?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Utilizing the German residential allocation and residency obligation policies, which can be regarded as a natural experiment, we investigate the causal effect of the local supply of language courses on refugees' labor market integration. By restricting refugees’ initial and post-arrival regional mobility, these policies allow us to circumvent the potential problems of initial and post-arrival residential selection. Moreover, we examine the intermediary outcomes – language proficiency, language course completion and certification, and contacts with natives – through which the local opportunity structure of language courses shape refugees’ economic integration. Our results reveal that the local supply of language courses positively affects refugees’ employment probability, and this effect persists over the duration of stay. We further find that greater supply of language courses in the assigned county increases probability of learning the German language, completing the course and receiving language certificates. From a policy perspective, our findings imply that the local provision of language courses should be considered in refugees’ residential allocation to facilitate immigrants' integration. This is because limited access to such courses can delay host country language learning, language certificate obtainment, and labor market entry, thus slowing the integration of recently arrived immigrants.

Introduction

In most European countries, refugeesFootnote1 face labor market disadvantages. On average, they are less likely to be employed, and when employed, they often occupy part-time jobs in low-skilled and low-paid sectors (e.g. Dustmann et al. Citation2017; Kanas and Steinmetz Citation2021). Although refugees’ economic disadvantage decreases over time, it takes them more than 25 years to achieve parity with natives (Dustmann et al. Citation2017). To facilitate the economic integration of refugee populations, European governments have established a range of policy tools, most notably mandatory language courses aiming to promote their labor market entry. These language courses are often accompanied by integration courses and civic education, with the primary goal of facilitating employment access (Goodman and Wright Citation2015). However, although the first mandatory language courses were introduced in the 1990s, there is a lack of systematic evidence regarding the impact of these courses. This is especially the case for the two following issues.

First, it is not clear-cut whether there is a causal effect of mandatory language courses on immigrants’ labor market outcomes. On the one hand, the positive correlation between immigrants’ language proficiency and their economic performance – such as employment chances, earnings, and occupational status – is well established (e.g. Chiswick and Miller Citation1995; Dustmann and Fabbri Citation2003). This positive relationship has also been demonstrated for refugees (De Vroome and van Tubergen Citation2010; Dumont et al. Citation2016). Given that language course completion considerably improves immigrants’ language proficiency (e.g. Hoehne and Michalowski Citation2016; Kosyakova et al. Citation2022), policies supporting the supply of language courses should enhance immigrants’ economic outcomes. On the other hand, a part of this positive relationship between language courses and immigrants’ labor market outcomes is likely to arise due to immigrants’ sorting. In particular, if those with higher abilities or motivation to learn a language are more likely to complete language courses, the estimated positive effect of language course completion may be overestimated. However, as a basis for the policy discussion surrounding language supporting policies, hard evidence about mandatory language courses’ causal impact is necessary.

Second, there is little empirical evidence of how mandatory language courses influence immigrants’ economic outcomes. According to human capital theory (Becker Citation1964), mandatory language courses facilitate immigrants’ productivity via increased language skills, thereby promoting their employment chances. Signaling theory (Spence Citation1973) and social closure theory (Collins Citation1979) suggest that immigrants benefit from mandatory language courses because they signal their productivity and provide opportunities to acquire formal certificates (Fossati and Liechti Citation2020; Lochmann et al. Citation2019). Finally, social capital theory predicts that mandatory language courses may promote immigrants’ labor market success by facilitating contact with natives (Hoehne and Michalowski Citation2016; Schuller et al. Citation2011).

Against this background, this article contributes to previous research by studying the causal effect of the local supply of mandatory language courses on immigrants’ employment and other integration outcomes, such as language skills, course completion and certification, as well as contacts with natives. We exploit a unique natural experiment regarding two policies adopted in Germany: (a) the initial allocation policy of recently arrived refugees (Erstverteilung der Asylsuchenden, EASY) and (b) the residential obligation policy (Wohnsitzauflage). Upon arrival, refugees are exogenously assigned to German counties under the initial allocation policy, conditional on local economic strength and population size. Introduced in August 2016, the residential obligation policy further restricts refugees’ residential mobility. The two policies enable us to control for immigrants’ initial and post-arrival sorting into counties with different supplies of mandatory language courses and, therefore, to draw causal inferences about language-supporting policies. By considering integration course supply in the assigned county, we implement the so-called ‘intention-to-treat’ design (Gupta Citation2011).

Our study is closely related to the literature that has examined the effect of initial structural conditions on immigrants’ integration outcomes. The consensus in this literature is that difficult initial labor market conditions can have lasting effects on exposed immigrants. In particular, exposure to unfavorable employment conditions upon arrival negatively affects refugees’ economic and social integration (see Åslund and Rooth Citation2007 for Sweden, Godøy Citation2017 for Norway, Marbach et al. Citation2018; Aksoy et al. Citation2020 for Germany, Kristiansen et al. Citation2021 for the Netherlands, see also Fasani et al. Citation2021 for cross-national evidence). In turn, areas with more favorable opportunity structures, including the structural conditions of the housing and labor markets, seem to improve immigrants’ integration (Edin et al. Citation2003; Fasani et al. Citation2021; Khalil et al. Citation2022). There is also some evidence that living in regions with a high concentration of coethnics can improve refugees’ labor market outcomes (see Damm Citation2009 for Denmark; Edin et al. Citation2003 for Sweden; Larsen Citation2011; and Martén et al. Citation2019 for Switzerland).

Moreover, we improve on previous research methodologically. Unlike in previous research where refugees can freely move across regions after being initially assigned, in our study refugees face additional restrictions on their geographic mobility. This means that they are exposed to the same language course opportunities for several years, allowing us to study the dynamics of employment gains from the local language course supply over time.

Using a recent longitudinal survey of refugees in Germany, we show that limited opportunity structures, such as poor access to language courses, significantly reduce employment chances and that this negative effect endures over time. Moreover, poor local language course supply also delays host-country language learning and language course completion and certification in the early years after arrival – the critical period of language learning (Hartshorne et al. Citation2018) – thus slowing immigrants’ integration process in a broader sense. These findings imply that spatial dispersal policies in Europe should consider the local variation in the supply of language courses to reduce inequalities in integration outcomes among immigrants. These actions should be combined with improved funding for language courses in regions with lower supply.

Theoretical background

The role of language courses in immigrants’ integration outcomes

The previous literature on the role of language-supporting policies in immigrants’ economic outcomes can be divided into two strands. First, large-scale, cross-comparative studies examine whether immigrants’ economic outcomes are related to countries’ language policies (Goodman and Wright Citation2015; Koopmans Citation2010; Neureiter Citation2019). The results from these studies are somewhat equivocal. For instance, using European Social Survey (ESS) data, Neureiter (Citation2019) reports a positive correlation between mandatory integration requirements, such as learning the host-country language and immigrants’ entry into paid employment. Likewise, Koopmans (Citation2010) shows a positive correlation between European countries’ policies supporting linguistic and cultural assimilation and immigrants’ integration outcomes. However, other studies suggest that the positive influence of language-supporting policies is overstated. Rather than facilitating immigrants’ integration, these policies function as a control tool to influence migration flows and immigrants’ access to residence and naturalization (Goodman and Wright Citation2015).

The second strand of the literature comprises small-scale, country-specific studies of individual participation in language courses (e.g. Arendt et al. Citation2020; De Vroome and van Tubergen Citation2010; Kaida Citation2013; Kosyakova and Brenzel Citation2020; Lochmann et al. Citation2019). The majority of these studies point to a positive relationship between language course participation and immigrants’ economic outcomes, including refugee populations. While this positive correlation likely reflects a causal link between language course participation and immigrants’ labor market outcomes, it may be spurious and arise from a selection effect. Specifically, if the completion of language courses is positively related to unobserved characteristics – such as individual ambition and an ability to learn – immigrants who complete such a course will experience better economic integration than those who do not, even in the absence of the causal effect of language courses.

Several studies have recently attempted to identify a causal effect of language course participation on immigrants’ economic outcomes. Using longitudinal data on recent immigrants to Canada and propensity score matching, Kaida (Citation2013) showed a less favorable selection of low-skilled immigrants into language training. When immigrants’ selectivity was controlled for, the study revealed a positive impact of language course participation on the probability of exiting poverty. Utilizing a recent change in Danish integration policy and applying a regression discontinuity design, Arendt et al. (Citation2020) showed that refugees who arrived in Denmark in the period of policies introducing intensive language tuition experienced approximately four percentage points higher employment and almost 2,510 USD more in yearly earnings than those who came in the period preceding the policy change.

In this context, the present study has several advantages. First, the state-based allocation of refugees to German counties accounts for refugees’ potential residential selectivity. In other words, refugees’ residential choices are not affected by unobserved individual characteristics such as perseverance and a motivation to work, which are likely to influence the move to counties with a more generous supply of integration programs and integration outcomes. This unique natural experiment circumvents typical challenges in the causal identification of the effect of the local supply of language courses on refugee integration outcomes. Second, given the labor market disadvantages of recently arrived refugees (e.g. Dustmann et al. Citation2017; Kanas and Steinmetz Citation2021), it can be argued that variation in the types and skill levels of the jobs that refugees can find is limited. In fact, the majority of recent refugees in Germany are employed in jobs requiring unskilled and skilled tasks (Brücker et al. Citation2019). Thus, job heterogeneity plays a much smaller role in our sample of recent refugees than in more diverse samples of immigrants analyzed in previous studies (e.g. Arendt et al. Citation2020; Kaida Citation2013). This is important because the effect of language courses is likely to vary across occupations with different language requirements (Chiswick and Miller Citation2010).

The local supply of language courses and refugees’ entry into paid employment

Given this growing evidence on the impact of language courses on immigrants’ and refugees’ economic integration, a greater local supply of language courses should increase local opportunities to participate in such courses and thereby contribute to refugees’ labor market integration in Germany. Following this premise, we anticipate better chances of entering paid employment for refugees who are exogenously allocated to counties with a higher supply of language courses.

Human capital theory (Becker Citation1964), signaling theory (Spence Citation1973; Stiglitz Citation1975), and credentialing theory (Collins Citation1979) offer different explanations for why the local supply of language courses influences refugees’ employment. From a human capital perspective, the local supply of language courses is likely to increase immigrants’ productivity by facilitating the acquisition of host-country-specific knowledge and skills. The supply of language courses is likely to increase exposure to the host-country language and – because of this greater exposure – to facilitate immigrants’ language acquisition (e.g. Kaida Citation2013; Khalil et al. Citation2022; Kosyakova et al. Citation2022; van Tubergen Citation2010). As language courses are often combined with other integration programs, such as civic knowledge and labor market counseling, the supply of language courses is also likely to facilitate other functional skills and knowledge, such as knowing how to apply for a job and participate in an interview, understanding workplace culture and communicating with coworkers (Kaida Citation2013; van Tubergen Citation2010). There is ample support in the literature that immigrants who acquire host-country language significantly improve their economic opportunities (e.g. Chiswick and Miller Citation1995; Dustmann and Fabbri Citation2003).

Following the signaling perspective, the supply of language courses facilitates immigrants’ economic integration because it increases opportunities to complete language courses. Given the incomplete information about potential job-seeker skills and productivity levels, employers rely on various signals. Language certificates may be one such signal, along with formal educational credentials (Liechti et al. Citation2017). However, as most refugees are educated in the country of origin, employers may be less certain about the knowledge and skills these credentials reflect (e.g. Damelang et al. Citation2020; Kanas and van Tubergen Citation2009). In this context, certificates acquired in the host country can signal immigrants’ motivation and trainability to employers (Auer Citation2018; Liechti et al. Citation2017; Lochmann et al. Citation2019).

Another argument for why obtaining a language certificate should facilitate immigrants’ entry into paid employment is that it provides access to certain employment positions, which are otherwise restricted due to social closure (Collins Citation1979). As most occupations require language skills at least at the basic level, they may rely on language certificates to screen potential employees for language proficiency (Chiswick and Miller Citation2010). For instance, De Vroome and van Tubergen (Citation2010) find that among refugees in the Netherlands, integration course completion, the bulk of which is spent on language training, is associated with increased entry into employment and higher occupational status, net of language proficiency. Leveraging allocation policy in Switzerland, Auer (Citation2018) finds that language course certification not only offsets the reduced likelihood of employment in cases of a language mismatch but also has a positive effect on refugees placed in a familiar language region. According to the author, the latter finding supports a signaling explanation according to which employers value refugees’ language proficiency more highly if their skills are accredited by a Swiss institution they trust.

The social capital literature takes a different perspective and argues that the supply of language courses can also provide opportunities to acquire the skills necessary to develop contact with natives (Hoehne and Michalowski Citation2016). Participation in language courses may encourage refugees’ self-confidence in their competencies to engage and cooperate with host society members (Rother Citation2014; Schuller et al. Citation2011). These ‘bridging’ social contacts, in turn, are crucial for immigrants’ labor market success (De Vroome and van Tubergen Citation2010; Kanas et al. Citation2012).

Short- and long-term effects of the supply of language courses

Another relevant question concerns whether the effect of initial conditions on refugees’ integration outcomes is short-lived or long-lasting. Åslund and Rooth (Citation2007) examine the long-term effects of labor market conditions to which refugees are exposed upon arrival on earnings and employment in Sweden. The authors find that the initial exposure to high local unemployment detriments refugees’ labor market integration, leaving trace effects on individual economic outcomes for at least ten years. Godøy (Citation2017) shows that being placed in a labor market with a high immigrant employment rate increases refugees’ annual labor earnings up to six years after immigration. The results for the dynamic effect of social networks are less unequivocal. For instance, in their study of refugees in Switzerland, Martén et al. (Citation2019) find that refugees assigned to locations with many conationals are more likely to enter the labor market. The positive effect of ethnic concentration on employment is most pronounced approximately three years after arrival and weakens with longer residency. Battisti et al. (Citation2022) show positive initial effect of ethnic concentration that wanes four years after arrival. The authors argue that these dynamics are a result of the greater human capital investments of immigrants assigned to locations with fewer conationals.

Two mechanisms could affect the dynamics of the supply of language courses to which refugees are exposed upon arrival. First, initial conditions upon arrival likely affect immigrants’ early experiences, which in turn influence their subsequent labor market outcomes (Hanhörster and Wessendorf Citation2020). Accordingly, refugees placed in a county with poor language course opportunities will accumulate less country-specific human capital (including other knowledge and experience on the German labor market), which, in turn, will decrease their future labor market prospects, regardless of the later supply of language courses. Second, initial conditions upon arrival often predetermine local conditions later. Combined with limited geographic mobility, this means that immigrants placed in a county with poor language course opportunities will be more likely to experience difficult conditions later, even if there are no persisting individual effects (cf. Åslund and Rooth Citation2007; Godøy Citation2017).

The German context

Germany has been an important destination country for humanitarian migration in Europe both historically (Rotte et al. Citation1997) and recently. Of 1.8 million first-time asylum applications submitted between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019 in Europe, Germany absorbed almost half (Eurostat Citation2020). The substantial increase in asylum applications since 2015 has put the German integration policy under unprecedented pressure (Brücker et al. Citation2020; Kosyakova and Brücker Citation2020). Several policy amendments have been implemented to facilitate the social and economic incorporation of newly arrived refugees. In the following paragraphs, we discuss the policy changes that are particularly relevant to the context of our study.

Integration and language courses

In Germany, refugees whose asylum applications are approved by the German authorities are offered vouchers to participate in state-provided, mandatory integration courses commissioned by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF). Since 2015, vouchers providing access to integration courses have been extended to refugees with a pending asylum application but good prospects for recognitionFootnote2 and tolerated refugees (i.e. whose asylum application has been rejected but whose stay in Germany is tolerated until deportation, Duldung) (Kosyakova and Brenzel Citation2020).

The integration courses’ main purpose is to offer lessons in the German language for newly arrived refugees (600 hours for the general course; 900 for special courses; and 400 for intensive courses) alongside 100 further hours of an ‘orientation’ course providing basic knowledge about German legal systems, history, and culture (Rother Citation2014). Referring to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), integration courses are aimed at reaching proficiency level B1 (a.k.a., independent user, see Council of Europe Citation2001). The overarching goal of integration courses is to promote refugees’ social and economic incorporation into German society.

Between 2014 and 2016, the number of integration courses doubled, and the number of commenced courses was approximately 20,000 in 2016 (Grote Citation2018). In addition to integration courses, a number of further measures for learning the German language (including German for professional purposes) were offered by the authorities of federal states, municipalities, charitable associations, and nongovernmental organizations as well as by additional volunteers (Brücker et al. Citation2020; Kosyakova and Brenzel Citation2020). Despite the increased supply of integration and language courses, only one-third of the refugees who arrived between 2013 and 2016 were enrolled in an integration course in 2016. This number increased to 55 percent of refugees in 2017 (Brücker et al. Citation2019).

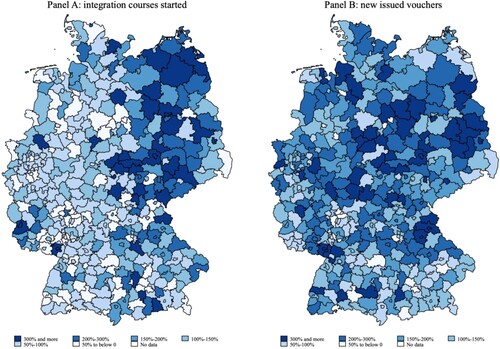

Notably, the supply of language courses varies considerably across counties, and differences in demand cannot explain this variation. Panel A of illustrates the percentage change in integration course supply between 2015 and 2016 in Germany, while Panel B depicts the percentage change in issued vouchers for participation in integration courses for the same period (BAMF Citation2020). It is clear that the change in the supply of language courses does not go hand-in-hand with corresponding demand: While the increase in vouchers issued more than doubled in 165 counties, the supply of language courses doubled in less than half of these counties.Footnote3 For instance, per 34 new courses started in Potsdam in 2018, there were 462 newly issued vouchers. At the same time, the number of newly issued vouchers in Goeppingen amounted to 954 per 34 new courses started.

Figure 1. Percentage changes in the number of started integration courses (Panel A) and the number of new vouchers issued for participation in an integration course (Panel B), 2015-2016. Data source: BAMF (Citation2020), own calculations.

Following the Federal Ministry of the Interior (BMI), the supply of integration courses is determined by local conditions such as the sufficient number of potential participants and the number of competitors in the region (BMI Citation2006). At the same time, the BMI’s (Citation2006) evaluation results suggest that high population density and a high share of foreigners are comparatively favorable conditions for integration courses to take place. The differences in regional incidences of integration courses are also dependent on waiting periods until integration courses may start, which are more pronounced in rural areas with fewer foreigners. Finally, while financing integration courses is governed at the state level, course providers might benefit from regional resources such as qualified personnel or material infrastructure, support by nongovernmental organizations, donations and voluntary work.

Labor market access

Legal restrictions on work are evidently essential for refugees’ employment prospects. In Germany, refugees’ labor market access is determined by legal status and country of origin. While refugees with an approved asylum application have unlimited access to the labor market equal to that of German citizens, those with a pending asylum application and those with tolerated status face some restrictions. Unless they came from safe countries of origin and applied for asylum after August 31, 2015Footnote4, both groups may access the labor market after a three-month blocking period following their arrival in Germany (§ 61 AsylG) under certain conditions. These conditions include (1) approval from the relevant immigration office, (2) a comparability test regarding the conditions of work and remuneration (Vergleichbarkeitsprüfung) conducted by the Federal Employment Agency (BA), and (3) in certain counties of the BA, a priority test (Vorrangprüfung) determining whether an alternative person with priority status (i.e. a German or privileged foreign national) can fill the relevant position (Brücker et al. Citation2019).

Residential allocation and residency obligation policies

Refugees are distributed according to dispersal policies to ensure equal distribution across German counties (Kreis) (Schneider Citation2012) in two- or three-stage procedures (Entorf and Lange Citation2019). First, refugees are allocated across the German Federal States (Länder) according to a key based on population size and tax revenues (see Figure S1 and Table S1 in Supplementary Material). This allocation is regulated by the German Asylum Act and carried out by the EASY system – an IT application run by the BAMF. The authorities of the Federal States are then responsible for the further distribution of the assigned refugees within their territory: across counties or municipalities. Importantly, the ongoing mechanisms for the regional distribution of refugees are not based on how well the counties or municipalities are able to accommodate, care for, and integrate assigned refugees (Geis and Orth Citation2016). In most cases, the allocations across counties or municipalities are regulated by state law and only take into account the local population size (see Geis and Orth Citation2016, 7–8 for an overview of the local allocation schemes).Footnote5 However, Gehrsitz and Ungerer (Citation2018) argue that the availability of suitable accommodations has played an important role in refugees’ allocation across counties or municipalities, particularly in 2015, while the findings by Entorf and Lange (Citation2019) imply that the factual allocation of refugees in 2015 was strongly driven by urban areas and to some extent by the local unemployment rate.

After initial allocation, refugees can formally apply for asylum. This first residential allocation is binding. Refugees with pending or rejected asylum applications face stringent residency obligations, including travel bans (Residenzpflicht, §56 Residence Act). The obligation to reside in the initial allocation county can be abolished upon the official approval of refugee status. These rules were modified with the Integration Act in August 2016. Since then, approved refugees have also been required to reside in the federal state in which their asylum application was processed for an additional three years after approval (§12a, Residence Act).Footnote6 In seven of 16 federal states, refugees are even required to reside within an assigned county and sometimes even within a municipality – typically the location where their asylum application was approved (BAMF Citation2019; Brücker et al. Citation2019). Since Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg represent only one county each, these three states can also be considered more restrictive after the reforms. Consequently, the residency obligation prolongs refugees’ initial distribution for a substantial period, even after their asylum application is approved.

Data and method

The IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees

The IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (Citation2021) is a nationally representative longitudinal household survey of asylum seekers and refugees in Germany launched in 2016 (Brücker et al. Citation2020). The data were drawn from the Central Register of Foreign Nationals (Ausländerzentralregister, AZR). The sampling frame targeted the population of refugees who arrived in Germany from January 2013 to January 2016 (irrespective of their current legal status by the sampling date). The response rate of the first wave amounted to approximately 50 percent, which, compared to those of other surveys of individuals with a migration background, is relatively high (Kroh et al. Citation2017). In the second wave, an additional sample was added to increase the sample size and cover refugee arrivals up to January 2017. The survey itself covers the respondents and all household members of the respondents. For our analyses, we pooled four waves of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees. The original data comprised 18,342 person-observations (8,321 persons).

Analytical sample

Estimating the causal effect of the supply of language courses on immigrants’ integration can be challenging due to immigrants’ residential sorting. For example, those who are more able or willing to find employment may move to areas with a larger supply of language courses due to higher expected opportunities to learn the language and obtain a language certificate. Thus, the positive association between the supply of language courses and immigrants’ integration outcomes could be biased due to the sorting of immigrants with more favorable characteristics into counties with more language courses.

To control for immigrants’ sorting across German counties, we consider only refugees subject to restrictive residency obligations during their interviews. As discussed in the German context section, the German residential allocation policy ensures that (1) refugees cannot choose their initial county of residence, i.e. there is no initial residential sorting; (2) those subject to restrictive residential policies are bound to stay in the initial county for a pronounced period of time, i.e. there is no postallocation residential sorting; and (3) counties cannot decide on the number of asylum seekers they want to host, i.e. the local supply of integration courses does not drive refugees’ allocation process. Following these preconditions, the local supply of integration courses should be independent of refugees’ individual employment chances. However, while allocation policies address the issue of refugees’ regional sorting due to individual (un)observables, unobserved county characteristics that correlate with a local supply of language courses might still bias the effect of the supply of language courses on refugees’ integration outcomes. To validate all three preconditions, we additionally perform several robustness checks in Supplementary Material Tables S2–S4. In a nutshell, our results imply that (1) local refugee stock is unrelated to the supply of language courses, (2) the supply of language courses is not related to refugees’ individual characteristics, and (3) the supply of language courses is related to the previous language course supply and county economic prosperity. Hence, we control for relevant county characteristics in our analyses (see the next section).

Turning to the definition of our analytical sample, we restrict our data to refugees subject to restrictive residency obligations during their interviews. This restriction covers (1) refugees with a pending decision on their asylum application, (2) those with a negative decision, and (3) approved refugees who received their approval in one of the ten restrictive federal states after the residence obligation at the county or municipal level became effective in that federal state and whose interviews were conducted not later than three years after their arrival in Germany (see German context section). Given that we require the timing of the asylum decision and the federal state of assignment to define the sample, respondents with missing corresponding information were automatically excluded. The analytical sample was further restricted to refugees with a first asylum application (because the residence obligation is unclear in cases of several applications), those aged 18–64 at the first interview (since people in this age group are more likely to be active in the labor market), and those whose initial interview occurred during their first three years of residence in Germany (to reduce recall memory bias). explains the sample selection in more detail. Our final sample includes 5,467 person-observations (2,730 persons). While our sample restrictions clearly imply a smaller fraction of the entire population of refugees arriving to Germany in the recent decade, it ensures that the refugees in question have been exogenously placed.Footnote7

Table 1. Analysis samples after cases were excluded from the original samples.

Measures

In our empirical analysis, we consider several integration outcomes for refugees. Unweighted descriptive statistics for dependent and independent variables are presented in .

Table 2. Unweighted descriptive statistics on model covariates.

Paid employment is based on self-reported employment status. Employed respondents (employees subject to social insurance contributionsFootnote8 and those marginally employed) contrast with those without paid work (those unemployed, currently available and seeking work, and inactive). Roughly 10 percent of the refugees were employed in 2016, while the share increased to 38 percent in 2019 (weighted results).

German language proficiency is based on self-reported German language skills. Respondents rated their reading, speaking, and writing skills on a scale of 0 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘very well.’ We compiled an additive index of these three measures ranging from 0 to 12. The internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha, is very high and reaches 0.937. In 2016, nine percent of refugees reported having good or very good German language skills. The mean language proficiency index amounted to 4.5, reflecting ‘not very well’ to ‘average’ language skills. In 2019, the share of refugees with good or very good German language skills increased to 37 percent, while the language proficiency index increased to 6.9, reflecting ‘average’ language skills (weighted results).

Completion of an integration course is based on self-reported integration course completion. Refugees who completed an integration course are contrasted with those who did not complete a course, i.e. those who either started a course but did not (yet) complete it or who were never enrolled in a course. While in 2016 only nine percent of the refugees completed an integration course, in 2019, this number increased to roughly half of the refugees (weighted results).

Obtainment of a language certificate is based on self-reported language certification. Refugees who completed a language course (not restricted to an integration course) and received a certificate (of the A1-C2 levels following the CEFR) are contrasted with those who either did not participate in a language course or did participate but did not obtain a certificate or obtained some other nonspecified certificate. Approximately 14 percent of the refugees who completed a language course received a certificate in 2016, while the share increased to 71 percent in 2019 (weighted results).

For contact frequency with Germans, we consider self-reported information on how often the respondents have contact with Germans. The possible responses were arranged on a scale of 0 ‘never’ to 5 ‘every day.’ We coded the variable such that a high score represents more frequent social contact with Germans. Seventeen percent of the refugees reported having no German contacts in 2016 (weighted results). In 2019, the share of refugees with no German contacts reduced marginally to 15 percent.

As formulated in the previous section, we are interested in a causal effect of local language course supply measured via the county-level supply of integration courses.Footnote9 The variable is defined as the number of started integration courses in the initial county of residence divided by the number of ‘course vouchers’ (Teilnahmeberechtigungen für Integrationskurse) issued for participation in the integration course (BAMF Citation2020). Between 2013 and 2019, the average supply of integration courses in a county was approximately 34 courses per 680 issued integration course vouchers (own calculation based on BAMF Citation2020). In other words, per started integration course, there were on average 20 new course vouchers. For the empirical analyses, we standardize the supply of language course variables to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Higher values indicate a higher county-level supply of language courses.

The following individual-level variables are included as controls. Premigration years of education are used as a continuous measure of self-reported years of schooling, vocational training, and higher education before arrival in Germany. Having premigration work experience is a binary indicator that equals one if the respondent had ever worked before arriving in Germany (zero otherwise). Among the sociodemographic variables, we account for the country of origin (aggregated to Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Eritrea, Iran, other MENA countries, former USSR countries, the western Balkan region, other African countries, and other countries), the duration of stay (in months divided by twelve), being female, having children aged below 16 in the household, arrival to Germany with family (versus alone or with others), having premigration support from family or relatives in Germany (versus no such support), age at the first interview, and having traumatic experiences (during flight to Germany). We also control for the status of the asylum request (approved, rejected, pending, or no application) since it is related to prospects of staying in Germany and may affect a decision to invest in the destination language (Kosyakova and Brenzel Citation2020). The survey sample and year are controlled to absorb any systematic differences related to the survey design.

While a natural experimental design such as ours ensures that other county characteristics are randomly distributed across refugees, the supply of language course effect might be driven by unobserved county characteristics that correlate with a local supply of integration courses. Hence, we account for potential confounders by augmenting our data with the following characteristics fixed to the county of first residence and arrival year. County-level population density considers the number of people living in a county area per square kilometer (DESTATIS Citation2021b, Citation2021d). Local economic conditions are proxied via the county-level unemployment rate (in percent; DESTATIS Citation2021e). We also control for the county-level share of foreigners (DESTATIS Citation2021a), county-level concerns about immigration to Germany (SOEP Group Citation2021), and the county-level share of CDU/CSU voters (DESTATIS Citation2021c) to address local demand for integration courses and support for such integration policies. Finally, federal state fixed effects are controlled to absorb any systematic differences between German federal states.

Empirical strategy

We estimate three linear probability models (LPM; for paid employment, completion of an integration course, and obtainment of a language certificate obtainment) and two ordinary least squares models (OLS; for German language proficiency, and frequency of contact with Germans) with standard errors clustered at the person level to account for the fact that some refugees are surveyed repeatedly. Corresponding models are specified in Equationequation (1(1)

(1) ):

(1)

(1) where

denotes the outcome variable of respondent i in survey year t: (1) paid employment, 2) German language proficiency, 3) completion of an integration course, 4) obtainment of a language certificate, and 5) frequency of contact with Germans.

denotes the supply of integration courses of assigned county

in the year of arrival

, vector

denotes time-invariant individual-level characteristics, vector

denotes time-variant individual-level characteristics, and vector

denotes the characteristics of the assigned county in the year of arrival.

denotes fixed effects for year of interview t.

denotes fixed effects for assigned federal state f.

is the error term. The results are robust to clustering standard errors at the federal state or governmental district (Regierungsbezirke, i.e. regional mid-level local government units) or counties (see Table S8 in Supplementary Material).

To address item nonresponse, we apply multiple imputation using chained equations (van Buuren Citation2012). We estimate 20 imputed datasets with complete information. Following Rubin’s (Citation1987) approach, we then combine the results of the analyses of each dataset. Table 1 (column 4) illustrates that missing information was present to varying degrees across measures.

Results

The supply of integration courses and refugees’ employment

We start by examining the effect of integration course supply on refugees’ probability of employment. Model 1.1 in shows that the coefficient of the supply of language courses is positive and statistically significant. An increase of one standard deviation in the supply of language courses increases the probability of refugees’ employment by three percentage points. Interestingly, the interaction term between the supply of language courses and length of residence is positive but statistically insignificant (p = .282, Model 1.2, ). These results suggest that the advantage of being exposed to an initially higher supply of language courses is not affected by the length of residence.

Table 3. Probability of paid work, average marginal effects in percentage points (p.p.).

To examine whether these results vary by refugees’ or county characteristics, we tested a number of interaction effects between the local supply of integration courses and individual- and county-level variables. The results are presented in Table S6 in Supplementary Material. Two interaction effects are significant. First, we observe that the supply of integration courses is significantly less beneficial for refugees with premigration work experience (Model 1.1.2). This finding could imply that refugees with premigration work experience require more job-specific language courses and other programs facilitating employment, such as career advice, assistance with creating a job profile, competence assessments, or placement in further education courses. Second, the supply of integration courses has a significantly stronger effect on refugees’ employment in counties with populations more concerned with immigration (Model 1.1.13). In their recent conjoint experiment, Bansak et al. (Citation2016) showed that a lack of host-country language skills increases anti-immigrant sentiment against refugees in Switzerland (see also Getmansky et al. Citation2020). Accordingly, local anti-immigrant sentiment may increase refugees’ incentives to invest in destination language skills in Germany and thus increase the impact of the supply of language courses on their employment probability.

Intermediary outcomes

Next, to provide insights into possible channels through which integration course supply affects refugees’ employment, we regress four intermediary outcomes. This approach allows for a causal interpretation and quantification of the total effect of integration course supply on refugees’ integration outcomes.

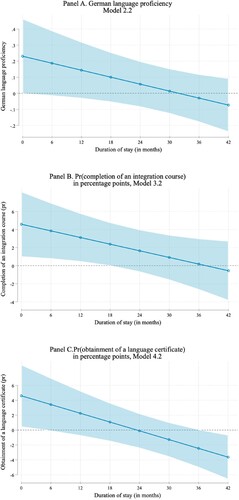

Model 2.1 () shows no significant effect of the supply of integration courses on German language proficiency on average. However, the inclusion of the interaction effect between the supply of language courses and duration of stay in Model 2.2 does show that the effect varies with the length of residence. To provide a graphical illustration of this effect, we show simple slopes based on quantitative predictions calculated as marginal effects with a 95 percent confidence interval. The marginal effects estimation considers the main effect of the supply of language courses on refugees’ language proficiency and the interaction effect between integration course supply and duration of stay. Panel A in reveals that an increase of one standard deviation in the supply of language courses increases refugees’ language proficiency by approximately 0.2 points among refugees in the first six months of stay in Germany. However, the effect decreases and becomes nonsignificant for those with a longer duration of stay (more than 12 months; see also Table S12 in Supplementary Material). These findings imply the positive effect of integration course supply on refugees’ German language proficiency, particularly in the initial integration phases.

Table 4. Intermediary outcomes: German language proficiency, completion of an integration course, obtainment of a language certificate, and contact with Germans.

Next, we examined whether the local supply of language courses also facilitates refugees’ completion of integration courses and obtainment of language certificates. Similar to the findings for language proficiency, our results show that integration course supply positively influences integration course completion and language course certification, although these positive effects again decrease with refugees’ duration of stay in Germany (, Models 3.2 and 4.2). Specifically, Panels B and C in show that an increase of one standard deviation in the supply of language courses increases the probability of integration course completion and certification by approximately 4–5 percentage points among refugees with a short duration of stay in Germany (less than six months). However, the effects of the supply of language courses decrease and become nonsignificant for refugees with a longer duration of stay in Germany (more than 24 months for integration course completion; more than 12 months for language course certification; see also Table S12 in Supplementary Material).Footnote10

Figure 2. Average marginal effect (AME) of county-level supply of integration courses by duration of stay on various outcomes shown in , with 95% CI. Data source: IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees 2016–2019 (D OI: 10.5684/soep.iab-bamf-soep-mig.2019).

As the fourth intermediary outcome, we considered refugees’ contact with German natives. The effect of county-level integration course supply on refugees’ contact with German natives was found to be not statistically significant even after considering the possible interaction with refugees’ duration of stay (, Models 5.1 and 5.2). A similar conclusion is derived when a more elaborate measure of contact frequency with Germans (also taking into account contact frequency with German neighbors, work colleagues, and friends) is considered (Table S11, Model 7.2 in Supplementary Material).

Finally, we tested whether the effect of integration course supply is robust to the inclusion of refugees’ language proficiency, integration course completion or language course participation, and contact with natives – the potential channels through which local language courses supply likely contributes to refugees’ employment prospects as shown in .Footnote11 We include all intermediary outcomes separately (Models 1.3-1.6) and jointly in one model (Models 1.7-1.8). Given the strong correlation between integration course completion and language course certification (see Table S7 in Supplementary Material), we restrain from including both variables in one specification. Overall, Model 1.7 implies a superior model fit as indicated by adjuster R2.

Table 5. Probability of paid work and intermediary outcomes, average marginal effects in percentage points (p.p.).

Interestingly, we observe that the effect of the supply of integration courses is marginally increased relative to Model 1.1 in . Hence, the local supply of integration courses also shapes refugees’ employment directly when controlling for intermediary outcomes (, Model 1.7). Moreover, we observe that when included separately, all intermediary outcomes are positively related to refugees’ employment probability. However, the joint model reveals that German language proficiency per se is not significantly related to refugees’ employment probability, while integration course completion and contact with Germans are.Footnote12

We can derive three important insights from our findings. First, the local supply of integration courses significantly increases refugees’ employment chances, and this effect is persistent over the duration of stay. Second, the local supply of integration courses significantly affects further intermediary outcomes, such as refugees’ language proficiency (though the effect is modest), language course completion and certification, but only in the initial periods since arrival; it has, however, no effect on social contact with natives. Third, intermediary outcomes – particularly the completion of an integration course – are significantly related to employment chances. In sum, the local supply of integration courses seems to be particularly relevant for refugees’ labor market integration in the long run, while in the short run, it seems to additionally benefit refugees’ integration by promoting their chances of completing an integration course.

Discussion

This paper examines the impact of the local supply of integration courses on refugees’ labor market integration in Germany. In response to the largest influx of refugees since the end of World War II, Germany introduced several policy measures, most notably language courses aiming to facilitate the integration of newly arrived immigrants into German society. However, despite the increased supply of language courses in recent years, the targeted demand has not been fully met, partly due to considerable variation across counties in the supply of language courses (Brücker et al. Citation2020).

This paper contributes to previous research by examining how geographic variation in local opportunity structure malleable by policy affects refugees’ integration. Our study is novel and important in at least two ways. First, we exploit the German spatial dispersal and residential obligation policies, which can be regarded as a natural experiment to investigate the causal effect of the local supply of language courses on refugees’ labor market integration. Unlike in previous research, refugees subject to residential obligation policies cannot freely move across regions after being initially assigned. Hence, our design allows to control for both initial and post-arrival residential selection. Second, we look at the intermediary outcomes – language proficiency, language course completion and certification, and contacts with natives – through which the local opportunity structure of language courses may additionally shape refugees’ economic integration.

Using recent longitudinal data from the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees, we find that the local supply of language courses positively influences the probability of refugees entering paid employment. An increase of one standard deviation in the supply of language courses facilitates refugees’ entry into paid employment by three percentage points. Importantly, this effect is persistent over refugees’ duration of stay. Given that the effect of language course supply is calculated over a rather specific subsample (i.e. refugees with restricted geographic mobility and a shorter duration of stay), we can assume that this estimation is rather conservative.

The effect is not only statistically significant but also of economic relevance. We follow Aksoy et al. (Citation2020, 20) to infer the potential fiscal effects of our results. The rough calculations suggest that allocating 10,000 randomly selected working-age refugees to a county with a one standard deviation greater supply of language courses would generate annual savings of approximately one and a half million euros (0.0312*10,000*4800 euros = 1,497,600, cf. , Model 1.7).Footnote13 Given that the average duration of stay for our sample is approximately 2.5 years (see ), earlier labor market integration likely improves following labor market trajectories. Moreover, the young age structure of recent refugees and correspondingly considerable remaining working life may generate substantial fiscal gains. Instead of reallocating refugees to a county with a better opportunity structure, policymakers could increase the local provision of language courses. Clearly, this would include additional costs: roughly 2000€ per one refugee (Elfering and Zacharakis Citation2015). An increase of supply by one standard deviation, that is, by one course for 20 participants would increase investment costs for the state by roughly forty thousand euros (20*2000 = 40,000€). Following calculation above, the annual saving due to lower welfare state payments for 20 refugees would amount to three thousand euros (0.0312*20*4800 = 2995€) in a given year. Hence, the investments in language courses are returned approximately after thirteen years. Note, that this conservative estimate does not consider public finance benefits from taxes and social insurance contributions that employed refugees would pay.

We also point out four potential channels through which the local supply of language courses affects refugees’ entry into paid employment. Concerning the main channel – learning a host-country language – our estimates reveal an improvement in German language skills for refugees assigned to counties with more language courses, although only in the early phases of residence in Germany. However, the effect seems to be quite modest. This finding conforms to Khalil et al. (Citation2022) results that being allocated to rural (versus urban areas) in Germany had a small negative but insignificant effect on the language acquisition of recently arrived refugees. According to the authors, two processes offset each other here. While refugees in rural areas have lower access to integration courses, they have more regular exposure to German native speakers. On the other hand, our results also point toward two other channels: signaling and social closure. Refugees assigned to counties with more language courses are significantly more likely to complete a course and receive a language certificate than those assigned to counties with fewer language course opportunities. The effect of the supply of language courses on language learning and completion (with and without certification) is significantly stronger for recent refugees than for refugees with longer residence in Germany. In fact, the supply of language courses appears to have no significant effect on refugees with more than 24 and 12 months of residence in Germany.

We find little evidence that the supply of language courses facilitates the social integration of refugees. This conclusion remains unaffected even after considering that the effect of the supply of language courses on the frequency of contact with German natives may vary with the duration of stay in Germany. While the direct effect of integration course supply on refugees’ contact frequency with natives should be further investigated in future research, it is likely that language policies benefit the social integration of refugees indirectly through improved language skills.

Our findings have important implications for language supporting policies as a means of facilitating immigrants’ integration. We find that the local supply of language courses not only benefits the economic integration of refugees by facilitating their entry into paid employment but also positively affects other integration outcomes, such as completing a course and acquiring language certification, in the first 24 and 12 months since arrival. From a policy perspective, the latter finding implies that integration course curricula should emphasize not only immigrants’ language acquisition but also formal completion and certification through language courses.

Given the recent empirical evidence on the importance of language training for immigrants’ integration outcomes (Arendt et al. Citation2020 in Denmark; Kaida Citation2013 in Canada; Lochmann et al. Citation2019 in France; Sarvimäki and Hämäläinen Citation2016 in Finland), we argue that this knowledge is also relevant beyond the German context and the particular target group that refugees represent. Our findings also have implications for residential allocation policies. By restricting initial and post-arrival regional mobility, destination countries make it challenging for refugees to tap into regions with the best integration course opportunities, dampening refugees’ integration prospects from the outset (Brücker et al. Citation2020) but also increasingly reducing potential fiscal revenues and increasing public spending on welfare benefits (Bansak et al. Citation2018). Therefore, the local provision of integration courses – which mainly focus on language acquisition – should be taken into account in residential allocation policies, as limited access to language courses can delay German language learning, course completion, and labor market entry, thus slowing the integration of recently arrived refugees. These actions should be combined with improved funding for language courses in regions with lower supply.

Code availability

The computer codes for data preparation and analyses are available at https://osf.io/t8wq9. This study design and analysis was not preregistered.

Ethical approval

This study analyzed secondary data. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Asylum -seekers and refugees are a particularly vulnerable target group due to their experiences of war, flight, expulsion, and their legal status, and who require special protection and for whom there is a corresponding special responsibility. Therefore, a code of ethics has been developed, which includes the following measures: (1) Consent was obtained by providing all participants with a declaration of data protection indicating that participation was voluntary, and identities would be kept confidential; (2) Respondents have been informed that their participation or non-participation will not affect a possible asylum procedure; (3) Sensitive questions that can provoke re-traumatization have been avoided.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (819.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Hannah Gosse for her assistance in the analysis of the study; and all those who commented on the earlier presentations of this work at the following events: Dag van de Sociologie at the Utrecht University (online, June 2021), the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) general conference (online, August-September 2021), Sociology Department Research Seminar Series at the Trinity College Dublin (online, September 2021), the Annual Conference of the European Consortium for Sociological Research (ECSR) 2021 (online, October 2021), the 14th Annual conference of the International Network of Analytical Sociologists (INAS) (Florence, May 2022). Both authors contributed equally and are listed in alphabetical order.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

This study uses the factually anonymous data of waves 2016–2019 of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees. The survey is conducted jointly by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), the research data center of the Federal German Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), and the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW). Data access was provided via researchers’ contacts at the IAB. External researchers may apply for access to these data by submitting a user-contract application to the SOEP Research Data Center (https://www.diw.de/en/diw_02.c.222836.en/data_access_and_order.html). DOI: 10.5684/soep.iab-bamf-soep-mig.2019.

Notes on contibutors

Agnieszka Kanas, Dr., is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Politics at the Erasmus University Rotterdam (EUR). Her current research interests are immigrants’ economic disadvantage and integration, comparative policy analysis, and social inequalities. Her work has been published in various academic journals, including European Sociological Review, International Migration Review, Political Psychology, Social Forces, Social Psychology Quarterly, and Social Science Research.

Yuliya Kosyakova, Dr., is Senior Researcher in the Migration and International Labour Studies department at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), head of the Project IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (with H. Brücker), head of the Project Survey of Ukrainian Refugees 2022 (with H. Brücker and S. Schwanhäuser), head of the Working Group ‘Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (with L. Pohlan), and Associate Lecturer at the Chair of Sociology (Social Stratification) at the Otto-Friedrich University of Bamberg. Her current research interests are economic disadvantage and integration of refugees and other immigrants, gender, and social inequalities. Her work has been published in various academic journals inter alia European Societies, European Sociological Review, International Migration Review, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Public Opinion Quarterly, Sociology of Education, and Work, Employment and Society.

Notes

1 Henceforth, the term ‘refugees’ is used colloquially and includes all persons who move to another country for humanitarian reasons, irrespective of their legal status (e.g., refugee, asylum-seeker, or other humanitarian immigrant). Note that when we use the term ‘immigrants,’ we refer to all immigrants, including refugees and other immigrants.

2 These include applicants from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Eritrea (since November 2015), and Somalia (since August 2016).

3 The maximum number of participants in integration courses is restricted to 25 participants (Tissot et al. Citation2019).

4 These include applicants from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ghana, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Senegal and Serbia.

5 City-states Berlin and Hamburg have no subordinate allocation but assign refugees within the city; North Rhine-Westphalia additionally considers land size in its allocation key; Brandenburg considers local labor market conditions (Geis and Orth Citation2016).

6 Exceptions apply for employees subject to social security contributions with at least 15 weekly working hours and a monthly income of approximately 700 €.

7 Supplementary Material discusses analyses of selection into the analytical sample (Table S5). Importantly, selection into the analytical sample is not driven by local language course opportunities.

8 This definition includes individuals who are full- and part-time employed and those in paid internships or apprenticeships.

9 Beyond integration courses, publicly funded courses include labor market integration measures with language components offered by the Federal Employment Agency (with most first introduced in 2015) and the ESF-BAMF courses for German for work (Kosyakova and Brenzel Citation2020). Nonpublicly funded courses may include those provided by volunteers or similar organizations or universities. However, while integration courses can be considered a main language program at the national level with an established comprehensive program and preexisting infrastructure, other courses were introduced in an ad hoc manner shortly after the immigration surge, lacked standardized curriculum, and were subjected to short-term funding.

10 An additional analysis of the effect of integration course supply on participation in integration courses shows similar conclusions (Table S11, Model 6.2 in Supplementary Material).

11 Decomposing the effect of language course supply into direct and indirect (mediated) effects would require adding separate instruments to the mechanisms and thus yield a less parsimonious model specification (Hayes Citation2022; Huber, Citation2016). The mediation analysis assumes that, apart from the treatment itself (the supply of language courses), no further characteristics jointly influence any of the mediators and the outcome (Hayes Citation2022; Huber, Citation2016). This assumption is likely to be violated in our model, leading to biased estimates and incorrect conclusions regarding the presence and magnitude of a mediated effect.

12 Our results are robust to the alternative sample and model specifications. For details, refer to Supplementary Material.

13 Refugees with valid residence status who are not in employment or education are entitled to the same social benefits as natives in Germany. Since few refugees have been employed for a period of 12 months, this means that refugees who are unemployed receive on average 400 euros of monthly unemployment benefits II ("Hartz IV"), corresponding to 4800 euros per year. This is an underestimate of the actual cost to the state of refugees’ unemployment, as it excludes government spending on housing and health care, social benefits, as well as lost tax revenues (Aksoy et al. Citation2020).

References

- Aksoy, C. G., Poutvaara, P. and Schikora, F. (2020) ‘First time around: local conditions and multi-dimensional integration of Refugees’, SSRN Electronic Journal, doi:10.2139/ssrn.3738561.

- Arendt, J. N., Bolvig, I., Foged, M., Hasager, L. and Peri, G. (2020) ‘Language training and refugees' Integration’, In National Bureau of Economic Research, doi:10.3386/w26834.

- Åslund, O. and Rooth, D.-O. (2007) ‘Do when and where matter? initial labour market conditions and immigrant earnings’, The Economic Journal 117(518): 422–448. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02024.x.

- Auer, D. (2018) ‘Language roulette – the effect of random placement on refugees’ labour market integration’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44(3): 341–362. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1304208.

- BAMF (2019) Personal and e-mail communication with the research center of the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) (November, 2019).

- BAMF. (2020) Integrationskursgeschäftsstatistik 2013-2019 (Landkreise und kreisfreie Städte). Integrationskursgzahlen; Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF). https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/Integrationskurszahlen/Kreise/2018-gesamt-integrationskursgeschaeftsstatistik-kreise-xlsx.html?nn=284810

- Bansak, K., Ferwerda, J., Hainmueller, J., Dillon, A., Hangartner, D., Lawrence, D. and Weinstein, J. (2018) ‘Improving refugee integration through data-driven algorithmic assignment’, Science 359(6373): 325–329. doi:10.1126/science.aao4408.

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J. and Hangartner, D. (2016) ‘How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers’, Science 354(6309): 217–222.

- Battisti, M., Peri, G. and Romiti, A. (2022) ‘Dynamic effects of Co-ethnic networks on immigrants’ economic Success’, The Economic Journal 132(641): 58–88. doi:10.1093/ej/ueab036.

- Becker, G. S. (1964) Human Capital, Columbia University Press.

- BMI (2006) Evaluation der Integrationskurse Nach dem Zuwanderungsgesetz: Abschlussbericht und Gutachten über Verbesserungspotentiale bei der Umsetzung der Integrationskurse, Bundesministerium des Inneren (BMI). https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Integration/Integrationskurse/Kurstraeger/abschlussbericht-evaluation.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5

- Brücker, H., Hauptmann, A. and Jaschke, P. (2020) ‘Beschränkungen der Wohnortwahl für anerkannte Geflüchtete: Wohnsitzauflagen reduzieren die Chancen auf Arbeitsmarktintegration’, IAB Kurzbericht 3.

- Brücker, H., Jaschke, P. and Kosyakova, Y. (2019) Integrating Refugees Into the German Economy and Society: Empirical Evidence and Policy Objectives, Migration Policy Institute.

- Brücker, H., Kosyakova, Y. and Vallizadeh, E. (2020) ‘Has there been a “refugee crisis”? New insights on the recent refugee arrivals in Germany and their integration prospects’, Soziale Welt 71(1–2): 24–53. doi:10.5771/0038-6073-2020-1-2-24.

- Chiswick, B. R. and Miller, P. W. (1995) ‘The endogeneity between language and earnings: international analyses’, Journal of Labor Economics 13(2): 246–288. doi:10.1086/298374.

- Chiswick, B. R. and Miller, P. W. (2010) ‘Occupational language requirements and the value of English in the US labor market’, Journal of Population Economics 23(1): 353–372. doi:10.1007/s00148-008-0230-7.

- Collins, R. (1979) The Credential Society, Academic.

- Council of Europe (2001) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment, Cambridge University Press.

- Damelang, A., Ebensperger, S. and Stumpf, F. (2020) ‘Foreign credential recognition and immigrants’ chances of being hired for skilled jobs—evidence from a Survey experiment Among Employers’, Social Forces 99(2): 648–671. doi:10.1093/sf/soz154.

- Damm, A. P. (2009) ‘Ethnic enclaves and immigrant labor market outcomes: quasi-experimental Evidence’, Journal of Labor Economics 27(2): 281–314. doi:10.1086/599336.

- DESTATIS (2021a) Bevölkerung nach Geschlecht, Nationalität und Altersgruppen (21) - Stichtag 31.12. - (ab 2011) regionale Tiefe: Kreise und krfr. Städte. Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes, Bevölkerungsstand (Anzahl) (Tabelle 12411-03-03-4), Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS, Federal Statistical Office). https://www-genesis.destatis.de/

- DESTATIS (2021b) Bevölkerung nach Geschlecht; regionale Tiefe: Kreise und krfr. Städte. Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes Bevölkerungsstand (Anzahl) (Tabelle 12411-01-01-4), Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS, Federal Statistical Office). https://www-genesis.destatis.de/

- DESTATIS (2021c) Bundestagswahlen: Wahlberechtigte, Wahlbeteiligung, gültige Zweitstimmen nach ausgewählten Parteien - Wahltag - regionale Tiefe: Kreise und krfr. Städte Allgemeine Bundestagswahlstatistik (Tabelle 14111-01-03-4), Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS, Federal Statistical Office). https://www-genesis.destatis.de/

- DESTATIS (2021d) Gebietsfläche in qkm - Stichtag 31.12. - regionale Tiefe: Kreise und krfr. Städte; Feststellung des Gebietsstandes (Tabelle 11111-01-01-4), Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS, Federal Statistical Office). https://www-genesis.destatis.de/

- DESTATIS (2021e) Regionalatlas Deutschland Themenbereich “Erwerbstätigkeit und Arbeitslosigkeit” Indikatoren zu “Arbeitslosenquote, Anteil Arbeitslose”, Regionalatlas Deutschland (Tabelle AI008-1), Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS, Federal Statistical Office). https://www-genesis.destatis.de/

- De Vroome, T. and van Tubergen, F. (2010) ‘The employment experience of refugees in the Netherlands’, International Migration Review 44(2): 376–403. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2010.00810.x.

- Dumont, J.-C., Liebig, T., Peschner, J., Tanay, F. and Xenogiani, T. (2016) How are refugees faring on the labour market in Europe? A first evaluation based on the 2014 EU Labour Force Survey ad hoc module (1/2016). doi:10.2767/350756.

- Dustmann, C. and Fabbri, F. (2003) ‘Language proficiency and labour market performance of immigrants in the UK’, The Economic Journal 113(489): 695–717. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.t01-1-00151.

- Dustmann, C., Fasani, F., Frattini, T., Minale, L. and Schönberg, U. (2017) ‘On the economics and politics of refugee migration’, Economic Policy 32(91): 497–550. doi:10.1093/epolic/eix008.

- Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P. and Åslund, O. (2003) ‘Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants--evidence from a natural Experiment’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(1): 329–357. doi:10.1162/00335530360535225.

- Elfering, M. and Zacharakis, Z. (2015, October 21) ‘Was kostet die integration?’, Zeit Online, 2–3. https://www.zeit.de/wirtschaft/2015-10/kosten-integration-sprackhkurse-fluechtlinge?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

- Entorf, H. and Lange, M. (2019) ‘Refugees welcome? Understanding the regional heterogeneity of anti-foreigner hate crimes in Germany’, SSRN Electronic Journal 2(19), doi:10.2139/ssrn.3343191.

- Eurostat (2020) Asylum seekers and first-time asylum seekers by citizenship, age and sex. Annual aggregated data (rounded), Eurostat. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database?node_code=migr

- Fasani, F., Frattini, T. and Minale, L. (2021) ‘(The struggle for) refugee integration into the labour market: evidence from Europe’, Journal of Economic Geography 22(2): 351–393. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbab011.

- Fossati, F. and Liechti, F. (2020) ‘Integrating refugees through active labour market policy: A comparative survey experiment’, Journal of European Social Policy 30(5): 601–615. doi:10.1177/0958928720951112.

- Gehrsitz, M. and Ungerer, M. (2018) Jobs, crime, and votes: A short- run evaluation of the refugee crisis in Germany. In ZEW Discussion Papers (No. 16–086).

- Geis, W. and Orth, A. K. (2016) Flüchtlinge regional besser verteilen. Ausgangslage und Ansatzpunkte für einen neuen Verteilungsmechanismus.

- Getmansky, A., Matakos, K. and Sinmazde, T. (2020) Diversity without adversity? Refugees’ efforts to integrate can partially offset identity-based biases. ESOC Working Paper, 16. http://esoc.princeton.edu/wp16

- Godøy, A. (2017) ‘Local labor markets and earnings of refugee immigrants’, Empirical Economics 52(1): 31–58. doi:10.1007/s00181-016-1067-7.

- Goodman, S. W. and Wright, M. (2015) ‘Does mandatory integration matter? effects of civic requirements on immigrant socio-economic and Political Outcomes’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41(12): 1885–1908. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1042434.

- Grote, J. (2018) The Changing influx of asylum seekers in 2014–2016: Responses in Germany. Focussed study by the German national contact point for the European Migration Network (EMN). Working Paper 79. Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF).

- Gupta, S. (2011) ‘Intention-to-treat concept: A review’, Perspectives in Clinical Research 2(3): 109. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.83221.

- Hanhörster, H. and Wessendorf, S. (2020) ‘The role of arrival areas for migrant integration and resource access’, Urban Planning 5(3): 1–10. doi:10.17645/up.v5i3.2891.

- Hartshorne, J. K., Tenenbaum, J. B. and Pinker, S. (2018) ‘A critical period for second language acquisition: evidence from 2/3 million English speakers’, Cognition 177: 263–277. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.007.

- Hayes, A. F. (2022) Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach (Third Edit), The Guilford Press.

- Hoehne, J. and Michalowski, I. (2016) ‘Long-term effects of language course timing on language acquisition and social contacts: Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in Western Europe’, International Migration Review 50(1): 133–162. doi:10.1111/imre.12130.

- Huber, M. (2016) ‘Disentangling policy effects into causal channels’, IZA World of Labor, doi:10.15185/izawol.259.

- IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (2021) IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees 2019, data 2016-2019. doi:10.5684/soep.iab-bamf-soep-mig.2019.

- Kaida, L. (2013) ‘Do host country education and language training help recent immigrants exit poverty?’, Social Science Research 42(3): 726–741. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.01.004.

- Kanas, A., Chiswick, B. R., van der Lippe, T. and van Tubergen, F. (2012) ‘Social contacts and the economic performance of immigrants: A Panel study of immigrants in Germany’, International Migration Review 46(3): 680–709. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2012.00901.x.

- Kanas, A. and Steinmetz, S. (2021) ‘Economic outcomes of immigrants with different migration motives: The role of labour market Policies’, European Sociological Review 37(3): 449–464. doi:10.1093/esr/jcaa058.

- Kanas, A. and van Tubergen, F. (2009) ‘The impact of origin and host country schooling on the economic performance of Immigrants’, Social Forces 88(2): 893–915. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0269.

- Khalil, S., Kohler, U. and Tjaden, J. (2022) ‘Is there a rural penalty in language acquisition? evidence from Germany’s refugee allocation Policy’, Frontiers in Sociology 7(June), doi:10.3389/fsoc.2022.841775.

- Koopmans, R. (2010) ‘Trade-Offs between equality and difference: immigrant integration, multiculturalism and the welfare state in cross-national perspective’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36(1): 1–26. doi:10.1080/13691830903250881.

- Kosyakova, Y. and Brenzel, H. (2020) ‘The role of length of asylum procedure and legal status in the labour market integration of refugees in Germany’, Soziale Welt 71(1–2): 123–159. doi:10.5771/0038-6073-2020-1-2-123.

- Kosyakova, Y. and Brücker, H. (2020) ‘Seeking asylum in Germany: Do human and social capital determine the outcome of asylum procedures?’, European Sociological Review 36(5): 663–683. doi:10.1093/esr/jcaa013.

- Kosyakova, Y., Kristen, C. and Spörlein, C. (2022) ‘The dynamics of recent refugees’ language acquisition: how do their pathways compare to those of other new immigrants?’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48(5): 989–1012. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1988845.

- Kristiansen, M. H., Maas, I., Boschman, S. and Vrooman, J. C. (2021) ‘Refugees’ transition from welfare to work: A quasi-experimental approach of the impact of the neighbourhood Context’, European Sociological Review, 234–251. doi:10.1093/esr/jcab044.