The essays in this issue of Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes have been developed from papers that the authors were invited to deliver at a small symposium, convened by Stephen Forbes and myself, at the Santos Museum of Economic Botany in December 2014. In my original invitation, I asked for contributions that would explore the temporality of landscape, from several periods and places, and from a range of scholarly perspectives.Footnote1 Gardens are subject to the vicissitudes of time through their incorporation of organic materials (if present), their exposure to the seasons, and historical shifts in taste and fashion. The experience and reception of landscape design also unfolds diachronically in time. In addition, the imagery and ornamentation of gardens have frequently made reference to actual or imagined pasts. This issue addresses these themes with reference to a wide range of historical landscapes, from ancient Rome to Günther Vogt’s recent proposal for the redevelopment of Parliament Square in Westminster, London.

The first essay, by Annette Giesecke, focuses on ancient Roman garden complexes. Beginning with the Emperor Hadrian’s Villa Adriana near Tivoli, she addresses the strikingly ‘cartographic’ character of Roman landscape design, in which representations of widely dispersed territories of the empire were juxtaposed. Notably, these images included places from the realms of religion and myth, as if they had an equal reality. As Giesecke suggests, the experience of these landscapes ‘must have been dizzying, transporting the visitor back and forth through space — from “place to place” — and through time’.

Stephen Forbes’ study of the themes of ‘constancy’ and ‘flux’ in botanic gardens also draws on ideas that first emerged in the ancient world. His essay assesses the relevance of Theophrastus’ definition of the botanic garden as ‘a living plant collection established for an enquiry into plants’ to the understanding of subsequent botanic gardens, especially the one established at Padua in 1545. Forbes’ own career as a director of botanic gardens informs his discussion of the problem of temporality in living collections of plants, which necessarily encompasses the preoccupation of botanical science with what William Stearn has described as the ‘quick and the dead’.

Forbes’ essay is followed by my own contribution, which seeks to elucidate the role and temporal effects of the motif of the ruin in sixteenth-century Italian designed landscapes, especially that of the Sacro Bosco in Bomarzo. Stephen Bending also considers ruins in an essay on the relations between time, the body, and the emotions in mid eighteenth-century landscape gardens. He examines several texts from the period for what they reveal about the experience of time in landscape reception, paying close attention to the writings of Henry Home (Lord Kames), Elizabeth Carter, and Thomas Whately, as well as the deleted and revised passages in William Gilpin’s manuscripts on Tintern Abbey. As Bending argues, these errata offer a fascinating picture of the picturesque writer struggling ‘to articulate his imagining of the past as at once historically distant and immediately felt’.

In the next essay, Jennifer Milam focuses on the Jardin de Monceau by Carmontelle (Louis Carrogis). She pays close attention to Carmontelle’s desire to depict ‘all times and places’ in the garden, which she relates to eighteenth-century philosophies of temporality and spatiality. Milam argues that the multi-temporal experience of the Jardin de Monceau expresses a distinctly cosmopolitan ideal.

John Dixon Hunt, whose visit to Australia the symposium was timed to coincide with, and who delivered the first presentation of the day, concludes this issue with an essay on the contribution of walking to the reception of designed landscapes. In his wide-ranging text, he addresses the neglected importance of the ‘art of walking’ to the emergence and development of the picturesque as well as its continuing relevance to modern and contemporary design. Hunt’s emphasis on the importance of the ‘duration’ of landscape experience was a keynote of the symposium as a whole.

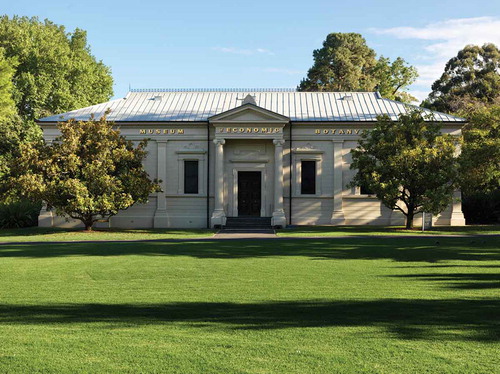

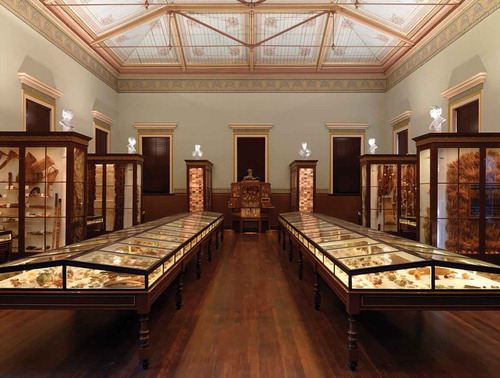

The Santos Museum of Economic Botany, situated at the heart of the Adelaide Botanic Garden, proved to be an ideal location for the themes of the symposium. It is itself a unique time capsule — the last public museum of economic botany to survive from the nineteenth century. The Museum’s classicizing design, complete with a pedimented portico supported by ionic columns, recalls the ‘follies’ erected in the landscape gardens of eighteenth-century England (). In contrast to the primarily visual purpose of the folly, however, the Adelaide Museum has always had an important pedagogical function. Since its construction in 1881 (which makes it the first example of the Greek Revival architectural style in South Australia), it has operated continuously as an object-based collection of knowledge about plants and their varied ‘economic’ benefits (). There are few places in Australia, or elsewhere for that matter, where one can compare over 500 expertly painted papier mâché models of fruit and fungi, made to scale in Germany between 1866 and 1890 (), before turning one’s attention to a fine Victorian vitrine containing examples of the plant-based narcotics and stimulants harvested and prepared by Indigenous peoples. To visit the Museum is to step back into multiple pasts and places — a disorientating experience not unlike, perhaps, that of the Villa Adriana many centuries ago.

FIGURE 1. Exterior view of the Santos Museum of Economic Botany. Photograph by Grant Hancock. Reproduced by permission of the Board of Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium (South Australia). Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

FIGURE 2. Interior view of the Santos Museum of Economic Botany. Photograph by Grant Hancock. Reproduced by permission of the Board of Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium (South Australia). Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

FIGURE 3. Detail of the model apples. Photograph by Paul Atkins. Reproduced by permission of the Board of Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium (South Australia). Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

The temporal dimensions of designed landscapes and their reception were further explored in the exhibition organized by Tony Kanellos to complement the symposium. Postcards from the Edge of the City was an exhibition of historical postcards, one of which is depicted on the front cover of this issue, depicting the Adelaide Botanic Garden from 1905 to 1915.Footnote2 The brief inscriptions on the postcards were at least as interesting as the images, which documented the changing appearance of the garden over a ten-year period. The hundreds of messages and comments, however apparently mundane, together comprise an extraordinary archive of responses to the garden by the people who visited and made use of it, suggesting the tantalizing possibility of a micro-historical study of a single Australian landscape in the Edwardian era. Not unlike the Santos Museum of Economic Botany itself, these postcards from another time offer a glimpse of an alternative history in which temporality, flux, and duration are acknowledged as active constituents of landscape experience.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Stephen Forbes, the Executive Director of the Adelaide Botanic Garden, who was a model collaborator — enthusiastically providing financial support, hospitality, and the venue. I am equally indebted to Tony Kanellos, the Curator of the Santos Museum of Economic Botany, for his many contributions to the organization of the symposium and for curating the associated exhibition. Thanks also to the Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture at Monash University for additional financial support as well as to Antony and Mary-Lou Simpson for generously hosting a reception for the speakers at the Adelaide Club. I am particularly grateful to the anonymous referees of the essays presented here, and to John Dixon Hunt for his invitation to publish them as a special issue of Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes. It is, finally, a pleasure to thank the participants for their engaged and thought-provoking responses to the theme of the symposium.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The dedicated literature on the topic is small, though many historians have addressed issues of temporality and its representation in landscape design indirectly. See, for a recent survey of the topic, Mara Miller, ‘Time and Temporality in the Garden’, in Gardening: Philosophy for Everyone (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), pp. 178–191. Denis Ribouillault’s ‘Landscape “All’antica” and Topographical Anachronism in Roman Fresco Painting of the Sixteenth Century’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 71, 2008, pp. 211–237, offers a sophisticated reading of the status of time and anachronism in Renaissance landscape painting, with many interesting implications for the study of designed landscapes. A previous earlier issue on ‘time’ was published in this journal (34/1) in 2014, guest edited by Sonja Duempelmann and Susan Herrington.

2. See the exhibition book: Out of the Past: Views of Adelaide Botanic Garden, ed. Tony Kanellos (Adelaide: Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, 2014).