ABSTRACT

Swiss educator, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze observed over 100 years ago that often music conservatoires focus primarily on the development of technique and repertoire, at the expense of musicianship. His embodied approach to music education aims to connect all our faculties, emotional, corporeal and intellectual, through experiencing music making, in and through movement. This arts practice research addresses how embodiment in classical music instrumental education can be enhanced by an embodied teaching method such as Dalcroze Eurhythmics. The research journey culminated with ‘Dance of Shadows’, a multi-disciplinary, multi-sensorial interpretation of Eugène Ysaÿe’s second sonata for solo violin, opus 27. To document the intrinsic reflexivity of the research, the researcher utilises the tools of artistic research and other arts practice methods. The findings of this investigation revealed not only an enhancement of the researcher’s embodied preparation and performance practice but also a transformation in the experience of engagement for the audience.

Introduction

My career has been built through an application of the conventional approaches to practicing the violin: technique building combined with the learning and memorising of classical repertoire. However, I have long been haunted by a suspicion that my focused training as a violinist operated to the detriment of my development as a musician. I was first introduced to the ideas of Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (henceforth EJ-D) as a student many years ago and have used his methods as a teacher throughout my career. Unfortunately, I didn’t apply his ideas to my professional practice as a violinist. My training in musical performance was dominated by intellectualism, theory and traditional practices of the very same kind that EJ-D observed in his conservatoire students over 100 years ago; technically gifted yet musically hidebound (Jaques-Dalcroze Citation1945).

For over twenty years, I have been both a professional violinist and an educator informed by the theories of EJ-D. In the former capacity, I am a violinist in the Irish Chamber Orchestra and in preparation for this research paper, I decided to ask my colleagues two questions. Had they heard of Dalcroze Eurhythmics (henceforth DE) and, if so, who did they associate it with? The overwhelming response to the first question was ‘no’, with an odd ‘yes-but I don’t really know what it is’. Those who said the latter also revealed that they associated it with young children. The multitude of ‘no’ responses from my colleagues, exposed how separate I had kept these two parts of my life; my life as a violinist and that of a DE-based educator. I also came to realise that for most of these years, I was at best unaware of and at worst propagating the chasm between the violinist and educator selves.

Research question

The artistic research I am presenting in this paper is part of a wider research project exploring the impact of DE on my practice as a classically trained violinist, performer and teacher. This research investigated whether instrumental teaching and performance could be enhanced by an embodied method such as DE. I use the term embodied in this paper to articulate when the physical, intellectual and emotional faculties, are connected to the music, instrument and space; allowing the performer to become an ‘integrated vessel of expressive communication’ (Daly Citation2021a, 5). The work presented in this paper is one of two performances which I devised and developed to address this question (Daly Citation2021a).

State of research

There has been substantial research in DE undertaken in relation to general music education (Farber and Parker Citation1987; Bachmann Citation1991; Juntunen and Westerlund Citation2011; Greenhead, Habron, and Mathieu Citation2016), plus a significant growth in research around DE as a somatic practice and practice of embodiment (Mead Citation1999; Bresler Citation2004; Pucihar and Pance Citation2014; Greenhead and Habron Citation2015). In comparison, there has been limited research published in relation to the professional musician (Gaunt Citation2010; Greenhead Citation2017; Daly Citation2019). This investigation sought to address the gap in the literature regarding the application of DE to professional development, highlighting the influence of the renowned Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe on EJ-D. Studies by Hanlon Johnson Citation1995 and Sheets-Johnstone Citation1981 emphasise the importance of embodied practices. Other relevant research in this area concerns the impact of body-based approaches on musical expression, communication and performance (Burnard Citation1999; Davidson and Correia Citation2001, Citation2002; Davidson Citation2004; Kotyk Citation2009; Pierce Citation2010).

Every piece of artistic research is context specific, including the specificity of performer, and the repertoire context. Regardless of the individualistic nature of this research, sharing specific findings enables other performer-researchers to develop similar work within their own context. The initial driver in this research was to find ways to connect the two sides of my musical training, violinist and DE educator. I was a researcher looking for better music-making experiences, not only for myself as a professional musician, but also for the wider community involved in the education of young classical musicians.

Dalcroze and Ysaÿe: how an embodied violin player inspired Dalcroze Eurhythmics

EJ-D (1865–1950) designed DE as a three-part structure: Rhythmics, Aural training, and Improvisation, leading to the living analysis of music known as Plastique animée (Bachmann Citation1991; Greenhead Citation2016; Collège Citation2011; Daly Citation2021a). Music is experienced through movement: engaging mind, emotion and our primary instrument, the body (Jaques-Dalcroze Citation1921/1967). Movement ‘is not the private possession of dancers and athletes; rather, it hovers in every nook and niche of the musician’s life’ (Shehan-Campbell Citation1987, 30). His stated aim was to inject what he felt to be a lost sense of musicianship into the sphere of professional musicians (Greenhead Citation2008; Gaunt Citation2010; Mathieu Citation2013).

When the virtuoso violinist, Eugène Ysaÿe, engaged EJ-D to be his piano accompanist in 1898, it formed the final piece in the jigsaw in the creation of DE (Jaques-Dalcroze Citation1942; Christen Citation1946; Greenhead Citation2015). EJ-D had been developing his method for around five years when he encountered Ysaÿe, whereupon he found himself ‘seduced by his vitality, the strength of his convictions, his scorn for conventions, and by the ardour of his feelings’ (Jaques-Dalcroze Citation1942, 42). He witnessed first-hand how Ysaÿe used his body to interpret and practice the music he was learning.

He liked to work his technique in darkness or with closed eyes, to better-he said- go back to the source of the physical movements … And I often surprised him … in his room delivering himself of an expressive mime putting his entire body into motion, rhythmically and plastically, while the right arm and fingers maintained all their lightness for the performance of the virtuoso strokes. “The sound vibrations”, he said, “must penetrate us entirely right down to our viscera, and the rhythmic movement must enliven all our muscular system, without resistance or exaggeration. (Jaques-Dalcroze Citation1942, 44)

These insights reveal the importance of developing a kinesthetic body and of building a holistic approach to the body and mind (Hanlon Johnson Citation1995; Sheets-Johnstone Citation1981). Ysaÿe’s approaches to practising and performing placed the musical performer at the heart of DE.

From Bruckner, Dalcroze had learned a rigorous classical precision, and from Prosnitz the notion that a musician must seek and contact the emotional content of compositions. Lussy showed him that rhythm had a physical basis and was the key to expressive performance, and with North African musicians he saw and felt how compelling it was to be swept away in a rhythmic storm. Ysaÿe demonstrated all of these qualities through his virtuosity in action. Everything came together for Dalcroze by joining Ysaÿe in the crucible of performance. (Lee Citation2003, 52)

It is the essence of this influence that lies at the crux of this research, directing an important focus on the relationship between DE and the performer.

Method

While the research on which this work is based involved a mixed-method approach, this article focuses on the investigation’s artistic research dimension, which is an experiential, subjective approach in which the researcher’s practice, feelings and intuition are the subject of study and source of data. If I wished to understand the value DE had for my practice as a performer, then I needed to perform, to enable me, the researcher ‘to fully represent my lived experience’ (Daly Citation2021b). To document the value of an experiential ‘music education through movement’ method, then I needed to move and experience. Only then could it be demonstrated ‘that practice as research not only produces knowledge that may be applied in multiple contexts but also can promote a more profound understanding of how knowledge is revealed, acquired and expressed’ (Barrett and Bolt Citation2010, foreword). This model fits well within the whole experiential ethos behind the work of EJ-D. As painter Paul Perrelet said, ‘It is not possible to form an opinion on Eurhythmics without having taken part in it’ (Dutoit Citation1971, 11).

Artistic research is a model in which hard facts and empirical truths are impossible. Instead, there is a sense of ‘liquid knowledge’, something that ‘runs through your system’ (Abramovic in Nelson Citation2013, 52), requiring the researcher ‘to dig deep inside’ (Daly Citation2021c, 2469). This research model requires a variety of documentary methods, all of which need to reflect the qualitative and subjective nature of the process of inquiry (Creswell Citation2013; Denzin and Lincoln Citation2018). My chosen methods of reflexive documentation are autoethnography (Bartleet and Ellis Citation2009; Chang Citation2008,) and arts-based methods (Leavy Citation2009; Bochner and Ellis Citation2003). I have used journaling, poetry and other forms of artistic expression alongside data gathered from others, through interviews, focus groups and by inviting written inputs. I write from the first person, weaving between my narrative and theoretical voices (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000).

Autoethnography is a key reflexive method of documentation approach for my practice, as it allows me to turn the investigative lens on my work (Bochner and Ellis Citation2003; Denzin and Lincoln Citation2018; Daly Citation2021b, Citation2021c). This enables me to position my research within the broader cultural, institutional, and pedagogical realms of my personal culture, that of the Western classically trained musician.

Rehearsal design and preparation

The distinctions and characteristics of EJ-D and Ysaÿe in some respects mirror my internal professional practice – the music educator looking for more than technique and analysis, and the professional violinist looking for ways to be fully creative as an interpretative artist. For this investigation, rather than drawing upon my usual preparation of learning notes, interpreting, polishing technical aspects and reproducing them in the concert hall, I decided to fully immerse myself in the philosophies of EJ-D and Ysaÿe, remaining true to them at all stages – learning, conception, delivery, aftermath. I would take the idiosyncratic, embodied way Ysaÿe had of rehearsing, and integrate it with the embodied somatic approach to music education conceived by EJ-D, which the violinist had inspired (Daly Citation2019). At an International Dalcroze conference, I witnessed the Dalcrozian movement artist Ava Loiacono perform an original theatre piece, which incorporated puppetry, ventriloquism and music. I was greatly inspired by Ava’s performance and open-minded approach to her practice, and asked her if she would consider helping me to learn the Ysaÿe using DE as a process of learning (Farber and Parker Citation1987). Within a few weeks, Ava and I were fully collaborating on, not only the preparation of the music but also on how to bring Dalcrozian elements of embodiment into the performance itself (Pucihar and Pance Citation2014; Greenhead and Habron Citation2015).

The result was ‘Dance of Shadows’, a multi-disciplinary, multi-sensorial interpretation of Eugène Ysaÿe’s second sonata for solo violin, opus 27. Ysaÿe was not only an inspirational embodied violinist, but was also a wonderful composer. His seminal six solo sonatas for violin, inspired by J. S. Bach’s writing of six solo sonatas and partitas, are fiendishly difficult, complex and challenging. The work at the centre of this research exploration is the second of these sonatas, dedicated to the French violinist Jacques Thibaud. The four movements are titled, Obsession, Malinconia, Danse des Ombres and Les Furies.

Dalcroze Eurhythmics infusion

There are four bullet points listed in the Philosophy and Principles section of The Dalcroze Identity (Collège Citation2011). Three of these, listed below, were heavily considered in the devising of this performance.

The body is the locus of experience and expression, personal and artistic.

The evolution of the human person depends on the ability to put physical and sensory experience at the service of thought and feeling.

The human being is social, always in relationship to/with others.

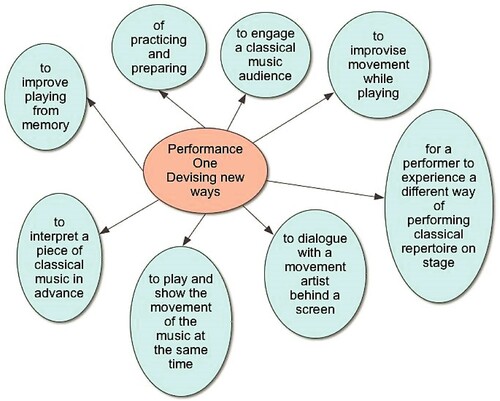

To fully interrogate my research question, I devised a performance which focused on developing and devising the following ways ().

Embodied approaches

The approaches I used are summarised as follows:

Embodiment techniques where I learned the music away from my instrument, including visualisation and mental practice.

I explored finding the movement in the music by transferring the music imaginatively into an object such as a ball and allowing the object to show the phrasing and harmonic intensity within the music. Dr. Karin Greenhead, who worked with me on this exercise, has devised an original application of DE in the form of Dynamic Rehearsal (Greenhead Citation2016).

I played as if from different parts of my body. For example, if I imagined the sound was coming from my lower back, it would sound very different than if it was originating from my feet or underarms.

I conducted, stepped and sang each phrase, vocalising with different consonants and vowels to discover what most appropriate articulations the music desired.

I devised floor maps to clarify where the architecture of the phrases started and ended, and connected them to my breath. As I played, I showed these directions in my body, conveying the breath, tension and release in every phrase. I termed this way of making the music visible as I performed, Creative Embodied String Performance (Daly Citation2021a).

For the second movement that had two lines played simultaneously, I sang one line while stepping the other and swapped over. I also played both lines on the piano with my hands very far apart and added singing one line at a time. I also worked on playing one line on the violin while stepping the other to work on my inner hearing of both lines.

I performed the music in movement, away from the instrument, finding the feeling of the accents, articulation, character changes and phrasing architecture. This projection of my musical intention into the performance space was described by EJ-D as Plastique Animée (Juntunen Citation2002). When the distraction of playing the instrument is removed it enables a much stronger sense of attention to detail within the music. EJ-D believed this process ‘should aim especially at the arousing of natural instincts, spontaneous outbursts, (and) individual conceptions’ (Jaques-Dalcroze Citation1924, 26). I used my violin-playing body ‘in space as a learning tool’ to examine the ‘interpretation, characterisation, memorisation and communication’ of the music (Daly Citation2021a, 6). Often the emotional connection created a narrative for me, which then further intensified my responses (Shusterman Citation2000, Citation2008).

I devised ways to further show the visibility of the music as I played. Playing and moving at the same time required 100% embodied commitment. Each turn or step had to have meaning and feeling, driven by my imagination in each moment and in the movement of each note. In open rehearsals, it became obvious to the listener every time I played a note that wasn’t fully embodied, just by hearing my sound.

I used a large elastane cloth as a screen on the stage where my co-performer Ava, moved from behind, in dialogue with the music I was playing. The screen represented the Dies Irae theme which is woven throughout the full work. This highlighted the various dialogues implied; between the music and the screen, between myself and the person moving behind the screen, between my playing and my movement and the screen, myself and the audience. The screen was also used to explore the use of lighting as I conjured up how the music conceived a perception of different colours in my imagination. Feeling and moving the music in terms of colour and textures creates a more vivid dynamic interpretation. Every aspect of these decision-making processes brought me ever closer to a deeper connection with the piece.

Here are four images from the performance depicting a selection of the lighting choices.

Narrative

There was another strong pull towards this sonata due to its narrative appeal. Atkinson (Citation1997) and Bochner (Citation2001), refer to the power of the narrative in research and at the heart of this violin composition lies an imaginative story rich in detail, emotion and colour. The movement titles alone suggest a storyline evoking a character obsessed with the music of Bach, who enters a state of melancholia, before embarking on a dance of shadows that leads him directly to hell. The music conjures up images of darkness, obsession, depression, beauty, reflection, loss, aggression, determination, and death. There is no documented evidence that Ysaÿe conceived this as a programmatic work (Christen Citation1946), but I decided to use artistic licence and explore the narrative that the music implied to me.

EJ-D had a lifelong love affair with the dual worlds of music and theatre (Dutoit Citation1971), and although he eventually chose music as his career path, he managed to successfully weave the elements of theatre and storytelling into his teaching, improvisation, and compositions. This inspired me to do the same with this sonata, being also conscious of the rich collaboration between Adolphe Appia and EJ-D (Appia Citation1962). The pioneering stage designer inspired EJ-D in the lighting and staging of his musical productions (Stadler Citation1965; Abdel-Latif Citation1988), while Appia in return attributed the development of his career greatly to Dalcroze Eurhythmics (Beacham Citation1985).

In the end, I had devised a piece where in the first movement, the character begins in a searching way, confused and lost in his obsession for the music of J.S. Bach, conveyed in the many musical references. The Dies Irae theme was presented musically and visually by Ava behind the screen, varying in character with the emotion of the music. The ebbs and flows of this first movement convey a tortured violinist, emphasised by my use of movement, lighting, space, energy, and interaction with the screen. My movement choices correspond to these emotional cadences, highlighting the phrasing, harmonic and melodic contours and rhythmical aspects of the music. The movement ends with a dance-like dialogue between violinist and death.

Image 5 Excerpt from Malinconia, second movement

I showed the phrasing through my movement in the space, supported and emphasised by Ava’s light from behind the screen. The variety within the architecture of each phrase was conveyed by whether I chose to kneel, rise, lean, bow, go towards or away from the screen, eventually lowering to the ground during the penultimate and final bar. The segue into the full iteration of the Dies Irae theme was enabled by a blackout, giving me the time to get into position, to perform the music of death while lying on my back, flat on the floor.

The third movement, Danse des Ombres, is in the form of a baroque dance, the Sarabande.

Image 6 Theme from Danse des Ombres, third movement

The theme, which consists of plucked three and four-part chords, took many hours of practice to bring out the optimum resonance for each plucked note. This desired resonance required each touch of the specific right-hand finger to be at exactly the halfway point between the bridge and the left-hand finger position, while also bringing out the melody line. The audience could see my shadow on the screen during this theme, but I was, at this point, unaware of the presence on the screen behind me. As each variation progressed, the shadow changed, varying in size and in the intensity of shade and definition. It fluctuated between representing me, representing death, reflecting my movement or my music, or that of something different. The dance of shadows became the journey of self-discovery in variation one, encountering the alter-ego in variation two, emotional connection in variation three, a sinister turning and twisting of events in variation four, darting playfulness in variation five, through to an intense rollercoaster variation six, before finally reaching a triumphant reiteration of the theme in arco (played with the bow).

The final movement, Les Furies, marked ‘furioso’, depicts the three female characters associated with the journey to hell, and are represented by the angry three-part chords throughout.

Image 7 Excerpt from Les Furies, fourth movement

The red lighting, my playing, movement and interaction with the screen and Ava’s performance of the Dies Irae theme combined to create a dramatic interpretation which resulted in a thrilling finish. When the composer, Ysaÿe himself, was asked how to define a ‘master’ of the violin he replied, in Martens, with the following words.

He must be a violinist, a thinker, a poet, a human being, he must have known hope, love, passion and despair, he must have run the gamut of the emotions in order to express them all in his playing. He must play his violin like Pan played his flute! (Ysaÿe in Martens ed. Citation1919, 7)

Data collection and analysis

Throughout the research investigation, I documented the rehearsals and performances through rigorous journaling and daily audiovisual recordings. To elicit post performance data, I utilised the ethnographic research tools of interviews and focus groups (Kamberelis and Dimitriadis Citation2011). A focus group with 8 musicians was hosted to obtain external perspectives from a cross-section of teaching and performing faculty, immediately after the performance. The questions posed to the particpants were designed to focus on aspects of embodiment and to explore individual personal responses. I also conducted one on one interviews with 12 selected members of the audience, who were primarily faculty researchers, teachers and performers. In view of the autoethnographic arts-based nature of my research journey, these participants also presented me with pictures, drawings, poems and text (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000; Chang Citation2008). All participants signed consent forms.

The research data was systematically analysed, using thematic analysis (Clarke, Braun, and Hayfield Citation2015). I applied colour-coding techniques to the journals, interviews, focus group data and audio-visual recordings, assigning selected colours to certain themes and different shapes to sub-themes. This allowed the themes to emerge and to be grouped thematically. Lastly, I used mind mapping software (Inspiration version 9) to create tables of quotes and excerpts relevant to the themes. This approach to data gathering and analysis facilitated a better understanding of the relationships and connections between the ideas and concepts, while remaining true to the rigour and fluidity vital to the investigation (Bispo Citation2015).

Findings

This section presents the key concepts that evolved from an analysis of the data, which includes a spectrum of material around the themes of embodiment and audience engagement. Analysis of the data from the post-performance focus group revealed how the application of DE on preparation and performance of a classical music work, greatly enhanced the performers' sense of embodiment on stage, which in turn had a strong impact on the audience’s level of engagement. Seven out of the eight participants referenced that they witnessed ‘heightened embodiment’ within the ‘performers body’ and ‘playing the violin’. The data revealed how this was manifested through ‘enhanced sound production’, ‘vivid characterisation and story telling’ and ‘clear articulation’. All eight members of the focus group experienced ‘an extraordinary connection between performer and listener’. Five participants said that I seemed to ‘own the stage’ in a way that they felt was unusual at a classical music concert. All eight expressed feeling ‘deeply engaged’ which they believed was facilitated by the embodiment on stage. After the performance, I interviewed 12 audience members who represented a cross-section of artistic disciplines. The words ‘embodied presence’ and ‘communication’ appeared in nine of the interviews data. All 12 commented on how ‘engaging’ the performance was and 9 mentioned the term ‘connection’. My ongoing Dalcroze training envelops me in these concepts all the time, but never in an all-encompassing way with my violinist self at the centre. All eight focus group participants discussed how they felt ‘gripped’ and ‘engaged’ by the narrative and the lighting. They referred to the ‘communication’ of the ‘story’ within the music, which ‘facilitated a wave of connection’. A significant research finding was that my performance opened a door to a new way of experiencing a classical music concert by bringing narrative and imagination to triggering empathy in the audience. This personal engagement gave a different dimension to the performance, changing the focus of what is important to be shown. The experience of the performer moving, sensing, telling, giving, exploring and feeling the music resulted in a multi-sensory experience that transformed the audience engagement experience. There was further discussion in the focus group as to the importance of embedding multi-sensory experience into every music lesson, regardless of the repertoire or instrument being taught.

Discussion

Embodiment

This performance of Ysaÿe through DE sought embodying my development as a violinist, a quest to find myself in that newly embodied violin playing role, and my acceptance of that role. In applying the principles of DE inspired by the embodied practice of Ysaÿe discussed earlier, I hoped that my work on embodying this music physically, would result in a different kind of performance experience. I was also interested to observe if I would experience any performance anxiety, particularly due to playing from memory, or whether this form of learning could have a positive impact on this common aspect of classical performers' lives (Roland Citation1994; Greenhead Citation2016). I interrogated the awareness of the ‘sense of complicity’ that exists between personal movement and the music that brings it out’ (Bachmann Citation1991, 34), which she envisaged to be ‘the cornerstone of the entire educational process of Eurhythmics’ (Bachmann Citation1991, 34).

The investigation of realising the music through my playing and my body, became a significant element in the preparation and performance process, as I found myself digging deeper into my idea of moving while playing, in an effort to become more at one with the music. I wished to take the basic element of plastique animée, showing how the music moved, and investigate how this might apply while performing.

Research shows how effective bodily movements can be in communicating musical expression (Burnard Citation1999; Kotyk Citation2009), leading me to explore the possibilities of how to take this further. ‘The significance of movement as non-verbal communication frequently adds to the power of the … performance’ (Shehan-Campbell Citation1987, 30). The writings of Davidson and Correia Citation2001, Citation2002; Davidson Citation2004; and Pierce Citation2010, drill directly into the impact of movement and bodily gesture on musical performance. As a violinist, there are certain bodily movements that are necessary to play the instrument well, which Clarke (Citation2012) describes in terms of a spectrum, ranging from ergonomical, efficient and comfortable, to actual choreography. The technical requirements of playing such a difficult piece of music well would naturally limit my movement, and it was of course crucial that the quality of the music must not be compromised in any way. I was particularly keen that the process would remain loyal to showing the character and emotion inside the music and never become choreography that was placed superficially upon the playing.

The eurhythmics student does not learn steps; certainly not in the sense a dancer does … The essential challenge is how to enact particular musical meanings in physical space. The point of meeting that challenge (and the aim of the eurhythmics class) is to deepen both his understanding of, and ability to produce, music. (Farber and Parker Citation1987, 45)

In the words of Mead (Citation1999, 15), ‘[t]he study of music has its own rewards, but it is good to remind oneself occasionally that music’s path to the mind is inevitably through the body’. I investigated the concept of inscribing the written music into my performing body (Crispin Citation2009), and homing in on the listeners’ ability to, not only ‘hear a performer’s body in the music’ (Bowman in Bresler Citation2004, 41) but also to experience it visually and kinesthetically.

Performance – audience and engagement

In my whole performing career, spanning over 30 years, I had never been so aware of the absolute engagement of a classical music audience before. The audience was unusually engaged and actively listening, which in return enabled me to perform in a different way than I had previously (Bernstein Citation1976; Juntunen Citation2002). The energy was palpable, and I felt my listeners were on my journey with me. Ava and I had discussed these issues during the rehearsal period where she described the necessity for her to switch on a special radar that would connect her to me, even from behind the screen. In the performance, the essence of this radar passed and travelled between myself and Ava, to the audience, and back to us, the performers, in a sort of endless circle that allowed the flowing of emotional communication.

During rehearsals, Ava and I also discussed my desire to connect with the audience’s hearts and souls and that we could try to achieve this by stimulating their senses, ears, eyes, and the kinesthetic sense (Jaques-Dalcroze Citation1921/1967/). Much is written in terms of today’s classical music audiences sitting perfectly still and silent (Small Citation1980; Bailey Citation1992). I wished for the audience to move with the music in their imaginations, with me as I performed. Viewing the performers’ gestures creates a kinetic experience quite different from listening to a recording. By using the space, I wanted them to feel the energy, the dynamics, and the melodic contours, but what I hadn’t anticipated was that the energy, that ‘wave’, would come back at me, the performer. It nourished, encouraged, and inspired me in every aspect of my performance. In an interview with Prof. Helen Phelan (Citation2018), she described how she felt my performance communication invited a multi-sensory response to the music. She described, as a regular classical music concert goer, how she usually receives a really strong message to sit quietly and very still, to almost shut down physically and to disembody oneself.

So what you did was the opposite. First of all, what you did when you came out to speak at the beginning, you conveyed a relaxed, engaged, experimental … you didn’t feel that? … I felt the audience knew that that you were trying something new. Immediately it meant the audience were trying it with you. (Interview with H. Phelan Citation2018)

In the final movement, where I look into the audience, as if looking for someone or something, I was trying to break down the invisible but very real wall that usually separates players from their audience. EJ-D was very influenced by Appia’s groundbreaking insights in this area (Stadler Citation1965; Abdel-Latif Citation1988) and Ava and I explored how the use of the eyes, and the gaze, supports this idea.

Neuroscience research suggests that mirror neuron networks may trigger the same process in the audience as if they were performing themselves (Pucihar and Pance Citation2014). During this performance, the audience, therefore, were engaged audially, visually, kinesthetically and emotionally. This intense energy that rose back at me from the audience must therefore have been a reflection of the level of engagement and presence emanating from the performance space.

The performance began with a welcoming presentation to the audience, allowing me to connect with my listeners from the outset. For the final part of my performance, I invited people to join me in the space and reflect in silence together (Blom, Bennett, and Wright Citation2011). I explained that it was something that I as a performer wished to try and was curious if they might like to try it also. I had brought card and writing elements for people to document their experience visually if they wished. I was concerned that is might feel very strange to do this in silence, as there is normally a lot of chatting to be heard after a concert. I also felt uneasy that it might make my friends, colleagues and general audience members feel very uncomfortable or put pressure on them to ‘perform’ in some way. This was not the case. Afterwards, in an interview Phelan (Citation2018) described how, as an audience member she liked my invite into the performance space itself, bridging the divide. She experienced embodiment and fluidity in the whole event, ‘a sense of flow and movement that infected the whole space’ which counteracted what she often experiences at classical music concerts as a rigidity of performance presentation – ‘performer doesn’t move, audience doesn’t move’ (Phelan Citation2018).

Conclusion

This research investigated how embodiment in classical music performance can be enhanced by an embodied method such as DE. The interpretation of Ysaÿe’s work, revolved around the body being the centre of experience and expression. This created a multisensory experience for the performers and the audience, where the dialogue between the musical characters was conveyed through movement, lighting and musical expression. The findings revealed not only an enhancement of the researcher’s embodied preparation and performance practice but also a transformation in the experience of engagement for the audience.

This paper focuses on the findings from a singular multi-sensory performance, which included movement, lighting, a screen and a movement artist. Further research could be undertaken to explore how it would feel to perform this piece in a more traditional setting.

The investigation revealed an embodied artist, who identified as what Erskine (Citation2009) described as a moving thinking artist, who no longer lives in her head (Whitehouse in Pallaro Citation1999), but has come home to her body (Hartley Citation1995). By the performer coming home to her body, so did the audience – all the strands of performance culminating in a holistic embodied presence. The research findings revealed an artist more connected to her music, body and instrument, in her practice and performance. This embodied presence on stage subsequently enabled a stronger connection with the audience. The research revealing speaks primarily to a redress of values in the teaching studio, a shift from my previous values dominated by skill and technique in the culture I know, the world of classical music, to one that also embraces the value of connection and embodied presence. This research has transformed how I teach my students, from beginners up to professionals. All my lessons now aspire to reflect the experience of the performer moving, sensing, telling, giving, exploring and feeling the music. Although personal to me, it is intended that these findings may inspire and resonate with other teachers and performers.

Click here to view an edited 3-minute video of the live performance. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wW_pH5ao0Nw&feature=youtu.be

Click here to view the full live 19 minute live performance. https://vimeo.com/535543626/23dcc16cbb

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Diane K. Daly

Diane Daly is a violinist and has been a member of the Irish Chamber Orchestra since 1998. She is a passionate educator and animateur and is the founder and artistic director of both Saturday Strings @ ICO teaching programme and Libra Strings. She completed an Arts Practice PhD in 2019, being the recipient of a prestigious scholarship from the Irish Research Council. She is course director of the MA in Classical String Performance in the University of Limerick where she teaches Violin, Chamber Music, Dalcroze, Kodaly and Improvisation.

References

- Abdel-Latif, Mahmoud H. 1988. Rhythmic Space and Rhythmic Movement: The Adolphe Appia/Jaques-Dalcroze collaboration. Ph.D. dissertation, The Ohio State University, Ohio. Dissertations & Theses: A&I. (Publication No. AAT 8907181).

- Appia, Adolphe. 1962. “Music and the art of the Theatre.” In Books of the Theatre Ser., No.3, edited by R. W. Corngan, M. D. Dirks, and Barnard Hewitt, 29–31. University of Miami Press.

- Atkinson, Paul. 1997. “Narrative Turn or Blind Alley?” Qualitative Health Research 7: 325–344.

- Bachmann, Maire-Laure. 1991. Dalcroze Today: An Education Through and Into Music. (David Parlett, Trans.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bailey, Derek. 1992. Improvisation. Its Nature and Practice in Music. UK: Da Capo Press.

- Barrett, Estelle, and Barbara Bolt. 2010. Practice as Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry. London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Bartleet, Brydie-Lee, and Carolyn Ellis. 2009. Music Ethnographies: Making Autoethnography Sing/Making Music Personal. Sydney: Australian Academic Press.

- Beacham, R. C. 1985. “Appia, Jaques-Dalcroze, and Hellerau, Part one: Music Made-Visible.” New Theatre Quarterly 1: 154–164.

- Bernstein, Leonard. 1976. The Unanswered Question: Six Talks at Harvard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bispo, Marcelo de Souza. 2015. “Methodological Reflections on Practice-Based Research in Organization Studies.” BAR - Brazilian Administration Review 12 (3): 309–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-7692bar2015150026.

- Blom, Diana, Dawn Bennett, and David Wright. 2011. “How Artists Working in Academia View Artistic Practice as Research: Implications for Tertiary Music Education.” International Journal of Music Education 26 (2): 109–126.

- Bochner, Art P. 2001. “Narrative's Virtues.” Qualitative Inquiry 7 (2): 131–157.

- Bochner, Art P., and Carolyn Ellis. 2003. “An Introduction to the Arts and Narrative Research: Art as Inquiry.” Qualitative Inquiry 9 (4): 506–514.

- Bresler, Liora. 2004. Knowing Bodies, Moving Minds: Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Burnard, Pamela. 1999. “Bodily Intention in Children’s Improvisation and Composition.” Psychology of Music 27 (2): 159–174.

- Chang, Heewon. 2008. Autoethnography as Method. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Christen, Ernest. 1946. Ysaÿe. Geneve: Labor et Fides.

- Clandinin, D. Jean, and F. Michael Connelly. 2000. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story. Qualitative Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Clarke, Eric F. 2012. “Creativity in Performance.” In Musical Imaginations: Multidisciplinary, edited by D. J. Hargreaves, D. E. Miell, and R. A. R. MacDonald. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, Victoria, Virginia Braun, and Nikki Hayfield. 2015. “Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods 222: 248.

- Collège, de L’Institut Jaques-Dalcroze. 2011. L’identité Dalcrozienne: Théorie et Pratique de la Rythmique Jaques-Dalcroze/The Dalcroze Identity: Theory and Practice of Dalcroze Eurhythmics. Geneva: Institut Jaques-Dalcroze.

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing among the Five Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Crispin, Darla. 2009. “Artistic Research and the Musician’s Vulnerability.” Musical Opinion 132: 25–27.

- Daly, Diane K. 2019. A Dance of Shadows through Arts Practice Research.” Le Rythme 141–150. https://www.fier.com/uploads/pdf/le-rythme-2019.pdf.

- Daly, Diane K. 2021a. “ Creativity, Autonomy and Dalcroze Eurhythmics: An Arts Practice Exploration.” International Journal of Music Education 40 (1): 105–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/02557614211028600.

- Daly, Diane K. 2021b. “Playing With the Past: An Autoethnography.” Qualitative Inquiry 28 (3–4): 353–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004211026897.

- Daly, Diane K. 2021c. “Unearthing the Artist: An Autoethnographic Investigation.” The Qualitative Report 26 (8): 2467–2478. doi:https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4796.

- Davidson, Jane W. 2004. The Music Practitioner. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Davidson, Jane W., and Jorge S Correia. 2001. “Meaningful Musical Performance: A Bodily Experience.” Research Studies in Music Education 17 (1): 70–83.

- Davidson, Jane W., and Jorge S Correia. 2002. “Body Movement.” In The Science and Psychology of Music Performance: Creative Strategies for Teaching and Learning, edited by R. Parncutt, and G. E. McPherson, 237–250. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S Lincoln. 2018. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research 5th Edition. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Dutoit, C. L. 1971. Music Movement Therapy. London: The Dalcroze Society.

- Erskine, Shona. 2009. “The Integration of Somatics as an Essential Component of Aesthetic Dance Education.” In Dance Dialogues: Conversations Across Cultures, Artforms and Practices, Brisbane, 13-18 July, edited by C. Stock, 12–15. Queensland: QUT Creative Industries and Ausdance.

- Farber, Ann, and Lisa Parker. 1987. “Discovering Music Through Dalcroze Eurhythmics.” Music Educators Journal 74 (3): 43–45.

- Gaunt, Helena. 2010. “One-to-one Tuition in a Conservatoire: The Perceptions of Instrumental and Vocal Students.” Psychology of Music 38 (2): 178–208.

- Greenhead, Karin. 2008. “Dalcroze Eurhythmics in the Training of Professional Musician.” In Proceedings: 28th International Society for Music Education World Conference, 20-25 July, Bologna, Italy, edited by J. Habron, 107–111.

- Greenhead, Karin. 2015. “Ysaÿe, the Violin and Dalcroze.” In 2nd International Conference of Dalcroze Studies: The Movement Connection (Paper), Vienna, Austria, July 26–29, 2015, edited by J. Habron, 21–25.

- Greenhead, Karin. 2016. “Becoming Music: Reflections on Transformative Experience and the Development of Agency Through Dynamic Rehearsal.” Arts and Humanities as Higher Education 15: 3. http://www.artsandhumanities.org/journal/becoming-music-reflections-on-transformative-experience-and-the-development-of-agency-through-dynamic-rehearsal/.

- Greenhead, Karin. 2017. “Applying Dalcroze Principles to the Rehearsal and Performance of Musical Repertoire: A Brief Account of Dynamic Rehearsal and its Origins.” In Pédagogie, art et Science: L’apprentissage par et Pour la Musique Selon la Méthode Jaques-Dalcroze. Actes du Congrés de L’Institut Jaques-Dalcroze, 2015, 153–164. Genève: Droz. Haute école de musique de Genève. ISBN: 978-2-600-05824-7.

- Greenhead, Karin, and John Habron. 2015. “The Touch of Sound: Dalcroze Eurythmics as a Somatic Practice.” Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices 7 (1): 93–112.

- Greenhead, Karin, John Habron, and Louise Mathieu. 2016. “Dalcroze Eurhythmics: Bridging the gap Between the Academic and Practical Through Creative Teaching and Learning.” In Creative Teaching for Creative Learning in Higher Music Education, edited by Elizabeth Haddon, and Pamela Burnard. Routledge: Abingdon. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315574714.

- Hanlon Johnson, Don. 1995. Bone, Breath and Gesture: Practices of Embodiment. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

- Hartley, Linda. 1995. Wisdom of the Body Moving. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

- Jaques-Dalcroze, Emile. 1921/1967. Rhythm, Music & Education. Harold Rubenstein (Trans). Woking, Surrey: The Dalcroze Society.

- Jaques-Dalcroze, Emile. 1924. “The Technique of Moving Plastic.” The Musical Quarterly 10 (1): 21–38.

- Jaques-Dalcroze, Emile. 1942. Souvenirs, Notes et Critiques/Memories, Notes and Reflections. Neuchâtel: Editions Victor Attinger.

- Jaques-Dalcroze, Emile. 1945. La Musique et Nous. Geneva: Perret-Gentil.

- Juntunen, M.-L. 2002. From the Bodily Experience Towards the Internalized Musical Understanding: How the Dalcroze Master Teachers Articulate Their Pedagogical Content Knowledge of the Approach. In 25th Biennial World Conference and Music Festival, ISME: Proceedings.

- Juntunen, M.-L., and H. Westerlund. 2011. “The Legacy of Music Education Methods in Teacher Education: The Metanarrative of Dalcroze Eurhythmics as a Case.” Research Studies in Music Education 33 (1): 47–58.

- Kamberelis, G., and G. Dimitriadis. 2011. “Focus Groups: Contingent Articulations of Pedagogy, Politics, and Inquiry.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th ed., edited by N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln, 545–561. London: Sage.

- Kotyk, M. 2009. “Musical Moves.” The Canadian Dalcroze Society Journal 3 (2): 2–6.

- Leavy, Patricia. 2009. Method Meets art. New York and London: The Guildford Press.

- Lee, M. 2003. Dalcroze by Any Other Name: Eurhythmics in Early Modern Theatre and Dance." Ph.D. Thesis. Texas Technical University.

- Martens, Frederick H. 1919. Violin Mastery: Talks with Master Violinists and Teachers. New York: Frederick A. Stokes..

- Mathieu, Louise. 2013. “Dalcroze Eurhythmics in the 21st Century: Issues, Trends and Perspectives”. In Movements in Music Education: First International Conference of Dalcroze Studies, Coventry, United Kingdom, 24–26 July.

- Mead, Andrew. 1999. “Bodily Hearing: Physiological Metaphors and Musical Understanding.” Journal of Music Theory 43 (1): 1–19.

- Nelson, Robin. 2013. Practice as Research in the Arts: Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pallaro, Patrizia. 1999. Authentic Movement. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Phelan, Helen. 2018. Interview with the author.

- Pierce, Alexandra. 2010. Deepening Musical Performance Through Movement. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- Pucihar, I., and B. R. Pance. 2014. “Bodily Movement as Inseparable Part Of Musical Activities/Telesni gib kot Nelocljivi del Glasbenih Dejavnosti.” Glasbeno - Pedagoski Zbornik Akademije za Glasbo v Ljubljani 20: 93–111.

- Roland, David. 1994. “How Professional Performers Manage Performance Anxiety.” Research Studies in Music Education 2 (1): 25–35.

- Sheets-Johnstone, Maxine. 1981. “Thinking in Movement.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 39: 399–408.

- Shehan-Campbell, Patricia K. 1987. “Movement: The Heart of Music.” Music Educators Journal 74 (3): 24–30.

- Shusterman, Richard. 2000. Performing Live: Alternatives for the Ends of art. London: Cornell University Press.

- Shusterman, Richard. 2008. Body Consciousness: A Philosophy of Mindfulness and Somaesthetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Small, Christopher. 1980. Music-Society-Education. 2nd ed. London: John Calder.

- Stadler, E. 1965. “Jaques-Dalcroze et Adolphe Appia.” In Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, edited by F. Martin. Neuchâtel: La Baconnière.