ABSTRACT

This study examines the use of interpersonal touch by television reporters in their interactions with sources — mainly residents and government officials — before Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico. We used a qualitative approach, which allowed four functions to emerge inductively but aligned with concepts from haptics and journalistic roles research. The functions — engagement and participation, empathy and caring, easing tension, and collective empowerment are described in relation to the literature on touch across cultures. Implications for the emotional turn in journalism are discussed.

Journalists covering natural disasters and other crises are witnesses to traumatic events (Cottle Citation2013). From hurricanes to armed conflicts, journalists in these stages must face human suffering and material destruction on a frequent basis (Pantti, Wahl-Jorgensen, and Cottle Citation2012). Research examining disaster reporting has documented the ways journalists approach those scenes, as well as the psychological consequences — many studies report consequences of direct trauma, which affects their performance in the long-term (Buchanan and Keats Citation2011; Tandoc and Takahashi Citation2018). Others have researched the affirmative duty of journalists to protect human life and property before a hazard strikes (Wilkins Citation2016). An area of research that has received less attention is the nonverbal behaviors of reporters — particularly television reporters who stand in front of a camera to report these events — being displayed when performing their work.

Among the many nonverbal behaviors people use daily, touch stands out as a powerful channel of information and emotions (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013). Despite the extensive research in psychology, sociology, anthropology, and the growing study of emotions in disaster reporting, there is a dearth of research examining the use of touch by journalists.

The study of touch in journalism fits with Wahl-Jorgensen’s (Citation2020) arguments about the emotional turn in journalism studies (e.g., Beckett and Deuze Citation2016; Pantti Citation2010; Richards and Rees Citation2011). Wahl-Jorgensen (Citation2020) argues research examining journalistic production, texts, and news audience engagement are only recently turning towards a more focused analysis of the role of emotions in journalism. In tracing such scholarship, Wahl-Jorgensen places significant attention on crisis and disaster reporting as an example of emotionality in journalism, which often disregards the idealistic norm of the detached objective observer. Wahl-Jorgensen argues for appreciation of the emotional labor placed on journalists and for emotional forms of storytelling. In this study, we answer Wahl-Jorgensen’s call (Citation2020) by extending it into the realm of television disaster reporting, a context and a medium with affordances that perfectly serve the use of emotions in storytelling.

In this exploratory study we examine nonverbal communication, more specifically haptics or touch, of television reporters in their interactions with sources before Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico on September 20th, 2017. The study is theoretically grounded in journalistic role performance and haptics theory. Additionally, this study adds and extends the growing body of research on disaster reporting (e.g., Matthews and Thorsen Citation2020) and complements studies that have examined news coverage of Hurricane Maria (e.g., Davis Kempton Citation2020; Molina-Guzmán Citation2019; Nieves-Pizarro, Takahashi, and Chavez Citation2019; Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020).

Literature Review

Natural hazards such as hurricanes, wildfires, earthquakes, and tsunamis, can affect human populations around the world (Blaikie et al. Citation2014). News media play a key role in informing vulnerable populations of the risks associated with these natural hazards before, during, and after the disasters (Graber and Dunaway Citation2017). Research examining disaster reporting has expanded considerably in the last few years, examining both content and production of such content (Monahan and Ettinger Citation2018).

Journalists face a series of challenges when reporting disasters, including practical issues such as lack of access to sites or sources and personal ones such as the psychological aftermath of stressful events (Tandoc and Takahashi Citation2018). Journalists who work in different media react differently to natural disasters according to the characteristics and affordances of the media outlets. TV reporters are required to maintain their presence on the sites, as well as conducting live reporting (Wang, Lee, and Wang Citation2013). As a result, the emphasis on live reporting on site restricts journalists’ choices of the time and the place of doing their reports, while their peers who work for print news outlets are given more autonomy (Wang, Lee, and Wang Citation2013).

In this study we examine TV reporting during the pre-disaster phase (Graber and Dunaway Citation2017) of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, namely the days before the hurricane made landfall. The lack of research on touch in journalism studies, particularly in the context of disaster reporting, presents an opportunity for scholars interested in exploring the emotional turn in journalism research (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020), for touch, being both visual and tactile, can convey various emotions, even some discrete ones, to sources and audiences (Hertenstein et al. Citation2006). Emotional labor has not received much attention by journalism scholars (Hopper and Huxford Citation2017). Such scholarship could build on the also limited but relevant research on other nonverbal behaviors displayed by television reporters. Finally, it could also open a new avenue for research on ethics and objectivity since the use of touch could be perceived and construed as inappropriate or manipulative. In the next sections we review studies of television disaster reporting, television nonverbal communication, and touch and emotions, and we highlight the key theoretical concepts applied in this study.

Television Disaster Reporting

Journalism scholars examining natural disasters or natural hazards have largely focused on newspaper coverage. Few studies of natural disasters have examined television content, and fewer have focused on the nonverbal communication of broadcasters — with notable exceptions (e.g., Coleman and Wu Citation2006; Deavours Citation2020) — which partially explains the few theories and methods in visual journalism studies (Coleman Citation2010). Due to this lack of research in this area of study, we discuss related research examining disasters broadly defined, which includes man-made disasters and other crises and conflicts.

In this literature, the analysis of source use is prominent — journalists’ dependency on government sources is repeatedly observed in such studies (e.g., Hallin, Manoff, and Weddle Citation1993; Watts and Maddison Citation2014). When reporting crisis situations, journalists interview government officials for various information such as general comments, direct observations, discussion about preparedness, resources, and plans or predictions (Hornig, Walters, and Templin Citation1991; Nucci, Cuite, and Hallman Citation2009; Walters and Hornig Citation1993). In fact, the dependence on government sources increases during crisis situations such as terrorist attacks (Li and Izard Citation2003), food safety crises (Powell and Self Citation2003), and natural disasters (Walters and Hornig Citation1993). On the other hand, victims and witnesses are usually quoted for their direct observations of a disaster (Hornig, Walters, and Templin Citation1991), providing information from different perspectives. Although sources such as experts and businesspeople are also interviewed in other natural disaster scenarios, in the present study, the interaction of reporters with sources where touch was observed was only with these two types of sources, namely government officials and citizens.

Apart from the efforts put on sources, few studies about disaster coverage on television have examined visuals. Some notable exceptions point to areas for future studies. Miller and LaPoe’s (Citation2016) study about TV coverage of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill examined newscast shots to compare the usage of different visual images such as an oiled pelican, cleanup crews, and oil on land. Other disaster studies have focused on the dominant visual frames in news (e.g., Borah Citation2009; Li and Izard Citation2003; Houston, Pfefferbaum, and Rosenholtz Citation2012). There are few studies examining the interpersonal aspects of on-camera interactions between reporters and sources, and fewer have examined nonverbal communication. Below we review these studies.

Television Reporters’ Nonverbal Behaviors

Television journalists, in contrast to their peers in print media, are expected to maintain a certain physical appearance and act in particular ways when they appear in front of the camera (Houlberg and Dimmick Citation1980; Meltzer Citation2022; Nitz et al. Citation2007). This makes their engagement in nonverbal communication a unique characteristic of their jobs.

Coleman and Wu (Citation2006) examined nonverbal emotional expressions of journalists during their coverage of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States. They reported journalists showed heightened nonverbal cues (i.e., facial expressions and body language), both positive and negative, during the second eight-hour period during the first 24 h after the attack. The results are consistent with Graber and Dunaway’s (Citation2017) stages of crisis reporting. In the first stage, reporting is marked by speculations; during the second stage, journalists put things into perspective and correct errors; and in the third stage journalists place the crisis into a larger, long-range perspective and prepare to cope with the aftermath. The results reported by Coleman and Wu (Citation2006) provide implications about the practice of objectivity, the guiding norm in journalism, particularly in the United States, that suggests journalists distance themselves emotionally from the topic and their sources. The magnitude of a tragedy such as the 9/11 attacks emotionally affected those reporters. This also suggests, despite studies showing little bias in news reporting, such results appear to only apply to the content, not the delivery in the form of nonverbal behaviors.

Deavours (Citation2020) replicated Coleman and Wu’s (Citation2006) study in a different crisis context — the Sandy Hook mass shooting. The results showed that most emotional nonverbal cues appeared during the first and third stages described in the stages of crisis model (Graber and Dunaway Citation2017), which differs from results by Coleman and Wu (Citation2006) and the propositions of the model. Deavours (Citation2020) argued the seemingly contradicting results might be explained based on the differences of the characteristics of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the Sandy Hook mass shooting, with journalists having become familiar with the latter as it had been preceded by similar events (e.g., Columbine and Virginia Tech mass shootings). Deavours suggested future research should examine individual and macro-level factors as outlined by Shoemaker and Reese’s (Citation2014) hierarchy of influences model to determine what factors influence various levels of adherence to nonneutral nonverbal communication. The cultural aspect of a society, which is part of the social systems layer in the hierarchy of influences model, is considered in this study as the context. Puerto Rican journalism has not been examined in nonverbal communication research. The individual and routines levels of the hierarchy are also considered as we took into consideration gender differences and role performance, which are discussed in the theoretical considerations section.

An issue arising from these studies is how little journalists are trained to deal with emotions or emotional labor in their work. Hopper and Huxford (Citation2017) examined 18 of the highest-selling introductory news-writing textbooks and found emotional labor was not discussed explicitly or substantively. There are few if any studies looking at the roles played by touch in the context of journalism. The only references somewhat related to touch come from journalism handbooks such as this example by Hudson and Rowlands (Citation2007, 172), “Journalists are encouraged to position themselves alongside the interviewee as close as possible so they are almost touching each other.” Because of this gap in journalism scholarship, we next turn to the extensive literature on haptics across disciplines such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, and communication studies.

Touch, Affect, and Emotions

Haptics (touch) and proxemics (physical space between individuals) are two main areas of study in nonverbal communication research (Hertenstein and Weiss Citation2011). Touch has an important role among the rules of conduct used by members from the same social group. Touch behavior, such as a handshake in certain cultures, can communicate the uniqueness of a person and expresses a liking for that person. Gallace and Spence (Citation2010, 246) reviewed the literature on touch and argued that touch can provide “an effective means of influencing people’s social behaviors (such as modulating their tendency to comply with requests, in affecting people’s attitudes toward specific services, in creating bonds between couples or groups, and in strengthening romantic relationships).”

Touch can be a preferred and more effective channel for communicating certain feelings — as opposed to verbal communication — such as love and sympathy (App et al. Citation2011). In addition to the either positive or negative affective responses that touch can convey, research has also analyzed the discrete emotions communicated through touch. Research on touch explains that such forms of nonverbal communication may involve support, reassurance, appreciation, affection, empathy, and sexual attraction. Studies show stroking, patting, or just a fleeting and seemingly insignificant touch between strangers even without any verbal communication can convey powerful emotions with fair accuracy (Hertenstein et al. Citation2006; Hertenstein et al. Citation2009). The intensity and duration of these interactions also influence the perceived emotions (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013). In some cases, when the touch is sustained over longer time periods, it may send a message of inclusion (i.e., “we are together”) (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013). This research suggests touch has practical functions, which means it could be used manipulatively.

The power of touch has been documented in various studies across different social contexts and settings. For example, shoppers physically touched by student greeters evaluated the store more favorably than those who weren’t (Hornik Citation1991, Citation1992). Patients feel more relaxed and comfortable after a nurse touches them (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013). And perhaps more importantly, “if touch is perceived as an indication of interpersonal warmth, it may bring forth other related behaviors” (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013, 241). For example, a slight pat on the back could influence financial decisions, presumably due to increased sense of security (Levav and Argo Citation2010). The setting in which this takes place can influence the perception of touch (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013, 249). In private situations, touch could be misunderstood as inappropriate, intimate, or sexual. Public settings, which are common in television reporting, could avoid such misunderstandings but might introduce other issues, such as people feeling pressured to accept the touch even when they really feel uncomfortable with it.

Although research on this topic is largely based on the study of white Americans (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013), cultural differences in the use of touch and physical distance have been reported around the world (e.g., McDaniel and Andersen Citation1998; Remland, Jones, and Brinkman Citation1995). High-contact cultures include Arab/Islamic countries, Central and South America, Mediterranean countries, Southern and Eastern Europe; on the other hand, low-contact cultures include Eastern Asia (particularly Northeast Asia), Northern Europe, and North America (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013), although there is still some contradictory evidence and debate about these designations (McDaniel and Andersen Citation1998). Researchers suggest Puerto Ricans are more comfortable with touch and proximity than people from North America (Dibiase and Gunnoe Citation2004). There is limited research or evidence about the factors that explain the sources of variation. It is possible touch has common meanings across cultures, but the social norms for who can touch whom and when one can touch others probably follow localized traditions, customs, rituals, and habits (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013). Cultural differences alone do not explain touch behaviors. Other explanatory factors include climatic conditions, urban versus rural differences, and geographic variation (Hertenstein and Weiss Citation2011).

Regarding sex differences, studies repeatedly find women report more comfort with touch than men, especially same-gender touch (Hall Citation2011). However, extant research shows variations in touch behaviors between men and women Gallace & Spence, Citation2010). Other comparative studies (e.g., Remland, Jones, and Brinkman Citation1995) report male dyads touch less often than mixed-sex dyads. Overall, research on touch shows gender asymmetries in the accuracy of communicating distinct emotions via touch (Hertenstein and Keltner Citation2011) and there is no consensus of why the asymmetries exist (e.g., biological or cultural reasons).

Theoretical Considerations

Although nonverbal communication is not synonymous with emotion, in disaster situations, when people’s lives and livelihoods are on the line, touch can play a powerful emotional role beyond its functional roles. The present study explores the use of touch by journalists during television disaster reporting. The lack of prior research in this area required us to approach this study theoretically using concepts from various fields (e.g., Keutchafo, Kerr, and Jarvis Citation2020). This study is therefore grounded in theoretical considerations from haptics theory and journalistic roles.

The research on touch described above suggests that four main factors explain the use of touch as a form of nonverbal communication (Andersen Citation2011). The first one is latitude, which suggests people living in warmer latitudes are more prone to use touch (some researchers suggest that more exposed skin might explain this). Second, collectivist cultures are more open to touch. Third, gender orientation or the existence of a feminine culture has been associated with increased use of touch. Fourth, religion has been negatively associated with the use of touch.

In the case of Puerto Rico, the first and second factors would suggest a relatively high use of touch. Although Puerto Rico is a U.S. territory, its Spanish roots makes its culture closer to collectivism than the individualism that characterizes mainland United States. We are not able to determine whether these factors play a role since we have no basis for comparison, but we want to highlight them as part of the context of this study. Regarding gender orientation, the lack of prior research on the topic, and the inconsistent findings in other settings, prevent us from hypothesizing whether men or women would engage in more touch behaviors. Finally, because Puerto Ricans are fairly religious (56% identify as Catholics (Pew Research Center Citation2014)), we expect to identify some religious references in the reporting.

The haptics literature describes the following uses of touch as the most common: (1) functional touch, (2) persuasive touch and compliance, (3) liking, and (4) emotional communication (see, Hertenstein and Weiss Citation2011). Functional touch is used by certain professionals (e.g., nurses) in their professional settings. Persuasive touch has been shown to increase compliance when accompanied with a verbal request (Hertenstein Citation2011). And as mentioned above, touch could increase the liking of a communicator and communicate discrete emotions. In this study, we analyze instances of touch with these uses in consideration but also mindful that specific journalistic uses of touch require an exploratory and inductive approach. After all, functional touch varies by profession, and in journalism touch is not considered as a tool of reporting.

In this study, we insert the functions of touch described above within well-established journalistic roles. The study of journalistic roles distinguishes between role orientations and role performance, with the latter referring to the behavior of journalists (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017). Among those roles is the populist-mobilizer role, which suggests journalists try to encourage people to take self-protective behaviors or social responsibility, and which has been shown to become more prominent during crises (Klemm et al. Citation2019). Research on natural disaster coverage has also shown that journalists embrace an advocacy role (Usher Citation2009) as well as non-journalistic roles — this includes first responders, leaders, community members, among others (Tandoc and Takahashi Citation2018). In the present study we theorize, based on journalistic role performance — or what journalists do, that the use of touch in television reporting is a function of journalists’ cognitive role orientations (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017). These orientations are defined as “institutional values, attitudes, and beliefs individual journalists embrace as a result of their socialization” (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017, 125). We argue that in the context of a major natural disaster, and in a culture that is relatively open to touch behaviors, journalists will enact, via nonverbal behaviors, a hybrid role that combines the journalistic populist-mobilizer role with an empathic and caring role.

Case Study

In this study we examined touch in Puerto Rican television coverage before Hurricane Maria. Hurricane Maria was the strongest storm on record to impact the island of Puerto Rico. Days before it made landfall on September 20th, 2017, the National Weather Service predicted the hurricane would make a direct impact on the island as either a category 4 or 5. News organizations approached their coverage knowing this would be a catastrophic once-in-a-lifetime event (Rodríguez-Cotto Citation2018; Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020).

Some studies have examined the coverage of Hurricane Maria both in Puerto Rican and U.S. mainland media. Nieves-Pizarro and colleagues (Citation2019) found that Puerto Rican radio reporters had to improvise in the midst of the disaster because of inadequate technology and equipment — cellphones did not work, and few had access to satellite radios. The reporters also embraced non-journalistic roles, such as community organizers. Also examining radio, Rodríguez-Cotto (Citation2018) presented a first-person account of the excruciating labor at WAPA radio, the only news station that continued to broadcast after the total blackout. Takahashi and colleagues (Citation2020) reported about the inadequate preparedness plans of news organizations, but also the sense of solidarity that emerged after the disaster. Complementing these findings, Davis Kempton (Citation2020) reported that coverage of Hurricane Maria, both in Puerto Rican media (El Nuevo Dia) and U.S. mainland newspapers, was more political than coverage of Hurricane Harvey a few weeks earlier. The present study adds a much more nuanced examination of journalistic practices in Puerto Rico during this event by examining nonverbal interactions of journalists with sources.

Research Questions

The approach we took was exploratory and descriptive, as well as interpretative of the intentions of the use of touch by journalists. Nevertheless, the research questions and concepts analyzed were drawn from both touch research and journalism studies.

Based on the literature explored above examining journalists’ nonverbal behaviors and the use of touch across cultures around the world, we propose the following research questions:

RQ1: What type of touch did Puerto Rican television reporters use in their reporting of Hurricane Maria?

RQ2: What perceived functions did touch play during interpersonal interactions between reporters and their sources?

RQ3: Which factors (e.g., setting, gender, source type) are related to the use of touch in television reporting of an incoming natural hazard?

Method

Data Collection

To analyze the touch behaviors of Puerto Rican journalists before Hurricane Maria made landfall on September 20th, 2017, we collected television clips of two major Puerto Rican TV stations (WAPA TV and Telemundo Puerto Rico) from a local media data provider and YouTube. WAPA TV and Telemundo PR are among the television stations in Puerto Rico with the largest audiences, together with Univisión Puerto Rico (Subervi-Vélez, Rodríguez-Cotto, and Lugo-Ocando Citation2020). A previous study interviewed professionals from several Puerto Rican media outlets, including three television stations (Telemundo, WAPA TV, and WIPR) (Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020). Hence, WAPA TV and Telemundo PR were chosen in this study because of their popularity and reach in Puerto Rico and the accessibility of data.

The clips were collected from two sources. First, we purchased all available clips from a news monitoring company based in Puerto Rico (clips from stations other than WAPA TV and Telemundo were not available). We then complemented those clips with clips posted on YouTube that contained live broadcasts before landfall. We relied on the latter because the news monitoring company lost power during the hurricane and was unable to record all broadcasts. Except for four clips from September 18th, 2017 provided by the news monitoring company, all the other clips we analyzed in this study were broadcasted on September 19th, 2017, one day before the landfall. All television stations were off-air for weeks after landfall on September 20th, 2017 (Subervi-Vélez, Rodríguez-Cotto, and Lugo-Ocando Citation2020). As a result, this study only examines the first stage of disaster coverage (Graber and Dunaway Citation2017), as the hurricane had not interrupted the availability of television to broadcast yet. Considering the comparatively limited size of data, we chose to conduct our analysis with all the clips we had acquired.

Interview segment was chosen to be the unit of analysis, for each interview that links a statement to a source is a discrete unit which is already available for investigation (Walters and Hornig Citation1993), enabling the examination of journalists’ behavior with sources. The inclusion criterion was that the reporter and source had to be in the same location. In total, we reviewed in a first stage 72 individual clips (34 from WAPA, 46 from Telemundo), representing more than 5 h and 47 min of pre-Maria television coverage content. The final analysis was conducted on 20 television reports where we observed interpersonal touch behaviors between the reporter and the source.

Data Analysis

The study used a qualitative thematic analysis (Fields Citation1988). A quantitative content analysis would not have allowed to capture the nuances in the behaviors, and the sample size is too small for any meaningful statistics. Four coders were involved in a first preliminary round of coding, with three of them being native Spanish speakers (including one former Puerto Rican journalist). The analysis generally followed the tenets of consensual qualitative research (Hill et al. Citation2005; Hill, Thompson, and Williams Citation1997). This method allows several researchers to examine data and come to consensus about their meaning. This approach reduces any biases inherent with single coder studies; it also maximizes the use of the wisdom of judges (Hill et al. Citation2005).

An open coding process with note taking during the viewing of each clip was used to identify each instance of touch and generally describe the setting in which it took place. This inductive process generated a first round of codes after discussions among the coders, particularly regarding the contextual background, cultural nuances, and journalistic practices of individual reporters present in the clips. This was possible mainly because of the experience and knowledge of the Puerto Rican coder, who has years of experience as a television reporter.

After the first round of analysis, two coders conducted a second round of coding on the 20 clips with touch behaviors. Two coders took care of this round because there was no more need for contextualizing the coverage, which was done in the first stage. In this second round of coding the coders identified the functions of journalistic touch behaviors in the context of a severe natural disaster using a theme development method, which is similar to what was used by Tucker-McLaughlin and Campbell (Citation2012), namely immersion into the content. While Tucker-McLaughlin and Campbell (Citation2012) tried to achieve immersion by viewing the video content and the transcripts multiple times before locking down certain images and words, in this study we did not have any transcript to read. Instead, we immersed ourselves into the very parts of touch behaviors by watching the related interviews multiple times until we came up with at least one particular function for each touch behavior. In this round of coding, the interview sites, time labels of actions, and action descriptions were taken down in detailed notes, as well as the names and identities of the reporters and sources. For a better understanding of the context of each interview, the identities of sources (e.g., government official, victim, business owner, etc.) were also coded.

After touch behaviors shown in individual video clips had been coded, the researchers analyzed and categorized the primary codes within the four functional uses of touch described in the haptics literature, specifically, functional touch, persuasive touch, liking, emotional communication, and compliance (see, Hertenstein and Weiss Citation2011). We also present their associated communicative meanings and intentions, which will be presented and discussed in the following section.

Results and Discussion

The first research question focused on how touch was used by reporters. Most of the instances of touching were just a tap on the shoulder or a hand on an arm. In some instances, those interactions lasted several seconds. All the instances of touch involving a reporter were initiated by them. This suggests a clear power dynamic, where the reporters hold the upper hand and dictate, without saying it, who is allowed to touch.

Regarding the second research question, the results show that the factors related to the use of touch in television reporting of a disaster include type of source, gender, and setting. More specifically, these behaviors appear to vary depending on the social and environmental context, as well as the standing of the source (e.g., government official). Journalists engaged in touch behaviors largely with residents that were vulnerable. This rarely happened with an official source (with a few exceptions of a handshake or a quick tap on the arm to end an interview). Both men and women engaged in touching behaviors with no clear pattern. Although prior research suggests men more frequently touch women, the same research suggests women are more comfortable with touch (e.g., Hall Citation2011). In this study, women touched more frequently, and for a longer time, but there were also more women reporters covering the hurricane. More research is needed to make definitive conclusions about the relationship between gender and the use of touch by journalists.

Location also appeared to play a role. Reporters used touch more often in public spaces (e.g., shelters, outdoor settings, commercial places), as opposed to private spaces (e.g., people’s homes).

Regarding the third research question, the results show that reporters used touch for four goals/functions, all of which aligned with previous research about emotions in journalism and touch behaviors across cultures. The analysis of the news clips of the coverage of Hurricane Maria revealed four functions (RQ3) that serve as structure to the results below and discussion section. The functions — engagement and participation, empathy and caring, easing tension, and collective empowerment — emerged inductively and are discussed here in relation to the concepts and touch functions in the literature discussed above. We use a thick description below to illustrate the functions, which are not mutually exclusive. Some interactions described here show the overlap of the functions described. The functions are described in the spatial and social context where touching took place.

Finally, WAPA TV and Telemundo PR covered the hurricane similarly based on content. The focus on evacuation, preparation, and governmental response dominated the stories, which was expected of the pre-disaster stage of the coverage (Graber and Dunaway Citation2017). There was a slight difference on how the reporters approached their sources, with WAPA TV reporters engaging in more touch behaviors than their counterparts at Telemundo PR.

Persuasive Touch and Compliance: Engagement/Participation

The first theme we identified relates to a practical aspect of touch. Reporters in our sample used touch to signal interviewees their intent to interview them or to let them know that the interview had concluded. This is a form of engagement with the sources and an unequivocal signal of who gets to participate in the television space.

In one clip, a female reporter reporting from the Puerto Rico Convention Center in San Juan, which was being used as a shelter, explained the dire conditions that many evacuees were experiencing. People did not have food and the air conditioning was not functioning, making the place hot and uncomfortable. The reporter first interviewed a young man, who was complaining about the lack of food being offered by the authorities. In this scene, several other evacuees surrounded the reporter and the man being interviewed. In an effort to hear from more people, the reporter took two steps to her left and grabbed a woman from her shoulder and brought her closer to her, effectively ending the conversation with the man (). The woman being interviewed looked at the man to make sure he was finished saying what he wanted to say. At this point the reporter kept her hand on the woman’s arm for eight seconds. The scene is tense with many people showing agitation and discomfort. They are motioning with their hands and voicing their grievances. The physical connection between the reporter and the woman clearly communicated to the woman and to those around her that the reporter wanted to only speak to the woman at that moment. The reporter used touch as a tool to signal the order of the interviews and to try to ease the tension as several evacuees were present trying to voice their concerns.

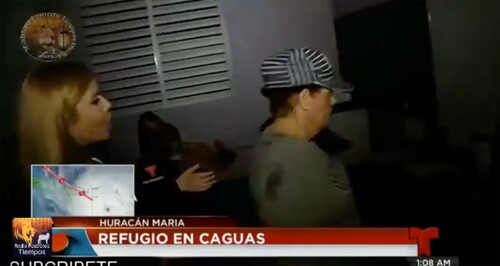

Four other reporters used the same tactic to start or end an interview. One of them, a young female reporter, was talking with evacuees at a shelter in the city of Caguas that had no electricity. After an interview, the reporter approached a woman, who started walking away from her, at which point the reporter reached out and grabbed her by the back while saying to the camera, “Esta señora se está corriendo de mí ahora mismo” (This lady is running away from me right now) (). In this way, she succeeded in having the woman engage in an interview. The interview ended with a touch on the arm, which both signaled the conclusion of the conversation as well as a form of appreciation for her time and participation.

The practical aspect of touch has been documented in a variety of contexts and professions, such as barbers, hairdressers, dentists, nurses, coaches, surgeons, and a variety of other jobs engaged in touch to perform their functions (Andersen Citation2011). In the case of journalists, the functions of engagement and participation with news sources could be conceptualized in a similar way. In contexts of disaster reporting and particularly in crowded spaces, touch serves a powerful function to unequivocally communicate engagement.

Emotional Communication: Empathy and Caring

Some clips presented reporters showing concern, empathy, and even care towards their source. This was particularly manifest when the sources were in environments that appear in a state of precariousness or danger, such as shelters full of people and homes with no electricity or other emergencies. These sources also appeared to be vulnerable (e.g., older adults) to the impending hurricane.

In one clip, a middle-aged male reporter was reporting from a school being used as a shelter. Here, he interviewed a woman, who started talking about the fragility of her house, a result of the impacts of Hurricane Irma just two weeks earlier. Her concern was that Hurricane Maria would destroy her house. Despite the seriousness of the situation and the concern expressed by the woman, the tone of the conversation did not match the words being said. The interview was fairly casual, even upbeat. The woman appeared to be using that perceived cheerfulness as a coping mechanism. However, at the end of the interaction, the reporter placed his hand on the woman’s arm and said, “Espero esté segura aquí” (I hope you are safe here). This expression of concern, coupled with the touch on the arm, ended the interview in a slightly more somber tone.

In another clip, a middle-aged female reporter visits a small convenience store and interviews the workers and customers. Many sources are older women buying supplies to weather the storm. In all of the interactions with these older women, the reporter uses diminutives such as “chiquitita” (little one) and “casita” (little house), a typical way of talking to children or older adults as a way to show care, compassion, and empathy. In one interview, the reporter leans close to a woman and puts her hand on her back while asking questions about the safety measures she is taking. It is a demonstration of support and care towards a vulnerable person ().

Although the focus of the study is on journalists’ use of touch, it is worth mentioning that some sources engaged in similar nonverbal communication. Typically, these were government sources, particularly then Governor of Puerto Rico Ricardo Rosello, as well as mayors of towns coordinating evacuation efforts. In one clip, a reporter followed the governor and a mayor as they walked across a vulnerable town, urging people to evacuate. In one scene, the two government officials engaged in a compassionate embrace with a grandmother who was concerned for her safety and the safety of her home. This emotional and dramatic piece of television news, broadcasted across the island and beyond, likely served the government as an effective show of leadership and empathy, as well as a clear message that evacuation was necessary in places across the island.

Glück (Citation2016, 901) argues, “To guarantee a qualitative and ethically sensitive news coverage, television journalists by and large require skills of empathic perception and understanding in their daily work.” This has two functions: first, to establish a relationship of trust with sources, which can allow the reporter to figure out what happened during the news events, and second, to engage in an “imaginary empathy” with the audience based on cognitively and emotionally produced news coverage. In the examples described above, both reporters and sources engaged in behaviors that fit skills mentioned by Glück — the news protagonists demonstrated their empathy and care for those vulnerable by not only listening to them, but by placing a hand on the back or engaging in an embrace (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013).

In addition, Glück (Citation2016) explains a dimension of empathy labeled instrumental-strategic function, which includes creating cooperation between journalists and sources, particularly in conflicts and traumatic scenarios. This dimension of empathy also fits the functional role of touch described in the first theme above.

Liking: Creating a Casual Mood, or Easing Tension

The mood among a population the day before a category 5 hurricane makes landfall is one of worry and tension. The coverage from both WAPA TV and Telemundo generally had this tone. This made the theme of easing tension rare and therefore noteworthy. Only one clip in our sample used touch to communicate a sense of normalcy during a once-in-a-lifetime event.

The hours before Hurricane Maria made landfall, all commerce was closed, and most roads were empty. In the midst of this calm before the storm, a WAPA TV reporter visited a Chinese restaurant that was still serving customers, the only one in the municipality of Naguabo. The reporter first approached two young men, possibly teenagers, who were waiting for their order. The reporter first patted a teenager on the back and then shook hands and exchanged a few laughs, just like friends would do at a local restaurant (). The attitude of all three (also the restaurant workers), the way of talking, and the body language didn’t match the urgency of the situation. All businesses were ordered to close hours earlier, but this establishment and its patrons were acting unconcernedly. The light-hearted report dramatically contrasted with the urgency of most of the coverage throughout that day.

Figure 4. A male reporter casually puts his hand on the back of a young man before shaking another man’s hand.

Graber and Dunaway (Citation2017) suggest when a crisis or a disaster is in its first stage, impending or having just struck, media outlets, as the main providers of information, help coordinate public activities and calm the population. Graber and Dunaway (Citation2017) argued that even if the information contains bad news, it still lowers the uncertainty and mollifies the public, as they can see or listen to familiar media professionals and get a sense of vicariously participating in the event. In our observation, we argue that apart from this mechanism of providing information, decreasing uncertainty, and offering familiarity and participation, it seems journalists can calm the audience in a more direct way when they are seen exchanging everyday nonverbal behaviors with people in the live coverage of an incoming disaster. This calming effect was best embodied when one of the journalists was seen touching young customers in a friendly, light-hearted manner less than 24 h before the dramatic landfall of a category 5 hurricane.

Mobilizer: Collective Empowerment

An incoming disaster requires governments and residents to be prepared to face a difficult scenario. A way to prepare for this is to create a sense of resilience through collective empowerment. The clips we analyzed showed a few examples of this collective empowerment by reporters through words and touch.

A young female reporter from WAPA TV provided various reports throughout the day on September 19th, 2017 from the island of Vieques. In one of her reports, she sat down with a man on a bed in a shelter. The close-up shot was intimate, as both were sitting close to each other. Despite being in a crowded shelter, we only see them. During the interview, the reporter asked about the conditions in the shelter, while moving her hand from the man’s arm to his shoulder for approximately 30 s (). Even when the shot was close-up on the man’s face, the reporter’s hand was still visible on his arm. At one point, the man said, “Tenemos que seguir pa’ lante por nuestro país” (We need to go forward for our country), — an expression of patriotism. The reporter reacted by lifting her hand up, looking down at his hand, and shaking it in agreement (), an explicit sign of both welcoming the expression of patriotism and motivating the person to get involved in the recovery of the country. The reporter then said “Estamos todos juntos en esto” (We are all in this together) and “Somos familia” (We are family). This interaction and the effusive handshake are a form of empowerment and strength in the face of the impending disaster. The tone of the conversation was casual; the close-up camera angle, the proximity to each other, the perceived familiarity between the two, and the long physical contact made the scene emotionally expressive and engaging — like two friends having a pleasant conversation. This type of interaction was not common and appears to be part of the reporting style of this reporter. Additional research is needed to determine whether there are differences between men and women in the acceptability of this type of interaction.

Earlier research in nonverbal communication described the concept of immediacy as behaviors that indicate greater closeness or liking. This research establishes various signals that distinguish a positive evaluation of an interaction partner from a negative one. This includes more forward lean, closer proximity, more eye gaze, more direct body orientation, and more touching, among others (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013). The clip described above showcased many of these signals, demonstrating a positive evaluation of the source by the reporter and an effort to create rapport. It also aligns with Hudson and Rowlands (Citation2007) recommendation to television reporters to sit as close as possible to a source, almost touching them.

In another report from the shelter in Vieques, the same reporter brings back the theme of family. In this instance, she walks between bunk beds before picking up a toddler (there are no adults in the frame) and saying, “Hay buenas familias aquí” (Good families are here). She then kisses the toddler on the cheek and then askshim to please stop crying while she is putting him down (). This report tries to communicate the family environment that reigns in the shelter, one in which the reporter is one more member of a big family of Puerto Ricans. This clip exemplifies the concept of collective bonding.

This theme is also seen in other interactions of the reporter during the day before landfall. When the reporter and sources exchanged phrases, such as “Vamos pa’ delante” (Let’s move forward) and “Hay que estar juntos como pueblo” (Let’s be together), a handshake or a hand on an arm would accompany and typically end the interview. These words of encouragement, used together with touch, were used as a form of assurance and reaffirmation that together the people of Puerto Rico will overcome adversity.

Conclusions

This study examined the work of Puerto Rican television journalists in the days before Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico. The results of the study add a new dimension to the understanding of the role of emotion in journalism (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020) by exploring touch, a particular form of nonverbal communication.

Pantti (Citation2010) states emotionality of news coverage comes from the emotional states of the sources, emotionally engaging images, and emotional topics. The clips analyzed in this study contain all these attributes. We argue the use of touch by the reporters heightened the emotional state of the sources, which, in return, resulted in these set of interviews. Similarly, the use of touch created more emotionally engaging images to an audience preparing for an incoming disaster. This is aligned with Wahl-Jorgensen’s (Citation2020) arguments about the function of emotion in at least two of the three areas she highlighted: journalistic production and news audience engagement. Wahl-Jorgensen (Citation2020, 175) suggests “audiences are more likely to be emotionally engaged, recall information and take action when news stories are relatable.” The use of touch has the potential to make news stories more relatable to audiences facing the same life-changing challenges as the sources in the news.

This study complements and expands the scant research on nonverbal communication of television reporters (e.g., Coleman and Wu Citation2006; Deavours Citation2020). Results show that the main touch functions reported in haptics literature, specifically persuasive touch and compliance, liking, and emotional communication (Hertenstein and Weiss Citation2011), were also present during television reporting of Hurricane Maria. We highlighted unique aspects of these functions in the context of television reporting, such as the use of touch to persuade people to be interviewed, or to show empathy to those who are at risk as a form of emotional communication. The effectiveness of the use of touch was also in part due to its pairing with verbal communication, which is consistent with past haptics research. In addition, we found that reporters used touch to try to create a sense of collective empowerment and unity by letting people express their views more easily and mobilize them to get involved, a function aligned with the populist-mobilizer role in journalism (Weaver and Wilhoit Citation2020). Other journalistic roles such as disseminator and interpreter were present but not clearly associated with the use of touch, while the advocacy role was not identified in any of the clips. Usher (Citation2009) reported that in New Orleans, journalists embraced an advocacy role during the post-disaster stage, so the findings in the present study suggest that role enactments could therefore change during each of the stages of crisis reporting (Graber and Dunaway Citation2017). More research is needed to determine if there is an association between journalistic roles and the use of touch during the different stages of a crisis. In addition, role enactments could be analyzed in the content of the stories to explore how they change before and after a disaster.

Research on touch points to four main factors related to this behavior: latitude, collectivism, gender orientation (feminine culture), and religion. The use of touch was not widespread in this study, but it is not possible to state if it is higher compared to other cultures. Further comparative research could elucidate this point. Regarding gender orientation, the results of the study do not provide a clear explanation of gender differences. Finally, there is limited evidence of the role of religion in touch behavior in this study. Religiosity is correlated to touch avoidance (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013), and in our sample faith and God were prominently cited. Puerto Ricans are fairly religious with 56% identifying as Catholics, but the island is nevertheless less Catholic than most other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (Pew Research Center Citation2014). Further comparative research could explore differences in touch behaviors by reporters based on religiosity of countries.

Results also point towards some ethical considerations worth discussing and examining more in-depth. For instance, where is the line between demonstrating empathetic behavior and crossing the line, particularly when reporters hold a position of power in most interviews (the exception being sources in position of power, such as government officials)? This is particularly relevant in cultures where personal space and awareness of sexually inappropriate behavior are salient. This applies similarly to questions about the appropriateness of touching children, particularly without consent. Similarly, it could be argued that such touch behaviors and other nonverbal communication such as proxemics and kinesics violate journalistic norms such as objectivity. Objectivity as a principle and concept is widely debated in journalism studies as both a guiding principle as well as a problematic concept (see, McNair Citation2017), but more importantly, its use outside mainstream media in the United States and other national contexts varies (Donsbach and Klett Citation1993; Hanitzsch et al. Citation2011; Weaver Citation1998). Although we focused on a U.S. territory, the cultural norms are distinct from the mainland, so it would be necessary to explore how perceptions of objectivity different from those in the west are relevant to how journalists perceive their touch behaviors as appropriate or not.

Prior research examining touch in a variety of settings shows even a slight touch can have a positive affective response (Knapp, Hall, and Horgan Citation2013). The positive effect that touch creates allowed Puerto Rican journalists to engage with sources who appeared hesitant of interacting in front of a camera. Therefore, touch could be used in television reporting of disasters and other crises as a functional device for effectively and systematically recruiting and encouraging sources to be emotional during the interview process. There is unfortunately a gap in journalism training that would need to be filled by incorporating clearer and more explicit discussions and exercises on nonverbal communication, something currently missing in journalism curriculum (e.g., Hopper and Huxford Citation2017). Journalists appear to be untrained in how to manage their emotions to remain objective, which could have a negative effect on their well-being, but they are also not explicitly asked to completely suppress such emotions. The tension between objectivity and emotion and affect is a barrier for the emotional turn in journalism (Pantti Citation2010; Richards and Rees Citation2011) and disaster reporting (Wilkins Citation2016). Richards and Rees (Citation2011) argue that the capacity for emotional reflexibility among journalists needs to be deployed in both practice and training. In this regard, the turn to emotion-infused affective reporting could also incorporate the role of touch and other nonverbal communication behaviors in such reporting — this is an opportunity for journalism to remain competitive, critical, and independent in a future where the information environment will become even more crowded than today (Beckett and Deuze Citation2016).

Finally, we hope this study opens a door in the field of emotions in journalism studies to a sub-area of research examining the power of touch and other forms of nonverbal communication behaviors in television reporting, both from the perspective of content production to the ways in which audiences engage with such interpersonal interactions. This work should be expanded to other areas, such as war reporting.

This study is not devoid of limitations. First, the sample we analyzed is small and covers only two days before landfall. Future research could examine the prevalence of the four functions in the television coverage of other similar natural disasters with larger samples and in the post-disaster coverage. Reporters witnessing the destruction done by a natural disaster might engage in more empathic touch behaviors with sources who might have lost loved ones or property, something that would be consistent with non-journalistic roles journalists have embraced and exhibited after a disaster (Tandoc and Takahashi Citation2018). This could allow the use of other methods for larger samples, such as content analysis; then comparisons across cultures and media systems (both internationally and intranationally). Second, some of the behaviors observed here could be attributed to the reporters’ personal style. Future research could examine the touch behavior of these and other reporters and news media in non-disaster coverage, as well as conduct interviews with them to understand their motivations. Additionally, we examined journalists use of touch, but sources and other actors in the stories also engaged in this behavior —mostly among them and not towards the reporters — an area of research that could expand journalistic understandings of the roles of sources in news coverage of disaster (most studies only examine the type of source, e.g., official sources, business sources, affected residents, or scientists). Finally, research could examine how sources react to touch and how audiences engage with the affective and emotional depictions involving touch (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020), particularly the effects touch behaviors have on audiences’ perceptions of the credibility and trustworthiness of reporters, as well as on the potential to mobilize during disasters.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersen, P. A. 2011. “Tactile Traditions: Cultural Differences and Similarities in Haptic Communication.” In The Handbook of Touch: Neuroscience, Behavioral, and Health Perspectives, edited by M. J. Hertenstein and S. J. Weiss, 351–372. Springer Publishing Company. New York.

- App, B., D. N. McIntosh, C. L. Reed, and M. J. Hertenstein. 2011. “Nonverbal Channel use in Communication of Emotion: How may Depend on why.” Emotion 11 (3): 603.

- Beckett, C., and M. Deuze. 2016. “On the Role of Emotion in the Future of Journalism.” Social Media + Society 2 (3): 2056305116662395.

- Blaikie, P., T. Cannon, I. Davis, and B. Wisner. 2014. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People's Vulnerability and Disasters. New York: Routledge.

- Borah, P. 2009. “Comparing Visual Framing in Newspapers: Hurricane Katrina Versus Tsunami.” Newspaper Research Journal 30 (1): 50–57.

- Buchanan, M., and P. Keats. 2011. “Coping with Traumatic Stress in Journalism: A Critical Ethnographic Study.” International Journal of Psychology 46 (2): 127–135.

- Coleman, R. 2010. “Framing the Pictures in our Heads: Exploring the Framing and Agenda-Setting Effects of Visual Images.” In Doing News Framing Analysis, edited by J. A. Kuypers and P. D'Angelo, 233–261. New York: Routledge.

- Coleman, R., and H. D. Wu. 2006. “More Than Words Alone: Incorporating Broadcasters’ Nonverbal Communication Into the Stages of Crisis Coverage Theory—Evidence from September 11th.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 50 (1): 1–17.

- Cottle, S. 2013. “Journalists Witnessing Disaster.” Journalism Studies 14 (2): 232–248.

- Davis Kempton, S. 2020. “Racialized Reporting: Newspaper Coverage of Hurricane Harvey vs. Hurricane Maria.” Environmental Communication 14 (3): 403–415.

- Deavours, D. 2020. “Written All Over Their Faces: Neutrality and Nonverbal Expression in Sandy Hook Coverage.” Electronic News 14 (3): 123–142.

- Dibiase, R., and J. Gunnoe. 2004. “Gender and Culture Differences in Touching Behavior.” The Journal of Social Psychology 144 (1): 49–62.

- Donsbach, Wolfgang, and Bettina Klett. 1993. “Subjective Objectivity. How Journalists in Four Countries Define a key Term of Their Profession.” Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) 51 (1): 53–83.

- Fields, E. E. 1988. “Qualitative Content Analysis of Television News: Systematic Techniques.” Qualitative Sociology 11 (3): 183–193.

- Gallace, A., and C. Spence. 2010. “The Science of Interpersonal Touch: An Overview.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 34 (2): 246–259.

- Glück, A. 2016. “What Makes a Good Journalist?” Journalism Studies 17 (7): 893–903.

- Graber, D. A., and J. Dunaway. 2017. Mass Media and American Politics. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press.

- Hall, J. A.. 2011. “Gender and Status Patterns in Social Touch.” In The Handbook of Touch: Neuroscience, Behavioral, and Health Perspectives, edited by M. J. Hertenstein and S. J. Weiss, 329–350. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Hallin, D. C., R. K. Manoff, and J. K. Weddle. 1993. “Sourcing Patterns of National Security Reporters.” Journalism Quarterly 70 (4): 753–766.

- Hanitzsch, T., F. Hanusch, C. Mellado, M. Anikina, R. Berganza, I. Cangoz, M. Coman, et al. 2011. “MAPPING JOURNALISM CULTURES ACROSS NATIONS.” Journalism Studies 12 (3): 273–293.

- Hanitzsch, T., and T. P. Vos. 2017. “Journalistic Roles and the Struggle Over Institutional Identity: The Discursive Constitution of Journalism.” Communication Theory 27 (2): 115–135.

- Hertenstein, M. J. 2011. “The Communicative Functions of Touch in Adulthood.” In The Handbook of Touch: Neuroscience, Behavioral, and Health Perspectives, edited by M. J. Hertenstein, and S. J. Weiss, 299–328. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Hertenstein, M. J., R. Holmes, M. McCullough, and D. Keltner. 2009. “The Communication of Emotion via Touch.” Emotion 9 (4): 566.

- Hertenstein, M. J., and D. Keltner. 2011. “Gender and the Communication of Emotion via Touch.” Sex Roles 64 (1): 70–80.

- Hertenstein, M. J., D. Keltner, B. App, B. A. Bulleit, and A. R. Jaskolka. 2006. “Touch Communicates Distinct Emotions.” Emotion 6 (3): 528.

- Hertenstein, M. J., and S. J. Weiss. 2011. The Handbook of Touch: Neuroscience, Behavioral, and Health Perspectives. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Hill, C. E., S. Knox, B. J. Thompson, E. N. Williams, S. A. Hess, and N. Ladany. 2005. “Consensual Qualitative Research: An Update.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 52 (2): 196–205.

- Hill, C. E., B. J. Thompson, and E. N. Williams. 1997. “A Guide to Conducting Consensual Qualitative Research.” The Counseling Psychologist 25 (4): 517–572.

- Hopper, K. M., and J. Huxford. 2017. “Emotion Instruction in Journalism Courses: An Analysis of Introductory News Writing Textbooks.” Communication Education 66 (1): 90–108.

- Hornig, S., L. Walters, and J. Templin. 1991. “Voices in the News: Newspaper Coverage of Hurricane Hugo and the Loma Prieta Earthquake.” Newspaper Research Journal 12 (3): 32.

- Hornik, J. 1991. “Shopping Time and Purchasing Behavior as a Result of in-Store Tactile Stimulation.” Perceptual and Motor Skills 73 (3): 969–970.

- Hornik, J. 1992. “Tactile Stimulation and Consumer Response.” Journal of Consumer Research 19 (3): 449–458.

- Houlberg, R., and J. Dimmick. 1980. “Influences on TV Newscasters’ on-Camera Image.” Journalism Quarterly 57 (3): 481–485.

- Houston, J. B., B. Pfefferbaum, and C. E. Rosenholtz. 2012. “Disaster News.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 89 (4): 606–623.

- Hudson, G., and S. Rowlands. 2007. The Broadcast Journalism Handbook. London: Routledge.

- Keutchafo, E. L. W., J. Kerr, and M. A. Jarvis. 2020. “Advanced Practice Nurses in Primary Care in Switzerland: An Analysis of Interprofessional Collaboration.” BMC Nursing 19 (1): 1–13.

- Klemm, C., E. Das, and T. Hartmann. 2019. “Changed Priorities Ahead: Journalists' Shifting Role Perceptions When Covering Public Health Crises.” Journalism 20 (9): 1223–1241.

- Knapp, M. L., J. A. Hall, and T. G. Horgan. 2013. Nonverbal Communication in Human Interaction. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Levav, J., and J. J. Argo. 2010. “Physical Contact and Financial Risk Taking.” Psychological Science 21 (6): 804–810.

- Li, X., and R. Izard. 2003. “9/11 Attack Coverage Reveals Similarities, Differences.” Newspaper Research Journal 24 (1): 204–219.

- Matthews, J., and E. Thorsen. 2020. Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McDaniel, E., and P. A. Andersen. 1998. “International Patterns of Interpersonal Tactile Communication: A Field Study.” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 22 (1): 59–75.

- McNair, B. 2017. “After Objectivity?” Journalism Studies 18 (10): 1318–1333.

- Meltzer, K. 2022. “Anchors and Television Presenters.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by T. P. Vos, F. Hanusch, D. Dimitrakopoulou, M. Geertsema-Sligh, and A. Sehl. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0250

- Miller, A., and V. LaPoe. 2016. “Visual Agenda-Setting, Emotion, and the BP oil Disaster.” Visual Communication Quarterly 23 (1): 53–63.

- Molina-Guzmán, I.. 2019. “The gendered racialization of Puerto Ricans in TV news coverage of Hurricane Maria.” In Journalism, Gender & Power, edited by C. Carter, L. Steiner, and S. Allan, 331–346. New York: Routledge.

- Monahan, B., and M. Ettinger. 2018. “News Media and Disasters: Navigating old Challenges and new Opportunities in the Digital age.” In Handbook of Disaster Research, edited by H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, and J. Trainor, 479–495. Cham: Springer.

- Nieves-Pizarro, Y., B. Takahashi, and M. Chavez. 2019. “When Everything Else Fails: Radio Journalism During Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.” Journalism Practice 13 (7): 799–816.

- Nitz, M., T. Reichert, A. S. Aune, and A. V. Velde. 2007. “All the News That's fit to see? The Sexualization of Television News Journalists as a Promotional Strategy.” Journal of Promotion Management 13 (1-2): 13–33.

- Nucci, M. L., C. L. Cuite, and W. K. Hallman. 2009. “When Good Food Goes Bad.” Science Communication 31 (2): 238–265.

- Pantti, M. 2010. “The Value of Emotion: An Examination of Television Journalists’ Notions on Emotionality.” European Journal of Communication 25 (2): 168–181.

- Pantti, M., K. Wahl-Jorgensen, and S. Cottle. 2012. Disasters and the Media. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Pew Research Center. 2014. Religion in Latin America: Widespread change in a historically Catholic region. (Accessed 03/25/2021) https://www.pewforum.org/2014/11/13/religion-in-latin-america/#religious-affiliations-of-latin-americans-and-u-s-hispanics.

- Powell, L., and W. R. Self. 2003. “Government Sources Dominate Business Crisis Reporting.” Newspaper Research Journal 24 (2): 97–106.

- Remland, M. S., T. S. Jones, and H. Brinkman. 1995. “Interpersonal Distance, Body Orientation, and Touch: Effects of Culture, Gender, and age.” The Journal of Social Psychology 135 (3): 281–297.

- Richards, B., and G. Rees. 2011. “The Management of Emotion in British Journalism.” Media, Culture & Society 33 (6): 851–867.

- Rodríguez-Cotto, S. 2018. Bitácora de una Transmisión Radial. San Juan, PR: Trabalis Editores.

- Shoemaker, P., and S. Reese. 2014. Mediating the Message in the 21st Century: A Media Sociology Perspective. New York: Routledge.

- Subervi-Vélez, F. A., S. Rodríguez-Cotto, and J. Lugo-Ocando. 2020. The News Media in Puerto Rico: Journalism in Colonial Settings and in Times of Crises. New York: Routledge.

- Takahashi, B., Q. Zhang, and M. Chavez. 2020. “Preparing for the Worst: Lessons for News Media After Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.” Journalism Practice 14 (9): 1106–1124.

- Tandoc, E. C., and B. Takahashi. 2018. “Journalists are Humans, Too: A Phenomenology of Covering the Strongest Storm on Earth.” Journalism 19 (7): 917–933.

- Tucker-McLaughlin, M., and K. Campbell. 2012. “A Grounded Theory Analysis.” Electronic News 6 (1): 3–19.

- Usher, N. 2009. “Recovery from Disaster.” Journalism Practice 3 (2): 216–232.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2020. “An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 175–194.

- Walters, L. M., and S. Hornig. 1993. “Profile: Faces in the News: Network Television News Coverage of Hurricane Hugo and the Loma Prieta Earthquake.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 37 (2): 219–232.

- Wang, B. Y., F. L. Lee, and H. Wang. 2013. “Technological Practices, News Production Processes and Journalistic Witnessing.” Journalism Studies 14 (4): 491–506.

- Watts, R., and J. Maddison. 2014. “Print News Uses More Source Diversity Than Does Broadcast.” Newspaper Research Journal 35 (3): 107–118.

- Weaver, David H. 1998. “Journalists Around the World: Commonalities and Differences.” In The Global Journalist: News People Around the World, edited by David H. Weaver, 455–80. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

- Weaver, D. H., and G. C. Wilhoit. 2020. The American Journalist in the 1990s: U.S. news People at the end of an era. New York: Routledge.

- Wilkins, L. 2016. “Affirmative Duties.” Journalism Studies 17 (2): 216–230.