ABSTRACT

Robust policy design is an activity that is ‘done’ by policymakers; in this paper we look further into how exactly robust policy design is done. We use the literature on strategizing to distinguish various theoretical perspectives on how policy design is done in practice. Moreover, we conducted a survey-feedback study with a group of senior level policymakers to see what they do when ‘doing’ robust policy design, how they think it should be done, and what they think are challenges for doing robust policy design in the context of a public organization. The study shows that although the language of strategy and policy design is rooted in the rational-analytical ‘planning’ approach, other perspectives are in fact more suitable for designing robust policies for deeply uncertain and volatile conditions. Moreover, our study shows that practitioners are well-aware of this bias; they have developed practical ways to combine the rational-analytical approach to design that is expected from them with other approaches for doing design.

Introduction

There is a renewed interest in strategic thinking in the field of public policy. The combination of high levels of uncertainty (Walker, Marchau, & Swanson, Citation2010; Citation2013) high levels of complexity (Cavano & Mares, Citation2004; Morçöl, Citation2012; Teisman, Van Buuren, & Gerrits, Citation2009), and the increased ‘wickedness’ of issues (Head & Alford, Citation2013; Peters, Citation2017) proposes strong challenges for policymakers who wish to design robust policies (Howlett, Capano, & Ramesh, Citation2018; Capano & Woo, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Howlett & Mukherjee, Citation2014). There are many possible definitions of robustness, but here we follow the definition used in this Special Issue, by Capano and Woo (Citation2018a); a policy is robust when it can maintain performance under a high degree of turbulence that cannot be projected beforehand (Howlett. Capano & Ramesh, Citation2018). Robust policy is policy that is fit for a yet unknown purpose, able to deliver outcomes in spite of a changing environment and changing conditions.

Policy design is (Howlett et al., Citation2018, p. 19)

a specific form of policy formulation based on the gathering of knowledge about the effects of policy tool use on targets and the application of that knowledge the development and implementation of policies aimed at the attainment specifically desired public policy outcomes and ambitions.

Policy design is a deliberate and conscious attempt to achieve a certain goal, in contrast with opportunistic, symbolic or intuitive ways of to apply instruments to public goals. These definitions indicate a set of criteria for calling policy formulation a design and for calling a design robust; robustness is the ability to remain effective under uncertainty and unknown future dynamics, and design is the deliberate use of knowledge and information to match instruments with public goals.

These definitions mark what robust policy design is, but they do not explicate how robust policy design is done. Although design is defined as a verb, the type of activity or process it involves is left open. That is why in this paper we are interested in how robust policy design is done? What are possible approaches, or routes, to do it? And how are these perceived by policymakers? Therefore, the research question that guides our paper is as follows; what are theoretical approaches for doing robust policy design and how do these approaches relate to the practice of policymakers?

To answer the first part of the research question we will use literature from the field of strategy and ‘strategizing’ to distinguish the variety in approaches or routes to do robust policy design. The strategy literature has a long tradition of debate about the question what strategizing is and how it should be done (Jarzabkowski, Citation2005; Johnson, Langley, Melin, & Whittington, Citation2007; Mintzberg, Citation1987; Whittington, Citation1996). From the strategy-literature we distinguish five perspectives to think about doing strategy; we discuss the specific properties of each perspective and identify how each perspective deals with uncertainty and volatility, and how robustness is achieved. After that, we answer the second part of our research question with findings from a survey-feedback-study that we conducted with policymakers. We asked policymakers how they perceived the normative quality and the practical relevance of the various routes for robust policy design. Their answers show how they see the applicability of different approaches in practice, and also present new insight in some of the dilemmas of robust policy design. After this, we use the empirical findings from the Delphi Study to reflect on the possible routes for the design of robust policy.

Theoretical framework

Strategy is often defined, sometimes in slightly different phrasing, as a plan of action designed to achieve an overall aim (Stewart, Citation2004; Whittington, Citation1993); or, as Lusk and Birks (Citation2014) define it, as a choice of options to achieve strategic intent. These definitions of strategy are quite similar to the definition of policy design (Howlett et al., Citation2018; Howlett & Mukherjee, Citation2014); both refer to the ability to deliberately connect tools and instruments to stated policy goals, and to do that in a thought-through manner. That is why in the light of our research question it is interesting to see how the strategy-literature conceptualizes ‘strategizing’, in order to distinguish different theoretical approaches for ‘doing robust policy design’.

The strategy-literature contains a wide variety of perspectives of what good strategy is and what strategy-practitioners, or strategists, do when they engage in strategy (Jarzabkowski, Citation2005; Llewellyn & Tappin, Citation2003; Lusk & Birks, Citation2014; Mintzberg, Citation1994, Citation1987; Noordegraaf, van der Steen, & van Twist, Citation2014; Whittington, Citation1993). There are many ways for ordering the different approaches for doing strategy. Mintzberg (Citation1987) alone has presented many different orderings, varying from 5 to 10, to as much as 32 different perspectives. More importantly, Mintzberg nuances the relevance of any specific ordering; what matters is the use of a (or any) variety of perspectives to see depth and escape the narrow focus of ‘strategy as a plan’ that dominates the field (Mintzberg, Citation1987).

In this paper we distinguish between five different perspectives on doing strategy that we have used often in executive education for senior-level policymakers and public managers. We based the distinction on two different bodies of work. First, we used Mintzberg’s (Citation1994) distinction between five ‘schools’ for thinking about strategy; strategy as a plan; as a position; as a ploy; as a perspective; as a pattern. Second, to better suit the context of public policy we adapted these schools along the lines of five theoretical perspectives presented by de Caluwé and Vermaak (Citation2003) to order approaches to change management; they distinguish between change management as a blueprint-approach, a human relations approach, a power relations approach, a sensemaking approach, and as an emergence approach. We combined these into five perspectives to view strategy that can bring variety in the conversation about strategizing, or in this case about the design of deliberate policy for complex issues; strategy as rational planning; strategy as visionary leadership; strategy as a political power game; strategy as collective sensemaking; strategy as capacity building. We will introduce each perspective here.

In the remainder of this paper we will toggle between discussing the perspectives as ‘strategy-perspectives’ and ‘design-perspectives’. We introduce each perspective in the language of strategizing, after which we shift to the language of policy design. So, instead of a sequential approach where we first present all of the perspectives in ‘strategy-language’ and then translating them into design-language, for reasons of readability and clarity we choose to combine these in the discussion of each perspective.

Moreover, it is important to clarify the choice we made in the distinction between ‘vision’ and ‘strategy’. In the definition of strategy and design we use in this paper, setting the goal, the strategic intent, or defining the policy-issue are not part of the strategy-process or the design-process; strategy is seen here as the process to find and choose solutions for a given issue. This is congruent with most of the strategy literature (Lusk & Birks, Citation2014), but there are also conceptualizations that see the definition of strategic intent as part of the strategy process. In this paper we refer to vision as setting the goal and formulating strategic intent, and strategy as developing the path towards achieving that goal. However, as we will see, in order to design for robustness reflection on the strategic intent itself is also at times part of the strategy-process, and it is done differently in each perspective.

The rational-expert perspective

This perspective refers to the literature that sees strategizing as a rational-analytical process with a focus on systematical planning and implementation. Mintzberg (Citation1987) refers to this as ‘strategy as plan’, meaning that the course of action is purposely and consciously thought out in advance; strategic behavior is intended (Bailey & Johnson, Citation2001; Drucker, Citation1974; Mintzberg, Citation1987; Steiner, Citation1969). The strategy itself is based on the use of analytical evidence analyses and is supported by specific strategizing techniques such as planning (Andrews, Citation1971; Ansoff, Citation1965; Hamel & Prahalad, Citation1994). The strategy itself is a long-term plan, that is deliberate, carefully articulated, precise and integrated (Glueck, Citation1980; Hedley, Citation1977; Hendry, Citation2000). The execution of this plan is a matter of management that carries out the original plan in detail. Strategy formulation and implementation are separated processes (Jarzabkowski, Citation2005). In this perspective, a successful strategy provides a substantiated analysis and a detailed ‘blue-print’ for the steps that need to be taken in order to tackle the root cause of the problem.

In this perspective, the strategist is an analytical-expert (Miles & Snow, Citation1978). He is a ‘planner’ who makes decisions based on evidence (Hendry, Citation2000; Steiner, Citation1969). He acknowledges the importance of a well-defined plan and implements it meticulously . In each step of the process, evidence, data, knowledge, expertise are imperative; these allow the strategist to determine the best course of action; strategy follows from analysis. Strategists use analytical tools such as SWOT/PESTEL, stakeholder mapping, value chain analyses (Christensen, Andrews, Bower, Hamermesh, & Porter, Citation1982), or the ‘five forces model’ (Porter, Citation1979) for strategic analysis.

There are several strong points to the perspective of strategy as a plan. It brings order to the often-chaotic practices of an organization and its environment. Moreover, a strategic plan is instructive for the organization and can be used to align the organizational capacity and instruct others what to do. There are also weaknesses to this perspective. The crisp analysis of a complex problem requires reduction of the problem and the context. Moreover, this perspective suggests a clear divide between strategy formulation and implementation; the analysis is reserved for the first phase of the process; in the implementation phase there is no room for reflection on the original plan. Furthermore, this perspective focuses mainly on elements of the organization and the environment that can be included in analytical and often quantitative models; anything that cannot be modelled cannot be part of the strategic process, even though it may be relevant.

The perspective of strategy as a plan may be problematic for achieving robustness. Robustness is needed when there is deep uncertainty, complexity is intense, and problems are ‘wicked’. These factors make it difficult to develop a rational analysis that captures all of the complexity and uncertainty. A rational-planning approach can only lead to a robust policy design if it is possible to gather sufficient evidence and data to ‘map’ the whole of the problem and to foresee all of the possible policy-options and outcomes. This is difficult for ‘tamed’ problems in stable systems, and it is almost impossible for wicked issues, in a highly uncertain and volatile environment.

The visionary leadership perspective

In the perspective of visionary leadership, the strategy needed to achieve a goal emerges from the personal ideas of a visionary leader (Ackoff, Citation1993; Bailey & Johnson, Citation2001; Drucker, Citation1970; Jaques & Clement, Citation1991; Mintzberg, Citation1987). Strategy as visionary leadership sees strategy as an almost intuitive; it is as the leader ‘feels it’ should be (Bennis & Nanus, Citation1985). Sketchy as this sounds, there are many examples of visionary leaders, both in the worlds of business and government, who were able to achieve goals that no analytical process would have figured possible. Especially in innovative environments, where there is much uncertainty and ambiguity, visionary leaders can ‘see pathways’ towards a strategic goal that others cannot imagine or do not dare to suggest.

A visionary strategy provides energy and inspiration to those who work to solve a policy problem and creates clarity for them about the long-term direction (Kouzes & Posner, Citation1995; Nanus, Citation1992). These are important elements for design processes that require individuals to cooperate on complex and ambiguous tasks. Visionary leadership can produce the ‘belief’ to keep agents going, provide a shared framework to make sense of ambiguity, and allows people to work together on complex tasks. A shared framework can be extremely helpful to ‘get the design done’, even if it is not necessarily ‘right’.

Seen from this perspective, strategizing involves a leader who proposes an idea or concept about the path to go, which appeals to the people who have to work with it. This draws them into a joint process of ‘working out the details’ and work into the same direction, further down the path presented by the leader. The ‘vision’ at the start of a strategy-process acts as a guiding framework for action and interpretation, and lays out the lines for agents to work on further details of the plans (Kouzes & Posner, Citation1995; Nanus, Citation1992).

Visionary leadership does not come from the use of analytical tools, but tools can help the leader to share the visionary story. They organize retreats, meetings, create ‘visuals’, brands, and hold ‘Ted-talks’ to communicate their beliefs and set out the path for the others to follow. Consider this example; a permanent-secretary visited elderly care homes to see the ‘problem’ of the sector first-hand; during one of the visits he was really touched by an elderly man who tells them he has worked in a factory all his life, only to find himself spending the last years of his life in a ‘care-factory’. This then became the basis for a program to radically reform elderly care, called ‘Dignity and Pride’. The story of the old man in the factory became the tool to communicate the vision and to lay-out the problem and the direction in which to go and look for a solution. This energized policy-makers in the organization with a new narrative to guide their design of policy for elderly care. Whenever new unexpected challenges emerged ‘Dignity and Pride’ provided them with a guiding framework to interpret the new dynamics.

Strong points in this perspective are the attention for the personal side of strategy; the visionary leader provides a face to the strategy. Moreover, strategy is not an abstract product, but something to believe in and ‘go for’; it generates energy and passion. The weaknesses of this perspective are related to the personal heroism it holds; it can even invoke a ‘personal cult’, invoke groupthink, and there is an obvious risk that the leader is wrong.

The perspective of strategy as visionary leadership suits the notion of robustness quite well, in the sense that the visionary story provides direction to the design efforts. Moreover, given that the visionary image is unspecified, there is much room for maneuvering along the way; the path remains open for interpretation as long as it does not challenge the core assumptions. The latter may be problematic for robustness; perhaps ‘Dignity and Pride’ is not such a productive principle for the health care sector after all. Who then is able to critically reflect on it? The most important weakness is the dominant position of the leader; there are many cases of group-think and strategy lock-in, where the visionary path blocks the ability to see what is emerging and react to it.

The sensemaking perspective

The sensemaking perspective sees strategizing primarily as a process to create shared meaning in an organization (Bailey & Johnson, Citation2001; Chia, Citation2004; Jarzabkowski, Citation2005; Mintzberg, Citation1987; Pye, Citation1995). Like in visionary leadership, shared meaning provides a basis for joint action. However, unlike visionary leadership, shared meaning here is produced in interaction between agents, in joint processes of sensemaking (March & Olsen, Citation1989; Weick, Citation2001); sharing stories, models, ‘maps’, pictures, and symbols helps to create a shared meaning between different actors in the organization, so that they can work efficiently and effectively on the complex task of finding a path towards a solution for a policy problem (Deal & Kennedy, Citation1982; Weick, Citation2001).

‘Strategic stories’ help policymakers engaged in policy design to make sense of the complexities in the environment and provides them with a guide for action (Weick, Citation2001). Strategizing helps the organization and its members to make sense of the complexity and ambiguity they encounter. A sensemaking perspective to strategizing draws attention to the importance of developing a joint causal story that helps to deal with complexity.

To develop this capacity, a strategic process needs to support interaction and learning (de Caluwé & Vermaak, Citation2003). The process empowers individual actors to come up with ideas, even if their formal status in the organization would suggest otherwise. The process of dialogue is more important than any specific document that comes out of that process. The document is only important as a symbol that invokes shared sense that was made in the process. The real product is the shared meaning participators hold, which they ‘enact’ (Weick, Citation2001) when they work on the policy issue.

Tools are used to facilitate interaction and the learning process. Seen from this perspective, a SWOT-analysis is not an analytical tool, but rather a platform to engage in a conversation. While agents formulate ideas about strengths and weaknesses, they are finding shared meaning. From this perspective, that is the real outcome. Therefore, a design-process is to be designed as an interaction-process, in which agents can together ‘find’ and ‘co-create’ the strategy they are looking for.

A strong point of the sensemaking perspective is the attention for underlying values in the organization. It helps to understand the social fabric of the groups that are doing the design. Moreover, shared meaning can enhance the organizations’ ability to deal with unexpected events and be adaptive in the face of uncertainty (Välikangas, Citation2010).

A risk of this approach is that collective sensemaking is reliant on the participants and their group-dynamics. Dominant group members can block the dialogue in the group, and the lack of outsiders in the group can create a tunnel-vision. Mundane problems also play a role; groups can be tired, grow weary, or become dominated by loud voices. Some also argue that this process is ‘slow’; finding common ground can be a cumbersome and lengthy process; it may take many meetings to develop a joint understanding of the problem.

The approach of strategy as collective sensemaking could suit the concept of robustness well. As long as the sensemaking process remains open and outward looking it can be a powerful basis for continuous adaptation and redesign of policy, along with emerging developments and new insights. Sensemaking also suits the conditions for robust policy design well; deep uncertainty and unknown dynamics are ambiguous and require active sensemaking by agents. Agents will be likely to carry that mindset on into the further process. Moreover, a sensemaking process also familiarizes agents with the ‘normalcy’ of uncertainty; the process nurtures the idea that conditions are ambiguous, unpredictable, complex, and that agents should continuously reflect on what is happening around them.

The political power game perspective

The political nature of organizations is the focal assumption in the power game perspective to strategizing (Allison, Citation1971; Bailey & Johnson, Citation2001; Pettigrew, Citation1973). Here, politics is not ‘party politics’ but organization politics; the inevitable ‘political fight’ of members of the organization over scarce resources, dominance, and influence in the organization that is designing policy. Every policy design has consequences for the distribution of power and resources; this perspective puts this political struggle at the forefront of the analysis and practice of ‘doing’ strategy, and of doing policy design (Lusk & Birks, Citation2014; Mintzberg, Citation1994).

A design distributes scarce resources; actors recognize their interests in the distribution and mobilize the leverage they have to influence the outcomes of the process. External stakeholders attempt to bend the design to their favor and start lobbying (Bolman & Deal, Citation1997; Pettigrew, Citation1973). Seen from this perspective, drawing up a strategy is a set of power games, in which actors attempt to forge a strong enough coalition of support (Narayanan & Fahey, Citation1982; Schwenck, Citation1989). Strategic decisions become possible when a temporary coalition of key players is able to translate its shared interests into a strategic ‘object’; e.g. a decision, action-plan, or policy proposal. Strategizing takes place in activities such as negotiation, bargaining and coalition formation; these are not alien to strategy, and are not ‘foul play’, but are a normal part of any strategy-process (Mintzberg, Citation1994).

An important strength of this perspective is that it pays attention to the often-concealed dimension of organizational politics. Looking at coalitions, power games, and vested interests help to understand obstruction and resistance in organizations. Moreover, it also explains why some strategies ‘work’; ideas make it into a design not because the concept is analytically flawless, but because it mobilizes enough support to reach a temporary agreement over what to do. From this perspective, that is not a sub-optimal outcome, but a success; strategy-formulation always requires compromise, political pragmatism is a normal part of any design process.

The weakness of this perspective is that it can easily turn into a cynical approach; it reduces a design process to getting enough stakeholders on board, no matter what the content is they agree upon. Moreover, ‘politicizing’ a strategy process can also block creative processes that were also taking place. It can easily escalate into a political battle-ground, as others develop counter-strategies, by coalitions of other interest groups that seek to promote a design that is favorable to them.

The perspective of strategy as political coalition building is somewhat problematic in relation to robustness. This perspective focuses on balancing different stakes in the organization. It will be difficult to translate rapidly changing external conditions into new power coalitions. Coalitions will be likely to confirm the status quo. Moreover, political consensus takes a significant amount of time and commitment from stakeholders to create; that is why stakeholders will want to hold on to it for a longer time. This will make it harder to change the design along the way. Designs are ‘easy to change’ of there are obvious gains for powerful dominant agents in the coalition, but otherwise it is almost impossible to change a design along the way.

The capacity-building perspective

A fifth perspective sees strategy is deliberately emergent; a deliberate effort to adapt in a yet unknown manner to unknown changes when they emerge. Already in his early work Mintzberg (Citation1987) coined the distinction between intended and emergent strategy. It is often understood as a difference between strategy as intended beforehand and how strategy plays out in practice. The perspective of strategy as capacity building sees emergence as an inevitable and therefore inherent element of any strategy, or design. From the perspective of capacity-building emergence is the starting-point for strategizing; a strategy positions the organization or the system to maximize its benefit from inevitable emergence (Sutcliffe & Vogus, Citation2003; Teisman et al., Citation2009).

The perspective of capacity building sets aside the notion of design as ‘setting out a path’, but sees it as a deliberate positioning for finding the path along the way; a designated capacity to help the organization deal with emergent development and respond effectively to how complexity unfolds in real time; a structural capacity to deal with the unexpected. This approach seeks to maximize the responsiveness to emerging developments; not as a means of improvisation because of surprise, but intended, deliberately planned and organized for; the organization is designed to manage the unexpected (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2001; Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeldt, Citation2002).

From this perspective strategy is intended to improve the capacity of the organization to respond to what happens in real time, not to plan ahead (Aldrich, Citation1979; Bailey & Johnson, Citation2001). Changes in the environment push the organization to turn real time developments into opportunities (Swanson & Bhadwal, Citation2009; Välikangas, Citation2010; Walker et al., Citation2010). The key capacity of a design is it’s the responsiveness to deal with a dynamic environment (Boin & van Eeten, Citation2013; Hamel & Välikangas, Citation2003). This implies that strategy is not a project but rather an ongoing process (Välikangas, Citation2010); a continuous process of adapting, learning, growing, and transforming in response to real time developments in and around the organization (Weick, Citation2001).

The attention paid to emergence and ‘surprise’, as well as to concepts of redundancy and experimentation, are strong points of this perspective. It warns against too much planned strategy that pretends the world to be known and blinds agents to see divergent emerging developments as they happen. However, this perspective does not take into full account the virtues of anticipation and emphasizes the environment as the critical factor for success; an often-heard critique is that if strategy is merely responsive the policy may be going anywhere the environment takes it. Moreover, adaptivity also bares costs; an adaptive system cannot easily develop economies of scale, nor reap the benefits of routines and repeated practices.

The perspective of strategy as capacity building seems well suited for robustness; the core of this perspective is that the environment is uncertain and volatile and that design involves a continuous reflection on what is happening outside. Instead of ‘planning ahead’, policy is systematically positioned to deliberately change along the way. This is still ‘robust’ in the sense that the original goal is not put into question; there is still strategic intend, but it is achieved by steps that are formulated along the way. The policy-goal remains the focal point and is used as a compass for decisions and adaptations along the way.

Five perspectives for ‘doing design’

The different perspectives focus on different aspects of strategy or design; the perspectives can be used as lenses to observe a strategy practice or a policy design process. Each perspective opens up a range of choices for policymakers who are ‘doing’ policy design; instead of the frame of design as ‘rational planning’ there are five possible routes to arrive at a robust policy design. This answers the first part of our research question; we distinguish between five different theoretical approaches for doing policy design; even though we concede, along with Mintzberg (Citation1987), that other distinctions are possible as well; the point is that there is a variety of theoretical perspectives, much broader than the singular perspective of design as a rational-analytical ‘strategic planning’ approach. Each perspective holds merit and has its own norms for good or bad quality design. This broadens the notion of doing policy design and opens up more ways for the design of robust policy. The question how to arrive at a robust policy design can be answered along the lines of five different perspectives. summarizes the key characteristics of each approach.

Table 1.: Key characteristics of the different strategy perspectives.

Research design and methods

In order to answer the second part of our research question, ‘how do the various theoretical approaches relate to the work practice of policy designers’, we were interested in knowing more about how policymakers think about the different routes to make robust policy. More specifically, we were interested in two things; how they were at that time doing this in their own work-practice; and how they think it should be done.

Knowing the difference between how it is (Ist) and how they think it should be (Soll) is interesting for two reasons. First, we want to see if there is a gap between ‘ist’ and ‘soll’; and if so, what the most important differences are. Second, we wanted to see which of the approaches policymakers perceive to suit their practice best. This is not to say we can actually see what they ‘really’ do in practice; we are limited to their perceptions of practice, and to what they say they prefer; we see their stated preferences, not the preferred behavior of the participants in our study. That is why we call it a normative preference; we see what practitioners say is important to them.

In order to ‘catch’ the perspectives and perceptions in the mind of policymakers we used a survey-feedback method. Survey-feedback is a qualitative research method that originates from the field of organizational development (Bennebroek Gravenhorst, Citation2007; Björklund, Grahn, Jensen, & Bergström, Citation2007; French & Bell, Citation1999). The method is a combination of a survey and a qualitative discussion among respondents of the survey, who can then reflect on the results of the survey. The method resembles the more traditional Delphi method, but with a much smaller sample size, and with a different balance between the survey and the discussion; the survey sets participants up for a discussion, which is the most important element of the method. The survey produces a basis for discussion that focuses the discussion among the respondents.

The starting point of survey feedback is a survey of which the (quantitative) data are used in a feedback session to generate the qualitative data; the survey-data is not meant to produce a complete picture of the perceptions of respondents, but functions as the context for respondents to engage in a conversation (Björklund et al., Citation2007). Respondents of the survey are asked to discuss and interpret the outcomes of the survey in group-settings, which provides added insight (Boonstra, Citation2004; Kuhnert, Citation1993). lists the most important differences between a traditional survey and the survey feedback method.

Table 2. Differences between classical survey research and survey feedback method.

In our survey feedback study, we took four steps. Firstly, we designed a survey based on the conceptual framework of the five perspectives for the design of robust policy that we took from the literature on strategy and strategizing.

Secondly, we operationalized the four dimensions into survey items. First, we developed five items for each dimension. We tested these in a pilot-survey with a small group of policymakers. They completed the survey and we discussed the personal profiles from the survey with them individually. We used their feedback for finalizing the survey items, which resulted in the definitive survey list (see Appendix 1).

Thirdly, we asked the respondents of the study to complete the survey online. Respondents were all senior level policy-makers assigned to design a policy for a complex policy issue; they keep that task in mind when completing the survey and in the discussion in the feedback session. One part of the respondents were international groups of participants of an executive course that the researchers taught at a recognized executive education institute in Germany; another part of the respondents were participants to an executive course taught in a prominent executive education institute in The Netherlands. All respondents followed a course on ‘strategic policy and governance’ and came to the course with the question how to more ‘strategically’ design policies to deliver results under complex conditions, in a volatile environment; participants were asked to complete the survey with that policy issue and task (deliver results under complex conditions and a volatile environment) in mind. For example, one of the participants was responsible for designing policy for the ‘integration’ of immigrants during the refuge-crisis in 2016. For the respondents it came naturally that they were not designing a quick fix, but were looking for a long-term solution for a highly uncertain and volatile issue; in that sense, each participant completed the survey with a process of robust policy-design in mind.

In the survey respondents rank individual statements from most agree to most disagree. They are asked to rank statements first on how they think strategy currently is (the ‘Ist’ situation) and then how strategy should be (the ‘Soll’ situation). For both the ist-situation and the soll-situation respondents rank items on a scale from 1 to 5, and each value can be given only once. Our sample consisted of 99 participants.Footnote1 All respondents were senior level policymakers in the public sector. Seventy-nine of them were from the Netherlands, 20 were from other countries, such as Germany, France, Belgium, Italy, Austria, Romania and Switzerland.

Fourthly, we organized feedback sessions in which respondents could discuss their data. The session allowed respondents to reflect on their choices and elaborate on the arguments they had for their choices. Respondents from the Netherlands had sessions in The Hague, international respondents discussed the survey in Berlin. In these sessions outcomes of the survey were used to start a discussion; each respondent was first presented with a personal ‘Ist’ and ‘Soll’ profile on a paper-sheet, and discussed that with one other respondent. After that the discussion was opened-up to a plenary discussion that focused on a reflection on the scores and the apparent preferences and perceptions about strategic policy design in the group.

Empirical findings

Findings of the survey

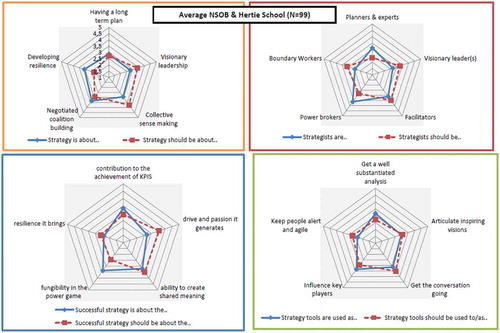

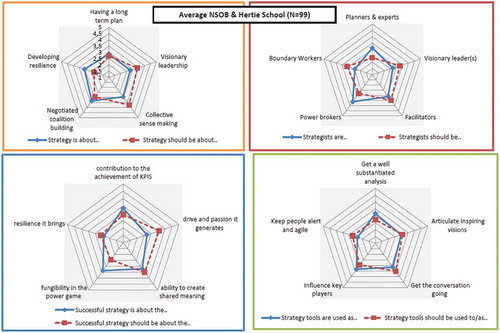

We will discuss the findings from the survey here; Appendix 3 presents the full scores of the survey. For the ‘ist-situation’ we found that most respondents see the current practice as coalition building (P4) and as capacity building (P5). However, respondents note that the practice should be more about collective sensemaking (P3) and visionary leadership (P2).

The second dimension asks what a successful practice currently is and what it should be. Many respondents say that a successful process currently (ist) is measured by its success in playing the power game (P4) and the direct contribution to Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s) in the organization (P1). However, respondents think that success of a process should (soll) be measured by the passion it generates among everybody working on the issue (P2), and the ability to create shared meaning among them (P3).

The third dimension looks at the ‘strategist’, or ‘designers’ themselves: what type of practitioners are required for doing this type of work? Strategists are currently (ist) seen mostly as power brokers (perspective 4), and as planners and experts (P1). However, respondents want (soll) strategists to be more facilitators (P3) and visionary leaders (P2).

The fourth dimension, the use of tools for strategic design, shows that respondents think that tools are mostly used for rational analysis (P1). However, they think that tools should be used more to get the conversation going (P3) and to articulate inspiring visions (P2). Tools should be used less as instrumental and analytical tools, and more as ‘vehicles’ for developing shared meaning (P3) and a joint vision for the organization (P2).

In general, the survey shows that for the ist-situation there is much attention for the powergame perspective (P4) and the perspective of rational-planning (P1). Strategy is considered a highly politicized process; build around functional or symbolic rational analysis and planning. For the soll-situation respondents have a strong preference for to the leadership perspective (P2) and for the sensemaking perspectives (P3). According to the respondents, strategy should be more about collective sensemaking and visionary leadership, and less of a powergame or analytical exercise. The perspective of deliberate emergency (P5) does not score very high for both ist and soll; respondents do not recognize it as a valuable perspective for finding robust policy solutions for complex policy issues, and do not see it being done in their own practice.

Findings from the feedback sessions

The results of the survey were used for discussions with the respondents. Each respondent received both their individual scores of the survey and the average scores of the whole sample as input for the feedback sessions. presents an example of an individual score, and see Appendix 2 for a figure of the average group score.

In the first part of the discussion respondents reflected directly on the survey data. Here again, the ist situation was described by most participants as a powergame, with the process mostly designed to get key players on board, or neutralize their resistance to a plan. Additionally, the expert perspective was recognized as very dominant in the everyday strategic practice. The respondents made it clear they would prefer to see more of the leadership and sensemaking perspective, because this would help to get more people involved in the process. The soll situation should in the eyes of participants be characterized more by visionary leadership and by more interaction facilitated by them as policy designers.

However, during the discussion respondents started to reconsider their initial views. They still saw the reality of strategy to be mostly about the power game, but began to nuance the gap between the ist and the soll of strategy. The discussion especially focused on what it meant that respondents apparently desire a different perspective than the ones they use in their practice. The power game perspective was seen as ‘wrong’, at least in the results of the survey. However, in the discussion during the feedback sessions the question was raised whether it is really wrong to aim for a strategy that organizes a dominant power-coalition that actually enables action? Respondents noted that the context in which they work demands consensus building and requires them to be pragmatic; therefore, also sensitive to organizational politics, bargaining, and political feasibility of proposals. Moreover, in the discussion they were less positive about the leadership-perspective. Respondents argued that their positive attention for this perspective in the survey was mostly a complaint about a lack of guidance and involvement of senior leadership in policy design processes in their practice; they were not pleading for a ‘visionary leader’ to take them by the hand, but wanted to see more involvement and also a sense of purpose from the senior leadership; not just technical management, but also more reference to the greater public cause by leaders in the organization.

The same goes for the call for more sensemaking-efforts; respondents valued the idea that finding solutions for complex policy issues is very much a collaborative process, in which a wide range of voices should participate. Respondents felt that a good process requires everyone to be able to bring his or her ideas and expertise to the table; according to the respondents, designing a solution for a complex policy issue requires less of a drawing board and more of an open space for discussion.

Moreover, during the feedback sessions it became apparent that respondents distinguished between two ‘stages’ of their design processes; a front-stage and a back-stage. At the front-stage, respondents reported that they would ‘perform’ rationality, leadership, data-analysis, and use tools for strategic planning. They would present their work and their process in the language and outputs that suit the perspective of rational planning; a rational analysis to enable a process of structured and objective decision about a policy or strategy.

Back-stage they would do things differently. Participants argued that in the back-stage processes they would have a lot of attention for collective sensemaking (P3), for the political power game (P4), and also attempt to build-in elements of capacity for emerging issues and emerging insights (P5) into their design; even though that perspective (P5) scored low in the survey. Respondents were aware that they although they were presenting confidently their front-stage plans, they knew that their assumptions were often wrong or had a short expiry date. However, for them this did not matter all that much; simultaneously with their confident front-stage plans, they organized a parallel back-stage process that took uncertainty much more into account. Respondents argued that the reason to do this back-stage is that they do not think it will hold in the dynamics of the front-stage; when asked what is the most important ‘stage’ was for them they unequivocally answered that the back stage is where it really happens; however, they also were quite sure that what they did backstage was probably not accepted as a front-stage strategy. Even though they all build in elements of capacity building in their designs, they did not think that would be accepted as a ‘formal strategy’ for dealing with uncertainty. Interestingly, they were not all that negative about this practical combination of realities. The front-stage served a purpose, they argued; a good front-stage performance allows participants to do back-stage what they think is really important. Without a good front-stage ‘rational-planning’-performance all of the other valuable elements could not be performed back-stage.

summarizes how the respondents think about the processes front-stage and back-stage.

Table 3. The front-stage and back-stage of strategy.

Conclusion

In this paper we have used the strategy-literature to distinguish five different perspectives for how to arrive at a robust policy design; or as we have phrased it here, to ‘do’ robust policy design. Instead of the often-used perspective of design as a rational-analytical planning-process, there is a wide variety of coherent approaches to produce robust policy design; or to do strategizing, as the literature on strategy refers to it. Each of them involves deliberate and conscious design of policy options, but with different rationales, a different focus, and different notions of how a good strategy or design is made. The literature-study makes clear that each theoretical perspective can produce a robust design; the perspectives represent distinctly different routes that practitioners can take to arrive at the same ‘strategic’ destination.

However, the survey-feedback study shows that policymakers hold interesting views on the practical merit of each perspective. When asked to score the perspectives on normative preference and empirical reality, the powergame perspective (P4) and the rational-planning perspective (P1) stand out as the empirical reality. Policy making is considered politicized, a battleground for turf wars. That political process is covered in the language and instruments of rational analysis and planning. Moreover, in the survey respondents argue that strategy should be different (soll); they have a strong preference for to the leadership perspective P2 and the sensemaking perspectives (P 3). The perspective of capacity building (P5) is not valued positively for both the ist and the soll situation; respondents do not see it happen in practice and do not think it should.

The discussions in the feedback sessions nuanced this initial image from the survey. During the discussions respondents were less outspoken about the political dimension of strategy. They recognized it in practice, but were far less negative about it; they considered it an inherent element of the public sector. They took it deliberately into account; as a legitimate route to arrive at a supported design. In fact, most respondents considered themselves quite good at this political power game and acknowledged that their ability to create coalitions was an important reason for them to get their job; and hold it. Moreover, they nuanced the need for ‘leadership’; they claimed that this normative call for ‘vision’ should be interpreted as a sign of the current missing of inspiring leadership in their organizations. They wanted a bit more of that, but do not see pure visionary leadership as a good route for arriving at a robust policy design for a complex issue.

What became clear in the feedback sessions was that participants see two ‘stages’ for doing strategy; a front stage and a back stage. On the front stage they pretend strategy to be objective, planned, controlled, and phased. But the real strategizing happens back-stage, where it is a process of small steps, in an incremental process, while keeping a good eye on participation and a broad ownership in the organization. The reasons for the separation in two stages is, according to participants, the fact that their environment would otherwise not accept the outcomes of a design process; people want strategy to be planned, objective and controlled, even though they probably know it looks more improvised in reality. At least, that is what they think; we did not check with their management or with politicians.

Discussion

When we go back to our research question, we can draw several conclusions. We asked ourselves how robust policy design is done. We found that what policy design is and how it should be done depends on the perspective one picks, or the combination between perspectives for that matter. Each perspective highlights different elements in what is important in design processes and what drivers for a successful design process are; this can be helpful for policymakers who want to design policy, but also for scholars who study current design practices or look at cases of successful or failed policy designs.

It is interesting to reflect on the different perspectives in the strategy-literature. There are many different approaches to doing strategy and these are all well-described in the literature. However, the underlying message of prominent strategy-scholars such as Mintzberg (Citation1994), Whittington (Citation1996), and Jarzabkowksi (Citation2005) is that for all the conceptual variety the strategy field remains dominated by a ‘strategy-as-planning’ perspective of strategy. All of the other perspectives serve mostly as ‘counter-weights’ against the dominant normative perspective of strategy as a rational-analytical process; that is something strategy scholars worry about and it is important for the design-practice as well; practitioners and researchers should be able to differ between perspectives.

The emerging field of policy design may take warning from this observation from the strategy literature; the language of policy design is inherently rationalistic; a design is a deliberate and conscious effort to relate means to strategic goals, and that seems to lead naturally to a rational-analytical model for ‘doing’ it. But, as we have seen in the literature and in the empirical study there is a variety of ‘rationales’ for doing strategy; deliberate design can be done ‘rationally’ in distinctly different ways (Mintzberg, Citation1994).

This observation is all the more important because we have seen that the rational-analytical model is not very well suited for the conditions that require robustness; uncertainty, complexity, and volatility complicate attempts to model the environment and ‘calculate’ a robust solution for a problem. The rational-planning perspective is well-suited for tamed problems in a stable environment, but becomes much harder to work from when conditions are uncertain and volatile. Not only are other approaches available, they are much needed to develop real robust designs for complex problems in an uncertain and volatile context.

These observations and lessons from the strategy-literature are in line with the lessons from the empirical study we conducted. When we asked practitioners how they ‘do’ design and how they think it should be done, it was interesting to see how they made a clear distinction between a rational-analytical front-stage, and an entirely different back-stage. The practitioners claimed that ‘back-stage’ was where the ‘real strategizing’ took place. In fact, what the practitioners claimed they did in practice was very much a process of small steps towards a predetermined goal, of making sense of developments along the way, finding common ground with others in the organization, and building capacity to deal with unexpected developments. All this suggests that there is already a large body of practical experience with different rationales in policy design, where robustness is achieved in practices that deviate from the traditional frame of the rational-analytical perspective. For the practitioners in our survey-feedback working on the two separate stages was not really a problem; they were used to it and made the most of it. They argued that they were able to manage the two different stages in their work; a front-stage where there is rational-analysis and a back-stage where they work from other rationales to really design policy. It will be interesting to study this more deeply, in order to develop more specific theoretical models for designing for robustness.

Future research could look into the effectiveness of various perspectives, and also the effectiveness of particular combinations of perspectives. Most practitioners say that they vary between perspectives, for instance in different phases of the project, or for different types of tasks in a design process. It is interesting to see if certain combinations go together well and produce more robust designs. Moreover, it is interesting to conduct more direct observations of design processes as they take place, for instance by means of systematic observation studies, such as conducted by Rhodes, ‘T Hart, and Noordegraaf (Citation2007) who observed the daily practice of government elites; or by specific ‘practice-research’, such as done in the ‘strategy as practice’-research (Jarzabkowski, Citation2005; Johnson et al., Citation2007; Whittington, Citation1996); research into ‘policy design as practice’ could help researchers to develop more insight in how design is done, and help practitioners to ‘do it’. In the executive programs that we used as platform for our empirical study we experienced the practical need for more practical models for ‘doing design’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Martijn Van der Steen

Martijn van der Steen, PhD is Professor of Public Administration at Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and is Associate Dean of the Netherlands School of Public Administration, in The Hague, The Netherlands.

Mark van Twist

Mark van Twist, PhD is Professor of Public Administration at Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and is Dean of the Netherlands School of Public Administration, in The Hague, The Netherlands.

Notes

1 Total response was 104 with 5 invalid entries (48%) and non-response was 112 (52%, mainly due to complaints about the length of the survey). Respondents were participants in executive education programs of the Netherlands School of Public Administration (NSOB, The Hague) and the Hertie School of Governance (Berlin).

References

- Ackoff, R. L. (1993). Idealized design: Creative corporate visioning. International Journal of Management Science, 21(4), 401–410.

- Aldrich, H. E. (1979). Organizations and environments. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Allison, G. T. (1971). Essence of decision – Explaining the Cuban missile crisis. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

- Andrews, K. R. (1971). The concept of corporate strategy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones Irwin.

- Ansoff, H. I. (1965). Corporate strategy. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Bailey, A., & Johnson, G. (2001). A framework for managerial understanding of strategy development. In H. Volberda & T. Elfring (Eds.), Rethinking strategy (pp. 212–230). London: Sage Publications.

- Bennebroek Gravenhorst, K. (2007). Shaping a learning process and realising change: Reflection, interaction and cooperation through survey feedback. In J. J. Boonstra & L. de Caluwé (Eds.), Intervening and changing: Looking for meaning in interactions (pp. 261–276). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Bennis, W., & Nanus, B. (1985). Leaders: The strategies for taking charge. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Björklund, C., Grahn, A., Jensen, I., & Bergström, G. (2007). Does survey feedback enhance the psychosocial work environment and decrease sick leave? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16(1), 76–93.

- Boin, A., & van Eeten, M. J. G. (2013). The resilient organization. Public Management Review, 15(3), 429–445.

- Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1997). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice and leadership. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Boonstra, J. J. (2004). Conclusion: Some reflections and perspectives on organization, changing and learning. In J. J. Boonstra (Ed.), Dynamics of organizational change and learning (pp. 447–475). Chichester: Wiley.

- Capano, G., & Woo, J. J. (2018a). Designing policy robustness: Outputs and processes. Policy and society, 37(4), 422–440.

- Capano, G., & Woo, J. J. (2018b). Agility and robustness as design criteria. In M. Howlett & I. Mukherjee (Eds.), Routledge handbook of policy design (pp. 420–434). London: Routledge.

- Cavana, R. Y., & Mares, E. D. (2004). Integrating critical thinking and systems thinking: From premises to causal loops. System Dynamics Review, 20(3), 223–235.

- Chia, R. (2004). Strategy-as-practice: Reflections on the research agenda. European Management Review, 1(1), 29–34.

- Christensen, C. R., Andrews, K. R., Bower, J. L., Hamermesh, R. G., & Porter, M. E. (1982). Business policy: Text and cases. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

- de Caluwé, L., & Vermaak, H. (2003). Learning to change: A guide for organization change agents. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Deal, T. E., & Kennedy, A. A. (1982). Corporate cultures. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Drucker, P. F. (1970). Entrepreneurship in business enterprise. Journal of Business Policy, 1, 3–12.

- Drucker, P. F. (1974). Management: Tasks, responsibilities, practices. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- French, W. L., & Bell, C. H. (1999). Organization development behavioral science interventions for organization improvement. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Glueck, W. F. (1980). Business policy and strategic management (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Mc Graw-Hill.

- Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1994). Competing for the future. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Hamel, G., & Välikangas, L. (2003). The quest for resilience. Harvard Business Review, 81(9), 52–63.

- Head, B., & Alford, J. (2013). Wicked problems: implications for public policy and management. In Administration & society, 47(6), 711-739. doi: 10.1177/0095399713481601

- Hedley, B. (1977). Strategy and the business portfolio. Long Range Planning, 10(1), 9–16.

- Hendry, J. (2000). Strategic decision making, discourse, and strategy as social practice. Journal of Management Studies, 37(7), 955–977.

- Howlett, M., Capano, G., & Ramesh, M. (2018). Designing for robustness: Surprise, agility and improvisation in policy design. Policy & Society, Introduction to this Special Issue.

- Howlett, M., & Mukherjee, I. (2014, November 13). Policy design and non-design: Towards a spectrum of policy formulation types. Politics and Governance, 2(2), 57–71.

- Jaques, E., & Clement, S. D. (1991). Executive leadership: A practical guide to managing complexity. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Jarzabkowski, P. (2005). Strategy as practice. London: Sage Publications.

- Johnson, G., Langley, A., Melin, L., & Whittington, R. (2007). Strategy as practice. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1995). The leadership challenge: How to keep getting extraordinary things done in organizations. California, CA: Jossey- Bass Publishers.

- Kuhnert, K. W. (1993). Survey-feedback as art and science. In A. I. Kraut (Ed.), Handbook of organisational consulting (pp. 1–14). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Llewellyn, S., & Tappin, E. (2003). Strategy in the public sector: Management in the wilderness. Journal of Management Studies, 40(4 June 2003 0022–2380), 955–982.

- Lusk, S., & Birks, N. (2014). Rethinking public strategy. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions: The organizational basis of politics. New York: Free Press.

- Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. (1978). Organizational strategy: Structure and process. New York, NY: Mc Graw Hill.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning. New York: Free Press.

- Mintzberg, M. (1987). The strategy concept I: Five Ps for strategy. California Management Review, 30(1), 11–25.

- Morçöl, G. (2012). A complexity theory for public policy. New York: Routledge.

- Nanus, B. (1992). Visionary leadership: Creating a compelling sense of direction for your organization. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Narayanan, V. K., & Fahey, L. (1982). The micro politics of strategy formulation. Academy of Management Review, 7(1), 25–34.

- Noordegraaf, M., van der Steen, M., & van Twist, M. (2014). Fragmented or connective professional-ism? Strategies for professionalizing the ambiguous work of policy strategists. In: Public administration 92(1), 21–38.

- Peters, B. G. (2017). What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program. Policy and Society, 36(3), 385–396.

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1973). The politics of organizational decision making. London: Tavistock Publications.

- Porter, M. E. (1979). How competitive forces shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, 57, 137–156. March–April 1979.

- Pye, A. (1995). Strategy through dialogue and doing: A case of “Mornington crescent”? Management Learning, 26(4), 445–463.

- Rhodes, R., ‘T Hart, P., & Noordegraaf, M. (Eds.). (2007). Observing government elites; Up close and personal. New York: PalgraveMacMillan.

- Schwenck, C. R. (1989). Linking cognitive, organizational and political factors in explaining strategic change. Journal of Management Studies, 26(2), 177–187.

- Steiner, G. A. (1969). Top management planning. New York: Macmillan.

- Stewart, J. (2004, December). The meaning of strategy in the public sector. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 63(4), 16–21.

- Sutcliffe, K. M., & Vogus, T. J. (2003). Organizing for resilience. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 94–110). San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Swanson, D., & Bhadwal, S. (Eds.). (2009). Creating adaptive policies: A guide for policy-making in an uncertain world. New Delhi: Sage Publications India.

- Teisman, G., Van Buuren, A., & Gerrits, L. (Eds.). (2009). Managing complex governance systems. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Välikangas, L. (2010). The resilient organization. New York, NY: Mc Graw Hill.

- Walker, W., Marchau, V., & Swanson, D. (2010). Addressing deep uncertainties using adaptive policies. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 77(6), 917–923, Special Section 2.

- Walker, W. E., Haasnoot, M., & Kwakkel, J. H. (2013). Review: Adapt or perish: A review of planning approaches for adaptation under deep uncertainty. Sustainability, 5, 955–979.

- Weick, K. E. (2001). Making sense of the organization. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K., & Obstfeldt, D. (2002). High reliability: The power of mindfulness. In F. Hesselbein & R. Johnston (Eds.), On high performance organizations (pp. 7–18). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2001). Managing the unexpected: Assuring high performance in an age of complexity. San Francisco: Josey-Bass.

- Whittington, R. (1993). What is strategy – And does it matter? London: Routledge.

- Whittington, R. (1996). Strategy as practice. Long Range Planning, 29(5), 731–735.