ABSTRACT

The aim of, Jane’s, Soundwaves Early Childhood Music lead, and Karen’s, Early Childhood Studies lecturer, inquiry is to encourage new insights into how multiple relationalities and learning play out, throughout Soundwaves, an early childhood music education (ECME) programme. We work with Barad’s diffractive methodology to shape our auto-ethnography. With pens, sparkly bits, ribbons, glue and paper, we map the Soundwaves narrative. Caring ethics, for the human and more-than-human, runs throughout our research practices. (Re)turning, the data, posthuman and critical new materialist theory, the Soundwaves narrative is (re)told. Concerns the neo-liberal narrative had played us, were replaced, when noticing the gap between our organisations offered reassuring insights. In this gap, resisting the neo-liberal narrative, is ‘fleetingness’, which welcomes experimentation and play to learning opportunities and our collaboration. These insights are useful to those who wish to maintain the visibility of ECME and resist creating instrumentalised learning experiences, whilst growing the ECME workforce.

Introduction

The process of writing this paper has provided us, Jane, Soundwaves Early ChildhoodFootnote1 Music lead, and Karen, an Early Childhood Studies (ECS) lecturer, an opportunity to ponder the endless relationalities (Haraway Citation2016) entangled in and around Soundwaves. Soundwaves is an Early Childhood Music Education (ECME) project. Our intention in this inquiry is not to find truths or what works when those who work for an arts and cultural charity and university collaborate. Instead, we hope to ‘provoke new thoughts and theories’ (Cannon Citation2022, 10) about collaborating, being in relationship and the learning opportunities that emerge for Higher Education (HE) students in and around a music project.

We acknowledge the maxims associated with the neo-liberal narrative, individualism, competition and ‘businessisation’ (Bruce and Chew, quoted in Costas Batlle, Carr, and Brown Citation2018, 861), shape and govern our respective organisations (Young Citation2021) and how we are in collaboration. Whilst we cannot avoid these clutches, we turn to Massumi who encourages his readers to live with these maxims, and also ‘ … get creatively down and dirty in the field of play’ (Citation2018, 69). In her role as an academic, Karen has been inspired by her colleagues who work with the philosophies and theories of critical new materialism and post-humanism and is enthusiastic by the possibilities post-qualitative inquiry affords. Thus, as being and becoming post-qualitative researchers, this inquiry, has provided an opportunity for Karen to introduce Jane to some of these theories and philosophies and for them both to experiment, play and learn with Karen Barad’s, diffractive methodologies. It is our intention to amplify and re-pattern (Barad Citation2014) the entangled relationships and learning as Soundwaves plays out.

Soundwaves: an early childhood music education project

Since 2013 Take Art Ltd, an arts and cultural charity in south-west England, has designed and sourced funding for Soundwaves; a series of four Early Childhood Music Education (ECME) projects; these are funded by Youth Music and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Learning during the first project highlighted the necessity for workforce development. Initially this development focused on the current early yearsFootnote2 and ECME workforces. The aim of the fourth and current iteration of the music project is to grow both the current and future early years and ECME workforces. The University of Plymouth is a consistent and key collaborator in fulfilling this ambition.

Jane and Karen first met in person during the recruitment process for the early childhood music lead. Karen, in her role as Take Art trustee, was on the interview panel and Jane an interviewee who was appointed for the role. As the trustee representing early childhood on the board Karen would meet Jane to discuss music projects for young children, their parents and early years educators. Karen’s passion for artist involvement in settings, her role in the university, her knowledge of the City Council and the early years of settings in Plymouth led her to become a project partner.

Although it is only the final iteration of Soundwaves that states the ambition to collaborate with training and education providers, over the course of the four projects, Jane and Karen, have created a diverse range of opportunities for ECS students and music students to learn about young children’s musicality and music education. These include student internships and work-based learning placements where students work alongside a musician in an early years setting, attending professional development courses (on-line and face to face), attending and presenting at conferences, engaging in research as researcher and research participant, writing and presenting with academics and joining the music project steering group.

Before continuing we pause, to express, our appreciation, that we are ‘ part’ of the relational entanglement, with other humans and the more-than-human, as opportunities, practices and knowledge are made (Vu Citation2018). Thus, entangled in the Soundwaves narrative are the more-than-human, dominant discourses of education and our beliefs and theories about pedagogy, relationships and collaborations. Below we outline the education discourses, our beliefs and theories and acknowledge these are dispersed throughout the paper and our practices.

‘Readiness for work’ and ‘employability’

Over the past decades the neo-liberal philosophies and tentacles of ‘freedom, markets and economic liberalisation’ (Blond Citation2010, 19) have strengthened a hold over all phases of education. The economic drivers of quality, investment and returns (Dahlberg et al. Citation2013; Young Citation2021) view the ultimate purpose of education is to ready pupils and students for the workforce. A prepared and productive workforce will guarantee economic success and stability for both the individual and the country (Moss Citation2019; Sims Citation2017). From this economic perspective, the image of the pupil and student is as ‘a unit of economic potential’ (Moss Citation2019, 12), the educator as a technician (Dahlberg et al. Citation2013) delivering a standardised and ‘what works’ programme of study/curriculum. It is argued the standardisation practices and curriculum have led to learning becoming formulaic and instrumentalised (Sims Citation2017; Young Citation2021) resulting in shallow learning (Bunce and Bennett Citation2021).

Reinforcing the neo-liberal ambition, that universities supply a productive workforce, is how the success of a degree course is measured. Successful degree courses have a high number of students progressing into graduate jobs with good salaries. The emphasis on graduate jobs has led to the teaching of employability skills embedded into the curriculum of degree courses (Pegg et al. Citation2012). The fee-paying student, viewed as a consumer of their degree, also focuses on the end goal – good assignment grades, leading to a good degree, ensuring a graduate job with good pay (Bunce and Bennett Citation2021). In this educational context, students are less likely to appreciate the struggle and are likely to object to difficult content and different pedagogic approaches (Bunce and Bennett Citation2021), thus contributing to learning opportunities becoming shallow and formulaic.

Turning to collaborations and relationships

The academic in this context of economic liberalisation is viewed as a solitary entrepreneur who competes against others to fund and conduct research. A successful researcher is perceived as one who conducts world-class, dynamic responsive research, which produces world-leading knowledge and has an impact across the globe (UKRI Citation2023). On the one hand, economic liberalisation encourages individualism and competition, on the other hand, it advocates academics to collaborate with others, ‘to do’ entrepreneurship in a social, compassionate and ethical way (Barthold Citation2013). Although viewed as compassionate and ethical the neo-liberal social order generally creates and reinforces hierarchical relationships between organisations and people. Hierarchical relationships can position academics in a position of privilege and power, when working with personnel from external organisations, such as a charity. When conducting research to solve a problem the academic can be viewed as an expert (Ward and Wolf-Wendel Citation2000) to remedy a problem for those that are deficient in ability or knowledge.

Another contributing factor that reinforces the hierarchical relationships is the short-term nature of projects, otherwise, termed short-termism (Berg, Huijbens, and Larsen Citation2016; Young Citation2021). Some argue short-termism enables innovation, produces outcomes that are trailblazing and ensures value for money. However, short-termism can lead to predefined and fixed ways of building collaborations and relationships. Vintimilla Cristina and Berger’s (Citation2019) experimentation and ponderings with co-labour-a(c)tion encourage us to challenge and resist predefined ways of building collaborations and relationships. Instead, they encourage us to ‘dwell in relationships’ invite action and newness to a collaboration (Vintimilla Cristina and Berger Citation2019, 188). Roulston (Citation2021), offers an alternative to collaboration. She suggests fostering a critical relational scholarly community, which responds to and appreciates the connections between the human and more-than-human, fosters invitational pedagogies and a sharing economy where time is the currency (Roulston Citation2021). Both inquiries appreciate the multiplicity and vitality of relationships, collaborations and working together.

Alternative beliefs, pedagogy, relationships and collaborations

Neo-liberalism has seeped into most aspects of our lives and it can make it difficult to consider alternative ways of being and creating learning experiences (Sims Citation2017). Despite these challenges we appreciate it is necessary to take time to articulate our aspirations and beliefs that dwell with our pedagogic practices, relationships and collaborations. As a trainee teacher, early years teacher and now academic, Karen has felt and does feel constrained and silenced by these forces. Committed to resisting positioning those she works with as in deficit, passive, incomplete or a consumer, she turns to playing and experimenting with theory (Taguchi Citation2010). She views learners as players in the learning process, who bring with them ‘virtual backpacks of knowledges, skills and dispositions’ (Thomson and Hall Citation2008, 89). Her role, as a pedagogical player, is to resist the forces that silence and marginalise groups’ voices and knowledge and to co-create places and opportunities for experimentation, creativity, uncertainty and possibilities (Moss Citation2019). In these places, social justice is a key partner in the co-construction of stories, curriculum and knowledge. These are meaningful to the learners now and in the future.

Similarly, Jane approaches her pedagogic practices, as an ECM project lead, as a musician, as a teacher and as a researcher … , aspiring to create socially just authentic meaningful learning experiences where learners, both children and adults, are contributors in the learning process. She works with Young’s intention that learners’ ‘knowledge and experience should be respected on an equal footing, listened to and freed from imposed controls’ (Citation2021, 117). Her experiences suggest that when artists and educators come together their interactios are ‘intensely creative and deeply political’ (Clark Citation2012, 200) as children’s and adults’ knowledge, experiences and learning are valued and respected.

Our beliefs shape our relationships and how we collaborate in the making of learning opportunities and projects. Together we play the context of competition and short-termism, by inviting learning, trust, respect and love (Freire Citation1970) to our relationships and collaboration. We view each other and our knowledge, experiences and skills as complementary and mutually beneficial when working and learning together. Working and learning together is supportive and fascinating but can be uncomfortable when moments of uncertainty emerge.

We felt uncomfortableness and uncertainty when referring to the Soundwave’s ambition, ‘to grow the future workforce’. Our unease emerged from the concern that the music project aligns with the political neo-liberal discourse, as it could be viewed, as an intervention to prepare students for the future workforce. However, we are curious how learning opportunities that emerge in and around the music project come to realisation. Our curiosity motivated us to embark on this inquiry. By ‘deep hanging out’ (Jayne Citation2023; Powell and Somerville Citation2021) with our narratives, relational encounters, the data and posthuman and critical new materialist philosophies, a place to delve into and (re)turn and (re)tell our relational narratives, was created. Karen Barad’s diffractive methodology enables an affirmative reading (Murris and Bozalek Citation2019) of these narratives. Through ‘constructively and deconstructively (not destructively) (Barad Citation2014, 187) new patterns of understanding about our relational encounters and narratives emerged. These insights and understandings will be of interest to those who work in universities and collaborate with colleagues from other organisations who aspire to grow the ‘future ECME workforce’.

Joining us in the making of learning opportunities for music students and early childhood studies students, are other colleagues. presents the characters that joined us. We employ Rachel’s, Chloe’s and Louise’s real names as their names appear on the blog and they have provided written permission to include their names in this paper, while Michelle, Nora and Jo are pseudonyms.

Table 1. Characters and their roles in the Soundwaves narrative.

Methodology

We are weary and dissatisfied with research that separates the researcher from the research process and context and objectifies and extracts knowledge. Thus, we were pushed/pulled to employ Karen Barad’s (Citation2007) epistemological-ontological-ethical framework, agential realism, where ‘knowing, thinking, measuring, theorizing, and observing are material practices of intra-acting within and as part of the world’ (Barad Citation2007, 90). We welcome and appreciate our entangling in the making of ‘knowing’ and ‘practice/ing’ with the human and more-than-human subjects (Murris and Bozalek Citation2019; Snaza et al. Citation2014). To uncover, different versions of our relationships and relational encounters entangled in our and the Soundwaves narratives Karen Barad’s diffractive methodology is put to work through this diffractive auto-ethnography (Vu Citation2018). Diffraction, unlike reflection, which presents patterns of sameness, ‘is the iterative and on-going (re)configuring of patterns’ (Barad Citation2014, 168), in the making of understanding- becoming. No longer is the more-than-human viewed as passive and bounded and agency resides in the human who acts on more-than-human (Vu Citation2018). Instead, in and around an intra-action agency is an enactment between them (Barad Citation2007). With our acknowledgement of the liveliness of the more-than-human and that we are not separate from the inquiry, we welcome accountability for the care of both the human and more-than-human. Responsible caring ethics is a fibre that flexes and unfolds throughout our practices.

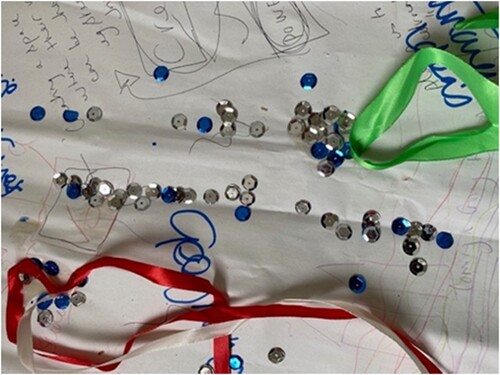

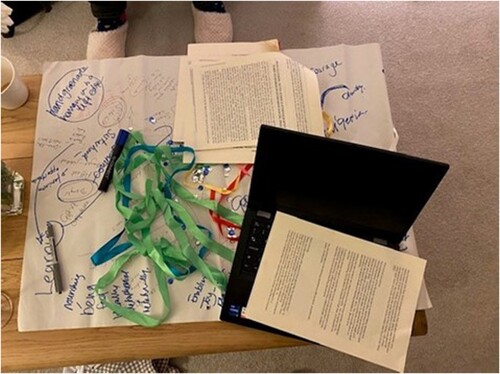

Appreciating the vibrancy and liveliness of the more-than-human (Bennett Citation2010) paper, ribbons, colours, glue, sparkly bits, marks on paper and photographs joined our playful mapping of the Soundwaves narrative. Mapping the Soundwaves narrative enabled a respectful reading (Barad Citation2007) of our narratives and relational encounters, bringing into view how, we and the more-than-human, ‘are entangled in material connections in space–time’ (Vu Citation2018, 5).

Immersing ourselves in the narratives and moving between the data, posthuman and critical new materialist philosophies and each other, uncomfortableness joined us at times. We were tongue-tied, tied down, knot in our stomach, in the process diffracting anew. Knotted ribbon shifting on paper highlighted we were ‘stuck-in-motion’. We suggest knotted ribbons, being ‘stuck-in-motion’, draws us to a ‘moment’ to enact an agential cut, ‘cutting together-apart (one move)’ (Barad Citation2007), through (re)turning and (re)telling the narrative to diffract anew (Barad Citation2014).

(Re)turning and (re)telling the Soundwaves narrative is not a recount of an incident, describing what had happened to the subject at a particular time or place, but an ongoing reworking ‘of “moments,” “places” and “things” – each being (re)threaded through the other’ (Barad Citation2010, 268). (Re)turning and (re)telling our narratives, exposes, brings to the surface different patterns, versions and understandings of our relationships, collaboration and learning experiences. Just like the patterns made by overlapping, bending, spreading sound waves, that ‘never sit still’ (Barad Citation2014, 178), our narratives are on-going and unfolding. The use of brackets in ‘(re)’, throughout our writing, aims to emphasise the processes of diffracting anew through the practices of returning to turn the data and retell our relational encounters and narratives.

presents a timeline, which outlines the process of (re)turning and (re)telling the Soundwaves narrative, from agreeing to present a conference paper to writing this paper.

Table 2. The Soundwaves narrative timeline.

Relief joined us when new and unanticipated narratives emerged and the feelings of stuckness and uncomfortableness subsided in the unravelling of the knots. Being-in-stuck-in-motion, (re)turning and (re)telling the data, brought into view different parts of the Soundwaves narrative. These are Part 1 ‘Forever in the middle’, which tells a story of the historialities (Barad Citation2007) of the multiple and dynamic relationalities between Jane, Karen and the more-than-human, Part 2 ‘Gaming it’ brings into view the narrative how Jane and Karen look for cracks where experimentation, play and vitality can join them and students when learning about ECME. Part 3 ‘Fleeting opportunities and relationships’ delves further into the data to trouble fleetingness and short-termism entangled in our relationships and collaboration. (Re)turning and (re)telling the parts continued throughout the writing process.

The presentation of each part of the narrative below, as, (re)turning and (re)telling, (re)turning and (re)telling again, (re)turning and (re)telling again, again, aims to disrupt the linear sequential telling of the narrative and emphasising past, present and future are entwined and ‘threaded through one another in a nonlinear enfolding of spacetimemattering’ (Barad Citation2010, 244).

Part 1 – forever in the middle

Why did you put the sparkles in the centre?

We are in the middle. It is not a beginning or the end of our relationship/s. Not all the sparkles are sticking. Prior to Soundwaves I had a relationship with Take Art as a teacher and then trustee. Before you started at Take Art your relationship was through Michelle, your tutor. Through your relationship with Michelle, you had heard about Take Art’s work with children, read action research, and she encouraged you to apply for a role at Take Art. I found out about you when I read your application form.

I think you have slightly thrown me by putting these in the middle, I kind of think of us going back and forth like this. Delphine (my manager) saying, ‘Oh, you need to connect with Karen’ down here [for Soundwaves], but then also at same point we have another project, Creative Elements. So, let's bring Karen back up here to research Creative Elements. It’s kind of just goes back and forth. But also, there are offshoots. So, an offshoot is the Music Education Hub (MEH), and another offshoot are the students. Also, there’s Michelle here. Then you've got Nora, whose work is here, but also here (pointing to different parts of the map, as she speaks). She kind of filtered into what we were doing because she came down to your conference. You know, all these kinds of things are offshoots from project. Young children’s music and the belief they are competent music makers are the epicentre of all of this ().

(Re)turning and (re)telling forever in the middle

(Re)turning and (re)telling the narrative amplifies ‘our’ relational ‘historialities’ stretch across many calendar years and in and through other relationships with the human and more-than-human. Initially our relationship was invisible, but marks and ribbons on paper made visible our hidden relationships with the human and more-than-human; stories about the work of Take Art, action research reports, advice from tutors and application form. Our relationship has not always been in view but with movement and unfolding they become visible, as we connect and collaborate with each other.

The map () of our Soundwaves relational encounters reminds us that our relationship and the way we are in a relationship (role/relationship) are shifting, evolving and multiple. For Karen, the ways of being in a relationship (invisible and visible) with Jane are, as a teacher/case study participant, as a trustee/critical friend, ECS lecturer/Soundwaves collaborator, as researcher/learner, as neighbour/friend … . For Jane, the ways of being in a relationship (invisible and visible) with Karen are, as a student/case study, as applicant/trustee, as candidate/possible colleague, as employee/colleague, as Soundwaves partner /collaborator, as neighbour/friend. Our relationship with each other is continuously middling, as past/present/future, are threaded through one another, ‘on-going being-becoming’ (Barad Citation2014, 182). Unlike institutional learning spaces, which Zaman and Desai (Citation2022) noticed constrained, relational transformations, with time the gap between our work organisations creates a relational space that nourishes and sustains dynamism and other ways of being in a relationship. From our multiple relationships our collaboration emerges.

(Re)turning and (re)telling again, forever in the middle

(Re)turning and (re)telling the marks on paper of the narrative highlights how the relational encounters expand, across the city and country, as we connect and collaborate with other colleagues and their organisations. Jo (MEH musician), Nora (freelance ECM trainer and author) and Michelle (academic) join the Soundwaves relational encounter. Jane explains that ‘the epicentre’ of this relational encounter is ‘ECME’. We are connected by the more-than-human belief, that young children are capable partners in music-making. Connecting and collaborating with those beyond our organisations and Plymouth creates diverse opportunities for students and us to experience and learn about this phase of music education. Students learn and connect with Michelle and Nora when Karen invites their writing about young children’s music and musicality to her teaching. During the 50 h Work Based Learning (WBL) placement ECS students and music students connect with Jo, an MEH musician. Students as delegates listen to Nora, the conference keynote, at the university’s regional ECME conference for musicians and educators.

(Re)turning and (re)telling again, and again forever in the middle

Days and weeks after drafting our first iteration of the Soundwaves narrative Karen finds sparkly bits, which had not stuck to paper during the process of mapping the narratives, in various places around her home. She returns the sparkly bits to our narrative. The returning of the sparkly bits reminds her Soundwaves and our relational encounters are continuously pulsating. We are always connected, entangled and pulsating creating moments of distance and moments of closeness between Jane and Karen here/now/there/then (Barad Citation2007). During moments of distance the more-than-human, text message, email, join us and keep us connected until we next come together. (Re)turning and (re)telling a moment of closeness and intensity we notice how it is the more-than-human Facebook posting that initiates an ad hoc idea, creating the moment of intensity. One such moment was created by the Facebook call to present at the Music Educators and Researchers of Young Children (MERYC) European conference. Working and learning together, as we mapped our relational encounters entangled in the narrative, and writing the conference paper to be presented, over many months, was a moment of intensity.

At times students also join us in these moments of intensity, for instance presenting their learning experiences with Karen at the Early Childhood degree network conference. Planning the PowerPoint, the journey to London and presenting, happen over a brief period of time. Whilst Jane is not at the conference, she is connected by liking, commenting and forwarding a multimedia post the students and Karen had posted. The pulsating movements in the making of diverse learning opportunities, create moments of distance and intensity, which we would suggest sustains our collaboration and relationship.

Part 2 – gaming it

I do worry it is OK to disrupt and challenge. I suppose coming together makes us stronger and we can resist together. The contexts we are working in, enable us to resist and find cracks. Through horizon scanning we can find cracks in our organisations’ systems to find possibilities for learning like the internship for Rachel the PhD music student; co-writing the blog with, Chloe, an ECS student, Rachel, you and Louise, ECS programme lead, other ECS students attended the conference in London and helped host the conference in Plymouth.

Our relationship creates unstable spaces, little tremors that create the cracks to learn about young children, their music and more. I do see you as my ally in my work. You are the kind of person that gets it. We have similar values and ideas about the possibilities when the arts and EC collaborate, but also you are my critical friend. You challenge me and we both appreciate and care about relationships! But I find the power I have is tricky at times for me when working with students ().

(Re)turning and (re)telling to gaming it

Our relationship with neo-liberalism positions us as resistant, some may say petulant, as we lean into Massumi’s counsel ‘don’t bemoan complicity – game it’ (cited Roulston Citation2021, 209). Working in different organisations, with different roles, but with similar beliefs and values, we dwell in relationships with each other and the more-than-human to horizon scan, in and around and beyond the music project. In this process as allies, we actively look for cracks to ‘game’ the system by identifying learning opportunities for us and students that align and welcome our philosophies that join us in the making of our pedagogy.

The movement of the ribbons, on the mapping () of our narratives, tells us the making of learning experiences is dynamic and unexpected. An email arriving in Karen’s inbox suggests the idea of a student internship. To source the internship funding Karen connects Jane with student internship colleagues. Jane writes the funding bid to fund a student to join the project. Our relationship although distant is responsive to noticing and creating connections to maintain the visibility of ECME. Noticing and creating connections enabled a post-graduate (PG) music student to work and learn with an ECS student. After the placement, another unexpected opportunity for learning emerged. A discussion Karen had with a colleague sparked and invited the idea of writing a Soundwaves blog. She then invites Rachel, a PG music student, and Chloe, an ECS student, to join Jane and Louise the ECS programme lead to co-write a Youth Music blog. Together, as authors, they shared and wrote about ‘their experiences and learning during their involvement in Soundwaves’ (Nadine Citation2022). We invite the link to the blog to join this diffractive auto-ethnography https://network.youthmusic.org.uk/learning-together-connecting-higher-education-soundwaves-network-sw-take-art The blog celebrates the interconnections and experiences between the different members of this transient scholarly group (Roulston Citation2021).

(Re)turning and (re)telling again to gaming it

Words on the blog connect us to Rachel’s learning during the student internship:

Without this opportunity I would not have experienced and learnt about EC music theory and how it is implemented in settings. EC music has not been a feature of my undergraduate or post-graduate music courses. Collaborating with Chloe enabled us to combine our knowledge and learn from and with each other. (Nadine Citation2022)

Unravelling the narrative amplifies the learning opportunities beyond the curriculum, where we learn with the students and care about their learning and experiences in and around Soundwaves. Learning that music students do not have opportunities to experience young children’s music education, Karen invites them to other opportunities to learn about this phase of education. Care for each other’s learning and experiences resists hierarchical relationships and diminishes students’ reluctance to join novel learning experiences. Instead, contexts are created where horizontal relationships between collaborators flourish and who welcome novelty, experimentation, play and vitality to the learning experiences.

(Re)turning and (re)telling again, again to gaming it

Jane explained earlier ‘working together creates unstable spaces, little tremors that create the cracks’. Working together enables us to challenge the effects of the neo-liberal discourses on education, by creating alternative learning opportunities and horizontal relationships. Our collaboration as an EC musician and ECS educator from different organisations, is ‘deeply political’ (Clark Citation2012). The (re)turning and (re)telling of the narrative with sparkly bits, ribbons and lines on paper reminds us of the emotional labour of political action and gaming it.

When disrupting and gaming the taken-for-granted ways of working together, emotions and feelings of uncertainty and being perceived as a fraud, join us. These feelings are ‘emergent, dynamic, and unpredictable’ (Marijke and Nelson Citation2022, 1364) and often constrain and tie us down. Resisting being constrained and tied down, is our relationship as an ally. Spending time together, sending an email with the words ‘this is good’ and a WhatsApp ‘thumbs up emoji’, gifts us the confidence (Mahn and John-Steiner Citation2002) to continue gaming it and creating possibilities for experimentation, playing and learning. Slippers, wood-burners and wine in remind us much of this work happens beyond our organisations – in our homes and in our own time.

Part 3 – fleeting opportunities and relationships

I feel I am learning such a lot as we unearth our relationship/s. You have given me the confidence to dip my toe into Barad’s philosophies and put them to work.

For me learning is the sparkle and it is between us but also with other people.

a downside is the learning opportunities are fleeting. The projects are always short-term, providing short-term opportunities for students to work and learn with musicians.

(Re)turning and (re)telling fleeting opportunities and relationships

Karen’s move to the same town as Jane invited wine glass, wood burner and slippers to the relational encounter. Spending time together and embarking on this post-qualitative inquiry is lively and joyful, which Kathryn Roulston describes as to ‘live intentionally’ (Citation2021, 209). We both value and enjoy experimenting and learning with each other and others. However, the words ‘learning opportunities are fleeting’ trip us up. An uncomfortable narrative emerges as we notice these learning opportunities are fleeting, the scholarly communities are transient, involve one or two students at a time and there have been fewer music students than ECS students join us. Again, we are tied down, stuck in motion, moving between data, academic theory and our pedagogic practices. Unease waves over us as we struggle with our deliberation if neo-liberal’s short-termism had tricked us into making ECME learning opportunities, with similar qualities as short-termism.

(Re)turning and (re)telling the fleeting learning opportunities another narrative unravels. The fleeting learning opportunities are not defined by pre-planned learning objectives, static knowledge and the chase for good grades or Research Excellence Framework (REF) outputs. Instead, fleeting learning opportunities emerge out of incidental encounters between the human and more-than-human; on-line platforms, emails and blogs. These incidental encounters bring into view fertile cracks where openness and dynamism flourish providing chances for students and us to invite new ideas, horizontal relationships, actions and learning to our collaboration. These fleeting learning opportunities happen beyond the formal academic curriculum and often beyond the walls of the university – via Zoom, OneDrive, email and our homes. They are out of view of the official structures and are of little value to the neo-liberal systems. The fleeting learning opportunities, we encountered, have many of the features of invisible education. Jocey Quinn explains ‘that invisible education is not planned, objectives are not fixed … and that learning is a meaningful response that can happen when engaged in everyday life (Quinn Citation2023, 8). We would suggest that the gap between the arts organisation and the university, creates fleeting learning experiences that have features of invisible education.

(Re)turning and (re)telling again fleeting opportunities and relationships

Spending time, the currency of Roulston’s (Citation2021) critical relational scholarly community, with two or three students displaces hierarchical relationships creating a space for horizontal relationships. Joining the relational scholarly community are gifts of confidence, love, trust and respect as we navigate learning and adventure in the making of new insights. Whilst the opportunities and relationships, particularly with students, are fleeting we hold onto Maya Angelou’s observation ‘I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel’. Maya Angelou’s wise counsel reminds us that the vitality and sparkle we felt when learning (and hopefully the students) lingers long after the activity. The learning may not be apparent, graded or visible to students or others today (Quinn Citation2023), but maybe tomorrow or in years to come it will emerge through creating new possibilities and ways of being with children in the making of music practices. Thus, like relationships learning entangled in these fleeting experiences is middling on-going becoming.

Returning and (re)telling again, again – fleeting opportunities and relationships

(Re)turning and (re)telling the narrative again, again brings into view Jane's and Karen’s relational ‘historialities’ and the bedrock of ever-deepening strata of unfolding and folding relationships, from which our collaboration emerges. Our collaboration has not been built but has been forming out of sight, prior to our first in person meeting, in and out of other relationships with both the human and more-than-human. It was the Soundwaves programme that created a place for us to meet physically. Attracting and connecting us are – passion for music, creativity, young children, learning and social justice. These connections provide fertile grounds for us to play, experiment, dwell and wallow in relationships and for our collaboration to emerge. The gap between our organisations and our different roles enables us to identify cracks in the neo-liberal narrative. In these cracks movement and fleetingness of learning experiences sustain relationships and keep our collaboration novel and open enabling us to resist hierarchies and short-termism.

Conclusion, comma, pause

Our (Jane and Karen) intention, by working with posthuman and critical new materialism, has been, to trouble the taken-for-granted understandings of how those from an arts and cultural organisation and a university collaborate, in the making of ECME learning opportunities for the future workforce. The pause created by this diffractive ethnography enabled us to (re)turn and (re)tell our relational encounters entangled in the Soundwaves narrative. Through the process of diffracting patterns, new thoughts and theories about our collaboration surfaced. The realisation our collaboration emerged through relationships with other humans and the more-than-human long before we met, has led to our awareness and appreciation of the ever-deepening strata of unfolding and folding relationships.

‘Fleetingness’ of learning opportunities also emerged from the (re)turnings and (re)tellings of the Soundwaves narrative. The qualities that join the ‘fleetingness’ of the learning experiences are resistance, experimentation, authenticity, horizontal relationships, our philosophies about learners, learning and, so on. Fleetingness with its more-than-human qualities enabled us and the students to get down and dirty with play, creativity and experimentation to learn about young children, their musicality and music education. The emerging theory of ‘fleetingness’ offers us reassurance, as we suggest ‘fleeting learning opportunities’ dodge the maxims of neo-liberalism resisting learning becoming shallow, formulaic and instrumentalised.

These insights about fleeting learning opportunities are likely to be of particular interest to collaborators, working in a university and an arts and cultural charity, who wish to resist shallowness, formulaicness and instrumentalisation in the making of learning opportunities. For those with an interest in growing the future ECME workforce, appreciating the unfolding strata of relationships and emerging collaboration between university and arts and cultural charity personnel, is particularly important, in maintaining the visibility of ECM in universities. Ensuring ECM is visible, will enable music students and ECS students’ opportunities to learn about ECME and offer both groups of students another career choice.

This is not a conclusion, as our relationships, will continue folding and unfolding, as we collaborate to create ECM experiences and learning opportunities for music students, ECS students and us. We hope our adventure with a diffractive methodology and the insights that emerged are useful and reassuring and gift confidence to music leaders and university educators, when they collaborate, in the making of learning experiences. Maybe, ribbons, sparkly bits and marks on paper invite you to embrace the messiness and beauty of relational inquiry, to (re)turn and (re)tell your ECME project relational narrative.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karen Wickett

Karen Wickett is an Early Childhood Studies lecturer. Based at the University of Plymouth, where she has worked since 2008, she teaches the BA Early Childhood Studies degree and supervises PhD students. Prior to 2008, she worked in a Sure Start Children’s Centre as a teacher. In practice as a teacher and academic she has witnessed the benefits for children’s and adults’ learning when an artist is involved. Recently, in her academic role she has created opportunities for students to work with artists in early years settings across Plymouth. Her research interests include arts and early childhood collaborations, constructions of curriculum and the sea in children’s lives. Her research interests are connected as she is dipping her toe into post-humanism and critical new materialist theory.

Jane Parker

Jane Parker is an Early Childhood Music lead at Take Art. Take Art is a National Portfolio Organisation funded by the Arts Council. Take Art delivers a diverse range of arts projects including Soundwaves – an Early Childhood Music programme funded by Youth Music. Jane also teaches the Trinity College London Certificate for Music Educators: Early Childhood (CME: EC) course at The Centre for Research in Early Childhood (CREC). Jane completed her MA (Master of Arts) in Early Childhood Education (Music) at CREC in 2015. Her research explores the beliefs and assumptions of educators towards their own musicality and their beliefs, assumptions and knowledge about the musicality of young children under their care. Jane’s insights have contributed to the design of the Soundwaves programme, the pedagogies that underpin it and the CME: EC course.

Notes

1 Early childhood is the phase of childhood from 0 to 8 years.

2 In England early years is the phase of care and education for children 0–5 years.

References

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. 2010. “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/Continuities.” SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come Derrida Today 3 (2): 240–268. https://doi.org/10.3366/E1754850010000813.

- Barad, Karen. 2014. “Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together-Apart.” Parallax 20 (3): 168–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927623.

- Barthold, Charles. 2013. “Corporate Social Responsibility, Collaboration and Depoliticization.” Business Ethics, the Environment and Responsibility 22 (4): 341–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12031.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Berg, L. D., E. H. Huijbens, and H. G. Larsen. 2016. “Producing Anxiety in the Neoliberal University.” The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien 60 (2): 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12261.

- Blond, P. 2010. Red Tory How Left and Right Have Broken Britain and How We Can Fix It. London: Faber and Faber.

- Bunce, Louise, and Melanie Bennett. 2021. “A Degree of Studying? Approaches to Learning and Academic Performance among Student ‘Consumers’.” Active Learning in Higher Education 22 (3): 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1469787419860204.

- Cannon, Susan. 2022. “Diffractive Entanglements and Readings with/of Data Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology.” Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology 13 (2): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.4420.

- Clark, Vanessa. 2012. “Arts Practice as Possible Worlds International Journal of Child.” Youth and Family Studies 3 (2&3): 198–213. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs32-3201210866.

- Costas Batlle, I., S. Carr, and C. Brown. 2018. “‘I Just Can’t Bear These Procedures, I Just Want to be out There Working with Children’: An Autoethnography on Neoliberalism and Youth Sports Charities in the UK.” Sport, Education and Society 23 (9): 853–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1288093.

- Dahlberg, Gunilla, Peter Moss, and Alan Pence. 2013. Beyond Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care Postmodern Perspectives. 3rd ed. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin.

- Haraway, D. J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mahn, H., and V. John-Steiner. 2002. “The Gift of Confidence: A Vygotskian View of Emotions.” In Learning for Life in the 21st Century: Sociocultural Perspectives on the Future of Education, edited by G. Wells and Guy Claxton, 46–58. New York: Wiley.

- Marijke, Hecht, and Taiji Nelson. 2022. “Getting “Really Close”: Relational Processes Between Youth, Educators, and More-Than-Human Beings as a Unit of Analysis.” Environmental Education Research 28 (9): 1359–1372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2074378.

- Massumi, B. 2018. 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value: A Postcapitalist Manifesto. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Moss, P. 2019. Alternative. Narratives in Early Childhood An Introduction for Students and Practitioners. London: Routledge.

- Murris, Karin, and Vivienne Bozalek. 2019. “Diffraction and Response-Able Reading of Texts: The Relational Ontologies of Barad and Deleuze.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 32 (7): 872–886. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1609122.

- Nadine Soundwaves. 2022. “Learning Together: Connecting Higher Education with Soundwaves Network SW, Soundwaves.” Funder Network (blog). Accessed October 30, 2023. https://network.youthmusic.org.uk/learning-together-connecting-higher-education-Soundwaves-network-sw-take-art.

- Osgood, Jayne. 2023. “The Feltness of Research Knowability and Linearity.” Keynote Presentation at the Adventures in Posthumanism Doctoral Conference April 18, 2023, University of Plymouth UK, April.

- Pegg, Ann, Jeff Waldock, Sonia Hendy-Isaac, and Ruth Lawton. 2012. “Pedagogy for Employability York: Higher Education Academy.” Accessed June 16, 2023. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/pedagogy-employability-2012.

- Powell, Sarah, and Margaret Somerville. 2021. “Drumming in Excess and Chaos: Music, Literacy and Sustainability in Early Years Learning.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 20 (4): 839–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798418792603.

- Quinn, J. 2023. Invisible Education: Posthuman Explorations of Everyday Learning (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

- Roulston, Kathryn. 2021. “Critical Relational Community Building in Neoliberal Times.” Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies 21 (3): 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708620970661.

- Sims, Margaret. 2017. “Neoliberalism and Early Childhood.” Cogent Education 4 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1365411.

- Snaza, Nathan, Peter Appelbaum, Siân Bayne, Marla Morris, Nikki Rotas, Jennifer Sandlin, Jason Wallin, Dennis Carlson, and John Weaver. 2014. “Toward a Posthumanist Education.” Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 30 (2): 39–55.

- Taguchi, H. L. 2010. Going Beyond the Theory/Practice Divide in Early Childhood Education: Introducing an Intra-Active Pedagogy. London: Routledge.

- Thomson, P., and Christine Hall. 2008. “Opportunities Missed and/or Thwarted? ‘Funds of Knowledge’ Meet the English National Curriculum.” The Curriculum Journal 19 (2): 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170802079488.

- UKRI (UK Research and Innovation). 2023. “What is REF?” Accessed November 25, 2023. https://www.ref.ac.uk/about-the-ref/what-is-the-ref/.

- Vintimilla Cristina, D., and Iris Berger. 2019. “Colaboring: Within Collaboration's Degenerative Processes.” In Feminist Research for 21st-Century Childhoods Common Worlds Methods, edited by B. Denise Hodgins. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Vu, Chau. 2018. “New Materialist Auto-Ethico-Ethnography: Agential-Realist Authenticity and Objectivity in intimate Scholarship.” Decentering the Researcher in Intimate Scholarship Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. http://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-368720180000031007.

- Ward, Kelly, and Lisa Wolf-Wendel. 2000. “Community-Centered Service Learning: Moving from Doing For to Doing With.” American Behavioral Scientist 43 (5): 767–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027640021955586.

- Young, Susan. 2021. “The Branded Product and the Funded Project: The Impact of Economic Rationality on the Practices and Pedagogy of Music Education in the Early Childhood Sector.” British Journal of Music Education 38 (2): 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051720000248.

- Zaman, Rehana, and Jemma Desai. 2022. “On Art and Friendship: Expanding What Relation Can Be.” Wasafiri 37 (4): 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2022.2100093.