ABSTRACT

This article examines how investigative journalists, especially those working in newsroom contexts, deal with discrepancies between ideals and practice by actively negotiating their roles. Based on interviews with 28 Swiss journalists, it argues that despite having a strongly shared ideology revolving around the democratic roles of journalism, investigative reporters negotiate their investigative commitment on a daily basis. The study provides a conceptual model of this process based on a distinction between “liquid” and “solid” negotiation strategies, in the sense of Deuze. “Liquid” strategies involve reinterpreting, contesting and combining various journalistic roles, leading journalists to negotiate their investigative performance based on various individual organizational and institutional factors. Conversely, “solid” strategies tend to involve dogmatic attitudes toward investigative journalism. While this approach allows journalists to live by their ideals most of the time, it can also lead to simply dropping out. The study concludes with several important implications for research on journalistic identity and roles, as well as on media management, particularly regarding journalists’ agency in redefining journalism.

Introduction

Journalistic ideals are powerful driving forces of journalistic work, yet they are weakly translated into practice. Although a growing number of standardized studies have shown that the professional ideology shared by journalists is both evolving and seldom reflected in day-to-day work (Mellado et al. Citation2020; Mellado and van Dalen Citation2014; Pihl-Thingvad Citation2015; Tandoc, Hellmueller, and Vos Citation2013), recent research suggests that journalists cope with these issues by continually negotiating and reframing their ideals through role work (Raemy and Vos Citation2020). However, we still know very little about how exactly they experience and adapt to these gaps between ideals and practice (if indeed they do adapt) in a field tending increasingly toward “liquid” journalism (Deuze Citation2008; Kantola Citation2016), which is the current locus of complex negotiations regarding the “professional ethos” (Koljonen Citation2013, 150). Arguably, the degree to which journalists are able to align their practice with their values and identities is of major concern for media content, media organizations, and journalism in general (Alvesson Citation2004; Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014; Wiik Citation2009).

Investigative reporting is challenged by these normative shifts perhaps more than any other form of journalism, because it crystallizes certain key elements of the journalistic ideology. Indeed, the various practices and techniques used in investigative journalism (looking for hidden information with public interest, fact-checking, field work, data analysis, consulting a greater number of sources, etc.) are a means of performing core journalistic roles, particularly the watchdog function of democracy (Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2014; Matheson Citation2009). Additionally, because investigative journalism helps set standards of good journalism (Marchetti Citation2000), it is seen as a promising avenue for the renewal of the journalistic field as a whole, and therefore carries high value for both journalists and publishers (Carson Citation2019; Hamilton Citation2016; Neveu Citation2013, Citation2019).

This study aims to fill a gap in the literature by examining how small-scale investigative journalism is subjected to the discrepancy between ideals and practice. To do so, we conduct a qualitative analysis of journalists’ accounts of their investigative efforts in the newsroom context, which allows us to delve into the details of their processes. Previous studies have shown that beat reporter often fail to undertake investigative endeavours due to various obstacles, mainly relating to newsroom organization (Cancela Citation2021; Hamilton Citation2016). This study approaches that issue from a different angle, showing how investigative journalistsFootnote1 cope with these obstacles by continually negotiating between roles and practice. Additionally, it highlights how journalists’ discourses on investigative commitment (Cancela, Gerber, and Dubied Citation2021) become a means of processing and reframing their role performance.

The study draws on in-depth interviews with 28 Swiss journalists from different media outlets in French-speaking Switzerland; these interviews were conducted in connection with prior field observations, which are not discussed here (Cancela Citation2021). We first outline major topics in contemporary investigative journalism, including its definition, and explain the importance of journalistic roles and ideals in that field. We then discuss the broader ideals–practice gap and its connections with investigative journalism and journalistic commitment. Next, we present our method, an iterative movement between empirical data and theory. We present our findings in three steps: first, we discuss the interviewed journalists’ explicitly narrated ideals and examine the normative assumptions underpinning their commitment to investigative journalism. Second, we look at the narrated discrepancies between roles and practice, mainly concerning the journalists’ perceived ability to undertake investigative endeavours in the newsroom, and the workplace negotiations entered into (for time, resources, etc.). Third, we present the three main coping strategies emerging from journalists’ narratives in the face of these discrepancies (stay strong, give up or get perspective), and propose a model of how investigative commitment is negotiated.

We then reflect on our findings from the perspective of both roles and practice. With regard to roles, the journalists’ narratives show a strong (but not exclusive) orientation toward the watchdog role. However, a novel and interesting attitude we call the vigilante role also emerged from the data; this role is based on a (seemingly paradoxical) desire to balance the monitorial and adversarial roles. With regard to practice, results show that the journalists appear to struggle to realize their ideals solely through investigative practices, which leads them to negotiate on a daily basis. Two categories of journalists can be roughly distinguished: those who stick to “solid” ideals (Deuze Citation2008; Kantola Citation2013, Citation2016; Koljonen Citation2013)Footnote2 and those whose ideals are more flexible, or “liquid”; the latter use more nuanced strategies and rely on various practices to perform their roles, even proposing new ways to live out investigative ideals in the newsroom. We conclude the study with a discussion of the practical and theoretical implications of these findings.

Investigative Journalism as Role Performance

Within journalism, investigative reporting remains a much-discussed but understudied and ill-defined activity (Cancela Citation2021; Cancela, Gerber, and Dubied Citation2021). Since the Watergate scandal and the meta-journalistic discourses that followed, investigative journalism has become the public's almost mythical ideal of journalism (Marchetti Citation2000; Schudson Citation1996; Zelizer Citation1993), despite significant deviations from investigative techniques in actual practice (see Berkowitz Citation2007; Mellado et al. Citation2020; Nord Citation2007).

Thus, in spite of its centrality for journalism, investigative journalism remains caught in a definitional uncertainty, as Stetka and Örnebring recall (Citation2013, 3): «Defining investigative journalism is like defining good art or good literature: It is easier to point to examples of its practice rather than to set down a definition». As an ideal, it elevates to the rank of professional gold standard various forms of journalistic practices which involve revealing the dysfunctions of society (Carson Citation2019; Hunter Citation1997). In addition, scholars agree that investigative reporting is the highest form of journalism (Hunter Citation1997; Kaplan Citation2008; MacFayden Citation2008) and requires a higher commitment from journalists on several levels (Lemieux Citation2001; Mcquail Citation2013). For the purposes of this study, we use the following minimalist definition: “Investigative journalism is sustained news coverage of moral and legal transgressions of persons in positions of power and that requires more time and resources than regular news reporting” (Stetka and Örnebring Citation2013, 3).

McQuail (Citation2013) suggests that the main components of journalistic practice can be understood in terms of the degree of initiative and action taken by the journalist—i.e., the degree to which the journalist performs the media's surveillance/information role. McQuail also emphasizes that the boundaries of that role are “flexible.” Following this view, “critical or investigative reporting” (Citation2013, 105) is located at the far end of a similar passive/active continuum for the general role of the press, representing its most “active stance of watchdog”. This implies that investigative reporting and its methods, techniques and practices may be seen as the best way to perform certain important journalistic roles. The intermediate modes of role performing are certainly identifiable, says McQuail, but their boundaries remain unclear. Any attempt at clarification seems to run up against the blurriness of journalistic form and practice here (Deuze and Witschge Citation2020; Ruellan Citation2007). That is why this his study rather advocates for a discursive perspective on investigative journalism. In this perspective investigative journalism is seen as a set of practices and representations shared by a group of journalists with blurred professional boundaries, some of whom might be specialists and others generalists, caught in a complex articulation between professional norms, structural constraints, personal ideals, and concrete practices.

Journalistic Roles as Discursive Constructs

According to Alvesson (Citation2004), professional norms and personal ideals provide knowledge workers with both motivation and meaning in their daily work. This is certainly the case for journalists (Pihl-Thingvad Citation2015): “By referring to their ideals and values, journalists legitimize their work and distinguish themselves from non-professionals”, write Mellado and van Dalen (Citation2014, 863). Journalistic ideals commonly centre on around the democratic role of journalism in society and form a strong and shared occupational ideology (Deuze Citation2005), which researchers also refer to as “journalism culture” (Hanitzsch Citation2007) or “professional ethos” (Koljonen Citation2013). The nature and components of this shared ideology have been the subject of a huge body of research over the past decades from many perspectives (roles, values, ideology, identity, boundary work, professionalism, professional culture, etc.), which this empirical article will not detail here.

Recent research on roles has been important in conceptualizing the various aspects of journalistic ideology, resulting in a rich and comprehensive (if sometimes chaotic) catalogue of roles and conceptual framings that allows for systematic and comparative studies (e.g., Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018; Mellado Citation2015; Standaert, Hanitzsch, and Dedonder Citation2019; Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit Citation2019). The role-based approach to journalistic culture helps explain both its heterogeneous and evolving nature and the diffusion of collective journalistic norms, as noted by Le Cam, Pereira, and Ruellan (Citation2019). Broadly speaking, journalistic roles are often situated on dichotomic axes regarding various dimensions of journalism: adversarial/loyal, disseminator/interventionist, gatekeeper/advocate, consumer/civic orientation, and so on. Role research has argued that journalists working in similar contexts subscribe to a coherent set of journalistic ideals, and it has also demonstrated that the core features of this common ideology has evolved from “solid” to “liquid” (Koljonen Citation2013). Roles evolve over time and by region, and are subject to “continual discursive (re)creation, (re)interpretation, appropriation, and contestation”, according to Hanitzsch and Vos (Citation2018, 151). In this way, new understandings of traditional roles, as well as new roles, emerge, even as digital journalism is deeply impacting and reshaping journalistic practices (Witschge and Harbers Citation2018).

Although role literature is abundant within journalism studies, this paper mostly builds on two frameworks proposed by Hanitzsch and Vos (Citation2017, Citation2018), which allow us to connect our micro-level analysis (e.g., of individual journalists’ views and self-reports) with a macro-level analysis of journalism as a discursive institution, as well as a site of constant struggle over legitimate practices, norms, and values. The first is a comprehensive framework of 18 journalistic roles for the area of politics, based on six core functions of journalism: informational-instructive, analytical-deliberative, critical-monitorial (Fourth Estate), advocative-radical (power distance), developmental-educative and collaborative-facilitative (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018, 152–156). Taking a discursive institutionalist approach, Hanitzsch and Vos conceptualize roles as discursively constructed and as elements of the complex journalistic identity. For them, these roles are at the centre of an ongoing struggle around the legitimacy and practices of journalism and “perform a double duty—they act as a source of institutional legitimacy relative to a broader society and, through a process of socialization, they inform the cognitive toolkit that journalists use to think about their work” (Citation2018, 151).

The second is a more general role framework that moves beyond the level of description (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017, 129–129). They suggest a process model that distinguishes between four conceptual dimensions of journalistic roles: normative, cognitive, narrated, and practiced. Normative roles are abstract norms based on society's expectations regarding journalism, while cognitive roles are the individual beliefs, ideals, and values that journalists have inherited through professional socialization. Practiced and narrated roles, on the other hand, refer to concrete behaviours (i.e., journalists’ performance of roles): practiced roles are a kind of “role enactment” (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017, 126), i.e., the roles journalists actually undertake in practice, while narrated roles relate to journalists’ subjective perceptions of and reflections on their practiced roles. In sum,

the four analytical categories of institutional roles of journalists—normative, cognitive, practiced, and narrated roles—correspond to conceptually distinct features: what journalists ought to do, what they want to do, what journalists do in practice, and what they say they do. (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017, 124)

Ideal–Practice Gaps and Investigative Commitment

Scholarly interest on role performance has increased in recent years, with a focus on providing empirical clarity on how roles are implemented in media content and journalistic practices. This has mostly been done by examining the roles observable in published content (e.g., Mellado et al. Citation2020; Raemy, Beck, and Hellmueller Citation2018; Skovsgaard et al. Citation2013). This research has highlighted discrepancies between roles and practice, in particular with regard to civic and watchdog roles (Mellado et al. Citation2020).

Other scholars have explored these discrepancies from different perspectives, including through the lens of social psychology and knowledge-work theory. Pihl-Thingvad's work (Citation2015) on Danish journalists is another starting point for our study. That survey found that journalistic ideals were key drivers of journalists’ commitment in their day-to-day work, and claimed that discrepancies between ideals and practice became problematic when they negatively affected journalists’ professional commitment, which was the case for discrepancies related to the democratic functions of journalism (adversarial, disseminator, watchdog, etc). Pihl-Thingvad argues that such discrepancies are “very important” predictors for commitment, to such an extent that they neutralize the positive correlation between adversarial roles and commitment (Pihl-Thingvad Citation2015, 404). The author also builds on organizational literature to warn about the undesirable strategies that journalists develop to cope with such discrepancies, such as resigning and dis-identification (distancing from ideals), which, in turn, make it even more difficult for journalists to maintain high-quality reporting and keep on with their professional commitment.

Since journalistic commitment can be seen as the cornerstone of investigative journalism (Cancela Citation2021; Cancela, Gerber, and Dubied Citation2021), a parallel can be drawn for that field. Professional commitment reflects the “intrinsic desire” to work in an organization or profession, “typically related to values and ideals in the […] profession” (Pihl-Thingvad Citation2015, 397); investigative commitment, then, refers to journalists’ commitment to perform the ideals of investigative reporting within their organization.

Yet although research has found that gaps between ideals and practice put journalists’ commitment at risk, we still know very little about how this is concretely reflected in journalists’ experiences. Investigative journalism is a promising area of study in this regard, since it is resource-intensive (Konow-Lund Citation2020), ideals-concentrated, and seen as a way of performing the most important journalistic roles, an issue that no study has addressed directly to date.

Moreover, the growing body of investigative journalism scholarship, which suggests an increased interest in cutting-edge transnational and collaborative watchdog journalism, has also stressed the need for a closer look at the local and regional scene in traditional media (see Hamilton Citation2016) where investigative reporting faces particularly challenging conditions. Despite this, only a few studies to date have focused on small-scale investigative journalism.

Swiss journalism has recently become the focus of various studies on roles and journalistic identity (e.g., Bonfadelli et al. Citation2011; Bonin et al. Citation2017; Grubenmann and Meckel Citation2017; Raemy, Beck, and Hellmueller Citation2018; Raemy, Hellmueller, and Beck Citation2018; Raemy and Vos Citation2020). In addition to being rich and diverse (Dingerkus et al. Citation2018), the Swiss media system is undergoing significant change regarding investigative reporting, with a renewal of structures and practices (Cancela Citation2021; Labarthe Citation2020). Although the circumstances in Switzerland cannot be generalized to wider contexts, previous research has shown that the situation there is similar to that of other countries in Northern Europe, both in terms of the media system (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004) and of journalists’ working conditions and roles (Bonfadelli et al. Citation2011; Bonin et al. Citation2017; Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019).

In their recent study of Swiss journalists, Raemy and Vos (Citation2020, 108) stated that “journalists also have a hand in formulating and reformulating what their social obligations are; that is they have a hand in writing and rewriting institutional scripts”. On this basis, we chose to study journalists’ narrated role performance to examine what these authors broadly call the process of “role work”.

A Qualitative Study of Journalists’ Narrated Role Performance

This study builds on in-depth interviews with 28 Swiss journalists conducted within a broader research project on Swiss journalism. Comprehensive interviews such as these give journalists the opportunity to put their practices “into narrative forms” (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017, 127); they capture complex information, internal motivations, and allow researchers to move beyond common-sense understandings (Brennen Citation2017, 29), since they provide access to the actors’ knowledge and imagined solutions, as we will see below.

Internal negotiations of meaning around identity, roles and professionalism emerged as a key theme as the research progressed and memos were written, in a continuous dialogue between data and analysis in an “iterative process” inspired by grounded theory (Bryant and Charmaz Citation2010, 25). We then conducted a semi-inductive content analysis on this specific issue, looking for meaningful segments concerning investigative commitment, narrated roles, and expressed discomforts and/or practical negotiations relating to these themes. Segments were coded with the software Atlas.ti and subsequently organized into three main categories: narrated roles, expressed discrepancies, and practiced roles. Following Hanitzsch and Vos’ (Citation2017) distinction between role normalization and role negotiation, we then applied transversal categories of codes in the segments that showed some sort of negotiation around roles: “stay-strong”, “drop out” and “get perspective”.

Data

The interviews were conducted between November 2017 and August 2020. Journalists were questioned in open-ended conversation about their day-to-day professional activities, working routines and techniques, general thoughts about investigative journalism, and professional and educational paths. Journalists (see ) were selected using a combination of snowball sampling and careful identification of reporters who write investigative stories and/or claim to be investigative reporters, whether or not they are primarily assigned to investigative work (specialist vs. generalist). This sampling process continued until we achieved a qualitatively diverse pool of journalists (in terms of gender, age, type of media, editorial line, function, etc.) and investigative practices (investigative units, investigation specialists, generalists practicing on an ad hoc basis, etc.), as well as a saturation in the discourses.

Table 1. Summary table of journalists’ profiles.

All journalists were guaranteed anonymity and are therefore referred to as “he” regardless of gender. All quotations were translated from French into English as precisely as possible.

Findings

Investigative Journalists’ Narrated Ideals and the “Vigilante” Role

Journalists articulated various professional ideals when discussing their role performance, which can also be understood as the process of role reflection (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017). As expected, explicitly discussed ideals related to the democratic function of journalism in society, i.e., at least to provide citizens with the basic information necessary for political judgment (detached observers), and at most to act as the Fourth Estate. This relates to the informational-instructive and critical-monitorial functions of journalism, which are the foundation of journalistic identity (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018).

Interviewed journalists primarily reflected on the watchdog functions of journalism when giving rational, abstract accounts of their investigative efforts. Some made this quite clear and used canonical expressions such as “being the Fourth Estate”. This is no surprise, as this function “sits at the heart of the normative core of journalists’ professional imagination in most Western countries” (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018, 9). Some of the journalists were quite strong about this (e.g., “It seems to me that [investigation] is the essence of journalism. Anything else is PR!”)Footnote3, while others were more flexible in describing the same roles and partly contested them. However, they all demonstrated a proactive, continuous critical-monitorial posture grounded in a “natural” adversarial attitude towards authorities and elites (see Standaert, Hanitzsch, and Dedonder Citation2019, 12), where those in authority are perceived—in the journalists’ words—as hiding things with “high democratic value” virtually by definition.

The Vigilante Role

A new role emerged from our coding which has not yet been identified or described in the literature; we have called it the vigilante role. It sits at the crossroads of the critical-monitorial and the advocative-radical functions of journalism, which Hanitzsch and Vos (Citation2017, 7) depict as being similar in their circular framework. The vigilante role differs from the critical journalistic roles in that it involves moral evaluation; paradoxically, however, it is also actively grounded in the need for journalistic balance. Many of the interviewed journalists adopted the vigilante stance and felt committed not only to denounce problems, but also to provide a moral assessment, to distinguish right from wrong—“identifying the guilty”, as one journalist put it. Most were this way, but a small portion of these journalists were reluctant to describe themselves as taking what they would call a “posture militante” (“activist stance”), although they seemed highly motivated by potential legal repercussions of their investigations. This ambivalent positioning is illustrated by the following extract:

I don't want to change the system, I want to expose the problem. And then, the people in charge, the people who are RESPONSIBLE for it, the ones I try to point out every time—because some people are responsible for these situations … (…) So my job is to explain to these people, to show them what's going on—political leaders, economic leaders, the people who decide from day to day—and then it's up to them to decide if it should change. And if things don't change, then we’ll be there to uncover another story. But it's not up to me to decide if things have to change, I don't know. (…)

But you do have a desire behind an investigative piece to disrupt the system or to bring about change?

Well, yes! As journalists, if we denounce the system, we want it to change, of course, so that things will get better.Footnote4

Nevertheless, journalists’ narratives also referred to ideals relating to other functions of journalism, including educational and interventionist roles, as well as (to a lesser degree) the consumer-oriented role. For instance, some journalists suggested that the need for good storytelling to target audiences may occasionally allow for a more interventionist approach or “journalistic voice” (see Mellado Citation2015) than the traditional neutral stance.

Narrated Discrepancies Between Investigative Journalists’ Ideals and Practice

Despite holding strong ideals related to the critical-monitorial function—although sometimes in combination with other functions of journalism—the journalists described numerous discrepancies between their roles and practice, particularly regarding their ability to do investigative work on a daily basis. Journalists saw investigative reporting as a way to perform the above-mentioned core journalistic roles, such as being the watchdog of democracy or holding power accountable. They referred to various related investigative practices—such as field work, managing confidentiality, multisourcing, verification, data analysis, covering economic and political affairs, etc—which this study will not explore (for an overview of the set of methods and practices associated with investigative ideals, see Cancela, Gerber, and Dubied Citation2021).

It quickly became clear that journalists could not undertake investigative practices every day, and when they did, they could not always do so in the desired or “noble” way. The main reasons cited were a lack of time due to their job responsibilities, and/or editorial policies in their newsrooms that often required them to deal with daily news coverage even if it was not part of their job description. The complex and time-consuming nature of investigative work and its intrusion on the journalists’ private lives also emerged as an important theme. The pace proved to be exhausting: “You have to keep up, because you get tired of covering three or four stories a week and trying to investigate at the same time. It's not that easy.”Footnote6 Except for a few privileged members of special investigative units, the narratives portrayed investigative reporters in the newsroom as constantly struggling to cope with the daily news pace and their managers’ (sometimes contradictory) expectations.

There is what I want to do, and then what is imposed on me. From time to time, my phone rings, it's my boss with some local news story, I don't know … landslides, bad weather, whatever. And I end up covering a story on bad weather … […] and sometimes I don't come up with any outstanding news, but I still try to make it work because my managers would be very unhappy if I didn't manage to write a story after spending several days on it.Footnote7

Thus, the narratives suggested that investigative commitment is difficult to sustain largely because of the complex and demanding nature of investigative reporting in the newsroom context, which is made even more difficult by insufficient time and resources due to budget cuts. The following section explores how these journalists adapted to this challenging professional context.

Journalists’ Negotiations

We have shown that most of the investigative journalists in the newsroom aspired to strong adversarial and critical-monitorial roles, which they tried to enact through their investigative efforts. At the same time, the narratives indicated that only a few journalists actually benefited from the working conditions necessary to fully deploy these efforts. Despite this, several reporters managed to be quite prolific because they actively negotiated for the time or resources needed to investigate.

Naturally, these journalists offered their interlocutors something in return for additional resources (time, help, travel, etc.). For example, they might offer to cover a few additional “basic” or “easy” stories to compensate for the time spent on their investigative work and allow their newsroom to continue functioning; commit to giving a detailed story pitch or synopsis halfway through, which could reassure managers; or cover investigative stories that were either in line with their colleagues’ or managers’ expectations (i.e., related to current news, embodied, trendy) or that were “impactful” (i.e., they “made a mark”, offered “added value”, or even generated a lot of media noise in the public space—e.g., leaks).

In undertaking workplace negotiations, most journalists were aware that they were asking for a “privilege” they would have to justify in some way to their colleagues, regardless of the structure and size of their newsrooms or investigative units. A small number of journalists did not have to negotiate as frequently for investigative resources, because investigation formed a part of their job specifications (e.g., they were members of a dedicated team). But even these journalists reported negotiating within their team—to get their stories through or to “skip their turn” in the production chain, for example—by relying on the same kind of practical strategies as above.

When additional resources were granted as a result of these negotiations, the journalists often had to deal with accompanying constraints: limited time; getting interrupted by more urgent work; being assigned to work with colleagues or being required to organize their work in a way they had not necessarily imagined; restrictive proofreading by legal services, etc. In some cases, stories were published too early and against the journalists’ will. But even more frequently, journalists said much of their work just went “in the rubbish”: many stories were not being published in the end, either because they could not be completed, or because the editors did not want them.

When the journalists failed to obtain the necessary resources through practical negotiations, some reported deliberately moving up in the newsroom hierarchy to create more space for investigation. Others said they chose to change newsrooms, go freelance, or create their own media when they felt they were not getting enough opportunities—which we describe in the section on coping strategies as “giving up”. To explain these strategic changes in status, journalists sometimes cite the lack of “investigative culture” in their old newsroom or a lack of support from managers when faced with harsh legal consequences (e.g., “we’ll do everything to limit the legal fees, even if it means completely grovelling)”.

The above suggests that most journalists are required to work hard if they want to continue with their investigative projects, regardless of the constraints they face (lack of time, support, etc.). Indeed, the heavy workload emerged as a major theme in the narratives about investigative commitment. Most journalists reported having an exceptional work capacity that goes beyond contractual obligations, and seemed to extend their work hours endlessly to pursue investigative stories in the margins. Consider these comments:

I don't have lunch systematically with my colleagues; you have to schedule work appointments on your lunch breaks! You have to be productive, efficient! And no coffee breaks … Footnote9

So finally the way I found [to investigate]—like several other journalists I think, the really motivated ones—is to do this outside of work hours. A lot of overtime and … if you consider the job seriously, it's necessarily time consuming because it implies going to lunch with sources, having drinks with sources […] so people [who want to do investigative reporting] face a choice: do they want to do it or not? In any case, I wanted to do it and I tried to do it as much as I could.Footnote10

Stay Strong … or Give Up

A few of the journalists expressed a strong reluctance to compromise on their ideals. They usually considered investigative journalism to be the essence of their profession and any other form of journalism to be irrelevant. At the risk of oversimplification, these journalists “stayed strong” on their investigative commitment and rarely negotiated heir professional ideals.

Apart from a rigid conception of investigative journalism, other elements are involved here. These narratives emphasized the importance of personal characteristics: investigative journalists were described as being particularly tenacious and curious, or free of ties, which would lead them to (and allow) such heavy workloads. Being “passionate” was also a criterion that emerged in most accounts. This shows the persistence of shared professional beliefs, in particular the belief that journalism is a “métier-passion” (“profession of passion”) (Ruellan Citation2001, 147).

In addition, the narratives revealed several practical and/or strategic reasons to stay strong on their investigative commitment, for instance the need to maintain an efficient network of sources. As one reporter put it: “If you’re out of the loop for even two weeks, well … you’re out. And it's hard to get back in the game then.”Footnote11 Nonetheless, such a strong commitment combined with a heavy workload becomes problematic in the long run, as another well-known investigative reporter suggested:

Honestly, I work minimum ten hours a day, fifty hours a week. But since I work weekends too, I would say minimum, minimum (laughs) I think minimum fifty-five (hours), yes. But I know that I am regularly on the verge of burn-out.Footnote12

Giving up can mean a plain and simple exit (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017, 129). A few journalists effectively left journalism for other professional fields during this study because, among other reasons, they felt they were not able to live up to their investigative standards. But giving up can also manifest as changing positions or publishers to work in newsrooms the journalists see as more committed to investigative journalism. In addition, the narratives showed that some journalists who had not (yet) given up continually alternated between an extraordinary investigative commitment and a “nearly drop-out” rhetoric. For instance, one journalist told us he felt like carrying on, but later said he completely lost his energy: “I think I need to move on. And if I’m given three days to investigate, well, it's just bonus.”Footnote14 Another expressed a similar, but conflicted, desire to give up: “I’m tired […] Sometimes I think I’m going to be a cultural journalist or something. Oh, I shouldn't say that, because I think that cultural journalists are not critical and investigative enough, and they are so mainstream … .”.Footnote15 While this theme emerged in all the narratives at various levels, the “stay strong” journalists who remained exclusively committed to investigative journalism were in the minority.

Get Perspective: Negotiation, Contestation, Combination, Re-creation

However, most journalists seemed to navigate (sometimes easily, sometimes less so) among multiple role orientations by continually negotiating the balance between their investigative commitment and their broader professional commitment. The narratives reflected an investigative commitment that comes and goes—sometimes smoothly, sometimes erratically for want of anything better—due to the journalists’ ability to negotiate resources with their colleagues and/or managers as described above. This was linked to the journalists’ reliance on progressive, flexible definitions of investigative journalism as being on a continuum, a concept emphasized in previous research (Cancela, Gerber, and Dubied Citation2021; see also Mcquail Citation2013). Rather than thinking of themselves as always investigating or never investigating, most reporters described themselves as “always investigating a little”. This way, journalists were able to give meaning to their work as a whole, while negotiating and re-creating investigative ideals:

Investigative reporting requires more than two phone calls, but it doesn't have to be Watergate either. (…) it can also be … you have a good tip, and you try to work on it (…) who did what, how, how many people, etc. So, this is a small investigative report, but it's still an investigative report in my opinion.Footnote16

I won't do my job any differently if I’m doing a portrait of someone—a positive portrait or about someone who has achieved something, etc (…)—than if I’m doing an investigation or something about a [wrongdoing]. To me, I do my job exactly the same way. Footnote17

You can't afford to dig around all the time. A typical example is an earthquake in Italy. On the first day, you’re going to report on the victims, and do interviews in the field. Now is not the time for investigative reporting! You are dealing with pure reporting. You just want to know what happened. And then, maybe, a month later, you start an investigation to know if there was a defect with the construction of the buildings. I’m not saying that one is better than the other, it's just that you have to … there's room for everything. And investigative reporting is the “finest”, the coolest, I think, we need it. But still, it depends on resources and time. While the rest, hard news coverage, has nothing to do with that and will always stay [no matter the resources put into the newsroom].Footnote18

Discussion

Liquid Positionings and the Vigilante Role

Interestingly, a broad qualitative analysis of the narrated roles reveals that very few journalists were able to provide a coherent narrative about roles. They tended to give quite absolute accounts when they were explicitly asked to speak about their professional ideals. In contrast, narratives about day-to-day practice and work processes revealed much more flexible attitudes towards roles and ideals. This contradiction was in fact predicted by Hanitzsch and Vos’ (Citation2017, 127–129) model, which shows narrated roles as informing discourse at two distinct levels: at the normative level, through the feedback process of role normalization/contestation, and at the cognitive level, through role negotiation.

Hence, the results indicated that most of the investigative journalists combined traditional role orientations with new narratives, and that some even see themselves as storytellers and “content producers” (Koljonen Citation2013, 144) as much as investigators. Several journalists spoke of the need to provide information that the public is actually concerned with (i.e., considering the audience both as citizens and as consumers), while most said they were also willing to provide knowledge and critical thinking to the public, which is more on the developmental-educative axis. In sum, the narratives demonstrated the overall journalists’ desire to make a difference, not only on democratic and editorial levels, but also on a commercial level. One journalist gave a good example of this “liquid” positioning:

People really want depth, to understand the world. This is where you have to race. We have to uncover stories that affect people directly, that affects their money, I don't know … I think we have a role to play here. By saying what everyone else is saying … we won't keep on existing and differentiating ourselves in this way. That what investigative journalism is for. Footnote19

The vigilante role should not be confused with activism. Lemieux (Citation2001, 57–58) already observed a similar stance among French journalists and stated that “[investigative journalism] allows undertaking a personal need for justice, but without ever leaving the tight circle of professional distancing” (our translationFootnote21). cholarly literature informs about this ambivalence: the norm of objectivity is a cornerstone of modern journalism and professional identity (Deuze Citation2005), and journalists partly reframe their narrated role performance so that it maps onto the norms of the profession, including (hegemonic) objectivity (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017). This issue was already raised by Ettema and Glasser (Citation1998) who remarked that even if investigative journalists implicitly assume that their stories help to define the boundaries of right and wrong, they still claim objectivity.

Thus, the vigilante role appears as a feature of investigative journalism's ideology—which Ettema and Glasser (Citation2006, 138) say is “unabashedly moralistic” compared to that of daily journalism. This may be true for most of the interviewed journalists, even though a small number of them were reluctant to explicitly endorse it. As suggested by Skovsgaard et al. (Citation2013), objectivity acts as a powerful “protective shield against criticism”, particularly for investigative journalists. This was strongly reflected in the narratives:

I am not here to punish or judge anyone, no matter who they are or what they did. I am not … Sometimes I have to remind people that I am not a judge, or a cop, and that I work for the public good […] that I’m going to let other sides have their say too, that I’m going to balance things out. […] The difficulty is to come up with stories that are … thoroughly cross-checked, to stick to the facts in order to avoid any criticism, of course, but above all not to weaken the credibility of the story.Footnote22

A Model of Narrated Negotiation of Investigative Commitment

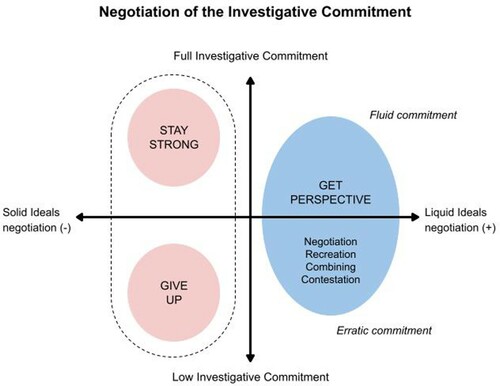

We have shown that journalists negotiate on a daily basis in order to find consistency between their role orientations and their day-to-day practices. The narratives allow us to identify a pattern that points to three strategies for these role negotiations: stay strong on investigative commitment, give up, or get perspective. Based on our analysis, we present a two-dimensional model of journalists’ narrated role negotiation regarding investigative commitment (see )—sometimes both dimensions were present in the same narrative.

The first coping strategy involves minimal negotiation and consists of two poles: staying strong on one's investigative commitment versus giving up. In both cases, the journalists conceive of their ideals in a very “solid” way. Consequently, a stay-strong strategy consists of not sparing efforts regarding investigative commitment. In contrast, the second coping strategy involves continual negotiation of investigative commitment in order to get perspective on one's standards—which relies on more balanced ideals. For example, journalists that use this strategy value daily news and exclusivity almost as much as depth, accuracy, and investigative techniques.

This involves re-evaluating certain idealistic myths in a practical light. For instance, some journalists mentioned the emergence of new collaborations between colleagues and peers of competitive media outside the official investigation networks active in Switzerland,Footnote23 which runs counter to the individualistic image of the investigative reporter alone against all (Carson Citation2019, 147; Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014, 220). Furthermore, they were quite pragmatic and emancipated from their ideals in concrete situations, notably with regard to autonomy and independence. For instance, they deliberately maintained ambivalent relationships with their sources, published their stories slightly early in order to maximize the media noise and/or beat the competition, turned banal news into big, marketable stories, etc. Thus, investigative journalists combine and juggle various different journalistic roles—sometimes complementary, sometimes contradictory.

Conclusion

Qualitative research on roles, role enactment and related professional commitment is still in its early stages. This study aspires to help fill the gap in this area, although further research is needed to explore what overall factors lead journalists to enter one zone of negotiation or the other. Despite this study's limitations, including its small geographical scope which limits generalization and the fact that it only looks at what investigative journalists say they do (and not their actual performance), it has important implications for further scholarship. Notably, there is a need to examine more closely the various causes of discrepancies between ideals and practices and how journalists experience them, an issue this study has begun to address.

We have argued that most investigative journalists are not crushed by the weight of journalistic norms and the gap between ideals and everyday practice, even though they subscribe to a strong ideology. Rather, journalists cope with it by negotiating their investigative commitment depending on the circumstances, a process which this study has attempted to conceptualize. We have highlighted various coping and reinvention strategies present in frustrating work contexts and suggested that they are closely interrelated with professional identity and institutional norms. This deserves further examination in various contexts. Notably, this calls for new ethnographic follow-up studies on journalistic work as it is actually performed by (investigative) journalists, a topic that only media content analysis and survey research have addressed so far (Mellado et al. Citation2020; Raemy, Beck, and Hellmueller Citation2018; Tandoc, Hellmueller, and Vos Citation2013).

What this study has shown is that journalists, especially investigative journalists, do not passively inhabit their institutionalized roles, which form a part of their professional identity (Deuze Citation2005). Obviously, their identity is also influenced by institutional, organizational and individual factors. As was the case for digital journalism (see Ferrucci and Vos Citation2017; Pignard-Cheynel and Sebbah Citation2013), the findings indicate that some investigative reporters have a fluid identity: they show great flexibility with regard to their role conceptions and individual perceptions of their role performance. This suggests that investigative journalists are highly aware of the discrepancies between watchdog roles and performance and are able to provide good reasons for them. More importantly, however, it shows that these reporters are capable of pursuing innovative strategies for adapting to changes in the field—something only context-sensitive approaches, which give a voice to stakeholders, can capture.

While only a few investigative journalists reported feeling comfortable juggling different roles, most were capable of generating creative solutions. These included, for example, sidestepping managers’ expectations by investigating during unpaid leave; taking advantage of news to fuel investigative projects and vice versa; seeking out two-way exchanges with sources; challenging competing outlets by creating new collaborations; alternating between large and “smaller” investigations; and in the case of some privileged journalists, taking advantage of their dominant position in the field to create or gain investigative status and more privileges—even if this latter strategy proves to be not as effective as expected in the long run without the support of skilled managers (Cancela Citation2021; Van Eijk Citation2005).

The study's findings therefore point to an important suggestion for media management, particularly investigative management: it would seem in the interest of managers (and journalists themselves) to ensure that as many reporters as possible enter the “liquid” zone of negotiation regarding investigative commitment. While “solid” coping strategies may allow investigative journalists to live up to their standards no matter their working conditions, this comes with an important cost both for individuals and organizations. In practice, the workload turns out to be exhausting, in addition to the already challenging and complex nature of investigative topics and techniques (Carson Citation2019; Kaplan Citation2008). In this sense, Pihl-Thingvad’s (Citation2015, 406) recommendation for managers resonates even more strongly in the investigative context:

Management must pay attention to and secure an appropriate balance between professional ideals and daily practice in their organization. This task should not be a matter of aligning journalists’ professional ideals with reality, because ideals are always superior to reality. A more constructive approach would be to clarify the journalists’ expectations with regard to their specific assignments and negotiate these in relation to the organization's goals.

Acknowlegements

We would like to thank all the people who have been or are currently involved with this project, and in particular Ph.D. Lena Wuergler and David Gerber for their contribution to the data collection.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this respect, and because the very definition of investigative journalism is still unclear (Cancela, Gerber, and Dubied Citation2021; Labarthe Citation2020; Wuergler Citation2021), this study considers an investigative journalist as a beat reporter who claims (and partly performs) an investigative commitment and/or benefits from special investigative status in the newsroom.

2 We refer to the concepts of solid and liquid, where “liquid journalism” captures the important shift in values within journalism and the evolving nature of journalistic work, that has been increasingly reorganized “in ways that make it more flexible, multi-skilled and assertive, or even ‘liquid’” (Kantola Citation2013, 606). Thus, we use “liquid” in its descriptive dimension, which does not (necessarily) imply a intrinsic pejorative dimension, as is the case when it is used e.g., by the sociologist Zygmunt Baumann.

3 J 1, interview of 28.11.2017

4 J2, interview of 06.12.2017

5 J 3, interview of 06.12.2017

6 J 3, interview of 06.12.2017

7 J 9, interview of 15.01.2018

8 J 22, interview of 12.11.2019

9 J 1, interview on 28/11/2017

10 J 3, interview on 06/12/2017

11 J 10, interview on 31/01/2018

12 J 4, interview of 20.12.2017

13 J 10, interview of 31.01.2018

14 J 17, interview of 12.12.2018

15 J 7, interview of 22.01.2018

16 J 34, interview of 21.11.2019

17 J 10, interview of 31.01.2018

18 J 12, interview of 16.11.2017

19 J 25, interview of 21.11.2019

20 The French sociologue Lemieux (Citation2001) developed a similar idea two decades ago, to which he refers interchangeably as “attitude justicière”, “pretention à la justice”, or even “figure de justice”, in an early study of the rise of investigative journalism in France.

21 « [le journalisme d’investigation] permet en ce sens de faire travailler un besoin de justice d’ordre personnel, mais sans jamais sortir néanmoins du cercle étroit de la distanciation professionnelle. »

22 J 4, interview of 20.12.2017

23 Including Investigativ.ch, International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and European Investigative Collaborations (EIC).

References

- Alvesson, M. 2004. Knowledge Work and Knowledge-Intensive Firms. New York: OUP Oxford.

- Berkowitz, D. 2007. “Professional Views, Community News; Investigative Reporting in Small US Dailies.” Journalism 8 (5): 551–558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884907081051

- Bonfadelli, H., G. Keel, M. Marr, and V. Wyss. 2011. “Journalists in Switzerland: Structures and Attitudes.” Studies in Communication Sciences 11 (2): 7–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-69399.

- Bonin, G., F. Dingerkus, A. Dubied, S. Mertens, H. Rollwagen, V. Sacco, I. Shapiro, O. Standaert, and V. Wyss. 2017. “Quelle Différence? Language, Culture and Nationality as Influences on Francophone Journalists’ Identity.” Journalism Studies 18 (5): 536–554. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1272065.

- Brennen, B. S. 2017. Qualitative Research Methods for Media Studies. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315435978.

- Bryant, A., and K. Charmaz, eds. 2010. The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. London: Sage. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526485656.

- Cancela, P. 2021. “Between Structures and Identities: Newsroom Policies, Division of Labor and Journalists’ Commitment to Investigative Reporting.” Journalism Practice. Advance online publication: 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1971549.

- Cancela, P., D. Gerber, and A. Dubied. 2021. “‘To Me, It’s Normal Journalism’ Professional Perceptions of Investigative Journalism and Evaluations of Personal Commitment.” Journalism Practice 15 (6): 878–893. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1876525.

- Carson, A. 2019. Investigative Journalism, Democracy and the Digital Age. New York: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315514291.

- Deuze, M. 2005. “What Is Journalism? Professional Identity and Ideology of Journalists Reconsidered.” Journalism 6 (4): 442–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884905056815.

- Deuze, M. 2008. “The Changing Context of News Work: Liquid Journalism for a Monitorial Citizenry.” International Journal of Communication 2: 848–865.

- Deuze, M., and T. Witschge. 2020. Beyond Journalism. 1st ed. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity.

- Dingerkus, F., A. Dubied, G. Keel, V. Sacco, and V. Wyss. 2018. “Journalists in Switzerland: Structures and Attitudes Revisited.” Studies in Communication Sciences 18 (1): 117–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.24434/j.scoms.2018.01.008.

- Ettema, J. S., and T. L. Glasser. 1998. Custodians of Conscience: Investigative Journalism and Public Virtue. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ettema, J. S., and T. L. Glasser. 2006. “On the Epistemology of Investigative Journalism.” In Journalism: The Democratic Craft, edited by G. S. Adam, and R. P. Clark, 126–140. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ferrucci, P., and T. Vos. 2017. “Who’s In, Who’s Out?” Digital Journalism 5 (7): 868–883. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1208054.

- Grubenmann, S., and M. Meckel. 2017. “Journalists’ Professional Identity.” Journalism Studies 18 (6): 732–748. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2015.1087812.

- Hallin, D., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hamilton, J. T. 2016. Democracy’s Detectives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hanitzsch, T. 2007. “Deconstructing Journalism Culture: Toward a Universal Theory.” Communication Theory 17 (4): 367–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00303.x.

- Hanitzsch, T., F. Hanusch, J. Ramaprasad, and A. S. de Beer, eds. 2019. Worlds of Journalism: Journalistic Cultures Around the Globe. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hanitzsch, T., and T. P. Vos. 2017. “Journalistic Roles and the Struggle Over Institutional Identity: The Discursive Constitution of Journalism.” Communication Theory 27 (2): 115–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12112.

- Hanitzsch, T., and T. P. Vos. 2018. “Journalism Beyond Democracy: A New Look into Journalistic Roles in Political and Everyday Life.” Journalism 19 (2): 146–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916673386.

- Hunter, M. 1997. Le journalisme d'investigation aux États-Unis et en France. Paris: PUF.

- Kantola, A. 2013. “From Gardeners to Revolutionaries: The Rise of the Liquid Ethos in Political Journalism.” Journalism 14 (5): 606–626. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884912454504.

- Kantola, A. 2016. “Liquid Journalism.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 424–441. London; Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Kaplan, A. D. 2008. Investigating the Investigators: Examining the Attitudes, Perceptions, and Experiences, of Investigative Journalism in the Internet Age. College Park: University of Maryland.

- Koljonen, K. 2013. “The Shift from High to Liquid Ideals: Making Sense of Journalism and Its Change Through a Multidimensional Model.” Nordicom Review 34 (s1): 141–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2013-0110.

- Konow-Lund, M. 2020. “Reconstructing Investigative Journalism at Emerging Organisations.” The Journal of Media Innovations 6 (1): 9–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.5617/jomi.7830.

- Kovach, B., and T. Rosenstiel. 2014. The Elements of Journalism, Revised and Updated 3rd Edition: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. 3rd ed. New York: Crown.

- Labarthe, G. 2020. Mener l’enquête. Arts de faire, stratégies et tactiques d’investigation de journalistes. Lausanne: Antipodes.

- Lacroix, C., and M. E. Carignan. 2020. “Une crise dans la crise : comment les journalistes perçoivent-ils leurs rôles et leur avenir en temps de pandémie ?” Les Cahiers du Journalisme – Recherches 2 (5): R3–R18. doi:https://doi.org/10.31188/CaJsm.2(5).2020.R003.

- Le Cam, F., F. H. Pereira, and D. Ruellan. 2019. “Professional Identity of Journalists.” The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0241.

- Lemieux, C. 2001. “Les formats de l’égalitarisme : transformations et limites de la figure du journalisme-justicier dans la France contemporaine.” Quaderni 45 (1): 53–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.3406/quad.2001.1497.

- MacFayden, G. 2008. “The Practices of Investigative Journalism.” In Investigative Journalism, edited by G. MacFayden, 138–156. New York: Routledge.

- Marchetti, D. 2000. “Les révélations du ‘journalisme d’investigation’.” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 131 (1): 30–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.3406/arss.2000.2663.

- Matheson, D. 2009. “The Watchdog’s New Bark: The Changing Roles of Investigative Reporting.” In The Routledge Companion to News and Journalism, edited by S. Allan, 82–92. New York: Routledge.

- McQuail, D. 2013. Journalism and Society. 1st ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Mellado, C. 2015. “Professional Roles in News Content.” Journalism Studies 16 (4): 596–614. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.922276.

- Mellado, C., C. Mothes, D. C. Hallin, M. L. Humanes, M. Lauber, J. Mick, H. Silke, et al. 2020. “Investigating the Gap Between Newspaper Journalists’ Role Conceptions and Role Performance in Nine European, Asian, and Latin American Countries.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (4): 552–575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220910106.

- Mellado, C., and A. van Dalen. 2014. “Between Rhetoric and Practice.” Journalism Studies 15 (6): 859–878. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.838046.

- Neveu, E. 2013. Sociologie du journalisme. Paris: La Découverte.

- Neveu, E. 2019. Sociologie du journalisme. Paris: La Découverte. Accessed 7 September 2021. https://www.cairn.info/sociologie-du-journalisme--9782348041846.htm.

- Nord, L. W. 2007. “Investigative Journalism in Sweden: A Not so Noticeable Noble Art.” Journalism 8 (5): 517–521.

- Pignard-Cheynel, N., and B. Sebbah. 2013. “L’identité des journalistes du Web dans des récits de soi.” Communication [en ligne] 23 (2). doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/communication.5045.

- Pihl-Thingvad, S. 2015. “Professional Ideals and Daily Practice in Journalism.” Journalism 16 (3): 392–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913517658.

- Raemy, P., D. Beck, and L. Hellmueller. 2018. “Swiss Journalists’ Role Performance: The Relationship Between Conceptualized, Narrated, and Practiced Roles.” Journalism Studies, 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1423631.

- Raemy, P., L. Hellmueller, and D. Beck. 2018. “Journalists’ Contributions to Political Life in Switzerland: Professional Role Conceptions and Perceptions of Role Enactment.” Journalism 20 (6): 765–782. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918802542.

- Raemy, P., and T. P. Vos. 2020. “A Negotiative Theory of Journalistic Roles.” Communication Theory, qtaa030. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtaa030.

- Ruellan, D. 2001. “Socialisation des journalistes entrant dans la profession.” Quaderni 45 (1): 137–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.3406/quad.2001.1501.

- Ruellan, D. 2007. Le Journalisme ou le professionnalisme du flou. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble.

- Schudson, M. 1996. The Power of News. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Shoemaker, P. J., and S. D. Reese. 2014. Mediating the Message in the 21st Century. New York: Routledge.

- Skovsgaard, M., E. Albæk, P. Bro, and C. de Vreese. 2013. “A Reality Check: How Journalists’ Role Perceptions Impact their Implementation of the Objectivity Norm.” Journalism 14 (1): 22–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884912442286.

- Standaert, O., T. Hanitzsch, and J. Dedonder. 2019. “In Their Own Words: A Normative-Empirical Approach to Journalistic Roles Around the World.” Journalism 22 (4): 919–936. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919853183.

- Stetka, V., and H. Örnebring. 2013. “Investigative Journalism in Central and Eastern Europe: Autonomy, Business Models, and Democratic Roles.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 18 (4): 413–435. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161213495921.

- Tandoc, E. C., L. Hellmueller, and T. P. Vos. 2013. “Mind the Gap.” Journalism Practice 7 (5): 539–554. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2012.726503.

- Van Eijk, D. 2005. Investigative Journalism in Europe. Amsterdam: Vereniging van Onderzoeksjournalisten.

- Weaver, D. H., L. Willnat, and G. C. Wilhoit. 2019. “The American Journalist in the Digital Age: Another Look at U.S. News People.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (1): 101–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018778242.

- Wiik, J. 2009. “Identities Under Construction: Professional Journalism in a Phase of Destabilization.” International Review of Sociology 19 (2): 351–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03906700902833676.

- Witschge, T., and F. Harbers. 2018. “Journalism as Practice.” In Journalism, edited by T. P. Vos, 105–124. Boston; Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501500084-006.

- Wuergler, L. 2021. “L’événement comme support de légitimation du journalisme d’enquête.” Communication [en ligne] 38 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/communication.13974.

- Zelizer, B. 1993. “Journalists as Interpretive Communities.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 10 (3): 219–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15295039309366865