ABSTRACT

There are numerous ways that researchers can creatively approach social research and translation. This article discusses elements from the first stages of a novel project that centres social research translation in the form of a public exhibition. ‘Creative Approaches to Health Information Ecologies’ is a project by a multidisciplinary research team in collaboration with an Australian health consumer organisation. The project uses creative workshop methods to explore how people learn, think, and feel about their bodies and health states, and brings attention to the significance of communities, places, spaces, objects, and other living things – the ‘ecologies’ of health information. It then builds on these insights to create an interactive exhibition of materials designed for public engagement. This reflexive article unpacks how this creative translation-centred collaboration contributed to the make-up of the project team, the project's research methods, and the process of making exhibition materials. We discuss what the research team learned from the process about creative collaboration, research-creation, and research translation.

Introduction

There are many ways to establish collaborative research projects with community partners. Research translation is often highlighted as a core aim, yet can become an underserved process in the early stages of project work. In this article, we discuss our experience of establishing an innovative collaborative project that centres creative research translation in the form of a public exhibition. Our project, ‘Creative Approaches to Health Information Ecologies’, undertaken with an Australian health consumer organisation, explores the contemporary ways people learn about their bodies and health states. It brings particular attention to the significance of communities, places, spaces, objects, and other living things – the ‘ecologies’ of health information. The project explores what matters within people's health information ecologies through a series of creative workshops and builds on these insights to create an interactive exhibition.

In this article, we share our reflexive process (cf. Bleakley, Citation1999) of centring creative research translation and public engagement within the critical first stages of establishing the project. This includes: (i) the project development stage; and (ii) online workshops exploring how people understand and engage with health information. In progress at the time of writing is: (iii) the exhibition design and making stage. Future stages include: (iv) in-person exhibition visits for evaluation of the materials; and (v) the final staging and public presentation of the exhibition. By discussing this project-in-progress, we aim to contribute to the body of literature on effective, inclusive, and accessible research translation and the ways that these activities can extend the methods and purview of social inquiry. In what follows, we overview our project and the key concepts on which we are drawing. We then outline our process for establishing the project team with our collaborator Health Consumers New South Wales (HCNSW), and our approach to developing the project design with them. In our discussion, we reflect on translating and materialising insights from the first round of workshops into the creation of our exhibition materials. We consider how this collaboration contributed to our project from the early stages, and what we learned from the process about creative collaborative research and research translation.

Project overview

‘Creative Approaches to Health Information Ecologies’ rests on the standpoint that human health is entangled with planetary health. Our project is located in a large research centre, the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society (ADM + S). However, we adopt a more-than-digital approach, seeking to depart from the notion that digital devices and medical record-keeping systems are the most valued ways of generating information about human health and wellbeing. We go beyond the typically human-centric approach adopted in digital health, acknowledging that people are always imbricated within networks of more-than-human worlds which can include digital technologies, but also many other things (Lupton, Citation2019). There are two main objectives we wish to accomplish with the project: (i) to expand the notion of health information beyond that of digital data; and (ii) to sensitise people to their interembodied relationships within planetary health ecologies. We want to explore how people can become better attuned to these powerful and vibrant relationships. The title of our project – ‘Creative Approaches to Health Information Ecologies’ – gestures towards these entanglements and interests.

Underpinned by theoretical concepts from more-than-human theory, the project's findings will contribute to a public exhibition that focuses on the human-nonhuman relations of health and wellbeing. Bringing an iterative pedagogical dimension, with this exhibition, we aim to stimulate visitors’ awareness of their deep connections with the environment and their role as custodians. We want to highlight the relationship between how people engage with digital forms of information about their bodies and the manifold, multisensory ways that they learn about and promote their health and wellbeing through their encounters with nature. To achieve these objectives, this project engages with health sociology and several other subfields including environmental, digital, and design sociology. We are also inspired by work in embodied and sensory pedagogies; information studies; research-creation inquiry; participatory artmaking; arts-based approaches to personal data and information; and the use of public exhibitions for research and translation. Our research questions are as follows:

What kinds of health information do people use and why? What forms does this information take?

What marks does life leave on peoples’ bodies? What do these marks tell us and mean for us?

What do people observe, sense, make, and document about themselves with digital technologies? How do these help people think about their role and place in the planetary ecosystem?

What do people observe, sense, make and document about themselves with non-digital things? How do these help people think about their role and place in the ecosystem?

How do people draw on these modes to make connections between planetary health and human health?

How do people engage with creative works about health information? What do creative works make people think, feel, and sense about their own health and the health of the people and world around them?

We explore these questions through creative workshops and the development of an interactive exhibition as a mode of research translation. Using a range of materials – novel artworks, interpretation panels, a film, and hands-on activities – we will invite people to consider how they learn about their bodies and states of health and illness and engage in more-than-human practices of wellbeing. We view translation as the generation and distribution of knowledge between researchers and publics: a dynamic process that is continually iterating as we learn from our interlocutors, and they learn from us. As we detail below, we have designed this project to incorporate findings from our creative workshops into our materials making and ideation processes. In turn, we aim to use these materials as a way of conveying meaning and inspiring new multisensory and affective engagements with publics. As such, we are using the exhibition both as a research translation mode and as a mode of research (Bjerregaard, Citation2019). Our project was carefully designed to include community members at crucial stages of the development of the exhibition, which will be made available for view in community spaces.

Literacy, knowledge translation and health sociology

Activities under the rubric of ‘research translation’ are often associated with those concerning ‘health literacy’. Most studies in the body of work in health literacy focus on individual skills and competencies, using structured questionnaires and measurement tools to discern how well people can find, understand, and use information to engage in problem solving for their own health (Levin-Zamir & Bertschi, Citation2018). This rationalist orientation tends to strip out the materialities, multisensory responses, and affective forces that we see as crucial to health pedagogies. Our approach to health literacy adopts a distinct perspective, drawing on sociomaterial understandings of health and illness in what has been described as ‘more-than-human health literacy’ (Lupton, Citation2021). Expanding beyond human-centrism, our approach involves attuning to our role in planetary ecologies and the complex connections of human health with the environment (Braidotti, Citation2019; van Dooren et al., Citation2016). There are strong intersections in this approach with perspectives in environmental pedagogies (Muhr, Citation2020; Welch et al., Citation2021). Such scholarship emphasises the importance of highlighting the embodied, emplaced, affective, and multisensory dimensions of human/planetary health.

Our conceptualisation of health ‘information’ is also related to our more-than-human standpoint. In the usual health literacy approach, ‘information’ is understood as facts or data about people's health and illness states that are derived from sources, such as medical advice, medical records, self-help literature or online search engines, platforms, and apps. With the proliferation of digitised ways of producing information about health and illness (Fotopoulou & O’Riordan, Citation2017; Lupton, Citation2019), the literature on health information sources now often refers to digital forms of ‘health data’. There is a growing body of research in the health literacy domain investigating how health data are generated through online interactions or use of apps and wearable devices for self-tracking, and how effectively people engage with and understand these data (Griebel et al., Citation2018). Assumptions about disembodied thought and the immateriality of information shape much of this research (Fotopoulou & O’Riordan, Citation2017; Lupton, Citation2019). By contrast, some scholars in information literacy and information studies position information and digital data as emplaced material things (Orlikowski & Scott, Citation2015) with an affective and sensory force in embodied information practices (Olsson & Lloyd, Citation2017). Our approach similarly positions these phenomena as constantly changing more-than-human multisensory assemblages, coming together and apart with the diverse array of objects, other humans, and other living things (Lupton & Watson, Citation2021). We argue that people ‘feel’ their health data, in affective and sensory responses (Lupton, Citation2017). It is with and through their bodies that people engage in information sensemaking.

These expansive approaches to health literacy and health information offer opportunities for expanding the possibilities of research translation. They focus on effective communication of research findings to publics and stakeholders outside the university, the development of economic benefits, or contributing to policy development or procedural change in the health and medical sector. For Searles et al. (Citation2016), research translation is a prerequisite for research impact. They reference ‘flows of knowledge’ (p. 2) in considering the pragmatic ways that new understandings of health or medical phenomena might be best conveyed in applied domains. Knowledge translation literature that focuses on health inequalities and intersectionality has strong resonances for sociological perspectives. A generative example comes from Kelly et al. (Citation2021) who reflected on the importance and tensions of bringing the work of black feminist scholars on intersectionality into dialogue with health research and gender studies. Their approach to knowledge translation builds on a radical and activist history. They emphasise the dissemination and exchange of knowledge as a process rather than an outcome, arguing the need for ethically sound applications that can improve the health of underserved or excluded social groups.

Research-creation, data art and design sociology

Bringing arts-based methods into an intersectional and social justice-oriented approach can open vibrant ways for participants to creatively express their feelings and embodied, sensory dimensions of their health states and encounters with the healthcare system. Social researchers have used methods such as photovoice (Macdonald et al., Citation2021), digital storytelling (Lenette et al., Citation2015), sculpture, installation, and painting (Hogan, Citation2021), as well as creative writing, such as story completion and poetry (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2021; Lupton, Citation2021). With these approaches, researchers encourage participants to render their experiences more visible and share personal experiences that challenge sexism, racism, stigmatization, and marginalisation. The creative artefacts participants make can themselves be used as translation materials, useful for disseminating findings in ways that bring research alive, beyond the traditions of academic books and journals. This approach aligns with that of ‘research-creation’, where qualitative inquiry is conducted with more-than-human theory and creative making. Such scholarship highlights the role of co-researchers in research translation and the lively resonances of research artefacts, including how these come to matter in people's lives (Lupton & Watson, Citation2021, Citation2022; Manning, Citation2016; McLeod & Fullagar, Citation2021; Renold & Ivinson, Citation2022).

Our project is informed by creative approaches to working with data. Since the 2000s, artists and academics have explored how digitally fabricated objects can produce novel insights into data (Zhao & Vande Moere, Citation2008) and function as aesthetic artefacts and artworks (Whitelaw, Citation2012). Moreover, our project draws from the sustained interest in data within contemporary art and the broader history and practices of participatory art. Since the 1960s, artists have used participation as a way of actively implicating the audience in the production of the artwork. Initially, participatory art focused on empowering specific marginalised communities, elevating their perspectives, and dissolving the historic valorisation and ‘romantic persona’ of the singular artist (Bishop, Citation2012, p. 232). More recently, similar approaches have been used by artists and designers to engage with data. As D’Ignazio and Klein (Citation2020) discussed, effective participatory projects involve communities to explore how they live and might engage with their urban data for local social good. In projects such as the urban farm collaboration between Groundwork Somerville and Rahul and Emily Bhargava (D’Ignazio & Klein, Citation2020, pp. 142–144), digital data are creatively brought into dialogue with their socio-spatial and political contexts. Community members reflect on the relation between their personal data and lived experience, then create painted data murals and other public artworks. This creative collaborative process and resulting site becomes ‘a kind of campfire’ for information exchange and the cultivation of community, a material vehicle for solidarities and building a ‘sense of collective agency’ (p. 145).

We were inspired by these artistic practices in designing our project, as well as the exhibition as a discursive space. We view our exhibition as aligning with the perspective of exhibitions as research, which positions the curation and presentation of materials as ‘knowledge-in-the making’, rather than the presentation of fixed meanings (Bjerregaard, Citation2019). Design sociology underpins the makeup of our academic team and anchors the approach of the project. This does not (only) refer to sociological research on design, but ‘with and through design’ (Lupton, Citation2018). Design sociology combines methods from both disciplines to develop a multidisciplinary project in mutually enriching directions. This collaborative approach can be especially useful in projects with an object focus, such as a study of specific technological devices, or those using a more-than-human conceptual approach. Adopting a design sociology approach can help centre the production of scholarly and creative outputs that invoke. Adopting a design sociology approach can help centre the production of scholarly and creative outputs that invoke participatory, playful, generative, and interactive audience engagements throughout a project lifecycle. By using a design sociology approach we are working to contribute knowledge in the visual arts, museum curation and sociological research contexts. In creating an exhibition as our mode of display and communication, we were inviting our partner and visitors to be an active part of our research creation.

Project design: the team

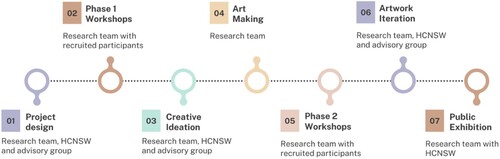

Our ‘Creative Approaches to Health Information Ecologies’ project involves participatory design and collaboration throughout various stages, as illustrates. In what follows, we detail how these relationships developed and informed the project design from the early stages of its conception.

Bringing together a multidisciplinary team

Our academic team draws together expertise from sociology with art and design. This project builds on our respective prior works: sociological studies of how people engage with personal data for their health and fitness (Lupton, Citation2019), for the future (Lupton & Watson, Citation2022), and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Watson et al., Citation2022); design-based research on the aesthetics of GPS and other drone-produced data (Wozniak-O’Connor, Citation2018, Citation2020); and media arts explorations of materialising data from wearable devices into sculptural art works by combining natural, artificial, and electronic materials (Wozniak-O’Connor, Citation2017). The initial concept for the project was created by our team, building on the intersections of these varied projects. We then worked with our community partner to further develop and shape the project approach.

Working with a community partner

Our community partner HCNSW, is an independent not-for-profit organisation and registered health charity representing over 200,000 people across the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW), including those living in rural communities. As its title suggests, HCNSW focuses on promoting the rights and voices of health consumers from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds in public debate and policy concerning healthcare. Its website outlines its mission as follows: ‘HCNSW represents the interests of patients, carers and their families in NSW. We believe in shaping a health system that listens to, respects, partners with and values health consumers’ (see hcnsw.org.au). As this wording demonstrates, this organisation takes a directly advocative and inclusive approach to consumers of healthcare, adopting an approach that has been central to patients' rights movements in Australia and elsewhere since the 1970s (Lupton, Citation1997). Patients, carers, and their families are invited to take an active role in their health and healthcare provision. HCNSW provides advice, training, and resources, including offering lay people the opportunity to represent health consumers in advisory roles and participate in research. Given this focus, HCNSW was keen to partner with us on our project and we welcomed their expertise and guidance. By developing a framework that encapsulates yet broadens beyond the digital aspects of ‘health data’, we worked to design a project sensitive to the varied environments and relations that matter in how people learn about, feel, and sense their health and wellbeing.

Through several relationship-establishing meetings with representatives from HCNSW, we focused on identifying areas of shared interest and avenues for collabora- tively, developing our initial project concept into a fully-fledged project, formulating some guiding aims and principles. This was the beginning of our cooperative research translation relationship. HCNSW staff have diverse backgrounds related to health, including in research. As they articulated to us, when collaborating on academic studies, they bring methodological expertise in participatory approaches with health com- munities, as well as extensive experience breaching the gap between medical pro- fessionals' knowledge and the lived experience of healthcare consumers. In initial meetings, we discussed their priorities in these areas and how these inflect what HCNSW needed and wanted to know about emerging technologies and data in healthcare domains. HCNSW outlined the forms and styles of outputs that they find valuable for their large consumer community, such as traditional project reports and academic journal articles, as well as the generative potential of creative and artistic works. These included: centring the lived experiences and expertise of health consumers; making the study accessible in terms of methods of data collection and the language used to introduce and explain the study; and enabling health consumers to be involved in research processes, drawing on models, such as co-design or citizen science research.

These priorities identified with HCNSW bore out in several critical initial decisions concerning the design of our project. Importantly, this included changing the project language from health ‘data' to health ‘information'. As discussed in our previous research (Watson et al., Citation2022) and also conveyed to us by the HCNSW team, drawing on their professional experience, the term ‘data' has directive connotations. It is usually interpreted as involving technically complex processes of analysis and comput- ing that require specialised learning or training to understand and engage with. As we explained earlier, our more-than-human approach focuses on the many varied digital and non-digital forms that data take. This includes how digital data are generated and engaged with in various contexts, but importantly, also includes sensory, embodied, and material forms: marks on the body; feelings; sounds; scents; as well as details relayed in conversations or gauged from practices and environments. We are interested in these varied modes of data as they are made and imbricated in the objects and activities of people's everyday lives. However, knowing the common contemporary implications of the term, we discussed how a project on ‘health data’ might limit the pool of potential participants to those who feel au fait with the complex landscape of digital datafication, excluding those for whom these phenomena feel abstruse or obscure. ‘Information’ seemed a more general term that better aligned with how we wished to approach ‘data’.

Other key project design decisions, which were guided by our preliminary consultations with HCNSW, included hosting the first phase of data collection online in the form of one-hour online workshops with small groups of participants, to more easily and cost-effectively enable the participation of people from across the state of NSW. We also decided to establish an advisory group for the project to guide its development, as we detail in the following section. This approach was agreed upon as an effective and collaborative alternative for a project of this scale.

Establishing an advisory group

We established an advisory group to help ensure the project was informed by health consumer representatives' expertise on how research might be inclusive of lived experience. The group's aim was to aid in the successful completion of the project and foster collaboration between consumers and researchers on the meaning of health information. The group offered a space and structured process for key project members and stakeholders to openly discuss the project design as it unfolded. The group ensured that the project was guided by current research, contemporary issues in the sector, and health consumers’ lived experiences with health and medical information. We intentionally drew on several perspectives and positionalities to collaboratively workshop important elements. In consultation with HCNSW, we determined that three health consumers would be invited to join the advisory group, selected via an expression of interest process, along with two researchers from the academic team and a representative from HCNSW. These meetings were held online and planned to last for approximately two hours each. The health consumer representatives of the advisory group were not expected to contribute time beyond their participation in these meetings and were remunerated in line with the Classification and Remuneration Framework for NSW Government Boards and Committees.

The consumer representatives who joined the advisory group have significant experience working with consumer councils and health and community services across NSW. This includes advising on health policy, advocacy, ethics committees, social research, and clinical trials, and representing and working with various communities including Indigenous Australians, people living with cancer and chronic illnesses, and people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Meetings of the group were planned to inform three key moments of the project. An initial meeting during project design, before and in support of submitting a university ethics application, served to introduce the consumer representatives to the project. In this meeting, the group discussed and refined the project research questions, target participant sample, research methods, and study advertisement materials. A second meeting followed the completion of the first set of workshops and early prototyping of the exhibition materials. In this meeting, the advisory group offered their reflections on emerging research findings, which were anonymously reported by members of the research team at a broad thematic level, and how these might be best presented for a public audience. In this meeting, the group also discussed how the exhibition materials could be refined and exhibited in accessible and inclusive ways. The third meeting, in support of finalising the public exhibition, provided advisory group members the opportunity to provide feedback on the exhibition design and dissemination strategies.

Through these meetings, advisory group input on project design helped us to develop several elements that enhanced the accessibility and inclusivity of the study and ensured we would be sensitive to participants' concerns, interests, and experiences. These discussions on recruitment processes and the technical and conceptual aspects of the research, had meaningful ripples across the project, which we saw in the experiences participants shared in workshops and represented in their creative materials. We highlight these in the following discussion on our methods.

Project design: generating research materials

Research in our ‘Creative Approaches to Health Information Ecologies’ project involves two phases of workshops. Phase 1 has been completed at the time of writing. In this section, we focus on how we designed these workshops to research health information, and we reflect on how the collaborative relationships described above contributed to our project design.

Developing the project design

We developed our project design and prepared for a university ethics application through a collaborative process involving several meetings between our multidisciplinary research team and HCNSW, and via meetings of the advisory group. As a research team, we have extensive experience with using creative qualitative methods (Lupton & Watson, Citation2021, Citation2022). In first conceptualising the study and meeting with HCNSW, we saw potential for this approach in this project. HCNSW dedicate much of their efforts to connecting and sustaining meaningful networks, panels, and communities of health consumers. We sought to develop an approach that echoed their efforts to establish channels for people to communicate and connect around relevant issues, including health information. Many of the people that our recruitment would reach via the organisation are experienced in and already receiving information on collective opportunities invol- ving other health consumers. We therefore, anticipated that a group-based form of participation might be familiar and desired by many within the HCNSW network.

Creative workshops are valuable for generating multiple research materials, including audio/video recordings, transcripts, and materials produced by participants via activities and small group discussions. The research collection process and resulting materials can vividly manifest shared understandings, resonances in meaning, and affective consensus among a group, as well as the distinct subjectivities and diverse experiences of those in the session (Lupton & Watson, Citation2022). Creative workshops are also a familiar method across sociology and art and design. Our workshops sought to surface how people learn about and monitor their health and wellbeing using multisensory engagements with more-than-human agents. Using a research-creation approach, we sought to develop a workshop that blended discussion around semi-structured questions and the completion of creative, imaginative activities that stimulated our participants to ‘think otherwise’ about what ‘health information’ might be. In cross-team and advisory group meetings, we spoke about our experiences with using similar workshop methods (see Lupton & Watson, Citation2022) and why we felt that a synergy of discussion, written, and visual-based engagements would effectively address our research questions. Namely, workshops centrally involving a pen-and-paper activity plus a shorter discussion around prompt materials would allow time for personal reflection and discussion, as well as two different stimuli: a blank page with brief instructions to create something themselves, and some vivid images or other selected stimuli to elicit group discussion.

Discussions about this methodology with HCNSW and the advisory group led to several design choices, changes, and additions that meaningfully enriched the project and helped us to attend to the consumer view of how a project, such as this, might be received. These changes included clearly outlining in the participant information sheet and other recruitment materials, that participants could use various modes to complete activities, depending on their accessibility requirements and preferences. We were therefore able to ensure we were not limiting participation; for instance, by requiring or only suggesting a pen and paper. Another helpful suggestion raised by the advisory group related to making a video to accompany recruitment documents, such as the participant information sheet. This allowed us to put our faces to the project, introducing and humanising members of the research team beyond an email or letter signature in a short and simple introductory clip, filmed on our laptops and smartphones.

A final point of discussion amongst the advisory group that contributed to the development of the project related to how to approach the embodied and affective dimensions of our methods with care. In seeking to go beyond digital data and explore how people sense and feel information about their health and wellbeing, we wanted to create a space in which participants could feel safe in sharing their embodied experiences, on the traces and marks that health experiences can leave. We also wanted to generate opportunities for participants to connect these feelings and experiences with places, by incorporating an image association task for reflective or symbolic responses. As raised in an advisory group meeting, while such activities are important to research, and participants are often eager to share their experiences, these creative approaches are not exclusive to novel social research. They are also common arts–based therapy techniques (see Hogan, Citation2021; Malchiodi, Citation2018) with which participants may be familiar or find difficult, especially if these activities are quickly wrapped up, once the allotted hour is reached. To open lines of communication, we included details in our participant information sheet that encouraged participants to contact a designated member of the research team with any questions or additional comments they might have or to have a private debrief following the workshop. To avoid a ‘cold close’ to the session, we also verbally reiterated these details at the conclusion of each workshop and via a personal follow-up and thank-you email.

Facilitating creative workshops

Once we had gained university ethical approval for the project, HCNSW circulated information about the study, including a link to watch our recruitment video, via their established communication channels including email newsletters and social media. Those who were interested, contacted a member of the research team directly. Once they had given their consent to participate, were scheduled into a workshop session. Each workshop was convened by two members of our team. The workshop began with us providing a general introductory discussion of the project, the associated requirements, and the expectations of participation. Participants were given the opportunity to ask any questions or clarify aspects of the workshop before the video–recording was enabled. Each person present was then invited to introduce themselves, and the first activity was commenced.

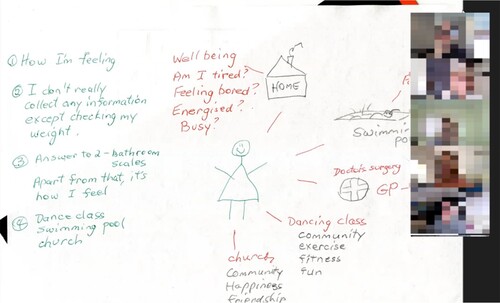

Activity 1: health information ecology mapping

Participants were asked to use their pen and paper or digital program to create a personal ‘health information ecology’. We asked participants to make a map showing a human body in the centre (e.g. stick figure) in one or more environments (e.g. places, buildings, nature) labelled with health information (e.g., types of information, where information comes from and goes, objects, people, senses related to health). We explained that this map represented the people, places, and things that matter to them about health information, or how they find, feel, sense, and learn information about health.

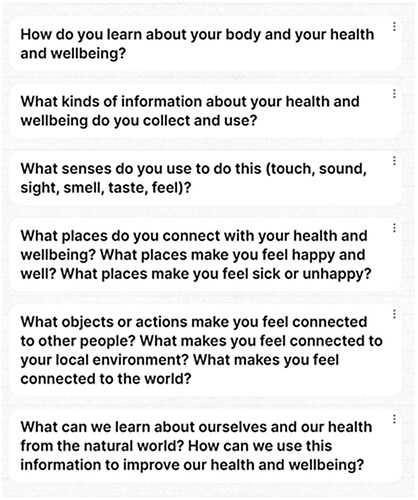

This activity builds on body mapping and hand-drawn mapping techniques. In visual research and research translation initiatives, the body mapping method has been used to give voice and shape to embodied experiences and feelings, often with social justice or therapeutic orientations. It typically involves tracing participants’ body outlines on a large sheet of paper or cloth, so that they can then work with their life-sized shapes to use paint or other forms of mark–making to depict aspects of their bodies and the affective responses they sense and feel within themselves (De Jager et al., Citation2016). Our approach adopts a different orientation. Similar to other hand-drawn mapping activities we have conducted in previous research (Watson & Lupton, Citation2022), it centres the individual's body as part of a complex and dynamic ecosystem of more-than-human entanglements and relational connections. To facilitate this perspective among the participants drawing their maps, prompt questions were shared on the screen ().

Participants were given approximately 10 minutes to complete the task before joining in group discussion about the activity. We reiterated that participants did not need to write answers to these questions but could use them to inspire details in their maps. We designed this activity to visualise and inspire connections and parallels between how people learn, feel, and sense information about their personal health with the health of their communities and environments. After completing their maps, participants shared what they had created by holding it up to their cameras, screen-sharing, and/or talking through the details (see ). This portion of the workshop typically lasted between thirty and 45 minutes.

Activity 2: new health information metaphors

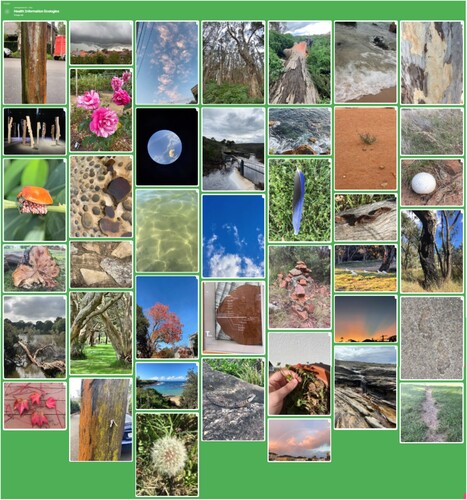

Following discussion of their personal health information ecologies, we commenced the final part of the workshop involving the ‘new health information metaphors’ activity. Building on the premise of Lockton et al. ‘New Metaphors Toolkit’ (Citation2019), we used the Padlet digital platform to curate and present participants with a series of approximately forty photographs taken by members of the research team, featuring living things or nature spaces (or marks left by living things), such as waterways, the sky, trees, fallen leaves, and footprints (see ). Photographs were selected to elicit impressions, memories, and symbolic connections that built on the information ecologies that participants had mapped or that might have yet been immaterial in the session.

Participants were asked to select and discuss images that drew their attention, that they could relate to health information in some way. The research team member who lead the session offered three examples: ‘health information is like this tree, the marks in the bark remind me of…' or ‘learning about my health is like this river; you can see…' or ‘feeling well (or feeling unwell, or feeling my body) is like the sky, because it's… ’. In explaining the task, we stressed that there were no wrong answers; this was a creative free association task to explore some different ways that we might think about and talk about health information. The participants’ explanations revealed how they understand and creatively connect information about their health with various material things in their everyday environments. Discussion of this activity lasted until the towards the end of the workshop.

The creative workshop methods we designed, of mapping and exploring image-inspired metaphors, generatively departed from the usual verbal and literal ways we talk about health information. With these methods, we connected with participants to elicit how they sensed and felt their bodies and health states, and what mattered to them, personally. With the mapping activity, for example, we engaged participants to locate and relate the often-abstract notions of information and data with the everyday places, people and things in their own lives. We discussed the places in which participants spent time, who they talked to, what objects and technologies they used, and the connections between these phenomena that related to their own health states. The relation between people's local environments and how they sensed (and make sense of) their health, an emergent theme in the mapping activity, resonated strongly in the image–based metaphors activity that followed. Largely, the participants conceived health information in parallel to the rich sensory experiences associated with good health, such as exercising and spending time in natural spaces. For many participants, the second activity elicited poetic and conceptual connections between human and planetary health beyond the more literal discussions of local environments in which they enjoyed spending time. Images of trees, for example, spurred discussions of growth and time; images of the ocean opened conversations about change and the indicators of cycles between good and ill health.

Discussion and concluding comments

In this article, we have shared our reflexive process of centring creative research translation within the critical first stages of establishing our ‘Creative Approaches to Health Information Ecologies’ project. Discussing the project development stage and the first phase of data collection via online workshops, as well as what we have learned and carry forward from these stages into our current artmaking practice, we have aimed to contribute a creative and collaborative example to the scholarly literature on research and knowledge translation. In this project, we sought to go beyond the human-centric approach that is typically adopted in digital health towards data, knowledge, and literacy (Fors et al., Citation2013; Lupton, Citation2021; Lupton & Watson, Citation2022; Olsson & Lloyd, Citation2017). We have shown that health information ecologies are expansive: malleable and diverse networks of people, health states, data, senses, spaces, technologies, objects, and other living things. By exploring how people learn about their bodies and health states through creative methods that draw visual attention to the relevance of environment, the powerful and vibrant entanglements of human and planetary health have been surfaced.

In the project and in this article, drawing from scholarship on knowledge translation and data physicalisation which emphasises the generation, dissemination, and exchange of knowledge not as an outcome but as a process (D’Ignazio & Klein, Citation2020; Searles et al., Citation2016), we have focused on process. We have shared and reflected on nuances in the critical early stages of our project, describing what our collaborative process has involved and aiming to contribute to the broader development of creative research projects designed with care. Throughout, our attention has been drawn to vital elements of research and translation: communication; connection; reflection; feelings; and presence. Dedicated opportunities to meet and discuss the aims and design of the project, especially strategies for participant recruitment, were essential. Our creative approach to studying health information required a team of distinct scholarly, creative, and professional backgrounds. Opportunities to ‘get on the same page’ and (re)visit the big and little details of the project have been vital. By facilitating communication within the project, we used our diverse expertise to critically consider how this novel project might be best communicated to others, from prospective participants with varying interests and needs, to the different potential exhibition audiences of health consumers, health professionals, and general publics.

Reflection has also been a vital process for us in this project. This includes reflexivity to establish and bring our advisory group and research practices into the project. Reflection is also significant, as we now aim to reflect on more-than-human health and health information with our creative exhibition. As we have discussed throughout this article, we bring a creative approach to knowledge translation in this project. This approach builds on scholarship that emphasises the embodied, affective, and emplaced dimensions of health and literacy (Lupton, Citation2019), and work that conceptualises the ‘flows’ (Searles et al., Citation2016) and complex processes of research translation (Kelly et al., Citation2021). By undertaking this project so far and thinking with this scholarship and a more-than-human theoretical approach, we consider research-creation and translation as reflection: as a particular representation or manifestation of research undertaken, and as a generative moment for both us, our participants, and audiences. As researchers, we tuned into the corporeal, embodied, and emplaced ways that people do and feel their health in/with their communities and wider socio-spatial environments.

We carry this consideration, of what and how people sense and feel, into the exhibi- tion making practices in which we are currently engaged (at the time of writing). We are working now on creating exhibition materials that reflect the aforementioned connections and feelings in ways that engage visual arts and broader community contexts, serving as provocations for diverse audiences on how to sense and make sense of the relations between communities, health, data, environments, and more-than-human materials. We hope to animate the lived and multisensory experiences of workshop participants and speak to broader publics. We are interested in how artefacts and hands-on activities created with and through materials from the natural world might afford multisensory experiences that reconnect people to their relationships with the environment. Materials such as wood, stone, flowers, leaves, clouds, and water are those that participants identify with feeling and sensing their (good and poor) health, and which are also marked by their own histories and environments, bearing more-than-human traces. We bring these attunements to the making of our materials and aim for our resulting exhibition to inspire these more-than-human health connections for visitors. We are adopting a creative- research-translation approach to curation, positioning the gallery as a discursive space – a ‘campfire' (D'Ignazio & Klein, Citation2020, p. 145) around and with which we might further enliven the findings and insights from the workshops and artmaking process through gallery talks and public programs. For us, the exhibition serves as a receptive, generative place for echoing and expanding knowledge flows between health consumers, researchers, and the broader community. We hope that these assemblages of research and translation will vibrate with vitalities that move people, in all senses of the word: helping them to see, feel, and think otherwise. For us, such an approach aligns with Braidotti’s (Citation2019) vision of affirmative ethics and generative life: an approach to social inquiry that opens up the possibilities of more capacious relational connections with the more- than-human world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial hells: Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. Verso Books.

- Bjerregaard, P. (Ed.). (2019). Exhibitions as research: Experimental methods in museums. Routledge.

- Bleakley, A. (1999). From reflective practice to holistic reflexivity. Studies in Higher Education, 24(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079912331379925

- Braidotti, R. (2019). Affirmative ethics and generative life. Deleuze and Guattari Studies, 13(4), 463–481. https://doi.org/10.3366/dlgs.2019.0373

- De Jager, A., Tewson, A., Ludlow, B., & Boydell, K. (2016). Embodied ways of storying the self: A systematic review of body-mapping. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.2.2526

- D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2020). Data feminism. MIT press.

- Fitzpatrick, K., Grant, T., Waite, C., & Ong, S. G. (2021). Poetry and health education: Using the poetic to write the body and health. In D. Lupton & D. Leahy (Eds.), Creative approaches to health education (pp. 123–135). Routledge.

- Fors, V., Bäckström, Å, & Pink, S. (2013). Multisensory emplaced learning: Resituating situated learning in a moving world. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 20(2), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2012.719991

- Fotopoulou, A., & O’Riordan, K. (2017). Training to self-care: Fitness tracking, biopedagogy and the healthy consumer. Health Sociology Review, 26(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2016.1184582

- Griebel, L., Enwald, H., Gilstad, H., Pohl, A.-L., Moreland, J., & Sedlmayr, M. (2018). Ehealth literacy research—Quo vadis? Informatics for Health and Social Care, 43(4), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538157.2017.1364247

- Hogan, S. (2021). Arts-based participatory research in the perinatal period: Creativity, representation, identity and methods. In D. Lupton & D. Leahy (Eds.), Creative approaches to health education (pp. 41–56). Routledge.

- Kelly, C., Kasperavicius, D., Duncan, D., Etherington, C., Giangregorio, L., Presseau, J., Sibley, K. M., & Straus, S. (2021). ‘Doing’ or ‘using’ intersectionality? Opportunities and challenges in incorporating intersectionality into knowledge translation theory and practice. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01509-z

- Lenette, C., Cox, L., & Brough, M. (2015). Digital storytelling as a social work tool: Learning from ethnographic research with women from refugee backgrounds. British Journal of Social Work, 45(3), 988–1005. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct184

- Levin-Zamir, D., & Bertschi, I. (2018). Media health literacy, eHealth literacy, and the role of the social environment in context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(8), Article 1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15081643

- Lockton, D., Singh, D., Sabnis, S., Chou, M., Foley, S., & Pantoja, A. (2019, June 23–26). New metaphors: A workshop method for generating ideas and reframing problems in design and beyond. Proceedings of the 2019 on Creativity and Cognition (pp. 319–332).

- Lupton, D. (1997). Consumerism, reflexivity and the medical encounter. Social Science & Medicine, 45(3), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00353-X

- Lupton, D. (2017). Feeling your data: Touch and making sense of personal digital data. New Media & Society, 19(10), 1599–1614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817717515

- Lupton, D. (2018). Towards design sociology. Sociology Compass, 12(1), Article e12546. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12546

- Lupton, D. (2019). Data selves: More-than-human perspectives. Polity Press.

- Lupton, D. (2021). ‘Things that matter’: Poetic inquiry and more-than-human health literacy. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1690564

- Lupton, D., & Watson, A. (2021). Towards more-than-human digital data studies: Developing research-creation methods. Qualitative Research, 21(4), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120939235

- Lupton, D., & Watson, A. (2022). Research-creations for speculating about digitized automation: Bringing creating writing prompts and vital materialism into the sociology of futures. Qualitative Inquiry, 28(7), 754–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004221097049

- Macdonald, D., Van Gijn-Grosvenor, E. L., Montgomery, M., Dew, A., & Boydell, K. (2021). ‘Through my eyes’: Feminist self-portraits of osteogenesis imperfecta as arts-based knowledge translation. Visual Studies, 37(4), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2021.1899849

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2018). Creative arts therapies and arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 68–87). The Guilford Press.

- Manning, E. (2016). Ten propositions for research-creation. In N. Colin & S. Sachsenmaier (Eds.), Collaboration in performance practice: Premises, workings and failures (pp. 133–141). Springer.

- McLeod, K., & Fullagar, S. (2021). Remaking the post ‘human’: A productive problem for health sociology. Health Sociology Review, 30(3), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2021.1990710

- Muhr, M. M. (2020). Beyond words – The potential of arts-based research on human-nature connectedness. Ecosystems and People, 16(1), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2020.1811379

- Olsson, M., & Lloyd, A. (2017). Being in place: Embodied information practices. Information Research, 22(1), CoLIS paper 1601. http://informationr.net/ir/22-1/colis/colis1601.html.

- Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2015). Exploring material-discursive practices. Journal of Management Studies, 52(5), 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12114

- Renold, E., & Ivinson, G. (2022). Posthuman co-production: Becoming response-able with what matters. Qualitative Research Journal, 22(1), 108–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-01-2021-0005

- Searles, A., Doran, C., Attia, J., Knight, D., Wiggers, J., Deeming, S., Mattes, J., Webb, B., Hannan, S., Ling, R., Edmunds, K., Reeves, P., & Nilsson, M. (2016). An approach to measuring and encouraging research translation and research impact. Health Research Policy and Systems, 14(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0131-2

- van Dooren, T., Kirksey, E., & Münster, U. (2016). Multispecies studies: Cultivating arts of attentiveness. Environmental Humanities, 8(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3527695

- Watson, A., & Lupton, D. (2022). Remote fieldwork in homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Video-call ethnography and map drawing methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221078376

- Watson, A., Lupton, D., & Michael, M. (2022). The presence and perceptibility of personal digital data: Findings from a participant map drawing method. Visual Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2022.2043774

- Welch, R., Taylor, N., & Gard, M. (2021). Environmental attunement in the health and physical education canon: Emplaced connection to embodiment, community and ‘nature’. Sport, Education and Society, 26(4), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1890572

- Whitelaw, M. (2012). Weather bracelet and measuring cup: Case studies in data sculpture. https://mtchl.net/assets/Dataforms.pdf.

- Wozniak-O’Connor, V. (2017). Millionth Acre Archive [Radiata pine, bracing plywood, found antler sheddings, cast 3D prints, custom electronics and field recordings]. Casula Powerhouse, New South Wales. https://vworesearch.art/maa2017.

- Wozniak-O’Connor, V. (2018). Governors Island Hologram [Digital hologram, photopolymer film and acrylic]. Exhibited at Museu Da Cidade De Aviero, Portugal. https://vworesearch.art/giholo.

- Wozniak-O’Connor, V. (2020). Navstar [7 mm bracing plywood, digital plotter, laser-cut acrylic]. Exhibted at Verge Gallery, Sydney. https://vworesearch.art/navstar.

- Zhao, J., & Vande Moere, A. (2008, September 10–12). Embodiment in data sculpture: A model of the physical visualization of information. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Digital Interactive Media in Entertainment and Arts.