ABSTRACT

Economic impact assessment (EcIA) has attracted some criticism due to its limited focus. Typically, EcIA is used to validate the proposed proposals based on growth in income and employment. This paper argues that EcIA should play a more active and stronger role in impact assessment. For example, the impacts of the proposed projects should be assessed using the economic development goals rather than only changes in economic growth. The conceptual framework for the comprehensive impact assessment is discussed. Examples of indicators that can be used in relation to sustainable development goals are provided.

Introduction

Typically, the objectives of a country’s development are set to increase its economic welfare measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or Gross National Product. Other macro-objectives include stable prices, full employment, equitable distribution of income, with quality of life and sustainable development goals (SDGs) becoming increasingly important objectives of economic development (World Bank Citation1991). Economic development is a broader concept than the concept of economic growth and includes an improvement in economic, political, environmental and social well-being. Economic development indicators include quantitative and qualitative indicators such as indicators of economic growth and improvements in life expectancy rates, infant mortality rates, literacy rates, poverty rates and mortality rates. Economic growth is a part of economic development. Economic growth is typically assessed using quantitative indicators such as per capita income and GDP (EDUCBA Citation2019).

Economic impact assessment (EcIA) is an integral part of the approval process for the major projects. It plays an important role in the decision of whether the project should proceed. Typically, EcIA is used to weigh up all positive and negative social, environmental and other impacts of the project to decide whether the project should go ahead (DSD Citation2017).

However, commonly, EcIA is based on the presumption that any increase in income and employment is beneficial for the economy. It generally fails to account for other dimensions of economic development such as quality of life, sustainability or an alternative use of resources. The issue with this approach is that not all developments even with the positive economic impacts such as increased employment or income result in a sustainable development. While income is an important indicator for the economy, it can come from a variety of projects.

Less than an acceptable use of EcIA is well documented (Ivanova et al. Citation2007; Rolfe et al. Citation2007; Lockie et al. Citation2009; Williams Citation2016). The main issues are that EcIAs provided inappropriate aggregation, misused of multipliers, ignored the costs borne by local community, ignored opportunity cost, ignored displacement costs. For example, Williams (Citation2016) suggested that since most EcIAs were performed at the state or national level showing the positive income and employment, the economic issues at regional level such as dampening housing prices, increase reliance on one industry and decreasing liveability in the region were often neglected. Furthermore, Crompton (Citation2006) argued that EcIA is used to legitimize a political position rather than provide an independent economic assessment.

The results of a prolonged poor EcIA practice might result in an increased economic inequality between the regions, increased unemployment, poverty and stagnation in the regions, costs to government in welfare payments, loss of revenue and reduction of project viability (Mathur Citation2008; Mishra and Pujari Citation2008; Ivanova Citation2014). The paradigm shift is needed in order for the EcIA to become a useful tool to achieve economic development and contribute to SDGs.

The rest of the paper is focused on how to make EcIA relevant and useful for decision-making to enhance the economic development. Section 2 discusses the general economic framework that can be used for the EcIA. Section 3 suggests some economic indicators that can be used to show whether the project assists to achieve the SDGs or hinders this progress. Section 4 provides conclusion and discussion.

EcIA framework

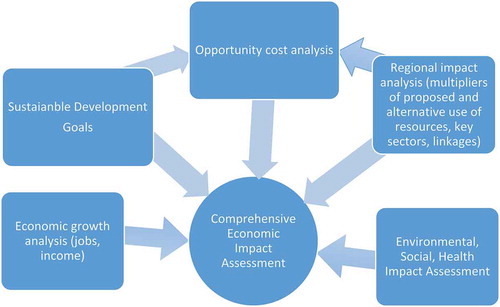

EcIA should assist in establishing full facts about the development to support a well-informed decision about the appropriateness of the development proposal, minimise adverse impact and maximise beneficial impacts, consider alternatives, to inform the planning and development assessment process (DSD Citation2017). Williams (Citation2019) suggested a comprehensive EcIA framework that can be used to include the relevant types of impact assessment (IA) and be adjusted for the risks. It does not, however, include the SDGs, which are an important part of the overall development. places EcIA and sustainable development in a conceptual framework. A broader IA literature’s suggestions on how to apply sustainability assessment models in IA can be used to improve the process (e.g. Pope et al. Citation2005; Bond et al. Citation2012; Sala et al. Citation2015; Villeneuve et al. Citation2017). Integrated assessment modelling can further assist in incorporating environmental considerations into the overall IA process (Hamilton et al. Citation2015), while territorial IA can provide a focus on specific regions (Fischer et al. Citation2015).

In the proposed framework, EcIA analyses the economic development rather than economic growth. Economic growth analysis becomes a part of a comprehensive EcIA. EcIA considers SDGs and identifies the ways the proposed project helps to achieve some goals and hinders the progress of other relevant goals. Analysis of the opportunity cost is an essential part of economic analysis. The opportunity cost analysis relates to the SDGs and regional impact analysis where the effects of alternative investments are considered. Regional impact analysis also feeds in the EcIA by providing an information about the structure of the economy, the impact of the industry and proposed project and suggestions on how to make the positive impacts stronger by analysing the linkages among industries and the project operations. In addition to the multipliers for the proposed project, an extended economic modelling should be performed. For example, multipliers from the project should be compared to average multipliers in the state or country. It allows to estimate whether the proposed project generates above-average number of jobs, income and value-added compared to alternative projects or investments.

Comprehensive EcIA needs to have an information from other types of IA in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the proposed project’s impacts. Typically, various IAs are conducted separately (Ivanova et al. Citation2007). The lack of integration among different types of IA limits the usefulness of these assessments. For example, environmental and social IA often qualitatively describe potential impacts. EcIA could assist to quantify some typically qualitatively described impacts by using market and non-market valuation techniques (Ivanova and Rolfe Citation2011; Rolfe et al. Citation2006; Rolfe and Ivanova Citation2007; Rolfe et al. Citation2009; Mallawaarachchi et al. Citation2001). For example, impacts on employment, income and housing affordability can be evaluated using social and economic tools. Environmental economics has a long history of the application of economic tools to environmental issues and, if correctly applied, can assist in estimating environmental losses (Crookesm and Martin de Wit Citation2002).

EcIA can be used where choices have to be made regarding different options (e.g. development options, budget allocation, trade-off between various costs and benefits). Thus, the integrated IA can provide guidance to project proponents and policymakers with regard to the community’s preferred options. However, caution is needed on how to integrate various types of IAs due to possible overriding environmental costs by perceived narrow socio-economic benefits (Morrison-Saunders and Fischer Citation2006).

The following section provides links between EcIA and some SDGs and suggests some indicators that can be used to connect the project’s impacts and SDGs.

Some SDGs and EcIA

UN (Citation2015) developed 17Footnote1 SDGs. The role of EcIA practitioner will be to assess the impacts of the proposed project against the most relevant SDGs. EcIA should be focused not only on those goals that the project helps to achieve but also an assessment of the negative impact on SDGs from the proposed project should be reported. Qualitative and quantitative analysis can be used.

For example, some goals, such as Goal 10 (Reduce inequality within and among countries), can be assessed using standard economic tools such as per capita income by age, gender and region. Even in developed countries, the proposed projects might contribute to increased poverty (Watkins Citation1982; Markey et al. Citation2005; Rolfe et al. Citation2007; Ivanova Citation2014). Regions dependant on the resource industry, for example, tend to be less diversified and, therefore, more vulnerable to the ups and downs of the business cycle. During the economic downturn, the resource-dependent regions might have stronger negative consequences than other regions. Ivanova (Citation2014) showed that while the average annual personal income in resource-rich regions is above the state average, the education is lower than the state average and the population in the most disadvantaged quintile is higher in some mining regions. Williams and Nikijuluw (Citation2019) analysed selected socio-economic indicators between coal mining and non-mining local government areas (LGAs) in Queensland, Australia. They found that, while coal LGAs tend to have a relatively lower unemployment and higher income trend over 10 years, there were a higher percentage of low-income households who were under financial stress from rent, and lower public services (such as total linear kilometres of council-managed road per capita and total capital expenditures on roads per capita).

Wellstead (Citation2007) summarised that dependence on one industry can lead to addiction to resource extraction even if it results in permanent underdevelopment and subsequent decline of the region’s economy. He suggested to promote new industries and employ the strategy of diversification in resource-dependent regions. Various indicators can be used including indicators that can help resource-dependent communities to benefit from extending their economic diversity, to increase their long-term sustainability and increase their capability of developing initiatives for local procurement (Esteves and Ivanova Citation2015). Furthermore, Ivanova (Citation2014) illustrated how the Input–Output analysis can be performed in order to improve the positive benefits of resource projects in the regions.

Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) should be evaluated with caution since an increase in employment and income does not necessarily mean a higher quality of life. For example, the mining project might increase local employment and income, but it could also contribute to pollution and results in higher healthcare spending for the region’s residents (Mehta Citation2002; Williams Citation2017, Citation2019). Quality jobs might also be questionable if DIDO/FIFO is involved due to a potential effect on mental health and wellbeing, family dis-functioning, and restrictions on children’s activities (Jacobs et al. Citation2014; CFCA Citation2014; Bowers et al. Citation2018).

The analyst should report the net rather than gross impacts, especially if the resources are re-directed from other industries. Focus on increased export from mineral resources should be replaced with the focus on overall net change in the economy. For example, positive net exports could mean an appreciation of the country’s currency. In turn, it could mean lower competitiveness of other export-focused industries such as agriculture, education or tourism. Those industries are more likely to be local, employing a local workforce and keeping profits in the region rather than sending them overseas.

Job opportunities for all residents should be considered. Particularly careful, the analyst should be with the so-called crowding out effect of higher wages in the resource sector. The effect on the local business needs to be examined. The following economic indicators can be used: number of FIFO/DIDO, impacts on the environment and its monetary equivalent, availability of local labour including unemployment rate, comparison of projects’ wages to the average in the region.

One of the postulates of Goal 8 is not to harm the environment. Therefore, careful consideration should be given to negative environmental impacts in the EcIA framework. While some impacts are hard to quantify and estimate the monetary equivalent, the past precedents or international estimates can be used for indicative values.

The potential impacts of the projects on Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) need to be assessed carefully. For example, mining is well known for water usage and water pollution (Ali et al. Citation2017). The alternative water users should be considered in order to avoid the potential issue of water scarcity. The following economic indicators can be used: water usage by proponent, water availability and competing usage, industry average water pollution indicators.

Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) allows the analyst to compare the alternative options such as renewable energy projects vs fossil fuel projects.

The following economic indicators can be used: cost of producing energy using alternative investment compared to project’s cost, emissions from the proposed project and its monetary equivalent.

Goal 9 (Industries, Innovation and Infrastructure) is focusing on investment in infrastructure. The proposed projects need to be assessed to which extent they contribute to this goal. For example, the analyst can check whether the proposed project uses the up-to-date equipment with lower carbon dioxide emissions and whether there is an investment in infrastructure that can be beneficial for the regions not only for the project’s proponent.

The following economic indicators can be used: productivity of the project compared to the industry’s best available, total kilometres of road built by the proponent accessible by non-project road participants.

Goal 13 (Climate Action) deserves a special attention when fossil fuel-related projects are proposed. The cost of carbon (equivalent) needs to be included in the IA statement to assist in moving toward a low-carbon economy.

The following economic indicators can be used: climate change-related emissions and its monetary equivalent.

Goal 15 (Life on Land) can be directly affected by resource projects through the loss of biodiversity and deforestation. The environmental impacts need to be quantified and where possible monetise to obtain the picture of full negative economic impacts of the project. The following economic indicators can be used: hectare of deforestation and loss of biodiversity and their monetary equivalent.

Goal 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) requires a common effort in order to achieve sustainable development. In IA, it means that communities, governments, IA practitioners and projects proponents should strive to work together to initiate investments in projects that deliver on sustainable development objectives, select the projects with least opportunity cost and enhance positive, while minimising negative, impacts of such projects. To achieve this goal, the IA practitioners need to work together from the start of the project, collect common data at the earlier stage and to inform the EcIA analysts of relevant environmental and social impacts, so they can be included in the comprehensive EcIA framework.

Summary and discussion

It is an opportunity for the IA to address the biggest challenges of the twenty-first century. The obsession with GDP and exports is masking the main question – where the country is heading in the future in relation to sustainable development. The same or higher growth in GDP/exports from different projects (such as ecotourism, cleaner energy, energy consumption reduction) might help to achieve development goals.

The following adjustment to the EcIA is needed in order for the EcIA to lead to achieve SDGs rather than growth:

Development goals should be set at the country level, with only projects that help to achieve those goals to be considered and assessed.

Use non-market valuation to inform the comprehensive EcIA.

Regional industrial structures/interconnections need to be considered to maximise the projects positive benefits.

Improve general education regarding the economic growth and development to understand the bigger picture.

What can be done in the absence of overall sustainable development strategy at a country or state level? IA practitioners should engage with each other early in the IA process. IA practitioners, community, government and project proponents can request for a comprehensive EcIA. EcIA practitioners can provide more analysis rather than simple multipliers including key industries analysis and net economic benefits to the society (i.e. country). The factors such as effects on other industries, level of skills in the long run, interdependence of industries in the region of interest, presence of dominant industry, potential for social and environmental damages, baseline for sustainable local economic development need to be factored in the EcIA. EcIA practitioners should be able to show how the project does or does not help the region/country to achieve SDGs using various economic indicators. These adjustments should not necessarily increase the cost of IA. However, additional non-market valuation can raise the cost of the EcIA. Although, in some cases, when the integration with other IAs is successful, the overall cost of IA might not change or can even be reduced.

Overall, EcIA can be improved by increasing awareness of the need for the comprehensive EcIA, increase legislative requirements for the EcIA, increase research in EcIA and enhancing skills of EcIA practitioners.

Notes

1. Goal 1: No Poverty, Goal 2: Zero Hunger, Goal 3: Good Health and Well-Being, Goal 4: Quality Education, Goal 5: Gender Equality, Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities, Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities, Goal 12: Responsible Production and Consumption, Goal 13: Climate Action, Coal 14: Life Below Water, Goal 15: Life on Land, Goal 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals (UN Citation2015).

References

- Ali A, Strezov V, Davies P, Wright I. 2017. environmental impact of coal mining and coal seam gas production on surface water quality in the Sydney basin, Australia. Environ Monit Assess. 189(8):408.

- Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Pope J. 2012. Sustainability assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(1):53–62.

- Bowers J, Lo J, Miller P, Mawren D, Jones B. 2018. Psychological distress in remote mining and construction workers in Australia. Med J Aust. 208(9):391–397. https://www.mja.com.au/system/files/issues/208_09/10.5694mja17.00950.pdf

- CFCA. 2014. Fly-in fly-out workforce practices in Australia: the effects on children and family relationships, child family community Australia, Australian institute of family studies. Victoria (Australia): Southbank. https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/fly-fly-out-workforce-practices-australia-effects/effects-having-fifodido-parent

- Crompton JL. 2006. Economic impact studies: instruments for political shenanigans? J Travel Res. 45(1):67–82. doi:10.1177/0047287506288870.

- Crookesm D, Martin de Wit M. 2002. Environmental economic valuation and its application in environmental assessment: an evaluation of the status quo with reference to South Africa. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 20(2):127–134.

- DSD. 2017. Economic impact assessment guideline, State of Queensland, department of state development.

- EDUCBA. 2019. Economic growth vs Economic Development. [accessed 2019 Oct 23]. https://www.educba.com/economic-growth-vs-economic-development/,

- Esteves A, Ivanova G. 2015. Using social and economic impact assessment to guide local supplier development initiatives. In: Karlsson C, Anderson M, Norman T, Elgar E, editors. Handbook of research methods and applications in economic geography. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA; p. 26.

- Fischer TB, Sykes O, Gore T, Marot N, Golobič M, Pinho P, Waterhout B, Perdicoulis A. 2015. Territorial impact assessment of European draft directives – the emergence of a new policy assessment instrument. Eur Plann Stud. 23(3):433–451.

- Hamilton SH, ElSawah S, Guillaume JHA, Jakeman AJ, Pierce SA. 2015. Integrated assessment and modelling: overview and synthesis of salient dimensions. Environ Modell Software. 64:215–229.

- Ivanova G. 2014. The mining industry in Queensland, Australia: some regional development issues. Resour Policy. 39:101–114.

- Ivanova G, Rolfe J. 2011. Assessing development options in mining communities using stated preference techniques. Resour Policy. 36:255–264.

- Ivanova G, Rolfe J, Lockie S, Timmer V. 2007. Assessing social and economic impacts associated with changes in the coal mining industry in the Bowen Basin, Queensland, Australia. Manage Environ Qual. 18(2):211–228.

- Jacobs G, Saffioti R, Freeman J, Johnson R, Cowper M, Bates M, Govus D, Roberts L. 2014. Shining a light on FIFO mental health, a discussion paper, report N4, education and health standing committee, legislative assembly. Perth: Parliament of Western Australia. http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/parliament/commit.nsf/(Report+Lookup+by+Com+ID)/AD292116C942943E48257D9D0009C9E6/$file/Discussion+Paper+Final+PDF.pdf

- Lockie S, Franettovich M, Petkova-Timmer V, Rolfe J, Ivanova G. 2009. Coal mining and the resource community cycle: a longitudinal assessment of the social impacts of the Coppabella coal mine. Environ IA Rev. 29:330–339.

- Mallawaarachchi T, Blamey R, Morrison M, Johnson A, Bennett J. 2001. Community values for environmental protection in a cane farming catchment in Northern Australia: a choice modelling study. J Environ Manage. 62:301–316.

- Markey S, Pierce J, Vodden K, Roseland M. 2005. Second growth: community economic development in rural British Columbia. Canada: Vancouver.

- Mathur H. 2008. Mining coal, undermining people: compensation policy and practice of coal India. In: Cernea M, Mathur M, editors. Can compensation prevent impoverishment?: reforming resettlement through investments and benefit sharing. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; p.260–285.

- Mehta. 2002. The Indian mining sector: effects on the environment and FDI inflows. [accessed 2019 Oct 23]. https://www.oecd.org/env/1830307.pdf

- Mishra PP, Pujari AK. 2008. Impact of mining on agricultural productivity: a case study of the indian state of Orissa. South Asia Economic J. 9(2):337–350.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Fischer TB. 2006. What is wrong with EIA and SEA anyway? – a sceptic’s perspective on sustainability assessment. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 8(1):19–39.

- Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A, Annandale D. 2005. Applying sustainability assessment models. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 23(4):293–302. doi:10.3152/147154605781765436.

- Rolfe J, Ivanova G. 2007. Community choices among options for the development of the Moranbah Township. Impacts of the Coal Mining Expansion on Moranbah and Associated Community Research Reports. Rockhampton: Central Queensland University.

- Rolfe J, Ivanova G, Lockie S, Timmer V. 2006. Assessing social and economic impacts associated with changes in the coal mining industry in the Bowen basin on the township of Blackwater. Socio-EcIA and Community Engagement to Reduce Conflict Over Mine Operations Research Reports. Rockhampton: Central Queensland University. Research Report 7.

- Rolfe J, Ivanova G, Yabsley B. 2009. Housing and labour market issues: survey of Moranbah households. Assessing Housing and Labour Market Impact of Mining Developments in the Bowen Basin Communities - ACARP C16027. Rockhampton: Central Queensland University. Research Report N 8.

- Rolfe J, Miles R, Lockie S, Ivanova G. 2007. Lessons from the social and economic impacts of the mining boom in the Bowen basin 2004 – 2006. Australas J Reg Stud. 13(2):134–153.

- Sala S, Ciuffo B, Nijkamp P. 2015. A systemic framework for sustainability assessment. Ecol Econ. 119:314–325.

- UN. 2015. Sustainable development goals. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Villeneuve C, Tremblay D, Riffon O, Lanmafankpotin G, Bouchard S. 2017. A systemic tool and process for sustainability assessment. Sustainability. 9(1909):2–29.

- Watkins M. 1982. The Innis tradition in Canadian political economy. Can J Political Sci Soc Theory. 6(1–2):12–34.

- Wellstead A. 2007. The post staples economy and the post staples state in historical perspective. Can Political Sci Rev. 1(1):8–25.

- Williams G. 2016. Advances and key challenges in EcIA. International Association for IA, IAIA16; Japan: IAIA.

- Williams G. 2017. Comparison of social costs of underground and open-cast coal mining. IAIA17 Conference Proceedings, IA’s Contribution in Addressing Climate Change; Montreal, Canada: IAIA.

- Williams G. 2019. A comprehensive EcIA framework: a proof of concept using open cut and underground coal mining in India. Environmental IA Review submitted.

- Williams G, Nikijuluw R. 2019. Economic and social indicators between coal mining LGAs versus non-coal mining LGAs in regional Queensland. Resources Policy submitted.

- World Bank. 1991. World development report 1991: the challenge of development. Wachington D. C.: World Bank.