ABSTRACT

This article examines policy capacity for dealing with the effects of climate change. The case under study is the Delta Program in the Netherlands; a large-scale policy program to prepare the country for current and anticipated effects of climate change that runs until 2050. Using a qualitative case study approach, we examine how the actors involved design analytical capacity, operational capacity and political capacity to deal with the uncertainty and complexity that are inherent in this policy field. The context of climate change necessitates policy capacity that anticipates effects that are in themselves uncertain and ambiguous, span over decades of time, and involve many stakeholders. Our analysis shows how policy capacity was designed to allow for present-day interventions, while also enabling adaptation to new and emerging developments overtime. We conclude our article with theoretical and practical lessons about policy capacity for dealing with long-term uncertainty and complexity.

Introduction

This special issue focuses on the capacity to anticipate what could happen during the process of policy implementation and pre-address it through policy design that is ‘prepared’ for it (Poli, Citation2017). In this vein, anticipating policy success means designing policies in a way that makes positive policy feedback more likely than negative policy feedback. Policy effectiveness can never be entirely predicted, but policymakers can take steps to enhance their chances of success.

In this article, we examine a design process that attempts to anticipate policy success for an issue that is highly complex, has a very long time-horizon and encompasses interventions and instruments with a long lead time; dealing with the effects of climate change. These conditions greatly complicate the effort to anticipate; complexity and non-linear dynamics make it impossible to foresee all of the possible futures of the issue; the long time-horizon enhances the space for complexity and widens the range of possible outcomes; the long lead time of possible interventions presses the policymaker for time, since in order to ‘pre-address’ a development of the design process needs to start early. This set of conditions makes it impossible to entirely pre-address potential policy dynamics, simply because they cannot be foreseen.

The impossibility of foreseeing dynamics makes climate adaptation policy a suitable case to study anticipatory policy design; even though the actual effectiveness of the policy remains to be seen. Examining how policymakers anticipate policy success in spite of all the ambiguity and complexity of the issue may enrich our understanding of long-term design processes and their characteristics, in extreme as well as less extreme policy domains. The following research question guides our study:

What are the design characteristics of policy capacity building for anticipating future effectiveness amidst deep uncertainty?

The remainder of our article is structured as follows. First, we build a framework for analyzing policy capacity by tailoring an existing framework to the context of ‘anticipation under deep uncertainty’. Second, we study the case of climate change adaptation policy in the Netherlands. We examine and discuss the different elements of policy capacity in the case. Finally, we critically discuss what this case teaches us about anticipation of policy success under conditions of deep uncertainty.

Theoretical framework

Policy capacity

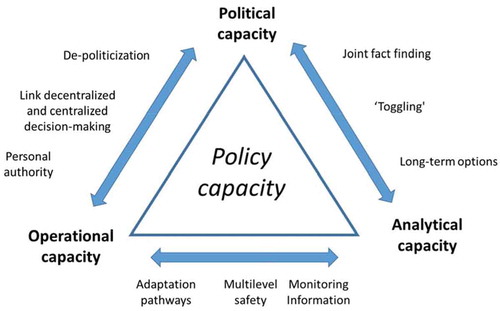

Dealing with climate change requires policy capacity. Wu, Ramesh & Howlett (Citation2015, p. 166) define policy capacity as ‘the set of skills and resources – or competencies and capabilities – necessary to perform policy functions’. They distinguish three necessary types of capacity; analytical, operational and political capacity, applying to three levels; the individual, organizational and systematic level (see ).

Table 1. Levels and competencies of policy capacity.

Policy capacity is ‘what results from the combinations of skills and resources at each level’ (Wu et al., Citation2015, p. 168), while the interplay between different competencies helps to better understand cases of policy failure or success. According to the authors, studying the interplay in concrete cases can add to our insights about the design of effective policy capacity. In this article, we use this framework of policy capacity to analyze the process and design choices made in the case of climate adaptation policy in the Netherlands. However, before we do that it is important to align the framework to the specific set of complicating factors for anticipating success in the context of climate adaptation policy. We will discuss these factors here.

Complicating factors for anticipating policy success

As a policy problem, handling the effects of climate change is complex (Biesbroek et al., Citation2010; Bloemen, Reeder, Zevenbergen, Rijke, & Kingsborough, Citation2017; Peters, Citation2017; Teisman, Van Buuren, & Gerrits, Citation2009; Van Der Steen, Vink, Chin-A-Fat, & Van Twist, Citation2016); the problem involves many actors and factors that interact and, therefore, produce non-linear dynamics in the system (Head & Alford, Citation2015). Overtime, many interactions and non-linear dynamics may render it impossible to oversee or predict future conditions. Walker et al. (Citation2010) refer to this condition as deep uncertainty. In situations of deep uncertainty, experts and stakeholders cannot agree upon (i) the external context of the system, (ii) how the system works and its boundaries and (iii) the outcomes of interest from the system and/or their relative importance .

Deep uncertainty is problematic for anticipating policy effectiveness because it causes what Lindblom (Citation1979) refers to as policy myopia (Nair & Howlett, Citation2017). In the case of policy myopia, a policymaker cannot foresee the effects and conditions of policy into the future, not because of ‘bounded rationality’ (Simon, Citation1997 [1945]) or a lack of information, but because it is inherently impossible. In the same vein, authors distinguish between ‘informational uncertainty’ and ‘ambiguity’ (March & Olsen, Citation1989; Weick, Citation2000). Policy capacity for dealing with the effects of climate change involves dealing with the inherent ambiguity that results from the combination of complexity and time (see also Van Der Wal, Citation2017).

Indeed, in the case of climate change, policymakers have to discount effects that are spread out over a long time-line (Peters, Citation2017; Hulme, Citation2009). Action in the present is needed to avert harm in the future, requiring policymakers to somehow take the future into account when planning contemporary solutions. However, there is little agreement on the best measures and instruments that policymakers can fall back on (Capano & Woo, Citation2017; Howlett & Ramesh, Citation2014).

Moreover, policymakers will also be pressed for time. They will have to come to a solution ‘in time’. However, what that means is dependent on the time it takes to build responses (Peters, Citation2017). As interventions to prepare for climate change have a long lead time – they take years or even decades to be designed, planned and build – policymakers cannot afford to wait too long; they need information that informs them of imminent challenges early.

Insights from climate adaptation policy

These complicating elements of climate change policy have been translated into a variety of frameworks for policy capacity. Such frameworks combine elements of anticipatory and adaptive capacity; they take into account existing knowledge and deliberately plan capacity to be adaptive along the way (Walker et al., Citation2010, Bloemen et al., Citation2017; Buurman & Babovic, Citation2016; Howlett & Mukherjee, Citation2014; Haasnoot, Kwakkel, Walker, & Ter Maat, Citation2013; Haasnoot, Middelkoop, Offermans, Beek, & Deursen, Citation2012; Walker, Haasnoot, & Kwakkel, Citation2013).

In climate adaptation policy, the term adaptation is used in two different ways. In the context of climate change, it refers to measures that prepare for the consequences of a changing climate; eg the heightening of sea dikes in response to sea level rise. The alternative use of the term refers to an adjustment of a plan following insights that emerge along the way; eg the adjustment of a plan for an initially modest expansion of an airport in order to accommodate a much sharper increase in demand. In this article, we use the term ‘climate adaptation’ for measures that address effects of climate change. For the act of adjustment of a plan to accommodate new insights, we use the term ‘adaptation’.

A similar issue concerns the use of the adjective ‘adaptive’. It is often used as the opposite of ‘transformational’, in which case adaptive resembles ‘incremental’. In the alternative use the term indicates that a plan is not based on static conditions, but explicitly takes unpredictable developments into consideration. Walker et al. (Citation2010) describe adaptive policies as a combination of taking steps towards an intended goal, combined with the build-in ability to deviate from those same steps if necessary. We use this latter definition; adaptiveness refers to the deliberate ‘act’ to design a system that takes unpredictability as given.

In the field of climate adaptation policy and research, different types of approaches for dealing with policy myopia have evolved (Vink et al., Citation2013a; Petersen & Bloemen, Citation2014; Mees et al., Citation2012; Warner, Citation2008; Botzen & Van den Bergh, Citation2008). For long, policymakers developed static ‘optimal’ plans based on a ‘most likely’ future generated from trend-extrapolation. Or they produced ‘static robust’ plans that work favorably for ‘the most plausible future worlds’ (Haasnoot et al., Citation2013: p. 485; Koningsveld, Citation2008). However, static robust approaches rely heavily on the ability to predict future dynamics with some level of accuracy. Therefore, policymakers looked for more ‘adaptive strategies’ that rely less on prediction and more on the ability to respond to dynamics that emerge (Maier et al., Citation2016:55; Beh et al., Citation2015; Groves et al., Citation2014; Haasnoot et al., Citation2013; Citation2014; Hamarat et al., Citation2014; Swanson & Bhadwal, Citation2009; Lempert and Groves, Citation2010). In short, two fundamentally different approaches have emerged to policy design under conditions of deep uncertainty:

Static robust approaches; policy design involves choosing a fixed time horizon (eg 2050) and defining a set of measures that prepare for specific future conditions. It is assumed the strategy will be implemented as designed and no adjustment along the way will be necessary.

Adaptive approaches; policy design involves choosing short-term measures (eg heightening sea dikes) and a set of monitoring criteria for keeping track of developments that might require increasing or decreasing efforts (eg acceleration in sea level rise). It is assumed external conditions will change and require policy adjustments.

From here, many approaches for dealing with deep uncertainty of climate change have developed; some accentuate robustness of plans and focus on eliminating factors that can make the plan fail (eg Info-Gap Decision Theory, Robust Decision Making, Decision Scaling); others accentuate adaptiveness and aim toward timely adjustments of the plan. The Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways (DAPP) is an example of the latter; DAPP consists of an overview of alternative routes into the future, called ‘adaptation pathways’ (Haasnoot et al., Citation2013).

Adaptive approaches start from the notion that complex dynamics will inevitable turn out differently than can be expected beforehand (Walker et al., Citation2010). Therefore, anticipation of effective policy relies on the pre-designed ability to deal with changing conditions or sudden shocks (eg Walker et al., Citation2013; Walker et al., Citation2010). That puts a strong focus on information to signal changing system dynamics, instead of information that predicts possible routes into the future. To do so, adaptive approaches often work with ‘triggers’; a trigger is a signal that ‘potentially affects obligations to integrity’ of the system (Sowell, Citationin press, p.19).

Triggers can be reactive in nature (‘stochastic triggers’) and proactive (‘periodic triggers’) (Hart, Citation1994). Periodic triggers are clock-driven; for instance, to review flood protection standards every 12 years. Stochastic triggers are ‘the direct product of active, continuous monitoring of a system for events that may impact the integrity of system’ (Sowell, Citationin press: 19); they are reactive. Sometimes, stochastic triggers are directly related to adaptation pathways (Haasnoot et al., Citation2013).

Because of the role of information, an adaptive approach requires a process for monitoring the main policy challenge overtime. However, that is not the case for all deep uncertainty themes; some are process-dominated, others more event-dominated. In process-dominated themes the driving force can be discerned as a pattern. Examples are the introduction of self-steering cars; the number of cars can be monitored overtime and disruption is to some extend visible. In event-dominated themes there are no timelines indicating an increase or decrease of the challenge; rare, individual events drive the dynamics in the system; eg large earthquakes or tsunamis.

For process-dominated themes, both types of approaches (static robust and adaptive) can be applied. Because event-dominated themes can only be ‘seen’ in sudden outbursts, a static robust approach is likely to be more effective than an adaptive approach. provides a tentative categorization (Bloemen, Citationin press).

Table 2. Application of approaches to issues of deep uncertainty (Bloemen, Citationforthcoming).

The practice of working with adaptive climate change policies shows that organizational aspects play a major role in the willingness and ability to apply adaptation. In the case of an adaptive approach, for example, the bureaucratic apparatus needs to be prepared to execute the resulting adaptive policy recommendations. McCray, Oye, and Petersen (Citation2010) indicate that an adaptive approach requires an operational, bureaucratic apparatus that is geared to the process of adjusting strategies and plans (‘planned adaptation’). In order to avert from path-dependency, resources and processes need to be in place to act on new knowledge.

Policy capacity to anticipate success amidst uncertainty

In this article, we aim to produce novel insights about policy capacity that is designed to deal with an uncertain future by analyzing the Dutch Delta Program. To build our framework for analysis, we now link the different approaches for dealing with deep uncertainty developed in the field of climate adaptation research to the interplays between the competencies of policy capacity (Wu et al., Citation2015).

Analytical ⇔ operational

Adaptive strategies for dealing with deep uncertainty require information about changing patterns in the system. Information can be collected ad hoc, but a system of triggers and properly allocated and funded research capacity seems necessary. This includes a system of relations between knowledge and policy-making processes, in order to avert the risk of path-dependency or lock-in in bureaucratic procedures.

Political ⇔ analytical

Adaptation suggests that policy is adapted along the way, by means of information about changing patterns in the system. Therefore, political decision-making should to some extend be ‘information-based’ or even ‘evidence-based’. There should be a tolerance for knowledge in political decision-making, instead of ‘fact free politics’. Ideally, there is some level of agreement among political decision-makers about the range of facts and information resources that underpin political debates (Vink, Dewulf et al., Citation2013b).

Operational ⇔ political

In order to systematically adapt and reconsider policy, procedures and protocols have to be in place for political debate about policy changes. In addition, such debate requires an attitude and a political culture in which policy adaptation is seen as success rather than failure; policy proceeds ‘as planned’ when it is adapted. This does not happen ‘naturally’, but probably requires operational capacity to prioritize and facilitate political decision on adaptation of policy.

Next, we examine the genesis, formulation and implementation of climate adaptation policy in the Netherlands to draw lessons for the design of policy capacity for an uncertain future. We will examine two issues in particular; (1) the central approach to the process of climate adaptation and (2) the key policy capacities employed by the lead actors for anticipating the effectiveness of this approach. Examining these two issues helps us to answer our central research question.

Case study: the Dutch Delta Program

Background

In 1953, a disastrous flood struck the Netherlands with catastrophic consequences: 1836 people drowned, 47,000 homes and 500 km of dykes were destroyed, and many acres of fertile agriculture land were ruined by salt water. The damage amounted to 10% of GDP. To prevent such a future disaster, the first Delta Commission came up with a master plan. They designed what became known as ‘The Delta Works’; a comprehensive and iconic set of waterworks, dykes and coastal protection works to manage the water and protect the land against storm surges.

However, from the early 2000s, new challenges for water governance emerged. There was a serious backlog in the maintenance of the levees. Soil subsidence and climate change were recognized as important long-term challenges. Although the every-day risk of flooding was largely under control, new threats challenged the notion of control. Many actors in the field of water management shared the idea that ‘something should be done’, with stakeholders discussing the need for ‘a new water vision’ and ‘a regeneration of water management in The Netherlands’, but there was little consensus about specific actions (Van Alphen, Citation2016).

Debate accelerated in 2005, when hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans. A critical review of flooding risks also renewed attention for the subpar conditions of some of the existing water works. In addition, experts called for a new and updated set of standards for water works. These standards were based on the size of the population and value of investments in the early 60s and did not take possible effects of climate change into account. (Schultz Van Haegen & Wieriks, Citation2015).

The call for a second delta commission

These internal reflections coincided with questions from the Ministry of Finance about the budget for water works, and the Dutch Senate passed a resolution urging the government to come up with a long-term strategic plan in relation to the changing climate (Van Twist, Schulz, Van Der Steen, & Ferket, Citation2013). In response to the Senate motion, the national program Climate Adaptation and Spatial Planning (ARK) was set-up. Uniting the four levels of government and the knowledge institutes on that subject, the ARK Programme, produced the first Dutch National Adaptation Strategy (NAS).

The final draft was discussed and approved by the cabinet of ministers 2007. In the NAS flood safety was identified as one of the most pressing of four issues that had to be addressed.Footnote1 The combination of the attention for climate change labeled dramatic events abroad, and the processes set-up by the ARK Programme for drafting the NAS of the Netherlands, further increased the public and political attention to the issue of climate adaptation (Vink, Boezeman, et al., Citation2013a).

Attempts to use the preparatory negotiations for the new national government (early 2007) to claim a budget of € 500 million for adaptation measures, as part of the €20 billion proposal for a National Spatial Investment Agenda,Footnote2 had failed. The proposal was never officially formalized and did not make it to the negotiation table. Therefore, this ‘execution-pillar under the ARK Programme’ never saw the light. A strong lobby for building a large research program, consisting of researchers and policymakers involved in the ARK Programme, was more successful. The Knowledge for Climate Programme was granted a budget of €50 million under the condition that the same amount of financing would be made available by the users of the knowledge that would be developed. That condition was fulfilled. The ‘research-pillar under the ARK Programme’ outlived the ARK programme and successfully produced relevant insights in the period 2008–2014.

Developing a constituency for change might be a pre-condition for political commitment – but does not automatically lead up to it. The constituency for change was growing but a substantial political commitment to founding a major climate adaptation program apparently required more than that. The grand politically mobilizing perspective was still missing. The initiative for generating that perspective would not come from the department of Housing, Spatial Planning and Environment that had the lead in the climate adaptation dossier with the ARK Programme producing the NAS, but from the ‘competing’ department of Transport, Public Works and Watermanagement.

Subsequently, the newly formed cabinet Balkenende IV called for more attention to the Dutch flood safety. To instigate that discussion, the Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management published its new ‘Water Vision’ (Cabinet Balkenende, Citation2007), laying the foundation for a new Delta Commission, and translating the vision into a request for advice on the expected increase in sea-level rise, and in the discharge of the large Dutch rivers and other climatic and social developments from 2100 to 2200 considered important for the Dutch coastline, their implications and a concurrent strategy for the sustainable development of the Dutch coastFootnote3:

This assignment gave the Commission an interventionist character. However, the rather constrained assignment appeared problematic to the Commission. Therefore, it decided to redefine its assignment, for four reasons in particular:

The time horizon of 2200 was exceptionally long and the Commission feared that the long horizon would limit societal and political urgency for the required investments (in addition to making it hard to come up with sensible claims amid so much future uncertainty).

Analysis showed that most of the climate change related problems would not emerge on the coastline but along the rivers. Accordingly, the Commission extended its geographical scope.

The Commission wanted to move away from the crisis-prevention frame implied by the original assignment and reframed its assignment accordingly into an adaptation frame.

The Commission redefined its scope to the safeguarding of the future prosperity of the Netherlands in view of climate change, and with that took a more economic and social approach to the issue (see also: Boezeman, Vink, & Leroy, Citation2013), hesitant to position itself as a mere ‘Climate Commission’.

Research and dialogue about contested facts and priorities

The Commission wanted to ground its work in ‘state of the art’ climate research. Therefore, the Commission consulted a broad range of climate experts and asked the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) to apply the scenarios of the effects of climate change to the specific situation in the Netherlands, and to calculate additional scenarios that deviated from the commonly used IPCC-scenarios (see also: Vellinga, Katsman, Sterl, & Beersma, Citation2008). In addition, the Commission combined climate change scenarios with economic and societal scenarios about the consequences for the ‘earning capacity’ of the Dutch Delta.

Parallel to the Commission work and dialogue with key societal actors (see also: Boezeman et al., Citation2013), senior policy managers at the Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management started to prepare the ground for a ‘safe landing’ of the Commission’s proposals. This was an interesting move, as the Commission had not yet taken any formal position. It may explain why some common bureaucratic competency challenges were mitigated in the early stages of the policy process.

Lastly, the Ministry organized a series of ‘free-thinking dialogues’, allowing government officials, water boards, civil servants, the secretariat and members of the Commission, and private engineering firms to discuss potential conclusions of the report. Actors participated on the basis of confidentiality. The Commission was informed of the sessions but had no formal relationship with them.

Institutionalization as part of the commission’s recommendations

In September 2008, the second Delta Commission published its final report, issuing fierce warnings about climate change being a real threat to the Dutch economy (Delta Commission, Citation2008c); but also of a plan to go forward (Delta Commission, Citation2008d; Vink et al., Citation2013a; Boezeman et al., Citation2013). Because the Commission feared that attention would quickly fade away, it proposed substantial institutional changes in Dutch water governance (Delta Commission, Citation2008a). They recommended setting up a Delta Program managed by a Delta Director, financed by a Delta fund, all backed up by a specific Delta Act. A leaked memo from the Commission revealed speak about the Delta Director as a ‘Delta Dictator’, someone positioned in between the Minister and the Cabinet, and the bureaucracy (Delta Commission, Citation2008b).

All of these institutional proposals intended to do the same thing; move the Delta program away from every-day political and administrative battles over short-term interests and financial resources. This way, the Commission not only succeeded in communicating the content of the issue, but also in building a coalition of interests and the political clout to support it. It also proposed an institutional arrangement to safeguard its recommendations way beyond the initial momentum.

Almost all key stakeholders adopted the proposals of the Commission, and despite the unfolding global economic crisis, Parliament accorded the institutional proposals, the Delta Act and the fund, providing a structural, substantial and depoliticized stream of funding: ‘A solid Delta fund will be set up, which will make a fast implementation of the Delta Program possible through a structural money flow of at least € 1 billion annually from 2020’ (Ministry of General Affairs, Citation2009). The act would also back up the Delta Director as a central coordinator located above all administrative parties. This institutional position for a long-term issue that is existential for the Netherlands was a novelty in the Dutch governmental landscape.

Policy design: choices and implementation

Decentralized design spaces within centralized parameters

Strategies for flood safety, freshwater supply and spatial adaptation needed to be designed in a way that would reduce the chance of both under- and overspending. To that end, capacity to adapt was deliberately built in the policy design. These strategies had to be a regional elaboration of stable overarching decisions, focusing on 2050, while keeping possible conditions in 2100 in mind. These overarching Delta decisions. Regional strategies were defined as a coherent set of goals, measures and indicative planning, the measures of which were combined in cohesive Delta plans (Delta Commissioner, Citation2014).

Program teams of policymakers from ministries, water boards, municipalities, provinces and often also societal partners developed the regional strategies. An overly narrow and centralized approach for dealing with uncertainties across regions would contribute to consistency, but it would also hurt the ability for local tailoring and regional buy-in. That is where Adaptive Delta Management came in. This approach allowed maximal design-space within the boundaries of the principles of the Delta Program. It was developed iteratively while regional strategies were developed. The inclusion of the different levels of government and societal stakeholders helped to mobilize support and overcome the paralyzing effect of large uncertainties and politicized discussions.

Parallel pathways of adaptation and long-term options

Adaptive Delta Management (ADM) was founded on the core values of the Delta Program, solidarity, flexibility and sustainability (Slob and Bloemen, Citation2014) and used elements of the Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways approach (Haasnoot et al., Citation2013, Citation2012). This approach became the default option for dealing with long-term uncertainty and strategy (Jeuken and Reeder, Citation2011).

ADM follows an adaptive and integrated approach, also referred to as ‘adaptive-by-design’. Here, adaptive refers to the capacity to speed up or temporize the implementation of measures or switch to a different strategy altogether, if developments so dictate (Dessai & Van der Sluijs, Citation2007; Van Buuren et al., Citation2013). The four key features of ADM are connecting short-term decisions with long-term objectives, developing adaptation pathways, looking for and ‘rating’ flexibility and linking measures with other investment agenda’s (eg ageing infrastructure, urban development, nature, shipping and recreation) (Delta Program Commissioner, Citation2013).

As part of the adaptation pathways also more drastic interventions were identified that might be necessary in second half of the century. An example is the option to replace the open storm surge barrier in Rotterdam with a dam with sea sluices.

Delegated decision-making with a strong process czar

Effective policy design also requires coherent decision-making. The Delta Commissioner plays a central role in the decision-making process in the Delta Program. A politically neutral yet seasoned former Permanent Secretary at the Prime Minister’s department was appointed to the position. He is not a direct stakeholder in the process of climate adaptation; his primary tasks are to keep the process going; connect national, regional and local level stakeholders; safeguard the link between the long and the short term; and align water management with spatial planning.

The Consultation Organization of Infrastructure and Environment (OIM) that represents all stakeholder organizations, ranging from recreation and shipping, to agriculture and nature, presents decision proposals for discussion and fine tuning to the National Steering Group. Both the advice of the OIM and the conclusions of the National Steering Group are published online. This transparency builds trust and contributes to the decision-making capacity of the program.

The a priori agreement on the decision-making structure also adds to the decision-making capacity in and around the Delta Program. The Delta decisions constitute the overarching frame. Simultaneously and iteratively with formulating these decisions, regional strategies are developed to ensure alignment between the Delta Decisions and regional and local conditions. The most concrete decisions take place at the level of the Delta plans with the actual measures: dikes to be strengthened, river by-passes to be constructed, measures for improving freshwater availability and so forth. Future adjustments of decisions at these different levels move alongside new research information and new technology that will continuously become available.

Joint fact finding

Another approach applied in the Delta Program to increase decision-making capacity is Joint Fact Finding. Whenever participants in the decision-making process feel that their views are diverging they can be asked to jointly formulate a research question that will deliver more information on the matter. This provides a strong and shared base of information for the discussion, while it also helps to build a mutual understanding and trust necessary to overcome differences and reach an agreement.

A key ambition of the Delta Program was to come up with integrated solutions. This ambition implies that regional and local stakeholders commit themselves to adjust (in location, design or timing) measures originally primarily focusing on flood-safety, freshwater supply and spatial adaptation, so that they also contribute to nature, recreation, quality of the rural or urban landscape, or to the overall regional economy. This commitment contributes to the decision-making capacity in the Delta Program.

Formal policy evaluation in 2016

In the summer of 2016, an independent evaluation commission (Bureau for the Senior Civil Service (ABD), Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Citation2016) concluded that the Delta Act, the Delta Program and the Delta Commissioner were functioning well and were working toward their ambitions. The Delta Act provides a solid legislative infrastructure. The short-term measures have been decided on, and there is build-in adaptation space for adjustment on the way to 2050 and 2100. The Delta Program combines a given structure for policy design with an adaptive approach to design and re-design. Every year, by a check it is assessed whether the strategies and plans are still on track, and every six years a more fundamental review of the Delta decisions, preferred regional strategies and Delta plans is carried out. These are all build-in defaults; while they do not guarantee adaptivity, they do enhance the likelihood of policy change in accordance with emerging developments and policy feedback.

However, the evaluation also raised concerns; the urgency about climate adaptation was fading away (exactly as initially expected); a feeling of comfort and control had nested in the different agencies, with internal debates about making available scarce resources for water works that ‘solve’ problems that may never happen. The evaluation Commission sends out a clear message to all stakeholders; a long-term issue requires a long-term commitment and a sustained level of attention rather than a periodic peak and subsequent drop in attention and action.

Discussion: lessons for policy capacity building

Here, we reflect on the process of the policy design in the case, using our conceptual framework to explain what our case findings mean for the theory and practice of policy capacity and policy design.

Analytical ⇔ operational capacity

The Delta Program organized its adaptive capacity in several ways. First of all, adaptation pathways (Haasnoot et al., Citation2013) were developed and adopted as the cornerstones for the Delta Decisions and for regional Delta strategies. These pathways are visualizations of how different sequences of measures match with different future conditions. Agreeing ‘up-front’ on the set of preferable pathways provides a strong foundation for future adjustments of plans and contributes to the adaptive capacity of the ‘Delta Community’ as a whole. The pathways provided a long-term road-map for adaptation; they became the starting-point for planning.

The same goes for the analytical concept of multilevel safety (MLS). Flood safety is managed on different levels. The first is that of building and raising levees to hold the water back. However, the Delta Program wanted to raise attention for the option of improving the capacity to absorb water, for instance by flood-proofing buildings and infrastructure (‘the second level’). Moreover, there is also the option of investing in improving crisis management and evacuation (‘the third level’). These options were always theoretically on the table, but the Delta Program made them the framework for policy-making and for policy discussions. The Program consistently works from the idea that strategies should not simply focus on level 1, but dramatically enhance the capacity for level 2; moving along with the water, to relieve the pressure on level 1 capacity to hold the water back. Moreover, investment in level 3 is also part of the policy package. That is of huge symbolic importance; because it institutionalizes the option that flooding can happen. For some areas, raising levees is a good option; for other areas it is better to increase the ability to ‘absorb’ water, while for other areas periodic evacuation is probably the best option.

Lesson 1: adaptiveness requires information confirming that policy change is imminent

Therefore, a monitoring system was developed to actively look at long-term developments and emerging issues (Delta Program commissioner, Citation2016). The system detects weak signals and marks signposts for possible policy change. The mere fact that the system is in place means that there is information about the dynamics in the system is being produced and that the policy-design is continuously tested, debated, and if necessary redesigned. The availability of a steady flow of data and information about emerging issues ‘pushes’ the dynamics of the policy process into more attention for adaptation.

Political ⇔ analytical capacity

Lesson 2: feed the political debate and decision-making with evidence

The Delta Program has invested heavily in nesting the political debates and decision-making in ‘joint-fact finding’. In every step of the process the Delta Program has promoted among all government levels involved and all stakeholders to work from scientific evidence.

Lesson 3: political ‘calculation’ that favors ‘toggling’ between cycles

The Delta Program has to discount for interests over a very long time-line; in deciding on investing in new projects costs and benefits for different generations of stakeholders need to be taken into account. The Delta Program has given this an explicit place in the instruments for deciding on projects. That can mean that future projects can be integrated early in present-day investments, or vice versa. For instance, once a city has developed on both sides of the river it has become almost impossible to substantially widen the riverbed in te future. This clears one of the best options for adapting to river flooding; toggling between time-horizons puts this long-term problem of a present-day viable policy option into the discussion. Moreover, it also proposes new solutions and integrates these into the cost-benefit analysis and planning process. For example, in the case of city of Nijmegen, a large-scale river bypass was implemented well before climate change would require it. Doing this now, long before actually needed, turned out to be the most effective way for preventing river-flooding in the future. The new analytical tools made it a viable option, where the ‘normal’ models for planning would not have favored this option.

Lesson 4: long-term options as political anchors

The Delta Program attempts to preserve favorable conditions for interventions that may be needed in the future; it wants to keep possible routes toward possible futures open. As part of the Delta Decisions and regional strategies, it has been decided to keep these long-term options open. Spatial reservations for possible future river bypasses and retention areas are one important consequence of that decision. Without the program these options would not have been a serious and viable option in the debate; because of the instruments for planning were reset in integral terms these options became logical steps in the policy design process.

Operational ⇔ political capacity

Lesson 5: take the debate ‘out of every-day politics’

Adaptation requires a setting that allows agencies and public managers to distance themselves from day-to-day issues. This condition was provided by the institutional recommendations of ‘the founding fathers’ of the Delta Program, the Second Delta Commission. That Commission existed just for a year. However, their fairly radical recommendations were widely embraced and implemented. The advice of the Commission was to move the issue of flood safety beyond the scope of the day-to-day political debate. To do so, the Commission proposed a threefold institutional structure; a Delta Fund with a sizeable annual budget of 1 billion euros, a Delta Commissioner to effectively direct the policy formulation and implantation, and a Delta Act to provide the legal structure for climate adaptation. This structure was deliberately designed to break away from day-to-day politics and pressure on the annual budget in Parliament; at the same time political accountability was organized by an annual report on advancements and plans that is presented to parliament on the annual Day of the Budget.

This laid the basis for effectively dealing with the climate change issue over a long period of time and provided the stability needed to systematically and continuously anticipate possible future and engage in policy discussion with the many levels of government involved. The exact strategies for addressing the challenges related to the changing climate will be adapted and developed further, but the basis for long-term adaptation policy is firmly laid (Van Der Steen et al., Citation2016).

Lesson 6: strengthen the linkages between decentralized and centralized decision-making

The institutional landscape for water policy is highly decentralized and dispersed. Many different stakeholders, with very different interests, are needed to formulate and implement policies. The Delta Commissioner seems to be a central figure that can force agreement, or override regional or sectoral resistance, but that is hardly a practical option; there is simply too much space for actors to move around centralized power or to frustrate policy at length. That is why the Delta Commissioner drew up a timeline of four years to iteratively develop generic national policy frameworks and regional strategies; thus, maximizing the design space of local actors to find agreement on regional strategies. Civil servants from all government levels participated in the regional processes.

Moreover, the Delta Commissioner at times used his personal authority and charisma to push the process in a certain direction and to ‘help’ local actors to overcome barriers. Adding to his potential to resolve barriers in decision-making is the fact that the Delta Commissioner is appointed for seven years; on average two to three times as long as the average national government. The Delta Commissioner is a continuous factor in the decision-making process. This top-down–bottom-up nature of the process also helped in overcoming possible implementation-gaps; regional stakeholders feel ownership over ‘their’ adaptation strategies and are committed to implementing them. The central Delta Commissioner can resort to a role of overseeing and if necessary helping local stakeholders to execute the regional strategy.

visualizes the design choices and their relations with the interplays between the policy competencies

Conclusion

In this article, we have examined the formulation and implementation of a policy design that attempts to anticipate uncertain future developments and feedbacks, to answer our central research question:

What are the design characteristics of policy capacity building for anticipating future effectiveness amidst deep uncertainty?

The case of climate adaptation is an extreme case with conditions of deep uncertainty and complexity, a long-time horizon with a long lead-time of interventions, and the problem of discounting effects that are spread-out over a long period. The case illustrates that effective interplay between the three distinguished policy capacities is important, and requires specific design choices, synthesized in . This synthesis provides us with an adapted policy capacity framework that can be used to categorize design choices and analyze the effectiveness of interplays, or the lack thereof.

In the case of the Delta program, we located the largest challenges in the interplay between operational capacity and analytical capacity. This application of the framework helps identify ‘weak links’ and the processes – and subsequently focusing energy for improving them. We also used the case analysis to specify which policy design elements of the respective capacities contribute most to the chance of success. These elements contribute to the theoretical concept of designing policy capacity that anticipates success under conditions of deep uncertainty, policy myopia and complexity.

Operational capacity: A systematic investment in generating and sharing information at all levels. The Delta program and the Delta Commissioner explicitly focus on a long-term problem and look at long-term conditions. The program starts from the initial assumption that it is impossible to ‘know’ the future, but that it is crucial to make ‘informed policy’. That is why the Delta program invests heavily in analysis of the body of climate research, but also invested in collecting a variety of perspectives to look at the issue of climate adaptation. The crucial policy-choice was to not build a program on one plausible future, or to aim for one preferable scenario, but to take into account all plausible scenarios; the Program has designed policy pathways that are fit for a variety of scenarios and works on establishing triggers and signposts that signal the manifestation of a certain scenario. Moreover, decisions to invest in water works are also made with close attention for the consequences for future developments; do certain investments close-of or enhance future options, can an investment now be of value for a future option and is it possible to link current issues to investments that need to be done in the future anyhow?

Analytical capacity: An integration of adaptivity in operational structures for policy: eg ‘Adaptive Delta Management’, ‘adaptive by design’ and ‘adaptation pathways’; The Delta program and the institutional composition of its stakeholders and operating procedures are ‘adaptive by design’. The assumption behind the program is that circumstances will change and that everything that is built now will have to be fit for use under different conditions. That is an issue in the design of structures – such as waterways or waterworks – but also in the institutional design of the Program. Embedded is a collective agreement on (and concrete procedures for) what needs to happen if external changes necessitate a change of direction, and when stakeholders agree to disagree, a unique feature of the Delta Program design. The Program is ‘built-to-last’, but by the means of the possibility of continuous adaptation.

Political capacity: Alignment of analytical, operational, and political capacity; decentralized and centralized decision-making dynamics: The Delta program is mindful of common tensions and disparities between various levels and actors in multi-level governance settings (cf. Hooghe and Marks, Citation2003). It is a national program, uniting all levels of government and closely cooperating with knowledge institutes, NGOs and the private sector. The program is managed by the Delta Commissioner, which might give the impression of a centralized, top-down led program. However, most of the work needs to be done by decentralized governments with and in local and regional networks of stakeholders. The Delta Commissioner has little formal power and is reliant on local partners – but is very influential. The Delta Commissioner has developed a governance-style that takes local dynamics into account and produces ‘firm’ decisions that are carried by regional networks, and for which local stakeholders feel ownership.

Clearly, our contours of successful policy design require additional comparative research, including more cases and policy domains. In our article, we presented a single case study from the Netherlands, with very limited generalizability. However, our basic analysis produces intriguing questions for comparative case study research into key commonalities between how countries organize their capacity and design, and how they either succeed or fail in doing so.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pieter Bloemen

Pieter Bloemen is Advisor Strategy and Knowledge at the Staff Delta Programma Commissioner, in The Hague, The Netherlands.

Martijn Van Der Steen

Martijn van der Steen PhD is Professor at the Erasmus School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Zeger Van Der Wal

Zeger van der Wal PhD is Associate Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore National University, Singapore.

Notes

1 The other three were: living conditions (heat stress and cloudbursts), biodiversity (shifts in ecosystems, salinization) and economy (vulnerability of vital infrastructure; transport, energy, communication).

2 Ruimtelijke Investeringsagenda (RIA).

3 Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management (Citation2007). Regulation Commission Sustainable Coastal Development. 7 September 2007.

References

- Beh, E.H.Y., Maier, H.R., & Dandy, G.C. (2015). Adaptive, multiobjective optimal sequencing approach for urban water supply augmentation under deep uncertainty. Water Resources Research, 51(3), 1529-1551.

- Biesbroek, G. R., Swart, R. J., Carter, T. R., Cowan, C., Henrichs, T., Mela, H., & Rey, D. (2010). Europe adapts to climate change: Comparing national adaptation strategies. Global Environmental Change, 20(3), 440–450.

- Bloemen, et al. (in press). DMDU into practice: Adaptive Delta Management in The Netherlands. In: Marchau, V., W. Walker, P. Bloemen & S. Popper (eds.) (in press), Decision making under deep uncertainty – from theory to practice.

- Bloemen, P., Reeder, T., Zevenbergen, C., Rijke, J., & Kingsborough, A. (2017). Lessons learned from applying adaptation pathways in flood risk management and challenges for the further development of this approach. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. doi:10.1007/s11027-017-9773-9

- Boezeman, D., Vink, M., & Leroy, P. (2013). The Dutch delta commission as a boundary organisation. Environmental Science & Policy, 27, 162–171.

- Botzen, W. J., & Van den Bergh, J. (2008). Insurance against climate change and flooding in the Netherlands: Present, future, and comparison with other countries. Risk Analysis, 28(2), 413–426.

- Bureau for the Senior Civil Service (ABD), Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. (2016). Statutory ex-post evaluation of the Delta Act. The Netherlands: Ministry of the Interior.

- Buurman, J., & Babovic, V. (2016). Adaptation pathways and real options analysis: An approach to deep uncertainty in climate change adaptation policies. Policy and Society, 35(2), 137–150.

- Cabinet Balkenende, I. V. (2007). Water vision: Conquering the Netherlands for the future. Cabinet vision on water policy. The Netherlands: Ministry of General Affairs.

- Capano, G, & Woo, J. J. (2017). Resilience and robustness in policy design: a critical appraisal. Policy Sciences, 50(3), 399–426. doi:10.1007/s11077-016-9273-x

- Delta Commission. (2008a). Discussion report on decision-making Delta Commission: Political-administrative implications. The Netherlands: Delta Commission.

- Delta Commission. (2008b). First concept of chapter 5: “Decision-making: From vision to implementation. The Netherlands: Delta Commission.

- Delta Commission. (2008c). Report of a visit to States Flevoland. The Netherlands: Delta Commission.

- Delta Commission. (2008d). Working together with water. A living land builds for its future. Findings of the Delta Commissie. The Netherlands: Delta Commissie. Retrieved from http://www.deltacommissie.com/doc/deltareport_full.Pdf

- Delta Programme Commissioner. (2013). The 2014 Delta Programme Working on the delta. Promising solutions for tasking and ambitions (English version). The Netherlands: Ministry of Transport Public Works and Water Management and Ministry of Agriculture Nature and Food Quality, Ministry of Housing Spatial Planning and the Environment.

- Delta Commissioner. (2014). The 2015 Delta Programme Working on the Delta. The decisions to keep the Netherlands safe and liveable (English version). The Netherlands: Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment and the Ministry of Economic Affairs.

- Delta Programme Commissioner. (2016). The 2017 Delta Programme working on the delta: linking taskings, on track together. The Netherlands: Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment, Ministry of Economic Affairs, Dutch national government.

- Dessai, S., & Van der Sluijs, J.P. (2007). Uncertainty and climate change adaptation: a scoping study. Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development and Innovation, Department of Science Technology and Society.

- Groves, D. G., Bloom, E. W., Lempert, R. J., Fischbach, J. R., Nevills, J., & Goshi, B. (2014). Developing Key Indicators for Adaptive Water Planning. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management, 141(7). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000471, 05014008.

- Haasnoot, M., Kwakkel, J. H., Walker, W. E., & Ter Maat, J. (2013). Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: A method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world. Global Environmental Change, 23, 485–498.

- Haasnoot, M., Middelkoop, H., Offermans, A., Beek, E. V., & Deursen, W. P. A. V. (2012). Exploring pathways for sustainable water management in river deltas in a changing environment. Climatic Change, 115, 795–819.

- Haasnoot, M., van Deursen, W. P. A., Guillaume, J. H. A., Kwakkel, J. H., van Beek, E., & Middelkoop, H. (2014). Fit for purpose? Building and evaluating a fast, integrated model for exploring water policy pathways. Environmental Modelling & Software, 60, 99-120. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2014.05.020

- Hamarat, C., Kwakkel, J. H., Pruyt, E., & Loonen, E. (2014). An exploratory approach for adaptive policymaking by using multi-objective robust optimization. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory, 46, 25-39. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2014.02.008

- Hart, H. (1994). The concept of law (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Head, B., & Alford, J. (2015). Wicked problems: Implications for public policy and management. Administration & Society, 47(6), 711–739.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2003). Unraveling the Central State, but how? Types of Multi-level Governance. In: American Review Political Science, Vol. 97, No. 2, pp.233-243.

- Howlett, M., & Mukherjee, I. (2014). Policy design and non-design: Towards a spectrum of policy formulation types. Politics and Governance, 2(2), 57–71.

- Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2014). The two orders of governance failure: Design mismatches and policy capacity issues in modern governance. Policy and Society, 33(4), 317–327.

- Hulme, M. (2009). Why we disagree about climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jeuken, A., & Reeder, T. (2011). Short-term decision making and long-term strategies: how to adapt to uncertain climate change. Examples from The Thames Estuary and The Dutch Rhine-meuse Delta. Water Governance, 1, 29-35.

- Jordan, A., Huitema, D., Asselt, H. V., Rayner, T., & Berkhout, F. (2010). Climate change policy in the European Union: Confronting the dilemmas of mitigation and adaptation. Cambridge: University Press.

- Koningsveld, M. V., Mulder, J. P., Stive, M. J., Van der Valk, L., & Van der Weck, A. (2008). Living with sea-level rise and climate change: A case study of the Netherlands. Journal of Coastal Research, Volume 24, Issue 2: pp. 367 – 379.

- Lindblom, Ch.E. (1979). The science of muddling-through. In: Public Administration Review, 19, spring, 1959, pp.77-88.

- Lempert, R. J., & Groves, D. G. (2010). Identifying and evaluating robust adaptive policy responses to climate change for water management agencies in the american west. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77, 960-974. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2010.04.007

- Maier, H. R., Guillaume, J. H. A., Delden, H. V., Riddell, G. A., Haasnoot, M., & Kwakkel, J. H. (July 2016). An uncertain future, deep uncertainty, scenarios, robustness and adaptation: How do they fit together? Environmental Modelling & Software, 81, 154–164. ISSN 1364-8152.

- March, J.G., & Olsen, J.P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions: the organizational basis of politics, New York: Free Press.

- McCray, L., Oye, K. A., & Petersen, A. C. (2010). Planned adaptation in risk regulation: An initial survey of U.S. environmental, health, and safety regulation. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 77(6), 951–959.

- Mees, H. L., Driessen, P. P., & Runhaar, H. A. (2012). Exploring the scope of public and private responsibilities for climate adaptation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 14(3), 305–330.

- Ministry of General Affairs. (2009). Working on the future, an additional policy agreement for ‘Working together, living together’. The Netherlands: Ministry of General Affairs.

- Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management. (2007). Water Visie. Nederland veroveren op de toekomst. Kabinetsvisie op het waterbeleid. The Netherlands: Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management.

- Nair, S, & Howlett, M. (2017). Policy myopia as a source of policy failure: adaptation and policy learning under deep uncertainty. Policy & Politics, 45(1), 103–18. doi:10.1332/030557316X14788776017743

- Peters, B. G. (2017). What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program. Policy and Society, 36(3), 385–396.

- Petersen, A., & Bloemen, P. (2014). Planned adaptation in design and testing of critical infrastructure: The case of flood safety in the Netherlands. In: Proceedings International Symposium for Next Generation Infrastructure, Laxenburg: ISNGI.

- Poli, R. (2017). Introduction to anticipation studies. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Schultz Van Haegen, M., & Wieriks, K. (2015). The Deltaplan revisited: Changing perspectives in the Netherlands’ flood risk reduction philosophy. Water Policy, 17, 41–57.

- Simon, H. A. (1997 [1945]). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organizations. New York: The Free Press.

- Slob, M., & Bloemen, P. (2014). Core values of the Delta Programme, Solidarity, Flexibility, Sustainability – a reflection. The Netherlands: Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment and Ministry of Economic Affairs.

- Sowell, J. (in press). A Conceptual Model of Planned Adaptation. In Vincent Marchau, Warren Walker, Pieter Bloemen, and Steven Popper (Eds.), Decision making under deep uncertainty – from theory to practice.

- Swanson, D., & Bhadwal, S. (eds.). (2009). Creating adaptive policies: A guide for policy-making in an uncertain world. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Teisman, G., Van Buuren, A., & Gerrits, L. (Eds.). (2009). Managing complex governance systems (pp. 87–104). London: Routledge.

- Twist, M. V., Schulz, M., Van der Steen, M., & Ferket, J. (2013). De Deltacommissaris. Een kroniek van de instelling van een regeringscommissaris voor de Nederlandse delta. The Hague: NSOB. ISBN 978-90-75297-33-I.

- Van Alphen, J. (2016). The Delta Programme and updated flood risk management policies in the Netherlands. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 9, 310–319.

- Van Buuren, A., Driessen, P. J., Van Rijswick, M., Rietveld, P., Salet, W., Spit, T., & Teisman, G. (2013). Towards adaptive spatial planning for climate change: Balancing between robustness and flexibility. Journal for European Environmental and Planning Law, 10(1), 29–53.

- Van der Steen, M., Vink, M., Chin-A-Fat, N., & Van Twist, M. (2016, February). Puzzling, powering and perpetuating: Long-term decision-making by the Dutch delta committee. Futures, 76, 7–17.

- Van der Wal, Z. (2017). The 21st century public manager. London: Macmillan.

- Vellinga, P., Katsman, C., Sterl, A., & Beersma, J. (2008). Exploring high-end climate change scenarios for flood protection of the Netherlands. KNMI scientific report; WR 2009–05. Joint publication by Wageningen University and Research Centre and the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI).

- Vink, M., Benson, D., Boezeman, D., Cook, H., Dewulf, A., & Termeer, C. (2014). Do state traditions matter? Comparing deliberative governance initiatives for climate change adaptation in Dutch corporatism and British pluralism. Journal of Water and Climate Change 1 March 2015; 6 (1): 71–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2014.119.

- Vink, M. J., Boezeman, D., Dewulf, A., & Termeer, C. J. A. M. (2013a). Changing climate, changing frames: Dutch water policy frame developments in the context of a rise and fall of attention to climate change. Environmental Science and Policy, 30, 90–101.

- Vink, M. J., Dewulf, A., & Termeer, C. (2013b). The role of knowledge and power in climate change adaptation governance; a systematic literature review. Ecology and Society, 18, 4.

- Walker, W., Marchau, V., & Swanson, D. (2010). Addressing deep uncertainty using adaptive policies: Introduction to section 2. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77, 917–923.

- Walker, W. E., Haasnoot, M., & Kwakkel, J. H. (2013). Review: adapt or perish: A review of planning approaches for adaptation under deep uncertainty. Sustainability, 5, 955–979.

- Warner, J. (2008). The politics of flood insecurity. Framing contested river management projects ( PhD Doctoral thesis). Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Weick, K. E. (2000). Making sense of the organization. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wu, X., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (2015). Policy capacity: a conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy and Society, 34(3–4), 165-171. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001