ABSTRACT

Development projects inevitably pose risks to the health of humans and the planet. Health impact assessment (HIA) practitioners increasingly evaluate the mental health effects of development but have rarely considered those caused by public understanding of risk (‘risk perception’) itself a determinant of health. This paper proposes a new psychosocial model of public understanding of risk in response to the literature on perceived high risk developments. It exemplifies the psychosocial process that occurs when people respond to industrial threats to health. In doing this, it draws upon literature from psychology, social science and public health. The model is foregrounded in the context of psychosocial health in HIA. The paper also reviews the health and well-being effects that may result. Overall, it is argued that the philosophical and moral underpinnings of HIA compel practitioners and developers to understand the formation and ongoing development of public understandings of risk in light of the cultural, demographic, temporal and other contextual factors shaping them in unique development contexts where HIAs are undertaken, and how understandings of risk actually affect community health. We encourage them to propose mitigation measures and solutions that accord with the values of Planetary Health.

Introduction

Public understanding of risk or ‘risk perception’, as it is commonly known, has emerged as a theme across the impact assessment (IA) literature (e.g. Wlodarczyk and Tennyson Citation2003; Stewart et al. Citation2010; López-Rodríguez and Escribano-Bombín Citation2013; Roach Citation2013). It relates to the question of what constitutes an ‘acceptable’ level of risk for a development project to pose to humans or the environment. The granting of a social license to operate – often theorised as ‘ongoing acceptance or approval by the local community and other stakeholders who can affect profitability’ (Parsons and Moffat Citation2014, p. 274) – relies on project operators negotiating this issue with a given community. Yet, the psychological process of anticipating a potential risk posed by the construction, operation or decommissioning of a development can be associated with mental health and well-being effects within individuals and communities (Stewart et al. Citation2010; Birley Citation2015).

Symptoms of poor mental health in the context of a development project may be triggered by two health determinants associated with the issue of risk: public understanding, often referred to as ‘perceived risk’ in the IA literature (Wlodarczyk and Tennyson Citation2003, p. 180; Stewart et al. Citation2010, p. 1155) and ‘environmental annoyance’ (Lima and Marques Citation2005, p. 228).Footnote1 ‘Risk perception’, referred to in this paper as ‘public understanding of risk’, is the less theorised of the two, and the topic here.

Risk can be defined as ‘uncertainty about and severity of the events and consequences (or outcomes) of an activity with respect to something that humans value’ (Aven and Renn Citation2009, p. 6). The process by which individuals and communities affected by a proposed development form an understanding of risk before the beginning of construction of the development has been described in one paper as the psychological process of ‘lay people’s estimation of the significance of these outputs, and their expectations in terms of quality of life’ (Stewart et al. Citation2010, p. 1155). Understandings of risk are developed by and affect all parties involved in an IA – individuals, communities and sub-groups within communities, developers and regulators. They are continually evolving, dynamic and changing, negotiated in relation to others’ views expressed and shared in discussions in the affected geographical area and social environment, and shaped by the power relations between the involved parties. We focus on understandings of risk held by members of the public in communities: those held by individuals and/or which are shared by several community members.

Environmental annoyance describes the adverse mental health and well-being effects that may occur when a person develops awareness of the presence of an environmental effect, e.g. noise, visual disturbance or change in air or light quality, and experiences it viscerally or physically. For example, noise annoyance is connected to ‘symptoms of arousal and stress’ (Lima and Marques Citation2005, p. 228). Whilst these two determinants are clearly connected as the former is the anticipation of the latter, we focus on the former.

There are now standardised tools developed for the UK and US context such as mental well-being impact assessment (MWIA) (Cooke et al. Citation2010), mental health impact assessment (MHIA) (Adler School of Professional Psychology [Citationdate unknown]) and other less well-circulated tools (see Lucyk Citation2015) to aid IA practitioners in considering project effects on population mental health. MWIA has been applied in several geographies outside the UK, e.g. Australia (Coggins Citation2018) and Portugal (Cooke et al. Citation2016). Just as health impact assessment (HIA) is practised in different ways in different national and cultural contexts, tools devoted to particular branches of health, e.g. MWIA must, in their standard format, also be adaptable so that they can capture the influences on mental health in different local and cultural contexts.

An example of this with MWIA was demonstrated in a Chilean study (Ampuero et al. Citation2015). In its original UK form, MWIA identifies factors which are external to the individuals’ mind and body that influence mental well-being: population characteristics, social relationships and the core economy, and wider determinants, as well as levels of equality and social justice (Cooke et al. Citation2010). Ampuero et al. (Citation2015) conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Chile using MWIA as a guide to investigate external influences on community-level mental well-being after a tsunami. They found a different set of external influences on local people’s well-being to those in the MWIA model (Ampuero et al. Citation2015, p. 192–193), and adapted it by exchanging its wider external influences for another, environmental set: ‘ecology, culture, organization and milieu’. Also, the emergence of particular mental health topics within IA practice that are present in all development contexts, and are not covered by standard IA instruments, require additional tailor-made tools, e.g. public understanding of risk. This is particularly important in the case of this topic as a local baseline on what understandings local people develop cannot be established from available mental health data (e.g. government or health sector statistics on anxiety or depression). Understandings of risk are project, location, culture and time-specific. Some of these understandings emanate from individuals more prone to poorer mental health, as well as those that emerge at the collective community level through a dynamic relationship with local factors.

This paper begins to develop a psychosocial conceptual framework for investigating the public understanding of risk. It outlines a preliminary theoretical model of the way that public understandings form, develop and change. It then reviews the social and environmental psychology and public health literature on associated health effects. The model can be used to underpin a set of consultation tools that will be outlined in a second paper submitted to IAPA. The discussion on ‘risk’ examines literature on nuclear facilities, as these are generally identified as conjuring up the highest levels of ‘fear and dread’ of all the public risks analysed (Taylor Citation2012, p. 9) and are often seen as ‘dreadful’ (Siegrist and Visschers Citation2013, p. 112). Risks to health that are seen as ‘uncontrollable and dreaded’ are linked to higher health-risk perceptions (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015, p. 86). Our model could, though, be applied in any HIA where risks are associated with potential health impacts ranging from low-level environmental annoyance to threats to life, e.g. possible exposure to chemicals, radiation and pollution.

Psychosocial health and well-being in IA

Historically, there have been barriers to addressing mental health impacts in IA. Psychosocial health is part of a suite of mental health issues in IA (for a full review, see Lucyk Citation2015) and needs positioning in this background landscape. Stewart et al. (Citation2010, p. 1167) stated in the context of addressing environmental hazards to health that: ‘by concentrating solely on risks to physical health, professionals from both public health and regulatory bodies fail to understand and take into the wider determinants of public health and wellbeing’. This implies a neglect of mental health. There has been (Wright et al. Citation2005) and is still some suspicion of subjective public perceptions or self-reports of health as a source of data in contrast to ‘objective’ clinical data collected by epidemiologists. In the past decade, there is evidence of a rising emphasis on the inclusion of mental health and well-being in IA. For example, 300 MWIAs had been undertaken in the UK by 2009 (Cooke and Stansfield Citation2009). However, mental health is still under-considered within HIA practice. In 2015, a Canadian paper revealed that in its survey of 156 HIAs, 73.1% included mental health at scoping stage, and just 37.7% of those HIAs ‘measured mental health problems at baseline’(Lucyk et al. Citation2015, p. 7).

The term ‘psychosocial’ is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘pertaining to the influence of social factors on an individual’s mind or behaviour and to the interrelation of behavioural and social factors’ (Oxford English Dictionary cited in Martikainen et al. Citation2002, p. 1091). Environmental psychologists (e.g. Twigger-Ross and Uzzell Citation1996) also recognise that factors from the biophysical environment can affect people’s minds and behaviour. We argue that as both social and environmental factors are part of a multi-dimensional external environment, they merit dual consideration when the possibility of environmental change with associated health impacts has psychosocial consequences.

Environmental psychologist Edelstein (Citation2003) reported difficulties in the USA in the 1980s and 1990s in getting the psychosocial impacts of public understanding of risks from nuclear and other noxious and toxic industrial operations accepted as legitimate health concerns in legal tribunals. Contention from judicious personnel was based on well hashed-out debates about the value of quantitative versus qualitative research methods and data, objective versus subjective empirical evidence, and restrictions on ‘modern’ societal and technological progress. There is evidence that these issues may have clouded IA more broadly. For example, a study of health in EIA in 10 European countries, Canada and the USA (Hilding-Rydevik et al. Citation2005, cited in Kågström et al. Citation2013, p. 204) revealed that common psychosocial concerns with ‘recreational areas, the state of the economy, and the availability of job opportunities’ were often considered. However, intangible social and psychosocial concepts or clinical mental health symptoms and conditions, the topics of ‘social capital, social cohesion, mental disorders, worry and anxiety’ were seldom assessed (Hilding-Rydevik et al. Citation2005., cited in Kågström et al. Citation2013, p. 204). A more optimistic picture emerged more recently in the Canadian review (Lucyk Citation2015). Various examples of North American HIAs are discussed that have examined these psychosocial health issues.

At the time of writing in March 2018, only three papers reporting on robust, tailor-made assessment methods for exploring specific psychosocial health issues within an IA in different countries were found (and all published in IAPA): a psychometric survey examining the psychosocial effects of a waste incinerator in a Portuguese town (Lima and Marques Citation2005), a mixed methods approach to examining the impacts of development on the psychosocial relationships that people have with places and their communities based on a UK case (Baldwin Citation2014), and Ampuero et al.’s (Citation2015) environmental model of well-being. The literature review behind this paper found no dedicated psychosocial tools readily available for measuring and assessing public understanding of risk. However, there is emerging interest in the topic and acknowledgment of its importance in HIA.

Edelstein produced a concept note for a new training course in Psychosocial Impact Assessment for the 2017 International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) conference and delivered a webinar on the subject.Footnote2 Yet, it remains unclear if many HIA, SIA and other IA practitioners have fully engaged with psychologically robust conceptual and methodological possibilities for measuring and addressing psychosocial health issues and if they have not done so whether it is because they lack the perceived knowledge and confidence to do so and/or whether they are unconvinced of its importance. We locate our approach to and methodology for measuring public understanding of risk within this small but emerging literature. Our model is a first step towards developing more user-friendly ways for measuring and assessing public understanding of risk.

Public understanding of risk in IA: a moral perspective

Returning to the question of: what an acceptable level of risk is for a development to pose to humans and the environment?, the answer is inherently subjective, depending upon the values underlying the reasons for taking the risk. Whilst discussing the moral values behind development decisions is not our focus here, we note the philosophical, and somewhat moral values, for HIA originally set out in the influential HIA document, the Gothenburg Consensus Paper: ‘Democracy’, ‘Equity’ and ‘Sustainable Development’ (World Health Organization Citation1999, p.4).Footnote3 We advocate that all community perspectives on risk should be heard and heeded in development decision-making (democracy); that understandings of risk that have the potential to cause adverse mental health effects in a community must be given equal consideration with other physiological health impacts, especially as they may disproportionately affect vulnerable groups (equity); and that all development is sustainable. With these values in mind, we reflect on this paper’s value standpoint through a recent paper that attempts to theorise public understandings (‘perception’) of risk (Birley Citation2015).

Author Birley correctly highlights this topic as a potential social determinant of health. He offers a selection of psychological models: information deficit, social amplification, psychometric, cognitive biases and cultural worldview that explain why ‘risk perceptions are often biased by how the brain works’ (Birley Citation2015, p. 1). He illuminates a range of cognitive and affective strategies described in the models that people consciously/subconsciously employ to derive meaning from understandings of risk. For example, the ‘information deficit’ model assumes that when people are given more information about a risk, their perception will change. The ‘social amplification’ model describes a psychological process where people attach a feeling to memories arousing mental imagery related to a particular risk, which may colour their present risk perception in a positive or negative way (Birley Citation2015, p. 2).

Birley discusses two ‘levels’ of risk perception that may detract from so-called ‘rational’ and proportionate judgements on the assessment of project risks in HIA/IAs. These are ‘amplified’ perceptions by communities that may induce negative mental health symptoms, and lead to ‘excessive mitigation’, and ‘attenuated perceptions’ by ‘project proponents, impact assessors or communities’ that may lead to ‘insufficient mitigation’ (Birley Citation2015, p. 1). In the middle, Birley places the rational individual who by implication makes the ‘right’, presumably scientific or medical, judgements about the health effects of risks: ‘The assumption is made that well-informed people will rank risks so that reasonable mitigation measures can be advocated’ (Birley Citation2015, p. 1). This view resonates with the information deficit model.

However, this tri-polar analytical schema undervalues the socio-cultural meanings that individuals or communities may attribute to their understanding of certain risks and the scale of distress it causes and also the levels of influence that such meanings have on individual and collective reactions to risk, as people understand it. What for one community is experienced as a lower or less important risk with manageable effects may be experienced as catastrophic and intolerable in another depending on their worldview, e.g. loss of lands that are vital to physical, psychological, and spiritual health in an indigenous community, hence leaving deep-rooted and long-lasting adverse impacts (Albrecht et al. Citation2007). Australian researchers (Higginbotham et al. Citation2007) have devised and validated an Environmental Distress Scale designed to measure such distress. They demonstrate the multi-dimensional nature of the health impacts of distress by conceiving the scale along a biopsychosocial spectrum where impacts may be physical, psychological, emotional and socio-economic. From this work emanated the concept of solastalgia, a ‘psychoterratic’ illness (Albrecht et al. Citation2007) to reflect the depth and severity of effects that may occur.

Birley’s analysis is rooted in a tradition of Western, scientific, rationalist thought. It does not take onboard the variety of socio-cultural factors, dynamics and information that shape and modify cognitive and emotional responses to envisaged risks. It does not take full account of the variety of perspectives articulated by local residents affected by a development proposal. These weaknesses become amplified when Birley’s argument is placed in cross-cultural contexts.

Some public health authors are championing a more holistic view of health underpinned by the symbiotic relationship between the health of people and the planet (Dustin et al. Citation2009), e.g. ecological (e.g. McLaren and Hawe Citation2005) and planetary health (The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health Citation2015; Watts et al. Citation2015) arguments. ‘Planetary health’ is a recent conceptual framework in public health research devised by a commission of experts from the US-based Rockefeller Foundation and influential public health journal, The Lancet, defined planetary health in the simplest terms as ‘the health of human civilisation and the state of the natural systems on which it depends’ (Horton Citation2015, p.1921). See The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health (Citation2015) for a full account. Their idea is to study stresses to the ecosystem and how these affect the equilibrium of mutual interdependence and interaction between humans and ecosystem (McLaren and Hawe Citation2005, p. 9) that determines human health (Watts et al. Citation2015; cited in Brousselle and Guerra Citation2017, p. 14) with varying effects in order to draw up policies that protect the planet from permanent changes affecting human health. Thus, the current discussion is supported by emerging thinking in public health. Severe environmental distress results from adverse environmental change caused by excessive development in aid of ‘progress’ that has damaged the global ecosystem and catalysed climate change (Marmot Citation2007). ‘Correct’ understandings of risk depend on the psycho-cultural worldview one subscribes to (e.g. scientific rationalist, cultural-spiritualist) and how one experiences the effects of risks taken. As Edelstein (Citation2003, p. 2002) writes: ‘Herein is the radical dimension of psycho-social impact. It represents a tool for unveiling the deconstructionist “risk society” and is therefore a decided threat to the modern paradigm’.

This paper unveils a blended psychosocial/socio-cultural approach to the public understanding of risk. It recognises a variety of personal and socially produced factors as influencing the way in which risk is developed, understood and experienced subjectively, and acknowledges the role of local context, demographic heterogeneity and temporal factors in shaping understandings. It does not make a subjective judgement on the ‘correct’ understanding of risk.

Conceptual framework

The preliminary psychosocial model of public understanding of risk is underpinned by an iterative literature search, i.e. that which is useful in assisting with model development, on ‘risk perceptions’ of nuclear reactors and waste facilities, and other industrial facilities perceived as being very risky by individuals and communities, and about which there is a developed literature. The iterative search strategy employed comes from social anthropology as a technique of inclusion/exclusion boundary setting in literature reviews. This requires not adopting a prescriptive approach based on the number of resources consulted, but rather allowing salient topics, factors and methods in the literature to reveal themselves until the point of ‘saturation’ is reached, e.g. additional resources consulted state the same themes, factors, studies and authors, and further combinations of the search terms generate the same sources.

After considering current social and clinical psychology theorising on health-risk perceptions (i.e. Greene et al. Citation2014; Ferrer and Klein Citation2015), the iterative literature search strategy involved searching databases including MedLine, PsycINFO, ProQuest, Scopus, and EMBASE for social science, psychology and epidemiological studies using combinations of the following words: radiation + nuclear + energy + psychological + psychosocial + public + understanding + risk + perception + health + environmental + epidemiology + psychiatric + well-being + wellbeing + social + distress + impact + cognitive + fear + communities + people.

A published research literature review (Taylor Citation2012) on ‘public nuclear risk perception’ covered the time period of 1990–2012 and reduced the 169 most-relevant articles from social science and psychology to 50. It divided the literature up into methods/theories and disciplines into four main paradigms: ‘psychometric’, ‘mental models’, ‘narrative’, and ‘media and discourse analysis’ (Taylor Citation2012, p. 24–25). Our conceptual approach is different in that we resisted working within a single ‘school of thought’, but adopted a fluid approach drawing on clinical, social and environmental psychology, sociology and anthropology. Our interdisciplinary perspective was used to develop a more nuanced approach to the formation of understandings of risk. We placed the internal psychological process that individuals undergo when forming an understanding of a specific risk from a proposed development in the local socio-cultural contexts to highlight external factors outside of the individuals’ mind that influence their internal processing.

We used Taylor (Citation2012) as a guide, acknowledge the key theoretical contributions of these paradigms and focused on studies within the time period of this review. However, our main inclusion criteria were academic research studies from any country which analysed the broader social and cultural contexts and factors shaping risk perceptions of existing and new-build industrial facilities (i.e. energy and infrastructure) that could potentially pose environmental health risks to humans and provided sociological or psychological data and/or theorising about them. Exclusion criteria were: papers offering a purely mathematical and non-socially contextualised quantitative risk assessment perspective on public risk perception; and/or those focused on actual nuclear disaster situations as opposed to the contexts of everyday development (with one exception – Barnet 2007 – as it reviewed relevant health effects) to which our model is applicable. We narrowed down possible papers to aid with model development using our main inclusion criteria from 43 to 27, and drew on 6 additional public health texts to augment the list of potential health effects. Our psychosocial model is a work in progress as it has not yet been tested.

A voluminous literature establishes connections between the social experience of risk perceptions of industrial, and energy production and disposal, sites and mental health effects (e.g. Wakefield and Elliott Citation2000; Pidgeon et al. Citation2008; Venables et al. Citation2012; Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014; Walker et al. Citation2015). These effects are not only social experiences. They occur across a continuum of social processes, biopsychosocial mechanisms and subclinical and clinical (pathological) health outcomes. No epidemiological studies establishing causal links along this health pathway were found in this review.

We hypothesise that the lack of epidemiological studies may be attributed to medical research bodies not prioritising this topic, perceiving its effects as non-fatal and mainly common, low-level anxiety disorders. It may result from challenges linking conceptual social science and psychology theorising with epidemiological and biomedical approaches. There may be a lack of cross-disciplinary capacity across these fields in existing research coalitions. It may also reflect a scholarly view that it is hard to prove the health impacts of understandings of risk because they can occur simultaneously with environmental annoyance (Lima Citation2004). However, we may infer some of these causal relationships, until they are shown empirically, from the broader research literature in domains such as psychology.

Generalised anxiety disorder and other anxiety disorders (e.g. post-traumatic stress disorder) are established health effects associated with negative understandings of risk (see, e.g. Stewart et al. Citation2010). In the broader context of global health and not just in the context of development, anxiety is a widespread global health problem and should not be dismissed as trivial. The severity of disablement resulting from anxiety disorders should also not be underestimated. Anxiety disorders were recorded as the sixth leading cause of disability globally in 2010 in respect to years lost to disability (YLD) in high-income and low- and middle-incomes countries (Baxter et al. Citation2014, p. 2366). This compares with diabetes (globally ranked 9th) and stroke (38th). In 2010, YLD rates for anxiety disorders were six times higher than all cancers aggregated (65 YLDs per 100,000) (Baxter et al. Citation2014). Anxiety has been linked to mortality with 7% of all suicides associated with anxiety disorders globally (Baxter et al. Citation2014).

The current evidence base on ‘risk perception’ and social and environmental psychology and social sciences studies addressing ‘risk perception’ in the context of the development or the presence of infrastructure and energy facilities ranges from studies adopting psychological approaches employing highly structured psychometric testing (e.g. Lima Citation2004) to qualitative social studies of the ways that different factors appear to influence local understandings in the social context (Parkhill and Henwood et al. Citation2011). These methods are appropriate for this topic.

The psychosocial model

The key theoretical aim of the model is to link the social, visceral and emotional experiences a person has in developing an understanding of risk with the underlying psychological processes and mental and physical health outcomes (the biopsychosocial spectrum). The pragmatic purpose of the model is to provide a conceptual framework that can be tested empirically and which will help to predict and explain the processes and factors involved in developing an understanding of risk and, in turn, influence attitude development and potential health effects. Therefore, the aims of the model are for it to be both predictive and explanatory. It is a causal model specifying causal pathways between factors. It is also an explanatory model in purporting how understandings of risk are shaped, which then shape attitudes about a development project.

The literature selected from the broader review is that which plausibly assists in outlining a causal model recognising the dynamic interplay between social, psychological and biological factors in the ways in which understandings of risk affect people’s health and well-being. In outlining the model, we draw upon the aforementioned psychosocial model of ‘risk perception’ in response to environmental threats posed by a waste incinerator (Lima and Marques Citation2005, p. 228–229); psychological theories of health-risk perception (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015); social epidemiology literature which identified the casual pathways between social factors and mental and physical health outcomes (in Carney and Freedland Citation2000; Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000); and the social and environmental psychology literature on community responses to environmental change catalysed by energy/industrial developments (various).

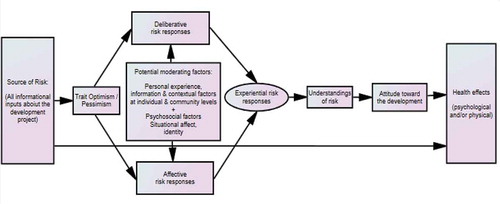

The model is shown in and incorporates a mix of internal psychological factors (psychological processes), as well as potential external influences that are interpreted individually. The model runs chronologically from left to right and begins with the identification of the anticipated threat of which the individual may be at risk of being adversely affected and ends with potential health effects. Between the starting and end points in the model are several factors that mediate the relationship between the source of risk and health effects. These mediating factors reflect the predominantly psychological process of interpreting and making meaning from the source of risk which ultimately has an important bearing on health effects. The model also specifies a direct path from the source of risk to health effects which reflects the unfortunate reality that some industrial developments create polluting effects that are directly detrimental to the environment including people. Our conceptual and pragmatic interest in the model is not in the direct relationship between the source of risk and health effects but rather the psychological process (i.e. individual and community interpretations) between source of risk and health effects that may predict and explain health effects individually and at a community level.

Figure 1. Psychosocial conceptual model of formation of public understandings of health risk.Footnote4

The model depicts the psychological processes that occur in developing an understanding of risk, which will evolve and change as individuals and communities have and are influenced by new experiences, different contextual factors, and as new information is acquired and evaluated. This part of the model borrows much from Ferrer and Klein (Citation2015, p. 85–87). This process is first shaped by the effects of personality disposition, specifically trait optimism/pessimism, which in turn helps to shape a psychological/emotional response which influences a first-impression understanding of risk.

Trait optimism/pessimism

The model purports that the first internal factor that bears on individual understandings is a person’s personality ‘traits’, described as ‘stable and general dispositions to experience particular emotions’ (Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000, p. 216–7), e.g. how one’s affective disposition colours one’s response. The personality trait that is particularly relevant in the development of individual understandings of risk is the optimism–pessimism dimension. Dispositional or trait optimism and pessimism are conceptualised as being at opposite ends of a continuum, with optimism reflecting favourable expectations of the future which have been associated with better physical health outcomes (Carver et al. Citation2010). There is evidence that supports the hypothesis that people with high trait optimism are more likely to perceive fewer risks or not be as concerned about those risks in development projects compared with people with high trait pessimism (Lima Citation2004; Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014; Marcon et al. Citation2015, p. 270). Predisposition to anxiety is a psychological response associated with a pessimistic disposition. Also, distress is linked to more pessimistic (higher risk) understandings of risk. Having a generally optimistic disposition (trait optimism) does not guarantee that a person will develop an optimistic understanding of risk because understandings of risk are ‘domain specific’, e.g. developed in response to a specific topic/situation (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015, p. 85). It is hypothesised in the model that the personality characteristic of optimism/pessimism will shape a person’s responses and understandings (perceptions) about the likely level of risk from the development, through the mediating effects of their deliberative and affective responses.

Deliberative, affective and experiential risk responses

The ‘type’ and extent of psychological response a person has to the potential risk: (1) deliberative, (2) affective and (3) experiential (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015), shapes the ‘type’ of understanding the person develops. These responses are thus defined.

Deliberative responses to risk are ‘rational’, ‘systematic, logical and rule-based’ (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015, p. 86), where a person relies on ‘reason-based strategies’ to judge the likelihood of a negative outcome from a risk.

Affective responses to risk refer to the emotions associated with a person’s developing understanding of risk, specific to the industrial development. Affect is highly influential in negotiating judgements linked to risk and uncertainty. Feeling threatened, worried and anxious are associated emotional effects which may or may not morph into a chronic and/or acute condition requiring clinical treatment. These effects may also exacerbate pre-existing chronic stress or anxiety.

Experiential responses are the result of a rapid psychological processing or cognitive negotiation between deliberative and affective responses, and refer to the content of the understanding of risk, and are ‘consciously accessible’ to the individual (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015, p. 86), e.g. ‘My gut is telling me that x will result in x…’. As such, experiential responses are depicted in the conceptual model as being derived from both deliberative and affective responses.

Different studies vary in their emphasis on the amount of causation attributed to each of the three psychological risk responses. For example, Taylor (Citation2012) cites cognitive and affective dimensions, alongside individual and societal ones: cognition includes deliberation and emotion. These variations can be attributed to authors’ theoretical or disciplinary orientation, local psycho-cultural factors (e.g. do cultures emphasise emotional or deliberative modes of expression and communication?), environmental factors (e.g. do some environments such as beautiful national parks or wildernesses cause people to react more emotionally as opposed to office environments, which may engender a more flat, neutral emotional response that appears more ‘rational’?) and situational factors (e.g. does the context cause people to think/debate with others or focus on their emotions?).

Potential moderating factors affecting the relationship between trait optimism/pessimism and deliberative and affective risk responses

Potential moderating factors, if relevant to a given industrial development, will contribute to shaping a person’s understanding of risk by affecting the strength of the relationship between trait optimism/pessimism and deliberative and affective risk responses. Lima and Marques (Citation2005, p. 228–9) describe the role of moderating (and mediating) factors in changing the meaning of the source of risk, which may or may not include modifying the severity of the risk understanding. For example, in their Portuguese study the waste incinerator was regarded more positively by people who associated it with preferred local values or identity.

Potential moderating factors that we have identified include (1) perceived direct or indirect personal experience of comparable industrial developments, (2) individual knowledge of epidemiology and scientific methods and interpretation of mediated information, (3) broader contextual factors that a person is exposed to and (4) social identity in relation to a local sense of place. These potential moderating factors that may influence understandings of risk include those which are personal (e.g. that influence the individual person), and those which are both personal and social (e.g. affecting people at both individual and collective community levels). Specific factors may affect individuals and communities differently before and after the announcement of a proposed facility, and also in locations where there is a proposal to extend an existing facility as opposed to one for a new-build facility. We have categorised the following lists of factors accordingly. We also propose to measure them on an individual level in our model it is not yet sufficiently developed to adopt community level measures of moderators.

Moderating factors specific to the individual person that may affect understandings of risks from both new and existing nuclear facilities and other industrial installations understood to be of high risk include, but are not limited to:

(1) Personal experience

Before the announcement of the proposal facility:

previous experience of hazards and method of learning about an occurrence of them (Greene et al. Citation2014, p. 261);

After announcement of the proposed facility:

perceptions of interventions from official personnel including government agencies and opinion leaders, and cultural and social groups (Greene et al. Citation2014, p. 261)Footnote5;

the perceived control an individual has over risks (framed in terms of traits such as ‘self-efficacy, organisational capacity, participation and empowerment’) (Greene et al. Citation2014, p. 766);

and perceived proximity to the sites of a facility and potential contamination (Howe Citation1990, p. 275).

(2) Information and knowledge

knowledge of epidemiology and scientific methods (Howe Citation1990, p. 275);

(3) Contextual factors

cultural factors, as identified locally (Lima and Marques Citation2005: Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014);

social and demographic factors, e.g. age and gender (Hamilton Citation1985, p. 463; Marcon et al. Citation2015); parental status (Hamilton Citation1985, p. 463; Marcon et al. Citation2015, p. 270); education (Howe Citation1990, p. 275; Lima Citation2004; Lemyre et al. Citation2006); nationality (local or foreign); local language abilities (Greene et al. Citation2014; Marcon et al. Citation2015).

Personal factors and broader social factors colouring risk understandings include, but are not limited to:

(1) Personal experience

After announcement of the proposed facility:

social networks (Greene et al. Citation2014, p. 261);

perceptions of fairness in the planning and siting process,

attribution of fault (both Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014);

likely economic gains (Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014; Kashpur et al. Citation2015);

the human-created, technological, involuntary and uncontrollable nature of risk exposure (Slovic Citation2012; Greene et al. Citation2014; Ferrer and Klein Citation2015);

(2) Information and knowledge

number of different information sources (Howe Citation1990, p. 275).

(3) Contextual factors

point in time, e.g. understandings of risk may be higher at the start of the planning process but it is expected that there will be variation in understandings, so this would be measured across the lifecycle of the construction and operation of the industrial facility if there were repeat assessments of public understanding of risk (Taylor Citation2012);

In communities with an existing facility, personal and social factors include, but are not limited to:

(1) Personal experience

Before the announcement of the proposed facility

knowledge of local incidents (Venables et al. Citation2012); and international disasters (e.g. Chernobyl, Fukushima) caused by technological or operational mishap, or natural disaster (Mueller Citation2010);

experience of relatives with illnesses (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015) linked to the potential health effects of the facility (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008).

After the announcement of the proposed facility

the perceived contribution of the facility to the social life of the community

what associations the sight/visceral experience of the facility, and presence of activity pertaining to safety factors, e.g. personnel monitoring radiation, familiarity with technological aspects/occupations conjures up in local people’s minds, e.g. health risks (all Venables et al. Citation2012);

individual perceptions of how the facility fits in with local values (e.g. revered landscapes, are the economic benefits valued over controlled hazards?) (Venables et al. Citation2012; Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014);

proximity to the facility for each individual (Hung and Wang Citation2011, p. 668);

trust in the energy company, government and operators (Wakefield and Elliott Citation2000; Venables et al. Citation2012; López-Navarro et al. Citation2013), and opportunities for meaningful dialogue and engagement with them (Wakefield and Elliott Citation2000).

(2) Information and knowledge

media reporting, e.g. volume and, type of reporting, implications, i.e. how much of a threat is the proposed facility? (Greene et al. Citation2014, p. 759).

The extent to which risk communications are perceived to be clear (Venables et al. Citation2012; Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014).

Perception of the threat of terrorism, although not directly linked to an individual reactor, is an association made with the presence of a threatening nuclear reactor (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008). The availability of social support and government reaction are explanatory drivers of community-level understandings of health risks (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015). Our second paper proposes measurement scales for these moderators.

Understandings of risk

Developing an understanding of risk is shaped by multiple factors. Being a psychological process, it involves both internal and external inputs or sources of information which interact and are interpreted in different ways across a community. As noted in , we are proposing that understandings of risk are directly influenced by experiential responses to the development and are potentially moderated by a range of factors.

Understandings of risk for an individual equates to their current evaluation of the risks of a project which is reached by consciously weighing up and making sense of their experiential risk responses. Public understandings of risk are gauged from the aggregated (collective) individual understandings of risk. Given this process, understandings of risk are subjective interpretations of risk and may appear to be potentially imprecise from a Western scientific point of view (i.e. subject to insufficient and ‘biased’ inputs) as well as subject to potentially ‘biased’ internal analysis (cognitive, emotional and deliberative), and dynamic (an understanding of risk may change as the inputs and subsequent internal processing change).Footnote6 However, being a subjective interpretation of risk there is no objective measure or valid argument by which to compare or conclude imprecision. Rather, the understandings of risk concept is an acknowledgement of the importance of subjective meaning to the health and well-being of individuals and communities.

Attitude towards the industrial development

Understandings of risk are also powerful judgements that strongly influence individual and community attitudes towards a development. Attitudes towards a development reflect individual thoughts, emotions and behaviours in relation to the development, positively and/or negatively, which collectively reflect community attitudes. If a development goes ahead while community attitudes are negative, detrimental implications for the health (psychological and physical) and well-being of individuals and communities may ensue. The most likely mechanism for ill-health effects is through chronic stress and distress associated with a perceived lack of control over the situation as well as from understandings that one is being exposed to an unhealthy environment (Lima Citation2004), and in some situations, unresolved loss and grief over the pre-development environment (Higginbotham et al. Citation2007).

Summary of the model

To sum up the model, individual understandings of risk are formed as part of a dynamic psychological process involved in assessing the risk of an industrial development. Understandings of risk are directly influenced by a person’s experiential risk responses which are informed by their deliberative and affective risk responses to the industrial development. The internal personality trait, optimism/pessimism, colours the way a person considers the risk of a development and their deliberative and affective risk responses. The relationship between optimism/pessimism and deliberative and affective risk responses is also moderated by external personal (personal experience, information, contextual factors) and psychosocial or cognitive/emotional variables (e.g. affect, identity) that may or may not be relevant to a particular industrial development. This means the relationship between optimism/pessimism and deliberative and affective risk responses will look differently for people depending on these moderating factors. Through this psychosocial process, a person’s understandings of risk emerge, with this process repeating itself while ever an individual is exposed to new information and experiences. As such, understandings of risk are potentially dynamic and may change during the HIA process.

In the model, risk understandings are cognitions that mediate between all informational inputs (external and internal) about the development project and attitudes about the development which in turn have a bearing on any subsequent health effects (physical and psychological) such as the development of symptoms of mental health and well-being. Kubzandky and Kiwachi (Citation2000) consider environmental events as stressors and emotions as responses to stressors. Personal understandings of risks crystallise around anticipated or actual environmental changes/events, potentially stressful events, and may provoke adverse emotional responses, e.g. anger, depression. Emotions can therefore result from stress as well as mediate its effects (Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000, p. 215). While understandings of risk are subjective and there will be a range of levels within a community, it is expected that there will also be some consistency across communities depending on the generally accepted norms around objectively assessing the severity of risk of an industrial project. For example, community understandings of risk in response to a planned nuclear facility are likely to be higher than for a community facing a new low-rise residential development. Yet within both communities, there will be a range of understandings of risk.

High-risk understandings may be indirectly linked via mental health conditions such as stress and anxiety to physiological illnesses for which these are risk factors (see Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000, for a full review of casual pathways linking emotions to health). There is evidence in the health psychology literature that high-risk understandings may preclude the motivation or likelihood of people adopting ‘preventive or mitigating behaviours’ in a fatalistic sense (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015, p. 87).

Low-risk understandings may, by default, protect a person against experiencing the adverse mental health symptoms associated with understandings of high risk. With the absence of symptoms such as stress, low-risk understandings may also indirectly act as protective factors for physiological illnesses. However, low-risk understandings may also be a health-risk factor as they may preclude a person from taking actions (e.g. to seek health information and to protect themselves from high risks) (Ferrer and Klein Citation2015, p. 84).

Overall, understandings of risk are not static but are dynamic and changing (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008). They are local-context specific (Hamilton Citation1985, p. 480; Greene et al. Citation2014; Marcon et al. Citation2015, p. 276), vary across heterogeneous communities and may be sensitive to temporal shifts (e.g. as new information emerges over weeks or months). In this respect, there is an argument for surveying affected communities throughout the lifecycle of a development.

Health effects of high-risk understandings

The health effects associated with high-risk understandings can be split into those associated with specific threats/risks, e.g. nuclear facilities, and those generically associated with the adverse effects of all industrial facilities. We address both here.

Specific public concerns focus on ‘nuclear power, disposal or transport of waste, facility siting, or accidents’ (Taylor Citation2012, p. 9), and may be associated with concern over the safety of nuclear facilities and operations (Venables et al. Citation2012). Public opinion on nuclear power and levels of support differs by country and fluctuates over time (House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Citation2012; Slovic Citation2012), but nuclear power is regularly viewed as being of high risk and low benefit (Slovic Citation2012).

Mental health effects may commence from the announcement of a proposal. Besides general anxiety related to fears of incoming workers (Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014), established health-risk understanding topics are:

Anxieties about developing cancer (‘cancer anxiety’) via chronic and acute exposures to invisible radiation, and pollution (Marcon et al. Citation2015, p. 270), contamination (Mueller Citation2010), and other multiple health effects, e.g. psychological (Barnett Citation2007; Mueller Citation2010), following major accidents, exposure to radioactive waste, nuclear weapons (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008). ‘Cancer anxiety’ has been established as a separate form of anxiety due to perceptions of cancer as the deadliest of diseases (Trumbo et al. Citation2007). Other illnesses experienced whilst living near a facility, that are not easily identified, may also be associated with the facility (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008).

The presence of a facility causing disruption to, or stigmatisation of individuals’ and communities’ affective relationships with the area (e.g. place-based aspects of personal identity: a reactor or damage to surrounding landscape could lead to ‘spoiled identities’ – stigmatised by narratives of contamination) (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008; Venables et al. Citation2012; Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014). In some countries/regions/localities, people’s psychosocial attachments to places, and local identities that incorporate the experience of places, are an important part of local cultures.

Stress related to construction and anxieties about the long-term stress of living with, and near to an operational facility.

Adverse health and well-being effects associated with understandings of risk

Health effects related to health-risk understandings from nuclear and other relevant industrial environmental hazards on health and well-being include:

Emotional effects, e.g. fear (Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014); dread (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008); anger (Taylor Citation2012; Ferrer and Klein Citation2015) (see Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000, for a full review).

Negative emotions may also affect health indirectly through associations with behavioural and other risk factors, e.g. smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, increased body mass, less physical activity, and higher levels of blood lipids and blood pressure (see Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000).

Anxiety (Luria et al. Citation2009; Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014); stress (Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000; Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014; Marcon et al. Citation2015, p. 270); trauma (e.g. when communities with a strong identity linked to a place are forced to relocate or remain due to development or accident) (Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014); depression (Lima Citation2004).

The suppression of emotion – for example, if individuals/communities are not given an opportunity to express their feelings – is a cumulative stressor that increases susceptibility to various illnesses over time (Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000, p. 216).

Possible associations between mental health conditions and physiological illnesses, e.g. chronic stress and illnesses such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and Type II diabetes (Duckett and Willcox Citation2015, p. 26); inconclusive links between situational and trait anxiety and hypertension (Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000, p. 223); psychological distress and depression of the immune system increasing susceptibility to infectious diseases, e.g. the common cold (Kubzandky and Kiwachi Citation2000, p. 225); depression as associated with various health conditions including poor metabolic control, macrovascular complications and retinopathy, infertility, temporomandibular joint pain, pruritus, increased functional impairment, poor quality of life, and inconclusive links with cancer and heart disease (see review in Carney and Freedland Citation2000).

Low-grade illnesses (e.g. headaches or hypertension) that can be exacerbated when there is uncertainty associated with a risk (Luria et al. Citation2009).

‘Solastalgia’ – a ‘psychoterratic’ psychological distress associated with a loss of control and a sense of powerlessness when a home environment/landscape that a person is attached to, and connects with their identity, no longer provides solace and a sense of security due to the construction of a facility (Albrecht et al. Citation2007). In severe cases, distress can escalate to more serious effect such as: drug abuse, physical illness and mental illness (depression, psychiatric illness, suicide) (Albrecht Citation2005).

Community division and conflict over differences in risk understandings (Wakefield and Elliott Citation2000; Walker et al. Citation2015).

Somatic effects (such as loss of sleep) (Wakefield and Elliott Citation2000).

Risk perception, together with environmental annoyance, can increase the likelihood of experiencing mental health symptoms, as annoyance can signify danger (Lima Citation2004).

Protective factors

A number of studies have shown that lower risk understandings may be held by people living near to the sites of existing nuclear facilities as opposed to proposed facilities (e.g. Pidgeon et al. Citation2008; Venables et al. Citation2012; Marcon et al. Citation2015, p. 271). In such cases, protective psychosocial factors may have acted as psychological buffers /sources of resilience to protect mental health (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008). These include:

A community-wide ‘sense of place’ (SOP) – a multi-component, affective mechanism describing the ways people form relationships to places. When SOP includes a facility as a factor shaping ‘place’, SOP may intensify in response to perceived threat/stigmatisation and mediate risk understandings so that they are lower (Venables et al. Citation2012). This is not the case in all studies of potentially environmentally hazardous developments (e.g. Lima Citation2004).

Perceived social and economic benefits leading nearby residents to underplay understandings of risk (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008; Taylor Citation2012; Jacquet and Stedman Citation2014), and coping by not thinking about it (management of ‘cognitive dissonance’) (Venables et al. Citation2012). People living further away may be more adversely affected (Taylor Citation2012). The ‘distinctiveness’ of a ‘spoiled identity’ may also be emphasised as a way of mitigating risk understanding and focusing on its benefits (Venables et al. Citation2012).

Social capital, networks and social support may unify a supportive, close-knit community and valorise feelings of safety, when compared to larger communities further away (Venables et al. Citation2012).

Increased familiarity with a facility and adjusting to life near a facility may reduce understandings of risk (e.g. Lima Citation2004) when there is an absence of accidents (Lima Citation2004; Venables et al. Citation2012) (e.g. reduction of ‘cognitive dissonance’ or occurrence of ‘cognitive adaptation’) (Lima Citation2004). A strong SOP may contribute to people’s desire to continue living near a newly built facility, even if they do not support it.

Conclusion

To recap our central argument, public understandings of risk (‘risk perception’) is an issue that is present in all IA contexts wherever and whenever a community may be affected by changes caused by a proposed development, e.g. adverse changes to the environment with potential health impacts. Living with an understanding of the risk of adverse health effects may, via individual attitudes towards developments, lead to mental health effects, ranging from low-level ones, e.g. fear, anger and anxiety up to disabling anxiety disorders and conditions such as ‘solastalgia’ which has, in severe cases, been associated with suicide (Albrecht Citation2005). Some mental health conditions, e.g. chronic stress, have been associated with physiological health conditions in the research literature.

Up until now, there has been no conceptual model or tool specifically devised for use within HIAs for analysing how individuals and communities develop and negotiate specific understandings of risk from different health ‘threats’ in dynamic contexts. Although common mental health symptoms and conditions such as anxiety and stress are referred to in the IA literature as being associated with public responses to development from the time a proposal is announced, these are health effects resulting from understandings of risk, not understandings in themselves. Developing an understanding of risk is a determinant of health or ill health and is a specific psychosocial process influenced by conscious processing of deliberative and affective risk responses. These risk responses are likely to be moderated by a variety of locally specific socio-cultural, demographic, temporal and other contextual factors, which together with internal psychological factors, will shape any health symptoms that people experience.

As each HIA is conducted in a unique local geography and social environment during a one-off period in time, social and environmental determinants of health are scoped and analysed in the local context, and the epidemiological and subjective community evidence of possible health effects in that context reviewed. The same treatment should be afforded to public understandings of risk as an important determinant of community health and well-being.

This paper has proposed a conceptual model of the processes involved in developing an understanding of the risks of a project in the context of HIA. This is a first step in enabling IA practitioners, especially HIA practitioners, to study the health effects of the ways in which communities understand risk. As communities ultimately live with, and often have any adverse effects from development imposed upon them by decision-making authorities, it is essential that in keeping with core HIA values, e.g. equity, democracy and sustainable development, that public understandings of risk are addressed holistically, democratically and in keeping with the ethos of the planetary health philosophies. In our second paper, we will propose consultation tools underpinned by our psychosocial model that IA/HIA practitioners can adopt.

Our model brings together approaches and concepts from HIA, psychology, sociology, anthropology and public health. It is causal in that it specifies the proposed directions of influence of various factors. It is therefore a model that is expected to predict as well as explain the factors underpinning understandings of risk about a project. The model could be used in various ways in HIA work including and not limited to: guiding practitioners and researchers in the types of factors to measure to better understand how people assess risk as well as attitudes towards a development project; and identifying the issues that are most likely to be influencing negative community sentiment towards a project and whether such sentiment subsequently changes in line with any variations or modifications in the development proposal and/or interventions to address negative community sentiment.

It is important that this model be tested empirically to enable those who may benefit in using the framework to have confidence in its validity. This empirical testing may also lead to model revisions. Testing the conceptual model would require a combination of workshops to qualitatively explore the local context and refine the list of moderators those which are locally relevant, and the use of existing questionnaire instruments and/or developing new, short questionnaires for constructs that have no readily available and usable instruments. The qualitative and quantitative data would be collected in a real-life HIA context, and the quantitative data would ideally be tested through structural equation modelling (SEM) to assess how well the model fitted the data. Our second paper will provide more information about using the conceptual framework and model outlined in this paper in a real-life HIA setting.

Contributions

Baldwin: conducted the background research, devised the conceptual framework and preliminary model, and wrote the first draft of the paper.

Rawstorne: helped develop the conceptual framework, produced , and co-authored the second draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. In this paper, we use the term ‘understanding of risk’ in preference to ‘risk perception’ which is more widely used in the academic literature. The term ‘perception’ is a standard term in psychology to describe a specific psychological process by which individuals process and make sense of sensory information. In this paper we combine theoretical concepts from clinical, social and environmental psychology into a conceptual model for use within the Impact Assessment (IA) context. Impact assessment bases conclusions upon different types of information. In IA, ‘public perceptions’ are placed alongside ‘scientific evidence’ and other forms of information (personal communication). the term ‘public perception’ can have a pejorative overtone and that the word ‘perception’ can imply that views that do not align with scientific analysis are given less credence. An understanding of a topic or an issue is something that can develop and that can be debated and shared. We note that this reflects broader and naïve societal views that the ‘natural’ sciences reflect factual truths whereas the social sciences are not. The irony here is that in the area of HIA, how individuals construct and make meaning of what is going on around them and the changes that may occur is key to whether they will experience psychological health effects. Our paper combines insight from academic disciplines and from practice-driven research on IA. We, accordingly, acknowledge both the academic preference for the term ‘risk perception’ and the usefulness of the term ‘understanding of risk’ in IA practice.

3. These mean that: (1) HIAs seek to provide opportunities for communities affected by a development to have a voice in and influence decision-making about it; (2) HIAs seek to address the inequitable distribution of health impacts on vulnerable people; and (3) HIAs promote development that takes its short- and long-term, direct and indirect impacts into account.

4. depicts the psychosocial model of public understanding of risk as described above. If using this model to inform field work, factors in rectangular boxes in the model represent variables that would be measured while experiential responses contained in the only oblong shape is a latent variable that is inferred statistically from the measurement of both deliberative and affective responses.

5. A top-down perspective on institutional factors that influence ‘risk perceptions’ is that each nation has a culture of risk that ‘comprises elements as diverse as the disaster history of the area, its economic situation, its demographical evolution, the insurance possibilities, the legal framework in force and the type of administrative organization’ (Angignard et al. Citation2014, p. 328). We acknowledge the importance of bureaucratic factors in shaping public discourses that circulate about risk, and no doubt the interactions between members of the public and officials involved in promoting a development proposal understood as potentially of high risk. However, the argument above was developed in relation to regions with intermittent natural disasters where insurance possibilities, legal frameworks and type of administrative organisations involved in public disaster relief are more likely to be widely known by lay people with experience of such disasters. In areas where an industrial development is proposed and a technological disaster has never occurred, we argue that individuals are less likely to be aware of these elements, e.g. most people would not willingly live near a nuclear power station if they thought that a disaster was highly likely, as good insurance would not save them from radiation exposure. Our model proceeds from an individual perspective in the context of a safe and healthy community where arguably public interactions with official personnel who represent institutions involved in the championing, governance, regulation or operation is their immediate experience of exposure to institutional factors via their representatives, and general perceptions of these institutions in ordinary times.

6. We used the term ‘biased’ in quotes as it is a technical term in clinical and social psychology, but we do not take a view on what the ‘truthful’ understanding of any risk is. As we point out above, this is inherently subjective depending on one’s worldview.

References

- Adler School of Professional Psychology. date unknown. Mental health impact assessment (MHIA). [accessed 2016 May 25]. https://www.adler.edu/page/institutes/institute-on-social-exclusion/projects/mhia/mental-healthimpact-assessment.

- Albrecht G. 2005. ‘Solastalgia’. A new concept in health and identity [online]. Vol. 3 PAN: Philosophy Activism Nature; pp. 41–55. [accessed 2016 May 28]. http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=897723015186456;res=IELHSS

- Albrecht G, Sartore GM, Connor L, Higginbotham N, Freeman S, Stain KB, Tonna A, Pollard G. 2007. Solastalgia: the distress caused by environmental change. Australasian Psychiatry. 15(1):41–55.

- Ampuero D, Goldswosthy S, Delgado LE, Miranda J. 2015. Using mental well-being impact assessment to understand factors influencing well-being after a disaster. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 33(3):184–194.

- Angignard M, Peters-Guarin G, Greiving S. 2014. Chapter 12 The relevance of legal aspects, risk cultures and insurance possibilities for risk management . In: T. van Asch, Corominas, J, Greiving, S, Malet, J.P, Sterlacchini, S eds.. Mountain risks: from prediction to management and governance, advances in natural and technological hazards research 34. Dordrecht: Springer ScienceCBusiness Media; pp. 327–340. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6769-012.

- Aven T, Renn O. 2009. On risk defined as an event where the outcome is uncertain. J Risk Res. 12(1):1–11.

- Baldwin C. 2014. Assessing impacts on people’s relationships to place and community in health impact assessment: an anthropological approach. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 33(2):154–159.

- Barnett L. 2007. Psychosocial effects of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Medicine, Conflict and Survival. 23(1):46–57.

- Baxter AJ, Vos T, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Whiteford HA. 2014. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol Med. 44:2363–2374.

- Birley M. 2015. Social determinants of risk perception. London: BirleyHIA; [accessed 2016]. For IAIA15, Florence: http://conferences.iaia.org/2015/Final-Papers/Birley,%20Martin%20-%20Social%20determinants%20of%20risk%20perception.pdf

- Brousselle A, Guerra SG. 2017. Public health for a sustainable future: the need for an engaged ecosocial approach. Debate S, de Janeiro R. Vol. 41. N. Especial; pp. 14–21, Mar 2017..

- Carney MR, Freedland KE. 2000. Depression and medical illness. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. USA: Oxford University Press; p. 191–212.

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. 2010. Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev. 30(7):879–889.

- Coggins T. 2018. Australia’s first positive residences. APSAA Student Accommodation Journal. 2(1):23–29.

- Cooke A, Coggins T, Heitor MJ, Virgolino A, Carreiras J, Nicolau BL. 2016. MWIA: the impact of a community-based intervention on the mental wellbeing of professionals working with those unemployed. Portugal: Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon.

- Cooke A, Friedli L, Coggins T, Edmonds N, O’Hara K, Snowden L, Stansfield J, Steuer N, Scott-Samuel A. 2010. The mental well-being impact assessment toolkit. 2nd ed. London: National Mental Health Development Unit.

- Cooke A, Stansfield J. 2009. Improving mental well-being through impact assessment. London: National Mental Health.

- Duckett S, Willcox S. 2015. The Australian healthcare system. South Melbourne. Victoria (Australia): Oxford University Press.

- Dustin DL, Bricker SK, Schwab KA. 2009. People and nature: toward an ecological model of health promotion. Leisure Sci. 32(1):3–14.

- Edelstein MR. 2003. Weight and weightlessness: administrative court efforts to weigh psycho-social impacts of proposed environmentally hazardous facilities. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 21(3):195–203.

- Ferrer R, Klein WM. 2015. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr Opin Psychol. 5:85–89.

- Greene G, Turley R, Mann M, Amlôt R, Page L, Palmer S. 2014. Differing community responses to similar public health threats: a cross-disciplinary systematic literature review. Sci Total Environ. 470:59–767.

- Hamilton LC. 1985. Concern about toxic wastes: three demographic predictors. Sociological Perspectives. 28(4):463–486.

- Higginbotham N, Connor L, Albrecht G, Freeman S, Kingsley A. 2007. Validation of an environmental distress scale. EcoHealth. 3:245–254.

- Hilding-Rydevik T, Vohra SRuotsalainen A, Pettersson A °,Pearce N, Breeze C, Hrncarova M, Lieskovska Z, PaluchovaK, Thomas L, Kemm J. 2005. Health aspects in EIA: D 2.2report WP 2, 2005. improving the implementation of environmental impact assessment: improvements in EIA implementation in Europe. Vienna, Austria, O¨ IR, O¨ sterreichischesInstitut fu¨ r. Vienna, Austria, O¨ IR: O¨ sterreichischesInstitut fu¨ r Raumplanung (Austrian Institute for RegionalStudies and Spatial Planning).

- Horton R. 2015. Comment: planetary health: a new science for exceptional action. The Lancet. 386L:1921.

- House of Commons Science and Technology Committee. 2012. Devil’s Bargain? Energy risks and the public. First report of session 2012–13. London: Authority of the House of Commons. [accessed 2016 May 25]. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmsctech/428/42802.htm

- Howe H. 1990. Predicting public concern regarding toxic substances in the environment. Environ Health Perspect. 87:275–281.

- Hung H-C, Wang T-W. 2011. Determinants and mapping of collective perceptions of technological risk: the case of the second nuclear power plant in Taiwan. Risk Anal. 31(4):668–683.

- Jacquet JB, Stedman RC. 2014. The risk of social psychological disruption as an impact of energy development and environmental change. J Environ Plann Manag. 57(9):1285–1304.

- Kågström M, Hilding-Rydevik T, Sjöberg I. 2013. Human health frames in EIA – the case of Swedish road planning. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 31(3):198–207.

- Kashpur VV, Afanasieva DO, Negrul SV, Kirpotin SN. 2015. Public attitude to the development of nuclear power industry and ecological risks (the case of the Tomsk region). Int J Environ Stud. 72(3):592–598.

- Kubzandky LD, Kiwachi I. 2000. Affective states and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. USA: Oxford University Press; p. 213–241.

- Lemyre L, Lee JEC, Mercier P, Bouchard L, Krewski D. 2006. The structure of Canadians’ health risk perceptions: environmental, therapeutic and social health risks. Health, Risk and Society. 8(2):85–195.

- Lima ML. 2004. On the influence of risk perception on mental health: living near an incinerator. J Environ Psychol. 24(1):71–84.

- Lima ML, Marques S. 2005. Towards successful social impact assessment follow-up: a case study of psychosocial monitoring of a solid waste incinerator in the north of Portugal. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 23(3):227–233.

- López-Navarro MA, Llorens-Monzonís J, Tortosa-Edo T. 2013. The effect of social trust on citizens’ health risk perception in the context of a petrochemical industrial complex. International. J Environ Res Public Health. 10:399–416.

- López-Rodríguez A, Escribano-Bombín R. 2013. Visual significance as a factor influencing perceived risks: cost-effectiveness analysis for overhead high voltage power-line redesign. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 31(4):291–304.

- Lucyk K. 2015. Report on mental health in health impact assessment. Calgary: Habitat Health Impact Consulting Corp. [accessed 2018 Jun 15]. www.habitatcorp.com

- Lucyk K, Gilhuly K, Tamburrini A, Rogerson B 2015. Mental health in health impact assessment. (Working paper).

- Luria P, Perkins C, Lyons M. 2009. Health risk perception and environmental problems: findings from ten case studies in north west England. Liverpool: Liverpool John Moores University. http://www.cph.org.uk/publications.aspx. [accessed 2016 May 25].

- Marcon A, Nguyen G, Rava M, Braggion M,G, Zanolin ME. 2015. A score for measuring health risk perception in environmental surveys. Sci Total Environ. 527–528:270–278.

- Marmot M. 2007. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet. 370(9593):1153–1163.

- Martikainen P, Bartley M, Lahelma E. 2002. Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 31(6):1091–1093.

- McLaren L, Hawe P. 2005. Ecological perspectives in health research. Epidemiol Community Health. 59:6–14.

- Mueller W 2010. A critical review of health impact assessments in Ontario’s nuclear industry. Unpublished Masters Thesis. Toronto (Ontario): Ryerson University. accessed 2016 May 25. digital.library.ryerson.ca/islandora/object/RULA%3A1865/datastream/OBJ/view

- Parkhill KA KL Henwood, NF Pidgeon, P. Simmons2011. Laughing it off? humour, affect and emotion work in communities living with nuclear risk. Br J Sociol. 62(2):324–346.

- Parsons R, Moffat K. 2014. Integrating impact and relational dimensions of social licence and social impact assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 32(4):273–282.

- Pidgeon N, Henwood K, Parkhill K, Venables D, Simmons P. 2008. Living with Nuclear Power in Britain: a mixed-methods study. UK: University of Cardiff and University of East Anglia. [accessed 2016 May 25]. https://www.kent.ac.uk/scarr/SCARRNuclearReportPidgeonetalFINAL3.pdf; https://www.kent.ac.uk/scarr/SCARRNuclearReportPidgeonetalFINAL3.pdf

- Roach I. 2013. Examining public understanding of the environmental effects of an energy-from-waste facility. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 31(3):220–225.

- Siegrist M, Visschers VHM. 2013. Acceptance of nuclear power: the Fukushima effect. Energy Policy. 59:112–119.

- Slovic P. 2012. The perception gap: radiation and risk. Bull At Scientists. 68(3):67–75.

- Stewart AG, Luria P, Reid J, Lyons M, Jarvis R. 2010. Real or illusory? Case studies on the public perception of environmental health risks in the North West of England Int. J Environ Res Public Health. 7:1153–1173.

- Taylor M. 2012. Review and evaluation of research literature on public nuclear risk perception and implications for communication strategies. Consultancy Project for the Australian Uranium Association. Sydney: University of Western Sydney. [accessed 2016 May 25]. http://www.minerals.org.au/file_upload/files/reports/7.5D_Download_Report_Nuclear_Risk_Perception_Literature_Review_Report_Final.pdf

- The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. 2015. Safeguarding human health in the anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–lancet commission on planetary health. The Lancet. 386: 1973–2028.

- Trumbo CW, McComas KA, Kannaovakun P. 2007. Cancer anxiety and the perception of risk in alarmed communities. Risk Anal. 27(2): 337–350. [accessed 2016 May 25]. disaster.colostate.edu/Data/Sites/1/cdra-research/trumboetal2007canceranxiety.pdf

- Twigger-Ross C, Uzzell D. 1996. Place and identity processes. J Environ Psychol. 16:205–220.

- Venables D, Pidgeon NF, Parkhill KA, Henwoo KL, Simmons P. 2012. Living with nuclear power: sense of place, proximity, and risk perceptions in local host communities. J Environ Psychol. 32:371–383.

- Wakefield S, Elliott SJ. 2000. Risk perception and well-being: effects of the landfill siting process in two southern Ontario communities. Soc Sci Med. 50:1139–1154.

- Walker C, Baxter J, Ouellette D. 2015. Adding insult to injury: the development of psychosocial stress in Ontario wind turbine communities. Soc Sci Med. 133:358–365.

- Watts, Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, Blackstock J, Byass P, Cai W, Chaytor S, Colbourn T, Collins M, et al. 2015. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. The Lancet. 386:1861–1914.

- Wlodarczyk TL, Tennyson J. 2003. Social and economic effects from attitudes towards risk. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 21(3):179–185.

- World Health Organization. 1999. Gothenburg Consensus Paper.

- Wright J, Parry J, Mathers J. 2005. Participation in health impact assessment: objectives, methods and core values. Bull World Health Organ. 83:58–63.