ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of Mongolia’s EIA processes for nomadic-pastoral land use(rs) (NPLU(rs)). NPLU(rs) are often overlooked in many spatial policies, so the justification for this study is to improve the EIA processes regarding impacts on NPLU. This is the first study to examine EIA effectiveness for NPLA(s) specifically. It employs a Likert survey of 50 respondents based on the framework of Hanna and Noble (2015). The results of this study indicate that there is indeed an immense gap between how EIA should be carried out and its implementation processes in practice. We find that although the EIA framework has good ambitions and is relying on a sound legislative and institutional set-up in Mongolia, it lacks stakeholder confidence, participation and the effectiveness in mitigating both social and environmental impacts associated with NPLU failing to ensure substantive gains to pastureland resources. Improvements are especially required in EIA practice, impact prediction methods suitable for dynamic land use, capacity building, transparency, EIA integration into spatial planning, and stakeholder engagement.

1. Introduction

Since its introduction in a legislative form in 1969, the use and relevance of environmental assessment has significantly increased (Morgan Citation2012; Pope et al. Citation2013) as a component of land and environmental interventions. Over time, the environmental impact assessment (EIA) processes has become more elaborate and comprehensive, and have thus become more supportive for policy innovations. As a result, in more than 190 countries EIA has become a legally required instrument for any environmental intervention (Sadler Citation1996; Morgan Citation2012). At the same time, however, there has always been a debate about the effectiveness of EIA, and about its (sometimes partisan) role in decision-making (Cashmore et al. Citation2004; Rozema and Bond Citation2015; Banhalmi-Zakar et al. Citation2018; Pope et al. Citation2018). This includes the question whether EIA is effective in addressing impacts on all types of land use and land users, such as nomadic-pastoral land use (NPLU) (Byambaa and de Vries Citation2019).

Nomadic pastoralism is a land-based production system where herds move extensively in rangelands (Blench Citation2001; Allen et al. Citation2011). Moreover, pastoralism is the most sustainable food system on the planet practised on more than a quarter of the world’s land surface by almost 500 million people and it plays a major role in safeguarding natural capital (McGahey et al. Citation2014). However, drivers such as growth of populations and consumption, the commodification of nature, and climate changes are transforming land use and land tenure around the world, causing loss and fragmentation of rangelands (Reid et al. Citation2014). Examples include pastoralism in Mongolia where it is the prevailing form of land use (Lkhagvadorj et al. Citation2013) and a significant contributor to its national GDP (NSO Citation2018). Rangelands have been significantly affected by degradation, caused by both natural processes as well as human activities such as mining and herding in Mongolia (MET Citation2017). Since the mining industry’s boom, available pasture has increasingly become fragmented and herders in mining regions have lost a sizable amount of their pasture and livelihood due to competing land uses such as the expansion of the mining industry (Cane et al. Citation2015). Moreover, there were cases where complaints were filed by herders to international organisations like Office of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman regarding negative impacts of mining projects on their traditional nomadic lifestyle and rangeland yields (CAO Citation2013).

EIA is the key process which identifies potential impacts of such activities at an early stage. Besides this, it suggests possible mitigation measures to address associated adverse or unwanted impacts (Morris and Therivel Citation2009). However, Byambaa and de Vries (Citation2019), who conducted a literature study on EIA and pastoralist land use, argue that the rationalist and decision-making theories as well as static land use-oriented methods underlying the current EIAs restrict them to sufficiently mitigate impacts on dynamic land use in nomadic-pastoralism. To understand this misfit in depth, we advance these earlier findings by looking at the actual practice. This article zooms in to evaluating the effectiveness of the EIA processes from the perspective of nomadic-pastoral land users (NPLU(rs)) in a particular case of nomadic-pastoralism in Mongolia to identify specific factors and defects in the EIA processes which contribute to the shortcomings of EIA with regard to addressing impacts on NPLU. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in increasing the livestock productivity and pastoralists’ income through secure and equal access to land, and the newly-adopted United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN Citation2015) recognised this issue as one of the goals of sustainable development. Thus, there is a need to advance EIA such that it can better connect to the needs and specificities of pastoralism. In view of this need, the objective of this paper is to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of Mongolia’s EIA processes for NPLU(rs). This is the first case study which investigates the effectiveness of EIA with respect to pastoralism. Based on this evaluation, the study suggests possible solutions to make Mongolia’s EIA more effective and inclusive for NPLU(rs).

2. Key features of Mongolia’s EIA processes

The Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) of Mongolia began to conduct screening in 1994 and introduced EIA officially in 1998 by adopting the Law on EIA. Two major revisions have been made in 2001 and 2012 to this law since its introduction. The key revisions include introduction of the deposit of environmental restoration ‘bonds’, cumulative impact assessment, strategic environmental assessment, biodiversity offsetting, and public participation in impact assessment (IA). The purpose of this law is to ensure the citizens’ rights to a healthy and safe environment guaranteed by the Constitution of Mongolia, to protect the environment, and to regulate relations concerning the environmental assessment processes and decision-making related to policies, programmes, plans, and projects implemented at local and regional levels (SGH Citation2012a). EIA is applied to new projects as well as to restoration and expansion of existing projects prior to their implementation.

Key stages in the EIA process in Mongolia include screening (general EIA), detailed EIA, review, and follow-up stages, and the process is administered by the MET and its local offices. The screening conducted by the MET at the commencement of the EIA process makes four types of decisions: the initiative is rejected on the grounds that it does not meet conditions related to legal, planning, policy and technology issues; the initiative can be implemented without a detailed EIA; the initiative receives approval for implementation subject to specific conditions without further assessment; or a detailed EIA is required. Scoping is merged with screening and it requires EIAs to address impacts that have a significant effect on the environment and human health as well as to consider possible alternatives. However, scoping does not involve any interested stakeholders. According to the EIA law and regulations, the public is engaged in the EIA process during the detailed EIA and follow-up stages. Detailed EIAs are conducted by licenced legal entities, and reviewed and approved by a Technical Board under the MET (SGH Citation2012a). Environmental monitoring and auditing are the main EIA follow-up activities (SGH Citation2012b). In Mongolia 5,376 EIAs have been approved between 1995 and 2019 and 20.6% of them are EIAs conducted in the mining sector (MET Citation2019).

3. Methods

3.1. Effectiveness of EIA

The concerns about EIA practices have resulted in the development of a substantial body of research debating the issue of EIA effectiveness (Cashmore et al. Citation2004; Loomis and Dziedzic Citation2018). Though this article does not claim to synthesise all literature on this debate, we highlight a number of seminal articles. The development of the EIA effectiveness discourse began (Pope et al. Citation2018) with the release of Sadler (Citation1996)’s ‘International Study of the Effectiveness of Environmental Assessment’ in 1996 in which procedural, substantive and transactive dimensions of effectiveness were distinguished. The procedural dimension measures whether EIA conforms to established provisions and principles. Substantive dimension examines whether EIA achieves its purpose of supporting decision-making and protecting the environment. Transactive effectiveness looks at whether EIA delivers its outcomes at the least cost in the minimum time possible. Subsequent studies suggested other dimensions as evaluation criteria for IA, such as normative (how individual and social norms are achieved in IA) effectiveness (Baker and McLelland Citation2003), pluralism (whether assessment takes different views), and knowledge and learning (whether the assessment process facilitates knowledge sharing) (Bond et al. Citation2013). Loomis and Dziedzic (Citation2018) note that the first four dimensions can refer to a wider EIA system. Pluralism and knowledge and learning were included in a framework developed by Bond et al. (Citation2013) for evaluation of sustainability assessment practice in different jurisdictions. Thus, these two dimensions can be applied to a macro level evaluation as well (Pope et al. Citation2018). These subsequent contributions suggest that there is no uniform or standard framework in use, but that effectiveness is an extendable and scalable concept.

A pragmatic way to look at effectiveness is about how well EIA works in relation to macro or microsystems, whereby macro systems review EIA experience, activities or outcomes and micro systems address specific elements such as decision audits, component-specific evaluations (Doyle and Sadler Citation1996; Sadler Citation1996). In their recent study, Pope et al. (Citation2018) refined Bond et al. (Citation2015)’s framework (a modified framework of Bond et al. (Citation2013)) to make it more applicable to IA in general and proposed to replace the normative effectiveness, pluralism, knowledge and learning with legitimacy which measures whether the EIA processes are perceived to be legitimate by various stakeholders.

3.2. Measuring effectiveness of EIA for nomadic-pastoral land users

Byambaa and de Vries (Citation2019) derive that aspects of land quality and herders’ participation in EIA are the most important issues for NPLU with respect to effectiveness of EIA. Land quality relates to results in environmental protection, thus can be measured by substantive criteria. Whereas participation in EIA relates to stakeholder confidence as well as to established processes. Hence, it is measured by procedural and legitimacy dimensions. Transactive effectiveness criteria are less frequently used (Bond et al. Citation2015) and not directly affect the interest of NPLU(rs), therefore, this study did not consider the transactive dimension of EIA.

Existing frameworks applicable to evaluation of EIA effectiveness include those discussed and presented by Arts et al. (Citation2012); Bond et al. (Citation2013); Bond et al. (Citation2015); Chanchitpricha and Bond (Citation2013); Hanna and Noble (Citation2015); Pope et al. (Citation2018); Wood (Citation2003). The frameworks developed by Chanchitpricha and Bond (Citation2013) and Wood (Citation2003) do not include criteria on substantive effectiveness. Criteria defined in the frameworks of Bond et al. (Citation2013), Bond et al. (Citation2015), Arts et al. (Citation2012) and Pope et al. (Citation2018) are not detailed and few in number. Therefore, for this evaluation, we choose to employ Hanna and Noble (Citation2015)’s framework as it includes the most comprehensive detailed criteria on substantive, procedural and legitimacy dimensions that are necessary for this evaluation. This framework consists of 49 criteria related to nine IA themes: stakeholder confidence, decision-making, gains to environmental management and protection, comprehensiveness, evidence-based decisions, accountability, participation, legal foundation for IA, and capacity and innovation. For the purpose of our evaluation, we applied the Likert survey (Likert Citation1932) and derived 81 survey questions (Likert statements) from these 49 criteria following steps shown in .

Table 1. Approach applied to formulate survey questions.

For the Likert statements, we choose scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to evaluate respondents’ attitude and opinion (Jamieson Citation2004) on the effectiveness of Mongolia’s EIA processes in addressing impacts related to NPLU. The questionnaire also included 20 open-ended questions to obtain respondents’ insights on solutions to Mongolia’s EIA processes. Thus, the evaluation employs multi-strategy combining both quantitative and qualitative approaches to enhance or build upon our research findings (Bryman Citation2006).

In the following step, a survey questionnaire containing questions and statements mentioned above are completed by 50 respondents who represented various stakeholder groups with broad experience in rangeland management and EIA. The survey was sent by email to members of two associations of EIA and environmental management professionals, officers of central and local government departments in charge of EIA, members of environmental NGOs, and university lecturers. The survey included questions which might receive critical responses. Thus, we assured respondents that the information provided by them will be kept confidential. The idea of executing such a long survey – which at times took almost 4 h to complete – is indeed a risky and ambitious data collection strategy. However, the respondent rate and respondent type also indicate how serious and committed they were despite the prior warning of the length of the survey. EIA consultants from private sector accounted for 38% which were the majority of survey respondents and 18% of the total respondents were from research organisations. Participants from non-government organisations and community groups accounted for 24% and government organisations accounted for 20% of the total respondents, respectively.

Respondents answered to each statement in two ways. Firstly, they had to rate how certain issues are addressed in the existing EIA laws and regulations and secondly, they were required to evaluate how in their opinion each statement sufficiently emerged during the execution of EIAs. After obtaining the responses, we analysed answers to the Likert statements using statistical methods. Likert surveys are used widely and yet there seems to be a lack of statistical tools for analysis of Likert data (Gosavi Citation2015). However, when using Likert survey, it is recommended that authors determine how they will describe and analyse their data in their methodology (Sullivan and Artino Citation2013). All the frameworks for evaluation of EIA effectiveness discussed above do not measure outcomes systematically in a qualitative or quantitative way. However, we attempted to conclude quantitatively whether Mongolia’s EIA processes are effective for NPLU(rs) in terms of procedural, substantive or legitimacy dimensions. To quantify effectiveness, firstly, we grouped survey statements into three dimensions of effectiveness. The statements were also classified whether they are directly related to the issues of NPLU, or generally related to the EIA process, or the statements were added for additional comparison analyses. We calculated then how many percentages of all respondents agreed or disagreed (calculated separately for each of seven Likert scale points) with each of the statements. We aggregated then positive (somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) and negative responses (somewhat agree, agree, strongly agree) for each statement. If the positive values exceed the negative values, we considered it that respondents perceive the EIA process in Mongolia more effective for NPLU(rs). To the contrary, in cases if the negative values exceed the positive values, it is interpreted that respondents perceive the process rather ineffective. For the responses to the open-ended questions, we relied on content analysis in order to infer the meaning of their answers to evaluation questions and in order to triangulate with other comments made by each of the survey respondents. This method follows the same procedure as described by Fink (Citation2017).

4. Results and discussion

Survey results were aggregated and analysed in four parts. The first part evaluates the procedural effectiveness of the EIA process in Mongolia with regard to addressing impacts on NPLU. It will then evaluate the substantive effectiveness looking at whether EIA fulfils its purpose of protecting the environment. The third part examines legitimacy of the EIA process from the perspective of NPLU(rs). In the final part, a summary of the results of open-ended questions is presented and solutions to improvement of the EIA processes for NPLU(rs) are suggested.

4.1. Procedural effectiveness of the EIA process in addressing impacts on NPLU

This subsection sets out how the assessment of the procedural effectiveness of the EIA process in Mongolia for NPLU(rs) took place. For our evaluation, we applied 38 criteria. The results are presented and discussed below.

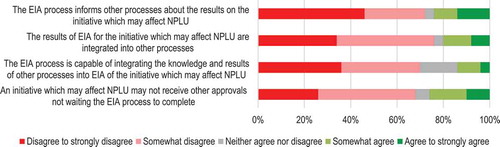

The first question in this study sought to determine whether the EIA process in Mongolia is integrative and linked to approval decision-making when addressing the issues related to nomadic-pastoralism. More than 70% of respondents somewhat to strongly disagree that the results of the EIA process are clearly accounted for in the ultimate decision to go ahead with the initiative (median = 3, SD = 1.3) which may have an adverse effect on NPLU. This indicates that the EIA decision-making does not consider information about adverse impacts on NPLU although 88% and 78% of respondents agreed that according to the EIA legislation, the intent of the EIA process is to advise decision-making which may affect NPLU(rs) (median = 6, SD = 1.3). Particularly, compared to respondents originating from the government sector (30%), only 8% of community group respondents somewhat to strongly agreed that the results of the EIA process are clearly accounted for in the decision which was the lowest percentage among respondents’ groups. There are several possible explanations for this result. It may be related to poor uncertainty disclosure in EIA and different perceptions about uncertainty by stakeholders (Leung et al. Citation2016), or lack of trust in EIA as, for example, several respondents commented in their answers to the open-ended questions that NPLU(rs) view EIA as a flawed process designed to ensure project approval. The next statements () were about the capacity of the EIA process to inform and be integrated into other subsequent or coincident environmental approval and review processes when dealing with initiatives which may affect NPLU.

Results show that nearly 70% of all respondents somewhat to strongly disagree with these four statements shown in . Although 58% (median = 5, SD = 1.7) of all respondents somewhat to strongly agree that in legal documents, the EIA process is designed to demonstrably inform other environmental approval and review processes about the results on the initiative which may affect NPLU(rs), 72% (median = 3, SD = 1.7) of respondents perceive that in practice this approach is not implemented. Moreover, even less respondents agreed that the results of EIA are integrated into other approval and review processes and the EIA process is capable of integrating the knowledge and results of other processes into EIA of the initiative which may affect NPLU without unduly influencing its outcomes. These findings indicate a clear perceived gap between formal procedures and actual practice. This gap is, in particular, felt for NPLU(rs). If their existence is already hardly acknowledged in the formal process the actual process is likely to neglect their interests all together.

Finally, 68% (median = 3, SD = 1.5) of respondents indicate that an initiative which may affect NPLU can proceed through other approval processes or receive other approvals not waiting the EIA process to complete and the initiative to get approved although 66% of respondents suggest that according to EIA related laws, this action is not possible (median = 5, SD = 1.5).

The next question of the survey was concerned with evidence-based decision-making in EIA. The most challenging problem in EIA concerns its ability to predict impacts and to address issues of uncertainty in complex and dynamic environmental systems (Noble Citation2000). Results show that only 14% of participants somewhat to strongly agree with EIA’s ability to disclose and acknowledge uncertainties and assumptions about data, system behaviours and future conditions related to NPLU (). This result suggests that in most cases, uncertainties about adverse impacts on NPLU are not disclosed and acknowledged and therefore, in EIA, impacts on NPLU are not predicted appropriately and sufficiently if there are uncertainties with regard to project impacts.

Table 2. Evaluation of evidence-based decision-making in EIA for NPLU(rs).

Uncertainties in EIA are related not only to the rationalist model of planning and decision-making in which EIA is firmly based (Morgan Citation2012) but also to the unknowns within the impact prediction methods (Tenney et al. Citation2006). A review conducted by (Leung et al. Citation2015) on uncertainty research in IA notes that notwithstanding early guidance on uncertainty treatment in IA from the 1980s, there is no common, underlying conceptual framework used in identifying and addressing uncertainty in IA practice. The majority of respondents also somewhat to strongly disagree that EIA discloses (82%, median = 3, SD = 1.1) and acknowledges (74%, median = 3, SD = 1.0) uncertainties and assumptions about data, system behaviours and future conditions of NPLU sufficiently. Moreover, respondents perceive that EIA is weak in predicting impacts associated with NPLU as nearly 70% somewhat to strongly disagree that impact predictions about NPLU are formulated in such a way that they can be tested or used for follow-up (median = 3, SD = 1.3).

In the following part of the survey, respondents were asked about accountability, legal framework for EIA, and capacity and innovation. Results related to questions on comprehensiveness show that the majority of respondents (66%) view EIA as a mandatory process which cannot be avoided. They somewhat to strongly agree that roles and responsibilities in the assessment, review and decision-making processes (80%, median = 5, SD = 1.5) and for post-EIA (82%, median = 5.5, SD = 1.4) are clearly identified in the Mongolian EIA laws and regulations. However, far fewer respondents agree that requirements such as consideration of alternatives (38%, median = 3, SD = 1.6) and assessment of cumulative effects (20%, median = 3, SD = 1.5) on NPLU are implemented in practice effectively although these issues are required by EIA legislation. However, 74% (median = 5, SD = 1.3) somewhat to strongly agree that the EIA process has an effective monitoring system which follows up on the implementation of measures for mitigation of adverse impacts on NPLU including audit system (54%, median = 5, SD = 1.2).

It can be noted that the legal framework for EIA is well established in Mongolia as 98% of respondents somewhat to strongly agree that EIA is appropriately codified in law (median = 6.5, SD = 0.8) and 86% of respondents perceive that the framework provides clarity for stakeholders with respect to applicability, assessment requirements, disclosure requirements, and process components, reporting and decision-making (median = 6, SD = 1.1). Moreover, nearly 80% of respondents somewhat to strongly agree that the EIA process outlines provisions for enforcement (median = 6, SD = 1.3). However, results suggest that nearly 60% of respondents somewhat to strongly disagree that the EIA system provides decisions (for approvals, conditions, rejections, exemptions and inclusions) that may be appealed by NPLU(rs) based on questions of process veracity or interpretation of law.

Although most respondents agree that the EIA process contains a legal base for participation and accountability requirements (68%, median = 5, SD = 1.4), only 38% of respondents indicate that various communication formats are used in EIA to enhance participation of NPLU(rs) (median = 3, SD = 1.6). Results suggest that respondents are not confident with financial and human resource capacity of EIA agencies as only 10% of respondents somewhat to strongly agreed that the EIA process provides sufficient financial resources to review agencies to ensure the integrity, effectiveness of, and confidence in the process (median = 3, SD = 1.2) and 28% of respondents somewhat to strongly agree that the EIA process is administered by competent authorities (median = 3, SD = 1.5).

Furthermore, more than half of government respondents (60%, median = 5, SD = 1.3) as well as private (53%, median = 5, SD = 1.9) organisation respondents somewhat to strongly agreed that the EIA process and its supporting institutional framework are flexible, adaptive and open to new and innovative tools and approaches to assessment and evaluation. In contrast, 67% of respondents from community and non-governmental organisations (median = 3, SD = 1.3) and 78% of academic respondents (median = 3, SD = 1.2) somewhat to strongly disagreed with this statement.

We analysed 38 questions to evaluate the procedural effectiveness. There were 27 negative responses which disagreed with the statements when respondents were asked to evaluate EIA practice. This result suggests that the EIA process in Mongolia has not been following established provisions and principles when addressing the issues related to NPLU and has not been effective in practice in the past for NPLU(rs).

4.2. Substantive effectiveness of the EIA process in addressing impacts on NPLU

In this sub-section, we evaluate the substantive effectiveness of the EIA process in Mongolia from the perspective of NPLU(rs). We applied five criteria to evaluate the substantive effectiveness and five additional criteria were used to compare respondents’ perceptions of EIA’s roles in addressing impacts on the environment and NPLU.

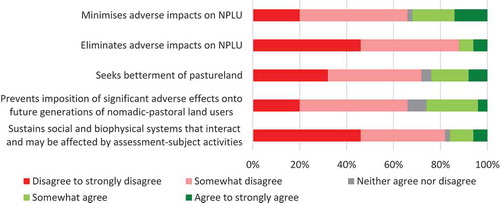

Results show that with regard to EIA’s role in environmental protection, 32% of respondents somewhat to strongly agree that the EIA process minimises adverse impacts on NPLU (median = 3, SD = 1.4) whereas nearly 90% of respondents somewhat to strongly disagree that EIA eliminates adverse impacts (median = 3, SD = 1.2) (). Moreover, nearly 70% of respondents somewhat to strongly disagree that in practice, the EIA process seeks betterment of pastureland resources (median = 3, SD = 1.3) and prevents imposition of significant adverse effects onto future generations of NPLU(rs) (median = 3, SD = 1.2).

Furthermore, a comparison of results shows that respondents have significantly different views about how EIA fulfils its substantive purpose (). The majority of respondents agree that environmental legislation includes provisions which require the EIA processes to minimise and eliminate adverse impacts on the environment and NPLU as well as seek betterment of the environment including pastureland. However, most respondents perceive that these provisions are not implemented in practice. In particular, respondents’ perception differed on the effectiveness of EIA in addressing negative impacts on the environment and NPLU. The majority of respondents perceive that the existing legal EIA framework pays less attention to the issues related to NPLU than to general environmental issues. Similarly, in practice, impacts associated with NPLU are addressed also in a less effective way than impacts on the environment in general. Firstly, it may be related to lack of appropriate impact prediction methods for NPLU which incorporate dynamic character of nomadic-pastoralism (Byambaa and de Vries Citation2019). Moreover, it may also be related to lack of comprehensive consideration of both environmental and social impacts into the EIA process in Mongolia.

Table 3. Comparison of results on the substantive purpose of EIA.

Although the legislative context has historically favoured biophysical impacts in most jurisdictions, social impacts are assessed usually within EIA (Esteves et al. Citation2012). However, neither the legal framework for EIA nor EIA practice in Mongolia integrates and addresses the social impacts for NPLU. More than 80% of respondents somewhat to strongly disagreed that EIA sustains social and biophysical systems that interact and may be affected by assessment-subject activities (median = 3, SD = 1.3). A number of responses to our open-ended questions also noted that the existing EIA process focuses mainly on environmental issues. This indicates that the majority of participants perceive EIA as a process which does not consider social and biophysical system as a complex system that interacts with each other. As rangelands are linked social-ecological systems (Reid et al. Citation2014), it is particularly crucial to assess social effects in connection with environmental impacts in the case of pastoralism.

Nevertheless, quantitative results of responses to all five criteria used in the evaluation of substantive effectiveness showed that the EIA process in Mongolia has not been effective and successful in eliminating negative impacts on NPLU and promoting longer-term and substantive gains to pastureland resources.

4.3. Legitimacy of the EIA process from the perspective of NPLU(rs)

We applied 27 criteria to evaluate whether the EIA process is perceived legitimate in Mongolia in addressing impacts on NPLU. Firstly, we examined stakeholder confidence and decision-making in the EIA processes. Results show that only 10% of respondents somewhat to strongly agreed that the EIA process is objective in practice. However, 40% of respondents somewhat to strongly agreed that the EIA process is intended to be objective as how it is designed in the Mongolian legal and institutional system. All academic and community group respondents perceive that the EIA process is not objective. By contrast, 10% and 30% of respondents representing the government and private organisations view the EIA processes as objective, respectively. Similar responses were given by the stakeholder groups to our next question on stakeholder confidence in EIA. Respondents representing the government (40%) and private organisations (27%) have more confidence that other processes do not predetermine the EIA decision and major projects cannot circumvent the EIA process whilst only 8% of participants from communities indicate that this is the case and none of the academic organisation respondents agreed with this statement. Such doubt and distrust may be occurred due to the current sociopolitical situation in Mongolia as answers to our open-ended questions note that there are concerns over political and corruption issues likely to influence the EIA decisions. On the other hand EIA is often perceived ineffective or flawed due to its limited roles in consent and design decisions, and the gap between high expectations of EIA and poor practical performance remains significant (Cashmore et al. Citation2004; Nykvist and Nilsson Citation2009; Zhang et al. Citation2013; Rozema and Bond Citation2015; Banhalmi-Zakar et al. Citation2018). Thus, it is possible that such perception affects stakeholder confidence in EIA. Moreover, EIA encompasses the diversity of scientific disciplines and models (Cashmore et al. Citation2004; Wallington et al. Citation2007). Hence, lack of confidence in the EIA system may be also related to its complexity as only 22% of all respondents think that the EIA process is understood by stakeholders. Particularly, all NGO and community group respondents perceive that the EIA process is not understood by stakeholders whilst half of the government respondents indicate that stakeholders understand the EIA process.

The next section of the survey was concerned with participation of NPLU(rs) in the EIA process. The dominant view of scholars and practitioners is that public participation in EIA is highly desirable yet that the key practical challenge is to make participants more effective (O’Faircheallaigh Citation2010). Pohjola and Tuomisto (Citation2011) argue furthermore that the discourse on participation in environmental assessment focuses too much on processes and procedures, and too little on the purpose, outcome and effectiveness in policymaking. Respondents mostly disagreed with the statements regarding effective participation of herders in EIA. Mongolia’s legal EIA framework prescribes public participation (46%, median = 3, SD = 1.5). However, the majority of respondents somewhat to strongly disagreed that there is open (74%, median = 3, SD = 1.3), easy (92%, median = 3, SD = 0.9), accurate (86%, median = 3, SD = 0.9) and complete (86%, median = 3, SD = 0.9) information for NPLU(rs) early and throughout the EIA processes. NPLU(rs) are simply not informed about how they are engaged in the EIA process (56%, median = 3, SD = 1.6) and how their participation is accounted for in the decision-making processes (66%, median = 3, SD = 1.5).

Over 50% of respondents indicate that hearings and other similar deliberations are open to NPLU(rs) (median = 5, SD = 1.6). Compared to other three groups, only 11% of research organisation respondents indicated that such EIA meetings or consultations are open to herders (median = 3, SD = 0.9). By contrast, the majority of EIA consultants (74%, median = 6, SD = 1.5) and government respondents (60%, median = 5, SD = 1.5) who are often involved in engaging the public in the EIA processes somewhat to strongly agree that EIA hearings are open to the public. Such difference clearly reflects how openness is viewed from an academic’s perspective compared to practitioners working in the field. Nonetheless, 42% of non-governmental organisation respondents and community groups who are representing the NPLU(rs) in our study somewhat to strongly agreed that EIA hearings are open for them (median = 3, SD = 1.7). Most respondents perceived that participation opportunities are not known to herders (88%, median = 3, SD = 1.0). Moreover, the majority of respondents somewhat to strongly disagree that the EIA process provides information for NPLU(rs) through various formats (78%, median = 3, SD = 1.3) and allocates sufficient resources and time to support participation process (88%, median = 2, SD = 1.0). More than half of the respondents also disagree that the EIA process prevents unjustified limitations to open deliberation and presentation of evidence for NPLU(rs) (56%, median = 3, SD = 1.6).

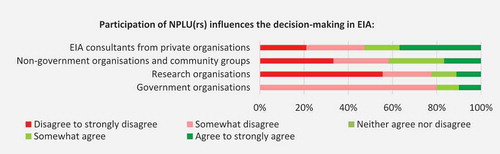

The third set of criteria in this section examined how participation of NPLU(rs) influences the decision-making in EIA. Responses of all survey respondents (72%, median = 5, SD = 1.3) including government group respondents (80%, median = 5, SD = 0.9) show that Mongolian laws and regulations on EIA ensure herders’ participation in the decision-making in EIA. However, responses significantly differed when respondents answered this same question considering how this issue is dealt in practice. More than half of respondents (62%, median = 3, SD = 1.6) somewhat to strongly disagree that in practice NPLU(rs) influence decisions during the EIA processes. Moreover, as reveals, compared to government and research organisations (20%, median = 3, SD = 1.1; 22%, median = 2, SD = 1.7), more respondents representing the private organisations and community groups (53%, median = 5, SD = 1.1; 42%, median = 3, SD = 1.6) perceive that the participation of NPLU(rs) influences the decision-making in EIA.

Furthermore, 50% of respondents indicate that the participation of NPLU(rs) in the EIA processes improves the quality of the proposal and affect the assessment of the initiatives (median = 4.5, SD = 1.6). In particular, 77% of research organisation respondents (median = 5, SD = 1.2), 58% of EIA consultants (median = 5, SD = 1.5) and 40% of government respondents (median = 3, SD = 1.3) somewhat to strongly agreed that EIA benefits from the participation of NPLU(rs) indicating that they acknowledge use of herders’ knowledge in EIA. However, only 25% of community groups (median = 3, SD = 1.5) perceive that their participation improves the quality of the proposal and affects the EIA processes.

The most obvious finding to emerge from this study is a contrast between the existing EIA framework and its implementation in practice. As explained in the Methods section, respondents were asked to evaluate the survey statements in two ways. Results of 16 criteria out of 27 were positive when respondents evaluated how the issues related to legitimacy of EIA are addressed in the existing legal EIA system. It can, therefore, be assumed that the EIA process is perceived legitimate by the respondents. However, responses to 23 criteria out of the same 27 criteria were negative when respondents evaluated EIA practice. This also accords with results of the open-ended questions where respondents raised a number of issues related to weak EIA practice. By contrast to the previous finding, this result suggests that the EIA process is not seen legitimate by the stakeholders. Taken together, although there is some strength in the legal framework for EIA in Mongolia, poor quality of EIA practice causes lack of stakeholder confidence in EIA and create perception that the EIA process is dysfunctional.

4.4. Effectiveness of the EIA process from the perspective of NPLU(rs)

Respondents identified a many number of problems which the EIA process is facing in Mongolia. Many issues were related to poor quality of EIA practice (insufficient public participation, poor consideration of cumulative impacts and alternatives, follow-up system is not effectively linked to the subsequent decision-making processes, etc.), ineffective law enforcement, capacity of EIA agencies and practitioners. These problems, in general, affect the effectiveness of the EIA process, thus, influence the issues of NPLU as well. Moreover, the survey found the following problems specifically related to NPLU:

Lack of NPLU(rs) confidence in EIA

Lack of suitable impact prediction methods for dynamic land use

NPLU issues are not clearly accounted for in the decision-making in the EIA process

Social aspects of NPLU are not sufficiently addressed in EIA

Respondents suggested a number of solutions to these problems (). Many responses were about ensuring meaningful engagement with NPLU(rs) throughout the EIA processes and using knowledge of NPLU(rs) in impact prediction. Respondents also suggested that there is a need to improve impact prediction methods for NPLU and guidelines and regulations on stakeholder engagement in EIA for NPLU.

Table 4. Suggestions by respondents to improve the EIA process in Mongolia.

Integrating environmental and social concerns into the spatial planning process as well as all levels of decision-making will contribute to sustainable development, however, it is difficult to achieve (Eggenberger and Partidário Citation2000). Respondents pointed out the importance of EIA integration and noted that in practice EIA is not fully integrated within decision-making and not sufficiently coordinated with multidisciplinary organisations as well as spatial planning process in Mongolia. Thus, EIA needs to be integrated into all levels of decision-making and territorial planning system. Moreover, respondents believe that new provisions and guidelines on addressing social impacts associated with NPLU are also required.

In developing countries, capacity building can offer an overall comprehensive solution to shortcomings of EIA and moreover, a precondition for an effective capacity building is improvement of institutional capacity (Khosravi et al. Citation2019). In fact, many respondents indicated that there is a need to enhance capacity building, increase accountability in practice improving enforcement of EIA laws and regulations as well as quality of EIA practice as it is perceived that stakeholders are not confident with the EIA process and capacity of EIA agencies and practitioners.

In summary, the overall responses to the Likert statements were poor when respondents were asked to evaluate EIA practice with respect to NPLU. Out of 70 statements, only 15 responses were positive and agreed that the EIA process has been effective in addressing impacts on NPLU. However, 55 statements were positive when respondents evaluated the legal framework for EIA with respect to NPLU. This indicates that EIA legislation includes necessary provisions for the issues of NPLU. Therefore, the implementation process of EIA in Mongolia should be improved.

5. Conclusions

We note that within 20 years since the 1998 introduction of the regulatory framework for EIA in Mongolia, it has succeeded in gaining acceptance and recognition. The EIA framework in Mongolia defines responsibilities and its scope of application to a sufficient extent and relies on a sound legislative and institutional set-up. To a certain extent, it considers alternatives, cumulative impacts, public participation and applies follow-up. However, in practice, the situation appears different. Mongolia’s EIA processes have not been appropriately conforming to its established provisions and procedures described in the regulations, nor have they sufficiently adopted the objective to protect pasturelands or to engage NPLU(rs) in the decision-making. In other words, the EIA process in Mongolia has not been effective for NPLU(rs) with regard to procedural and substantive dimensions of EIA. Moreover, it lacks stakeholder confidence and does not meet the expectations of stakeholders. Respondents were vastly critical of the EIA processes. In particular, those who are not directly involved in EIA such as academic and community respondents were more disapproving than government organisations and EIA consultants. Important improvements are needed in many areas of EIA to address the issues of NPLU better in future. The first priority should be improvement of impact prediction methods for dynamic land use and consideration of social and cultural impacts associated with NPLU in EIA.

Overall, our findings concur with those of Banhalmi-Zakar et al. (Citation2018) and Pope et al. (Citation2013) on the shortcomings of IA. We go however one step further by stating that in particular the needs and participatory opportunities for NPLU(rs) are far too limited, and perhaps even deliberately denied. We believe this constitutes an unwanted situation which needs to be redressed. We strongly believe that this situation also occurs in countries with similar characteristics and a similar significance of nomadic-pastoralists traditions. Hence, by highlighting the flaws of the current EIA system in Mongolia, it should not only provide an opportunity to improve the EIA process in Mongolia only but also stimulate other countries to follow this example and lead to EIAs which better address impacts on NPLU. Further research is therefore needed to address the EIA issues specific to dynamic land use in nomadic-pastoralism in multiple countries. These studies should investigate impact prediction methods suitable for NPLU and effects of EIA integration into spatial planning system on NPLU, and evaluate to which extent these problems and solutions are idiosyncratic and context-dependent or more structurally ingrained in EIA professional practices globally.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (321 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are immensely grateful to the survey respondents for taking the time to complete our questionnaire and share their professional experiences and insights with us. The authors also gratefully thank consultants of Sustainability East Asia LLC who provided in-depth insights and comments. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Allen VG, Batello C, Berretta EJ, Hodgson J, Kothmann M, Li X, McIvor J, Milne J, Morris C, Peeters A, et al. 2011. An international terminology for grazing lands and grazing animals. Grass Forage Sci. 66:2–28.

- Arts J, Runhaar HAC, Fischer TB, Jha-Thakur U, Laerhoven FV, Driessen PPJ, ONYANGO V. 2012. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance: reflecting on 25 years of EIA practice in the Netherlands and the UK. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 14:1250025.

- Baker DC, McLelland JN. 2003. Evaluating the effectiveness of British Columbia’s environmental assessment process for first nations’ participation in mining development. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23:581–603.

- Banhalmi-Zakar Z, Gronow C, Wilkinson L, Jenkins B, Pope J, Squires G, Witt K, Williams G, Womersley J. 2018. Evolution or revolution: where next for impact assessment? Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 36:506–515.

- Blench R. 2001. ‘You can’t go home again’: pastoralism in the New Millennium. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Howitt R. 2013. Framework for comparing and evaluating sustainability assessment practice. In: Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Howitt R, editors. Sustainability assessment pluralism, practice and progress. Oxon (UK): Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; p. 117–131.

- Bond A, Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A. 2015. Chapter 1: Introducing the roots, evolution and effectiveness of sustainability assessment. In: Morrison-Saunders A, Pope J, Bond A, editors. Handbook of sustainability assessment. Cheltenham: UK Edward Elgar;p. 3–19.

- Bryman A. 2006. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: how is it done? Qual Res. 6:97–113.

- Byambaa B, de Vries WT. 2019. The needs of nomadic-pastoral land users with respect to EIA theory, methods and effectiveness: what are they and does EIA address them? Environ Impact Assess Rev. 74:54–62.

- Cane I, Schleger A, Ali S, Kemp D, McIntyre N, McKenna P, Lechner A, Dalaibuyan B, Lahiri-Dutt K, Bulovic N. 2015. Responsible mining in Mongolia: enhancing positive engagement. Brisbane: Sustainable Minerals Institute.

- CAO. CAO assessment report, second complaint (Oyu Tolgoi-02) regarding the Oyu Tolgoi project (IFC #29007 and MIGA #7041). Office of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, International Finance Corporation/Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; 2013.

- Cashmore M, Gwilliam R, Morgan R, Cobb D, Bond A. 2004. The interminable issue of effectiveness: substantive purposes, outcomes and research challenges in the advancement of environmental impact assessment theory. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 22:295–310.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2013. Conceptualising the effectiveness of impact assessment processes. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:65–72.

- Doyle D, Sadler B. 1996. Environmental assessment in Canada: frameworks, procedures and attributes of effectiveness. Ottawa: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency.

- Eggenberger M, Partidário MR. 2000. Development of a framework to assist the integration of environmental, social and economic issues in spatial planning. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 18:201–207.

- Esteves AM, Franks D, Vanclay F. 2012. Social impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30:34–42.

- Fink A. 2017. How to conduct surveys: A step-by-step guide 6ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Gosavi A. 2015. Analyzing responses from likert surveys and risk-adjusted ranking: a data analytics perspective. Procedia Comput Sci. 61:24–31.

- Hanna K, Noble BF. 2015. Using a Delphi study to identify effectiveness criteria for environmental assessment. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 33:116–125.

- Jamieson S. 2004. Likert scales: how to (ab)use them. Med Educ. 38:1217–1218.

- Khosravi F, Jha-Thakur U, Fischer TB. 2019. Enhancing EIA systems in developing countries: A focus on capacity development in the case of Iran. Sci Total Environ. 670:425–432.

- Leung W, Noble B, Gunn J, Jaeger JAG. 2015. A review of uncertainty research in impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 50:116–123.

- Leung W, Noble BF, Jaeger JAG, Gunn JAE. 2016. Disparate perceptions about uncertainty consideration and disclosure practices in environmental assessment and opportunities for improvement. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 57:89–100.

- Likert R. 1932. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 140:5–55.

- Lkhagvadorj D, Hauck M, Dulamsuren C, Tsogtbaatar J. 2013. Pastoral nomadism in the forest-steppe of the Mongolian Altai under a changing economy and a warming climate. J Arid Environ. 88:82–89.

- Loomis JJ, Dziedzic M. 2018. Evaluating EIA systems’ effectiveness: A state of the art. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 68:29–37.

- McGahey D, Davies J, Hagelberg N, Ouedraogo R. 2014. Pastoralism and the green economy – a natural nexus? Nairobi: IUCN and UNEP; p. x + 58.

- MET. 2017. Protection, use and rehabilitation of natural resources. In: Nyamdavaa G, Shiirevdamba T, Enkhbat A, editors. Environmental Report of Mongolia, 2015–2016. Ulaanbaatar: Ministry of Environment and Tourism; p. 54–174.

- MET. 2019. EIA database of Mongolia. Ministry of Environment and Tourism of Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar.

- Morgan RK. 2012. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30:5–14.

- Morris P, Therivel R. 2009. Methods of environmental impact assessment. 3rd ed. Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis e-Library: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Noble BF. 2000. Strengthening EIA through adaptive management: a systems perspective. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 20:97–111.

- NSO. Gross domestic product (GDP) report, 2017. Ulaanbaatar: National Statistical Office of Mongolia; 2018. p. www.nso.mn.

- Nykvist B, Nilsson M. 2009. Are impact assessment procedures actually promoting sustainable development? Institutional perspectives on barriers and opportunities found in the Swedish committee system. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29:15–24.

- O’Faircheallaigh C. 2010. Public participation and environmental impact assessment: purposes, implications, and lessons for public policy making. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30:19–27.

- Pohjola MV, Tuomisto JT. 2011. Openness in participation, assessment, and policy making upon issues of environment and environmental health: a review of literature and recent project results. Environ Health. 10:58.

- Pope J, Bond A, Cameron C, Retief F, Morrison-Saunders A. 2018. Are current effectiveness criteria fit for purpose? Using a controversial strategic assessment as a test case. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 70:34–44.

- Pope J, Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F. 2013. Advancing the theory and practice of impact assessment: setting the research agenda. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 41:1–9.

- Reid RS, Fernández-Giménez ME, Galvin KA. 2014. Dynamics and resilience of rangelands and pastoral peoples around the globe. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 39:217–242.

- Rozema JG, Bond AJ. 2015. Framing effectiveness in impact assessment: discourse accommodation in controversial infrastructure development. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 50:66–73.

- Sadler B. 1996. Environmental assessment in a changing world: evaluating practice to improve performance hull. Quebec: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency & International Association for Impact Assessment.

- SGH. 2012a. Law of Mongolia on environmental impact assessment. Ulaanbaatar:The State Great Hural (Parliament) of Mongolia.

- SGH. 2012b. Environmental protection law of Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar:The State Great Hural (Parliament) of Mongolia.

- Sullivan GM, Artino AR Jr. 2013. Analyzing and interpreting data from likert-type scales. J Grad Med Educ. 5:541–542.

- Tenney A, Kværner J, Gjerstad KI. 2006. Uncertainty in environmental impact assessment predictions: the need for better communication and more transparency. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 24:45–56.

- UN. 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: UN Publishing.

- Wallington T, Bina O, Thissen W. 2007. Theorising strategic environmental assessment: fresh perspectives and future challenges. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27:569–584.

- Wood C. 2003. Environmental impact assessment: a comparative review. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Prentice Hall.

- Zhang J, Kørnøv L, Christensen P. 2013. Critical factors for EIA implementation: literature review and research options. J Environ Manage. 114:148–157.