Abstract

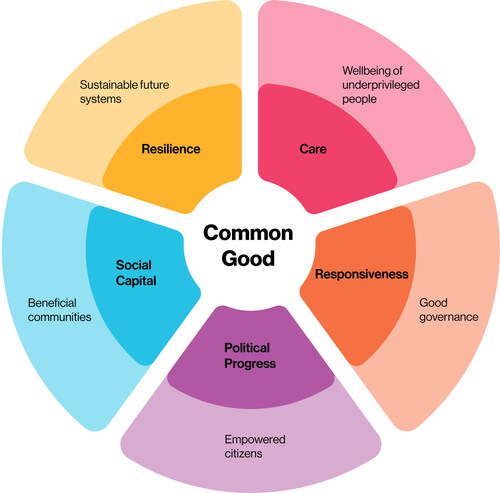

Although the term social design is being widely adopted around the world, conceptual clarity is still lacking. The way social design is understood and executed can vary greatly. Without a shared conceptual foundation, knowledge exchange and development are restricted, and so is the professionalisation of practice. This paper brings forward a framework that unites all social design around an overarching objective to foster the common good but argues that design activities to do so may be driven by different values and focus on different outcomes. We identify five components of social design: (1) care-driven design activities for the wellbeing of underprivileged people, (2) responsiveness-driven design activities for good governance, (3) political progress-driven design activities for empowered citizens, (4) social capital-driven design activities for beneficial communities, and, (5) resilience-driven design activities for sustainable future systems. We describe how the framework helps explain, discuss and systematically study social design.

Introduction

Although social design has become increasingly popular over the last two decades, the field does not have a unified theoretical structure, allowing different interpretations of it to co-exist. But without a strong conceptualization of social design, our knowledge transfer cannot exceed the level of sharing best practices, or subjective reflections and visions. Without definitions, it becomes difficult to formulate hypotheses, to validate them and build theory. In this paper, we assume that social design is a new conceptual foundation for design that plays a decisive role in the emergence of the new paradigm in design (Dorst Citation2008), especially in our times of complexity (Davis Citation2008).

This paper offers a framework to help us recognize, distinguish and address the many existing forms of what is labelled as ‘social design’. Without claiming to oversee the complete field, we tried to be inclusive regarding the various contemporary manifestations of social design. The framework intends to recognize what all forms of social design have in common and to highlight their differences by looking beyond usual ‘tautological’ definitions of the social. The value of this is threefold: it supports (1) identification of distinctive practices of social design; (2) knowledge exchange within practice and academia; (3) identification of routes for maturing as a field.

Background: A new social turn in design (2000–2020)

First used by László Moholy-Nagy in 1947 to indicate the responsibility of designers in our societies (Citation1969)Footnote1, the term ‘social design’ is not as new as it appears at first glance. As a term, it has gradually gained increased importance since Victor Papanek (Citation1971) called for a new social agenda for designers. Yet since a decade or two, the emergence of ‘a specific social design’ is being witnessed (Julier et al. Citation2016), and many renowned scholars have been discussing this new turn in design (Margolin Citation2015; Dorst Citation2019). Rather than an in-depth review, a chronological reflection on noteworthy developments in this area will illustrate the great variety of forms of social design that currently exist.

Moving away from commercial business

Since Papanek (Citation1971) made an explicit call to focus on the real needs of people, the close ties of design with commercial business have been a topic of debate in social design. In 2002, Margolin and Margolin argued for a nuanced view and proposed to see commercial and social areas of work as extremes on a continuum rather than opposites, where ‘the difference is defined by the priorities of the commission’. Since the market cannot take care of all social values, they draw parallels with social work and define social design as meeting the needs of ‘people with low incomes or special needs due to age, health, or disability’ (Margolin and Margolin Citation2002).

Around the same time, design scholars in the UK explored the potential role of design in safety issues at the Design Against Crime programme, established by Gamman in 1999 at Central Saint Martins. By including an abuser perspective within design, alongside the regular user perspective (Gamman, Thorpe, and Willcocks Citation2004), chairs and bike parking furniture were designed to complicate theft of bags and bikes. In close collaboration with criminologists, the value of design in dealing with safety issues is still being exploredFootnote2, through what is called a socially responsive design practice (Thorpe and Gamman Citation2011).

In 2006, the UK Design Council published a report on what is called Transformation Design (Burns et al. Citation2006). The report discusses the value of a user-centred perspective in redesigning public services, yet considers transformation design a separate practice since it challenges the borders of design, since it involves ‘designing beyond traditional solutions’. Being part of this development, Brown, chief executive officer of design company IDEO, later co-authored a report Design for Social Impact that describes their learnings from doing design for and implementing design within ‘organisations whose resources are limited’ (Brown Citation2008). Brown published Change by Design (2009), and a paper on ‘design thinking for social innovation’ (Brown and Wyatt Citation2010). In 2011, Wyatt launched IDEO.org that uses design thinking to ‘improve the lives and livelihoods of people in poor and vulnerable communities around the world’.

Social relations as object for design

Around 2006-2008, a design research network started to formalise under the name Design for Social Innovation towards Sustainability (DESIS): a global network that aims to promote the value of design in fostering locally embedded alternative ways of living that are more socially cohesive and sustainable, and eventually design for this at different scales (Manzini Citation2009; Manzini and Staszowski Citation2013). Even though Manzini distinguishes social design from design for social innovation, his work is considered key in the field of social design.

Exploring different assets of design, but with a similar focus on ‘the local’, Design Activism has developed in this decade as a social design practice positioned between art and politics. In reference to activism as political actions for social change, concepts like resistance and protest are key here. In an attempt to define the ‘design’ in design activism more specifically and theoretically, Markussen proposes a framework for ‘disruptive aesthetics’: an experiential quality of an intervention with potential to disrupt existing power structures (Markussen Citation2013).

Bringing design as strategy within the systems that require change

Pushing design to the strategic level, Boyer, Cook and Steinberg publish Recipes for Systemic Change that explains the set-up of ‘studios’ as formats to engage in strategic design with multiple stakeholders around a particular complex issue (Boyer, Cook, and Steinberg Citation2011). For five years, Sitra funded this lab to explore the strategic power of design in meeting the complex societal and systemic challenges like sustainable housing, local governance and the future of education.Footnote3 In Denmark the Mindlab was founded: as an innovation unit as part of the government, funded by three of Denmark's ministries and Copenhagen Municipality. Designers were to support policy developers and other key decision makers ‘to view their efforts from the outside-in, to see them from a citizen’s perspective’. Christian Bason led the lab for seven years, and became a thought leader in the field of public and policy design that studies the role of design in transforming the culture of the public sector and developing more responsive services (Bason Citation2010).

Design as a tool for unfolding social complexities

After this first decade, a more modest role for design in dealing with social problems got explored. Design, not as problem-solving, but rather as an approach to lay bare the structure of complex social issues. For instance, Björgvinsson and colleagues discuss the role of participatory design in creating space for ‘agonistic struggles’, a dialogue to illuminate opposing concerns rather than seeking consensus (Björgvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren Citation2012). Similarly, DiSalvo et al. (Citation2011) argue that the collective articulation of issues is a significant part of social design practice. And Blyth and colleagues argue for a radical constructionist approach for designers to engage in how a social problem is constructed (Blyth, Kimbell, and Haig Citation2011).

Further expansion in scope and time

The upcoming field of Transition Design coined in 2015 by Irwin and colleagues positions itself as building upon design for social innovation (Irwin, Kossoff, and Tonkinwise Citation2015). Although transition design is still mostly a theoretical concept (there are some cases, e.g., Dahle Citation2019), it repositions designers to commit themselves to long-term visions and coordinate change accordingly, meaning social design is something different than regular design practice employed in social contexts.

Reflecting on these developments, we see a first generation of social designers who indeed started to work outside the commercial context, focusing on underprivileged societal groups, and developing products and services to lift their living conditions. Later, the design process as a means to empower people or transform organisations received more emphasis. More contemporary forms, explore new design forms to address systemic complexities. Hence, the main aim to improve collective life remains intact over time, yet the focus as well as the means to do so can vary greatly and is rapidly developing.

A problematic term

Although we see some signs of a slowly maturing academic field, our knowledge of social design is limited. The first research into social design as an emerging practice of design was done by Armstrong and colleagues, funded by AHRC in the UK, and got published in 2014. Two years later, the International Journal of Design published a special issue on the topic (Chen et al. Citation2016). Many social design projects are subject of case study research; sporadically, the processes and tools in social design are assessed (Tromp and Hekkert Citation2016); and gradually we see some critique (Janzer and Weinstein Citation2014; Von Busch and Palmås Citation2016; Julier and Kimbell Citation2019; Kimbell and Julier Citation2019). Yet, how to structure the field and define the term is still a topic of academic debate.

While Margolin (Citation2015) enlarged the scope of social design to the design of a good society at large (including the design of ‘institutions and social systems’), Manzini (Citation2015, 64) keeps defining social design in the sense of Margolin and Margolin (Citation2002), i.e., design which deals with ‘problematic situations (such as extreme poverty, illness, or social exclusion, and circumstances after catastrophic events)’. Manzini prefers to define his broader codesign-grounded approach as design for social innovation, yet his approach is not the same as Bason’s design for public sector innovation. However, Manzini acknowledges design can play a role in both top-down and bottom-up processes of social innovation (Manzini Citation2014) and defines design for social innovation as ‘everything that expert design can do to activate, sustain, and orient processes of social change toward sustainability’ (Manzini Citation2015, 62).

While explicitly disclaiming Manzini’s definition of social design, Markussen (Citation2017) is equally keen to distinguish social design from social innovation and social entrepreneurship. In his view, social design focuses on micro-level change rather than the large-scale effects social innovation and entrepreneurship are after. In an earlier attempt to clarify the different manifestations of social design, Koskinen and Hush (Citation2016) propose three different types of social design: utopian, molecular and sociological design. Utopian social design takes up large-scale global issues and uses design to bring about change to them. Molecular social design is the work done with marginalized communities to improve their living conditions on the ground. And sociological social design builds on sociological theory and focuses on the relationships between people and things. Markussen explains how his framework of social design resonates well with molecular social design, but not so well with the other two types of social design, and frankly discards the latter for its reliance on very specific theories from only one discipline, which runs counter to the integrative nature of design.

Acknowledging the fact that social design can manifest itself in various forms, Armstrong and colleagues decided to define it broadly: ‘social design highlights the concepts and activities enacted within participatory approaches to researching, generating and realising new ways to make change happen towards collective and social ends, rather than predominantly commercial objectives’ (Armstrong et al. Citation2014, 28). The difficulty to strictly define social design is highlighted by the editors of their special issue on social design (Chen et al. Citation2016). The term is ‘uncomfortable’ (Julier and Kimbell Citation2016) and ‘murky’ (Markussen Citation2017). Some question whether social design could have ‘a definition in a dictionary’ (Koskinen and Hush Citation2016) or some refuse to see it as a concept at all (Manzini, referred to by Tonkinwise Citation2015). Nevertheless, there is a growing interest in social design within the design community (Gaudio, Franzato, and De Oliveira Citation2016) and an increasing number of design students, schools, practitioners and scholars use the term. In our view, this indicates that the only way forward is to develop an inclusive theoretical ground for the many interpretations and manifestations that exist. This paper is an attempt to contribute to that.

Research approach

The aim of our study is to build a coherent lens to understand the variety of social design forms. The unit of analysis is the design case: we critically reflect on design activities and outcomes presented as design projects in reports or on websites, or reported as case studies (). We only included cases that described an innovative intervention that was deliberately developed to achieve social outcomes, indicating that there had been design activity taken place in reference to a social goal. This meant we did not exclude cases based on its commissioning, nor the sector in which it took place. Consequently, we included design cases that can be described as social innovation or social entrepreneurship. Our analysis is not an historical account of how various social design manifestations emerged (which requires analytical reasoning). Our aim is rather to offer a useful framework for describing, studying and engaging in any social design practice (for which synthetic reasoning is required). We took a comparative research approach, including the following steps in developing and testing the framework with peers and practitioners in different countries.

Table 1. Main projects design cases used for the generation of the model.

Step 1: Semantic mapping

The first step was to deal with the uncomfortable term ‘social design’. We defined all the synonyms we could imagine for the adjective ‘social’ and selected a design project we considered exemplary for it. The main criterion here was to avoid tautology as much as possible. We came up with a first list of terms linked to an example case: altruistic, participatory, relational, public, communal, non-commercial, ethical, sustainable.

Step 2: Crossing the adjectives with design activity elements

We discussed commonalities and differences between the cases we had on the list. The fact that the ‘social’ could relate to different aspects of design obstructed a clear discussion (e.g., in participatory design the social relates to the design process rather than to the design problem). We needed another dimension to be able to structurally distinguish social design forms. Building on the four design elements proposed by Dorst (Citation2008, Citation2019) to describe design activity (i.e., object, actor, context and process), we could better specify the ‘social’ within the design case, leading to an emerging list of social design forms ().

Table 2. Emerging list of social design forms.

Step 3: Discussing boundary cases

Since cases we did not agree on as examples of social design were particularly useful, we decided to list some boundary cases (real or imagined) in order to discuss the borders of social design (e.g., ‘the design of a private jet for the prime minister’ could strictly speaking represent ‘public design’ since it happens within the public sector, but we agreed it was not social design). Result of step 3 was the introduction of a core axiom that binds all social design forms, which is ‘design with the primarily aim to foster the common good’.

Step 4: Applying the principle ‘maximum effect, minimum means’

Now that we had a list of specific social design forms, each of which related to the core axiom, contained a definition, and an example case, we wished to get rid of any redundancy and simplify as much as possible (e.g., all social design is ethical because of its core axiom, but not all ethical design is social design). Step 4 resulted in a preliminary version of the model that consisted of a minimal list of social design forms that are conceptually distinctive and that could represent any social design manifestations.

Step 5: Discussing and iterating with peers

This preliminary version of the model was discussed during a faculty seminar with professors and graduate students at The Ohio State University Department of Design (USA). Some participants argued the model would create boundaries to the field rather than unifying it. The discussion revealed that the social design forms were interpreted as categories, and as such led to exclusion. We labeled them as ‘components’ instead of ‘forms’ to indicate it could refer to part of a case rather than being a category a case had to be assigned to. Step 5 resulted in a revised list of social design components that function to characterize existing social design projects by enabling combinations.

Step 6: Detailing and refining definitions

The labels of the social design components caused problems in clarity because of the many connotations the terms already had. This obstructed the understanding, the use and the potential value of the model. We decided to give up the synonym-based labels of social design and placed the values more centre stage. For instance, what was first labelled as ‘altruistic design’ is now called ‘care-driven design’. Step 6 resulted in revised terminology and the final version of the framework.

Step 7: Evaluating with practitioners

We presented and discussed the framework in a session of the Social Design Showdown that targets the social design community in The Netherlands, through a workshop with several practitioners. The internal logic of the framework was understood and accepted, various practitioners (both designers and professionals from the client organisations) mentioned it clarified a lot. Also, it is currently adopted as part of a Canvas to help social design professionals give shape to their projects in dialogue with their client(s) at the start of a projectFootnote12.

Five components of social design: An initial framework

The Social Design Components framework presents five distinctive components of social design, referring to design activity driven by a distinctive value and aiming for a distinctive goal, as a specific way to foster the common good (). Although we intend these five components to be able to describe contemporary forms of social design and to professionalise these, this initial framework is developed to evolve over time by adding, updating or removing components.

The elements of the framework

The framework is made up of three elements: a core axiom (small centre core), social values (medium middle circle), and social goals (large outer circle). The core axiom is what all social design activities and projects have in common: to primarily serve the common good. The social values are the values that drive design activity committed to the common good and the social goals are specifications of the common good that correspond to these values. The framework must be read from the centre to the periphery: in order to contribute to the common good (centre core), design is driven by one or several social values (middle circle), which leads to the achievement of one or several related social goals (outer circle). This leads to five distinct components of social design that describe five different types of design activities social designers may engage in.

Core axiom

Despite the various emergent interpretations of social design, it is generally admitted that its main driving value is public welfare or the ‘common good’ (Dorst et al. Citation2016) - sometimes also formulated as the ‘social good’ (Bason Citation2016) or the ‘good society’ (Margolin Citation2015). Fostering the common good is therefore the ultimate purpose of social design. Several scholars have given their own formulation of this core axiom. For instance, Victor Margolin goes as far to say that all design should be geared towards societal benefit when stating: ‘I claim that the ultimate purpose of design is to contribute to the creation of a good society’ (Margolin Citation2015, 30). Kees Dorst clearly sees design as a discipline that is indisputably part of building a better society: ‘We build a society by agreeing on what we have in common, and pursuing what is commonly good for all of us’: this is a ‘huge creative challenge’ for which ‘we need design’ (Dorst et al. Citation2016, 2). And Alain Findeli considers that ‘the purpose of social design is to improve or at least maintain the habitability of the world of our fellow citizens’ (Findeli and Ellouze Citation2018). This is why the framework is based on the core axiom: we engage in social design when we primarily aim to foster the common good (through design).

Social values

For the last fifty years, industrial design has become increasingly socially responsible: the practice improved in ethical terms. Social design is one manifestation of this, and as such, social design is intertwined with design ethics. Like Von Busch and Palmås (Citation2016) state: ‘the “social” part of design has become an ethical statement about designing itself’. In other words, at the core of social design there is a value claim. This does not mean that social design is the same as value sensitive design or design for values (Van den Hoven, Vermaas, and Van de Poel Citation2017). It means that social design is a specification of design for values in which only values aligned with the common good are considered - we call them social values. We consider five social values key: care, responsiveness, political progress, social capital, and resilience. Care is considered as the responsibility for the safety and well-being of someone or something; responsiveness as the quality of responding/reacting quickly and appropriately; political progress as the progress in freedom and justice-based norms (Ypi Citation2018); social capital as the quality/number of relationships and networks that can be mobilized for personal benefitFootnote13 or better cooperation in society (Bourdieu Citation1986); and resilience as the capacity of social, economic, and environmental systems to cope with disturbances, responding in ways that maintain their essential function, identity, and structure, yet allow for adaptation, learning, and transformation (Pachauri et al. Citation2014, 127).

Social goals

We identify five goals that constitute five distinctive specifications of the common good: wellbeing of underprivileged societal groups, empowered citizens, good governance, beneficial communities, and sustainable future systems. These all can serve as a goal for design activities. They all contain an object, and a quality of that object that the design activity aims to improve. For instance, activities may target underprivileged societal groups (object), and aim to improve their wellbeing (quality). Or they target systems (including different stakeholders and organizations) and improve their sustainability.

Five components of social design

A social design project can exist of multiple social design components, or can exist of only one component.

Care-driven activities for the wellbeing of underprivileged people

Care-driven design activities aim to increase the wellbeing of those who are underprivileged. Care is not understood here in the same way as in ‘ethics of care’, although many connections are possible (Tronto Citation1993). Focus is on individual people (or groups of people) who are underprivileged in reference to a global or societal norm, and successful design improves their standard of living. The basic idea is not to design for the (more or less) wealthy consumer, but to see design as a way to meet the special or basic needs of people who somehow are vulnerable, disadvantaged, underrepresented, underserved or marginalized. This means on a national scale, that design is used to help the poor, the homeless, the aged, the disabled, the mentally ill, and so on. On a global scale, this means design for the populations of those countries that have not yet managed to bring the general quality of life to an ‘acceptable’ level. Existing gaps between (generally accepted or subjective views of) standards of living and the (perceived or measured) quality of life of a selected group of people is the raison-d’être of care-driven design. Humanitarian design, inclusive design, design for all, base-of-the-pyramid design, to name a few, often place this component of social design centre-stage.

Responsiveness-driven activities for good governance

Responsiveness-driven design activities aim to help public/non-profit organisations to be more responsive to the needs of their beneficiaries. This means these activities are directed at civil servants, volunteers or non-profit employees (rather than the ultimate users of public service alone), and successful design improves their knowledge/skills/vision or the procedures/processes/performance of the department/organisation. One could argue that social design in general often improves the quality of public and social service through the design of a product, service or system, and by doing so, infuses design thinking and methods in the organisation. However, the design activities that are driven by responsiveness are explicitly developed to target the organization: they are set-up and executed in order to challenge and change the culture and thinking within the organisation. The notion that design thinking, supported by design methods, tools and techniques, can substantially improve the problem-solving processes and innovation strategies of public/non-profit organisations is the driving force in responsiveness driven design. Design for policy, public design, design of civic tech, or public sector innovation have a focus on this component of social design.

Political progress-driven activities for empowered citizens

Political progress-driven design activities challenge/attack restrictions in freedom. Focus is on explicit and implicit governance structures and their embedded ideologies and norms, and successful design has established an improvement in power relations or distribution (i.e., empowered citizens). This type of design activity focuses specifically on freedom restrictions and injustice in the broadest sense of the word: how the public in general is being ruled, next to how specific groups (e.g., women, the LGBTQ + community, black people, adolescents, the elderly) are oppressed, controlled, or discriminated against because of existing governance structures. To stand-up against the existing forms of rule and ultimately transform governance structures or processes is the main purpose of this type of design. Design activism, social graphic design (e.g., the design of pamphlets and campaigns, or describing the perspective of underrepresented groups through visual communication) and critical design that engages with social issues are examples of design that adopt this component of social design.

Social Capital-driven activities for beneficial communities

Social capital-driven design activities support or generate new forms of collaboration towards collective ends. Emphasis is placed on social interactions between people as a stepping-stone for building a local or digital community, and successful design increases the quantity and quality of relationships between people. In social capital-driven activities, people or end-users are considered explicitly as social beings: people who are part or can become part of a community based on shared values. The goal is to innovate for collaboration and to seek new forms to do things together and better. The key idea in social capital-driven activities is that innovation is not limited to the development and production of goods or services alone, but applies to the development of social organization too. Through new services, we create new relationships. Recognizing this, understanding existing relationships, and conceptualizing and prototyping new ones, is key in these activities. This social design component is often part of design for social innovation and the design of sharing economy services.

Resilience-driven activities for sustainable future systems

Resilience-driven design activities aim to instigate or catalyse systemic change directed at a better future for all in the long run. Focus is on societal and ecological systems and successful design realizes a contribution to a paradigmatic shift within these systems. This contribution can be measured at different levels, e.g., changes in social norms, governing principles, system components, etc. In resilience-driven activities, the focus is not so much on direct improvement, but rather to instigate changes that may require time (as is in the case of transition design). It typically focuses on systems we are all affected by (e.g., around consumption, immigration, food, health or education) and it acknowledges the interrelatedness of (different groups of) people and other life on this planet. The notion is that our future must be radically different, and more than an optimized version of today. Resilience-driven activities help imagine a different future and push our current society into that direction. It takes a systemic approach and expands its user-centred focus to a society-centred one. Activities engage various stakeholders and provide ground for transdisciplinary learning in transitioning towards a more sustainable system. This component is always present in transition design, systemic design and strategic design (as defined by the Helsinki Design Lab), design in/for the Anthropocene.

Discussion

First and foremost, the framework is not conclusive and other components could emerge over time to better define and study social design. In fact, the framework is an invitation to expand and detail social design as a value-driven design practice geared at the common good.

Implications for design research

The five components help recognize the different social design activities that can take place within one and the same project. As such, the framework helps explain the multiple manifestations of social design. An important first step is to validate the framework through a multiple-case study including social design cases from practice. Such a study would help to see if the framework is robust enough to identify different social design manifestations. Additionally, the framework is also intended to expand our knowledge of social design. Firstly, the framework supports systematic comparison of social design cases, and activities, geared at the same manifestation of the common good. As such, we can compare different approaches and learn about their strengths and weaknesses. Secondly, the framework invites collection of data for a single component, supporting the development of specific design theory and methodology to bring rigour to these design activities. And finally, the framework invites us to start measuring the impact of social design. For each component we discussed their goals, which imply indicators for success. The next step is the development of tools to document and interpret data for these indicators, e.g., how to show that social capital has improved through a design intervention? The social design field would benefit greatly from designerly tools to operationalize values and measure effect.

Implications for design practice

Despite the fact that the number of schools that offer social design education increases, many designers who enter practice may still experience their work as pioneering work. Organisations that could benefit from social design are not always familiar with what it could offer, and social designers still experience difficulty to explain it well. The value of our framework in this context is therefore twofold.

First, it offers a starting point to discuss the potential components of a social design project with stakeholders and clients. Although social design projects are generally complex and may be driven by several social values at the same time, the framework could help in articulating and prioritizing the key value(s) driving the project at hand: where do we mainly wish to have an impact, what do we wish to include as well, and what aspects do we leave out of scope?

Second, it will help articulate one’s capacities and strengths in executing social design activities (and to team up with peers for others). Since social design manifests itself in various forms, many different types of social designers exist. The framework could therefore be helpful in articulating what social design activities align with one’s skills and expertise. E.g., being good at developing future visions and communicating these well, is an important asset for resilience-driven design activities. And being able to recognize particular social dynamics and understand how to facilitate its changes, is key to social capital-driven design activities. A better understanding of the required skill set for each of the components will support the positioning of educational programmes for teaching social design.

Limits and further work

Our development of a unified framework has not gone uncontested. Unifying means zooming out and seeking coherence in great variety, rather than zooming in and seeing detail. The framework aims to include and build on renowned approaches to social design (like Manzini’s take on social innovation, Irwin’s ideas on transition design, or Markussen’s notion of design activism) without being able to do justice to the nuances of the work of these scholars. In the paper we indicated what we consider the core social design component of these subdisciplines, though this is topic of further academic debate. Hopefully the framing of social design in terms of a variety of social design activities can help us better identify the value of and navigate the multiple approaches, tools and methods that exist, allowing a constructive academic discussion on how well they align and are complementary. It is remarkable how rapidly the design discipline expands and introduces new terms. This framework is an attempt to seek synergy between design paradigms and philosophies to strengthen the design profession in shaping society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nynke Tromp

Nynke Tromp is an Associate Professor and studies what designers can bring to table in the light of complex societal issues. This refers to the artefact as well as to design thinking and more particularly reframing. Nynke co-founded and co-runs the Systemic Design Lab and Redesigning Psychiatry.

Stéphane Vial

Stéphane Vial is an Associate Professor and leads the Diament Lab, a transdisciplinary research team in design for e-mental health that aims to study, design and develop e-mental health services of high ethical and experiential quality through responsible human-centred design. He has published more than five books on digital media and design, including Being and the Screen (MIT Press).

Notes

1 Moholy-Nagy coined the term “social design” in his book Vision in Motion, with his plea for a “socially oriented design” (p. 55) and his proposal of a “Parliament of social design” (p. 359-361).

2 Also at the Designing Out Crime research center based in Sydney.

4 More about: http://www.desisnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Matt-Lievesley-DESISwisdomteeth-260115.pdf

6 More about: https://www.desisnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/TZU-DESIS-Lab-Spedagi-project_low.pdf

7 More about: https://web.archive.org/web/20170610130735/http://mind-lab.dk/en/case/realisering-af-faelles-maal-folkeskolen

8 More about: https://www.blablacar.com

10 More about: http://www.helsinkidesignlab.org/dossiers/brickstarter.html

11 Ideo.org (2015), Impact – A design perspective, 38-42, accessed February 19, 2018. https://s3.amazonaws.com/ideo-org-images-production/downloads/113/original/IDEOorg_Impact_A_Design_Perspective.pdf

13 Pierre Bourdieu. “The Forms of Capital”. In J. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York, Greenwood, 241-258 (1986).

References

- Armstrong, Leah, Jocelyn Bailey, Guy Julier, and Lucy Kimbell. 2014. Social Design Futures: HEI Research and the AHRC. Brighton: University of Brighton.

- Bason, Christian. 2010. Leading Public Sector Innovation: Co-Creating for a Better Society. Bristol, UK; Portland, OR: The Policy Press.

- Bason, Christian. 2016. Design for Policy. London: Routledge.

- Björgvinsson, Erling, Pelle Ehn, and Per-Anders Hillgren. 2012. “Agonistic Participatory Design: working with Marginalised Social Movements.” CoDesign 8 (2–3): 127–144. doi:10.1080/15710882.2012.672577.

- Blyth, Simon, Lucy Kimbell, and Taylor Haig. 2011. Design Thinking and the Big Society: From Solving Personal Troubles to Designing Social Problems. London: Actant and Taylor Haig.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by John G. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

- Boyer, Bryan, Justin W. Cook, and Marco Steinberg. 2011. In Studio: Recipes for Systemic Change. Helsinki: Sitra, Helsinki design lab.

- Brown, Tim. 2008. Design for Social Impact: How to Guide. New York: The Rockefeller Foundation.

- Brown, Tim. 2009. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation. New York: Harper Business.

- Brown, Tim, and Jocelyn Wyatt. 2010. “Design Thinking for Social Innovation.” Development Outreach 12 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1596/1020-797X_12_1_29.

- Burns, Colin, Hilary Cottam, Chris Vanstone, and Jennie Winhall. 2006. Transformation Design. London, UK: Design Council.

- Chen, Dung-Sheng, Lu-Lin Cheng, Caroline Hummels, and Ilpo Koskinen. 2016. “Social Design: An Introduction.” International Journal of Design 10 (1): 1–5.

- Dahle, Cheryl L. 2019. “Designing for Transitions: Addressing the Problem of Global Overfishing.” Cuadernos Del Centro de Estudios de Diseño y Comunicación 73 (73): 213–233. doi:10.18682/cdc.vi73.1046.

- Davis, Meredith. 2008. “Cover Story - Toto, I've Got a Feeling We're Not in Kansas Anymore….” Interactions 15 (5): 28–28. doi:10.1145/1390085.1390091.

- DiSalvo, Carl, Thomas Lodato, Laura Fries, Beth Schechter, and Thomas Barnwell. 2011. “The Collective Articulation of Issues as Design Practice.” CoDesign 7 (3–4): 185–197. doi:10.1080/15710882.2011.630475.

- Dorst, Kees. 2008. “Design Research: A Revolution-Waiting-to-Happen.” Design Studies 29 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2007.12.001.

- Dorst, Kees. 2019. “Design beyond Design.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 5 (2): 117–127. doi:10.1016/j.sheji.2019.05.001.

- Dorst, Kees, Lucy Kaldor, Lucy Klippan, and Rodger Watson. 2016. Designing for the Common Good. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

- Findeli, Alain, and Nesrine Ellouze. 2018. “A Tentative Archeology of Social Design.” In Back to the Future: The Future in the Past, edited by Oriol Moret, Proceedings of ICDHS 10th + 1 Conference Barcelona. Barcelona: University of Barcelona, 37–39.

- Gamman, Lorraine, Adam Thorpe, and Marcus Willcocks. 2004. “Bike off! Tracking the Design Terrains of Cycle Parking: Reviewing Use, Misuse and Abuse.” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 6 (4): 19–36. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cpcs.8140199.

- Gaudio, Chiara Del, Carlo Franzato, and Alfredo Jefferson De Oliveira. 2016. “Hope against Hope: Tackling Social Design.” Journal of Design Research 14 (2): 119–141. doi:10.1504/JDR.2016.077009.

- Irwin, Terry, Gideon Kossoff, and Cameron Tonkinwise. 2015. “Transition Design Provocation.” Design Philosophy Papers 13 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1080/14487136.2015.1085688.

- Janzer, Cinnamon L., and Lauren S. Weinstein. 2014. “Social Design and Neocolonialism.” Design and Culture 6 (3): 327–343. doi:10.2752/175613114X14105155617429.

- Julier, Guy, and Lucy Kimbell. 2016. Co-Producing Social Futures through Design Research. Brighton: University of Brighton.

- Julier, Guy, and Lucy Kimbell. 2019. “Keeping the System Going: Social Design and the Reproduction of Inequalities in Neoliberal Times.” Design Issues 35 (4): 12–22. doi:10.1162/desi_a_00560.

- Julier, Guy, Lucy Kimbell, Jo Briggs, James Duggan, Kat Jungnickel, Damon Taylor, and Emmanuel Tsekleves. 2016. Co-Producing Social Futures through Design Research. Brighton: University of Brighton.

- Kimbell, Lucy, and Guy Julier. 2019. “Confronting Bureaucracies and Assessing Value in the Co-Production of Social Design Research.” CoDesign 15 (1): 8–23. doi:10.1080/15710882.2018.1563190.

- Koskinen, Ilpo, and Gordon Hush. 2016. “Utopian, Molecular and Sociological Social Design.” International Journal of Design 10 (1): 65–71.

- Manzini, Ezio. 2009. “New Design Knowledge.” Design Studies 30 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2008.10.001.

- Manzini, Ezio. 2014. “Making Things Happen: Social Innovation and Design.” Design Issues 30 (1): 57–66. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00248.

- Manzini, Ezio. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Manzini, Ezio, and Eduardo Staszowski, eds. 2013. Public and Collaborative: Exploring the Intersection of Design, Social Innovation and Public Policy. New York: DESIS Network.

- Margolin, Victor. 2015. “Social Design: From Utopia to the Good Society.” In Design for the Good Society, edited by Max Bruinsma and Ida Van Zijl. Rotterdam: NAi010.

- Margolin, Victor, and Sylvia Margolin. 2002. “A “Social Model” of Design: Issues of Practice and Research.” Design Issues 18 (4): 24–25. doi:10.1162/074793602320827406.

- Markussen, Thomas. 2013. “The Disruptive Aesthetics of Design Activism: enacting Design between Art and Politics.” Design Issues 29 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00195.

- Markussen, Thomas. 2017. “Disentangling ‘the Social’ in Social Design’s Engagement with the Public Realm.” CoDesign 13 (3): 160–174. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1355001.

- Moholy-Nagy, László. 1969. Vision in Motion. Chicago, IL: P. Theobold.

- Pachauri, Rajendra K, Myles R. Allen, Vicente R. Barros, John Broome, Wolfgang Cramer, Renate Christ, John A. Church, et al. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC, 127.

- Papanek, Victor. 1971. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Chicago, IL: Academy Chicago Publishers.

- Thorpe, Adam, and Lorraine Gamman. 2011. “Design with Society: Why Socially Responsive Design is Good Enough.” CoDesign 7 (3–4): 217–230. doi:10.1080/15710882.2011.630477.

- Tonkinwise, Cameron. 2015. "Is Social Design a Thing." https://www.academia.edu/11623054/Is_Social_Design_a_Thing

- Tromp, Nynke, and Paul Hekkert. 2016. “Assessing Methods for Effect-Driven Design: Evaluation of a Social Design Method.” Design Studies 43: 24–47. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2015.12.002.

- Tronto, Joan C. 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge.

- Van den Hoven, Jeroen, Pieter E. Vermaas, and Ibo Van de Poel, eds. 2017. “Design for Values: An Introduction.” In Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design. Dordrecht: Springer, 1–7.

- Von Busch, Otto, and Karl Palmås. 2016. “Social Means Do Not Justify Corruptible Ends: A Realist Perspective of Social Innovation and Design.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 2 (4): 275–287.

- Ypi, Lea. 2018. “What is political progress?”. The Leverhulme Trust. https://www.leverhulme.ac.uk/philip-leverhulme-prizes/what-political-progress