ABSTRACT

With a hundred years (1912–2012) of Norwegian master’s and doctoral theses written within the field of music as a backdrop, this article reports from an extensive study of the academisation of popular music in higher music education and research in Norway. Theoretically, the study builds on the sociology of culture and education in the tradition of Bourdieu and some of his successors, and its methodological design is that of a comprehensive survey of the entire corpus of academic theses produced within the Norwegian music field. On this basis, the authors examine what forms of popular music have been included and excluded respectively, how this aesthetic and cultural expansion has found its legitimate scholarly expression, and which structural forces seem to govern the processes of academisation of popular music in the Norwegian context. The results show that popular music to a large extent has been successfully academised, but also that this process has led to some limitations of academic openness as well as the emergence of new power hierarchies.

Introduction: the Nordic context and popular music in education

Within the worldwide realm of music education practice and research, the Nordic countries have long featured and been praised as sites for open-minded inclusion of popular music into almost every type and level of formal music education. As such, the practices of these countries have preceded much of the discussion on popular music in education (and its related research) that we find today, on a global level, and they have been developed partly prior to, but also in dialogue with, internationally acclaimed works on popular music and music education, such as those of Green (Citation2002, Citation2008).

According to Karlsen and Väkevä (Citation2012, vii), popular music ‘has been part of Nordic compulsory school music curricula for at least 30 years’; however it might be more accurate to say that, with respect to the actual practices of music teachers, such musics were vividly present in the Nordic classrooms already in the 1970s. In 1971, a music teacher programme embracing genres and styles such as jazz, folk music, pop and rock was established in Gothenburg, Sweden (Olsson Citation1993) and from then on, popular music of various kinds has, in increasing fashion, made its way into higher music education as a whole.

The early inclusion of popular music into Nordic music education practice also entailed an early academisation of the topic as such. In other words, alongside its inclusion into curricula and study programmes an interest arose within the Nordic music academia in studying such music and its related processes of socialisation and learning, and hence it became a topic of academic debate. Consequently, Nordic music scholars were some of the first to elicit research-based understandings of the acquisition of knowledge and skills among popular musicians (Berkaak and Ruud Citation1994; Fornäs, Lindberg, and Sernhede Citation1995; Lilliestam Citation1995; Johansson Citation2002), and also early in discussing the implications of such understandings for the practices of music education (Gullberg Citation2002; Väkevä Citation2006; Westerlund Citation2006).

Nowadays, instead of mainly pursuing exploratory, if not celebratory, inquiries into the informal learnings of various kinds of popular musicians, many of the Nordic music education scholars perform critical investigations into the consequences of popular music having held an almost hegemonic position within compulsory school music education for the last few decades. Georgii-Hemming and Westvall (Citation2010) point, among other things, to the fact that the large emphasis on popular music in Swedish compulsory school music education has limited both its repertoire, its content and its teaching methods. They also note that the practice of (mostly) taking the students’ personal musical interests as a point of departure for teaching might work to further marginalise minority or socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, since their access to other forms of music hence becomes sparse. Furthermore, Björck (Citation2011), Kamsvåg (Citation2011) and Onsrud (Citation2013) discuss the gendered implications of school popular music in Sweden and Norway with respect to, for example, the limited access of girls to any other role than that of lead singer or dancer, the unfortunate gender stereotyping often found in (and adapted from) certain popular music styles, and the ‘sexualized femininities’ (Björck Citation2011, 183) implicated in music videos, and which can constitute a problem both for the girls performing in and for the teachers being responsible for facilitating the music lessons. Other critical angles include Dyndahl and Nielsen’s (Citation2014) reflections on the shifting authenticities in Scandinavian music education, from, among other things, valuing formally acquired musical knowledge and skills to celebrating and rewarding ‘students’ autonomy’ (109) and even considering ‘[the] corresponding lack of teacher control as positive criteria for the evaluation of a good result’ (109; see also Zandén Citation2010). Kallio (Citation2015), on the other hand, is concerned with Finnish compulsory school music teachers’ popular repertoire selection processes in a school and curricular context where ‘all musics’ are seemingly welcomed, and where ‘teachers … are afforded considerable freedoms in selecting popular repertoire’ (195). Building largely on a sociological theoretical framework, she aims to construct what she terms ‘the school censorship frame (195), in other words mapping the societal forces that frame and “influence teachers” decisions to include or exclude popular musics’ (197).

This article belongs to the above body of works, looking into the Nordic ways of including popular music in music education through critical lenses. As such, our research, conducted under the larger project of Musical gentrification and socio-cultural diversities,Footnote1 builds on the underlying hypothesis that, although open-mindedness and an apparently endless freedom of choice exist when it comes to allowing popular music into formal education, there will still be regulating forces making some choices of repertoire or styles more legitimate than others. With this as a point of departure, we set out to explore the processes of academisation and institutionalisation of popular music in higher music education in Norway.

According to Tønsberg (Citation2013, 16), the first higher music education programme in Norway specifically directed towards other genres than Western classical music – in this case jazz – was established in Trondheim in 1979. However, already a few years earlier, popular music had started to ‘seep into’ Norwegian higher music education through particular courses which mirrored the interests of certain teachers, and through students’ own efforts, a few even choosing popular music-related topics for their academic theses (see more about this later on). From this point on, the inclusion of popular music into higher music education in Norway has been increasing on an ever-steepening and ever-broadening path. In this article, we wish to explore this expansion on a structural level, from the theoretical point of view of cultural sociology focusing on the connections between music, taste and class (Bennett et al. Citation2009; Bourdieu [Citation1986] Citation2011) and highlighting patterns of (apparent) change through notions such as cultural omnivorousness (Peterson Citation1992; Peterson and Kern Citation1996) and musical gentrification (Dyndahl et al. Citation2014; Dyndahl Citation2015a). Having a specific interest in the hegemonic sides of the processes of popular music academisation and institutionalisation, we ask the following three research questions: What kinds of popular music styles have been included, as well as excluded, in the academisation of popular music in higher music education in Norway? How are the phenomena of cultural omnivorousness and musical gentrification visible in the written academic output of Norwegian music research? And, finally, which structural forces seem to govern the processes of musical gentrification in the Norwegian academic context?

Theoretical framework: musical taste, omnivorousness and gentrification

Focusing on the connections between music, taste and class, and thus building on Bourdieu’s ([Citation1986] Citation2011) notion of cultural capital, the concept of cultural omnivorousness demarcates between the tastes of the dominated and the dominating classes, and denotes the fact that preferring ‘the broad cultural variety’ (Dyndahl et al. Citation2014, 48) seems to be the new hegemonic form by which the tastes of the representatives of the middle-to-upper classes are constituted (Peterson Citation1992; Peterson and Kern Citation1996). Still, younger age might be an even more effective demographic variable than higher social class for determining a high level of omnivorousness (see Bennett et al. Citation2009, 92), and the omnivores – at least where music is concerned – may wish to concentrate their patterns of taste around ‘cognate musical forms’ (77). The latter describes a taste pattern which may include for example opera, classical music and jazz, in other words music without a direct musical genre kinship; nevertheless the preferred forms are still ‘genres [that] are quite close to each other in cultural space’ (89). Consequently, what keeps them together is that they possess similar cultural status in their respective fields, within the social space of lifestyles that unfolds hierarchies of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture. Although musical omnivores may, as mentioned, be found across social hierarchies, the elite group members still differentiate themselves from other classes by how they go about exercising their musical consumption. Their musical interests, now across a wider range of genres and styles than ever before, are often expressed through a certain knowledgeable and educated ‘limited enthusiasm’ (93), rather than through passionate connoisseurship.

In the larger project, of which the present research study constitutes one part, the concept of musical gentrification is applied to designate a specific form of field renewal. As discussed in Dyndahl et al. (Citation2014, 53; see also Dyndahl Citation2015a), the broader concept of ‘gentrification’ originates from urban studies, in which it is used to describe urban development and restoration, most notably of the form that involves middle class members appropriating areas and places of residence which traditionally have belonged to the working class. Transferring this concept to the field of music sociology, we understand musical gentrification, metaphorically, as a concept which ‘serves to illustrate and examine similar tendencies to the above in various socio-cultural fields of music’ (53). It is further defined ‘as complex processes with both inclusionary and exclusionary outcomes, by which musics, music practices and music cultures of relatively lower status are made to be objects of acquisition by subjects who inhabit higher or more powerful positions’ (54). Moreover, we claim the existence of intimate relations between musical gentrification and cultural omnivorousness, since ‘gentrification seems to provide necessary arenas or social fields for omnivorousness to be exercised’ (53). In other words, in order for the omnivores to be able to consume a rich cultural diet, the gentrification processes need to infuse new produce so that this diet can in fact be provided. If we move into the field of music education following this logic, it can for instance be claimed that music educators and researchers may have made certain forms of popular music objects of acquisition by institutionalisation and academisation, partly in order to exercise their own musical omnivorousness in new and distinguished ways through that same acquisition. Furthermore, just as institutionalisation and academisation may have impacted positively on the status of the acquired (and thereby preferred) forms of popular music, other kinds of popular music may have been excluded and omitted through the exact same processes.

In line with Bourdieusian theory, cultural capital finds its ‘institutionalized state, a form of objectification … in the case of educational qualifications’ (Bourdieu [Citation1986] Citation2011, 82). Hence, the appreciation of certain forms of popular music in higher music education and the exclusion of others may constitute forms of social closure in this particular social field, and regulate the access to acquiring particular forms of formal qualifications or certified forms of cultural competencies. In a recent empirical study of the social classes and elite groups in Norway, Hansen et al. (Citation2014, 35) argue that professors and other university academic employees effectively influence not only what are legitimate research objects or legitimate educational content, but also who and what should be admitted to high positions outside of academia. As such, they claim that professors, in particular, represent a kind of cultural academic elite which exerts the power to define and introduce new arenas and objects of interest within their own fields – in academia and beyond. Within the arts, this professorial power of definition might work to be even stronger. For example, Hovden and Knapskog (Citation2014, 56) claim that being a renowned arts professor implies that one is ‘clearly better placed than others to influence what types of art and which artistic artefacts are acknowledged (or at least presented) as valuable … that is, to be cultural tastemakers and gatekeepers, tastekeepers’. With respect to music academia and higher music education, this means that music professors may act as regulating forces with regards to how musical omnivorousness is enacted in legitimate ways within their field and to which musical genres and styles are considered appropriate to elevate and institutionalise through processes of musical gentrification (see Dyndahl Citation2015b).

As mentioned in the introduction already, another structural dimension which may affect the uptake of popular music into (higher) music education, is gender. According to Bourdieu (Citation2001, 94f) masculine domination is normalised in the social space of lifestyles, and thus, social order in this space is always gendered. This equally applies to the educational field, where female students, to a lesser degree than their male peers, can expect their teachers and supervisors to encourage them to choose subjects and career paths that are considered masculine (94f). This gendered division between subjects and career paths is rooted in a struggle against feminisation of professions, and is upheld despite the fact that an increasing number of women nowadays occupy elite positions within academia.

Methodological approaches: from material to data

As discussed above, the concepts of cultural omnivorousness and musical gentrification seem to hold potential for understanding the generic and stylistic expansion that has been witnessed in Nordic music academies, conservatoires and university schools of music, and through which various musical cultures have reached a new level of academic legitimacy and status. Accordingly, in order to explore the research questions outlined above, we have engaged in an extensive and historical survey of the entire corpus of academic theses written within the field of music in Norway; that is, all master’s and doctoral theses produced within programmes of musicology, ethnomusicology, music education, music therapy, music technology, music performance and their respective subdivisions, at ten music conservatoires, universities and university colleges.Footnote2 The survey spans 100 years; from 1912, when the first thesis appeared, and until 2012, when we stopped counting.

All theses were catalogued and categorised according to a set of categories, including year of publication, the institution in which the work was written, type of thesis, study programme affiliation, author name, supervisor name, author and supervisor gender, the musical genres and styles involved, scientific discipline, and, where relevant, the arena of investigation with respect to formal and informal contexts for education and/or learning. All four authors (Dyndahl, Karlsen, Nielsen and Skårberg) contributed to the compilation of the theses, and the categorisation of each thesis was discussed among the research group members. Eventually, the data were coded into the statistical package of SPSS for descriptive analysis.

The categorisation that required the greatest effort and demanded the most attention was arguably that of musical genre, and, further specified, that of identifying and labelling the various popular music styles involved. Hence, in the next section, we will give a detailed account of this particular work, since the popular music categorisation is the one with the most substantial relevance to the topic of this article.

Principles of popular music categorisation

With respect to the categorisation of musical genres in general, Bennett et al. (Citation2009) make an interesting methodological observation, criticising many quantitative studies for employing too few indicators of musical genre or taste. They also claim that the trend has been that ‘high culture’ and Western classical music have been treated with more nuanced categories than popular culture:

This was certainly true of Bourdieu’s own analysis of music, which centered on differences within the broad field of classical music: Strauss’s Blue Danube is popular among the working class, whilst the Well-Tempered Clavier is favoured by intellectuals (Bourdieu 1984, 17), yet both are part of the classical music canon. This general bias remains true for the studies of Sintas and Álvarez (Citation2002), and DiMaggio and Mukhtar (Citation2002), as well as Chan and Goldthorpe (Citation2006 [sic.]). There is a wider methodological issue here. Those who study popular music generally use qualitative and ethnographic approaches (e.g. Martin Citation1995; Longhurst Citation2000 [sic.]; Cohen Citation2007) often strongly informed by cultural studies, whilst those who study classical music are more likely to use quantitative data, focused historical studies and more ‘orthodox’ social theory. We badly need to bridge the divide if we are to understand the relationships between musical tastes more comprehensively. (Bennett et al. Citation2009, 77)

Without having any ambition to cater to all the issues raised in this quotation, in our attempt to bridge a certain gap we have at least tried to cover as wide a range as possible of subgenres and styles in popular music within a predominantly quantitative research design. In this way we have also attempted to contribute to a refining of the concept of musical omnivorousness by using it to reveal distinctions within popular music rather than between the popular and other cultural sets of values.

Still, it may be difficult to make a clear-cut distinction between musical genres and styles. In academic literature there is a widespread notion that musical genre is a more broad classification than style. Thus genre normally refers to a shared tradition or set of conventions, which does not prevent genres from overlapping, and genre classifications are often subjective and controversial. Moreover, even if genre distinctions may be taken for granted in everyday life, in cultural policy and in music education – for example in terms of what Tagg (Citation1982) labels an ‘axiomatic triangle’ consisting of ‘art’, ‘traditional’ and ‘popular’ musics – their blurred nature has often been criticised by musicologists (Middleton Citation1990) and also by musicians. For example, in our efforts to create a wide, inclusive variety of subgenres and styles that should be appropriate for the analysis of musical gentrification (see below), we have included jazz into an overall popular music genre. We notice that this has aroused negative reactions from jazz musicians and connoisseurs in our immediate surroundings, and we also take into account DeVeaux’s (Citation1999, 418) observations that it has been important for jazz not to be associated with popular music in general, in order to be framed as ‘an autonomous art of some substance’. Still, for the purposes of our research topic – academisation of popular music in higher music education – jazz in various forms has been categorised under the popular music label.

Regarding musical style, Stefani (Citation1987, 13) defines this concept as follows: ‘“Style” is a blend of technical features, a way of forming objects or events; but it is at the same time a trace in music of agents and processes and contexts of production.’ Consequently, a musical style partly consists of musical components (sound, rhythmic and form patterns, etc.), while at the same time it is inevitably introduced into a larger dialogue community which seeks to place the style within an overarching genre community. A starting point for framing a particular musical style will thus be to focus on the musical information. According to Bateson’s (Citation1979, 99) famous dictum, ‘information consists of differences that make a difference’. Furthermore, Moore (Citation2003, 6) argues that when dealing with complex formats, such as music, one must add interpretation to the formal provision of information. In doing so, he relates to the concept of musical pertinence when reflecting upon social and realistic determinations of style and genre communities in popular music. Moreover, Middleton (Citation2000) argues for a ‘participatory listening’ where the objective is not to confirm a particular schematic and music structural setup, but rather to keep an open ear for those aspects of the music that emerges as significant, or as pertinent. The key question is: ‘which gestures are in play, or are predominant, at any given moment?’ (108).

Hence, as Walser (Citation1993, 4) reminds us, genre and style communities are always constructed as discursive formations, formed, maintained and transformed through dialogues: ‘genre boundaries are not solid or clear; they are conceptual sites of struggles over the meanings and prestige of social signs’. Furthermore, ‘the details of a genre and its very presence or absence among various social groups can reveal much about the constitutive features of a society’ (29). An important methodological question for the research group when categorising the substantial material of the present study has therefore been to constantly ask each other what we consider to be musically, as well as culturally and sociologically relevant when dividing the actual music into established genre and style categories. In addition, there is a historical dimension to our project, which might imply that the designation of genres and styles has changed over the years. This invokes the need to find a productive balance between the actual terms used at the time and broader concepts that allow for a contemporary approach and analysis.

With the above considerations in mind, we have ended up using the following set of subgenre and style categories for the analysis and discussion of popular music and jazz: early jazz; mainstream jazz; modern/contemporary jazz; Tin Pan Alley/musical; traditional and cabaret songs; folk/singer-songwriter; country music; Scandinavian dance band music; blues; rock and roll; rock; hard rock/prog rock; punk rock; heavy metal/black metal; pop; alternative pop/rock; funk; hip-hop; contemporary R&B; electronic dance music; world music; ‘rhythmic music’ and a residual category, designated as miscellaneous. The categories will to the extent needed be clarified and specified in the sections below.

The findings: academisation, omnivorousness and gentrification in Norwegian higher music education

The broader picture

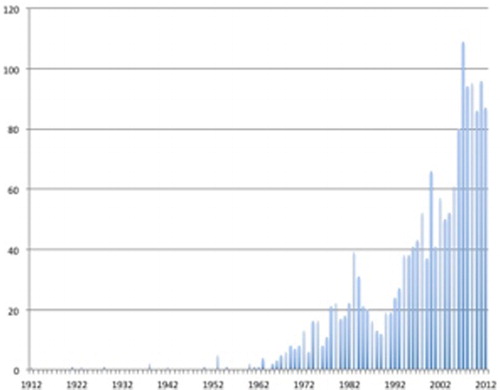

First of all, the total number of theses turned out to be much larger than we expected. In all 1695 works were detected – quite a large number in our view, considering that ‘music’ constitutes a modest-sized academic field and that our research is conducted within the context of a rather small country.Footnote3 The graphic overview (see ) of the distribution of theses throughout the 100 years of investigation shows that the production was sparse and theses appeared in a scattered manner until 1965. However, from this year on, the production has been stable and also steadily increasing, despite a slight dip in the latter part of the 1980s. The hitherto uncontested peak of an annual production of 109 theses happened in 2007,Footnote4 and in the years following this peak a yearly outcome of approximately 90 theses seems to be the rule. This rather steep increase in number of works can be said to mirror the Norwegian so-called ‘educational explosion’ (Thune et al. Citation2012; Ahola et al. Citation2014) by which free higher education was made available to a large proportion of the population in the decades following World War II, and it represents evidence that this phenomenon also found its way into the arts and humanities disciplines, and to music academia. As such, of all the theses produced during the 100-year period of investigation, a vast majority – 1603 – belong to the master’s level or second cycle of higher education, while 92 were written on the third-cycle doctoral level. Indeed, for many decades the master’s-level works constituted the research contribution to Norwegian music academia, and doctoral theses would, until 1995, only appear once in a while.Footnote5

The introduction of popular music

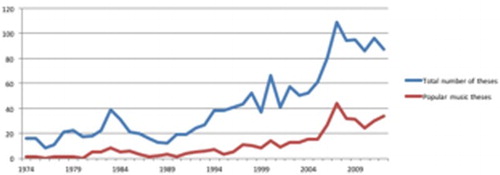

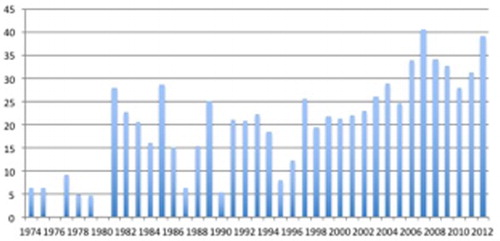

The introduction of popular music to Norwegian music academia happened already in 1974, with a work on modern/contemporary jazz written within the musicology programme at the University of Oslo. Since then, there has been a steady increase in theses treating various popular music styles in a manner that, by and large, follows the curve of total number of works written per year (see ). Even the 2007 peak can be found, with 44 works written on popular music that specific year. In the years following this peak, the annual number seems to have stabilised itself on approximately 30 theses. Already quite early on, the popular music theses occupied a considerable amount of the academia ‘market shares’, constituting about 20% of the total amount since 1981 (see ). The first time the percentage rose above 30 was in 2006, which seems to have established a new ‘level’ that since then has more or less been the norm.

Three patterns of musical gentrification

Exploring the data statistically, we have been able to identify three different patterns of musical gentrification which will be explained below. The first pattern concerns the general uptake of popular music to the field of music academia in Norway and the broader picture associated with what kinds of musics are included or excluded, how these musics are treated academically, what role gender plays when popular music makes its academic entrance, and who seems to possess the power to influence the inclusion of styles, either personally, by virtue of occupying the position of supervisor or tastekeeper, or on the institutional level. While the broader picture of popular music entrance and proportion in relation to other musics has been presented above, the remaining aspects of this first gentrification pattern will be elaborated more in detail in the sections to come.

The second pattern of musical gentrification is visible mainly in the programmes of musicology, and concerns a ‘gentrification from within’ with respect to what kinds of topics and areas of investigation are perceived as relevant within this specific field of music academia. From a concern mainly with traditional historical and systematic musicology, beginning with the first doctoral thesis in 1912, dedicated to a documentation of the music used for liturgical celebration of St Olaf in what are now the Nordic countries, Norwegian musicology widened its scope from the early 1970s onwards, towards including topics that could perhaps most usefully be categorised under the umbrellas of music education and music therapy. A cross-tabulation of the categories of study programme affiliation and scientific discipline shows that of all the theses written within the Norwegian programmes of musicology – a total of 1107 works – 205 (18.5%) can be categorised, by choice of topic, as belonging to the field of music education and 25 (2.25%) to the field of music therapy. Adding the popular music that seeps into musicology already from 1974 (see above) as well as the ethnomusicologically oriented theses (77 theses – 7.0% – first thesis appearing in 1970) we get a picture of a field which slowly opens itself up towards other musics, music practices and music cultures than those stemming from the Western art music tradition, and implements these within an academic domain of relatively high status.

The third pattern of musical gentrification is most visibly manifested in the material stemming from the largest and most prestigious of the conservatoire institutions, namely the Norwegian Academy of Music. Until 2002, the performance studies of this institution were exclusively directed towards Western art music, although popular and folk musicians were allowed into the music education programme already in 1984. However, popular music was present in the academic output of this institution already from 1975, within a work written in a programme for applied music theory, and it continued to be present, mainly through the theses written within the music education and music therapy programmes. The total number of theses produced at the Norwegian Academy of Music is 296, and of these, 70 (23.6%) focus on popular music in one way or another. Altogether, 54 of these theses are written within the music education (33) and music therapy (21) programmes of this particular institution, which is to say that these programmes are responsible for 77.1% of the popular music output, and thereby for a considerable share of the popular music-related musical gentrification processes taking place within the largest conservatoire institution in Norway.

What kinds of popular music are included and excluded?

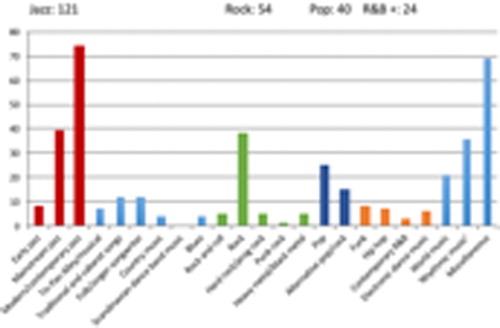

With respect to the entire national corpus of 1695 theses, the works focusing on popular music amount to 404 (23.8%). Looking further at how these latter theses are distributed when it comes to musical styles (see ), there seems to be a large interest in jazz – modern or contemporary jazz constituting the by far most academised styles – and little to no interest in styles such as country music, blues, rock and roll, punk rock, contemporary R&B and Scandinavian dance band music.Footnote6 As can be seen from , when grouping styles into somewhat larger categories, those that can be considered most successfully gentrified in the sense that they have entered Norwegian music academia through a rather large number of theses, are jazz (121), rock (54) and pop (40). In addition, the miscellaneous category amounts to 69 works, which mainly encompasses theses in which popular music is present as for example a more general part of youth culture or within music education or music therapy practices, but where it is not possible to identify any specific style. Likewise, the concept of ‘rhythmic music’ – a term which is in use mainly in Scandinavia – includes what can be described as a wide range of styles, including rock, jazz and improvisation-based music with elements of folk and world music, and which is regularly used in educational contexts. In our data this style is focused in 36 theses. Beat-based and contemporary styles such as funk, hip-hop, contemporary R&B and electronic dance music amount to only 24 theses when their individual numbers are combined. Striking is also the field’s complete lack of interest in Scandinavian dance band music, a style which has been dealt with within other disciplines, such as sociology, media studies and cultural studies,Footnote7 but which Norwegian music academia still seems to keep at arm’s length.

The various popular music styles enter the academic scene at different times (see ). A ‘base’ consisting of jazz, rock and pop music seems to have been established rather early, from around 1983 onwards. This is consistent with the findings reported above of these styles’ presence in a large number of theses and consequent status as most successfully gentrified up until 2012. World music is included in 1990, and hip-hop already in 1999 while, quite surprisingly, styles such as heavy or black metal, country music and punk rock are latecomers to the academic table, arriving first in 2005, 2010 and 2012 respectively. A related matter of interest, worth mentioning, is that, while many theses focusing on classical music might be theoretically quite straightforward in the sense that they belong to the well-established musicological genre of ‘the man and his work’, newcomer popular music styles are often surrounded by considerable theoretical efforts and splendour. For example, a thesis dedicated to country music and Dolly Parton utilises gender theory in quite sophisticated ways, and punk rock is wrapped up in feminist and performativity theory, perhaps in order to compensate for introducing styles and musicians that might be perceived as ‘illegitimate’ in the authors’ surrounding academic spheres.

Table 1. Year of popular music styles entering the academic scene.

Gentrification, popular music and gender

Overall, the gender balance in the investigated corpus is almost as equal as can be wished for. Of the 1695 theses, 866 (51.1%) are written solely by men and 827 (48.8%) by women.Footnote8 Perhaps not unexpectedly, the proportions change somewhat when only the 404 popular music theses are calculated in the same way. This particular part of the corpus is more dominated by male authors, men being responsible for 255 theses (63.1%) and women for 149 (36.9%). In addition, looking at how styles are distributed according to gender (see ), male authors heavily dominateFootnote9 more established, hardcore or avant-garde styles such as early, mainstream and contemporary jazz; blues, rock and roll, rock and hard rock/prog rock; and hip-hop, contemporary R&B and electronic dance music. Only three stylesFootnote10 are dominated by women in the same way, namely Tin Pan Alley/musical, folk/singer-songwriter as well as traditional and cabaret songs, and these can all perhaps be understood as belonging to the ‘softer’ side of the popular music chart. Although male authors are still mostly in a majority, the styles of country, heavy metal/black metal, alternative pop/rock, pop, funk/soul, world music and rhythmic music seem to constitute more of a gender neutral ground, as does the tendency to include popular music in a more general way (as acknowledged through the miscellaneous category).

Table 2. Popular music styles distributed according to author gender.

Another way to measure the impact of gender on processes of gentrification is to see who takes the opportunity – men or women – or who has (or is given) the courage to introduce a particular popular music style to Norwegian music academia for the first time. Going back to , where the styles were presented according to the year in which they first entered the scene, of all the styles introduced up until 2004 (a total of 15 styles), 13 were introduced by men and only three by women (mainstream jazz, world music and traditional and cabaret songs).Footnote11 From 2005, this picture changes noticeably. Of the six styles appearing from this year until 2012, five are introduced by women and only one by a male author (contemporary R&B). Why this sudden shift in ‘gendered academic courage’ suddenly occurs is hard to say based on our statistical material. Nevertheless, it is an interesting finding, showing possible ruptures and changes in structures related to musical gentrification and gendered domination and hegemony.

Despite the small signs of change reported above, the impression of a strong popular music gender imbalance is perpetuated when moving the focus towards who has supervised the theses in question. Of the 404 works, 331 (81.9%) are supervised by male professors and 49 (12.1%) by female ones,Footnote12 suggesting a considerable masculine domination also at this level of Norwegian music academia.Footnote13 Furthermore, male supervisors dominate almost all of the styles, except contemporary R&B and electronic dance music, and sometimes to a rather extreme degree. For example, 91.7% of the jazz-related works are supervised by men, as are all the works on country, blues, hard rock/prog rock, punk rock and heavy metal/black metal. The category which includes most female supervisions (16) is the miscellaneous one, suggesting that often, when women introduce popular music to the music academic field in Norway in the role of supervisors, it happens through its implicit (and rather tacit) inclusion in music education and music therapy practices.

The role of institutions and tastekeepers

Three institutions dominate the Norwegian music academia output in terms of number of theses written, namely the large musicology programmes at the University of Oslo (783 theses/46.2% of total amount) and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (346/20.4%) respectively, as well as the Norwegian Academy of MusicFootnote14 (296/17.5%). These same institutions also dominate the popular music academic field and processes of gentrification, however in slightly different ways. While the proportionate distribution of the total number of popular music-oriented theses written is not so different from above,Footnote15 there is a considerable difference between the two musicology programmes on the one side, and the conservatoire institution on the other, in terms of where, stylistically, their main contribution lies. The musicology programmes dominate almost all the popular music styles in terms of number of theses written, sometimes to such an extent that it is exclusively within one or both of these programmes that works about a particular style are produced. Even when counting in all the ten institutions covered, the latter is the situation for hard rock/prog rock, punk rock, contemporary R&B and electronic dance music. On the other hand, the Norwegian Academy of Music dominates the miscellaneous category, with 30 out of the total number of 69 theses placed there. Moreover, this amount constitutes a big share (42.9%) of this particular institution’s popular music-oriented theses, strengthening the hypothesis that music education and music therapy practices (and programmes) are the ones which contribute the most to musical gentrification in the conservatoire sphere.

Exploring the popular music styles’ points of entrance (see ) from the angle of institutions, the above picture of hegemony and dominance is maintained: Of all the 21 styles listed, the University of Oslo is responsible for 12 entrancesFootnote16 (modern/contemporary jazz; early jazz; Tin Pan Alley/musical; traditional and cabaret songs; rock; funk/soul; world music; folk/singer-songwriter; heavy metal/black metal; electronic dance music; contemporary R&B; and country), the Norwegian University of Science and Technology for seven (rock and roll; hard rock/prog rock; rock; pop; alternative rock/pop; hip-hop; and punk rock) and the Norwegian Academy of Music for three (mainstream jazz; rhythmic music; and blues).

So, are there no challenges to this pattern of institutional domination of processes of gentrification? Exploring the data further, a few smaller ruptures can be found: The music performance programmes at the University of Agder contribute 33 popular music theses (45.2% of the entire production of this university), and this institution is the only one outside of the above triad which dominates a popular music style category, namely the one of rhythmic music. Likewise, about half the theses (5 out of 11) written within the musicology programme at Nesna University College are focused on popular music. Still, the numbers of both institutions are too small to make a significant impact on the national level, and the range of popular music styles involved is also quite limited. Based on the above it is hence easy to conclude that three institutions lead the processes of musical gentrification in Norwegian music academia: The musicology programme at the University of Oslo, the musicology programme at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and the Norwegian Academy of Music. Of those three, the two former institutions are more avant-garde and musically wide-ranging than the latter, and might hence be understood as the key changemakers in an academic field that does not necessarily seem to move forward too fast.

Closing in on changemaking on the individual level, the role of supervisors as forerunners and tastekeepers appears to be crucial. A total of 70 professors have been involved in supervising popular music theses. This might point to a general openness towards such styles among Norwegian music academia faculty members. However, limiting the further exploration of this part of the data to the ones who have supervised 10 popular music theses or more, only 11 persons can be found, and these few combined are responsible for supervising 231 (57.2%) of the 404 theses. Not surprisingly in light of the above, of these 11 supervisors only one is female. Zooming further in, two men have supervised 43 and 50 popular music theses respectively, and they are employed at the musicology programmes at the University of Oslo and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. In other words, the power to influence broader processes of musical gentrification in Norwegian music academia in the role of supervisor is in just a few hands, and some of those hands have been extremely industrious and influential. There is reason to believe that the persons in question not only operate as supervisors but also to a large degree as the aforementioned tastekeepers, actively regulating who and what is allowed to enter the popular music field in academia, and possibly also beyond.

Discussion: the limitations of academic openness and the implications of power

Before entering a broader discussion of our findings, we will briefly explicate and reiterate the answers to our research questions, stated above: First, the kinds of popular music styles that have been most eagerly included in the academisation of popular music in higher music education in Norway are the broader and more established versions of jazz, rock and pop. Country music, blues, rock and roll, punk rock, contemporary R&B and Scandinavian dance band music are outliers that have been nearly or completely excluded. Second, the phenomena of cultural omnivorousness and musical gentrification are visible in at least three ways: through a gradual uptake of popular music across the field; through an increasing disciplinary breadth and opening towards including other musics, music practices and music cultures than those stemming from the Western art music tradition within musicology; and through music education and music therapy programmes wedging popular music into the conservatoire sphere. Third, the structural forces that govern processes of musical gentrification in the Norwegian academic context seem to be connected to gender, institutional status and the academic elite power ascribed to individual professors. These forces may work as separate entities, but are perhaps most powerfully operated in various combinations.

As mentioned above, Nordic formal music education has generally been much appraised for its openness towards including popular music at any level (Väkevä Citation2006; Westerlund Citation2006; Karlsen and Väkevä Citation2012). However, with respect to such inclusion in Norwegian higher music education and music academia, such openness seems to have its obvious limitations. Furthermore, inclusionary processes are sometimes excruciatingly slow, punk rock forming one example of a style using almost 40 years from the point of being established (mid-70s) until a thesis primarily devoted to this style appears in Norwegian music academia (in 2012). So, how can these patterns be understood through our theoretical framework? First, it is possible to interpret the rather well-included broader versions of jazz, rock and pop as cognate popular music forms (Bennett et al. Citation2009) which are – in this particular context – situated quite close to each other in cultural space and perceived as ‘high’ popular culture. The less successfully gentrified styles can similarly be viewed as perhaps either too closely associated with working class culture (e.g. country music, punk rock and Scandinavian dance band music, see Bennett et al. [Citation2009]; Stavrum [Citation2014]) or as offering insufficient opportunities for contemplating the music in a disinterested academic mode to be able to reach this elevated state. As such, the previously mentioned example of wrapping Dolly Parton up in gender theory may represent a mode of ‘limited enthusiasm’ (Bennett et al. Citation2009, 93) and hence more of a staging of educated elite taste than of actual working class culture being allowed to enter academia. An interesting question to ask in this respect is whether the processes of musical gentrification found within higher music education in Norway can be attributed to the children of the working class having increased access to such education through the post-World War II educational explosion (Thune et al. Citation2012; Ahola et al. Citation2014), or whether they originate from the pattern described by Peterson (Citation1992; Peterson and Kern Citation1996) of the dominating classes appropriating a broader cultural variety than before (Dyndahl et al. Citation2014). Our data do not answer this question exactly, but combining what we know about musical gentrification processes in surrounding society with what our data suggest, we can at least conclude that changes in musical taste patterns do not seem to start in music academia. Rather, for a popular music style to be considered interesting, academically, it must have reached a certain level of elevation in general society before it is allowed by the academic tastekeepers. In our opinion, this points to the dominating classes still having a strong hold on decisions concerning what musics are worthy of being academised and gentrified in Norway.

Furthermore, while the term gentrification originates from the word ‘gentry’, which denotes people of noble birth, it seems that the academisation of popular music in higher music education up to 2004 is a process that typically belongs to male academics – ‘the gents’, so to speak. This applies to students as well as supervisors, as men dominate the gentrification processes in number as well as when it comes to being the ones that introduce most new subgenres and styles to be academised. By this latter trend, the men not only reaffirm the masculine domination (Bourdieu Citation2001), they also accumulate their own cultural capital.Footnote17 However, starting around 2005 we can observe a new tendency. From now on, the majority of new styles are introduced by women. One might ask whether this happens because female academics have obtained more central positions in the field, or whether it means that the phenomenon of gentrification in general has been feminised and hence devalued. In any case, it is obvious that gentrification is gendered, but this particular genderfication of popular music in academia needs to be examined more thoroughly in order to further unpack its intersectional implications as well as the power structures that regulate the relationships between gender and social division.

With respect to power structures and gentrification, we have shown above that three institutions dominate the Norwegian music academia, not only in terms of numerical output, but also as concerns the inclusion of popular music in general as well as the initiation and driving of the gentrification processes relating to this particular music. As such, viewed through our theoretical lenses, these three universities and academies can be perceived as elite institutions, constituting the dominating or middle-to-upper ‘class’ (Peterson Citation1992; Peterson and Kern Citation1996) of music academia in Norway, actively creating conditions for the exhibition and execution of hegemonic cultural omnivorousness among their own staff and students. Among the three, the musicology programmes at the University of Oslo and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology are the ones who seem to possess the most elevated status of knowledgeability and ‘limited enthusiasm’ (Bennett et al. Citation2009, 93) in that they more frequently show tastekeeper agency and courage in lifting popular music styles from lowbrow positions to avant-garde status through acts of musical gentrification. The reason why the conservatoire institution among the three – the Norwegian Academy of Music – might not be so active in such endeavours can perhaps be linked to the idea that academic refinement, elevation or disinterest might be more easily obtained when the object of acquisition (or of potential gentrification) is not linked to actual musical performance – as it will often be within a music academy – but can be approached in literary ways mainly. Further explorations are needed to unpack the complexities of this area, too.

Closing this section, we will briefly discuss the ways in which our research may support further conceptual and theoretical development. In this regard, we believe we have contributed to refining the concept of cultural omnivorousness, mainly by employing it in order to discuss hierarchical distinctions within popular music, rather than between what has traditionally been understood as high and low culture. Furthermore, the notion of musical gentrification reinforces that these processes are simultaneously inclusive and exclusive. In addition, this concept highlights that the genres and styles gentrified may gain new – and in this case, academic – status. Hereby, it is also conceivable that gentrified music might lose status, for example in the sense that, in the eyes of its initial supporters, it may come to be seen as too ambitious or as assigned other meanings than those originally held. Moreover, while there are close connections between musical gentrification and cultural omnivorousness in that gentrification provides conditions for omnivorousness to be exercised, the conceptual pair also entails a supplementary division of responsibilities. While cultural omnivorousness appears as oriented towards individual and group agency in social formations, musical gentrification can be more usefully applied when investigating the institutional and structural aspects of historical, social and cultural processes pertinent to higher music education and music research (see also Dyndahl et al. Citation2014, 53f).

Concluding remarks: the importance of epistemic reflexivity

It is our sincere hope that a long-term effect of the research and results we have presented in this article would be an increase in self-reflection among music educators and researchers. Obviously, this also applies to ourselves. Regarding the group of researchers contributing to this article as authors, on a collective level we have been part of Norwegian higher music education since the late 1970s onwards. First as students, and then, at later stages, as professors in some of the institutions under scrutiny in this report. Striving to achieve self-reflection, we have aimed to implement what Bourdieu and Wacquant (Citation1992) call ‘epistemic reflexivity’, comprising reflections on unrecognised or misrecognised conditions that can influence or restrict our approach to the research project. On the one hand, our familiarity with the researched field ensures a privileged insight into its workings exactly during the period in which the gentrification of popular music has occurred and evolved. Thus, it facilitates our ability to detect and discuss music education and research as power-saturated social practices. As such, our collective experiences form an essential prerequisite for moulding and constructing the empirical material into data and knowledge. On the other hand, this situation also implies that we are facing a challenging test in terms of contributing distanced-enough self-reflections. Still, the indications of whether we have passed this test or not rest, in our opinion, less on proclamations claiming that we are freed from the habitual beliefs that exist in the field, and more on how the epistemic reflexivity is embedded in the research and dissemination practices in which we have partaken. Possibly, the reception of this article will show whether we have been up to par.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Petter Dyndahl is professor of musicology, music education and general education at Hedmark University of Applied Sciences, Norway, where he is head of the Ph.D. programme in teaching and teacher education. He has published research results in a wide range of disciplines, including music education, cultural studies, popular music studies, music technology and media pedagogy. Currently, he is project manager for the research project Musical gentrification and socio-cultural diversities, which is funded by The Research Council of Norway for the period 2013–2017: www.hihm.no/MG

Sidsel Karlsen is professor of music education and general education at Hedmark University of Applied Sciences in Norway as well as docent at the University of the Arts Helsinki in Finland. She has published widely in Scandinavian and international research journals and is a frequent contributor to international anthologies and handbooks. Her research interests cover, among other things, multicultural music education, the interplay between formal and informal arenas for learning and the social and cultural significance of music festivals.

Siw Graabræk Nielsen is professor of music education at the Norwegian Academy of Music, Oslo, where she has been Vice-rector of Research and Development and where she now is leader of the newly established Centre of Educational Research in Music (CERM). She has published research on the self-regulated learning of musicians, the professional knowledge of music teacher students, music education and authenticity and the ‘research-based’ teaching and learning in higher music education.

Odd Skårberg is music professor at Hedmark University of Applied Sciences. He defended in 2003 for a thesis on Norwegian rock in the 1950s. In his post doc. period, he investigated modern Norwegian jazz between 1960 and 1990. Professor Skårberg’s publications include substantial contributions to the understanding of Norwegian popular music history in Norges musikkhistorie [The history of Norwegian music] as well as chapters on jazz and popular music in Vestens musikkhistorie fra 1600 til vår tid [The history of Western music from 1600 to the present].

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This project is funded by the Research Council of Norway throughout the period 2013–2017 and run by the collaborative institutional partners Hedmark University of Applied Sciences and the Norwegian Academy of Music.

2 These institutions are, as listed in alphabetical order: Bergen University College; Hedmark University College; Nesna University College; NLA University College; the Norwegian Academy of Music; Norwegian University of Science and Technology; Statistics Norway 2015; UiT The Arctic University of Norway; University of Agder; University of Bergen and University of Oslo.

3 Norway had a population of 5,177,000 people by 1 April 2015 (Statistics Norway 2015).

4 This peak appeared most likely as a consequence of this year being the last chance for students to have their master’s theses, written according to the national pre-Bologna system – the Norwegian hovedoppgave, handed in for examination.

5 The doctoral thesis production of 1995 amounted to four theses. Up until then there had never been more than one such thesis per year, and only 12 were written during the period from 1912–1995.

6 Scandinavian dance band music is a style mainly inspired by British and North-American 1950s and 1960s pop, but also influenced by rock and roll, swing, country, German Schlager music and Scandinavian folk music. It is ‘popular’ in essence and mainly intended for dancing in pairs (Wikipedia Citation2015).

7 See for example Stavrum (Citation2014).

8 In addition, two theses (0.1%) are written jointly by one female and one male author.

9 We have measured ‘heavy domination’ by one gender being responsible for two thirds, or more, of the output related to one particular style.

10 Punk rock is also a female-dominated style, but has only one entrance up until 2012.

11 Rock was introduced by one female and one male author simultaneously, each contributing a thesis including this style in 1983, and is hence counted twice.

12 In 24 of these theses (5.9%), the identities of the supervisors are not known.

13 The overall data regarding supervisors’ gender show a similar domination: Men: 1264 (74.6%); women: 192 (11.3%); identity not known: 239 (14.1%). Considering the year of publication of many of the theses in the ‘identity not known’ category, there is reason to believe that most of these works have been supervised by men as well.

14 The theses stemming from the Norwegian Academy of Music are written within a variety of programmes: music performance, performance practice, music education, music therapy, applied music theory, ear training as well as church music and hymnology.

15 University of Oslo: 160 theses out of 404 (39.6%); Norwegian University of Science and Technology: 98 (24.3%); Norwegian Academy of Music 70 (17.3%).

16 As mentioned above, rock was introduced in two different theses in 1983, and these originated from the two large musicology programmes. Consequently, both programmes are credited for this particular style.

17 These patterns of masculine domination are of course not limited to the phenomenon of musical gentrification only. Armstrong (Citation2011) shows, for example, how similar forces operate in the field of technology and music education.

References

- Ahola, S., T. Hedmo, J.-P. Thomsen, and A. Vabø. 2014. Organisational Features of Higher Education; Denmark, Finland, Norway & Sweden (Working paper 14/2014). Oslo: NIFU Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education.

- Armstrong, V. 2011. Technology and the Gendering of Music Education. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Bateson, G. 1979. Mind and Nature. London: Wildwood House.

- Bennett, T., M. Savage, E. Silva, A. Warde, M. Gayo-Cal, and D. Wright. 2009. Culture, Class, Distinction. New York: Routledge.

- Berkaak, O. A., and E. Ruud. 1994. Sunwheels: Fortellinger om et rockeband [Sunwheels: Tales About a Rock Band]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Björck, C. 2011. “Claiming Space: Discourses on Gender, Popular Music, and Social Change.” PhD diss., University of Gothenburg.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986–2011. “The Forms of Capital.” In Cultural Theory: An Anthology, edited by I. Szeman and T. Kaposy, 81–93. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bourdieu, P. 2001. Masculine Domination. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. J. D. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Chan, T.-W., and J. H. Goldthorpe. 2007. “Social Stratification and Cultural Consumption: The Case of Music.” European Sociological Review 23 (1): 1–19. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcl016

- Cohen, S. 2007. Decline, Renewal and the City in Popular Music Culture: Beyond the Beatles. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- DeVeaux, S. 1999. “Constructing the Jazz Tradition.” In Keeping Time. Readings in Jazz History, edited by R. Walser, 416–424. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DiMaggio, P., and T. Mukhtar. 2002. “Arts Participation as Cultural Capital in the United States, 1982–2002: Signs of Decline?” Poetic 32: 169–194. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2004.02.005

- Dyndahl, P. 2015a. “Hunting High and Low: The Rise, Fall and Concealed Return of a Key Dichotomy in Music and Arts Education.” In The Routledge International Handbook of the Arts and Education, edited by M. P. Fleming, L. Bresler and J. O’Toole, 30–39. London: Routledge.

- Dyndahl, P. 2015b. “Academisation as Activism? Some Paradoxes.” Finnish Journal of Music Education 18 (2): 20–32.

- Dyndahl, P., S. Karlsen, O. Skårberg, and S. G. Nielsen. 2014. “Cultural Omnivorousness and Musical Gentrification: An Outline of a Sociological Framework and Its Applications for Music Education Eesearch.” Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 13 (1): 40–69.

- Dyndahl, P., and S. G. Nielsen. 2014. “Shifting Authenticities in Scandinavian Music Education.” Music Education Research 16 (1): 105–118. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2013.847075

- Fornäs, J., U. Lindberg, and O. Sernhede. 1995. In Garageland: Youth and Culture in Late Modernity. London: Routledge.

- Georgii-Hemming, E., and M. Westvall. 2010. “Music Education – A Personal Matter? Examining the Current Discourses of Music Education in Sweden.” British Journal of Music Education 27 (1): 21–33. doi: 10.1017/S0265051709990179

- Green, L. 2002. How Popular Musicians Learn: A Way Ahead for Music Education. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Green, L. 2008. Music, Informal Learning and the School: A New Classroom Pedagogy. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Gullberg, A.-K. 2002. “Skolvägen eller garagevägen: Studier av musikalisk socialisation [By Learning or Doing: Studies in the Socialisation of Music].” PhD diss., Luleå University of Technology.

- Hansen, M. N., P. L. Andersen, M. Flemmen, and J. Ljunggren. 2014. “Klasser og eliter [Classes and Elite Groups].” In Elite og klasse i et egalitært samfunn [Elite Groups and Classes in an Egalitarian Society], edited by O. Korsnes, M. N. Hansen, and J. Hjellbrekke, 25–38. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hovden, J. F., and K. Knapskog. 2014. “Tastekeepers. Taste Structures, Power and Aesthetic-Political Positions in the Elites of the Norwegian Cultural Field.” Nordisk Kulturpolitisk Tidsskrift 17 (1): 54–75.

- Johansson, K. G. 2002. “Can you Hear What They’re Playing? A Study of Strategies among Ear Players in Rock Music.” PhD diss., Luleå University of Technology.

- Kallio, A. A. 2015. “Drawing a Line in Water: Constructing the School Censorship Frame in Popular Music Education.” International Journal of Music Education 33 (2): 195–209. doi: 10.1177/0255761413515814

- Kamsvåg, G. A. 2011. “Tredje time tirsdag: musikk. En pedagogisk-antropologisk undersøkelse av musikkaktivitet og sosial organisasjon i ungdomsskolen [The Third Lesson on Tuesday: Music. An Educational-Anthropological Study of Music Activity and Social Organisation in Lower Secondary School].” PhD diss., Norwegian Academy of Music.

- Karlsen, S., and L. Väkevä, eds. 2012. Future Prospects for Music Education: Corroborating Informal Learning Pedagogy. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

- Lilliestam, L. 1995. Gehörsmusik: Blues, rock och muntlig tradering [Playing by Ear: Blues, Rock and Oral Tradition]. Gothenburg: Akademiförlaget.

- Longhurst, B. J. 1995. Popular Music and Society. Cambridge: Polity.

- Martin, P. J. 1995. Sounds and Society. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Middleton, R. 1990. Studying Popular Music. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Middleton, R. 2000. “Popular Music Analysis and Musicology: Bridging the Gap.” In Reading Pop. Approaches to Textual Analysis in Popular Music, edited by R. Middleton, 104–121. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moore, A. 2003. “Introduction.” In Analyzing Popular Music, edited by A. Moore, 1–15. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Olsson, B. 1993. “SÄMUS – en musikutbildning i kulturpolitikens tjänst? En studie om en musikutbildning på 70-talet [SÄMUS – Music Education in the Service of Cultural Policy? A Study of a 1970s Teacher-Training Programme].” PhD diss., University of Gothenburg.

- Onsrud, S. V. 2013. “Kjønn på spill – kjønn i spill: En studie av ungdomsskoleelevers musisering [Gender at Play – Gender in Play: A Study of Lower Secondary School Students’ Music-Making].” PhD diss., University of Bergen.

- Peterson, R. A. 1992. “Understanding Audience Segmentation: From Elite and Mass to Omnivore and Univore.” Poetics 21 (4): 243–258. doi: 10.1016/0304-422X(92)90008-Q

- Peterson, R. A., and R. M. Kern. 1996. “Changing Highbrow Taste: From Snob to Omnivore.” American Sociological Review 61 (5): 900–907. doi: 10.2307/2096460

- Sintas, J. L., and E. G. Álvarez. 2002. “Omnivores Show up Again: The Segmentation of Cultural Consumers in Spanish Social Space.” European Sociological Review 18 (3): 353–368. doi: 10.1093/esr/18.3.353

- Statistics Norway. 2015. “Population and population changes, Q1 2015.” Accessed October 4. http://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/folkendrkv/kvartal.

- Stavrum, H. 2014. “Danseglede og hverdagsliv: Etikk, estetikk og politikk i det norske dansebandfeltet [The Joy of Dancing and Everyday Life: Ethics, Aesthetics and Politics in the Norwegian Dance Band Field].” PhD Diss., University of Bergen.

- Stefani, G. 1987. “A Theory of Musical Competence.” Semiotica 66 (1–3): 7–22.

- Tagg, P. 1982. “Analysing Popular Music: Theory, Method and Practice.” Popular Music 2: 37–67. doi: 10.1017/S0261143000001227

- Thune, T., S. Kyvik, S. Sörlin, T. B. Olsen, A. Vabø, and C. Tømte. 2012. PhD Education in a Knowledge Society. An Evaluation of PhD Education in Norway (Report 25/2012). Oslo: NIFU Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education.

- Tønsberg, K. 2013. Akademiseringen av jazz, pop og rock – en dannelsesreise [The Academisation of Jazz, Pop and Rock – An Educational Journey]. Trondheim: Akademika forlag.

- Väkevä, L. 2006. “Teaching Popular Music in Finland: What’s up, What’s Ahead?” International Journal of Music Education 24 (2): 126–131. doi: 10.1177/0255761406065473

- Walser, R. 1993. Running with the Devil. Power, Gender and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. London: Wesleyan University Press.

- Westerlund, H. 2006. “Garage Rock Bands: A Future Model for Developing Musical Expertise?” International Journal of Music Education 24 (2): 119–125. doi: 10.1177/0255761406065472

- Wikipedia. 2015. “Dansband.” Accessed August 25. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dansband.

- Zandén, O. 2010. “Samtal om samspel: Kvalitetsuppfattningar i musiklärares dialoger om ensemblespel på gymnasiet [Conversations about Interplay: Perceptions of Quality in Music Teachers’ Dialogues on Ensemble Playing in Upper Secondary School].” PhD diss., University of Gothenburg.