ABSTRACT

Major projects, in sectors such as transport, energy, minerals and water, have long life cycles and can have significant local and regional environmental and socio-economic impacts. The impacts of the construction stage can be particularly damaging, if not managed well. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) seeks to anticipate such impacts, mitigate adverse and enhance positive impacts through design innovations and associated conditions. However, the approach is only as good as the implementation of such innovations and conditions. The issue of monitoring and auditing of actual, as against predicted, impacts is an Achilles heel in the planning and assessment process. Hinkley Point C (HPC) nuclear power station in the UK is currently one of the largest construction projects in Europe. A recent study of the live project provides a unique insight into the actual local impacts of the early construction years, and appropriate methods of assessment. It identifies KPIs, examines monitoring data, and audits findings against the predictions. The results show varying performance across key impact sectors. Explanations of differences are set out, together with recommendations for improving monitoring and auditing practice.

1. Introduction

A major Achilles heel of EIA as practised in many countries has been a focus on the period before the project authorisation decision which, at worst, can lead to a ‘build it and forget it’ approach (Culhane Citation1993). Yet many major projects, in sectors such as transport, energy, minerals, waste and water, have long life cycles. EIA should not stop at the decision; it should be an adaptive process to achieve good socio-economic and environmental management over the life of the project. Many years ago, Holling (Citation1978) recommended an adaptive EIA process to cope with decision-making under uncertainty. He advocated periodic reviews of the EIA through a project’s lifecycle, with a ‘predict, monitor and manage approach’. This means including follow-up monitoring and auditing as essential elements in the EIA process (Arts et al Citation2001; Morrison-Saunders and Arts Citation2004; IAPA Citation2005; Bjorkland Citation2013; Jones and Fischer Citation2016; Pinto et al Citation2019; Glasson and Therivel Citation2019). Such follow-up can provide evidence about the accuracy of EIA predictions, the implementation of conditions, and indeed the utility of particular monitoring processes, which in turn can help to improve the management of projects through their life cycle and provide evidence-based learning for future projects.

This article uses the case of new nuclear build (NNB) projects. These are some of the largest current, and often particularly contentious, construction projects in the world. The country focus is on the United Kingdom where the last NNB project to be completed was Sizewell B, in East Anglia, in 1995. Uniquely for that project, a team from the Impact Assessment Unit (IAU) at Oxford Brookes University monitored and audited the local community impacts of the seven-year construction programme (Glasson and Chadwick Citation1995; Chadwick and Glasson Citation1999). Subsequently, the data from the Sizewell B study has provided valuable evidence for the recent planning of new NNB in the United Kingdom. However, that evidence is now over 25 years old; NNB projects, socio-economic conditions and planning and assessment methods change and evolve. There is a need for new monitoring and auditing research to provide better data for current project management and future learning for NNB projects and indeed for other major projects.

The New Nuclear Local Authorities Group (NNLAG) in the United Kingdom recognised this need. NNLAG is a Local Government Association Special Interest Group, consisting of fifteen Local Authorities that already host or are likely to host NNB projects. NNLAG’s purpose is to share knowledge, information and best practice regarding new nuclear, and to use such information in discussion with key stakeholders, including Central Government and major developers. Hinkley Point C NNB in Somerset in South West England, the first NNB since Sizewell B, began main construction in 2016, and provides the opportunity for new monitoring and auditing research, the results of which could flow into subsequent developments – the next one planned being Sizewell C in Suffolk.

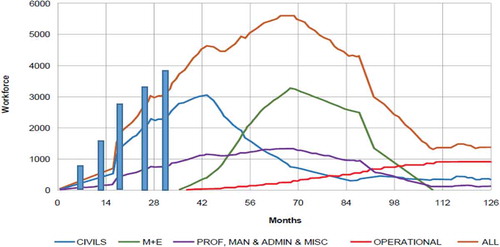

A team from the IAU of Oxford Brookes University undertook the research in 2018 and 2019. It was a relatively short study of about 9 months. It covered the first two and half years of a twelve-year HPC construction programme, and is before peak construction. HPC is currently one of the largest construction projects in Europe. It is a £20bn project, with a current workforce of over 5000, and rising. The project is located in the district of West Somerset and Taunton Deane in a rural location of Somerset in Southwest England. The Environmental Statement (ES) for the project identified a number of key issues, including for example the impacts of a large incoming workforce on traffic, accommodation, and on services such as health and policing. Examples of mitigation measures include the provision of Park and Ride facilities on the nearby M5 motorway to reduce car vehicle impacts, a new bypass of the village of Cannington, and two purpose built substantial construction worker accommodation campuses, with health facilities, with one on site and the other in the local town of Bridgwater ().

This article explores opportunities and issues associated with monitoring and auditing in planning and assessment processes for major projects, before setting out the research questions and research methodology. Further sections provide summaries of some of the key findings, and seek to clarify the factors behind the variations in performance across a range of impact sectors. The article then draws some implications for monitoring, auditing and management practice in the spirit of an adaptive EIA process, and in light of recent EU and UK regulations now requiring such monitoring (EU Citation2014, Citation2017; HMG Citation2017). Whilst the focus is on NNB projects, the approach and findings will be relevant and of interest to researchers and key stakeholders involved in many other types of major projects.

2. Monitoring and auditing issues

Of key importance for the management of the local and regional impacts of a project are the effectiveness of the monitoring and auditing structures and procedures put in place for the project and their operation in practice from various stakeholder perspectives. This has been the subject of some academic debate over the last two decades (see, e.g. Marshall et al. Citation2005; IAPA Citation2005; Jones and Fischer Citation2016; Pinto et al. Citation2019), plus some example of developer and consultancy good practice (see for example Glasson Citation2005; Highways England Citation2016). Drawing on this literature, sets out some good practice considerations for monitoring and auditing. This includes, for example, the importance of a clear monitoring and auditing programme, with open and regular reporting, and a partnership between the various stakeholders involved (e.g. developer, local authority and local community), with information openly shared, and independently verified.

Table 1. Some good practice considerations for monitoring and auditing

Notwithstanding the benefits of monitoring and auditing set out in , good practice is limited. Some key barriers include lack of mandatory requirement, the costs involved, unenforced legislation, and little learning incentive for developers with one-off projects. Whilst there are examples of follow up requirements in some EU states, practice can be poorly developed (Runhaar et al. Citation2013). In the United Kingdom there has been little evidence of good practice, especially for the vital construction stage of major projects, as noted in a recent report by the National Infrastructure Projects Association (NIPA Citation2019):

There has been little research on the results of the effectiveness of the environmental monitoring and management during the construction of NSIPs (Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects) … … The sharing of the findings of monitoring could improve decision making, could provide reassurance to communities for whom the anticipation of impact can be more daunting than the reality, and enable developers to improve environmental management practices.

However, even with a fair mandatory wind, as now in the EU, good practice monitoring and auditing faces a number of operational problems. These were set out by Chadwick and Glasson (Citation1999) in relation to the earlier monitoring study of the socio-economic impacts of the construction stage of Sizewell B, which was the last nuclear power station to be built in the United Kingdom and which became fully operational in 1995 ().

Table 2. Some operational problems in monitoring and auditing studies for major projects

3. Research approach: questions, objectives and methods

Using the case study of Hinkley Point C, the research seeks to address three inter-related questions, with a particular focus on the first question. To what extent: (i) do the EIA predictions for the impacts of early NNB construction match the actual impacts (prediction audit); (ii) are the conditions attached to the development permission met in practice (compliance audit) and (iii) are the procedures used by key stakeholders for monitoring and auditing effective and appropriate (process audit)? It is important to learn from the actual experience of NNB construction and operation. Resources spent on baseline studies and predictions may be of little value unless there is some way of testing the predictions and determining whether mitigation and enhancement measures are appropriately applied. Such learning involves both impact monitoring (the identification and measurement of actual impacts) and impact auditing (the comparison of actual with predicted impacts) (Glasson et al. Citation2020).

The research involved a series of stages: setting the research approach and key parameters, monitoring and auditing impacts across socio-economic and biophysical sectors, undertaking contextual studies, drawing overall conclusions, with identification of data and monitoring gaps, and making recommendations for improving practice. Key parameters included for example: a focus on testable predictions, the use of publicly available information to maximise credibility and the auditing of impacts across a range of scales, as included in predictions. Brief contextual studies included a review of the effectiveness of the monitoring structures and procedures put in place for the HPC construction project, and their operation in practice from various stakeholder perspectives. There was also a comparison of those monitoring structures and procedures with those for three other major projects studies: London 2012 Olympics project – legacy; Crossrail – construction nearing completion; and Wylfa Newydd NNB – examination completed.

The research covered six impact sectors: economic development, transport, social and community, accommodation, environmental health and the biophysical environment. For each sector, the research had three main steps:

Identifying – clarifying strategic issues and obligations; indicators and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs); and key data sources, drawing in particular on the HPC project ES (EDFE Citation2011) and Development Consent Order (DCO)Footnote1 (Planning Inspectorate Citation2013), Section 106Footnote2 and the local authorities’ Local Impact Reports (Somerset Local Councils Citation2012).

Monitoring – establishing findings, key indicator trends and events over the main construction stage to date, drawing on publicly available information.

Auditing – assessing degree of accuracy of monitoring findings against predictions and conditions, and explanations of any differences, gaps in monitoring process and future proposals.

The major and lengthy first step in each sector study was the identification of key issues, indicators and KPIs. In some cases, this was complicated with changing KPIs and developer obligations over time. In addition to the information in the ES, DCO etc, there were valuable meetings with representatives of the Somerset local authorities, and staff from the developer, EDFE (Electricite de France Energy). These meetings helped to identify data sources, and issues for investigation in the various sectors; for example, there was a particular local authority concern about the impacts of inmigrant construction workers on the local housing market.

For the second, monitoring step, the availability of information also varied between, and within, sector studies. Valuable online data sources included the various ‘data dashboards’ produced by the Socio-Economic Advisory Group and the Transport Review Group, and the minutes of various community fora, all of which were established for HPC construction monitoring. These include the Community Forum, Transport Forum, and Main Site Neighbourhood Forum; they have an independent chair. They include officers of the local councils, the developer, and other stakeholders; are open to members of the public and their minutes are publicly available.

The third, audit step, for each sector seeks to compare actual with predicted impacts for specific indicators and KPIs, to explain any differences between them, to identify gaps in monitoring and to make recommendations for future practice. The audit assessments are the independent findings of the IAU research team, based on publicly available monitoring information. For quantitative information, accurate assessments are estimated as being within a range of ±10% of predictions. The research team applied a simple colour coding (RAG system) for each indicator/KPI, ranging from Dark Green (very accurate/compliant) through Amber and Orange, to Dark Red (very inaccurate/non-compliant). Blue indicates no information available/auditing not possible at the time of the study (). In some cases, there is a split assessment to reflect a mix of audit outcomes to date.

Table 3. RAG colour coding used in auditing for each sector

4. Findings – an overview

provides an overview of the audit of the accuracy of actual as against predicted impacts. The findings draw on predictions in the ES and monitoring information on actual impacts from data sources and interviews noted in section 3. The public availability of a flow of accurate monitoring data is the key to the auditability of impact predictions. The research found the most adequate monitoring information for the transport, and social and community impacts (especially health and community services) sectors. There is also some good information for much of the economic development sector, although there are some gaps. There is more fragmented monitoring information for the accommodation sector, and publicly available information is very patchy, and in several cases completely absent, for many of the impact indicators in the environmental health and biophysical environment sectors. As such, in several cases, the available monitoring data proved inadequate to audit ES predictions and the DCO1/S1062 requirements and obligations. There may be a variety of reasons for the variations in adequacy of the monitoring data. There are well-developed monitoring systems for some quantitative indicators, such as traffic flows and, for this project, for health and community safety impacts. Other part explanations may be the degree of specificity of project requirements and obligations, and the relative efficiency and organisation of the various monitoring groups involved in the HPC project.

Table 4. Audit summary – of HPC sectors actual impacts against predicted impacts

shows good performance against predictions for the economic development and transport sectors, and especially for the social and community sector, including health and community safety. There is more mixed performance against predictions for the accommodation sector, with more spatially concentrated construction worker use of private rental accommodation than predicted. The blue colour coding for the environmental health and biophysical environment reflects the absence of publicly available monitoring information at the time of the research. Section 5 provides a more detailed analysis of three of the sectors – economic development, transport and accommodation. A discussion of the key factors behind variations in performance against predictions and conditions follows in section 6.

5. Findings – some sector examples

5.1. Economic development

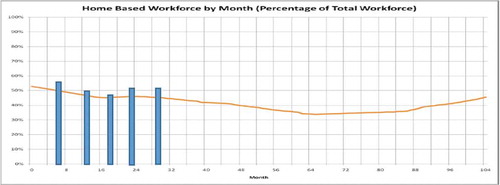

The economic development sector focuses on HPC construction employment, skills and supply chain issues, and on managing impacts on other economic sectors. This is a vital starting point for monitoring and auditing of a range of socio-economic impacts. The extent of local content of construction employment has many local and regional direct and indirect effects. Locally based construction workers already have accommodation, and their families, as relevant, have on-going and established interactions with a wide range of local services, including for example schools, doctors and policing. In contrast, inmigrant workers place new and additional demands on local accommodation and other local services. The use of local suppliers can have a multiplier effect on the local economic benefits of the project, but there may also be some potential disbenefits, associated for example with job displacement from local firms, wage inflation, and specific sector impacts, especially on tourism in Somerset. summarises some of the findings to date. compares estimated workforce numbers against actual over the early years of the construction workforce curve showing a reasonable, if slightly higher, level of actual with predicted numbers. focuses on the percentage of local recruitment from within the 90-min Construction Daily Commuting Zone, showing that local content has closely achieved the predictions for the early years. The RAG coding in is generally very positive in relation to other aspects of employment, with good recruitment from women, high level of apprenticeships, and transformational educational initiatives for the local area. Similarly, for the supply chain, there is much evidence of good use of local and regional suppliers. Further, potential negative impacts on local tourism appear offset by implementation of various mitigation measures supporting the important Somerset tourism economy. There is also the added bonus for some tourism accommodation providers of much fuller occupancy over the calendar year from take-up by construction workers.

Figure 2. Construction workforce labour demand curve – estimated (curves) and actual (cols) workforce numbers to date (Month 0 is taken as mid-2016)

Figure 3. Actual local content percentage (cols) compared with predicted (curve), within the 90-minutes Construction Daily Commuting Zone (CDCZ)

Table 5. Some examples of audited employment predictions

5.2. Traffic and transport

shows that the Park and Ride (P&R) provision, which switches workers from their cars at M5 junctions into buses to the site, is working well, with over 90% of workers using the scheme. However, the car share usage to the P&R sites is below target, but hopefully this will improve with further promotion. HGV deliveries are also keeping to limits; for example, the Monday-Friday actuals are well below the daily limit of 750 vehicles. The unexpected traffic issue has been the impact of some of the travelling workforce fly parking, causing much disturbance to Somerset village communities.

Table 6. Some examples of audited traffic and transport predictions

5.3. Accommodation

provides a summary snapshot of some of the local accommodation impacts. These show a much more spatially concentrated distribution of inmigrant workers than predicted, especially in the town of Bridgewater, and proportionately many more in private rented accommodation than predicted. However, assessment here was complicated by fragmented sets of accommodation data; lack of monitoring against thresholds for the majority of the KPIs; and lack of availability of some data specific to the Construction Development Commuting Zone. Further, and of particular importance for this monitoring and auditing exercise, most of the accommodation predictions of the geographical distribution and tenure of the inmigrant construction workforce relate to peak construction employment; the project is not at that stage yet – and there are no intermediate predictions.

Table 7. Some examples of audited accommodation predictions

6. Explanation of findings

The explanation of findings and differences between actual and predicted impacts for Hinkley Point C raises a number of positive and negative factors influencing impacts at this early stage in the ten-year construction programme. There are many positive findings, often resulting from the effective implementation of mitigation and enhancement measures and conditions. These for example include the transformational skills, training and education provision; the on-site campus with its high quality Medical Centre; and the Workers Code of Conduct and community safety initiatives. The purpose of the Code of Conduct is to set clear expectations for the social behaviour of workers when within the community. Transport initiatives include the Park and Ride facilities, the Cannington Bypass, and the bus to site system. There are also a whole array of management plans and, primarily developer (EDFE), funding initiatives.

Factors behind some of the more negative findings, and differences between actual and predicted impacts, can be grouped into a number of categories, as set out in . The long delay between project consent and start of main construction had implications for the currency of baseline data for both the project and the local area. Some monitoring indicators lacked clarity, as did the timing of when certain mitigation measures should be in place (e.g. late completion of temporary jetty into the Severn Estuary meant more heavy goods traffic by road to the site). A focus of predictions on peak construction also resulted in an absence of intermediate points in the construction stage for comparing actual and predicted; this was especially an issue for the accommodation sector.

Table 8. Some factors explaining differences between actual and predicted impacts

In terms of process audit, the research also identified some weaknesses in the organisation and resourcing of the monitoring and auditing activities for the project, between the developer and the local authorities, which limited the effectiveness of the process for some impact sectors. Monitoring groups, and their activities, worked well for some sectors, for example for health and community safety, and for much of transport and employment, with a regular reporting of information against KPIs. For others, especially accommodation, organisation and data output was more fragmented and less useful for auditing purposes. There was no environment-monitoring group, and a dearth of publicly available information on environmental health and biophysical environmental impacts.

7. Recommendations for monitoring and management practice

There are many positive findings from the auditing of the early years of the HPC construction project, often resulting from the effective implementation of mitigation and enhancement measures and conditions. However, the findings also raise a number of issues. This section considers some specific recommendations for a refresh for the monitoring and auditing of the next phases of the HPC construction project, followed by an outline of generic recommendations for future NNB developments. The recommendations draw partly on the comparative practice case studies undertaken in the research.

For the current HPC project, there are many monitoring organisation and data recommendations. These include for example reviewing the operational effectiveness of the various monitoring groups. There is an urgent need for an environment-monitoring group and an improvement in the operation of the accommodation-monitoring group to optimise data opportunities. The London Crossrail project provides a good example of environmental monitoring (Crossrail Citation2018).The monitoring system also needs to deliver accurate and disaggregated employment information, especially on local content by skill category and by disadvantaged and under-represented groups. Similarly, the London Olympics project provides a good example of monitoring and auditing the impacts of the project construction on a wide range of population groups in London and beyond (ODA Citation2011). The developer, EDFE has responded positively to many issues and recommendations, including the initiation of a major review, in the spirit of adaptive environmental assessment and management, to consider the implications of a revised higher level of peak construction employment, and to update and refresh various strategies and plans, including those for accommodation, health and community safety. Changes are also in hand with the monitoring process in relation to key areas of employment and accommodation, and the introduction of an environment-monitoring group to cover physical environmental topics.

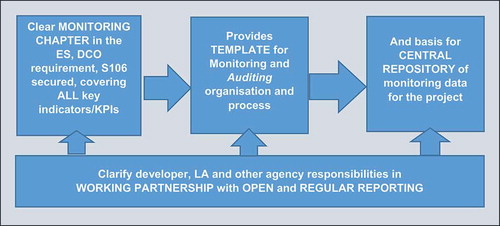

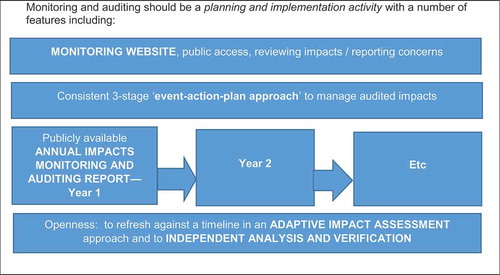

Some of the generic recommendations for future NNB, and other large developments more generally, are diagrammatically set out in and , distinguishing between the pre-construction planning and assessment stage and the construction stage. For example, for pre-construction there should be a monitoring chapter in the ES, referenced as a DCO requirement by the Examining Authority, which brings together the key indicators/KPIs across all the socio-economic and biophysical topic areas. This can provide the template for subsequent monitoring and auditing over the project lifecycle, and the basis for a central repository of monitoring data for the project. There should be service level agreements for local authorities to adequately monitor and report the wide-ranging impacts of the construction of major projects.

Figure 4. Some interim recommendations – Generic for future NNB and other large projects – Pre-construction planning and assessment – primarily for developer (with LA involvement as appropriate)

Figure 5. Some interim recommendations – Generic for future NNB and other large projects – Construction stage – primarily for developer (but with LA involvement as appropriate)

Recommendations for the construction stage include, for example, the production of a publicly available Annual Impacts Monitoring and Auditing Report. As for the current HPC system, there should be provision for Community Fora – but also for a Monitoring Website, with public access, and to which members of the public can report their concerns on project performance back to the developer and local authorities. A three stage ‘event-action-plan’ approach seeks to provide a more consistent approach to handling impact issues. This includes: (1) a trigger level to provide an early warning of problems; (2) an action level, at which action is taken before an upper limit of impacts is reached; and (3) a target level, beyond which a pre-determined plan response is initiated to avoid or rectify any problems.

The ES for the Wylfa Newydd proposed NNB in North Wales provides a good example of a project construction-monitoring framework, and a consolidated list of the developer’s environmental and sustainability corporate policies for the project. It also provides a comprehensive listing of monitoring and reporting information outlined in the s106 with, for example, quite specific monitoring requirements for project supply chain and workforce accommodation data (Horizon Nuclear Power Citation2019).

8. Conclusions

Until the advent of the requirements and guidance under the revised EU EIA Directive (EU Citation2014, Citation2017) project monitoring and auditing were not mandatory in EU states. As noted earlier, even where there have been examples of regulatory requirements in some EU states, monitoring and auditing is limited in practice. In other cases, it may be that practice is ahead of regulation, with some enlightened developers and consultants realising some of the benefits of follow-up. However, certainly in the case of the United Kingdom, there is a dearth of detailed follow-up studies, especially for major projects. This situation should improve with the new regulations, adopted in UK EIA regulations (HMG Citation2017) – even with the United Kingdom leaving the EU!

The HPC research provides an insight into the relationship between actual and predicted impacts across six key socio-economic and physical environment sectors of a major project. It also identifies some unforeseen events, and management responses. The prediction and compliance audits show that performance varies, but there are many examples of good outcomes, often reflecting the application of required mitigation and enhancement measures. Economic development findings show generally good predictions and compliance for workforce and supply chain impacts. Indeed, the enhancement measures for skills and training initiatives for the local employees have been quite transformative for the Somerset area. The outcomes to date for transport predictions, with mitigation measures, including the P&R system and coach transfer to site, have also been good, although the unexpected incidence of fly parking caused some serious community concern. There are also positive findings for many social and community impact areas. Mitigation measures, such as the on-site medical campus, and the Worker’s Code of Conduct, have been effective at minimising negative impacts on the local NHS provision and on local community safety.

In other areas, there are examples of differences between actual and predicted impacts. The accommodation predictions suffer in particular from a lack of predictions for key phases of the construction stage, leading to a mismatch between the actual early construction (civils work) phase and predicted peak construction phase impacts. Other determinants of mismatch between actual and predicted impacts across the sectors included for example, time delays in commencement of construction project, changes in baseline conditions, project modifications and lack of clarity on definition of some indicators. For some areas, an absence of data limits judgement. This is the case for impacts on environmental health and the biophysical environment. Whilst there is good regulation of these impact areas in the United Kingdom, with various standards and thresholds, and with monitoring by the developer and relevant agencies, the researchers found little publicly available information to confirm this, other than a relatively low level of local complaints.

A process audit shows some strengths but also some weaknesses in the organisation and resourcing of the monitoring and auditing activities, between the developer and the local authorities for the construction stage of the HPC project. For example, in addition to the absence of a clear project group responsible for environmental monitoring, other organisational issues included the absence in several sectors of clear KPIs, irregular reporting of some indicators and a lack of a robust and consolidated approach to the monitoring exercise, as set out in the ES and reviewed in the examination process. The research recommendations indicate some ways of improving monitoring and auditing practice, both for this project and for future NNB and major projects more widely. These include, for example for pre-construction, the importance of a monitoring chapter in the ES, referenced as a DCO/planning permission requirement by the examining authority, bringing together the key indicators/KPIs across all the socio-economic and biophysical topic areas. This can then provide a template for subsequent monitoring and auditing in the construction stage and beyond, and for a publicly accessible repository of project impact data.

From such findings, we regard the Hinkley Point C construction stage auditing and monitoring research as a particularly useful and timely study, which can provide pointers for hopefully more and better monitoring and auditing activity. It is a mega-construction project, with wide ranging impacts. It is a live and ongoing project; there are implications for future stages of the long HPC construction cycle. In addition, the plan is for HPC to be the first of a new generation of UK NNB projects, and there are lessons for those projects. Indeed, stakeholders are already using the findings of the research in the planning and assessment for the next UK NNB project, at Sizewell C in East Anglia (EDFE Citation2020). The findings and recommendations are also relevant to major projects more generally. The identify, monitor and audit approach, and the RAG colour coding of findings, provided a logical research approach that was clearly understandable for the stakeholders involved. There were some challenges in the approach, especially in sifting through a mass of ES, Management Plans and Local Impact Reports documentation to identify key indicators, some of which changed over time, and in finding monitoring information for some sectors as noted. At this stage, the plan is for the research team to revisit the project, and such challenges, around peak construction, in a further stage of monitoring and auditing, as part of an adaptive assessment process.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the funding support of the New Nuclear Local Authorities Group (NNLAG) for the Hinkley Point C monitoring and auditing study. NNLAG is a Local Government Association (LGA) Special Interest Group, consisting of fifteen Local Authorities from across the UK that already host or are likely to host nuclear new build projects. NNLAG’s purpose is for local authorities to share knowledge, information and best practice regarding new nuclear, and to provide a mechanism for local authorities, as elected representatives of local areas, to discuss and make representations direct to Government regarding the development of new nuclear and of nuclear-related connection/transmission projects. NNLAG’s member local authorities are Allerdale Borough Council, Isle of Anglesey County Council, Copeland Borough Council, Cumbia County Council, East Suffolk Council, Essex County Council, Lancaster City Council, Maldon District Council, Sedgemoor District Council, Folkestone & Hythe District Council, Somerset County Council, South Gloucestershire Council, Suffolk County Council, and Somerset West & Taunton Council. Particular thanks are due to members of the NNLAG Steering Group for the research: Michael Moll (Suffolk CC), Gillian Ellis-King (S. Gloucestershire DC), Andy Coupe (Somerset CC), Guy Kenyon (Cumbria CC) and Tom Day (Essex CC).

The authors also wish to acknowledge their appreciation of the contributions of the anonymous referees to the improvement of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Development Consent Order (DCO) is the term used under the 2008 Planning Act in England for the ‘planning permission’ associated with Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs), such as energy, transport, water and waste projects.

2. A Section 106 (s106) is a legal agreement between an applicant seeking planning permission and the local planning authority, which is used to mitigate the impact of the project on the local community and infrastructure.

References

- Arts J, Caldwell P, Morrison-Saunders A. 2001. EIA follow-up: good practice and future directions – findings from a workshop at the IAIA 2000 Conference. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 19(3):175–185. doi:10.3152/147154601781767014.

- Bjorkland R. 2013. Monitoring: the missing piece. A critique of NEPA monitoring. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:129–134. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2013.07.001.

- Chadwick A, Glasson J. 1999. Auditing the socio-economic impacts of a major construction project: the case of Sizewell B nuclear power station. J Environ Plann Manage. 42(6):811–836. doi:10.1080/09640569910849.

- Crossrail Ltd. 2018. Good practice documents: environmental dashboards. London: Crossrail.

- Culhane PJ. 1993. Post-EIS environmental auditing: a first step to making rational environmental assessment a reality. Environ Prof. 15(1):66–75.

- EDFE. 2011. Hinkley Point C environmental statement. London: EDFE.

- EDFE. 2020. Sizewell C environmental statement. London: EDFE.

- EU. 2014. Directive 2011/92/EU, as amended by Directive 2014/52/EU, on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment. Brussels: EU.

- EU. 2017. EU Guidance on the preparation of the Environmental Impact Assessment Report (EIAR). Brussels: EU.

- Glasson J. 2005. ‘Better monitoring for better impact management: the local socio-economic impacts of constructing Sizewell B nuclear power station’. Impact Assess Project Appraisal July. 23(3):215–226. doi:10.3152/147154605781765535.

- Glasson J, Chadwick A. 1995. Local socio-economic impacts of the Sizewell B PWR construction project. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University, Impacts Assessment Unit.

- Glasson J, Durning B, Broderick M, Welch K 2020 Study on the impacts of the early stage construction of the Hinkley Point C (HPC) nuclear power station: monitoring and auditing study final report. The Oxford Brookes University repository. doi:10.24384/xeb3-7x48

- Glasson J, Therivel R. 2019. Introduction to environmental impact assessment: 5th edition –chapter 7 monitoring and auditing: after the decision. New York: Routledge.

- Highways England. 2016. Post opening project evaluation (POPE) of major schemes: meta analysis 2015. Guildford: Highways England.

- HMG. 2017. The Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017SI No. p. 572. London: SO.

- Holling C. S. ed. 1978. Adaptive environmental assessment and management. New york: Wiley.

- Horizon Nuclear Power. 2019. [accessed 2019 Jun 11]. https://www.horizonnuclearpower.com/our-sites

- IAPA (Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 2005. Special issue on EIA Follow-up. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 23(3):191–196.

- Jones R, Fischer T. 2016. EIA follow-up in the UK—A 2015 update. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 18(1):1–22. doi:10.1142/S146433321650006X.

- Marshall R. 2005. EIA follow-up and its benefits for industry. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 23(3):191–196. doi:10.3152/147154605781765571.

- Marshall R, Morrison-Saunders A, Arts J. 2005. EIA follow-up: international best practice principles. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 23(3):175–181. doi:10.3152/147154605781765490.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Arts J. editors. 2004. Assessing impact: handbook of EIA and SEA follow-up. London: Earthscan.

- NIPA. 2019. Towards a flexibility toolkit: supporting the delivery of better national infrastructure projects. London: NIPA Insights Project Board.

- Olympics Delivery Authority. 2011. Employment and skills update:Jan 2011. London: ODA.

- Pinto E, Morrison-Saunders A, Bond A, Reteif F. 2019 Jul. Distilling and applying criteria for best practice EIA follow-up. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 21(2):1950008. doi:10.1142/S146433321950008X.

- Planning Inspectorate. 2013. No. 648 INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING, The Hinkley Point C (Nuclear Generating Station) Order 2013 Made - - 18th March 2013; Coming into force - - 9th April 2013; plus s106 DCO documentation (Aug 2012). Bristol: Planning Inspectorate.

- Runhaar H, van Laerhoven F, Driessen P, Arts J. 2013. Environmental assessment in the Netherlands: is it effectively governing environmental protection? A discourse analysis. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 39:13–25. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2012.05.003.

- Somerset Councils. 2012. Local Impacts Report (LIR) appendix B2 accommodation and housing. Somerset: SCC, WSC and SDC.