ABSTRACT

Gaining a social licence to operate (SLO) is important to ensure a smooth-going metro project, yet few relevant studies exist. Using a small but eventful case from Nanjing, China, this study considers how a metro station construction project is assigned overlapping and fluid social licences by a local community and how these social licences interact with the project. The analytical framework is underpinned by two ‘continuum’ theories, one developed by Thomson and Boutilier and one by Dare et al. , and incorporates the perspective of the project life cycle and movements of social resistance. The results reveal that a uniform, community-level SLO diverged into multiple SLOs with different characteristics. However, the changes in the SLO were decoupled from the life cycle of the metro project, as work was not only halted due to opposition but also resumed amidst such opposition. The governmental interventions, manipulative resistance and unqualified impact assessments were the main driving forces in the dynamic procedure. Based on the results and analysis, we highlight several policy implications.

Introduction

Metro systems, an off-road mode of mass transportation, are increasingly appealing in metropolitan areas due to their numerous advantages, including the enhancement of traffic efficiency, the improvement of environmental quality, and the potential stimulation of social outcomes and policy planning (Garvin and Bosso Citation2008; Mottee et al. Citation2020). However, as with other types of social overhead capital (Goodman Citation1959), the metro can hardly offset its unplanned, negative, unfairly distributed social impacts on a local level through its total profits (Holden Citation2012; Nikfalazar et al. Citation2014). Thus, a ‘social licence to operate’ (SLO) is the premise for a metro project to be declared successful.

Simply put, the SLO is a metaphor that comprises ongoing operation acceptance or approval from the local community, broader civil society, and other stakeholders (Owen and Kemp Citation2013; Parsons and Moffat Citation2014; Lacey et al. Citation2016). Instead of being granted by civil, political, or legal authorities, SLOs are allocated by informal sanctions (Parsons and Moffat Citation2014). The SLO concept has become increasingly appreciated as an inherently dynamic process (Ehrnström-Fuentes and Kröger Citation2017). Even if a project has not been socially rejected, this does not equate to it having a solid SLO (Syn Citation2014). The evolving perceptions, opinions, and actions of social actors (Martinez and Franks Citation2014) fluidify the SLO, while the situational context also potentially matters (Hall et al. Citation2015; Gough et al. Citation2018). Some studies have drawn attention to the dynamic nature of SLOs in cases related to the mining industry (Boutilier Citation2014), the gas industry (Gough et al. Citation2018) and the establishment of universities (Chen et al. Citation2020). A limited body of studies has contextualised metro construction, which is actually in closer proximity to local communities than most projects. Moreover, investigations into dynamic SLOs are inclined to examine fixed groups but neglect that changes in the number of congenial grantors are also dynamic. Previous works have discussed SLO issuers’ dynamic responses in relation to external factors. However, only a few of them focus on how these issued social licences are dealt with, which is also an anthropic ‘external factor’.

To this end, we design a micro case study of Nanjing city in eastern China, where one of the fast-growing metro systems worldwide was built, to answer the following questions: How and why are the social licences for a metro station dynamically granted/withheld by locals? What are the responses to and outcomes of these social licences? The case of the ZB station of the S-line and one of its host communities is an interesting setting in which to observe dynamic SLOs for two chief reasons. The construction of this long-awaited station was at one time halted when its SLO was withdrawn and a demonstration was held, but surprisingly, the project was reinstated during a new round of protests. Moreover, local governments imposed powerful and targeted interventions among the host community members to encourage them to reissue the SLO.

The remainder of the study is structured as follows. After giving an overview of the literature on debates over and the modelling of the SLO concept, we present the background of our case study area and some relevant local knowledge. Then, we describe our research methods. In section five, the analysis is interspersed with the narrative results. Finally, we provide concluding remarks and implications.

Literature review and analytical framework

In the late 1990s, the SLO concept was mainly used in the forestry and mining industries, but this has since given way to cross-industrial practices and studies (Zhang et al. Citation2015). Opinions on the SLO concept are complex and varied. Supporters praise the incorporation of SLOs for putting social issues on the agendas of various industries (Demuijnck and Fasterling Citation2016); under SLOs, corporations need to provide benefits to affected communities by minimizing unintended effects, correcting predatory practices, encouraging citizen engagement, and extending stakeholder mechanisms (Parsons and Moffat Citation2014; Hall et al. Citation2015; Jijelava and Vanclay Citation2017). As a result, companies can earn a better reputation, create a responsible image for themselves, and strengthen their profitability (Esteves and Vanclay Citation2009). However, sceptics find the intangible, unwritten and contestable attributes of SLOs to result in vaguely defined responsibilities and imprecise obligations (Parsons and Moffat Citation2014). Additionally, some scholars argue that social licences are often granted in a transactional manner (Luke Citation2017) and have denounced SLOs as a trick to mask local opposition (Owen and Kemp Citation2013). Worse still, the SLO concept barely concerned a substantial shift in the discourse of power relations. Although communities are entitled to reject projects and act in self-defence, these actions are frequently resisted by stakeholders who endorse outside agents as community representatives (Parsons and Moffat Citation2014).

Thomson and Boutilier model

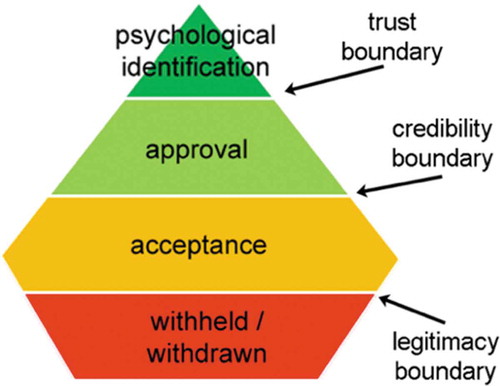

Emerging models and modifications thereof have been developed to support or refute the SLO concept (e.g., Prno Citation2013; Lacey et al. Citation2016; Bice et al. Citation2017). One of the most notable models is that of Thomson and Boutilier (Citation2011), whose core concepts have been used by both those who support the use of SLOs and those who oppose their use (Zhang et al. Citation2015; Jijelava and Vanclay Citation2017, Citation2018). Briefly, the step-like continuum of a SLO () can be separated into four levels of progressive approval, and with each step up the ladder, the socio-political risks diminish. When the SLO is at the ‘withdrawal’ level, the project is in danger of restricted access to essential resources and a lack of social support. When SLO is at the ‘acceptance’ level, which is the level at which a social license is typically granted, the social attitude is accepting but usually lies between ‘tacit consent’ and ‘not actively opposed’. If a company can establish its credibility, the social license tends to rise to the ‘approval’ level. Over time, if trust is established, the social licence can rise to the level of psychological identification (Boutilier and Thomson Citation2011). Jijelava and Vanclay (Citation2017) research is of a great reference value for the original model, as it particularly focuses on the three steps necessary for a fully-granted SLO: legitimacy, credibility and trust. This adapted version of Thomson and Boutilier’s model elaborates that ‘legitimacy’ is the minimum level of acceptance and is obtained via presenting justified procedures. The middle level – ‘credibility’ – is rooted in transparency and non-deception. The final criteria – ‘trust’ – requires more than just honesty; it requires acting in local interests and mutual consideration. Despite the relatively clear and concise interpretation of the SLO in Thomson and Boutilier’s model and its extension, this coherent continuum is sometimes inaccurately described with binarised wording to express whether a project does or does not hold a SLO (Parsons and Moffat Citation2014). In this yes-or-no presentation, ‘not possessing a SLO’ can be equated to the ‘withdrawal’ state, yet it is inaccurate to consider the levels beyond ‘compliance’ to equate to ‘holding a SLO’ because doing so disregards the upper levels of the SLO continuum, especially the highest ‘trust level’.

Figure 1. Thomson and Boutilier’s SLO model (Source: Thomson and Boutilier Citation2011)

Multiple social licences

The acquisition of a SLO requires conformity with social expectations and norms (Dare et al. Citation2014). However, differences in socio-spatial characteristics, stakeholder composition, and scope of influence make generating a unified social cognition difficult (Vanclay Citation2012). Thus, a range of social licences exist. Viewed in this way, the granting of SLOs in some scholarship has been erroneously considered as the granting of a specific SLO at a specific point in time. Dare et al. (Citation2014) assumed that SLOs should be conceptualised as a continuum that comprises overlapping social licences at the meso- and micro-levels rather than as a single licence representing an entire society. Dare et al.’s model does not contradict Thomson and Boutilier’s continuum because the former highlights multiple social licences within communities, regions or societies, while the latter focuses on the multiple possible levels within one SLO.

Actually, Dare’s continuum can be extended to smaller dimensions, because even the term ‘community’ has complex and non-homogenous meanings and cannot be understood as a singular concept (Hanna and Vanclay Citation2013). It has been demonstrated that while some groups in a community may tolerate, adapt, and even benefit from a project, other groups may be physically or emotionally harmed by it (Luke Citation2017). Given this, a SLO is sometimes more than a one-off permission granted by all community members. In other words, the divergent attitudes, expectations, and values within a community should be regarded as multiple social licences rather than a single, all-encompassing SLO.

To date, there is a small subset of literature on the utilities and interactions among multiple social licences. Usually, a valid SLO in one area will lose its effectiveness in other localities or on a larger scale (Prenzel and Vanclay Citation2014). However, established relationships and experiences make agreement among social licences (Hickey and Mohan Citation2004) at various scales possible. Micro-level consensus can potentially promote positive dialogue and relationships at larger scales (Dare et al. Citation2014). Likewise, a SLO from a community may also be shaped by that granted by a broader region or society.

SLO withdrawal

Most research is inclined to focus on whether the SLO concept promotes further collaboration (Boutilier Citation2014), while only some see the SLO as a ‘site of struggle’ (Parsons and Moffat Citation2014) and go on to explore the withdrawal of a SLO (Prno Citation2013; Luke Citation2017). Withdrawing a SLO is indeed a kind of ‘veto’ power and results from insufficient consultation, invalid referenda, and inappropriate benefits (Boutilier Citation2014). Although a SLO may be withdrawn through a judicial process, socio-political resistance movements are seemingly more common and explicit ways to achieve this. More concrete indicators of the withdrawal include community protests, boycotts, and consequent project delays (Martinez and Franks Citation2014; Chen et al. Citation2020). A more progressive view even holds that social resistance is an inescapable part of the SLO withdrawal process (Ehrnström-Fuentes and Kröger Citation2017).

The literature related to social resistance identifies that perceived procedural injustice is one of the most powerful driving forces of community resistance (Prno Citation2013). Contentious politics might result in the withdrawal of legal or authoritative permits or the closure of plans and operations (Luke Citation2017). However, social protests are frequently futile, as power plays a role: many corporations tend to downplay local grievances if more influential stakeholders, e.g., the state, sanction their continued operation. Such powerful support may conspire with the media to conceal objections to a project, thereby creating the illusion of ‘having achieved a SLO’ (Prno and Scott Slocombe Citation2012; Ehrnström-Fuentes and Kröger Citation2017). Therefore, to understand the withdrawal of a SLO, the external responses cannot be neglected. Such responses are mediated by complex institutional and socio-political milieus and have continuous mutual effects on the social resistance process.

Analytical framework

Based on the literature above, we construct the analytical framework for this study (). In terms of theories and modelling, we employ Thomson and Boutilier’s model (Citation2011) as a foundation because its definitions and assumptions for each level of the SLO are valuable for outlining SLO. The adaptive descriptions from Jijelava and Vanclay’s work (Citation2017) are also taken into consideration for more accurate identification. Dare et al.’s (Citation2014) proposition is adopted and combined with Thomson and Boutilier’s model, which enables SLO changes to be illustrated simultaneously. Additionally, in Dare et al.’s model, the key statements about the interaction of SLOs at different scales help us interpret the dynamic nature of SLOs.

To assess the SLO changes more comprehensively, we highlight, in addition to social perceptions, the social resistance actions that embody the withdrawal of a SLO, such as protest movements and judicial processes. Furthermore, the responses to social resistance are meaningful, as they are related to the self-adjustment and final utility of the SLO. The institutional and social-political milieus can function as supporting points to understand the hidden logics of social resistance and responses to it. The time axis is vital for examining SLOs from a dynamic perspective; thus, we introduce the perspective of the project life cycle to embed the changes in the SLO into ‘social time’ – composed of artificial events and nodes – instead of mechanical ‘natural time’ (Shi and Jiang Citation2019), which helps better clarify the context of SLO changes.

Background information of the S-line metro, ZB station and its host community

The metro line S

The fast-developing metro system in China has increased in length from approximately 140 km to over 6,900 km during the last 20 years (CAM Citation2020), with the majority of the growth occurring in the eastern region. Nanjing city is a large city and the capital of Jiangsu Province, which is China’s second wealthiest province and is located in eastern China. The GDP per capita of Nanjing exceeded 23,500 USD in 2019, nearly 2.3 times the national average. The length of the Nanjing Metro has surpassed that of any other city with the same economic capacity, reaching over 400 kilometres and ranking 5th in the world.

The S-line connects urban and suburban areas with 30 km of tracks and nearly 20 stations. A key event timeline of the S-line project is shown in , and some basic features of the S-line project are as follows.

32.3 km of underground tracks and 1.5 km of elevated tracks.

200,000 daily passengers on average.

Connection to nine other current or planned lines.

Advanced traction system, ‘Optonix’, from Alstom Metropolis.

Equipped with mobile payment for tickets at each station.

Table 1. Key event timeline of the S-line project

The construction of the S-line was a state-led project following a typical development pattern for metro infrastructure in China. Here, the ‘state’ encompasses not only the national authorities but also the central, provincial and local governments (Hofman et al. Citation2017). Moreover, state-owned banks and companies invested in, helped construct and now operate the S-line.

The developer behind the S-line project was a large state-owned enterprise named Nanjing Metro Group Co., Ltd. (NMC). The company has 5,000 employees and approximately 20 billion USD in gross assets. The NMC has its own administrative rankings and operates under the authority of the local branch of the State Asset Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC). This branch is both vertically controlled by the upper-level SASAC and horizontally supervised by local governments. As the absolute controlling shareholder of the NMC, the SASAC branch determines the fundamental principles of the NMC. Thus, the actors, interests and technologies of government coalesced around the S-line project weaken the conventional nexus between a community and corporation in such projects.

ZB station and its host community

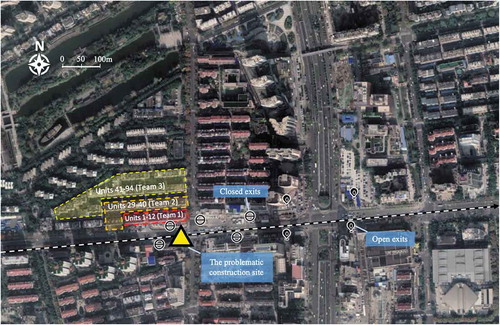

The S-line was postponed by almost one year primarily because of the delay in the construction of ZB station (). ZB station is a multifunctional terminal station on the S-line, and suggestions for its name, which refers to a former toponym for the area, were solicited from the public. The station is a four-story structure, and three of the floors are subterranean. While the ground floor and second subterranean level serve the S-line, the other two storeys are used for other traffic purposes. The subterranean part of the station is 520 metres long because in addition to the platform part, there is a space reserved for the subway trains to turn around. As for the above-ground architecture, there are nine exits distributed along an east-west avenue, four of which are currently in use (). A top-class hospital equipped with over 3600 beds stands to the east of ZB station. In the south, there is a large-scale commercial centre covering 280,000 square metres and a stadium established for international sports competitions with 3,000 spectator seats. Additionally, a heritage park sits at the northeast corner of ZB station.

Of the several neighbourhoods around ZB station, the oldest one, the Mid-Worker Community (an alias), stands to the north of the station. It was built in the 1990s and includes 20 buildings with 94 units and 1386 households. Most of the families in the Mid-Worker Community are grassroots employees from several large work units (Ma and Wu Citation2004), with high school or junior college educations and urban middle-class values. This gated community is a legacy of China’s unique housing policy during the planned-economy period, essentially functioning as a kind of welfare allocated to employees by the government and state-owned employers; thus, the property rights in the Mid-Worker Community originally belonged to the state. Residents were allowed only to live in the houses themselves, not to sublease or sell the property. Since China’s housing reform policy was issued in 1994, public-housing residents in the Mid-Worker Community have been allowed to purchase their property rights, after which they can freely rent or sell their property. Nevertheless, many residents still preferred to establish permanent residence there in light of the familiar social networks.

All buildings in the Mid-Worker Community are 7-storey brick, concrete, and non-pile structures. Because the area is a low flood plain, the soil beneath the community is ductile. Additionally, due to lax supervision, residents’ illegal structural modifications, such as the destruction of bearing walls and space expansions, have made the buildings even more unstable. The underground construction of the ZB station induced uneven settlement of foundations, and as a chain reaction, the structural risks eventually became architectural damage. Given the features of housing damages, the official documents divided affected residents into three teams, units 1–12 as Team 1, units 29–40 as Team 2, and units 41–94 as Team 3; and such a classification was also recognised by the residents during their interactions with the authorities. Specifically, units 1–12 which were closest to the problematic construction site (), suffered the earliest and most serious damage. These units were rated as Csu Level according to the Standard for Appraisal of Reliability of Civil Buildings GB50292-2015 (MOHURD Citation2015), which meant that parts of their load-bearing structures were too damaged to sustain normal use. Although units 29–40 also had the rating of Csu Level, they were damaged a few months later and slightly less than those of Team 1. The more peripheral apartments, units 41–94, which lay over 60 m away from the problematic construction spot, were the least damaged. Units 41–94 were exposed to damages last and rated as Bsu Level, which indicated that only a few elements of the buildings were deemed risky. All these different extents and timing of damage further influenced the characteristics of SLO changes.

Method

Our examination of this case employed mixed methods, including document analysis, in-depth interviews, site observation, and media data analysis. Chiefly, the use of comprehensive documents enabled us to gain a holistic understanding of the scenario and to establish a narrative framing. Specifically, public files, e.g., environmental impact assessment (EIA) and other industry reports, and non-public materials, e.g., SSRAreports and records from 70 internal meetings, contributed to our key results. The unparalleled value of these meeting records was in providing us with a lens through which to consider corporations and governmental roles. All non-public documents were collected through a consultant project by a provincial think tank in 2018 and were authorised for use in academic research on the condition of anonymity. In compliance with the rules, relevant details such as the name of the metro line, station, and community and the officers’ position titles were intentionally concealed.

Unstructured interviews with project staff were conducted by the lead author in July 2018 to understand the initiatives and opinions of the former on the situation. It is noteworthy that China’s field research relies heavily on team networks and cooperation with local officials. Thus, the interviewed staff were not chosen randomly but based on their participation in the consulting project and subsequent personal contact. Although the interviewees all knew that the interview would be used for academic research and consented to this. Given the tense context and relevant industry regulations, extensive written logs rather than recording devices were used to note the responses from municipal, district, and subdistrict governors (n = 3,3,4), representatives of the project developer (n = 2) and construction workers (n = 1). These three identities are separately marked with the characters G, D and W in the interview records.

Additionally, 23 households of the 920 affected households were randomly selected for interviews in August 2018 (marked with the characters R in the interview records). The ratio of the interviewees from Teams 1, 2 and 3 was 7:8:8. All respondents were aware of the teams and what team they were in. All of the interviews were semi-structured and face-to-face and lasted at least 30 minutes each. The interviews mainly focused on each group’s attitudes and actions, and the degree of permission granted to the S-line project at each stage of the project. Further, the psychological activity of the interviewees themselves and any content inconsistent with their group were also elicited. These questions resonate with the content presented in the lower half of the framework (), that is to grasp the holistic SLO changes from the perspective of project life cycle, and to analyse the withdrawal of SLO based on social perceptions and social resistance actions. As a large part of the interview needed to be answered according to memory, the interviewees were provided with relevant materials for recall. Some of the interviewees’ uncertain statements were not used in the analysis unless they were corroborated by information from the mass media, such as webpages and blogs. In August 2019, we followed up on 13 of these 23 households through the Internet or telephone, mainly to track the respondents’ current feelings and remaining problems. We also interviewed another 4 members of two non-involved communities along the S-line about this event to achieve insider-outsider comparisons. The observations regarding the residual traces of the incident (e.g., damage and repair) were conducted during these two field excursions.

Results and analysis

Planning stage

The initial SLO surpassed the credibility boundary

During the project planning period, 94.16% of respondents conveyed firm or conditional support, and 82.49% expressed either a willingness to adapt or an indifference to the possible impacts of the project (JPAES Citation2010). Such perception was also reflected in our interviews with residents from the Mid-Worker Community in 2018.

At that time, I felt highly confident and respected regarding this project when I heard that the location and name of the station could be adjusted based on public suggestions (Interview record: 01807R04).

We suggest that approval for the project largely emerged from the good reputation the NMC had built through work on similar projects, its established record of social responsibility (Hofman et al. Citation2017), and its role as the government’s agent. Moreover, the construction of the metro line was in the interest of the municipality and was welcomed by potential citizen users, as their strong desire for a subway line that reached their precinct weakened their suspicion of the project and bolstered its credibility.

However, misconduct in the production of impact assessments (IAs) sowed the seeds of the SLO withdrawal in the S-line project. Firstly, the strategic environmental assessment (SEA) was questionable. All SEA-related issues towards the S-line were analysed in a general ‘Environmental Impact Report (2004–2015) of Nanjing Urban Rapid Rail Transit Construction Adjustment Planning’ (DEEJS, Citation2010). Having examined this report, we hold that the problem was not the lack of formal or separate SEA document (Fischer Citation1999), but that this general report narrowed the SEA down to the metro plan formulation while disconnected the SEA from the policy and programme making (Malvestio et al. Citation2017). It is a common fault in China’s SEA praxis to merely focus the ‘plan’ among PPPs (policy, plan, programme) (Li et al. Citation2018), contributing to the deficiency of handling capacity towards metro-induced impacts. Besides, in terms of assessment forms, we found six main environmental impacts, including air, soil, landscape, heritage, noise and vibration, and water and electricity were addressed in the SEA, whilst socio-economic issues were rarely mentioned and ‘housing impacts’ were even not assessed at all.

Secondly, there existed problems in the EIA (JPAES Citation2010) of the S-line project, mainly reflected on three aspects. (1) The EIA of S-line was routinely guided by the SEA and assessed little about the socio-economic impacts (accounted for 1.8% of the EIA’s full text), which also led the public consideration on environmental risks largely overwhelmed the the socio-economic impacts; (2) The EIA’s public comment period lasting merely ten days significantly restricted the opportunity for citizens to express their thoughts; (3) The community participation during the EIA survey was at low level, which can be seen from that the online information page of the project that would affect 200,000 passengers daily, received a disproportionate number of views (2,306 times) and a small amount of feedback (219 times).

The third problem was that the specialised assessment (CRSC Citation2013) about the project’s social impact – which usually takes the form of an SSRA in China (Peng et al. Citation2019) – was absent from the planning process of the S-line project. This pre-assessment of the S-line was belatedly completed after the project had commenced and was never disclosed to the public. However, while this practice went against the custom of soliciting ‘free, prior, informed consent (FPIC)’ (Hanna and Vanclay Citation2013), it was not illegal due to the scarcity of regulations on this matter before 2016 (Peng et al. Citation2019). Distinct from the social impact assessment (SIA), the SSRA focuses more on controlling social resistance (Peng et al. Citation2019) than on comprehensively understanding both the negative and positive social impacts of a project (Vanclay Citation2003; Vanclay et al. Citation2015; Mottee and Howitt Citation2018). The SSRA mainly caters to the concerns of the government and one-sidedly treats any negative changes in SLO as ‘risks’; this focus primarily derives from the Chinese political mantra of ‘stability above all else’.

Although the SSRA report does not directly impact the SLO, it is crucial and maybe the last step in understanding SLOs and their potential changes. Therefore, the quality of the deferred SSRA report for the S-line is examined below. First, the SSRA was undertaken by a state-owned design institute. Thus, the narrative of the SSRA report revealed the close involvement of the government. For instance, the acknowledgements stated, ‘We appreciate the government, grassroots administration, and related functional departments for their support of the SSRA report’, but there was no mention of any community members – the main actors involved in granting SLO. This was essentially because the survey to collect data for the SSRA was administered by local authorities, which led to the report having a biased scope and outcomes. Second, the rigid structure of the SSRA report was filled by many meaningless statements and failed to describe the local impacts of the project and development plans for the surrounding communities (Vanclay Citation2003). As a result, the SSRA found no ‘high’ level of social risk, and only the ‘moderate’ or ‘low’ risks were detailed in the report, as seen below ().

Table 2. The social risks of the S-line project anticipated in the SSRA report

The SSRA proposed that through the following schemes, the six ‘moderate’ risks (in ) might be reduced to ‘low’.

Standardise the process of land acquisition and demolition; improve the quality of bids and level of safety supervision.

Set up a special operations team across multiple departments; attach importance to the relationship with the mainstream media.

Obviously, these two strategies both required powerful government interventions because it would have been impractical for enterprises to mobilise separate departments, e.g., land, environment, fire protection, traffic, and public security sectors, into a temporary group unless they could rely on the support of upper-level government. Moreover, the ‘relationship with the mainstream media’ was deviously utilised to restrict negative information about the project, thereby maintaining the project’s social acceptability. Forcing the media to function as gatekeepers of the public voice and cover up local grievances would heavily depend on the collusion with local government. Ultimately, the risk assessment and the ‘hollow’ commitments that followed led to a smooth approval process but turned out to be over-optimistic. The miscalculations resulted from the imperfect information gathered under government supervision and the use of a one-time evaluation mechanism without any follow-up monitoring or social communication (Marshall et al. Citation2005). Briefly, the analysis in this paragraph suggests that, as with the unqualified EIA, the hysteria, generalization, over-optimism, and political dominance of the SSRA foreshadowed the eventful SLO changes in this study.

Construction stage

Social credibility began to decrease due to project-induced housing damage

Beginning in late 2013, the machinery vibrations cracked the walls of apartments in the Mid-Worker Community, sparking complaints from residents. However, the SLO did not yet downgrade from the acceptance level.

NMC conducted field investigations and promised to take appropriate measures in a timely manner. Thus, we deemed the problem was not all that serious and never thought about stopping the metro construction at that time. (Interview record: 01808R13)

At that time, the following decisions (excerpted from meeting minutes between October 2013 and January 2014) were made by developers under the pressure of a time-limited construction schedule:

Report to the district government and related departments;

Continue the project according to the original plan;

Carry out an assessment on the safety of the community, strengthen the monitoring of community activities, strive to avoid evacuating residents;

Increase emergency measures.

These reactions show the sensitivity of the NMC to social risks. However, the institutional background restricted the implementation of feasible countermeasures. The NMC could only enact technical solutions, but decision-making in public affairs cannot bypass the government, and the interdepartmental transaction costs delayed the responsiveness to the community. Undeniably, the monitoring of community opinions was crucial to understanding further changes of SLO, but such monitoring was passive and concerned only legitimacy issues.

Then, a series of social resistance efforts resulted in the withdrawal of the SLO

In November 2014, the S-line project was regarded as ‘a jerry-built project’ that lacked procedural justice and social fairness (Lacey et al. Citation2016) due to the damage to and subsequent deterioration of houses, such as water leakage and structural instability. The resulting scepticism and perceived injustice swiftly transformed into a powerful driver of protest (Prno Citation2013; Martinez and Franks Citation2014). A temporary resident group formed among Team 1 residents after November 2014.

They withdrew the previously granted SLO and resorted to radical forms of protest, e.g., blocking the construction site, throwing debris, donning red ribbons, and marching while carrying signs (Interview records: 01807W01)

The construction of ZB station was consequently forced to a halt. The violent boycotts accordingly softened to ‘rightful resistance’ (O’Brien and Li Citation2006). For instance, Team 1 residents held small-scale sit-ins at provincial and municipal government buildings, held rallies in the lobby of the NMC headquarters, and petitioned to the xinfang (literally meaning letters and calls)Footnote1 departments. In light of these movements, an increasing number of joint ACC-CPC meetings were held to accelerate the handling of incidents. One outcome of these meetings was that the house appraisal report, which had been requested 11 months before, came out a mere two weeks after the SLO withdrawal. As the report acknowledged that the metro project had caused damage to the houses, residents from Team 1 reduced their protests.

Not long after, a large new campaign regarding economic losses began

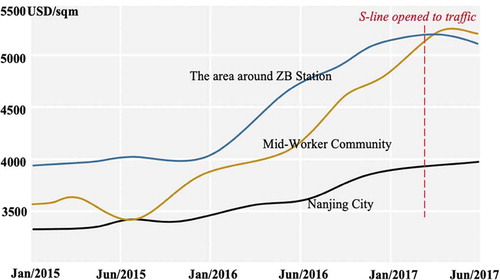

The key factor in this campaign was that the damage to houses in the Mid-Worker Community made them less attractive in the second-hand real estate market. When housing prices generally rose in the overall market in the second quarter of 2015, the prices plummeted in the Mid-Worker Community (). Given the massive protests, nine institutions consequently listed more detailed solutions. Specifically, these institutions included the NMC, construction contractor, subdistrict office, district government, district housing expropriation office, municipal commission of housing and urban-rural development, municipal audit bureau, district security company, and municipal housing safety appraisal office. The core contents of this scheme issued in May 2015 were as follows (excerpted from meeting minutes).

Team 1 residents could sell their houses to the NMC and resettle permanently; the benchmark price would be notarised; the displacement subsidy for each resettled household was 7 USD/sqm.

The residents of Team 1 could also choose temporary displacement and then return to their original residences after the buildings were reinforced. They would be compensated with 260 USD/sqm for the additional reinforcement undertaken by themselves, as well as two times (move out and move in) the displacement subsidy as the above standard.

The NMC would compensate the costs of the transitions according to the municipal policies, which was 7.5 USD/sqm/month for each family.

All Team 1 residents were asked to decide which action to pursue before the deadline, and there was an early-bird bonus.

Within three months after the plan was shared, all Team 1 residents (140 households) had signed the agreements. Among them, 12 households were temporarily relocated, 44 families sold their houses to the government, and the rest chose to repair the houses on their own (excerpted from meeting minutes in Sep 2015). The SLO of Team 1 rebounded to the acceptance level, and the construction on the ZB station was resumed.

Team 1’s reacceptance of the project was mainly driven by economic legitimacy (Thomson and Boutilier Citation2011), but the project’s social-political legitimacy was still inadequate. First of all, the compensation for residents was not a natural result of laws and institutions but of a compromise process engaged in by the government to maintain project and social stability. To obtain such compensation, residents withdrew the SLO and generated social resistance, which they did at the expense of normal life functioning and well-being. Moreover, although the resettlement plan was in accordance with the local regulations (the transition standard in Nanjing city was higher than the national standard), provided several options for residents, and offered repurchase at the market price, these disposable monetary-based forms of compensationFootnote2 rarely covered the potential social and psychological impacts during the transition and post-resettlement stages.

In addition to Team 1, more teams in the community then started to withdraw their SLO

One important reason for this, beyond the damage their residences were suffering, was that offering compensation for only a portion of residents undermined the fabric and solidarity of the community (Sing Citation2015). In the fourth quarter of 2015, residents from Team 2, whose houses were affected slightly less than those of Team 1, protested against the project’s resumption and fought for similar housing compensation. Collective xinfang events with over 50 petitioners were launched several times. Although acting on similar impulses as the residents of Team 1, the residents of Team 2 did not act in concert with the former. Interestingly, they took the unusual path of petitioning separately from Team 1, as they found that their arguments were at a disadvantage compared with those of Team 1 (meeting minutes from September 2015 to December 2015). This reflects that in China’s context, SLOs can hardly be valued without providing a strategic design for the endeavour, unless the situation is an absolute crisis of survival.

The challenge the NMC faced was that the project had a metropolitan goal approved by the public but the SLO was being withdrawn at the micro-level. Facing tension between regional-level and community-level SLOs (Dare et al. Citation2014), the NMC’s loss aversion surrounding greater expenditure almost overshadowed the concern for the local impacts of the project. Therefore, the NMC firmly stated the following in its report to the district government (excerpted from meeting minutes in December 2015):

A second stoppage is unacceptable; the project efficiency needs to be further improved.

In-depth plans for project delays need to be prepared.

After the NMC and the government reached an agreement that construction would not be stopped, community concerns were addressed further. The NMC added monitoring panels, publicised construction details to enhance transparency, and arranged for specialised personnel to maintain a dialogue with groups of ‘ten to hundreds of demonstrators per day’, and ‘some dialogues even lasted until the early morning of next day’ (Interview records: 01807D02). However, despite these efforts, the NMC failed to reach an amicable settlement with the community, and its efforts even complicated matters. At this point, the government recognised that the community had embedded ‘profit-making expectations’ into their legitimacy requirements (Interview records: 01807D01). Then, the municipal government and its subordinates formally took over responsibility for the project, while the NMC was relegated to monitoring construction and providing financial support. Ultimately, in November 2016, the government and the vast majority of Team 2 members reached an agreement that they would receive similar compensation as Team 1, even though the degree of damage their homes sustained was slightly less than that sustained by the homes of Team 1. A total of 224 households from Team 2 were resettled; 59 of them were impermanently relocated, while the remaining 165 families sold their damaged houses to the government. At this point, it could be determined that Team 2 reissued their SLO at the acceptance level.

A continuously increasing number of residents attempted to claim compensation

Team 3 residents, whose residences suffered damage to their accessory structures (e.g. balconies), also joined the protests and requested housing compensation almost at the same time as Team 2. On account of their losses being more minor, the Team 3 residents strategically united with those of Team 2 to resist the project, as this tactic could grant them additional influence (Dare et al. Citation2014) and create an advantageous negotiation environment. Under such circumstances, the NMC promised a preliminary restoration of the residences first and a thorough repair after the completion of the S-line. However, this proposal met with strong opposition from Team 3 residents.

At that time, we did not think the matter could rest there … Although the situation then was not serious, who knows whether the damage would be aggravated … Most of us insisted that if the compensation scheme could not meet our requirements, we would hinder the construction again … As you know, many of our Team 3 residents were retired employees, and we had plenty of time to petition. (Interview records: 01808R19)

It was indeed reasonable for Team 3 to withhold their SLO, even if their residences suffered only slight metro-induced damage. However, based on official documents and interviews with members of Team 3, it appears that Team 3 irrationally and wrongfully treated the SLO as a profit-making tool and ungratefully made extravagant claims. Under the premise of NMC’s commitment to repair damages, the residents of Team 3 neither considered the extra compensation based on repair nor accepted the disposal according to the actual situation but instead proposed the undifferentiated buy-back of all the damaged houses of Team 3 (excerpted from meeting minutes in Oct 2016). Another fact was that, when Team 3 asked for repurchase more strongly in late 2016, it was the period of most rapid rise in housing prices for this community ().

The chaos Team 3 created provided a pretext for governmental intervention because all levels of the Chinese government seemed to agree that taking tough measures against unreasonable persons was the best response. Given the importunity of this resistance, the government broke down in further negotiations and unequivocally announced that ‘the housing problems of Team 3 residences were not due to the metro’s construction because they were 60 m away from ZB station’, and ‘all of the housing damage to Team 3 buildings was to be approached according to the general procedure, and the district government was responsible for all dissent’ (excerpted from meeting minutes in December 2016). This tough attitude attracted opposition, however, as the interviewees of Team 3 said,

After nearly half a year, with the damaged buildings repaired, the objections subsided in late 2017. Only a few radical residents were still fighting, but most community members like us were not agitated by them anymore because we all know that as long as the government has taken strong measures, it is vain to continue resistance. (interview record: 01808R22)

Using such arbitrary approaches to address the excessive actions of Team 3 was controversial. The policies did cause Team 3’s plan to abuse the SLO to fail, but some deserved compensation was not appropriately realised. In other words, the government and developers had greater dominance and flexibility in such matters, as reflected in the fact that Team 1 and 2 were fully compensated after stiff resistance. One key reason is that there are still no clear legal provisions in China to stipulate the responsibility of metro construction for damage to surrounding buildings (He Citation2016).

Operation stage

The S-line was opened to traffic without full acceptance by the locality

After the metro line had been in operation for the first half of 2017, although the collective boycotts had long ago subsided, there were still a small number of residents who did not change their decision to withdraw the SLO.

There were still over 30 unresolved indictments against the project. They were filed by a few residents who were dissatisfied with the previous solutions from Team 2 and 3. (Interview record: 01807G01)

However, the efficacy of these indictments was limited to a certain scope and did not impede the project’s continuous operation. Even other communities did not give external support to these opponents from the Mid-Worker Community. There is other evidence of the supportive attitude toward the metro project among the public: two respondents who lived near another station on the S-line station deemed that,

In 2015, we knew there was something wrong in the Mid-Worker Community … Fixing the dilapidated houses is reasonable, but it is irrational to demand to exchange houses or to hinder the metro’s opening unless there are life-threatening issues … We believe that the timeline for opening metro should not be changed because numerous people need this line. (Interview record: 01908R04)

This response reflects the ethical norms at play, including both ‘sacrificing individual interests for the collective’, as advocated by the Communist Party of China, and ‘home-country isomorphism’, which is a longstanding tradition in Chinese culture. Under such norms, the micro-level local communities’ non-fatal losses were inappropriately considered ‘inevitable’ and ‘acceptable’ because of the benefits the project provided to the broader region.

Our tracking fieldwork found that as of 2019, none of the respondents held objections to this subway project; all of them acknowledged the increased commuting convenience and housing prices of the area. Only a small number of complaining voices appeared on the Internet, and the appeals for further housing reinforcement have superseded the queries about the metro’s legitimacy. However, the following details demonstrate that a reduction in a project’s credibility level tends to be irreversible. The EIA of the S-line extension project was modified two times to be accepted by local society, in sharp contrast to the one-off acceptance of that for the original S-line project. In other words, mistrust towards a project attracts more public attention and enhances risk awareness among the public. This verifies another existing theory: having a history of negative impacts will result in feelings such as anxiety, hesitation, and rejection and thus affect the development of similar projects in the future (Vanclay et al. Citation2015).

Results summary

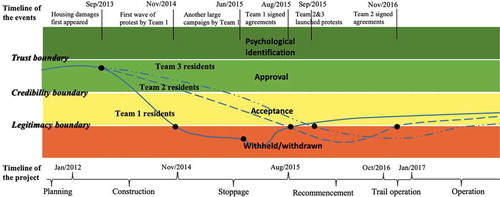

This section provides an overview of how the social licences from the Mid-Worker Community changed throughout the S-line project’s life cycle. As SLO is a relatively qualitative concept and difficult to quantify (Parsons and Moffat Citation2014), we draw the relative position of the curves () below based on the nodes, trends, sequence and intensity of several events to roughly sketch the vignettes (Thomson Citation2018) of our case.

Initially, the hierarchy of project’s SLO surpassed the credibility boundary in the Mid-Worker Community. However, due to unexpected failures in the construction stage, the SLO of Team 1 gradually fell below the legitimacy threshold. Given this, the project was forced to halt. When the protesters from Team 1 again accepted the project, Teams 2 & 3 successively launched new waves of resistance and issued multiple SLOs with distinguished levels. The project made concessions to the social licences allocated by Teams 1 & 2, while the SLO retracted by Team 3 exerted little effect on the project.

Discussion and conclusions

Through a case study, this paper has analysed the halted and recommenced construction of a metro station on the basis of the dynamic SLOs from the host community, meanwhile, kinds of problems related to the nature of SLO have been discussed. Overall, the uniform host Mid-Worker Community was ‘divided’ into three teams and issued SLOs in different manifestations, including elite-led protests, contract signing and the acquiescence based on community consensus. The granted SLOs commonly varied from quite positive to negative due to the effects of the construction but ultimately rebounded to a passable level. This trend generally concurs with the dynamic process revealed by previous studies (Chen et al. Citation2020) which suggest that SLO originates at a relatively high level but inevitably decreases with the progress of the project; but contradicts the findings of other research (Wolsink Citation2007; Mottee et al. Citation2020) which maintain that the level of SLO may gradually accumulate, increasing from a low to a high level. We suggest that the dynamics of SLOs are definite, but how SLOs operate is irregular (Thomson Citation2018) due to complicated factors. Additionally, we maintain that there is no universal SLO that can properly incorporate the different views of multiple groups, and thus, the overlap of multiple SLOs is normal in practice. Diverse social licences are variable and may split or merge together, which also reflects the dynamic nature of SLO.

Government intervention affected the changes in the SLOs, pushing some community groups to re-grant positive social licences and leading to some SLO changes not necessarily related to the project’s life cycle (Ehrnström-Fuentes and Kröger Citation2017). Specifically, we could barely identify government mediation efforts when only corporate routines were disturbed by the demotion of SLOs, e.g., in the beginning, staff attention was increased and additional costs incurred, whereas when significant social impacts occurred, e.g., protests and project delays (Hanna et al. Citation2016), the whole event was taken over by the local government. Despite the instability of the project’s local SLO, the project went ahead because governments tend to give more weight to broader regional SLO (Boutilier Citation2014) when it is at odds with community-level SLO. Moreover, the government’s actions determined the performance and efficiency of the social licences from the community, and only the SLO recognised by the government was considered valid. This pattern of limiting the community’s power is a product of the ‘government-led society’ and ‘government-supervised media’ in China. Nevertheless, similar issues arise in other countries, where it has been declared that elaborately ‘managed’ communities can hardly impede projects (Ehrnström-Fuentes and Kröger Citation2017; Luke Citation2017), and this phenomenon seems diametrically opposed to the initial intention of the SLO concept. Given this, there are two possibilities for improving SLO functioning. One is to inherently reform the institutional management of social issues, i.e., to encourage enterprises to deal with the community in accordance with laws and regulations rather than relying on government intervention, thus leading to more balanced corporate-community relations. Another route for improvement is to allow local governments to properly mediate SLO, but only when social anomie occurs. Regardless of which method is adopted, providing channels for NGOs and non-state media to supervise the collusion between enterprises and government is needed.

While this article explores a case involving protests in China, it nonetheless speaks to the protest-driven withdrawal of SLO more broadly. It does so by outlining a fluid series of community resistance efforts and the inherent tactics used. A portion of affected people issued tacit SLO and did not engage in the protests. Others had no tolerance for the nuisance of the project and the ways it impaired their daily lives and thus conducted rightful demonstrations to protest the legitimacy of the project. However, some of those affected intentionally exaggerated their minor losses and potentially abused their SLO as a speculative activity. Essentially, resistance to unjustifiable treatment should be considered part of a civil rights movement, yet the nature of resistance has changed in practice. When strategic organizations, undue expectations, extortion (Boutilier Citation2014), and ‘community bullies’ arise, captiousness and illegal violence threaten the legitimacy of protests. Those noisy groups are not always more eligible to withdraw their SLO than the groups who do not hold protests. Such illegitimate protests to withdraw SLO are a miniature of the drawbacks of SLO’s informal nature. Therefore, in addition to critically inspecting the notion of SLO, it is also necessary to regulate the withdrawal of SLO, which not only requires technical improvements in assessment and monitoring but also requires rules and institutions to normalisze the responsibilities of each stakeholder.

The unexpected changes in the SLO were related to the IAs with substandard evaluation methods, procedures and systems. Thus, the following suggestions to IAs are proposed. Overall, regardless of whether assessment tools are used, it is necessary to restrain excessive political attributes and to maintain technocratic neutral. Another mission is to accelerate the cultivation of practitioners and supervisors to meet the huge demand for impact assessment, as many major projects being carried out in the emerging economies have reduced the supply of available assessment teams. Specifically, SEAs should give substantive focus on social-economic issues and develop treatments that are implementable in relevant policies, plans and programmes. Local practice of EIA would need more rigorous and clearer prescriptions, because although referring to a mature evaluation system is helpful (Peng et al. Citation2019), it is not easy to implement each step well. Also, to adapt to the complex, cumulative, and interactional social milieu (Arts and Morrison-Saunders Citation2012), SIA and its extensions like SSRA should be conducted through a phased, group-based and localised way (Vanclay Citation2004) and the phenomenon that the inferential knowledge trumps the empirical surveys should be avoided.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Xinfang is a form of public expression in China (1950-now) entrenched in social governance frameworks. Xinfang departments exist at all government levels to receive petitioners and hear about their dissatisfaction.

2. The rescue and repair of dangerous buildings was carried out according to the Nanjing City Housing Safety Management Regulations (SCJPC Citation2017), and the compensation measures were compliant with the State Compensation Law of the People’s Republic of China (NPCSC Citation2013).

References

- Arts J, Morrison-Saunders A. 2012. Assessing Impact: handbook of EIA and SEA Follow-up. London: Routledge.

- Bice S, Brueckner M, Pforr C. 2017. Putting social license to operate on the map: A social, actuarial and political risk and licensing model (SAP Model). Resour Policy. 53:46–55. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.05.011.

- Boutilier RG. 2014. Frequently asked questions about the social licence to operate. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 32(4):263–272. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.941141.

- Boutilier RG, Thomson I. 2011. Modelling and measuring the social license to operate: fruits of a dialogue between theory and practice. Soc Licence. 1:1–10.

- Chen C, Vanclay F, Dijk TV. 2020. How a new university campus affected people in three villages: the dynamic nature of social licence to operate. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 1–9. doi:10.1080/14615517.2020.1769403

- China Association of Metros (CAM). 2020. Overview of Urban Rail Transit Projects in Mainland China (in Chinese). [accessed 2020 Jul 10]. https://www.camet.org.cn.

- China Railway Siyuan Survey and Design Group Co., Ltd., (CRSC). 2013. Social Stability Risk Assessment: phase 1 Project of Metro Line (in Chinese, accessed 2018 Jul 20)

- Dare M (Lain), Schirmer J, Vanclay F. 2014. Community engagement and social licence to operate. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 32:188–197. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.927108

- Demuijnck G, Fasterling B. 2016. The Social License to Operate. J Bus Ethics. 136:675–685. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2976-7

- Department of Ecology and Environment of Jiangsu Province (DEEJS). 2010. Environmental Impact Report (2004–2015) of Nanjing Urban Rapid Rail Transit Construction Adjustment Planning (in Chinese). [accessed 2020 Oct 26]. http://hbt.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2010/5/10/art_1572_3936186.html.

- Ehrnström-Fuentes M, Kröger M. 2017. In the shadows of social licence to operate: untold investment grievances in latin America. J Clean Prod. 141:346–358. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.112

- Esteves AM, Vanclay F. 2009. Social Development Needs Analysis as a tool for SIA to guide corporate-community investment: applications in the minerals industry. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29:137–145. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2008.08.004

- Fischer T. 1999. Comparative Analysis of Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts in SEA for Transport Related Policies, Plans and Programs. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 19:275–303. doi:10.1016/S0195-9255(99)00008-6

- Garvin MJ, Bosso D. 2008. Assessing the Effectiveness of Infrastructure Public—Private Partnership Programs and Projects. Public Works Manage Policy. 13:162–178. doi:10.1177/1087724X08323845

- Goodman B. 1959. The Strategy of Economic Development, Albert O. Hirschman. Am J Agric Econ. 41:p. 468–469. doi:10.2307/1235188

- Gough C, Cunningham R, Mander S. 2018. Understanding key elements in establishing a social license for CCS: an empirical approach. Int J Greenhouse Gas Control. 68:16–25. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2017.11.003

- Hall N, Lacey J, Carr-Cornish S, Dowd A-M. 2015. Social licence to operate: understanding how a concept has been translated into practice in energy industries. J Clean Prod. 86:301–310. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.08.020

- Hanna P, Vanclay F. 2013. Human rights, Indigenous peoples and the concept of Free, Prior and Informed Consent. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 31:146–157. doi:10.1080/14615517.2013.780373

- Hanna P, Vanclay F, Langdon EJ, Arts J. 2016. Conceptualizing social protest and the significance of protest actions to large projects. Extr Ind Soc. 3:217–239. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2015.10.006

- He X 2016. Legal search report on liability for damage to surrounding buildings caused by subway construction (in Chinese). [accessed 2020 Sept 26]. http://www.rhrlawyer.com/index.php?c=content&a=show&id=849.

- Hickey S, Mohan G. 2004. Participation—From Tyranny to transformation?: Exploring new approaches to participation in development. London: Zed Books; p. 10–16.

- Hofman PS, Moon J, Wu B. 2017. Corporate Social Responsibility Under Authoritarian Capitalism: dynamics and Prospects of State-Led and Society-Driven CSR. Bus Soc. 56:651–671. doi:10.1177/0007650315623014

- Holden M. 2012. Urban Policy Engagement with Social Sustainability in Metro Vancouver. Urban Stud. 49:527–542. doi:10.1177/0042098011403015

- Jiangsu Provincial Academy of Environmental Science (JPAES). 2010. Environmental impact Assessment: phase 1 Project of metro line S. (in Chinese, accessed 2018 Jul 18)

- Jijelava D, Vanclay F. 2017. Legitimacy, credibility and trust as the key components of a social licence to operate: an analysis of BP’s projects in Georgia. J Clean Prod. 140:1077–1086. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.070

- Jijelava D, Vanclay F. 2018. How a large project was halted by the lack of a social Licence to operate: testing the applicability of the Thomson and Boutilier model. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 73:31–40. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2018.07.001

- Lacey J, Edwards P, Lamont J. 2016. Social licence as social contract: procedural fairness and forest agreement-making in Australia. Forestry. 89:489–499. doi:10.1093/forestry/cpw027

- Li Z, Bao C, Shen B. 2018. Application of Tiering Assessment in German Spatial Planning and Its Enlightenment on Chinese SEA System. Urban Plann Int. 33(5):132–137. (in Chinese).

- Luke H. 2017. Social resistance to coal seam gas development in the Northern Rivers region of Eastern Australia: proposing a diamond model of social license to operate. Land Use Policy. 69:266–280. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.006

- Ma LJC, Wu F. 2004. Restructuring the Chinese City: changing Society, Economy and Space. London: Routledge; p. 1–18.

- Malvestio AC, Fischer T, Montaño M. 2017. The Consideration of Environmental and Social Issues in Transport Policy, Plan and Programme Making in Brazil: A Systems Analysis. J Clean Prod. 179:674–689. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.152

- Marshall R, Arts J, Morrison-Saunders A. 2005. International principles for best practice EIA follow-up. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 23:175–181. doi:10.3152/147154605781765490

- Martinez C, Franks DM. 2014. Does mining company-sponsored community development influence social licence to operate? Evidence from private and state-owned companies in Chile. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 32:294–303. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.929783

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’ s Republic of China (MOHURD). 2015. Standard for appraisal of reliability of civil buildings: GB50292-2015. [accessed 2020 Sept 19]. http://www.jianbiaoku.com/webarbs/book/320/2395618.shtml.

- Mottee LK, Arts J, Vanclay F, Miller F, Howitt R. 2020. Metro infrastructure planning in Amsterdam: how are social issues managed in the absence of environmental and social impact assessment? Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 38:320–335. doi:10.1080/14615517.2020.1741918

- Mottee LK, Howitt R. 2018. Follow-up and social impact assessment (SIA) in urban transport-infrastructure projects: insights from the Parramatta rail link. Aus Planner. 55:46–56. doi:10.1080/07293682.2018.1506496

- National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC). 2013. State Compensation Law of the People’s Republic of China. [accessed 2020 Oct 3]. https://www.cecc.gov/resources/legal-provisions/state-compensation-law-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china-amended.

- Nikfalazar S, Amiri M, Khorshidi HA. 2014. Social impact assessment on metro development with a case study in Eastern District of Tehran. Int J Soc Syst Sci. 6:245–263. doi:10.1504/IJSSS.2014.065227

- O’Brien KJ, Li L. 2006. Rightful Resistance in Rural China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Owen JR, Kemp D. 2013. Social licence and mining: A critical perspective. Resour Policy. 38:29–35. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.06.016

- Parsons R, Moffat K. 2014. Constructing the Meaning of Social Licence. Soc Epistemol. 28:340–363. doi:10.1080/02691728.2014.922645

- Peng S, Shi G, Zhang R. 2019. Social stability risk assessment: status, trends and prospects – a case of land acquisition and resettlement in the hydropower sector. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 1–17. doi:10.1080/14615517.2019.1706386

- Prenzel PV, Vanclay F. 2014. How social impact assessment can contribute to conflict management. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 45:30–37. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2013.11.003

- Prno J. 2013. An analysis of factors leading to the establishment of a social licence to operate in the mining industry. Resour Policy. 38:577–590. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2013.09.010

- Prno J, Scott Slocombe D. 2012. Exploring the origins of ‘social license to operate’ in the mining sector: perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resour Policy. 37:346–357. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.04.002

- Shi G, Jiang T. 2019. A Primary Study of Engineering Sociology from the Perspective of Whole Life Cycle: A Case for Analyses of the Construction Project. J Dialectics Nat. 41(9):93–99.(in Chinese).

- Sing J. 2015. Regulating mining resource investments towards sustainable development: the case of Papua New Guinea. Extr Ind Soc. 2:124–131. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2014.11.003

- Syn J. 2014. The Social License: empowering Communities and a Better Way Forward. Soc Epistemol. 28:318–339. doi:10.1080/02691728.2014.922640

- The standing committee of Jiangsu Provincial People’s congress (SCJPC). 2017. Nanjing City Housing Safety Management Regulations (in Chinese). [accessed 2020 Oct 3]. http://www.jsrd.gov.cn/zyfb/dffg1/201707/t20170727_468935.shtml.

- Thomson I, Boutilier R. 2011. The social license to operate. In: Darling P, editor. SME Mining Engineering Handbook. 3rd ed. Society for Mining Metallurgy and Exploration: Littleton Co; p. 1779–1796.

- Thomson I 2018. Social License: metrics for measuring social acceptance in the maritime industry. Presentation in Greentech 2018, Vancouver (BC), (accessed 2020 May 15)

- Vanclay F. 2003. International Principles For Social Impact Assessment. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 21:5–12. doi:10.3152/147154603781766491

- Vanclay F. 2004. The triple bottom line and impact assessment: how do TBL, EIA, SIA, SEA and EMS relate to each other?J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 6(3): p. 265–288. doi:10.1142/S1464333204001729

- Vanclay F. 2012. The potential application of social impact assessment in integrated coastal zone management. Ocean Coastal Manage Special Issue Wadden Sea Reg. 68:149–156. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.05.016

- Vanclay F, Esteves AM, Aucamp I, Franks D 2015. Social impact assessment: guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects. Fargo ND: International Association for Impact Assessment. [accessed 2020 Jun 5]. http://www.iaia.org/uploads/pdf/SIA_Guidance_Document_IAIA.pdf.

- Wolsink M. 2007. Wind power implementation: the nature of public attitudes: equity and fairness instead of ‘backyard motives. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 11:1188–1207. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2005.10.005

- Zhang A, Moffat K, Lacey J, Wang J, González R, Uribe K, Cui L, Dai Y. 2015. Understanding the social licence to operate of mining at the national scale: a comparative study of Australia, China and Chile. J Clean Prod. 108:1063–1072. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.097