ABSTRACT

The unequal division of cognitive labor within households, and its potential association with mental load and stress, has gained substantial interest in recent public and scholarly discussions. We aim to deepen this debate theoretically and empirically. First, going beyond the question of whether the division of cognitive labor is gendered, we connect cognitive household labor with existing stress theories and ask whether men and women typically perform cognitive labor tasks that involve different levels of stress. We then discuss whether women perform these stressful tasks more often, making them more prone to higher levels of family–work conflict. Second, we test the association between the division of cognitive labor and family–work conflict empirically using large-scale survey data from 10 European countries within the Generations & Gender Programme (GGP). Results based on logistic regressions confirm that a high share of cognitive labor increases women’s family–work conflict, but not men’s. We discuss future directions in the conceptualization and measurement of cognitive labor in the household and its implications for mental load. Through its contributions, this paper lays the foundations for a comprehensive understanding of the implications of an unequal division of cognitive labor in the household for gender inequality.

Introduction

Across all developed nations, gender disparities in labor market participation and pay are tied to the unequal division of household labor – a set of tasks associated with household maintenance and child rearing (Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard Citation2010; Schober Citation2013). Studies consistently find that women perform a disproportionally high share of these tasks, even in the most egalitarian contexts (Moreno-Colom Citation2017; Weeks Citation2022). This unequal division of household tasks constrains women’s availability for paid work, decreases their earnings, and hampers their career progression (Budig and Hodges Citation2010; Thébaud Citation2010).

The lion’s share of the scholarship on the gendered division of household labor has focused on two types of task: physical tasks, such as cleaning, doing laundry, or grocery shopping; and socio-emotional tasks that involve affect management, like calming down an overly excited child, supporting a partner, or investing in social relations (Erickson Citation2011; Newkirk et al. Citation2017). Recently, scholars have convincingly argued that cognitive housework is a third task type that is unequally divided within couples (Offer Citation2014; Ciciolla and Luthar Citation2019; Daminger Citation2019; Robertson et al. Citation2019). Cognitive housework activities include managing the household budget, planning family activities, anticipating needs, delegating assignments, identifying and choosing among options, and monitoring outcomes.

Cognitive household labor can be an important and underappreciated mechanism underlying gender inequality within families and within the labor market. First, prior studies suggest that women perform the majority of this work, even among couples that share other tasks equally (Daminger Citation2019). Moreover, cognitive labor is rarely talked about, acknowledged, or outsourced, making it an ever-present burden that falls mostly on women (Robertson et al. Citation2019). Second, discussions about cognitive labor suggest that it induces a mental load that can lead to adverse outcomes, like stress and family–work conflicts, thus hindering labor market outcomes (Treas and Tai Citation2012; Offer Citation2014; Dean et al. Citation2021).

Claims regarding the division of labor and its adverse consequences, appealing as they are, still rest on theoretically and empirically weak grounds. Theoretically, we lack a clear description of the mechanism linking cognitive labor to adverse outcomes. For example, we do not know whether all cognitive tasks induce stress in a similar manner or whether the adverse consequences of performing cognitive labor are gender-specific. Empirically, we lack a population-level understanding of the division of cognitive labor and its consequences. Existing evidence on cognitive labor is primarily based on non-random small samples that are, by and large, geographically homogenous and US-based (Daminger Citation2020; Calarco et al. Citation2021; Brown Citation2022), or that focus on very specific kinds of cognitive labor, like financial decision-making or household management (Johnston et al. Citation2016; Ciciolla and Luthar Citation2019).

This paper is intended as a first step toward understanding and testing the gender-specific link between the performance of cognitive labor, stress, and family–work conflict. To this end, the paper makes two unique contributions to the literature. First, we develop a theoretical understanding of how the performance of cognitive labor can induce stress and thereby lead to adverse outcomes, like family–work conflict. Our theoretical framework draws on theories of workplace stress, which direct attention to the characteristics of tasks and their associated rewards and acknowledgment in order to understand their association with stress (Karasek and Theorell Citation1990; Kushnir and Melamed Citation2006; Sperlich and Geyer Citation2016). We posit that women may be more affected by the negative impacts of cognitive labor because they do more of it, and they tend to take on tasks that are more frequent, complex, and over which they have a lower level of control. Additionally, men are more likely than women to be praised for performing cognitive tasks, which renders them more stressful for women. The gendered specialization and acknowledgment of cognitive labor, in turn, can make women more prone to experiencing its adverse consequences, like family–work conflicts.

Second, we provide the first population-level estimates of the association between the overall division of cognitive labor and family–work conflict, as one potential adverse outcome of cognitive labor, in European countries. We analyze information on nationally representative samples from 10 European countries, obtained from the Generations & Gender Programme (GGP).Footnote1 We empirically evaluate the link between the self-reported division of cognitive labor and information on whether the respondent arrived at work too exhausted to function well because of household work, as an indicator for family–work conflict.

Our results reveal several key findings. First, there is substantial variation in how couples divide cognitive labor, as well as in how men and women perceive this division. Second, the division of cognitive labor has consequences for the family–work conflict experienced by women, but not men. Women who perform the majority of cognitive labor have a higher risk of arriving at work already exhausted. Men, by contrast, seem to be less affected by their (self-reported) division of cognitive labor in the household. We predict substantially lower risks of arriving at work exhausted for men compared to women – even if they report sharing cognitive labor equally with their spouse or report taking up a higher share than their spouse.

Theoretical motivation and significance

Cognitive labor and its division

Cognitive household labor refers to a host of mental tasks that are distinct from physical or emotional tasks. One of the most clearly articulated definitions of cognitive labor is that offered by Daminger (Citation2019), who draws on in-depth interviews with upper-middle-class couples in the Boston area. She outlines four types of cognitive household task: (1) anticipation, which includes recognizing an upcoming need or problem; (2) identification, which refers to researching and determining the options for meeting the upcoming need; (3) decisions, which include considering and choosing among options; and (4) monitoring, which includes supervising the execution of decisions and ensuring they sufficiently address the need. In parallel work, Robertson et al. (Citation2019) outline six types of cognitive labor: (1) planning and strategizing; (2) monitoring and anticipating needs; (3) meta-parenting; (4) knowing; (5) managerial thinking; and (6) self-regulating. Although some of these dimensions overlap with those outlined by Daminger (Citation2019), they include additional tasks, such as ‘constant learning’ and ‘remembering’, as (taxing) kinds of cognitive labor, as well as ‘making contingency plans’, ‘delegating work’, and ‘reflecting and debating parenting decisions and styles’.

Cognitive labor generally takes two forms: it can be directly associated with specific physical, social, and emotional tasks as a cognitive ‘overhead’. Consider, for example, the cognitive labor associated with a family trip. The organization of the trip involves anticipating the needs and limitations of all participants, identifying potential destinations and activities to include in the trip, deciding among options, delegating tasks to other family members, and monitoring the results. Often, while all family members engage in the physical and social task of going on the trip, the cognitive task of organizing the trip is carried out by one person. Alternatively, cognitive labor can also be a task of its own. Consider the task of financial decision-making and budget planning, for instance, which involves substantial planning, strategizing, research, and monitoring – all without an actual physical event in view.

Unlike other forms of household tasks, couples rarely negotiate the division of cognitive tasks, partly because they lack a suitable vocabulary to discuss them (Robertson et al. Citation2019). For this reason, the division of cognitive tasks is often governed by gender norms and expectations, which can lead to unequal division of labor and task specialization (Ridgeway and Correll Citation2004; Dean et al. Citation2021; Luthra and Haux Citation2022). Consistent with this expectation, Daminger (Citation2019) found that among upper-middle-class couples that considered themselves largely egalitarian, women tended to do most tasks related to anticipation and monitoring, while decision-making tasks – especially those pertaining to costly or highly consequential matters – were more equally divided. Similarly, in a survey of 400 mainly upper-class US women, Ciciolla and Luthar (Citation2019) found that women performed the majority of ‘invisible labor’ associated with day-to-day household management, while decisions pertaining to values and large financial decisions were most often shared by the couple (see also Offer Citation2014; Brown Citation2022).

In sum, cognitive household labor is an ever-present but rarely acknowledged set of household tasks. These tasks are also unequally divided among heterosexual couples. It is argued that these tasks can contribute to labor market inequality because they induce stress and family–work conflict.

Cognitive labor, stress, and family–work conflict

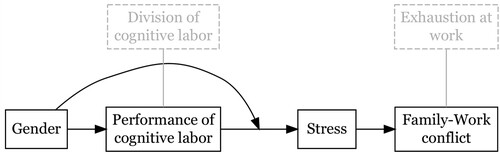

The potential adverse implications of the gendered division of cognitive labor on gender inequality stem largely from its association with mental load, as depicted in . Cognitive tasks require mental and cognitive effort, and a greater number of cognitive tasks within a given time span requires larger amounts of cognitive capacity. The relation of cognitive demands to cognitive capacity is often referred to as mental load, or, in other fields (like ergonomics), as mental workload (Hancock et al. Citation2021). A persistent, unacknowledged mental load can be stressful (Gaillard Citation1993) and can consequently increase levels of exhaustion (Díaz-García et al. Citation2021). This exhaustion can then create conflicts at home, spill over to the workplace, and enhance family–work conflict (Offer Citation2014).

Figure 1. How the performance of cognitive labor leads to family–work conflict (Dashed items refer to the measures we use in the empirical analysis.)

Despite rich and impressive descriptions of the gendered division of cognitive household labor (i.e. the arrow between gender and the performance of cognitive labor in ), the theoretical understanding of how this particular kind of labor is associated with stress and work–family conflict for men and women is still limited. Our goal is to take initial steps in the theoretical and empirical elaboration of these latter associations in order to gain a deeper understanding of the potential consequences of the gendered division of cognitive household labor for inequality. To do this, we draw on theories of stress (Karasek and Theorell Citation1990) and their application to household work (Kushnir and Melamed Citation2006; Sperlich and Geyer Citation2016), in order to shed light on how cognitive tasks result in different stress levels. These theories emphasize the role of a task’s effort–reward imbalance in inducing stress (Siegrist and Wahrendorf Citation2016). From this standpoint, the impacts of performing cognitive labor on stress are a function of the characteristics of the tasks performed and their total volume.

The extent of mental effort associated with a task is a function of three main characteristics: (1) the task’s frequency (2) the degree of control an individual has over the task and its outcome, and (3) the task’s complexity. For instance, the tasks ‘doing small repairs’ and ‘organizing joint activities’ – both part of the GGP survey instrument we use in this study – have substantial cognitive ‘overhead’, and require cognitive work before performing the task. However, these tasks differ in terms of effort. Individuals have more control over the outcome of ‘small repairs’ compared with ‘organizing joint activities’, both in terms of control of the process (i.e. the involvement of others) and in terms of control over the outcome, especially if children are involved. The complexity of the tasks also differs. Small repairs tend to involve a specific problem, such as fixing the kitchen sink or repairing a broken toy. Organizing joint activities, by contrast, involves multiple participants, and therefore multiple needs and wants. Thus, the combination of low control and high complexity for ‘organizing joint activities’, but high control and moderate complexity for ‘small repairs’, could lead to a strong effort asymmetry between both tasks, with organizing joint activities being substantially more (cognitive) effort-intensive.

We posit that women perform more high-frequency tasks related to the smooth operation of the household (Ciciolla and Luthar Citation2019). Documentation of cognitive labor suggests that women carry out frequent daily tasks, such as those associated with anticipating the need for clean clothes, groceries, and scheduling, which cumulatively require substantial effort (Daminger Citation2019). Women with children face additional care responsibilities, which require high-frequency and complex cognitive labor (Dean et al. Citation2021). Men, by contrast, typically join in the performance of cognitive tasks when final decisions need to be made, which occurs less frequently (Taniguchi and Kaufman Citation2020). Thus, we expect that women tend to perform more effort-intensive cognitive tasks than men.

However, effort alone is only a limited predictor of stress (Sperlich et al. Citation2013). Low-effort tasks can be very stressful, and high-effort tasks can be very rewarding (Gaillard Citation1993). Stress theories suggest the relation between a task’s effort and reward is predictive of subjective stress. Reward is gained primarily from active acknowledgment of a task’s (successful) performance. This acknowledgment is either given by the individual to themselves, or is signaled during interactions with significant others (e.g. spouse, family members, peers). A high-effort/low-reward combination is one of the strongest predictors of adverse health outcomes and job drop-out (Tsutsumi and Kawakami Citation2004; Bethge and Radoschewski Citation2012). Thus, to understand the effort–reward relation of cognitive labor and its gendered consequences, we need to also consider the norms leading to potentially different distributions of rewards.

Status characteristics theory provides valuable insights into how norms of external and internal rewards are heavily gendered (Correll Citation2001; Ridgeway and Correll Citation2004). Recently, Thébaud et al. (Citation2021) have shown that women are more heavily scrutinized in regard to their housework, highlighting both the norms surrounding the division of household labor and the differential payoffs and costs of deviating from these norms. Recent reports also suggest that most cognitive labor within households remains unacknowledged (Salmi and Sonck-Rautio Citation2018; Robertson et al. Citation2019). Instead, women are typically blamed for failing to ‘think about’ particular issues, or feel guilty for failing self-set standards (Klünder Citation2018; Harrington and Reese-Melancon Citation2022). In contrast, men are more likely to be praised for carrying out cognitive labor, either because they are not socially expected to do so, or because the cognitive labor concerns important financial and costly matters (such as buying a house or identifying financial opportunities for investment). This asymmetry of praise and blame for effort could be crucial for understanding the relation between cognitive labor and stress. Importantly, it suggests that the effect of cognitive labor on stress and family–work conflict could be gendered. In , these gender differences are depicted by the rounded arrow linking gender and the association between the performance of cognitive labor and stress.

The above discussion yields two key insights about the relation between cognitive labor and stress. First, although there are myriad cognitive labor tasks in a household, the tasks that are most pertinent to stress and family–work conflict are those that are frequent, those over which the individual has a low level of control, that are complex, and that give rise to a lower level of internal or external acknowledgment. Extremely low-frequency tasks, like buying a car or a house, complex and visible as they may be, are less likely to induce (long-lasting) stress, and therefore are less pertinent to family–work conflicts (Offer Citation2014). Second, the association between cognitive labor and stress is likely to be gendered, due to strong gender norms governing both the division of cognitive task types and acknowledgment of their performance. The empirical expectation that follows is that the intensity of work–family conflict experienced by women is more closely connected to the division of household cognitive labor than is the case for men.

In the following pages, we empirically investigate the gendered association between the division of cognitive labor and family–work conflict outlined in . Our goal is to shed light on the gendered consequences of the division of cognitive labor. To this end, we leverage population-level variance in the division of cognitive labor in 10 European nations and assess its association with work exhaustion for men and women.

The empirical investigation

Data

We use data from the Generations & Gender Surveys (GGS).Footnote2 The GGS consists of comparative surveys, each collected between 2002 and 2013 from a nationally representative sample of the 18–79-year-old resident population among 19 participating countries (Vikat et al. Citation2007). Within each survey, we obtain individual-level data, with extensive information provided by the respondent about household composition, partnership status, and how the partnership is organized.Footnote3 The main advantage of the GSS data over other commonly used representative studies, such as the International Social Survey Program (ISSP), the European Social Survey (ESS), or the General Social Survey (GSS), is that they contain self-reported information on the division of a more comprehensive list of household tasks, allowing us to proximate the performance of cognitive labor.

The GGS use a shared set of questionnaire modules, rather than a standard questionnaire. Thus, for some countries, central variables for our purposes, like subjective stress or the division of household tasks, are not available (e.g. Italy, the Netherlands, Australia, Norway, or Estonia). Other countries collected these data but have a high share of item non-response or different response scales (like Germany). We do not impute values for missing data because we assume they are not missing at random and we exclude countries with a high share of item non-response.

Our aim is to study the relation between the division of cognitive household labor, stress, and family–work conflict. The GGS does not contain general items for stress or exhaustion, but it does contain items for work–family and family–work conflict. We use a measure of family-related work exhaustion to evaluate family–work conflict. As a result, we are only able to analyze data for employed respondents (though we adjust for whether their partner is employed or not). Additionally, because we are interested in how couples split the household labor between them, we exclude couples who outsource parts of it.Footnote4

Our analytical sample builds on data from 10 countries after the listwise deletion of observations: Bulgaria (N = 2,802), Russia (N = 633) Georgia (N = 1,199), France (N = 1,726) Romania (N = 2,987), Belgium (N = 2,208) Lithuania (N = 2,570), Poland (N = 2,423), Czech Republic (N = 844) and Sweden (N = 2,390). We thus work with a pooled sample of 19,782 employed cohabiting respondents in heterosexual relationships, of whom 8,979 are women and 10,803 are men.Footnote5 All descriptive statistics and analyses are weighted with the country-specific population weights developed by the data distributors.

Measurements

Dependent variable: intensity of family–work conflict

Our outcome of interest is the intensity of family–work conflict, which we measure with information on family-related work exhaustion obtained from responses to the item: ‘I have arrived at work too tired to function well because of the household work I had done’. Respondents can answer ‘never’, ‘once or twice a month’, ‘several times a month’, or ‘several times a week’. We collapsed these categories to two categories: (1) Low family–work conflict includes respondents that listed ‘never’ or ‘once or twice a month’; (2) High family–work conflict includes respondents that answered ‘several times a month’ or ‘several times a week’. Of the respondents in our analytic sample, 9.5% of women and 6.5% of men reported high family–work conflict.

Division of cognitive labor in the household

The main challenge in studying cognitive labor is the absence of a tested, agreed-upon specific measure. The lack of an appropriate vocabulary used by couples to discuss cognitive labor further complicates this task. However, the GGS data offer a more comprehensive list of household tasks than other commonly used surveys, allowing us to approximate a measure of cognitive labor. To construct this measure, we utilize the concept that cognitive labor can manifest (1) as an ‘overhead’ in relation to specific household tasks and (2) as a task on its own. For the former, we ranked the seven GSS items relating to the division of household tasks by their cognitive labor overhead. Inspired by the theoretical description of Daminger (Citation2019) and Robertson et al. (Citation2019), our ranking took into account the anticipation of the need for the task, and planning for it, option identification, decision-making, and plausible outcome monitoring. Our ranking also considered the likelihood that the physical task and the cognitive labor are carried out by the same person. The top three ranked items used to create the measure are: (a) organizing joint social activities; (b) paying bills and keeping financial records; and (c) doing small repairs in and around the house.Footnote6 For the latter, we included three GSS items specifically addressing decision-making tasks: (a) deciding on routine purchases; (b) deciding on expensive purchases; and (c) deciding on social activities. These items cover a range of typically male-dominated, female-dominated, and gender-neutral tasks, enabling us to capture variations in the division of labor across households.

Arguably, the ‘shopping for food’ item can also have a high cognitive labor overhead and could potentially be included in our measure. However, drawing on previous scholarship, we suspect that the cognitive overhead for shopping is gendered and detached from the physical labor associated with the task, which can lead to wrong attribution of the load (Klünder and Meier-Gräwe Citation2018). Typically, women are in charge on anticipating what needs to be bought, putting items on the shopping list, and keeping an eye out for offers, while the physical act of shopping is more equally shared. Thus, while the item ‘doing small repairs’ could be gendered in the performance of the tasks (including the cognitive and physical part), we expect that ‘shopping for food’ is gendered in how couples divide the cognitive and physical parts. For this reason, we decided to include ‘doing small repairs’ item in the cognitive labor scale, rather than ‘shopping for food’. In a sensitivity analysis, we included the item ‘shopping for food’ in the list, instead of ‘small repairs’. This scale slightly shifted the division of cognitive labor but did not influence the associations between the division of labor and stress in the multivariate analyses (see Table A2 and Figure A1 in the Appendix).

Respondents were asked to indicate which person does each task in the household, with the options being ‘always me’, ‘usually me’, ‘equally me and my partner’, ‘usually partner’, ‘always partner’, or ‘always or usually someone else’. To construct the overall measure, we first changed the underlying metric of the response scale to reflect the gender of the performer. If the woman reported that she always does a specific task, she received a value of −2. If she responded ‘usually me’ she received a value of −1. She received a value of 0 for an equal division of the task, +1 if the man usually performs the task, and +2 if the man always does it. We used the same scale for men’s responses: they received −2 if they said the woman always performs a task and +2 if they reported they always preform the task. We then summed up all responses, creating a measure for cognitive labor that ranges between −12 if the woman always performs all tasks and +12 if the man always performs all tasks. We constructed the score this way in order to capture the specialization and the approximate volume of the performance of tasks within the household.Footnote7

One potential limitation of our summation strategy is that it assumes all items are of equal cognitive intensity. This may be a problem if organizing joint activities requires much more cognitive work in comparison to paying bills and keeping financial records. In this case, summing them up would lead to an underestimation of the relevance of the former task and an overestimation of the relevance of the latter. To evaluate the sensitivity of our results to this assumption, we created an alternative measure of cognitive labor division using factor analyses and replicated our main analysis with the factor scores.Footnote8 Because our results did not change, as we report bellow, we report the most accessible version here.

We believe that this measure forms an important step forward in our understanding of the division of cognitive labor. We caution that we do not intend to use it as a valid description of the total volume of cognitive labor within couples, or as a way of determining how they split the overall work. Instead, we claim that this is currently the best-available approximation of the division and performance of cognitive labor. By design, our measure deliberately contains female- and male-type tasks in equal measure and may not reflect the complete division of tasks across couples. As noted above, this strategy allows us to capture variation in the division of labor in order to assess its consequences for work exhaustion. At the same time, we caution that our scale is conservative in estimating the extent to which the division of cognitive labor is gendered. Thus, we posit that large gender differences in family–work conflict correlated with our conservative estimates suggest even stronger underlying gendered processes, which a more refined measure might be able to reveal.

Division of physical labor

As a reliability check for our cognitive labor measure, we assessed its distinctiveness by comparing it with the division of physical labor in the household. We created a complementary scale for physical labor using three household tasks with the lowest cognitive labor overhead: (a) vacuum cleaning; (b) washing dishes; and (c) preparing daily meals. The correlation between the cognitive labor scale and the physical labor scale is weak: 0.05 among men and 0.15 among women, confirming that the two scales capture distinct dimensions of the household labor division.

Adjustment factors

Our estimates adjust for a comprehensive set of individual- and family-level factors that we assume are potential confounders that influence both the division of cognitive labor and family–work conflict. Children are an important source of cognitive labor and its division (Daminger Citation2020), as well as having a large influence on family–work conflict. In line with previous work, we assume that economic hardship increases both family–work conflict (Schieman and Young Citation2011) and women’s share of unpaid labor (Heisig Citation2011). The same is the case for education and the employment status of the partner. The division of labor changes across the life-course (Leopold et al. Citation2018) and we suspect that this is also the case for family–work conflict due to age-specific career paths. We also adjust for variation in self-reported health. Bad health, especially of women, could be a major reason for men’s strong involvement in household work and persons with bad health could also be more prone for work exhaustion. We include indicators for each country because we expect that the base distribution of the division of cognitive labor and family–work conflicts (though not necessarily their associations) are influenced by a countries’ gender contract and work culture. Descriptive statistics for all of the adjustment variables are available in Table A1 in the Appendix.

Analytical strategy

We assess the association between the performance of cognitive labor and family–work conflict by estimating multivariate logistic regressions. For each gender, we estimate four models. First, we assess an unadjusted model that predicts the intensity of family-work conflict as a function of the division of cognitive labor in the household (Models 1 and 5). Next, we sequentially add adjustments for the division of physical labor in the household (Models 2 and 6), individual and family factors (Model 3 and 7), and country and data collection wave indicators (Model 4 and 8). This strategy allows us to observe how the association between cognitive labor and family–work conflict changes once we account for variation in these potential confounders and mediators.Footnote9 For ease of interpretation, and to allow comparison across the models, we report the predicted probabilities for each gender at each point on the cognitive labor scale.

Results

The division of cognitive labor in the household

To set the stage for our analyses, we first describe patterns in the division of cognitive-heavy tasks within households (). The most complex task in our scale is ‘organizing joint activities’, requiring intricate planning, researching, decision-making, and monitoring, often involving multiple participants, which reduces the planner’s control over the outcome. While most men and women reported equal sharing of organizing joint activities (67% among women and 72% among men), women tend to shoulder a greater share of the load: 26% of women and 19% of men reported women usually or always handle this task, compared to only 7% of women and 9% of men reporting men handling it. These findings support prior research showing that women are more likely to handle complex tasks over which the individual has a low level of control (e.g. Daminger Citation2019).

Table 1. Percentage distribution of self-reported division of cognitive-heavy household tasks.

Women’s tendency to perform frequent cognitive tasks is also evident in our data. For example, in the division of financial decision-making tasks, women are more involved in routine purchases, with 55% of women and 44% of men noting women usually or always handle these tasks. However, deciding on large purchases is more equally shared, with over 82% of men and women reporting equal involvement.

While the frequency and complexity of cognitive tasks in our scale may vary across households and context, the distribution of responses on these items reveals important heterogeneity across couples and tasks, with substantial disagreement regarding task division across genders. For instance, about 35% of women and 32% of men reported sharing the task of ‘paying the bills/keeping financial records’ equally. However, women were substantially more likely than men to report usually or always handling it (41% vs. 33%), while men were more likely to report the opposite (33% vs. 25%). These differences, which are statistically significant, indicate potentially divergent perceptions of cognitive work associated with these tasks among men and women. Invisible cognitive work, such as organizational tasks, can be challenging for spouses to grasp.

The distribution of ‘doing small repairs’ also reveals gendered variation in perceived task division. Only about 5% of women and 3% of men reported that women always or usually handle small repairs. However, women were more likely to report equal sharing of this task (12% vs. 9%) and less likely to report men always handling it (35% vs. 52%). Similarly, women were more likely to report they usually or always handle the task of ‘deciding on social activities’ (14% vs. 9%), and men were more likely to report the opposite (6% vs. 4%).

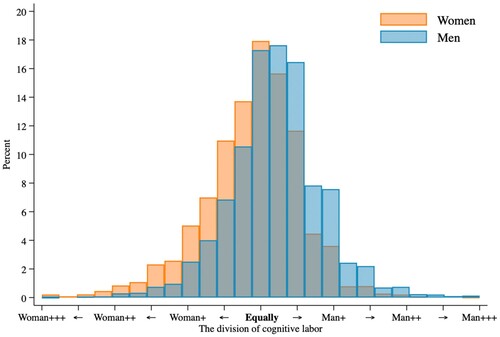

Gender differences in the self-reported division of specific cognitive tasks are reflected in the overall distribution of the division of cognitive labor scale, shown in . Both distributions center around the middle, with a heavier left tail for women and a heavier right tail for men. Men’s distribution, however, is slightly more tilted than women’s, indicating that women typically perceive the overall division of these cognitive-heavy tasks as more equally shared. Men, by contrast, reported that they do more cognitive tasks. If this is the case, and cognitive labor influences them in a similar way to women, we should observe that more men than women experience high family–work conflict. Alternatively, if men overstate their share of the cognitive work relative to women, or are less susceptible to the negative impacts of these tasks, the association between cognitive labor and family–work conflict will be stronger among women. We turn now to assessing these competing possibilities.

Cognitive labor and family–work conflict

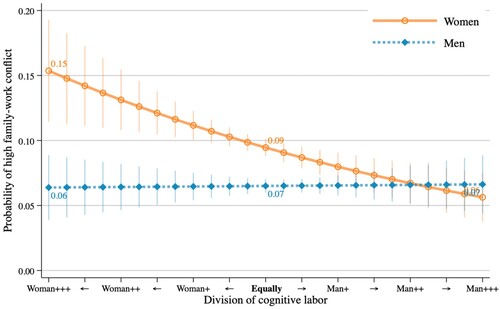

presents the results of multivariate logit models predicting family–work conflict based on the division of household cognitive labor.Footnote10 Our findings confirm that a higher cognitive labor load predicts a significant family–work conflict for women but not for men. The coefficient for cognitive labor remains similar in magnitude, direction, and statistical significance across all models, indicating the association between cognitive labor and family–work conflict is not driven by differences in the division of physical labor, by variation in individual factor and family structure, or by the respondents’ country.

Table 2. Coefficients from logit models predicting significant family–work conflict (arriving to work too tired several times a month because of household work).

Gender differences in the association between family–work conflict and the division of cognitive labor are depicted in , showing the predicted probabilities from the full models (Models 4 and 8). For women who report equally sharing cognitive-heavy tasks with their spouse, we predict a 9% probability of arriving at work too tired to function well multiple times a month. This risk increases to 15% if she reports performing all of the cognitive-heavy tasks and reduces to 6% if her spouse always performs these tasks.

Figure 3. Estimated probabilities of high family–work conflict by the division of cognitive household labor (estimated from Models 4 and 8 in )

In contrast, men have a lower predicted stress level across various divisions of cognitive labor, and this remains unchanged regardless of the load of cognitive tasks they carry. We predict that 7% of men experience family–work conflict at least once or twice a month if they report equally sharing cognitive-heavy tasks with their spouse. This risk reduces to 6% if the woman does all of the cognitive work and remains at 7% if the man reports always doing all of the work.

The results support our claim that cognitive labor affects men and women differently in terms of stress levels. Women are more than twice as likely as men with similar measured maximum cognitive labor to report high family-work conflict (15% vs. 7%). Yet, even for women who equally share cognitive labor with their spouses, the probability of experiencing high family–work conflict remains higher compared to similar men. Given that our scale of the division of cognitive labor is conservative and likely underestimates women’s share of cognitive labor, we suspect the impact on family–work conflict for women is even larger. This implies that cognitive labor could be a significant yet underappreciated factor contributing to gender inequality in the labor market.

We suspect that the gender difference in the association between cognitive labor and family–work conflict are related to the type of tasks women perform – which are more frequent and complex, are tasks over which the individual has less control, and are less rewarding – even when men and women share the overall load more equally. Indeed, the division of specific tasks among the GSS respondents, presented in , is consistent with this notion. However, due to the limited number of tasks available, and unobserved heterogeneity across households in tasks’ characteristics, we cannot directly assess this possibility with the GSS data.Footnote11 These results underscore the potential importance of cognitive labor for social stratification and highlight the need to collect appropriate data that can be used to assess these questions. The theoretical argument we outlined above provides a crucial clue about what data we should collect.

Robustness checks

We tested the robustness of our estimates in several ways (see Table A2 in the Appendix). Theoretically, our results may be driven by the specific scale construction, such as the use of the ‘small repairs’ item or the summation across equally weighted items. To evaluate these possibilities, we re-estimated our main models with several alternative scales. First, we created an alternative scale that contains the ‘shopping for food’ item, rather than the ‘small repairs’ item. The results from this analysis are nearly identical to our main results (see Figure A1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Although we predict marginally smaller probabilities for women with a high cognitive load with this scale, this does not change our main conclusions. Second, to ensure our results are not driven by variance in one specific item, we created six alternative scales, each of which omits one item from the scale, and we replicated our main models with these scales. The predicted probabilities from these models, presented in Figure A2 in the Appendix, are consistent with our main results.

An alternative strategy for capturing cognitive labor is to use factor analysis. Such a strategy assumes that the division of cognitive labor is a latent variable that can be approximated by allowing each item to load differently onto the underlying factor. To check whether our results depend on the choice of scale construction, we re-estimated our main models with factor scores instead of the additive scale. The results from the factor scores (Figure A4) and the additive scale are nearly identical and our conclusions remain unchanged.

Last, a potential limitation of our empirical investigation is the pooling of data from the 10 countries together. Although such a strategy is necessary to ensure statistical power in this case, it is nonetheless problematic because it can mask country level variation in the association between cognitive labor and family–work conflict. This variation is expected given cultural, contextual, and structural differences across countries. Moreover, given sample size disparities across countries, larger countries may exert more influence on the main effect than smaller countries. As a sensitivity analysis for these issues, we estimated another model specification that includes interactions between country and cognitive labor in our full models.Footnote12 This model allows the slope to vary by country. None of the interactions were statistically significant, and the interactions did not improve our model fit (see Models 5 & 10).

Another way to evaluate this cross-country variability is to examine variation in the bivariate association between cognitive labor and family–work conflict for each country, as presented in Figure A5 in the Appendix. The results show similar patterns in eight out of 10 countries for women (all but Georgia and Romania) and men (all but Russia and Lithuania). Together, the findings suggest that our conclusions are not driven by a single country or a small number of countries. Yet, more data is needed to fully evaluate country-level variation in these association.

In sum, alternative constructions of the cognitive labor scale and alternative model specification do not change our conclusions. There seems to be an underlying, very robust structure in regard to the division of cognitive labor and its association with family–work conflict, which we capture with all kinds of measures and models.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper contributes to a large literature in the sociology of family and gender that focuses on the consequences of the gendered division of household labor. Scholars have recently argued that this debate needs to consider cognitive labor as a distinct dimension of household labor (DeVault Citation1991; Offer Citation2014; Daminger Citation2019). Our results clearly underscore this point. The higher the share of cognitive labor women bear, the more exhausted they are at work. For men, by contrast, the relative share of (self-reported) cognitive labor is not predictive of their family–work conflict. Thus, it is important to add cognitive labor and its consequences to discussions of the consequences of inequalities within the household for gender inequalities outside the household.

Apart from adding credence to this overall claim, this paper advances the current research on the division of cognitive labor, stress, and family–work conflict in several important ways. First, most previous research on cognitive labor has analyzed the most-likely cases for studying high levels of cognitive labor, like highly educated, double-income couples (Daminger Citation2019; Robertson et al. Citation2019). Here, we show with population-level data that couples vary strongly in how they divide cognitive labor. Our measure of cognitive labor does not allow us to make inferences about the division of cognitive labor in detail. However, even given an approximation such as the one we have used here, we clearly see that couples divide this work in very different ways. If we agree that cognitive labor is important, the next big step should focus on capturing and explaining differences in the variation of this division.

Second, previous debates have focused strongly on the gendered division of the total amount of cognitive labor and have assumed that this amount is predictive of mental exhaustion. We challenge this assumption at the theoretical level. By drawing on theories of workplace stress, we argue that it is not only the total amount of cognitive labor that needs to be understood if we want to properly analyze if and why cognitive labor leads to stress and exhaustion. Rather, we need to also reflect on the characteristics of household labor tasks and relate them to the different levels of stress they may evoke. Characteristics such as frequency, complexity, control over task performance, and the acknowledgment one usually receives for completion of a task are important, well-studied predictors of the effort–reward relation in workplaces (Sperlich et al. Citation2013; Sperlich and Geyer Citation2016). We argue that, in the case of cognitive labor, the effort–reward relation is heavily skewed against women. Typically, women perform tasks which require the highest effort and for which individuals receive the lowest reward. This makes cognitive work for women especially exhausting. Such reasoning could be the starting point for digging deeper into the division of cognitive labor within couples. There are clearly different sets of cognitive tasks in the household, which we need to understand and classify.

Furthermore, any development of the theoretical association between cognitive labor and stress should also consider the gendered processes of the acknowledgment (or the lack of it) of cognitive labor. Here, we have hypothesized, based on previous qualitative evidence, that women receive less acknowledgment for this work compared to men, and that their successes in regard to cognitive labor are acknowledged much less than are their successes in regard to physical work. However, we lack data on this acknowledgment process and a deeper theoretical understanding of it. In sum, the division of household labor remains an important element in understanding exhaustion, but we clearly need to capture more than simply the overall share of the load. We need to understand who gets the lemons, and why.

Third, our results make clear that the unequal burden of cognitive labor has consequences outside the household. Here, we use information about whether persons come to work too tired to function as an indicator of family–work conflict. Gendered perceptions of promotability are strongly based on the expectation that women can be overburdened with family responsibilities (Hoobler et al. Citation2009). Arriving exhausted at work can reinforce these lower levels of promotability and could, therefore, partly explain glass-ceiling effects in the labor market. For employees, high levels of mental exhaustion can lead to a lower take-up of overtime, a higher risk of absence, and lower engagement with high-stakes projects. However, we lack a theoretical and empirical understanding of the consequences of cognitive labor-induced stress outside the household. Increasing our knowledge here could very likely help us understand gender-specific inequalities in the labor market better.

We are confident that we have used the best data available to study the connection between cognitive labor and mental exhaustion at the population level. However, these data were not designed to investigate this question. There is much room for improvement if we want better measures and more fine-grained analyses. In order to improve the measurement of cognitive labor, we need to include tasks that capture a wide range of characteristics, such as high- and low-frequency tasks, tasks with different levels of complexity, and tasks over which individuals have different levels of control. By considering such tasks specifically, we can construct a valid measure and use it to gain deeper insights into the distribution of cognitive labor and its consequences. Such measures may also allow us to trace the causes of the gendered effect of cognitive labor on stress.

Furthermore, in line with Dean et al. (Citation2021), we call for better measurement of the volume of cognitive labor, its division, the mental load involved, and household labor-related stress. Our aim here was to use the most suitable data currently at hand in order to proxy these characteristics. However, these are clearly rough approximations, with a lot of room for improvement. First, further research needs to distinguish between the volume of cognitive labor and its division. In order to do this, we need information about the frequency with which tasks are performed. Right now, we are obliged to work on the assumption that all tasks contribute similarly to the overall volume of cognitive labor. This is certainly not the case and we have made the case that high-frequency tasks, which contribute much more to the overall volume of cognitive labor, are typically performed by women. Second, we have argued that mental load and stress are two distinct concepts. Thus, they need to be measured differently. Mental load refers to the relation of cognitive capacity to cognitive demands. If the demands are constantly too high for the cognitive capacity, this can result in increased stress levels. We need to understand the circumstances within families much better, to understand when and why high levels of mental load increase stress. In order to be able to do this, we need to separate the concept of mental load from that of stress.

This article is intended to be a first step in the larger endeavor of moving toward more fine-grained analyses. The data at hand did not allow us to separate our results across subgroups. We suspect that socioeconomic status could play an important role in regard to the volume of cognitive labor, as well as its consequences. Families in poverty face very different challenges compared to economically powerful families. Managing scarce resources and selecting between an abundance of options are two very distinct cognitive challenges, and we need to understand how this relates to the division of cognitive labor and stress. Likewise, we have not been able to examine country level differences in the division of labor or the contribution of children within the family to the division of cognitive labor and exhaustion. To do this, we need larger samples, and preferably longitudinal data.

It should also be noted that our empirical analysis is tied to the division of cognitive labor within heterosexual couples. This excludes singles and same-sex couples, which are important test cases that should be further explored in future research. Singles, especially single mothers, could experience high levels of mental load, but they might also be exposed to lower levels of it compared with married mothers because they do not need to perform cognitive labor in relation to their spouse (like monitoring whether a task has been done). Gaining a better understanding of this can shed light on the importance of the absolute and relative volume of cognitive labor in the household. Same-sex couples can also provide a valuable test case to tease out the sources of the gendered division of cognitive labor in the household and its association with stress. Further quantitative research needs to find a way to include singles and same-sex couples in order to obtain a broader picture of the relation between cognitive labor and stress. Studying cognitive labor and its consequences is challenging, but it is a very worthwhile endeavor, as we hope we have shown with this study.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.3 MB)Acknowledgements

We thank the Family and Generations research group at NIDI for valuable comments on this paper and for an insightful research visit. We also thank Nicole Hiekel and Florian Schulz for comments on earlier versions of this work and all collages at the PAA 2023 (New Orleans), RC28 2022 (LSE), and BIB Turning Gold 2023 conference.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Bulgaria, Russia, Georgia, France, Romania, Belgium, Lithuania, Poland, Czech Republic, and Sweden.

2 The results of the paper can be replicated with GGS data and the syntax files (Stata) stored here: https://osf.io/rvafg/.

3 Data for Bulgaria and Russia were collected in 2004, those for France, Romania and the Czech Republic were collected in 2005, those for Georgia and Lithuania were collected in 2006, those for Belgium were collected in 2008–2010, those for Poland were collected in 2010–2011, and those for Sweden were collected in 2012–2013. We include country fixed effects to account for these differences. There is no theoretical reason to believe the underlying association between cognitive labor and stress varies across time.

4 Only 2.5% outsource the organization of joint activities, 3% outsource paying the bills and finances, 5% outsource small repairs and less than 1% of couples outsource decision-making on routine purchases, large purchases and social activities. The rate is much higher for physical labor tasks: about 8% of all couples outsource vacuum cleaning, 6% outsource doing the dishes, and 5% outsource preparing meals.

5 We only included respondents in heterosexual relationships in the analyses because of an insufficiently small number of cases of respondents in same-sex households (n = 58).

6 The additional household labor items are vacuum cleaning, washing dishes, preparing daily meals, and shopping for food. Organizing joint activities scored highest on cognitive labor as it requires substantial planning, division into subtasks, delegation, anticipation of needs and decision-making. It is also the most complex task we include, and the one over which individuals have least control, given that it involves multiple participants. The small repairs and paying bills items were ranked high because they require substantial planning, researching and monitoring (e.g. researching potential solutions and monitoring the outcomes) but are lower in complexity because they often deal with one task. They were ranked higher in regard to the level of control an individual has over them because they depend primarily on the person carrying out the task. Our scale excludes child-related tasks. Among these items, we rated ‘helping the children with homework’ as the one with the highest cognitive labor overhead. However, only parents with children older than six years were asked this item, and it had a considerable rate of non-response. Using this item would have reduced the sample size by 68%.

7 We capture two cases in the middle of the scale: couples sharing each task equally and couples specializing their work in such a way that it sums up to an equal load. Across all couples with an equally shared load, we estimate a proportion of 19% for the former type. Across all couples, their share is 3.5%. Our results do not change depending on whether we exclude this group or not.

8 The factor analyses yielded only one factor with an eigen value larger than one. As expected, the scales are highly correlated (r = 0.96). The distribution of the factor score by the additive scale is presented in the Supplementary Appendix (Figure A3).

9 In sensitivity analyses, we accounted for a potential nonlinear effect of cognitive labor and stress by including a polynomial term for the cognitive labor measure (See Models 4 and 9 in Table A2 in the Appendix). The polynomial coefficients were not significant, and the main effect for cognitive labor retains its size, direction, and significance.

10 Full estimates are available in Table A2 in the Appendix (Models 1 and 6).

11 In an auxiliary analysis (Figures A6a and A6b in the Appendix), we provide some insights into this by analyzing the association between the organizing joint activities and the financial decision-making items as potential examples for complexity and frequency. The results are consistent with our claim.

12 Ideally, we would have estimated a multilevel model that includes a random slope for cognitive labor. However, such a model is not feasible because we only have 10 countries.

References

- Bethge, M. and Radoschewski, F. M. (2012) ‘Adverse effects of effort-reward imbalance on work ability: longitudinal findings from the German Sociomedical Panel of Employees’, International Journal of Public Health 57: 797–805.

- Brown, B. A. (2022) ‘Intensive mothering and the unequal school-search burden’, Sociology of Education 95: 3–22.

- Budig, M. J. and Hodges, M. J. (2010) ‘Differences in disadvantage’, American Sociological Review 75: 705–28. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.11770003122410381593.

- Calarco, J. M., Meanwell, E., Anderson, E. M. and Knopf, A. S. (2021) ‘By default: how mothers in different-sex dual-earner couples account for inequalities in pandemic parenting’, Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 7: 237802312110387.

- Ciciolla, L. and Luthar, S. S. (2019) ‘Invisible household labor and ramifications for adjustment: mothers as captains of households’, Sex Roles 81: 467–86.

- Correll, S. J. (2001) ‘Gender and the career choice process: the role of biased self-assessments’, American Journal of Sociology 106: 1691–730.

- Daminger, A. (2019) ‘The cognitive dimension of household labor’, American Sociological Review 84: 609–33.

- Daminger, A. (2020) ‘De-gendered processes, gendered outcomes: how egalitarian couples make sense of non-egalitarian household practices’, American Sociological Review 85: 806–29.

- Dean, L., Churchill, B. and Ruppanner, L. (2021) ‘The mental load: building a deeper theoretical understanding of how cognitive and emotional labor over load women and mothers’, Community, Work & Family 25: 1–17.

- DeVault, M. L. (1991) Feeding the Family: The Social Organization of Caring as Gendered Work, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Díaz-García, J., González-Ponce, I., Ponce-Bordón, J. C., López-Gajardo, M. Á., Ramírez-Bravo, I., Rubio-Morales, A. and García-Calvo, T. (2021) ‘Mental load and fatigue assessment instruments: a systematic review’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 1–16.

- Erickson, R. J. (2011) ‘Emotional carework, gender, and the division of household labor’, in A. I. Garey and K. V. Hansen (eds.), At the Heart of Work and Family: Engaging the Ideas of Arlie Hochschild, Rutgers University Press, 61–74.

- Gaillard, A. W. (1993) ‘Comparing the concepts of mental load and stress’, Ergonomics 36: 991–1005.

- Hancock, G. M., Longo, L., Young, M. and Hancoc, P. A. (2021) ‘Mental workload’, in G. Salvendy and W. Karwowski (eds.), Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 203–26.

- Harrington, E. E. and Reese-Melancon, C. (2022) ‘Who is responsible for remembering? Everyday prospective memory demands in parenthood’, Sex Roles 86: 189–207.

- Heisig, J. P. (2011) ‘Who does more housework: rich or poor?’, American Sociological Review 76: 74–99.

- Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J. and Lemmon, G. (2009) ‘Bosses’ perceptions of family-work conflict and women’s promotability: glass ceiling effects’, Academy of Management Journal 52: 939–57.

- Johnston, D. W., Kassenboehmer, S. C. and Shields, M. A. (2016) ‘Financial decision-making in the household: exploring the importance of survey respondent, health, cognitive ability and personality’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 132: 42–61.

- Karasek, R. and Theorell, T. (1990) Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life, New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Klünder, N. (2018) ‘Zwischen selbst Gekochtem, Thermomix und Schulverpflegung: Innenansichten der Ernährungsversorgung von Familien mit erwerbstätigen Eltern’, Hauswirtschaft und Wissenschaft 11: 1–24.

- Klünder, N. and Meier-Gräwe, U. (2018) ‘Caring, Cooking, Cleaning – repräsentative Zeitverwendungsmuster von Eltern in Paarbeziehungen’, Journal of Family Research 30: 9–28.

- Kushnir, T. and Melamed, S. (2006) ‘Domestic stress and well-being of employed women: interplay between demands and decision control at home’, Sex Roles 54: 687–94.

- Lachance-Grzela, M. and Bouchard, G. (2010) ‘Why do women do the lion’s share of housework? A decade of research’, Sex Roles 63: 767–80. http://link.springer.com/10.1007s11199-010-9797-z.

- Leopold, T., Skopek, J. and Schulz, F. (2018) ‘Gender convergence in housework time: a life course and cohort perspective’, Sociological Science 5: 281–303. https://sociologicalscience.com/articles-v5-13-281/.

- Luthra, R. and Haux, T. (2022) ‘The mental load in separated families’, Journal of Family Research 34: 669–96.

- Moreno-Colom, S. (2017) ‘The gendered division of housework time: analysis of time use by type and daily frequency of household tasks’, Time & Society 26: 3–27.

- Newkirk, K., Perry-Jenkins, M. and Sayer, A. G. (2017) ‘Division of household and childcare labor and relationship conflict among low-income new parents’, Sex Roles 76: 319–33.

- Offer, S. (2014) ‘The costs of thinking about work and family: mental labor, work–family spillover, and gender inequality among parents in dual-earner families’, Sociological Forum 29: 916–36. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111socf.12126.

- Ridgeway, C. L. and Correll, S. J. (2004) ‘Unpacking the gender system’, Gender & Society 18: 510–31.

- Robertson, L. G., Anderson, T. L., Hall, M. E. L. and Kim, C. L. (2019) ‘Mothers and mental labor: a phenomenological focus group study of family-related thinking work’, Psychology of Women Quarterly 43: 184–200.

- Salmi, P. and Sonck-Rautio, K. (2018) ‘Invisible work, ignored knowledge? Changing gender roles, division of labor, and household strategies in Finnish small-scale fisheries’, Maritime Studies 17: 213–21.

- Schieman, S. and Young, M. (2011) ‘Economic hardship and family-to-work conflict: the importance of gender and work conditions’, Journal of Family and Economic Issues 32: 46–61. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007s10834-010-9206-3.

- Schober, P. S. (2013) ‘The parenthood effect on gender inequality: explaining the change in paid and domestic work when British couples become parents’, European Sociological Review 29: 74–85. https://academic.oup.com/esr/article-lookup/doi/10.1093esr/jcr041.

- Siegrist, J. and Wahrendorf, M. (2016) ‘Failed social reciprocity beyond the work role’, in J. Siegrist and M. Wahrendorf (eds.), Work Stress and Health in a Globalized Economy: The Model of Effort-Reward Imbalance, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 275–91.

- Sperlich, S., Arnhold-Kerri, S., Siegrist, J. and Geyer, S. (2013) ‘The mismatch between high effort and low reward in household and family work predicts impaired health among mothers’, The European Journal of Public Health 23: 893–98.

- Sperlich, S. and Geyer, S. (2016) ‘Household and family work and health’, in J. Siegrist and M. Wahrendorf (eds.), Work Stress and Health in a Globalized Economy: The Model of Effort-Reward Imbalance, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 293–311.

- Taniguchi, H. and Kaufman, G. (2020) ‘Sharing the load: housework, joint decision-making, and marital quality in Japan’, Journal of Family Studies 28: 1–20.

- Thébaud, S. (2010) ‘Masculinity, bargaining, and breadwinning’, Gender & Society 24: 330–54. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.11770891243210369105.

- Thébaud, S., Kornrich, S. and Ruppanner, L. (2021) ‘Good housekeeping, great expectations: gender and housework norms’, Sociological Methods & Research 50: 1186–214.

- Treas, J. and Tai, T. (2012) ‘How couples manage the household’, Journal of Family Issues 33: 1088–116.

- Tsutsumi, A. and Kawakami, N. (2004) ‘A review of empirical studies on the model of effort–reward imbalance at work: reducing occupational stress by implementing a new theory’, Social Science & Medicine 59: 2335–59.

- Vikat, A., Spéder, Z., Beets, G., Billari, F., Bühler, C., Desesquelles, A., Fokkema, T., Hoem, J. M., MacDonald, A., Neyer, G., Pailhé, A., Pinnelli, A. and Solaz, A. (2007) ‘Generations and Gender Survey (GGS)’, Demographic Research 17: 389–440.

- Weeks, A. C. (2022) The political consequences of the mental load, Working Paper.