Abstract

The concept of ‘overtourism’ has boomed in the past five years as the latest term to refer to anti-tourist sentiment in tourist hotspots. News media’s widespread use of the term suffers from conceptual slippage and a tendency to incite moral panic. However, a deeper theorization of overtourism as embodied, place-based social conflicts shows that this phenomenon is not about absolute visitor numbers or particular tourist activities, but rather about the connection between place, class and the political economy of tourism. Drawing on Urban Political Ecology and qualitative case-studies of freedom camping in two urban areas of Aotearoa New Zealand, we examine how social conflicts between tourists and hosts erupted in poorer urban areas as NIMBYism in privileged areas with greater access to state resources pushed freedom campers out. Both hosts and tourists are agentic in these encounters. Locals frustrated with tourist behaviour they deem visually invasive and physically polluting ‘police’ freedom campers, ranging from facilitating formal police action and governance regulation to vigilante behaviour. Freedom campers subvert these acts of policing, often through the very rules and technologies that are in place to regulate and monitor them. At the heart of these issues is a problem of neoliberal governance which stresses tourism’s ‘economic benefit’ to the regions, while placing responsibility for managing tourist/host relations on local territories.

1. Introduction

The term ‘overtourism’ has been in use only a few years, but a range of definitions have emerged, from a focus on overshooting carrying capacity, to destruction of ecologies, and unsustainable impacts on sociocultural environments (Ojeda and Kieffer Citation2020). This work builds on a longer scholarly concern with tourism’s impacts on local communities and ecologies (Hannam, Citation2002; Urry, Citation1990). Recent literature notes that the term overtourism suffers from conceptual slippage, and proposes a focus on social conflict as ‘the most characteristic constituent and manifestation of overtourism’ (Zmyślony et al., Citation2020, p.1). This focus aligns with the United Nations World Tourism Organisation’s definition of overtourism as being ‘the impact of tourism on a destination, or parts thereof, that excessively influences perceived quality of life of citizens and/or quality of visitors’ experiences in a negative way’ (UNWTO, 2018, p. 6). This focus on feelings or perceptions (rather than, for example, ecological carrying capacity) brings our conceptual attention to the potentially conflictual relationships between hosts and tourists, who, as Harold Goodwin argues, ‘often experience the deterioration concurrently and rebel against it’ (Goodwin 2019, 2).

International news media’s use of the term overtourism tends to incite moral panic over city- or country-wide tourist numbers. However, a deeper theorization of overtourism as embodied, place-based social conflicts shows that this phenomenon is not about absolute visitor numbers or particular tourist activities, but rather about the connection between place, class and the political economy of tourism. In this article, we seek to deepen theorisation of overtourism as a place-based social conflict by bringing an ‘embodied’ Urban Political Ecology (UPE) (Doshi, Citation2017) perspective to the contestation over public space, the concrete ways in which overtourism manifests as embodied conflictual encounters between locals and tourists, and how hosts and tourists ‘rebel against’ the perceived deterioration of their quality of life. We focus on the phenomenon of ‘freedom camping’—a form of tourism entailing overnight stays in public spaces rather than formal campgrounds—that has a long history in New Zealand and is cherished by many New Zealanders. Freedom camping has grown rapidly amongst domestic and international tourists in the past ten years. Within New Zealand’s decentralised approach to tourist management, freedom camping has enabled positive tourist/host encounters in some places, while erupting into social conflicts in others. We argue that it is not the presence of tourists per se that creates contention and conflict but the perception by locals that tourists are violating normative social boundaries over what is considered appropriate use of public space. Locals ‘rebel against’ these perceived violations by seeking to informally police tourists’ presence and behaviour, while some tourists also rebel against the deterioration in their tourist experiences by attempting to undermine state and local communities’ efforts to police and regulate them and thereby seek an elusive ‘freedom’ in their freedom camping experience. In privileged areas with greater access to state authorities and tourist infrastructure, tourist impacts are either absorbed, or pushed onto poorer areas where social conflict can emerge.

Our UPE approach asserts that overtourism—as an embodied, place-based social conflict arising from perceived negative impacts of tourism on quality of life of hosts and quality of visitor experience—must be understood within the broader sociopolitical context that shapes hosts’ and visitors’ expectations. Tourism is prioritized by national governments as a major driver of GDP in post-industrial economies (Airey, Citation2015), and is one of New Zealand’s biggest industries (Mackenzie, Citation2017; Stats, Citation2023). Camping tourism in both commercial campgrounds (private and publicly owned) and ‘freedom camping’ in areas outside authorised campgrounds has long been a popular option for both New Zealanders and international tourists, but successive waves of regulations have limited freedom camping (Nava et al., Citation2022). In 2011, the New Zealand Government institutionalised freedom camping through the Freedom Camping Act (FCA) as a way of managing the unique challenge of an expected influx of tourists for the Rugby World Cup (FCA, Citation2011). The Act was passed quickly before the Rugby World Cup with no national-level debate about its possible consequences. The FCA allows people to camp (other than at a registered campground) using a tent or motor vehicle, anywhere within 200 m of a road or coastline (Section 5). The Act puts the onus on territorial authorities (city/district councils) to manage freedom camping through local bylaws and policing. What this has meant in practice, as our study bears out, is that while the FCA is at first glance a ‘permissive’ law that prevents blanket bans on camping within districts and cities, in actuality, local councils have used the FCA to restrict areas and types of freedom camping (Nava et al. Citation2022).

Freedom camping can benefit local areas as campers tend to stay longer and travel to more places (MBIE, Citation2018). It is estimated that the number of international visitors practising freedom camping rose from 10,000 to 123,000, in just one decade (2008–2018) (MBIE, Citation2018), and motorhome rental companies supply more than 60,000 hires to national (about 16%) and international (84%) tourists (Coker 2012). However, many councils have had difficulty managing the volume of freedom camping and its social and environmental impacts. In response to local tensions, the central government has initiated tools to regulate and monitor freedom camping, including a camping app and vehicle self-containment regulation. We show the limits of these tools as campers ‘rebel against’ the intentions of these tools to regulate their mobility and activities and instead deploy them to re-assert their ‘free’ camping experience.

We begin by situating the study within an embodied UPE framework and two connected discussions: freedom camping encounters; and the informal policing of tourists in public space. Following our methodology, we analyse our two case-study sites, illuminating the ways in which overtourism manifests as social conflict, and how hosts and tourists rebel against their perceived deterioration of quality of life/visitor experience in differing ways. Finally, theoretical insights into the heterogenous nature of overtourism encounters are advanced.

2. Literature review

2.1. Understanding overtourism as conflicts over public space

Urban Political ecology (UPE) has emerged as a framework for analysing the production of and contestation over public space, uneven urban development and its unequal socioecological relations (Smith, 2008). UPE disentangles ‘the interconnected economic, political, social and ecological processes that shape urban landscapes’ (Cook and Swyngedouw, Citation2012, p. 1960), showing how the production of public space takes place against the backdrop of economic liberalisation and a comprehensive market logic. UPE analyses focusing on tourism are scarce but growing (Douglas, Citation2014) and reveal how economic interests within neoliberal frameworks have reappropriated the social and environmental needs of local communities as extractive tourism markets grow, transforming public places from sites with sociohistorical meaning for indigenous and local peoples to spaces of leisure for those who can afford it (Douglas, Citation2014). Recent UPE scholarship also calls for going ‘beyond the city’ in our analyses, to understand how urban and rural (and sub-urban, ex-urban, peri-urban) spaces interact and shape each other (McKinnon et al., Citation2019; Tzaninis et al., Citation2021).

UPE scholarship connects with geography scholarship on the material and social production of public space (Lofland, Citation1989). Croll (Citation1999) chronicles how public spaces are vital to the civility of urban life: if public spaces are ordered, welcoming and peaceful, this is a sign of the urbanity of its citizens; if they are dirty or violent, the idea of civilisation itself is called into question. We can thus read outrage over practices such as public toileting (Barcan, Citation2005), sexual activity or nudity (Sanders et al., Citation2010) or tent camping and clothes washing in city parks (Winslow, 2017) as threatening the civility of the city itself. As stated by Mitchell (Citation2003 p. 13), ‘public space engenders fears, fears that derive from the sense of public space being uncontrolled space, as a space in which civilisation is exceptionally fragile’. The fear of public spaces succumbing to transgressive others and activities perceived as inappropriate and uncivilised has invoked increased policing of public spaces ‘to assure… [they] remain ‘public’ rather than hijacked by undesirable users’ (p. 2). This policing, both private and by state agencies, serves to maintain the quality of urbanity and the security of ‘housed residents and visitors’ (p. 4). UPE scholars also connect tensions over access to public space with capitalist enclosures of the public. Contemporary concern with public behaviour in tourist hotspots, for example, is connected with dictates of economic and urban restructuring, and diminishing resources to maintain public spaces and low-cost campgrounds (Collins & Kearns, Citation2010).

Following Doshi’s (Citation2017) call for a more rigorous treatment of the body as a material and political site within UPE, we ground our analysis in the ways the body is mobilised in host/tourist conflict over public space. Relational understandings of the production of public space connect socio-natures of consumption, waste and resource distribution with the intimate embodiments of these flows among differently situated groups (Doshi Citation2017). This brings our attention to the ways particular bodies are included/excluded in the constitution of the public. Appadurai’s (2001) ‘politics of shit’, for example, reveals the contours of who and what kinds of behaviour is acceptable, when some people, due to their social locations (gender, class, propertylessness etc), cannot be distanced from the stigma of waste. As Doshi (Citation2017) asserts: If ‘political ecologies are something that people do, then attention to bodily practices in urban public spaces links affect, bodies and waste’ and mediates conflicts over access to resources. Thus our analysis of freedom camping employs an embodied UPE perspective to connect the micropolitics of social conflicts between tourist/host over embodied behaviours in public space with the broader politics of state authority and neoliberal tourism policies.

2.2. Regulating ‘freedom’ in New Zealand freedom camping

Camping tourism is a key site for understanding tourist encounters, yet, has been under-researched (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2020), and much of the tourism scholarship that does examine camping tends to focus on campgrounds rather than camping in public spaces (Brooker and Joppe, Citation2014). The use of public space is the source of much contestation surrounding freedom camping. In New Zealand, freedom camping has raised concerns throughout history, and has been addressed through camping bans on specific spaces, dating back to fines for camping on native land in the 1840s (Jimenez, 2020; Nava et al., Citation2022). In early colonial New Zealand, these bans focused on reducing conflict between colonists and Māori, reducing vagrancy in the growing cities, and removing shepherds and their flocks of sheep from public and private land, while the focus shifted to regulating holiday campers from the late 1800s (Jimenez, 2020). Commercial holiday campgrounds proliferated from the 1930s, but freedom camping has remained popular with New Zealanders and international tourists.

A paradox of freedom camping is that whilst often motivated by a desire to independently explore ‘natural’ landscapes (Graefe & Dawson, Citation2013), it is not necessarily a wilderness activity, as it frequently takes place within (and on the peripheries of) cities and towns, which campers value for their proximity to culture, air travel and tourist activities (Keenan, Citation2012; LGNZ, Citation2018). Many freedom campers seek to ‘experience the freedoms of non-regulated, non-commercial accommodation’ (Caldicott et al., Citation2014, p. 431 l; Collins & Kearns, Citation2010), which locals can perceive as simply avoiding payment or capitalizing on ratepayer-funded local services and the use of public land (Kearns et al., Citation2017). In New Zealand, the FCA allows freedom campers to stay in areas such as parking lots and public picnic areas and when the activity occurs in proximity to settled areas, it is visible—and sometimes audible and pungent—to local residents, who can perceive it as a threat to normative understandings of public space. Freedom camping is not just an international tourist activity and has become more widespread amongst New Zealander’s due to the sell-off of commercial coastal campgrounds (Kearns et al., Citation2017). However, freedom camping by New Zealanders is less contested, especially in in local media attention that largely focuses on international tourists (a tendency to xenophobia that we explore below).

Regulation of tourist activity in public space takes place through the legal manoeuvres of central and local governments enacting bylaws, zones and licences, and surveillance by police and authorities (Collins et al. Citation2017). In New Zealand, devolution of responsibility to regulate freedom camping to local government has resulted in different by-laws governing where freedom camping can occur and the length of stay allowed. In addition, central government initiative two innovative mechanisms to formally regulate freedom camping. First, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) purchased the privately-developed Campermate app, which captures real time data of freedom campers’ locations. When freedom camping sites reach capacity, campers receive pricing deals for campgrounds, and information on campsites, dump stations and attractions (Campermate, Citation2019). Second, a self-containment standard for campervans (NZS 5465:2001; Standards Association of New Zealand, Citation1990) was introduced as an official regulatory standard. A vehicle that meets the self-containment standard is affixed with a blue sticker, and can camp in a greater variety of locations than vehicles dependent upon public sanitation infrastructure. There should be, in principle, no open defecation by freedom campers with vehicles displaying a blue sticker. However, the self-containment standard is poorly managed and there is currently no central body responsible for its oversight. Thus, some freedom campers are compelled to defecate in public, usually for the dual reason that their vehicle is not adequately self-contained, and public sanitation facilities are not accessible. As we discuss below, both the Campermate app and the self-containment standard have been used by some freedom campers to subvert formal regulation of their activities and informal policing by locals.

Beyond the formal state regulation of public space, local people also engage in informal modes of surveillance and policing tourists. This aspect of host behaviour is under-researched in tourism literature, which has tended to see ‘hosts’ as a somewhat passive group, even if dissatisfied with tourism’s effects (Krippendorf, Citation1999; Ojeda and Kieffer Citation2020). Recent scholarship on surveillance and policing adopts a Foucault (Citation1982) understanding that power is always relational, emergent, and enacted through the dispersed practices and relationships between state and other actors (Ekers & Loftus, Citation2008; Cornea et al. Citation2017), including individuals who seek to ‘police’ violations of law, societal norms and behaviours (Cook & Whowell, Citation2011). In New Zealand, Collins et al. (Citation2017) describe how freedom camping sites have become contested spaces that local authorities and police seek to regulate. Here, we focus not on formal regulation but on the informal policing of freedom campers, which frequently accompanies formal regulation, and can act to both reinforce formal regulation, and to subvert it. Practices of informal policing include verbal abuse, physical altercations, alerting authorities to overcrowding, posting photographs on social media, and even physically barricading a site (Comer, Citation2019).

Formal and informal policing co-constitute public space through attempts to make transgressive bodies and behaviours variously visible and invisible. These strategies of control create a ‘moral topography’, where certain bodies are constructed as ‘dirty’ and ‘backward’ (Swanson, Citation2007) and need to be banished or hidden, or sometimes revealed through public punishment (Cook & Whowell, Citation2011). UPE literature reminds us that when campers appropriate public spaces such as beach fronts and parking lots, it is not merely their presence in public space that locals complain about and seek to control, but the visibility of their everyday behaviours: cooking, brushing teeth, hanging washing, eating, sleeping, and most problematically toileting (Collins et al. Citation2017; Rantala and Varley Citation2019). These activities meet resistance because they violate locals’ understanding of what is considered appropriate use of public space. As we discuss below, overtourism thereby manifests as embodied, place-based social conflict where hosts engage in informal policing in differing ways depending on their social power and access to authority, and tourists also engage in acts of rebellion through subverting attempts to police their behaviour.

3. Context and methodology

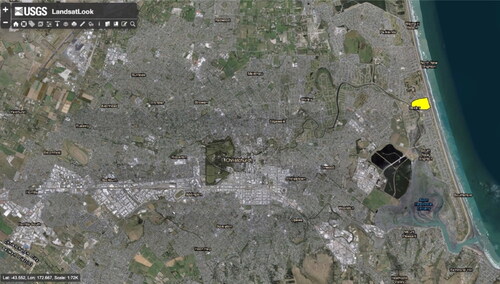

We adopted a multi case-study approach covering two sites in Aotearoa New Zealand: New Brighton and Akaroa. Both sites are located in the Christchurch District and were selected due to their popularity, diverse regional and local characteristics, and their different formal governance and management responses to freedom camping. New Brighton is located in the city of Christchurch, a major tourism hub with population around 400,000 (CCC, Citation2019). The Christchurch City Council (CCC) also governs the remote Banks Peninsula area, where the popular tourist destination of Akaroa is located. While New Brighton is a low-socioeconomic suburb in a sustained period of economic decline (Morgan, Citation2002), Akaroa is a small, affluent town. Christchurch does not have any formal freedom camping infrastructure and initially allowed a period of liberal freedom camping in its municipal picnic areas and carparks (Billante, Citation2010; CCC, Citation2019). However, sites quickly became overcrowded as large numbers of foreign freedom campers gravitated to the city for proximity to amenities and cultural activities (LGNZ, Citation2018). In 2015, after a chaotic period of freedom camping, the CCC responded to community pressure by banning non-self-contained freedom camping and severely limiting self-contained camping (CCC, Citation2015).

In each location we used a multi-method qualitative approach to data collection. Site visits involved observations of freedom camping, facilities, and formal and informal policing regimes. Document analysis of government reports and policies, and online content such as news articles, blogs, and freedom camping apps was also appraised. In addition, twenty-two semi-structured interviews were completed with 33 participants between November-December 2018. Individual interviews were held with local elected representatives (5), campground managers/owners (4), freedom campers (7), Park Ranger (1), Department of Conservation Technical Manager (1), local residents (3) and representative from Business Association (1), New Zealand Police (1), Manager - Tourism Industry Aotearoa (1), CEO—Holiday Parks Association of New Zealand (1), and CEO/Owner—Campermate/Geozone (1). Group interviews were held with representatives from a local government Parks Policy Team (5 participants) and a local government Reserves Office (2 participants), as these groups chose to have multiple attendees in the scheduled interview. Due to the ethnographic nature of site visits some of the interviews with Campground Managers/Owners, freedom campers and local residents involved multiple participants contributing to the interview. As a case-study approach we did not aim for saturation in the interviewing but capturing and understanding the beliefs, opinions and practices of a diverse range of freedom camping stakeholders.

In order to make sense of a diverse data set, we utilised an interpretative approach to thematic data analysis. We sought to identify language patterns, phrases, words, feelings and actions across the range of participants. To do this we developed an analogue coding of the interview, conversation and observation data that were subsequently entered into a coding software. We created a coding memo with scaffolding links to interviewees, literature, the research questions and emergent themes.

Regarding author positionalities, all authors were born and raised in New Zealand (the lead author is from the region where the study was conducted), and have at various times in our lives (starting in the 1970s) engaged in freedom camping with family, friends or individually. Having enjoyed the opportunity to freedom camp in New Zealand we do not think it is inherently bad for the country, the regions, or specific locations. However, given its proliferation in recent years (and pre-Covid and border closures), its negative representation by local and national media reporting, and seeing the diverse viewpoints and often heated disagreements about freedom camping on our local community media sites (i.e. facebook groups), we sought to understand the place-based dynamics of freedom camping.

4. Local reactions to overtourism: informal policing of freedom camping

4.1. New Brighton

Freedom camping in New Brighton grew alongside the area’s protracted recovery from a major earthquake in 2012 (LINZ, Citation2017). Freedom campers, displaced Christchurch citizens, and construction workers employed for the city’s rebuild formed mixed informal settlements of campervans and tents in public areas. Tensions rose as freedom camping expanded, and hundreds of emotive online comments and more than 40 complaints were made to CCC about camper behaviour (Cornish, Citation2019). National media coverage heightened awareness and added to anti-camper sentiment through emotive language. A popular theme in New Brighton media commentary centered on campers’ bodily behaviours and the defiling of public space through noise and polluting smells of defecation, such as one man who said; ‘They are pooing on our beach!’ (Cornish, Citation2019) (, ).

Figure 2. (a) Christchurch city with New Brighton-marked in yellow to the right. Source: USGS LansatLook (2019).

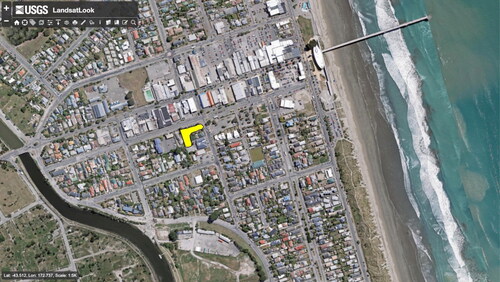

Figure 2. (b) Beresford St freedom camping site (yellow shape, centre left). Source: USGS LansatLook (2019).

Several research participants articulated the inappropriateness and discomforting affect of campers’ activities in public spaces, such as a local government representative:

Well, it’s just not very nice, even things like people hanging their washing out, like making a washing line and stuff. I guess people didn’t think of it as a camping area. It is quite a tension, though isn’t it there because, I think in New Zealand, we did like being able to just drive and stop up. (Local MP)

Issues really are not so much that they park up there, it’s what they leave behind. There’s always a concern about using the sand dunes as toileting facilities, and that’s the principle issue that a lot of people raise.

…a lot of people were camping there with no toilet facilities, no washing facilities. It’s right on the Estuary which we really love… People were just like using it as a toilet. Most of us wouldn’t imagine people doing that.

When freedom camping was banned in several coastal carparks in New Brighton, campers began using a vacant parking lot in Beresford St with no public infrastructure, adjacent to the rundown New Brighton Mall in the middle of dense residential housing. One resident described how the area’s sights, sounds and smells had changed, and it had ‘turned into a party zone’, with campers ‘encroaching’ on local space and turning the area into their ‘own little community’. Campers’ re-appropriation of this public space and its proximity to everyday community life bewildered people. As one participant expressed: ‘we’re not talking about a random campground, we’re talking about a random car park on a street next to residents. What were they [freedom campers] thinking?’. She explained how the lounge room window of a house bordering the carpark was ‘literally….two meters away from these guys squatting down and going to the toilet and hanging their washing up!’ and questioned: ‘Where do they shower? Where do they go to the loo? How do they dispose of their rubbish? Those are very visceral [questions] and the heart of it if you know anything about this community’.

Community representatives discussed how they made complaints to police and council but felt action by officials was unreasonably slow. Locals complained about the lack of police action on social media:

when we rang, the council said they have no regulation about not allowing freedom campers in the car park… Meanwhile we neighbours have to put up with the public rubbish dump, public garden toilets, loud talking in foreign languages, drinking partying and we got abused by French and German citizens… Even with threats like that the police and council say they cannot interfere.

In the Beresford St car park, a number of residents took actions to police campers’ behaviours themselves, including tooting at them, putting up signs, visiting the campers to ask them to be quiet and leave, taking photos of campers defecating and hanging washing and posting them on a community Facebook page. Locals shared ideas for policing campers on the Facebook page, such as ‘a daily check up on each freedom camper to keep tabs on them’ (FB, 27 November 2015), or ‘cameras and lights installed in the carpark’ (FB, 15 Dec 2015). Tensions between the groups rose, and several physical altercations took place (Mitchell, Citation2015). In 2015 a reporter visiting the site was approached by campers and threatened by one with a hunting knife, ‘who took offence to him taking pictures in the public space…and told him he had no right to photograph the campers’ (Meier & Mitchell, Citation2015). The conflicts in New Brighton can clearly be seen as instances of overtourism with locals perceiving their quality of life to be negatively affected by freedom campers. Notably, it was not the presence of the campers alone that led to social conflict, but the sense that the campers were transgressing the expectations of what behaviour is allowable in public space.

Analysing how and where social conflicts manifest highlights issues of class and the exploitation of lower-socioeconomic spaces as sites of tourist accumulation (Krippendorf, Citation1999). Residents felt it was highly unlikely that in a more affluent area of the city, freedom camping would have been allowed to develop as it did in New Brighton. The slow response from the CCC illustrates a tension at the heart of tourism debates for low-income areas. The local Member of Parliament (MP) explained to us that many residents had expressed their unhappiness with the carpark site but she wanted to find a solution that enabled the campers to stay in the area and contribute economically to the depressed suburb. She responded to citizen complaints in her capacity as an elected official but also had to work within the Council’s rules and enforcement strategies. Until the CCC enacted a bylaw in 2015 that excluded most freedom camping from the city (except for fully self-contained vehicles allowed maximum two-night’s stay), her strategy was essentially to move campers on from one carpark to the next or encourage them to move to a paid campsite in the local vicinity.

Freedom campers described to us the treatment they received from locals in some sites: locals banging on vans late at night, or campers being physically and verbally confronted. They also discussed how they sought to keep themselves safe and mitigate legislative and social risk through the use of the Campermate app. Campers scanned comments on the app to avoid sites with hostile locals or overzealous authorities, and to learn about more lenient sites. This practice resulted in campers crowding into convenient sites like Beresford St. A community organizer in New Brighton discussed camper mobility enabled through information sharing on Campermate and the frustrations this presented for local residents and their informal policing efforts:

[It’s like a] snowball effect for places like [Beresford St] where you get two or three to start with and they’re messaging on international camping sites, ‘we’ve found this place, come and join us up for a party’…’ there was no way of us as a community regulating that word being spread [on social media], absolutely no way!’.

4.2. Akaroa

Freedom camping issues in Akaroa are reminiscent of wealthy coastal property owner conflicts with freedom campers in other areas of the country (Collins & Kearns, Citation2010). Akaroa’s residents are divided on the issue of freedom camping. Locals discussed a split in the town, referring to a ‘‘vocal minority’ to characterize one group of residents with an anti-tourist sentiment, while another group was in favour of well-managed tourism. Participants perceived that high-value property owners (including absentee holiday home-owners) and retirees mostly opposed freedom camping in Akaroa, while business owners wanted camping to continue, albeit with better management and infrastructure.

Residents we spoke with explained how Akaroa’s narrow and hilly topography amplify the visibility of freedom camping, and push tourists into the local township. Residents recalled a contentious conflict with freedom campers, which began when residents observed freedom campers washing dishes and clothes in a public water fountain. Media has reported that camping sites out of the township were being used as an ‘open-air toilet’ (Cropp, Citation2018a) and that a septic tank attached to a public toilet had overflowed and leached into the ocean due to overcrowding by freedom campers, allegedly causing an E Coli outbreak (Law, Citation2016). A local resident we spoke with recalled the incident: It was just diabolical! [Freedom campers] were tenting all over the place and it got to the stage where you couldn’t drive up the road, and the local people trying to get to their houses were being abused’.

The Akaroa site also exposed a nationalist and class sentiment in relation to freedom campers. Freedom camping in expensive, self-contained RVs is popular amongst older, affluent New Zealanders—a group known as ‘Grey Nomads’, and Akaroa residents compared this group to campers in run-down, non-self-contained vehicles, whom they saw as the primary offenders to the town’s ‘visual harmony’. One local epitomised these views, noting: ‘it’s not so much the big fully self-contained caravans, it’s the cars, sleeping in cars and opening the boot and throwing all the gear out, you know, just degrading’. She explained how budget, non-compliant campers emptied their non-self-contained vehicles in public view, and used the public water fountain to clean and prepare meals.

The self-containment standard blue stickers on rundown vehicles was perceived by residents as legal lip service and led to community perceptions that many blue stickers were counterfeit. Such perceptions have some validity and it has been reported that penalties for non-compliance and hostility towards freedom campers has provided an impetus for the emergence of a burgeoning market of counterfeit blue self-containment stickers for vehicles that do not meet certification (Martin, Citation2019; McNeilly, Citation2019). The emergence of the counterfeit market in blue stickers is made possible through the poor regulation of the self-containment standard and the lack of public sanitation infrastructure, and like the Campermate app is one way in which some freedom campers attempt to avoid local hostility and formal and informal policing of their activities.

Like New Brighton, Akaroa residents have taken it upon themselves to police what were perceived to be undesirable freedom camper behaviour, and freedom campers they did not believe were genuinely self-contained. Groups of locals have made formal complaints to police and local government, written submissions to the council, and presented their complaints to the Community Board (Cropp, Citation2018b). Unofficial notices are taped on public areas issuing instructions to campers on how to use particular spaces. A water fountain in the centre of town has a typed notice taped to it instructing campers ‘Please Do Not wash dishes, brush your teeth, wash clothes’. Such notices may have limited effect, however; when we visited, a freedom camper was brushing her teeth in the fountain (, ).

Unlike New Brighton, however, the Akaroa police and local government have been responsive to locals’ complaints. For example, over two months during the fieldwork period in 2018, the CCC reportedly issued 62 infringement notices for illegal freedom camping: 49 of them were for offences in Akaroa, and only 13 for the entire Christchurch city area (Cropp, Citation2018b). In response to what one police officer termed ‘constant complaints’ from locals, the Akaroa police installed signs warning that people seen ‘excreting in a public place’ could be arrested, and they encouraged locals to take photos of freedom campers and their vehicles if locals saw a camper defecating in public (Cropp, Citation2018b). Furthermore, the local government in Akaroa has responded to locals’ complaints with town meetings, formal policing, and the Deputy Mayor of Christchurch working closely with Akaroa’s tourism industry (Williscroft, Citation2018). When we interviewed the Deputy Mayor, he was critical of freedom camping in Akaroa, and contrasted it to less picturesque locations—perhaps like New Brighton:

The toileting and the rubbish disposal are an issue, kind of proliferating stuff outside of their van, picnic tables and chairs and drying washing and drying wetsuits and having other gear just strewn around the place. In a way that makes the place look untidy, particularly in a place like Akaroa where people have chosen to live there and chosen to visit there because it’s a very beautiful little town. That kind of visual invasion is more obvious in a place like Akaroa than it would be in somewhere that wasn’t quite so neat and tidy in the beginning.

5. Discussion

This study contributes to tourism literature by bringing an embodied urban political ecology lens to work on overtourism, which grounds discussions of overtourism in the material encounters between locals and tourists, and the dynamics between place, class and the political economy of freedom camping. This study also contributes to literature on everyday acts of policing through analysis of how informal citizen policing intersects with formal policing and governance, how formal and informal policing intersect with place and class, and how attempts to surveil and control people are subverted. Recent literature points to the blurring of boundaries between public sector policing and private sector security, as surveillance technologies (such as smart phones and social media groups) have enabled individuals and groups to police their communities and ‘others’ without the direct input of the police in order to achieve their own forms of policing and justice (Mitchell, Citation2003; Spiller & L’Hoiry, Citation2019). This policing of public spaces is seen to enable safe neighbourhoods and the quality of urban life for housed residents (Mitchell, Citation2003), but Mols and Pridmore (Citation2019) argue that this kind of lateral surveillance can lead to problems, including increased discriminatory practices, normalised suspicion, and vigilantism. We found that differing sentiment and informal policing practices towards freedom campers varied in form and intensity from place to place, depending on class and place politics, and the perceived degree of ‘otherness’ and ‘uncivilised’ behaviours.

In Akaroa, an affluent area catering largely to better-off national and international tourists, our participants frequently commented on the quality of tourist/camper rather than their place of origin. Budget freedom campers (foreign or New Zealand citizens) were seen as culpable for compromising the natural and historical attractiveness of the area and were targeted as disruptive, non-compliant ‘others’, whereas freedom campers with the financial ability to travel in self-contained RVs were regarded as more tolerable visitors for their contribution to the local economy by the middle-class business demographic who rely on tourism revenue (and who likely also travel internationally). In contrast to this class-based dynamic, in Beresford Street carpark, which was largely occupied by budget freedom campers and a transient labour force for the Christchurch rebuild, our participants ‘othered’ campers based on their ‘foreignness’ (perceived to be largely European), and vagary for a fun and free camping experience rather than their socio-economic status symbolised by their camping vehicle. Thus, our study reveals that the ‘moral panic’ and in turn informal policing of tourists is not homogenous and that the forms it takes depends on the socio-economic nature of place, (un)established relationships to the ‘other’, and the character of the tourist: nomadism is acceptable and accepted if it doesn’t challenge the contextual norms and demographics of a locality.

Analysing the heterogeneity of informal policing of tourist behaviour as a class and place-based practice can also be extended to official responses by local government, police and politicians. New Zealand’s government has devolved regulation of campers to local governments, similarly to Australia, where the government devolved regulatory power over campers to local governments without clear national guidelines, leading to a confusing environment for locals, local government agents, and campers (Caldicott et al., Citation2014). Despite freedom camping in New Zealand being governed nationally (by the FCA), and freedom camping in both Akaroa and New Brighton regulated by the CCC, the different political ecologies shaped regulatory and policing response. In New Brighton, freedom campers were banned from camping near the attractive Marine Parade estuary, which pushed campers without adequate self-containment to congregate in streets and parking lots further from the sea. Moving tourists from place to place through local by-laws is a common (and wholly inadequate) regulatory response to overtourism and the lack of infrastructure supplied by local governments. This is reminiscent of geographic literature on NIMBYISM and the siting of ‘environmental bads’ or social ‘undesirables’ in poorer neighbourhoods (Takahashi, Citation1998), and reproduces social exclusion, displacing problems of governance onto conflicts between poorer urban residents and tourists. Freedom camping has not been banned in Beresford Street, despite similar pollution concerns to those at the Marine Parade Estuary, additional complaints related to noise and light pollution, and verbal and physical conflict between locals and campers. Furthermore, political arguments were made to maintain the presence of budget freedom campers for their contribution to the local economy, arguably at the expense of the quality of life for local residents who border popular camping spots in the neighbourhood. In contrast, authorities responded rapidly to citizen complaints in the wealthy area of Akaroa, with police issuing far more infringement notices than in other parts of the region, and local government meeting repeatedly with concerned residents.

Another way to think about these dynamics is through the lens of symbolic, structural, physical and other forms of relational violence that emerge in acts and processes of tourism development (Devine & Ojeda, Citation2017). Dispossession, brought about through capital accumulation, the enclosure of commons, local autonomy and so on, is according to Devine and Ojeda (Citation2017), one expression of tourism’s violence. In our case-studies, we observe various forms of dispossession. Freedom campers occupying desirable public locations are moved on, dispossessing them of freedom of choice in where to stay. The transgressive camper—the one who is not able to travel in a self-contained vehicle—is a major source of tension and conflict between locals and campers. The visibility of defecation and personal hygiene activities that violate socio-moral ideas of public/private boundaries is a key aspect of violence that takes shape in the tourism development of freedom camping. The drive for tourism development and GDP combined with a lack of provision of adequate public sanitation facilities for budget campers can be considered a form of structural violence. Not only does this place campers in vulnerable and precarious situations, subject to hostility and at times verbal or physical violence from local residents, it also operates as symbolic violence for local residents who can feel dispossessed of the quality, availability and control of public spaces.

Finally, a relational understanding of overtourism as social conflict brings our attention to hosts’ and tourists’ agency in tourism encounters. Some freedom campers responded to informal policing of their behaviour by subverting the surveillance and regulation of their mobility through the use of the Campermate app, and the national self-containment standard. Research on managing overtourism looks to digital apps to help manage the problem by redistributing tourism to different areas (Camatti et al., Citation2020). Our study suggests, however, that digital apps are a problematic way of managing camper flows, as they can be used to crowdshare locations in ways that increase camper numbers in contentious locations. We found no evidence of campers using the app to source alternative paid accommodation options. Rather, campers used the app to subvert locals’ informal policing efforts by avoiding sites known for problematic encounters and keep themselves safe, as well as avoiding sites frequently monitored by authorities and thus avoiding costly fines. The attempts to regulate camper vehicles through the ‘blue sticker’ system is also beset with problems: the system is poorly managed and there is little oversight. The emergence of a counterfeit market for blue self-containment stickers is just one way for some freedom campers to subvert formal and informal policing of their private activities in public places, and to deflect potential hostility from local residents.

6. Conclusion

In this article, we have contributed to the emerging literature on overtourism through theorising overtourism from an Urban Political Ecology perspective as embodied social conflict over public space. This analysis reveals that it is not the presence of tourists per se that creates conflict but the perception that tourists are violating normative social boundaries over what is considered appropriate use of public space. For example, the presence of tourists in public car parks such as Beresford St is threatening to social conventions not only, or even primarily, because they are taking up space. None of the locals we interviewed actually wanted to use this space. Rather, the presence of people and their clothes, toothbrushing, and shitting, threatened the cleanliness of all through the transgression of civil behaviour in public space; contact with the dirty makes one dirty, as Miller (1997) argued.

A UPE perspective on overtourism goes beyond a focus on social and ecological carrying capacity to analyse overtourism as place-based social conflict between tourists and hosts, thereby revealing how inequalities of class and political power displace the perceived negative impacts of tourism from privileged areas with greater access to state authorities and infrastructure onto poorer urban areas. This analysis contributes to the growing attention that tourism scholars are devoting to issues of social power, social inequality, and socially responsible travel. We need to shift the focus beyond how tourism can foster economic growth, to considering how structural inequalities shape who benefits and who bears the costs of tourism’s growth.

Concerns of overtourism were temporarily halted by Covid-19; however, plans for post-covid economic recovery centre a rebounding of the industry. It is unlikely we will see a transformation of the tourist industry of the scale that is needed in New Zealand to chart a path away from overtourism encounters. Authorities’ responses to overtourism in New Zealand and internationally often focus on how to encourage more respectful tourist behaviour, communication campaigns, technological tools and infrastructure provision (Atzori, Citation2020). The New Zealand government recently signalled a shift in language from ‘freedom camping’ to ‘responsible camping’, and tourists are encouraged to sign the ‘tiaki promise’, indicating that they will respect public space on their travels. But, as Cometta (Citation2021) argues, this managerial approach to fixing overtourism fails to recognise that overtourism is not just about numbers of tourists. A purely economic management of overtourism ignores the ways in which tourism commodifies and changes the character of public space, which can manifest in resentment toward particular tourists (such as xenophobia and class-based conflict). At the heart of these issues is a problem of neoliberal governance and on tourism delivering ‘economic benefit’ to the regions, while placing responsibility for managing tourist volumes on local territories. The problem then manifests in conflictual encounters between campers and locals. Placing the responsibility on individuals to camp ‘responsibly’, expecting local governments to police their way out of overtourism through by-laws that simply shuffle campers on to different areas, or relying on technological fixes that can have unintended consequences, continues the neoliberal management strategy of devolving responsibility to the individual and to under-resourced local governments, rather than developing a transformative vision for the inclusive use of public space.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shannon Aston

Shannon Aston is an Associate Transportation Planner for the California Department of Transportation with a background in sociology and history. His research interests are in the relationship between transportation policy, governance and the varied communities sharing the space.

Alice Beban

Alice Beban is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Massey University, Aotearoa New Zealand. She is an environmental sociologist, studying land rights, agricultural production and gender concerns to understand people’s changing relationships with land and water in the Mekong region and in New Zealand.

Vicky Walters

Dr Vicky Walters is a lecturer in Sociology at Massey University. Her research is largely based in South Asia and Aoteaora New Zealand and addresses issues of social inequality issues including, gender, urban sanitation and water governance, homelessness, disasters, caste, as well as questions of social inclusion, justice and democracy.

References

- Airey, D. (2015). Developments in understanding tourism policy. Tourism Review, 70(4), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2014-0052

- Atzori, R. (2020). Destination stakeholders’ perceptions of overtourism impacts, causes, and responses: The case of Big Sur, California. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100440

- Barcan, R. (2005). Dirty spaces: Communication and contamination in men’s public toilets. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 6, 7–23.

- Billante, V. (2010). Freedom camping management plan. Christchurch City Council.

- Brooker, E., &Joppe, M. (2014). A critical review of camping research and direction for future studies. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 20(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766714532464

- Caldicott, R., Scherrer, P., & Jenkins, J. (2014). Freedom camping in Australia: Current status, key stakeholders and political debate. Annals of Leisure Research, 17(4), 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2014.969751

- Camatti, N., Bertocchi, D., Carić, H., & van der Borg, J. (2020). A digital response system to mitigate overtourism. The case of Dubrovnik. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(8-9), 887–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2020.1828230

- Campermate. (2019). Our Story. https://www.campermate.co.nz/about/index.

- CCC. (2015). Christchurch City Council Freedom Camping Bylaw 2015. https://www.ccc.govt.nz/assets/Documents/TheCouncil/Plans-Strategies-Policies-Bylaws/Bylaws/CCCFreedomCampingBylaw2015-Amended.pdf

- CCC. (2019). Population. https://www.ccc.govt.nz/culture-andcommunity/christchurch/statistics-and-facts/facts-stats-and-figures/population-and-demographics/population/

- Collins, D., & Kearns, R. (2010). Pulling up the Tent Pegs?’ The Significance and Changing Status of Coastal Campgrounds in New Zealand. Tourism Geographies, 12(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903493647

- Collins, D., Kearns, R., Bates, L., & Serjeant, E. (2017). Police power and fettered freedom: Regulating coastal freedom camping in New Zealand. Social & Cultural Geography, 19(7), 1–20.

- Comer, R. (2019). Angry West Coast residents blockade bridge leading to overcrowded freedom camping site. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/110585093/thou-shall-not-pass-angry-west-coast-residents-blockade-bridge-leading-to-overcrowded-freedom-camping-site

- Cometta, Mose, Discussing Overtourism: Recognizing Residents’ Needs in Tourism Management in Ticino, Switzerland. Progress in French Tourism Geographies, Stock, Mathis, Springer, Switzerland, 2021.

- Cook, I. R., &Swyngedouw, E. (2012). Cities, social cohesion and the environment: towards a future research agenda. Urban Studies, 49(9), 1959–1979. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012444887

- Cook, I., & Whowell, M. (2011). Visibility and the policing of public space. Geography Compass, 5(8), 610–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00437.x

- Cornea, N., Véron, R., & Zimmer, A. (2017). Clean city politics: An urban political ecology of solid waste in West Bengal, India. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(4), 728–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16682028

- Cornish, S. (2019). Anger after freedom camper cleans undies in drinking fountain. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/anger-after-freedom-camper-cleans-undies-in-drinking-fountain/N6KMYQESJGUP4622L3KEJUQQ3U/

- Croll, A. (1999). Street disorder, surveillance and shame: Regulating behaviour in the public spaces of the Late Victorian British Town. Social History, 24(3), 250–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071029908568068

- Cropp, A. (2018a). Akaroa locals demand poo patrol to battle waste left by freedom campers. Stuff Media, January 22. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/100771514/poo-and-loo-paper-littering-akaroa-anger-locals-who-demand-tougher-action-on-freedom-campers

- Cropp, A. (2018b). Akaroa police officer threatens to arrest freedom campers caught defecating in public. Stuff Media, February 8. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/101270766/akaroa-police-officer-threatens-to-arrest-freedom-campers-caught-defecating-in-public

- Doshi, S. (2017). Embodied urban political ecology: five propositions. Area, 49(1), 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12293

- Devine, J., & Ojeda, D. (2017). Violence and dispossession in tourism development: A critical geographical approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1293401

- Douglas, J. A. (2014). What’s political ecology got to do with tourism? Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.864324

- Ekers, M., & Loftus, A. (2008). The Power of Water: Developing Dialogues Between Gramsci and Foucault. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26(4), 698–718. https://doi.org/10.1068/d5907

- Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1086/448181

- Freedom Camping Act. (2011). Freedom Camping Act, No 61. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2011/0061/latest/whole.html#DLM3886706

- Graefe, D., & Dawson, C. (2013). Rooted in place: Understanding camper substitution preferences. Leisure Sciences, 35(4), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.797712

- Hannam, K. (2002). Tourism and development I: Globalization and power. Progress in Development Studies, 2(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1191/1464993402ps039pr

- Kearns, R., Collins, D., & Bates, L. (2017). It’s freedom!”: examining the motivations and experiences of coastal freedom campers in New Zealand. Leisure Studies, 36(3), 395–408.

- Keenan, J. H. (2012). Freedom Camping Management: A case study of the Otago and Southland Regions of New Zealand [Thesis, Master of Planning]. University of Otago, New Zealand.

- Krippendorf, J. (1999). The Holidaymakers: Understanding the impact of leisure and Travel. Routledge.

- Law, T. (2016). Christchurch freedom camping sites likely to remain closed next summer. Stuff Media, April 21. https://www.stuff.co.nz/travel/news/79155462/christchurch-freedom-camping-sites-likely-to-remain-closed-next-summer

- LGNZ. (2018). Good Practice Guide for Freedom Camping. http://www.lgnz.co.nz/our-work/publications/good-practice-guide-for-freedom-camping/

- LINZ. (2017). Residential red zone areas. https://www.linz.govt.nz/crown property/types-crown-property/christchurch-residential-red-zone/residential-red-zone-areas

- Lofland, L. H. (1989). Social life in the public realm. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 17(4), 453–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124189017004004

- Mackenzie, D. (2017). Tourism eclipses dairy to become top export earner. Otago Daily Times, May 1. https://www.odt.co.nz/business/tourism-eclipses-dairy-become-top-export-earner

- McKinnon, I., Hurley, P. T., Myles, C. C., Maccaroni, M., & Filan, T. (2019). Uneven urban metabolisms: Toward an integrative (ex)urban political ecology of sustainability in and around the city. Urban Geography, 40(3), 352–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1388733

- McNeilly, H. (2019). ‘Ain’t no toilet in there’: New Zealand flush with fake ‘self contained’ bumper stickers. Stuff Media, February 19. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/110429938/aint-no-toilet-in-there-new-zealand-flush-with-fake-selfcontained-bumper-stickers

- Martin, R. (2019). Campervan inspections loophole: Call for government oversight. Radio New Zealand, January 9. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/379732/campervan-inspections-loophole-call-for-government-oversight

- MBIE. (2018). Responsible Camping Working Group Report. Wellington: MBIE. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/immigration-and-tourism/tourism/tourism-projects/responsible-camping/responsible-camping-working-group/

- Meier, C., & Mitchell, C. (2015). Freedom campers pack up after council hard word. Stuff Media, January 24. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/65372806/null

- Mitchell, C. (2015). Freedom campers’ unruly antics rile residents. Stuff Media, January 20. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/65246365/null

- Mitchell, D. (2003). The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. Guilford Press.

- Mols, A., & Pridmore, J. (2019). When citizens are “actually doing police work”: The blurring of boundaries in whatsapp neighbourhood crime prevention groups in the Netherlands. Surveillance & Society, 17(3/4), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i3/4.8664

- Morgan, D. (2002). A new pier for New Brighton: Resurrecting a community symbol. Tourism Geographies, 4(4), 426–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680210158155

- Nava, L.,Carr, N.,Miller, A., &Coetzee, W. (2022). Redefining ‘freedom camping’ in New Zealand: the role of the Rugby World Cup. Annals of Leisure Research, 25(1), 138–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2020.1818591

- Ojeda, A. B., & Kieffer, M. (2020). Touristification. Empty concept or element of analysis in tourism geography? Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 115, 143–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.06.021

- Rantala, O., & Varley, P. (2019). Wild camping and the weight of tourism. Tourist Studies, 19(3), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797619832308

- Rogerson, C., & Rogerson, J, School of Tourism & Hospitality, College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg, Bunting Road, Johannesburg, South Africa. (2020). Camping tourism: A review of recent international scholarship. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 28(1), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.28127-474

- Sanders, T., O’Neill, M., & Pitcher, J. (2010). Prostitution: Sex work, policy and politics. Sage.

- Spiller, K., & L’Hoiry, X. (2019). Visibilities and new models of policing. Surveillance & Society, 17(3/4), 267–271. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i3/4.13239

- Standards Association of New Zealand. (1990). New Zealand Standard: NZS 5465:2001: Self containment of motor caravans and caravans. https://shop.standards.govt.nz/catalog/5465:2001(NZS)/scope

- Stats, N. Z. (2023). International Travel Provisional. https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/international-travel-provisional/.

- Swanson, K. (2007). Revanchist urbanism heads south: The regulation of indigenous beggars and street vendors in ecuador. Antipode, 39(4), 708–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2007.00548.x

- Takahashi, L. (1998). Homelessness, AIDS, and stigmatization: The NIMBY syndrome in the United States at the end of the twentieth century. Oxford University Press.

- Tse, S., &Tung, V. W. S. (2021). Residents’ discrimination against tourists. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103060. PMC: 33041399.

- Tzaninis, Y., Mandler, T., Kaika, M., & Keil, R. (2021). Moving urban political ecology beyond the ‘urbanization of nature. Progress in Human Geography, 45(2), 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520903350

- Urry, J. (1990). The consumption of tourism. Sociology, 24(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038590024001004

- Van Beynen, M. (2015). A quiet night out with freedom campers. Stuff Media, April 12. https://www.stuff.co.nz/the-press/news/67689121/a-quiet-night-out-with-freedom-campers

- Williscroft, Colin, Akaroa: Is the historic town taking a hit for Christchurch?, The Press, 2018, https://www.stuff.co.nz/thepress/news/108212738/akaroa-is-the-historic-town-taking-a-hit-for-christchurch

- Zmyślony, P.,Kowalczyk-Anioł, J., &Dembińska, M. (2020). Deconstructing the overtourism-related social conflicts. Sustainability, 12(4), 1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041695