ABSTRACT

In this paper, the authors reflect on public participation (PP) in environmental impact assessment (EIA) processes in Malawi, where EIA is implemented as Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). Who is invited and who is actively contributing to PP meetings is explored. In this context, 12 ESIAs are examined, six from rural and six from urban areas. While PP principles ask for a balanced approach towards the inclusion of both interested and affected individuals and bodies, in the 12 projects, participants were mostly development and planning experts in urban projects and traditional leaders (chiefs) in rural projects. People without societal positions that were directly affected by developments only represented 15% of those being present in PP meetings. Based on these findings, the authors suggest that PP policy needs to be improved and enforced in order to allow ordinary people potentially directly affected by development to be better represented.

Introduction

Public participation (PP) is an important ingredient of inclusive decision-making. PP is also a key aspect of environmental impact assessment (EIA) (Fischer Citation2007; Morgan et al. Citation2012; Glasson et al. Citation2019) and is at the heart of effective EIA (Palerm Citation2000; Arts et al. Citation2012; Glasson et al. Citation2019). In this context, Wood (Citation2003) suggested that it ‘would not be EIA without public consultation and participation’. Furthermore, Hunter (Citation2016) and Ojogbo (Citation2018) remarked that the principal reason for conducting EIA is to notify the public about development projects and to engage them in the establishment and mitigation of the possible positive and negative environmental and social impacts and costs of a proposed development.

Over the past few decades, there has been an active professional debate on who the public in EIA processes is and/or should be. In this context, Dietz and Stern (Citation2008) defined the public as people, groups or organizations that may benefit from or be negatively affected by the environmental effects of a development decision. Webler et al. (Citation1995) described the public as any person or group who consider themselves to be likely affected by the consequences of an action. On EIA related public participation (PP), Glasson et al. (Citation2019, 2005) suggested that those affected by a proposed activity were those that were likely to experience physical, health and/or socio-economic implications. Someone affected can thus be a person, an industry or a business, as well as a statutory or non-governmental environmental group. Whilst the general public can include individuals that are just interested in a particular development or experts from, e.g. government and authorities (Canter and Wood Citation1996; Palerm Citation2000; Petts Citation2007; Sinclair et al. Citation2021), it is particularly important to include those that are potentially directly and negatively affected (Glucker et al. Citation2013; Glasson et al. Citation2019).

Effective public participation is important for a variety of reasons. These include the generation of information and knowledge, including traditional knowledge, which can ultimately lead to better-informed decisions (Reed et al., 2018). Furthermore, PP promotes development of co-ownership through improved transparency and accountability (Atieno et al. Citation2019) and can validate secondary sources of information (Webler et al. Citation1995; Wassen et al. Citation2011). In terms of risk mitigation for developers, PP can reduce the potential threat of communities rejecting development proposals (Suwanteep et al. Citation2017). PP also increases the possibility of learning of all those involved, including the general public, consultants and developers (Fischer et al. Citation2009; Devente et al. Citation2016).

Various authors have reported on problematic representations of different groups in EIA PP. For example, for China, Yao et al. (Citation2020) found that experts held dominant positions in PP processes because of their in-depth knowledge of a subject matter. Furthermore, in Ghana, in an evaluation of PP for an oil project, it was noted that consultation was limited to government officials (Bawole Citation2013). Likewise, in Uganda, during the PP conducted for a manufacturing related EIA, the community was represented by members of village local councils only (George et al. Citation2020).

Challenges are frequently connected with the presence or absence of power. Power inequalities are associated with, e.g. community positions, knowledge, money and wealth (Veneklasen et al. Citation2007; Gaventa Citation2004; Fischer and González Citation2021). Those holding leadership positions are often particularly visible (O’Faircheallaigh Citation2010; Chiweza Citation2021) and can use their positions to keep key issues affecting their interests on or off the agenda (Stauss et al. Citation2012; Gaventa Citation2004). Also, those who have low levels of education and who lack knowledge are often excluded from PP because they are thought to have little to offer (Marzuki Citation2015).

In developing countries, challenges have been said to frequently differ between urban and rural projects (Lessmann and Seidel Citation2017). In rural areas, levels of illiteracy are usually higher than in urban areas. This is connected with poor education opportunities. Furthermore, rural residents who are educated often migrate from rural to urban areas in search of employment. This restricts capacities in rural areas to express knowledge-based arguments (Smith and Krannich Citation2000; Agrawal Citation2014). In rural areas, PP is also at times constrained by cultural barriers. These include issues surrounding gender, with women being underrepresented in many contexts (Carlson and James G Gimpel 2019; Hooghe and Botterman Citation2011). Another cultural barrier is the dominance by certain individuals, including, for example, traditional leaders in connection with their cultural role as communities’ gatekeepers (Plummer Citation2013; Michalopoulos and Papaioannou Citation2015; Hasan et al Citation2018). On the other hand, in urban areas, a challenge for EIA PP may be e.g. people with busy schedules who are finding it difficult to participate (Hooghe and Botterman Citation2011).

This paper reports on parts of a PhD research project of the first author on PP practices in EIA in Malawi (here implemented as environmental and social impact assessment – ESIA) which was conducted between 2017 and 2021. Twelve ESIA cases (six urban and six rural) from three districts are subsequently explored. Malawi was chosen because of the comprehensive legal framework that is in place with respect to public participation. This is stipulated in the constitution and the Environment Management Act of 2017 (GoM 2017) as well as other environmental policies. To date, there has been no assessment of the occupants of PP space in the country. Whilst focusing on Malawi, the approach used here can be adapted for use in other countries in the developing world, in particular, those with similar contexts. The findings should be of interest to policy-makers, practitioners and researchers elsewhere, too.

Context

Malawi is located in Central Africa, and according to National Statistics Office (NSO), it has a population of about 17.5 Million NSO, (Citation2019). Administratively, the country is divided into three regions; the North, the Centre and the South. There are 28 districts in the country, of which six in the Northern Region, nine in the Central Region and 13 in the Southern Region (NSO Citation2020).

Districts are divided into urban and rural areas. In line with NSO (Citation2019), urban areas are defined as the four major cities of Blantyre, Lilongwe, Mzuzu and Zomba, as well as other towns, and all Bomas (district administrative areas) and gazetted town planning areas. Subsequently, in this paper, practices in three districts are considered, comprising urban and rural areas: Mzimba (Mzuzu City and Mzimba Rural) in the North; Lilongwe (Lilongwe City and Lilongwe Rural) in the Centre; and Chikwawa (Chikwawa Urban – Boma area and Chikwawa Rural) in the South.

Districts are divided into traditional authorities (TA) and each TA comprises several villages. These are grouped together to form group villages, headed by group village headmen (GVH). Village headmen (VH) and their subjects report to GVHs (Muriaas et al. Citation2020). This structure is restricted to rural areas and only to urban areas located in districts. In urban areas located in cities, chiefs are mostly called block leaders or local leaders (Cammack et al. Citation2009). There are also a few places in cities located in urban areas where a chief is called village headman or group village headman. In such areas, positions are acquired through elections, while in rural areas chieftaincy is hereditary (Chiweza Citation2007; Cammack et al. Citation2009).

In Malawi, chiefs are prominent leaders in rural areas. They are said to maintain the country’s cultural norms and values. Their roles are wide-ranging, including land allocation, conflict resolution, appointment of other chiefs, mobilizing and representing communities (Chinsinga Citation2006; Kita Citation2019). In urban areas, they are mostly prominent in coordinating funerals and, to some extent, resolving minor conflicts. This means chiefs hold more authority in rural areas than in urban areas (Cammack et al. Citation2009; Eggen Citation2011). Among other reasons, this is because the Chief’s Act (GoM Citation1967) does not give powers to chiefs to exercise their authority in urban areas unless there is permission from local government (Cammack et al. Citation2009; Eggen Citation2011).

With respect to PP in ESIA, as mentioned in the introduction, the Government of Malawi has put policy, legal and regulatory frameworks in place that recognize the importance and value of PP in decision-making processes. Starting with the constitution, Malawi has included a progressive bill of rights for free expression of opinions (sections 34 to 37). Consequently, with such provisions in the principal law, PP in ESIA projects is obliged to enable communities to have their opinions heard and their views brought on board in decision-making.

The Malawi Vision 2063 is the overarching long-term vision guiding the development policy framework for Malawi, succeeding the Malawi Vision 2020. One of the enablers of the Vision 2063 is reported to be effective governance. This is supposed to be achieved by ensuring that citizen engagement and participation is attained (NPC Citation2020).

The National Environment Policy (2004) provides for an environmental planning framework, including undertaking ESIAs for certain projects in section 4.4 (GoM Citation2004). In order to comply with the policy, developers must ensure that the public is involved in the ESIAs and that all sectors of the public, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the private sector, community-based organizations (CBOs) and the general public are adequately consulted.

The Environment Act of 2017 (The Act) covers public participation in Section 5. It sets out that access to environmental information in ESIA be provided to communities and that the public has a right to participate directly or through representative bodies. The arrangement of such participation is to be devised by the ESIA lead agency. Furthermore, the Act provides for access to administrative and judicial means in case of harmful or adverse impacts.

Malawian ESIA guidelines, established in 1997, outline in some detail the procedure for PP. This includes a call for all affected and interested groups to be consulted, including the general public, grassroot communities, government authorities, developers, elected officials, investors and NGOs (GoM 1997). However, Chiweza (Citation2021) observed that there is no guarantee that the principle of citizen participation will be adhered to and enforced.

Methodology of the research study underlying the paper

PP in 12 ESIA projects (six urban and six rural) from three districts was explored. The sample was drawn from a list of ESIA projects submitted and approved by the Malawian Environmental Affairs Department (EAD) between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2018. The whole list comprised 65 ESIAs from 16 districts. The focus was then set on three districts which had both, rural and urban projects. A total of 26 urban and rural ESIAs were found to be located in these 3 districts; and 12 ESIAs (four projects from each district) were randomly chosen for further exploration, as follows:

Mzimba rural: A timber factory in the Traditional Authority (TA) Kampingo Sibande; and a quarry mine in the TA of Mtwalo;

Mzimba urban: An abattoir in Sonda Industrial Area; and a skills development centre in Dunduzu;

Lilongwe rural: A quarry mine in the TA Mazengera; and a quarry mine in the TA Kabudula;

Lilongwe urban: An abattoir in Kanengo Industrial Area; and a hotel in the city of Lilongwe;

Chikwawa rural: An irrigation project in the TA Kasisi; and a solar farm in the TA Makhuwira;

Chikwawa urban: A training college in the TA Katunga; and an irrigation project in the TA Katunga

Ethical approval for the research was sought from the University of Liverpool (UK) and the local research ethics committee in Malawi. Furthermore, consent was sought from participants that were to be interviewed with consent forms, explaining the level of confidentiality and anonymity of responses. For confidentiality reasons, the twelve projects are only associated with geographical locations only and not with specific names.

For each of the 12 projects, an average of 10 persons were randomly selected from the public participation attendees’ lists contained in the 12 ESIA reports and subsequently approached for interview. Lists for participation attendees are routinely prepared by ESIA consultants based on their ToRs. The total number of registered participants in each project varied widely. Ten of the PP meetings had between 13 and 40 registered participants in the ESIA reports, with one also having 150 and another one having 212 registered participants. In this context, project area size and number of participants were found to be correlated (see ).

Table 1. Number of PP participants registered, approached and interviewed.

A total number of 124 individuals from the lists (61 from rural and 63 from urban areas) were contacted. In this context, firstly, it was ascertained that all of them really did participate in the respective ESIAs. Somewhat surprisingly, only about two-thirds (85) said they did take part in ESIA consultation while nearly one-third (39) said they did not. This in itself is an important finding. In this context, one interviewed consultant explained that ESIA consultants ‘invent’ PP participants in order to make lists long enough to aid in the approval process of the ESIA reports. There are no formal requirements as to how long a list should be, but the consultant suggested that longer lists are considered to be ‘better’. The subsequent analysis and presentation of results is based on responses of the remaining 85 individuals who took part in ESIA PP. Also, six consultants were interviewed.

shows the total number of PP participants and area size of each project, as follows:

Public participants listed in a particular ESIA report (‘Registered’);

Number of public participants approached for interview (‘Approached’);

Number of public participants who were interviewed, based on them being genuine ESIA participants (‘Interviewed’).

shows that 33 PP meetings’ participants were from urban areas and 52 were from rural areas.

Participants were asked the following questions:

Did you participate in the ESIA PP?

Why do you think you were invited to take part in PP? If potentially affected, how were you affected

Did everyone within the vicinity of the project participate in the ESIA PP?

Do you hold any positions in your community or elsewhere? If yes, what positions are you holding

How were you notified about the PP event?

What methods were used in PP?

Where did the meetings take place?

Did you contribute something to the PP meeting? If not why did you not contribute

Was there any feedback from the developer following the participation meeting that you took part in? How was this feedback about participation communicated?

What’s the highest qualification you hold?

What is your gender?

Furthermore, consultants who prepared the ESIA reports were also approached and were asked the following questions:

(l) Who did you invite?

(m) Why did you invite them?

(n) Where were the meetings held?

(o) How were communities notified?

(p) What languages were used?

Responses were analyzed quantitatively, using the statistical package Stata 16. Some of the responses were also analyzed, using univariate frequency tables, while others (e.g. questions b, d and e) were multiple response questions. Respondents provided answers that were true for them and each response was analyzed as a binary variable.

Results

There are differences with respect to gender, education qualifications, notification and consultation methods, languages used and venues between urban and rural projects. There was limited participation of women from both, urban and rural, with only 9% of urban and 13.5% of rural areas’ participants being female. With respect to education, only a minority of rural participants (29%) had entered secondary school education while in urban areas, these constituted the majority of participants (79%).

Meetings were not publicly advertised, thus those who didn’t have the privilege to be notified were denied the possibility to attend PP meetings. With respect to languages used, PP meetings were held in local languages in rural areas (in Mzimba district, this was Tumbuka, while in Lilongwe and Chikwawa this was Chichewa). In urban areas, a mix of English and local languages was used.

Venues for meetings differed between rural and urban areas. In rural areas meetings were held within the project area at a site where the community would usually meet, e.g. a church, a school or under a big tree, while in urban areas meetings were mostly held in respondents’ offices. Methods of consultation also differed. In rural areas, the prominent method was community meetings, while in urban areas it was interview method.

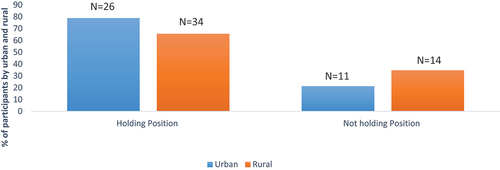

Participants were asked if they held any positions. shows that the majority of participants (60 of 85) were holding some positions; 79% of those from urban areas and 65% of those from rural areas.

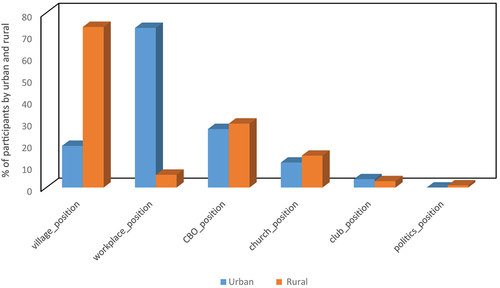

shows the types of positions held. These included village positions, workplace positions, community-based organization (CBO) positions, church positions, club positions and political positions. Village positions are traditional leadership positions, ranging from village headman to traditional authority (TA), while the equivalent positions in urban areas are elected block leaders, not governed by the Chief’s Act (Cammack et al. Citation2009). Furthermore, they include workplace positions. These are employed positions in either public or private organizations. Positions in community-based organizations (CBOs) are community-based charity groups organized in villages in the fields of natural resources, HIV/AIDs, education and human rights. Church positions are associated with different religious groups. Club positions include positions from social groupings who have common interests. They are mostly commercial and include, e.g. farmers clubs, village savings and loan schemes’ clubs. Finally, there are political positions associated with membership in political parties.

There was a correlation between those who went to secondary school and participants holding positions. Participants with higher level degrees were all holding some positions whilst those with lower levels of education did not. Ways of inviting people to PP meetings also differed between urban and rural projects. While participants in rural projects were notified by traditional leaders, in urban projects notification was mostly done through the consultants who prepared the ESIA reports.

shows those participants without and those with one or more positions that were affected by development (37) and those that were not (48). Of those, only a minority (3 urban and 10 rural) had no positions in society, i.e. only 15% of all those participating in PP represented ordinary affected citizens (22% or rural participants and 9% of urban participants).

Table 2. Affected and unaffected having no position and one or more positions.

indicates that the number of positions varied between participants, with some holding up to three positions. shows the number of positions held by participants. Finally, shows the types of positions held, in urban and rural areas.

Table 3. Number of Participants holding positions.

Table 4. Types of positions held, showing both frequencies and percentages in urban and rural areas.

There are considerable differences between urban and rural areas. In rural areas, nearly 74% of the participants occupied ‘village positions’, while in urban areas, similar positions were held by only 19% of participants. With regards to workplace positions, the difference between urban and rural areas was even more pronounced. These were held by 73% of urban participants, but only by about 6% of rural participants. In urban areas, the majority were ESIA experts and regulators, working with Government Ministries and Non-State Actors. In rural areas, such positions were mostly held by experts from the District Commissioner’s Office, which is known as the District Executive Committee (DEC). Elected political representatives were the least frequently represented, with only one ward councilor represented in PP in a rural project.

Presence at PP meetings

In order to establish if positions had any bearing on the extent of participation, participants were asked if they were able to actively contribute to the ESIA PP meetings. shows the results.

Table 5. People’s ability to actively contribute in PP meetings.

There is a statistically significant difference between urban and rural projects with a p value of 0.049 for the ability to contribute in meetings. More people in urban areas (84.9%) were able to actively contribute in meetings than in rural areas (65.4%). When asked if they thought their views had been considered in decision-making, only 21% and 8% of participants in the urban and rural projects, respectively, said they were. Results were further analyzed with regards to a possible correlation between holding positions and an ability to contribute. shows the results.

Table 6. People holding positions and people saying they were able to contribute.

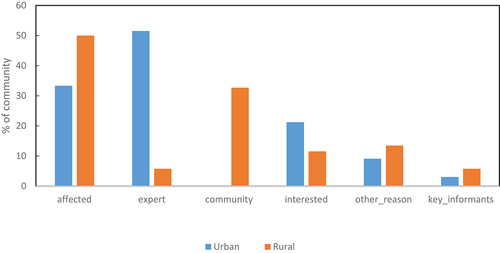

Seventy-seven percent of participants who held positions were able to actively contribute during PP meetings, whilst 23% said they were not. On the other hand, 64% of participants without positions said they were also able to contribute, whilst 36% said they were not. Finally, participants were also asked about their opinions as to why they thought they had been invited to PP meetings. shows their responses.

The majority thought they were invited because they were affected, were experts or community representatives. In rural areas, those who thought they were invited because they were affected constituted half of the interviewees, while in urban areas, the ’affected’ accounted for one-third. Some of these held positions (see ). With respect to urban areas, experts outnumbered the rest of the categories. As for the ‘affected’, when asked why they felt they were affected, they said they were directly impacted negatively by the project. In this context, most households reported that they had lost their land as the result of a project. Also, in two mining projects, the affected included those with houses that were in close proximity to the project sites and who were displaced as a result. Other participants were affected by other environmental impacts, such as dust and noise.

Enquiries about how consultants identified those affected produced different responses from urban than from rural areas. In rural areas, traditional leaders were responsible for identifying the affected. One interviewee said that ‘the chief knowing us so well, he knew exactly which piece of land belongs to which individual. He therefore relayed the message to all of those affected by the quarry area that we should meet with the developer. In urban areas, however, the ‘affected’ included a diverse range, comprising both businesses and communities that were near the proposed projects. Affected communities from areas located in districts were informed by traditional leaders, while those from cities were identified by consultants. Surprisingly, none of the participants claimed to have been consulted because they belonged to a Civil Society Organization (CSO), despite 16 NGOs working in the three regions (GoM Citation2017b).

Discussion

As explained above, people falling into three groups were present at PP meetings. These include 1) chiefs occupying the rural space at 74%; 2) experts occupying the urban space at 73%; and 3) those that are going to be potentially affected. The latter can be categorized into participants with and without positions. Within those affected in urban areas, three members (9%) had no positions in the community, while in rural areas, 10 (22%) of those who were affected had no positions. Overall, therefore, only 15% of PP meeting participants were ordinary affected citizens without positions.

Participants who hold some power can therefore be said to dominate the ESIA PP space. Sixty participants held positions, with 16 holding more than one. There was a positive correlation between people with positions and people who said they were able to actively contribute. Most of the participants who said they weren’t able to actively contribute and who didn’t have any positions attributed their inability to speak to the presence of their leaders. This is associated with what has been described as the dominating role of traditional leaders (Michalopoulos and Papaioannou Citation2015; Swapan Citation2016).

All secondary school graduates said they were able to actively contribute in PP meetings. However, in Malawi, only 2.7% of the rural and 13.7% of the urban population are secondary school graduates, having attained Malawi School Certificate of Education (MSCE) (NSO Citation2020, p. 33). Overall, the main occupants of the PP space in the 12 projects were chiefs, experts and the affected, with these groups not being mutually exclusive. This is because some of the invited chiefs were also affected. Subsequently, the three groups and their localities are discussed further and possible problems with a disproportionate representation of certain groups are depicted.

Rural chiefs’ PP space

In rural areas, chiefs take up almost three-quarters of the PP space (see ). Sixty-eight percent of them said that they were invited because they were affected by the development and because of their customary role of land allocation (chiefs are traditionally called ‘gogochalo’, which means custodian or owner of land, Kita Citation2019, p. 143). Importantly, chiefs have an advantage compared with others who are affected. In this context, interviewees suggested that chiefs are able to easily mitigate impacts of their land losses and about half of the ‘ordinary’ affected reported that they had different needs from their chiefs who were not necessarily representing them (chiefs are not bound by law to say what communities wish them to be reported). These results are consistent with what Chingaipe (Citation2013) reported with regards to the Greenbelt Programme in Salima district in the Central Region of Malawi, where communities protested against chiefs’ representation over land loss.

When consultants were asked as to why chiefs were consulted, one of them reported that in some instances, consultants and proponents deliberately limited consultations to chiefs because they are usually in support of development projects and that there is fear of opposition from affected communities and from those who may be against a project, such as Civil Society Organizations (CSOs). Also, in rural areas, chiefs are frequently readily accessible (Tieleman and Uitermark Citation2019), something that elected representatives are often not. Whilst people should be represented by their Member of Parliament (MP) and Ward Councilors (WC) under the principle of representative democracy, once elected, MPs and WCs often migrate to urban areas for better living conditions (Muriaas et al. Citation2020). Traditional leaders, on the other hand, being public servants with leadership based on inheritance always stay within their communities for as long as they live (Chiweza Citation2007).

Chiefs are not elected, but their leadership is inherited from parental lineages (Chiweza Citation2007; Trosper et al. Citation2008; USAID Citation2018). In this context, female chiefs only make up 14% of all chiefs (USAID Citation2018). The non-elected status is important as once a community has a chief who compromises people’s participation in development projects, the community will have a problem as long the chief lives (Chiweza Citation2021). Consequently, there is a perpetual effect on their influence on public participation. CSOs are usually only actively involved in projects with national interest because of financial constraints. This leaves ordinary people with little or no backup of CSO representation.

It is important that an over-representation of chiefs in PP meetings is contradictory to their roles described in the Chief’s Act. This Act empowers chiefs to carry out traditional functions under customary law as long as such functions are not in contradiction to the constitution or any written law and are not repugnant to natural justice or morality (GoM Citation1967). Policy makers have therefore aimed at reducing chiefs’ powers with the enactment of decentralization policy (GoM Citation1998, GoM 2016a) and Land Act (GoM Citation2016b).

With respect to the decentralizations policy, the underlying idea is that power is transferred to communities, which represents a paradigm shift from representative democracy to direct democracy (GoM Government of Malawi Citation1998; Eggen Citation2011). Therefore, on paper at least, roles and influence of local chiefs have been reduced in favour of councilors, who are locally elected (Chiweza Citation2007; Cammack et al. Citation2009). It is in this context that the Local Government Act has not given the chiefs voting powers in Local Councils, to which they are invited as ex officio members (Local Government Amendment Act 2010).

With respect to land allocation, the Land Act (GoM 2016b) and the Customary Land Act (GoM Citation2016a) have reduced customary powers of chiefs from the sole right of allocating customary land to communities. These land laws have led to the establishment of land committees responsible for processing lands. According to these new laws, communities can now lease customary land as customary estates, which have the same entitlement as leased land but will be managed and processed locally.

However, these land laws had not yet been operational in the three study districts at the time of the empirical research underlying this paper. Customary estates are currently operational in pilot districts only. Communities whose customary land is not leased occupy almost all the land involved in rural projects as well as in district urban projects. These communities are not compensated for the ownership of land but only for land use, as the compensation law stipulates the observance of customary law. Consequently, the amount of compensation provided is not as high as that paid to those with leased land (Kabanga and Mooya Citation2017). Some interviewees also reported that they were given money for compensation without signing for it, implying unfair practices with regards to compensation.

Whilst the evolving legal framework is not supporting the role of chiefs as actors of governance, chiefs still retain a lot of influence on developmental issues. Cammack et al. (Citation2009) argued that councilors are ignored in PP meetings because of their low education achievements, some being merely primary school certificate holders.Footnote(1) However, Chiweza (Citation2007) reported that 57% of chiefs in Malawi had also been enrolled only for primary education. This, therefore, suggests that the academic qualification of chiefs has no direct correlation with the exertion of power in their constituencies.

Finally, because chiefs are always available, Malawians were found to be more likely to give them higher approval ratings than elected leaders (Muriaas et al. Citation2020). This is probably also connected with hegemonic structures, though, in that community members during interviews reported that they feared that if they did not support their chiefs’ decisions, they could be denied a voice on other development projects that target individuals or households in their community. Such examples included distribution of subsidized fertilizer, which is also coordinated by chiefs.

Technical experts and interested parties in PP in urban area projects

Technical experts are key in the PP process because of their knowledge of areas such as ESIA. These experts were the majority of those involved in PP in urban areas, constituting slightly over half of the participants (52%). Other interested participants made up 21%. It was reported by consultants who prepared ESIA reports that experts were targeted because they were easy to mobilize. Their institutions were usually already named by the regulator in the ToRs for the ESIAs. However, it is possible that experts were also selected because most of the projects were falling within their implementation mandate (which is the case with e.g. experts from government departments). These experts can be expected to support projects, concurring with assertions that some experts have a vested interest in the outcome of the consultation meetings (Anuar and Saruwono Citation2018). However, experts often lack first-hand information with regards to potential impacts because they are usually consulted in offices that are away from project sites. This deprives them of the chance to obtain valid information on a project’s impacts. On the other hand, it can be difficult to mobilize affected communities, in particular, because urban residents tend to have busy schedules.

Communities can find it difficult to comprehend the complexity of environmental information contained in long and technically written ESIA reports. Importantly, effective public participation requires the necessary capacity to do so (Nadeem and Fischer Citation2011). It is in this context that the presence of experts is considered important because they are conveyors of technical information contained in the ESIA reports to communities. However, in rural projects, experts formed only 6% of those present in PP meetings. As alluded to earlier, one of the reasons is that experts mostly do not reside in rural areas, due to limited economic opportunities. This therefore produces some inequality between urban and rural ESIAs in the treatment of technical issues that are presented during PP meetings.

Affected ordinary individuals and communities

shows that affected ordinary individuals and communities without any position (and associated power) were poorly represented in PP meetings. Of the 37 affected interviewees (out of a total number of 85), only 3 from urban and 10 from rural areas were ordinary citizens that did not hold positions. Overall, including those with positions, the affected still only constituted half of those present in rural projects’ ESIA PP meetings and about a third in urban ESIA PP meetings. Although the Malawian policy and legal frameworks do not stipulate any percentages with regards to affected individuals and communities being present in PP meetings, the recommendation is that affected communities should be consulted comprehensively (GoM Citation1997; André et al. Citation2006). This reflects international PP principles that include calls for the affected public to participate prominently in decision-making processes (Rega and Baldizzone Citation2015; Glasson et al. Citation2019). Moreover, Waheed et al. (Citation2021) suggested that in areas with urbanization and industrialization agendas, consultation of affected communities should be prioritized and no one should be left behind in the public engagement process.

There are various negative consequences that can arise from development projects. For those that are affected, but are not able to contribute in PP, these can end up being particularly serious. In the cases considered here, the prime direct negative impact reported by communities was loss of land. One project in Chikwawa used up to 1600 hectares () of customary land. During interviews with affected individuals of one mining project in Lilongwe and Mzimba rural areas, it was reported that land was lost to the project, but there was no compensation. Moreover, with regards to another project in rural Lilongwe, it was reported that whilst there was some compensation for loss of land, the developer didn’t comply with the prevailing legal framework. This was evidenced by communities not being issued with any receipts or signatures when they were paid compensation. One community member lamented during the interview that ‘A lot of corruption was involved: no receipt was offered for compensation money for our land and we didn’t sign’.

Land is a valuable asset. In Malawi, land owned by local communities is their main asset (IFPRI, Citation2019). Losing land increases vulnerabilities, with short-term impacts including food insecurity and long-term impacts including persistent poverty. One interviewee from an irrigation project in Chikwawa remarked that ‘now we don’t have land and it looks like we are going to be stricken with more poverty; we will be dragged down to a state poorer than the way they found us. Our occupation used to be farming but now we do not have that anymore, not even vegetables for relish’.

Such complaints are particularly serious when considering that Malawi’s economy (similar to other developing countries) is agriculture-based, with nearly 93% of rural area residents relying on subsistence agriculture for their livelihood. Land is a key source of livelihood for over 84% of the nation’s rural population (NSO Citation2020). Projects implemented on customary land impoverish communities who have less land than they had before an intervention (Kerr Citation2005). These projects consequently enhance poverty amongst the already vulnerable instead of providing opportunities and poverty alleviation.

Not including ordinary affected community members in ESIA PP processes leads to them not being able to explore possibilities for benefiting from a project (Morrison-Saunders and Early Citation2008; O’Faircheallaigh Citation2010), such as employment. Interviewees reported that in one rural mining project in rural Lilongwe, unskilled labor from the capital which is about 30 kilometers away was recruited rather than unskilled labor from surrounding villages. In another case (a smallholder irrigated sugarcane scheme from rural Chikwawa), local employment opportunities were denied and workers were recruited from villages further away.

Non-inclusion of ordinary affected communities can also lead to overlooking potential adverse impacts (Sainath and Rajan Citation2015). For instance, in the case of a mining project in rural Lilongwe, flying rocks and dust emissions affected nearby houses and gardens emanating from the impact of quarrying activities. One example for the seriousness of the ensuing impact was the nearest house, which was located less than 5 meters away from edge of the mine. During interviews, occupants of that house were bitterly complaining that they could not stay at home during the day for fear of flying rocks falling on them.

Furthermore, exclusion of communities can lead to misreporting of information by consultants in ESIA reports. In one of the mining projects, the mitigation measure of ‘sprinkling water on the road to suppress dust’ was misreported as a positive impact in the ESIA report, as ‘dust generation’ would obviously occur as a result of vehicles passing past a school to and from a mine site. The school is very close to the mine site (only about 2 kilometers). Misreporting is problematic as it can disable environmental authorities from making well-informed decisions (Nadeem and Fischer Citation2011; Sainath and Rajan Citation2015). Provision of correct information should be a moral obligation.

Finally, exclusion of affected communities can lead to a waste of financial resources. One interviewee explained that during a Chikwawa irrigation project a borehole was drilled in a village without involving the community. While hydrological studies showed the availability of water, no salinity information was sought. The local community was, however, already aware of salty nature of the water, and their involvement would have avoided waste of scarce resources.

Conclusions

This paper reported on public participation (PP) practices in 12 ESIA projects from urban and rural areas in Malawi. Eighty-five individuals attending PP meetings were interviewed along with six representatives of consultancies preparing ESIA reports. Whilst the inclusion of all interested and affected groups and individuals is a key principle of PP (André et al. Citation2006; Dietz and Stern Citation2008), imbalances were revealed with regards to the composition of those being present in PP meetings from urban and rural areas. Only 15% of all those being present in PP meetings of the 12 ESIAs represented ordinary affected citizens that didn’t hold societal positions. From the cases presented, there are indications that non-inclusion of affected communities perpetuate loss of land, which leads to short-term effects such as food insecurity, thereby perpetuating long-term impacts including persistent poverty amongst communities.

In urban projects, technical (development, planning and ESIA) experts were found to be the main group of people being present in PP meetings. Those affected without any position in society made up only 9% of all urban participants. Technical experts were targeted by consultants organizing PP meetings mainly because they were easy to mobilize and were able to convey technical information contained in the ESIA reports. However, they were found to not necessarily represent the needs of those affected due to vested interests. Additionally, experts often lacked first-hand information because they did not usually live where impacts would occur.

In rural projects, traditional leaders (‘chiefs’) occupied about three-quarters of the PP space, while those affected without any position in society (i.e. ordinary affected citizens) made up only 22%. Chiefs were invited to PP meetings because of their cultural role of being gatekeepers of the communities they are supposed to represent, because of ease of access and also because they are custodians of customary land, which constitutes over 90% of the land in rural areas. However, those interviewed indicated that chiefs did not always take the needs of those affected into account.

It is therefore concluded that non-inclusion of affected individuals and communities exacerbates negative consequences, ranging from food insecurity, and pollution to increased poverty. Also, community members that are affected but are not included in ESIA PP can be dissatisfied with a proposed development. A consequence can be a failure to obtain local support (Marzuki Citation2015). Based on these findings, it is suggested that those affected should always be invited to PP meetings and they should be able to actively contribute to the meetings. However, in the examined ESIA cases, actors with power (as expressed by them holding formal positions) tended to control the PP space.

An unexpected finding was that only about two-thirds of those contacted from the ESIA PP lists, prepared by the ESIA consultants did actually take part in PP. In this context, it was reported that ESIA consultants ‘invented’ the PP participants to elongate the list of participants because the longer the list the more comprehensively PP is assumed to have been conducted.

Since developers and consultants control who is included in PP, it is suggested that policy-makers should put strategies in place for ensuring a balanced representation of both, affected and interested parties. This should include developing Terms of Reference (ToRs) that prescribe the inclusion of affected communities and of associated evidence in ESIA reports, such as photos and signatures of participants. Whilst there is currently no prescription of the ratio of affected to interested parties in PP regulations, the affected public should be in the majority because they are the ones suffering from negative effects of project implementation.

Policy makers should therefore ensure that developers adhere to regulatory requirements of consulting all stakeholders adequately. In this context, the ESIA reviewers should check that the affected public are adequately included in the list of PP participants. These measures should also be included in the ESIA regulations.

The conclusions and recommendations presented here are based on research conducted in Malawi. However, the authors assume that they are similarly applicable to a wide range of other countries with similar contexts. This includes other developing countries, in particular, those with traditional structures of decision-making and governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

This paper reports on parts of a PhD research project by the first author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. In Malawi, there is no minimum set qualification for councillors. Most of them are only semi-literate. The position does not attract highly educated people because the remuneration is very poor: They are paid only about $150 per month while MPs receive about $4700.

References

- Agrawal T. 2014. Educational inequality in rural and urban India. Int J Educ Dev. 34(1):11–19.

- Alonso S, Keane J, Merkel W. 2011. The Future of representative democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511770883.

- André P, Enserink B, Conner D, Croal P. 2006. Public Participation: international best practice principles. Special Publications Series. 34(4). Available at. [Accessed:7 March 2018]. https://conferences.iaia.org/2008/pdf/IAIA08Proceedings/IAIA08ConcurrentSessions/CS5-4_Assessing-Public-Participation-Best-Practice-Principles_Enserink.pdf.

- Anuar MINM, Saruwono M. 2018. Obstacles of public participation in the design process of public parks. null. 3(6):147–155. doi:10.21834/jabs.v3i6.247.

- Arts J, Runhaar HACF, Jha-Thakur U, Fischer, TB, Laerhoven U, Driessen FV, P J P, Onyango V. 2012. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance reflecting on 25 years of EIA practice in the Netherlands and the UK. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 14(4):1–40. doi:10.1142/S1464333212500251.

- Atieno OL, Mutui FN, Wabwire E. 2019. An analysis of the factors affecting public participation in environmental impact assessment: case study of selected projects in Nairobi City County, Kenya. Eur Sci J. 15(9):284–303. doi:10.19044/esj.2019.v15n9p284.

- Bawole JN. 2013. Public hearing or “hearing public”? An evaluation of the participation of local stakeholders in Environmental Impact Assessment of Ghana’s Jubilee oil fields. Environ Manage. 52(2):385–397. doi:10.1007/s00267-013-0086-9.

- Cammack D, Kanyongolo E, O’Neil T (2009) ‘Town Chiefs’ in Malawi. Africa Power and politics Working Paper No. 3. Availableat: 10.1.1.671.7919(Accessed: 6 June 2020).

- Canter LW, Wood C (1996) Environmental impact assessment. Available at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadg551.pdf (Accessed: 6 June 2020).

- Chingaipe H (2013) ‘Green belt initiative: an assessment of the policy processes and Civic engagement’Lilongwe:CISANET. Available: https://www.academia.edu/4683289/Policy_Processes_and_Civic_Engagement_in_the_Greenbelt_Initiative (Accessed:12 January 2019).

- Chinsinga B. 2006. The Interface between Tradition and Modernity. Civilisations. 54(54):255–274. doi:10.4000/civilisations.498.

- Chiweza AL. 2007. The ambivalent role of chiefs: rural recentralization initiatives in Malawi. In: Buur L Kydd HM, editors. State recognition and democratization in sub-Saharan Africa: a new dawn for traditional authorities? New York: Palgrave; pp. 53–78. 10.1057/9780230609716_3

- Chiweza AL. 2021. Discursive construction of citizen participation in democratic decentralisation discourses in Malawi. null. 29(1):23–55.

- Devente J, Reed MS, Stringer LC, Valente S, Newig J. 2016. How does the context and design of participatory decision making processes affect their outcomes? Evidence from sustainable land management in global drylands. Ecol Soc. 21(2):24. doi:10.5751/ES-08053-210224.

- Dietz T, Stern PC. 2008. Public participation in environmental assessment and decision making. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Eggen Ø. 2011. Chiefs and everyday governance: parallel state organisations in Malawi. J South Afr Stud. 37(2):313–331. doi:10.1080/03057070.2011.579436.

- Fischer TB. 2007. Theory and Practice of Strategic Environmental Assessment -towards a more systematic approach. London: Earthscan.

- Fischer TB, González A, eds. 2021. Handbook on Strategic Environmental Assessment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fischer TB, Kidd S, Jha-Thakur U, Gazzola P, Peel D. 2009. Learning through EC directive-based SEA in spatial planning? Evidence from the Brunswick region in Germany. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29(6):421–428. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2009.03.001.

- Gaventa J. 2004. Representation, community leadership and participation: citizen involvement in neighbourhood renewal and local governance. Report, Neighbourhood Renewal Unit, Office Of Deputy Prime Minister, July, 04. Accessed:7 March 2018, Available at. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/12494/Gaventa_2004_representation.pdf?sequence=1

- George TE, Karatu K, Edward A. 2020. An evaluation of the Environmental Impact Assessment practice in Uganda: challenges and opportunities for achieving sustainable development. Heliyon. 6(9):e04758. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04758.

- Glasson J, Therivel R, Chadwick A. 2019. ‘Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment.’, 5th, ed. London: Routledge. 10.4324/9780429470738

- Glucker AN, Driessen PPJ, Kolhoff A, Runhaar HAC. 2013. Public Participation in Environmental Impact Assessment: why who and how? Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:104–111. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2013.06.003.

- GoM(GovernmentofMalawi). 1967 ‘Chief’sact’, Available at : https://www.ecolex.org/details/legislation/chiefs-act-cap-2203-lex-faoc117646/]. (Accessed:5 December 2020).

- GoM (Government of Malawi) 1997. ‘Environmental Impact Assessment Guidelines’, Available at: http://www.sdnp.org.mw/enviro/eia/chap1.html (Accessed: 6 June 2020).

- GoM(Government of Malawi). 1998. Malawi Decentralisation Policy’, Available at: https://npc.mw/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Decentralization-policy.pdf ( Accessed: 10 June 2020).

- GoM (Government of Malawi). 2004. ‘National Environmental Policy’Malawi. Available at: http://www.sdnp.org.mw/environment/policy/NEP1.htm (Accessed: 4 December 2021).

- GoM (Government of Malawi). 2016b ‘Customary Land Act 2016’. Available at:https://www.ecolex.org/details/legislation/customary-land-act-no-19-of-2016-lex-faoc170882 (Accessed: 3 December 2021).

- GoM (Government of Malawi) ‘Land Act (2016b)’. Available at https://leap.unep.org/countries/mw/national-legislation/land-act-2016-no-16-2016 (Accessed: 3 December 2021).

- GoM (Government of Malawi). 2017a ‘Environment Management Act’. Available at: https://ead.gov.mw/storage/app/media/Resources/Miscellaneous (Accessed: 20 December 2021).

- GoM (Government of Malawi). 2017b. Lilongwe district council socio-economic profile: 2017 - 2022. Available at: https://www.collectionbooks.net/pdf/lilongwe-district-socio-economic-profile (Accessed: 20 June 2020).

- Hasan MA, Nahiduzzaman KM, Aldosary AS. 2018. Public participation in EIA: a comparative study of the projects run by the government and non-governmental organizations. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 72:12–24. doi:10.1016/J.EIAR.2018.05.001.

- Hooghe M, Botterman S. 2011. Urbanization, community size, and population density: is there a rural-urban divide in participation in voluntary organizations or social network formation? Nonprofit And Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 41(1):120–144. doi:10.1177/0899764011398297.

- Hunter DB. 2016. International environmental law. In: Harris PG, editor. Routledge Handbook of Global Environmental Politics. London and New York: Routledge; pp. 124–137. doi:10.4324/9780203799055.ch10.

- IFPRI. 2019. IFPRI Key Facts Series : Poverty May 2019 Background to the Integrated Household Surveys, Ifpri. Available at: https://massp.ifpri.info/files/2019/05/IFPRI_KeyFacts_Poverty_Final.pdf (Accessed: 7 May 2020).

- Kabanga L, Mooya MM. 2017. Assessing compensation for customary property rights in Malawi: the case of Mombera University project. null. 2(4):483–496. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.280029.

- Kerr RB. 2005. Food security in northern Malawi: gender, kinship relations and entitlements in historical context. J South Afr Stud. 31(1):53–74.

- Kita SM. 2019. Barriers or enablers? Chiefs, elite capture, disasters, and resettlement in rural Malawi. Disasters. 43(1):135–156. doi:10.1111/disa.12295.

- Lessmann C, Seidel A. 2017. Regional inequality, convergence, and its determinants–A view from outer space. Eur Econ Rev. 92:110–132. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.11.009.

- Marzuki A. 2015. Challenges in the Public Participation and the Decision Making Process. Sociologija i prostor/Sociology & Space. 53(1). doi:10.5673/sip.53.1.2.

- Michalopoulos S, Papaioannou E. 2015. On the ethnic origins of African development: chiefs and precolonial political centralization. Acad Manage Perspect. 29(1):32–71. doi:10.5465/amp.2012.0162.

- Morgan RK, Hart A, Freeman C, Coutts B, Colwill D, Hughes A. 2012. Practitioners, professional cultures, and perceptions of impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 32(1):11–24. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2011.02.002.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Early G 2008. What is necessary to ensure natural justice in environmental impact assessment decision-making?. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 26(1):29–42.

- Muriaas R, Wang V, Benstead L, Dulani B, Rakner L. 2020. It takes a female chief: gender and effective policy advocacy in Malawi. SSRN Electron J. 11. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3676333.

- Nadeem O, Fischer TB. 2011. An evaluation framework for effective public participation in EIA in Pakistan. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 31(1):36–47. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2010.01.003.

- NPC (National Planning Commision) 2020. Available at: https://npc.mw/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/MW2063-VISION-FINAL.pdf (Accessed: 29 January 2021).

- NSO (National Statistical Office). 2019. Malawi Poverty Report 2018. Available at: file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/malawi_poverty_report.pdf (Accessed: 19 December 2017).

- NSO (National Statistical Office). 2020. ‘The Fifth Integrated Household Survey (IHS5) 2020 Report’ Available at: http://www.nsomalawi.mw/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=230&Itemid=111(Accessed: 19 December 2017).

- O’Faircheallaigh C. 2010. Public participation and environmental impact assessment: purposes, implications, and lessons for public policy making. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30(1):19–27. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2009.05.001.

- Ojogbo SE. 2018. Public participation and environmental degradation in developing markets: the challenges in focusing on Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in Nigeria. Legal Issues Journal. 6(1):37–60. doi:10.4236/blr.2021.121007.

- Palerm JAR. 2000. An empirical-theoretical analysis framework for PP in Environmental Impact Assessment. J Environ Assess Policy Management. 43(5):581–600. doi:10.1080/713676582.

- Petts J. 2007. Learning about learning: lessons from public engagement and deliberation on urban river restoration. Geogr J. 173(4):300–311. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2007.00254.x.

- Plummer J. 2013. Municipalities and community participation: a sourcebook for capacity building.Abingdon. Routledge.

- Rega C, Baldizzone G. 2015. ‘Public participation in Strategic Environmental Assessment’,: a practitioners’ perspective. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 50:105–115. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2014.09.007.

- Sainath NV, Rajan KS. 2015. Meta-analysis of EIA public hearings in the state of Gujarat, India: its role versus the goal of environmental management. Impact Assessment And Project Appraisal. 33(2):148–153. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.964085.

- Sinclair AJ, Doelle M, Gibson RB. 2021. Next generation impact assessment: exploring the key components. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 40(1):3–19. doi:10.1080/14615517.2021.1945891.

- Smith MD, Krannich RS. 2000. ‘Culture Clash Revisited’, Newcomer and Longer‐Term Residents’ Attitudes Toward Land Use, Development, and Environmental Issues in Rural Communities in the Rocky Mountain West. Rural Sociol. 65(3):396–421. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2000.tb00036.x.

- Stauss K, Boyas J, Murphy-Erby Y. 2012. Implementing and evaluating a rural community-based sexual abstinence program: challenges and solutions. Sex Educ. 12(1):47–63. doi:10.1080/14681811.2011.601158.

- Suwanteep K, Murayama T, Nishikizawa S. 2017. The quality of Public Participation in Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports in Thailand. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 19(2):1750008–1750021. doi:10.1142/S1464333217500089.

- Swapan MSH. 2016. Participatory urban governance in Bangladesh: a study of the gap between promise and realities. Environ Urban. 7(2):196–213. doi:10.1177/0975425316652548.

- Tieleman J, Uitermark J. 2019. ‘Chiefs in the city: traditional authority in the modern state. Sociology. 53(4):707–723. doi:10.1177/0038038518809325.

- Trosper R, Nelson H, Hoberg G, Smith P, Nikolakis. 2008. Institutional determinants of profitable commercial forestry enterprises among First Nations in Canada. Can J for Res. 38(2):226–238. doi:10.1139/X07-167.

- USAID. 2018. ‘Sociological analysis of traditional authorities in Malawi: democracy, rights and governance’. USAID in partnership with the Department of Political and Administrative Studies. Zomba: Chancellor CollegeUniversity of Malawi.

- Veneklasen L, Miller V, Budlender D, Clark C. 2007. ‘A New Weave of Power, People & Politics’–The Action Guide for Advocacy and Citizen Participation (Warwickshire, UK) Available at: https://justassociates.org/all-resources/a-new-weave-of-power-people-politics-the-action-guide-for-advocacy-and-citizen-participation/Accessible on 6 January 2019.

- Waheed A, Fischer T, Khan MI. 2021. Climate change policy coherence across policies, plans, and strategies in Pakistan—Implications for the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor Plan. Environ Manage. 67(5):793–810. Accessible on 9 January 2019, 10.1007/s00267-021-01449-y.

- Wassen MJ, Runhaar H, Barendregt A, Okruszko T. 2011. Evaluating the role of participation in modeling studies for environmental planning. Environ Plann B Plann Des. 38(2):338–358. doi:10.1068/b35114.

- Webler T, Kastenholz H, Renn O. 1995. Public participation in impact assessment: a social learning perspective. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 15(5):443–463. doi:10.1016/0195-9255(95)00043-E.

- Wood C. 2003. ‘Environmental impact assessment in developing countries: an overview’. Paper for conference on New Directions in Impact Assessment for Development: methods and Practices. Manchester: EIA Centre, School of Planning and Landscape, Univesity of Manchester. Available at:https://www.academia.edu/3420793/Environmental_impact_assessment_in_developing_countries_an_overview (Accessed: 3 February 2019).

- Yao X, He J, Bao C. 2020. Public participation modes in China’ s environmental impact assessment process: an analytical framework based on participation extent and conflictlevel. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 84(1):106400. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2020.106400.