ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 outbreak and resultant economic crisis has led to governments in Europe taking extraordinary action to support citizens. Bodies such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO) recommend such measures should include targeted support for the most affected population groups. Women form one of these groups, with disproportionate impacts on their employment and economic resources already documented. Although the disruption brought about by the COVID-19 crisis has the potential to reshape gender relations for everyone’s benefit, there are concerns that the crisis will exacerbate underlying gender inequalities. Though these impacts are likely to be felt globally, public policy has the potential to mitigate them and to ensure a gender-sensitive recovery from the crisis. This paper introduces a gendered lens on the employment and social policies European countries have established since the crisis, with a brief comparative analysis of short-time working schemes in four countries – Germany, Italy, Norway, and the UK. Ongoing research seeks to extend the comparative, gendered analysis of the design, access and impacts of COVID-19 employment and social policies across Europe.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

While men are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 disease (Global Health 50-50 Citation2020), the fallout from the pandemic has led to grave consequences for women: mounting evidence points to reduced access to sexual and reproductive health services, increased domestic violence, and – our area of focus – disproportionate effects on women’s livelihoods (Wenham et al. Citation2020).Footnote1

Previous economic crises resulted in men’s jobs and incomes being harder hit initially, since men often work in industries closer tied to economic cycles, like construction and manufacturing (Alon et al. Citation2020), while post-crisis austerity policies affected women’s employment, due to their concentration in heavily cut public sector employment (Rubery Citation2015). This demonstrates two layers of gendered impacts on employment – one from the crisis itself, and another from the policies pursued in response to it.

So far, the COVID-19 crisis is distinct from previous crises in its gendered impacts on employment. On the one hand, women are over-represented among essential health and social care workers and may receive greater recognition due to their increased visibility (Blaskó et al. Citation2020). However, these workers are more exposed to COVID-19 and, in many countries, insufficiently protected. Also, many of the service sectors disproportionately affected by closures necessitated by social distancing and confinement are dominated by female workers – especially hospitality and tourism. Indeed, according to ILO data, in 2018, 84% of employed women were working in the service sector across Europe, compared to 61% of men (Blaskó et al. Citation2020). Accordingly, women are over-represented in closed sectors across the EU, ranging from female shares of 49% (Greece) to 69% (Latvia) (Fana et al. Citation2020).

Women are also over-represented in non-standard, precarious forms of employment that face higher risk of job loss both in the initial lockdown period and as the economic crisis deepens. Women in the UK, Germany and US are already more likely than men to have entered unemployment or lost earnings (Adams-Prassl et al. Citation2020). This loss of income is likely to be especially consequential for women, who typically earn less than men, have less access to savings and wealth (Schneebaum et al. Citation2018) and are more likely to be poor (Barbieri et al. Citation2016). Gender intersects with wider structural inequalities which place some women – including single mothers and BAME women – at greater risk of poverty.

Another unique feature of the COVID-19 crisis is the enormous impact on households with children due to school and nursery closures necessitated by lockdowns and social distancing. Households with children must find ways to combine paid work with the time-intensive work of providing care and home-schooling. Much of this falls to women, due to social norms (many in Europe believe that women are responsible for childcare and housework and men for paid work (Blaskó et al. Citation2020)) and the fact that women in heterosexual couples typically earn less and/or work fewer hours (Adams-Prassl et al. Citation2020). Researchers predict large rises in female unemployment and the gender pay gap (Alon et al. Citation2020), already evidenced in the US and Canada where women with children are more likely than men with children to have reduced their hours or left employment during the crisis (Collins et al. Citation2020; Qian and Fuller Citation2020).

Policy responses

The purpose of welfare states is to provide a ‘buffer’ between citizens and economic risks. In the current crisis, the spotlight has turned on different countries’ approaches and their comparative success. Given the disproportionate impacts just described, there is an urgent need to apply a gendered lens to the employment and social policies implemented in European countries to answer two crucial questions: (i) are the crisis-response policies contributing to widening or narrowing gender inequalities?; and (ii) will the longer term policies, designed to combat the post-pandemic recession, widen or narrow gender inequalities?

Comparative social policy research generally understands the differences between countries’ social policies through the lens of welfare regimes. Countries’ varied historical, political, and institutional features give rise to different systems of social policy, largely created in the aftermath of the second world war, which shape the response to socio-economic challenges (Scharpf and Schmidt Citation2003). Overlaid onto existing gender relations, such as gender segregation of employment, the division of unpaid labour, and gender role ideologies, patterns of welfare state intervention have produced divergent outcomes for women, both directly and indirectly, in particular through family policies, state-provided childcare, and public employment (Karamessini and Rubery Citation2013). European welfare regimes can be characterised by their underlying gender logic, from the ‘strong male breadwinner’ model of Germany and diverse ‘family models’ of Southern Europe, to the ‘earner-carer’ regime in Nordic countries and the individualised model of Liberal welfare states (e.g. Daly and Rake Citation2003).

Interventions since the COVID-19 crisis have focused on supporting business, employment retention, workplace safety, and measures to prevent social hardship. While the pandemic context of current measures is unprecedented, the literature on gender and the welfare state offers clues as to the country-specific logic behind these interventions and how a gendered lens may be applied to them. Policy design can be assessed through theoretically driven metrics, which rate policy packages along dimensions relevant to gender equality. For example, Ray et al’s (Citation2010) comparison of parental leave policies rates them according to the conditions surrounding how leave is split between parents. Eligibility and access can be assessed by comparing levels of eligibility to support among different groups (such as men and women) (O’Brien et al. Citation2020) or by examining patterns of uptake (Ghysels and Van Lancker Citation2011). Gendered impacts can be assessed through analysis of country level data on policies and aggregate indicators of gender inequality in the longer term.

Our research project incorporates these insights into a comparative analysis of the gendered design, access and impacts of COVID-19 employment and social policies in Europe, as well as longer-term policies designed to combat the post-pandemic recession. This gendered analysis focuses on the extent to which policies: acknowledge men’s and women’s different structural positions in the economy and society (such as women’s over-representation in low paid and non-standard work); reflect and reinforce existing norms and expectations about male and female labour market and household activities (for example, women’s greater likelihood to undertake childcare); and treat care as an integral part of the economy.

At this early stage, the present paper reports preliminary comparative analysis of the gendered design of one common COVID-19 social policy intervention across European countries – the short-time work scheme. We focus on four contrasting welfare regimes – the UK (a Liberal regime), Germany (Continental regime), Norway (Nordic regime) and Italy (Southern regime). Future research will explore policy design in the areas of employment, childcare and poverty for a broader group of European countries as well as addressing issues of access and impacts.

Gender issues in the design of short time work schemes

All countries in Europe have implemented some version of a ‘short time work’ (STW) scheme to support workers’ incomes if they are unable to work or demand for their work is reduced due to social distancing and business closures (Eurofound Citation2020). These schemes intend to help workers retain jobs and were successful after the 2008 crisis, preserving an estimated 580,000 jobs in Germany (Hijzen and Martin Citation2013). Fifty million workers in Europe were participating in STW schemes in April 2020 (Müller and Schulten Citation2020). The European Commission recognises the importance of these schemes and has provided €100 billion in support.

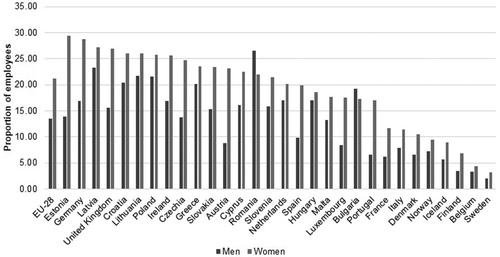

There are five key issues from a gender perspective (see ). Given women’s over-representation among low-wage workersFootnote2 across Europe (see ), the first issue is whether schemes provide adequate compensation and, in particular, whether they include means testing or a minimum threshold designed to sustain a decent income for low-wage workers. Such a focus potentially mitigates the risk of low-paid women becoming more economically vulnerable as a result of the crisis.

Figure 1. Low wage earners as a proportion of all employees, by gender, Europe, 2014. Source: Eurostat, Structure of Earnings Survey, 2014.

Table 1. Gendered features of COVID-19 STW schemes in UK, Norway, Germany and Italy.

The level of initial compensation varies markedly: 100% in Norway, 80% in Italy and the UK, and just 60% in Germany (Müller and Schulten Citation2020: 6). However, there are further rules that affect the amount of earnings replacement. In Norway, the 100% compensation only applies from the third to the twentieth day (Müller and Schulten Citation2020: 6). Thereafter, it is reduced, yet makes notable provision for low earners: those with salaries of 300,000 NOK (approx. €26,500) and below receive 80% of wages while those earning between 300,000-600,000 NOK (€26,500-€53,000) receive 62.4% (ETUC Citation2020: 18). This means women in low-wage jobs are in a relatively strong position, receiving between 80% and 100% of previous earnings during temporary displacement. In Italy, while the uniform 80% rate of compensation appears high, the scheme has a relatively low monthly cap – just €1,129.66 for monthly gross wages above €2,159.48, which is less than half the cap in the UK for example (€2,790) (Müller and Schulten Citation2020: 7). The low initial compensation level in Germany improves over time in an effort to support those suffering income losses for more than four months (70%) and more than seven months (80%) (Müller and Schulten Citation2020: 5).Footnote3 Further analysis is needed to disentangle the gendered effects of this policy on job retention once labour force survey data are available.

None of the four countries apply a minimum threshold to the compensation payment. This is likely to be a particularly gendered issue in Germany and the UK where large proportions of women are low paid (see ). This contrasts with several European countries that have fixed the national minimum wage as the minimum payment, thereby ensuring a decent living standard for the lowest paid (Eurofound Citation2020).Footnote4 Interrogation of the legal issues suggests that while STW compensates for lost earnings, the compensatory income ought not to be treated as a form of earnings covered by minimum wage rules.Footnote5 The problem, however, is that this interpretation only considers the ‘price function’ of a minimum wage and ignores its equally valid purposes in supporting living standards and ensuring gender equity (Rubery et al. Citation2021).

The second issue is how the calculation of replacement income treats periods of family-related leave. Calculations can be based on salary, gross pay at the time of the claim, or average pay across a period prior to the claim. Since maternity pay is often lower than normal pay, for women who were on maternity leave during the calculation period, this may produce inadequate replacement income, effectively penalising women for taking leave. This was the case when the UK’s STW scheme was initially launched. After pressure from campaign groups, UK guidance changed from 1st July and for people who were on maternity leave prior to a claim, replacement income is now based on salary, effectively exempting the leave period (Maternity Action Citation2020). However, the calculation method for the Self Employed Income Support Scheme in the UK still does not exempt maternity leave and this is now being raised as a case of indirect sex discrimination.Footnote6 In Norway, maternity leave is not exempt from replacement income calculations,Footnote7 but since maternity pay is more generous this implies less of a penalty. In Germany, replacement income is based on earnings before the period of leave (Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend Citation2019).

A third issue is non-standard employment, including temporary, part-time and agency employment. While few STW schemes single out vulnerable workers or explicitly acknowledge gender segregation in employment, some focus support on businesses particularly impacted, and most extend it to non-standard workers (Müller and Schulten Citation2020). For example, Germany’s kurzarbeit STW scheme, in place for many years, was extended to temporary agency workers. The inclusion of non-standard workers is important from a gender perspective due to women’s concentration in these forms of employment and the over-representation of these forms of employment within shut down sectors. However, there are two notable exceptions. In Italy, domestic workers such as housekeepers, babysitters, or caretakers, most of whom are women, cannot access the STW scheme (ILO Citation2020a). Employers and trade unions have called on government to include domestic work as part of ‘essential services’ (ILO Citation2020a). The ‘indennità per lavoratori domestici’ (allowance for domestic workers) was subsequently introduced but only provides €500 per month for April and May. Moreover, this was only available to domestic workers with a valid employment contract for at least 10 weekly hours, active before February 23 (INPS Citation2020), therefore unavailable for short hours workers and the many migrants in informal work. In Germany, people in ‘mini-jobs’ are not eligible for the STW scheme. This is a major category of employment for women, especially for working mothers, accounting for around one in four women in employment around 28% of women in employment, compared to 11% of male employment. Mini-jobs are exempt from direct social securityFootnote8 (the reason for exclusion from kurzarbeit) and are typically poorly paid with poor compliance with labour regulations (Weinkopf Citation2015). Their exclusion from COVID-19 income protection exacerbates existing inequalities faced by women in mini-jobs.

The extent to which STW schemes will allow women in non-standard employment to retain their jobs longer term is an open question. When schemes end, the risk of unemployment is high in sectors that continue to be affected by the crisis. At the time of writing, the UK scheme is due to end in October 2020. Norway’s scheme is also six months in duration, Germany’s is likely to be extended to 24 months, while Italy’s is also one year (Müller and Schulten Citation2020). Research on job protection schemes after the 2008 crisis shows that while employment rates among permanent, full time employees tended to return to pre-crisis levels, non-standard workers were typically not retained (Hijzen and Venn Citation2011). Employers are likely to view these workers – many of them women, including with childcare responsibilities – as more disposable once the STW scheme no longer supports them. Such impacts can be assessed in the future by analysing rates of employment over time by gender and contract type for those who have accessed STW schemes.

Fourthly, schemes also vary in the extent to which hours can be reduced. This is important since women are more likely to require flexible scheduling of working hours due to uncertainties over childcare provision. In the UK, the default assumption in the initial design of the scheme was that temporarily laid off workers could not work at all, though this was subsequently changed to allow for reduced hours. Norway’s temporary layoff approach has a similar ‘all or nothing’ logic, while Italy and Germany offer income replacement for hours reduction. A scheme offering reduced hours is more gender-sensitive because it enables more mothers to stay in work on reduced hours. Moreover, a reduced hours approach could spread working hours among employees, avoiding mass redundancies and certain (likely male) workers hoarding available hours.

The fifth issue concerns support for childcare. Most COVID-19 policy measures focus on supporting business, income, and employment (Eurofound Citation2020), with little acknowledgement of school closures or support for parents or childcare providers. A notable positive example is Germany’s higher STW compensation for workers with children (at the rates of 67%, 77% and 87% rather than 60%, 70% and 80%) (ETUC Citation2020), increased child benefit to vulnerable families, and a €300 per child ‘family bonus’ (ILO Citation2020b). Italy and Norway provide extended parental leave (with an option of a childcare allowance in Italy) (Eurofound Citation2020). In the UK, while the government belatedly acknowledged that STW could be used for childcare purposes, and schools and nurseries stayed open for children of essential workers, there was no further acknowledgement of childcare. Moreover, none of the policy approaches studied acknowledge the heightened impacts of care demands and shortages on women workers.

Overall, there are critical country differences in policy sensitivity towards gender inequalities. All four countries have gender-insensitive features in the five STW issues examined, with better performance in Norway and worse in the UK. Whether intentionally or not, all four schemes are somewhat gender-sensitive in their acknowledgement of non-standard employment. However, the lack of explicit support for low-paid workers (except in Norway), exclusion of key categories of female-dominated non-standard employment (in Germany and Italy), and the way periods of caregiving leave are treated reveal male-centred assumptions about the reference worker for policy design. Notably absent across these COVID-19 social policies is acknowledgement of care as an integral part of the economy requiring support in a crisis, alongside employment and business.

Conclusion

The pandemic and resultant economic crisis are already having disproportionate impacts on women’s livelihoods and ability to engage in paid work. Public policies have the potential to either make these gendered impacts worse or mitigate them. This paper has introduced a gendered lens onto the design of COVID-19 employment and social policies so far pursued by European countries in this time of crisis. A brief comparison of STW schemes in four focal countries highlighted their gendered assumptions which leave women more vulnerable to economic risks. STW schemes largely assume a normative (male) worker and leave the gendered division of domestic labour unchallenged, which may contribute to a widening of gender inequalities. While these gendered assumptions are by no means novel, the extraordinary circumstances draw them into focus.

Answering our second research question (Will the longer term policies, designed to combat the post-pandemic recession, widen or narrow gender inequalities?) – requires sustained attention to access to support and differential vulnerability to ongoing impacts as the crisis deepens. For example, a key question is whether STW schemes do in fact allow people to keep their jobs beyond the immediate crisis period and whether this is equally distributed between men and women in different types of employment. Longer term, a comparative approach can highlight the mitigating or widening role of countries’ policy approaches on inequalities including women’s employment rates, the gender pay gap, and the quality of women’s employment including career progression, decent and secure pay and regular hours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rose Cook

Rose Cook is a Senior Research Fellow at the Global Institute for Women's Leadership, King's College London. Her research interests are in comparative social policy, gender, education and work. Rose is the lead investigator of a new project exploring the gendered design and impacts of COVID-19 related social policies, funded by the UK's Economic and Social Research Council.

Damian Grimshaw

Damian Grimshaw is Professor of Employment Studies at King's Business School and Associate Dean for Research Impact. Previously he was Director of the Research Department at the International Labour Organisation in Geneva (2018–19) and Deputy Director of the Work and Equalities Institute at the University of Manchester. Recent publications include Making Work More Equal (2017, Manchester University Press) and ‘Market exposure and the labour process: The contradictory dynamics in managing subcontracted services' in Work, Employment and Society (2019).

Notes

1 While we acknowledge that the term ‘gender’ encompasses more than the binary difference between sexes and there are likely to be impacts of the crisis on people with various gender identities, our project focuses on differences between men and women.

2 Low-wage work is defined as earnings less than two thirds of the median wage.

3 A further issue especially relevant in Germany is that trade unions have been successful in increasing the compensation level through collective agreements for many workers – up to 90% and above in local government, metalworking and chemicals for example (Müller and Schulten Citation2020). However, women are more likely than men to work in low-wage industries where fewer workers are covered by collective agreements, which generates another source of gender inequality.

4 Examples of countries that have set the statutory minimum wage as the lower limit for replacement income include Estonia, France, Lithuania, and Portugal.

5 For the UK, for example, official guidance states that employees are ‘not entitled to’ the minimum wage if they are not performing any work or training for their employer. See: https://www.acas.org.uk/coronavirus/furlough-scheme-pay/pay-during-furlough.

7 Communication with Anne Skevik Grødem, Institut for Samfunns-Forskning (Norway), 3 August 2020.

8 Payment of contributions is voluntary and so only a small share of mini job workers are covered (Weinkopf Citation2015).

References

- Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M. and Rauh, C. (2020) ‘Inequality in the impact of the Coronavirus shock: evidence from real time surveys’, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 13183.

- Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J. and Tertilt, M. (2020) This time it’s different: the role of women’s employment in a pandemic recession. Available from: https://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~mdo738/research/ADOT_0720.pdf [Accessed 31 July 2020].

- Barbieri, D., Huchet, M., Janeckova, H., Karu, M., Luminari, D., Madarova, Z., Paats, M. and Reingardė, J. (2016) Poverty, Gender and Intersecting Inequalities in the EU: Review of the Implementation of Area A: Women and Poverty of the Beijing Platform for Action, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Blaskó, Z., Papadimitriou, E. and Manca, A. R. (2020) How Will the COVID-19 Crisis Affect Existing Gender Divides in Europe?, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2019) Parental allowance, parental allowance plus and parental leave. Available from: https://www.bmfsfj.de/blob/139908/72ce4ea769417a058aa68d9151dd6fd3/elterngeld-elterngeldplus-englisch-data.pdf [Accessed 3 Sep 2020].

- Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L. and Scarborough, W. J. (2020) ‘COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours’, Gender, Work & Organization [online first]. doi:10.1111/gwao.12506.

- Daly, M. and Rake, K. (2003) Gender and the Welfare State, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Eurofound (2020) COVID-19: Policy Responses Across Europe, Dublin: Eurofound.

- European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) (2020) Short time work measures across Europe. Available from: https://www.etuc.org/sites/default/files/publication/file/2020-05/Covid_19%20Briefing%20Short%20Time%20Work%20Measures%2024%20May.pdf [Accessed 31 July 2020].

- Fana, M., Tolan, S., Torrejon, S., Urzi, C. and Fernandez-Macias, E. (2020) The COVID confinement measures and EU labour markets. JRC Technical Reports, European Commission.

- Ghysels, J. and Van Lancker, W. (2011) ‘The unequal benefits of activation: an analysis of the social distribution of family policy among families with young children’, Journal of European Social Policy 21(5): 472–485. doi:10.1177/0958928711418853.

- Global Health 50-50 (2020) Sex, gender and COVID-19. http://globalhealth5050.org/ covid19/ [Accessed 20 Aug 2020].

- Hijzen, A. and Martin, S. (2013) ‘The role of short-time work schemes during the global financial crisis and early recovery: a cross-country analysis’, IZA Journal of Labor Policy 2(1): 1–31.

- Hijzen, A. and Venn, D. (2011) The Role of Short-Time Work Schemes During the 2008–09 Recession. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 115, Paris: OECD Publishing.

- ILO (2020a) Measures adopted in Italy to support workers, Policy Brief¸ 28-03-20.

- ILO (2020b) COVID-19 and the world of work: country policy responses. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/regional-country/country-responses [Accessed 3 Sep 2020].

- IMF (2020) ‘Kurzarbeit: Germany’s short time work benefit’. Available from: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/06/11/na061120-kurzarbeit-germanys-short-time-work-benefit [Accessed 3 Sep 2020].

- INPS (2020) ‘Indennità lavoratori domestici’. Available from: https://www.inps.it/docallegatiNP/Mig/Allegati/Brochure_Informativa_LD.pdf [Accessed 3 Sep 2020].

- Karamessini, M. and Rubery, J. (2013) Women and Austerity: The Economic Crisis and the Future for Gender Equality, London: Routledge.

- Maternity Action (2020) ‘FAQs: Covid-19 – rights and benefits during pregnancy and maternity leave’. Available from: https://maternityaction.org.uk/covidmaternityfaqs/ [Accessed 3 Sep 2020].

- Müller, T. and Schulten, T. (2020) Ensuring Fair Short-Time Work: A European Overview, Brussels: European Trade Union Institute.

- O’Brien, M., Connolly, S. and Aldrich, M. (2020) Eligibility for Parental Leave in EU Member States, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Qian, Y. and Fuller, S. (2020) ‘COVID-19 and the gender employment gap among parents of young children’, Canadian Public Policy [online first]. doi:10.3138/cpp.2020-077.

- Ray, R., Gornick, J. C. and Schmitt, J. (2010) ‘Who cares? assessing generosity and gender equality in parental leave policy designs in 21 countries’, Journal of European Social Policy 20(3): 196–216.

- Rubery, J. (2015) ‘Austerity and the future for gender equality in Europe’, ILR Review 68(4): 715–741.

- Rubery, J., Grimshaw, D. and Johnson, M. (2021) ‘Minimum wages and the multiple functions of wages’, in I. Dingeldey, D. Grimshaw and T. Schulten (eds.), Minimum Wages and Collective Bargaining, London: Routledge.

- Scharpf, F. W. and Schmidt, V. A. (2003) Welfare and Work in the Open Economy Volume I: From Vulnerability to Competitiveness in Comparative Perspective, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schneebaum, A., Rehm, M., Mader, K. and Hollan, K. (2018) ‘The gender wealth gap across European countries’, Review of Income and Wealth 64(2): 295–331.

- Weinkopf, C. (2015) ‘Women’s employment in crisis: Robust in crisis but vulnerable in quality’, Revue de l’OFCE 133(2): 189–214.

- Wenham, C., Smith, J., Davies, S. E., Feng, H., Grépin, K. A., Harman, S., Herten-Crabb, A. and Morgan, R. (2020) ‘Women are most affected by pandemics — lessons from past outbreaks’, Nature 583(7815): 194–198.