Older people also enacted self-surveillance, monitoring their own behaviour. Various actions could be attributed to dementia because interpretation is malleable, partly vindicating expectations while leaving some uncertainties. Expectant surveillance transformed people’s experiences because they organised their own actions, and interpreted those of others, in line with pre-existing meanings. The ability to interpret behaviours to fit expectations can bring coherence to uncertainties of ageing, cognition and dementia, but risks ascribing dementia to many older people who straddle those uncertainties.

Introduction

Since its politicisation in the 1970s, dementia has garnered substantial notoriety (Beard, Citation2016; Fletcher, Citation2020a; Kueck, Citation2020). It has become the basis of considerable public and governmental anxieties (Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2016; Department of Health, Citation2015; Hillman & Latimer, Citation2017; Seaman, Citation2018) and a dedicated charitable and research industry (Alzheimer’s Research UK, Citation2017; Fletcher, Citation2019a, Citation2020b). Today, dementia is subject to unprecedented attention, transforming the nature of those affected. Historically disregarded by clinicians and publics alike (Beard, Citation2016; Fox, Citation1989; Lock, Citation2013), people with dementia are now hyper-visible. They no longer represent a bemusing consequence of ageing, as clinicians and publics once held, but instead manifest a modern epidemic filling newspaper front-pages (Brookes, Harvey, Chadborn, & Dening, Citation2018; Hillman & Latimer, Citation2017; Peel, Citation2014) and influencing election results (Oliver, Citation2018). In response to proliferating alarmism, a humanist scholarship has also emerged, refuting derogatory imaginings of dementia, and promoting personhood, citizenship and rights (Bartlett & O’Conner, Citation2010). Such significant alteration in a population’s status entails practical implications for its (potential) members, particularly regarding how they are approached by others. This paper seeks to address one such implication – surveillance within informal relationships. Ontologically, this paper approaches dementia as an experience of mental disorder with several explanatory models (e.g. senility, neuropathology, spirituality). No model is considered preferential here. The focus is participant interpretations rather than pre-existing models.

Surveillance – defined as heightened scrutiny of a population and associated problem(s) – has recently become a salient topic in several areas of dementia research. The most obvious regards assistive technologies in dementia care, revolving around the practicalities and ethics of monitoring people with dementia via technologies such as tracking devices (e.g. Niemeijer et al., Citation2010; Welsh, Hassiotis, O'mahoney, & Deahl, Citation2003). Much debate focuses on the rightfulness of monitoring people. Advocates argue that surveillance technologies can ensure the safety of vulnerable people in resource-limited care settings and reduce carer pressures. Critics contend that surveillance technologies undermine autonomy, privacy, dignity, trust and freedom, particularly when people are unaware that they are monitored, or monitoring is used to limit people’s movements (Mulvenna et al., Citation2017; Niemeijer et al., Citation2010). Kenner (Citation2008) positions proliferating dementia-related surveillance technologies within liberalist political economies that incentivise cheap technological means of maintaining older people in private residences to minimise ageing-related state expenditure. Kontos and Martin (Citation2013) further this analysis through a Foucauldian interpretation of surveillance as a means of controlling people with dementia deemed to threaten orderly society. Both approaches provoke broader questions regarding the political economic rationales underpinning surveillance, and whose interests it serves.

A second strand of work on dementia surveillance regards medicalisation and bringing older people under the medical gaze (e.g. Davis, Citation2004; Milne, Citation2010). Particular attention is paid to biomarkers and presymptomatic diagnosis, with debates regarding issues such as genetic screening (e.g. Bunnik, Richard, Milne, & Schermer, Citation2018; Frisoni et al., Citation2017; Swallow, Citation2017). This type of surveillance fundamentally reimagines dementia. Alzheimer’s has become an increasingly neuromolecular entity, defined less by cognition and more by biomarkers (Fletcher & Birk, Citation2019; Schneider & Viswanathan, Citation2019). This remaking of dementias requires dedicated technoscientific methods for discovering them, such as cerebrospinal fluid analysis (Frisoni et al., Citation2017). Proponents argue that knowing the likelihood of developing dementia allows people to plan for their futures, but critics contend that unreliable prognoses stoke fears and uncertainties (Bunnik et al., Citation2018; Swallow, Citation2017). Critically for this paper, recent turns to dementia prevention create large populations of older people who may unknowingly have neuropathologies years before the onset of symptoms, with only biomarker surveillance offering robust diagnoses (Leibing & Schicktanz, Citation2020).

Surveillance is also expanding via international epidemiological research projects, quantifying incidence to inform governance (Cahill, Citation2019; Cova et al., Citation2017; Prince et al., Citation2016). Advocates argue that population-level statistics will facilitate service planning and assessment, particularly in states where significant prevalence growth is predicted. Critics caution that low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) lack capacity for developing services, and resources supporting surveillance might be better dedicated to developing welfare provision (Prince et al., Citation2016). The spread of epidemiological dementia research into LMICs echoes the proliferation of global mental health initiatives. For example, the World Health Organisation’s (Citation2016) mhGAP-Intervention Guide is designed to increase detection and diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, including dementia, in LMICs. Critics contend that, by exporting dementia as a technical rather than epistemological issue, such tools impose select notions of dementia on LMICs, perpetuating colonial logics that justify extensions of Western expertise and control over non-Western peoples (Mills & Hilberg, Citation2019).

Each approach represents an understanding of dementia, those diagnosed and those who could be diagnosed, as warranting surveillance to mitigate risks, be that troublesome behaviours, personal susceptibility or service deficits. Throughout, dementia surveillance is cast as a political economic, technical and ethical issue. This paper identifies a different surveillance in the everyday interactions of people affected by dementia. This unsettles commonplace discussions of surveillance by revealing its encultured ubiquity in personal life, drawing attention to the micro-facets of surveillance. Symbolic interactionism is used to argue that this interpersonal surveillance is informed by situational expectations of ageing and dementia. It shows that expectant surveillance can be understood as imposing organisation on the uncertainties of ageing, cognition and dementia, and in doing so can transform the experiences of people affected by dementia. The concept of situational expectations is now outlined and situated within social dementia research.

Situational expectations

Since the 1990s, much social dementia research has been informed by symbolic interactionism (Fletcher, Citation2018), focusing on dementia as an interacted experience inhabiting interpersonal relationships (Bartlett & O’Conner, Citation2010). It encompasses work on personhood and person-centredness (Kitwood, Citation1997), selfhood (Sabat, Citation2001), embodiment (Kontos, Citation2004), dress (Twigg, Citation2010), identity (Beard, Citation2016), social experience (Brossard, Citation2019), moral careers and deviance (Fletcher, Citation2019b, Citation2019c, Citation2020c). Scholars have drawn on interactionism’s resonance with interpersonal meaning-making processes that shape dementia. Their works have influenced contemporary scholarship and care. Following this fertile tradition, this paper uses interactionism, specifically the concept of situational expectations, to elucidate interpersonal surveillance within families affected by dementia.

Goffman’s (Citation1974) Frame Analysis is used to explicate interpersonal surveillance under the influence of dementia’s symbolism. Frame analysis denotes a theory of social organisation through which interpersonal interactions guide people, their interpretations and their actions into loose alignment. This organisation is facilitated through meanings that are negotiated and shared by people when interacting. Shared meanings provide a rough blueprint for appropriate action in specific situations, whereby people can ‘assess correctly what the situation ought to be for them and then act accordingly’ (Goffman, Citation1974, p. 2). People draw on cues to recognise distinct types of situation, their unique characteristics and associated meanings. A situation is defined as ‘what one individual can be alive to at a particular moment’ – that which is immediately comprehended (Goffman, Citation1974, p. 8). People’s alertness to the associations between situations and meanings means that they know what to expect of a situation, how it typically plays out, how other actors will likely act and how they themselves should act. Goffman (Citation1974, p. 563) writes that people:

develop a corpus of cautionary tales, games, riddles, experiments, newsy stories, and other scenarios which elegantly confirm a frame-relevant view of the workings of the world . . . the human nature that fits with this view of viewing does so in part because its possessors have learned to comport themselves so as to render this analysis true of them.

Method

This paper presents data from interviews with people affected by dementia in the UK as part of a research project exploring their experiences of informal care. The project was approved by the Social Care Research Ethics Committee (reference: 16/IEC08/0007). A qualitative design was chosen in line with the study’s interpretivist focus on meaning-making (Gibson & Brown, Citation2009). The research sought to address: How are experiences of dementia influenced by situational expectations in informal care?

The sampling frame encompassed people diagnosed with a dementia, living in a private residence in the East Midlands, and the people they identified as their carers. Two participant groups were recruited – first, people with dementia and second, carers. Recruitment emails were sent to 782 local social organisations (e.g. churches, allotment associations – to avoid the over-representation of service users), generating a sample of seven people with dementia (for sampling limitations, see Fletcher, Citation2019d). These people were visited in their homes and assessed by the author under Mental Capacity Act procedures regarding participation, using the study information sheet and a capacity assessment recording tool developed by colleagues at King’s College London.

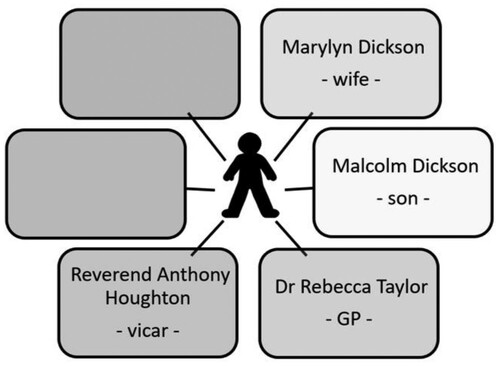

Once capacity provisions had been conducted, consultee advice sought (three participants lacked capacity upon assessment) and written consent gained, ecomapping was conducted with each person with dementia (Rempel, Neufeld, & Kushner, Citation2007). They were given blank A3 templates () and asked to incorporate the names and relationships of people who were important in helping them in their daily lives. This ecomapping method was adopted from nursing research to provide organic conceptualisations of care, which is often poorly operationalised in research (Fletcher, Citation2019e; Phillips, Citation2007). People identified through ecomapping were then recruited, mostly through main carers asking whether they were willing to participate and passing on contact information, generating an overall sample of 33 people affected by dementia. All identified carers were willing to participate. Two healthcare professionals could not be interviewed due to procedural ethics stipulations (see for participant details).

Table 1. ParticipantsTable Footnotea.

Following ecomapping and carer recruitment, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with each carer in order of importance, as specified by the person with dementia when ecomapping. This scheduling provided the interviewer with greater knowledge of each network before conducting a final in-depth interview with the person with dementia. All interviews were one-to-one, besides one couple interview at their request. All interviews were face-to-face in participants’ homes, besides one interview at the participant’s office. The topic guide covered experiences of dementia from initial symptoms until the present, focusing on relationship transformations. Questions included: When do you think you were first aware that [participant] might have memory problems? and ‘How did you decide to visit the doctor?’ These questions were designed to access participant perceptions of identifying and reacting to suspected dementias. The interviews lasted between 40 and 105 min. They were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

NVivo11 was used to aid manageability during thematic analysis of the transcripts. Analysis software’s speed and consistency render it systematic and more rigorous than manual analysis (Bowling, Citation2014). Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-stage thematic analysis enabled combined inductive and deductive analysis incorporating theoretical and organic codes (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). Analysis was conducted by the author alone, without the involvement of participants or other researchers, though the process was discussed with two supervisors. Third-party involvement in analysis was intentionally rejected due to its discordance with the study’s interpretivist epistemology (Morse, Citation2020; O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020).

Analysis began with familiarisation, wherein the author transcribed the interviews, reread the transcripts and relistened to recordings. The author then conducted primary coding, methodically applying descriptive labels to text segments. After two rounds of primary coding, the author organised these codes into themes, capturing code meanings within each. The author then tested the relevance of each theme to the dataset generally and select extracts through comparative evaluation. Once the themes were considered satisfactory, the author defined the relations between them. This paper presents themes and their relations, exemplifying each with examples from the data. Findings have been presented at several academic conferences and workshops to encourage critical appraisal and enhance credibility.

Two factors warrant reflexivity. First, the author has personal experience of informal dementia care, casting many interviews as insider exchanges, enhancing rapport. Second, the author is relatively young, positioning the author as an outsider whose personal experiences of age are removed from those of older participants. Both insider and outsider positions have benefits and drawbacks for research. Here, the insider-outsider position likely enriches and constrains the analysis somewhat idiosyncratically, as all researcher-data engagements do from an interpretivist epistemology.

Findings

Expectations of ageing and dementia

The meanings that most evidently informed participants’ situational expectations regarding dementia related to ageing and old age. Most participants spoke of ageing in relation to dementia, presenting cognitive decline as a typical characteristic of older people. Interactions with older people were hence imbued with expectations that they would show signs of dementia, irrespective of diagnoses. For some, the expectation that older people would develop dementia drew on previous experience. Michael, a dentist, spoke of his father’s Alzheimer’s disease in relation to his patients:

To me the easiest way of describing it is, ‘He’s just getting much older’. I’ve seen a lot of traits in him over the last two or three years that I’ve seen, I see elderly patients every day, and you see a lot of similarities . . . a way I often describe it, he just looks and acts much much older.

To be honest, old people I’ve known get old have pretty much all had it, so I guess it hasn’t come as much of a surprise. . . I would say that like it just kind of happens to all of us to an extent as you get old.

It seems to be all elderly people and I think now it’s becoming more and more apparent, which is basically what the paper was saying there, because everyone’s living to be older. Therefore, years ago, quite possibly, when people died at sixty, sixty five, seventy, dementia wasn’t really noticed and it certainly wasn’t given a title, just because so few people had it.

Overall, older people are partially expected to develop dementia due to their age. These expectations are evident in participant accounts. Our embeddedness within shared worlds of meaning regarding ageing and later life may beget perceptions of agedness as indicating the likelihood of several associated characteristics. This interpretive schema is informed by various sources, combining past experiences and media depictions to fashion roadmaps for future scenarios. The above examples reveal that dementia is one such characteristic associated with the ageing interlocutor – an expectation of situations involving interaction with older others.

Expectant surveillance

Situational expectations of dementia shape interactions because they are blueprints for anticipating others’ actions. They highlight which characteristics of an interaction warrant attention, and therefore encourage certain types of surveillance. This was most evident in participants’ accounts of diagnosis-seeking. Many carers first identified a relative’s potential dementia based on minute signifiers in line with expectations of an age-related condition. Awareness of associations between ageing and various conditions engendered age-based anticipation of decline. Consequently, subtle expectant surveillance arose, whereby family members maintained a slight watch over an ageing person’s behaviour to ensure that signs were promptly spotted. Lauren recalled monitoring her mother thus:

This had been in the back of my mind. We’re approaching the age that something was going to happen. There was some path that mother was going to travel, we just didn’t know which path it was. So I was keeping my eye out to see which way we were going.

Situational expectation is fundamentally a mechanism of generalisation whereby meanings can spread throughout interactions and be applied to similar situations (Goffman, Citation1974). Expectant surveillance can therefore expand within groups. One relationship can contract an aesthetic of expectant surveillance from another relationship with similar features. For Michelle, a combination of age-related expectations and experience with her father’s dementia led her to contemplate the likelihood of her mother developing dementia:

One thing I’ve been thinking about when I came today, that yes, he may have [dementia], but he’s ninety-two and if he’s got it, he’s got it late. I don’t know if there is an average age to get dementia, but it doesn’t surprise me at that age at all. . . It is an illness of older age generally speaking, so it wouldn’t surprise me if my mum got it either because of her age.

Do you look out for it in your mum, when you say you wouldn’t be surprised?

I guess I do now because he’s been diagnosed with it. She may be getting the early stages of it.

I’m getting on a bit as well now, so I sometimes wonder if I’m getting dementia as well.

Do you ever find yourself thinking about that?

I do yeah. I keep an eye on myself. I forget things and I do daft things occasionally.

These examples of surveillance based on situational expectations are principally concerned with the initial discovery of dementia, monitoring for the first potential signs. This surveillance is typically concerned with the prospective diagnosis should signs be discovered. However, surveillance is not limited to discovering dementia. Rather than being curtailed by diagnosis, expectant surveillance of people with dementia progresses to monitor decline. Such surveillance is grounded in situational expectations regarding the inevitability of decline in dementia. Jacob and Carl both described their expectations that their dad’s dementia would worsen:

Jacob: I assume, rightly or wrongly, that the dementia, that he’s on a slippery slope where he’ll get worse, and I guess the time will come when he can’t stay with mum, unfortunately.

Carl: If he went into a place where there was nursing there all the time then that would be awful, because he’s not that bad yet. So ironically, he has to get worse before we make that decision.

Tellingly, Brian’s sons articulated their expectations of decline in relation to future contingencies of care provision. Concerns about future care repeatedly motivated the sustained surveillance of people with dementia. This echoes ‘boundary-setting’ in informal care, whereby carers identify future circumstances when they seek institutional care (Fletcher, Citation2020c). Expected future events, e.g. night-time ‘wandering’, are typically used to signpost the right time for turning to institutional care. These findings suggest that surveillance is a mechanism through which these boundaries can be policed and enacted.

Malleable interpretation

As discussed, situational expectations rely on select attributes that are likely to be applicable to similar situations and actors within them. Herein, minute actions are attributed variable meanings – e.g. forgetting a name may be interpreted differently depending on whether the actor is aged 20 or 80. Situational expectations therefore inform our interpretations of people with whom we interact and how we act toward them. This is important because interpretation is malleable. The same phenomenon can be interpreted in several different ways and is likely to be attributed the meaning most aligned with the interpreter’s expectations. Any phenomenon can encompass various befitting actions. Crashing a car, burning a dinner or insulting a stranger, though highly dissimilar and easily attributable to several causes, may all be interpreted as indicating dementia if other situational parameters are conducive to that interpretation.

Interpretive malleability warrants some interrogation of the interpretive interlocuter’s role in dementia. Rather than simply identifying an actor’s pre-existing characteristics, interpretive interlocuters are involved in the emergence of those characteristics by surveilling for them and ascribing meanings. Most carers were aware that their perceptions might be questionable. Henry’s son, Michael, reflected on the validity of his family’s perceptions of his father’s decline:

Perhaps it’s our interpretation sometimes of how he is. Maybe he is perhaps more aware of things than perhaps we always think.

Interpretive malleability enables people to account for diverse actions via their expectations. Actions such as forgetting names can be readily interpreted as signs of ageing, dementia or other phenomena. Various interpretations are justifiable. One expects both older people and people with dementia to forget names. Extending this logic in a humorous manner, Peter noted of his forgetfulness:

As my wife may have said to you, she will ask something of me and I will be turning to her more often and saying, ‘What did you say?’ But of course, there’s always the fact that the husband never listens to the wife anyway

Do you find it easy to distinguish between his character and things attributable to dementia?

Yeah. He’s always been decisive. When he’s dithering about something, I know this is because of the dementia, he’s not quite sure which way to go. He’s slowly getting worse. It’s difficult to put your finger on but you’ll look at him and you’ll think, ‘You never used to do that’, or, ‘You didn’t used to be like that’. And he gets really obsessive. Like me knees, he was positive that once I’d had me knees done I’d be able to walk miles, rush about, and he was in for a nasty shock. And the ironing, he started doing it because I’ve had carpal tunnel, so I couldn’t lift the iron even. ‘It’s got to be done now’. And I’ll say to him, ‘Paul, just do a bit’. But no, it’s all got to be done. He gets obsessive that way.

Okay. And that’s the dementia?

Yeah, I’m sure it is because at one time if he wanted anything ironing he’d do two or three and then leave it, but not now.

Interpretational malleability cannot prevent interpretations of dementia occasionally being undermined. Participants’ interpretations were sometimes questioned, as this exchange with Paul and Janice exemplifies:

Does [forgetting people] put you off going out and seeing people?

It doesn’t put me off going out when I’m with Janice, but seeing people and not recognising them and not knowing them, I just let it go over me. . . I can go out there tomorrow, up to the church up the road where we go, and I see people in there who speak to me every week, don’t I, when we go in? But I can’t remember their names, and that’s from only a week ago. Janice knows them.

I don’t know their names.

Well there you go (laughs).

(Laughs) It’s one of those things where you go somewhere and you go regularly. It’s a coffee morning. We go and have a cup of coffee to help with the church funds. And they get to know you, and they’ll talk to you and ask how you are. Well, they know my name but I’ve no idea who they are.

Uncertainty and selection

Expectant surveillance is commonly vindicated by malleable interpretations of actions as indicating dementia. The influence of expectation is exacerbated by dementia’s uncertain ontological nature, wherein many older people could feasibly be considered to have dementia. Cognition generally declines with age from 20 to 30 onward (Salthouse, Citation2009), and neurophysiological characteristics of dementias occur in numerous older people (Aizenstein et al., Citation2008). Therefore, many older people exhibit pathological and clinical dementia characteristics, furnishing a large group of potential people with dementia. Indeed, two network members remarked that they could likely have their non-diagnosed mothers diagnosed with dementia were they to try. Expectant surveillance operates within these uncertain delineations of dementia vs. age-related cognitive decline.

A considerable population of older people occupies a fraught conceptual boundary between ageing and disease that can be difficult to navigate for even the most well-informed (Lock, Citation2013). This ambiguity is mirrored in the relationships of people affected by dementia. Many participants, with and without dementia, voiced concerns about uncertainties of dementia and ageing. Jacob discussed his difficulty ascertaining whether his father had dementia, and what this meant for diagnoses generally:

The most obvious issues around dementia were initially around memory, not remembering things. So is this just old age or is it dementia? I don’t know. Do we label old age with dementia now? I sometimes worry, especially with the situation with my mum and dad, whether it’s dementia or is it not just old age? Are we trying to label it these days with something? It’s difficult.

One of the difficulties, was when I knew this was coming on, or thought it was, was actually diagnosing which was actually unusual. Was it old age or was there something else there? Or was this just Brian being a bit more difficult than he’s always been?

Situational expectations help to provide answers by facilitating targeted selection, indicating what things should be looked for, and what those things likely mean. Mead (Citation1934) noted that selecting out important characteristics of an environment and attributing meanings to them is a foundational level of social organisation, imposing interpretive order on the world. Selection is crucial to everyday life. When crossing a busy road, the moving vehicles and the green light are important considerations, whereas the pigeon and the street vendor are inconsequential to the act. In such scenarios, people successfully act by selecting out salient characteristics of the environment.

Agedness is such a characteristic, selected as a meaningful feature of situations, repeatedly implicated in expectant surveillance. This selection of agedness engenders situational expectations denoting a specificity of interactions with older people – i.e. that those people are distinct in some meaningful sense – and enable audiences to presuppose likely characteristics of those older people. In this way, participants monitored older people’s actions and fitted them into pre-existing schemas of meaning. Uncertainties of the ageing mind were somewhat tamed, and expectations were vindicated by an evidence-base of malleable interpretations. These findings echo those of Seaman (Citation2018), who notes that family caregivers engage wider discourses of dementia to bring coherence to challenging personal experiences. Thus, making sense is a core practice of caring relations.

Recognising selection as organising experience is important for understanding dementia surveillance generally, raising questions regarding its motivations and outcomes. Swallow (Citation2017) notes that the pursuit of earlier and more widespread diagnosis manifests a broader transformation of ageing-related norms at the intersections of biomedical institutions and society. An interactionist account of situational expectations positions interpersonal interactions as a similar sort of interpretive surveillance work, through which people attempt to reconcile assumptions and uncertainties regarding ageing and dementia, rendering more coherent their experiences and potential futures. Dementia surveillance can hence be conceived as imposing order on disorderly phenomena – a way of making sense of challenging problems. Amidst the rush to surveil dementia, stakeholders should critically reflect on the expectations that guide surveillance, how readily surveillance satisfies its own expectations, and what that entails for dementia and those affected by it.

Conclusion

This paper has extended contemporary concerns regarding surveillance and dementia to incorporate everyday interpersonal interactions of informal relationships. Situational expectations have been shown to inform types of expectant surveillance, with expectations that can be fulfilled by malleable interpretations. Given the increasing surveillance of people with dementia, it is important to interrogate how situational expectations, and the tendency to select characteristics and attribute meaning to them, shape our relationships with older people with and without dementia. Future research could potentially investigate the therapeutic implications of interpretation and expectation, exploring whether different interpretative schemas can help or hinder wellbeing. As Lemos Dekker (Citation2020, p. 63) notes of dementia prognoses: ‘Anticipated suffering may become suffering in itself.’

While this paper principally outlines expectant surveillance within the everyday relationships of people affected by dementia, these processes have broader implications. An interactionist understanding of expectation reveals that surveillance can transform both its enactors and its targets, organising interpretation and action to align peoples’ experiences with pre-existing shared meanings. As more people find themselves straddling uncertain boundaries of ageing, cognitive decline and dementia, expectant surveillance can establish some coherence in the face of intractable challenges. However, the very act of monitoring this population ascribes meaning to them, and expectant surveillance can constrain certain outcomes, because when we seek we tend to find. This paper therefore highlights how historic societal trajectories of surveillance are echoed in the lives of people affected by dementia, revealing that their quotidian experiences are enmeshed in the broader social issue of surveillance, though not commonly recognised as such.

A trade-off emerges, between creating coherence and conflating old age with dementia. To navigate this tension, we must remain alert to how dementia surveillance is guided by expectations and has the potential to transform the relationships of those surveilled and those surveilling, and we must reflect on what we wish to achieve from our efforts to render it, and them, visible. This paper is not an attempt to ‘solve’ the ambiguities of malleable interpretation and expectation. Instead, it is an appeal for greater critical attention to surveillance as a generative practice in the everyday lives of older people and those affected by dementia. This is principally a call to researchers working in related areas, but it is also applicable to people affected by dementia, who might benefit from reflecting on how everyday surveillance influences their experiences. As Goffman (Citation1974, p. 381) observed of onlookers anticipating the fall of a clown: ‘Watching is doing.’

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Nick Manning, Karen Glaser, Rosanna Lush McCrum, Rasmus Birk and members of the GROW review group for providing helpful comments on earlier versions of this work. Disclosure of ethics: This research was approved by the Social Care Research Ethics Committee and the Health Research Authority, project reference 16/IEC08/0007. All participants with capacity gave written consent. All those lacking capacity under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 gave verbal assent and appropriate personal consultees advised that the person would wish to participate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aizenstein, H. J., Nebes, R. D., Saxton, J. A., Price, J. C., Mathis, C. A., Tsopelas, N. D., … Bi, W. (2008). Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Archives of Neurology, 65(11), 1509–1517.

- Alzheimer’s Research UK. (2017). Keeping pace: Progress in dementia research capacity. Cambridge: Author.

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2016). Five things you should know about dementia. Retrieved from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/five-things-you-should-know-about-dementia.

- Bartlett, R., & O’Conner, D. (2010). Broadening the dementia debate: Towards social citizenship. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Beard, R. L. (2016). Living with Alzheimer’s: Managing memory loss, identity, and illness. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Bowling, A. (2014). Research methods in health: Investigating health and health services (4th ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Brookes, G., Harvey, K., Chadborn, N., & Dening, T. (2018). “Our biggest killer”: multimodal discourse representations of dementia in the British press. Social Semiotics, 28(3), 371–395.

- Brossard, B. (2019). Forgetting items: The social experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Bunnik, E. M., Richard, E., Milne, R., & Schermer, M. H. (2018). On the personal utility of Alzheimer’s disease-related biomarker testing in the research context. Journal of Medical Ethics, 44(12), 830–834.

- Cahill, S. (2019). WHO's global action plan on the public health response to dementia: Some challenges and opportunities. Aging & Mental Health. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1544213

- Cova, I., Markova, A., Campini, I., Grande, G., Mariani, C., & Pomati, S. (2017). Worldwide trends in the prevalence of dementia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 379, 259–260.

- Davis, D. H. (2004). Dementia: Sociological and philosophical constructions. Social Science & Medicine, 58(2), 369–378.

- Department of Health. (2015). Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020. London: Department of Health.

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92.

- Fletcher, J. R. (2018). A symbolic interactionism of dementia: A tangle in ‘The Alzheimer Conundrum’. Social Theory & Health, 16(2), 172–187.

- Fletcher, J. R. (2019a). Destigmatising dementia: The dangers of felt stigma & benevolent othering. Dementia (Basel, Switzerland). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301219884821

- Fletcher, J. R. (2019b). Discovering deviance: The visibility mechanisms through which one becomes a person with dementia in interaction. Journal of Aging Studies, 48, 33–39.

- Fletcher, J. R. (2019c). Distributed selves: Shifting inequities of impression management in couples living with dementia. Symbolic Interaction. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/SYMB.467

- Fletcher, J. R. (2019d). Negotiating tensions between methodology and procedural ethics. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 62(4), 384–391.

- Fletcher, J. R. (2019e). A methodological approach to accessing informal dementia care. Working with Older Adults, 23(4), 228–240.

- Fletcher, J. R. (2020a). Mythical dementia and Alzheimerised senility: Discrepant and intersecting understandings of cognitive decline in later life. Social Theory & Health, 18(1), 50–65.

- Fletcher, J. R. (2020b). Positioning ethnicity in dementia awareness research: The use of senility to ascribe cultural inadequacy. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(4), 705–723.

- Fletcher, J. R. (2020c). Renegotiating relationships: Theorising shared experiences of dementia within the dyadic career. Dementia (Basel, Switzerland), 19(3), 708–720.

- Fletcher, J. R., & Birk, R. H. (2019). Circularity, biomarkers & biosocial pathways: The operationalisation of Alzheimer’s and stress in research. Social Science & Medicine. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112553

- Fox, P. (1989). From senility to Alzheimer's disease: The rise of the Alzheimer's disease movement. The Milbank Quarterly, 69(1), 58–102.

- Frisoni, G. B., Boccardi, M., Barkhof, F., Blennow, K., Cappa, S., Chiotis, K., … Hansson, O. (2017). Strategic roadmap for an early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease based on biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology, 16(8), 661–676.

- Gibson, W. J., & Brown, A. (2009). Working with qualitative data. London: SAGE.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organisation of experience. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

- Hillman, A., & Latimer, J. (2017). Cultural representations of dementia. PLoS Medicine, 14(3), e1002274.

- Kenner, A. M. (2008). Securing the elderly body: Dementia, surveillance, and the politics of “aging in place”. Surveillance & Society, 5(3), 252–269.

- Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The persons comes first. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Kontos, P. C. (2004). Ethnographic reflections on selfhood, embodiment and Alzheimer's disease. Ageing & Society, 24(6), 829–849.

- Kontos, P., & Martin, W. (2013). Embodiment and dementia: Exploring critical narratives of selfhood, surveillance, and dementia care. Dementia (Basel, Switzerland), 12(3), 288–302.

- Kueck, L. (2020). A window to act? Revisiting the conceptual foundations of Alzheimer’s disease in dementia prevention. In A. Leibing & S. Schicktanz (Eds.), Preventing dementia? Critical Perspectives on a new paradigm of preparing for old age (pp. 19–39). New York, NY: Berghahn.

- Leibing, A., & Schicktanz, S. (2020). Introduction: Reflections on the “new dementia”. In A. Leibing & S. Schicktanz (Eds.), Preventing dementia? Critical perspectives on a new paradigm of preparing for old age (pp. 1–16). New York, NY: Berghahn.

- Lemos Dekker, N. (2020). Timing death: Entanglements of time and value at the end of life with dementia in the Netherlands. Amersfoort: Alzheimer Nederland.

- Lock, M. (2013). The Alzheimer conundrum: Entanglements of dementia and aging. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Mills, C., & Hilberg, E. (2019). ‘Built for expansion’: The ‘social life’ of the WHO's mental health GAP Intervention guide. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(S1), 162–175.

- Milne, A. (2010). Dementia screening and early diagnosis: The case for and against. Health, Risk & Society, 12(1), 65–76.

- Morse, J. (2020). The changing face of qualitative inquiry. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920909938

- Mulvenna, M., Hutton, A., Coates, V., Martin, S., Todd, S., Bond, R., & Moorhead, A. (2017). Views of caregivers on the ethics of assistive technology used for home surveillance of people living with dementia. Neuroethics, 10(2), 255–266.

- Niemeijer, A. R., Frederiks, B. J., Riphagen, I. I., Legemaate, J., Eefsting, J. A., & Hertogh, C. M. (2010). Ethical and practical concerns of surveillance technologies in residential care for people with dementia or intellectual disabilities: An overview of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(7), 1129–1142.

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Oliver, D. (2018). Will we now see a serious attempt to tackle social care funding? BMJ, 360, k136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k136

- Peel, E. (2014). ‘The living death of Alzheimer's’ versus ‘take a walk to keep dementia at bay’: Representations of dementia in print media and carer discourse. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36(6), 885–901.

- Phillips, J. (2007). Care: Key concepts. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Prince, M., Ali, G. C., Guerchet, M., Prina, A. M., Albanese, E., & Wu, Y. T. (2016). Recent global trends in the prevalence and incidence of dementia, and survival with dementia. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy, 8, 23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-016-0188-8

- Rempel, G. R., Neufeld, A., & Kushner, K. E. (2007). Interactive use of genograms and ecomaps in family caregiving research. Journal of Family Nursing, 13(4), 403–419.

- Sabat, S. R. (2001). The experience of Alzheimer's disease: Life through a tangled veil. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Salthouse, T. A. (2009). When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiology of Aging, 30(4), 507–514.

- Schneider, J. A., & Viswanathan, A. (2019). The time for multiple biomarkers in studies of cognitive aging and dementia is now. Neurology, 92(12), 551–552.

- Seaman, A. T. (2018). The consequence of “doing nothing”: family caregiving for Alzheimer's disease as non-action in the US. Social Science & Medicine, 197, 63–70.

- Swallow, J. (2017). Expectant futures and an early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Knowing and its consequences. Social Science & Medicine, 184, 57–64.

- Twigg, J. (2010). Clothing and dementia: A neglected dimension? Journal of Aging Studies, 24(4), 223–230.

- Welsh, S., Hassiotis, A., O'mahoney, G., & Deahl, M. (2003). Big brother is watching you – the ethical implications of electronic surveillance measures in the elderly with dementia and in adults with learning difficulties. Aging & Mental Health, 7(5), 372–375.

- World Health Organisation. (2016). mhGAP Intervention Guide – version 2.0. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/mhGAP_intervention_guide_02/en/.