ABSTRACT

Investigating experience is becoming a greater concern in Journalism Studies. However, while “experience” is often mentioned, it is either never fully discussed or it is approached in terms of mere sensory or emotional response. Experience, instead, involves additionally (and simultaneously) situatedness, embodiment, and continuous re-processing over time, most of which lies beyond consciousness and is not easily articulated by words. Drawing on Whitehead's processual philosophy and Gendlin's philosophy of the implicit, this article addresses the calls in the field for “taking experience seriously.” Theoretically, it tackles the ontological leap required to be able to conceive experience. Methodologically and empirically it demonstrates the potential for applying creative techniques to retrieve and express the knowledge beyond words that is not captured by established methods. It does so by sharing the author's reflection matured through long-term experimentation with creative practices in research and the creation of an embroidered collage inspired by the project “Being a foreigner at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of news consumption on the everyday life of migrants in Norway.” The article takes the form, in itself, of a collage and invites the reader to join into an experiential taster of its arguments.

Introduction: (Not) Putting the Finger on Experience

There is a growing interest in experience in Journalism Studies. However, so far, there have been only limited systematic efforts to engage with its theory and its empirical investigation. Even articles that explicitly refer to “experience” in their titles, in fact, often tend either not to discuss the concept at all or present it as self-explanatory (Costera Meijer Citation2007; Bethell Citation2010; Peters Citation2011; Livio and Cohen Citation2016; Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2019; Wagner and Boczkowski Citation2019; Link, Henke, and Möhring Citation2021 for some examples). Empirically, “experience” tends to be approached in terms of sensory or emotional response, especially when it comes to the study of immersive journalism and how audiences engage with news through interactive technology (see, for instance, de la Peña Citation2010; Shin and Biocca Citation2017).

There is a recognition that engaging with experience in journalism studies is important to better understand the way publics receive and consume news, as well as the working practice of journalists. Costera Meijer (Citation2020), for example, in reviewing a wide range of studies about the experience of news consumption by audiences, points out the limitations of current research and calls for “taking news experiences seriously” (Costera Meijer Citation2020, 393). In this respect, she advocates an approach that integrates insights from different fields, like “information studies, media studies, HCI [Human Computer Interaction] studies, entertainment studies, narrative studies, ethnography, cultural studies, and literary criticism” (Costera Meijer Citation2020, 399) in order to reach “beyond cognitive and pragmatic dimensions of news” to include “emotional, interactional, technological, haptic, practical, embodied, material, and sensory dimensions to the study of journalism” (Costera Meijer Citation2020, 399). This, as she explains, is not only important “for academic reasons” (theoretical and educational, presumably), but also “[b]ecause the business models of commercial and public service journalism increasingly depend on users' engagement with news, [so] doing justice to the situatedness of the news experience may encourage news organizations to rethink their assumptions regarding their users and audiences" (Costera Meijer Citation2020, 399).

When it comes to investigating the work of journalists, the “lived experience” of journalism is described as essential to understanding the changes we are witnessing in the media industry and in the journalistic profession. However, even analyses that underline the need to engage with such “lived experience,” come short of problematizing it and remain at an abstract level. Deuze and Witschge (Citation2016, 116), for instance, do mention the need for “new ways of conceptualizing and researching the lived experience of journalists,” yet the focus of their analysis is on conceptualizing the transformation of journalism. Wahl-Jorgensen (Citation2018) similarly argues for understanding the “lived experience” of journalists through their emotional life histories. Her analysis concentrates, though, on the emotional life history approach and on what this consists in: drawing on life histories interviews focusing on journalists’ emotional labor to better understand the interaction between the individual “experience,” which is said to be unique and embodied, and social context, particularly “institutional cultures and broader power relations” (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2018, 676).

In cases where experience in journalism is approached empirically, this tends to be engaged through the sensorial or emotional dimension. Hölsgens, de Wildt, and Witschge (Citation2020), in “Walking the Newsroom: Towards a Sensory Experience of Journalism,” for instance, explore “the spatial, socio-cultural, rhythmic, tonal, and somatic characteristics” of the newsroom of a Dutch regional newspaper by using video, sound, text, and drawing. Their aim is to allow the reader/consumer of the article to “experience” the newsroom by providing them with an “insight into the journalists’ lived experience of their profession as fundamentally interwoven with the idiosyncrasies of their workspace” (Hölsgens, de Wildt, and Witschge Citation2020, n.p.). Witschge, Deuze, and Willemsen (Citation2019) also experiment with creative empirical approaches that range from encouraging journalists to writing love letters (“an ode to journalism”) or “resignations letters to the profession,” to visualizing oneself “as an object in the public domain” (Witschge, Deuze, and Willemsen Citation2019, 977). As they write: “Creativity […] allows us to gain insight into experiences, motivations and emotions in journalism, allowing us to tell the diverse stories of journalism in a more inclusive way” (Witschge, Deuze, and Willemsen Citation2019, 974). Kotišová (Citation2019) further uses creative non-fiction to both examine and convey the emotional experience of crisis reporters. There are also cases where experience is de facto being investigated, and perhaps more holistically than in previous examples, yet it is not presented through the lens of this concept and, again, not explicitly discussed. Brouwers (Citationforthcoming), in this respect, uses autoethnography, among other methods, to share with the reader her experience of becoming—acting like, feeling like, and living the values and norms in her everyday life—of an entrepreneurial journalist.

To summarize this fragmented scholarly landscape and provide an anticipation of the content of my analysis I can say that experience, to put it metaphorically, is like an iceberg. At the moment most studies barely mention the iceberg. Others investigate the part that is visible above the water, especially its sensory component. Art-based methods, including multimedia installations and creative writing, in combination with more “traditional” methods are being fruitfully used to convey the sensate and affective part of experience. This article builds on this existing research, but advances it by engaging more deeply and holistically with experience—theoretically, methodologically and, through some “how to” practical tips, empirically—by diving below the water.

The argument I am going to develop, in a nutshell, is that to really capture experience we need, first, ontologically, to start understanding reality in relational and processual terms. Second, we need to acknowledge that lived experience—by journalists exercising their profession, audiences consuming journalistic products, but also by researchers studying journalism—is a source of knowledge. Knowledge, in fact, is not only produced by our brains but by our entire bodies continuously interacting with the environment—physically, informationally, imaginatively, sensorily—as a whole (Gendlin Citation1962; Gendlin [Citation1978] Citation2003; Haraway Citation1988; Barbour Citation2004; Spatz Citation2015; Johnson Citation2017). The knowledge that does not derive from rational thought processing, however, is often not regarded as knowledge at all, not least because it is not readily available for articulation. Creative practices are, in this respect, a useful tool to access, “translate” and make accessible such implicit knowledge that is lived, embodied—and, as such, “encoded” under our skin, in our subconscious, in our emotions, memories, movements. The questions I thus address are: How to conceptualize the knowledge (by audiences, journalists, and journalism researchers) contained in experience? And how to empirically access it and articulate it? I am particularly interested in how to access and, in fact, capitalize, on the part of experience that is hidden, pre-reflective, non-conscious. To do so I draw on Gendlin's philosophy of the implicit and my own creative application of two techniques he devised for accessing the pre-reflective domain of experience, “focusing” and “thinking at the edge” (TAE). In this piece, I specifically focus on demonstrating the benefits of accessing embodied knowledge for researchers, although the techniques presented can equally be applied to any participant, whether journalists or members of the public, within a journalism study—or, indeed, further afield.

The arguments, analysis and reflection presented here are the result of my long-term engagement in developing new theory and method. This has involved, over time, experimentation with creative writing and poetry, theater, voice, and film-making (Archetti Citation2015, Citation2018, Citation2019, Citationforthcoming). This article particularly draws on my theoretical and methodological investigation into silence, especially what I learned in dealing with the challenges of making sense of the silenced stories and knowledge that are “stored” in our bodies, how to empirically collect such data, and how to convey what cannot be satisfactorily captured by words, like experiences of grief or living life as a bearer of social stigma (Archetti Citation2020).

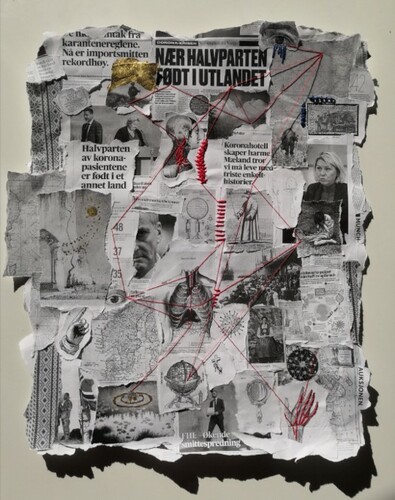

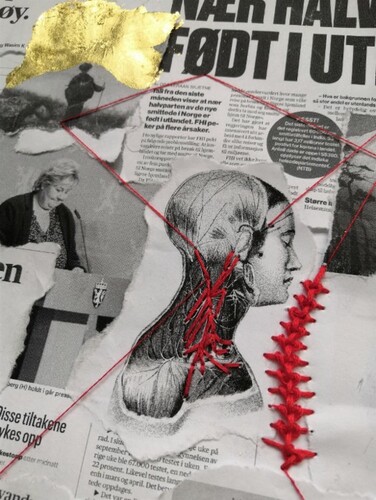

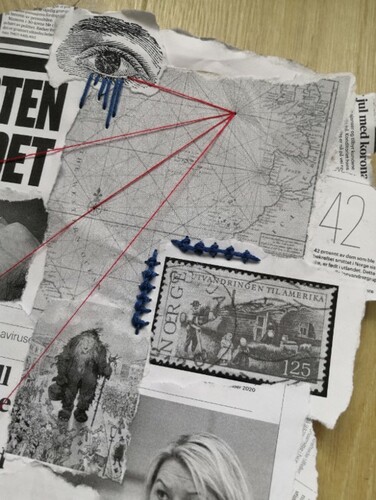

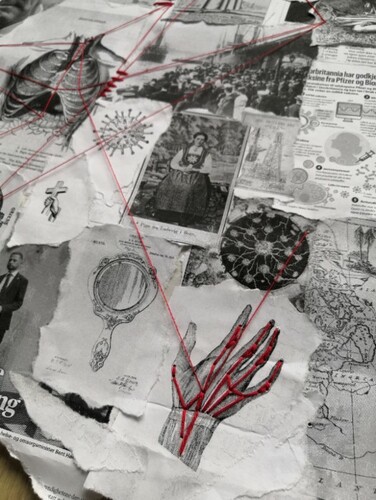

The very drafting of the text you are reading was stimulated and facilitated by the making of an embroidered collage, which I present here as an illustration of my arguments. It is part of the preliminary work on the project “Being a foreigner at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of news consumption on the everyday life of migrants in Norway,” a project in collaboration with Banafsheh Ranji (University of Oslo).Footnote1 This creative output enabled me to articulate both insights about the project and reflections on the function of creative approaches of which I was still unaware and for which I had not yet found words. The collage began as a spontaneous, unplanned activity. Yet, the handwork—particularly the selection of the excerpts of printed-out texts and images (including their shredding), their relational positioning in the final arrangement, the embroidery (with the choice of stitches, colors of thread), interaction with both the images and text, highlighting of details with golden leaf—helped me to synthesize literature I had been reading from a variety of fields, as well as to become aware of my own engagement with the project's materials, being myself a migrant consuming Norwegian media coverage during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The rest of the article takes the form, in itself, of a collage that includes analysis, excerpts of diary, photos, the text of an application, and an email exchange. They document the way a range of previous experiences coalesced into the outcome you are reading. Some pieces of information are arranged as loose threads—for the reader either to follow, to leave, or to trace new connections with. The piece also invites you to join into a practical activity: an experiential taster of its arguments.

The structure, register and tone are, at points, different from what you might expect from an “academic” article. It would indeed have been easier to follow the usual template—one I have been trained in since I was a student and feel safer applying. Evading some academic conventions is here a deliberate choice that reflects my effort to use the very dis/connections in the text not only as a medium for my analysis, but also as a device to literally materialize the theoretical arguments about the nature of reality and experience that I will outline. Bogost, in writing about techniques to reveal hidden—or “alien,” as he calls them—phenomenologies, calls the practice of “making things that explain how things make the world” “carpentry” (Bogost Citation2012, 93). The text that follows is part of the disruptions, interruptions, distractions, cinematic cuts-to-a-different-scene of a TV series, intrusions of our mediated life. It is part of the reader's very experience. As such, it is “mess” (Law Citation2004): orderly and disorderly, both cognitive and intuitive.

From: Banafsheh Ranji <[email] >

Sent: 23 April 2021 10:48

To: Cristina Archetti <[email protected]>

Subject: Migrants and Covid-19

Hi Cristina,

I hope you are well. I have talked with some people with different backgrounds and have noticed how frustrated they are about the representation of “migrants” [in Norway] during Covid-19. I was thinking whether we could write a piece together combining content analysis of media representations and interviews with migrants. It could be in a form of a research article, which could also have outreach in the Norwegian media, or it could be merely a piece for a media outlet.

I understand that writing for you is a personal task, and co-authoring may not be your preference. However, I think that would be great if we work together on this.

From: Cristina Archetti <[email protected]>

Sent: 23 April 2021 17:32

To: Banafsheh Ranji <[email]>

Subject: SV: Migrants and Covid-19

Hi Banafsheh,

Thanks for reaching out and for the suggestion! I think it is a great idea and would love to give it a try!

Content analysis and interviews for a peer-reviewed article sound good. In fact, I had applied to be able to access the Retriever database (to collect material for doing exactly content analysis of this issue!) and got a permission to retrieve up to 300 articles. So that can feed into the study.

I also can use 20,000NOK of departmental funding and was thinking that maybe we could hire one of the artists we have already collaborated with to help us develop the material further? Just an idea, mostly motivated by the fact that discrimination is an experience and there is so much more to potentially include that cannot be pinned down by text.

But maybe let's talk about this more?

Theory I: Obstacles to Grappling with Experience

The current challenges in conceiving experience, let alone making sense of it and investigating it empirically, stem from in-built limitations in the very way scientific thinking has developed since the Modern Age. They tend to affect Journalism Studies as much as the Humanities and Social Sciences at large. Four are most relevant here and I will very briefly outline them before moving on to discussing the nature of experience and a theoretical framework that can be helpful in conceptualizing it in its wholeness: processual philosophy.

The first limitation of scientific thinking, despite the heavy reliance on measurement and objectivity, is the dismissal of materiality. Latour, in this respect, points out that, albeit sociology has developed mostly after the Industrial Revolution, in an era of technological advances, the role of objects in our society is largely overlooked (Latour Citation2005, 73). Bennett (Citation2010), in Vibrant Matter, forcefully argues for the “vitality” of things: “the capacity of things—edibles, commodities, storms, metals—not only to impede or block the will and design of humans but also to act as quasi agents or forces with trajectories, propensities. Or tendencies of their own” (Bennett Citation2010, viii). Not realizing the agency of matter prevents us from seeing that we constantly engage in co-creation with objects—not least, as researchers, with our data. As Barad (Citation2007) points out, even in science we do not simply assemble data—as if this was “ready made” to be “harvested” (just like news is not simply “out there” for journalists)—and then “process it.” We create data through our methodological choices and then, together with this data, we co-create the world we live in. As Barad phrases it: “[m]aking knowledge is not simply about making facts but about making worlds” (Barad Citation2007, 91). Understanding that there is a connection between how we make knowledge (epistemology) and what exists (ontology) is essential for researchers to become aware of their responsibilities (ethics).

Recognizing the agency of things, however, also enables us to understand the added value—and knowledge—that is generated through the creative dances we engage in with the objects of our investigation. Eeg-Tverbakk (Citation2016)—drawing, among others, on Agamben (Citation1999), Benso (Citation2000), and Morton's (Citation2013) Object Oriented Ontology—writes, in this respect, about the importance of practicing, as researchers, an “ethics of the unknown” (Eeg-Tverbakk Citation2016, 23). This consists in deliberately using “pauses, silence, stillness, and patience” “to hear and sense the withdrawn aspects of things” (Eeg-Tverbakk Citation2016, 15): “to listen to what has not yet been formulated […] what can only be perceived as a notion, a murmur, or as a light touch of air” (Eeg-Tverbakk Citation2016, 24). In practice, if we were working with text material or interviews, this would consist in not wanting to explain all about their contents, imposing a coherent narrative on them, but letting what might be “in between the lines” remain suspended, perhaps unarticulated, ambivalent, undefined. When we do not “listen” to things/objects/data we also close our perception to the new and the unknown that is available and that can indeed be nurtured as a source of new knowledge (Archetti and Eeg-Tverbakk Citationforthcoming).

A second limitation of scientific thinking is the Cartesian separation between mind and body (Smartt Gullion Citation2018, 70). This has led to a privileging of the mind, and the cognitive dimension, with its presumed rationality, over the body, sensorial perceptions, and emotions (Johnson Citation2017, 2). This is reflected, methodologically, even in fields that call themselves “Humanities” and “Social Sciences,” by the neglect of bodies (Casper and Moore Citation2009), and the suspicion towards approaches that are not based on quantification or, like autoethnography, that might entail an emotional involvement by the researcher (Ronai Citation1995; Muncey Citation2010). Instead, not only are mind and body no longer conceptualized as separate (Damasio and Damasio Citation2006; Malafouris Citation2013), but the cognitive cannot be disentangled from the bodily dimension. As Spatz explains, “the mind is an emergent property of the body, just as body is the material basis for mind” (Spatz Citation2015, 11). Spatz is a pioneer in researching “embodiment,” which he broadly defines as: “[E]verything that bodies can do. In addition to the physical, this space of possibility includes much that we might categorize as mental, emotional, spiritual, vocal, somatic, interpersonal, expressive, and more” (Spatz Citation2015, 11, emphasis added).

A third limitation is the tendency to categorize, cut up and separate, isolate in other words, for the purpose of analysis, with the result that context is lost. As Law and Urry (Citation2004) point out, the Social Sciences suffer from the “methodological inheritance” (Law and Urry Citation2004, 403) of having been established in the nineteenth century largely to deal with the concerns of nation-states—“with fixing, with demarcating, with separating” (Law and Urry Citation2004). Drawing on broader calls for the “restructuring” of the Social Sciences (Wallerstein Citation1996), they advocate approaches that are less linear and “Euclidean”—less revolving around a set of “more or less spatial metaphors to do with height, depth, level, size and proximity” and better able to deal with societies and processes characterized by complexity, fluidity and connectedness (Law and Urry Citation2004, 398).

Fourth is the dismissal of imagination. Lachman (Citation2017) argues that since the beginning of the seventeenth century the rise of Scientism has meant the loss of the knowledge that derives from imagination. Scientism, in the words of historian Jacques Barzun is the “fallacy of believing that the method of science must be used on all forms of experience and, given time, will settle every issue” (Barzun in Lachman Citation2017, 15). While the scientific thinking the way we conceive it today tends to map onto what philosopher Blaise Pascal called “esprit geometrique” (mathematical mind), imagination reflects instead the “esprit de finesse” (intuition) (Lachman Citation2017, 17): “The spirit of geometry works sequentially, reasoning its way step-by-step, following its rules, whereas the intuitive mind sees everything […] at once” (Lachman Citation2017, 17). Drawing on Wilson, who explored the evolutionary potential of the imagination, Lachman defines imagination as “the ability to grasp realities that are not immediately present” (Wilson in Lachman Citation2017, 31). As he elaborates in his own words: “Not an escape from reality, or a substitute for it, but a deeper engagement with it” (Lachman Citation2017, 31).

Becoming aware of these biases helps us understand why it is so difficult to conceive experience as a whole and even come to term with the fact that it is, in itself, a source of knowledge. Further to this, experience, as a subject of investigation, can neither be put into a box or dismembered, even when we think we can draw boundaries around it in order to examine specific aspects of it—as in the case of investigating “immersion” within the experience of consuming immersive news in virtual reality (Shin and Biocca Citation2017), for example. John Dewey, philosopher and key theorist of experience, points out, in fact, that experience is, by nature, as broad as living life. Experience is not just about either the cognitive, or the sensorial—visual, haptic, sense of presence or prioception, among the rest—or the emotional. It is all of this together and, in addition to it, the imaginative, embodiment (in all of its manifestations, including movement), the learning and access to new knowledge that derives from the synthesis of all the mentioned aspects over time. Experience is thus an ongoing process and it is relational. As Dewey ([Citation1938] Citation1998, 41–42) writes:

that individuals live in a world means, in the concrete, that they live in a series of situations […] that interaction is going on between an individual and objects and other persons. The conceptions of the situation and of the interaction are inseparable from each other. An experience is always what it is because of a transaction taking place between an individual and what, at the time, constitutes his [or her] environment […] The environment, in other words, is whatever conditions interact with personal needs, desires, purposes, and capacities to create the experience which is had.

Dewey further points at three characteristics of experience: interaction, continuity, and growth. Interaction, in the words of Jinwoo Kim, a theorist of user experience who empirically applies Dewey's arguments, is a combination of “doing and undergoing” (Kim Citation2015, 17). Continuity is related to the fact that current experiences are connected to experiences of the past and those of the future: “the way of knowledge and skill in one situation becomes an instrument of understanding and dealing effectively with the situations that follow” (Dewey, 42). Growth, instead, refers to the fact that “[h]uman experience does not simply connect from past to present to future; during this process, experience is constantly reorganized and developed” (Kim Citation2015, 17).

Diary excerpt

Aberystwyth (UK), 27 April 2021

Discussed the project with Banafsheh. It is not just the news making me feel discriminated against. It is the combination with policies, the whole situation. All this “keeping the foreigners out.” The quarantine hotel. An official at the [Norwegian] border can decide, without knowing anything about my life, whether my reason for travelling was “necessary” or not. And I can't even appeal. It's totalitarian. It's humiliating. I feel unwelcome.

Theory II: A Conceptual and Practical Scaffolding to Approach Experience

We have so far seen the reasons why it is not possible, within mainstream scientific epistemologies, to fully make sense of the nature of experience. Experience in all of its dimensions would cover: human interactions with a material world that is not inert, rather constituted by “vibrant matter” (Bennett Citation2010); embodiment; an understanding—and matching research practice—that we live in an interconnected reality and that we do not “know” merely with our brains, but through all our senses and intuition. All of these aspects could be included in analyses of journalism. To do so, however, we need the right theoretical frameworks.

There are various approaches that can help do justice to the complexity and interconnection of the more-than-human world we live in. Among those developed by authors I have already mentioned are Latour's actor-network-theory (Citation2005) and Barad's agential realism (Citation2007). I will spend a few words, though, on the pioneer and founding father of processual philosophy, Alfred North Whitehead, who has influenced not only Latour and Barad, but also Gendlin, developer of a “philosophy of the implicit,” to which I will return shortly.

Whitehead's (Citation1929) provides an account of reality that does not envisage a rigid distinction between subject and object, “reality” and “perception,” or “material objects” and “thought.” Instead, he proposes a hyperconnected, non-anthropocentric reality, where the body, feeling, and intuition have an essential role and practically nothing would exist without experience.

To start with, the subject—this applies to any subject, not just humans—“emerges from the world” (Shaviro Citation2009, 21).Footnote2 As Shaviro clarifies Whitehead's position: “I am not an entity that projects toward the world, or that phenomenologically “intends” the world, but rather one that is only born in the very course of the encounter with the world” (Shaviro Citation2009, 21). In this world, which is in continuous becoming, “everything both perceives and is perceived” (Shaviro Citation2009, 27). The flow of interaction and co-creation is so fundamental that Whitehead phrases it as strongly as the following: “apart from the experiences of subjects there is nothing, nothing, nothing, bare nothingness” (Whitehead [Citation1929] Citation1978 in Shaviro Citation2009, 40).

Such interaction through which I (or a stone or a virus) come to appropriate the world is called by Whitehead “prehension.” This could be explained as the “way that what is there becomes something here” (Cobb Citation2008, 31) or, in other terms, the process through which the subject is constantly transformed. In the words of Cobb (Citation2008, 31): “the subject of the prehension becomes what it becomes through its prehensions.”

For Whitehead emotions, feelings, and the body have important roles in this process of relating to the world. In Shaviro's (Citation2009, 57) phrasing, “[w]e respond to things in the first place by feeling them; it is only afterward that we identify, and cognize, what it is that we are feeling.” “Feeling,” it must be said, has a specific meaning for Whitehead that differs from the way we use this term in everyday language. Feeling is part of prehension (Cobb Citation2008, 34) and, as such, it also involves inanimate objects: they also have “feelings” in the sense that they are relationally affected by other feeling agencies. As Shaviro (Citation2009, 59) further explains the role of feeling in being in the world: “phenomena are felt, and grasped as modes of feeling, before they can be cognized and categorized. In this way, Whitehead posits feeling as a basic condition of experience.” Indeed, we could say that “[e]verything that happens in the universe is thus in some sense an episode of feeling” (Shaviro Citation2009, 59).

In this world of experience, though, there is a lot we are not aware of. In Cobb's analysis of Whitehead's arguments: “Whitehead is sure that even when we are most acutely conscious a great deal is going on in our experience of which we are not conscious” (Cobb 21). Eugene Gendlin, both a philosopher and a psychotherapist, is precisely interested in the knowledge contained in this hidden dimension.

Gendlin (Citation1962, 1) starts from the consideration that “there is a powerful felt dimension of experience that is prelogical, and that functions importantly in what we think, what we perceive, and how we behave.” He calls “that partly unformed stream of feeling that we have at every moment” “experiencing” (Gendlin Citation1962, 3). Such experiencing, which he also refers to as “felt sense,” is not a bias in our thinking, but part of the very way we function as humans. As he writes,

[w]e cannot even know what a concept “means” or use it meaningfully without the “feel” of its meaning. No amount of symbols, definitions, and the like can be used in the place of the felt meaning. If we do not have the felt meaning of the concept, we haven't got the concept at all—only a verbal noise. Nor can we think without felt meaning (Gendlin Citation1962, 5–6 emphasis in the original text).

Two practical techniques he develops to tap into the implicit dimension of experience are “Focusing” and “Thinking at the Edge” (TAE). Focusing (Gendlin [Citation1978] Citation2003) consists in attending to the felt sense/experiencing where it manifests itself in the body. While getting into the details of this technique goes far beyond the scope of this discussion, some instructions to help engaging the felt sense and that are relevant here include: “get a sense of what all of the problem [whatever the issue we have chosen is, in the case of my collage the consumption of the portrayals of migrants in the Norwegian coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic] feels like. Let yourself feel the unclear sense of all of that”; “What is the quality of this unclear felt sense? Let a word, a phrase, or an image come up from the felt sense itself”; “Go back and forth between the felt sense and the word (phrase, or image). Check how they resonate with each other. See if there is a little bodily signal that lets you know there is a fit”; “Now ask: what is it, about this whole problem, that makes this quality (which you have just named or pictured)? ‘What makes the whole problem so ______?’” (International Focusing Institute Citation2020, emphasis in original; see also Gendlin [Citation1978] Citation2003, Chapter 4).

“Thinking at the Edge” (TAE) (Gendlin Citation2004; Krycka Citation2006), instead, is a process of using felt sense/experiencing to generate fresh words that exceed the limitations of existing language through tapping into our bodily knowledge. The underlying argument in Gendlin's thought is that, through our experience, we have developed new and unique knowledge:

Every living organism is a bodily interaction with an intricate situation and with the universe. When a human being who is experienced in some field senses something, there is always something. It could turn out to be quite different than it seemed at first, but it cannot be nothing (Gendlin Citation2004, n.p.).

Some of the steps within TAE are based on the already mentioned resonance and going back and forth between felt sense and words until they “feel” right and one is satisfied that the constellation of terms we have arrived at can truly express the felt sense. Some of the steps, in the words of Krycka (Citation2006, 5), who applies TAE to theory construction, are: “letting a felt sense form” around an issue we care about and would like to develop; “finding the more than logical in the felt sense” and writing “a paradoxical sentence” about our idea (Krycka Citation2006, 5); noticing that “conventional words” do not exactly say what we want them to mean (Krycka Citation2006, 6); writing our own definitions for the words we use (Krycka Citation2006, 6); then progressively finding new words and writing “fresh” phrases until we can express “the crux of our theory in public language” (Krycka Citation2006, 8).

Although when I started working on the embroidered collage I had not meant to apply either focusing or TAE, with hindsight I realized those techniques guided my creative process.Footnote3 Effectively I tapped into my bodily felt sensations—a felt sense that evoked unease, curiosity, rage, sadness, excitement, anxiety and which I could actually locate in my body—and this guided me, through the iterative process of selecting the texts and images for the collage, connecting the threads over the paper and carton, towards fresh insights that could not be contained by the existing, largely (neutrally worded) academic language related to the media framing of migrants (Pece Citation2018, for one example) or the coverage of the pandemic (Mellado, Hallin, and Cárcamo Citation2021, for instance). This creative practice allowed me not only to access my own—to that point unconscious and submerged—experience of consuming the Norwegian news of the pandemic, which I was then able to articulate, but importantly also to unlock my own long-term reflection on the nature of experience and what is needed to truly come to terms with it. In other words, I became aware of new knowledge I had in me, although initially I did not quite know what “it” was and how to express it.

Background to the Study

Excerpt from application for ethical approval (submitted to NSD [Norwegian Centre for Research Data] 4 May 2021).

“Being a foreigner at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of news consumption on the everyday life of migrants in Norway”

Plenty of research is currently being conducted on news consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. News consumption has, in fact, skyrocketed on an international scale, in parallel with the public's hunger for information about a threat—unprecedented in most people's lifetime—to one's own health, close family members’, and society's. One crucial aspect being investigated is the extent to which the publics trust the media and authorities as sources of information (for one example of this kind of studies in Norway see Ihlen Citation2019). Another important focus is how certain groups, particularly migrants and ethnic minorities, access information related to the pandemic (Nilsen Citation2021). COVID-19 infections, in fact, have not affected the population in a homogeneous way. There is evidence, for instance in the UK, that ethnic minorities are more affected by the virus (Kirby Citation2020). This happens for complex reasons that revolve around inequality and translate into worse housing conditions, difficulties in accessing healthcare, and employment in “essential” sectors of the economy that have to keep on functioning despite more generalized lockdowns (Morales and Ali Citation2021).

When it comes to Norway, the situation does not appear to be different. Reports by authorities and media have consistently suggested that non-Norwegian-born or foreign-born (ikke norskfødt, utenlandsfødt) individuals, have been affected by COVID-19 to a greater proportion than Norwegian-born (norskfødt) (see, for instance, Johansen Citation2021 or FHI Citation2021). Individuals not born in Norway and who have traveled into the country have also been associated, again by authorities and in media coverage, with the notion of “imported infection” (importsmitte) (see, for example, Strand Citation2021).

This study focuses precisely on how these and other media portrayals of non-Norwegian-born—whom we refer to as “migrants”—affect the migrants’ self-perceptions and everyday life—what the study will refer to, holistically, as “experience.” In this sense, the focus exceeds the cognitive dimension (receiving and understanding information) and extends to the emotional and affective domain (how one feels) and the behavioral one (what one does as a result of the combination of the information one receives and how one feels about it). In addition to this, the study is not only strictly interested in the extent to which migrants followed the regulations to prevent the spreading of the virus (smittevernetiltak), but also in how they went about their everyday life. This investigation thus deals, in practice, with the “experience of being a foreigner in Norway at the time of the pandemic.”

This study fits more broadly with the need to integrate, into the study of media effects, emotion, embodiment and situatedness—i.e., experience—beyond the cognitive dimension (Durham Citation2003; Goyanes and Demeter Citation2020).

Research Question

What effects has the media portrayal of migrants in COVID-19 coverage had on the migrants in Norway during the time of the pandemic?

Sub-questions: (a) What were the portrayals of migrants in COVID-19 coverage in Norway during the time of the pandemic? (b) Did these portrayals affect the migrants? If so, what impact did they have on the migrants’ thinking, emotions, and everyday life?

Diary excerpt

Aberystwyth (UK), undated, May 2021

How can foreigners be expected to integrate when they are constantly reminded of their ‘utenlandsfødt' (‘born-abroad') status? I feel alienated practically every single time I look at Aftenposten [Norwegian national broadsheet]. And I am not even part of the most discriminated ethnic and racial groups …

EXPERIENCEFootnote4

Take some old newspapers/magazines/junk mail leaflets from your postbox. Alternatively, open a tab for an image search on Google or another browser. For this activity, you might want to concentrate on a subject you are working on at the moment. Or you can connect to how you respond to the topics of the study presented in this article: either the portrayal of migrants in your country's media during the COVID 19 pandemic, or their/yours experience of that coverage (maybe you are also a migrant?). In either case, pay attention to how you feel about this topic: Can you locate that feeling in your body? Without trying to give it a name or categorizing it, focus on the physical sensation. Take your time. It might take 30 seconds to 1 minute to connect with it. You might not feel anything. That is fine, too. Keep on paying attention, with patience, noticing if anything changes.

Leafing through the printed materials or scrolling through the online images, pay attention to whether any of them resonates with you. Resonating means that that image catches your attention, it “moves,” “opens up,” “touches” something in you (Gendlin Citation2004, n.p.). If you are using an image browser you can use any keyword that pops up in your head while focusing on the physical sensation, even if it might seem completely unrelated, to retrieve the images.

Methods Within Methods Within Methods

There are multiple layers of method that need to be included here. As you would expect in a Whiteheadian reality, they are not entirely separable. There are the main methods of the study “Being a foreigner at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic”: content analysis and interviews. There is a second method I followed for creating the embroidered collage. However, the collage is materially made out of news stories that belonged to the sample of the content analysis. To be able to present and demonstrate an argument about a different way of investigating experience, as I did through the creative embroidery process, I further needed a different language than that of an “ordinary” academic article. There is thus also a third method I used for producing the “carpentry” (Bogost Citation2012, 93) that is the very text of this article.

Autoethnography (Jones, Adams, and Ellis Citation2013; Archetti Citation2020)—particularly the tapping into my own personal experience as a migrant and consumer of news in Norway to gain an insight into the experience of the broader group investigated in “Being a foreigner at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic”—is mostly visible in the embroidered collage and this article's text. Yet, it is a red thread (an appropriate metaphor, it turns out) that runs throughout, since it was my personal experience that led me to embark on the research project to start with.

(excerpt from the application for ethical approval—continued)

Content Analysis

This will focus on the media representations of migrants in the media coverage of COVID-19. It will be conducted on articles retrieved through the following keywords: norskfødt* [born in Norway] OR utenlandsfødt* [born abroad] OR importsmitte [imported infection] in Aftenposten, VG, Klassekampen within the timeframe 1 March 2020 to the present day [14 May 2021]. The keywords have been selected after a range of trials on the coverage. These are the terms that generate the richest representational frames. Aftenposten and VG are, respectively, the most read national broadsheet and tabloid in Norway and representative of mainstream media content in the country. Klassekampen has been selected for the potential, through its left-leaning political orientation, to provide a radically different framing.Footnote5 This is to get a sense of how consistent and widespread the frames about migrants are across the spectrum of public debate.

Interviews

They will be conducted on two samples of participants. The first, and most important, sample is constituted by migrants, both men and women (over 18), including both economic migrants and refugees who live in Norway, from as many countries- and ethnic backgrounds as our snowballing sampling will allow. While we expect the life stories and circumstances of every single interviewee to be unique, our aim is to reach a saturation point in our collection of reactions and experiences to the coverage where we can outline a set of impacts produced by consuming the news (if that is indeed the case) that can resonate, beyond the individual details, with other migrants. We would expect to conduct between 10 and 25 interviews. The two PIs are themselves non-Norwegian (one from a EU country, the other from outside the EU). We will thus start from our own network with the aim of reaching outside, as far as possible, from our circle of acquaintances, in order to include the maximum diversity of participants.

The second sample is made up of staff from selected embassies in Oslo. The routine work of foreign countries’ embassies includes monitoring the media of the hosting country. In this respect, embassies are particularly sensitive to the way both their own country and their citizens are represented in the media. The purpose of these interviews is thus to integrate the content analysis of media coverage, especially when it comes to aspects of the coverage that are not explicitly in the text, yet present and “written between the lines.” One example is offered by an official request for clarification issued by the Italian Embassy in Oslo in April 2021 in relation to the repeated mention, by Norwegian politicians and media, of “Italian flights” (“Italia-flyene”) in relation to importsmitte (Ambasciata d’Italia a Oslo Citation2021). While no explicit statement that Italian citizens were responsible for importsmitte was ever made, such statements contributed, in the view of the Embassy, to framing negatively the Italian citizens in Norway. We envisage about 5–10 interviews with embassy staff. We are going to contact the embassies directly, selecting the countries that are most mentioned in the content analysis of migrants and COVID-19 (on the basis of preliminary observations: Poland, Pakistan, Somalia, the UK, Italy, Sweden …).

* * *

The collage is made of paper, carton, glue, embroidery thread and golden leaf. The paper texts were selected among the front pages that most resonated with me after having read the first 300 pages (of about 700) of printouts from the content analysis sample (about 150 articles of a total of 309). This for the “material” part of the artifact. When it comes to the “implicit” work of resonance between mind and body that guided my arranging and sewing the different pieces of paper, I have covered this in discussing “focusing.” Among countless other experiences that fueled this creative output I was perhaps most directly inspired, apart from the literature discussed earlier, by reading about how to connect with embodied racial trauma (Menakem Citation2017); an informal “art therapy” workshop that revolved around making a collage using magazine images I took part in 2020 and led by pedagog Cristina Zappettini; “Homonexus,” a participatory textile installation led by artist Francesca Aldegani together with musicologist and musician Alejandro Villanueva, which embraced “an embodied and collective approach to cognition and motivation” in relation to the challenges posed by climate change and used “the traditional craft of embroidery as input for collective meditation and participatory change” (ClimaArtLab Citation2021); taking an online course on “Experimental embroidery techniques on paper” led by artist Gimena Romero.

As for the crafting of this article, I should mention the contribution of not-quite-standardized techniques in manipulating text which I have been practicing since taking a creative writing course in the UK a decade ago; what I learned through my reading on how to write novels, particularly the principle of “show do not tell”; the influence of a book by film director Paolo Sorrentino (Citation2016), Gli aspetti irrilevanti [The irrelevant aspects]. In this last respect, the mention of the interviews with embassy staff might not seem to serve any obvious purpose in this article, yet, like the background in a movie scene, it is essential to conveying (at a more intuitive level) a point that complements the story at hand: that a comprehensive investigation of the migrants’ experience of news during a global pandemic cannot be confined to news content analysis and interviews with migrants alone.

Embroidered Collage

EXPERIENCE

Select the images that resonate with you, even if do not feel you have any particular reason for choosing them. Do not think about it. Do not try to have selection criteria. Cut or rip off the images if you are using printed materials. Then position them onto a piece of paper or carton. You can fix them into position with glue, tape, needle and thread, pins … . If using digital images copy and paste them into a blank document (you can also change their size, duplicate them, or edit their color). Again try not to have any explicit criteria to do this. What position “feels” right for each image? Use your physical sensations as your guide.

Discussion: Lessons from the Other Side of Experience

By the time I started working on the collage I had read through about half of the coverage in the study's sample. That reading of the material was to be followed by iterative further “rounds” to build a codebook and identify patterns among the representations of migrants (frames)—a procedure of qualitative content analysis I am very familiar with. I could recognize, however, many articles I had already read before, at the time they were published. I could notice again the features that had moved me to start the study in the first place: the constant juxtaposition between infection rates among those “born in Norway” and those “born abroad”—a distinction institutionalized by the way statistical data are presented and even collected; the suggestion that the “pure,” “healthy” inside of the country, was being threatened and contaminated by an “infectious” outside. A headline in capital letters on VG on 11 December 2020 reads, alarmingly, “TEST ALLE! [Test all!],” paraphrasing a statement by Oslo's mayor Raymond Johansen in relation to 84 flights scheduled to arrive from Poland early in 2021. These aspects well fit into the intense “boundary setting” at the heart of Norwegian national identity discourse and practice, which often takes exclusive—including outright racist—turns (Gullestad Citation2002).

The collage, though, is not just a mirror reflection of these trends. The texts and images I ended up shredding and assembling create, relationally, a different picture. They reveal the resonance (interaction, to use Dewey's terminology) of the content of the coverage I consumed within the echo chamber of the combination of all my previous experiences (continuity): my having been a migrant for most of my life, my body and mind having navigated the spaces, practices, health-, security-, material- and emotional- landscapes of Italy, Norway, and the UK at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. This led me, beyond including glimpses of the coverage, to look for anatomical representations of body parts (I was particularly drawn to “hands” and “eyes”), images I would associate with Norway, including illustrations from folk tales (like “East of the Sun and West of the Moon”) and iconic paintings (like Nøkken [The Water Spirit] by Theodor Kittelsen), photos of Norwegian migrants, and nautical charts from the past. The collage visually maps where the representations of the migrants in the coverage fit within my experience. It reveals how the coverage affected me much more broadly (and it does so more accurately) than I could have ever done verbally (growth).

I am going to provide neither a description of what is glued onto the carton, nor attempt to explain why its components are positioned where they are (I actually still do not know), nor offer an interpretation of the meaning they might have. Partly because the collage is meant to be read as a whole, intuitively. Partly because, in the spirit of the “ethics of the unknown,” I want to leave some gaps for you to fill in with your own interpretation, which will be the result of reading this piece, looking at the photos (interaction) combined with everything you have experienced before (continuity). These unique combinations will also lead, in each reader, to new thoughts (growth).

I will focus, instead, on two major insights I gained from the making of the embroidered collage. The first is that experience has far more depth and breadth than I had initially realized. The experience of media consumption is nowhere near being exhausted by reading a piece of news and processing its information. It is more broadly about identity, belonging, feeling (or not) included, connecting with the world around and finding one's place in it. In my case, the stories of migrants in the coverage are inextricably interwoven with my own—through strong embodied emotions of grief, longing, but also hope and a sense of liberation from the constraints we have wanted to leave behind—with the narratives of those who came before, regardless of nationality, the stories of the host countries, and an uncertain future. I could further see how understanding of reality, whether we feel we are “at home,” how we decide to behave on that basis in our daily life, depends on a balancing act between objective circumstances (if they can ever be detached from perception) and imagined worlds. Media coverage is an essential part in the making of these (veritably so) existential coordinates—in my case they are unsettling and contradictory: Is Norway the fairy tale country it naively likes to portray itself as (and many like to see from abroad), or is it in fact a land of discrimination when you are not “one of them”? (see also Wiggen Citation2021).

Second, I was able to access a dimension of experience that I had been unaware of, let alone been able to articulate. The bottom line is that we can only speak of what we are aware of. Interviews cannot thus reach beyond the conscious dimension of experience. As a result, Ranji and I are planning to involve the migrant interviewees (those who will agree to it) in the additional making of a creative output.

EXPERIENCE

Observe the resulting collage. Could there be clues there to (maybe unusual) connections, associations, entanglements that are worth pursuing further? Could it contain one or more angles from which to observe/approach/understand your topic of investigation? Can you try and find words that feel “right” to express what is in this output? It might also be helpful to leave the collage in a place where you can look at it and see if, in a while, something from it resonates with you. Allow the object to “speak” to you rather than impose a meaning on it.

Conclusion: Embracing Experience

This article has addressed calls in the field for taking experience seriously, for approaches that can make sense of journalism and its practices in a broader context, through an engagement with processes of transformation over time, for more emotion, embodiment, and for qualitative, particularly non-representational methodologies (Vannini Citation2015).

More specifically, the analysis and reflection on theory, method and creative practices make four contributions to the field. First, the ontological and epistemological scaffoldings presented here enable to dig deeper, more deliberately and rigorously into experience than it has been the case so far. In this sense they can complement existing, mostly sensorial, approaches to the investigation of experience by extending their reach into new, and so far hidden, domains of investigation. When it comes to examining the experience of journalists in their everyday life, for example, I could not agree more on the need to draw on a “history from below” (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2018, 676). However, as suggested by the analysis, what can be accessed, even through in-depth personal interviews, is limited. One can only talk about what one is aware of. I argue for expanding and deepening the “history from below” project through a “history from within”: accessing the experience—i.e., the knowledge, the fresh insights that journalists (to continue with the same example) have acquired for their very having lived through the changes of the industry and in the practices of their profession—but which they are perhaps not yet able to vocalize. This approach does not apply only to journalists, of course, but also to how audiences experience journalistic outputs—in studies of news consumption, for instance—and, as in the case I have presented in this article, to the way researchers of journalism relate to their data. I will get back to this last point shortly.

Second, when it comes to cases where creative and art-based approaches are already applied to the study of journalism, the theoretical framework I have presented can help to ground them: clearly, art-based approaches do provide a different perspective and add value to our research, but the arguments I outlined here can explain why and what creative approaches can contribute exactly. Creativity is certainly a means to gain insight into- and tell different stories about journalism (Witschge, Deuze, and Willemsen Citation2019, 974), but it is also, importantly, a tool of investigation, analysis, reflexivity in its own right.Footnote6

Third, I have pointed out that experience can, and should, also be investigated from a researcher's perspective. We as researcher have more knowledge inside ourselves (literally) that we are aware of or dare to express. We need to nurture it to produce those innovative insights we so urgently need, as it is so often repeated, at a time of upheaval and change.

Fourth, the article has provided practical suggestions about techniques (or are they methods?), from “focusing” and “thinking at the edge” to embroidery, and to crafting written texts that, while taking liberties with the academic genre, are still scientific and even perform, through their own very features, theoretical work. These techniques can be applied, adapted, re-imagined for accessing implicit dimensions of experience among different audiences and participants in investigating mainstream topics in journalism studies, or used as a springboard for new trajectories of exploration. In fact, what new questions arise when we change our view of what can be investigated, as well as the tools/practices we use to engage it?

The analysis here is admittedly only scratching the surface of very broad issues and extremely diverse bodies of literature. My aim, as I said at the beginning, was to dive: to stir the water. Where the ripples and resonances of this article will lead me or others to is yet unknown. And that is a very productive place to be in.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Editor and the anonymous Reviewers for their open-mindedness in, first, considering, then publishing, a manuscript that deviates in style and format from the academic convention. The constructive comments by the anonymous Reviewers supported me in strengthening the consistency between the different components of the article, particularly the alignment between theory, methods and textual features. I also wish to thank Banafsheh Ranji, both for reading—and being so supportive of—an early version of this text, and for the honest conversations about our personal experience of consuming news during the Covid-19 pandemic, both as researchers and as migrants.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 The project began in summer 2021, without funding, as a personal response to the experience of consuming the news of the pandemic by the researchers. While this article was under review, the study received a grant by Medietilsynet (Norwegian Media Authority) under the new title “Samlende eller splittende? Betydningen av medieframstillinger av innvandrere for integrering [Unifying or divisive? The importance of media portrayals of migrants for integration].” In the rest of the text the Norwegian term “innvandrer” is rendered in English as “migrant”: “someone who changes his or her country of usual residence, irrespective of the reason for migration or legal status” (UN Citation2022).

2 I refer to Shaviro's and Cobb's work as this helps rephrase the dense and (often) obscure writing by Whitehead.

3 For the application of Gendlin's techniques to artistic processes see Banfield (Citation2016).

4 Through the following instructions I intend to provide an experiential taster of the potential insights that researchers can gain from accessing their own hidden dimension of experience and embodied knowledge. They are inspired by Gendlin's Focusing and TAE. They are, however, also an extreme simplification.

5 For more background information on these outlets in English see Life in Norway (Citation2020).

6 I expanded on this in Archetti (Citation2015).

References

- Agamben, G. 1999. Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. New York: Zone Books.

- Ambasciata d’Italia a Oslo. 2021. L’Ambasciata italiana su alcune dichiarazioni del leader laburista Jonas Gahr Støre. Ministero degli Esteri, 8 April. https://amboslo.esteri.it/ambasciata_oslo/it/ambasciata/news/dall_ambasciata/2021/04/l-ambasciata-italiana-su-alcune.html?fbclid=IwAR0F6H23mm6ESLqiegAOTVyyajvAVFfk0ueSow9pV_C8RLmdw7uRATKuAGQ.

- Archetti, C. 2015. “Journalism, Practice and … Poetry: The Unexpected Effects of Creative Writing on Journalism Research.” Journalism Studies 18 (9): 1106–1127. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2015.1111773

- Archetti, C. 2018. “Embodied.” Performance Lecture Delivered at “Fortellerfestivalen [Norwegian Storytelling Festival],” Sentralen, Oslo, 14–15 April. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XcAzx0jlhI [YouTube video].

- Archetti, C. 2019. “Journalism, Truth and Objectivity: An Exploration.” Performance Lecture with Erik Dæhlin, Tale Næss, and Njål Sparbø, Sentralen, Oslo, 26 November.

- Archetti, C. 2020. Childlessness in the Age of Communication: Deconstructing Silence. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Archetti, C. forthcoming. “Deviations: Poetic Reflections on Method” for Screenworks (link to video: https://bit.ly/3spzT7c).

- Archetti, C., and C. Eeg-Tverbakk. forthcoming. “Enabling Knowledge: The Art of Nurturing Unknown Spaces.” Nordic Journal of Art and Research.

- Banfield, J. 2016. Geography Meets Gendlin. An Exploration of Disciplinary Potential Through Artistic Practice. New York: Palgrave.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. London: Duke University Press.

- Barbour, K. 2004. “Embodied Ways of Knowing.” Waikato Journal of Education 10: 227–238.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books.

- Benso, S. 2000. The Face of Things: A Different Side of Ethics. Albany: State University of New York.

- Bethell, P. 2010. “Journalism Students’ Experience of Mobile Phone Technology: Implications for Journalism Education.” Asia Pacific Media Educator 20: 103–114.

- Bogost, I. 2012. Alien Phenomenology: Or What It’s Like to Be a Thing. London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Brouwers, A. forthcoming. “Failing Journalism, Saving Journalism: The Becoming of an Entrepreneur.” PhD thesis, Groningen: University of Groningen.

- Casper, M. J., and L. J. Moore. 2009. Missing Bodies: The Politics of Visibility. New York: New York University Press.

- ClimaArtLab. 2021. Evolving Futures: Owning Our Mess. Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research (KLI). https://www.kli.ac.at/content/en/arts_and_science/ClimArtLab.

- Cobb, J. B. 2008. A Glossary with Alphabetical Index to Technical Terms in Process and Reality. Claremont, CA: P&F Press.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2007. “The Paradox of Popularity: How Young People Experience the News.” Journalism Studies 8 (1): 96–116. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700601056874

- Costera Meijer, I. 2020. “Journalism, Audiences, and News Experiences.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen, and T. Hanitzsch, 389–405. New York: Routledge.

- Damasio, A., and H. Damasio. 2006. “Minding the Body.” Daedalus 135 (3): 15–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/daed.2006.135.3.15

- de la Peña, N., P. Weil, J. Llobera, B. Spanlang, D. Friedman, M. V. Sanchez-Vives, and M. Slater. 2010. “Immersive Journalism: Immersive Virtual Reality for the First-Person Experience of News.” Presence 19 (4): 291–301. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/PRES_a_00005

- Deuze, M., and T. Witschge. 2016. “What Journalism Becomes.” In Rethinking Journalism II: The Societal Role and Relevance of Journalism in a Digital age, edited by C. Peters, and M. Broersma, 115–130. London: Routledge.

- Dewey, J. (1938) 1998. Experience and Education: The 60th Anniversary Edition. West Lafayette, IN: Kappa Delta Pi.

- Durham, M. G. 2003. Toward a Phenomenology of Media Reading: Theorizing the Embodied Reader and the Text. Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. http://works.bepress.com/meenakshi_durham/36/.

- Eeg-Tverbakk, C. 2016. “Theatre-Ting: Towards a Materialist Practice of Staging Documents.” PhD thesis. London: University of Roehampton.

- FHI (Norwegian Institute of Public Health). 2021. COVID-19: Kartlegging av introduksjoner av engelsk og sørafrikansk SARS-CoV-2 virusvarianter på virusforekomst og betydningen for smittespredningen i Norge [COVID-19: Mapping of the Introduction of English and South African SARS-CoV-2 Virus Variants on Virus Prevalence and Significance for the Spread of Infection in Norway]. Oslo: FHI. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/526c6ea37ca541a2a26573d9d495f665/betydning-av-importsmitte-og-ny-introduksjoner-av-virus.pdf.

- Gendlin, E. 1962. Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning: A Philosophical and Psychological Approach to the Subjective. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe.

- Gendlin, E. (1978) 2003. Focusing: How to Gain Direct Access to Your Body’s Knowledge. London: Rider.

- Gendlin, E. 2004. “Introduction to Thinking At the Edge.” The Folio 19 (1). http://previous.focusing.org/tae-intro.html#b.

- Gendlin, E. 2018. A Process Model. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Goyanes, M., and M. Demeter. 2020. “Beyond Positive or Negative: Understanding the Phenomenology, Typologies and Impact of Incidental News Exposure on Citizens’ Daily Lives.” New Media & Society 4 (3): 760–777. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820967679

- Groot Kormelink, T., and I. Costera Meijer. 2019. “A User Perspective on Time Spent: Temporal Experiences of Everyday News Use.” Journalism Studies 21 (2): 271–286. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1639538

- Gullestad, M. 2002. “Invisible Fences: Egalitarianism, Nationalism and Racism.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 8 (1): 45–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.00098

- Haraway, D. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

- Hölsgens, S., S. de Wildt, and T. Witschge. 2020. “Walking the Newsroom: Towards a Sensory Experience of Journalism.” Journal of Artistic Research 21. https://www.jar-online.net/en/exposition/abstract/walking-newsroom-towards-sensory-experience-journalism.

- Ihlen, Ø. 2019. Retorikk om pandemi: Risikokommunikasjon i et endret medielandskap [Rhetoric about pandemics: Risk communication in a changing media landscape], project funded by SAMRISK, Norges Forskningsråd.

- International Focusing Institute. 2020. Learning Focusing: The Classical Six Steps. https://focusing.org/sixsteps.

- Johansen, P. A. 2021. “De ukjente supersmittekjedene bak tredje bølge: Én reisende fra utlandet førte til om lag 700 smittede [The unknown super-infection chains behind the third wave: One traveler from abroad led to about 700 infected].” Aftenposten, 3 May. https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/39GnXd/de-ukjente-supersmittekjedene-bak-tredje-boelge-en-reisende-fra-utland.

- Johnson, M. 2017. Embodied Mind, Meaning, and Reason: How our Bodies Give Rise to Understanding. London: University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, S. H., T. E. Adams, and C. Ellis, eds. 2013. Handbook of Autoethnography. London: Routledge.

- Kim, J. 2015. Design for Experience: Where Technology Meets Design and Strategy. London: Springer.

- Kirby, T. 2020. “Evidence Mounts on the Disproportionate Effect of COVID-19 on Ethnic Minorities.” The Lancet 8 (6): 547–548.

- Kotišová, J. 2019. Crisis Reporters, Emotions, and Technology: An Ethnography. London: Palgrave.

- Krycka, K. C. 2006. “Thinking at the Edge: Where Theory and Practice Meet to Create Fresh Understandings.” Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 6 (1): 1–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2006.11433935

- Lachman, G. 2017. Lost Knowledge of the Imagination. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Floris Book.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Law, J. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. London: Routledge.

- Law, J., and J. Urry. 2004. “Enacting the Social.” Economy and Society 33 (3): 390–410. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0308514042000225716

- Life in Norway. 2020. “Norwegian Newspapers: Where to Read News in Norway.” Life in Norway, 29 June. https://www.lifeinnorway.net/norwegian-newspapers/.

- Link, E., J. Henke, and W. Möhring. 2021. “Credibility and Enjoyment Through Data? Effects of Statistical Information and Data Visualizations on Message Credibility and Reading Experience.” Journalism Studies 22 (5): 575–594. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1889398

- Livio, O., and J. Cohen. 2016. “‘Fool Me Once, Shame on You’: Direct Personal Experience and Media Trust.” Journalism 19 (5): 684–698. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916671331

- Malafouris, L. 2013. How Things Shape the Mind: A Theory of Material Engagement. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Mellado, C., D. Hallin, L. Cárcamo, R. Alfaro, D. Jackson, M. L. Humanes, M. Márquez-Ramírez, et al. 2021. “Sourcing Pandemic News: A Cross-National Computational Analysis of Mainstream Media Coverage of COVID-19 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.” Digital Journalism 9 (9): 1261–1285. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1942114

- Menakem, R. 2017. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas, NV: CRP.

- Morales, D. R., and S. N. Ali. 2021. “COVID-19 and Disparities Affecting Ethnic Minorities.” The Lancet 397 (10286): 1684–1685. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00949-1

- Morton, T. 2013. Realist Magic: Objects, Ontology, Causality. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press.

- Muncey, T. 2010. Creating Autoethnographies. London: Sage.

- Nilsen, T. S., R. Johansen, L.E. Aarø, M.K.R. Kjøllesdal, and T. Indseth. 2021. COVID-19: Holdninger til vaksine, og etterlevelse av råd om sosial distansering og hygiene blant innvandrere i forbindelse med koronapandemien [Attitudes Towards Vaccines and Compliance with Advice on Social Distancing and Hygiene among Immigrants in Connection with the Coronavirus Pandemic]. Oslo: FHI. https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/2021/holdninger-til-vaksine-og-etterlevelse-av-rad-om-sosial-distansering-og-hygiene-blant-innvandrere-i-forbindelse-med-koronapandemien-rapport-2021.pdf.

- Pece, E. 2018. “The Representations of Migrants in the European Newspapers: A Comparison of Words and Media Frames.” In On Migrants Routes in the Mediterranean. Political and Juridical Strategies, edited by G. Truda, and J. Spurk, 163–177. Fisciano: ICSR Mediterranean Knowledge.

- Peters, C. 2011. “Emotion Aside or Emotional Side? Crafting an ‘Experience of Involvement’ in the News.” Journalism 12 (3): 297–316. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884910388224

- Ronai, C. Rambo. 1995. “Multiple Reflections of Child Sex Abuse: An Argument for a Layered Account.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 23 (4): 395–426. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/089124195023004001

- Shaviro, S. 2009. Without Criteria: Whitehead, Deleuze, and Aesthetics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Shin, D., and F. Biocca. 2017. “Exploring Immersive Experience in Journalism.” New Media & Society 20 (8): 2800–2823. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817733133

- Smartt Gullion, J. 2018. Diffractive Ethnography. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sorrentino, P. 2016. Gli aspetti irrilevanti [The Irrelevant Aspects]. Milano: Mondadori.

- Spatz, B. 2015. What a Body Can Do: Technique as Knowledge, Practice as Research. London: Routledge.

- Strand. 2021. “FHI: Mye importsmitte fra Afrika og Asia [FHI: A lot of imported infection from Africa and Asia].” NRK, 23 March. https://www.nrk.no/norge/fhi_-mye-importsmitte-fra-afrika-og-asia-1.15430368.

- United Nations (UN). 2022. “Definitions – Migrant.” https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/definitions.

- Vannini, P., ed. 2015. Non-Representational Methodologies: Re-Envisioning Research. New York: Routledge.

- Wagner, M. C., and P. Boczkowski. 2019. “Angry, Frustrated, and Overwhelmend: The Emotional Experience of Consuming News About President Trump.” Journalism 22 (7): 1577–1593. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919878545

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2018. “Challenging Presentism in Journalism Studies: An Emotional Life History Approach to Understanding the Lived Experience of Journalists.” Journalism 20 (5): 670–678. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918760670

- Wallerstein, I. 1996. Open the Social Sciences: Report of the Gulbenkian Commission on the Restructuring of the Social Sciences. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Whitehead, A. N. (1929) 1978. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Wiggen, M. 2021. “Norway, We Need to Talk About Racism.” openDemocracy, 17 June. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/countering-radical-right/norway-we-need-talk-about-racism/?fbclid=IwAR1P2lCDU29PRsYUiFl5Xg4NXLm3E8Tt0BNbj6Zgg67qDZvAzf6FZUirhis.

- Witschge, T., M. Deuze, and S. Willemsen. 2019. “Creativity in (Digital) Journalism Studies: Broadening our Perspective on Journalism Practice.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 972–979. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1609373