Abstract

The actor–network theory assumes that human and non-human actors co-act in dynamic networks. As the boundaries between them change according to their connections, the design plays a constructive societal role and can help rebuild and reform societies. Through a case study of China’s health code, this study explains how a heterogeneous network in the social design structure assists institutions in actively or passively transforming a digitalized tool to rebuild and rewrite a part of social orders. It can aid human users operating in communities; however, it can also be used by powerful policymakers as an auxiliary tool. The primary purpose of this study is to investigate the conflict between a hierarchical network and a co-acting network. As social issues become more complicated and unpredictable, the design can either help resolve the problem and guide us towards a more open, equal, and coordinated future, or it can do the opposite.

Introduction

As a specific digitalized tool released during the pandemic, China’s health code has been extensively leveraged in various situations. It is a digital app designed as part of a public health solution to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. A ‘digitalized tool’ is an application or software used via a smartphone, computer, or another form of information and communication technology, whereas a ‘health code’ is a typical digitalized tool serving a specific period; the ‘new normal’ restrictions and unprecedented changes it has brought about continue to affect people’s daily lives. The way in which non-human digitalized tools represent human status is faciitating new strategies for managing population. The effect of the health code’s macro- and micro-influence has seeped into the social structure longitudinally and transversely. Given the mandatory requirements in most areas in China, the health code is used as a proxy for identifying citizens. However, its positive and negative aspects have not yet been considered in terms of social design, even though it has rewritten parts of the social order in China in the pandemic period. According to Buwert (Citation2017), design is always an ethical activity. This implies that design can play both positive and harmful roles. Therefore, this study focuses on the new relationships resulting from the health code’s impact on China’s social order from a social design perspective. In addition, based on actor–network theory (ANT), it revisits the possible digitalized management related to the social change and reconsiders the conflict between a hierarchical network and a co-acting network—for social designers who must face this unprecedented limitation under digitalized control. The study seeks a solution to the potential imbalance that may exist in public affairs, which could affect a substantial portion of the population.

ANT does not imply a concrete area or a specific thing; it is a conception of movement, translation, displacement, absorption, and connections between entities and individuals (Latour Citation2007). Latour recognized that the essence of society comprises a vast network of relationships. The world is a ‘hybrid’ of human actors and non-human substances such as social structures, scientific practices, recognition, and ethical attitudes. The mobility of these non-human substances (henceforth, actors) forms the basis of ‘the network of relationships’ (López et al. Citation2021); these relationships express themselves through various ‘mediators’ such as screens, instrument panels, databases, maps, orders, and restrictions. ANT points out that all social, natural, and technological entities are relational and derive their nature from their relations (Ballantyne Citation2015).

Latour (Citation1987) acknowledged that people and technology could come together to form temporary networks, thus creating assemblages of relations specific to an individual act or a larger event. Similarly, the object-oriented ontology places things at the centre of being. It focuses on equal existence as opposed to positions emphasizing special status, and considers things (objects) as a concept determined by any given object rather than humans’ ‘readiness at hand’ (DiSalvo and Lukens Citation2011). As participants, non-human actors partake in complex, dynamic, and delicate heterogeneous networks. They can be characterized through their actions rather than by using only tools or some certainty standards. As viewed from the social development perspective, human emotions and attitudes pave the future of intentionality, that is, people’s sentiments resonate with their desire for help and the intentionality of participative activities. Many activities and motions are intertwined, and design activity is the needle that stitches together dispersed actors and factors. Non-human actors are increasingly performing both leading and transmitting roles that convert human actors’ positions into programmes for actions. ANT argues that artefacts are deliberately designed to shape or even replace human action, and they play an important role in mediating human relationships, even prescribing morality, ethics, and politics (Latour Citation1991; as quoted in Yaneva [Citation2009]).

The field of design is witnessing increasing discussions regarding the need to promote skills that can resolve social problems and generate innovative solutions (Chick Citation2012). Here, ‘social’ is viewed as the outcome of heterogeneous processes. Human and non-human actors contribute together to the production of society (Michael Citation2017, 12). In their paper, Janzer and Weinstein (Citation2014) define social design as ‘the use of design to address, ultimately, social problems’ (328). Moreover, various researchers have argued that social design must be broadened to a socio-technological perspective. When human society welcomed the Information Age, modern society was chiefly described in terms of ‘smart informatization’, based on a combination of technical and super connectedness. This concept is integrated into information systems, high-speed internet, mobile technology, big data, and cloud computing (Kim Citation2017). Design can be understood as a process of enacting the social aspect by following what both designers and users do and how they engage with, use, and evaluate objects and technologies; assign meaning to their actions; and explain an invention (Yaneva Citation2009). Accordingly, the designer’s role is transformed from providing solutions to providing means and infrastructures (Gürdere Akdur and Kaygan Citation2019), defining issues, and playing against the conventions of who can build a connection between different stakeholders for current and future issues. The context behind the designed process is not an isolated one. Societal improvement accompanies the advancement of these technologies. Between the improvement of society and technology, distinguishing the more dominant conception is challenging, because human and non-human actors are influenced through pluralistic mediation. Growing heterogeneous networks in societies tend to reflect interlaced, interdependent, and even antagonistic relationships via digitalized tools, which are a type of nonhuman actors that primarily translate and mediate human actions in the material world and digitalized space. Wynn (Citation2002) argued that a tool could be described as ‘a detached object controlled by the user to perform work’. Latour goes further in his definition, ‘What, then, is a tool? The extension of social skills to nonhumans’ (Latour Citation1999; as quoted in Rice [Citation2018]). Nowadays, non-human ‘things’ are given more participatory and higher status.

The health code is not only a digitalized tool but also a special mediator for the users. The value and importance of a tool (whether it is a complex digitalized platform or a simple utensil) will decide the actual effect of actions related to its holders and other actors. ANT’s relational ontology implies that all actors have inherent fundamental properties; they only gain power by forming alliances with other actors. For example, the health code, policies, and other executive institutions influence the dominant and recessive power of non-human mediators during a pandemic. However, the transfer status between actor and mediator occurs through dynamic processes; the status between them is not a stable conception. Non-human actors in social design can be viewed as a series of action suppliers that provide a perspective to locate and describe these flowing identity transformations through various activities; they are devoted to building a network with others. Networks are built based on associations between social and material elements, which are dispersed with mediators (Rydin and Tate Citation2016). Moreover, ANT suggests that the practice of heterogeneous actors’ participation represents new materialism. No single act can be executed individually; the mediator is not the surrogate of any network; it is the network itself. However, the value and significance of the network itself emerges through the behaviour. The conceptuallization of the elements in the actor-network theory is depicted in .

Table 1. Conception of the elements in the actor–network theory (ANT).

Materials and methods

Criteria for selecting the case and analysis methods

This study’s case selection criteria are based on four considerations: universality, depth, particularity, and community. Based on the fundamental theoretical conception of ANT, these criteria aim at deconstructing the heterogeneous network and identifying the actors in the new connection rebuilt by a digitalized tool. The four criteria are defined as follows:

Universality: The digitalized tool possesses extensive applicability and can be effectively integrated into the overarching operational structure of society.

Depth: In the context of social dynamics, it is possible to construct micro-connections that exhibit vertical, progressive, and interactive characteristics via digitalization.

Particularity: When engaged in a specific action or objective, it functions in a systematic manner; the collaborative process aims to develop a novel network that tends to establish rules and exhibit orderliness.

Community: The digitalized tool originates from the community, operates within the community, and continually fosters the development of a new community governed by a specific set of rules.

According to pandemic prevention regulations, the health code is widely used in mainland China, especially to verify whether an individual is permitted to perform a specific action. As a specific and typical digitalized tool, the health code has rebuilt a new social network full of dynamic and mediated identifications. In heterogeneous networks, human and non-human actors work in association with each other (Ballantyne Citation2015, ibid). The network is becoming a broad-scope conception without a traditional hierarchy for designers. It might be affected by specific issues, an ideology, and the social or political environment. Regardless of their role, designers are involved in maintaining socio-technical and socio-economic systems. Their work involves human actors authoring, leading, participating, persuading, and coordinating from many moving and alternating positions (Ely Citation2020).

Data collection steps and sources

This research was conducted through a literature review and a case study mainly referring to official reports and policies gathered from the government, news, and operation platforms. The exposition part deconstructs the health code items of the ‘My Ningixa’ app and outlines the operating regulations based on the national pandemic prevention policies, as well as the ‘space–time companion’ of the health code that is a new operating model executed in cities with potential risk. The analysis involves three steps: 1) reviewing the official restrictions and policies, 2) deconstructing and outlining the operation items and regulations of the health code from online platforms (Alipay, Wechat, national government service platform, and health code app), and 3) determining the different roles of the process of using the health code based on ANT. Finally, the social design directions for facing the varying roles of a digitalized proxy are discussed.

Theoretical background

Social design plays a part in a given multidimensional and complex social environment. Nevertheless, the challenge in directing work based on society is that society largely remains an immaterial space. The essence of the social environment is no longer adequately covered by something ‘human-centred’. Conversely, the practices focused on objects or products are less suitable for creating intangible social change in a society (Bjögvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren Citation2012). The study contends that in social design based on ANT’s principle, the conflict between a hierarchical network and a co-acting network is a crucial problem. From ANT’s perspective, humans are not the only actors who can make connections in the artificial world or communities. Latour highlighted the various roles actors play and gave critical advice to the network to ‘follow the actor’ to reveal the humanistic ontology (Ballantyne Citation2015; Latour Citation2007). This ontology can be used to describe the qualitative changes in human and non-human actors’ relationships that are justified by the manner in which mediators mediate and translate them.

When searching for the essential meaning of the public and the purpose of a digitalized tool in influencing social design outcomes, the point is to find the purpose of the action, not its function. Focusing on the function of an action has the potential to mislead the resulting effects and influences while weakening the initial purpose with which the action was performed. The meaning of the public and individual can be easily hidden by a macroscopic and abstract concept when numerous actions are combined to form a vast and dynamic network whose scope of action and impact is constantly being expanded. When the purpose of the action cannot be identified or determined, the process of constant translation within a heterogeneous network has the inherent risk of introducing distortions, modifications, or even complete changes to the initial purpose of an action.

Regarding the platform, it provides an open, flexible, and decentralized system involving various inputs and outputs (Halsall Citation2016). Michael (Citation2017) stated that the social aspect of ANT indicates that it is heterogeneous and laden with non-human technologies, and that nature (the natural environment) is as much a part of society as humans are. The decision-making right of each action will probably be concealed in a black box if the usufruct of a digitalized tool is not supported by a co-acting network, and normal users (the general public) in social design should be investigated in a co-acting network that maintains co-decision conditions and a certain amount of individual will. In this research, the synergy among various types of actors is presented at the surface level and subtle relevance from the decisions of individual actions to the social restrictions are reflected by discussing relative social issues.

Observation of new connections in digitalized tools

China’s health code

In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, China innovated a ‘health code’ programme app with the help of three main telecom operators. The programme used big data to monitor and control the virus’ spread among individuals and help communities contain outbreaks. The app uses opaque algorithms and data sources to provide users with inputs on the risk of infection. The first health code, which was innovated in Zhejiang province, was tested online 40 h after its creation. Thereafter, the first national province health code was officially released on 29 December 2021. The health code’s data comprise information from the following sources:

Registered residence (Ministry of Public Security),

Personal health data declaration,

Travel data (Communication Administration Bureau and Ministry of Transport), and

Outpatient information (National Health Commission, NHS) quotation from newspapers (China Newsweek, 24 January 2021).Footnote1

This system assisted the government in identifying the potential risks of the mass movement of people. The health code’s network includes human actors (citizens, data engineers, medical workers, and government workers) and non-human actors (smartphones, apps, health systems, and service platforms).

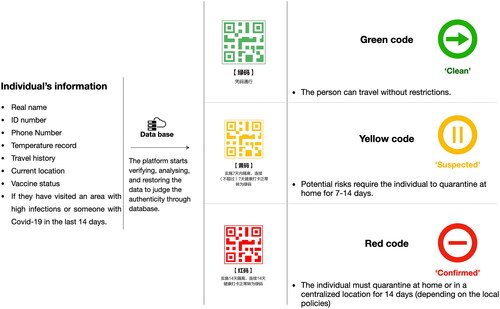

The system was rolled out nationwide after being used in 200 cities. The service design is straightforward; it uses QR codes in three colours to indicate the health status, and the government can obtain the relevant information and verify it, as shown in . Otherwise, the QR code of everyone’s payment, venue code, and parking lot can be used to record their action track. During the pandemic, according to the pandemic prevention policy, individuals had to scan their health code if they wished to enter a public place.

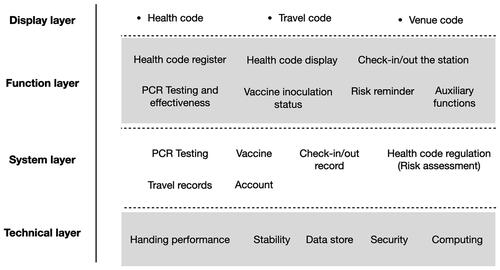

The code connects people through non-human actors. Furthermore, the health code represents the people’s identification and serves as their mediator by determining whether it is safe for them to circulate in the community. The presence of the health code in most mobile phones and the formulation of new policies have jointly created new rules for the contemporary social environment. Therefore, notwithstanding the initial purpose of the health code (i.e. pandemic prevention), it was also used to build a subtle standard for security risk assessment during the pandemic period. The health code platform can be considered a system in which all actors join in and cooperate with its requirements. The initial aim was to clarify the potential risk and mark the confirmed cases, but the users’ intentions have changed the health code’s output, purposes, and roles. In , the health code system is divided into four layers, with each layer illustrating influential components that are relative to the final output.

The health code simultaneously plays different roles at different moments; it is an information collector, translator, monitor, and ruler. The app is designed to assist in determining COVID-19’s red spots in collaboration with various official departments. At the beginning of the outbreak, each province created its quarantine measures via its health codes. When using the health code, the central government could not unify nationwide generation criteria for it. Consequently, the local governments had to determine the generation criteria according to their local standards (risk assessment). This situation created a problem: making mutual authentications between provinces was difficult. At the end of February 2020, a ‘National health code’ was launched on a ‘National government service’ platform, which has since been used for connecting and coordinating with local health code databases, as noted in a China Newsweek article on 27 April 2020.Footnote2 (China Newsweek). According to the ‘Internet + Medical and Health’ ‘Five Ones’ service actions,Footnote3 the government encourages ‘one code’ of its unified national platform to strengthen the connections and mutual recognition between provinces and cities. The health code synthesized multiple institutions and records for implementing a dynamic policy. Consequently, individuals, institutions, and platforms became closely interconnected.

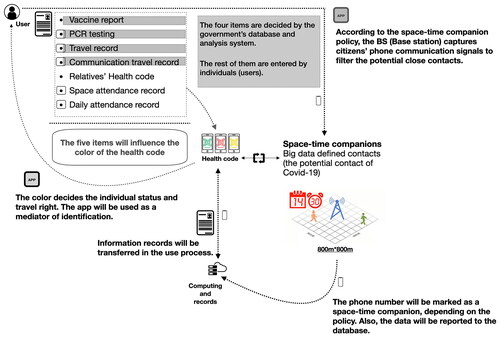

Space–time companion of the health code

With the promotion of the health code in 2021, a new model was released along with the spread of the pandemic, which is a space–time companion. As illustrated in , this new model shows the composite utilization and computation for capturing citizens’ data. A space–time companion designates the mobile phone base station as the centre in which a person confirmed inflicted with COVID-19 remains for more than 10 min at the same time and space (800 meters by 800 meters). If the calculated stay time of either party’s phone number exceeds 30 h in the last 14 days, the phone number will be detected as the space–time companions’ number. The companions’ number will be marked as a yellow code, and the marked companions are required to get the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test twice in three days or get the PCR test every day during the quarantining period according to the local pandemic prevention requirements. The health code system has covered various items, and some statuses are updated by the information from the official report, while others are recorded by the users. However, the core part of the health code—the vaccine report, PCR test report, travel record, and communication travel record—have a decisive indication for judging the health code status. This system is designed as part of a public health solution.

Conflicts between a hierarchical network and a co-acting network

The health code should be re-examined from an ethical standpoint in light of the fact that the campaign for the prevention of pandemics has generated several issues involving personal acts and individuals. This emerges in the conflicts that occur between the public and public management. In most regions of China, the application has aided in the management of close-off areas. In 2022 alone, 31 major cities, including seven provinces, were completely or partially sealed. In that year, Shanghai was quarantined from 27 March to 31 May as part of a notable pandemic prevention campaign; however, Shanghai is not the only major city with a large population that has been subjected to stringent and lengthy quarantine restrictions in China. During this campaign, citizens were marked with a health code wherever they went and whenever they visited any location, and the code was also used to record the status of their PCR testing. During years of pandemic prevention, citizens have become accustomed to passively adhering to the health code and related policies for a considerable period. However, the widespread use of the health code and strict measures for preventing pandemics have raised several concerns regarding the real economy, unemployment, travel restrictions, food and daily necessities supply, and the availability of public healthcare resources.

However, it is difficult to anticipate its potential long-term effects. Initially, the code was intended as a digital tool for use by the citizens, but it has predictably evolved into a digitalized management system. The fundamental principle of the health code is that individuals can be identified, tracked, and selected. This sequence of actions enhances the operational effectiveness and executive capacity of pandemics prevention, but it also shattered the equilibrium between individuals and public management.

The antagonistic and complementary relationships

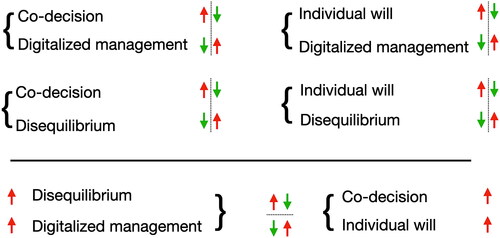

Observing the health code case at the macro level reveals that its underlying structure is a hierarchical network in which the core value of the system works for a particular policy or set of policies related to management rather than for regular users. In other words, the health code facilitates the management and encourages the decision-making side to expand the digitalized management, which could hinder free communication between actors. Throughout the duration of the pandemic, the application of health codes has been guided by particular policies. Individual users’ decisions regarding whether they ‘want to use it’ or ‘don’t want to use it’ are unclear, and citizens are forced into the role of regular actors who no longer have a choice while being involved in a process of social change that has a highly standardized digital tool and clear rules. In this regard, a contradiction between co-acting and hierarchical networks is assumed. Even with the advent of digitalization, hierarchical networks continue to play a vital role in the functioning logic of digitalized tools, especially when those technologies are tied to certain policies. The dynamic effect maintains a bi-directional balance among hierarchical networks, disequilibrium, and digitalized management. This coupling effect is exacerbated by the strengthening of digitalized management, which will exacerbate the disequilibrium between individuals and digitalized management. In addition, they are also direct and required prerequisites for reinforcing an inflating hierarchical network. The four factors are defined below.

Co-decision refers to the coordination mechanisms for collaborative rulemaking and decision-making between individuals and digitalized tools.

Individual will means that individuals are free to participate, use, and collaborate according to their own volition.

Digitalized management encompasses management models that are built and operated using digitalized tools.

Disequilibrium connotes inequality in decision-making rights and uneven autonomy between individuals and digitalized management.

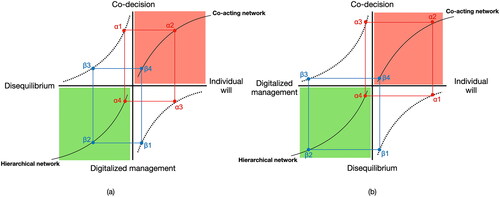

depicts four antagonistic groups, namely, co-decision and digitalized management, co-decision and disequilibrium, the individual will and disequilibrium, and the individual will and digitalized management, as well as two positively correlated groups, namely, co-decision and the individual will, and disequilibrium and digitalized management. These are separated into two sets of four-quadrant charts in the subsequent graph. When considering from an ethical standpoint the effect of the health code in social design, the individual will can be a hidden issue that is avoided. At the social level, individuals are required to adhere to the new normal restrictions and policies, which has resulted in a massive and silent actor, who must act and translate according to certain rules rather than their own will or decisions. In two positively correlated groups, the individual will and co-decision support the co-acting network, which asks individuals for more space and discourse power to co-participate in the operating process and decision-making phase; the co-acting network aims at balancing the equilibrium between normal users and digitalized tools. In the process of reviewing the health code, the conflict that could arise between normal citizens and policies came to light. The study posits that the individual will should be divided into two fundamental directions: an acceptable and an unacceptable range. Moreover, co-decision procedures with optional and negotiable rules for conflict resolution are required. For example, when the health code gathered vast quantities of social resources and made them act as a single polymer when confronting an individual, the conflict between them intensified. A highly centralized hierarchical network, including certain services, information system, specific policies, and unequal decision-making roles, has contributed to the imbalance between individuals and public management. Thus, the co-decision of a co-acting network is an opposing concept that aims to disperse the composition of the decision-making body, thereby increasing co-participant autonomy and decision-making management.

The confrontation and tension between hierarchical and co-acting networks

Co-acting network and hierarchical network regions each have their own components that are connected and intertwined with one another as well as the dynamic evolution of networks. The hypothetical points in illustrate the interconnected relationship between co-decision, digitalized management, individual will, and disequilibrium. The figure shows that in quadrant (a), if the co-decision is at a higher position (α1), it will increase the degree of the co-acting network (α2), which will increase the high level of the individual will (α3), thereby decreasing the level of the hierarchical network (α4). Similarly, a high level of digitalized management at β1 might result in a high degree of hierarchical network (β2) and a high level of disequilibrium (β3), resulting in a decrease in the co-acting network degree (β4), based on the mutual exclusion of co-decision and disequilibrium, as well as individual will and digitalized management. The confrontations and tensions between co-decision and disequilibrium, or the individual will and digitalized management will have the ability to change the degree of a co-acting network or a hierarchical network; this degree, in turn, can strengthen the level of their associated circumstances in their respective regions.

In quadrant (b), the same tensions exist between co-decision and digitalized management, the individual will and disequilibrium, and how they influence the evolution level of a co-acting network and a hierarchical network. A high level of the individual will (α1) promotes the emergence of a co-acting network, leading to a larger and more accessible co-decision circle (α3) and a permanently weakened hierarchical network (α4). Nonetheless, if the disequilibrium (β1) is bolstered by digitalized tools and highly centralized policies, it will be able to deepen the degree of a hierarchical network (β2) and make additional attempts to increase digitalized management (β3) from every angle, which will inevitably and persistently reduce the potential space of co-acting networks (β4).

The impasse that exists in the real world between co-acting and hierarchical networks can be broken down into a variety of social contexts and situations. This is contingent on how social designers decide the purpose of the design and its potential future repercussions, as well as how they evaluate the relations between human and non-human actors. It is challenging to predict the actual and potential effects of a social design that employs digitalized tools within a particular social context. The primary objective of design should be to guide people back to the fundamental meaning of society and the public. The ultimate objective of the design process should be to find public-centred solutions to public problems. Individuals should be accorded a greater significance in social design. Reviewing the health code issue reveals that social design should seek to uncover and survey the underlying intention of these novel functions or service content, as opposed to focusing solely on commercial success or a specific public issue that primarily serves economic and political objectives.

Reconsidering the use of digitalized tools within a co-acting network

The discussion regarding a co-acting network is based on ANT’s logic, and points out that the connections between things and actors help trace the primary purpose of actions and the essential value of the design context. Actors represent the status between the subject and object, which can be transferred from hierarchical connection to co-acting situations. According to the heterogeneous participants and the changing usage intentions, the border around the subject and object is weakened among actors and actions. When focusing on the purpose of activities and the context of acts, the co-acting network identifies the relations among all participants involved in the participation processes. Compared with a hierarchical network, a co-acting network scenario aims at finding a new direction by focusing on the intention and essence of the connections among all participants. This can be explored in both the online and offline worlds. It is not only a physical connection but also a link closely married to the social context, whether a material entity or a digitalized environment.

The connections lie in a spectrum of continuity and change. The social context, service content, and relative acts affect the status of all participants. In the health code case, despite monitoring of the spread of the virus in a networking supervisor pattern through big data, the health code has improved the stakeholders’ agility in assessing the current situation. However, the logic of the operation still did not eliminate the hierarchical network when considering the platform as a black box. All participants built the initial network by co-participating in the work, but the final effect of the service did not seem to interact with all actors equally. As a public health service tool, the security concerns regarding the programme’s usage should be considered more carefully.

With the development of an intelligent society, the trend between digitalized tools and the social context is moving from isolation to co-action, and non-human participants seem to acquire a more influential voice. However, it is doubtful whether such a social order will provide an equal access to the new connections emerging in societies. Enhancing the individual will and the degree of co-decision from multiple actors is essential for assessing the value of digitalized tools used in social design programmes.

Discussion

According to ANT scholars, three philosophical concerns explain the relations between actors. All entities, whether social, natural, or technological, are relational in character, and they derive their nature from these relations. The actor–network metaphor describes the relationships between these entities. Heterogeneous networks are composed of human and non-human actors working in associations, and the networks are brought together through translations (Ballantyne Citation2015). In the health code case, the whole system feeds on individual data as the primary platform for operation. Evidently, the government is the powerful operator behind the venue, but the connections are based on each entity in society. Interaction occurs during each behaviour, which shows the cooperative nature of the actors’ action in these connections.

Considering that the character of social entities is more significant in immaterial and intangible parts, digitalized tools can affect the social design process and method used to redefine social issues related to the conflict between individuals and public management. However, these creative ideas and devices have a bidirectional impact; they can be used to remodel social connections as new social problems emerge, which can also be deemed a practical method for affecting social entities en masse. As Bjögvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren (Citation2012) stated, a design could be viewed as a continuous rather than a finished process, inviting participation from users around an open procedure. When analysing a design process that incorporates digitalized tools from a social design perspective, it is crucial to assess the tensions that emerge as a result of conflicting elements. To understand fully the context of social issues, it is necessary to trace them back to the individual level. Furthermore, it is essential to clarify that the primary purpose of social design is to benefit individuals; hence, it should not focus solely on macro-level management strategies.

In any action process, the actors’ status and meaning are constantly changed by the relationships in those alternating connections. Some researchers tend to point out the social responsibilities of design for changing the status and describe an approach directed at marginalized or disempowered social groups in the design process (Bjögvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren Citation2012; Lupton Citation2018). In using ANT, the study seeks a perspective for revisiting the new relationship forged by potent digitalization and investigates whether it is possible to demand a co-acting network that reduces the imbalance between the public and public management that digitalized tools have caused. An investigation of the conflict between hierarchical and co-acting networks, including groups with antagonistic and positively correlated factors, is a probable approach to assess the boundaries of digitalized tools in the context of social design. As a component of the feedback, the conflict may be a manifestation of tension between digitalized management and the public, further offering dynamic control groups. In a social design reliant on digitalized tools, it can also be incorporated into the feedforward section to present the risk point and threshold of design. From the standpoint of social design, the four factors (co-decision, individual will, digitalized management, and disequilibrium) also have interactive and intertwined connections.

The transitional state of the actors may help justify the changing purpose of actions (i.e. the various connections that add to the pluralistic meanings of activities). An action leads to a result, which is also related to another activity, particularly when observing the dynamics of information and the various policies in the health code. No longer straightforward service platforms, big data, information management, and related policies can be re-identified as efficient digitalized tools for modern community management. However, designers and users must also be on guard against a highly digitalized management dominating the design process that might be used in the social design process. Although digitalized tools have positive and negative aspects, they should not be used as a unidirectional method for setting management system standards in most social entities.

Conclusion

The knowledge of how users continuously interact and connect with the non-human environment sheds light on how the development of technology has given the physical and virtual worlds more coordination, participation, and decision-making power. ANT presents an open-ended perspective for observing the social entities within which people live, as social issues become more complex and unpredictable. This study provides insights into how users continuously interact and connect with the non-human environment. Human societies are served by the products and services they create. Nevertheless, the public does not have the absolute decision-making power to determine new rules and frameworks, which indicates a bidirectional effect between human and non-human actors.

This study is limited in that it focused on a single health code case to observe the new connections that emerge in a mixed physical and virtual social space. The health code is a typical and specific case for researching the conflict between two different networks. However, the single case study used here lacks reference groups; as such, more samples are needed to verify the hypothetical conflicts. Moreover, the emergence of conflicts can be influenced by many external environmental elements in diverse social and political contexts. Therefore, the study context and area should be broadened, and the conflicts between hierarchical and co-acting networks need to be examined in a more flexible manner and under more diverse conditions. Nonetheless, this study presents an entry point that connects ANT with social design and inspires social designers to think about the conflict between individuals’ right and digitalized management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wenjin Wei

Dr. Wenjin Wei holds the position of lecturer in the field of Product Design Studies at North Minzu University, located in China. The individual possesses a Bachelor of Engineering degree in Furniture Design from Nanjing Forestry University, China, as well as a Master’s and a Doctorate degree in Design with a specialisation in Industrial Design from Chung-Ang University, South Korea. The primary topics of her research encompass UX design and Posthumanism design thinking.

Notes

1 The context is quoted from ‘China Newsweek’, https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1722882921654220236&wfr=spider&for=pc

2 China News, http://www.chinanews.com/gn/2020/04-28/9170116.shtml

3 Quoted from National Health and Family Planning Commission (Citation2020, No. 22). http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-12/10/content_5568777.htm

References

- Ballantyne, Neil. 2015. “Human Service Technology and the Theory of the Actor Network.” Journal of Technology in Human Services 33 (1): 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2014.998567

- Bjögvinsson, Erling, Pelle Ehn, and Per-Anders Hillgren. 2012. “Design Things and Design Thinking: Contemporary Participatory Design Challenges.” Design Issues 28 (3): 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00165

- Buwert, P. 2017. “Potentiality: The Ethical Foundation of Design.” The Design Journal 20 (sup1): S4459–S4467. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352942

- Chick, Anne. 2012. “Design for Social Innovation: Emerging Principles and Approaches.” Iridescent 2 (1): 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/19235003.2012.11428505

- Conole, Gràinne. 2009. “The Role of Mediating Artefacts in Learning Design.” In Handbook of Research on Learning Design and Learning Objects: Issues, Applications and Technologies, edited by Lorie Lockyer, Sue Bennett, Shirley Agostinho, and Barry Harper, 188–208. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

- DiSalvo, Carl, and J. Lukens. 2011. “Nonanthropocentrism and the Nonhuman in Design: Possibilities for Design New Forms of Engagement with and through Technology.” In From Social Butterfly to Engaged Citizen: Urban Informatics, Social Media, Ubiquitous Computing, and Mobile Technology to Support Citizen Engagement, edited by Marcus Foth, Laura Folano, Christine Satchell, and Martin Gibbs, 421–436. London: The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8744.003.0034

- Ely, Philip. 2020. “Designing Futures for an Age of Differentialism.” Design and Culture 12 (3): 265–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2020.1810907

- Gürdere Akdur, Selin, and Harun Kaygan. 2019. “Social Design in Turkey through a Survey of Design Media: Projects, Objectives, Participation Approaches.” The Design Journal 22 (1): 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2018.1560592

- Halsall, Francis. 2016. “Actor-Network Aesthetics: The Conceptual Rhymes of Bruno Latour and Contemporary Art.” New Literary History 47 (2–3): 439–461. https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2016.0022

- Janzer, Cinnamon L., and Lauren S. Weinstein. 2014. “Social Design and Neocolonialism.” Design and Culture 6 (3): 327–343. https://doi.org/10.2752/175613114X14105155617429

- Kefi, Hajer, and Jessie Pallud. 2011. “The Role of Technologies in Cultural Mediation in Museums: An Actor-Network Theory View Applied in France.” Museum Management and Curatorship 26 (3): 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2011.585803

- Kim, Hwan-Suk. 2017. Posthumanism and the Transformation of Civilization: Is a New Human Being Possible? 포스트 휴머니즘과 문명의 전화 새로운 인간은 가능한가? Gwangju, South Korean: GIST Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 1987. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 1991. Nous N'avons Jamais Été Modernes: Essaid’anthropologie Symetrique. Paris: La Decouverte.

- Latour, Bruno. 1996. “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications.” Soziale Welt 4: 369–381.

- Latour, Bruno. 1999. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- López, Verónica, Vicente Sisto, Enrique Baleriola, Antonio García, Claudia Carrasco, Carmen Gloria Núñez, and René Valdés. 2021. “A Struggle for Translation: An Actor-Network Analysis of Chilean School Violence and School Climate Policies.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 49 (1): 164–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143219880328

- Lupton, Deborah. 2018. “Towards Design Sociology.” Sociology Compass 12 (1): e12546. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12546

- Michael, Mike. 2017. Actor-Network Theory: Trials, Trails and Translations. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- National Health and Family Planning Commission. 2020. No. 22. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-12/10/content_5568777.htm

- Rice, Louis. 2018. “Nonhumans in Participatory Design.” CoDesign 14 (3): 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1316409

- Rydin, Yvonne, and Laura Tate. 2016. Actor Networks of Planning: Exploring the Influence of Actor Network Theory. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Walsham, G. 1997. “Actor-Network Theory and is Research: Current Status and Future Prospects.” In Information Systems and Qualitative Research, edited by Allen S. Lee, Jonathan Liebenau, and Janice I. DeGross, 466–480. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Wynn, Thomas. 2002. “Tools and Tool Behavior.” In Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Tim Ingold, 133–161. London: Routledge.

- Yaneva, Albena. 2009. “Making the Social Hold: Towards an Actor-Network Theory of Design.” Design and Culture 1 (3): 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2009.11643291