ABSTRACT

In the context of successive global crises and rising household food insecurity in wealthy European countries there is renewed attention to the role of school meals as a welfare intervention. However, little is known about the extent to which school meals are a resource for low-income families living in different contexts. Drawing on a mixed methods study of food in low-income families in three European countries, this paper adopts a realist ontological stance and an embedded case study approach to address this question. The research concerns low-income families with children aged 11–15 years in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis in the UK, Portugal and Norway. Based on a comparative, multi-layered analysis of macro-, meso- and micro-level contexts, we argue that publicly funded, nutritious school meals protect children from the direct effects of poverty on their food security, whilst underfunded and weakly regulated school food provision compounds children’s experiences of disadvantage and exclusion. The paper concludes with recommendations for public policies that conceptualise school meals as a collective resource, like education, to which young people as bearers of the right to food are entitled.

Introduction

The global financial crisis of 2008, subsequent ‘austerity’ measures implemented in some countries and, more recently, the Covid-19 pandemic, have impacted unequally on the poorest in our societies (Bambra et al. Citation2021). Against this backdrop, rising levels of income poverty, food insecurity and school closures in many European countries have focussed public and political attention on the role of school meals as a health and welfare intervention and as a human right.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) recognises the role that schools can and do play in operationalising the ‘right to food’ that is included in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (FAO Citation2021). The right to food obliges signatories to respect, protect and fulfil people’s regular and dignified access to food that is both nutritious and culturally appropriate (Dowler and O’Connor Citation2012; Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti Citation2020). However, whilst alternative ways of delivering school meal provision were implemented by governments globally during Covid-19 lockdowns (WFP Citation2020), Human Rights Watch (UK) warned that the ‘uneven’ approach failed to guarantee this right for children (HRW Citation2020; O’Connell and Brannen Citation2020).

In the UK, where schools closed to most children from March to July 2020 and January to March 2021 (Roberts and Danechi Citation2022), footballer Marcus Rashford was moved to establish a Child Poverty Taskforce, a coalition of charities and food businesses that successfully campaigned to increase entitlement to free school meals for some previously excluded groups of children (for example, those whose parents have irregular migration status) and to extend funding for provision into school holidays. Elsewhere in Europe, school meals provision in the pandemic has also featured in public discussion, within broader concerns about how Covid-19 led to widened inequalities. In Portugal, for example, where schools closed for over three months, the media reported that some schools kept canteens open, serving takeaway meals, while home delivery of school meals was set up in other areas (Bizarro and Ferreiro Citation2021). In other countries, like Norway, where there is no tradition of schools providing meals, recent media reports suggest the government plans to revise its policies (e.g. Capar Citation2021).

Yet, despite growing public and media awareness of the importance of school meals for children in contexts of crisis and disadvantage, there is a paucity of research examining the factors that shape children’s access to and experience of school meals in low-income families, or how they contribute to their diets and food practices, with none to our knowledge taking a comparative perspective.

Adopting a multi-level framework, this paper examines the extent to which school meals may provide a resource to children and their families in mitigating the effects of poverty on children’s diets and food practices. It draws on a larger international study of Families and Food in Hard Times (2014-2019) that was carried out in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The research used a range of methods, including in-depth qualitative research with young people and their parents (usually mothers), in 133 low-income families in three European countries: the UK, Portugal and Norway, countries selected primarily to provide for a contrast of contexts in relation to conditions of austerity in the years 2010–2014. Although the study was not designed to investigate the ways that schools organise meals, differences in the three countries’ education systems, cuisines and eating patterns provide an opportunity to understand the contextual features that shape children’s diets and food practices. In the comparative case approach adopted, both national policies and school level practices have emerged as important influences.

Background

Families, poverty and food insecurity in the UK, Portugal and Norway

The three European countries studied are all modern welfare states that differ in some important respects. The UK has a neoliberal welfare regime, whilst Portugal is described as a ‘familialist’ welfare state and Norway typifies the Nordic comprehensive welfare model (Esping-Andersen Citation1990). Compared to Portugal, the UK and Norway are wealthy countries. Norway, unlike the other two countries, is relatively egalitarian and has low levels of relative poverty (households below 60% median income), whereas rates of relative income poverty in the UK and Portugal are above the EU average. The EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) is the main source of information on living standards in the EU, collecting nationally representative and cross-country comparable statistics on income and social inclusion. According to the EU-SILC (2017), the time at which the fieldwork was undertaken, the ‘at risk of poverty’ rate (proportion of the population living in households with an income below 60% of median income) in the EU was 16.9% (after social transfers) (Eurostat Citation2017b). It was above this in both the UK (17.0%) and Portugal (18.3%) and below it in Norway (12.3%) (Ibid). Cross-country comparative data from the EU-SILC consistently finds that rates of relative income poverty are higher among children (people aged under 18 years) than the general population, with a few exceptions (Bradshaw and Chzhen Citation2011). Although some estimates suggest child poverty rates in Norway are lower than for the general population, according to the EU-SILC (2017), the at risk of poverty rate for children was higher than for the general population in all three countries, though the difference in Norway was much smaller, with rates of 27.4% in the UK, 24.2% in Portugal and 16.4% in Norway (Eurostat Citation2017c; O’Connell and Brannen Citation2021).

Both the UK and Portugal were significantly affected by the 2008 financial crisis and imposed so-called ‘austerity measures’ that reduced the welfare state and social security benefits in ways that impacted low-income households, especially families with children (Chzhen Citation2014). In the UK, analyses of the cumulative distributional consequences of national austerity measures conclude that cuts to welfare spending have disproportionately affected families with children, particularly lone-parent families, which make up around 25% of all families with children in the UK (e.g. Hood and Waters Citation2017; Tucker and Stirling Citation2017; Tucker Citation2017; Portes Citation2018). In Portugal, there is also evidence that austerity policies disproportionately impacted families with children and led to increases in child poverty (Wall et al. Citation2015). With its sovereign wealth fund, Norway was less affected by the financial crisis, and did not impose austerity measures. However, neoliberal notions that paid work should be the central route to welfare had already gained political momentum in the 1990s (Richards et al. Citation2016). In October 2013, the majority centre- left coalition government lost office and was replaced by a minority right- wing coalition. Despite Norway’s relatively generous welfare state, those who live in households whose main income is from welfare benefits are overrepresented in the low-income group, especially lone-parent households. In 2016, 28.5% of lone- parent households belonged to the low-income group compared with 8.6% of dual-parent households (Statistics Norway Citation2018). Furthermore, underemployment and poverty are highly associated with minority ethnic status, and more than half of all children living in households with persistent low income have an immigrant background (Statistics Norway Citation2014).

Reflecting rising rates of relative income poverty in some European countries in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, there is also evidence that household food insecurity rose during this period (Loopstra et al. Citation2016; Davis and Geiger Citation2017). The FAO defines individual and household food insecurity as ‘being unable to consume an adequate quality or sufficient quantity of food for health, in socially acceptable ways, or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so’ (Dowler et al. Citation2001, 12). According to the FAO (Citation2008:1), food security is underpinned by four ‘pillars’ or dimensions, namely availability, access, utilisation and stability. For food security to be realised, all four of these dimensions must be fulfilled simultaneously. Reflecting the right to food, there is an emphasis in this conceptualisation of food security not only on its physical or material aspects but on its sociocultural and psychosocial dimensions, namely the social acceptability of food and dignity in its acquisition and consumption.

For industrialised countries, where food is usually bought from shops, household food security ‘implies that people have sufficient money to purchase the food they want to eat’ (Dowler and O’Connor Citation2012, 45). Whilst comparative data about the ‘affordability’ of food are limited, food prices are generally far higher in Norway than in the UK and Portugal (Eurostat Citation2019): Norwegian prices are more than 20% above the EU average, whereas Portugal’s and the UK’s are 20% below. However, wages are much lower in Portugal. In the UK, there are large disparities between the food spending of those at the lower and higher ends of the income spectrum: official statistics show that an average of 10.6% of household income was spent on food between 2017 and 2018, compared with 15.2% for the lowest 20% of households (Defra Citation2020). Since food price increases disproportionately affect households with smaller incomes, part of the explanation for growing food insecurity in parts of Europe may be the rise and volatility of food prices relative to wages, especially following the food price shock of 2007–8 (Reeves et al. Citation2017).

Although methods of measurement vary, and comparative data are limited, there is evidence that rates of food insecurity vary between and within European countries (ibid; O’Connell and Brannen Citation2021). The FAO’s international, cross-sectional survey, Voices of the HungryFootnote1, based on around 2000 households per year in each country, includes our three study countries (FAO Citation2016). Analysis of 2017 data suggests that rates of ‘severe’ food insecurity (reducing quantities, skipping meals and experiencing hunger in the past year) are slightly higher among the general population in Portugal (3.7%) than in the UK (3.4%), whilst those in Norway are low (1.2%) (FAO Citation2018). Secondary analysis of the same survey suggests that, in all three countries, families with children (defined in this survey as those aged 15 years and under) are at greater risk of severe food insecurity compared with all households (Pereira et al. Citation2017). The largest difference is found in the UK, where the rates of food insecurity among families with children (10.4%) is almost three times higher than that of all households. Families with children in the UK are also more than twice as likely to be food insecure compared to families with children in Portugal (4.9%) and around four times more likely to be food insecure than those in Norway (1.7%)Footnote2 (Pereira et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, according to our previous research, analysing a different indicator of food insecurity (inability to afford a meal containing protein every other day) in the EU-SILC (O’Connell and Brannen Citation2021, ibid.), poor lone-parent families, in the UK and Norway, but not in PortugalFootnote3, are much more likely to be food insecure than poor couple families. This is likely to reflect the greater depth of poverty among the UK and Norwegian lone parents, and to contribute to high levels of food insecurity among families in the UK, which has one of the highest rates of lone parenthood in Europe.Footnote4 However, among the limitations of these ways of measuring food insecurity are that, whilst they capture absolute deprivation in food and nutritional intake, they do not provide evidence about other aspects of the experience, such as the consumption of culturally inappropriate food, or its procurement in uncustomary ways (O’Connell et al. Citation2019a).

Approaches to school food provision

Schools have long been recognised as determinants of children’s health and diets, both directly, as food providers, and through the delivery of health and food education (Morrison Citation1995; Currie et al. Citation2012). School food policy and practice is a highly politicised and evolving field (Gustafsson Citation2002; Mikkelsen et al. Citation2005; Morgan Citation2006; Poppendieck Citation2010) addressed by a diversity of disciplinary and policy approaches. In the global North, given the (over) abundance of (unhealthy) food, school food policy has in recent decades been framed as a health intervention aimed at tackling rising rates of overweight and obesity (Gustafsson Citation2002; Oostindjer Citation2017). Research has also focussed on the relationship between school food and cognitive function, in-class behaviour and learning outcomes (e.g. Earl and Lalli Citation2020). Economists have also examined school meals in terms of their wider costs and benefits, in terms of family budgets (e.g. Huang and Barnidge Citation2016; Holford and Rabe Citation2020), potentially freeing up resources and impacting positively on food intake at home, including of other household members (e.g. Bhattacharya et al. Citation2006, 448–9) and the long term effects of school meals provision on children’s educational attainment, health and lifetime income (Lundborg et al. Citation2021).

Social scientists have also addressed children’s experiences of school mealtimes and their social and psychosocial dimensions (Daniel and Gustafsson Citation2010; Punch et al. Citation2010; Wills et al. Citation2016). Recognising that food is a means for the expression of personal and group identity, especially for children in consumerised societies (James Citation1979; Warde Citation1997; Fischler Citation1988), school meals may be understood as a form of ‘institutional commensality’ (Grignon Citation2001) that can include and exclude children from their communities (Andersen et al. Citation2017; Osowski and Sydner Citation2019). Whilst some countries provide ‘universal’ school meals that are free at the point of delivery for all children in education, others have systems of means testing, in which children’s entitlements to free meals are determined through their parents’ incomes or receipt of particular benefits. In these contexts, for example the US and the UK, research has identified ‘free school meals’ as sites of stigmatisation, through which children may be identified as poor and made to feel ashamed (Poppendieck Citation2010; Farthing Citation2012; O’Connell et al. Citation2019b).

The study: context and methodology

Families and Food in Hard Times, 2014–2019, was a mixed methods study that sought to examine the food practices of children and parents in low-income families and how these were affected in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis in the UK, Portugal and Norway (O’Connell and Brannen Citation2021). The study was conceived and funded in a period when increasing evidence emerged in the UK and elsewhere in ‘austerity Europe’ of children going hungry and of families going to food banks. Given the paucity of comparative evidence, including about children and families, the research set out to investigate the social conditions in which low-income families with children were unable to feed themselves adequately and the consequences for parents’ and children’s food practices and other aspects of their lives. Three European countries were selected to provide for a contrast of contexts in relation to conditions of austerity, with high-, medium- and low- impacts respectively: the UK, Portugal and Norway.

The study adopted a realist ontological stance. While this stance is not wedded to any particular theory or method (Porpora Citation2015), when combined with comparative case analysis it may produce a multi-layered understanding of the conditions and processes that shape social and individual outcomes (Brannen Citation2019; Bergene Citation2007).

According to our embedded case study design (Yin Citation2003), we conceptualised and examined reality at three intersecting analytical levels: the macro-level of the state was studied via secondary analysis of international and national datasets and published reports. The meso-level of the locality was studied through an examination of school meal practices and other services in the study areas. The micro-level of the household that included children age 11–15 and their parents was studied qualitatively; 45 low-income familiesFootnote5 in both the UK and Portugal and 43 families in Norway. Given the sensitive nature of the topic, emphasis was placed upon ethical considerations and the study was subject to ethical review in each of the three participating countries and by the funding organisation (supplementary file).

A range of methods and data was employed to examine and contextualise the (micro-level) experiences of children and parents within their local (meso-level) and national (macro-level) contexts. Secondary analysis was carried out by UK researchers of large-scale national and international datasets – the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (Eurostat Citation2017a), Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) (Currie et al. Citation2012) and the UK’s Living Costs and Food Survey (LCFS) (ONS Citation2017). In addition, researchers in each country drew on published data and research to write reports on the historical, economic, political and policy contexts, including school meals provision. At the level of localities, schools and services, the qualitative fieldworkers carried out observations in the two contrasting urban and non-urban study areas in each country, written up as fieldnotes. These were supplemented by desk-based research and informal interviews, for example, with school staff who assisted with recruitment. At the micro-level, we recruited children and families in two contrasting urban and non-urban study areas in each country, through schools and other organisations, and carried out qualitative fieldwork that included semi-structured interviews and in some cases, visual methods with both children and parents (see supplementary file).

In-depth interviews with parents and children were carried out by researchers in each country according to a standardised but flexible semi-structured schedule. Given the personal and potentially shaming nature of the topic, we sought to interview children and parents separately, though this did not always happen due to limitations of space and for other reasons. During interviews with parents, data were collected about income and outgoings, and short life histories were elicited. Interviews with both parents and children also gathered information about food and eating; we asked participants to recall the last school and non- school day, the foods and meals eaten on these days, and their typicality.Footnote6 Children and parents were also asked about their experiences of eating and being unable to eat with others inside and outside the home and their feelings about these. With some children, visual ‘vignettes’ (drawings) were used to prompt conversation about difficult topics, such as being left out of eating with friends because of lack of money, finding there was no food to eat at home, or queuing for food in a food bank. Most parents and young people also completed questionnaires in the course of the fieldwork visits. Adult questionnaires asked about ways of managing the procurement, preparation and distribution of food, and social expectations, for example, concerning hospitality and reciprocity and invitations to eat out. Children’s questionnaires included a ‘food habits module’, based on the one used in the HBSC study (Vereecken et al. Citation2005, Citation2015), and two questions, also based on that survey, about going to school or bed hungry owing to a lack of food at home. To complement the interview material, a subsample of households (10 in each country) participated in additional visits involving ‘kitchen tours’, in which mothers showed researchers the facilities and foods they had at home. Photo-elicitation was also carried out in in which the children were first invited to take photographs of food and eating in their everyday lives at home – and in some cases at school. These photos were discussed with the researchers at a later visit (O’Connell Citation2013).

The first stage of the analysis of the qualitative data involved researchers in the three countries writing case summaries for children and parents, according to a template, that drew together data from the different methods and researchers’ fieldnotes. Researchers in each country also wrote reports of the qualitative research, including tables describing the distribution of food insecurity among sample households. In the second phase of analysis, the first two authors carried out comparative analysis across cases along several themes, including ‘school meals’ (O’Connell and Brannen Citation2021; see further details in the supplementary file). To aid cross-national comparison, reported household food expenditure was converted to a proportion of the national food budget standard (FBS) for similar family types.Footnote7

Findings

School meals: a macro-level resource for children and parents

Portugal

In Portugal, national school health programmes date back to the early twentieth century. In 1936 under the Estado Novo (Salazar’s dictatorship), a period of high poverty rates, the Ministry for National Education took responsibility for school meals. Most families were food insecure; children contributed to domestic work, taking them away from school. In this context, school meals policy focused on alleviating the effects of poverty, on bringing children to school and educating them in accordance with the values of the regime (obedience, good manners, and discipline). With the end of the dictatorship, in the 1970s Portugal’s democratic government sought to promote the physical wellbeing and intellectual development of all children through school food policies (Truninger et al. Citation2013).

Neoliberalism in Portugal in the 1990s led to the introduction of private catering firms and the diversification of food choices, and the consumerism of the school meals regime (Truninger et al. Citation2015), as in other European countries (Oostindjer Citation2017). However, school meals policies focussed on tackling excess weight and obesity (Truninger et al. Citation2013). A central part of this remit included the seasonality of foods, regional food cultures (and the Mediterranean diet), commensality, environmental issues (e.g. fish from sustainable sources), reduced meat consumption and increases in plant-based diets (Truninger et al. Citation2013; Cardoso et al. Citation2019; Pereira and Cunha Citation2017). In line with the more ‘communal’ approach to eating in continental countries (Fischler Citation2015), all Portuguese schools are required to provide a standard menu which consists of: (1) a fresh vegetable soup (with potatoes, legumes or beans); (2) one meat, fish/seafood with pasta, rice or potatoes and legumes (optional) on alternate days; (3) one piece of brown bread; (4) one plate of vegetable salad (raw or cooked) (5) one dessert composed of raw seasonal fruit together with cooked or baked fruit without sugar or pudding, jelly, ice cream, yoghurt (twice a month maximum); (6) water is the only drink available (Lima Citation2018). The menu varies every week and is displayed to the school community. Salt has been reduced and replaced by aromatic herbs in the food. Some schools have in-house catering services (cooking facilities and staff to serve school meals), while others rely on meals prepared by external catering companies (Cardoso et al. Citation2019). Regardless, the Ministry of Education issues guidelines determining what foods (and how often) should be served in canteens and cafeterias and regularly conducts reviews and inspections.

Every school-aged child (age 6–18 years) in Portugal is entitled to a school lunch. Prices are set by the Services of School Social Action (Serviços de Ação Social Escolar, SASE) and subsidised according to family income level.Footnote8 The price of a school meal, unchanged for many years, is 1.46€ (if bought in advance or with a 0.30€ addition if paid on the day) (Despacho Citation8452-A, Citation2015, Diário da República, 31 July 2015). Some schools use their financial resources to provide a food supplement during the morning/afternoon breaks including bread (with butter, cheese or ham), sometimes accompanied by milk and fruit (the latter is provided under free fruit schemes such as the EU’s school fruit, vegetables and milk scheme).

The United Kingdom/England

The UK has a long and complex history of school meals provision, whilst school meals are currently a devolved matter, meaning there are different regulations and practices in the countries of the UK. Free school meals (FSMs) were first introduced in Britain in 1906, in response to a concern that young male volunteers in the Boer War were too small, undernourished or ill to fight (Gillard Citation2003). However, although Local Authorities had the right to provide meals to children in need, they were not required to do so. A National School Meals policy was only introduced in 1941 together with the first nutritional standards for school meals. Since then, school meals policy has been through significant change (Lang et al. Citation2009). As in Portugal, neoliberal ideas were influential, and nutrition policies that had been introduced after World War II were abolished in 1980 when the Thatcher government obliged Local Authorities to engage in competitive tendering and outsource school meals to the private sector.

School Food Standards were reintroduced in 2014 and today, in England, these comprise rules about the quality and quantity of food served across the school day. School vending machines have been abolished and more than two portions of deep-fried, battered or breaded food a week are not allowed. However, the Standards are not mandatory for all schools and there is a lack of monitoring and accountability for schools. Whilst research on the implementation of the Standards is patchy, some points to contradictions between the curriculum and the availability of nutritious food in schools (e.g. Jamie Oliver Foundation Citation2017). Coordinated by a coalition of UK charities, campaigners are currently calling for a government review of school food including mandatory monitoring of standards in England (School Food Matters Citation2022).

Eligibility for FSMs in England depends on a child’s age and family circumstances. Since 2014, state-funded schools have been required by law to provide FSMs to all children in Key Stage 1 (reception, year 1 and year 2, age 4–7 years) with the aim ‘to improve academic attainment and save families money’ (Dimbleby and Vincent Citation2013). For older children in state schools, FSM eligibility is linked to the parent (or the young person) receiving certain means-tested benefits. It is estimated that around a third of pupils living below the relative poverty line (living in households earning less than 60% of median income) are not eligible for FSMs because their parents are not on ‘out-of-work’ benefits (Royston et al. Citation2012). Working tax credits – paid to low-paid workers employed for at least 16 hours a week – are not an eligible benefit nor can FSMs be claimed by migrants who lack official papers because it comes from public funds.Footnote9

Norway

In Norway, the first school meal programme, launched in the 1880s, was designed to feed children in poverty (Lyngø Citation2001, 117). In the first decade of the twentieth century this was revised in light of ideas about scientific rationality, seeking not only to improve the nutrition of the population but to teach the lower strata about ‘proper hygiene’ (Lyngø Citation2003). Aimed at providing nutritious food to all school children by 1935, all schools in Oslo offered a school meal (Bjelland Citation2007), but many municipalities were too poor to offer them free. What then became known as the ‘Sigdal breakfast’, whereby pupils were expected to bring the ingredients with them to school, became widespread in 1963 and was rapidly transformed into the ‘Norwegian packed lunch’ (Døving Citation1999).

Only a minority of schools in Norway provide school lunch (Skuland Citation2019). Indeed, the packed lunch has become so well-established among the general Norwegian population that a lunchtime cold meal is considered ‘natural’ and eating something warm seen as fattening and unhealthy (Løes Citation2010). Even so, over the past two decades, the packed school lunch has increasingly been the focus of public and political debate. The Socialist Left party (SV) that governed the Ministry of Education and Research following the 2005 elections (that led to the Red-Green coalition government 2005–2013) emphasised the introduction of a free, complete school meal for all pupils in their election campaign, and estimated the costs to be about 250 million Euro (NOK 2 billion) per year (2.5 Euro per meal) (Løes Citation2010, 11). In the 2013 election, the Red-Green coalition government was replaced by a coalition government between the Conservatives and the Progress party. However, a majority of the population is generally supportive of the reintroduction of school meals, especially among low-income groups (Skuland and Roos Citation2020).

School meal guidelines have existed in Norway since the 1970s, but in 2015, renewed and comprehensive guidelines for the Norwegian school meal were introduced. These recognise schools’ potential to reduce dietary inequalities and point to the importance of school-based meal policies and collaboration with parents, given most food is brought from home. However, the guidelines apply only to primary and after school care, whereas the previous guidance includes all school types and ages, whilst monitoring is delegated to schools and teachers (Randby et al. Citation2021).

School meals: a meso-level resource for children and parents

This section describes our findings on the meso-level context of schools and charities and other formal services and resources locally available to low-income families and the distribution of secondary school age children in the sample according to whether they were in receipt of a free or subsidised school meal. Our fieldwork and desk-based research drawing on published materials suggest variation between and within the local contexts, with more variation in the UK communities and schools.

Portugal

Portuguese schools vary in whether school food is prepared on the premises or not. In addition, the length of the secondary school day varies over the school week for different pupils, with the result that, on days when the school day is shorter, some young people go home for lunch. Furthermore, the provision of snacks (usually a carton of milk, sandwich and fruit) by schools at breaktimes is discretionary and many children reported buying food from shops and cafes near school. Alongside schools, there is widespread charitable provision of food for families on low-incomes; this has been historically run by the Roman Catholic Church and is long established in local communities.

The United Kingdom

In the UK, school meals provision is more heterogeneous, reflecting in large part the differentiation of the UK’s education system with its significant independent (private) sector that has long ensured disproportionate access to elite universities and higher incomes. In addition, recent decades have seen increasing variation in the status of state secondary schools (academies, free schools, community schools) that entail different rules regarding food provision. This variation results in significant differences in the ways in which schools are funded: control of state schools has largely been taken away from Local Education Authorities and vested in business. Indeed, state schools are increasingly run as businesses in charge of their own budgets and how they are spent.

In the UK, schools with more resources can choose to cover meals for children who do not qualify for FSMs according to the criteria (that is, their parents are not in receipt of one of the ‘passported’ social security benefits that provides the basis of entitlement).

As in Portugal, some have kitchens and employ staff to prepare meals at lunchtime, whilst others outsource the service or buy pre-prepared food. The way that the food is offered to children varies, with some secondary schools providing a ‘communal’ or ‘family service’ in which no money exchanges hands; the same meal offered to all children and food brought from home or bought at shops at lunchtime is prohibited. However, reflecting the more ‘contractual’ mode of commensality characteristic of individualised Anglo-Saxon countries (Fischler Citation2015), most secondary schools operate a ‘cafeteria-style’ approach where children choose from the foods on offer and pay at the point of service.

In most secondary schools, children receiving FSMs get an ‘allowance’ to spend at the canteen, around £2.30 per day at the time of the study. In 2012 one in seven young people indicated that their FSM allowance did not allow them to purchase a full meal (Farthing Citation2012). Delivery systems were also found in some instances to be stigmatising.Footnote10 Payment and queuing systems and arrangements of eating spaces also varied, with some young people mentioning feeling excluded from the ‘normal’ lunchtime experience of ‘hanging out’ with friends (Farthing Citation2012) and others reporting saving lunch money or bringing in biscuits bought at local shops (O’Connell et al. Citation2019b).

Children whose migrant parents’ legal status meant they were subject to a no recourse to public funds (NRPF) clause were not entitled to FSMs. Whilst two schools used their discretionary budgets to ensure these children did not go without food at lunchtime, in the other schools these children went hungry.

The coverage of FSMs in Portugal and the UK samples points to sharp differences in relation to children’s eligibility. shows the distribution of secondary school-age children in the sample according to whether they were in receipt of a free or subsidised school meal. It shows that almost all of the children we interviewed in Portugal accessed a free or subsidised meal (42/46), compared to only half of those attending secondary school (23/46) in the UK.

Table 1. Free and subsidised school meals in the UK and Portugal.

The majority of children in the Portuguese sample (35/46) receive fully subsidised (free) school meals. Seven children (7/46) receive a 50% subsidy (they pay 0.73€ per meal) and four (4/46) are not entitled to a subsidy so pay the full price (1.46€); these children usually go home for lunch and, less often, eat in the school canteen or local cafes.Footnote11 In contrast, only half (23/46) of the children in the UK sample received a school meal. The main reason families were not in receipt of the social security benefits that would entitle their children to a FSM was that a parent was in paid employment; in four cases, the family’s irregular immigration status meant they had ‘no recourse to public funds’ i.e. no access to any benefits, including school meals (see O’Connell et al. Citation2019b; Dickson Citation2020).

Norway

In Norway, in contrast to Portugal and the UK, there is in general no school meal arrangement, and children typically bring packed lunch from home. Norwegian school children traditionally eat a cold bread meal during school hours (Hansen et al. Citation2015). Challenges with the traditional packed lunch are that some children bring an unhealthy lunch to school, while some do not bring lunch at all (Kainulainen et al. Citation2012).

Most of the young people in the Norway sample ate packed lunches on most days, but a few frequently purchased food at the nearby shop or the school canteen. Two young people went home to eat during the lunch break, whilst two always brought a packed lunch, but rarely ate it. There are few data on school canteen use in Norway, with the exception of Løes (Citation2010) who reports a large increase in upper secondary school pupils (16–19) accessing school canteens (from 7% in 1991 to 55% in 2000). However, our sample was mostly in lower secondary, about which little evidence of school meal provision exists.

In the current study, a few young people in Norway reported that their schools offered breakfast before school started, soup at the after-school homework sessions, a snack or a small hot meal. Many of the young people reported that they were permitted to leave the school area during the lunch break to buy food at nearby food outlets. Whilst some research suggests that buying food at the canteen – or outside of school – puts extra stress on low-income families (Harju and Thorød Citation2011) it may also be the case that families struggle to meet the cost of packed lunches, which may be just as – or more -expensive.

School meals: a micro-level resource for children and parents

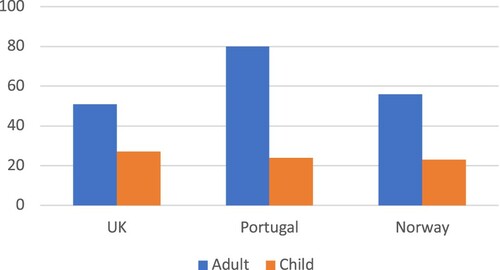

Across the qualitative sample, just under two-thirds (85/133) of households included an adult who was classified as experiencing severe food insecurity (skipping meals, going without enough to eat, or feeling hungry at times, due to a lack of resources)Footnote12 whilst just under a quarter (32/133) of families included a child classified as severely food insecure ().

Figure 1. Percentages of households in which a child or parent is in ‘severe food insecurity’ by country in the qualitative study (N=133).

In all three countries, the rate of severe food insecurity was much higher for parents than for children. This is likely to reflect that parental ‘altruism’ is a common way of managing food insecurity in families (Whitehead Citation1981). This phenomenon is gendered, with ‘maternal sacrifice’ reflected in data concerning relatively higher (and increasing) rates of food insecurity among women than men (e.g. FAO et al. Citation2021). However, the variation between countries suggests there are also other factors at play. Whilst the proportion of parents who were classified as severely food insecure was higher in Portugal than in the UK or Norway, the proportion of children classified as severely food insecure was fairly evenly distributed across the three countries, with twelve cases (12/45) in the UK and 10 cases each in Portugal (10/45) and Norway (10/43). Relative to adults, then, children in the sample in Portugal were better protected from food insecurity than their counterparts in the UK and Norway. Whilst these qualitative data should not be generalised, the pattern reflects that found in the secondary analysis of the FAO survey, above (Pereira et al. Citation2017), suggesting families with children fare relatively better – have lower rates of ‘severe food insecurity’ – in Portugal compared to the UK or Norway. The relatively lower rates of severe food insecurity among children in Portugal may indicate the potentially protective nature of Portuguese school meals.

To examine how the organisation of school food provision at the macro- and meso- levels plays out in the everyday lives of children and families in low-income families, we have selected for comparison three cases of families headed by a non-employed lone mother in each country.Footnote13 As noted above, this family type constitutes the lowest income group across Europe (Bradshaw and Chzhen Citation2011) and is most likely to experience household food insecurity (Brannen and O’Connell Citation2022). All three families live in the capital city of each country. However, the families differ in some respects, notably the number of children and their migration history.

Free school meals in Lisbon: Aleixa

Alexia, aged 14, a Portuguese girl, lives in a North Lisbon neighbourhood with her mother, Cheila, twin sister, six-year-old brother and three-year-old twin sisters. Cheila, a lone parent, has been unemployed since her six-year-old son was born, apart from some very part-time jobs that are unofficial and sporadic. The monthly household income is 622€, made up of 447€ (Social Insertion Income) + 175€ (child allowance, 5 × 35€). In addition, Cheila earns 20€ a week for cleaning/cooking jobs she does in private homes. Currently, Cheila is receiving a lower benefit because she is repaying Social Security overpayments. She also owes 600€ in rent, which she is paying back in instalments. The costs of rent, utilities, TV, internet, phones and transport add up to around 475€.

The money Cheila has left to spend on food – 50–60€ per month – is around one-tenth of the FBS for a family of this type. Food is consequently in short supply and Chelia has been reliant on two food aid organisations for the two months before interview. She receives a weekly food basket from the church and ready-prepared meals from a food aid organisation (Re-Food), normally soup and a main course, ‘at this moment, not only because I want, but because I can’t, I only buy meat about once a week. The rest we get from the food bank’. Two of her neighbours, who also receive a weekly basket from the food bank, also share food with the family. Cheila questions the quality of the free food saying much of the time it is unfit for consumption. The fact that her three- year-old twins still breastfeed is a relief, despite it being physically draining, ‘even when there is nothing for dinner, I rest assured, because I know they can breast feed all night. Although that bothers me and doesn’t let me rest’. If Cheila could change anything about her family’s diet, she would like to provide more vegetables for her children, but ‘it’s something I think is strange, that it never comes with the food bank’.

In this context, free school meals are vital, contributing to nutritional intake and are a means of children’s inclusion or belonging at school. Alexia and her twin qualify for a free lunch that consists of three courses (see ). In her interview, Alexia says she doesn’t consider there is any difference between students who pay and don’t pay. Although Alexia says she prefers her mother’s cooking, she also says that school meals are ‘quite good’ and better than at her previous school. Revealing something of the adequacy of food at school, compared to home, in response to a question about what is the most important meal of the day, Alexia says that for her this is lunch, ‘I say what I learned in school: it’s breakfast; but for me it’s really lunch (…) Because I feel a greater need to eat at lunchtime than in the morning’.

Cheila says that, whilst the children sometimes complain about the quality of school meals, she insists they eat them,

I ask them to have lunch, because I don’t know if I’ll have dinner [to give them] … (…) I ask them to eat, because sometimes I don’t know what will come … and sometimes they have to eat toast for dinner and … bread. Drink chocolate milk and such … I mean … and I’m more relaxed if they’ve had a meal already.

Cheila asks the nuns at the school to supply her daughters with snacks, ‘they give something more. They give them soup at the afternoon and then … I don’t worry as much’. In the summer holidays, Alexia attends summer camps, where lunch is provided.

Free school meals in London: Maddy

Maddy, age 16, a white British girl, lives in an inner London borough with her grandmother, Mary, who has brought her up. Mary lost her job as a part-time cleaner and is reliant on Employment Support Allowance (disability benefit) and Child Tax Credit that add up to £520 per month and Child Benefit (£80 per month). Maddy worries about lack of money. The money Mary spends on food – about £30 a week – is around half the FBS for a family of this type and sometimes much less; Mary finds it hard to do any food shopping some weeks, as she has only ‘a tenner’ (£10).

While Mary is aware of recommendations for a healthy diet, she buys what she calls ‘cheap food’ in order to manage. She thinks that her granddaughter eats a lot of ‘junk food’ because ‘that’s all we can afford’. She buys little fruit as it is perishable. Mary also says she tries to cook one ‘decent meal’ a week, usually a Sunday ‘roast’ with meat, potatoes and vegetables.

Maddy receives free school meals. Her school adopts a cafeteria-style approach, in which children select from hot and cold foods at a counter and pay at the till. According to Maddy the food ‘isn’t great at our school, it’s terrible’. Maddy says her allowance is £2.20 per day. Although the school uses a cashless system designed not to identify those on free school meals, those in receipt of free meals are restricted to particular items on account of price. Describing what happened when she selected a large baguette, because she was hungry, Maddy finds the experience profoundly humiliating:

So, when she [lunchtime staff at the checkout] was like, “You can’t get that, you’re free school meals”, like I was really embarrassed cos people were waiting behind me, I was kind of like “Oh my God”. And I was like, ‘But I’ve technically got £2 on my account’, she was like, ‘No you can’t get that at free school meals’. And it’s like you’re really restricted to what you can eat with free school meals. […] So that really like got me, so now I just get what I know I’m safe with … so a small baguette and carton of juice.

Maddy’s grandmother provides £2 as a daily ‘top up’ to the FSM allowance, an amount she can ill afford. Given her lack of access to other money, Maddy often saves this to go out with friends, for example, to buy something to eat or go to the cinema.

Despite FSMs being suboptimal, they demonstrate the relative hardship of families during school holidays: it is at these times that Mary eats less to save money, both to cover extra meals but also to treat Maddy who wants to join friends in holiday activities. ‘She wants money to go out “Cos I want to get an ice cream, all my mates have got one” and wee-wee-wee-wee’ … “Can’t I go swimming?” cos … you know … there’s always something’. Maddy also has her friends home more often. However, given this additional cost, Mary has to ask them to bring some food with them, ‘Yeah because she’s always got friends here as well and “Can they stay?” – “Well I’ve got to feed them haven’t I, Maddy, now” you know. I’ll get some bits, and I’ll make sure they bring some bits with them’. Even so, Mary feels the pressure of having to provide a meal and says she manages to ‘find something’.

Packed lunch in Oslo: Murad

Murad aged 14, a migrant from the Balkans, lives with his lone mother, Amina, a widow, and two siblings in Eastern Oslo. The family came to Norway ten years ago after the children’s father was killed in the war. Amina is not able to work because of a hand injury. She relies on state benefits (currently 7000 NOK per month); she thinks that the family has been deprived of the benefit to which they are entitled. The cost of their private housing is paid by the social security office. However, the private landlord has served notice to vacate their very small apartment and the family is on a waiting list for public housing.

Amina’s food budget varies depending on what she has left at the end of the month. Sharing food with family and friends is very important in her culture, ‘it is what makes us happy’. She relies on the Poor House, a charity in Oslo that distributes food and other goods to the needy, for much of their food, but does not like the way the volunteers control the food supply and the way recipients are treated. Her friend translated,

there’s so much food on display there, but somehow they don’t give [it] out … […] You see a lot, and they give just one milk, and you don’t eat pork, you go past it, right, and you go to the fruit, maybe you get some or not. In a way, they don’t treat you in a good way.

Because the Poor House does not supply halal meat, Amina travels to Sweden, where it is cheaper, to purchase it.

Given that in Norway children are normally expected to take a packed lunch, providing school food can be expensive, especially for large families. As noted above, the cost of food, including bread, is relatively high in Norway. However, unless he is very hungry, Murad says he rarely eats the sandwiches that he takes to school because they are ‘boring’ and are not like the ‘fancy stuff’ that his friends bring. Murad is conversant with concepts around a healthy diet and says he is unable to afford healthy food that he sees his friends eating. At school and outside of school, Murad is excluded from food-related social participation; he rarely has any money to spend with his friends and does not invite his friends home to eat. He was clearly aware of the family’s poor financial situation, and how his consumption practices – not only of food, but also of clothing – marked him out as different, saying for example that his mother could not afford to buy him the same type of clothes as those his friends wear (Borch et al. Citation2019).

While each of these cases is unique, nonetheless they are instructive at the micro-level in terms of highlighting the importance of school meals to children in terms of their diets and integration into school life, as well as the contribution they do or do not make to low-income parents’ efforts to feed their families on inadequate budgets.

Discussion and conclusion

Drawing on a mixed methods study of food in low-income families in three European countries, this paper has adopted a realist ontological stance and an embedded case study approach. It has aimed to examine the extent to which school meals are a resource for low-income families living in different contexts. Whilst previous research has examined the impacts of school meals on the diets of children within different countries, none to our knowledge has adopted a multi-level approach to examine the difference school meals make to children and families’ food practices in a comparative perspective. Reflecting some quantitative international evidence, we found that the children in our qualitative sample in Portugal were relatively better protected from food insecurity than were children in the UK or Norway. Moreover, we found that Portuguese school meals are likely to be part of the explanation.

At the macro-level, we showed how Portugal’s national school meals policy provided not only greater uniformity of access between children but also higher quality food, especially compared with the UK with its high eligibility threshold to FSMs and an allowance that does not permit access to sufficient high-quality food given weakly regulated standards. At the meso-level (between schools), we have pointed to the relevance of school meals policies and delivery systems in affecting children’s access to school meals, with the schools in the UK areas varying in their practices of funding those in greatest need and in the delivery of school meals.

At the micro-level, we have illustrated through three cases how school meals are a resource (or not) for children and their parents in low-income families, including how they mitigate or intensify the lack of household resources and how children experience school meals. There were differences in the adequacy of food children were able to access at school, and their experiences of mealtimes. Although Alexia preferred her mother’s cooking, she admitted lunch was the most important meal of the day; as Chelia said, school meals can be a lifeline for food insecure families: ‘I ask them to have lunch, because I don’t know if [they]’ll have dinner’. In contrast, Maddy said the money available did not allow her to buy sufficient food to fill her up and her grandmother provided extra money she could ill afford. Moreover, Maddy described being stigmatised and feeling shamed for being in receipt of FSMs, something Alexia did not recognise in the context of a communal meal. Like his classmates in Oslo, Murad had to take his own food to school. However, given his mother’s reliance on cheap food and the Poor House, it did not match up to the same standards, and he rarely had money to spend on food inside or outside of school, contributing to his sense of social exclusion. Outside of term time, whilst Alexia attended holiday provision that provided meals, for Maddy’s grandmother, school holidays were expensive; to manage she had to cut back on her own food intake. In the Norwegian context, the burden of packed lunches reflects the high costs of customary Norwegian food practices and pressures to conform to these, which may be lessened when eating at home in school holidays food that is often part of customary ethnic cuisines (Skuland Citation2019).

One limitation of the research design for addressing the questions examined in the paper is that it did not set out to investigate the ways schools organise meals. Rather, as noted, school meals or lack thereof emerged as an important potential resource for families living on low incomes. Had the study set out to focus only on the role school meals play in the lives of children in low-income families, it might usefully have selected children within particular schools, rather than particular areas. Such a study would need to identify schools according to a theoretical sampling frame informed by information regarding the different types of educational, funding and food provision in each country. Future research on the topic might usefully set out to do this, in order to situate findings about school meals provision more fully in relation to their wider national contexts. On the other hand, the focus on children and families provides a unique contribution to the literature, and a sound basis for exploring further the findings in future research. A further priority for research and policy might also be to examine, comparatively, the school food standards in place and whether or not they work as they are intended, both in relation to the healthiness of the food on offer, and also with respect to whether or not systems of delivery protect, respect and fulfil children’s dignified access to food in school.

As noted above, the ICESCR, includes the right to food that is not only nutritious, but also culturally appropriate, in dignified ways. According to the FAO (Citation2008) food security is underpinned by four ‘pillars’ or dimensions, namely availability, access, utilisation and stability. For food security to be realised, all four of these dimensions must be fulfilled simultaneously. Overall, our analysis demonstrates that school meals can help mitigate the effects of poverty on children’s diets and lives and contribute to children’s food security. However, whilst the availability of school meals is a necessary condition, in itself it is insufficient to mitigate food insecurity. Rather, it is clear that access to such food is determined by having sufficient income to purchase meals, or eligibility for free meals, whilst the degree to which school meals may be utilised to satisfy material and social needs depends on the quality of food available and the systems of delivery. In addition, the limited stability of school meals reduces the contribution they make to addressing families’ food security, given school holidays are more expensive (though this situation is reversed in Norway), supporting the contention that school meals may mitigate food insecurity, but cannot solve it. Households must have the resources to feed themselves, and children should also have the right to be fed at school, just as they have the right to education. Hence resources need to be provided both at the household and collective levels (Veit-Wilson Citation2019).

Making healthy and inclusive school meals available according to national policies is a necessary but insufficient condition for securing children’s food security. Guaranteeing access to school meals requires extending eligibility to all children whose families are on low-incomes; ensuring none are stigmatised requires making provision universal. Whilst the UK, Portugal and Norway have all ratified the ICESCR, there is little evidence of the incorporation of its principles into domestic lawFootnote14 (O’Connell and Brannen Citation2021). The right to food is not mentioned in official school food policies of England, Portugal or Norway, although within the devolved UK, some progress is being made in Scotland (Shields Citation2021). Based on the results of this paper, showing that publicly funded, nutritious school meals can protect children from the direct effects of poverty on their food security, whilst poorly funded and weakly regulated school food provision compounds children’s experiences of disadvantage and exclusion, we argue that dignified access to nutritious meals at school should, like health and education, be an inalienable right of all children.

REUS-2021-0141-File004.docx

Download MS Word (50.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the children and families who participated in the study and to thank and acknowledge the co-researchers with whom we carried out the research on which the article is based. The team included: in the UK, Laura Hamilton, Abigail Knight, Charlie Owen, Antonia Simon (Thomas Coram Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education); in Portugal, Manuel Abrantes, Fabio Augusto, Sonia Cardoso and Karin Wall (Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa); in Norway, Anine Frisland (Consumption Research Norway, Oslo Metropolitan University). We would also like to thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive comments that have helped us to strengthen the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rebecca O’Connell

Rebecca O’Connell is Reader in the Sociology of Food and Families at the Thomas Coram Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education.

Julia Brannen

Julia Brannen is Emerita Professor of the Sociology of the Family at the Thomas Coram Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, and a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences.

Vasco Ramos

Vasco Ramos is a Research Fellow at Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa.

Silje Skuland

Silje Skuland is Head Of Research at the Consumer Research Institute (SIFO), Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway.

Monica Truninger

Monica Truninger is a Research Fellow at Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa.

Notes

1 Voices of the Hungry uses a measure of food insecurity, the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), which is derived from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) and the Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale (Ballard et al. Citation2013).

2 The sample sizes for these calculations are as follows: NO: 1995; PT:2016; UK: 1992.

3 The findings for Portugal need to be treated with caution since lone parent families living in multigenerational households are excluded from this analysis (see O’Connell and Brannen Citation2021).

4 In other words, lone parent families in income poverty are more likely to be a long way below the <60% median income threshold.

5 Low income was defined subjectively as an income below what the family needed. Most household incomes of the recruited families corresponded with the relative low-income measure that is widely employed as a poverty threshold in Europe, i.e. below 60 per cent of the national median (O’Connell and Brannen Citation2021, 57–8).

6 This approach to gathering data about food and eating may help avoid - though not completely overcome - difficulties with dietary recall and constraints of socially desirable responses (O’Connell and Brannen Citation2016; see supplementary file).

7 This method of comparing reported expenditure with the FBS gives a rough idea of how the spending of a family compares with the spending deemed necessary to meet not only health recommendations, but also norms about what is customary, in the society to which they belong (Padley and Hirsch Citation2017).

8 A, B and C: bracket A is fully subsidised; bracket B is 50 per cent subsidised; bracket C is full price.

9 In the context of pressure placed on government by organisations supporting such families in Coivid-19, eligibility has been temporarily extended to some families with No Recourse to Public Funds

10 In Wales and Scotland, legislation requires that children cannot be identified by anyone other than an authorised person ‘as a pupil who receives a school lunch free of charge’. However, no such legislation exists in England, where our sample lived.

11 There were four cases in Portugal in which children were not entitled to a free or subsidised meal. Two were ineligible due to the family income being too high (so they were SASE C); one had not submitted income tax return on time to be assessed; a fourth was a recent migrant whose family had not yet applied.

12 Our analysis of the qualitative data included examining the distribution of food poverty across the sample. To do this, we applied our multidimensional conceptualisation of food poverty to code children’s and adults’ food insecurity according to their experiences on three different dimensions: ‘quantitative’ (eating less than they would like, skipping meals, going without enough to eat, feeling hungry); ‘qualitative’ (eating foods that were filling rather than nutritious, going without fruit, vegetables protein); and ‘social’ (eating foods that were not customary, being unable to participate in customary activities), in the past year, due to being unable to afford them. All the parents, and most of the children, experienced some aspect of food insecurity, defined in this way. Most of those reporting an absolute shortage of food (quantitative dimension) were experiencing other aspects of food insecurity too. In examining the distribution here, we have chosen to focus on the ‘quantitative’ dimension only, as it is the most stringent measure, and it also closely corresponds with ‘severe’ food insecurity as defined in the FIES introduced in the Background (reducing quantities, skipping meals and experiencing hunger in the past year) and with which we compare our findings, in the section on school meals as a micro-level resource.

13 We have made the selections on the basis of their typicality in relation to the dimensions we are considering, in this case non employed lone mothers. However, they are not matched on whether they participated in the visual methods; whilst one family did (and a photograph by the child is included) the other two families were not in the subsample who participated in the visual methods.

14 In Portugal, a legislative initiative to enshrine the Right to Adequate to Food in national law was started in 2018. The National Council of Food Security was created, involving a host of institutional stakeholders, which developed The National Strategy for Nutritional and Food Security approved by the Council of Ministers on September 2021 (Resolution n° 132/2021 of 13th September). However, its role and activities remain ill-defined.

References

- Andersen, S., Baarts, C. and Holm, L. (2017) ‘Contrasting approaches to food education and school meals', Food, Culture & Society 20(4): 609–629.

- Ballard, T., Kepple, A. and Cafiero, C. (2013) The Food Insecurity Experience Scale: Development of a Global Standard for Monitoring Hunger Worldwide, Rome: FAO.

- Bambra, C., Lynch, J. and Smith, K. E. (2021) The Unequal Pandemic: COVID-19 and Health Inequalities, Bristol: Policy Press.

- Bergene, A. (2007) ‘Towards a critical realist comparative methodology', Journal of Critical Realism 6(1): 5–27.

- Bhattacharya, J., Currie, J. and Haider, S. J. (2006) ‘Breakfast of champions? The school breakfast program and the nutrition of children and families', The Journal of Human Resources 41(3): 445–466.

- Bizarro, S. and Ferreiro, M. D. F. (2021) O impacto da crise pandémica de Covid-19 (Coronavírus) no sistema alimentar português: estudo exploratório dos media e imprensa. DINÂMIA'CET, Working Paper 2021.02.

- Bjelland, I. (2007) ‘Ren i skinn er ren i sinn – skolefolk og medisineres ordskifte om norske skolebarns helse 1920– 1957’, master’s thesis, University of Bergen. https://bora.uib.no/bitstream/1956/2364/1/Masterthesis_Bjelland.pdf.

- Borch, A., Harsløf, I., Klepp, I. and Laitala, K. (2019). Inclusive Consumption: Immigrants’ Access to and Use of Public and Private Goods and Services. Open Access, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Bradshaw, J. and Chzhen, Y. (2011) ‘Lone-parent families: poverty and policy in comparative perspective’, in A. Samaranch and D. Nella (eds.), Bienestar, Protección Social y Monoparentalidad, Barcelona: Copalqui Editorial, pp. 25–46.

- Brannen, J. (2019) Social Research Matters: A Life in Family Sociology, Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Brannen, J. and O’Connell, R. (2022) ‘Experiences of food poverty among undocumented parents with children in three European countries: a multi-level research strategy', Humanities & Social Sciences Communications 9(42): 1–9, doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01053-3.

- Capar, R. (2021) ‘Norway’s new government plans to introduce one healthy free meal a day in schools’. Norway Today, https://norwaytoday.info/news/norways-new-government-plans-to-introduce-one-healthy-free-meal-a-day-in-schools/.

- Cardoso, S., Truninger, M., Ramos, V. and Augusto, F. (2019) ‘School meals and food poverty: children’s views, parents’ perspectives and the role of School', Children & Society 33(6): 572–586.

- Chzhen, Y. (2014) Child Poverty and Material Deprivation in the European Union During the Great Recession., Innocenti Working Papers, No. 2014/06, UN, New York. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18356/899c7c48-en.

- Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O. R. F. and Barnekow, V. (2012) Social Determinants of Health and Well-Being among Young People. Health Behaviour in School- Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International report from the 2009/ 2010 Survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0003/163857/Social-determinants-of-health-and-well-being-among-youngpeoplepdf?ua=1.

- Daniel, P. and Gustafsson, U. (2010) ‘School lunches: children’s services or children’s spaces?', Children’s Geographies 8: 265–274.

- Davis, O. and Geiger, B. (2017) ‘Did food insecurity rise across Europe after the 2008 crisis? An analysis across welfare regimes', Social Policy and Society 16(3): 343–60.

- Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) (2020) ‘Family food 2017/ 18’. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/family-food-201718/family-food-201718#household-spending-on-food.

- Despacho no. 8452- A (2015) ‘The price of a school meal is 1.46€’, Di rio da Rep blica, n. 148/ 2015, 2 Suplemento, S rie II de 2015- 07- 31, 31 July.

- Dickson, E. (2020) ‘(No) recourse to lunch: a frontline view of free school meals and immigration control during the COVID-19 pandemic', Families, Relationships and Societies 00(00): 1–4.

- Dimbleby, H. and Vincent, J. (2013) The School Food Plan, London: Department for Education.

- Døving, R. (1999) ‘Matpakka – den store norske fortellingen om familien og nasjonen’, Tidsskrift for religion og kultur 1, http://www.hf.ntnu.no/din/doving.html.

- Dowler, E. and O’Connor, D. (2012) ‘Rights-based approaches to addressing food poverty and food insecurity in Ireland and UK', Social Science & Medicine 74: 44–51.

- Dowler, E., Turner, S. and Dobson, B. (2001) Poverty Bites: Food, Health and Poor Families, London: Child Poverty Action Group.

- Earl, L. and Lalli, G. (2020) ‘Healthy meals, better learners? debating the focus of school food policy in England', British Journal of Sociology of Education 41(4): 476–489.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Eurostat (2017a) ‘EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU- SILC) methodology’, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=EU_statistics_on_income_and_living_conditions_(EU-SILC)_methodology.

- Eurostat (2017b) Income poverty statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Income_poverty_statistics&oldid=440992.

- Eurostat (2017c) People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by age and sex, http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do.

- Eurostat (2019) ‘Consumer price levels in the European Union, 2018’, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/de/news/themes-in-the-spotlight/price-levels-2018.

- FAO (2008) An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security. EC-FAO Food Security Programme, http://www.fao.org/3/al936e/al936e.pdf.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation) (2016) Voices of the Hungry: Methods for Estimating Comparable Prevalence Rates of Food Insecurity Experienced by Adults throughout the World. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4830e.pdf.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation) (2021) School Food and Nutrition: School food for supporting children’s right to food, https://www.fao.org/school-food/news/detail-events/en/c/1412901/.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation), IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2018) The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation), IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2021) The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for all, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- Farthing, R. (2012) Going Hungry? Young People’s Experiences of Free School Meals, London: Child Poverty Action Group and British Youth Council.

- Fischler (1988) ‘Food, self and identity', Social Science Information 27(2): 275–292.

- Fischler, C. (2015) ‘introduction', in C. Fischler (ed.), Selective Eating: The Rise, Meaning and Sense of Personal Dietary Requirements, Paris: Odile Jacob. pp 1–15.

- Gillard, D. (2003) Food for Thought: Child Nutrition, the School Dinner and the Food Industry, http://www.educationengland.org.uk/articles/22food.html.

- Grignon, C. (2001) ‘commensality and social morphology: An essay of typology', in P. Scholliers (ed.), Food, Drink and Identity: Cooking, Eating and Drinking in Europe Since the Middle Ages, Oxford: Berg. pp. 23–35.

- Gustafsson, U. (2002) ‘School meals policy: The problem with governing children', Social Policy & Administration 36(6): 685–97.

- Hansen, L., Myhre, J., Johansen, A., Paulsen, M. and Andersen, L. (2015) UNGKOST 3 Landsomfattende kostholdsundersøkelse blant elever i 4. og 8. klasse i Norge. Oslo; 2015.

- Harju, A. and Thorød, A. B. (2011) ‘Child poverty in a Scandinavian welfare context – from children’s point of view', Child Indicators Research 4(2): 283–299.

- Holford, A. and Rabe, B. (2020) Policy Briefing Note: Impact of the Universal Infant Free School Meal Policy. Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/27/uk-children-england-going-hungry-schools-shut.

- Hood, A. and Waters, T. (2017) Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2016– 17 to 2021–22, London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- HRW (Human Rights Watch) (2020) ‘UK: Children in England Going Hungry with Schools Shut. Uneven UK Approach for Covid-19 Doesn’t Guarantee Children’s Right to Food’. 27 May, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/27/uk-children-england-going-hungry-schools-shut.

- Huang, J. and Barnidge, E. (2016) ‘Low-income Children's participation in the National School Lunch Program and household food insufficiency', Social Science & Medicine 150: 8–14.

- James, A. (1979) ‘Confections, concoctions and conceptions', Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 10: 83–95.

- Jamie Oliver Foundation (2017) A Report of the Food Education Learning Landscape, London: AKO Foundation.

- Kainulainen, K., Benn, J., Fjellström, C. and Palojoki, P. (2012) ‘Nordic adolescents’ school lunch patterns and their suggestions for making healthy choices at school easier', Appetite 59(1): 53–62.

- Lambie-Mumford, H. and Silvasti, T. (2020) The Rise of Food Charity in Europe, Bristol: Policy Press.

- Lang, T., Barling, D. and Caraher, M. (2009) Food Policy: Integrating Health, Environment and Society, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lima, R. (2018) Orientações sobre ementas e refeitorios escolares, Lisbon: Ministerio da Educacao, Direccao- Geralda Educacao.

- Løes, A. (2010) ‘Organic and conventional public food procurement for youth’, NorwayBioforsk Report 5 (110): iPOPY discussion paper 7.

- Loopstra, R., Reeves, A., McKee, M. and Stuckler, D. (2016) ‘‘Food insecurity and social protection in Europe: Quasi- natural experiment of Europe’s great recessions 2004– 2012’', Preventive Medicine 89: 44–50.

- Lundborg, P., Rooth, D.-O. and Alex-Petersen, J. (2021) ‘Long-term effects of childhood nutrition: evidence from a school lunch Reform', The Review of Economic Studies 89 (2): 876–908.

- Lyngø, I. (2001) ‘‘The national nutrition exhibition: A new nutritional narrative’, in Norway in the 1930s', in P. Scholliers (ed.), Food, Drink and Identity: Cooking, Eating and Drinking in Europe Since the Middle Ages, Oxford: Berg. pp 141–63

- Lyngø, I. (2003) ‘Vitaminer! Kultur og vitenskap i mellomkrigstidens kostholdspropaganda’, PhD dissertation, University of Oslo.

- Mikkelsen, B. E., Rasmussen, V. and Young, I. (2005) ‘The role of school food service in promoting healthy eating at school – a perspective from an Ad Hoc group on nutrition in schools', Foodservice Technology 5: 7–15.

- Morgan, K. (2006) ‘School food and the public domain: the politics of the public plate', The Political Quarterley 77(3): 379–387.

- Morrison, M. (1995) ‘Researching food consumers in school. recipes for concern', Educational Studies 21(2): 239–263.

- O’Connell, R. (2013) ‘The use of visual methods with children in a mixed methods study of family food practices', International Journal of Social Research Methodology 16(1): 31–46.

- O’Connell, R. E., Owen, C., Padley, M., Simon, A. and Brannen, J. (2019a) ‘Which types of family are at risk of food poverty in the UK? A relative deprivation approach', Social Policy and Society 18(1): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746418000015.

- O’Connell, R. and Brannen, J. (2016) Food, Families and Work, London: Bloomsbury.

- O’Connell, R. and Brannen, J. (2020) What food-insecure children want you to know about hunger. The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/.

- O’Connell, R. and Brannen, J. (2021) Families and Food in Hard Times: European Comparative Research, London: UCL Press.

- O’Connell, R., Knight, A. and Brannen, J. (2019b) Living Hand to Mouth: Children and Food in low-Income Families, London: Child Poverty Action Group.

- ONS (Office for National Statistics) (2017) Living Costs and Food Survey: User Guidance and Technical Information for the Living Costs and Food Survey. Office for National Statistics, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/methodologies/livingcostsandfoodsurvey.

- Oostindjer, M., et al. (2017) ‘Are school meals a viable and sustainable tool to improve the healthiness and sustainability of childreńs diet and food consumption? A cross-national comparative perspective', Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 57(18): 3942–3958.

- Osowski, C. P. and Sydner, Y. M. (2019) ‘traditional or cultural relativist school meals?: The construction of religiously sanctioned school meals on social media', in Gustafsson et al. (ed.), What is Food? Researching a Topic with Many Meanings, London: Routledge. pp. 72–87

- Padley, M. and Hirsch, D. (2017) A Minimum Income Standard for the UK, York: JRF.

- Pereira, A. L., Handa, S. and Holmqvist, G. (2017) ‘Prevalence and Correlates of Food Insecurity Among Children Across the Globe’, Innocenti Working Paper 2017- 09, UNICEF Office of Research: Florence.

- Pereira, F. and Cunha, P. (2017) Referencial de Educação Para a Saúde, Lisbon: Ministério da Educacao – Direção-Geral da Educação, Direção- Geral da Saúde.

- Poppendieck, J. (2010) Free for all: Fixing School Food in America, California: University of California Press.

- Porpora, D. (2015) Reconstructing Sociology: The Critical Realist Approach, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Portes, J. and Aubergine Analysis and King’s College London (2018) The Cumulative Impact of Tax and Welfare Reforms, Manchester: Equality and Human Rights Commission.

- Punch, S., McIntosh, I. and Emond, R. (2010) ‘Children's food practices in families and institutions', Children's Geographies 8(3): 227–232.