Abstract

Disruption and creativity are the two ideas around which we challenge and contribute to dismantling white, ‘western’, neoliberal hegemonic social narratives and ideologies in qualitative tourism methodologies. In tourism studies in general, and tourism geography in particular, the last decade has witnessed an emphasis on qualitative methodological research, both in terms of the topics addressed and the types of methodological tools. In many ways, this legitimisation of qualitative work mirrors developments in other areas such as human geography, sociology and anthropology. Explorations in this Special Issue contribute critical understandings of the responsibility of tourism research to be disruptive first before it can engender progress and transformation within and outside of our field. Authors debate in more depth how tourism studies can offer multidimensional, multilogical and multiemotional, methodological approaches to tourism research. This Special Issue contributors tackle the ways in which research methodologies can be creative and disruptive to the seemingly prevalent narratives within tourism studies. To further expand tourism methodologies, authors have engaged in debates about deep reflexivity, subjectivities, and dreams; messy emotions in auto-ethnographic accounts of fieldwork; ‘motherhood capital’ accessing Inuit communities; collective memory work in tourism research and pedagogy; ethnodrama and creative non-fiction; linguistic narrative analysis, and serious gaming, amongst others.

摘要

颠覆和创造是我们挑战并致力于拆解定性旅游方法中以白色人种、“西方的”、新自由主义霸权主导的社会叙事和意识形态的两种观点。在一般的旅游研究中, 特别是在旅游地理学中, 过去十年见证了对定性方法研究的重视, 无论是在所讨论的主题还是在方法运用工具的类型上。在许多方面, 定性研究的合法化反映了人文地理学、社会学和人类学等其他领域的发展。本专刊进行的一系列探索有助于批判性地理解旅游研究的责任, 旅游研究首先要具有颠覆性, 进而才能引发我们研究领域内外的进步与转型。作者们更深入地讨论了旅游学术成果如何为旅游研究提供多维度、多逻辑、多情感的方法论研究取经。本期特刊作者探讨了研究方法论对旅游研究中貌似流行的叙事进行创造性和颠覆性研究的方式。为了进一步扩展旅游方法, 作者们参与了诸如深度反思、主观性、梦想、田野自我民族志叙述中的混杂情绪、进入因纽特社区的“母职资本”、 旅游研究与教学中的集体记忆 、人种志戏剧与创新性的纪实小说、语言学叙述分析以及严肃博弈等一系列论辩。

Qualitative methodologies into the spotlight

Creative and Disruptive Methodologies in Tourism Studies special issue editors and authors advocate challenging and creatively disrupting conventional methodological approaches. In our Special Issue we provide space and encouragement for debates on creating novel forms of knowledges via exploration of creative methodologies. This will enable tourism studies to expand its critical considerations of qualitative methodologies in ways that shake and subvert the established linear and sometimes entrenched status-quo of generating tourism knowledges.

Qualitative tourism methodologies experience a surge in interest from tourism researchers, a thrust into the research spotlight, and are ripe for further robust and creative debates. This is also evidenced in the substantial interest authors showed in this Special Issue as we received over 70 abstracts which eventually translated into 16 papers dedicated solely to exploring how and in what ways tourism researchers can shake up the qualitative status quo. It was contended, about two decades ago, that the majority of tourism researchers still regarded qualitative methods as the soft, non-scientific other to quantitative, rigorous tools (Phillimore & Goodson, Citation2004). Following this claim, debates ensued regarding the use of qualitative methodologies in tourism research especially within, what is identified as, the critical turn in tourism studies (Ateljevic, Morgan, et al., 2007; Ateljevic, Pritchard, et al., 2013).

We maintain that in tourism studies, akin to human geography, tourism researchers have moved from times when our work, from doctoral theses to peer reviewed articles, needed to be prefaced with explanations of choosing a qualitative versus quantitative methodology. All three editors of this Special Issue having conducted our doctoral research in the early/mid-2000s, we remember all too well having to legitimise our choice of qualitative over quantitative methods, or being advised to write our ethnographies in third person singular. Bygone are those days, we argue, and we now experience debates within qualitative methods calling for robust considerations of co-creative and experiential methods (Nunkoo et al., Citation2020; Wilson & Hollinshead, Citation2015; Wilson et al., Citation2020).

Our positionalities are that of three women in our late-30s, two of us originating in eastern Europe, Bulgaria and Romania respectively, and one in south-central Europe, Italy to be precise. We operate from an Anglophone centre, being based at English universities, yet in our works, comparable to authors in this special issue, we critique and aim to disrupt white, ‘western’, post/colonial underpinnings of tourism knowledge production.

The papers in this Special Issue debate in more depth how tourism studies can offer multidimensional, multilogical and multiemotional, ontological, epistemological and methodological approaches to research. As such, they tackle the ways in which research methodologies can be creative and disruptive to the seemingly prevalent narratives within tourism studies. To further expand tourism methodologies authors have engaged in debates about deep reflexivity, subjectivities, and dreams; messy emotions in auto-ethnographic accounts of fieldwork; ‘motherhood capital’ accessing Inuit communities; collective memory work in tourism research and pedagogy; ethnodrama and creative non-fiction, amongst others.

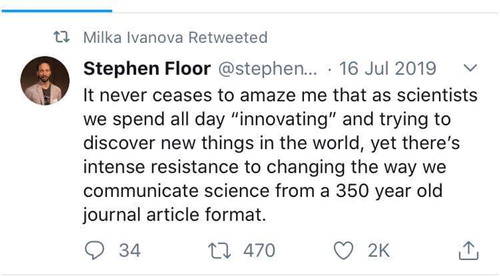

To bring these authors’ voices along in our Editorial we name each contributor and each paper in full. We will, however, be remiss in not acknowledging the shortcomings of this Special Issue. Thus, as we advocate for non-linear approaches to knowledge production, we still seem to support the linear format of academic journal article as primary tool of dissemination of our work. In this Editorial, and the following papers, we follow an entrenched 350-year old journal article format, albeit with some creative dis-ruptions in some places.

This was the story of our Special Issue papers and editorial when we finalised most everything in December 2019/January 2020, before the Covid-19 pandemic has hit the world. This means that in our Special Issues we did not have the possibility to capture the ongoing impacts that such a global crisis exerts on tourism practice and tourism research.

Setting the stage: from ‘moments’ to ‘crises’ then ‘disruptions’

The development of qualitative research in tourism studies in particular, and in the wider social sciences in general, is interpreted as a series of ‘moments’ or periods proposed over the last 25 years (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018). Each ‘moment’ is characterised by guiding ontological, epistemological and methodological beliefs and assumptions; from the early traditional positivist approach through the rupture in thinking of the third moment and its crisis of representation, to the postmodern methodologically contested and blurred present seven, eight, nine, ten moments of hybridity, transdisciplinary and criticality (Wilson et al., 2020).

The first three moments identified by Denzin and Lincoln (2018) are largely informed by post/positivist ways of constructing knowledge that centres scientific rationality, objectivity, validity, replicability, and generalisability despite the emergence of the new representational approaches. In the third moment researchers become aware of their embodied, emotional and affective presences within the process of enquiry (Knudsen & Stage, Citation2015), and of the politicised nature of knowledge production. Critical examinations of gender, race, ethnicity and the ‘Other’ become more commonplace bringing questions of ontology and epistemology to the fore. This ‘crisis of representation’ disputes past traditions as it challenges established positivist scientific traditions (Crang, Citation2003; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018)

It is not until the fourth and following moments of the so called ‘crisis of representation’ when new approaches emerge guided by constructivist, feminist, ethic, Marxist, queer, and cultural studies paradigms (Wilson & Hollinshead, Citation2015). The following fifth to ten moments are characterised by paradigmatic proliferation and resistances with managerialism and neoliberal academic environment. While these periods are characterised by different paradigms and methodological practices such as postmodernism, post-experimentalism there is a common focus on participatory, activist-oriented, and grounded on local realities inquiry (Dwyer & Davies, Citation2010; Wilson et al., 2020).

Mapped onto these moments and crises, it is clear that tourism qualitative research has moved towards more reflexive inquiry that adopts positionality and first-person perspectives. Tourism studies have fleshed out its own ‘crisis of representation’ in the works of the critical turn in tourism studies (Mair, Citation2018) whereby researchers tackled issues such as: gender and feminism (Aitchison, 2005), post and trans disciplinarity (Hollinshead, Citation2016), justice, responsibility and tourism (Burrai et al., Citation2019; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2008), emotions, feelings and affects (Buda, Citation2015; Tucker & Shelton, Citation2018), and ecofeminism (Swain & Swain, Citation2004).

Progress achieved in embracing the crisis of representation is encouraging, majority of tourism scholarship, however, remains driven by positivism, postpositivism and neopositivism (Wilson et al, 2020). Innovative qualitative research that is committed to understanding ‘processes and things in flux, in complex relations and activity’ (Dowling et al., Citation2018, p. 779), non-representational thinking (Edensor, Citation2007), and methodology that is multi-sensory (Jensen et al., Citation2015; Ogle, Citation2018) has received only limited attention.

Qualitative inquiry in tourism is still primarily concerned with third moment thinking and ‘tourism scholars seem anchored to traditional (post)positivist stances’ (Wilson et al., 2020, p. 11). This is reflected in the strict, traditional paper structures, linear and neat research design and processes, while text production and communication remain elusive. Hence, interviews, observations (Veal, Citation2017) and lived experiences (Jennings, Citation2010), remain mainstream ways of information gathering, while alternative and innovative approaches remain marginalised.

Embracing non-traditional, and even disruptive ways of knowing and doing, as well as exploring and encouraging alternative ways of understanding tourism, will expand knowledges of social practises that that may otherwise remain obscured or glossed over (Lincoln, Citation2010). Post/positivist approaches retain, no doubt, an important place in tourism research, however, an overreliance on ‘scientised’ and established ways of doing research has led to the production of knowledge that is partial and limited (Lather & St. Pierre, 2013; Phillimore & Goodson, Citation2004). Qualitative tourism researchers will require finding and embracing innovative forms of collecting, analysing, writing, and disseminating qualitative insights through a variety of textual, visual, haptic, and even playful methods (Rakić & Chambers, Citation2010). We will be required to move freely between disciplinary boundaries and assumptive frameworks of ‘ethnicities, genres, and long-time inheritances of being and becoming’ (Wilson & Hollinshead, Citation2015, p. 34), as well as to grapple with the challenges of human versus more-than-human praxis (Dowling et al., Citation2017).

Diversifying our qualitative pursuits will require imaginative novel ways to ‘gain access to subject independent realities’ to understand them as they are ‘differently encountered, socially/institutionally’ (Wilson & Hollinshead, Citation2015, p. 32). Innovative and disruptive qualitative enquiries in tourism studies will need to imagine the role of the researcher and our relationships with research participants beyond the ‘top-down lead of expert knowledge’ (Wilson & Hollinshead, Citation2015, p. 32) towards a more collaborative, dialogic, and community-oriented forms of knowing and doing. We will need to embrace researchers as subjects, and our reflexive awareness explored at more critical and in-depth levels.

More imaginative ways of writing and disseminating qualitative work are needed to provide suitable and creative outlets to match the non-traditional methods and to ‘push further into the felt, touched and embodied constitution of knowledge’ (Crang, Citation2003, p.501). Finally, innovative qualitative enquiries in tourism will need to embrace the vast methodological possibilities that virtual, online environments present for research, and which so far have been approached from quantitative perspectives (Tavakoli & Wijesinghe, Citation2019).

Moving beyond ‘moments’ and ‘crises’ in qualitative tourism studies towards disruption and creation of new ways of doing tourism research, is what we advocate in this Special Issue. The papers in this Special Issue showcase the progress that is being made within qualitative tourism enquiry and demonstrate the creative and disruptive work of innovative tourism scholars.

Dis-rupting methodologies

Disrupting settler colonial attitudes in Canada so deeply welded to tourism narrative, and ideologies is what Bryan Grimwood and Corey Johnson – ‘two white, male Settlers socialized in Western academic discourse’ – set out in their paper Collective memory work (CMW) as an unsettling methodology in tourism. Through CMW, memory narratives are generated that allow researchers to unsettle the entrenched workings of colonialism.

Settler colonial and indigenous Canadian settings are also discussed by Roslyn Kerr and Emma Stewart in ‘Motherhood capital’ in tourism fieldwork: experiences from Arctic Canada. Motherhood capital refers to the presence of Emma’s infant baby during fieldwork which helped rather than hindered her acceptance into Inuit communities. Motherhood capital facilitated Emma’s privileged access to Inuit communities and helped transform her perceived status from an outside researcher to an equal-status mother. Drawing on journaling methodology, the authors analyse ‘motherhood capital’ as a disrupter of power dynamics between the researcher ‘other’ and local indigenous communities.

Disruptions are framed as de-colonisations of tourism studies by Leszek Butowski, Jacek Kaczmarek, Joanna Kowalczyk-Anioł and Ewa Szafrańska in their paper Social constructionism as a tool to maintain an advantage in tourism research. Disrupting the ‘dominant white western traditions’ ought to be enacted at several levels from geo-linguistics to economic, political, cultural, and socio-historic. These authors critique social constructivism as not helping to disrupt ‘western’ neoliberal ideologies and political rationality from which tourism knowledge stems.

Disrupting power and politics in large-scale activist mobilities in England is at the heart of Ian Lamond’s discussion of Disruptive and Adaptive Methods in Activist Tourism Studies: Socio-Spatial Imaginaries of Dissent. Disruptive and adaptive methods such as: ‘the Kino-Cine bomber: disrupting urban space’, ‘augmented cinema: disruptive film screenings’, ‘film making workshop: disruptive pedagogy’, and ‘critical conversations: disrupting the focus group’ represent four non-linear ways through which material is collected and interpreted in the field.

Disruptive methodological spaces for tourism phenomena can also framed as re-centering the subject of the study, argue Minii Haanpää, Tarja Salmela, José-Carlos García-Rosell and Mikko Äijälä in The disruptive ‘other’? Exploring human-animal relations in tourism through videography. Non-human participants and their roles in research settings (i.e. dog sledding which is the most popular tourism activity in Lapland) present us with creative disruptions that emerge from a videography research focused on human–animal relations. The politicised and power-related nature of tourism research offers possibilities to disrupt tourism, in spite of the non-human subjects of the study, as authors have to make choices about the sort of images included in the video which will have an impact on tourism stakeholders. Natural or eco-tourism destinations become a ‘more-than-human’ phenomenon, argues Abhik Chakraborty. Creative disruptions could be achieved by moving the focus of qualitative tourism research from being too anthropocentric to a more encompassing dimension which puts multifaceted aspects of non-human life at the centre of tourism enquiry.

To disrupt the role of researchers when gathering material is to embed ourselves into the online world, maintain Heather Jeffrey, Hamna Ashraf and Cody Morris Paris in Hanging out on Snapchat: disrupting passive covert netnography in tourism research. Digital spaces and online platforms can be used to disrupt the way tourism researchers interact with project participants. While disruptions are possible using online tools such as Snapchat, employing social-media applications presents ethical challenges and makes overt passive netnography a real trick.

Re/creating methodologies

Playing with creative tools as a way of re-creating tourism methodologies represents an aspect our Special Issue authors have explored from different angles. There is increased interest in serious play and gaming techniques as alternative, fairer and more participative methods to gather information in tourism research. Yana Wengel, Alison McIntosh and Cheryl Cockburn-Wootten offer A critical consideration of LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® methodology for tourism studies and advocate for participant driven co-production of knowledges via playful Lego bricks. Participants’ meanings of complex and often sensitive realities are unpacked in a creative and inclusive way through a gamification approach which dismantles more traditional approaches to gathering fieldwork material.

Similarly, Lidija Lalicic and Jessika Weber-Sabil propose tourism researchers engage with experiential and behavioural qualities of game play in Stakeholder engagement in sustainable tourism planning through serious gaming. To disrupt and then re-create novel ways to gather, generate and produce material co-created amongst stakeholders, the authors advocate we play ‘serious gaming’. This will enable tourism researchers to develop in-depth understanding about the complex and strategic tourism destination planning processes by challenging belief systems held by individual stakeholders.

In-depth tourism knowledges generated by creative, co-participative and reflexive methods are crucial to moving the boundaries of tourism scholarship. Émilie Crossley interjects the concept of Deep reflexivity in tourism research to allow for fieldwork information, that might be otherwise considered private or embarrassing, to be explored in-depth so as to understand different subjectivities we inhabit while doing research. Memories, dreams, associations, feelings, emotions and fantasies we experience while doing fieldwork, especially in volunteer tourism in Kenya as is Émilie’s case, need to be allowed to come to the surface of our consciousness to process and share in our methodological reflections.

Deep reflexivity is contextualised as non-linear, unpredictable and messy by Jelena Farkic in Challenges in Outdoor Tourism Explorations: An Embodied Approach. Jelena’s reflexivity enables her to explore the nuances and complexities of outdoor research as deeply entangled between her tourism researcher and tourist subjectivities. Thus, messy emotions and unruly sensualities of being an outdoor tourist and a tourism researcher in the same time-space interlink, influencing the way research material is gathered.

Personal reflections and fieldnotes bring to surface risky challenges of accessing chaotic communities in Rio de Janeiro when trying to make sense of how favelas respond to economic, socio-cultural impacts of mega tourism events. Nicola Cade, Sally Everett, and Michael Duignan move back and forth between first person and third person narrative in their discussion of Leveraging digital and physical spaces to ‘de-risk’ and access Rio's favela communities. ‘Digi-cal’ – a digital/physical nexus – is the novel, creative, practice-based model they propose whereby social messaging platforms such as Whatsapp can be favourably used to access high-risk communities whereby deprivation and criminality characterises everyday living. In the same vein, the same Michael Duignan now together with David McGillivray make a case for Walking methodologies, digital platforms and the interrogation of Olympic spaces: the ‘#RioZones-Approach’. Bringing together the physicality of walking planned routes to gather observations, audio and video material, with digitally-enabled primary data collection methods, such as vlogging and blogging, these authors maintain they still hold on to their post-positivist epistemological positions.

Disrupting remnant post-positivist stances, Richard Keith Wright interjects creative non-fiction and ethnodrama in his paper ‘Que será, será!’: creative analytical practice within the critical sports event tourism discourse. Creative non-fiction showcases the potential of creative analytical practice to unravel the narratives of industry experts. Ethnodrama is a creative way to provide insights into the attitudes and intentions of those responsible for delivering international sports events in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Creativity is understood as new ways of bridging the gap between research and practice collaborations by Nancy Duxbury, Fiona Eva Bakas and Cláudia Pato de Carvalho in the paper Why is research-practice collaboration so challenging to achieve? A creative tourism experiment. The challenges achieving robust multilevel collaborations between tourism academics and practitioners have been long discussed. From a methodological perspective, these authors offer tangible propositions to re-position research-practice exchange by developing dedicated spaces for ongoing knowledge exchange, maximisation of face-to-face encounters between researchers and practitioners, and, enabling practitioners to become co-researchers at different stages of the research-design process. Connecting with practitioners via informal, unstructured online interviews is, also, at the heart of Lucia Tomassini, Xavier Font and Rhodri Thomas’ account of The case for linguistic narrative analysis, illustrated studying small firms in tourism.

Au revoir! in lieu of conclusions

Disruption and creativity are the two ideas around which we wanted to challenge and begin dismantling white, ‘western’, neoliberal hegemonic social narratives and ideologies in qualitative tourism methodologies. In tourism studies in general, and tourism geography in particular, the last decade has witnessed an emphasis on qualitative methodological research, both in terms of the topics addressed and the types of methodological tools. In many ways, this legitimisation of qualitative work mirrors developments in other areas such as human geography (Crang, Citation2003; Davies & Dwyer, Citation2007), sociology and anthropology (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018). Such explorations contribute critical understandings of the responsibility of tourism research to be disruptive first before it can engender progress and transformation within and outside of our field.

It is clear that in order to progress and diversify tourism qualitative enquiry we need to create spaces where diverse voices, practices and experiences can be heard. The world, and us as researchers, face unique challenges such as the global Covid-19 pandemic with its need for physical distancing that renders a lot of our traditional methods unhelpful and even risky. Societies are reckoning with their/our colonial pasts, and confronting racism. Thus, decolonising the ways we produce knowledge is no longer optional. Examining and adopting creative, innovative and disruptive methodologies will help us face those challenges.

While progress is being made in crossing ontological, epistemological and methodological boundaries, diverse and imaginative presentation formats to communicate our research, our science is still far behind. Instead of proposing future research avenues, we want to bid you ‘au revoir’ or ‘until we meet again’ and leave you with the message below ().

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Milka Ivanova

Dr. Milka Ivanova’s research revolves around the ways ‘non-dominant’ narratives are re/created or ignored through tourism in the cases of diasporas and communist heritage, with a focus on the representation of Bulgaria in and through tourism, and the dynamics of traditionality vis-a-vis transitionality. She is a passionate proponent of qualitative approaches to knowing the world that look to critique and disrupt existing models of power. She publishes in Routledge Handbook of Cultural Tourism, Tourism Culture & Communication; Sustainability of Tourism: Cultural and Environmental Perspectives.

Dorina-Maria Buda

Professor Dorina-Maria Buda conducts interdisciplinary research with a particular focus on the interconnections between tourist spaces, people and emotions in times and places of socio-political conflict. Dorina conducts ethnographic work in such places of on-going conflicts and turmoil like Jordan, Israel and Palestine. She is the author of Affective Tourism: Dark Routes in Conflict. In her work, Dorina offers a new way of theorising tourism encounters bringing together, critically examining and expanding three areas of scholarship: dark tourism, emotional and affective geographies, and psychoanalytic geographies.

Elisa Burrai

Dr. Elisa Burrai’s research develops through the use of ethnographic, critical and qualitative methodological approaches to explore the nexus between power and research methodologies, researcher’s reflexivity and positionality. Her focus is on residents’ perceptions of volunteer tourism impacts such as in Cusco, Peru, amongst others. In her work published in Tourism Geographies; International Journal of Tourism Research; Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, and so on, Elisa offers thought-provoking critiques of concepts such as volunteer tourism and responsible tourism.

References

- Aitchison, C. C. (2005). Feminist and gender perspectives in tourism studies: The social-cultural nexus of critical and cultural theories. Tourist Studies, 5(3), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797605070330

- Ateljevic, I., Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (Eds.). (2013). The critical turn in tourism studies: Creating an academy of hope (Vol. 22). Routledge.

- Ateljevic, I., Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (Eds.). (2007). The critical turn in tourism studies. Routledge.

- Buda, D. M. (2015). Affective tourism: Dark routes in conflict. Routledge.

- Burrai, E., Buda, D. M., & Stanford, D. (2019). Rethinking the ideology of responsible tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 992–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1578365

- Crang, M. (2003). Qualitative methods: touchy, feely, look-see?. Progress in Human Geography, 27(4), 494–504. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132503ph445pr

- Davies, G., & Dwyer, C. (2007). Qualitative methods: are you enchanted or are you alienated?. Progress in Human Geography, 31(2), 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507076417

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2018). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage.

- Dowling, R., Lloyd, K., & Suchet-Pearson, S. (2017). Qualitative methods II: ‘More-than-human’ methodologies and/in praxis. Progress in Human Geography, 41(6), 823–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516664439

- Dowling, R., Lloyd, K., & Suchet-Pearson, S. (2018). Qualitative methods III: Experimenting, picturing, sensing. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517730941

- Dwyer, C., & Davies, G. (2010). Qualitative methods III: Animating archives, artful interventions and online environments. Progress in Human Geography, 34(1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508105005

- Edensor, T. (2007). Mundane mobilities, performances and spaces of tourism. Social & Cultural Geography, 8(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360701360089

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2008). Justice tourism and alternative globalisation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(3), 345–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802154132

- Hollinshead, K. (2016). Postdisciplinarity and the rise of intellectual openness: The necessity for. Tourism Analysis, 21(4), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354216X14600320851613

- Jennings, G. (2010). Tourism research. (2nd ed). John Wiley and sons Australia, Ltd.

- Jensen, M. T., Scarles, C., & Cohen, S. A. (2015). A multisensory phenomenology of interrail mobilities. Annals of Tourism Research, 53, 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.04.002

- Knudsen, B. T., & Stage, C. (2015). Introduction: Affective methodologies. In B. T. Knudsen & C. Stage (Eds.), Affective methodologies (pp. 1–22). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lather, P., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2013). Post-qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 629–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788752

- Lincoln, Y. S. (2010). “What a long, strange trip it’s been…”: Twenty-five years of qualitative and new paradigm research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800409349754

- Mair, H. (2018). Critical inquiry in tourism and hospitality research. In R. Nunkoo (Ed.), Handbook of research methods for tourism and hospitality management. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Nunkoo, R., Thelwall, M., Ladsawut, J., & Goolaup, S. (2020). Three decades of tourism scholarship: Gender, collaboration and research methods. Tourism Management, 78, 104056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104056

- Ogle, A. (2018). Sensual Quasi-Q-Sort (SQQS): enriching qualitative hospitality and tourism research via the human senses. In R. Nunkoo (Ed.), Handbook of research methods for tourism and hospitality management. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Phillimore, J., & Goodson, L. (2004). Progress in qualitative research in tourism: Epistemology, ontology and methodology. In Qualitative research in tourism (pp. 21–23). Routledge.

- Rakić, T., & Chambers, D. (2010). Innovative techniques in tourism research: An exploration of visual methods and academic filmmaking. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(4), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.761

- Swain, M. B., & Swain, M. T. B. (2004). An ecofeminist approach to ecotourism development. Tourism Recreation Research, 29(3), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2004.11081451

- Tavakoli, R., & Wijesinghe, S. N. (2019). The evolution of the web and netnography in tourism: A systematic review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.008

- Tucker, H., & Shelton, E. J. (2018). Tourism, mood and affect: Narratives of loss and hope. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.03.001

- Veal, A. J. (2017). Research methods for leisure and tourism. Pearson UK.

- Wilson, E., & Hollinshead, K. (2015). Qualitative tourism research: Opportunities in the emergent soft sciences. Annals of Tourism Research, 54, 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.06.001

- Wilson, E., Mura, P., Sharif, S. P., & Wijesinghe, S. N. (2020). Beyond the third moment? Mapping the state of qualitative tourism research. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(7), 795–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1568971