ABSTRACT

This study explores music teachers’ beliefs of student agency in whole-class playing and investigates what characterises student agency through teachers’ values, actions and observations within this unique multimodal and -dimensional learning environment. Our abductive analysis of 11 interviews reveals that the role of teacher support is significant in enacting students’ agency. This study provides insights into student agency through the eyes and actions of teachers within the context of whole-class playing and suggests that the enactment of different aspects of student agency is an essential feature necessary for whole-class playing to succeed.

Introduction

Spruce, Marie Stanley, and Li (Citation2021) highlight teachers’ belief systems about the nature of music and music educational knowledge, about what it is to be a learner, teacher and musician, and about the most effective pedagogical relationships within music educational settings play a significant role in how they teach. Teachers’ beliefs affect their behaviour, which influences their students’ learning and further reinforces their own belief systems (Turner, Christensen, and Meyer Citation2009). Teachers’ beliefs and behaviour can also be expected to impact the enactment of student agency. To date, a limited amount of research has investigated whole-class playing as a forum for student agency using teachers’ beliefs. In the present study, we explore music teachers’ beliefs on students’ agency in whole-class playing to gain a better understanding of the potential that whole-class playing can offer for students’ agency within and potentially beyond music education.

The study was conducted in Finland, where the national core curriculum for basic education emphasises a learner-centred approach (Juntunen et al. Citation2014). In the Finnish curriculum, music is presented as an opportunity for musical activities and methods to promote not only musical but also social skills, well-being, imagination and cultural understanding (Finnish National Agency for Education Citation2016). An important method in Finnish music education is whole class playing (WCP) which involves every student in a classroom playing different instruments together in music lessons as a part of the timetabled curriculum. WCP in Finnish music education, for example, does not offer private instrumental tuition but involves every student, despite their perceived skills, to play music as a group by exploring different instruments, musical styles, relationships and ways of participating in the mainstream music classroom. Moreover, Finnish students are encouraged to work with different instruments, rather than developing mastery of one instrument alone. WCP is akin to rhythmic music pedagogy (RMP) as both approaches promote collective, embodied engagement with music through the strategic use of voice, body and percussion instruments (Hauge Citation2012). In addition to WCP and RMP, whole-class ensemble tuition programme currently underway in English schools supplements classroom-based music education offering all pupils new musical experiences and the opportunities to learn musical instruments (Fautley and Daubney Citation2019). The goal of these approaches is to actively bring a whole class of students through music to experience entrainment, that is being together ‘in the moment’ and playing at the same time (Clayton Citation2012). Entrainment is a complex interactive process among people encompassing not only an individual’s metric perception and coordination and the coordination of individuals in a group, but also negotiations of power relations and an ability to adapt to both musical and social entities by the means of music.

Whole-class playing is, however, challenging for teachers and students as it calls for engaging and actively participating in the exploration of something that is musically and socially unknown (Juntunen et al. Citation2014). For teachers, it requires a high level of musical competence, knowledge of pedagogical approaches and the ability to pay attention to the whole class of students within a unique, constantly changing and intensive situation (Schiavio, K’ssner, and Williamon Citation2020). For students, it requires not only social or complex coincidental cognitive skills, such as perception, symbolic activity and motor performance, but also active participation and the ability to adapt their behaviours to musical entirety in synchrony with others (Clayton Citation2012; Karlsen Citation2011). While the importance of students’ active participation and agency in different learning environments has become increasingly acknowledged in the twenty-first century (Vaughn Citation2020), student agency in music education has received little attention to date.

Moreover, music education is significantly limited with the current emphasis on musical outcomes and, therefore, has resulted in one-sided research (Karlsen Citation2011) that fails to develop a deeper understanding of learners’ experiences and teaching practices. In this study, we explore music teachers’ beliefs as a way to gain insights into students’ agency in whole-class playing. In another study, we focus on student experiences of their agency in WCP. However, as teachers are key participants in the formation of student agency (Ruohotie-Lyhty and Moate, Citation2015 ) this study uses teacher beliefs (Turner, Christensen, and Meyer Citation2009) as a starting point for our exploration. The pedagogical values that teachers hold, for example, provide insight into their beliefs about what students are capable of and how the relationship between their subject and the students can be developed. The actions that teachers implement in classrooms provide insight into their enacted beliefs with regard to what is possible within this environment, with these students. The observations of teachers provide insight into the ongoing interactions in classrooms, how students are participating, interacting with each other, with the teacher and with the subject (Gallimore and Tharp Citation1990). Therefore, in the present study, we explore music teachers’ beliefs about students’ agency in whole-class playing.

Student agency from two theoretical perspectives

In recent years, the concept of agency has provided educational researchers with an important conceptual tool with which to examine different aspects of and relationships between learning, teacher and student experiences and development (Jääskelä et al. Citation2020; Vaughn Citation2020). In this study, our thinking was informed by two theoretical perspectives, socio-cognitive and sociocultural, on agency in order to explore student agency as an individual, relational, collective and environmental phenomenon in educational settings (see ).

Table 1. Key characteristics of student agency from two theoretical perspectives.

Socio-cognitive approach

Within the framework of socio-cognitive psychology, the agency is often presented as an individual property which includes competency, determination, intentionality, self-efficacy, motivation, self-management and self-esteem. From this perspective, self-efficacy is the most central and forms the foundation of human agency. Beliefs of being able to produce desired effects by one’s actions is a key element in setting goals and evaluating the outcomes, which similarly plays an influential role in motivation that is central in learning (Bandura Citation1986, Citation1999).

Socio-cognitive theory approaches agency highlighting the individual capacity to influence one’s functioning and life circumstances, and where other people’s acts are seen as means to secure desired outcomes. If people are acting collectively on a shared belief then reaching a goal depends on their collective beliefs about their collective capabilities. Socio-cognitive approach recognises three types of environments of imposed, selected and constructed and which affect the exercise of the level of personal agency meaning that the experience of the environment depends on how people act and behave in it (Bandura Citation1999). Research highlights, however, that within educational settings individual capacity is significantly influenced by teachers’ beliefs and actions in relation to students. This relationship is a central consideration from a sociocultural perspective and perhaps one reason why socio-cognitive and sociocultural theorisations have been regarded as complementary (cf. Jääskelä et al. Citation2020).

Sociocultural approach

Research based on Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) sociocultural theory suggests that agency refers to an individual’s experience of their capacity as a learner, which constantly evolves in interaction with others and actively participating in learning environments that are conducive to facilitating agency (Vaughn Citation2020). Sociocultural researchers often draw on Emirbayer and Mische’s (Citation1998) conceptualisation of agency as a combination of time and context where individuals’ agentic action in the present is realised through experiences and understanding as well as orientation toward the future to an anticipated, usually primarily social context. Furthermore, they acknowledge Biesta and Tedder’s (Citation2007) argument that agency should not be considered as a power that individuals possess and utilise but rather something that is achieved through engagment with unique temporal-relational contexts that vary along with their environments as available resources and structural factors change.

A range of studies has demonstrated the value of paying careful attention to teachers’ and students’ active participation in education. Studies on student agency, for example, suggest that effective learning and improvement of performance result from learners’ active roles in learning processes, such as agency at an individual but also at a collective level (Vaughn Citation2020). Moreover, studies indicate that effective teaching practices can help to increase the agency of a student and improve their profound learning (Niemi et al. Citation2015; Ruohotie-Lyhty and Moate Citation2015 ). Recent research indicates that student agency in secondary and tertiary educational settings is affected by relational, individual and participatory resources, such as interest, capacity beliefs, self-efficacy, experiences of trust, support from teacher and peers and opportunities to influence, make choices, and actively participate (Jääskelä et al. Citation2020). The current study employs this multidimensional conceptualisation of person-/subject-centred approach to student agency as it recognises the interplay of individual and sociocultural aspects of learning (Jääskelä et al. Citation2020).

Socio-musical approach

Karlsen’s (Citation2011) sociologically inspired work contributes to the perspectives outlined above but drawing attention to the notion of musical agency. The musical agency is seen as a capacity to act ‘in and through’ music, which encompasses the unique ways people use music to construct themselves in relation to others (Karlsen Citation2011). Although the quality of musical agency is regarded as always relational, the individual dimension of the musical agency includes aspects of using music to structure and extend one’s position in the world whereas the collective dimension of the musical agency includes different aspects of collective musical use and action, which leans on Small’s (Citation1998) philosophy of musicking. Small emphasises the social nature of music as a ‘human encounter’ in the sense that the meaning of the music lies not only in musical works, but especially in non-musical outcomes like the relationships that are established by the musical act. Similarly, Juntunen et al. (Citation2014) address how joint playing of music can be a possible path to mutual commitment and world-making, which leads to more meaningful learning experiences.

In the work of Ruud (Citation2020), the musical agency is conceptualised as relational, being aware of not only one’s personal and material resources but also possibilities for action in the immediate surroundings. Furthermore, he discusses how both music and its material aspects lead the direction in musical interactions. Thus, whole-class playing can be seen as a platform for an individual to be part of a larger social and musical entity where they can recognise and investigate their own way of acting and engaging in a multimodal dialogue with respect to music, instruments and the group, including the teacher.

brings together the key characteristics of student agency from these different theoretical perspectives. The aim of this study is to examine whether teacher beliefs regarding student agency in WCP can contribute to and extend conceptualisations of student agency as a key area for development within and beyond music education.

The aim of the study

In the present study, we use teacher beliefs to investigate what characterises students’ agency in whole-class playing. The following research questions focused more specifically on:

What characteristics of student agency are highlighted in teachers’ values?

What characteristics of student agency are highlighted in teacher actions?

What characteristics of student agency are highlighted in teacher observations?

Methodology

Participants and procedure

The participants in this study are teachers (N = 11) who teach music in grades 1–6 in Finnish basic education. To ensure the diversity of the sample the participants (2 male; 9 female) ranged from the ages of 28–55 with work experience of between 2 and 25 years. Three were qualified class teachers, four were qualified as music teachers and four were qualified as both class and music teachers. Before contacting the participants, permission was obtained from the town authorities. Voluntary participants were recruited mainly using social media or by directly e-mailing teachers at different schools. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, methods and ethical commitments, and informed consent was signed prior to interviews in October 2020.

Before the interviews, the teachers were asked to complete a short questionnaire on their backgrounds including their gender, age, education and work experience. The semi-structured interviews (Tracy and Hinrichs Citation2017) were based on the theorisations of student and musical agency outlined above, and they provided a space for the participants to share their knowledge, perspectives and experiences of whole-class playing. An example of an interview question is the following: In your opinion, what affects how an individual student participates in whole-class playing? All the interview questions are presented in Appendix 1.

The average length of interviews was 40 min (variation from 30–60 min). Interviews were conducted remotely on a one-to-one basis by the first author via Zoom or Microsoft Teams. The recorded interviews were transcribed and anonymised. The final dataset included 260 pages of transcribed text (double spaced in font 12).

Data analysis

An abductive approach (Timmermans and Tavory Citation2012) was used in the qualitative content analysis of the transcribed interviews as this approach allowed for the interplay between the data and existing theories as well as the creative inferential process of extending theoretical perspectives. The goal of the qualitative content analysis (Vaismoradi, Turunen, and Bondas Citation2013) was to understand what teachers believe about student agency in the WCP context based on their experiences of WCP.

The overall analysis consisted of three rounds. The first round of analysis focused on identifying whether and how manifestations of agency were present in the data and their relations to theoretical perspectives of student agency and musical agency. The first round of analysis combined a careful reading of the transcripts based on the different theoretical perspectives with in vivo coding. By in vivo coding we mean the form of coding in qualitative analysis that emphasises the actual spoken words of participants and aims at understanding the nuanced meanings, ideas and contexts (Saldaña Citation2016). The first round was double-coded by two different coders for intercoder reliability (Lombard, Snyder-Duch, and Bracken Citation2002), with some changes and corrections made in between the coding rounds based on the discussion of the coders. Intercoder agreement among the categorisations was high at 93.75% and the remaining 6.25% were recategorised by the coders cooperatively based on their discussions.

Despite the congruence with the existing theory of agency and intercoder reliability, the first round of analysis did not explain the core of some in vivo codes, for example, the relations between theoretical perspectives or relations between activity and agency of students. Therefore, the second round of the analysis was inductive in order to enable the findings to better reflect the data, to identify other main themes, sub-themes and meanings in the transcribed interviews and to modify the main themes, sub-themes and meanings by adding or combining them. Based on the data, one additional sub-theme, entrainment, was identified and placed under the sub-theme of the collective dimension of musical agency to replace synchrony that exists in the theoretical notion of musical agency. Appendix 2 represents Tables A1 and A2 as a phase of the analysis after two rounds with emerged themes, sub-themes and meanings concerning manifestations of agency and their relations to theoretical perspectives of student agency and musical agency. The final step of rounds one and two was to examine the main themes for illumination of how different aspects of the agency are related to the teachers’ beliefs of whole-class playing. The third round of analysis was to identify whether and how the characteristics of student agency were related to teacher beliefs and values, their active engagment with students and observations about the ongoing interactions in the classroom.

Findings

The findings based on the analysis are presented through three levels of the teacher belief system; teacher beliefs and values, teacher actions and teacher observations, that reveal what teachers believe about what characterises student agency in the WCP context. Teacher beliefs and values include the understanding of student agency in WCP that guide their actions, and finally, observations provide insights into the ongoing interactions in the classroom as teachers observe children’s act and give meanings to what they see. Together these levels provide insights into the multifaceted notions of agency in whole-class playing.

Teacher beliefs and values

Teachers emphasised the importance of students’ interest and competence beliefs in whole-class playing. Interest was seen as a multifaceted phenomenon affected by the previous experiences and history of a student, musical identity, self-efficacy, competence beliefs and the experience of possibilities to influence the song to be played or choose the instrument. When discussing competence beliefs, teachers highlighted the importance of effective instruction in perceiving music and knowing how to play an instrument so that students would know the nature of the task and that the goal would be achievable for them. Teachers also described the personal resources students have to draw on in order to participate as being a complex aspect. These personal resources were connected to students’ overall self-confidence and the individuals’ previous experiences. Teachers acknowledged significant diversity that could be part of a group of students when it comes to their sociocultural, physical and temporal starting points. These aspects included previous experiences of whole-class playing, alertness, hunger, background of a student, possible illnesses, medication and diagnoses are pertinent to the present moment, as noted in the teachers’ comments:

Teacher 7: The whole context such like previous experiences, problems, alertness and self-efficacy that a student carries into the classroom has a significant impact on how he starts to work.

Teacher 6: A student might have an illness or a diagnose that affects how he is able to participate.

Teacher 10: It is good to acknowledge where the students come from, are they fine, have they got food. . . Then there are students who don’t necessarily have the model at home that music exists and can be listened to. . . And then there are students who have a broad knowledge of music if in their homes people play, sing and are interested in music . . . So this is the field we are acting in.

In addition to the starting point of a student playing an important role, the participants regarded environmental conditions as significant in how and who would even have the opportunity to be agentic, as the excerpts below demonstrate:

Teacher 5: Everyone should have even an opportunity to enjoy and be part of it.

Teacher 7: It plays a significant role what instruments we have; how many and how the students are able to participate in the moment. Who gets to play and who does not, and why.

Teacher 8: We might not have the space or the instruments we would need so that everyone would be able to participate.

Power relations among the students and the teacher were also highlighted by the teachers while emphasising the students’ experiences of trust and emotional support from the teacher and peers. Group dynamics, tense relationships, the working culture of a class and the role of an individual were regarded as significant factors in learning situations. Teachers acknowledged the importance of the experience of trust in whole-class playing situations, which they referred to as a safe atmosphere where students could ‘feel accepted as who they are’ (Teachers 4, 6 and 11) and ‘work without the fear of making mistakes’ (Teacher 3, 4 and 9); many teachers saw this as the starting point for creating the platform for whole-class playing, as Teacher 5 states:

If there is a lot of bullying and fear there is no way they could do anything as demanding as playing together.

Moreover, teachers perceived the importance of shared musical experiences and how this musical aspect of whole-class playing could incorporate all individuals in the class into one entity. Music was described to be ‘a ‘glue’ that helps to form a collective one as music invites everyone to play together and to listen to each other’ (Teacher 9) and how ‘the pulse from the metronome is not enough because we need to listen and find our dynamic shared tempo’ (Teacher 3). These extracts provide insights into how whole-class playing is a combination of perceiving music and actively endeavouring to adapt one’s own musical activity to the musical entity that is taking shape in the classroom as the feedback of succeeding comes straight from the music itself. In this sense, entrainment is a critical feature that profoundly connects the outside with the inside to the extent that there is no sense of boundary. Furthermore, whole-class playing was regarded as a ‘shared emotional experience’ (Teachers 6, 7 and 10), an opportunity to identify how one feels, and as a highly social act:

Teacher 9: I think interactional skills play a more significant role than musical skills in whole-class playing.

Teacher 11: In my opinion successful whole-class playing is an indication of the ability to listen to others and take others into account.

All of these extracts point to the beliefs, values and the insights teachers have regarding what kind of learning is valuable, ethical considerations, how they relate to their students and what values they regard as intrinsically part of joint music making. These beliefs suggest that student agency from the teacher perspective is an ongoing negotiation between the individual resources students bring to the classroom, the collective resources the community can generate, and the relationship with the teacher. The characteristics outlined here point to the resources and aspects of student agency teachers believe are important in the WCP context. The following section outlines in more detail how these beliefs and values inform teacher action as they curate WCP in music education.

Teacher actions

As teachers beliefs and values guide their actions (Turner, Christensen, and Meyer Citation2009), the ways they engage with their students can be regarded as their enacted beliefs that provide us another lens to view student agency. The teachers provided insights into how they supported their students’ interest, for example, by asking students’ opinions of songs to be played, choosing a song they knew their students liked, involving students to plan the lessons, providing clear goals for action (‘just playing’ vs. making a music video or a gig at school festival), letting students choose which instrument to play, or by first teaching students an easy riff in order to be able to participate in whole-class playing. Each teacher participant described their role and supportive acts concerning students’ learning in the whole-class playing, and the analysis identified many descriptions of support provided by the teachers directed either toward student’s interest, feeling of trust and their sense of being capable of or musical aspects so that students would find their own ways of acting and participating. Their descriptions of how they usually build whole-class playing situations provided many examples of how they seek to support and give instructions in a musical way. The teachers supported their students to perceive music by using visual auxiliary materials, adding different levels or instruments one by one, using backing tracks, guiding students to listen, accompanying them with an instrument and showing or counting out loud to maintain the tempo (supporting entrainment). Teachers 2 and 3 explained how they achieved this:

Teacher 2: There is at least one element that everyone learns to play, and we do that in the beginning of rehearsing a new song. And by learning that element, we also learn the structure of a song which is always the same no matter if you sing it or play the song. . . . And after we have learned to play one element, it is easier to keep the whole group engaged continuously. . . . I usually have the structure of the song on the whiteboard where I can show stuff and maintain the tempo. I show where we are going and maybe sing the melody at the same time.

Teacher 3: Well, now we get to the core of whole-class playing and the significance of whole-class playing which is to listen to each other. . . . I do a lot of rhythmic practices with my students so that it’s not a new thing for students to keep up together, listen to each other, and do the same with everyone.

The environmental aspects highlight what teachers believe students need to support their agency. Teachers described their actions by being strict in placing students and guiding the physical transition to the instruments to avoid chaos, by using the class or rooms nearby in ‘creating spaces for concentrating’ (Teacher 1) or ‘dividing the class in smaller groups where students can feel safer to rehearse to play something new’ (Teacher 3). All participants described how they rarely stay in one place while they teach whole-class playing but how they consciously choose the physical spot that serves the students’ supportive needs; moving around the class helping individuals, leading the start many times from the front of the class to keep everyone engaged, or hopping from one instrument to another to support entrainment, that is maintaining everyone ‘in the moment’ by the means of social and musical impulse.

The teacher actions outlined here indicate how teachers prepare for and participate in the creation and maintenance of WCP. Moreover, the findings provide insight into the ongoing interaction between teacher and students, the way teachers guide and facilitate student participation and provide support towards their individual and collective resources of agency. The data analysis also indicates how the teachers carefully observe and respond to their students during the realisation of WCP, as outlined in the final theme.

Teacher observations

Whereas teacher values are enduring across classrooms and teacher actions can be regarded as their enacted beliefs, teacher observations can be regarded as a form of ‘sensitised beliefs’ that focus on individual and collective levels in the real time of the classroom, providing insights into consequences and effects of action, and the adjustments teachers make to response their students’ agency. If the instruction was not clear or if the task was too hard, the teachers explained in their experience the students would become resistant and not participate in whole-class playing. Every participant had experiences of difficult and challenging situations where they had felt clueless with a resistant student or a class they just did not manage to get to play together. Teachers described how the students begin to take responsibility for their participation when they feel safe, they are able to participate, when the task is achievable and not only offers experiences of success but also challenges. The descriptions of participatory aspects of agency as perceived by the teachers provide insights into how musical aspects like playing, perceiving the music and the experience of entrainment connect to the sense of being capable, being safe and belonging, as illustrated in the following extracts:

Teacher 10: I can see the enjoyment from their faces when they sound like really good and when they realise they are part of it.

Teacher 11: What engages a student in whole-class playing is when he feels and hears that now this playing of ours goes together and now we are in the same . . . and, ‘hey, now I got those beats in the right place’ and ‘now I managed to change that chord on time.’

Supporting students in perceiving music or playing instruments was described as increasing students’ competence beliefs, self-efficacy and interest toward things to be learned and, hence, enhancing the possibilities to participate. The teachers noted that aspects that enabled participation increased student engagement in whole-class playing. Different aspects of identity were also recognised as strongly influencing students’ motivation and readiness to participate whole-class playing since it affected how they identified with a certain piece of music. The comments from the participating teachers, however, indicate how the learning environment can play a significant role in orienting students to the music. As Teacher 9 points out:

Students might react like ‘that kids’ song is so stupid!’ but if we are going to perform that song in a kindergarten, the older students might become totally infatuated with the song.

The participants noted how through the music, playing together and entrainment the way opens to not only exploring social relationships but also affirming and exploring collective identity. Teachers often emphasised that once the playing starts, it often engages even restless students to participate because there is no room for anything other than being present in the moment if they aim to be in synchrony with others. Teacher 8 described how a student would refuse to play any instrument but as the playing started, the student immediately started to physically ‘sulk in tempo’. The participants also underlined music as a connector for establishing a collective identity as they described for example how whole-class playing reaches the next level when a class has composed its own song (Teachers 8 and 11), how the hard work of the class and a successful gig at school festival made students united (Teachers 1, 5, 8, 9 and 11) or how there have been smaller collectives, bands, that have engaged in certain genres and performed in school band festivals. Moreover, Teachers 5 and 11 emphasised how whole-class playing ‘strongly mirrors the social skills of the class’ and Teacher 2 described the situation where a class of students found a new way of being together through whole-class playing:

They wanted to play that song all the time together, many hours. . . . They had this tension in the class all the time and students were stressed because of that. It was like ‘we can do this together and we are able to do this together,’ and there was this ease of doing.

Teacher observations as a form of ‘sensitised beliefs’ provide insight into the dynamic, relational and contextual nature of student agency. These extracts call attention to the non-musical outcomes of whole-class playing as the social aspect is merged through the musical act. The key seems to be how the group learns to listen to each other, how they take responsibility in the interactions with each other, and how they explore and affirm relationships through collaborative musical action. This is a notable finding because here the musical aspects intertwine reciprocally with the relational and participatory resources of agency, like safe atmosphere, peer support and participation activity, in the most significant way.

Discussion

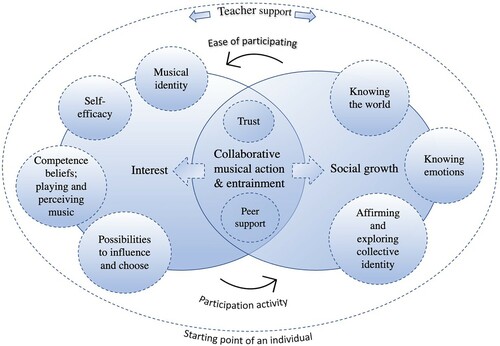

The study examined teacher beliefs of students’ agency in WCP by exploring characteristics of student agency in different levels of teacher belief system; teacher beliefs and values, actions and observations. In response to the first research questions about what characteristics of student agency are highlighted in teacher values, the findings suggest that student agency in WCP is inextricably associated with students’ diverse sociocultural, physical and temporal starting points, and with the environmental considerations that either facilitate or limit the chance to be agentic. Teachers believe students’ interest play a crucial role in successful WCP but they also acknowledge how motivation is a sum of several multifaceted factors that are intrinsically central in student agency, such as competence beliefs in perceiving music and playing an instrument, self-efficacy, musical identity and possibilities to influence and choose. Values of safe atmosphere, providing students social affirmation and the experiences of belonging through music emerged throughout the interviews. The enacted beliefs of teachers, the focus of research question two, highlight student agency in WCP as highly interactive and relational, where teachers’ supportive multimodal actions directed towards the different aspects of students’ interest and trust enable students’ participation to joint music making. The findings to the third research question, through teachers’ sensitised beliefs, draw attention to the challenges of resistance, aspects enabling students’ participation, non-musical social outcomes of joint musical action and highly agentic special characteristics of student agency in WCP, entrainment, which is active being, feeling and sharing the moment collectively by the means of music. These findings highlight the value of examining teacher beliefs within the specific context of described WCP as a multimodal and multidimensional platform where, through participation and the experience of entrainment, the way opens to strengthen beliefs in one’s ability and capacity as a learner and establishing the collective by creating a safe atmosphere, social cohesion and the possibility to explore or experience new collective ways of being by the means of music. Consequently, our findings emphasise how WCP cannot be understood only by exerting individual agency within a shared environment, but goes beyond the individual without losing the individual. Above all, the findings highlight that teachers believe the enactment of different aspects of students’ agency as essential features for whole-class playing to succeed. The synthesis of the aspects and the process of the development of student agency in WCP are illustrated in . At the bottom of is the starting point of an individual, which forms the foundation for an individual to approach whole-class playing as a learning environment, and the circle that surrounds the aspects of agency illustrates how teacher support affects every aspect of student agency in WCP.

Figure 1. Synthesis of different aspects and the process of student agency in whole-class playing through teacher beliefs.

The findings indicate how individual, relational and participatory resources of student agency connects with and through musical aspects of agency and how the role of teacher support is significant in bringing students through music into collective exploration socially and musically. The teacher beliefs reported in this study provide insight into how they see themselves as facilitators who support and enable the students to find individual ways to participate and create the path step-by-step toward the opportunity of entrainment for the entire collective. Therefore, the key finding suggested by this study is the profound relationship between teacher beliefs meaning their values, enacted and as sensors, in the development of student agency. Furthermore, the high degree of pedagogical sensitivity required of teachers could be framed as ‘pedagogical entrainment’ on the basis of this study. Pedagogical entrainment highlights teacher ability of being adjustable and responsive when encountering students from diverse starting points, reading the musical and social situations and taking actions in guiding their students towards and through entrainment. Thus, our study provides further insights into how teachers’ belief systems drive the way teachers support their students (Gallimore and Tharp Citation1990; Spruce, Marie Stanley, and Li Citation2021; Turner, Christensen, and Meyer Citation2009), which emerges as an incremental element for increasing student agency (Niemi et al. Citation2015; Ruohotie-Lyhty and Moate Citation2015).

This study highlights the role of entrainment, a complex interactive process among people that points at the ability to adapt one’s behaviour to social and musical entities and perceiving oneself as a part of an entity by means of music (Clayton Citation2012). It is a profound way of being present, in the moment and in time collectively. The earlier conceptualisations have recognised synchrony (Karlsen Citation2011) as a part of musical agency, entrainment as a part of student agency and as a way of understanding student agency are new. This study clearly shows how playing together and the experience of entrainment open the way not only to exploring the social relationships and establishing collective, but also to recognising and investigating an individual’s unique way of acting and participating through music. Thus, entrainment is a key factor in the success of WCP. The findings support the understanding of music as a ‘human encounter’ wherein a joint playing of music can create mutual commitment (Hauge Citation2012; Juntunen et al. Citation2014; Karlsen Citation2011; Small Citation1998). Furthermore, the current study contributes to explaining how social affirmation and establishment, equivalent with experience of trust and significance of peer support recognised in other studies of educational settings (Jääskelä et al. Citation2020; Niemi et al. Citation2015), develops in WCP by clarifying the realisation of how making music together is dependent on individuals investing in the forming of the collective ‘one’ through entrainment.

Our findings emphasise the diversity that could be part of a group of students, including not only the present physical sensations, such as hunger, alertness and diagnoses, but also the sociocultural and temporal context, such as previous experiences and starting points to social interaction and music. We suggest that these aspects need to be carefully considered as they significantly affect the enactment of students’ agency, as the individuals’ agentic action in the present is realised through bringing their experiences and understanding from the past as well as orientation toward the future into a certain context (Biesta and Tedder Citation2007; Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998). Moreover, this study suggests that not only the earlier aspirations of the past of the individual form the present and prefigure the future, but also the concrete and physical considerations and environmental considerations are notable aspects of agency here-and-now. We would thus argue that student and musical agency should be reconceptualised to acknowledge the importance of the immediate physical environment in educational settings.

Implications

Teacher beliefs about student agency can provide new insights. After all, teachers spend a considerable time with their students, and how teachers work has a significant effect on the development of student agency. Music teachers in particular have to negotiate and come alongside students in the real time of the classroom in a way that other subject teachers don’t have to. As illustrated in , teacher support effects every aspect of student agency in WCP, and through ‘pedagogical entrainment’ needed in WCP, the teacher should be able to discover whether the support should be directed to individual, participatory, relational or musical aspects since they blend with each other. The findings highlight the potential of entrainment as special characteristics of student agency in WCP, by its musical and social aspects, as it is a very effective tool for profound participation and belonging. This understanding should help to create new pedagogical approaches to support and shape student agency in music educational contexts, which can insure the relevance of music as an essential school subject in the future.

Limitations and future directions

The current study has certain limitations that need to be considered before making any generalisations. First, while the interviews shared the beliefs of the participating teachers, future research could include observations to examine how understanding emerges in practice. Second, a larger sample size would provide a more diverse picture of the beliefs and perspectives of music educators. Finally, the study was conducted in a Finnish educational context, and to see whether the findings are reflective of other teachers, future research should include teachers in different countries. However, our study offers a pragmatic tool with which music educators can reflect upon not only their work but also their personal relations to music. Furthermore, to gain a better understanding of the full potential of whole-class playing, the experiences and thoughts of the students should be examined.

Conclusions

This study invites us to acknowledge how teachers’ values are inseparable part of the activities they curate with their students, and how teachers’ role is central in the formation of students’ agency. Furthermore, the findings help us, as music educators, to recognise what affordances whole-class playing has to offer for children’s agency, so that we could more consciously develop new pedagogies to support our students. Based on our findings, we can conclude that, in WCP, the collective, relational and participatory aspects of student agency appear to precede somewhat the individual elements. In a way, in a joint musical activity, ‘being part of something’ allows ‘being someone’. This characteristic feature of whole-class playing may hold relevance for understanding how this activity may support the development of students’ agency and social growth.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to our colleagues Päivikki Jääskelä and Emily Carlson, who provided helpful comments on the earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eveliina Stolp

Eveliina Stolp is a university teacher and a doctoral researcher at the Department of Teacher Education, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research focus is on the practical music education at schools, whole-class playing, teaching and the construct of both student agency and musical agency.

Josephine Moate

Josephine Moate is a docent and senior lecturer in education based at the Department of Teacher Education, University of Jyväskylä. Her research includes longitudinal studies on student teacher development, explorations of educational culture and mediated participation in education.

Suvi Saarikallio

Suvi Saarikallio is an Associate Professor of Music Education and Docent of Psychology at the Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research focuses on music as a medium for emotional self-regulation and youth development in contexts ranging from everyday life to education and clinical care.

Eija Pakarinen

Eija Pakarinen is an Associate Professor of Education at the Department of Teacher Education, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research foci include teacher–child interactions, teacher–student relationships and home–school collaboration in relation to children’s motivational, academic and socio-emotional outcomes.

Marja-Kristiina Lerkkanen

Marja-Kristiina Lerkkanen is a Professor of Education at the Department of Teacher Education, the University of Jyväskylä, Finland and Professor II at the University of Stavanger, Norway. She has extensive expertise in directing several longitudinal studies concerning learning, teaching, motivation, teacher–student interaction, teacher education and teachers’ well-being.

References

- Bandura, Albert. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, Albert. 1999. “Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective.” Asian Journal of Social Psychology 2 (1): 21–41. doi:10.1111/1467-839x.00024.

- Biesta, Gert, and Michael Tedder. 2007. “Agency and Learning in the Lifecourse: Towards an Ecological Perspective.” Studies in the Education of Adults 39 (2): 132–149. doi:10.1080/02660830.2007.11661545.

- Clayton, Martin. 2012. “What is Entrainment? Definition and Applications in Musical Research.” Empirical Musicology Review 7 (1–2): 49–56. doi:10.18061/1811/52979.

- Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Ann Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294.

- Fautley, Martin, and Alison Daubney. 2019. “The whole class ensemble tuition programme in English schools – a brief introduction.” British Journal of Music Education 36 (03): 223–228. doi:10.1017/S0265051719000330.

- Finnish National Board of Education (EDUFI). 2016. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- Gallimore, Ronald, and Roland Tharp. 1990. “Teaching Mind in Society: Teaching, Schooling, and Literate Discourse.” Vygotsky and Education, 175–205. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139173674.009.

- Hauge, Torunn Bakken. 2012. “Rhythmic Music Pedagogy: A Scandinavian Approach to Music Education.” Journal of Pedagogy and Psychology “Signum Temporis” 5 (1): 4–22. doi:10.2478/v10195-011-0049-y.

- Jääskelä, Päivikki, Ville Heilala, Tommi Kärkkäinen, and Päivi Häkkinen. 2020. “Student Agency Analytics: Learning Analytics as a Tool for Analysing Student Agency in Higher Education.” Behaviour & Information Technology 40 (8): 1–19. doi:10.1080/0144929x.2020.1725130.

- Juntunen, Marja-Leena, Sidsel Karlsen, Anna Kuoppamäki, Tuulikki Laes, and Sari Muhonen. 2014. “Envisioning Imaginary Spaces for Musicking: Equipping Students for Leaping Into the Unexplored.” Music Education Research 16 (3): 251–266. doi:10.1080/14613808.2014.899333.

- Karlsen, Sidsel. 2011. “Using Musical Agency as a Lens: Researching Music Education from the Angle of Experience.” Research Studies in Music Education 33 (2): 107–121. doi:10.1177/1321103(11422005).

- Lombard, Matthew, Jennifer Snyder-Duch, and Cheryl Campanella Bracken. 2002. “Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability.” Human Communication Research 28 (4): 587–604. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x.

- Niemi, Reetta, Kristiina Kumpulainen, Lasse Lipponen, and Jaakko Hilppö. 2015. “Pupils’ Perspectives on the Lived Pedagogy of the Classroom.” Education 3-13 43 (6): 683–699. doi:10.1080/03004279.2013.859716.

- Ruohotie-Lyhty, Maria, and Josephine Moate. 2015. “Proactive and Reactive Dimensions of Life-Course Agency: Mapping Student Teachers’ Language Learning Experiences.” Language and Education 29 (1): 46–61. doi:10.1080/09500782.2014.927884.

- Ruud, Even. 2020. Toward a Sociology of Music Therapy: Musicking as a Cultural Immunogen. Dallas, TX: Barcelona Publishers.

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Schiavio, Andrea, Mats B. K’ssner, and Aaron Williamon. 2020. “Music Teachers’ Perspectives and Experiences of Ensemble and Learning Skills.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 291. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00291.

- Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. London: Wesleyan University Press.

- Spruce, Gary, Ann Marie Stanley, and Mo Li. 2021. “Music Teacher Professional Agency as Challenge to Music Education Policy.” Arts Education Policy Review 122 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1080/10632913.2020.1756020.

- Timmermans, Stefan, and Iddo Tavory. 2012. “Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis.” Sociological Theory 30 (3): 167–186. doi:10.1177/0735275112457914.

- Tracy, Sarah J., and Margaret M. Hinrichs. 2017. “Big Tent Criteria for Qualitative Quality.” The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, 1–10. doi:10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0016.

- Turner, Julianne C., Andrea Christensen, and Debra K. Meyer. 2009. “Teachers’ Beliefs About Student Learning and Motivation.” International Handbook of Research on Teachers and Teaching, 361–371. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-73317-3_23.

- Vaismoradi, Mojtaba, Hannele Turunen, and Terese Bondas. 2013. “Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis: Implications for Conducting a Qualitative Descriptive Study.” Nursing & Health Sciences 15 (3): 398–405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048.

- Vaughn, Margaret. 2020. “What is Student Agency and Why is It Needed Now More Than Ever?” Theory Into Practice 59 (2): 109–118. doi:10.1080/00405841.2019.1702393.

- Vygotsky, Lev. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Appendices

Appendix 1

The questions used in the interviews in this article are as follows:

What kind of experiences do you have of playing as a group in your personal life, and what kind of meanings do they have for you? In your opinion, what affects how an individual student participates in whole-class playing? In your opinion, what affects how a whole group of students starts to play together, and how is the whole-class playing situation built? How do you support an individual student and the whole group in the whole-class playing situation as a teacher? Is there something concerning whole-class playing we have forgotten to talk in addition to what we have discussed already? Is there something you want to mention/talk about?

Appendix 2

Table A1. Teacher beliefs about student agency in whole-class playing.

Table A2. Teacher beliefs about musical agency in whole-class playing.