ABSTRACT

According to UNHRC, approximately 5 million refugees fled Ukraine between the 24th of February and the 17th of April 2022. Governments and civil societies all over Europe face a major task of mobilizing resources to address the refugees' welfare needs. This effort is partly dependent upon the mobilization of informal civil society. In this research note, we present preliminary findings on the online mobilization of informal civic action pertaining to informal groups' temporal, geographical, and practical dimensions. Furthermore, we outline simple procedures for obtaining data on online-organized volunteering, aiming to enhance other civil society researchers' access to studying the phenomenon.

1. Introduction

According to the UNHRC, approximately 5 million refugees fled Ukraine between the 24th of February and the 17th of April 2022.Footnote1 Governments and civil societies all over Europe stand before a major task of mobilizing resources. 26,432 Ukrainian refugees are as of 9 November 2022 registered in Denmark,Footnote2 a substantial number of refugees in a country of c. 6 mio. inhbitants, and in many other European countries the numbers are substantially higher.Footnote3 Thus, receiving and hosting the Ukrainian refugees is a major task to be dealt with for the receiving countries in the region. However, in stark contrast to the generally hesitant attitude towards recent groups of refugees like the Syrians in 2015 (Siim and Meret 2019; Della Porta 2018; Lahusen and Grasso 2018), European governments have committed their countries to helping the Ukrainian refugees. In many cases, including Denmark, legislatures have passed emergency legislation endowing the Ukrainian refugees with far better conditions and rights than other groups of refugees.Footnote4 Similarly, this refugee solidarity mobilization, unlike the Syrian case, seems to have attracted citizens from all over the political spectrum (Carlsen and Toubøl Citation2023). Despite the mobilization of massive resources to provide for the Ukrainians' welfare, the state institutions cannot provide all necessary help as speedily as required, and politicians have called upon the informal civil society to help.Footnote5 This research note presents early findings on civil society's response in the form of large-scale mobilization of informal voluntary support for Ukraine predominantly organized on social media.Footnote6

This research note has a dual aim. (1) We call attention to three research topics highly salient to the new phenomenon of large-scale online mobilization of civic collective action and thus for researchers in the fields of civil society, social movements studies, and volunteering. (2) We outline simple procedures for obtaining data on online-organized volunteering, aiming to enhance access by researchers in the field who are studying the phenomenon empirically.

We highlight and present initial findings on the following three central aspects of mobilizations of informal online volunteering: (1) the temporal dimension concerning responsiveness of civil society, (2) the spatial dimension of the mobilization concerning geographical coverage, and (3) the practical dimension concerning repertoires of support tasks and their coordination. In relation to the temporal dimensions, it has been argued that informal civil society's role in the wider societal crisis response is characterized by its ability to mobilize instantaneously and almost instantaneously provide help to those in need (Albris Citation2018; Miao et al. Citation2021; Carlsen and Toubøl Citation2022a). Related to the spatial dimension, in the current situation, Ukrainian refugees are being placed in all regions of Denmark, and geographical coverage of local voluntary groups is vital. In the Syrian refugee crisis, local groups were key in supporting local integration and a broad set of support tasks (Carlsen and Toubøl Citation2022b). Related to the practical dimension (Blee Citation2012), Ukrainian refugees have a diverse set of needs that are continually changing in different phases of their refuge. Hence, a central coordination problem for informal civil society groups is to supply what is needed and negotiate what tasks should be handled by informal civil and what tasks formal welfare providers are better suited to address. The description of the temporal, geographical, and practice patterns aims to provide an initial mapping of the dynamics of Denmark's informal civil society efforts, providing vital descriptive knowledge of the mobilization as a foundation on which future analytical efforts can build.

2. Methods and data

We exploit the fact that informal Danish civil society, to a substantial extent, uses Facebook groups to mobilize help, which was the case during the refugee crisis in 2015 (Carlsen et al. Citation2021b) and the covid crisis (Bertogg and Koos Citation2021; Borbáth et al. Citation2021; Carlsen et al. Citation2021a). Data from 2018 shows that 70 percent of the Danish population between 16–89 use Facebook (Tassy et al. 2018). The extensive use of FB in Denmark and especially in Danish civil society makes Facebook the most important platform to map the temporal, geographical and practical patterns of the mobilization. From our initial scouting of different types of Facebook groups we found that most of the activity was happening within newly groups specifically targeted Ukrainian refugees and not more general refugee solidarity groups such as the Friendly People. Therefore, we concentrate on Ukrainian refugee solidarity groups in this analysis.

details our procedure for locating what we believe is a close to exhaustive group search and sampling strategy that other researchers can employ. The procedure consists of 4 steps summarized in . The first step is to locate as many Ukrainian refugee support groups as possible through different search operations. We made both general searches(‘Ukraine’ and ‘help’) and locational searches where we searched for a location(all names connected to a postal code) and ‘Ukraine’. The central quality criteria in this step is high recall, meaning our search returns as many of the actual groups as possible while tolerating that the search query returns many irrelevant groups, that is, low precision. The second step aims to enhance quality by improving the precision by selecting only the groups that fall within the sample frame, in our case, Danish Ukrainian support groups, from the returned search query. Steps 3 and 4 collect and code the group metadata to produce a dataset of group location, membership count, purpose, and rules.

Table 1. Procedure for group sampling and basic description.

Using the variables retrieved, we then chose 3 of the more prominent groups responsible for most of the activity and the largest membership base to analyse the groups' practical dimension. This qualitative inspection focused on the practical support tasks coordinated, how they were coordinated, and the moral concerns articulated within the groups. Results reported in this analysis stem from ongoing qualitative reading of most the post in the the selected groups, focusing on the post that where about coordinating activity.

The simple research procedure detailed in can easily be adjusted to other regions and languages. In the cases where the language is used in more than one region, the geographical search terms are important for delimiting the search. The data on Facebook groups provides a resource for doing comparative research on crisis mobilization in informal civil society pertaining to both the responsiveness, geography, and size of the mobilization and the framing, rules and practices guiding volunteering within each region. Naturally, any comparison between regions has to consider Facebook as a specific medium for mobilizing. Facebook is likely not representative of the larger population or the active informal civil society. Yet, it might be a fair comparison in some cases, and it provides an accessible sampling framing across different regions of informal civil society, something informal civil society typically lacks (Carlsen et al. Citation2021b).

3. The temporal and geographical distribution: responsiveness and coverage

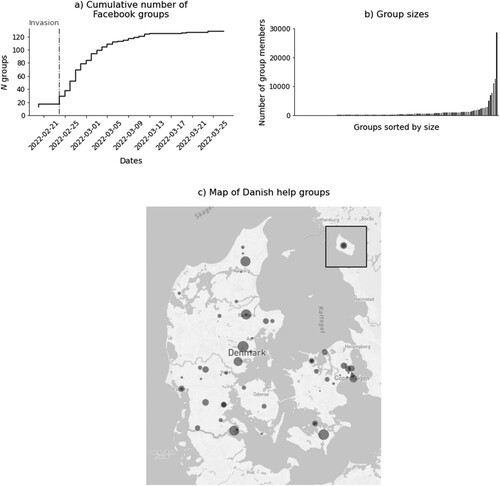

As is evident from (a), a massive mobilization of informal groups was formed on Facebook in the wake of the crisis. Most of these were support groups aimed at providing direct humanitarian relief aid, while a few provided fora for articulating solidarity with the Ukrainians and sharing information about the unfolding of events. A number of groups existed beforehand. Some of these were groups for Ukrainians already in Denmark, and others were groups formed in the wake of the Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014. Some veteran groups were very important for early mobilization as the central hub for much activity and recruitment. Similar to what has been found regarding the Syrian refugee crisis and the covid crisis, we see a highly responsive informal civil society (Miao et al. Citation2021; Bertogg and Koos Citation2021; Borbáth et al. Citation2021; Carlsen et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b). The groups' total membership counts 135,254, including cases of multiple group membership. Thus the number of individual members is likely to be significantly lower, but the available data do not allow us to tally members, only memberships. Furthermore, the membership of a Facebook group should not be seen as indicating active participation. Many members of Facebook groups join the groups yet do not partake actively in the coordination of support. As (b) shows, the distribution is heavy-tailed, with the first five groups accounting for almost 50 per cent of the total memberships.

Figure 1. Mobilization of Ukraine refugee solidarity groups on Facebook.

Notes: (a) Chart of the cumulative temporal appearance of relevant Facebook groups in 2022. The date of the Invasion of Ukraine, which started on the 24th of February 2022, has been marked by the dropline. (b) Chart of the group sizes sorted from smallest to largest groups. (c) Map of the positions of the 60 local groups. The size of the circle indicates the number of members in the group.

(c) maps the 60 local groups. The size of the node indicates the group's membership count. A first observation is that despite the recency of the Ukrainian refugee crisis, all regions of Denmark are already covered except the western part of central Jutland. We expect this to reflect alternative modes of organizing rather than no organization at all, also observed during the covid crisis (Carlsen et al. Citation2021b). Our preliminary investigation of this anomaly suggests that existing local and church-based groups organize the help. This aligns with rural western Jutland being the region with the most Ukrainians before the warFootnote7 who therefore are likely to be represented in civil society resulting in local general-purpose groups becoming the site for organizing Ukrainian refugee solidarity. At the same time, the region is the stronghold of the pietist Christian sects in Denmark which maintain an extensive network of organizations and institutions including refugee solidarity activities.

In some regions, there are multiple groups with different functions. One example is the island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea, where one group coordinates transport to Bornholm and another group facilitates the support of refugees on Bornholm. When the government plans to distribute Ukrainian refugees throughout Denmark, we expect more social media support groups to emerge and increased activity.

4. The practical dimension: collective action repertoires and coordination of participation

A central concern when analyzing social media activism is the extent to which these groups undertake any social support (Earl and Kimport Citation2011) and what repertoire of action the activities cover (Tilly Citation2006). Our qualitative inspection of the groups strongly suggests that a substantial amount of support is facilitated and coordinated through these groups and reveals a clear temporal pattern of adaptation of the kinds of help supplied. As the crisis unfolds, the needs and opportunities to help change. The dynamics of the crisis require a high level of adaption as well as coordination on the part of the informally organized online groups of volunteers if they are to succeed in providing the help necessary at different points in the timeline of the flow of refugees (Dynes Citation1970; McAdam et al. Citation2001). Below we unfold these patterns of crisis dynamics and adaptation of the voluntary relief efforts. We focus on the transformations of the collective action repertoires of different sets of activities intended to support the Ukrainian refugees and how these are embedded in the ongoing meaning-making reinterpretations of the situation among the volunteers central to their coordination efforts (Tilly Citation2008; Lichterman and Eliasoph Citation2014).

At the beginning of the crisis, the groups were concerned with organizing a diverse set of collections and distributing donations of money and stuff intended for civilians inside Ukraine and the first refugees arriving at the borders of Poland and Slovakia. As more Ukrainians crossed the borders into Ukraine's neighbouring countries, volunteers began driving cars and buses to the border and transporting Ukrainians to Denmark. Related to this activity, a key function of the groups was to give advice on the practicalities involved in such endeavours and facilitate contact with individuals in need of help at the border and local organizations. Ukrainians already residing in or affiliated with Denmark were instrumental in many of the groups, both in terms of organizing and facilitating contacts. Volunteers with Russian and Ukrainian language skills also acted as translators. With more refugees arriving in Denmark, sheltering (refugees living in the private homes of Danish volunteers) becomes a central mode of support in the groups. Some groups have specialized in giving shelter, where Danish residents put themselves on a list or react to requests for shelter. A small group of people also coordinated their voluntary participation in the military efforts against the Russian invasion.

The repertoire being almost purely non-contentious is in stark contrast to the mobilization in solidarity with Syrian refugee in 2015. Here, the public and political contention over Denmark's responsibility towards the Syrian refugees and much a more restrictive immigration policy widespread sparked protests and civil disobedience in addition to non-contentious voluntary support, in Denmark and across Europe (Siim and Meret 2019, 2021; Lahusen and Grasso 2018; della Porta 2018; Gundelach and Toubøl 2019; Carlsen et al. Citation2021b; Carlsen and Toubøl Citation2022b).

What to do and how to do it was a central coordination issue in the groups. Some kinds of support were quickly criticized for being obsolete, like clothes donations accused of obstructing border crossings and making it difficult for organizations like the Red Cross to run their operations inside Ukraine. Others developed guidelines and conventions for how to help successfully. One prominent example concerned transport, where activists told one another that they needed to be in contact with an organization or individual for the transport to be successful and that they should bring a woman to increase the trustworthiness and a translator to support communication. Discussion also revolved around the extensive use of private sheltering. The groups discussed the responsibility of the host, what tasks should be assisted with, and how big a commitment it entailed. The host tends to support many different support tasks, including the emotional, economic, and bureaucratic, which–taken together–demand both extensive resources and expertise.

One of the main functions of the Facebook groups is to provide a forum where people can seek or offer help. In some cases, a contact person mediates the help between a Danish resident and a Ukrainian refugee, and in some cases, the request comes directly from a Ukrainian refugee. In the beginning, much of the activity was mediated, and here, regional NGOs in or close to Ukraine were used to guide the humanitarian efforts. As more Ukrainian refugees arrived in Denmark, they, to a greater extent, asked for help directly in the groups, and likewise, more information was directed at Ukrainian refugees; hence, the language in some groups shifted from exclusively Danish to including Danish, English, and Ukrainian. To translate from one language to another, online translation tools is typically used. On several occasions, however, misunderstandings arose from mistakes in the translations provided by these tools. This indicates that the transformation from a predominantly Danish language to a multilingual setting may challenge the group's social cohesion and inclusiveness due to lower efficacy due to translation-caused misunderstandings, which might also generate conflict. Language skills may be a barrier to participation, and digital literacy is needed to navigate and correctly use online translation tools, including being knowledgeable about their shortcomings (Schradie Citation2018).

Thus, one central question regarding the Facebook groups is whether they will continue to be a place where ties between Ukrainian refugees and Danish residents can be formed and hence be an arena for forming social capital and trust networks (Tilly Citation2007). Here, the volunteers face dilemmas similar to those identified in the Syrian refugee crisis concerning developing solidarity and navigating the dilemmas of volunteering related to the inequality between local volunteers and refugees' in need of support (Siim and Meret 2019, 2021; Carlsen and Toubøl Citation2022a, Citation2022b).

5. Future research questions and perspectives

In this research note, we have mapped the temporal, geographical, and participatory patterns of the ongoing Danish mobilization of solidarity with Ukrainian refugees occurring in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Motivated by theoretical and practical concerns, we have demonstrated that the online mobilization has been highly responsive: The mobilization followed swiftly after the outbreak of war; local groups cover almost all parts of Denmark, and they offer varying support tasks aiming to match the practical requirement of the unfolding crisis. We have proposed a simple procedure for locating and sampling informal refugee solidarity groups on Facebook. Our preliminary findings and data collection point to three fruitful and related areas of research: (1) diffusion and survival of support groups, (2) the development of the repertoire of participation and support, and lastly, (3) comparative work focusing on differences and similarities in informal online organization between different European societies in the wake of the Ukrainian refugee crisis. The latter perspective we touched upon above, and therefore, we will address only the former two here.

The diffusion and survival of support groups are important research questions for the study of informal civil society (Fine and Harrington Citation2004; Blee Citation2012) and important for local communities' challenges of supporting the welfare and integration of the Ukrainian refugees. Using our temporal and geographical group data and regional data on the population characteristics and the number of Ukrainian refugees in the region, we can start to investigate compositional factors that influence the emergence and survival of local support groups. Furthermore, we can supplement these compositional explanations with interactional explanations that focus on ongoing communication within the support groups and their ability to produce positive ties between members and facilitate support. The analysis of interaction would also allow for the analysis of within and between group conflict and how this influences participation.

A second research agenda concerns the dynamic of crisis development of the repertoire of collective action (Dynes Citation1970; Tilly Citation2006). This question is central to much social movement research (McAdam et al. Citation2001) but also within the literature on voluntary social support, in particular in its more dynamic forms such as disaster relief work (Dynes Citation1970; Albris Citation2018; Michel Citation2007) and informal, online-facilitated volunteering (Eimhjellen Citation2019; Bertogg and Koos Citation2021; Carlsen et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b). An important first question is whether the supply of social support matches the demand and what social dynamics explain the potential mismatch. Exploiting the fact that Ukrainian refugees are active in the groups, we can investigate whether there is a mismatch between the volunteers' issue definition and the problems experienced by the refugees. Another central question is the extent to which the activists start to supplement their humanitarian engagement with contentious activism. Given that the state is supporting refugee solidarity action relative to the Ukrainian refugee crisis, this might seem unlikely. Yet, the asylum system itself is still very much a product of years of political hostility towards refugees, and its lack of capacity and resources might lead the movement to develop contentious collective action to improve the condition of refugees in Denmark. A further question is how the groups respond when the states starts to offer various forms of welfare to Ukrainians refugees. Do they change their functions away from providing social welfare, work as an alternative support channel or adjust the services that they provide to supplement the welfare services of the state.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hjalmar Bang Carlsen

Hjalmar Bang Carlsen is an assistant professor at Department of Sociology, Lund University and SODAS, University of Copenhagen. His research interests are digital mixed methods research, computational texts analysis, civil society, social movements and volunteering.

Tobias Gårdhus

Tobias Gårdhus is a masters student of Sociology at University of Copenhagen. His research interests are social media research, natural language processing, network analysis and political attention.

Jonas Toubøl

Jonas Toubøl is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology, University of Copenhagen. His research interests are civil society, social movements, volunteering, collective action and mixed methods.

Notes

1 https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine visited 2022-05-16

3 https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine, visited 2022-11-28

4 https://uim.dk/nyhedsarkiv/2022/marts/bred-aftale-om-lovgivning-til-fordrevne-fra-ukraine/ visited 2022-04-12.

5 https://policywatch.dk/nyheder/christiansborg/article13864241.ece visited 2022-04-12

6 We do not analyze formal civil society including NGOs and volunteering facilitated by private companies, churches, and state institutions.

References

- Albris, K. (2018) ‘The switchboard mechanism: how social media connected citizens during the 2013 floods in dresden’, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 26(3): 350–357.

- Bertogg, A. and Koos, S. (2021) ‘Socio-economic position and local solidarity in times of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of informal helping arrangements in Germany’, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 74: 100612.

- Blee, K. M. (2012), Democracy in the Making: How Activist Groups Form. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Borbáth, E., Hunger, S., Hutter, S. and Oana, I.-E. (2021) ‘Civic and political engagement during the multifaceted COVID-19 crisis’, Swiss Political Science Review 27(2): 311–324.

- Carlsen, H. B. and Toubøl, J. (2022a), ‘Solidarity and volunteering in the COVID-19 Pandemic’, in D. A. Snow, D. Della Porta, and D. McAdam (eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Carlsen, H. B. and Toubøl, J. (2022b), ‘The refugee solidarity movement between humanitarian support and political protest’, in D. A. Snow, D. Della Porta, and D. McAdam (eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Carlsen, H. B. and Toubøl, J. (2023), ‘Some refugees welcome? Frame disputes between micro-cohorts in the refugee solidarity movement’, Preprint.

- Carlsen, H. B., Toubøl, J. and Brincker, B. (2021a) ‘On solidarity and volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis in Denmark: the impact of social networks and social media groups on the distribution of support’, European Societies 23(1): 122–140.

- Carlsen, H. B., Toubøl, J. and Ralund, S. (2021b) ‘Consequences of group style for differential participation’, Social Forces 99(3): 1233–1273.

- Dynes, R. R. (1970) ‘Organizational involvement and changes in community structure in disaster’, American Behavioral Scientist 13(3): 430–439.

- Earl, J. and Kimport, K. (2011), Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Eimhjellen, I. (2019), ‘New forms of civic engagement. Implications of social media on civic engagement and organization in scandinavia’, in L. S. Henriksen, K. Strømsnes, and L. Svedberg (eds.), Civic Engagement in Scandinavia: Volunteering, Informal Help and Giving in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 135–152.

- Fine, G. A. and Harrington, B. (2004) ‘Tiny publics: small groups and civil society’, Sociological Theory22(3): 341–356.

- Lichterman, P. and Eliasoph, N. (2014) ‘Civic action’, American Journal of Sociology 120(3): 798–863.

- McAdam, D., Tarrow, S. G. and Tilly, C. (2001), Dynamics of Contention, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Miao, Q., Schwarz, S. and Schwarz, G. (2021) ‘Responding to COVID-19: community volunteerism and coproduction in China’, World Development 137: 105128.

- Michel, L. M. (2007) ‘Personal responsibility and volunteering after a natural disaster: the case of hurricane katrina’, Sociological Spectrum 27(6): 633–652.

- Schradie, J. (2018) ‘The digital activism gap: how class and costs shape online collective action’, Social Problems 65(1): 51–74.

- Tilly, C. (2006), Regimes and Repertoires, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Tilly, C. (2007) ‘Trust networks in transnational migration’, Sociological Forum 22(1): 3–24.

- Tilly, C. (2008), Contentious Performances, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.