Abstract

Within tourism research, there has been little attention to research–practice knowledge exchange during the research process nor to practice-based research. This article examines a research-and-application project on creative tourism in which research–practice collaboration is explicitly foregrounded and made central. Through a reflexive process, the challenges this hybrid approach embodies and the pragmatic dilemmas that accompany the complexities of building closer research–practice relations and capturing practice-based knowledge are examined in three strategic areas: developing spaces for ongoing knowledge exchange, enabling practitioners to take on the role of co-researcher, and fostering researchers’ close attention to the application side of the project. In the context of the CREATOUR project, hybrid roles question who can do research, reinforce consideration of the added value of research processes for practitioners, and lead researchers to go beyond traditional research activities, with this ‘disruptive’ context causing tensions, uncertainties, and dynamic co-learning situations. Ongoing interactions over time are necessary to build relations, understanding, and trust, while flexibility and responsiveness are vital to address emerging issues. Training on research–practice collaboration, knowledge transfer, and mentorship techniques for both researchers and practitioners is advised. Challenges in integrating practice-based knowledge directly into research articles suggest a customized communication platform may be a useful ‘bridging’ mechanism between practice-based and academic knowledge systems.

摘要

摘要:在旅游研究领域, 很少关注研究过程中的研究与实践的知识交流, 也很少关注基于实践的研究。本文研究了一个创意旅游方面的研究应用项目, 该项目明确以研究与实践的合作为中心展开研究。本文通过一个反思的过程从三个方面(发展持续进行知识交流的空间,推动实业界认识承担合作研究人员的视角以及促进研究者密切关注项目的应用面)思考了这种混合方法表现出来的挑战以及伴随建立更紧密的研究实践关系, 获取实践性知识的复杂所提出的实际困难。在创意旅游项目的背景下, 多元混搭角色, 用这种产生紧张、不确定性和动态共同学习状况的“颠覆性”背景, 质问了谁可以做研究, 强化研究过程给从业者带来附加价值的想法, 以及带领研究人员超越传统的研究活动等方面的问题。为了建立关系、理解和信任, 需要不断地进行互动, 同时灵活性和反应能力对于解决新出现的问题至关重要。建议为研究人员和实践者提供研究-实践协作、知识转移和辅导技巧方面的培训。将基于实践的知识直接集成到研究文章中所面临的挑战表明, 定制的交流平台可能是基于实践的知识系统和学术知识系统之间有用的“桥梁”机制。

Introduction

The connections (or lack thereof) between research and practice have been debated and explored in the educational, business, health, and social work fields for some time (e.g. Palinkas, Citation2010; Walsh, Tushman, Kimberly, Starbuck, & Ashford, Citation2007), and practice-based and practice-led research methodologies have been extensively discussed in artistic fields (e.g. Freeman, Citation2010; Leavy, Citation2015). Within the tourism field, however, there is very limited research on the methodological intricacies of practice-based research and knowledge development. Developing closer links between research and practice in tourism has been discussed and, indeed, there is a call for academics to simplify and share the findings of research projects that may inform strategic decision-making by developing an understanding of the stylistic requirements for translating their knowledge to industry (Walters, Burns, & Stettler, Citation2015). To this end, some research does produce industry-sensitive materials; however, most methodological proposals focus on knowledge transfer and mobilization of academic findings in the post-research period, rather than the transfer occurring during the research period (Anderson & Sanga, Citation2018).

Collaborative research focuses primarily on the perspectives, interests, and needs of participants, requiring that these participants influence the entire research process, from project design, data gathering, and data analysis, to the presentation of final results (Lassiter, Citation2005). This entails close consideration of the complementarities of academic research and practice-based knowledges (Jeannotte & Duxbury, Citation2015), and the development of methodologies to weave them together. Practice-based research means that questions and methodology emerge through making, doing, and testing things out (Hope, Citation2016). Practitioner-researchers do not just think their way out of a problem, they ‘practice to a resolution’ (Nelson, Citation2013, p. 10), with practice viewed as more than just doing – as Wenger (Citation1998) remarked, it is ‘doing in a historical and social context that gives structure and meaning to what we do’ (p. 47). Within the tourism field, however, the potential of practice-based research approaches has also not been explored.

The research-and-application project that informs this article aims to explicitly foreground research–practice relations, with the imperative to bridge research and practice made central to the project. In this context, knowledge exchange and mobilization are seen as integral dimensions to catalyze and manage during the research project, not only in the post-research period, and practice-based experiences and insights are a valued dimension of the research. This experimental approach promises to provide insights for researchers seeking to develop closer research–practice relations and to capture practice-based knowledge within collaborative tourism research projects.

This article reports on a reflexive process that has examined the complexities of building closer research–practice relations and capturing practice-based knowledge within a research-and-application project. Guided by the long-standing question, ‘Why has the task of closer research–practice collaboration been so challenging to achieve?’, it focusses on the difficulties this hybrid approach embodies and the pragmatic dilemmas that accompany such work. In particular, the article examines and reflects on the ‘grubby business’ of research–practice collaboration in three areas that are central to this project:

Developing spaces for ongoing knowledge exchange, fostering informal discussion, learning, and knowledge-building, in which researchers and participating organizations develop relationships and opportunities to interweave complementary types of knowledge;

Enabling practitioners to take on the role of co-researcher, involving participating organizations in research tasks and knowledge co-creation, changing the norms of researcher–participant relations and expanding upon the concept of reciprocity; and

Fostering researchers’ close attention to the application side of the project, requiring researchers to attend carefully to ‘application’ and ‘implementation’ as an integral part of the overall project and, potentially, to act ‘beyond’ their usual research work roles.

Altogether, these aspects produce implications for the research processes and the roles and identities of researchers in this context. Within the research process, the question of who can do research is challenged, a reinforced questioning of the added value of the research process takes place, and researchers must reflect upon the complexities of making knowledge useful for practitioners and their wider communities. Consequently, the processes and strategies implemented in a research-and-practice project, and the issues realized in the design and implementation of these approaches, instigate both systemic and individual/professional dilemmas, discomforts, and messiness, with the act of stepping outside one’s comfort zone becoming a part of the process.

This article was developed through a reflexive process involving three of the researchers in the project.Footnote1 Reflexivity is an interpersonal process through which a person considers the relational and inter-subjective processes they are involved in, gives new meaning to the processes, and recognizes the active role they assumed in guiding events. Using a reflexive process as a method, true learning is only perceived to occur after one has been through a learning experience and taken the time to make sense of the experience. Understanding reflexivity as a process (Finlay, Citation2002), the authors of this article explore the mutual meanings shared within relationships, focusing on the situated and negotiated nature of these meanings. Drawing on lived experiences of participating within the research-and-application project, the researchers reflect on the uncomfortable aspects of how actions unfolded in praxis, and why things happened in various aspects of the overall process. In using the method of the reflexive process (Cheek, Lipschitz, Abrams, Vago, & Nakamura, Citation2015), this article aims to avoid sanitizing the reporting of the research process, creating qualitative research that shines a spotlight on how researchers and practitioners navigate tensions in designing and carrying out research together.

To contextualize the research-and-application approach of this project, the article begins by presenting a synthesis of research areas that address the issue of research–practice collaboration, from macro/systemic perspectives to micro/researcher perspectives. This is followed by a brief overview of creative tourism, the CREATOUR research-and-application project, and the participating organizations within it. Then, the article examines the three dimensions outlined above and discusses issues encountered in aiming to design strategies to encourage research–practice collaboration. In closing, it brings together the insights from these three examinations to comment on the ways in which a research-and-practice project disrupts methodologies and research practice more generally.

Bridging research and practice: a literature review

Discussions of knowledge exchange during research projects promoting research–practice collaboration are addressed in research from a macro/system perspective in the fields of knowledge transfer and mobilization, and stakeholder theory. Regarding the promotion of more egalitarian roles between researcher and practitioner, research relating to engaged scholarship, para-ethnography, researcher reflexivity, and reciprocity provide insights on approaches to disrupting ‘traditional’ research approaches.

Knowledge transfer and mobilization

Scanning broadly, there is a seemingly exponential growth of both research and practical activity in the field of knowledge transfer and mobilization, most prominently within the medical research field (Ward, Citation2017) and education (Vanderlinde & van Braak, Citation2010). The growing literature includes both a research-related approach and a more practical/application approach (Ferlie, Crilly, Jashapara, & Peckham, Citation2012; Greenhalgh & Wieringa, Citation2011; Oborn, Barrett, & Racko, Citation2013). Within this literature, only limited efforts have explored knowledge transfer and mobilization strategies in the tourism field (e.g. Tribe & Liburd, Citation2016) and there are only limited empirical studies on knowledge management in the hospitality industry (Hallin & Marnburg, Citation2008). Knowledge transfer and mobilization research in the tourism field has tended to focus on the commercial added-value that academics can bring to the public and private sector as consultants (Ryan, Citation2001), the transfer of academic knowledge to the industry via tourism graduates (Anderson & Sanga, Citation2018), and calls for universities to reconsider their current incentive systems that focus predominantly on journal publications that achieve minimal reach outside the academy (Walters et al., Citation2015).

The dominant knowledge transfer paradigm, reflected in these examples, has been criticized for reinforcing a hierarchical and linear model of knowledge creation. In this paradigm, ‘knowledge is transferred from knowledge ‘producers’ to knowledge ‘users’ such as practitioners, government, and industry actors and less often the lay public, who are all perceived as deficient in scientific understanding’ (Anderson & McLachlan, Citation2016, p. 297; Estabrooks et al., Citation2008). Attempting to address this issue, knowledge mobilization is put forward to provide a less hierarchical framework, based on ‘the reciprocal and complementary flow and uptake of research knowledge between researchers, knowledge brokers and knowledge users – both within and beyond academia – in such a way that may benefit users and create positive impacts…’ (SSHRC, Citation2018). Anderson and McLachlan (Citation2016) take up the concept of knowledge mobilization to frame collaborative research processes in which academic researchers ‘work to valorize multiple ways of knowing in the co-production of knowledge that is mobilized in intentional processes of social change, … engag[ing] with community and social movement actors as co-enquirers through horizontal processes of research, learning, and action’ (Kemmis, McTaggart, & Nixon, Citation2014, pp. 297–298).

Nonetheless, knowledge mobilization can sometimes reproduce an emphasis on only research-to-practice knowledge flows. For example, Ward (Citation2017) refers to knowledge mobilization as the process of moving knowledge to where it can be most useful, relating across different sectors of society and with different fields of power relations, and problematizing knowledge power hierarchies (Hart et al., Citation2013). This work focuses on the need to bridge knowledge production between scientific, practitioner, and policy-related contexts and shines a spotlight on two important aspects: the roles of researchers and practitioners in the process of knowledge creation, and how knowledge users can access and use this knowledge. Stakeholder theory perceives stakeholders, defined as people with the right and capacity to participate in the process, as part of a network of mutual dependencies where their individual interests can be jeopardized in diverse ways, and the satisfaction of all of them is necessary for maintaining the balance of the ensemble (Nilsson, Citation2007). However, a stakeholder approach is problematic in terms of initially identifying stakeholders, resistance to cooperation by stakeholders, and the fact that building consensus is a time-consuming and costly process (Ooi, Citation2013). Thus, more collaborative approaches to research that use reflexive understandings of long-term partnerships with diverse stakeholders are currently being developed to promote sustainable tourism development (Cockburn-Wootten, McIntosh, Smith, & Jefferies, Citation2018).

Greenhalgh (Citation2010) argues for an extension beyond the ‘impoverished’ notions of knowledge exchange and transfer towards ‘engaged scholarship’, during which knowledge emerges dialectically when academics and practitioners (or policymakers) must converge to address a problem (Van de Ven, Citation2007; Van de Ven & Johnson, Citation2006). Engaged scholarship is a movement that has been growing since 1995, which offers a new way of bridging gaps between the university and civil society, with the values of citizenship and social justice at the core of this process (Beaulieu, Breton, & Brousselle, Citation2018). The scholarship of engagement means creating a special climate in which academic and civic cultures communicate more continuously and more creatively with each other, enriching the quality of life for all, with the aim to democratize knowledge. Accordingly, researchers’ roles are not limited to knowledge production but expand to become ‘actors of change’ who participate actively in creative intellectual activities with various stakeholders. Experiential learning is core to engaged scholarship and researchers actively seek to contribute to the common good and consider their role of citizen as intrinsic.

Para-ethnography, researcher reflexivity, and reciprocity

Viewing ‘researcher-as-expert’ approaches as intrusive and detracting from creating knowledge, para-ethnography explores what it means for researchers to take seriously the efforts of their informants in producing academically relevant knowledge. Para-ethnographers are particularly concerned about ‘the new predicaments of expertise’, and tend to strongly ‘reject suppressive idolatries of control’ (Wilson & Hollinshead, Citation2015). Participants are not ethnographers per se, however, and their forms of reflexivity may be distinct from those of researchers hence the term ‘para’ ethnography (Beech, MacIntosh, & MacLean, Citation2010). The ‘para’ element makes itself felt in the multiple ways in which knowledge is produced in a ‘side-by-side’ way. Para-ethnography promotes forms of researcher–informer collaboration to promote reflexivity among both parties, by treating informants as both partners and observers in theory building. Building on community-engaged principles, the concept of ‘knowledge hybridity’ is important, whereby the knowledge produced is somewhere in the middle of the interaction between researcher and researched (Diver & Higgins, Citation2014).

Researcher reflexivity acknowledges the agency of the researchers, researched, academic audiences, and others in producing knowledge (Tribe & Liburd, Citation2016), and stresses the importance of establishing a non-exploitative and effective working relationship with significant others (Olsen, Citation2011). Reflexivity promotes the idea that researchers should expose the politics of representation implicated in research in order to represent their participants better (Pillow, Citation2003). It is also important to help validate qualitative research (Bakas, Citation2017) and generate ‘valid’ knowledge (Ateljevic, Harris, Wilson, & Collins, Citation2005). Research on researcher positionality and reciprocity, investigating questions of how to authentically reciprocate participants’ efforts throughout the research process, is a relatively new study area (Trainor & Bouchard, Citation2013). The most common form of reciprocal act is ‘giving-back’ to participants by conducting research that benefits these individuals. Extreme reciprocity is ‘the help given to research participants that goes beyond simply empowering them through knowledge production and which could perhaps be of use to them in the long-run’ (Bakas, Citation2017, p. 130), while dynamic reciprocity is an ongoing practice of exchange of mutual benefit between academic and community research partners in the context of community-engaged research (Diver & Higgins, Citation2014). In practice, researchers' ability to engage with the researched on a reciprocal basis is often compromised since academic reality is characterized by an increasing pressure for the individual to ‘publish or perish’ (Bakas, Citation2017).

Creative tourism

Creative tourism is a relatively young and dynamic field of tourism research and practice, generally defined as a type of tourism that offers travelers the opportunity to develop their creative skills and potential through active participation in creative experiences which are characteristic of the place where they are offered (Duxbury & Richards, Citation2019a; Richards & Raymond, Citation2000). It is a niche tourism area that emerged both as a development of cultural tourism and in opposition to the emergence of mass cultural tourism; its activities commonly incorporate four dimensions: active participation, creative self-expression, learning, and community engagement (Bakas, Duxbury, & Castro, Citation2018). Creative tourism responds to the contemporary motivations of travelers seeking meaningful and transformative experiences, and to be actively involved in the ‘everyday culture’ of the place that they visit through interactive experiences that are connected to that place (Richards, Citation2018).

Creative tourism does not fit well within traditional tourism research paradigms because it is not a mass market with significant economic impacts in urban and traditional holiday locales. However, in more and more places (and particularly in peripheral, rural places), creative tourism is fostering significant ‘soft’ impacts (Duxbury & Richards, Citation2019a). Consequently, a growing range of theoretical and disciplinary perspectives are being brought to studies of creative tourism, including by many researchers from outside the tourism field, producing an interdisciplinary nexus informed by the disciplines of tourism, cultural heritage, cultural development, creativity, cultural geography, and local and regional development, among other areas.

Research on creative tourism has included contributions from both academic researchers and practitioners offering observations, insights, and reflections on developments and issues in a wide variety of international contexts. Academic research accompanying the development of creative tourism has situated itself quite closely to the practices unfolding on the ground. Despite this situation, however, there continues to be a gap between theory and practice that has been evident in much scholarship on creative tourism, and there has been a lack of integrated research approaches that use a research-and-application framework to address this gap. Consequently, perhaps, in the creative tourism field we still know relatively little about ‘the profile, motivations, and experiences of those who provide or co-create the supply of creative experiences’ or ‘the business models adopted by creative tourism entrepreneurs’ (Duxbury & Richards, Citation2019b, p. 184). Related to this, one of the most challenging aspects of attending to practice-based issues has related to a lack of previously documented ‘successful case studies’ and guides (Bakas, Duxbury, & Castro, Citation2018; Duxbury, forthcoming).

Creative tourism and CREATOUR in Portugal

Tourism is currently one of the main drivers of the Portuguese economy and has been growing rapidly in recent years. In line with the trends of diversification of the tourism sector worldwide, creative tourism initiatives are now emerging in Portugal. Creative tourism is a new idea for tourism in Portugal and therefore not yet well understood. As a diversified area of practice, creative tourism encourages innovative practices in tourism (i.e. inspiring new types of creative and artistic activities and new perspectives on cultural resources and locale). Creative tourism initiatives highlight and articulate the local, the vernacular, the specificities of particular places. The small-scale and interactive nature of activities encourages experimentation, flexibility, changing offers, co-learning between locals and visitors, and networks of artisans and small entrepreneurs. Local design, implementation, and control allows for diverse sites of experimentation with content, models, and approaches. In this context, the CREATOUR project is piloting experimental practices and pilot trials to more fully understand its issues and potential in small cities and rural contexts in Portugal.

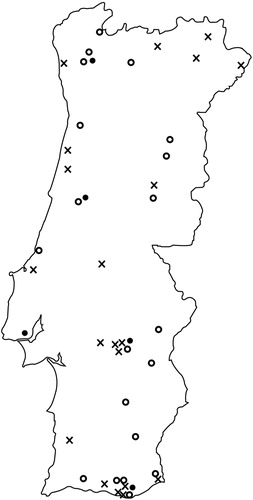

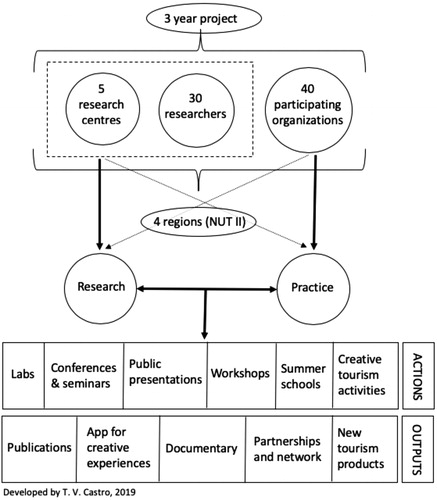

CREATOUR: Creative Tourism Destination Development in Small Cities and Rural Areas is a national three-year (2016–2019) interdisciplinary research-and-application project in Portugal. The project aims to connect the cultural/creative and tourism sectors through the development of an integrated research-and-application approach to catalyzing creative tourism in small cities and rural areas throughout the country. It involves five research centers working with 40 participating organizations located in small cities and rural areas across Portugal in the Norte, Centro, Alentejo, and Algarve regions (see ). presents an overview of the project’s main elements, actions, and outputs.

Figure 1. Map of the 40 pilots and 5 research centers involved in the CREATOUR project, Portugal. Source: Authors. Legend to map: o: 1st call CREATOUR pilots; x: 2nd call CREATOUR pilots; ●: Research centers.

Figure 2. CREATOUR’s main elements, actions, and outputs. Source: T. V. de Castro (used with permission).

The overall structure of the project is guided by OECD advice that creative sector development can be enhanced by policy measures and programs designed to build knowledge and capacity, support content development, link creativity to place, and strengthen network and cluster formation (OECD, Citation2014). These dimensions form the framework for CREATOUR’s approach.

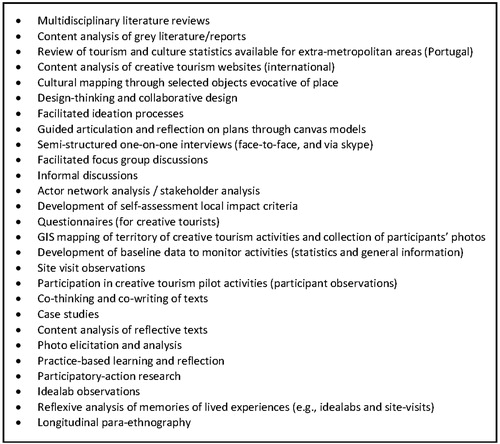

On the research side, the project aims to examine, monitor, and reflect on the creative tourism activities, including development patterns, reception experiences, and community impacts. lists the types of methodologies included in the project. The overall design of the project is rooted in the principles that there are multiple ways of knowing (Wilson & Hollinshead, Citation2015), that practice-based knowledge should interweave with academic research and be mutually informing (Jeannotte & Duxbury, Citation2015), and that research methodologies should be flexible and welcome epistemological ruptures (Kara, Citation2015). This approach acknowledges that an ‘ecology of knowledges’ exists (Santos, Citation2007) and that knowing is thus fundamentally based on inter-knowledge exchange.

On the practice side, the CREATOUR project aims to catalyze creative tourism offers in small cities and rural areas in Portugal, inform and learn through these initiatives, and link them with each other through the development of a national network. The project design incorporates network-building activities, among the pilots themselves (on a regional and national basis) and to connect with relevant public agencies. CREATOUR functions as more than simply a network to market creative tourism offers, but also to help its pilot projects by providing opportunities to build and share knowledge, network with others, improve their tourism offers, and create strategies to enhance community benefit. The project aims to offer visibility through critical mass and connectedness as well as support through research, co-learning, and capacity building. The project includes research on and articulation of post-project sustainability options, with researchers working with the participating organizations to design and create a network that continues after the end of the project.

Participating organizations and pilot activities

The participating organizations in the CREATOUR project were selected through two national open calls for pilot projects (with deadlines in January and November of 2017), with five organizations selected in each region (Norte, Centro, Alentejo, and Algarve) during each call. Applications were reviewed according to an array of criteria: the cultural value and creativity of the activities proposed; capacity of tourism attractiveness; community development potential; human resource capacity; and commitment to work with research team during the project. Shortlisted proposals were also considered as a group to ensure a diversity of focus among the projects.

The open call and selection of the participating organizations occurred within the project, which meant that the actual participating practitioners could not be known in advance. The selected organizations include not-for-profit art and cultural associations, small entrepreneurial businesses, municipalities, regional development associations, and a few multi-organizational partnerships developed for this opportunity. Given the diversity of organizations – from the tourism and culture sectors as well as more general development associations and municipalities – the project brings together different skills, capacities, and strengths, but also differences of perspective and operating contexts.

The creative tourism projects designed and implemented within CREATOUR are varied, informed by the places that inspire and shape them and the relationships between people and place in these varied settings. For example, the pilot activities include workshops involving learning traditional arts and crafts as well as techniques of contemporary artistic expression inspired and informed by unique landscapes, local natural resources (e.g. marble), cultural heritage assets (e.g. Roman mosaics), and traditional activities (e.g. artisanal fishing, gastronomy, festivities, architecture) (for further details, see Duxbury, Silva, & Castro, 2019; CREATOUR, Citation2019).

For most participating organizations, creative tourism is a new addition to a portfolio of other tourism, craft, or artistic activities. They are looking to create a new creative tourism business or public initiative, often in conjunction with other work and activities they currently organize and conduct in a small community or rural area. Municipalities and regional development associations (and some independent entrepreneurs) are organizing local networks of creative tourism offers in collaboration with a range of independent individuals or organizations. Altogether, developing such enterprises and networks is much more complex than the delivery of simple workshops, taking time and ongoing attention, demanding more planning efforts, and needing reference models and possibly financial and other sources of support for start-up enterprises. This situation also brings higher expectations of the project’s researchers and the assistance that the project can bring to these entrepreneurs.

Re-positioning research–practice exchange and mobilization – in practice

By shifting real-time application and ‘knowledge mobilization’ from the borders of a research project and positioning them to be more central and integrated into the project design and management, researchers gain closer relations with practitioners and a greater awareness of ‘on-the-ground’ realities and challenges. This article focuses on three central strategies:

Developing spaces for ongoing knowledge exchange, fostering informal discussion, learning, and knowledge-building, in which researchers and participating organizations develop relationships and opportunities to interweave complementary types of knowledge;

Enabling practitioners to take on the role of co-researcher, involving participating organizations in research tasks and knowledge co-creation, changing the norms of researcher–participant relations and expanding upon the concept of reciprocity; and

Fostering researchers’ close attention to the application side of the project, requiring researchers to attend carefully to ‘application’ and ‘implementation’ as an integral part of the overall project and, potentially, to act ‘beyond’ their usual research work roles.

Developing spaces for ongoing knowledge exchange

The creation of communication spaces is especially important within a rural context where practitioners are geographically dispersed with a need for ongoing connectivity and access to knowledge (Ortiz, Citation2017). In the context of the project’s challenges of distributed geography – across four regions and involving many small cities and rural contexts – regular and multimodal forms of communication, in face-to-face fora and online, are imperative. For the ongoing exchange, mobilization, and building of knowledge to occur, a multiplicity of activities and communication channels were developed within CREATOUR to stimulate communication and dialog, with both formal and informal dimensions. These spaces include regularly scheduled IdeaLabs (regional and national face-to-face meetings, described further below), regional workshops, annual conferences, on-site visits, regular in-person and Skype-enabled conversations, a private Facebook group, a listserv, and other email correspondence. The intent is that through longitudinal and regular contact, collegial connections and trust are built up among participants.

The project’s activities are organized and presented as elements of a shared co-learning journey. From a research perspective, the longitudinal (over a period of three years) and close involvement of participants and researchers in the research-and-application processes integrated within CREATOUR sees the evolution of a type of para-ethnography (Islam, Citation2015; Vangkilde & Rod, Citation2015). The nature of the research–participant relationships emerging from this para-ethnographic methodology of investigating creative tourism in small city and rural contexts are varied, as would be expected given the large number of researchers (30) and their multi-disciplinary backgrounds as well as the diversity of practice settings (geographically and institutionally) and pilot initiatives. This intentional diversity enriches the CREATOUR project with a plurality of perspectives and insights, while simultaneously challenging attempts at synthesis. Researchers are confronted with both complementary and conflicting perspectives, observations, and interpretations to be discussed and negotiated within the project – a rich though challenging base from which to operate.

A total of 24 regional IdeaLabs and 3 national IdeaLabs are organized within the CREATOUR project lifespan, bringing together project researchers and participating organizations for 1–2 day working meetings.Footnote2 The IdeaLabs provide regular points of face-to-face contact, providing interactive exercises to support content development, sessions to discuss issues and challenges – and positive surprises, and activities to articulate linkages between the pilot projects and their place and to encourage stronger relations between culture, tourism, and local/regional development. Within the IdeaLabs, participant organizations present and actively discuss their projects (including their aspirations and doubts) and share developments in implementation, while researchers bring in complementary research findings, contextual information, ideas, and reflections to inform these plans and actions.

The activities organized within the IdeaLabs are adapted to the time period they are held in the course of the project and to the needs of the pilots. For example, initial IdeaLabs included a design-inspired cultural mapping exercise to contextualize and help ‘make visible’ the cultural and natural resources of the places where the pilots are based and from which they are inspired (). This activity served as background for thinking about how the pilot projects are embedded in their locales and in developing strategies for linking creativity to place. Idea generation/refinement sessions complemented this work, probing and elaborating business, communication, and community impact plans from the initial pilot project ideas proposed. Subsequent IdeaLabs have focused on collaboratively reviewing implementation tests and experiences, reflecting on surprises and lessons learned, presenting and sharing collectively gathered information from the participating organizations as well as from outside sources (to consider individual experiences within wider contexts), and planning changes for the future.

Figure 4. IdeaLab cultural mapping presentation session in Coimbra, Centro region, Portugal, Spring 2018, in which participating organizations presented 12 objects evocative of their place inspired by a framework of adjectives (participants pictured). Source: K. S. Alves (used with permission).

The meetings are structured to allow for multiple informal discussions, as well as more ‘formal’ presentation and group feedback sessions. For example, during the process of working through activity-based exercises such as developing a canvas model business plan, creating a map of strengths and weaknesses, or a project’s alignment with creative tourism principles, pilot-participants and researchers informally discuss the information being developed, with researchers dropping by the organizations' posters being developed and discussing ideas as well as responding to questions and doubts (). Later on, each pilot-participant presents their poster to all IdeaLab participants, which is then commented on by both researchers and pilots. These open and lively discussions frequently provide additional ideas and suggestions for the participating organizations to consider when elaborating their initiative, as well as additional themes for research.

Figure 5. IdeaLab canvas model development and mentoring session in Coimbra, Centro region, Portugal, Spring 2018 (researchers and organizational participants pictured). Source: K. S. Alves (used with permission).

Although it takes time for researchers and practitioners to understand each other and their various operating contexts – a challenge keenly felt when dealing with 40 diverse participating organizations – close and ongoing contact reveals the differing working goals and imperatives of project participants as well as inherent contradictions between research and practice, such as researchers’ focus on presenting and writing research articles while operational sustainability is top of mind for the practitioners; differing time scales for developing and reporting results; and different perceptions of importance for different tasks (such as distributing questionnaires or conference presentations), among other dimensions. Furthermore, differences among practitioners’ contexts and needs are also revealed, such as the operating issues and priorities of a municipality versus that of an independent entrepreneur.

In the process of designing and implementing the IdeaLabs, challenges have arisen related to the maximization of the face-to-face encounters in the face of multiple and diverse priorities, and more generally addressing an emergent need for a temporal ‘balancing’ between ‘time together’ and ‘time alone’ spent planning and implementing the pilot activities:

Maximization of face-to-face encounters

Time limitations of face-to-face interaction, and management of the schedule to maximize both research and practitioners’ needs for information gathering and exchange, as well as to incorporate informal time for networking, continues to be challenging. With multiple competing priorities, there are no simple prioritization systems and each meeting is carefully prepared to balance the needs of research and practitioners. Compromises in time allocations have occurred, for example, to enable formal, regularly held one-on-one interviews with each participating organization rather than to allocate additional time to foster networking and discussions among the organizations to discuss inter-organizational cooperation possibilities. It is also important to note that the dynamics of each regional meeting differ, with impromptu discussions addressing emerging issues and concerns, which can alter the pre-planned agenda. Enabling this flexibility and responsiveness is imperative in order to address questions and concerns, to progress relations among researchers and practitioners, and to continue to advance the overall project.

Balancing ‘time together’ with ‘time alone’

The IdeaLabs were conceived and designed as a central element within multiple channels and spaces for communication. The organization of three intensive project meetings (IdeaLabs) annually in addition to annual site-visitsFootnote3 and interviews, and regular electronic communications (via email, a listserv, and a private FaceBook group) was originally felt to be sufficient to maintain connections with participating organizations. However, in practice, a desire for additional regular communications was expressed. Some participating organizations felt there was insufficient individualized follow-up with organizations following each intense IdeaLab, with the consequence that the motivation and energies stirred up in these meetings dissipates afterwards, when the organizations feel ‘alone’ again. This perceived need for additional, individualized follow-up was not anticipated in the original project design. Some research centers responded by organizing additional seminars and meetings in their regions, then in response to ongoing pilot calls for even more regular contact and support from researchers in the project, regular in-person and Skype conversations (depending on geographic proximity) were implemented to support further connectivity and exchanges among pilot-participants and researchers. However, organizing monthly meetings between researchers and pilots to discuss developments and plans and to provide support and constructive feedback has become a challenging endeavor in many cases. Both researchers and practitioners are busy with multiple obligations and coordinating schedules, cancelations, and subsequent rescheduling has been difficult. Consequently, the timeliness and regularity of connections has suffered.

Beyond these operational challenges, an emerging concern is researchers’ limited use (to date) of the practice-based knowledge shared within the activities and discussions in research publications. The exchanges among researchers and practitioners have been central to the project’s operations and to building the knowledge base of all involved in the project. The knowledge, observations, and insights shared within the IdeaLabs are documented through posters, researchers’ notes, photographs, and video recordings of presentations. As well, an ‘instant report’ of each IdeaLab is developed during each event that contains key points and images from all activities and discussions, which is presented at the end of the event and made available to all project participants for reference following. This knowledge-sharing and documentation has been invaluable to inspire and inform research topics, to articulate issues to address in practice, and to share good practices. Practitioners’ insights have also been used to inform the development of book chapters reflecting on the development of the project, to highlight the needs and issues of the participating organizations, and to inform the general management of the project. However, to date, researchers have made only limited use of the practice-based knowledge and insights gained in these meetings in their academic journal articles.

We acknowledge that the researcher–practitioner exchanges are, by their nature, messy and largely open-ended, but the IdeaLab sessions can be compared to interactive focus groups. However, researchers have tended to incorporate methods such as (additional) interviews within the journal articles they have developed, to better ensure a clear correspondence between academic conceptual frameworks and research findings. In part, this is due to the characteristics of academic publishing which prefers, for example, clearly defined and more traditional research methodologies, such as standardized interviews, as the basis of data collection. In part, this situation also stems from a greater need to know how to effectively bridge practice-based insights and knowledge with academic interests, and the greater time required to sort through multiple sources of documentation and wide-ranging discussions, and relate it to recognized conceptual frameworks and theories. This seems to indicate that while practice-based insights can provide important advancements in understanding development processes and ‘front-line’ observations and insights not otherwise available, the nature of this knowledge may be different from what researchers aim to write for research journals and that some ‘misalignment’ is present in this process. The situation also suggests that research publications may not be the most suitable outlets for articulating and bringing this knowledge forward, that a different communication platform is needed as a ‘bridging’ mechanism, and that integrating practice-based knowledge into research journals may be a subsequent activity.

Encouraging hybrid roles: co-researching and ‘going beyond’ research

With a project that is intentionally trying to foster different relations between research and practice, the ‘traditional’ roles, perspectives, and practices of research are also intentionally disturbed: hybrid roles have been encouraged as practitioners become ‘co-researchers’ and researchers are asked ‘go beyond’ typical research activities to support the participating organizations. The positioning of practitioners as co-researchers aims to equalize power differentials within the project, contributes to the recognition and valuation of practice-based research, and foregrounds the desirability to weave together different types of knowledge. At the same time, researchers are called upon to explicitly consider and respond to the needs of the participating organizations, challenging the traditional researcher-as-observer role. Altogether, this hybridity of roles means that the research design practically and conceptually responds to the need to better link tourism research and practice, on an ongoing basis, and strives to represent and address practitioners’ challenges. The implications of this ‘disruptive’ context and ‘new’ relationship is that the researcher and participant-practitioner roles are problematized and hybrid researcher–practitioner roles emerge, the liquidity of which results in dynamic knowledge production but can often be confusing for the parties involved. The practice of these roles is an emergent process.

Enabling practitioners to take on the role of co-researcher

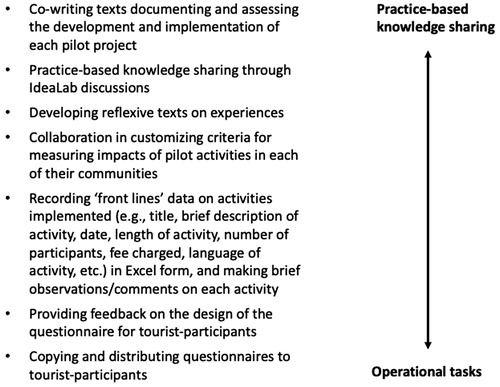

Within CREATOUR, practitioners (from the participating organizations) are called upon to be co-researchers (see ). On an operational level, they share in research tasks, such as distributing and managing the completion of questionnaires by their visitor-participants and maintaining statistics on the number of workshops/activities organized, number of participants, brief observational notes, and so forth. On a research design level, they provided input into the design of a visitor-participant questionnaire and are co-developing impact assessment criteria, working with a research team to select organization-specific criteria that align with the objectives of each organization’s initiatives. The participating organizations’ insights and experiences conceiving and steering developments both ‘on the ground’ and ‘in motion’ during the duration of the project are akin to practice-based research providing knowledge through practice, and are making important contributions to informing the field of creative tourism in terms of ‘supply’ development. In this vein, discussions among researchers and practitioners are moments of co-learning through sharing different perspectives and knowledges. For example, in the autumn IdeaLabs, the participating organizations’ observations and reflections on summer-season activities are presented, discussed, and documented as complementary insights into the summer’s activity implementation experiences, alongside the visiting researchers’ observations and field notes.

While the overall structure of this approach has been productive, some issues have arisen in the adoption of the co-researcher role by some practitioners. For example, some participating organizations had problems distributing questionnaires to creative tourists largely due to time constraints and logistics issues at the event they organized but also due, in part, to viewing this task as something ‘extra’ rather than integrated into the activity plans. These organizations saw this as the researcher’s task, with themselves only responsible for organizing the event. In other situations of co-creating research tools, communication difficulties between researchers and practitioners led to varied engagement in following up after a group session. In such cases of more advanced input into research instruments (for example, customized impact criteria assessment grids), more personalized approaches to involving each practitioner may be needed, such as jointly working on these materials on-site, rather than leaving this to be completed as ‘follow-up’ work. These issues suggest that further training and discussion relating to research–practice relations and the project’s hybrid roles, for both researchers and practitioners, would have clarified expectations, offered more operational knowledge and support, and helped decrease the uncertainties of acting in these new situations.

Fostering researchers’ close attention to application (or researchers’ actions beyond research)

Collaborative research brings researchers into a more reflexive position where intensive, ongoing reflection is needed on the consequences faced by all parties involved, but a research-and-application project may go beyond this. It can also entail a series of actions beyond those that can be understood as ‘research’ activities and methodologies, especially when pilots need more in-depth mentorship and training. With the continuance and sustainability of the pilot projects very much top of mind, the hybrid project structure demands the incorporation of activities and methods that specifically address the practice-related issues and concerns that arise in the processes of implementation. In this ‘practice-foregrounded’ context, research-and-application projects require researchers (who adopt an engaged scholarship approach to knowledge creation) to attend to more-than-research aspects of the global project, to deeply listen and respond to practitioner needs and expectations in regards to assisting the ‘practice’ side of the project, and to add to or adjust operational actions to attempt to address these needs.

As researchers’ roles move beyond that of a ‘traditional’ researcher whose main aim is to gather and analyze data, they actively practice a form of ‘extreme’ reciprocity in terms of making concerted efforts to develop, exchange, and mobilize knowledge within a practice- and application-based research setting, in the process extending, disrupting, and challenging ‘traditional’ research–practice interactions. Some successful practices in this vein include researchers adopting a mentoring role for participant organizations, helping them develop their business ideas during IdeaLabs, regularly posting tourism marketing news on a shared social media page, and organizing presentations (involving researchers and participating organizations) at the national tourism trade fair. Furthermore, researchers began to learn to alter the way in which they presented their knowledge, interpreting data collected during the project (e.g. obtained through questionnaires and on-site interviews) in a format that would be useful to the practitioners, aiming to provide ‘practice-actionable’ information that may be valuable to them in the long run. Such ‘extreme’ reciprocity acts provide indications of ways in which research power dynamics can be equalized and point towards the future emergence of hybrid researcher–practitioner roles. Such roles appear to be essential and integral to striving towards more egalitarian research relationships that result in better representation and investigation of contemporary tourism phenomena.

However, altering traditional boundaries and ‘comfort zones’ to develop closer research–practice relationships is an ongoing and challenging practice. Within IdeaLab sessions and other meetings, spaces have been organized for expressing and discussing participants’ expectations of the project, whether they are being addressed, and how researchers might subsequently try to fulfill these expectations to their best ability. While the very nature of research-and-application projects means that practitioners enter the project with business-development related expectations, challenges can emerge in meeting these. In the project discussed here, since the level of development is so varied among the participating organizations’ pilot initiatives, expectations also vary, ranging from start-up mentorship needs, to ‘bringing more clientele to them’, to more nuanced expectations of ‘constructing a network of partners and complementary offers’, among an array of other topics.

We have found that participating organizations’ expectations of a range of pragmatic development assistance and support has been difficult for the researchers to address, with many business and marketing consultancy expectations beyond the expertise of the researchers involved in the project, and highlighting an important gap in forging this relationship. This challenging situation is a function of a combination of practitioners’ high and varied expectations of the project, a lack of researchers’ expertise and capacities for the types of training required, limited experience in mentorship roles involving practitioners, and project design constraints (e.g. time limitations and resource inflexibility to directly address the greater-than-anticipated start-up support needs).Footnote4 This suggests heightened consideration of addressing the emergent pragmatic needs of participating practitioners, carefully managing expectations while also remaining flexible to address emerging issues and opportunities, providing greater training of researchers on knowledge transfer and mentorship techniques, and including dedicated partners or funding to provide pragmatic training sessions within such a project.

Conclusions

We believe significant advances in understanding creative tourism development in small cities and rural areas are emerging through this research-and-application project, through embracing the practice of engaged scholarship, blurring the traditional boundaries between researchers and practitioners, and foregrounding the importance of practice-based knowledge. Furthermore, within the complex context of this project, questions have arisen of how reciprocal relationships can be maintained within a research-and-application project, how the practice side of the project can be attended to, and how the knowledge co-created in this process can benefit both researchers and practitioners. The reflexive process method employed on the lived experience of being a researcher within this research-and-application project has highlighted the complexity of this experiment and the need for researchers to know more about how to effectively bridge practice-based insights and knowledge with academic interests and contexts. While there is no simple formula for fostering closer research–practice relations, in this concluding section, we synthesize key findings from the three central strategies implemented within the CREATOUR project. We close with a few insights from others involved in collaborative research that reassure us that the challenges we have faced and have aimed to address are an integral part of collaborative processes more broadly.

Key findings

Developing spaces for ongoing knowledge exchange

A multiplicity of activities and communication channels were developed within CREATOUR to stimulate communication and dialog, such as IdeaLabs, regional workshops, annual conferences, on-site visits, regular in-person and Skype-enabled conversations, a private Facebook group, a listserv, and email correspondence. The application of these multiple approaches highlighted that it takes time for researchers and practitioners to understand each other and their various operating contexts, and to build trust. This explicit recognition of time and process in relationship-building is essential in order for participant organizations to feel their needs are being taken seriously and attended to, for researchers to feel less pressured by time restrictions, and for the overall research-and-application process to be more effective. Within a multi-channel communications environment, communication preferences and complementarities must be strategically used to address a temporal ‘balancing’ between participants’ ‘time together’ and ‘time alone’ working independently on different activities. The careful design of face-to-face meetings (of individuals and as groups) is imperative to illuminate and advance this relationship-building and knowledge-sharing process. In the face of multiple and diverse priorities, contents and approaches/formats, different perspectives and values, and networking possibilities inherent in any activity must be considered jointly. Overall, an ongoing spirit of care, flexibility, and responsiveness is vital in order to address emerging questions, issues, and concerns; to foster relations among researchers and practitioners over time; and to continue advancing the overall project.

Enabling practitioners to take on the role of co-researcher

The positioning of practitioners as co-researchers aimed to equalize power differentials within the project, contribute to the recognition and valuation of practice-based research, and foreground the desirability to weave together different types of knowledge. Overall, this approach emphasized that the observations, experiences, and practice-based knowledge of the practitioners ‘on the front lines’ (planning and implementing creative tourism pilot projects, interacting with tourists, and evaluating and reflecting on these experiences) were essential and central aspects of researching creative tourism development in small cities and rural areas. While the overall structure of this approach has been productive, some issues have arisen in the operational adoption of some tasks by some practitioners, and the design of some collaborative exercises by researchers. The issues encountered suggest that further training and discussion about the intentionally designed ‘practitioner as co-researcher’ role, for both researchers and practitioners, would have clarified expectations, offered further operational knowledge and support, and helped decrease the uncertainties of this new situation.

Fostering researchers’ close attention to the application side of the project

Many researchers adopted an engaged scholarship approach to knowledge creation, attending to aspects beyond the project’s research dimension by deeply listening and responding to practitioner needs and expectations as well as conducting operational actions to attempt to address practitioner needs. However, this situation also caused tension because many business and marketing consultancy expectations arose which were often beyond the competencies and areas of expertise of the researchers involved in the project. While researchers aimed to address pilots’ expectations and needs, they struggled to adequately address all desirable actions and consultancy/mentorship interventions. As researchers were challenged to stretch beyond the ‘usual’ researcher role, they were confronted with issues of self-assessing their competency and capacity to take on some of these ‘expected’ extended actions. For researchers, this led to tensions as well acts of personal growth and transformation as they moved towards adopting a hybrid ‘researcher–consultant’ role.

The reflexive process undertaken for this article has highlighted that juxtaposing and resolving researchers’ focus on presenting and writing research articles and practitioners’ priority for operational sustainability is a central issue in the productive design and management of research–practice relationships. Challenges in sharing research data quickly with practitioners as well as integrating shared practice-based knowledge into research publications suggest that a customized knowledge/communication platform may be useful as a ‘bridging’ mechanism between practice-based and academic knowledge systems, one that values, articulates, and shares various knowledges and perspectives in a manner that aims to respond to the knowledge needs of both researchers and practitioners. Dedicated resources and expertise must be devoted to this process for its effective realization.

In closing, revisiting the question, ‘Why has the task of closer research–practice collaboration been so challenging to achieve?’ the following remarks on collaborative practice resonate strongly with us regarding our experiences and reflections:

It challenges us to trust.

It is often surprising.

It is often difficult.

Sometimes there is tension.

It takes time.

It demands personal growth.

It requires acknowledgment of others.

It asks us to question our own points of view.

It thrives in the in-between spaces.

There is no one way.

It is an act of transformation. (Maddox, Citation2019)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank CREATOUR researchers and participants for their precious contributions, and the anonymous reviewers for their inspirational and useful critiques and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nancy Duxbury

Nancy Duxbury, PhD, is a Senior Researcher and Co-coordinator of the Cities, Cultures and Architecture Research Group at the Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra. She is Principal Investigator of CREATOUR, and a member of the European Expert Network on Culture. Her research has examined culture in local sustainable development; culture-based development models in smaller communities; and cultural mapping, which bridges academic inquiry, community practice, and artistic approaches to understand and articulate place. Recent edited books: Animation of Public Space through the Arts: Toward More Sustainable Communities (Almedina 2013), Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry (Routledge 2015), Culture and Sustainability in European Cities: Imagining Europolis (Routledge 2015), Cultural Policies for Sustainable Development (Routledge, 2018), Artistic Approaches to Cultural Mapping: Activating Imaginaries and Means of Knowing (Routledge, 2019), and A Research Agenda for Creative Tourism (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019). She was born in Canada, and lived on both the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts of the country before moving to Portugal in 2009. She currently splits her time between Coimbra and São Miguel Island, Azores.

Fiona Eva Bakas

Fiona Eva Bakas, PhD, is a critical tourism researcher with international teaching experience. She holds a PhD in Tourism (Otago University, 2014), has 20 years of varied work experience (corporate and academic), and is currently a contracted postdoctoral researcher in a nation-wide project on creative tourism in rural areas and small cities (CREATOUR), at the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra, Portugal. Fiona is a member of research groups: CCArq (Coimbra), GOVCOPP (Aveiro), and ETEM (University of the Aegean). Her research interests are: creative and cultural tourism, gender in tourism labour, qualitative methodologies, cultural mapping, handicrafts, entrepreneurship, rural tourism, and ecotourism .

Cláudia Pato de Carvalho

Cláudia Pato de Carvalho, PhD, is a permanent researcher at the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra under the post-doctoral fellowship (2013–2018) and under the ARTERIA project (operation no. CENTRO-07-2114-FEDER-000022, Portugal 2020). Arteria is an action-research project in collaboration with O Teatrão (Oficina Municipal do Teatro, Coimbra) that aims at the development of a cultural programing network in the Centro Region (Portugal) and the creation of artistic intervention projects in eight cities of this Region. She completed her PhD in Sociology, with a specialization in Sociology of Culture, Knowledge and Communication, at the Faculty of Economics of the University of Coimbra in October 2010, in collaboration with the Center for Reflective Community Practice (DUSP, MIT). Between 2010 and 2018, she established a European network in the field of arts education and disadvantaged communities, with several projects approved under the Youth in Action Program and ERASMUS+.

Notes

1 We acknowledge that this article is written from the researchers’ perspective, and that a complementary examination of the practitioners’ perspectives is warranted. This, however, is beyond the scope of the current article and will be the focus of subsequent investigation within the research-and-application project.

2 Each year, two regional IdeaLabs take place in each project region (in Winter/Spring and Autumn), with an annual national IdeaLab organized with the annual conference (May 2017, June 2018, and October 2019).

3 The on-site visits, held during the time of selected creative tourism implementations, offer moments for participant observation, documentation, and in situ interviews with the pilot-organizers, and occur (at least) annually with all pilots. These events provide an opportunity for the researcher to ‘live’ the creative tourism project and have an immersive experience which allows for a better understanding of the participant organization, its product, and its reception by visitors. Simultaneously, on-site visits provide the opportunity for participating organizations and others to ask any questions they may have about the CREATOUR project.

4 Sometimes even ‘best’ intentions to address these conditions do not work out in the end. For example, after a series of IdeaLab meetings where participating organizations strongly asked for more help with marketing their products, researchers attempted to address these needs by organizing a digital marketing bootcamp weekend to be presented by a well-regarded communications consultant/trainer working in the cultural and tourism sectors. However, in the end, even though the program was customized to their needs and the price arranged was very competitive, practitioners did not sign-up for the bootcamp, with some expressing that it should have been offered ‘within the project’ rather than ‘in addition’ to the regular meetings – a reminder of the messiness and uncertainty of these efforts.

References

- Anderson, C. R., & McLachlan, S. M. (2016). Transformative research as knowledge mobilization: Transmedia, bridges, and layers. Action Research, 14(3), 295–317. doi:10.1177/1476750315616684

- Anderson, W., & Sanga, J. J. (2018). Academia–industry partnerships for hospitality and tourism education in Tanzania. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 31(1), 34–48. doi:10.1080/10963758.2018.1480959

- Ateljevic, I., Harris, C., Wilson, E., & Collins, F. L. (2005). Getting ‘entangled’: Reflexivity and the ‘critical turn’ in tourism studies. Tourism Recreation Research, 30(2), 9–21. doi:10.1080/02508281.2005.11081469

- Bakas, F. E. (2017). ‘A beautiful mess’: Reciprocity and positionality in gender and tourism research. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 33, 126–133. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2017.09.009

- Bakas, F. E., Duxbury, N., & de Castro, T. V. (2018). Creative tourism: Catalysing artisan entrepreneur networks in rural Portugal. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(4), 731–752. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-03-2018-0177

- Beech, N., MacIntosh, R., & MacLean, D. (2010). Dialogues between academics and practitioners: The role of generative dialogic encounters. Organization Studies, 31(9-10), 1341–1367. doi:10.1177/0170840610374396

- Beaulieu, M., Breton, M., & Brousselle, A. (2018). Conceptualizing 20 years of engaged scholarship: A scoping review. PLoS One, 13(2), e0193201. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193201

- Cheek, J., Lipschitz, D. L., Abrams, E. M., Vago, D. R., & Nakamura, Y. (2015). Dynamic reflexivity in action: An armchair walkthrough of a qualitatively driven mixed-method and multiple methods study of mindfulness training in schoolchildren. Qualitative Health Research, 25(6), 751–762. doi:10.1177/1049732315582022

- Cockburn-Wootten, C., McIntosh, A. J., Smith, K., & Jefferies, S. (2018). Communicating across tourism silos for inclusive sustainable partnerships. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(9), 1483–1498. doi:10.1080/09669582.2018.1476519

- CREATOUR. (2019). CREATOUR pilots and projects. Coimbra: Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra.

- Diver, S. W., & Higgins, M. N. (2014). Giving back through collaborative research: Towards a practice of dynamic reciprocity. Journal of Research Practice, 10(2), M9.

- Duxbury, N. (Forthcoming). Catalyzing creative tourism in small cities and rural areas in Portugal: The CREATOUR approach. In K. Scherf (Ed.), Creative tourism and sustainable development in smaller communities. Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

- Duxbury, N., & Richards, G. (2019a). Towards a research agenda for creative tourism: Developments, diversity, and dynamics. In N. Duxbury & G. Richards (Eds.), A research agenda for creative tourism (pp. 1–14). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Duxbury, N., & Richards, G. (2019b). Towards a research agenda in creative tourism: A synthesis of suggested future research trajectories. In N. Duxbury & G. Richards (Eds.), A research agenda for creative tourism (pp. 182–192). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Duxbury, N., Silva, S., & Castro, T. V. (2019). Creative tourism development in small cities and rural areas in Portugal: Insights from start-up activities. In D. A. Jelinčić & Y. Mansfeld (Eds.), Creating and managing experiences in cultural tourism (pp. 291–304). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

- Estabrooks, C. A., Norton, P., Birdsell, J. M., Newton, M. S., Adewale, A. J., & Thornley, R. (2008). Knowledge translation and research careers: Mode I and mode II activity among health researchers. Research Policy, 37(6-7), 1066–1078.

- Ferlie, E., Crilly, T., Jashapara, A., & Peckham, A. (2012). Knowledge mobilisation in healthcare: A critical review of health sector and generic management literature. Social Science and Medicine, 74(8), 1297–1304. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.042

- Finlay, L. (2002). Negotiating the swamp: The opportunity and challenge of reflexivity in research practice. Qualitative Research, 2(2), 209–230. doi:10.1177/146879410200200205

- Freeman, J. (2010). Blood, sweat & theory: Research through practice in performance. Faringdon: Libri Publishing.

- Greenhalgh, T. (2010). What is this knowledge that we seek to “exchange”? The Milbank Quarterly, 88(4), 492–499. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00610.x

- Greenhalgh, T., & Wieringa, S. (2011). Is it time to drop the 'knowledge translation' metaphor? A critical literature review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104(12), 501–509. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2011.110285

- Hallin, C. A., & Marnburg, E. (2008). Knowledge management in the hospitality industry: A review of empirical research. Tourism Management, 29(2), 366–381. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.02.019

- Hart, A., Davies, C., Aumann, K., Wenger, E., Aranda, K., Heaver, B., & Wolff, D. (2013). Mobilising knowledge in community − university partnerships: What does a community of practice approach contribute? Contemporary Social Science, 8(3), 278–291. doi:10.1080/21582041.2013.767470

- Hope, S. (2016). Bursting paradigms: A colour wheel of practice-research. Cultural Trends, 25(2), 74–86. doi:10.1080/09548963.2016.1171511

- Islam, G. (2015). Practitioners as theorists: Para-ethnography and the collaborative study of contemporary organizations. Organizational Research Methods, 18(2), 231–251. doi:10.1177/1094428114555992

- Jeannotte, M. S., & Duxbury, N. (2015). Advancing knowledge through grassroots experiments: Connecting culture and sustainability. Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society, 45(2), 84–99. doi:10.1080/10632921.2015.1039739

- Kara, H. (2015). Creative research methods in the social sciences: A practical guide. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Singapore: Springer

- Lassiter, L. E. (2005). The Chicago guide to collaborative ethnography. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press.

- Leavy, P. (2015). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Maddox, D. (2019). Introduction. In D. Maddox (Ed.), What I mean when I talk about collaboration. What is a specific experience collaborating on a project with someone from a different discipline or “way of knowing”? New York: The Nature of Cities. Retrieved from https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2019/02/28/mean-talk-collaboration-specific-experience-collaborating-project-someone-different-discipline-way-knowing/?utm_source=The+Nature+of+Cities+Newsletter&utm_campaign=361d013524-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_03_10_09_08&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_65cc822135-361d013524-1402919

- Nelson, R. (2013). Practice as research in the arts. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nilsson, P. Å. (2007). Stakeholder theory: The need for a convenor. The case of Billund. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(2), 171–184. doi:10.1080/15022250701372099

- Oborn, E., Barrett, M., & Racko, G. (2013). Knowledge translation in healthcare: Incorporating theories of learning and knowledge from the management literature. Health Organization and Management, 27(4), 412–431.

- OECD. (2014). Tourism and the creative economy. Paris. OECD.

- Olsen, V. (2011). Feminist qualitative research in the millenium’s first decade. In N. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of tourism studies (pp. 129–146). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Ooi, C.-S. (2013). Tourism policy challenges: Balancing acts, co-operative stakeholders and maintaining authenticity. In M. Smith & G. Richards (Eds.), Routledge handbook of cultural tourism (pp. 67–74). New York, NY: Routledge

- Ortiz, J. (2017). Culture, creativity and the arts: Building resilience in northern Ontario (Doctoral thesis). University of the West of England, UK.

- Palinkas, L. A. (2010). Commentary: Cultural adaptation, collaboration, and exchange. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(5), 544–546. doi:10.1177/1049731510366145

- Pillow, W. (2003). Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(2), 175–196. doi:10.1080/0951839032000060635

- Richards, G. (2018). Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.03.005

- Richards, G., & Raymond, C. (2000). Creative tourism. ATLAS News, no. (23), 16–20.

- Ryan, C. (2001). Academia–industry tourism research links: States of confusion. The Martin Oppermann Memorial Lecture 2000. Pacific Tourism Review, 5(3–4), 83–95.

- Santos, B. D S. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review, 30(1), 45–89.

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). (2018). Definition of terms – Knowledge mobilization. Retrieved from http://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/programs-programmes/definitions-eng.aspx#km-mc

- Trainor, A., & Bouchard, K. A. (2013). Exploring and developing reciprocity in research design. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(8), 986–1003. doi:10.1080/09518398.2012.724467

- Tribe, J., & Liburd, J. J. (2016). The tourism knowledge system. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 44–61. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.011

- Van de Ven, A. (2007). Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research. New York, NY. Oxford University Press.

- Van de Ven, A., & Johnson, P. E. (2006). Knowledge for theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 802–821. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.22527385

- Vanderlinde, R., & van Braak, J. (2010). The gap between educational research and practice: Views of teachers, school leaders, intermediaries and researchers. British Educational Research Journal, 36(2), 299–316. doi:10.1080/01411920902919257

- Vangkilde, K. T., & Rod, M. H. (2015). Para-ethnography 2.0: An experiment with the distribution of perspective in collaborative fieldwork. Paper presented at Research Network for Design Anthropology, seminar 3: Collaborative Formation of Issues, January 22–23, 2015. Retrieved from https://kadk.dk/sites/default/files/14_paper_kasper_tang_vangkilde_morten_hulvej_rod.pdf

- Walsh, J. P., Tushman, M. L., Kimberly, J. R., Starbuck, B., & Ashford, S. (2007). On the relationship between research and practice: Debate and reflections. Journal of Management Inquiry, 16(2), 128–154. doi:10.1177/1056492607302654

- Walters, G., Burns, P., & Stettler, J. (2015). Fostering collaboration between academia and the tourism sector. Tourism Planning & Development, 12(4), 489–494. doi:10.1080/21568316.2015.1076596

- Ward, V. (2017). Why, whose, what and how? A framework for knowledge mobilisers. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 13(3), 477–497. doi:10.1332/174426416X14634763278725

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilson, E., & Hollinshead, K. (2015). Qualitative tourism research: Opportunities in the emergent soft sciences. Annals of Tourism Research, 54, 30–47.