ABSTRACT

In impact assessment (IA) the value of different forms of knowledge is increasingly acknowledged, but implementation and practice challenges continue. In Nunavut, a territory in the Canadian Arctic, Indigenous knowledge plays a key role in understanding and defining environmental baselines and guiding the assessment process; however, even here there are needs and opportunities for improved treatment and use of Indigenous knowledge in assessment and decision-making. This paper outlines the central role of Inuit Qaujimaningit/Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) (Inuit knowledge) in shaping and defining Nunavut’s impact assessment process. The work highlights the potential of the Nunavut process to provide a model for the use of Indigenous knowledge in IA, and of co-management or Indigenous-led impact assessment. Focus groups were held with board members and staff of the Nunavut Impact Review Board – the co-management board responsible for impact assessment in the territory. The results highlight the unique qualities of the impact assessment process in Nunavut and demonstrate how IQ is a crucial component of project review, notably its role in decision-making and for ensuring that the process is meaningful to communities. The results and recommendations have value to a range of other jurisdictions that are also working towards using Indigenous knowledge in environmental decision-making or even seeking to advance Indigenous-led impact assessment.

ᐊᑐᕐᑕᐅᑎᒋᓂᖏᑦᐃᓄᐃᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᑐᖃᖏᑦᓄᓇᕘᒥᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᐅᑎᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦᐊᐅᓚᓂᖓᓄᑦ

ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᐅᔪᑦ

ᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᐅᑎᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ (IA) ᐊᑐᑎᖃᕐᓂᖏᑦᐊᔾᔨᒌᖏᑦᑐᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᐅᔪᑦᐃᓕᓴᕆᔭᐅᕙᓪᓕᐊᒃᒪᑕ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂᐊᑐᓕᕐᑎᑕᐅᓇᓱᒃᓂᖏᑦᐊᒻᒪᓗᑲᔪᓯᑎᑕᐅᓇᓱᖕᓂᖏᑦᐊᔪᕐᓇᕐᓂᖏᑦᓱᓕᐱᑕᖃᕐᑐᖅ.ᓄᓇᕘᒥ, ᓄᓇᑖᕈᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅᑲᓇᑕᒥᐅᑭᐅᕐᑕᕐᑐᖓᓂ, ᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᑐᖃᖏᑦᐊᑐᕐᑕᐅᓪᒪᕆᖕᒪᑕᑐᑭᓯᐅᒪᔭᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦᐊᒻᒪᓗᑐᑭᖃᕐᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᓂᕐᒧᑦᐱᒋᐊᕐᕕᐅᔪᓐᓇᕐᑐᑦᐊᒻᒪᓗᐊᑐᐊᒐᐅᓪᓗᑎᒃᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦᐊᐅᓚᓂᖓᓄᑦ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂᑕᕙᓂᐱᑕᖃᕐᒪᑦᐱᕕᖃᕐᖢᓂᓗᐱᐅᓯᒋᐊᕈᓐᓇᕐᒪᑕᐊᑐᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᑦᐊᒻᒪᓗᐊᑐᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᑦᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᑐᖃᖏᑦᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦᐋᕿᒃᓱᐃᓂᕐᒧᓪᓗ. ᑕᓐᓇᑎᑎᕋᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦᐅᖃᕐᓯᒪᔪᖅᐊᑐᕐᑕᐅᑎᒋᓂᖏᑦᐃᓄᐃᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᓂᖏᑦ/ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᑐᖃᖏᑦ (IQ) (ᐃᓄᐃᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᖏᑦ) ᐋᕿᒃᓲᑕᐅᓪᓗᑎᒃᐊᒻᒪᓗᑐᑭᓯᓇᕐᓯᑎᑕᐅᓂᖏᑦᓄᓇᕘᒥᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᐅᑎᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦᐊᐅᓚᓂᖓᓄᑦ. ᐱᓕᕆᐊᒃᓴᐅᔪᑦᓇᓗᓇᐃᓯᒪᔪᑦᐱᑕᖃᕈᓐᓇᕐᓂᖓᓂᒃᓄᓇᕘᒥᐊᐅᓚᓂᖓᓂᐆᕐᑐᑕᐅᔪᓐᓇᕐᑐᒥᒃᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᑐᖃᖏᓐᓂᒃᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᐅᑎᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗᐃᑲᔪᕐᑎᒌᒃᓗᑎᒃᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᖃᑎᒌᒃᓗᑎᒃᐅᕙᓘᓐᓂᑦᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᕐᓯᒪᔪᓄᑦᓯᕗᓕᕐᑎᐅᓗᑎᒃᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᐅᑎᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ. ᑲᑎᒪᔨᐅᔪᑦᑕᑯᒋᐊᕐᑎᐅᔪᑦᑲᑎᒪᖃᑕᐅᓚᐅᕐᑐᑦᑲᑎᒪᔨᖏᓐᓂᒃᐊᒻᒪᓗᐃᖃᓇᐃᔭᕐᑎᖏᓐᓂᒃᓄᓇᕘᒥᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᓂᕐᒧᑦᑲᑎᒪᖏᓐᓄᑦ– ᐃᑲᔪᕐᑎᒌᒃᓗᑎᒃᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᖃᑎᒌᖕᓂᖅᐱᔭᑦᓴᕆᒐᔭᕐᑕᖏᓐᓂᒃᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᐅᑎᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦᓄᓇᕘᒥ. ᐅᖃᐅᓯᐅᓚᐅᕐᑐᑦᓇᓗᓇᐃᕐᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦᐊᔾᔨᐅᖏᑦᑐᒥᒃᐱᐅᓂᖃᕐᓂᖓᓂᒃᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᐅᑎᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦᐊᐅᓚᓂᖓᓄᑦᓄᓇᕘᒥᐊᒻᒪᓗᖃᐅᔨᒪᔾᔪᑕᐅᓗᓂᖃᓄᖅᐃᓄᐃᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᑐᖃᖏᑦᐱᓪᓚᕆᐅᑎᒋᓐᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᓗᓂᕿᒥᕈᔭᐅᓕᕐᐸᑕᓴᓇᔪᒪᔪᑦ, ᐱᓗᐊᕐᑐᒥᒃᐱᓕᕆᐊᒃᓴᕆᒐᔭᕐᑕᖏᑦᐋᕿᒃᓱᐃᓂᕐᒧᑦᐊᒻᒪᓗᐊᐅᓚᓂᖏᑦᑐᑭᖃᑦᑎᐊᕐᓗᑎᒃᓄᓇᓕᖕᓄᑦ. ᐅᖃᐅᓯᐅᓚᐅᕐᑐᑦᐊᒻᒪᓗᐊᑐᓕᖁᔭᐅᔪᑦᐊᑐᑎᖃᕐᑐᑦᐊᓯᖏᓐᓄᑦᓄᓇᖃᕐᑐᓄᑦᑲᓇᑕᒥᐋᕿᒃᓱᐃᓇᓱᒃᑐᓄᑦᐊᑐᕐᑕᐅᓗᑎᒃᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦᖃᐅᔨᒪᓂᖏᑦᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᓂᕐᒧᑦᐋᕿᒃᓱᐃᓂᕐᒧᑦ, ᐅᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦᐊᑐᓕᕐᑎᑕᐅᓇᓱᒃᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᕐᓯᒪᔪᓄᑦᐊᐅᓚᑕᐅᔪᒥᒃᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᐅᑎᔪᑦᒃᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᑕᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ.

Introduction

The value and importance of involving different resource-users and their distinct ways of knowing in natural resource management and environmental decision-making are widely recognized (e.g. Stevenson Citation1996; Usher Citation2000; Menzies Citation2006; Berkes Citation2012; UN General Assembly Citation2017). Resource-users and others who depend on the local environment can have a holistic understanding of the environment and often actively recognize ecosystem change and associated impacts on people (Huntington Citation2000; Berkes Citation2012). Such knowledge reflects an intimate relationship with an understanding of place founded on centuries of information that is passed down through generations. In Impact Assessment (IA), overlooking such knowledge can result in inadequate baseline data, challenges in linking ecological and social change to project actions, as well as a lack of local trust and confidence in the decision-making process (Sallenave Citation1994; Dowsley Citation2009).

Impact Assessment is the term used in Nunavut’s process and in Canada’s federal assessment legislation. The term can be applied interchangeably with environmental assessment (EA) and environmental impact assessment (EIA), which are commonly used in other jurisdictions. IA is important in the Canadian Arctic. It is used for project reviews to identify, assess, and mitigate the potential impacts of resource development and other activities, and to help plan and decide if and how development should proceed (Noble and Hanna Citation2015). IA also provides a key setting, and tool, for community consultation about natural resource development.

In the Canadian Arctic gaps in scientific baseline data pose challenges to IA practice (Nunami Stantec Limited Citation2018; Arnold et al. Citation2019). IA processes often employ adaptive approaches to inform baselines and rely heavily on the inclusion of local and Indigenous knowledge (Gondor Citation2016). Providing it is used early in the assessment process, such knowledge can also guide science by helping to focus on areas of enquiry – both thematically and geographically. Indigenous and local knowledge has shown to add considerable value to baseline assessments and monitoring in IA, but their use beyond ‘data collection’ can be limited (Usher Citation2000; Simpson Citation2004; Ellis Citation2005; Gondor Citation2016). For example, there can be a persistent lack of effective use of IQ for significance determinations. Despite the long-recognized advantages of incorporating diverse ways of knowing into IA, only recently have there been calls across the Arctic for improved treatment and use of different forms of knowledge in planning and decision-making. For instance, both the 2017 Pan-Territorial Environmental Assessment – Regulatory Board Forum and the 2018 Sustainable Development Working Group’s Canadian Arctic EIA Workshop – emphasize the important role Indigenous knowledge should have in IA (Stratos Citation2017; Onfoot Consulting Citation2018). Despite some progress in advancing different means of applying diverse ways of knowing in resource management (Huntington Citation2000; Usher Citation2000; Houde Citation2007; Croal and Tetreault, Citation2012), and better guidance for implementing such into IA (Mackenzie Valley Environmental Review Board Citation2005; Fedirechuk et al. Citation2008), it has been argued that Indigenous knowledge is often incorporated into resource management only when it fits well with the ‘western structures’ of such processes (Nadasdy Citation2003; Simpson Citation2004; Ellis Citation2005; White Citation2006).

In the Territory of Nunavut, Canada, IA is in many respects Indigenous-led. The territory can provide a model for approaches elsewhere in Canada and across other Arctic regions. Indigenous-led processes are characterized by Indigenous laws, norms, culture, and the important role of traditional knowledge guiding and shaping the process, and where the nation has decision-making authority (Gibson et al. Citation2018). Not all aspects of an Indigenous-led IA process would necessarily be entirely different from other existing IA models. Instead, an Indigenous approach might seek to adapt and mould selected qualities from ‘western’ IA and instil new qualities and approaches from Indigenous principles and governance norms.

Across Canada there are generally three types of partnerships in Indigenous-led IA: co-developed with the proponent, co-managed with the Crown, or independently organized and carried out by the Indigenous nation (Gibson et al. Citation2018). Across the Canadian Arctic, where co-management boards have key roles in decision-making, use diverse ways of knowing, and are supported by constitutionally protected land claims agreements with strong legislative frameworks, Indigenous involvement is arguably quite strong and effective. But in other locales independent Indigenous-led IA processes may need to be developed to ensure meaningful Indigenous participation and influence (Gibson et al. Citation2018).

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit/Qaujimaningit (IQ) (Inuit Knowledge) (see Box 1) is systematically used throughout Nunavut’s IA process and helps ensure that the process is inclusive and meaningful for communities (Barry et al. Citation2016). The Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB) is the institution of public government (IPG) responsible for IA for all project proposals in the Nunavut Settlement Area (NSA) and the outer land-fast ice zone, as established under the Nunavut Agreement (Government of Canada and Tungavik Federation of Nunavut Citation1993). When referring to IQ in the assessment process, the NIRB encompasses ‘local and community based knowledge, ecological knowledge (both traditional and contemporary), which is rooted in the daily life of Inuit people, and has an important contribution to make to an impact assessment’ (NIRB Citationn.d.b, par. 3). IQ should also be seen as evolving – it is not static. While the knowledge that elders hold is fundamental, IQ also transcends generations and will be transformed by Inuit youth in response to new environmental, social, and economic circumstances.

Box 1. Inuit Qaujimaningit and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit.

This article examines the role of IQ in Nunavut IA and the potential role of Nunavut’s IA process as a model for co-management partnership in Indigenous-led IA. Previous studies have outlined how IQ is a key element of adaptive capacity due do its dynamic nature and its ability to learn, evolve, and adapt to unprecedented and unpredicted change (Ford et al. Citation2006; Laidler et al. Citation2009; Pearce et al. Citation2015). In the Canadian Arctic, there is ongoing work to apply IQ to advance climate change adaptation and community resilience to environmental change. For instance, the Inuit Sea Ice Knowledge and Use (SIKU) Atlas was developed to collect, document, and share, through an app and web-based application, IQ and local knowledge of sea ice conditions and associated changes around Baffin Island, Nunavut (Krupnik et al. Citation2010; see sikuatlas.ca). Similarly, the SmartICE (Sea-ice Monitoring And Real-Time Information for Coastal Environments) program applies IQ to inform technological innovation and improve environmental monitoring and sea ice safety (Bell et al. Citation2014; see smartice.org). Both the SmartICE and SIKU projects highlight the value of IQ to climate change adaptation and environmental monitoring. The application of such tools can be used in IA to better inform environmental baselines and to monitor impacts and associated changes.

There has also been research on how IQ is used in IA in Nunavut – specifically project and process documents associated with the Meadowbank Gold Mine (Gondor Citation2016). Other studies have offered community perspectives regarding knowledge use in IA in Nunavut, notably related to the Kiggavik Uranium proposal (Metuzals and Hird Citation2018). While further research has outlined the roles of other IPGs, such as the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, in the co-production of knowledge and adaptive management (Wheatley Citation2001; Armitage et al. Citation2011), there are no works that have specifically explored the role of the NIRB and the institutional perspective on using IQ in the assessment.

Though this study examines one IA process, the recommendations have broader value for not only Arctic IA jurisdictions, but other global locales as they seek to advance the treatment of diverse ways of knowing into IA or work towards Indigenous-led IA approaches.

Study area

Inuit Nunangat is the geographical, political, and cultural region of the Inuit of Canada (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami Citation2018). Nunavut () is the largest of the four regions in Inuit Nunangat and the largest of all territories and provinces in Canada. It covers just over 20% of the country. It is vast, has a small population (<40,000) with the majority (84%) identifying as Inuit, and at just 0.02 people/km2 it has the lowest population density in the country (Statistics Canada Citation2017).

Recent economic growth in Nunavut is largely due to the mining industry, where annual gold production is projected to double by 2020 (Jamasmie Citation2018). As of 2018, there were 53 active exploration, development, and production projects across the territory including 44 gold projects, 4 diamond projects, 2 base metal projects, and 3 active mines (2 gold, 1 iron ore) (Senkow et al. Citation2018). Alongside mineral resource development, unexplored oil and gas reserves in the territory are estimated at a minimum of 18 billion barrels of oil and 180 trillion cubic feet of gas (Government of Nunavut Citation2017). As resource development expands, there is increasing pressure for increased environmental management and planning, and to account for the emerging and future impacts of climate change, which pose particular environmental and social challenges for Arctic regions.

The NIRB administers Nunavut’s IA process and coordinates related project reviews and decision-making with other co-management boards including the Nunavut Planning Commission and the Nunavut Water Board (Barry et al. Citation2016) (see Box 2). The impact review board is comprised of a chairperson and up to eight members. It reports to federal and/or territorial government ministers; as the majority of projects are undertaken on federal crown land in Nunavut, the federal Minister of Northern Affairs is most often responsible for authorising a project to proceed. The Government of Nunavut appoints two board members, and the Government of Canada appoints two. Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI), representing Inuit under the land claims agreement, nominates the remaining members, with input from the three regional Inuit Organizations. Once nominated they are formally appointed by the federal minister responsible for Northern Affairs (NIRB Citation2018a). Board positions are typically filled by Inuit community members (Gondor Citation2016). Barry et al. (Citation2016) highlight the uniqueness of the board when compared to other IA boards in Canada in that the board and its stakeholders are almost entirely Inuit. The NIRB emphasizes that ‘although [the board] relies upon Government and Inuit Organization partners for advice and for technical assistance, the members of the NIRB make their decisions on behalf of Nunavummiut (the people of Nunavut) and the rest of Canada, and not as agents of their appointing bodies’ (NIRB Citationn.d.a, par. 8). The NIRB staff interact with the public and assist with communications and administer finances, administration, and provide technical services (NIRB Citationn.d.c).

Box 2. Boards and Tribunals in Nunavut.

Compared to other Canadian jurisdictions, Nunavut’s IA process is young and evolving as political, economic, and environmental changes advance (Barry et al. Citation2016). The IA process was initially outlined in the Nunavut Agreement and ran parallel to the Canadian federal IA process, but amendments to the Agreement in 2008 removed any role of federal IA in Nunavut (Government of Canada & Indigenous and Northern Affairs Citation2012). The IA process is further outlined in the Nunavut Planning and Project Assessment Act (NuPPAA), which was first proposed in Article 12 of the Nunavut Agreement, signed in 2013, and came into force in 2015 (Government of Canada Citation2013).

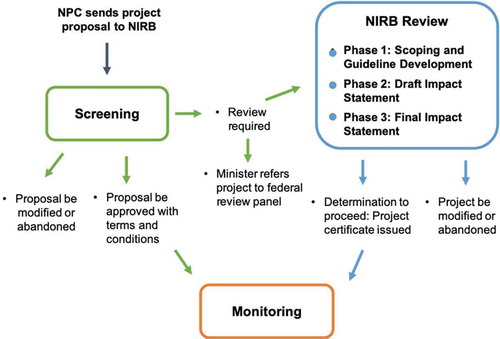

Nunavut’s assessment process has three basic steps: Screening, Review, and Monitoring (see ). The process begins following a land-use conformity review by the Nunavut Planning Commission (NPC). If screening is required, the project proposal is sent to the NIRB to assess whether the project will potentially result in significant environmental or social-economic impacts, and whether a more thorough review is necessary by either the NIRB or a federal panel for projects involving matters of national interest (Government of Canada Citation2013). The Review consists of three phases and is generally required for major projects or developments with significant impact potential, for developments with technological innovations where the effects are unknown, or where there is significant public concern for a proposed development. The Review consists of a more comprehensive assessment and requires the proponent to submit a detailed impact statement (IS) outlining information regarding the project description, project design, consultation practices, information baselines, potential impacts, mitigation, and management of the proposed project. Based on the IS, stakeholder input, and public/community consultation, the NIRB issues its report to the responsible government ministers, providing a determination regarding whether or not the project should proceed, and if so under what terms and conditions. If the project is approved, then the final step of the NIRB process is monitoring the project. The NIRB issues a Project Certificate (approval) with terms and conditions from the Review’s final report and any subsequent direction from the responsible ministers, then coordinates the monitoring program and ensures that all parties (proponent, regulators, organizations, and others) are participating as necessary. The monitoring program evaluates the impacts of the project; determines compliance with the terms and conditions; provides other agencies with the necessary information to undertake their monitoring responsibilities and assesses the accuracy of impact predictions described in the IS (Government of Canada Citation2013).

Nunavut has implemented what is arguably the most thorough public consultation process in Canadian IA. From early on, Nunavut has mandated the use of both IQ and scientific knowledge (Barry et al. Citation2016). There is no single consultation methodology per se. The consultation process is contextual and rooted in a culture of listening. It is based on being in communities – to hold meetings; present information and answer questions; and to listen to the concerns, questions, and knowledge that communities provide to proponents and the board. IQ informs the process at all stages. Proponents are required to consult and recognize IQ, and use it in the preparation of the IS, while the NIRB includes IQ through consultation and community engagement, and carries this through in the decision-making and monitoring processes (Barry et al. Citation2016). The board emphasizes that IQ should not solely be used to inform environmental baselines, but that the values of IQ should be applied throughout the process and ultimately guide the process (NIRB, n.d.-b). This is further reflected in the NIRB recent five-year strategic plan, which indicates that ‘[T]he NIRB will reflect the principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit/Qaujimaningit through its work’ (Nunavut Impact Review Board Citation2018a, p. 16).

Method

This research is qualitative – drawing first on a document analysis and then focus groups with the NIRB. A review of the literature (policy, regulations, and other supporting materiel) and operational project and assessment process documents provided an understanding of the regulatory setting in Nunavut and showed how IQ had informed project assessments and supporting project studies. The document review helped create and frame the focus group questions. The data and knowledge presented here were collected from the focus groups. The focus groups provide an understanding of the challenges associated with addressing information needs and an understanding of the role of IQ in the process and the guidance it provides for the deliberative aspects of the IA process and for decision-making. The approach helps illustrate how such knowledge informs and shapes the views of those who make the process work. The focus groups also provide insights into IQ and the assessment process, which may not be evident in documents or the formal policies that decision-makers use.

Two focus groups were conducted in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, in July 2018. One was with 10 NIRB staff, and the second was with the eight board members. We chose the focus group approach because it benefits from unique group interactions to provide insights and data often not possible through individual interviews (Morgan Citation1996). The method can be used to obtain diverse perspectives and beliefs on a central topic, and generate a rich understanding of unique and shared experiences (Patton Citation2002; Wascher Citation2013). The focus groups offered a lens into the organization, how it works and uses IQ, and provides collective or institutional views rather than individualized ones. The approach does not make individuals the focus, or subject, of the research. This was valuable as it provided collective insight to the NIRB through the reflections of board members and staff on their work, and the deliberative group discussions that also helped participants learn from each other (Jackson Citation2003), as they collectively responded to and discussed the questions. Following the focus groups, board members and staff commented on the value of the focus group discussions for the internal work of NIRB. This added further merit to the research.

Some focus group questions were common to both groups and some were unique to a group. Questions for the board members focused on experiences and challenges to IQ use, the changing role and treatment of IQ over time, and the role of IQ in eventual decision-making. The staff session focused how IQ is used in the IA process, and specific challenges and unique approaches to community engagement. The questions were open-ended and used to spur the discussion based on a theme but without restricting the direction or content of the discussion and responses. Meeting with the board and staff was essential to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the organization and its workings, and to appreciate how the board’s experience might help better address IA process challenges regarding the use of different types of knowledge. We focused on the use of IQ by the board in assessing projects, in its internal deliberations, and as a key factor used in decision-making. Participants were also able to comment on the roles of other agencies, different types of intervenors, and communities in the IA process. Engagement with such other parties would have aided the research, but logistical challenges (time, funding, and people's schedules) common to working in Inuit Nunangat, posed limitations for access to communities and travel across the region.

The focus groups were recorded with the permission of all participants, and the audio recordings imported and directly transcribed in NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd Citation2018). Notes were taken throughout the transcription and were reviewed prior to coding. The transcripts were analyzed through descriptive and analytic coding. Descriptive coding was used to organize and categorize the information, followed by analytic coding to identify emergent themes (Saldaña Citation2009; Richards and Morse Citation2013).

Results

The results provide an understanding of the NIRB, institutional perspectives on the role of IQ, and its use in the IA process. The key themes that emerged from the focus groups include; the use of IQ to guide and shape the process, particular challenges in IQ use in assessment, and the distinct (relative to other jurisdictions) qualities of the NIRB and the Nunavut IA process.

IQ to guide and shape the process – ‘we have more confidence in our predictions’

The importance of IQ to the NIRB and the IA process was emphasized throughout focus group discussions. The role of IQ to guide and shape the process is achieved using IQ as available knowledge in its own right; the incorporation of IQ knowledge and values; and the use and treatment of IQ and western science as complementary rather than contradictory.

Focus group participants emphasized that IQ is not simply used to fill the gaps in knowledge derived from science, but rather IQ is used as available knowledge regardless of the availability of western science. This was explained in the staff focus group:

“For baseline, I would almost go the other extreme and say that almost everything up here from a scientific basis is lacking a baseline, and that has led to the board often filling those, not even fair to say filling the gaps, but often having to rely more heavily, solely on, existing Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. So it is not that it is filling a gap because there are gaps in available scientific baseline data, but it’s not saying that there are gaps in available knowledge on those same things”.

Similarly, the idea of IQ as an ‘add-on’ to western science was described as not being the case; instead, IQ is: ‘Realistically I think there are some times where the knowledge that people are sharing, the IQ, is add-ons to what the agency is presenting as scientific knowledge, but (in practice) it is way more limited than you may normally think’ (staff focus group). Rather than being an ‘add on’, IQ is unique and distinctly appreciated knowledge, as indeed is science.

Participants also reported a trend towards a stronger role for IQ, where the knowledge is not being used to solely address gaps or to fulfill guideline requirements, but rather because it is both equally valued and it is the available knowledge. As was noted by the staff focus group:

“Through time there is a positive trend and it really stands out now when a proponent doesn’t get it … The expectations are well beyond just giving lip service to Traditional Knowledge, it is completed different to that these days”.

The role of IQ was said to extend beyond including IQ in IA documentation. Board members stated that communities would tell the NIRB whether the values of IQ are being incorporated into the project. The importance of engaging with community members throughout the entire process, rather than solely during data collection phases, was repeatedly highlighted: ‘Incorporating IQ shouldn’t be done just initially but has to be continually done throughout the project’ (staff focus group). However, limited or absent company presence in the communities was described as a limiting factor to the incorporation of IQ throughout a project’s operations.

The influence of IQ values during the review as well as on decision-making was described by both board and staff members. An example was offered of the Doris North project amendment, a proposal to use an underwater pipeline to discharge saline effluent into the marine environment at Roberts Bay. It was noted that the primary concern, and definitive request, of community members and board members was that the pipeline be removed at the decommissioning stage of the project, notwithstanding the proponent’s view that the environmental impacts of removing the pipeline would be greater than the impacts of leaving it in place. It was explained in the staff focus group ‘the thought of leaving it there long term was too disturbing for community members’. This resulted in the board developing terms and conditions requiring the removal of the pipeline and ecological restoration at Roberts Bay. The staff focus group noted that this underlined the role of cultural values in decision-making:

“So for the staff that was eye opening at the time because we are explaining objectively the merits of leaving it in long term and it is not an ecological issue … That really speaks to cultural values, it was not acceptable to leave it in long term once it was no longer needed”.

Further discussions with board and staff highlighted how IQ informs decision-making by providing greater context to a proponent’s impact predictions, and local perspectives on the adequacy of baseline information. The Kiggavik Uranium Mine Project review provides an example of this. It was explained in the board focus group that during a public engagement session the proponent outlined a dust distribution model predicting minimal dispersion from the proposed mining operations. The community responded to the proponent with many questions: ‘Have you been here in winter? Have you seen the winds? Do you have any idea of what the wind actually does here? Were those (weather) stations year-round? Were they measuring year-round?’ (board focus group). The board emphasized that ‘there was a clear incompatibility between what local people knew and what the proponent’s predictions were’, demonstrating the value and importance of local knowledge and engagement for providing context to improve project impact predictions. In the NIRB Final Hearing Report for the project, the board further highlighted the importance of IQ for any future proposal, with specific reference to the adequacy of baseline information: ‘The Board would like to highlight the importance of Inuit Qaujimaningit related to Marine Wildlife, as the Board believes that the potential impacts of the Project on the abundance and distribution of culturally valued species (e.g. beluga, seal, walrus, and polar bear) warrants further attention in any future project proposal’ (NIRB Citation2015, p.151). The Kiggavik project was ultimately recommended to not proceed due, in part, to concerns about inadequate baseline data (Nunavut Impact Review Board Citation2015).

For both focus groups, there was a mutual understanding regarding the value of IQ and the compatibility of the knowledge system with western science in the IA process. The use of IQ and western science in the IA process was repeatedly described as complementary rather than contradictory or necessarily separate. In the staff focus group, it was explained that ‘the information was actually not incompatible at all but in fact mutually reinforcing’. Board members shared similar thoughts regarding the connections and compatibility of IQ and western science, although they emphasized the need of both sides to work together to better respect and value each other’s knowledge. Staff members reiterated this point. They also brought up the ‘misconception’ regarding the use of IQ and IA often portrayed in the literature – that the actual challenge lies in having IQ and western science equally respected and valued in the process: ‘In EA and academia particularly there is often, and I think it is a misconception, that there is an inherent challenge in aligning traditional knowledge and scientific knowledge’.

The focus groups emphasized that when IQ and western science are equally respected, and valued, then its treatment within the process may be more meaningful. It was thoroughly highlighted that effective use of IQ early and throughout the process adds confidence and certainty to impact predictions and ultimately leads to a stronger assessment process: ‘we have more confidence in our predictions because we incorporated Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit earlier’ (staff focus group).

Challenges to IQ application – ‘IQ isn’t a dataset on a shelf’

Staff and board members discussed the challenges associated with IQ availability and accessibility, consultation fatigue, as well as a perceived unequal value between IQ and western science. The availability and accessibility of information are not an uncommon challenge to IA processes and was repeatedly discussed by the NIRB. However, the availability and accessibility of information informed by IQ for use in the IA process are met with unique challenges.

Board and staff members explained that there is often an assumption among certain stakeholders that there is available IQ that potentially has not yet been captured, but this is not always the case, ‘[they] have to be careful about assuming that there is available Inuit Qaujimaningit about issues that are not historic and issues that are very contemporary in nature’ (staff focus group). Therefore, alongside the challenge of collecting and capturing data, there is the challenge of understanding what information or data are potentially available to gather, notably when informed by IQ.

In Nunavut, and indeed other Arctic regions, a rapidly changing environment exacerbates baseline information challenges. The influence of environmental change on the IA process was described to be complex and widespread. The board focus group noted, ‘today is very different, we have gone through a very big change in a short time and it is hard for us to predict what might happen next year or so because there are so many things that are happening on our land’. The IA process is tasked with describing environmental baselines in an area of unprecedented environmental change. It was explained that data previously collected to describe baselines are often no longer accurate due to rapid environmental changes in the region. Likewise, the staff focus group described how rapidly changing environmental and climate conditions may result in uncertainties regarding information that was previously known to be true: ‘The fact that the conditions now are changing so fast, especially related to climate change and ice formation … We hear a lot from elders that they don’t know the current ice conditions anymore’. A challenge moving forward will inevitably be the ability of the IA process to cope with and adapt to greater uncertainty caused by environmental change, as well as the ability to identify and address unprecedented information needs. In this vein, IQ is neither static nor historic, but is a way of understanding and knowing the land and environment even as conditions change.

The accessibility of available IQ was identified as another challenge to the IA process. Although information may be gathered and made available for use, constraints related to accessibility can impede the usability of the information. The staff focus group commented, ‘I think the problem is that IQ has been documented but the accessibility for other people to use it is challenging’. It is often the case that the knowledge previously shared by community members is applied to the specific project review, then remains ‘scattered’ in the documents and public registry, inaccessible to other information-users. In certain cases, IQ is collected and stored in databases that are maintained by regional Inuit organizations, where the information is safeguarded, and accessibility might be limited. In order to access information proponents are often required to sign agreements with the organizations ensuring that ownership-rights are maintained and that the knowledge is used respectfully and not taken out of context. Although this may bound how readily accessible the information is, this protection is exceedingly important. Due to the highly contextual and dynamic aspects of IQ, the way that the knowledge is applied may vary between two situations or projects. This was described in the staff focus group,

“IQ isn’t a dataset on a shelf, it is inherently the application of that knowledge. That is why you might get two very different answers to a question; it’s because it is how it’s applied. Part of the value of asking a question for the 5th time is because maybe it was asked a decade ago offering to another type of mining, and now things have changed and they are applying the data very differently”.

It was further highlighted that when considering changing environmental and social-economic conditions in Nunavut, the application of IQ will also advance differently moving forward.

While the NIRB and other IPGs state that IQ is valued equally to western science, it was commented that there is often a challenge in getting proponents, consultants, and sometimes regulators to acknowledge this importance. In the staff focus group, it was commented that ‘more often than not [IQ and western science] agree and there is a challenge in having them both respected to the same degree and accounted for and listened to and generated and everything else’. It was explained that varying levels of respect and value could lead to community members being reluctant to share their knowledge in the IA process. Financial compensation was used as an example of the unequal value between IQ and western science, where the remuneration offered to consultants was compared to that offered to community knowledge-holders:

“You have a consultant come in who is getting paid on a very valuable contract and they are getting paid a lot of money and then you have an elder coming in getting paid 50 bucks [CDN 50 USD] an hour to share what they know, when it is their knowledge and experience that they are providing that is really going to provide a foundation to inform a project but they are not equally valued in terms of financial compensation” (board focus group).

There are also challenges related to knowledge-holders not always eager or able to share information due to consultation fatigue. As explained by staff, ‘IQ holders are getting tired of sharing the same information over and over’.

‘We are the model now’

The composition of the NIRB facilitates the meaningful integration of IQ and western science, where both knowledge systems are used to complement each other, as well as better ensures that IQ and local knowledge influence and guide decision-making. The distinctive components of the NIRB IA process facilitate meaningful community engagement as well as help to coordinate the process with other stakeholders contributing to a more effective IA process.

It bears emphasizing that meaningfully integrating or connecting IQ and western science requires equal respect and value. The unique make-up of the NIRB helps facilitate this integration. The board focus group highlighted this:

“As you can see we have our board of directors who are from the land and have a strong belief in our people and at the same time we have 17 of the best brilliant educated staff that have PhDs and legal knowledge. We use them because they have that other knowledge that we don’t have, and they also say the same thing to us, that they need our knowledge to be able to make an informed decision that is not only going to compliment what is in front of us but what will affect us in the long run and I think that continuously has to be evolved within our governments not just within IPGs like us. Ours, we’re perfect because we respect each other’s knowledge, and respect each other.”

The respect that board and staff have for each other was evident throughout the focus group meetings, and in indeed during the board proceedings, we observed firsthand. An advantage of the composition of the NIRB is the ability of the organization to better balance both western science and IQ. The staff focus group underlined ‘a challenge is that in western science it is easy to critique what science is saying … in most cases it is inappropriate for me to critique or question what an elder is saying. The board is able to weigh and question whereas for us (non-Inuit) it is inappropriate’. It was highlighted that a better understanding of the differences between knowledge systems and an equal respect and value between systems facilitates the meaningful integration of IQ in the process, notably in decision-making.

Two important components of the Nunavut IA process were highlighted during the focus groups regarding the uniqueness of the board and its ability to effectively engage with communities and actively participate and coordinate the regulatory review process. The first component is the inclusion of community roundtables. During the second phase of a NIRB review, the board facilitates a pre-hearing conference, which provides an opportunity for communities and other interests to discuss any outstanding concerns prior to the proponent’s submission of the Final IS. Community roundtables are undertaken at the pre-hearing conference and allow for an organized means of early and meaningful engagement between community members and the proponent. This component was repeatedly raised in the focus groups related to discussions on knowledge integration and community engagement. Staff members described the community roundtables as ‘flagging for proponents how this really has to be done’ and ‘testing the validity of a proponent’s assumptions’. This early engagement process ensures that proponents understand how IQ must be incorporated into the process beyond ‘checking boxes’. It can further be used to identify early concerns and information needs, as well as ensures that IQ is incorporated early in the process, which has been previously described as an important component towards more meaningful integration.

The second unique process component is the NIRB monitoring function. As highlighted in the staff focus group, ‘The unique part about the NIRB is that we do monitoring, we don’t leave the process at EA and walk away, we have an active feedback mechanism that we do monitoring, we are unique and very proud of it’. Other IA jurisdictions in Canada can have poor linkages between the IA process and the agencies ultimately responsible for carrying out project-specific monitoring and enforcing terms and conditions (Hanna Citation2016). The staff focus group explained, ‘It is [the NIRB] responsibility as part of [the NIRB] monitoring process to be more proactive’. This improved level of engagement in the process on the part of the NIRB is viewed as providing greater accountability and adding to the effectiveness of the IA process by better supporting compliance and developing an improved understanding of the validity of impact predictions, as well as better addressing community and stakeholder information needs through a coordinated monitoring process.

These attributes of the process coupled with the representation of Nunavummiut on the board and staff, speak to the NIRB potential to serve as a model of effective IA arrangements and processes for other jurisdictions.

“We are the model now though, the feds (Canada’s federal government) and others are looking at us as the example. There are days where it feels like we are so far behind and haven’t done enough to incorporate IQ and we are just not there, people are looking at us and going how have you come that far, and it is an enlightening moment. We still have a way to go but we are doing well” (staff focus group).

Discussion

The indispensable role of IQ

The results of this research demonstrate that IQ is an indispensable component of the NIRB and its IA process. Although integration challenges persist, IQ is used to inform baselines, identify environmental change and associated impacts, and ultimately guide decision-making and shape the IA process in Nunavut. The significant role of Indigenous knowledge and IQ in informing environmental baselines in IA is widely acknowledged (Nakashima Citation1990; Sallenave Citation1994; Gondor Citation2016). However, much criticism on the role of Indigenous knowledge in IA is based on the notion that the knowledge is solely used for informing baselines where data gaps exist, and only incorporated into IA when it fits well with the existing structures of such processes (Nadasdy Citation2003; Simpson Citation2004). The integration and documentation of certain aspects of IQ in ISs or other IA components are not always suitable due to the structure and organization of IA reporting and its focus on western science; however, other stages of the IA process are better positioned to incorporate different aspects of IQ such as values and cosmology (Usher Citation2000; Gondor Citation2016). This is reflected in the Nunavut context. The results of the focus groups emphasized the role of IQ values throughout the process, notably in decision-making, as well as highlighted the need to consider all aspects of IQ in the process to ensure meaningful integration.

During the focus groups, the NIRB acknowledged the academic literature highlighting the incompatibilities between Indigenous ways of knowing and western science, and the challenges to integration in a co-management setting (e.g. Nadasdy Citation2003; Simpson Citation2004; Ellis Citation2005; White Citation2006); however, it was described as a ‘misconception’ and instead emphasized the complementary nature of IQ and western science. Similarly, in the NIRB 2018–2022 Five-Year Strategic Plan, the board acknowledged the aforementioned critiques:

“ … the NIRB sometimes receives criticism for administering a very formal type process which is based on a southern model and not reflective of Inuit values. The NIRB can take steps to improve how the public views the board and the overall regulatory system through better communication of our successes, and increased accessibility on all fronts” (Nunavut Impact Review Board Citation2018a, p. 21).

This helps highlight an important disconnect between the views from those ‘on the ground’ and some of the scholarly literature. Through a better understanding of the unique composition of the NIRB board and staff, as well as of the unique components of the NIRB IA process, such as community roundtables and project monitoring, the results of this research further demonstrate how the role of IQ in IA extends beyond informing baselines, and how the NIRB IA process is guided by IQ.

With respect to understanding various aspects of environmental change, it has been demonstrated that IQ and western science provide complementary and reinforcing knowledge (Riedlinger and Berkes Citation2001; Laidler Citation2006). Similarly, recent literature has argued the need to move beyond comparing and contrasting local knowledge and IQ with western science, and work towards embracing their complementary and synergistic uses (e.g. Tomaselli et al. Citation2018). It has also been cautioned that complementarities can only truly arise when there are equal respect and value for knowledge systems (Rathwell et al. Citation2015). This point was reflected in this research. Concerns were raised during both focus groups about the unequal respect and value of IQ versus western science in some review processes (ones that impact Nunavut and more broadly), suggesting the need to develop a better understanding among proponents and IA stakeholders of the need to equally respect, value, and consider both IQ and western science. Developing detailed guidelines for proponents specifically regarding the integration of IQ, notably IQ values, can help promote equal respect and value, and lead to more meaningful integration. Such guidance might present good practices, including models for compensation offered to knowledge holders, as well as promote the use of community-based knowledge working groups for IQ collection and integration. The NIRB has recently developed a set of technical guides for targeted audiences including proponents, intervenors, and authorizing agencies (NIRB, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c), and has released a draft of Standard Impact Statement Guidelines (NIRB, Citation2018b), all of which may help provide updated guidance to project reviews and contribute to more meaningful and higher-quality assessments, however, there is still a need for specific guidance and detail regarding the inclusion of IQ, notably IQ values, throughout project review. In neighbouring jurisdictions, further progress has been made on this front (e.g. Mackenzie Valley Environmental Review Board Citation2005; Fedirechuk et al. Citation2008), and the established guidelines may be used as a model for the NIRB and other jurisdictions. As recently developed guides begin to be implemented, further work will be needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the guides in practice.

Our results further outlined the challenges to IQ application. Both focus groups' outcomes indicated that knowledge-holders experience consultation fatigue, and frustration regarding unequal compensation for the sharing of their knowledge compared to the scientific knowledge shared by consultants. The issue of consultation fatigue has been observed in other Arctic settings, where there has been pressure to differentiate between ‘increased’ engagement and ‘better’ engagement (Noble et al. Citation2013). The latter may be achieved through earlier consultation, as well as through the availability, accessibility, and communication of information, which would reduce the need to repeatedly consult on the same topics. However, as demonstrated in the focus groups, routine consultation on certain issues and conditions, notably when informed by IQ, may be necessary due to the changing contextual aspects of IQ (e.g. social and economic), as well as due to rapidly changing environmental conditions. Moving ahead, it will be essential to cultivate an understanding of what types of information may be collected and applied broadly to a range of projects, and to approach the application and transfer of knowledge between higher-level and project-based IAs, as well as between projects at the local level, with caution to ensure that the knowledge is relevant and applicable to the context at hand.

Improving the communication and accessibility of information available to both community members and proponents is also important for enhancing participation in the process. It has been highlighted in other regions that a lack of information available to proponents regarding the needs and interests of community members, as well as the limited accessibility and availability of Indigenous knowledge, have resulted in participation and engagement challenges (Udofia et al. Citation2016). But clearly communicating the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders, including the various co-management boards, Inuit organizations, and other intervenors including government departments and agencies, is also needed to ensure that communities understand who will address their specific concerns and who they can contact to express such concerns. Recent research in the Mackenzie Valley region in Canada has similarly outlined the need to clarify and define the responsibilities of regulatory agencies and intervenor organizations to advance environmental decision-making (Arnold et al. Citation2019).

Finally, the results of this research highlight how an IA process informed by IQ may be in a better position to adapt to climatic and environmental changes. The focus group results outlined how, even though certain aspects or instances of IQ may become less sure, due to rapidly changing environmental conditions, such as knowledge of specific sea-ice conditions at certain times of the year, IQ needs to be seen as constantly evolving, responding to, and adapting to change, and the NIRB IA process is equipped to deal with that. Recognizing IQ as a process and a way of knowing, which will transcend generations, rather than as a set of specific facts or beliefs helps advance adaptation efforts (Peloquin and Berkes Citation2009; Ford et al. Citation2010) and can support the IA process in light of climate change and rapidly changing environmental baselines.

Nunavut as a model of indigenous-led IA?

Indigenous-led IA is advancing in the Arctic. Recent case studies of the Tłı̨chǫ Fortune Minerals Nico Mine IA in the Northwest Territories, and the Sivumut Project Review in Northern Quebec highlight emerging approaches to co-managed and co-developed partnerships in Indigenous-led IA (Gibson et al. Citation2018). In both cases, the IA reviews paralleled or shadowed established processes. It has been suggested that jurisdictions and nations ‘that have strong co-management powers may never need to develop an independent [IA] process, because they have developed the background legislation and they have trust in their own government and agents thereof’ (Gibson et al. Citation2018, p. 34). Characteristics of Indigenous-led IA approaches may include: a process guided by Indigenous Knowledge, laws, norms, and values; meaningful community engagement throughout the process and project; a focus on oral discussions and diverse, culturally relevant engagement methods; and a process where the nation has decision-making authority regarding lands and resources (Gibson et al. Citation2016, Citation2018; O’Faircheallaigh Citation2017). However, despite these illustrations, there is no correct or singular template for Indigenous-led IA. How Indigenous-led IA is framed and implemented by Indigenous governments and communities will be dependent on the environmental and cultural context, governance approaches, history, and community objectives. That said, the IA process in Nunavut is one model of a co-management partnership in Indigenous-led IA due to the composition and structure of the NIRB, the indispensable role of IQ in the process and notably in decision-making, and the support from the Nunavut Agreement and corresponding legislation. However, it is also important to note that Nunavut is the only territory that has yet to reach a devolution agreement with the federal government and, as such, the territorial government does not have final decision-making authority regarding land-use and resources. Devolution would be unlikely to change the decision-making ability of the boards, but it would bring authority and control closer to communities. This is not an insignificant quality. Although in almost all IA projects reviewed by the NIRB, the federal minister responsible agreed with the NIRB decision recommendations, a devolution agreement would provide strong legislative backing to future NIRB decisions, and further move towards a model of Indigenous-led IA since the territorial government is comprised mostly of Inuit.

Despite the lack of complete authority, the NIRB and their IA process provide a strong model of a co-management partnership in Indigenous led-IA. This is achieved in part through three key attributes, which may be adopted in other jurisdictions. First, the representation of knowledge-holders and resource-users on the board helps ensure that local and Indigenous knowledge is more effectively applied at all levels of the project review, and can better inform and guide decision-making processes. As was stressed during the focus groups, Inuit representation on the board and the inclusion of IQ throughout the assessment process helps maintain community confidence in the review and decision-making process and ensures that the process is meaningful and connected to communities. Second, culturally relevant engagement processes, such as community roundtables, provide an important opportunity for community members to engage directly with a proponent and other stakeholders prior to the submission of a project’s impact statement. This is requisite to consequential and effective engagement and helps ensure that the proponent hears community concerns and offers an opportunity for them to be addressed before a project assessment is submitted for agency review. Lastly, the responsibility of project monitoring by the regulating agency, in this case the NIRB, helps ensure that, following the review, project operations are undertaken in a way that further integrates and applies local and Indigenous knowledge and values, as well as provides greater accountability and adds to the effectiveness of the IA process.

Conclusion

The role of IQ in the Nunavut IA process shows the potential for Indigenous Knowledge to not just inform an IA process, but also to fundamentally shape and frame it. Nunavut’s IA process provides a model of a co-management and partnership and helps advance our understanding of one model of Indigenous-led IA. The results help frame the role of IQ as an indispensable component of IA practice in Nunavut, notably its role in influencing decision-making, and ensuring that the IA process is reflective, respectful, and meaningful to communities. While the research looked at Nunavut, the results and recommendations can help inform and support other jurisdictions working towards integrating Indigenous Knowledge into IA or moving towards more inclusive and even Indigenous-led IA processes.

In Nunavut limitations to the use of Indigenous knowledge in IA do continue. Such challenges include the unequal values and importance assigned to Indigenous knowledge and western science, the limited availability and accessibility of knowledge and foundational information, and consultation fatigue, which hinders community engagement in IA processes. But Nunavut also shows success and innovations. Through the representation of knowledge-holders and resource-users on the decision-making body, in this case the NIRB, and the inclusion of unique and culturally relevant process steps, such as community roundtables and NIRB-led monitoring, the IA process in Nunavut may be better positioned than other jurisdictions to meaningfully engage with communities, and apply IQ to guide the process and shape decisions. What is still needed is a clarification of the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders in the IA process and clear guidance for proponents regarding the integration of IQ, notably IQ values. In this respect, a key role for such guidance can better promote the treatment of IQ or other ways of knowing in a process, not only at the data collection phases, but even deeper use within the IA process. It also emphasizes the importance of having an early and ongoing proponent/company presence in communities, and meaningful engagement with community members and knowledge holders throughout the process to determine how knowledge and values can guide assessment and improve projects.

The Nunavut case contributes to IA practice by helping to advance understanding of, and approaches to, addressing community and stakeholder expectations, and building capacity for engagement – process qualities emphasized as important in IA best practice (Noble and Hanna Citation2015). The attributes and qualities of Nunavut’s approach provide an illustration of what effective integration of Indigenous Knowledge into IA could look like (Stratos Citation2017; Onfoot Consulting Citation2018). Finally, the unique IA structure and process in Nunavut, and its implementation, can support other jurisdictions as they work to advance the integration into IA of diverse forms of information and knowledge, and different ways of knowing into assessment practice.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from Irving Shipbuilding Inc, the Nunavut Research Institute, and Polar Knowledge Canada through the Northern Scientific Training Program. Accommodation was provided by the Canadian High Arctic Research Station. We are grateful for the important support and contributions of the Nunavut Impact Review Board. The time and comments provided by the peer reviewers are much appreciated.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Armitage D , Berkes F , Dale A , Kocho-Schellenberg E , Patton E. 2011. Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada’s Arctic. Global Environ Change. 21(3):995–1004. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.04.006.

- Arnold LM , Hanna K , Noble B . 2019. Freshwater cumulative effects and environmental assessment in the Mackenzie Valley, Northwest Territories: challenges and decision maker needs. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 37(6):516–525. doi:10.1080/14615517.2019.1596596.

- Nunavut Impact Review Board. 2020c. Authorizing Agencies’ Guide – NIRB Technical Guide Series. Cambridge Bay (Nunavut): Nunavut Impact Review Board. [accessed 2020 Apr 7 ]. https://www.nirb.ca/publications/guides/NIRB%20Authorizing%20Agencies%20Guide.pdf

- Barry RW , Granchinho SCR , Rusk JJ . 2016. Impact Assessment in Nunavut. In: Hanna KS , editor. Environmental impact assessment: practice and participation. 3rd ed. Don Mills (Ontario, Canada): Oxford University Press; p. 267–298.

- Bell T , Briggs R , Bachmayer R , Li S , 2014, September. Augmenting Inuit knowledge for safe sea-ice travel—The SmartICE information system. In 2014 Oceans-St. John’s (pp. 1–9). IEEE.

- Berkes F . 2012. Sacred ecology. Abingdon (Oxon): Routledge.

- Croal, P., Tetreault, C., and members of the IAIA IP Section . 2012. Respecting Indigenous Peoples and Traditional Knowledge. Special Publication Series No 9. Fargo, USA: International Association for Impact Assessment.

- Dowsley M . 2009. Community clusters in wildlife and environmental management: using TEK and community involvement to improve co-management in an era of rapid environmental change. Polar Res. 28(1):43–59. doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.2008.00093.x.

- Ellis SC . 2005. Meaningful Consideration? A Review of Traditional Knowledge in Environmental Decision Making. Arctic. 58(1):66–77.

- Fedirechuk GJ , Labour S , Niholls N 2008. Traditional Knowledge Guide for the Inuvialuit Settlement Region Volume II: using Traditional Knowledge in Impact Assessments. Environmental Studies Research Funds Report No. 153 Calgary, 104 pp

- Ford JD , Pearce T , Duerden F , Furgal C , Smit B . 2010. Climate change policy responses for Canada’s Inuit population: the importance of and opportunities for adaptation. Global Environ Change. 20(1):177–191. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.10.008.

- Ford JD , Smit B , Wandel J . 2006. Vulnerability to climate change in the Arctic: a case study from Arctic Bay, Canada. Global Environ Change. 16(2):145–160. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.11.007.

- Gibson G , Galbraith L , MacDonald A . 2016. Towards meaningful aboriginal engagement and co-management: the evolution of environmental assessment in Canada. In: Hanna KS , editor. Environmental impact assessment: practice and participation. 3rd ed. Don Mills (Ontario, Canada): Oxford University Press; p. 159–180.

- Gibson G , Hoogeveen D , MacDonald A . 2018. Impact assessment in the Arctic: emerging practices of indigenous-led review. The Firelight Group, Edmonton: Submitted to Gwich’in Council International (GCI).

- Gondor D . 2016. Inuit knowledge and environmental assessment in Nunavut, Canada. Sustainability Sci Dordrecht. 11(1):153–162. doi:10.1007/s11625-015-0310-z.

- Government of Canada . 2013. Nunavut planning and project assessment act, S.C. 2013, c. 14, s. 2. Ottawa: Minister of Justice. [accessed 2019 Jul 2 ]. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/N-28.75/

- Government of Canada and Tungavik Federation of Nunavut . 1993. Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act, S.C. 1993, c. 29. Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs. [accessed 2019 Jun. 2 ]. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/N-28.7.pdf

- Government of Canada, & Indigenous and Northern Affairs . 2012. 2008-2010 Nunavut implementation panel: annual report. [accessed 2018 Dec 2 ]. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1351178274391/1542913927498

- Government of Nunavut . 2017. Petroleum resources in Nunavut. Iqaluit: Department of Economic Development & Transportation. [accessed 2018 Dec 20 ]. https://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/2017_petroleum_brochure_eng_0.pdf

- Hanna KS . 2016. Environmental impact assessment: process, practice, and critique. In: Hanna KS , editor. Environmental impact assessment: practice and participation. 3rd ed. Don Mills (Ontario, Canada): Oxford University Press; p. 2–14.

- Houde N . 2007. The six faces of traditional ecological knowledge: challenges and opportunities for Canadian co-management arrangements. Ecol Soc. 12:2. doi:10.5751/ES-02270-120234

- Huntington HP . 2000. Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: methods and applications. Ecol Appl. 10(5):1270–1274. doi:10.2307/2641282.

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami . 2018. National inuit strategy on research. Ottawa: ITK. [accessed 2018 Dec 2 ]. https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ITK_NISR-Report_English_low_res.pdf

- Jackson W . 2003. Methods: doing social research. Toronto: Prentice Hall.

- Jamasmie C 2018. Gold mines to inject new life into Canada’s far north. http://www.mining.com/gold-mines-inject-new-life-canadas-far-north/.

- Karetak J , Tester F , Tagalik S . Eds. 2017. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: what the Inuit have always known to be true. Fernwood: Black Point.

- Krupnik I , Aporta C , Gearheard S , Laidler GJ , Holm LK . 2010. SIKU: knowing our ice. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Laidler GJ . 2006. Inuit and scientific perspectives on the relationship between Sea Ice and climate change: the ideal complement? Clim Change. 78(2–4):407. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9064-z.

- Laidler GJ , Ford JD , Gough WA , Ikummaq T . 2009. Travelling and hunting in a changing Arctic: assessing Inuit vulnerability to sea ice change in Igloolik, Nunavut. Clim Change. 94(3–4):363. doi:10.1007/s10584-008-9512-z.

- Mackenzie Valley Environmental Review Board . 2005. Guidelines for incorporating traditional knowledge in environmental impact assessment. Yellowknife (NWT): MVERB. [accessed 2018 Dec 18 ]. http://reviewboard.ca/upload/ref_library/1247177561_MVReviewBoard_Traditional_Knowledge_Guidelines.pdf

- Menzies CR . 2006. Traditional ecological knowledge and natural resource management. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [accessed 2019 Aug 27 ]. from Project MUSE database

- Metuzals J , Hird JM 2018. “The Disease that Knowledge Must Cure”?: sites of uncertainty in Arctic Development. Arctic Yearbook 2018.

- Morgan DL . 1996. Focus groups. Annu Rev Sociol. 22(1):129–152. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129.

- Nadasdy P . 2003. Reevaluating the co-management success story. Arctic. 56(4):367–380. doi:10.14430/arctic634.

- Nakashima DJ 1990. Application of native knowledge in EIA: inuit, eiders and Hudson Bay oil. Canadian environmental assessment research council. [accessed 2019 Jun 14 ] http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/acee-ceaa/En107-3-20-1990-eng.pdf

- Noble B , Hanna K . 2015. Environmental assessment in the Arctic: a gap analysis and research agenda. Arctic. 68(3):341–355. doi:10.14430/arctic4501.

- Noble B , Ketilson S , Aitken A , Poelzer G . 2013. Strategic environmental assessment opportunities and risks for Arctic offshore energy planning and development. Mar Policy. 39:296–302. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.011

- Nunami Stantec Limited . 2018. Strategic environmental assessment for Baffin Bay and Davis Strait: environmental setting and review of potential effects of oil and gas activities. Cambridge Bay (Nunavut):Nunavut Impact Review Board.

- Nunavut Impact Review Board . 2015. Final hearing report – Kiggavik uranium mine project. Cambridge Bay (Nunavut): Nunavut Impact Review Board. [accessed 2020 May 9 ]. 150508-09MN003-NIRB Final Hearing Report-OT9E.pdf

- Nunavut Impact Review Board . 2018a. NIRB Five Year Strategic Plan 2018-2020. Cambridge Bay (Nunavut): Nunavut Impact Review Board. [accessed 2018 Dec 10 ]. http://nirb.ca/publications/Strategic%20Plan/180401-NIRB%202018-22%20Strategic%20Plan_English-OEDE.pdf

- Nunavut Impact Review Board . 2018b. Standard guidelines for the preparation of an impact statement. Cambridge Bay (Nunavut): Nunavut Impact Review Board. [accessed 2020 Apr 7 ]. http://www.nirb.ca/publications/Rules%20of%20Procedure/181206- DRAFT%20NIRB%20Standard%20IS%20Guidelines_English-OEDE.pdf

- Nunavut Impact Review Board . 2020a. Proponents’ Guide – NIRB technical guide series. Cambridge Bay (Nunavut): Nunavut Impact Review Board.[accessed 2020 Apr 7 ]. https://www.nirb.ca/publications/guides/NIRB%20Proponents%20Guide.pdf

- Nunavut Impact Review Board . 2020b. Intervenors’ Guide – NIRB technical guide series. Cambridge Bay (Nunavuy): Nunavut Impact Review Board. [accessed 2020 Apr 7 ]. https://www.nirb.ca/publications/guides/NIRB%20Intervenors%20Guide.pdf

- Nunavut Impact Review Board . n.d.a. Board Members | Nunavut Impact Review Board. [accessed 2018 Nov 30 ]. http://www.nirb.ca/board-of-directors

- Nunavut Impact Review Board . n.d.b. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit | nunavut Impact Review Board. [accessed 2018 Dec 4 ]. http://www.nirb.ca/inuit-qaujimajatuqangit

- Nunavut Impact Review Board . n.d.c. Staff | nunavut impact review board. [accessed 2018 Nov 30 ]. http://www.nirb.ca/staff-intro

- O’Faircheallaigh C . 2017. Shaping projects, shaping impacts: community-controlled impact assessments and negotiated agreements. Third World Q. 38(5):1181–1197. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1279539.

- Onfoot Consulting . 2018. Arctic environmental impact assessment workshop report. Yellowknife (NWT):Sustainable Development Working Group: Arctic Council.

- Patton MQ . 2002. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3 ed. Thousand Oaks (California): Sage Publications.

- Pearce T , Ford J , Willox AC , Smit B . 2015. Inuit Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), subsistence hunting and adaptation to climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Arctic. 68(2):233–245. doi:10.14430/arctic4475.

- Peloquin C , Berkes F . 2009. Local knowledge, subsistence harvests, and social–ecological complexity in James Bay. Hum Ecol. 37(5):533–545. doi:10.1007/s10745-009-9255-0.

- QSR International Pty Ltd . 2018. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software (Version 12).

- Rathwell K , Armitage D , Berkes F . 2015. Bridging knowledge systems to enhance governance of environmental commons: A typology of settings. Int J Commons. 9(2):851–880. doi:10.18352/ijc.584.

- Richards L , Morse JM . 2013. Readme first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Riedlinger D , Berkes F . 2001. Contributions of traditional knowledge to understanding climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Rec. 37(203):315–328. doi:10.1017/S0032247400017058.

- Saldaña J . 2009. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Sallenave J . 1994. Giving traditional ecological knowledge its rightful place in environmental impact assessment. North Perspect. 22(1):1–7.

- Senkow M , Russer M , Bigio A , Sharpe S 2018. Nunavut: mining, Mineral Exploration And Geoscience Overview 2018. Iqaluit: CIRNAC Mineral Resources Division (Regional Office). [accessed 2019 Jul 2 ]. https://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/exploration_overview_2018-english.pdf

- Simpson L . 2004. Anticolonial strategies for the recovery and maintenance of indigenous knowledge. Am Indian Q. 28(3):373–384. doi:10.1353/aiq.2004.0107.

- Statistics Canada . 2017. Census Profile, 2016 Census - Nunavut [Territory] and Canada [Country].[accessed 2019 Jun 15 ]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=62&Geo2=&Code2=&Data=Count&SearchText=Nunavut&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=62

- Stevenson MG . 1996. Indigenous knowledge in environmental assessment. Arctic. 49(3):278–291. doi:10.14430/arctic1203.

- Stratos . 2017. Pan-territorial environmental assessment and regulatory board forum final report. Cambridge Bay (Nunavut):Third annual Pan-Territorial Board Forum.

- Tomaselli M , Kutz S , Gerlach C , Checkley S . 2018. Local knowledge to enhance wildlife population health surveillance: conserving muskoxen and caribou in the Canadian Arctic. Biol Conserv. 217:337–348. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.\11.010

- Udofia A, Noble B, Poelzer G . 2016. Aboriginal Participation in Canadian Environmental Assessment: Gap Analysis and Directions for Scholarly Research, Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 18(03):1–28.

- UN General Assembly . 2 October 2017. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: resolution/adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007. A/RES/61/295. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html [accessed 2019 Aug 25

- Usher PJ . 2000. Traditional ecological knowledge in environmental assessment and management. Arctic. 53(2):183–193. doi:10.14430/arctic849.

- Wascher D 2013. Focus group. accessed Jul 12, 2019]. http://www.liaise-kit.eu/ia-method/focus-group.

- Wheatley M . 2001. Caribou co-management in Nunavut: implementing the Nunavut land claims agreement. The Ninth North American Caribou Workshop.

- White G . 2006. Cultures in collision: traditional knowledge and Euro-Canadian governance processes in northern land-claim boards. Arctic. 59(4):401–414.