Abstract

Considering the material culture in China, cultural beliefs play a vital role in explaining artefacts, and different values can be revealed by linking Chinese characters and artefacts. Using morphemic analysis, we propose a method for deriving a comprehensive understanding of the hidden interconnections between Chinese characters and artefacts. With the help of blending theory, a cognitive semantic model is proposed. Further, a mapping process is conducted in three phases: sensorial composition between the corporeal layer and the ‘visceral level’, behavioural completion between the behaviour layer and the ‘behavioural level’, and intellectual elaboration between the conceptual layer and the ‘reflective level’. Utilising case studies from traditional and modern times, two types of relationships between Chinese ideographs and artefacts are suggested: denotative and connotative. These relations and the ‘cooperative effect’ show the mutual connections between different forms of material culture in China and demonstrate the cultural beliefs embedded in artefacts.

The language basis of artefact study

In terms of the realisation of a mental template (Deetz Citation1967), an artefact initially refers to object manufactured intentionally for specific purposes (Hilpinen Citation2008). Its proper form inhabits in the maker’s conceptual system and is standardised by production (Deetz Citation1967; Marks, Hietala, and Williams Citation2001; Monnier Citation2006). Such process involves a transformation from concept to reality, which is defined by ‘“traditions” and “social parameters” that “result from mental categories” and are symbolic in nature”’ (Chase Citation2008; Jelbert et al. Citation2018). Hence making an artefact inevitably relies on experiences people learn from the past, and language plays a primary role (Krippendorff and Butter Citation2007).

Language is the way in which, as humans, we experience what we call reality… Experience is not really meaningful until it has found a home in language, and without lived experiences to inhabit it, language is empty, lifeless shell. (165)

From this perspective, language as the key to grasp people’s experiences largely frames the understanding of human-made artefacts as meaningful. Therefore it ‘needs to take language in the use of technology seriously. It is the use of language that distinguishes forms, materials, functions, and problems, and directs designers’ attention to what they are to do with them’ (Krippendorff Citation2006, 23). In other words, artefact making, as a communication medium among individuals, and semantics, as a substantial element of embedding cultural beliefs, can be delivered, and acknowledged among members of a society, like language.

For David Prown (Citation1982), the most significant cultural belief embodied in artefacts is ‘value’ with different kinds. There are the ‘material value’ – involving layout, texture, and colour; ‘utilitarian value’ – involving usage and recyclability; and ‘spiritual value’ – involving the attitude and self-expression of the maker. They entail multiple aspects in making artefacts, including historical, iconographical, aesthetic, cultural, scientific, and behavioural (Viduka Citation2012), and simultaneously portray a holistic picture of an artefact’s cultural belief. Each of these multiple aspects help determine the context of the other.

In this paper, we apply these value concepts to the study of artefacts in China. Bringing the artefacts and Chinese characters together, we can uncover the hidden link between them. Subsequently, the cultural belief of artefact making is explored. Additionally, the Chinese way of constructing meaning in material culture – conceptual blending – is introduced, which plays an important role in relating Chinese characters to artefacts.

The semantic relationship models

Morphemic layers of chinese character formation

It has been pervasively accepted that the real sense of Chinese character emerged in the late Shang Dynasty (Liu et al. Citation2021; N. Wang Citation2002; R. Wang Citation2012), and evolved uninterruptedly for over 3,000 years with six main types (): the Oracle script, the Bronze script, the Seal script, the Clerical script, the Regular script and the simplified script (Qiu Citation1988). All of them show the highly grapheme–constructed patterns (N. Wang Citation2015), meanwhile, manifest the cultural embodied, narrative, and human factor engaged representation of meaning (Ge Citation2020; Liao Citation2012, Citation2013; Xue Citation2020).

Table 1. Script development of Chinese characters.

The Japanese linguist Shirakawa believes Chinese characters to be a kind of ‘myth telling medium’, ordinarily representing a mythical ceremony of mediumistic worship that played a major role in the daily life of ancient people (Shirakawa Citation2014). This implies that they created artefacts for rituals and used them for sacrificial activities and to express reverence. Considering the Chinese character ‘jun (君)’ as an example, its Seal script  comprises graphemes,

comprises graphemes,  ,

,  Footnote1 and a stick-like stroke |.Footnote2 These combine to portray a scenario of ‘a spirit medium holding a sacred staff (|) in his hand (

Footnote1 and a stick-like stroke |.Footnote2 These combine to portray a scenario of ‘a spirit medium holding a sacred staff (|) in his hand ( ), praying in front of a vessel (

), praying in front of a vessel ( )’ (Shirakawa Citation2018, 60–61). Thus, the Chinese character ‘jun (君)’ originally refers to priesthood (spirit medium) who has the dominate power – emperor,Footnote3 which is then imbued with the figurative meaning of lord – a master or ruler having power.

)’ (Shirakawa Citation2018, 60–61). Thus, the Chinese character ‘jun (君)’ originally refers to priesthood (spirit medium) who has the dominate power – emperor,Footnote3 which is then imbued with the figurative meaning of lord – a master or ruler having power.

From this perspective, patterns of Chinese characters show not only a coherent relationship with an artefact’s appearance, such as  , but also reveal how people appreciated, used, and responded to them during ritualistic activities in ancient China: their recognition and manipulation of artefacts, communication with others or deity, and rational thinking are highly depended on their body (Shapiro and Spauliding Citation2021). Therefore, corporeality, behaviour, and concept are elementary features of Chinese characters. We suggest three layers of interpretation that highlight the morphemic features of Chinese characters: the corporeal layer (CorL), the behavioural layer (BehL), and the conceptual layer (ConL).

, but also reveal how people appreciated, used, and responded to them during ritualistic activities in ancient China: their recognition and manipulation of artefacts, communication with others or deity, and rational thinking are highly depended on their body (Shapiro and Spauliding Citation2021). Therefore, corporeality, behaviour, and concept are elementary features of Chinese characters. We suggest three layers of interpretation that highlight the morphemic features of Chinese characters: the corporeal layer (CorL), the behavioural layer (BehL), and the conceptual layer (ConL).

First, the CorL refers to symbolised patterns – the sensorial depiction of an object. Originating from pictographs, the organic sense of Chinese character formation relies on vision – people directly reconstruct what they have seen in two-dimensional symbols and then systemise them into formative graphemes like animals, artefacts, landscapes, etc. This is the most basic aspect of interpretation.

Second, the BehL refers to a spatial combination of graphemes involving human activities – scenarios in which people deal with objects and actions in daily life. These also show the human-centred principles underlying Chinese characters, meaning that several corporeal graphemes can be combined rationally in a representation based on their symbols.

Compared with the two previous layers, the ConL generally expresses abstract meanings and mental images by the representable depiction of real objects and behaviours; it occupies a central role in the semantics of Chinese characters. It is also identical to the semiology terms, denotation, and connotation. On the one hand, the denotative meaning is usually associated with CorL and BehL; the combination of graphemes perhaps represents the literal meaning of the character. On the other hand, the connotative meaning refers to people’s subjective understanding (based on personal experience) and values (based on denotation), which is normally explained as habits, beliefs, attitudes, and historically and culturally sedimented morphologies of people towards characters.

Chinese characters, therefore, ingeniously combine human nature with linguistic interpretations while mirroring deep-rooted cultural beliefs embodied in Chinese consciousness. Moreover, this sets the symbiological foundation for bridging Chinese characters to artefacts.

Design psychology of artefact

Throughout the development of material culture, people has occupied themselves with shaping and altering materials in the ‘artificial environment’, as well as the ‘cultural environment’ involving mental aspects (Gibson Citation1977). Here, we draw upon academic approach that examines the mental aspects of appreciating, using, and responding to artefacts – the embodiment of them – it ‘accounts for the fact that we cannot abstract from our bodily aspects’, taking the embodied reality into consideration seriously (Carbon Citation2019, 7). Regarding artefact making, a major element of the design domain, Norman and Ortony (Citation2003) suggest a ‘user-centred design’ theory for evaluating the psychological responses of people on three levels: the ‘visceral level’, the ‘behavioural level’, and the ‘reflective level’.

The ‘visceral level’ of artefacts involves their biological features, such as appearances, colours, materials, and textures derived from humans’ protective mechanisms – whether a person feels safe or in danger, warm or cold, beautiful or ugly, etc. Such feelings are intricately linked to the physical forms of natural resources that people use for new creations. Thus, the mental reaction at the ‘visceral level’ engenders a ‘proto-affect’ that predicts the psychological response at a higher level (Citation2003).

Designers also attach utilities and functions to artefacts at the behavioural level. This involves manipulating skills given by them and understanding the learning process for users. On the users’ side, the mental reaction at the behavioural level often relies more on a ‘feeling of control’ and inducing expectations subjectively (Norman and Ortony Citation2003). That is, predications may arise in user’s minds when they learn to manipulate artefacts, and they are ‘shaped unconsciously but impact quite consciously experienced actions (Carbon Citation2019, 5)’.

The highest stage of mental activity, the reflective level, connects users’ feelings and behaviours to self-examinations (Norman and Ortony Citation2003), viewing the former two levels as the inevitable bases for how people react to artefact making and articulate feedback. This concept has a coherent relationship with personalised needs (Hou Citation2020), social conventions, popular fashions, and cultural beliefs, while depending on personal experiences that may change. To fully investigate cultural belief embodied in artefacts, further theoretical support regarding the working of such psychological activities, referred to as ‘conceptual blending’ by Fauconnier and Turner (Citation2002, 4–5), is required. Normally, the blending process takes place in the human cognitive system and fills the gap between Chinese characters and artefacts analogically.

Semantic blending of chinese characters and artefacts

Conceptual blending process

According to Fauconnier and Turner (Citation2002), one of the unique capacities of a human being is their ability to construct meaning in tangible forms – text, art, and objects. Even the simplest meaning is built on a complex process of identity, integration, and imagination. It ‘emerges from elements, roles, values, and relations that inhabit or form a conceptual domain referred to as a mental space’ (Oakley and Pascual Citation2017, 423), which is described as ‘small conceptual packet:’

Mental spaces are very partial. They contain elements and are typically structured by frames. They are interconnected and can be modified as thought and discourse unfold. Mental spaces can be generally to model dynamic mapping in thought and language. (Fauconnier and Turner Citation2002, 40)

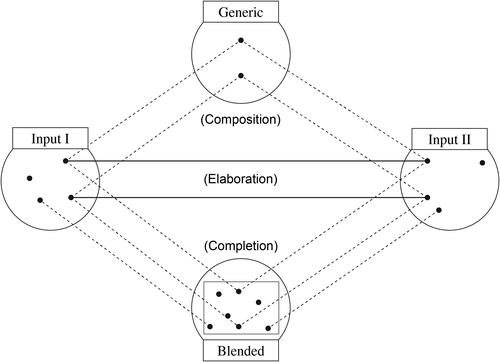

Matching concepts are a fundamental feature of mankind that constantly occur while establishing mental spaces, including input, generic, and blended spaces (). Such mental elements consist of counterparts, which selectively connect to set up a cognitive network by ‘locating shared structures, projecting backward to inputs, recruiting new structures to the inputs or the blend, and running various operations in the blend itself’ (Fauconnier and Turner Citation2002, 44). The blending mechanism based on cross-space mapping procedures involving composition – selectively map of different counterparts, completion – projection of new elements in a blended space, and elaboration – running the blend imaginatively (Wong Citation2021).

Not only the conceptual blending theory has been utilised in linguistic study, such as the change of historical linguistic phenomena (Coulson Citation2001), construction of metaphoric expression (Grady Citation2005), and cultural experience based expression of slang (Wong Citation2021); but also applied for extended field including product design method (Zhu Citation2016), material anchored analysis of artefacts (Hutchins Citation2005), mythology (Cánovas Citation2011) etc. Mapping as the major process of conceptual blending, ensures us interpreting embodiment of material culture, and finding semantic relationship between two constituents (counterparts in inputs) (Benczes Citation2011; Wong Citation2021), in this case, Chinese characters and artefacts.

Relationship model of chinese characters and artefacts

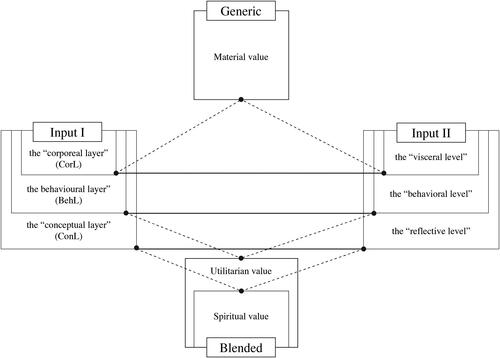

Based on Chinese character formation, psychology of design and conceptual blending process, we draw upon a relationship model, which first locates the linguistic layers and the psychological response levels (to artefacts) in inputs. Subsequently, the mapping is performed, layer by level, to ground the material value in generic space and project cultural attributes of utilitarian and spiritual value in blended space. Thus, the whole blending process includes three phases: sensorial composition, behavioural completion, and intellectual elaboration.

To begin with, the sensorial composition occurs between CorL and the visceral level, assigning graphemes to artefacts’ physical features. This implies that when people first view artefacts, they may immediately recognise the similar features of corresponding Chinese characters, showing that graphemes play a fundamental role in artefact perception. Thus, the sensorial composition sets the underlying link, engendering new connections that do not exist in the inputs of Chinese characters and artefacts.

The blending process then moves to behavioural completion, matching BehL to the behavioural level, and projecting artefacts’ utilitarian value. This phase inevitably involves the story telling process. Crafters intentionally create artefacts with screenplays or scenes and assume that people act in the predisposed manner. Interestingly, even if people develop their own ways of using artefacts, they may acknowledge the guidance that behavioural completion provides – acquiring new utilitarian value while simultaneously recalling the original utility based on their BehL learning experience.

Based on the former phases, the spiritual value can be acquired by matching ConL with the reflective level, signifying the relationship between Chinese characters and artefacts on the highest plane. In China, artefact making normally absorbs its semantics from ideographic graphemes. In other words, the intellectual elaboration (the mental activities of crafters and users) naturally keeps the denotation of characters consistent while further accounting for their diverse connotations.

To combine all phases, we envelop the model such that the blended structure reveals the cultural belief of embodiment of artefacts (). This conceptual framework engages the experiential component of their creative activities. More importantly, it marks the congruous relationship between Chinese characters and artefacts. Such mapping exists pervasively for ancient artefacts and can also be built for modern designs.

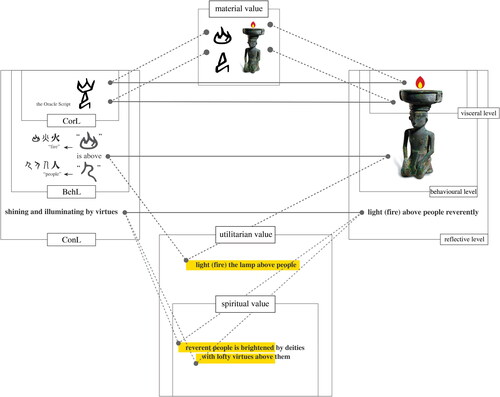

Taking a bronze lamp, which is unearthed from the No. M1017 of YiCheng DaHeKou Tomb, as an example. It shows a very special form like ‘a half-naked man kneeling down on the floor, and carrying a plate (the light holder) on the head (Xie et al. Citation2018, 132)’. Archaeologist has dated this artefact to or at mid-Western Zhou dynasty (K. Wang Citation2020), and others further suggest some relations between the design of lamp and the Oracle script of ‘guang ( , 光)’ – light (Yang Citation2017). The blending process can be built in three steps (): first, external similarity between the designed appearance of lamp (the visceral level) and the CorL is located, composing the figure of kneeling man as its material value. On the following, the behavioural level maps the BehL, and then the reflective level maps the ConL, projecting and integrating the holistic cultural belief. Especially with the intellectual elaboration, the blended space represents the spiritual value as reverent people is brightened by deities with lofty virtues above them.

, 光)’ – light (Yang Citation2017). The blending process can be built in three steps (): first, external similarity between the designed appearance of lamp (the visceral level) and the CorL is located, composing the figure of kneeling man as its material value. On the following, the behavioural level maps the BehL, and then the reflective level maps the ConL, projecting and integrating the holistic cultural belief. Especially with the intellectual elaboration, the blended space represents the spiritual value as reverent people is brightened by deities with lofty virtues above them.

Two types of semantic relationships

After developing the mapping model, we further examine the relationship in two ways: denotative and connotative. Generally, a denotative relation existed in ancient times, while a connotative relation can be more easily found in contemporary times. Sometimes, these relationships may work simultaneously in connections between the different scripts of a Chinese character and designed forms of an artefact, expressing diachronic cultural beliefs with social bonds, fashion trends, and ideological thoughts.

Denotative relation

In the denotative realm, Chinese characters and artefacts have a relationship that links them immediately without difficulty – artefact making derives its expression from the denotation of characters, literally representing cultural beliefs in a blended structure. This can be understood on three levels. First, Chinese characters directly share identical graphemes with artefacts; they are gathered as material value in generic space, establishing the analytical basis for the blending process. Second, utilitarian value is acquired from the mapping between the BehL and the behavioural level. Third, the spiritual value is derived by matching ConL to the reflective level.

Classic examples can be illustrated using the fu – an ancient vessel in China that has a ‘trapezoid shape with diagonal body, handles, distinct corners, plat bottom, open mouth with rectangular edges’ (Xu Citation2013, 16). It is decorated with motifs like a dragon kui (夔), phoenix, taotie (饕餮), cloud and thunder (雲雷紋), and so on. Correspondingly, the modern script of the Chinese character ‘fu’ is 簠, and its Seal script shows a similar pattern as  , while the Bronze script is written differently as

, while the Bronze script is written differently as  . Thus, the CorL and BehL of 簠 can be analysed from two aspects. From one perspective,

. Thus, the CorL and BehL of 簠 can be analysed from two aspects. From one perspective,  shows the top view of

shows the top view of  in a bracket.Footnote4 From another,

in a bracket.Footnote4 From another,  comprises three graphemes: a bamboo-like

comprises three graphemes: a bamboo-like  , a

, a  , and a vessel-like

, and a vessel-like  . In vertical order, it portrays a two-dimensional scenario as

. In vertical order, it portrays a two-dimensional scenario as  is put in a vessel. Subsequently, the ConL represents a kind of container for holding

is put in a vessel. Subsequently, the ConL represents a kind of container for holding  . The grapheme

. The grapheme  , developed from the pictographic pattern of

, developed from the pictographic pattern of  , originally illustrates that grain seeding is growing on field. From this perspective, the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’ derives its literal meaning as a grain container.

, originally illustrates that grain seeding is growing on field. From this perspective, the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’ derives its literal meaning as a grain container.

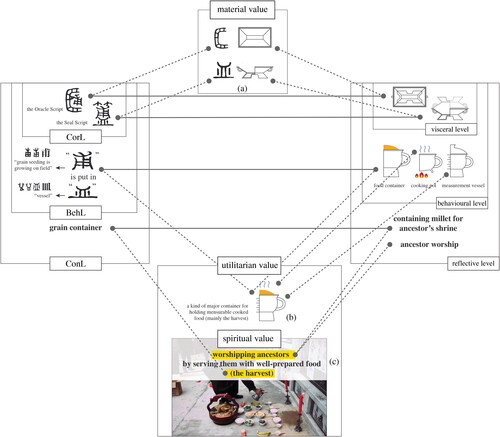

Linking the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’ to the artefact, the blending process proceeds in steps (). First, the sensorial composition occurs between the CorL ( and

and  ) and the visceral level. That is, it assembles the identical external elements of the two inputs in the generic space – the squared mouth with the pattern of

) and the visceral level. That is, it assembles the identical external elements of the two inputs in the generic space – the squared mouth with the pattern of  and the trapezoid body with the pattern of

and the trapezoid body with the pattern of  (). The mapping then proceeds to behavioural completion, matching the BehL to the artefact’s functional factors. According to archaeological documents, the fu appears as a symmetrical moulding with the cover and body, enabling it to be used either in combination or separately (2013). In this case, the vessel can generally be considered a combination of two halves, which provides more flexibility for people to preserve things. Archaeologists also suggest that the fu is designed not only for storing millet but also a dumpling-like food (Hu Citation2007). Thus, it may be used as a food container, cooking pot, or even a measurement vessel. This varied functionality can selectively connect it to the BehL, projecting the utilitarian value as a kind of major container for holding mensurable cooked food (mainly the harvest) (). Subsequently, the ConL maps to the reflective level. The book ZhouLi DiGuan SheRen (Hu Citation2007) states that both fu and gui (簋) are ritual utensils for ancestor’s shrine, containing millet.Footnote5 When rituals were held in ancient times, people usually placed artefacts on the ground as they needed to kneel on the floor to eat, communicate, and pray,Footnote6 common activities among everyone from royals to bureaucrats to ordinary citizens. Thus, fu carries a sense of ancestor worship, while also implying a self-awareness in how Chinese people value their world, including the ritual and musicsystem of worship.Footnote7 This ideology may even match the literal meaning of the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’, and the blended space shows the spiritual value of worshipping ancestors by serving them with well-prepared food (the harvest) ().

(). The mapping then proceeds to behavioural completion, matching the BehL to the artefact’s functional factors. According to archaeological documents, the fu appears as a symmetrical moulding with the cover and body, enabling it to be used either in combination or separately (2013). In this case, the vessel can generally be considered a combination of two halves, which provides more flexibility for people to preserve things. Archaeologists also suggest that the fu is designed not only for storing millet but also a dumpling-like food (Hu Citation2007). Thus, it may be used as a food container, cooking pot, or even a measurement vessel. This varied functionality can selectively connect it to the BehL, projecting the utilitarian value as a kind of major container for holding mensurable cooked food (mainly the harvest) (). Subsequently, the ConL maps to the reflective level. The book ZhouLi DiGuan SheRen (Hu Citation2007) states that both fu and gui (簋) are ritual utensils for ancestor’s shrine, containing millet.Footnote5 When rituals were held in ancient times, people usually placed artefacts on the ground as they needed to kneel on the floor to eat, communicate, and pray,Footnote6 common activities among everyone from royals to bureaucrats to ordinary citizens. Thus, fu carries a sense of ancestor worship, while also implying a self-awareness in how Chinese people value their world, including the ritual and musicsystem of worship.Footnote7 This ideology may even match the literal meaning of the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’, and the blended space shows the spiritual value of worshipping ancestors by serving them with well-prepared food (the harvest) ().

Integrating all these values, the cultural belief of the fu is drawn upon, demonstrating three characteristics. First, Chinese characters share patterns with corresponding artefacts, such as the Bronze script of  and the square shape of the fu. Second, the utilitarian value of artefacts can be acquired from the blending between the BehL and the behavioural level, as the spatial construction of the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’ points to the functions of the corresponding artefact, including holding the harvest. Third, the intellectual elaboration indicates spiritual value; it shows perfect mapping between the mental response of the manipulation of the artefact and the denotation of Chinese characters. A good example is the representation of ancestor worship by linking the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’ to the artefact, which is still observed during the Tomb-Sweeping Festival – wherein people prepare elaborate food items and offer them before their ancestors’ graves.

and the square shape of the fu. Second, the utilitarian value of artefacts can be acquired from the blending between the BehL and the behavioural level, as the spatial construction of the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’ points to the functions of the corresponding artefact, including holding the harvest. Third, the intellectual elaboration indicates spiritual value; it shows perfect mapping between the mental response of the manipulation of the artefact and the denotation of Chinese characters. A good example is the representation of ancestor worship by linking the Chinese character ‘fu (簠)’ to the artefact, which is still observed during the Tomb-Sweeping Festival – wherein people prepare elaborate food items and offer them before their ancestors’ graves.

Connotative relation

The second kind of semantic relationship is called the connotative relation. It highlights metaphor as a fundamental cognitive capacity of mankind, and its essence is ‘understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another’ (Lakoff and Johnson Citation2008, 5). If one deems language, both discourse and characters, as a container for filling meaning (ideas) into objects, metaphor is meaningless unless it is placed in a certain context for better understanding. In this case, the connotative relation involves a deeper level of understanding that emphasises the figurative embodiment of artefacts based on Chinese characters.

Like in the first denotative relationship, structural similarities are initially found between Chinese characters and artefacts. Subsequently, the BehL also plays a significant role in examining utilitarian value. Specifically, the metaphorical meaning is best presented by blending the ConL with the reflective level. This perspective demonstrates some of the subtle ways in which Chinese people express themselves.

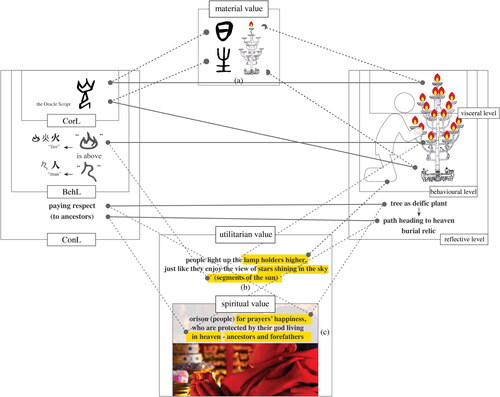

Considering lamp design as an example again, one of the most famous artefacts is the ‘fifteen-branches lamp of Zhongshan’ from China’s Warring States period; it was unearthed from the tomb of King Cuo as a burial relic. It is 82.6 centimetres tall, with seven separate parts, and is decorated with birds, apes, kui (夔), and chi (螭). The sculpture of chi entwining with the trunk represents a kind of dragon born in the forest.Footnote8 Wild animals like apes and birds live on the branches, and two men stand on the ground, feeding the apes (Zhang Citation2020). All these features are vividly displayed on a tree-like body, and its cultural significance is revealed by mapping it to the Chinese character ‘xing (星)’ – star.

The human world entered the era of civilisation when Homo erectus first learned how to manipulate fire. Fire brought not only heated food and warmth but also the possibility of driving away darkness – the original means for humans to pursue light. Volume 3 of XiJingZaJi (X. Wei Citation2017, 42) states that ‘when the emperor steps into the Xianyang palace for the first time… there was a five-branches lamp. When it was fired, the blinking lights like stars shining in the sky’.Footnote9 Thus, the use of a lamp was a metaphor for stars in the sky in Chinese literature. Once again, language becomes a valuable tool to examine an artefact’s expression. The Chinese character ‘xing (星)’ consists of four graphemes in its Bronze script  : three graphemes of ‘sun (

: three graphemes of ‘sun ( , 日)’ and one of ‘birth (

, 日)’ and one of ‘birth ( , 生)’. They are arranged vertically, representing the BehL of star is given birth by the sun.Footnote10 In the book ShuoWenJieZi (Tang Citation2018), ‘birth (

, 生)’. They are arranged vertically, representing the BehL of star is given birth by the sun.Footnote10 In the book ShuoWenJieZi (Tang Citation2018), ‘birth ( , 生)’ means ‘bring forth, like grass and tree growing on earth’.Footnote11 Therefore, a tree, representing a deific plant from ancient times (Zhang Citation2020), refers to the path leading to heaven – not only does it grow on the earth and reach towards the sun in the sky, but it is also praised as the carrier of an ancestor’s soul (Jiang Citation2008) – the spiritual essence of a human being, which also implies a connection to the sun.Footnote12 Therefore, the ConL of the Chinese character ‘xing (星)’ represents paying respect (to ancestors)’ (). When such a symbol is translated in modern times, it may refer to anyone who is held in high regard, like a movie star or a five-star general.

, 生)’ means ‘bring forth, like grass and tree growing on earth’.Footnote11 Therefore, a tree, representing a deific plant from ancient times (Zhang Citation2020), refers to the path leading to heaven – not only does it grow on the earth and reach towards the sun in the sky, but it is also praised as the carrier of an ancestor’s soul (Jiang Citation2008) – the spiritual essence of a human being, which also implies a connection to the sun.Footnote12 Therefore, the ConL of the Chinese character ‘xing (星)’ represents paying respect (to ancestors)’ (). When such a symbol is translated in modern times, it may refer to anyone who is held in high regard, like a movie star or a five-star general.

Figure 5. The blending process between the Chinese character ‘xing’ and the fifteen-branches lamp of Zhongshan.

Subsequently, the blending process begins with sensorial completion. The lamp design corresponds to the CorL, displaying identical features in inputs with holders (as segments of the sun) and sun-like morphemes, the trunk, and the morpheme for birth. Subsequently, behavioural elements are matched – star is given birth by the sun (BehL) and firing (lighting) every holder above man (the behavioural level) – to project utilitarian values, as people light up the lamp holders higher, just like they enjoy the view of stars (segments of the sun) shining in the sky (). Finally, the spiritual value is generated by connecting the connotation of the Chinese character ‘xing (星)’ to the ‘reflective level’ of people communicating with heaven through towering trees. An orison is a wish for the happiness of those who pray to be protected by their gods living in heaven – ancestors and forefathers ().

Combining multiple elements, the cognitive semantics of the ‘fifteen-branches lamp of Zhongshan’ reveals a connotative relation with three characteristics. First, regarding the denotative relation, structural similarity is primarily found between Chinese characters and artefacts through the Bronze script  and the appearance of the fifteen-branched lamp. Second, the BehL plays a significant role in uncovering artefacts’ utilitarian value. In this case, the appreciation of star may apply to the artefact’s usage. Third, the blending phase between the ConL and the ‘reflective level’ shows the cultural coherence of linguistic self-expression both figuratively and in the making of the artefact. An analogous example is illustrated by other artefacts as well, such as the eternal lamp in Buddhist temples, which serves as a metaphor for the believers’ faith in acquiring liberation and wisdom by worshiping the Buddha.Footnote13

and the appearance of the fifteen-branched lamp. Second, the BehL plays a significant role in uncovering artefacts’ utilitarian value. In this case, the appreciation of star may apply to the artefact’s usage. Third, the blending phase between the ConL and the ‘reflective level’ shows the cultural coherence of linguistic self-expression both figuratively and in the making of the artefact. An analogous example is illustrated by other artefacts as well, such as the eternal lamp in Buddhist temples, which serves as a metaphor for the believers’ faith in acquiring liberation and wisdom by worshiping the Buddha.Footnote13

Cooperative effect of the two relations

Occasionally, the two kinds of relations may even work together in explaining artefact making, showing how Chinese people have embedded meaning in tangible forms throughout their long history. The cognitive semantics of artefacts evolve along with changes in Chinese characters, both of which are influenced by the development of linguistic expression.

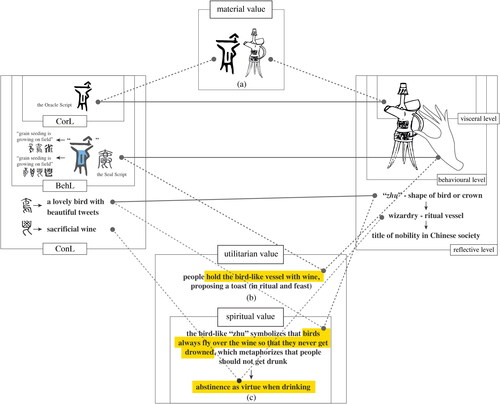

One of the best examples of this symbiotic relationship is illustrated by the jue – a typical wine vessel in ancient China who’s corresponding character shows varied patterns like  (the Oracle script) and

(the Oracle script) and  (the Seal script) in different periods. Such morphemic constructions have confused many researchers due to dissimilar CorLs. For example, the Oracle script

(the Seal script) in different periods. Such morphemic constructions have confused many researchers due to dissimilar CorLs. For example, the Oracle script  directly portrays the outline of a vessel with an arrow-like grapheme on top, a body-like grapheme, a handle-like grapheme, and three leg-like graphemes. Further, the Seal script

directly portrays the outline of a vessel with an arrow-like grapheme on top, a body-like grapheme, a handle-like grapheme, and three leg-like graphemes. Further, the Seal script  comprises three graphemes:

comprises three graphemes:  ,

,  , and a hand-like grapheme

, and a hand-like grapheme ![]() . The BehL demonstrates their spatial arrangement. A hand holds a

. The BehL demonstrates their spatial arrangement. A hand holds a  with

with  on top. From this perspective, the ConL analysis relies on the significance of the grapheme combinations. First, the grapheme of

on top. From this perspective, the ConL analysis relies on the significance of the grapheme combinations. First, the grapheme of  (in hand) represents the scenario as millet made wine is filling in a vessel that can be taken by dagger-like spoon.Footnote14 Therefore, its denotation refers to a kind of sacrificial wine, and its connotation figuratively refers to fragrance of sacrificial wine is served for worshipping deities.Footnote15 Additionally, the grapheme

(in hand) represents the scenario as millet made wine is filling in a vessel that can be taken by dagger-like spoon.Footnote14 Therefore, its denotation refers to a kind of sacrificial wine, and its connotation figuratively refers to fragrance of sacrificial wine is served for worshipping deities.Footnote15 Additionally, the grapheme  as the transformed pattern of character ‘que (雀)’, with its Seal script

as the transformed pattern of character ‘que (雀)’, with its Seal script  and

and  , means a lovely bird with beautiful tweets – sparrow.Footnote16 Hence, the Chinese character ‘jue’ possibly represents a kind of wine vessel with a bird-like shape, although such an explanation is debatable and needs more substantial evidence.

, means a lovely bird with beautiful tweets – sparrow.Footnote16 Hence, the Chinese character ‘jue’ possibly represents a kind of wine vessel with a bird-like shape, although such an explanation is debatable and needs more substantial evidence.

The designed appearance of the artefact jue makes it hard to find the bird-like part on its surface. Here, we choose typical bronze jue as the material (). Its visceral level shows a symmetric body with a rounded bottom, three sharp legs, a zhu,Footnote17 an extended mouth called a liu,Footnote18 and decorative motifs. All these physical characteristics enable people to use the artefact in a specific manner (Gibson Citation1977) suggestive of the behavioural level. People may grasp the body with one hand and drink wine from the curved mouth. Finally, the reflective level is thus achieved, according to Lu (Citation2005), with the design of the zhu originally made in the shape of a bird or crown. Such a solemn design also evokes a feeling of wizardry, which is why it is generally used as a ritual vessel rather than a commodity (Wu Citation2013). Thus, the Jue plays an important role in ancient Chinese rituals and has even become a symbol of nobility in Chinese society.Footnote19

Figure 6. A bronze jue from the 11th century B.C. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/42172.

Thus far, the philological analysis of the Chinese character ‘jue (爵)’ and the corresponding artefact fall into two categories, and the cognitive semantics of jue can be further examined by the intricate blending process (). First, the CorL directly connects to the visceral level – the pattern of  or the artefact appearance with zhu and liu, body shape and legs (). Subsequently, behavioural completion takes place between the BehL of

or the artefact appearance with zhu and liu, body shape and legs (). Subsequently, behavioural completion takes place between the BehL of  and the behavioural level, demonstrating utilitarian value. People hold the bird-like vessel with wine and propose a toast. This shows an attitude of respect for rituals and feasts (). The message could further blend into the ConL. The metaphorical meaning of the grapheme

and the behavioural level, demonstrating utilitarian value. People hold the bird-like vessel with wine and propose a toast. This shows an attitude of respect for rituals and feasts (). The message could further blend into the ConL. The metaphorical meaning of the grapheme  maps to the design of zhu and represents an interesting spiritual value. The bird-like zhu symbolises birds always fly over the wine so they never get drowned, which metaphorizes that people should not get drunk.Footnote20 Considering all these statements in the blended space, the cognitive semantics of jue, even for all wine vessels designed in China, represent the cultural belief of abstinence as a virtue when drinking (). To summarise, when people fill a wine cup in ritual and feast, the birds (zhu) standing on the wine surface may start to tweet, warning them not to drink too much lest they lose sobriety.Footnote21

maps to the design of zhu and represents an interesting spiritual value. The bird-like zhu symbolises birds always fly over the wine so they never get drowned, which metaphorizes that people should not get drunk.Footnote20 Considering all these statements in the blended space, the cognitive semantics of jue, even for all wine vessels designed in China, represent the cultural belief of abstinence as a virtue when drinking (). To summarise, when people fill a wine cup in ritual and feast, the birds (zhu) standing on the wine surface may start to tweet, warning them not to drink too much lest they lose sobriety.Footnote21

Viewed from this blending process perspective, both denotative and connotative relations exist and display semantic cooperation. The sensorial composition shows the first relation in establishing a match – the similarity between the Oracle script  and the artefact appearance. Following that, the behavioural completion and intellectual elaboration phases, which generate utilitarian and spiritual values, reveal the second connotative relation in the metaphorical representation of

and the artefact appearance. Following that, the behavioural completion and intellectual elaboration phases, which generate utilitarian and spiritual values, reveal the second connotative relation in the metaphorical representation of  ,

, ![]() (the action of serving wine), and

(the action of serving wine), and  (the ‘abstinence’ meaning of the bird-like zhu design). Furthermore, they demonstrate the development of cultural beliefs expressed through artefact making. In primitive times, the design of artefacts indicated an explicit link to pictographic patterns; however, as Chinese characters evolved, their semantic representation on artefacts became more metaphorical. Such an argument can also apply to how people make artefacts in modern times – designers should borrow patterns and graphemes from Chinese characters (even for old scripts), examine the contemporary use, build a connotative mapping, and then express metaphorical semantics through forms, functions, and other mental considerations. A Taiwan scholar H.-H. Wang (Citation2014) develops a conceptual blending framework involving localised cultural environment, Chinese character ‘yi (弋)’ – hunting by arrow, and semantic representation of lamp. He then creates a new ‘sun-shooting table lamp’ with the embodiment of hunting for knowledge, demonstrating the second connotative relation with statics of user response.

(the ‘abstinence’ meaning of the bird-like zhu design). Furthermore, they demonstrate the development of cultural beliefs expressed through artefact making. In primitive times, the design of artefacts indicated an explicit link to pictographic patterns; however, as Chinese characters evolved, their semantic representation on artefacts became more metaphorical. Such an argument can also apply to how people make artefacts in modern times – designers should borrow patterns and graphemes from Chinese characters (even for old scripts), examine the contemporary use, build a connotative mapping, and then express metaphorical semantics through forms, functions, and other mental considerations. A Taiwan scholar H.-H. Wang (Citation2014) develops a conceptual blending framework involving localised cultural environment, Chinese character ‘yi (弋)’ – hunting by arrow, and semantic representation of lamp. He then creates a new ‘sun-shooting table lamp’ with the embodiment of hunting for knowledge, demonstrating the second connotative relation with statics of user response.

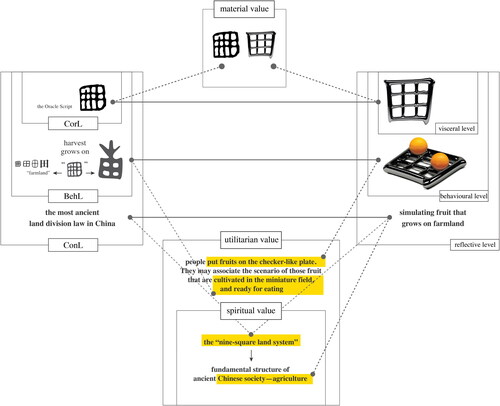

Another contemporary example is the ‘tian’ – a fruit plate design (). By mapping the Chinese character ‘tian (田)’ to a specific artefact, the designer Mak borrowed a pattern from the Oracle script  that signifies farmland, transforming the number of checkers to nine, integrating them into the main body of the plate, and thus expressing the semantics of fruit that grows on farmland. In this case, the first denotative relation is present between the CorL and the plate (the visceral level), and a connotative relation can be found from behavioural completion and intellectual evaluation, thus projecting the utilitarian value of people put fruits on the checker-like plate. They may associate the scenario of those fruit that are cultivated in the miniature field, and ready for eating (see grapheme

that signifies farmland, transforming the number of checkers to nine, integrating them into the main body of the plate, and thus expressing the semantics of fruit that grows on farmland. In this case, the first denotative relation is present between the CorL and the plate (the visceral level), and a connotative relation can be found from behavioural completion and intellectual evaluation, thus projecting the utilitarian value of people put fruits on the checker-like plate. They may associate the scenario of those fruit that are cultivated in the miniature field, and ready for eating (see grapheme  and

and  ). Further, the spiritual value may even recall the concept of the ‘nine-square land system,’Footnote22 the most ancient land division law in China, which further emphasises the fundamental structure of ancient Chinese society – agriculture.

). Further, the spiritual value may even recall the concept of the ‘nine-square land system,’Footnote22 the most ancient land division law in China, which further emphasises the fundamental structure of ancient Chinese society – agriculture.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we apply semantics analysis to artefact making in China, as well as the cultural beliefs embedded in tangible forms. Using cognitive psychology, a new semantic model is suggested by mapping the three layers of Chinese character formation (CorL, BehL and ConL) to psychology of artefact design (the visceral level, the behavioural level and the reflective level) in three phases: sensorial composition, behavioural completion, and intellectual elaboration. This new model not only draws a new picture of understanding material culture in China; but also provides a systematic approach for revealing cultural belief embodied in artefacts with material value, utilitarian value, and spiritual value.

Subsequently, two kinds of relationships are found between representations of Chinese characters and artefact making: denotative and connotative. The denotative relation that normally exists in ancient times represents a kind of primary (or literal) relation between Chinese characters and artefacts, while the connotative relation reveals their metaphorical relation. Both not only emphasise mutual interpretations between different forms of Chinese material culture but also suggest a distinctive direction for modern Chinese designers to build on the past and create new paths ahead, based on the present-day significance of Chinese characters. That means, we argue that the cooperative effect may lead the semantic representation of artefact making, more importantly, it honestly embeds cultural belief in man-made forms associated with Chinese language.

Additionally, two suggestions for future research are offered. First, more cases are required to fully explore the pervasiveness of the two kinds of relations that we have described, especially as they concern new artefacts in modern times and the ‘cooperative effect’. Second, although a new approach has been suggested to examine the relationship between Chinese ideographs and artefacts, further study is needed to put it into contemporary design practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

XiaoChao Xi

XiaoChao Xi is a Lecturer in Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications. The main research areas include design semiotics, cognitive semantics, product design, Chinese material culture. He got a PhD at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. In recent years, he has published related academic articles in international journals and conferences.

Kenny KaNin Chow

Kenny KaNin Chow is an Associative Professor in the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. The main research areas include personal informatics, gamification for behavior change, creativity and cognition, tangible and embodied interaction, user experience, digital media, animation studies. He has published influential academic books, papers in international journals and conferences.

Nan Xia

Nan Xia is a PhD at Academy of Arts & Design in Tsinghua University. His research focuses on how sustainable design could apply to support, facilitate a design of distributed system, and improve its sustainability in the Chinese context.

Notes

1 Ancient ritual vessel for containing praying scroll: 收纳祭祀或起誓文书的容器 (Shirakawa Citation2020, 11). According to Shirakawa’s argument, when putting the praying scroll (‘–’) in ‘ ,’ a new character is formed like ‘

,’ a new character is formed like ‘ (曰)’, which means ‘(someone) saying the praying (sacred) words’ (Shirakawa Citation2018, 85–86).

(曰)’, which means ‘(someone) saying the praying (sacred) words’ (Shirakawa Citation2018, 85–86).

2 ‘|:’ 握持神所憑依的木杖之形 (He, Hu, and Zhang Citation2009, 259; Shirakawa Citation2018, 60)。

3 Emperor: 執掌神事之聖職長官, 君主是其引申義。

4 The Bronze script of ‘bracket’ is ‘ ,’ showing that “things are containing in a bamboo made vessel (《篇海》: 盛物竹器也。).

,’ showing that “things are containing in a bamboo made vessel (《篇海》: 盛物竹器也。).

5 <論語註>:周曰簠簋, 宗廟盛黍稷之器。

6 <祭>: …古者用籩豆簠簋等陳於地, 當時只席地而坐, 故如此飲食為便。

7 ‘Ritual and music:’ 禮樂。

8 <左傳•文公十八年>: 螭魅, 山林異氣所生, 為人害者。

9 <西京雜記>: 高祖初入咸陽宮… 有青玉五枝燈, 燈燃鱗甲皆動, 炳若列星。

10 <說文解字註>: 日分為星。故其字日生為星。

11 <說文解字>: 進也。象艸木生出土上。

12 <史紀•天官註>: 日者, 陽精之宗。<釋名>: 日, 實也, 光明盛實也。

13 <觀心論>: 長明燈者, 正覺心也。覺知明了, 喻之為燈, 是故一切求解脫者, 常以身為台, 心為燈盞, 信為燈柱, 增諸戒行以為添油, 智慧明達喻燈光常然。

14 <說文解字>: 从 ,

,  , 器也;中象米;匕, 所以扱之。

, 器也;中象米;匕, 所以扱之。

15 <說文解字>: 芬芳攸服, 以降神也。

16 <說文解字>: 依人小鳥也。今俗云麻雀者是也。其色褐。其鳴節節足足。

17 ‘zhu:’ 柱。

18 ‘liu:’ 流。

19 <集韻>: 爵位也。

20 <字彙>: 取其能飛而不溺於酒, 以示儆焉。

21 <埤雅>: 一升曰爵。亦取其鳴節, 以戒荒淫。

22 井田制。<通典>:古有井田, 畫九區如井字形, 八家耕之, 中為公田, 乃公家所籍。圭田者, 祿外之田, 以供祭司。加田者旣賞之, 又重賜之田也。

References

- Benczes, R. 2011. “Blending and Creativity in Metaphorical Compounds: A Diachronic Investigation: Metaphor, Metonymy and Conceptual Blending.” edited by S. Handl and H.-J. Schmid, 247–268. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Cánovas, C. P. 2011. “The Genesis of the Arrows of Love: Diachronic Conceptual Integration in Greek Mythology.” American Journal of Philology 132 (4): 553–579. doi:10.1353/ajp.2011.0044.

- Carbon, C.-C. 2019. “Psychology of Design.” Design Science 5: 1–18. doi:10.1017/dsj.2019.25.

- Chase, P. G. 2008. “Form, Function and Mental Templates in Paleolithic Lithic Analysis.” Paper Presented at the From the Pecos to the Paleolithic: Papers in Honor of Arthur J. Jelinek, Vancouver.

- Coulson, S. 2001. Semantic Leaps: Frame-Shifting and Conceptual Blending in Meaning Construction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Deetz, J. 1967. Invitation to Archaeology. New York: Natural History Press.

- Fauconnier, G, and M. Turner. 2002. The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. New York: Basic Books.

- Ge, Z. 2020. “The Original Code of Chinese National Spirit in Chinese Characters.” Journal of Jinzhou Medical University (Social Science Edition) 18 (6): 105–108.

- Gibson, J. J. 1977. “The Theory of Affordance.” In Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing, edited by R. Shaw and J. Bransford, 67–82. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Grady, J. 2005. “Primary Metaphors as Inputs to Conceptual Integration.” Journal of Pragmatics 37 (10): 1595–1614. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2004.03.012.

- He, J., S. Hu, and M. Zhang. 2009. HanZi WenHua DaGuan. Beijing: People’s Education Press.

- Hilpinen, R. 2008. “On Artifact and Works of Art.” Theoria 58 (1): 58–82. doi:10.1111/j.1755-2567.1992.tb01155.x.

- Hou, Y. 2020. “Research on the Application of Emotional Design in Cultural Creative Product Design.” Paper Presented at the E3S Web of Conference, Nanjing.

- Hu, J. 2007. “The Study of the Bronze "Fu" in the Eastern and Western Zhou Periods.” Master, Shaanxi Normal University, Xian.

- Hutchins, E. 2005. “Material Anchors for Conceptual Blends.” Journal of Pragmatics 37 (10): 1555–1577. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2004.06.008.

- Jelbert, S. A., R. J. Hosking, A. H. Taylor, and R. D. Gray. 2018. “Mental Template Matching is a Potential Cultural Transmission Mechanism for New Caledonian Crow Tool Manufacturing Traditions.” Scientific Reports 8 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-27405-1.

- Jiang, D. 2008. “The Harmony and Unity among Divinity, Mankind and Nature - Cultural Interpretations of Tree Worship.” Journal of Southwest Agricultural University (Social Science Edition) 6 (1): 87–91.

- Krippendorff, K. 2006. The Semantic Turn: A New Foundation for Design. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Krippendorff, K., and R. Butter. 2007. “Semantics: Meanings and Contexts of Artifacts.” In Product Experience, edited by N. J. H. Schifferstein and P. Hekkert, 353–376. Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd.

- Lakoff, G, and M. Johnson. 2008. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Liao, W. 2012. HanZi Tree 1: Cong TuXiang JieKai "Ren" de AoMiao. Taipei: Yuan-Liou Publishing Co., Ltd.

- Liao, W. 2013. Hanzi Tree 2: RenTi QiGuan Suo YanSheng de Hanzi DiTu. Taipei: Yuan-Liou Publishing Co., Ltd.

- Liu, J.-H., W. Ke, M-c Hwang, and K. Y. Chen. 2021. “Micro-Raman Spectroscopy of Shang Oracle Bone Inscriptions.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Report37:102910.

- Lu, C.-C. 2005. “The Function about the Columns of Jue: Based on Its Origin.” Huaxia Archaeology 3: 83–90.

- Marks, A., H. Hietala, and J. K. Williams. 2001. “Tool Standardization in the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic: A Closer Look.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 11 (1): 17–44. doi:10.1017/S0959774301000026.

- Monnier, G. F. 2006. “Testing Retouched Flake Tool Standardization During the Middle Paleolithic: Patterns and Implications.” In Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology, eidted by E. Hovers and S. L. Kuhn, 4. New York: Springer.

- Norman, D. A, and A. Ortony. 2003. “Designs and Users: Two Perspectives on Emotion and Design.” Paper presented at The Foundations of Interaction Design, Italy.

- Oakley, T, and E. Pascual. 2017. “Conceptual Blending Theory.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics, edited by B. Dancygier, 26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Prown, J. D. 1982. “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method.” Winterthur Portfolio 17 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1086/496065.

- Qiu, X. 1988. WenZiXue GaiYao. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

- Shapiro, L, and S. Spauliding. 2021. “Embodied Cognition.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. N. Zalta. Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Shirakawa, S. 2014. HanZi BaiHua. Beijing: China CITIC Press.

- Shirakawa, S. 2018. HanZi de ShiJie. Shang. Chengdu: SIchuan People’s Publishing House.

- Shirakawa, S. 2020. HanZi de ShiJie. Xia. Chengdu: SiChuan People’s Publishing House.

- Tang, K. 2018. ShuoWenJieZi. 1st ed., Vol. 1. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Viduka, A. J. 2012. UNIT 15: Material Culture Analysis. Klongtoey: UNESCO Bangkok.

- Wang, H.-H. 2014. “A Case Study on Design with Conceptual Blending.” International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation 2 (2): 109–122. doi:10.1080/21650349.2013.830352.

- Wang, K. 2020. “The Invasion of Huai Yi and the Defense System of the Western Zhou: Based upon the Newly Excavated Bronzes.” The Journal of Ancient Civilizations 14 (4): 54–61.

- Wang, N. 2002. Hanzi Gouxingxue Jiangzuo. Shanghai: Shanghai Education Press.

- Wang, N. 2015. HanZi GouXingXue DaoLun. Beijing: The Commercial Presee.

- Wang, R. 2012. TangLan GuWenZiXue YanJiu. Taipei: Hua-Mu-Lan Culture Publishing Company.

- Wei, X. 2017. “The Analysis of A Miscellany of the Western Capital.” Master, Shandong University, Jinan.

- Wong, M. L.-Y. 2021. “Conceptual Blending and Slang Expressions in Hong Kong Cantonese.” Studies in Chinese Linguistics 42 (1): 97–119. doi:10.2478/scl-2021-0003.

- Wu, J. 2013. “QingTongJue Wei YinJiu LiQi TanXi.” Cang Sang 4: 22–23.

- Xie, Y., J. Wang, J. Yang, and Y. Li. 2018. “ShanXi YiCheng DaHeKou XiZhouMuDi 1017 Hao Mu FaJue.” Acta Achaeologica Sinica 1: 89–183.

- Xu, M. 2013. “The Research of Eating Utensils Characters of ShuoWenJieZi.” Master, Jiangxi Normal University, Nan Chang.

- Xue, W. 2020. “HanZi ChuangFuTuShi Zhong de FenXingXianXiang yu SiWeiTeZheng.” Journal of Nanjing Arts Institute (Fine Arts and Design) 6: 140–144.

- Yang, Y. 2017. “XiZhou JiZuoRenXing TongDeng XiaoKao.” World of Antiquity 4: 8–10.

- Zhang, Y. 2020. “ZhanGuo ZhongShanGuo ShiWuLianZhiTongDeng de KeXueWenHua NeiHan.” East Collections 9: 22–24.

- Zhu, W. 2016. “Product Design Based on Conceptual Blending Cognitive Theory.” Packaging Engineering 37 (6): 119–123.