ABSTRACT

An important question in understanding the war in Ukraine is whether Russian President Putin’s claim that Russians and Ukrainians are ‘one people’ or whether the statement made by European Union Commission President von der Leyen, echoing Ukrainian government’s position, that Ukraine is ‘one of us’ receives more support. In our contribution, we assess the societal values endorsed in Ukraine, and test whether they resemble those of Russia or Western Europe. After reviewing arguments brought by the ‘Clash of Civilizations’, Modernization, Social Identity, and Nation Building theories, we analyze the most recent data from the European Values Study and World Values Survey (2017-2021). Constructing an EU-values index, including gender equality, individual freedom, and liberal democracy, among others, we show that while values in Ukraine are closer to Russia than virtually any European Union country, there are clear differences that are especially salient among younger age cohorts. Further, we refute Huntington’s claim that Ukraine is a ‘cleft’ country by showing that regional variation within Ukraine is rather minimal. We conclude with an interpretation of these findings in light of political debates and prominent theoretical approaches to studying values.

Introduction

While Russian President Vladimir Putin might have considered several arguments to start a war against Ukraine, including the expansion of NATO to the East (see Bilefsky et al. Citation2022), it is undeniable that a grand vision of a greater Russia of people sharing the same values was one of them. At the, by-now famous, speech on February 21, 2022 – three days before the invasion – he proclaimed: ‘I would like to emphasize again that Ukraine is not just a neighboring country for us. It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture, and spiritual space. These are our comrades, those dearest to us – not only colleagues, friends, and people who once served together, but also relatives, people bound by blood, by family ties’ (Putin Citation2022). This argument known in the literature as ‘primordialism’ (cf. Smith Citation1998) regards the boundaries of the nation-state as coinciding with historical ethnic identities. For Putin, Ukraine and Russia are one and undivided, and the borders of the Ukrainian state are artificially separating historical blood ties.

Ukraine’s neighboring countries and more generally the European Union (EU) reacted with agitation, not only against the war, but also to this radical position in favor of pursuing some perceived primordial justice, even if in violation of contemporary international law. On 27 February 2022, three days after the invasion, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen declared in an interview that Ukraine is ‘one of us and we want them in the European Union’ (Euronews Citation2022). With stronger stress on common values, she reiterated this position in the Commission’s opinions on the EU membership applications by Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia on June 17, 2022, when she argued (von der Leyen Citation2022): ‘Ukraine has clearly demonstrated the country's aspiration and the country's determination to live up to European values and standards.’ In a constructivist position (cf. Anderson Citation1983), the boundaries of the European Union are permeable and open to countries willing to subscribe to the norms and values of Europe.

Evidently, Ukraine is not just an object in the big geopolitical players’ game but also an actor in its own right. A pivotal moment in Ukraine’s geopolitical orientation was the Maidan Revolution in 2014, ignited by the refusal of Ukrainian pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovich to sign the association agreement with the EU and instead attempted to tie the country’s future with Russia. On March 2014, interim Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk proclaimed that ‘[b]y signing this agreement [for association with the EU], we will demonstrate to the world that we are together, that Ukraine shares European values’ (Yatsenyuk Citation2014). Ukraine’s Western aspirations were further reinvigorated by the violation of its territorial integrity by Russia with the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the support for the pro-Russian separatists in the Donbas region, and especially after the full-scale invasion in February 2022 (Minesashvili Citation2022). In his address to the US Congress, President Zelenskyy (Citation2022) reaffirmed Ukraine’s outlook on Europe by stating that ‘Today, the Ukrainian people are defending not only Ukraine. We are defending the values of Europe.’

These competing narratives on values – by Putin and his vision for a united ‘Russian world’ (Suslov Citation2018) on one hand and Western and Ukrainian political elites on the other – are difficult to reconcile (Feklyunina Citation2016); both argue that Ukrainian values are leaning towards contested spheres of influence, the Slavic-Orthodox and the Western, respectively. Although these statements are to an extent political rhetoric that is instrumental to achieving certain higher-order goals, we find it of value to assess their validity not only in an effort to place political discourse on firmer empirical foundations but also to assess several prominent value theories. Comparative politics proposes that Ukraine is a particularly interesting case in the study of the ‘Clash of Civilizations’-thesis due to its unique historical entanglements (cf. Huntington Citation1993, Citation1996). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine has been ‘trapped’ in the ‘grey zone’ between ‘East’ and ‘West’, between two competing worldviews for societal development offered by the West, embodied in EU and NATO membership, and Russia and its Eurasian Union, aiming to reintegrate the post-Soviet space (Güneyli̇oğlu Citation2022; Noutcheva Citation2018; Riabchuk Citation2007; Wawrzonek Citation2014). Scholars studying Ukraine also debate the extent to which Ukraine is divided along the fault lines proposed by Huntington (cf. Riabchuk Citation2003, Kulyk Citation2011), or whether this divide is overstated (cf. Zhurzhenko Citation2002; Kuzyk Citation2019). This warrants a detailed exploration of the relative position of Ukraine between Russian and Western European values, its internal divisions, and if there are tendencies that suggest Ukraine’s move towards Western values.

We put the competing narratives to the test by taking as a point of departure the EU-values scale developed by Akaliyski et al. (Citation2022). This scale encompasses values such as gender equality, individual freedom, tolerance, and liberal democracy, as written down in the Treaty of the European Union (Citation2012).Footnote1 The analysis relies on data obtained from the European Values Study (EVS) and World Values Survey (WVS), cross-national research projects that are ultimately suited for the analysis of this research question, given that the core of the EVS (which still resonates in the items under investigation) was designed to study whether European political integration fosters European cultural integration (see Luijkx et al. Citation2022).

We proceed as follows: In the second section of this paper, we present the four theoretical models in greater detail. In the third section, we introduce the data and methods, particularly focusing on the EU-values scale. The results of our analyses are displayed in the fourth section of this article. We show that while Ukrainian values are leaning more towards Russia than Western Europe, there are also tendencies that show a slow shift towards EU-values, especially among the younger generation.Importantly, the regional variation, often discussed in the literature (cf. Huntington Citation1993, Citation1996; Riabchuk Citation2015; Katchanovski Citation2006a, Citation2016), is scarcely evident in our values study. We discuss our findings in light of ongoing debates on the current war, as well as broader reflections on values research.

Theoretical framework

To theorize the extent to which Ukraine resembles European or Russian values, we draw from four theoretical perspectives, namely the ‘Clash of Civilizations’-thesis; Social Identity Theory and insights from value diffusion; Modernization and Human Development theories; and lastly Nation Building theories.

First, the ‘Clash of Civilizations’-thesis was coined by Samuel Huntington (Citation1993, Citation1996) after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Its main idea is that the new lines of global geopolitical contestation will no longer be ideological as during the Cold War, but rather cultural – between several large civilizations based on historical-cultural commonalities and shared identity. Huntington divides the world into several civilizations, such as the Western civilization, the Slavic-Orthodox civilization, the Muslim world, to name but a few. The transcontinental Western civilization, encompassing Western Europe and the former British colonies in North America and Australia, and New Zealand, is based on the shared legacies of Western Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism), the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment philosophy. Void of these legacies, the Slavic-Orthodox civilization is supposedly rooted in Orthodox Christianity and the Slavic heritage common in the majority of these countries. At a first glance, by sharing both a common majority religion (Orthodoxy), closely related languages (the Eastern Slavic linguistic group), and a common communist history, Russia and Ukraine are supposedly the two largest core nations of the Slavic-Orthodox civilization. Such a view has been explicitly embodied in Putin’s vision of a multipolar world, of which the ‘Russian world’ emerges as a unique civilization rooted in its inherent cultural values (Linde Citation2016) and constituting an alternative to the Western model of modernity (Suslov Citation2018).

However, Huntington’s world of civilizations contains ambiguity, introduced by the terms ‘torn’ and ‘cleft’ countries. Torn countries are ‘indecisive’ in their civilizational belongingness; Russia, for instance, has historically shifted its identity from being an integral part of the West to being a civilization on its own, begging the question of what road Russia would take in the post-Cold war era: attempt to join the West or form its own civilization. By now, it has become apparent that Russia has turned decisively towards differentiation from the West (Linde Citation2016; Shcherbak Citation2022) and it has attempted to integrate its former sphere of influence, not least by engaging in culture wars with the West (Akaliyski and Welzel Citation2020; Edenborg Citation2018a).

Cleft countries, on the other hand, are split in their identity within their territory. Ukraine is given as a prime example of a cleft country as its Western territories have been historically more closely integrated with the West, having been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Habsburg Empire, and still, a share of the population belongs to Catholicism or Protestantism (Huntington Citation1996). In contrast, other parts of the country have been within the territory of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union for most of their history. This historical division has allegedly led to a contemporary cleavage, which is clearly visible in political divisions and distinct patterns of pro-Western and pro-Russian orientation (Barrington Citation2022; Katchanovski Citation2006b, Citation2014; Kulik Citation2011; Pop-Eleches and Robertson Citation2018).

Second, building on Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation2004), Akaliyski (Citation2019) and Akaliyski and Welzel (Citation2020) argue that the ‘Clash of Civilizations’-thesis may not simply represent static cultural divisions between world civilizations; instead, distinct civilizational identities and geopolitical orientations could continue to influence the trajectory of cultural change at present. This theoretical perspective is coupled with the idea that values can trickle down from geopolitical entities or diffuse across national borders (Akaliyski Citation2019; Deutsch and Welzel Citation2016), also supported by World Polity (Society) Theory (Dimaggio and Powell Citation1983; Meyer et al. Citation1997). According to Social Identity Theory, populations belonging to a specific in-group seek to distinguish themselves from out-groups in a positive way. Respectively, the EU, as a branch of the Western civilization, has attempted to build a shared identity based on Western values such as democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance, and gender equality (Akaliyski et al. Citation2022), which has led to an increasing support for these values among societies participating in the EU-integration (Akaliyski and Welzel Citation2020; Gerhards Citation2010). In contrast, nations that remained outside of this process have been less exposed to the normative pressures to comply with the EU’s cultural script. Moreover, some countries, like Russia, have challenged the moral authority of the West (Headley Citation2015) and attempted to build a distinct cultural identity which portrays traditional Orthodox family values as a shield against the ‘moral decay’ of the West (Edenborg Citation2018b, Citation2018a; Güneyli̇oğlu Citation2022). Respectively, Akaliyski and Welzel (Citation2020) found that countries not participating in the process of EU-integration, including Russia and Ukraine, have stagnated or even declined in support for emancipative values (e.g., individual freedoms and gender equality) since the early 1990s. Their societal level analysis, however, may have overlooked internal divisions within Ukraine and not taken into account more recent cultural dynamics. As numerous research has documented, Western Ukrainians have been traditionally holding a stronger (pro-) Western identity (see, e.g., Huntington Citation1996; Katchanovski Citation2014; Kulyk Citation2011; Pop-Eleches Citation2018), which may have facilitated the diffusion of Western values to this part of the population alone.

Third, in contrast to the ‘Clash of Civilizations’-thesis (Huntington, Citation1996), Modernization and Human Development theories regard cultural differences as a result of differences in socio-economic development (Inglehart Citation1997; Inglehart and Welzel Citation2005; Welzel Citation2013). The reason is that socio-economic development allows individuals to feel existentially secure and once survival is taken for granted, they shift value priorities towards expressing individual differences and supporting individual freedoms. Thus, more advanced industrial societies have become increasingly liberated from traditional moral norms, and embrace diversity in lifestyles, freedom in reproductive choices, and equality between genders and between individuals belonging to diverse cultural backgrounds. This change sped up, especially among the Western European and American post-WWII generations who enjoyed a period of prosperity and peace (Inglehart Citation1997). These same values of tolerance, individual freedom, and equality were respectively embodied into the EU integration project as its cultural foundations (Akaliyski et al. Citation2022).

People in the Soviet bloc, lagging behind economically from the West, followed this cultural transition at a significantly slower pace. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many of these societies went through challenging social, political, and economic transitions that decreased their population’s sense of existential security and thus reversed towards more traditional and survival values (Inglehart and Baker Citation2000). These economic differences persist until the present as evident from their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita at Purchasing Power Parity (constant 2017 USD) in 2021: $12,944 in Ukraine and $27,970 in Russia versus $44,024 on average for the EU (World Bank Citation2021). Of note is the substantial difference also between Ukraine and Russia, the GDP per capita of the latter being more than twice larger. This corresponds to differences in other developmental indicators such as the Human Development Index, on which Russia ranks 52nd, behind all EU countries aside from Bulgaria, while Ukraine comes in 74th position (United Nations Development Program Citation2019). Following the theoretical reasoning that socio-economic development is positively associated with support for EU-values (Akaliyski et al. Citation2022), we find further support for the expectation that both Russia and Ukraine are less supportive of EU-values than Western Europe.

The fourth and final perspective regarding the cultural differences between Ukraine and Russia comes from nation-building theories. The relevance of these theories for nations’ value homogenization and external differentiation has been explicated in the arguments in favor of ‘Nationology’, the field of social science devoted to comparing national cultures (Akaliyski et al. Citation2021). This view draws justification from diverse theoretical lenses to claim that nations as political entities (the whole population living within the territory of a state) constitute meaningful cultural units with a substantial degree of internal homogeneity and distinctiveness from other nations, despite not fully overlapping with nations as ethnic communities. This is because nation-states and their institutions exert a cultural gravitational force that socializes all members of a society to the predominant values within that society. The primary such institutions are the mass media, which has the capacity to diffuse cultural information to the whole population, and the educational system, which ensures the transmission of national values to the new generation (Inglehart and Baker Citation2000). From an evolutionary perspective too, national culture is likely to evolve over time as an adaptation to the natural, economic, and social environment of the specific nation-state (Schwartz Citation2006), thus diverging from other national cultures. From a functionalist perspective, national cultural homogeneity evolves as being advantageous as that increases intragroup loyalty and decreases transaction costs (Peterson et al. Citation2018).

Having been an integral part of the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union, one may assume a substantial degree of cultural similarity between Russia and Ukraine before 1991. The dissolution of the Soviet Union, however, supposedly created the conditions for a cultural differentiation between the two states. Three decades of independent existence might have been sufficient for the entire populations of the two countries to part from each other culturally even if we assume that they were identical before 1991. Since the new generation of Ukrainians and Russians have been socialized under new national educational systems, their values could be even more distinct than those of the older generations who have been educated under a common state ideology.

Indeed, studies from Ukraine have demonstrated an effective national-building process since the breakup of the Soviet Union. Ukraine’s internal identity division is argued to have decreased as support for pro-Russian orientation has been dwindling (Kulyk Citation2016, Citation2019; Minesashvili Citation2022) and the dividing line, to the extent it exists, has been shifting eastward (Kuzyk Citation2019). Ukraine has been moving away from an ethnic-based and towards a citizenship-based civic national identity in which language plays a diminishing role (Barrington Citation2022; Bureiko and Moga Citation2019; Onuch Citation2023), especially since the Russian aggression of 2014 (Kulyk Citation2016). In line with Darden and Mylonas’ (Citation2016) thesis, external threats by Russia strengthen governmental efforts to increase national cohesion through education and language policies. The strengthening of Ukraine’s national identity has been accelerated by a process of so-called cultural decolonization after independence, and especially since the Maidan Revolution (Fomenko Citation2022), including restrictions of Russian mass culture such as books, films, television etc. (Zhurzhenko Citation2021). State-controlled history education has also been employed in the nation-building efforts by emphasizing Ukraine’s position as a victim against an aggressive and oppressive Russia (Korostelina Citation2011, Citation2013). The symbolic breakup with the Soviet past has been demonstrated also by the so called ‘Leninopad’ (‘Lenin’s free fall’), which is a recent wave of demolitions of Soviet monuments in Ukraine (Rozenas and Vlasenko Citation2022). Therefore, these nation-building processes might have been successful in drifting Ukrainian culture from its Soviet past.

To summarize, we expect that Russia and Ukraine are substantially similar, yet distinct culturally. Simultaneously, the two countries would be markedly distant culturally from Western Europe. Following Huntington’s thesis (1993, 1996), we would expect to observe internal cultural divisions within Ukraine along West vs. East/South and religious (Catholic/Protestant vs. Orthodox) and linguistic (Ukrainian vs. Russian) lines. If we, instead, rely on Nationology’s propositions (Akaliyski et al. Citation2021), we would find a rather homogenous Ukrainian culture, distinct from that of Russia, especially among the younger generations.

Data and methods

Data

To achieve our research aims, we use data from the latest waves of the European Values Study (EVS) (EVS Citation2020) and the World Values Survey (WVS) (Haerpfer et al. Citation2020), both comprising nationally representative surveys with sample sizes of at least 1,000 respondents. In the rare cases where a country was surveyed by both EVS and WVS, we merged the two datasets to increase the robustness of our estimates. Fortunately, both Ukraine and Russia were among these countries surveyed twice. In the latest WVS wave, Ukraine was surveyed in July-August 2020, and Russia in November-December 2017, while in the EVS, Ukraine was surveyed in November 2020 and Russia in November-December 2017. Additionally, as points of comparison, we use data for 22 EU-member states, of which 11 are old member states (joined before 1996) and 11 were new member states (joined after 1996).Footnote2 For the analyses with all countries, we used equilibration weights (to a sample of 1,000), which account for small deviations of the samples compared to national census data.

Part of the analysis focuses exclusively on the Ukrainian data. The EVS contains data from 1,612 and the WVS from 1,289 respondents for a total of 2,901, which we analyzed together, including a study dummy variable in the regression analyses. All regions of Ukraine were surveyed aside from the territories not controlled by the Ukrainian government at that time, namely the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and substantial parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts (regions). Nevertheless, a large number of respondents were surveyed in the latter two regions as to represent their full populations.

Dependent variable

For EU-values, we use an index created by Akaliyski et al. (Citation2022), albeit with some modifications. This index is meant to represent the values the EU stands for and promotes in its internal and external affairs and which are explicitly enumerated in the Treaty of the European Union. Akaliyski et al.’s (Citation2022) original index is a societal level construct. However, because we also conduct individual-level analyses within Ukraine, we constructed these values at the individual-level as well, even if their internal coherence was somewhat weaker at that level (Cronbach’s alphas are reported in the description of the constructs below). The reason could be due to random measurement error at the individual level, which cancels each other out by aggregation, thus ‘purifying’ the constructs (Akaliyski et al. Citation2021) and increasing their interrelations. The values should in any case be regarded as an additive index rather than a latent construct because they are compiled based on a conceptual overlap with the values that are promoted by EU institutions.

The original index comprises seven domains, namely personal freedom, individual autonomy, social solidarity, ethnic tolerance, civic honesty, gender equality, and liberal democracy. We recreated each of them, aside from social solidarity, for which none of the items were available in the integrated WVS/EVS dataset. One item from the ethnic tolerance scale (‘accepting Muslims as neighbours’) was also unavailable in the survey and so we replaced it with two new items, one denoting whether employers should give priority to people of respondent’s nation than immigrants when jobs are scarce, and the second one evaluating the impact of immigrants on the development in the respondent’s country. This change led to an increase in the alpha compared to Akaliyski et al.’s scale (Citation2022) thus we regard it as an improvement. Additionally, as the individual autonomy scale showed poor internal validity, we replaced one of the items (‘important child qualities: imagination’) with two other items: ‘important in life: make parents proud’ (reversed) and ‘child’s duty to take care of ill parents’ (reversed). These items substantially increased the alpha, especially at the national level. The gender equality scale consisted of only one item in Akaliyski et al. (Citation2022), reportedly due to data limitations. To increase the scale’s reliability, we added three new items from the same thematic group, which measure attitudes towards gender equality in education, politics, and business. The EU-values index is the mean from all six comprising domains. All scores were recoded to vary between a theoretical minimum of 0 (no support for EU-values) and a maximum of 100 (full support for EU-values). The full list of items in each domain of EU-values and their respective alphas are presented below (in Italics are the newly added items):

Personal freedom (α (national) = . 91; α (individual) = .83):

o Justifiable: Homosexuality

o Justifiable: Abortion

o Justifiable: Divorce

Individual autonomy (α (national) = .73; α (individual) = .43):

o Important child qualities: Independence

o Importance child qualities: Obedience (reversed)

o Important in life: Make parents proud (reversed)

o Child’s duty to take care of ill parents (reversed)

Ethnic tolerance (α (national) = .93; α (individual) = .61):

o Accepting as neighbors: People of a different race

o Accepting as neighbors: Immigrants/foreign workers

o Jobs scarce: Employers should give priority to (nation) people than immigrants

o Evaluate the impact of immigrants on the development of [your country]

Civic honesty (α (national) = .98; α (individual) = .73):

o Justifiable: Claiming state benefits which you are not entitled to (reversed)

o Justifiable: Cheating on taxes (reversed)

o Justifiable: Someone accepting a bribe (reversed)

Gender equality (α (national) = .96; α (individual) = .80):

o When jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to a job than women (reversed)

o A university education is more important for a boy than for a girl (reversed)

o On the whole, men make better political leaders than women do (reversed)

o Men make better business executives than women do (reversed)

Liberal democracy (α (national) = .78; α (individual) = .56):

o Political system: Having a strong leader (reversed)

o Political system: Having the army rule (reversed)

o Political system: Having a democratic political system EU-Values Index (α (national) = .87; α (individual) = .65)

Socio-cultural divisions of Ukraine

To get a better understanding of value differences within Ukraine, thereby testing Huntington’s thesis of Ukraine as a so-called cleft country (1996), we consider various ways to split the Ukrainian population. As Huntington proposes the importance of religion, language and geography, we divided the population with regard to each of these characteristics, even if that reduces a far more complex reality into crude categories measurable with available data. These separate classifications are supposedly important, as Onuch and Hale (Citation2018) claim that personal language preference, language embeddedness, ethnolinguistic identity, and national identity matter independently in attitudinal outcomes.

Religion: The majority of Ukrainians are Orthodox Christians (61.27% of respondents), followed by those not belonging to any religion (24.35%). Of interest in this study are the Catholic (Greek and RomanFootnote3) and Protestant minorities (a total of 10.43% of the respondents), mostly concentrated in the West of the country. We grouped them together because Huntington’s argument is that they are both part of Western Christianity and additionally because there were too few Protestants to remain as a group on their own (n = 40, or appr. 1.5% of the sample). We grouped the remaining categories, including Jews, Muslims, Hindi, other Christian, and ‘other’, which comprised a total of 3.95%, as ‘Others’.

Language: The two major languages in Ukraine are Ukrainian and Russian; many people are bilingual but habitually speak one of them. Ideally, we would have preferred to use information about what language respondents speak at home but that question was not available in the integrated EVS/WVS dataset. Instead, we used an item denoting the language the interview was conducted in, assuming that all respondents had a choice between the two languages and the interview was conducted in the language the respondent felt most comfortable with. This produced an almost even split, with 54.36% of the respondents categorized as Ukrainian-speakers and 45.64% as Russian-speakers.

Geography: We split Ukraine into two approximately equal geographic regions based on historical and contemporary cleavages — West and East/South — for the most part using the Dnipro River as the separator as illustrated in Huntington (Citation1996) Footnote4 (see also Spodarets Citation2017). Dnipropetrovska Oblast is on both sides of the river, but a larger part is on the east side and 89% of the interviews were conducted in Russian so we denoted it as Eastern/Southern. Our geographic split also groups some southern regions, which are majority Russian-speaking, such as Odeska Oblast (70.1%), to East/South Ukraine. Kyivska Oblast (not Kyiv city) is also on both sides of the river, but a much larger part is on the West of the river and 83% of respondents were interviewed in Ukrainian, thus we allocated it to the Western region. Kyiv city is also split, but with a majority of Russian-speakers. Having a special status as a capital city, we decided to keep it as a region on its own. In our grouping, all regions in the West were majority Ukrainian-speaking. All regions in the East/South were majority Russian-speaking except Chernihivska, Sumska, and Poltavska, which are located entirely east of the Dnipro River, but the share of interviews conducted in Russian was between 25% and 44%. Overall, in the western regions, 96.3% of the interviews were conducted in Ukrainian, while in the East/South region, 79.4% were in Russian. In terms of religion, Orthodoxy is the majority religion in all regions (65.4% in West, 56.7% in East/South, and 64.7% in Kyiv). The non-religious group comes second with 11.5% in West, 36.6% in East/South, and 25% in Kyiv. Catholic/Protestants are more concentrated in the West (19.9%) compared to East/South (2.6%) and Kyiv (2.5%).

Additionally, we also split the Ukrainian population approximately in half based on the generation they belong to. The first group includes respondents who reached adulthood (age 18) by the time the Soviet Union collapsed (1991), comprising 51.36% of the sample. The second group are respondents who were still in socialization age (<18) at the time of the Soviet Union’s collapse (48.64%). We took the year 2019 as the approximate average for when the surveys were conducted, which is 28 years after the USSR’s collapse. Then we added 18 to that number so the sample was split into age ≤ 46 and age ≥ 47. This created generation groups of fairly similar size also for the rest of the countries in our comparison: Russia – 55.21% vs. 44.79%, New EU-members – 42.57% vs. 57.43%, and Old EU-members – 39.13% vs. 60.87%.

Independent variables

We use a number of predictors to explain the level of support for EU-values in Ukraine. First, as measures of cultural heritage, we use the same characteristics described in the section above, namely religion, language, and geographic region. We also employ several socio-demographic variables that are known from the literature as predictors of values. These included gender (male, female), age (continuous), education (lower, middle, and upper), income (standardized into deciles), settlement size (five categories), and employment status (eight categories). Additionally, we use a dummy variable for survey to account for any potential methodological differences between the EVS and WVS.

Empirical strategy

We divide our empirical investigation into four parts. First, we visualize the cultural distances between Russia, the geographic regions of Ukraine, and all EU-member states using multidimensional scaling (MDS) (Borg et al. Citation2013) to present an intuitive overview of the positioning of these cultural entities. This method uses information on all six domains of EU-values and reduces the dimensionality to fit the data in a way that best represents the distances between countries. In our case, we use a two-dimensional solution as the most easily interpretable and the most common choice for MDS. This procedure inevitably leads to a certain loss of precision which is indicated by the Stress value. A value lower than 0.10 can be considered a fair fit for the data. We used Akaliyski et al.’s (Citation2022) grouping of countries into culture zones based on their historical-religious background, namely Western Protestant, Western Catholic, Western Post-Communist (Catholic and Protestant), and Orthodox. We also plot the NUTS1 regions of Ukraine together with those of their neighbors, Russia and Poland, plus Germany as another reference point, with the intention to test whether they form distinct cultural clusters regardless of the historical overlap in the borders between these countries.

Then, we compare the strength of support for EU-values among the publics of Ukraine, Russia, and the EU-member states, which we divide into old and new members. We present Ukraine both as the entire population and also split the country into its three geographic regions, East/South, Kyiv, and West. Second, we look into the generational dynamics of support for EU-values by comparing Russia, Ukraine, and the old and new EU member states split into two groups: those socialized before the fall of the Soviet Union, and those after. In these parts, we do the analysis for the combined EU-values index and separately for each of the six domains.

Finally, using multiple linear regressions, we focus explicitly on Ukraine to identify the predictors of support for EU-values and with the intention to discern potential societal divisions along cultural heritage or socio-demographic lines. For parsimony, we focus on the combined EU-values index but we also present regressions with each of the six domains in the Appendix.

We used Stata 17 (StataCorp. Citation2021) for data analyses and created all figures in R (R Core Team Citation2022). R code, Stata syntax as well as additional data used were reposited at https://github.com/Akaliyski/Ukrainian_values.

Results

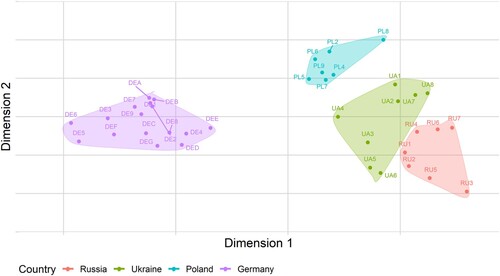

To present a general overview of the relative position of Ukrainian values compared to other relevant countries, we present the results of a Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) analysis in . All regions of Ukraine are very close to the Russian cultural center, although slightly in the direction of the Western European countries. Ukraine’s Western regions are further away from the EU’s values, compared to the Russian-speaking East/South and Kyiv, which contrasts with the claim in Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilizations’-thesis.

Figure 1. Multidimensional scaling analysis with EU countries, Russia and Ukraine split geographically, and grouping countries based on their culture zone, using data on all 6 value domains. Note. Modern MDS. Stress = 0.098, N = 26. The size of countries’ dots is weighted by the logarithm of their population size with data from World Bank (Citation2021). Ukraine’s total population was split into three regions based on the share of the respondents coming from each region.

All countries group strikingly well based on their historical-religious legacies, aside from Greece, which although majority Orthodox, according to Huntington, is a country that is torn between membership in the Western and Orthodox civilizations. Notably, even Cyprus, and Bulgaria and Romania, who have been EU-members for 19 and 16 years, respectively, cluster well with the other Orthodox countries that remained outside of the EU-integration process. This division shows some support for Huntington’s claims as we confirm that nations are indeed strongly related culturally by their historical-religious traditions, even though the West does not appear as a single monolithic culture, but instead as three separate ones.

Table A1 in the Appendix presents a correlation matrix between all domains of EU-values and the two dimensions emerging from the MDS plot, which can help with their interpretation. The horizontal dimension (D1) overlaps almost entirely with the EU-values index (r = .99) meaning that the more countries are positioned to the left, i.e., Protestant West, the more strongly they support EU-values. The vertical dimension (D2) is most strongly correlated with ethnic tolerance (negatively) and with individual autonomy (positively), meaning that central European countries like Czechia, Hungary, and Slovenia value autonomy more but are less in support of ethnic tolerance.

Next, presents the clustering of NUTS1 regions of Ukraine, and its largest neighbors from the East and West, Russia and Poland, plus Germany as a reference point. We find that even when we consider smaller-scale geographic regions the four countries form clearly distinct cultural clusters. None of the Ukrainian regions blend with Russian or Polish regions. Instead, the country occupies its own unique cultural space on the map. Table A2 in the Appendix presents the correlation matrix between the dimensions and the domains. Again, D1 is strongly overlapping with EU-values, while D2 is mostly correlated with civic honesty.

Figure 2. Multidimensional scaling analysis with NUTS1 regions of Russia, Ukraine, Poland, and Germany, using data on all 6 value domains. Note. Modern MDS. Stress = 0.054, N = 39. Data from EVS and WVS 2017-2021. Ukraine is presented with data only from the EVS as the WVS lacked data on NUTS1 regions.

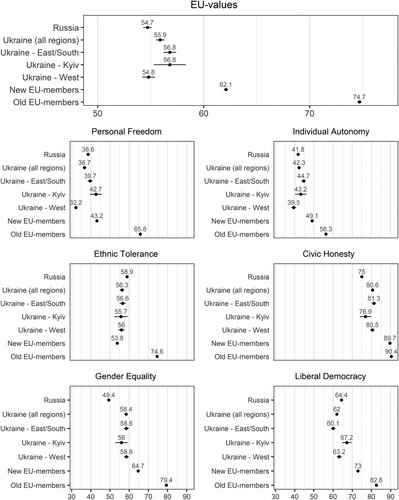

Focusing more closely on the EU-values and its constituting value domains, indicates that Ukraine and Russia are substantially behind both new and old EU-member states. Both countries support EU-values to a very similar degree, albeit statistically significantly stronger in Ukraine by 1.2 points. However, there are some more significant differences between Ukraine and Russia in specific value domains. Ukrainians support gender equality and civic honesty more strongly than Russians (9 and 5.6 points, respectively) but are less tolerant of ethnic diversity, and less supportive of personal freedoms and liberal democratic values (2.6, 1.9, and 2.4, respectively).

Contrary to Huntington’s proposition, Western Ukraine has almost identical support for EU-values as Russia while Eastern/Southern Ukraine and Kyiv are not less but more in support of EU-values than the regions in the Western part of the country. Western Ukraine supports most domains less strongly than East/South Ukraine, but with the most notable exception of liberal democracy, where the support is 3.1 points higher in the West, while that in Kyiv is 7.1 points higher than in the East/South. In other words, Western Ukraine is not more Euro-minded as Huntington claims, but it seems to have slightly stronger democratic aspirations. As expected, the older EU-member states lead in support of EU-values in all domains, followed by the new member states. A notable exception is ethnic tolerance where the new member states experienced a recent backlash most likely associated with the refugee crisis (Akaliyski et al. Citation2022).

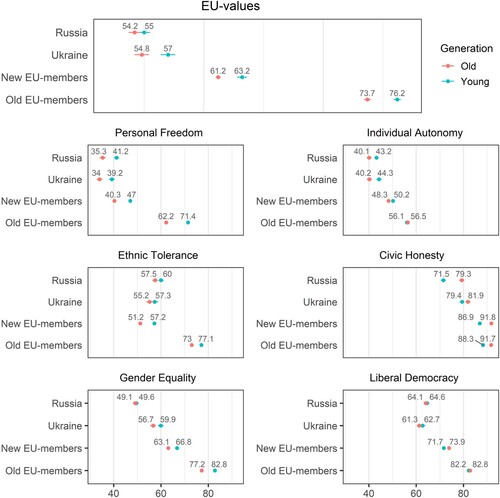

demonstrates that the support for EU-values among the older generation of Russians and Ukrainians is almost identical (only 0.6 point difference) but it is significantly larger among the younger generation (2 points) as the new generation of Ukrainians is more supportive of EU-values. This pattern is especially pronounced with regard to gender equality, where young Russians, in defiance of the pattern elsewhere, are almost just as traditional as their older compatriots, while young Ukrainians are significantly more progressive in that regard (3.2 points). Similarly, the gap is also apparent in civic honesty as young Russians are much less strict on dishonest-illegal behavior (7.8 points), compared to Ukrainians where the difference is 2.5 points. Noteworthy, civic honesty was the only domain where we find weaker support among the younger generation compared to the old one in all countries (Ukraine, Russia, as well as the old and new EU-member states), however, the support remains relatively high among EU-members. These findings provide some support for our expectations that particularly generational differences are pronounced between Ukrainians and Russians, with younger Ukrainians reflecting EU-values more than younger Russians.

Further, we present more refined multivariate analyses. shows four models predicting the support for EU-values in Ukraine. In agreement with the previous analyses and contrary to Huntington’s thesis, Model 1 reveals that the predominantly Russian-speaking East/South and Kyiv regions show stronger support for EU-values. In the second model, we include cultural heritage variables – religion and language – which explain most of these regional differences. Again, in defiance of Huntington’s thesis, Catholic and Protestant Ukrainians are not more supportive of EU-values. On the contrary, they seem to be even slightly less so compared to Orthodox Ukrainians, although the coefficient is not statistically significant. The main factor that explains differences between East/South and Western regions and Kyiv is speaking Ukrainian language which is associated with lower support for EU-values. In the third model, we include socio-demographic variables instead of cultural heritage predictors. Female, younger, more educated, living in larger cities, and working full-time respondents support EU-values significantly more strongly. These effects account for some of the regional-level differences, especially those between Kyiv and the Western regions where the difference turns insignificant. In the last model, including all predictors, only speaking Ukrainian language remains significant among the cultural heritage/geographic predictors, implying that these respondents give less support for EU-values.

Table 1. Predictors of support for EU-values in Ukraine, 2020.

Tables A3 to A8 in the Appendix present the same analyses but in each of the six domains of EU-values. Differences between East/South and West are explained by the other predictors on all domains aside from civic honesty where East/South has 3.23 points higher support, and liberal democracy, where it has 7.54 points lower than the West of Ukraine. Catholics/Protestants are more EU-minded only concerning ethnic tolerance (5.88 points in the full model), but less so in individual freedom (−3.41 points in the full model) and liberal democracy (−3.08 in the full model). Ukrainian-speakers are less supportive of EU-values on personal autonomy, individual freedom (but not significant in the full model), and liberal democracy, and not more supportive in any domains.

Discussion

Even though Vladimir Putin and Ursula von der Leyen have both been arguing that Ukrainian values are ‘theirs’, an analysis of the European Values Study and World Values Survey portrays a clear but rather nuanced story. Our analysis comes down to three main conclusions. First, the values of Ukrainians do indeed lean more towards the Russian Slavic-Orthodox values than Western European values. Importantly, European nations themselves do not represent a single monolithic culture – they are split into four distinct clusters. Not only Ukraine but also majority-Orthodox current EU-members such as Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Romania fall in the same Slavic-Orthodox cluster as Russia. This finding suggests that cultural-historical legacies may leave an enduring imprint on nations’ value development (cf. Inglehart and Baker Citation2000) but value differences are not necessarily an obstacle to EU-membership.

Second, Ukraine appears a fairly homogenous country when it comes to the support for EU-values, and we find little evidence to the popular narrative that it is a deeply divided or ‘cleft’ country in cultural terms. In our analyses, we accounted for relevant variation within the Ukrainian nation-state in several ways, i.e., geographical, linguistic, and religious differences. While there are statistically significant differences at the individual level, somewhat corroborating earlier evidence (see Onuch and Hale Citation2018) and requesting a more thorough analysis of the role of language in Ukraine (cf. Bureiko and Moga Citation2019), these differences are negligibly small in the broader European scope.

Third, Ukrainians clearly share a distinct national culture from Russians, as well as from Poles (among the most Eastern EU-member state with whom Ukraine shares close historical ties), positioning itself in the cultural space between its most populous neighbors from the East and West. Our analysis provides evidence that particularly young Ukrainians are more outspoken towards EU-values than older Ukrainians, while the same generational difference does not occur in Russia. Following insights from values research (cf. Inglehart Citation1997), one conclusion might be that such generational difference presents a values shift away from Russian values towards more Western European values given the new geopolitical environment.

How do our findings relate to the four distinct theories that we put to the test? Somewhat weak support is found for a naïve interpretation of Modernization and Human Development theories. Sharing a lower level of socio-economic development, Slavic-Orthodox countries, including Ukraine and Russia, also support EU-values less strongly as these theoretical approaches would predict. Moreover, the wealthiest Northwestern European countries embrace these values most strongly. However, in terms of national economy and societal stability, Ukraine is in a disadvantaged position compared to Russia, yet, in terms of values, it is less leaning towards traditional values compared to Russia. One possible interpretation is that it is not Ukrainian values that are particularly Western but that Russian people have fallen victims of the Kremlin’s propaganda machine which aims to instill traditional Orthodox values that are at odds with EU-values (Edenborg Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Persson Citation2015; Shcherbak Citation2022).

Social Identity Theory in combination with diffusion theories are also potentially viable theoretical approaches to explain Ukraine’s stronger EU-values than Russia. However, they display some limitations because, despite being pro-European, we lack evidence that the Western parts of Ukraine are more influenced by Western European values than Ukrainian Southern and Eastern regions. This finding rather lends credibility to nation-building theories, which we discuss further below.

Mixed support can be found for a naïve reading of the ‘Clash of Civilization’-thesis as Ukraine clearly groups together with Russia as part of the Slavic-Orthodox cluster (Riabchuk Citation2003). This clear clustering based on historically predominant religion signifies possible long legacies of historical divisions in Europe that may go as back to the Great Schism in 1054, or even to the split of the Roman Empire in the 4th century AD (Akaliyski Citation2017). Subsequently, Western Europe underwent a unique process of societal transformation during the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolutions that distinguish it from the rest of the world (Huntington Citation1993; Welzel Citation2013). Religious legacies, thus, clearly overlap other historical, economic, sociopolitical, linguistic, and geographic patterns that are difficult to distinguish from one another (Akaliyski Citation2017). Although the cultural clustering in Europe based on historical religions is compelling, it may be naïve to attribute any causal impact of religion itself.

We find little support for the second expectation based on Huntington’s thesis, namely that Ukraine is a ‘cleft’ country when it comes to its cultural values. Although a number of studies point to political or ideological divisions within Ukraine along regional and linguistic lines (Katchanovski Citation2006a; Citation2016; Kulyk Citation2011; Riabchuk Citation2015), there is little evidence that Ukraine is markedly culturally divided. Instead, we find strong support for nation-building theories, implying that countries serve as gravitational forces that socialize all its members regardless of their religious and other internal divisions (Akaliyski et al. Citation2021). This finding aligns well with previous studies depicting the importance of religious-historical legacies at the national, but not on the sub-national level (Inglehart and Baker Citation2000; Minkov and Hofstede Citation2014). Specifically for the Ukrainian case, other studies in the nationalism literature show that albeit the concept of identity is rather complex (Onuch and Hale Citation2018), the fault line in Huntington’s work finds little empirical support (Zhurzhenko Citation2002). The cultural decolonization of Ukraine (Fomenko Citation2022; Zhurzhenko Citation2021), breaking up with the Soviet past (Rozenas and Vlasenko Citation2022) and the education policies targeting strengthening of Ukrainian national identity (Korostelina Citation2011, Citation2013) could have contributed to homogenizing Ukrainian culture and distancing it from that of Russia. The shift towards citizenship-based civic national identity (Barrington Citation2022), associated with pro-European and pro-democratic attitudes (Onuch Citation2023) may have further eroded ethno-linguistic and regional divisions, especially after the Maidan Revolution and the Russian aggression (Kulyk Citation2018).

Curiously, however, we find some evidence that Western Ukrainians and particularly Ukrainian-speakers are more opposed to EU-values than their West/South and Russian-speaking counterparts. Although these differences were trivial compared to the variation between countries, this is a noteworthy observation. We find that the regional differences are completely explained by socio-demographic and linguistic/religious differences as Western Ukraine tends to be less economically developed, more rural, more religious and Ukrainian-speaking. If the first two factors are real causes of the differences, this would speak in favor of modernization and human development theories. Speaking Ukrainian language remained a significant predictor even taking every other factor into consideration. It is possible that our predictors do not fully capture differences in socio-economic status between Ukrainian and Russian speakers, the latter of which have been found to be in an advantaged position in the post-communist transition (Constant et al. Citation2012).

The complexity of identity in the Ukrainian context requires a more detailed analysis. For instance, Riabchuk (Citation2015) argues, updating his earlier position that Ukraine consists of ‘two nations’ (Riabchuk Citation2003), that ideological differences (understood as orientation towards Russia or the West) may still coincide with cultural markers in Ukraine. In the absence of survey items on identification with either entity, we are unable to validate this claim, making that future studies are encouraged to scrutinize this alleged divide across ideological lines. This also underlines the feasibility of more refined longitudinal analyses. While our work has identified meaningful similarities and differences, not only within Ukraine, but also with Russia and old and new EU-member states, long-term trends in values change, with particular attention to cohort changes, are also promising. Furthermore, we face methodological challenges to account for the full scope of our desired exploration as the Russia-occupied territories remain beyond the reach of standard survey tools used by EVS/WVS. Since the line – to the extent that it exists – dividing Ukraine in terms of political identities has been shifting eastward (Kulyk Citation2016), it is possible that the real cultural differences have turned out to be between the current and the occupied Ukrainian territories. We acknowledge it as a limitation of our study that our data on Ukraine was collected in 2020, before the full-scale invasion by Russia. It is possible that this dramatic event may have led to considerable changes in Ukrainian values (The Economist Citation2023). As cited by The Economist (Citation2023), Sofiia Lapina, the head of the activist group Ukraine Pride, ‘the shift in attitudes on gay issues partly reflects Ukrainian aspirations to be culturally and politically closer to Europe’. Last but not least, some authors (cf. Rodgers Citation2006) claim that not all complexities in the Ukrainian East–West divide can be untangled by survey research, we welcome other techniques to document value similarities and differences, including qualitative research and media studies.

Regardless of our findings, Ukraine’s geographic proximity to the European Union opens the possibility for diffusion of EU-values as the country further increases its entanglement with the West. Many Western universities, for example, opened their doors more widely to Ukrainian students and scholars under the condition that they return back home to rebuild the country after the war (Ukrainian Global University Citation2022). As research shows that EU integration might accelerate values change (Akaliyski and Welzel Citation2020; Oshri et al. Citation2016), the Kremlin could have been fueled by fear that further European integration is not merely a political process but also a mechanism for pivoting Ukraine culturally towards the West and away from Russia. In that sense, this war, which always lends itself to ingroup and outgroup thinking, is an opportunity to diagnose the extent to which Ukraine has drifted towards Western European values in the current turmoil. Future research needs to tell to what extent this perspective materializes.

It may seem sobering that according to our findings Ukraine has a long road to Brussels in terms of the adaptation of the EU-values script, yet there are reasons to believe that the Western aspirations may, in the long run, bring convergence with EU nations. In theory, strong ties with the West, as well as socio-economic modernization and high existential security would be conducive to such a transformation of Ukrainian society. The current conflict with Russia enhances the first condition but worsens the second condition, thus increasing the uncertainty of the value development of Ukraine in the near future.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (344.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of Politics and Culture in Europe Colloquium at Maastricht University, as well as Juan Diez-Medrano, Gergana Noutcheva, and Oleksandr Rydnyk for useful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Plamen Akaliyski

Plamen Akaliyski is a postdoctoral researcher at University Carlos III of Madrid and a visiting scholar at Maastricht University. He holds a PhD in sociology from the University of Oslo and an MA from Free University Berlin. From 2019 to 2021, he was a postdoctoral researcher at Keio University in Tokyo. His research interests are particularly in understanding global cultural value diversity and change, considering the role of historical legacies and processes of modernization. He has published in European Journal of Political Research, Journal of European Integration, and Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology.

Tim Reeskens

Tim Reeskens is an Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology at Tilburg University and Program Director of the European Values Study Netherlands. At the same university, he coordinates the Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence of European Values, which studies and teaches on the relation between values, public opinion and policy on complex social issues. Tim co-authored the Atlas of European Values: Change and Continuity in Turbulent Times (Open Press TiU, 2022). His research appeared in European Societies, European Sociological Review, and the Journal of European Social Policy.

Notes

1 Article 2 describes that ‘the Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.’

2 The old member states are Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden. The new member states are Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

3 Important to note that the majority of Ukrainian Catholics belong to the Greek Catholic Church, which combines dogmas of the Catholic Church with some Orthodox rituals (e.g., the holiday calendar, priests' attire, the singing, the seasonal holidays, etc.).

4 Huntington offers two ways of splitting the country: one separating only the Western-most regions of Ukraine which formerly belonged to Poland and the Habsburg Empire from the rest, and one splitting the country in two approximately equal areas based on their predominant geopolitical orientation. We chose the latter categorization as that creates more comparable geographical groups. However, we also use religion and language as predictors in multivariate regressions.

References

- Akaliyski, P. (2017) ‘Sources of societal value similarities across Europe: evidence from dyadic models’, Comparative Sociology 16(4): 447–70.

- Akaliyski, P. (2019) ‘United in diversity? The convergence of cultural values among EU member states and candidates’, European Journal of Political Research 58(2): 388–411.

- Akaliyski, P. and Welzel, C. (2020) ‘Clashing values: supranational identities, geopolitical rivalry and Europe’s growing cultural divide’, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 51(9): 740–62.

- Akaliyski, P., Welzel, C., Bond, M. H. and Minkov, M. (2021) ‘On “Nationology”: the gravitational field of national Culture’, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 52(8–9): 771–93.

- Akaliyski, P., Welzel, C. and Hien, J. (2022) ‘A community of shared values? dimensions and dynamics of cultural integration in the European Union’, Journal of European Integration 44(4): 569–90.

- Anderson, B. (1983) Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso.

- Barrington, L. (2022) ‘A new look at region, language, ethnicity and civic national identity in Ukraine’, Europe-Asia Studies 74(3): 360–81.

- Bilefsky, D., Pérez-Peña, R. and Nagourney, E. (2022) The Roots of the Ukraine War: How the Crisis Developed. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/article/russia-ukraine-nato-europe.html.

- Borg, I., Groenen, P. J. F. and Mair, P. (2013) Applied Multidimensional Scaling, Springer.

- Bureiko, N. and Moga, T. L. (2019) ‘The Ukrainian–Russian linguistic dyad and its impact on national identity in Ukraine’, Europe-Asia Studies 71(1): 137–55.

- Constant, A. F., Kahanec, M. and Zimmermann, K. F. (2012) ‘The Russian-Ukrainian earnings divide1’, Economics of Transition 20(1): 1–35.

- Darden, K. and Mylonas, H. (2016) ‘Threats to territorial integrity, national mass schooling, and linguistic Commonality’, Comparative Political Studies 49(11): 1446–79.

- Deutsch, F. and Welzel, C. (2016) ‘The diffusion of values among democracies and Autocracies’, Global Policy 7(4): 563–70.

- Dimaggio, P. J. and Powell, W. W. (1983) ‘The iron cage revisited - institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational Fields’, American Sociological Review 48(2): 147–60.

- The Economist (2023) Ukraine’s gay soldiers fight Russia—and for their rights. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/europe/2023/04/05/ukraines-gay-soldiers-fight-russia-and-for-their-rights.

- Edenborg, E. (2018a) ‘Homophobia as geopolitics: ‘traditional values’ and the negotiation of Russia’s place in the world’, in J. Mulholland, N. Montagna and E. Sanders-McDonagh (eds.), Gendering Nationalism, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Edenborg, E. (2018b) ‘Who heeds the call? bordering, state identity and Russia’s global mission of “traditional values.”’, Ontological Security, Borders and Margins 1: 21–6.

- Euronews (2022) Ukraine one of us and we want them in the EU, von der Leyen tells Euronews. In Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/video/2022/02/27/ukraine-is-one-of-us-and-we-want-them-in-eu-ursula-von-der-leyen-tells-euronews.

- European Union (2012) Consolidated version of the treaty on European Union. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri = OJ:C:2008:115:0013:0045:en:PDF.

- EVS (2020) European Values Study 2017: Integrated Dataset (EVS 2017), ct: GESIS Data Archive. https://www.ZA7500DatafileVersion4.0.0, doi:10.4232/1.13560.

- Feklyunina, V. (2016) ‘Soft power and identity: Russia, Ukraine and the ‘Russian world(s).’’, European Journal of International Relations 22(4): 773–96.

- Fomenko, O. (2022) ‘Brand new Ukraine? cultural icons and national identity in times of war’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, doi:10.1057/s41254-022-00278-y.

- Gerhards, J. (2010) ‘Non-discrimination towards homosexuality: The European union’s policy and citizens’ attitudes towards homosexuality in 27 European countries’, International Sociology 25(1): 5–28.

- Güneyli̇oğlu, M. (2022) ‘The norm contestation and the balance of soft power in the PostSoviet region: The eurasian economic union versus the European Union’, SİYASAL Journal Political Sciences 31(2): 323–47.

- Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E. and Puranen, B. (2020) World Values Survey: Round Seven–Country-Pooled Datafile. https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.10.

- Headley, J. (2015) ‘Challenging the EU’s claim to moral authority: Russian talk of ‘double standards.’’, Asia Europe Journal 13(3): 297–307.

- Huntington, S. P. (1993) ‘The clash of civilizations?', Foreign Affairs 72(3): 22–49.

- Huntington, S. P. (1996) The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Inglehart, R. (1997) Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 Societies, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, R. and Baker, W. E. (2000) ‘Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional Values’, American Sociological Review 65(1): 19–51.

- Inglehart, R. and Welzel, C. (2005) Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Katchanovski, I. (2006a) Cleft Countries: Regional Political Divisions and Cultures in Post-Soviet Ukraine and Moldova, Stuttgard: Columbia University Press.

- Katchanovski, I. (2006b) ‘Regional political divisions in Ukraine in 1991–2006’, Nationalities Papers 34(5): 507–32.

- Katchanovski, I. (2014) East or West? Regional Political Divisions in Ukraine since the “Orange Revolution” and the “Euromaidan.” https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract = 2454203.

- Katchanovski, I. (2016) ‘The separatist War in donbas: A violent break-up of Ukraine?’, South European Society & Politics 17(4): 473–89.

- Korostelina, K. (2011) ‘Shaping unpredictable past: national identity and history education in Ukraine’, National Identities 13(1): 1–16.

- Korostelina, K. (2013) ‘Constructing nation: national narratives of history teachers in Ukraine’, National Identities 15(4): 401–16.

- Kulyk, V. (2011) ‘Language identity, linguistic diversity and political cleavages: evidence from Ukraine’, Nations and Nationalism 17(3): 627–48.

- Kulyk, V. (2016) ‘National identity in Ukraine: impact of euromaidan and the War’, Europe-Asia Studies 68(4): 588–608.

- Kulyk, V. (2018) ‘Shedding Russianness, recasting Ukrainianness: The post-Euromaidan dynamics of ethnonational identifications in Ukraine', Post-Soviet Affairs 34(2-3): 119–138.

- Kuzyk, P. (2019) ‘Ukraine’s national integration before and after 2014. shifting ‘east–west’ polarization line and strengthening political community’, Eurasian Geography and Economics 60(6): 709–35.

- Linde, F. (2016) ‘The civilizational turn in Russian political discourse: from pan-europeanism to civilizational distinctiveness’, The Russian Review 75(4): 604–25.

- Luijkx, R., Sieben, I. and Reeskens, T. (2022) ‘Turning a page in the history of European values Research’, in R. Luijkx, T. Reeskens and I. Sieben (eds.), Reflections on European Values. Honouring Loek Halman’s Contribution to the European Values Study. Tilburg: Open Press TiU, pp. 14–27.

- Meyer, J. W., Boli, J., Thomas, G. M. and Ramirez, F. O. (1997) ‘World society and the nation-state’, The American Journal of Sociology 103(1): 144–81.

- Minesashvili, S. (2022) ‘Before and after 2014: russo-Ukrainian conflict and its Ukraine’, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 1–27.

- Minkov, M. and Hofstede, G. (2014) ‘Nations versus religions: which Has a stronger effect on societal values?’, Management International Review 54(6): 801–24.

- Noutcheva, G. (2018) ‘Whose legitimacy? The EU and Russia in contest for the eastern neighbourhood’, Democratization 25(2): 312–30.

- Onuch, O. (2023) ‘European Ukrainians and their fight against Russian invasion’, Nations and Nationalism 29(1): 53–62.

- Onuch, O. and Hale, H. E. (2018) ‘Capturing ethnicity: the case of Ukraine’, Post-Soviet Affairs 34(2–3): 84–106.

- Oshri, O., Sheafer, T. and Shenhav, S. R. (2016) ‘A community of values: democratic identity formation in the European Union’, European Union Politics 17(1): 114–37.

- Persson, E. (2015) ‘Banning “homosexual propaganda”: belonging and visibility in contemporary Russian Media’, Sexuality and Culture 19(2): 256–74.

- Peterson, M. F., Søndergaard, M. and Kara, A. (2018) ‘Traversing cultural boundaries in IB: The complex relationships between explicit country and implicit cultural group boundaries at multiple levels’, Journal of International Business Studies 49(8): 1081–99.

- Pop-Eleches, G. and Robertson, G. B. (2018) ‘Identity and political preferences in Ukraine – before and after the Euromaidan’, Post-Soviet Affairs 34(2–3): 107–18.

- Putin, V. (2022) Address by the President of the Russian Federation. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67828.

- R Core Team (2022) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Riabchuk, M. (2003) Ukraine: One state, two countries? London: Eurozine. https://www.eurozine.com/ukraine-one-state-two-countries/.

- Riabchuk, M. (2007) ‘Ambivalence or ambiguity? Why Ukraine Is trapped between east and West’, in S. Velychenko (ed.), Ukraine, the EU and Russia: History, Culture and International Relations, pp. 70–88. Palgrave Macmillan UK

- Riabchuk, M. (2015) ‘Two ukraines’ reconsidered: The end of Ukrainian ambivalence?’, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 15(1): 138–56.

- Rodgers, P. (2006) ‘Understanding regionalism and the politics of identity in Ukraine’s eastern borderlands’, Nationalities Papers 34(2): 157–74.

- Rozenas, A. and Vlasenko, A. (2022) ‘The real consequences of symbolic politics: breaking the soviet past in Ukraine’, The Journal of Politics 84(3): 1263–77.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2006) ‘A theory of cultural value orientations: explication and applications’, Comparative Sociology 5(2–3): 137–82.

- Shcherbak, A. (2022) ‘Russia’s “conservative turn” after 2012: evidence from the European social Survey’, East European Politics, 1–26.

- Smith, A. D. (1998) Nationalism and Modernism: A Critical Survey of Recent Theories of Nations and Nationalism, London: Routledge.

- Spodarets, G. (2017) ‘One river, Two ukraines? Yurii Andrukhovych’s imagined geography of east-central Europe’, Central Europe 15(1–2): 45–57.

- StataCorp (2021) Stata Statistical Software: Release 17, College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

- Suslov, M. (2018) ‘Russian world concept: post-soviet geopolitical ideology and the logic of spheres of influence.’, Geopolitics 23(2): 330–53.

- Tajfel, H. and Turner, J. C. (2004) ‘The social identity theory of intergroup behavior’, in J. T. Jost and J. Sidanius (eds.), Political Psychology: Key Readings, pp. 276–93. New York and Hove: Psychology Press.

- Ukrainian Global University (2022) Ukrainian Global University. https://uglobal.university/.

- United Nations Development Program (2019) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT DATA. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center.

- von der Leyen, U. (2022) Statement by President von der Leyen on the Commission’s opinions on the EU membership applications by Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia,. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_22_3822.

- Wawrzonek, M. (2014) ‘Ukraine in the “gray zone”: between the “Russkiy Mir” and Europe’, Eastern European Politics and Societies: EEPS 28(4): 758–80.

- Welzel, C. (2013) Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- World Bank (2021) World Development Indicators Database. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/.

- Yatsenyuk, A. (2014) “Ukraine shares European values” says interim PM. BBC News. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26681876.

- Zelenski, V. (2022) Watch: “We are fighting for the values of Europe,” Zelenskyy tells US Congress. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/2022/03/16/watch-live-ukraine-president-zelenskyy-set-to-address-us-congress.

- Zhurzhenko, T. (2002) The myths of two Ukraines. Eurozine. https://www.eurozine.com/the-myth-of-two-ukraines/.

- Zhurzhenko, T. (2021) ‘Fighting empire, weaponising culture: the conflict with Russia and the restrictions on Russian mass culture in post-maidan Ukraine’, Europe-Asia Studies 73(8): 1441–66.