ABSTRACT

The Australian Government recently ‘upgraded’ the status of the koala across New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and Queensland from vulnerable to endangered. This change is a result of the impact of prolonged drought, bushfires, and the cumulative impacts of disease, urbanisation and habitat loss. In contrast, little is known about the status of koalas in the Clarke-Connors Ranges in Central Queensland. Land-use here is dominated by agriculture, in particular cattle-grazing, and extractive industries. A community-based postal survey of 160 landholders was undertaken between October 2021 and March 2022, with the intention to gauge attitudes and willingness towards koala conservation. The survey (∼14.86 per cent response-rate) revealed that landholders were generally aware of koalas living in the area. Most respondents perceived that today koala numbers are higher than in the past, or at least stable. The main concerns for koala survival were the threat posed by vehicles. Roaming dogs, pest animals and habitat loss were also mentioned. Support for habitat protection and restoration measures was expressed. We reflect that conservation is not just the responsibility of landholders but also of the wider community and we encourage the gauging of attitudes, awareness and behavioural change of koala conservation in the broader community.

Introduction

In 2022, the Federal Government ‘upgraded’ the listing status of the koala across NSW, ACT and Qld from vulnerable to endangered (Department of the Environment Citation2022). The long-term survival of the species in the wild is severely at risk, despite being a national icon, and decades of research and management activities outside of Central Queensland (CQ). There are several factors that led to the change in threatened status. In South-East Queensland (SEQ) for instance, the main impacting factors include loss and fragmentation of habitat (Department of Environment and Science Citation2022). These are compounded further by domestic dog attacks, koala-vehicle collisions, diseases and bush fires (Gonzalez-Astudillo et al. Citation2017). Most are compounded by anthropogenic activities (McAlpine Citation2011). Residents in these areas value the koala populations and have mounted multiple campaigns in an unsuccessful effort to increase protection for the species.

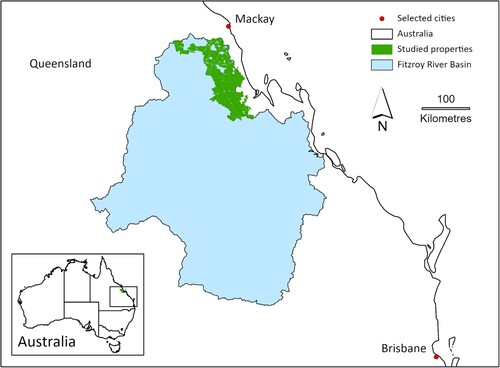

The National Koala Conservation Strategy (ANZECC Citation1998), supported by various federal, state and territory governments’ legislation, clearly acknowledges that protecting and managing koalas is a complex task. Much of the remaining koala habitat occurs on private land where there are many competing land-uses (Rhodes et al. Citation2015, Citation2017). In CQ specifically, very little is known about the distribution and conservation status of the koala (Gordon, Hrdina, and Patterson Citation2006). This population faces similar threats as in SEQ, but additional threats include weeds, which reduce suitable tree availability for koalas and restrict their movement on the ground, and large-scale fire events resulting from natural events or management mishaps. There are also large tracts of likely koala habitat occurring across the region, holding the potential to serve as koala habitat refugia (Adams-Hosking et al. Citation2011). One focus area is the Clarke-Connors Ranges (CCR), part of the Great Dividing Range hinterland west of Sarina and Mackay (). The CCR comprises one of the largest wilderness areas in the state. It encompasses some 6319.9 km², stretching from near Proserpine in the north to Clarke Creek in the south and Nebo to the West, with the exclusion of a narrow strip along the coast. Land-use in CQ, and the CCR, is very different from SEQ as it is dominated by agriculture, in particular cattle grazing, and to a lesser extent, extractive industries. Ellis et al. (Citation2022) point out that there is a lack of knowledge of the full extent, connectivity, or ecology of koalas and their habitat in this region. Landholders here hold different ideas of how land, including koala habitat, should be managed, ideas that have been shaped over generations. It is important and timely to capture these ideas and attitudes towards koala conservation in order that they might assist future koala management plans by capitalising on reported willingness to engage in conservation activities.

Human dimensions theories propose that there is a value–attitude–behaviour hierarchy (Fulton, Manfredo, and Lipscomb Citation1996), where people’s underlying values affect what type of attitude they hold and can help to explain their intention to participate in wildlife conservation. While environmental attitudes can to some extent influence behaviour towards conservation, there are significant limitations to this thinking. Heberlein (Citation2012) suggests that attitudes and behaviour are not well correlated. Setting and factors outside the individual can have far more influence on what people do than beliefs, knowledge or emotion, the drivers of attitudes. Attitude is often a necessary but not a sufficient condition for behaviour. Attitudes and behaviours are not the same thing. It is difficult to change attitudes and because attitudes have so little to do with behaviour, it is hard to change behaviour by using education to change attitudes. This is not to say that attitudes are unimportant. They shape the kinds of alternatives and policies available for social change (Heberlein Citation2012). We need to know more about attitudes, but we need to go beyond the simple notions that attitudes and behaviours usually correspond and that changing attitudes is the best way to solve environmental problems.

Likewise, Nilsson, Fielding, and Dean (Citation2020) admit that attitudes do not always translate into behaviour and therefore may not provide an accurate assessment of conservation program success. They argue that it is important to focus on influencing behaviour rather than attitudes alone, as this is more likely to achieve change. The koala is seen as a flagship species (Schlagloth et al. Citation2018) which makes it easier to collaborate with these stakeholders, which in turn has the potential for achieving behavioural change of more people to improve management of the habitat and the future conservation of the species.

Importance of surveying landholders

To a large extent, koalas share their habitat with humans and therefore are impacted greatly by anthropogenic influences. To protect this iconic species (Schlagloth et al. Citation2018), its habitat needs to be secured and collaboration with landholders is vital in this endeavour. Local landholders need to be engaged and involved with the conservation of local koala populations if such efforts are to be successful. A survey of property owners and/or the general community is a proven tool for initiating such engagement and has been utilised in previous projects (Close, Ward, and Phalen Citation2017; Lunney et al. Citation2009). In the early 1900s various stakeholder groups, including farmers, hunters and government officials were regularly surveyed for koala numbers and distribution to regulate the open koala-hunting season (Gordon, Hrdina, and Patterson Citation2006). Today, koala surveys are no longer used to gauge opportunities to hunt the species, but rather to maximise conservation efforts. Crowther et al. (Citation2009) used community survey data to compare species conservation strategies across regions. Most recently, funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program was used by Healthy Land and Water (Citation2021) for the ‘Protecting Koalas at Flinders Peak’ koala survey. It enabled the identification of suitable areas and willing landholders to facilitate various koala conservation actions in a particular area of SEQ. Using map-based or map-supported public surveys is a proven engagement tool for the purpose of introducing targeted management actions. Lunney et al. (Citation2009) used this method to allow for local and state plans, including the 2008 New South Wales Koala Recovery Plan, to be more effectively implemented and Harris and Goldingay (Citation2003) applied a community-based survey in Lismore, NSW. Their work was preceded by similar community-based surveys in the local government areas of Port Stephens in 1992 (Lunney et al. Citation1998) and Coffs Harbour in 1990 (Lunney et al. Citation2001) that identified community perceptions of changes in local koala populations, local threats to koalas and potential koala management options that were likely to be supported by the community (Lunney et al. Citation2001). A similar approach was taken in Ballarat before the introduction of a koala management plan, with a community-based postal koala survey receiving a very positive response, highlighting the importance that the Ballarat community placed on koala conservation (Schlagloth, Callaghan, and Santamaria Citation2004).

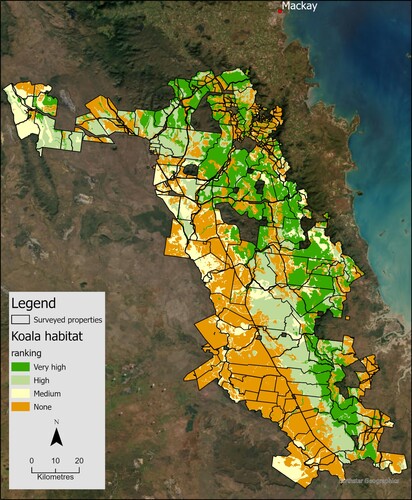

Ashman, Watchorn, and Whisson (Citation2019) stress that effective regional koala conservation needs to consider the effect of land-use management on long-term species survival, and alert to the additional need for reliance on location-specific information to inform strategies and to explain regional variations. To gain the support of the owners of the mostly very large agricultural and grazing properties within the CCR region, it is important to identify and map those properties where landholders are willing to engage in on-ground works to be funded or partly funded by this project. To achieve this, data needed to be obtained to identify where areas of high-value habitat coincide with landholders willing to undertake works, and to identify areas of high-value habitat where landholders do not express a willingness to participate, so that they can be approached separately. It was anticipated that working with these stakeholders will assist in reducing the known and identified threats to koalas in the Clarke-Connors Ranges. These actions are to be enhanced by targeted fire and biodiversity workshops and koala information events to strengthen the knowledge of, and commitment to, the conservation of local koalas by the community.

If we, as a society, are serious about wanting to protect koala habitat in these areas, we need to understand the origin and impact of community attitudes that have been shaped over time. The purpose of this article is to determine and explore such values and attitudes toward koalas amongst landholders in the Clarke-Connors Ranges of Central Queensland and to obtain information on current management actions and, particularly, willingness to engage in future management activities for the protection of koalas and their habitat.

Method

With the input from the Central Queensland Koala Advisory Group comprised of Regional NRM groups, Qld Department of Environment and Science and local government, koala experts, local land managers, wildlife carers and community groups, the Koala Research-CQ and the Fitzroy Basin Association (FBA) designed a mail-out koala survey that was sent to 160 landholders living within part of the Clarke-Connors Ranges, within the FBA management area (). The design of the survey considered previous, similar, surveys (e.g. the Healthy Land and Water Flinders Peak Koala Project Citation2021; Lunney et al. Citation2009; Schlagloth, Callaghan, and Santamaria Citation2004; Harris and Goldingay Citation2003).

Properties were selected using GIS-processed data and owners were identified from a publicly available database supplied by the FBA. Paper surveys were mailed out at the end of October 2021 and returned surveys were accepted via reply-paid mail, email or on-line through scanning of a QR code until the middle of March 2022. The survey (Supplementary Material S1) captured information regarding koala locations, landholder attitudes and knowledge of koalas as well as gauging willingness of the community to engage in further koala conservation actions.

Survey responses were transcribed into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analysed. Limited additional information was received via email from a few respondents who felt that they did not have sufficient space on the actual survey to elaborate. This information, where relevant, was added to the general comments section of the survey.

A detailed list of individual landholders willing to engage in selected conservation activities was generated and supplied to the FBA. This list was based on the extent to which landholders with koala habitat were willing to commit to certain koala conservation actions (e.g. weed control, fencing-off or revegetation of koala trees, fire management or protecting parts of their land as refugia). A priority list, based on demonstrable benefits for koala conservation, of these landholders interested in on-groundworks such as fencing-off or re-planting koala habitat, was also supplied. A list of 20 properties where management actions may benefit koala conservation, but where the owners had not responded to the survey was compiled and supplied to the FBA together with a map showing all properties with koala habitat.

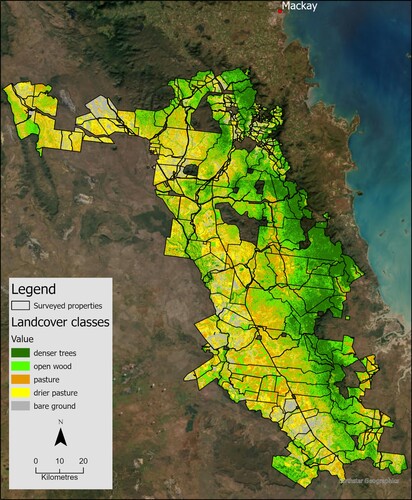

A plain-English summary of survey results was produced for distribution by the FBA to survey participants. Koala sightings reported as part of the survey, as well as other sightings for the area, were collated and their locations added to existing databases. The properties contained a range of koala habitat quality and landcover classes ( and ).

Figure 2. Survey site and koala habitat ranking classified by using Runge, Rhodes, and Latch (Citation2021).

Results

A total of 160 surveys were mailed out to property owners; of these, 22 valid surveys were received although not all respondents replied to all questions. Twelve surveys were returned as undeliverable, indicating that the landowners had not received the surveys rather than choosing not to reply. The response-rate of ∼14.86 per cent is low but fell within the expected range; other, similar postal koala surveys have achieved return rates between 10 and 15 per cent. This is considered a good rate of return for personalised postal surveys and makes it a representative sample (Sinclair et al. Citation2012).

Awareness of existence of koalas in their area

Most of the respondents were aware of koalas living in their area (91 per cent) or on their own property (79 per cent) and many (41 per cent) had observed koalas within the last week and nearly 73 per cent saw one within the past three months on their property or surrounding area. These observations were not isolated events as 59 per cent of respondents reported seeing koalas at least on a quarterly frequency.

Status of local koala population

When asked how important it was for respondents to have healthy wild koalas in their local area, 95.5 per cent gave it some level of importance (very important, important, moderately or slightly important) and overall, 72.7 per cent expressed that it was very important to them. Most of the respondents considered the local koala population to be stable (22.7 per cent) or to have increased (36.4 per cent) with the remaining respondents being not sure or not answering the question. Indeed, 45.5 per cent of respondents had seen female koalas with back young in their area but also the same percentage had seen sick, injured or dead koalas in the project area. Of those who encountered koalas in compromised situations, 40 per cent named ‘Vehicle strike’, 30 per cent ‘Dog attack’ and 30 per cent ‘Sickness/old age’ as the most frequent reason for these. It was clear that collisions with vehicles (cars, trucks, trains) were perceived as having the biggest impact on the local koala population (10 mentions), closely followed by bushfires (9) and predation (by dogs (5) and by feral animals (6)). Housing development (1), land clearing (4) and climate change (2) featured lower. However, respondents acknowledged that habitat loss was an issue, especially if one considers the comments made as part of the Other category: ‘Mines’; ‘Koalas moving in from west’; ‘Timber cutters sent in by government cutting all our gum trees’.

Survey respondents had ample suggestions on how they would see those threats being addressed and most involved tackling the issues head-on such as installing wildlife-exclusion fencing along the highway (6 mentions), more fire breaks/management (14) and weed control (11) on their own properties or tackling feral animals. Tree planting (6) for, and surveying (6) of, koalas was also suggested. It was also made clear that in some respondents’ opinions, cattle operations did not threaten koala populations:

All the local landholders that I know in the area seem to be quite proud and empathetic towards koalas. They are creatures that do not impact grazing operations in any way and are treasured for want of a better term.

Cattle grazing and koalas’ lives don’t seem to impact each other much. Except the benefits that they get from a well-managed grazing system e.g., fire management, pest control and access to water.

Willingness to help koalas

Aside from suggesting a range of practical management activities as suggested above, some respondents expressed interest in committing to further, more defined koala conservation measures such as attending information sessions or sharing their personal koala stories ().

Table 1. Respondents interested in participating in certain conservation/management activities (multiple answers possible).

Respondents also elaborated on current management actions that they were engaged in on their properties or that they were willing to perform in the future. Control of pest species and fire prevention/minimisation featured strongly for actions that were currently performed, while keeping records of koalas and allowing access to researchers on their property featured strongly for future actions ().

Table 2. Actions respondents were doing or were willing to do on their property (multiple answers possible).

Preserving koala habitat by placing a covenant or off-set protection over it is a commitment to protecting the koala habitat on one’s own property. A little more than one-third of the 22 respondents (36.4 per cent) were not in favour of this action or did not answer the question, however, 50 per cent indicated that they already had such arrangements (13.64 per cent), were very interested (4.54 per cent) or willing to learn more about it (31.82 per cent).

Respondents were keen to tackle weed issues on their properties. More landholders were prepared to engage in weed control (68 per cent) than were prepared to fence off areas to enhance koala habitat (31.6 per cent) with the same percentage willing to plant koala habitat trees. Weed control was favoured to be conducted over a large area of respondents’ properties i.e. >50 ha ().

Table 3. Respondents’ willingness to engage in weed control, fencing-off or revegetation, and area committing to allocate to these activities.

Comments show that many respondents believe that there is no need to increase koala habitat as their properties contain sufficient koala habitat trees and fencing-off is of little need or use as they consider that grazing activities have no impact on koalas:

No planting of koala food trees needed, we have too many.

Don’t see a need to fence to protect koalas, fencing would protect creek banks from erosion.

Koalas don’t eat grass/no competition. Fencing along highway is most important of all, greatest benefit of all.

In the 1990s a 70-year-old gentleman who had lived in Carmila all his life saw his first koala in this area, lots sighted since then.

Thousands of koalas are dying on our highways. The single greatest conservation strategy by far is to fence the Peak Downs Highway (Eton to Nebo) with wildlife fencing.

No fencing-off needed in 100,000 acres.

Don’t need towners upsetting them or our cattle. We are seeing them all the time – leave them alone.

Without a doubt to fence Peak Downs Highway from BP Junction Roadhouse (Nebo) to Eton Range with Wildlife fencing is the only way to stop the absolute carnage of these wonderful creatures.

Leave us alone, our biggest problem was when the government let timber cutters (leasehold) which resulted in quite a few deaths.

Cattle grazing and koalas’ lives do not seem to impact each other much. Except the benefits that they get from a well-managed from grazing system e.g., fire management, pest control and access to water.

Discussion

It is imperative to gauge and increase the public’s understanding and connection to nature if long-term conservation goals are to be achieved (Law and Ortac Citation2016) and the koala is a perfect flagship species to achieve such community engagement and education (Schlagloth et al. Citation2018, Citation2022). Without an understanding of what the presence of koalas, and by extension their conservation, means for landholders’ and community members, conservation efforts will continue to lack wide support. Such actions have been identified by the UN Sustainable Development Goals as being particularly important when attempting to overcome future sustainability challenges (Leal Filho et al. Citation2019). In fact, several comments made by landholders show that there is a lot of work to be done on understanding this stakeholder group (i.e. ‘We know what needs to be done – we don’t need city people to tell us what to do’). Therefore, we note that the next step requires careful communication, facilitating and planning with stakeholders and involvement of ‘trusted’ groups representing those landholders who may be reluctant to get involved.

The need for protection of remaining koala habitat on private property, and the willingness by landholders to participate in this, was highlighted by the responses from this survey, as were the identification of the various threats that local koala populations are facing. The important findings are discussed under four main topics: Koala sightings and knowledge, attitudes toward koala conservation, on-property koala management currently undertaken, and willingness to help koalas on their properties.

Koala sightings and knowledge

Survey respondents, and therefore by extension landholders in the Clarke-Connors Ranges, regularly observed koalas in the area and on their properties including many observations of female koalas with back young. They mostly viewed the koala population as being stable or increasing but subjected to several threats with the largest one being collisions with vehicles such as cars, trucks and trains; Law et al. (Citation2022) also identified road density as the major driver of koala occupancy on private land in NSW. While other threats such as loss of habitat, diseases and attacks from dogs were also mentioned, they appear not to be as prevalent as they are in other areas of the species’ range, including in SEQ. However, some threats are more easily observed than others especially in areas with low human population densities. There is little known about the distribution and health status of koala populations across CQ (Ellis et al. Citation2022) and feedback from landholders for the CCR needs to be scientifically verified. Hence, more research on threats to koalas in the CCR is warranted.

Other surveys for different states (Lunney et al. Citation2015, Citation2022) and other regions in Queensland (Charalambous and Narayan Citation2020) list evidence from wildlife carers and the general public that numbers (especially of female koalas with back young) are declining with diseases such as Chlamydia (which can cause severe ill-health including infertility) being the most likely reasons for these declines (Santamaria and Schlagloth Citation2016). The fact that many survey respondents observed female koalas with back young may indicate a healthier and more stable koala population, however, studies have shown that signs of Chlamydia are not always visible and develop when the animals are stressed due to environmental or other causes – a fact that should be investigated further as part of a larger population and health status study for the area including the potential role that Chlamydia vaccines may be able to play (Quigley and Timms Citation2021).

The perception of a local koala population being stable or having increased is of particular interest, as most koala populations, across the species’ natural range, are understood to have been decreasing, and hence the species is listed as threatened in much of its range. It would be beneficial to undertake a historical analysis of the population spread and density for the Clarke-Connors Ranges and supplement this with well-designed and replicated koala surveys (e.g. double count surveys/drone surveys), which should give an indication on current koala numbers in specific areas as a baseline for future surveys and to validate the effectiveness of the area functioning as a refuge for the species.

Koala sightings were mentioned regularly and throughout the survey, however, actual recording of these sightings was limited. A positive outcome of the survey is that interest was expressed by many people to participate in a formal process of recording future koala sightings, an opportunity that should be promoted through future koala conservation information sessions.

It was interesting to note that only one small reference was made to any potential impact that extractive industries may have on koalas and their habitat. This is possibly due to the main economic activity in the CCR being grazing and agriculture, and that large extractive industry activities are mostly located just outside of this area.

Attitudes toward koala conservation

Survey respondents did not generally report, and only few referred on, injured koalas, however, a willingness to engage in this conservation action was expressed and should be promoted as part of any koala conservation information sessions. This observation about a reported willingness to engage in conservation actions yet not many respondents referring-on injured koalas, highlights the difficulty of translating attitudes to behaviour change that is mentioned in the literature (Heberlein Citation2012; Nilsson, Fielding, and Dean Citation2020). Nilsson, Fielding, and Dean (Citation2020) argue for the need to assess behaviour rather than attitudes as an indicator of conservation outcomes. It is evident from the survey that injury and death of koalas through vehicular strike are important issues; there is an opportunity to collate various reports of such incidences, analyse these and disseminate the findings to landholders and other stakeholders while promoting the existence of the threat, its impact and potential solutions including the opportunities available for people to report such sightings and assist affected individual koalas. Collaboration with wildlife carers, veterinarians and government agencies is vital for the analysis of such data. Landholders felt that it is important to have a healthy, local koala population and they would be willing to engage in measures to protect the species for the future (a detailed list of individual landholders willing to engage in selected conservation activities was supplied to the FBA).

Respondents acknowledged that weed and fire management are two of the main actions needed to preserve the koala in the Clarke-Connors Ranges. Comments received showed that fires are frequent in the area, whether being wildfires, fuel reduction burns or accidental fires, with weeds, of course, playing an important role in fire behaviour. Such fires do not only affect koalas and their habitat but also assets such as livestock and infrastructure, and it is therefore no surprise that management actions relating to their control received significant attention.

On-property koala management currently undertaken

Respondents are already engaged in various management actions on their properties that benefit or may benefit koalas, although the benefit to the species might not be the primary aim of their actions, or it might not have been deliberately expressed on the form. Fire management and pest control are two of these actions. Others stated actions that are directly targeted at wildlife and koalas, in particular tree planting and the provision of water during times of drought or high temperatures.

Willingness to help koalas on their properties

While there was one concerned respondent to the survey who expressed the belief that koalas are better served without any interference from outsiders, most respondents were very keen on helping koalas on their properties and to cooperate with a variety of potential management actions suggested. Pest species, fire and weed management were the most popular actions selected by survey respondents. However, many were also very interested in allowing researchers onto their property, and in sharing their koala history and anecdotes, reporting and monitoring koala sightings. There was considerable interest in larger-scale (>50 ha) weed management and, to a lesser degree, larger-scale exclusion fencing. This response may be influenced by FBA’s accompanying information which alerted to potential funding to assist with certain habitat management actions. Many respondents were willing to receive additional information on what they can do to preserve koalas on their property including attending fire and koala conservation sessions. Koala conservation sessions, as part of community field days, where fire and weed management were discussed as tools to assist local koala protection efforts, have seen encouraging attendance and positive feedback. While there is anecdotal evidence that willingness has resulted in actions on the ground, there is room to formally analyse if it was successful and especially if these actions were maintained into the mid to long-term.

Limitations

Although a return rate of ∼15 per cent is considered good for personalised postal surveys and makes it a representative sample (Sinclair et al. Citation2012), a sample size of 160 (restricted to all landholders in the study area) and the views of a limited number of landholders (22) may be a limitation. However, the study was defined and limited specifically to the research requirements of the funding body under contractual obligations. We acknowledge that there may be a potential bias in this survey towards people who hold favourable views on koalas, or are passionate about koala conservation, as they are more likely to respond.

The other limitation of the study is that it reports on landholder attitudes towards koalas and their willingness to help in conservation efforts. Actual behavioural change as a result of attitudes is not straightforward, and innovative incentives may be needed to encourage landholders, noting their busy schedules, to modify their behaviour based on their good intentions and willingness towards koalas.

Future management

Our survey indicates that there is significant support for various koala conservation actions within the community. It is important to nurture the momentum that has been generated through this survey and involve other community members in the project. This can be achieved through the facilitation and promotion of fire and koala conservation information sessions and/or through on-property conservation and management actions which are likely to be noticed and valued by neighbouring property owners as well as through targeted research.

Some of these actions may involve short, medium and long-term tasks as suggested below.

Short-term (six months)

Sharing of survey outcomes

Only 13.6 per cent of respondents indicated that they had no interest at all in following up this survey by attending any information sessions or on-ground management actions. It is, therefore, vitally important to keep the survey respondents and the general community informed on the outcomes of this work; it is likely that participants will further communicate the information to family, neighbours and their business connections.

Contact individual respondents

There were two clear respondent groups, those who were interested in committing to on-ground weed eradication and fencing-off of koala habitat and those who were also interested in attending information sessions and engaging in specific wildlife conservation actions. It is important to contact both groups while the interest is still present (especially with the current raised national interest in koala conservation) and commit landholders to specific actions. It might also be an opportunity to engage with individuals and promote the uptake of additional measures. Such engagement has already been initiated by the FBA.

Analyse wildlife carer and BioCollect data for the CCR

While the respondents only supplied a few exact locations of koala sightings, many reported on multiple koala sightings in their properties. Unfortunately, respondents also identified the Peak Downs Highway as a serious issue for koalas. Koala road reports and the call for amelioration are mirrored by a study initiated by Transport and Main Roads and reported on by Schlagloth (Citation2018). Here, the link between high-quality koala habitat and its degree of fragmentation was shown to influence the likelihood of koala roadkill in so-called ‘blackspots’. Hence, it would be important to investigate if other koala roadkill blackspots exist in the CCR. Further research on how rescued koalas, subject to collisions with vehicles, fare in the care of wildlife carers would provide knowledge on the efficacy of the response measure. Such wildlife carer data would also provide data on other threats that may affect koalas such as diseases, fires and climate change. While such studies exist for other areas of the koala range, e.g. New South Wales (Charalambous and Narayan Citation2020), Victoria (Schlagloth et al. Citation1997) and south-east Queensland (Gonzalez-Astudillo et al. Citation2017), they do not exist for the important koala populations of CQ such as the CCR.

Medium-term (up to two years)

Contact property owners whose land contains high-quality koala habitat but have not yet indicated a willingness to engage in koala conservation actions

It is possible that not all landholders either received the survey, fully understood its intent or had the time to respond. There is an opportunity to engage more property owners in conserving koala habitat and koalas by facilitating habitat connectivity through various management actions proposed by this project. Contacting individual landowners, explaining the importance of their land in the context of local koala conservation (Law et al. Citation2022), encouraging participation in information sessions and explaining management incentives on offer, is necessary to increase habitat connectivity and potentially to reduce the extent of some of the threats that local koalas are exposed to.

Facilitate fire management and koala conservation information sessions

The survey revealed a considerable concern of the risk that fire poses to properties and koalas in the CCR. Several respondents expressed interest to attend future koala conservation and/or fire information and planning sessions. It is likely that, with appropriate promotion within the community, many more stakeholders and community members can be reached through such events and positive outcomes for koala conservation may be achieved.

Engage with community to achieve broader reporting of koala sightings

The general interest expressed by the community to report koala sightings should be nurtured. Contributions by the public to databases like BioCollect should be promoted through different means such as road-side signage, community newsletters and koala information sessions.

Record shared koala history

Koala management needs to be informed by historical recollections and past management practices. Several respondents indicated their willingness to participate in follow-up interviews to share past experiences and family anecdotes relating to local koala populations. Several additional comments were received via separate emails. Recording these stories is of interest especially considering that some landholders expressed their beliefs that koalas have increased in numbers in some areas over the past decades when the species was hunted to near-extinction during the early 1900s.

Long-term (up to 10 years – minimum)

Initiate a koala health study that monitors changes of impact of diseases and stress over time

Diseases are one of the main threats to the survival of koala populations. Stress can make individual koalas susceptible to disease and likewise, diseases can cause or enhance stress. It is difficult to treat disease in wild populations and it is therefore important to understand the prevalence of any particular disease within a population and assess their general health status. Koalas are difficult to capture, and the process in itself causes stress to the animals. Recent advances in koala health assessment methodologies (Santamaria et al. Citation2021, Citation2023) enable determination of cortisol levels (indicator of stress) from koala scats (faecal pellets) which is a non-invasive technique negating the need to capture and handle animals. Most survey respondents were willing to allow, or were already allowing, researchers access to their properties. With a recent announcement by the federal government for additional funding to investigate koala health and local landholders willing to allow access to researchers there are opportunities for community and stakeholder engagement and for exploring the refugia concept for koalas in this area.

Conduct regular (two to four-year interval) koala population monitoring studies

Many respondents stated that they had seen koalas with back young in the area; this, coupled with the general feedback that koala numbers are perceived to have increased over the past decade, is a very positive sign for the koala population in the CCR as it indicates a population that is breeding. However, these perceptions need to be confirmed (ground-truthed) and monitored. As koalas in this area often have large home-ranges, there is an opportunity here to compare various survey methods to cover large areas of habitat. For example, traditional walked-transects could be compared to drone surveys or the efficacy of koala detection dogs. Recently developed acoustic surveys are also effective over large areas (Law et al. Citation2018). Smaller control sites, e.g. individual properties, could be surveyed more frequently, e.g. every two years with a whole-of-range survey every four to five years. Koala numbers or population size are important components in the process of determining the status of a koala population to qualify for various categories on different threatened species lists.

Koala roadkill issue along Peak Downs Highway and other roads

Respondents identified the Peak Downs Highway as a great threat to koalas with one person having observed ‘Sadly, have seen 100s of dead koalas on Peak Downs Hwy’. The issue that the highway poses to the survival of koalas in that area has been acknowledged as part of the Clarke-Connors Ranges Koala Protection Program by the Department of Transport and Main Roads, which initiated a study into the movement of koalas in a section along the highway and the identification of koala roadkill blackspots along the road (Schlagloth Citation2018). While koala exclusion fencing and fauna underpasses have been installed along some parts of the highway, koalas are still being killed or badly injured by vehicles when they attempt to cross unprotected sections of the road. Koala records in general, and koala roadkill in particular, occur most frequently near high-quality koala habitat where there are likely to be more koalas at higher densities. Koala roadkill are also reported on the Bruce Highway around St Lawrence. There is an obvious need and scope for more research into the issue in conjunction with the managing authority, adjoining property owners and managers, and community stakeholders.

Monitor koala habitat – changes in extent, quality and health of koala habitat

The biggest threat to the long-term survival of the koala as a species is the loss and fragmentation of its habitat. Many survey respondents identified that their properties contained large tracts of koala habitat and that they were willing to fence parts of it off and/or replant areas with koala tree species. Although large tracts of koala habitat exist on private properties in the target area, strategic planting of koala habitat trees is likely to be worthwhile as they can function as corridors; studies have found that koalas will use them if near known koala populations (Rhind et al. Citation2014). With the recent listing of the species as endangered, there is extensive public funding available for restoration and land care activities to support the imperative. However, while tree planting can be an important restoration activity in many areas, some respondents pointed out that they have enough trees and tree planting is not a high priority. Therefore, tree planting may not be a priority action across all the CCR, and it may need further consideration before considerable funds are allocated exclusively to any one action.

Some respondents also pointed out that habitat was lost through fires. While koala, and wildlife populations in general, can be destroyed by fires, habitat impact is typically short-lived. It is known that fire severity has a substantial contribution to population impact with low-severity fires usually having very different outcomes to high-severity fire. Therefore, it is important to monitor the extent and quality of the koala habitat in the CCR especially after several large-scale fires in the recent past and in light of its assumed status as a koala habitat refuge and potential future pressures exerted by climatic changes. Such monitoring allows for targeted strategies to protect existing koala habitat and incentives for landholders to continue with proactive management to enhance koala habitat on their properties.

Conclusion

This study sought to obtain information on landholder perceptions of current and past distribution of koalas in the CCR, the perceived status of koala populations, and to ascertain the level of interest in various possible koala conservation measures. The survey was able to capture vital information on koala locations and their habitat, landholder attitudes toward, and knowledge of, koalas and the respondents’ willingness to undertake funded and voluntary koala conservation, and other biodiversity work, on their properties. Details of those stakeholders interested in attending fire, biodiversity and koala workshops were ascertained and the type of information, knowledge and advice that landholders are seeking was established.

The main outcome of this survey was the deep interest shown by respondents on environmental, wildlife and in particular koala issues in the CCR and the readiness of landholders to continue their vital contribution to preserving the koala in the area. However, conservation is not just the responsibility of landholders but also of the wider community (Moon, Adams, and Cooke Citation2019; Pannell et al. Citation2006). Therefore, there is also a need to gauge the attitudes and awareness of koala conservation in the wider CQ community. There are positive signs that the community is ready to embrace various funding and engagement opportunities to benefit long-term koala conservation in the Clarke-Connors Ranges.

There are opportunities for future research into various aspects of koala ecology such as the health and distribution of the local koala population, historical aspects and landholders’ personal anecdotes on encounters with koalas and the management of their habitat as well as the threats that koalas in some locations face such as near the Peak Downs highway.

It is recognised that imposing regulatory mechanisms to achieve strategic koala habitat restoration at landscape scales are likely to be ineffective when working with rural and regional landholders and this often results in strong resistance to the messages delivered (Rhodes et al. Citation2017). Rhodes et al., recommend targeted community engagement and extension activities that are developed and implemented at a regional level ensuring local cultural needs and circumstances are incorporated. It is evident that surveys such as ours are an essential tool to overcoming obstacles to local koala conservation initiatives in regional Queensland and they are essential to initiate the behavioural change needed to preserve the species.

Supplementary_Material_1_Koala_Survey_CCR.pdf

Download PDF (10.2 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams-Hosking, C., H. S. Grantham, J. R. Rhodes, C. Mcalpine, and P. T. Moss. 2011. “Modelling Climate-Change-Induced Shifts in the Distribution of the Koala.” Wildlife Research 38 (2): 122–130.

- Ashman, K. R., D. J. Watchorn, and D. A. Whisson. 2019. “Prioritising Research Efforts for Effective Species Conservation: A Review of 145 Years of Koala Research.” Mammal Review 49 (2): 189–200. doi:10.1111/mam.12151.

- Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council (ANZECC). 1998. National Koala Conservation Strategy. http://www.deh.gov.au/biodiversity/publications/koala-strategy/.

- Charalambous, R., and E. Narayan. 2020. “A 29-Year Retrospective Analysis of Koala Rescues in New South Wales, Australia.” Plos one 15 (10): e0239182. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239182.

- Close, R., S. Ward, and D. Phalen. 2017. “A Dangerous Idea: That Koala Densities Can be Low Without the Populations Being in Danger.” Australian Zoologist 38 (3): 272–280. doi:10.7882/AZ.2015.001.

- Crowther, M. S., C. A. McAlpine, D. Lunney, I. Shannon, and J. V. Bryant. 2009. “Using Broad-Scale, Community Survey Data to Compare Species Conservation Strategies Across Regions: A Case Study of the Koala in a set of Adjacent ‘Catchments’.” Ecological Management & Restoration 10: S88–S96. doi:10.1111/j.1442-8903.2009.00465.x.

- Department of Environment and Science. 2022. South East Queensland Koala Conservation Strategy 2020–2025. Brisbane: State of Queensland.

- Department of the Environment. 2022. Phascolarctos cinereus (Combined Populations of Qld, NSW and the ACT) in Species Profile and Threats Database. Canberra: Department of the Environment. https://www.environment.gov.au/sprat.

- Ellis, W., A. Melzer, S. FitzGibbon, L. Hulse, A. Gillett, and B. Barth. 2022. Australian Mammalogy. doi:10.1071/AM22026.

- Fulton, D., M. Manfredo, and J. Lipscomb. 1996. “Wildlife Value Orientations: A Conceptual and Measurement Approach.” Human Dimensions of Wildlife 1: 24–47. doi:10.1080/10871209609359060.

- Gonzalez-Astudillo, V., R. Allavena, A. McKinnon, R. Larkin, and J. Henning. 2017. “Decline Causes of Koalas in South East Queensland, Australia: A 17-Year Retrospective Study of Mortality and Morbidity.” Scientific Reports 7 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1038/srep42587.

- Gordon, G., F. Hrdina, and R. Patterson. 2006. “Decline in the Distribution of the Koala Phascolarctos cinereus in Queensland.” Australian Zoologist 33 (3): 345–358. doi:10.7882/AZ.2006.008.

- Harris, J. M., and R. L. Goldingay. 2003. “A Community-Based Survey of the Koala Phascolarctos cinereus in the Lismore Region of North-Eastern New South Wales.” Australian Mammalogy 25 (2): 155–167. doi:10.1071/AM03155.

- Healthy Land & Water, Flinders Peak Koala Project. 2021. Protecting Koalas at Flinders Peak – can you help? Koala Survey. Ann St, Brisbane.

- Heberlein, T. A. 2012. “Navigating Environmental Attitudes (Editorial).” Conservation Biology 26 (4): 583–585. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01892.x.

- Law, B. S., T. Brassil, L. Gonsalves, P. Roe, A. Truskinger, and A. McConville. 2018. “Passive Acoustics and Sound Recognition Provide new Insights on Status and Resilience of an Iconic Endangered Marsupial (Koala Phascolarctos cinereus) to Timber Harvesting.” PLoS ONE 13 (10): e0205075. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205075.

- Law, B., I. Kerr, L. Gonsalves, T. Brassil, P. Eichinski, A. Truskinger, and P. Roe. 2022. “Mini-acoustic Sensors Reveal Occupancy and Threats to Koalas Phascolarctos cinereus in Private Native Forests.” Applied Ecology 59: 835–846. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.14099.

- Law, M., and G. Ortac. 2016. “NPA Citizen Science and Community Projects.” Nature New South Wales 60 (2): 16–17.

- Leal Filho, W., S. K. Tripathi, J. B. S. O. D. Andrade Guerra, R. Giné-Garriga, V. Orlovic Lovren, and J. Willats. 2019. “Using the Sustainable Development Goals Towards a Better Understanding of Sustainability Challenges.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 26 (2): 179–190. doi:10.1080/13504509.2018.1505674.

- Lunney, D., D. Coburn, A. Matthews, and C. Moon. 2001. “Community Perceptions of Koala Populations and Their Management in Port Stephens and Coffs Harbour Local Government Areas, New South Wales.” In The Research and Management of Non-Urban Koala Populations, edited by K. Lions, A. Melzer, F. Carrick, and D. Lamb, 48–70. Rockhampton: Koala Research Centre of Central Queensland.

- Lunney, D., H. Cope, I. Sonawane, E. Stalenberg, and R. Haering. 2022. “An Analysis of the Long-Term Trends in the Records of Friends of the Koala in North-East New South Wales: II. Post-Release Survival.” Pacific Conservation Biology. doi:10.1071/PC21077.

- Lunney, D., M. S. Crowther, I. Shannon, and J. V. Bryant. 2009. “Combining a Map-based Public Survey with an Estimation of Site Occupancy to Determine the Recent and Changing Distribution of the Koala in New South Wales.” Wildlife Research 36 (3): 262–273. doi:10.1071/WR08079.

- Lunney, D., S. Phillips, J. Callaghan, and D. Coburn. 1998. “Determining the Distribution of Koala Habitat Across a Shire as a Basis for Conservation: A Case Study from Port Stephens.” New South Wales. Pacific Conservation Biology 4 (3): 186–196.

- Lunney, D., M. Predavec, I. Miller, I. Shannon, M. Fisher, C. Moon, A. Matthews, J. Turbill, and J. R. Rhodes. 2015. “Interpreting Patterns of Population Change in Koalas from Long-Term Datasets in Coffs Harbour on the North Coast of New South Wales.” Australian Mammalogy 38 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1071/AM15019.

- McAlpine, C. 2011. “Relationships Between Human-Induced Habitat Disturbance, Stressors and Disease in Koalas.” In Proceedings of Koala Research Network Disease Workshop. Queensland University of Technology.

- Moon, K., V. M. Adams, and B. Cooke. 2019. “Shared Personal Reflections on the Need to Broaden the Scope of Conservation Social Science.” People and Nature 1 (4): 426–434. doi:10.1002/pan3.10043.

- Nilsson, D., K. Fielding, and A. J. Dean. 2020. “Achieving Conservation Impact by Shifting Focus from Human Attitudes to Behaviors.” Conservation Biology 34 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1111/cobi.13363.

- Pannell, D. J., G. R. Marshall, N. Barr, A. Curtis, F. Vanclay, and R. Wilkinson. 2006. “Understanding and Promoting Adoption of Conservation Practices by Rural Landholders.” Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 46 (11): 1407–1424. doi:10.1071/EA05037.

- Quigley, B. L., and P. Timms. 2021. “The Koala Immune Response to Chlamydial Infection and Vaccine Development – Advancing Our Immunological Understanding.” Animals 11 (2): 380. doi:10.3390/ani11020380.

- Rhind, S. G., M. V. Ellis, M. Smith, and D. Lunney. 2014. “Do Koalas Phascolarctos cinereus Use Trees Planted on Farms? A Case Study from North-West New South Wales, Australia.” Pacific Conservation Biology 20 (3): 302–312. doi:10.1071/PC140302.

- Rhodes, J. R., H. Beyer, H. Preece, and C. McAlpine. 2015. South East Queensland Koala Population Modelling Study. . Brisbane, Australia: UniQuest.

- Rhodes, J. R., A. Hood, A. Melzer, and A. Mucci. 2017. Queensland Koala Expert Panel: A New Direction for the Conservation of Koalas in Queensland. Queensland Koala Expert Panel. A Report to the Minister for Environment and Heritage Protection. Brisbane: Queensland Government.

- Runge, C., J. Rhodes, and P. Latch. 2021. A National Approach to the Integration of Koala Spatial Data to Inform Conservation Planning, NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub Project 4.4.12 Report. Brisbane: The University of Queensland. Spatial Data and Supporting Documents. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4305157.

- Santamaria, F., and R. Schlagloth. 2016. “The Effect of Chlamydia on Translocated Chlamydia-Naive Koalas: A Case Study.” Australian Zoologist 38 (2): 192–202. doi:10.7882/AZ.2016.025.

- Santamaria, F., C. K. Barlow, R. Schlagloth, R. B. Schittenhelm, R. Palme, and J. Henning. 2021. “Identification of Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) Faecal Cortisol Metabolites using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry and Enzyme Immunoassays.” Metabolites 11 (6): 393.

- Santamaria, F., R. Schlagloth, L. Valenza, R. Palme, D. de Villiers, and J. Henning, J. 2023. “The Effect of Disease and Injury on Faecal Cortisol Metabolites, as an Indicator of Stress in Wild Hospitalised Koalas, Endangered Australian Marsupials.” Veterinary Sciences 10 (1): 65.

- Schlagloth, R. 2018. Managing Central Queensland’s Clarke-Connors Range Koala Population: Predicting Future Koala-Road-Kill Hotspots. A Report to the Department of Transport and Main Roads, Qld. Koala Research-CQ, School of Medical and Applied Sciences. Rockhampton: CQ University.

- Schlagloth, R., J. Callaghan, and F. Santamaria. 2004. Ballarat Residents-Koala Survey 2002. City of Ballarat, Victoria, Australia.

- Schlagloth, R., B. Golding, B. Kentish, F. Santamaria, G. Mcginnis, I. D. Clark, T. Cadman, and F. Cahir. 2022. “Koalas-Agents for Change: A Case Study from Regional Victoria.” Journal of Sustainability Education 26 (2): 1–16.

- Schlagloth, R., F. Santamaria, B. Golding, and H. Thomson. 2018. “Why is it Important to Use Flagship Species in Community Education? The Koala as a Case Study.” Animal Studies Journal 7 (1): 127–148.

- Schlagloth, R., F. Santamaria, A. Melzer, M. R. Keatley, and W. Houston. 1997. “Vehicle Collisions and Dog Attacks on Victorian Koalas as Evidenced by a Retrospective Analysis of Sightings and Admission Records.” Australian Zoologist 42 (3): 655–666.

- Sinclair, M., J. O’Toole, M. Malawaraarachchi, and K. Leder. 2012. “Comparison of Response Rates and Cost-Effectiveness for a Community-Based Survey: Postal, Internet and Telephone Modes with Generic or Personalised Recruitment Approaches.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 12 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-132.