ABSTRACT

Development and planning have long been a focus of tourism geographers. Although the ideas of development and planning are complex and challenging to define and study, there is a strong agreement on the academic and societal relevance of their research in tourism geographies: tourism is a growth industry which requires holistic and future-oriented planning measures that minimize the negative externalities of tourism and guide the industry's growth towards a development path. A brief overview of early phases and current directions of development and planning approaches in geographical tourism research shows how traditional approaches are still relevant. There is, however, a need to recognize distinct contextual and historical dimensions around the geographies of tourism development and planning in versatile research contexts. These historic and contextual elements influence the present and future characteristics and power relations of tourism in place and can help us to understand how tourism works with localities and localities with tourism.

摘要

发展与规划议题很久以来就是旅游地理学者的研究重点。尽管发展与规划思想很复杂, 对之界定与研究颇有挑战性, 但是旅游地理学中有一个强烈的共识, 就是发展与规划研究兼具学术与社会价值༚旅游业是一个增长性产业, 需要采取整体性和着眼未来的规划措施, 使旅游业消极的外部性最小化, 引导这个产业沿着发展的路径增长。简单概述旅游地理研究中规划与发展取向的早期发展阶段与现在的发展方向, 就表明传统的研究取向是为什么仍具有现实意义的。但是, 仍需要从多种研究背景下认识旅游发展与规划地理学不同的背景与历史要素。这些历史与背景要素影响着旅游发展与规划当前与未来的发展特征及其中的权力关系, 有助于我们理解旅游业是如何与地方性相互作用的

Introduction

‘Painters search out untouched unusual places to paint. Step by step the place develops as a so-called artist colony. Soon a cluster of poets follows, kindred to the painters; then cinema people, gourmets, and the jeunesse dorée. The place becomes fashionable and the entrepreneur takes note. The fisherman's cottage, the shelter-huts become converted into boarding houses, and hotels come on the scene. Meanwhile, the painters have fled and sought out another periphery – periphery as related to space, and metaphorically, as ‘forgotten’ places and landscapes. Only the painters with commercial inclination who like to do well in business remain; they capitalize on the good name of this former painter's corner and on the gullibility of tourists. More and more townsmen choose this place, now en vogue and advertised in the newspapers. Subsequently, the gourmets, and all those who seek real recreation, stay away. At last, the tourist agencies come with their package rate travelling parties; now, the indulged public avoids such places. At the same time, in other places the cycle occurs again; more and more places come into fashion, change their type, turn into everybody's tourist haunt’ (Christaller, Citation1964, p. 103).

Geographers have a long-standing interest in tourism planning and development (Hall & Page, Citation2014). The geographer Walter Christaller, better known for his contributions to Central Place Theory, made early efforts to study the formal spatial organization and development of tourism (Christaller, Citation1955, Citation1964). For him, as a reinvented tourism geographer after the Second World War (Barnes & Minca, Citation2013), the typical course of new tourism development in peripheral areas followed the above-described process. At a general level, this trajectory resembles the same pattern conceptualized by Stansfield (Citation1978) and, more famously, by Butler (Citation1980) as the Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution model and has clear connections to resource management and planning issues. Indeed, both development and planning have a long research tradition in tourism geographies with implications for identifying and understanding tourism impacts, management, and public policies; and more recently for sustainability and resilience in tourism (Butler, Citation1999; Hall, Malinen, Vosslamber, & Wordsworth, Citation2016; Lew, Ng, Ni, & Wu, Citation2016; Saarinen, Citation2006). Yet, ideas of tourism development and planning are subject to multiple conceptual frames, are interpreted differently from place to place, and evolve over time (see Pike, Rodríguez-Pose, & Tomaney, Citation2007).

Although there is no consensus about what development or planning precisely means in tourism (Hall, Citation2000), there is no disagreement about their academic importance and societal relevance in research. Tourism is widely regarded as a social and economic phenomenon that calls for proactive measures to help ensure positive development trajectories. The difference between growth and development is well acknowledged in tourism studies (Hall, Citation2009; Holden, Citation2013; Saarinen & Rogerson, Citation2014; Scheyvens, Citation2011; Telfer & Sharpley, Citation2008; Wahab & Pigram, Citation1997) and can be simplified by utilizing the United States Local Government Commission's distinction stating that ‘growth means to get bigger, development means to get better – an increase in quality and diversity’ (cited by Pike et al., Citation2007, p. 1253). Thus, while growth is generally seen as a quantitative indicator, the idea of development is more focused on qualitative dimensions in social and economic processes, such as the quality of life and well-being. In addition, development has two connected threads of meaning: development as a concrete material process and as a discourse (Lawson, Citation2007) which both influence the course, impacts, and planning issues of tourism in destination contexts (Saarinen, Citation2004).

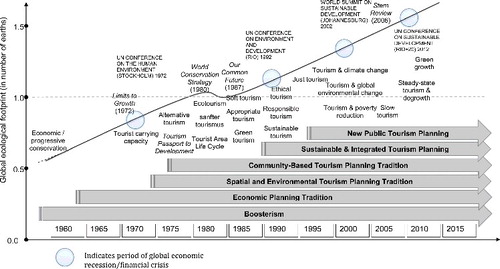

‘Planning is an extremely ambiguous and difficult word to define’ (Hall, Citation2000, p. 6). Overall, planning is a future-oriented and strategic decision-making process that aims to direct human actions to a desired and mutually agreed direction(s). Murphy (Citation1985, p. 156), for example, defined tourism planning as ‘anticipating and regulating change in a system to promote orderly development so as to increase social, economic and environmental benefits of the development process’. Therefore, public tourism planning can be understood as a potential tool for guiding tourism to a development path that creates benefits and well-being beyond the industry and its core operations. That said, the emphasis on wider socio-economic development in tourism is not an automatic premise or outcome as public planning actions can produce unexpected consequences and are often highly industry-oriented. Getz (Citation1987) identified four tourism planning approaches including industry-oriented ‘boosterism’ which unquestioningly promotes tourism growth per se. In addition, Hall (Citation2000) noted an alternative sustainable tourism planning tradition that specifically aims to foster a holistic and progressive approach and integration of economic, sociocultural, and environmental values in tourism development. More recently, the emergence of new public management and the neo-liberal project highlights the growth of public–private partnerships in tourism planning and development and the development of more corporatized public planning approaches which are barely distinguishable from those of the private sector (). Yet despite the now more than 30 years of research attention to sustainable, environmentally, and related tourism(s), and a plethora of strategies and interventions to balance the tensions between tourism growth and development (Hall, Citation2015a), tourism remains further away from being sustainable than ever (Hall, Gössling, & Scott, Citation2015).

Figure 1: Relationships between planning traditions, key themes in tourism development, global development milestones, and humanity's global footprint (Hall, Citation2015a).

Early approaches in tourism development and planning

Academic geographical research into tourism development and planning issues may be traced back to Europe and North America in the 1920s (Carlson, Citation1980; Gilbert, Citation1939; Lundgren, Citation1984; Mitchell, Citation1979; Wolfe, Citation1964). Early research topics and approaches included land use, locational issues, and the economic geography of tourism (Christaller, Citation1955; Duffield, Citation1984; Jones, Citation1933; McMurray, Citation1930; Wolfe, Citation1951). These topics involved a focus, explicitly or implicitly, on development and planning aspects in tourism. Gilbert (Citation1939, p. 16), for example, regarded tourism-related evolution and planning issues as part of urban studies by stating that seaside health resorts formed ‘a very important feature of English urban geography’ (also Gilbert, Citation1949). Gilbert was specifically interested in the reasons and contexts lying behind the development of resorts, including their transportation connections and world politics. In this respect, he acknowledged wider structures and processes beyond local issues, impacts, and carrying capacity, for example, that impacted the evolution and success of tourism destinations and which laid the foundation for the later work of Stansfield (Citation1978) and Butler (Citation1980).

After the Second World War and the rise of systematic studies in geography, the research emphasis turned to topics such as the modelling of tourism development, related questions of tourist supply and demand, and enquiries concerning locations and flows of tourists (Christaller, Citation1955; Miossec, Citation1967). A common research setting was a rural, remote, and/or natural amenity-rich area: with tourism characteristically seen as a typical phenomenon for peripheries (Christaller, Citation1964; see also Brown & Hall, Citation2000; Butler, Citation1980; Hovinen, Citation1982; Keller, Citation1987). Only since the 1980s has there developed a strong urban-focused scholarship around tourism development and planning issues (Jansen-Verbeke, Citation1986; Judd, Citation1995; Rogerson & Rogerson, Citationin press), while the growing literature on second homes and multiple place attachment also highlights the importance of relational perspectives on tourism mobility for policy and planning (Hall, Citation2015b; Mu¨ller & Hoogendoorn, Citation2013; Strandell & Hall, Citation2015).

From peripheries to centre, from presentism to historical and contextual understanding

In tourism development and planning practices, the periphery embodies symptoms of a distance-based (geographical and economic) isolation and lack of access, but it typically also relies on the perceived location and related societal interpretations of marginality (Shields, Citation1991). The tourism industry operates as a link and medium between local and larger spatial scales and socio-economic and environmental systems. Arguably, these core--periphery/global–local relations, often characterized by inequalities and uneven power structures (Britton, Citation1991; Scheyvens & Momsen, Citation2008), call for critical tourism and planning geographies. Harrison (Citation2008) suggests tourism development scholars should analyse the complexity and various benefit distribution patterns found in globalized tourism landscapes, especially in the Global South (see Christian, Citation2016). Such measures could bridge the theory–practice divide often present in development and planning studies. In this respect, the relatively recent emphasis on value-chain analysis (Judd, Citation2006) and evolutionary economic geography (EEG) (Brouder, Citation2014) offers fruitful avenues for greater understanding in specific tourism development and planning contexts.

While tourism is highly visible in many peripheries and can potentially contribute to local and regional development in areas suffering a lack of alternative socio-economic development prospects, there are urgent research problems in various other kinds of spatial settings. Recent rapid expansion of the so-called ‘sharing economy’ in tourism, for example, creates new kinds of planning issues in urban and suburban areas (Gurran & Phibbs, Citation2017) with a realization that there are urban ‘communities’ and interests that may have diverse opinions about the effects of products, such as Airbnb and Uber, in their neighbourhoods (Colomb & Novy, Citation2017; Hall, Le-Klähn, & Ram, Citation2017; Visser, Erasmus, & Miller, Citationin press).

Recent literature stresses that it is crucial to understand the historical nature and context of tourism development and planning in present situations (Buzinde & Manuel-Navarrete, Citation2013), including pre-tourism issues and relations (Manuel-Navarrete, Citation2016). Therefore, one significant void within existing international scholarship concerning geographies of tourism development and planning relates to historical studies. Indeed, the relative oversight of historical research in tourism studies in general and tourism geographical studies in particular is striking. Butler (Citation2015, p. 16) suggests that ‘a problem in tourism studies has been a prevailing present-mindedness and superficiality refusing deep, grounded or sustained historical analysis.’ Likewise, for tourism scholarship as a whole, Walton (Citation2003, Citation2009a, Citation2009b) stresses the underdevelopment of historical research and signals a strong message of the need for improved tourism researcher engagement with the past: ‘every practitioner of tourism studies, however immediately contemporary their ostensible concerns, needs to come to terms with the ever-moving frontier of the past’ (Walton, Citation2009a, p. 115). The South African historian, Albert Grundlingh (Citation2006, p. 104) reaffirms these sentiments and asserts ‘there is sufficient reason to believe that historians should not leave tourism for their summer holidays only.’ Overall, Walton (Citation2009a) contends that the modern tourism development landscape:

cannot be understood without reference to what has gone before; nor can we attempt to predict or preempt the future without achieving some understanding of where we, and others, have come from or of how relevant interested parties understand and appreciate their versions of the past. (p. 115)

In surveying the extant writings and debates by geographers specifically around tourism development and planning, one is struck by the resolutely ‘present-mindedness’ of current discourse (Coles & Hall, Citation2006; Hall & Page, Citation2009; Saarinen, Citation2014). As noted, amidst a swelling and rich body of international writings around geographies of urban tourism, planning, and development, mainstream debate is almost entirely concentrated upon present-day developments around tourism in cities which bypasses any substantive concern for past or inherited geographies of city tourism (Bickford-Smith, Citation2009; Rogerson, Citation2016; Rogerson & Rogerson, Citationin press). Nevertheless, concepts such as sustainable tourism or responsible tourism, a major focus for contemporary tourism and development scholarship, have rich historical antecedents (Walton, Citation2013),

Historical research on tourism ‘has usually been shunted into a siding and regarded, at best, as peripheral’ (Walton, Citation2012, p. 49), in the same way that the field is often portrayed in the wider discipline (Hall, Citation2013). Overall, there is only limited research by geographical scholars that seriously investigate tourism geographies of the past which, it can be argued, is essential to inform comprehension of the transformation of tourism destinations and how we arrived at contemporary tourism development and planning issues (Butler, Citation2015; Saarinen, Citation2004; Walton, Citation2003, Citation2009b). The value addition for tourism geographers to pursue historical research is evidenced by the findings of, for example, a cluster of African studies variously around shifting patterns of accommodation services (Magombo, Rogerson, & Rogerson, Citationin press; Pandy & Rogerson, Citation2014; Rogerson, Citation2011, Citation2013), the evolving architecture of transport infrastructure for tourism development (Pirie, Citation2009, Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2013), and the continued imprint of apartheid planning on the contemporary South African tourism landscape (Rogerson, Citation2016, Citation2017). Progress in tourism geographical research around development and planning, therefore, can be enriched by the extended application of historical perspectives in order to inform contemporary debates and practices. The historical dimension of tourism development and planning cries out for further geographical excavation.

Current geographies of tourism development and planning: insights of the Special Issue

The global growth of tourism has obviously made it an important economic sector. This has restructured socio-spatial relations and also turned tourism, including related development and planning tasks, to a politically important and influential activity that shapes and is influenced by global--local relations and power issues (Christian, Citation2016; Milne & Ateljevic, Citation2001). Thus, the global tourism industry is not only an economic matter but also a social and political process of change reflected in the current modes of neo-liberal governance (Bramwell, Citation2001; Hall, Citation2011), emphasizing the role of the markets rather than the state in tourism development and planning (Peck & Tickell, Citation2002). All these call for proactive, holistic, and responsible thinking and critical studies on tourism development and planning.

The special issue has its origins in a symposium meeting organized by the School of Tourism and Hospitality, the University of Johannesburg, in June 2015, focusing on diverse aspects, settings, and scales of tourism development and planning. In their paper, Nunkoo and Gursoy analyse the determinants of political trust and evaluate whether the latter influences residents’ support for mass and alternative tourism in Mauritius. For them political trust is a key requirement for (sustainable) tourism development and planning policies, and their results indicate issues such as the government's political and economic performance in tourism, interpersonal trust, and tourism benefits predicting political trust. Booyens and Rogerson focus on the nature of networking and learning by tourism firms in relation to accessing knowledge for innovation with evidence from the Western Cape, South Africa. They point out that even though tourism firms mostly use internal resources for innovation, external (non-local) knowledge is crucial for enhancing novel innovation and business development. Based on their empirical analysis, the existing network linkages between different spatial scales demonstrated the underdevelopment of local and regional innovation networks or systems, hindering the development potential based on knowledge networks.

Burrai, Mostafanezhad, and Hannam base their paper on timely issues of moral encounters and volunteering in tourism. They develop a conceptual approach from which to examine the moral landscape of volunteer tourism development in Cusco, Peru, by drawing from recent studies on assemblage theory. For them, a reconceptualization of volunteer tourism as assemblage may allow for more inclusive and detailed understandings of how geopolitical discourses and other contextual processes guide tourism development, planning, and policy. Pawson, D'Arcy, and Richardson continue the analysis of tourism development and (moral and economic) encounter in a community context in Banteay Chhmar, Cambodia. They use an ethnographic approach in the analysis of community member's views on a tourism project and its local value and developmental contribution. Their findings indicate the project has contributed towards community development albeit its financial sustainability and local practices, including community relations and support need to be improved. Chhetri, Chhetri, Arrowsmith, and Corcoran aim to model tourism and hospitality (T&H) employment clusters by developing a cluster-based theoretical framework for delineating geographic boundaries of T&H clusters and identify the factors that drive the form and shape of these clusters. They conclude the cluster-led strategy in T&H employment can forge a cohesive spatial structure that could support development and connectedness of destinations.

Saarinen approaches tourism destination development and planning processes in an enclave tourism context. He interprets and conceptualizes enclavic tourism development by utilizing the geographical ideas of territorialization and bordering. He concludes that in an extreme case, the enclavic tourism spaces with all-inclusive products can turn out to be highly all-exclusive for local communities with marginal benefits but potentially substantive costs, therefore requiring more holistic and inclusive planning in tourism. Brouder critically reflects on past EEG research in tourism geographies from a sustainable development perspective. In his conceptual paper, he highlights how a sustainable tourism perspective can provide potential tools for EEG theory and practice. Lew turns the focus on marketing, specifically on place promotion, which is a less emphasized aspect in tourism planning. He utilizes a place-making (organic) and placemaking (planned) dichotomy as ends on a continuum of options in destination promotion and related planning. According to Lew, an understanding of place-making and placemaking can provide fruitful insights into research questions on the political economy of tourism and the roles of hosts and guest, for example, in a co-production of tourism destinations.

Broadway continues the discussion about place promotion in Irish food tourism development and planning by analysing the effectiveness of Ireland's National Tourism Development Authority's (Fȃilte Ireland) programme called ‘Place on a Plate’ which aims to encourage hospitality actors to offer locally sourced seasonal food. His case study results from West Cork Food Trail suggest that the ‘Place on a Plate’ strategy had a minimal impact and more education is needed among the hospitality operators. Lenao analyses community, state, and power-relations in rural tourism development process in Lekhubu Island, Botswana. Community-based tourism development often includes a promise of local control and power, but his results show that, contrary to the popular narrative about devolution of power, the state has remained a powerful player in the overall decision-making processes. In the final paper, Bajgier-Kowalska, Tracz, and Uliszak analyse the spatial distribution of agritourism-oriented farms and the relationship between agritourism and ‘regular’ rural tourism in the Malopolska region, Poland. They conclude with a functional model of agritourism showing the relationship between environmental value, the nature of agricultural production, type of tourism, and the diversity of tourist offerings.

Conclusions

Development and planning issues have a long and chequered research history in tourism geographies. Nevertheless, there are transforming research needs and evolving dimensions in geographical studies on tourism development and planning. These new frontiers call for deeper social and economic theorization with a focus on a broad spectrum of socio-spatial development and planning situations and contexts from peripheries and amenity-rich landscapes to urban and metropolitan environments. There are also increasing research needs to emphasize moral and ethical aspects in tourism development, especially in the Global South, and how to incorporate them into planning. Notwithstanding the rhetoric of global responsibility in tourism and development, the imbalances and inequalities of contemporary tourism system probably contribute most to places that least require it. Accordingly, recent calls for political economy and ecology analyses are highly welcomed (Mosedale, Citation2011, Citation2015; Nepal & Saarinen, Citation2016), although there remains a desperate need to close the policy--action gap. Similarly, developments in governance require further study, especially given interest in e-governance and the framing of planning interventions. Finally, there is a critical imperative to understand the historical nature of tourism development and planning in present situations. These historically contingent processes often shape the present and future characteristics and power relations in tourism. Thus, they can help us to understand how tourism works with localities and localities with tourism. Both aspects – traditional views and new approaches – are showcased in this Special Issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jarkko Saarinen

Jarkko Saarinen is a professor of geography at the University of Oulu, Finland, and distinguished visiting professor at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. His research interests include tourism and development, sustainability and responsibility in tourism, tourism-community relations, tourism and climate change and wilderness studies.

Christian M. Rogerson

Christian M. Rogerson is a research professor in the School of Tourism and Hospitality, Faculty of Management, University of Johannesburg. His core research interests are focused around the tourism-development nexus in the global South. Within the context of sub-Saharan Africa, and especially Southern Africa, his research work has centred on issues of small enterprise development, local economic development, and shifting geographies of tourism.

C. Michael Hall

C. Michael Hall is a professor in the Department of Management, Marketing and Entrepreneurship, University of Canterbury, New Zealand; Docent, University of Oulu, Finland and Visiting Professor at Linnaeus University School of Business and Economics, Kalmar, Sweden. He has written widely on geographical aspects of tourism.

References

- Barnes, T. J., & Minca, C. (2013). Nazi spatial theory: The dark geographies of Carl Schmitt and Walter Christaller. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103, 669–687. doi:10.1080/00045608.2011.653732

- Bickford-Smith, V. (2009). Creating a city of the tourist imagination: The case of Cape Town, ‘the fairest cape of them all’. Urban Studies, 46, 1763–1785. doi:10.1177/0042098009106013

- Bramwell, B. (2001). Governance, the state and sustainable tourism: A political economy approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19, 459–477. doi:10.1080/09669582.2011.576765

- Britton, S. G. (1991). Tourism, capital, and place: Towards a critical geography of tourism. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 9, 451–478. doi:10.1068/d090451

- Brouder, P. (2014). Evolutionary economic geography and tourism studies: Extant studies and future research directions. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 540–545. doi:10.1080/14616688.2014.947314

- Brown, F., & Hall, D. (Eds.). (2000). Tourism in peripheral areas: Case studies. Clevedon: Channel View.

- Butler, R. (1980). The concepts of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5–12. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x

- Butler, R. (1999). Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tourism Geographies, 1, 7–25. doi:10.1080/14616689908721291

- Butler, R. (2015). The evolution of tourism and tourism research. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(1), 16–27. doi:10.1080/02508281.2015.1007632

- Buzinde, C. N., & Manuel-Navarrete, D. (2013). The social production of space in tourism enclaves: Mayan children's perceptions of tourism boundaries. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 482–505. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.003

- Carlson, A. W. (1980). Geographical research on international and domestic tourism. Journal of Cultural Geography, 1, 149–160.

- Christaller, W. (1955). Beiträge zu einer Geographie des Fremdenverkehrs [Contributions to a geography of the tourist trade]. Erdkunde, 9, 1–19.

- Christaller, W. (1964). Some considerations of tourism location in Europe: The peripheral regions-under development countries-recreation areas. Papers in Regional Science, 12(1), 95–105. doi:10.1111/j.1435-5597.1964.tb01256.x

- Christian, M. (2016). Tourism global production networks and uneven social upgrading in Kenya and Uganda. Tourism Geographies, 18, 38–58. doi:10.1080/14616688.2015.1116596

- Coles, T., & Hall, M. (2006). Editorial: The geography of tourism is dead. Long live geographies of tourism and mobility. Current Issues in Tourism, 9(4–5), 289–292.

- Colomb, C., & Novy, J. (Eds.). (2017). Protest and resistance in the tourist city. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Duffield, B. S. (1984). The study of tourism in Britain – a geographical perspective. GeoJournal, 9(1), 27–35. doi:10.1007/BF00518315

- Getz, D. (1987, November). Tourism planning and research: Traditions, models and futures. Paper presented at the Australian Travel Research Workshop, Bunbury.

- Gilbert, E. W. (1939). The growth of island and seaside health resorts in England. Scottish Geographical Magazine, 55, 16–35.

- Gilbert, E. W. (1949). The growth of Brighton. The Geographical Journal, 114(1–3), 30–52.

- Grundlingh, A. (2006). Revisiting the ‘old’ South Africa: Excursions into South Africa's tourist history under apartheid, 1948–1990. South African Historical Journal, 56, 103–122. doi:10.1080/02582470609464967

- Gurran, N., & Phibbs, P. (2017). When tourists move in: How should urban planners respond to Airbnb ? Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(1), 80–92. doi:10.1080/01944363.2016.1249011

- Hall, C. M. (2000). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships. Harlow: Pearson.

- Hall, C. M. (2009). Degrowing tourism: Décroissance, sustainable consumption and steady-state tourism. Anatolia, 20, 46–61. doi:10.1080/13032917.2009.10518894

- Hall, C. M. (2011). Policy learning and policy failure in sustainable tourism governance: From first- and second-order to third-order change ? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 649–671. doi:10.1080/09669582.2011.555555

- Hall, C. M. (2013). Framing tourism geography: Notes from the underground. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 601–623. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.007

- Hall, C. M. (2015a). Economic Greenwash: On the absurdity of tourism and green growth. In V. Reddy K. Wilkes (Eds.), Tourism in the green economy (pp. 339–358). London: Earthscan.

- Hall, C. M. (2015b). Second homes: Planning, policy and governance. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure & Events, 7(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/19407963.2014.964251

- Hall, C. M., & Page, S. J. (2009). Progress in tourism management: From the geography of tourism to geographies of tourism – a review. Tourism Management, 30, 3–16. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2008.05.014

- Hall, C. M., & Page, S. J. (2014). The geography of tourism and recreation (4th ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hall, C. M., Gössling, S., & Scott, D. (Eds.). (2015). The Routledge handbook of tourism and sustainability. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hall, C. M., Le-Klähn, D.-T., & Ram, Y. (2017). Tourism, public transport and sustainable mobility. Bristol: Channel View.

- Hall, C. M., Malinen, S., Vosslamber R., & Wordsworth, R. (Eds.) (2016). Business and post-disaster management: Business, organisational and consumer resilience and the Christchurch earthquakes. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Harrison, D. (2008). Pro-poor tourism: A critique. Third World Quarterly, 29, 851–871. doi:10.1080/01436590802105983

- Holden, A. (2013). Tourism, poverty and development. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hovinen, G. R. (1982). Visitor cycles – Outlook for tourism in Lancaster County. Annals of Tourism Research, 9, 565–583. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(82)90073-1

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. (1986). Inner-city tourism: Resources, tourists and promoters. Annals of Tourism Research, 13, 79–100. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(86)90058-7

- Jones, S. B. (1933). Mining tourist towns in the Canadian Rockies. Economic Geography, 9, 368–378.

- Judd, D. (1995). Promoting tourism in US cities. Tourism Management, 16(3), 175–187. doi:10.1016/0261-5177(94)00018-6

- Judd, D. (2006). Commentary: Tracing the commodity chains of global tourism. Tourism Geographies, 8, 323–336. doi: 0.1080/14616680600921932

- Keller, C. P. (1987). Stages on peripheral tourism development – Canada's Northwest territories. Tourism Management, 8(1), 20–32. doi:10.1016/0261-5177(87)90036-7

- Lawson, V. (2007). Geographies of care and responsibility. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 97, 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00520.x

- Lew, A. A., Ng, P. T., Ni, C. C., & Wu, T. C. (2016). Community sustainability and resilience: Similarities, differences and indicators. Tourism Geographies, 18, 18–27. doi:10.1080/14616688.2015.1122664

- Lundgren, J. O. J. (1984). Geographic concepts and the development of tourism research in Canada. GeoJournal, 9(1), 17–25. doi:10.1007/BF00518314

- Magombo, A., Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (in press). Accommodation services for competitive tourism in sub-Saharan Africa: Historical evidence from Malawi. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-Economic Series, 36.

- Manuel-Navarrete, D. (2016). Boundary-work and sustainability in tourism enclaves. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24, 507–526. doi:10.1080/09669582.2015.1081599

- McMurray, K. C. (1930). The use of land for recreation. Annals of American Geographers, 20, 7–20.

- Milne, S., & Ateljevic, I. (2001). Tourism, economic development and the global-local nexus: Theory embracing complexity. Tourism Geographies, 3, 369–393. doi:10.1080/146166800110070478

- Miossec, J. (1967). Un modele de l'espace touristique [A model for touristic space]. L'Espace Geographique, 6(1), 4–8.

- Mitchell, L. (1979). The geography of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 6, 235–244.

- Mosedale, J. (2015). Critical engagements with nature: Tourism, political economy of nature and political ecology. Tourism Geographies, 17, 505–510. doi:10.1080/14616688.2015.1074270

- Mosedale, J. (Ed.) (2011). Political economy of tourism: A critical perspective. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Murphy, P. (1985). Tourism: A community approach. London: Methuen.

- Mu¨ller, D. K., & Hoogendoorn, G. (2013). Second homes: Curse or blessing? A review 36 years later. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(4), 353–369.

- Nepal, S., & Saarinen, J. (Eds.) (2016). Political ecology and tourism. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pandy, W., & Rogerson, C. M. (2014). The evolution and consolidation of the timeshare industry in a developing economy: The South African experience. Urbani izziv, 25, S162–S175.

- Peck, J., & Tickell, A. (2002). Neoliberalising space. Antipode, 34, 208–216.

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2007). What kind of local and regional development and for whom ? Regional Studies, 41, 1253–1269. doi:10.1080/00343400701543355

- Pirie, G. H. (2009). Incidental tourism: British imperial air travel in the 1930s. Journal of Tourism History, 1, 49–66. doi:10.1080/17551820902742772

- Pirie, G. H. (2011a). Elite exoticism: Sea-rail cruise tourism in South Africa, 1926–1939. African Historical Studies, 43, 73–99. doi:10.1080/17532523.2011.596621

- Pirie, G. H. (2011b). Non-urban motoring in colonial Africa in the 1920s and 1930s. South African Historical Journal, 63(1), 38–60. doi:10.1080/02582473.2011.549373

- Pirie, G. H. (2013). Automobile organizations driving tourism in pre-independence Africa. Journal of Tourism History, 5(1), 73–91. doi:10.1080/1755182X.2012.758672

- Rogerson, C. M. (2011). From liquor to leisure: The changing South African hotel industry 1928–1968. Urban Forum, 22(4), 379–394. doi:10.1007/s12132-011-9126-9

- Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (in press). City tourism in South Africa: Diversity and change. Tourism Review International, 21.

- Rogerson, J. M. (2013). The changing accommodation landscape of Free State, 1936–2010: A case of tourism geography. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 19(S2), 86–104.

- Rogerson, J. M. (2016). Tourism geographies of the past: The uneven rise and fall of beach apartheid in South Africa. In R. Donaldson G. Visser J. Kemp J. de Waal (Eds.), Celebrate geography: Proceedings of the 11th biennial conference of the Society of South African Geographers (pp. 212–218). Stellenbosch: Society for South African Geographers.

- Rogerson, J. M. (2017). ‘Kicking sand in the face of apartheid’: Segregated beaches in South Africa. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-economic Series, 35, 93–109.

- Saarinen, J. (2004). ‘Destinations in change’: The transformation process of tourist destinations. Tourist Studies, 4(2), 161–179. doi:10.1177/1468797604054381

- Saarinen, J. (2006). Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research, 33, 1121–1140. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.007

- Saarinen, J. (2014). Tourism geographies: Connections with human geography and emerging responsible geographies. Geographia Polonica, 87, 343–352.

- Saarinen, J., & Rogerson, C. M. (2014). Tourism and the millennium development goals: Perspectives beyond 2015. Tourism Geographies, 16, 23–30. doi:10.1080/14616688.2013.851269

- Scheyvens, R. (2011). Tourism and poverty. London: Routledge.

- Scheyvens, R., & Momsen, J. H. (2008). Tourism and poverty reduction: Issues for small island states. Tourism Geographies, 10, 22–41. doi:10.1080/14616680701825115

- Shields, R. (1991). Places on the margin: Alternative geographies of modernity. London: Routledge.

- Stansfield, C. (1978). Atlantic City and the resort cycle background to the legalization of gambling. Annals of Tourism Research, 5(2), 238–251.

- Strandell, A., & Hall, C. M. (2015). Impact of the residential environment on second home use in Finland – testing the compensation hypothesis. Landscape and Urban Planning, 133, 12–33. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.09.011

- Telfer, D. J., & Sharpley, R. (2008). Tourism and development in the developing world. London: Routledge.

- Visser, G., Erasmus, I., & Miller, M. (in press). Airbnb: The emergence of a new accommodation type in Cape Town, South Africa. Tourism Review International, 21.

- Wahab, S., & Pigram, J. J. (Eds.) (1997). Tourism, development and growth: The challenge of sustainability. London: Routledge.

- Walton, J. K. (2003). Taking the history of tourism seriously. European History Quarterly, 27, 563–571. doi:10.1080/1461668042000208408

- Walton, J. K. (2009a). Histories of tourism. In T. Jamal M. Robinson (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of tourism studies (pp. 115–129). London: Sage.

- Walton, J. K. (2009b). Progress in tourism management: Prospects in tourism history: Evolution, state of play and future developments. Tourism Management, 30, 783–793. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2009.05.010

- Walton, J. K. (2012). ‘The tourism labour conundrum’ extended: Historical perspectives on hospitality workers. Hospitality and Society, 2, 49–75.

- Walton, J. K. (2013). Responsible tourism before ‘responsible tourism’? Some historical antecedents of current concerns and conflicts. Academica Turistica 6(1), 3–16.

- Wolfe, R. J. (1951). Summer cottages in Ontario. Economic Geography, 27(1), 10–32.

- Wolfe, R. J. (1964). Perspectives on outdoor recreation: A bibliographical survey. Geographical Review, 54, 203–238.