ABSTRACT

This paper discusses how established industries adapt to digital transformation. While digitalisation is perceived as an impetus for change, either due to the opportunities or threats it brings about, not all industries are able to change unlimitedly. We seek to understand digital transformation concerning products and services perceived to have a wider public value. Our empirical case is the newspaper industry in Norway, which has a strong collective identity tied to the societal function of independent journalism. We find that an industry with a resilient identity leaning towards preservation can learn how to use the digital space to adapt and innovate effectively. The adaptation and innovation processes are shaped by the interplay between the collective identity and the nature of digital work and innovation. The outcome is a continued emphasis on retaining the core mission but with an increasingly pragmatic approach to how and in what form it is safeguarded. Continuous collaborative experimentation and deliberation on the fit between innovations and the collective identity is a key change mechanism. Our study contributes to a better understanding of collective identities and their interplay with innovation.

Introduction

Digital transformation represents a major challenge for many industries. It gives rise to opportunities due to the specific nature of digital technology, which leads to new business models, new users and innovative experiments (Nambisan et al., Citation2019; Yoo et al., Citation2012). Yet, digital transformation also entails new entrants and new business models, which threaten the survival of both incumbents and deeply established ideals and practices (Christensen & Bower, Citation1996; Cozzolino et al., Citation2018). As digital technologies often lead to different working processes and practices in all the firms within a given industry (Nambisan et al., Citation2019), the result of digital transformation can be a shift in the common understanding of what the industry is as well as what it should do – its collective identity.

Recent studies have emphasised the role played by experimentation and innovation in effectively dealing with the impact of digital transformation on companies (Bianchi et al., Citation2020; Garud & Karunakaran, Citation2018). However, companies are not always able to engage in boundless experimentation and innovation when established working patterns and collective identities are threatened (Garud & Karunakaran, Citation2018). Indeed, hospitals, schools, newspapers and art and heritage institutions are all examples of industrial settings that are tied to ‘public values’, which may limit the potential for innovation driven purely by economic concerns (Bozeman, Citation2007).

In the case of newspapers, digital transformation has been described as an ‘existential crisis’, not just because it introduces completely new journalistic activities and practices, or because it threatens the survival of firms, but because it imperils collective ideals regarding the industry’s wider purpose (Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). Newspapers tend to stress their value as a ‘public service’ (Hujanen, Citation2009), highlighting the link between quality journalism and democratic vitality (Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). Moreover, they tend to emphasise ideal-typical values such as neutrality and ethical accountability (Deuze, Citation2005). These ideas constitute the main aspects of the newspaper industry’s collective identity and also underlie its core activities.

Studies of digital transformations in settings in which the provision of public or cultural values is central have revealed that organisations combine the protection of core activities with innovations that secure their economic survival (Cozzolino et al., Citation2021, Citation2018; Kavanagh, Citation2018; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). This approach has been conceptualised as uniting a charity logic and a business logic (Battilana & Lee, Citation2014) or as balancing the ideas of ‘market-oriented’ and ‘society-oriented’ journalism (Hujanen, Citation2009). Juggling innovation, experimenting and protecting core values are associated with numerous tensions, as organisations often introduce new and economically viable business models but fail to abandon old and economically problematic ones (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018; Kavanagh, Citation2018; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). Although digital transformation may threaten an industry’s collective identity, the identity itself also shapes and constrains innovative responses, a subject that has received ‘remarkably little attention’ to date (Kavanagh et al., Citation2021).

To contribute to an improved understanding of how established industries adapt to digital transformation, and thereby to contribute to this special issue, we argue that it is necessary to consider the broader understanding that such organisations have with regard to their industrial setting. A collective identity can be defined as ‘the set of characteristics seen as intrinsic to, and constitutive of, a group of actors who share a specific purpose and similar outputs’ (Kavanagh et al., Citation2021, p. 2). Collective identities shape our understanding of the core characteristics of an industry, and they also guide the behaviour of organisations by defining what is important and valued, thereby affecting innovation patterns (Porac et al., Citation1989; Stigliani & Elsbach, Citation2018).

Our aim is to contribute to the discussion concerning innovation in situations in which innovation activities, as a response to increased digitalisation, are problematic because they may endanger the collective identity. Our research question is as follows: During digital transformation, how does the collective identity relate to the innovation activities within an industry in which the core products are seen to represent public values? To answer this question, we conduct an industry-level study of newspapers in Norway. More specifically, we analyse the experiences and efforts of 29 organisations with regard to innovation in an increasingly digital market, ensuring that the sample of organisations included high-status incumbents, lower-performing actors and new entrants, that is, the three central contexts for exploring identity-innovation relations (Kavanagh et al., Citation2021, p. 13).

We find that a strong collective identity revolving around the provision of public values has a multi-faceted impact on the digital transformation of an established industry. In fact, a strong identity restricts the potential for adaptation, change and innovation by fostering a shared understanding what an industry should do. At the same time, it ties industry members together and enables not only survival but also (1) effective digital innovation initiatives in the form of collaborative experimentation and (2) gradual identity stretching and change. These findings indicate that the digital nature of the transformation as well as the shared understanding of its purpose and mission mutually affect each other and also jointly shape industrial development.

Theoretical framework

Digital transformation of industries and public values

Digital technologies set the stage for new digital innovations and, ultimately, the transformation of many industries (and the associated activities) in three key ways (Nambisan et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). First, digital technologies allow for new solutions, new users and new roles for organisations. Second, they provide both the potential and actual possibilities for organisations to relate to users in new ways (i.e., affordance aspect). Third, digital technologies can unleash unprompted creativity and innovation within an industry (i.e., generativity aspect).

These characteristics represent significant opportunities and challenges for established industries. For example, digital technologies provide early-stage opportunities because the costs associated with experimenting in the digital realm are lower than those associated with other settings, while companies working with digital technologies have a lower threshold for engaging in innovation (Garud & Karunakaran, Citation2018; Nambisan et al., Citation2019; Yoo et al., Citation2012). This can lead to experiments with business models and digital innovation (Andries et al., Citation2013; Appio et al., Citation2021; Bianchi et al., Citation2020; Bojovic et al., Citation2020; Bourreau et al., Citation2012; Cozzolino et al., Citation2018; Hampel et al., Citation2020; Restivo & Cardoso, Citation2020), including the digital substitution of key products and services (Bogers et al., Citation2015).

At the same time, however, incumbents have to deal with the appearance of new actors with new business models, emerging technologies and new product categories that challenge the incumbents’ position. As a result, the core activities and value that incumbents provide to customers can become economically unsustainable (Sabatier et al., Citation2012). For example, the enduring business model for financing journalism within the newspaper industry involves a combination of sales of newspaper products (e.g., subscriptions, single sales) and significant advertising income, and it has been fundamentally challenged by digitalisation (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018). Companies have been forced to assess the viability of the traditional financing model in a situation in which digitalisation is perceived as an external shock (Mazza & Strandgaard Pedersen, Citation2004). In addition, the challenge has also involved the wider changes associated with a digital society and how the news is consumed.

Such changes can pose a cognitive challenge when it comes to shaping adequate responses to digitalisation and work in the digital realm (Lo et al., Citation2020) – a process that may require a significant amount of time (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, Citation2014; Foss & Saebi, Citation2017; Rivkin, Citation2000), coopetition (Cozzolino et al., Citation2021) as well as a deeper shift in perceptions regarding the functioning and purpose of an industry (Altman & Tripsas, Citation2015; Danneels et al., Citation2018). Experimentation appears to play a particularly important role in shaping such responses. For example, newspaper companies have attempted to tackle the loss of profits and market shares by experimenting with applying business models designed for printed newspapers to the digital environment, in addition to more radical innovations (Clemons, Citation2009; Collis et al., Citation2009; Holm et al., Citation2013; Kopper, Citation2004; Nel, Citation2010; Pauwels & Weiss, Citation2008). Despite earlier waves of digitalisation, digital transformation remains a key item on the industry agenda (Katz, Citation1994). Experiments that seemed to work at a given point in time appeared to cause serious trouble for newspapers during subsequent periods, for example, when providing free content online devalued that content and reduced subscription income (Holm et al., Citation2013, Citation2012). In general, experimentation may initially prove problematic in terms of dealing with the challenges of digital transformation (Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014), although it can gradually lead to more radical adaptation and innovation (Garud & Karunakaran, Citation2018; Gioia et al., Citation2013).

However, despite the threats to their survival and the opportunities stemming from digital transformation, not all industries are able to change profoundly. Some industries offer products or services that are tied to public values, meaning that (some of) those products and services serve the public interest, which can be defined as ‘the outcomes best serving the long-run survival and well-being of a social collective construed as a “public”’ (Bozeman, Citation2007, p. 12). The public interest represents an ideal, and it can be tied to the public values held by a number of different stakeholders, including those within a given industry or sector (Bozeman, Citation2007, p. 12). In other words, the central members and external stakeholders may perceive that an industry serves a public interest that needs to be protected, not transformed. Among the examples of collective identities tied to public values are autonomous journalism and its role in democracies (Deuze, Citation2005), organisations tied to a specific social purpose or cause (Alshawaaf & Lee, Citation2021; Battilana & Lee, Citation2014), education and research organisations established to facilitate long-term knowledge production and learning (Gulbrandsen & Thune, Citation2020) and art and heritage organisations (Kavanagh, Citation2018). The replacement of core activities with novel ones may be both economically viable for individual organisations and a better solution within a digital market, but those replacements might have wider negative effects, for example, when consumer clickbait journalism dwarfs autonomous critical writing (Grubenmann & Meckel, Citation2017; Hujanen, Citation2009). In this context, companies face complex dilemmas when they need to innovate within a digital market, dilemmas that extend far beyond those faced by firms for which the market valuation is the only relevant scale (Bozeman, Citation2007).

Prior studies have shown that organisations in these settings become innovative in an effort to protect their core (i.e., to secure their survival when economically threatened). Newspapers engage in experimentation with new products and services in order to sustain their core value of offering independent news (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). Battilana and Lee (Citation2014) study of social enterprises highlighted how they combine business and charity so as to defend the core activities that are perceived as irreplaceable. Art and heritage institutions similarly adapt their business models by expanding their core activities to include new types of experiences in an attempt to attract users (Alshawaaf & Lee, Citation2021; Coblence & Sabatier, Citation2014; Kavanagh, Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2021).

Although innovative adaptations may serve to overcome the issue of economic sustainability, both the defensive strategy itself and the identity it represents can limit the ongoing innovation process. For instance, newspaper organisations have sustained incumbent business models in parallel with the introduction of innovation activities, even though the established models have proved problematic in relation to their survival (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). Cozzolino et al. (Citation2018, p. 1195) suggested three potential explanations for the willingness to defend the incumbent business model and core activities: difficulties in exploring new options, perceiving value (as worth) in the incumbent business model and unexpected setbacks in the market. Kavanagh et al. (Citation2021) argued that further research is needed, particularly in terms of the second of these explanations. They stated that defensive or limited innovation can be tied to collective identity, which can limit innovation through top management cognition and emotion, organisational member resistance and wider stakeholder resistance. We are also interested in examining the value that incumbent organisations perceive in their long-established core activities. In accordance with Kavanagh et al. (Citation2021), we argue that the issue of the attribution of value transcends the organisational level and is connected to the collective understanding of what a given industry is.

This literature review highlights how high levels of innovation activity may be required to respond to the fundamental and all-encompassing issue of digitalisation, which is still seen as representing a ‘mind-blowing uncertainty’ for the newspaper industry (Grubenmann & Meckel, Citation2017, p. 743). We argue that the issue of digital transformation may also represent an identity crisis that is linked to macro-level structural and cultural issues (cf. Kopper, Citation2004; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). The solutions to the issues of ‘what a newspaper should do’ in the new digitalised world and ‘how it should make money’ are tightly connected to rethinking the identity. We further argue that the newspaper industry represents a great case for adopting an ‘identity’ approach to understanding innovation in the time of digitalisation. Focusing on identity can help us to understand how and why organisations choose to adapt – or why they fail or choose not to adapt – a subject about which there is currently only limited systematic evidence (cf. Kavanagh et al., Citation2021).

Collective identity and innovation

We draw on prior work concerning collective identity to analyse the adaptation of an established industry to digital transformation. At the organisational level, identity involves self-perception and understanding both ‘who we are’ and ‘what we are’ as an organisation (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985; Tripsas, Citation2009; Whetten, Citation2006). Moreover, identity guides business strategy and innovation, and it often serves as a compass, especially during times of uncertainty (Anthony & Tripsas, Citation2016; Ravasi et al., Citation2020; Tripsas, Citation2009). In many industries, the identity conveys a ‘dominant logic’, that is, a common sense of how the industry should function (Sabatier et al., Citation2012).

In addition, key organisational members may also be members of professions characterised by shared values. For example, journalists may exhibit strong professional identities and ideologies, which constitute central aspects of the collective identity of the newspaper industry (Deuze, Citation2005; Grubenmann & Meckel, Citation2017). A collective identity, similar to an organisational identity, forms part of the shared mental models of its members. It has an effect on decisions made within organisations (Huff, Citation1982; Porac et al., Citation1989), although it has only recently been explicitly tied to innovation (Kavanagh et al., Citation2021). Identity is not merely a cognitive concept, as it may also be embedded into policies and regulations such as those intended to protect industries deemed to serve the public interest. This implies that a collective identity may be shared by stakeholders beyond an industry’s main organisations.

We include professional and wider stakeholder perceptions of identity within the concept of collective identity, which consists of strongly institutionalised and internalised central principles and practices at the industry level (Kavanagh et al., Citation2021; Stigliani & Elsbach, Citation2018). A strong identity provides an industry with legitimacy, makes it recognisable and separates it from other industries (Lo et al., Citation2020; Rao et al., Citation2003; Wry et al., Citation2011). Moreover, it provides a frame for evaluating the decisions made by its members (Fligstein, Citation1997; Porac et al., Citation1989).

Collective identities, similar to organisational identities, can be divided into specific core elements, namely practices, beliefs, competitive landscape and values (Porac et al., Citation1989; Wry et al., Citation2011). These elements persist over time, constitute aspects of the mental models held by the organisational members of an industry and affect both the framing of environmental changes (Kaplan & Tripsas, Citation2008; Orlikowski & Gash, Citation1994) and the responses to those changes (Elsbach & Kramer, Citation1996; Porac et al., Citation1989; Tripsas, Citation2009).

Members often agree as to the distinguishing practices (products, services, value creation and capture logics) that define the scope of an industry’s main business (Rao et al., Citation2003; Sabatier et al., Citation2012; Wry et al., Citation2011). The core beliefs regarding how an industry should function are widely accepted by stakeholders (Porac et al., Citation1989), and they define aspects such as how to work with suppliers, how to approach customers and how to work with innovation. Collective identities also consist of a common definition of the competitive landscape (Porac et al., Citation1989), which marks out competitors and differentiates insiders from outsiders. Finally, the members of an industry frequently share core values that serve as both standards to follow and goals to achieve (Gecas, Citation2000). These values denote the criteria for success and represent a moral compass. Even though a collective identity may be important in terms of understanding innovation, it does not imply that all organisations respond in similar ways to challenges such as digital transformation.

As they are subject to less authority than an organisational identity, collective identities are often reinterpreted (Wry et al., Citation2011), for example, the difference between defining oneself as part of the newspaper industry and defining oneself as a tabloid newspaper. Collective identities may be undermined if members deviate too much from the core elements (Wry et al., Citation2011), which poses challenges if those core elements are considered to have a public value (Deuze, Citation2005). Thus, there exist interdependencies and tensions between industry and organisational identities (Fiol, Citation2002; Patvardhan et al., Citation2015; Porac et al., Citation1989). The core elements of an identity can serve as a ‘cognitive anchor’ and lead to some degree of isomorphism, although companies also need to distinguish themselves in the market.

Collective identities are subject to ‘identity work’, which consists of activities used to construct, maintain and regulate an identity, including explicit references to the core elements as well as matching between organisational and collective identities (Patvardhan et al., Citation2015). The changing and adapting of identities can also be an effective means of managing tensions between identity and innovation (Cloutier & Ravasi, Citation2020; Kavanagh et al., Citation2021). Identities may change when there is a disruption or discontinuity (Ravasi & Schultz, Citation2006), while some innovations may require organisations to realign their identities (Anthony & Tripsas, Citation2016; Garud & Karunakaran, Citation2018) in order to avoid negative consequences (Tripsas, Citation2009). The same may be true of collective identity. When industries face digital transformation, it may threaten the core elements in such a way as to necessitate identity realignment work (Patvardhan et al., Citation2015).

Theorising about the newspaper industry and modern journalism, Deuze (Citation2005) argued that ‘multimedia’, a term that encompasses many forms of digital transformations, represents a major challenge to the ideal-typical values embedded within much of the industry. By using the term ‘ideology’, he highlighted the cognitive and political nature of the industry’s identity, and he defines the core elements of that identity as public service, objectivity, autonomy, immediacy (‘news’) and ethics. These widely shared attributes are used to fend off external threats as well as to resist engaging in innovation, although the distributed, localised, team-based and interactive nature of digitalisation requires a fundamental reassessment of exactly what aspects such as public service, objectivity and autonomy may imply.

Further, the term ‘transformation’ indicates ambiguity with regard to ‘what an industry should be’ (Santos & Eisenhardt, Citation2009). For example, the threat of new entrants can lead to tensions within the established collective identity: distinct adaptations of organisational-level identities challenge the consensual collective industry frame, making it difficult for incumbents to make sense of the situation (McKendrick & Carroll, Citation2001; Stigliani & Elsbach, Citation2018). One common response to ambiguity and uncertainty involves referring to what is known about the industry and how it is supposed to work (Elsbach & Kramer, Citation1996; Spender, Citation1989).

A crisis can strengthen a collective identity (Patvardhan et al., Citation2015) due to the self-reinforcing nature of referring to the established core elements when in ambiguous situations (Porac et al., Citation1989). An example of this can be seen in how the German newspapers did not include new entrants within their collective identity and instead implemented innovation strategies based on well-established core elements of that identity (Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). Anthony and Tripsas (Citation2016) described such innovations as identity-enhancing innovations because the identity is strengthened through engaging in innovation. However, some crises may require more radical innovations that alter the core elements (e.g., Khaire & Wadhwani, Citation2010), meaning that they can be termed identity-stretching innovations if they do not fundamentally shift the identity (Anthony & Tripsas, Citation2016). Yet, when a transformation requires significant and radical innovation activities in order to secure survival, industry members may have to engage in a more profound trade-off between the core elements and novelty (Kavanagh, Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2021). In this case, identity-challenging innovations may prove necessary to survival (Anthony & Tripsas, Citation2016), which can lead to the development of a new identity (Tripsas, Citation2009).

Empirical investigations based on collective identity theories have shown that the challenge of digital transformation elicits a dichotomous response between an ‘arts’ group and a ‘crafts’ group of key employees within the newspaper industry (Grubenmann & Meckel, Citation2017). The first group adheres to a traditional interpretation of identity and highlights challenges such as quality versus speed and status degradation, while the second group searches for new identities on the basis of new reference points, new product designs and new role concepts. The responses to digitalisation can, therefore, vary significantly, and potential new identities and inherent values (‘good journalism’) are the result of ongoing negotiations between market-oriented and societal or public value-oriented stakeholders (Hujanen, Citation2009). Case studies of newspaper firms have mostly revealed how they ‘have failed so far’ in terms of digital innovation (Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014), although there is some evidence that leading media houses have successfully adopted a platform perspective (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018). This has led to concern that a few firms (e.g., The New York Times) will crowd out competition and so threaten journalism more fundamentally (Smith, Citation2020).

This literature review provides interesting starting points when it comes to analysing identities, but it has a narrow view of innovation (mostly new products or formats) and discusses journalism more than the newspaper industry. Alternatively, our framework highlights how a collective identity often contains wider public values, and we use this insight to understand the dynamics of adaptation and innovation within established industries undergoing digital transformation. In fact, experimenting with new products/services is often directly linked to experimenting with novel identity traits (Garud & Karunakaran, Citation2018).

Methods and data

The case – the Norwegian newspaper industry

The newspaper industry in Norway, a country in Northern Europe with a population of 5.4 million (2021), is of international interest because newspapers in the country faced digital innovation challenges and responded to them very early on. This offers an opportunity for gaining insights from pioneers and early adopters of digital innovation.

There are around 200 publications in Norway that are counted as newspapers (with new issues appearing on a schedule ranging from daily to weekly), extending from small locally owned papers to large media firms with operations outside of Norway and involvement in businesses other than the news. Almost all are for-profit firms, and there has been a significant restructuring and concentration of the industry over the last two decades. More than half of all the newspapers are owned by three major media houses: Schibsted (13 newspapers, around €750 million turnover), Amedia (63 newspapers, €330 million euro turnover) and Polaris Media (29 newspapers, €150 million euro turnover) (Medienorge, Citation2019).Footnote1

While the media houses may share technologies, platforms, content and more, each newspaper will have its own editor-in-chief and operate as an independent entity according to the Redaktørplakaten, a declaration of the rights and duties of editors as agreed by the industry association and the editors’ association (Norwegian Media Businesses’ Association & Association of Norwegian Editors, Citation1953/2019). The editor-in-chief has legal responsibility for the newspaper’s content as well as employer’s liability for (at least) the employed journalists. For many Norwegian newspapers, the editor will also be the chief executive officer (the editor-publisher distinction is not normally made in Norway). The industry has somewhat favourable conditions, with no value added tax for printed newspapers and limited direct production support available for a few niche national newspapers.

The volume of printed newspapers has decreased rapidly. Indeed, the newspaper with the largest circulation for most of the past three decades, the tabloid VG, had a circulation of less than 60,000 at the end of 2019, down from almost 400,000 not even two decades earlier. The subscription-based Aftenposten is now the largest printed paper, with a circulation of close to 130,000, although that is also half of its circulation a little more than a decade ago (Mediebedriftene, Citation2020).

News consumption among Norwegians is high, with 85% of the adult population reading newspapers or dedicated digital news sites every day. The Reuters Institute (Citation2020) Digital News Report revealed that Norwegians are willing to pay to access content online. In fact, the share of the population who did so in 2020 was 42%, higher than in any of the other 36 countries included in the study. Norwegians mostly go directly to the websites of newspapers, rather than accessing articles through social media and general web searches, and the share who uses local and regional news sites is more than double the European Union average. Overall, news consumption has moved increasingly towards digital media. VG’s online edition is the largest, with more than two million unique visitors accessing it on average every day in 2019 and with more than 200,000 paying for an online subscription (i.e., including content behind a paywall) (Medienorge, Citation2019). Norway scores highly on the indicators of digitalisation, including broadband access among the population and the use of smartphones.

The traditional advertising income has fallen for all the newspapers, especially over the last decade. The most recent figures show a drop in advertising income for printed newspapers from €770 million in 2008 to €260 million in 2018 (Medienorge, Citation2019). Advertising in digital editions has increased, albeit with large variations between newspapers. The largest media houses reported record operating margins in 2018, including 13% for the Amedia group of local newspapers and 19% for Schibsted (which owns Aftenposten, VG and other publications in Norway and abroad) (Medienorge, Citation2019). The strong numbers reported by the major media houses may signal the success of the transition into the digital era (Krumsvik, Citation2015; Krumsvik et al., Citation2013), although there has been a lot of unrest and worry both in and around the industry. All the major interest organisations regularly report that the future looks bleak. A 2017 public commission suggested a significant and, to some degree, temporary increase in public subsidies to the industry in an effort to alleviate this situation (Norges offentlige utredninger, Citation2017, p. 7). This was followed by a 2019 white paper, which suggested a number of changes to ensure the industry’s editorial independence as well as improved framework conditions (Kulturdepartementet, Citation2019).

Research design, method and sample

The present paper is based on a qualitative study of the newspaper industry in Norway, with semi-structured interviews serving as the main research method, supported by industry statistics and documents. The newspaper industry was chosen for two main reasons. First, the industry performs an important societal function by providing curated news, which is widely perceived to represent a public value, as also established in national legislation. Consequently, industry members hold a collective understanding of what it means to generate news as well as how that is supposed to be done (Deuze, Citation2005). Second, the digital transformation of the past two decades has significantly shaken the industry, particularly the traditional business model. The newspaper industry is, therefore, a suitable case for exploring the identity-innovation link in an increasingly digital industry.

The aim of our empirical work was to analyse innovations as well as collective identity expressions and changes. We were particularly interested in how the interviewees explained the choices behind the activities related to innovations, and we scrutinised how those choices could be related to the collective identity. Analysing these linkages enabled us to generate a complex picture of the interplay between innovation and collective identity within the newspaper industry.

Our research design allowed for an understanding of specific issues experienced by the providers of products and services tied to public values. Prior studies identified an interesting pattern of adaptation and innovation that combines the proactive introduction of novelty and the preservation of (problematic) strategies (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). We sought to understand why such a pattern occurs by examining the collective identity of the industry, rather than the identities of individual organisations.

We conducted semi-structured interviews during spring 2017 in an effort to gather data concerning innovation, the challenges related to digital transformation and collective identity. We interviewed actors from organisations acquainted with activities related to both editorial work and innovation – who were well positioned to detail experiences with digital transformation and the industry-level identity – as suggested by Porac et al. (Citation1989) and Kavanagh et al. (Citation2021). We asked the interviewees about changes, innovations and their implications, and the interviews focused on concrete experiences and in-depth questioning, rather than on general questions about the organisation’s outlook, worries or opportunities. We included questions about the industry level, and we asked about how changes could be related to the function of newspapers within society (many mentioned this topic in response to open questions). We also interviewed industry stakeholders, as we considered them to be important additional sources of information about how industry-level actors contribute to designing and ensuring compliance with regulatory guides, technological standards and more.

Based on a database of 108 central newspapers in Norway, we conducted 26 newspaper interviews (by phone, face-to-face and one conversation via email). We also conducted three interviews with industry-level actors, leading to a total of 29 interviews. Among the newspapers, eight were larger national/regional papers, two were niche and 15 were local. Thus, our sample included all the major national and regional newspapers as well as a selection of local and niche ones. In their call for further research into how collective identity shapes innovation, Kavanagh et al. (Citation2021) hypothesised three boundary conditions and the related innovation scenarios to be in need of more attention: (i) high-status incumbents, (ii) poor performance compared with peers among weaker actors and (iii) new entrants. We covered the first group through several interviews with representatives of the leading and powerful media houses, the second group through our selection of local and niche actors, and the third group through our inclusion of several born-digital newspapers.

We anonymised the gathered data, and we provide only minimal information about the sample in the present paper in order to protect the respondents. Norway is a small country, and the newspaper industry is highly collaborative and characterised by significant mobility. For these reasons, we decided not to provide further information about the respondents and their organisations.

Data analysis

We applied an inductive methodological approach and drew heavily on the Gioia grounded theory method (Gioia et al., Citation2013) to analyse the data. The aim was to develop in-depth insights into the understudied links between the phenomena of interest. Through thick and detailed information on digital transformation within the newspaper industry, we were able to extract concepts and identify the patterns of relationships between them.

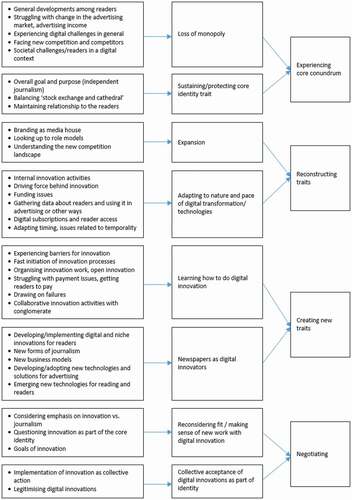

The analysis was conducted in several steps. First, the interviews (totalling 1203 minutes) were recorded, transcribed and coded using Nvivo. The coding was performed by both researchers through an iterative process in which the codes were discussed several times in order to harmonise the interpretations and secure inter-coder reliability. The first coding resulted in many first-order concepts (see ). We allowed new concepts to emerge from the data in accordance with the inductive nature of qualitative research. In the next step, we grouped the first-order concepts into eight second-order concepts that together represented the major topics discussed by the interviewees. Then, we grouped the second-order concepts into four aggregate dimensions. We followed the recommendations of Gioia et al. (Citation2013) and consulted the reviewed theory to define the dimensions. In the final step, we iteratively constructed a graphic model presenting the dynamics of change (), as based on the second-order concepts and aggregate dimensions. The model forms the narrative of our analysis in the subsequent section.

The concepts depict the contours of collective identity as well as the individual traits exhibited by industry members. We found high homogeneity among the respondents in terms of the core collective identity and their willingness to protect it (second-order code ‘Sustaining/protecting core identity trait’). Aside from direct questions, we contend that we can observe collective identity by analysing the common reflections of the interviewees concerning what the industry is and what it should do. This ‘consensus’ approach (Clegg et al., Citation2007; Wry et al., Citation2011) positions consensus and commonality as the main criteria for defining something as part of the collective identity.

Empirical findings: the link between collective identity, adaptation and innovation in an industry undergoing digital transformation

The core collective identity of the Norwegian newspaper industry

We identified strong homogeneity in our interview material in terms of the expressions concerning what the newspaper industry does, should do and why, which we perceived to be a sign of a robust collective identity. This collective identity comprised widely shared and long-standing ideas about the purpose of both newspapers and independent journalism. It was individually expressed in slightly different ways, including ‘we do not cover trivial events’, ‘we have a societal role’ and ‘we are an independent media house’, although the essence of the independence from other private and public actors was generally emphasised. In addition, most of the newspaper companies also identified as economic actors. The respondents explained that their organisations had to balance being a ‘stock exchange and a cathedral’. This is a traditional Norwegian phrase concerning combining cultural/ideal and commercial activities and values, and it is particularly used to discuss literary publishing and newspapers.

How an established industry adapts and innovates during digital transformation

Based on our analysis, we constructed a model that explains the link between collective identity and adaptation/innovation within an industry undergoing digital transformation (see ). The model shows how an established industry changes slowly and gradually through an iteration of several steps. It emphasises the iterative and processual nature of how change occurs within established industries with strong collective identities tied to public values. We will explain the steps and the arrows in the model in the following paragraphs.

Core conundrum related to digital transformation (1)

Digital transformation challenges the established activities of the newspaper industry, its economic survival and, consequently, its collective identity. In our case, this primarily manifested as the loss of a monopoly when newspapers ceased to be the sole source of news for readers. The traditional relationship with readers was based on newspapers’ self-image as independent curators of news and ‘protectors of democracy’:

… our readers expect us to be a critical watchdog … they come to us when they encounter a closed door in the local community. If they can’t reach someone else, they come to us. This is an important function for us to fulfil (Local N).

The newspapers had also lost their monopoly as the providers of daily/regular advertising space to new competitors such as Google and Facebook. This represented a fundamental business model challenge, as the income tied to advertising (as a means of financing journalism) was threatened, which forced them to look for new funding opportunities.

When the established activities and identity are perceived as carriers of public values, industry members prove reluctant to change them. The respondents saw independent and critical journalism as their unique responsibility. It functioned as a kind of moral compass and had intrinsic value. No other actor or industry could provide a replacement:

When I grew up, my hometown had shoe factories and shipyards. They are gone now but the standard of living there is significantly higher. But if journalism disappears, there’s no replacement you can buy from China or elsewhere. It … has a different function than shoe production, and that function is important to people (Media group).

Thus, the conundrum within the industry concerned how to simultaneously survive and protect the public values embodied in the collective identity. It became an important driver of innovation-related activities – ensuring that independent journalism had sufficient financial and human resources to remain a prominent part of newspapers’ total activities. ‘Our societal mission is why we innovate at all’, as one respondent put it (Local G).

Reconstructing identity traits (2a)

The companies facing a conundrum adapted by reconstructing their existing activities and identity traits. This implied adjusting both the activities and practices to the nature and pace of digitalisation, for example, new ways of producing, publishing and distributing news. This included expanding the existing identity traits to (i) internalise the changes related to digital transformation (new technologies, actors, business models and reader behaviour) and (ii) accept the changes to journalism as well as its related activities and practices as part of a changed identity.

We identified three major ways in which the collective identity was expanded. First, the newspaper – that is, its name with suffixes and varieties – had become an umbrella or a brand name covering a portfolio of primarily digital content. The respondents explicitly identified their companies as media houses, rather than solely as newspapers:

‘In 2004 [we] were a classic newspaper with a printing press, journalists, sales and typesetters, but the digital was also there. Now we’re a digital media house with multimedia reporters, a tech-driven development department and automated advertising sales’ (Larger C).

Second, membership and the relationships between the actors within the industry had also changed. New actors appeared (e.g., the tech giants) and fellow newspapers, both international and domestic, became collaborators (rather than competitors) and, sometimes, even role models as digital innovators or when dealing with digital challenges. Finally, the relationship with readers was expanded to include a two-way flow of information. Traditionally, newspapers had provided news to readers, although they had started using data concerning reader behaviour and preferences to customise their offering in collaboration with conglomerates. Dedicated digital or hybrid journalism products targeted towards specific reader groups are a good example of this, in many ways echoing the division of physical newspapers into sections.

Creating new identity traits (2b)

The second adaptation consisted of creating new activities and traits. The need to deal with the threats of digital transformation, together with the need to adapt everyday activities and practices to the digital realm (arrow 3 in the model), gave rise to more proactive digital innovation efforts and, consequently, changes in the collective identity.

In particular, collaborative experimentation with novel digital products and services became a new ability as well as a legitimate strategic approach to working with digital innovation within the industry. It emerged due to the continued need to respond to changes, and it led to several types of innovative outcomes ().

Table 1. Overview of digital innovations

Experimentation had a strong industry-level dimension, not least with regard to the merger of many leading regional and national newspapers into a few powerful media groups. While each organisation appeared to retain a high degree of independence, they increasingly shared articles and collaborated on providing digital content (decentralised) and developing new technological solutions (centralised in conglomerates). In this way, industry members shared the responsibilities and burdens of digital innovation as well as the cognitive complexity of designing effective responses to digital challenges:

[The media house] has centralised development units for editorial stuff and commercial stuff and more, so that’s where you find all the tech developers and those kinds of people. They gather data from all the [media house’s] newspapers and do tests and pilots in different papers to figure out what works journalistically, what works for product pricing, where the threshold is and the willingness to pay (Local F).

Identity controversies and potential mismatches between ideal and practice (4)

The outcomes of reconstructing, particularly the creation of new activities and traits, were often surrounded by controversies because they brought about a discrepancy between what a news company believes it should do and what it actually does do to survive.

The continuous experimentation with digital tools and technologies led to streams of digital innovations that improved the position of the newspapers within the changing industry (). Many innovations were directed towards successfully protecting the established identity, the values it embodied and, particularly, the dominant business models. Examples here include digital and niche sites for specific readers or new forms of digital subscriptions. Some innovations even strengthened the public value ideal of the collective identity, as they represented attempts to reach a wider public than traditional newspaper readers, for example, new digital products and forms of journalism oriented towards young, disadvantaged or specialised readers.

However, some innovations proved controversial and problematic in relation to the collective identity. Hybrid journalistic forms that combined journalistic and commercial aspects, such as new types of commercial services or new forms of advertisements (e.g., content marketing), were controversial because they compromised the traditional function of newspapers as providers of independent news. For example, the introduction of content marketing involved making radically new solutions co-exist with current legitimate practices. Its increasing adoption fuelled a debate on the boundary between commercial activities and journalism in hybrid journalistic products. In this case, the innovation challenged the established collective identity, as it potentially shifted the balance in favour of the ‘stock exchange’, rather than the ‘cathedral’. The respondent from one of the digital-native newspapers, which had developed new advertising formats, confirmed that content marketing was a particular source of controversy because it represented a breach of established ethics:

It involves ads that look like articles. Those of us who work with content, we’re obsessed with distinguishing between journalism and ads. You, as a reader, need to know whether you’re reading journalism, which should be based on quality-assured information, or if you’re reading something paid for by an advertiser (Niche/digital B).

Even when the new hybrid journalistic forms were user-friendly and profitable, they potentially challenged or delegitimised the shared values. The issue did not necessarily concern an aversion to change within the industry, but as many held strong ideals about what a newspaper is and should do, the outcome of experiments needed to fit with such ideals:

There’s a lot of internal pressure to not do those things. And I jokingly say that every second year I get into the top three for Employee of the Year, while the other years I get into the top three for Worst Employee of the Year. It all depends on which products we have launched (Larger/digital A).

This was not a new issue within the newspaper industry. As we came to realise, whenever a new aspect of how newspapers produced, published and sold the news was introduced in practice, it was often surrounded by controversies due to the mismatch with the idealised core collective identity.

Negotiation and acceptance (5)

Introducing changes and sustaining the collective identity did not stop innovation within the industry. Instead, the member companies engaged in initiatives that eventually made space for the acceptance and legitimation of innovations.

These processes were collective. The newspaper companies engaged in internal negotiations as well as in industry-wide discussions about whether and how novelty fits within the collective identity:

There’s been a discussion about whether it is OK to have those ads [content marketing]. We’ve decided that it is OK as long as they’re clearly marked. But … when we, in a way, reduce the boundary between editorial content and paid content … there must always be a discussion about why we do it. And if we want it, even if we profit from it. … In the last few years, we’ve established a sort of standard in Norwegian media regarding how to mark such ads. Discussions have reached the level of the industry’s ethical board, which has helped us to develop guidelines. … The marketing law says that this is fine, but as journalists we wish to be as clear as possible [on the content distinction] (Niche/digital B).

The consequence of these collective negotiations was an updated identity that still revolved around public values but that was also more inclusive in terms of what providing public values means. For example, one respondent explained that the newspaper generated revenue by writing reviews of a company’s products. Having a commercial relationship with that company did not contravene the newspaper’s core mission, as it was a part of what they did as a newspaper company. The respondent emphasised that a balance was maintained because the newspaper could still write ‘critical articles about them’, as they wanted their readers to ‘feel safe that our [consumer] advice is the best, and that they therefore come to us when they have a practical question’ (Niche/digital B).

Updating and maintenance of identity reference points (6)

At the same time, the collective initiatives also led to the updating and maintenance of the collective identity reference points (i.e., the criteria concerning what was acceptable within the industry). The updated reference points enabled the further legitimation of innovations that potentially pushed the collective identity tied to the provision of public values even further, as indicated by the previous quotation. What years ago had been considered outside the realm of journalism or ‘not appropriate’ had become institutionalised at the time of interviews.

Role and impact of the ‘digital’ and ‘collective’ in terms of adapting to digital transformation within established industries

Two striking and complementary drivers of change and adaptation within established industries included in our model are the ‘digital’ (digital work/innovation) and the ‘collective’ (collective identity). We found the change process captured by the model presented in the previous section to be driven and affected by the interplay between these two drivers. Here, we will start by discussing the role of the ‘digital’.

The digital (role and impact of digital work/innovation)

The nature of the digital transformation and the digital technologies that the newspaper companies faced was a two-fold driver of gradual change. It drove the need for the newspaper companies to adapt to the threats stemming from new actors, new technologies and new business models. The conundrum related to digital transformation appeared gradually and then accumulated over time. This created persistent pressure to modify or replace activities and practices in order to address economic threats and sustain the core ideals of the collective identity. Although these challenges and pressures did not represent something completely new and did not occur at once, their sum can be conceived as a transformative force that gradually brought about changes in how the collective identity was communicated to society. As one respondent reflected, the new practices also implied the deterioration of the established identity: ‘For us, it’s been a constant transition and seeing – yes, the old model is actually dying’ (Larger/digital A).

At the same time, the nature of both digital technologies and digital innovation, as well as the nature of how the industry had become increasingly digitalised, required more proactive digital engagement to ensure long-term survival. The digital technologies and innovations allowed for a fast and generative change of activities (i.e., continuous stream of innovations with unprompted changes), which industry members with a deeply internalised identity struggled to control and understand. For example, while individual experiments and innovations allowed the newspapers to keep up with developments linked to their competitors, their readers and new technologies, they had only limited success in dealing with the ‘digital threat’ once and for all. No one had identified individual solutions that would ‘work well’ in the long run. Some experiments were described as ‘not well suited’ to readers, while others did not generate the expected revenue or else failed during implementation. The experimental solutions often became suboptimal following the evolution of digital technologies, and some claimed that early experiments had been rather short term and focused on immediate returns.

As a consequence, the newspapers had to learn how to be digital innovators. They learned to engage in continuous experimentation by exploiting the available digital tools and technologies as well as the collaborative innovation ethos within the industry. The increasingly digital practices and activities enabled the newspapers to go a step further and not only work digitally but also effectively generate digital innovation. The newspapers described their newsroom as a ‘workshop’ or a ‘laboratory’, with a ‘trial and error’ or ‘fail fast’ approach:

[New forms of journalism] became … like a workshop in the middle of the editorial team. We invested so that [the digital staff] could spend time learning new tools because things changed so fast. … Like when the graphic designer learned simple programming and new tools for visualisation, and when she was done we started experimenting (Local G).

Such an approach required internal changes, for example, the construction of some kind of innovation management system for continuous experimentation. According to this approach, failure did not cause an activity to stop. When novel products and services became ineffective, many were turned into ‘living products’ that constantly changed according to the reactions of users and advertisers:

Product development is now real-time. We test [new products] on our readers continuously, it has to be transparent … and open for discussion. It should involve testing, trial, failure … where everything should be allowed so long as we are able to terminate what doesn’t work. This is why I call it a laboratory. We need to try new things in full openness on our own platforms (Larger F).

Finally, the experiments shifted from large-scale projects (i.e., risky grand digital innovations such as early mobile phone or tablet projects aimed at solving the digital issue once and for all) to smaller-scale experiments based on ‘less enthusiasm’ and ‘more realism’. As one respondent stated, they started ‘with what we have in the fridge, rather than what’s in the cookbook’ (Larger/Digital A).

Thus, the nature of digitalisation and the gradual learning of how to be digital innovators effectively brought about streams of innovation that led to new identity traits related to digital innovation that expanded or at least challenged certain aspects of the existing collective identity, as described in step four of the model (). Despite the controversies surrounding some of the innovations, some respondents openly considered such innovations to be a necessary step for survival, claiming that they would become a new trait of the newspaper industry’s identity in the end:

We have to challenge the old way of distinguishing between editorial and commercial content, and we … have a job to do in terms of finding the right solutions to make that happen. And the readers too. They’ll become increasingly smart, and they will be able to distinguish between what is what, I think (Larger/digital B).

The respondents from other newspapers proved more reluctant to explicitly assign legitimacy to more radical innovations. In theory, the respondents told us that they valued independent and reliable journalism and so rejected attempts to violate that public value element. However, they also provided examples of having introduced innovations that clearly stretched the collective identity in such a way as to deviate from the core mission:

We try to follow the pattern of consumption when we post news. We also know that culture and sport do not sell well … we spend less on them today than we did just a year or two ago. … The conglomerate does research on this and suggests what we should prioritise. It’s breaking news, it’s housing, things to do with animals, or empathy. … To me, these are journalistic non-items, but that’s what people want. … . There’s no point in spending time on an article that no one else will read. If an item only gets 50 readers, it becomes a waste of time and a waste of money. So we need to go for the news that sells if we are to get many readers and maintain the position of [the local newspaper] as a news provider in the local community (Local M).

The reasons behind such changes were ‘harsh economic realities’ and the need to ‘create a sustainable platform within the current digital transformation’ (Local B).

In this sense, our findings indicated that the ‘digital’ (as a threat and an opportunity to be digital innovators) led to the coexistence of two versions of the collective identity: idealised and practiced. The practiced identity covers the actual changes in activities within the industry that the newspaper companies implemented to either survive and/or keep pace with the digital innovations within the industry. The idealised identity – strictly revolving around the provision of public values – remains an ideal that continues tying firms together as a collective even though the industry has changed and expanded. More specifically, the findings indicated that the nature of the digital transformation prompts changes in an established industry through the practiced collective identity. The economic threat motivates engagement in digital innovation. In turn, the nature of the digital innovation fuels further innovation and changes within both the industry and the collective identity. For example, identifying as media houses or multimedia actors (rather than newspapers) led to more digital innovation and new narratives regarding what was acceptable (or otherwise).

The collective (role and impact of collective identity on adaptation and innovation)

The idealised version of the collective identity helps the members of an established industry to function as a collective as well as to respond more effectively to digital transformation than an individual company could have done. We found that a strong collective identity motivates engagement in complex industry-wide processes related to mutual learning, coordination and acceptance. In doing so, it also helps to ensure survival by sharing the costs and complexities of experimenting with digital innovations. In fact, newspapers that are not part of a conglomerate described experiencing significant struggles in relation to accessing the competences and resources necessary to be competitive in a digital market:

It is possible to survive without being owned by a media group, but I don’t think it is possible to survive without collaborating with several … larger actors. We cannot innovate, and we depend upon our suppliers, who are not sufficiently good at innovation. We, therefore, need to collaborate with the groups. That’s our most important [innovation activity] going forward, our partnerships (Local A, independent).

More specifically, the idealised public value identity (which is seen as needing protection) makes firms function as one. Despite having the means to freeride and ignore discussions about the identity fit of problematic innovations such as hybrid journalism, the newspapers often failed to implement such innovations or else curbed the experimentation until it was collectively accepted by the industry (as shown in step five in the model).

One reason for abiding by the will of the collective was the short-term economic repercussions associated with breaking with both the collective identity and core beliefs regarding how the industry should work. The collective dynamic behind the introduction of paywalls represents an example of how not being part of the ‘team’ and failing to coordinate with other team members could backfire:

It’s hard to start charging for content when your main competitor does not do so. If [larger newspaper A] wants to charge for articles, it needs to constantly monitor whether [larger newspaper B] has similar articles openly available (Niche/digital B).

Another reason concerned the ‘moral repercussions’ that individual newspapers faced in response to introducing new forms of journalism. Many respondents argued that problematic innovations ‘tamed’ early innovators and undermined the implicit contract they had with their readers. Failing to abide by the majority perspective on collective identity was seen to undermine the public values embodied within editorial news and so to result in the loss of a competitive advantage in a transformed industry:

If [media users do not see the difference between journalism and advertising], the credibility of journalism could be damaged. This is crucial, … credibility is our main advantage when compared with all other information sources (Industry stakeholder B).

This suggests that tight collective actions occur even when industry membership expands and organisations adapt traits differently. The newspaper companies perceived value in being part of a collective, as it helped them to deal with specific challenges related to digitalisation as well as to engage in digital innovation. This further implies that, on the one hand, a collective identity driven by a strong ideal protects established activities and restricts unbounded digital innovation. On the other hand, it also enables change through collective actions. Our interpretation is that collective and open negotiations, acceptance of novelty and updates to the frame of reference served as crucial engines for adaptation and change within the industry during digital transformation as well as for retaining public values. Moreover, collective negotiation was a change mechanism with regard to the identity of the newspaper industry, as it enabled actions that reversed the tendency to preserve the traditional identity and so allowed for adaptation. This suggests that the continuous and collective process of innovation, negotiation and acceptance can lead to the gradual change and adaptation of an established industry undergoing digital transformation.

Discussion

In this paper, we examined how collective identity affects adaptation and innovation in terms of digital transformation in a particular setting in which the core of the identity contains a mission widely believed to serve a public interest (Bozeman, Citation2007). Recent studies have explored how organisational-level identity both shapes and is shaped by innovation (Anthony & Tripsas, Citation2016; Garud & Karunakaran, Citation2018), and an emerging body of literature has revealed that strong and uniform professional identities can lead to ineffective and path-dependent innovation processes (Grubenmann & Meckel, Citation2017; Hujanen, Citation2009; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). Yet, relatively little is known about how a shared collective identity can influence innovation, and our paper answers recent calls for a deeper understanding of the relationship between collective identity and innovation activities (Kavanagh et al., Citation2021).

The case of Norwegian newspaper industry

Our analysis shows that collective identity can change over time in the face of digital distress and, further, that innovation plays a key role in that change. However, the kind of innovation that appears to be effective is of an incremental and collaborative nature, rather than being a kind of grand and game-changing innovation capable of solving digitalisation issues once and for all. One reason for this is the fact that the embodiment of public values within the collective prevents the newspaper industry from engaging in sudden change or radical innovation. As we argued in the introduction to this paper, not all industries have an unlimited capacity for change. Newspapers are expected to perform a certain function in society, and their identity is tied to that function. For this reason, companies in other settings may be more flexible and faster in terms of adapting, for example, when Norwegian banks redefine themselves as ‘ICT companies’ or when oil producers strive to become ‘energy companies’.

Another reason for this pattern of change is that the increasingly digital work of the industry enables newspapers to gradually adapt by providing opportunities for incremental innovation and new work with readers. Thus, the present paper shows that an established industry with a strong identity that leans towards preservation can learn how to use the digital space to innovate and adapt in an effective way. Digitalisation is not solely an external threat that challenges established industries and their identities (Deuze, Citation2005), as established industries can become part of the digital transformation that previously challenged them. The outcome of this is that the retention of the collective identity is still emphasised, albeit with a more pragmatic approach to how it can be safeguarded. In other words, the provision of public values is still emphasised, although how and in what form they are provided may change, as the examples of hybrid journalism, niche news sites and new forms of advertisements indicate.

Our analysis of the collective identity and innovation within the digital transformation of the Norwegian newspaper industry is of relevance to other industries, for example, industries that are also believed to have a core mission related to public values or creative industries more generally. There are a number of similarities between the United States symphony orchestras described in the work of Kavanagh (Citation2018) and Kavanagh et al. (Citation2021) and the newspapers included in our analysis. Yet, the Norwegian newspapers seem to be doing better in financial terms, and they appear to be a lot more experimental and innovative in their approach to the new situation. This means that our findings can assist in understanding how industries that revolve around public and cultural values can effectively adapt as opposed to the prevalent view that they innovate solely to protect old business models (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018; Deuze, Citation2005; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014). One explanation for our finding that the newspaper industry engages in digital innovation as part of its collective identity change process could be that the Norwegian newspaper industry is highly digitalised and open to innovation when compared with newspapers in other national settings (see the case description in the Methods and data section above). A second explanation could involve the prominent role played by conglomerates in the restructuring of the industry for digital innovation purposes (Krumsvik, Citation2015; Krumsvik et al., Citation2013). Future studies could explore the exact impact of conglomerates on the industry dynamics of restructuring. This could provide important insights into how incumbents can self-organise within their industry and proactively contribute to digital transformation. Finally, another explanation for the innovative response of the Norwegian newspaper industry concerns sector differences. The provision of news more closely involves the provision of a product than a pure service, which may allow for a wider range of innovations. Future studies could explore how this notion plays out in other national and sectoral settings by designing comparative studies of different industries with strong collective identities that revolve around public or intrinsic values, such as art, heritage and education.

Digital transformation of the newspaper industry

Prior studies concerning the role played by collective identity in adaptation to digital transformation have highlighted how a strong collective identity tied to public or intrinsic values within established industries can restrict the response to a limited set of products and services in accordance with the core purpose and values (Kavanagh, Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2021). As a result, the identity can lead to limited change as well as controversies or the exacerbation of problems within the industry. The findings of our study indicated a slightly different role on the part of collective identity. We observed that collective identity has a double role: as a conservative and as a progressive force. It acts as a protector of core ideals related to the provision of public values by being a point of reference when it comes to engagement in new activities and innovations. Like earlier empirical studies, we found that such an identity leads to defensive innovations that protect core ideals (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018; Rothmann & Koch, Citation2014).

At the same time, we found that the collective identity is also a driver of adaptation in a different manner. The idealised identity functions as a ‘safety net’ for organisations when it comes to experimenting with how best to approach and deal with the digital transformation that they are part of. By tying organisations together, it helps them to work as a team. First, they learn how to adapt to the challenges associated with digitalisation by collectively making sense of how those challenges can be characterised. Second, they learn how to become digital innovators by sharing good practices and lessons learned from failures as well as by coordinating the next steps. Within these processes, the newspapers were primarily collaborators, which was probably made somewhat easier by the geographical spread of their readers, as local and regional newspapers mostly do not compete in the same markets, not even in the digital world.

Thus, our findings indicated that the motivation behind sustaining a collective identity tied to public values does not exist for solely idealistic reasons (Kavanagh, Citation2018) or to maintain coherent frames and understandings within the industry (Porac et al., Citation1989) – it has an economic rationale as well. Sustaining public values in the form of curated and independent news represents a source of competitive advantage relative to new actors (i.e., providers of information). While breaking free from the ties of the collective identity may offer complete freedom to come up with diverse novel products and services, it also implies losing the status of being a newspaper, in addition to readership and public support in some cases, as our findings suggested. We believe that it would be valuable for future researchers to design a comparative study of how newspapers that comply with the collective identity perform relative to the ‘outcasts’ as well as how the two groups differ in terms of their adaptations to digital challenges.

Digital transformation of industries

Based on the above-mentioned findings, our case extends the general understanding of the dynamics of the digital transformation of industries. First, our findings highlighted the collective nature of how an industry adapts and transforms. Moreover, the findings indicated that the collective aspect of learning was crucial for the industry to survive and begin thriving as a digital innovator. The need to adapt to digital threats and control the unprompted changes that digital transformation brought about is easier to handle as a collective than as an individual firm due to both cost and complexity. Future studies could examine the importance of collective action in other settings to understand whether this is a characteristic of established industries with strong identities or of established industries in general.

More specifically, our findings highlighted coopetitive innovation efforts at the industry level in the form of collaborative experimentation. The findings are, therefore, linked to recent calls for a deeper understanding of experimentation in the digital realm as well as its role in digital transformation (Appio et al., Citation2021; Bianchi et al., Citation2020; Hampel et al., Citation2020; Restivo & Cardoso, Citation2020). Thus, we have extended the prior research by emphasising the collaborative aspect of experimentation. In fact, the collective serves as a platform for experimenting with novel responses to digital transformation within an industry. In this sense, the findings of our study have served to bridge recent research concerning digital transformation dynamics at the industry level (Cozzolino et al., Citation2021, Citation2018) and research concerning digital experimentation within firms. Our case highlighted how experimentation is a necessary collaborative learning process across multiple levels that enables firms both to respond to threats and to actively become part of the digital transformation. Hence, experimentation transcends a solely strategic orientation (cf. Appio et al., Citation2021) and represents a multi-level and continuous adaptation process of a given industry to the nature of digital work and innovation. The learning aspect may explain some of the observed inefficiencies related to experimentation (Lanzolla et al., Citation2021). Overall, this highlights the need to study digital transformation and its dynamics across multiple layers, as some of its aspects may be lost when looking at only individual firms (cf. Lanzolla et al., Citation2020; Nambisan et al., Citation2019). In addition, our findings revealed specific industry-level dynamics to experimentation as both an adaptation and a strategic orientation. Different industry members take on distinct roles in these coopetitive processes when dealing with digital challenges in established industries. However, while elucidating the dynamics of these industry-level processes was beyond the scope of the present study, we do consider the matter worthy of further exploration, similar to the work of Cozzolino et al. (Citation2021). Future studies could investigate how roles and responsibilities are delegated in relation to collaborative experimentation as well as how issues such as appropriability and the alignment of interests are dealt with in multi-party collaborative or coopetitive innovation efforts.

Second, our findings indicated that the trajectory of the digital transformation of an established industry is shaped by its collective identity. We found that while the nature of digital innovation (openness, generativity and affordances) (Nambisan et al., Citation2017, Citation2019) offers the opportunity for radical change and a departure from the collective identity of established industries, the transformation itself is bounded. More specifically, we determined that digital innovation and collective identity mutually affect each other and have a joint impact on the trajectory and transformation of an industry. A strong identity limits the potentially unbounded and uncontrolled generative processes related to digital innovation and aligns them with the core identity traits. In our case, the generative, potential and open nature of digital technology (Nambisan et al., Citation2019) was curbed by the actors in instances in which it resulted in innovations that proved controversial in terms of the collective identity.