ABSTRACT

Journalists increasingly have to cope with severe attacks – ranging from Fake News accusations to violence and death threats. To better understand how journalists can counter delegitimizing attacks such as anti-media populism and online harassment, this study examines their paradigm repair strategies to ward off assaults in the unconsolidated democracy of the Philippines. Through in-depth semi-structured interviews with 18 Filipino reporters and editors from three influential media outlets that then President Rodrigo Duterte targeted as enemies – the broadcaster ABS-CBN, the newspaper Philippine Daily Inquirer, and the website Rappler – this paper offers novel insights on journalists’ counterstrategies with appeals to their strengthened roles as watchdogs, interpreters and disseminators of populist communication. Findings indicate that journalists discard practices like false equivalence and shift roles including from being detached observers to media freedom advocates and truth activists to respond to institutional attacks, rising disinformation, and perceived democratic erosion as they seek to speak truth to a populist in power. The study provides theoretical and empirical contributions by combining paradigm repair and role perceptions as tools in analyzing journalists’ responses to legitimacy threats, and by presenting an understudied case of anti-media populism in the Global South.

“Since you are a fake news outlet then I am not surprised that your articles are also fake.” Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte railed against reporters’ “oligarch” owners and called them “trash,” drawing from the authoritarian populist toolkit to discredit journalists (Coronel Citation2020). Donald Trump’s “enemy of the people” label, and the Lügenpresse (lying press) tag of Germany’s right-wing movement Pegida are similar tactics of delegitimizing discourse, emphasizing a populist antagonism between “good people” and “corrupt journalists” counted as part of the elite (Krämer Citation2018). Scholars and media groups describe the recent rise of populist media criticism as a press freedom threat, inciting offline and online violence and undermining trust in journalism even in established democracies (Freedom House Citation2018). While Trump’s Fake News accusations and Lügenpresse are familiar research subjects, Duterte offers a powerful understudied case of anti-media populism in the Global South, worsening the environment in one of the most dangerous places to practice journalism where provincial correspondents are murdered for their reporting (Beiser Citation2020).

With right-wing populists challenging institutional media legitimacy, understanding how journalists can defend their authority is crucial (Lawrence and Moon Citation2021). In the Philippines, the dilemma was compounded by a leader whose extreme brand of “violent populism” legitimized mass killings (Thompson Citation2021). Elected in 2016 on a promise to end crime by killing drug offenders, Duterte’s government faces investigation at the International Criminal Court (Citation2021) over alleged extrajudicial killings during his presidency, which ended in June 2022. His verbal and legal threats to journalists occurred in a country having one of Asia’s most freewheeling media while consistently landing on impunity indices for unsolved killings of reporters (Beiser Citation2020). To understand how journalists respond to hostile attacks in this setting, this paper examines how they countered threats and viewed their functions in these perilous times.

Although many studies detail populists’ tactics to discredit the media in the United States and Western Europe (e.g., Fawzi Citation2019), little is known about journalists’ response, especially in Global South democracies where weak institutions are vulnerable to populism’s negative effects (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2012). This paper explores how journalists respond to delegitimizing populist narratives, which blame journalists for deceiving the people and for spreading fake news. These populist narratives emphasize hostility against elite actors such as journalists and established experts, and emphasize that these “evil” outsiders are not representing the people’s voice. The populist delegitimization of journalists has crucial implications as these attacks impair the media’s function as the fourth estate. Responding to the call for studies on journalistic responses to populists’ delegitimizing efforts, this paper raises the overarching research question: How do Filipino journalists respond to Duterte’s delegitimizing populist attacks? Specifically, (1) What paradigm repair strategies do they use against delegitimizing populism and why, and (2) How do they perceive their roles in relation to these strategies? In analyzing how journalists defend their work from a populist’s assaults, this paper expands paradigm repair literature by focusing on an external threat as an understudied element (Whipple and Shermak Citation2020). It takes populism research beyond familiar settings in Europe and the Americas by presenting an interesting case of journalistic responses to a right-wing populist leader in Asia.

Through semi-structured interviews with 18 reporters and editors from three critical outlets that Duterte targeted as enemies, this article offers insights on journalists’ pushback that integrates strategies ranging from reporting to advocacy with appeals to their roles as watchdogs, interpreters and disseminators of populist communication. Such defensive tactics are encapsulated in #DefendPressFreedom, a rallying cry in offline and online protests expressing solidarity, activism and resistance. Analyzing views from the frontlines, the paper discusses how journalists adjust their counterstrategies to fulfill roles that have become more essential in responding to institutional assaults and populist disinformation. It hereby offers a contribution to understanding journalistic role perceptions and paradigm repair in the face of a global trend towards delegitimizing attacks, violence and hostility against journalists.

Delegitimizing Anti-Media Populism

In this paper, we focus on the populist delegitimization of journalists and the media (see e.g., Krämer Citation2018). Although media critique is common and arguably part of a well-functioning democracy, the populist delegitimization of the media can take on more disruptive forms as it emphasizes hostility against journalists, for example, by blaming them for spreading fake news, legitimizing media violence, or discursively constructing journalists as an enemy of the people (e.g., Fawzi Citation2019). More than regular and substantive forms of media critique, the populist delegitimization of the media attacks the roles and principles that form the heart of journalism. Its hostile attacks cast doubt on the impartiality, independence and honesty of journalistic role perceptions.

As the populist delegitimization of the media may express severe distrust and hostility toward journalists and their profession, and may even undermine their societal role, this paper explores how journalists respond to delegitimizing threats through paradigm repair. Before delving into these responses, we will dissect the core elements of populist delegitimization attacks, including anti-media populism and fake news accusations. Here, we regard populism as an ideology dividing society into “two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people' versus ‘the corrupt elite'” (Mudde Citation2004, 543). It has three elements: (1) people-centrism or appeals to the people, (2) anti-elitism pitting the people against “bad elites” such as politicians and journalists, and (3) an (optional) exclusion strategy stigmatizing out-groups like immigrants (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007). In its binary political vision, populism depicts elites and out-groups as diabolical enemies of the virtuous people (Mudde Citation2004).

This study emphasizes journalists’ role as subjects of populists’ delegitimizing attacks. A specific form of populism aligned with our conceptualization of the populist delegitimization of journalists is anti-media populism. Anti-media populism accuses “bad journalists” of conspiring with elites and betraying the people (Fawzi Citation2020; Krämer Citation2018). This attitude is based on a hostile media syndrome blaming journalists for being the mouthpiece of elite and corporate interests, rather than representing the true voice of the people (Waisbord and Amado Citation2017). Anti-media populism finds expression in delegitimizing rhetoric characterized by an absence of reasoning or the presence of incivility (Egelhofer, Aaldering, and Lecheler Citation2021). Absence of reasoning refers to sweeping media criticism without refutable arguments. As institutionalized delegitimization, this criticism is directed at the entire media instead of specific reporters or news items (Panievsky Citation2021). Incivility captures the hateful tone populists use to demarcate journalists as "evil" outsiders. Lacking substantiation and constructive language or intent, anti-media populist rhetoric can then more precisely be regarded as attacks on than mere criticism of the press (Fawzi Citation2020).

The populist delegitimization of journalists can come in different forms, such as the expression that journalists are corrupt, biased or an enemy of the people. Fulfilling the stated characteristics of unjustified and uncivil messages, fake news labels are a prime example of delegitimizing media criticism in their wholesale, harsh accusation that the media lies to the people (Egelhofer, Aaldering, and Lecheler Citation2021). Such labels stress the populist opposition between “honest” people and “corrupt” media elites accused of deceiving the people by spreading disinformation. Although the term fake news could be used to describe false information that is intentionally deceptive whilst mimicking actual news formats (e.g., Gelfert Citation2018) or a form of media critique that reveals journalism’s weaknesses (Borden and Tew Citation2007), we focus on “fake news” as a delegitimizing accusation. The term has been used as a catch-all phrase by many political and non-political actors to attack established journalists and rival politicians, blaming them for intentionally disseminating falsehoods (Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019). This accusation aligns with a hostile media bias: outlets or individual journalists are blamed for spreading “fake news” when the messages they convey are critical of or incongruent with the accuser’s positions – irrespective of the veracity or honesty of the delegitimized claims (Hameleers Citation2020).

Anti-media populist rhetoric has detrimental effects on media trust and journalists’ work conditions and safety. Experiments show that politicians’ media criticism in general convinces people that the press is biased even when no such bias exists (Smith Citation2010). Anti-elitism in particular predicted low media trust in a survey of German citizens (Fawzi Citation2019). Populists’ anti-media discourse likewise has a spill-over effect to their supporters and fellow politicians such as the “fake news contagion” evidenced in Australian parliamentarians’ use of the label after Trump’s election (Farhall et al. Citation2019). There are also direct effects on journalists. Interviews found a “populist chilling mechanism” where Israeli journalists practiced self-censorship to refute accusations of bias (Panievsky Citation2021). The frequency of politicians’ anti-media rhetoric even predicted violence against Venezuelan journalists (Mazzaro Citation2021). Overall, these findings illustrate the dangers that anti-media populist discourse poses to press freedom, especially when unchallenged and thus normalized. Press freedom is the absence of media restraints, and the presence of conditions for disseminating diverse ideas (Weaver Citation1977). Populists combine anti-media messages with actions like regulation to threaten this journalistic imperative. In line with the call for journalists to defend press freedom from rhetorical fire (Panievsky Citation2021), this study analyzes how they respond to such attacks – which have taken extremely hostile forms in recent years.

Multiple studies enumerate examples of populists’ delegitimization of the media forming a playbook of strategies where social media is the hotbed of vitriol. Trump insulted reporters on Twitter (Lawrence and Moon Citation2021) while German journalists encounter numerous Lügenpresse accusations on digital platforms (Koliska and Assmann Citation2019). In the Global South, social media plays a pivotal role enabling supporters to propagate populist leaders’ anti-press sentiments, but the issue remains understudied in this context. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s followers use Twitter and right-wing outlets to highlight mainstream media’s mistakes and undermine journalistic accuracy (Bhat and Chadha Citation2020). In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro’s “Bolsominions” spread WhatsApp memes channeling the president’s contempt for established media (Horbyk et al. Citation2021). In Latin America, in turn, populists harass critical journalists on Twitter (Waisbord and Amado Citation2017) while Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s troll army lynches reporters on the same platform (Bulut and Yörük Citation2017).

These examples notwithstanding, research on journalists’ responses to delegitimizing populist attacks is scarce despite the relevance of understanding how they defend a democratic pillar. Waisbord (Citation2020) argues that “mob censorship” rooted in a populist demonization of the press is a free speech issue. As populists weaponize misogyny, online harassment targets female journalists, undermining their reporting while attacking their gender (Posetti et al. Citation2021). In developing countries like Brazil (Posetti et al. Citation2021), India and Pakistan (Jamil and Sohal Citation2021), outspoken women journalists face rape threats and sexist slurs on social media aimed at silencing them. These attacks link to the broader trend of increasing media violence in otherwise peaceful democracies in recent decades due to compromised digital security and partisan politics turning journalists into state enemies (Cottle, Sambrook, and Mosdell Citation2016). Hence, journalists face a hostile context beyond politics, with both politicians and ordinary citizens using digital platforms to express deep distrust in their capabilities to honestly inform the public (Hameleers et al. Citation2021).

Although we acknowledge this wider societal context of rising media antagonism, we focus on journalists’ responses to harassment induced by a radical right-wing populist. In our study’s context, Duterte exemplifies anti-media populism through threats against news organizations that critically reported on his drug war (Coronel Citation2020). Alongside the fake news label, his profanities calling journalists “sons of whores” elites and “full of shit” are quintessential anti-media rhetoric: indiscriminate and crass. Besides Duterte’s tirades and his administration’s regulations against these outlets, social media is a hub of toxic incivility. As with India and Brazil, Duterte supporters and “click armies” bullied critical journalists with death threats and vitriolic trolling that could escalate to physical harm (Ong and Cabañes Citation2018). Women journalists perceived as anti-Duterte faced systematic harassment on Facebook and Twitter through rape threats, demeaning memes and insults like “presstitute” (Tandoc, Sagun, and Alvarez Citation2021). The Reuters Institute named Duterte’s threats a potential reason trust in Philippine media ranked among the lowest of 40 countries (Chua Citation2020). Unlike research on specific attacks like Lügenpresse, this study aims to identify journalists’ response to Duterte’s multipronged approach of vilification, regulations, lawsuits and trolls.

In sum, anti-media populism is a specific form of populism that emphasizes elite hostility toward the media, stemming from the populist ideology’s anti-elitist dimension. Its delegitimizing media criticism has two main characteristics: generic, unsubstantiated accusations and an uncivil tone. The fake news label is one prominent example of anti-media populist discourse, which along with actions like media shutdowns constitute delegitimizing threats and restrict press freedom. This study examines how journalists respond to anti-media populism in the Philippines where Duterte used such a combination of tactics against the critical press. The question of how journalists navigate this challenge remains: To what extent do they stick to existing role perceptions, and how can they defend a profession facing severe delegitimizing attacks?

Paradigm Repair and Role Perceptions

Journalists respond to legitimacy threats through paradigm repair, re-introducing journalism and its role to justify its existence and to bind the community in times of stress (Berkowitz Citation2000). Paradigm repair is traditionally a response to internal lapses of individual journalists who are isolated and scapegoated (Cecil Citation2002). This ritual restores faith in the paradigm, showing that the institution remains intact (Berkowitz Citation2000). However, paradigm repair has also been applied to outside threats like anti-media populism, which requires heavier repair work as it assaults the institution, not just single reporters. Whipple and Shermak (Citation2020) used paradigm repair through content analysis to study the #NotTheEnemy Twitter discourse responding to Trump. Heeding these authors’ call for a deeper examination of journalists’ sentiments about populist animosity, this article uses interviews to analyze responses to this contemporary threat, thereby extending paradigm repair research.

Journalists use several strategies to repair their credibility. A classic one is reasserting objectivity. Krämer and Langmann (Citation2020) termed this professionalism, the appeal to follow norms more strictly. Similarly, the discourse around Lügenpresse prompted editors to stress objectivity (Koliska and Assmann Citation2019). Newer strategies include open confrontation as with editorials calling Trump authoritarian (Lawrence and Moon Citation2021).

The timing of anti-media populism has opened a debate on the viability of old defense mechanisms versus strategies reconsidering the paradigm following reflexivity on media’s role in populism’s rise. Populist criticism comes as journalists become vulnerable due to disrupted public spheres, losing their gatekeeper status in the transition to high-choice media environments (Van Aelst et al. Citation2017). Against this backdrop, some scholars argue that strategies invoking objectivity are unresponsive to changing times. Questioning false equivalence, Kovach and Rosenstiel (Citation2014) advocate for transparency and context. Some suggest taking a stance when press freedom is threatened (Beiler and Kiesler Citation2018) but others argue that combative tactics would confirm the populist framing of a partisan media (Lawrence and Moon Citation2021). Strategies questioning journalistic tenets fall under a new activity called paradigm reconsideration (Vos and Moore Citation2020). This article explores which strategies Filipino journalists employ, and how they defend the paradigm during a grueling period. Therefore, it asks (RQ1): What paradigm repair strategies do Filipino journalists use in response to Duterte’s populist attacks and why?

Closely related to paradigm repair are role perceptions, journalists’ self-image of their social functions (Hanitzsch Citation2011). Whereas paradigm repair concerns journalists’ strategies, role perceptions refer to journalists’ general ideas to legitimize their societal role. Role perceptions can then be understood as the rationale behind journalists’ tactics to defend their profession when it faces severe legitimacy threats in a populist era. Role perceptions, however, differ from role performances or how journalists live up to ideals given practical constraints (Hellmueller and Mellado Citation2015). It is, therefore, important to assess the discrepancy between the “ideal-type” roles journalists envision and their abilities to enact these functions in the Philippines where press freedom challenges may impede performing critical, interpretive functions.

We regard six functions from role perception typologies (Hanitzsch Citation2011; Weaver et al. Citation2007) as relevant to journalists’ response to anti-media populism. These roles reflect the range of “fight or flight” strategies that may be used either for a confrontational approach or to circumvent threats by remaining neutral to avoid delegitimizing attacks. The first more adversarial position is the interventionist role where journalists advocate for social change and take sides in disputes. This relates to strategies of activism and open confrontation. Second, the detached disseminator sticks to objectivity, consistent with the professionalism strategy. Third, the watchdog role investigates abuses, and holds actors accountable for failures. The fourth interpretive role included here has the function of providing analysis, moving beyond a passive dissemination of factual information. Fifth, the loyal facilitator role implies that journalists act as government’s partner, engaging in self-censorship. Finally, the civic role raises people’s concerns through public journalism, including citizens’ concerns in journalistic coverage.

Combinations and context factor into understanding these roles. First, except for the interventionist and disseminator as opposites, roles overlap. This is exemplified by Márquez-Ramírez and colleagues’ (Citation2020) framework of the interventionist watchdog and the detached watchdog, fusing the watchdog function with a more critical and a more passive voice, respectively. Second, roles are contingent on a hierarchy of influences (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014). Restricted political freedom and contextual events like polarization may motivate journalists to be interventionist (Márquez-Ramírez et al. Citation2020). Other predictors are the kind of outlet and newsroom environment (Weaver et al. Citation2007).

Philippine Media

Rife with contradictions, Philippine media is known for a rambunctious, American-modeled press regarded as one of the freest in Asia but having one of the world’s highest number of journalist killings (Coronel Citation2020). Despite laws guaranteeing press freedom, local journalists are murdered in broad daylight, with the killings largely unsolved due to a weak rule of law that led Freedom House (Citation2018) to classify the Philippines as “partly free.” Such culture of impunity and ineffective accountability institutions put it in the league of countries like Mexico, Pakistan and India, “insecure democracies” (Hughes et al. Citation2017) with severe non-conflict related media violence where low-paid journalists face risks for investigating corruption, rights abuses and crime (Cottle, Sambrook, and Mosdell Citation2016; Jamil and Sohal Citation2021). Watchdogs say Duterte’s anti-media rhetoric inflamed this already perilous situation (Freedom House Citation2018).

Duterte’s attacks highlighted a key vulnerability of Philippine media – wealthy business families’ concentrated ownership of influential outlets. This is the case for two of the three outlets he cracked down on and branded as “oligarchs” – the broadcaster ABS-CBN and the leading broadsheet Philippine Daily Inquirer (Tapsell Citation2021). Before Duterte’s congressional allies rejected its 2020 franchise renewal, ABS-CBN was the largest media conglomerate, reaching 97% of households (Vera Files & RSF Citation2016). The network is part of the Lopez family’s companies with businesses in energy (Vera Files & RSF Citation2016). The Inquirer is owned by the Rufino-Prieto family with real estate and fast-food businesses (Vera Files & RSF Citation2016). The newspaper’s owners were charged with tax evasion after its coverage earned Duterte’s ire (Chua Citation2020). The exception is independent website Rappler, founded and owned by journalists including ex-CNN reporter Maria Ressa who won the Nobel Peace Prize (Citation2021) for her “courageous fight for freedom of expression.” Ressa and Rappler journalists were sentenced to up to six years imprisonment for cyberlibel, banned from Duterte’s events, and face unabated online violence like calls for Ressa to be “publicly raped to death” (Posetti et al. Citation2021).

While research has shown that Filipino journalists lean toward being detached watchdogs (Márquez-Ramírez et al. Citation2020), no study has identified their role orientations in relation to Duterte’s attacks. Scholarship focused on Duterte’s divide-and-rule media strategy (Tapsell Citation2021). Facing mis- and disinformation, Filipino journalists cited the disseminator and watchdog roles as most important (Balod and Hameleers Citation2019). Arguably, the dangerous context cultivated by delegitimizing discourse targeted at journalists by right-wing populists and ordinary citizens call for different role perceptions than responding to socio-political developments in general. In this light, this study asks (RQ2): How do Filipino journalists perceive their roles in relation to their strategies against anti-media populism, and what are the barriers to enact these?

Method

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews with 18 Filipino journalists were conducted to yield rich data on paradigm repair and role perceptions by allowing them to emphasize angles while ensuring comparability (Bryman Citation2012). Following Stanyer and colleagues (Citation2019), we let journalists express views beyond box-ticking, contributing to rare populism studies examining their standpoint. In line with role conception literature (Hellmueller and Mellado Citation2015), interviews effectively collect data on roles’ complexities. The interview guide focused on views on populism, Duterte’s attacks, strategies, role perceptions and challenges – topics elaborating on the research questions (see Appendix C in supplementary online). Interviews adhered to prepared questions except to ask about specific attacks that the participant experienced.

Sampling

Interviewees were journalists from three national media outlets that scholars and press freedom groups named as direct targets of Duterte’s most severe attacks – ABS-CBN, the Philippine Daily Inquirer, and Rappler (RSF Citationn.d.). These outlets are categorized as enemies that Duterte singled out and threatened for their critical reporting, prompting tax evasion and libel suits, closure orders, online harassment, and in ABS-CBN’s case, the loss of its broadcasting franchise (Tapsell Citation2021). As part of populism’s binary strategy, they are contrasted against outlets friendly to Duterte. Following anti-media populism literature (Krämer and Langmann Citation2020), the cases are mainstream media that populists count as part of the elite. They are among the Philippines’ most influential and largest news companies, market leaders capturing broadcast, print and online media audiences (Vera Files & RSF Citation2016).

Purposive and snowball sampling were used to identify 18 reporters, editors, and news managers who could detail individual and organizational responses (see Appendix B for interviewees’ profiles in supplementary online). Interviewees were journalists Duterte criticized, and those facing government lawsuits and social media attacks by his supporters. For maximum variation, interviewees were of various ages, years of experience, and gender, totaling 6 per outlet. The researcher knew some participants from past journalism work while others were identified from recommendations. The sample size was finalized based on theoretical saturation where gathering fresh data no longer generated new categories (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). This is in line with qualitative research’s aim to generalize to theory than populations (Bryman Citation2012).

Interviews were conducted in March-April 2021, a year before Duterte’s term ended, letting journalists reflect with hindsight on his anti-media populism. Conducted on Zoom and Skype due to the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews lasted between 36 minutes and 1 hour and 55 minutes. These were done in English but the researcher, a Filipino speaker, translated some Filipino phrases. Participants consented to anonymous interviews due to security concerns.

Analysis

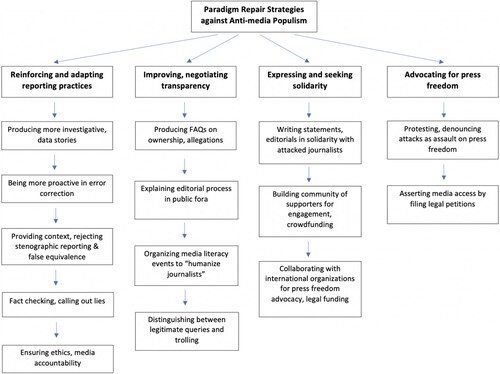

Transcripts were coded using the software Atlas.ti. The grounded theory method was used to analyze data, allowing theoretical ideas to emerge in a three-step, constant comparative and iterative process to find similarities and differences between themes (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). In open coding, line-by-line coding labeled segments of text based on sensitizing concepts in the research questions – paradigm repair, journalistic responses to attacks, role perceptions, and role performances. In focused coding, 900 open codes were merged into similar codes and raised into categories. This phase identified three main themes using the most significant codes: Strategies, Roles and Challenges. Finally, in axial coding, relationships were drawn by linking strategies and subcategories (see ), and relating roles with challenges (see Appendix A in supplementary online).

To ensure credibility and trustworthiness, peer debriefing and member checks were conducted. Coding steps and results were extensively discussed with an external researcher familiar with grounded theory and the Philippines. The second researcher affirmed that the coding procedure systematically reduced data. She gave two suggestions which were adopted: (1) rephrasing the category “improving transparency” to “improving, negotiating transparency” to capture nuances of the subcategory “distinguishing between legitimate queries and trolling,” and (2) incorporating supplementary themes of Lessons and Impact into the main ones. Two participants were also asked to review the themes. Interviewees said there was no major discrepancy between the results and their responses, attesting that some strategies and challenges were outlet-specific due to ownership differences.

Results

Paradigm Repair Strategies

Faced with a populist leader’s attacks, interviewees identified four paradigm repair strategies, answering RQ1: (1) reinforcing and adapting established reporting practices and norms, (2) improving and negotiating transparency on the editorial process, (3) expressing solidarity with colleagues, audiences, and the international community, and (4) advocating for press freedom (see ).

To fend off delegitimizing labels, one strand of reporting strategies used traditional journalistic tools like emphasizing objectivity, accuracy, balance and ethics. Most participants said persisting on exposing drug war abuses and corruption showed that they were not “cowed” but were even “unleashed” by the attacks. A reporter said her newspaper introduced quotas for investigative and data stories “to bolster the credibility of the Inquirer that it is still able to produce good journalism.” Being called dilawan (pro-opposition) and bayaran (corrupt) prompted some interviewees to double down on objectivity by strictly separating news from commentary. All participants said they became more proactive in verification, with mistakes “weaponized” against them. A reporter learned this when a typographical error triggered trolling:

I received lots of Facebook and Twitter messages saying, “What kind of reporter are you?” So, you should be very careful even about small details because it will give the president, his officials, his army of trolls the bullet to attack your credibility.

While journalists strengthened classic practices, half of the interviewees said they adapted routines as a second strand of reporting strategies. One salient change was in live-tweeting Duterte’s speeches, causing “soul searching” among reporters. Journalists cited the need for “instant factchecking and context,” and linking to background articles as officials were deliberately “peppering messages with lies.” A reporter explained:

Each tweet is a mini-news report. If I have space and time, and the lie is so blatant, I would really add context. It’s a disservice to people if you leave it at that.

Before, we would say, “Duterte flip-flopped. Duterte said this on Monday and on Tuesday, he said this.” That’s no longer the practice. You say Duterte lied because he said this on Monday, and said this on Tuesday.

The second strategy was improving and negotiating transparency about the editorial process. Reporters posted on social media documents substantiating their stories to address veracity questions. Rappler also produced FAQs about its ownership while ABS-CBN and Inquirer issued statements denying Duterte’s accusations of unfair reporting. One reporter perceived the “media as evil elite” label as arising from a lack of understanding about journalism. Interviewees thus organized media literacy workshops. “We speak in events to build trust, and to show people we’re not the monsters they paint us to be, to humanize the journalists,” a reporter said. One journalist granted dozens of interviews explaining lawsuits against her. Transparency also meant regularly covering the attacks, and investigating online disinformation campaigns.

While they answered readers’ questions, interviewees unanimously ignored trolls, calling trolling on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube a “universal experience.” Women journalists reported experiencing highly sexualized social media attacks, including rape threats and sexist comments like “flat-chested” and “presstitute.” One interviewee said trolls manipulated her photo to put a penis in her mouth and captioned it “gangbang.” Another said her videos were spliced to make her look humiliated for asking officials controversial questions. These attacks were “meant to pound you to silence,” a female executive said. Participants blocked trolls, with some deactivating their accounts or unfriending family members for safety. A female reporter said:

I respond to messages pointing inaccuracy in an article. But if it’s just trolling for the sake of trolling, I ignore it. The first few times there was heavy bullying, I was really emotionally affected. I cried to my family. But now, you can choose to ignore it.

In the third strategy, journalists expressed solidarity with colleagues. When ABS-CBN was forced off the air, an Inquirer reporter said she and her officemates issued a statement. “We would also be attacked so we might as well express support for our comrades in arms.” Interviewees said they focused on community building and crowdfunding. Journalists also networked with civic groups. Some participants said international support such as grants for fora to fight disinformation, and the #HoldTheLine Coalition supporting legal funds and press freedom advocacy for Rappler were crucial to solidarity.

Closely linked to solidarity is the final strategy of advocating for press freedom. One-third of interviewees considered Duterte’s attacks an “existential crisis” and a “major blow” to press freedom, motivating them to condemn the assaults instead of merely quoting experts. Journalists hit the streets and brought the protest slogan online with the #DefendPressFreedom advocacy campaigns. An editor said Duterte’s actions changed his “detached” view:

I am no longer objective when it comes to press freedom. The media should take a side when their existence is at stake. “We are against the attacks on ABS-CBN, on Rappler.” It’s like they are about to stab you. Do you say, “Can I just interview you to ask why you are killing me?”

Role Perceptions

To justify their paradigm repair strategies, interviewees invoked role perceptions. Answering RQ2, three functions emerged as most relevant: the evolving watchdog, a heightened interpretive role, and a tighter link between the interpretive and disseminator roles.

Evolving Watchdog

Interviewees cited holding power accountable as their most significant role but said Duterte’s attacks made it more urgent. An editor said that while journalists previously focused on corruption, they now have to guard against Duterte’s media attacks. Participants also perceived Duterte’s populism as “eroding” and “coopting” institutions like the judiciary and congress. “The media is the only institution left to criticize the president,” a reporter said. While the fourth estate function became more important, attacks also made it more “taxing.” One reporter said that officials used to view journalists as independent critics “but now they see the media as an enemy.” The watchdog role, therefore, explains the strategy of reinforcing and adapting reporting practices to fulfill the changing demands of checking power in the face of a populist’s threats.

This shifting role also pertains to orientation: two-thirds of interviewees identified as detached watchdogs upholding neutrality while others turned to becoming interventionist watchdogs overtly confronting power. A senior reporter covering threats against his company said he refrained from joining protests to avoid accusations of bias. In contrast, some journalists said that Duterte’s media assaults forced them to become press freedom advocates and truth activists. A reporter called this a “moral dilemma”:

If our colleagues are losing their jobs because their newsrooms were shut because they were pronounced as biased, aren’t we going to act? Should we separate our role as activists for the truth versus our journalism? Is that even possible when journalism is all about the truth?

Heightened Interpretive Role, Link With Disseminator

Duterte’s attacks also strengthened interviewees’ view of their role of providing analysis alongside relaying information. Participants simultaneously mentioned the interpretive and disseminator roles. Journalists said that they could no longer merely convey information but needed “to distill the truth.” A reporter explained, “My role is to inform the public especially in the age of fake news, propaganda, disinformation. My role is to make sense of all the noise, to provide context.” To many interviewees, reporting and analysis became increasingly inseparable. The heightened interpretive role and its coupling with the disseminator role, therefore, link with strategies of reinforcing and adapting reporting routines, and improving transparency.

Collectively, interviewees saw their watchdog, interpretive and disseminator roles as means to help citizens make sound decisions, debunking Duterte’s “bad elites” accusation. A reporter said, “Our owners come from the elite but as cliché as it sounds, we are in the service of the Filipino.”

Challenges

Interviewees nonetheless faced challenges in enacting their strategies and ideals. Answering RQ2, these obstacles were self-censorship, declining public trust and rising polarization (see Appendix A in supplementary online).

Most interviewees from ABS-CBN and Inquirer said Duterte’s strategy of attacking media owners’ businesses triggered a domino effect of self-censorship. News officers said political pressure led to owners’ requests to tone down critical reports and offer false equivalence. Reporters refrained from hard-hitting analyses out of concern for job security, colleagues, and their company. A reporter described the impact:

It’s become a fight for survival. Isn’t a chilling effect only about thinking twice? Here, it’s outright fear already. You end up censuring yourself.

Improving reporting and transparency also faced limitations with a perceived loss of trust in journalists and polarization. Despite their audience engagement efforts, many participants said Duterte supporters were convinced that they were “fake news,” instead trusting mis- and disinformation sources. During the pandemic, a reporter said the impact went beyond journalism. “People simply do not believe any more information we put out there even if it is fact, backed up by science. This is dangerous because it spells the difference between life and death.” Some interviewees said the damage Duterte’s attacks inflicted on media credibility was so severe that “it will take years or a generation before we undo this.” Public distrust and polarization then hindered performing the interpretive and disseminator roles.

Discussion and Conclusion

The rise of anti-media populism in recent years has begged the vexing question of how journalists could defend their authority from radical populist politicians and citizens expressing hostile views. Responding to the call for research on anti-media populism in the Global South (Bhat and Chadha Citation2020), this study interviewed 18 Filipino journalists to understand how they repair the journalistic paradigm and perceive their roles in the context of attacks from a leader known for violent populism. Journalists from three outlets facing the brunt of Duterte’s threats pushed back by reinforcing and adapting reporting routines, improving and negotiating transparency, expressing solidarity, and campaigning for press freedom. Viewing strategies as tools to fulfill normative functions, journalists deemed their watchdog, interpretive and disseminator roles more urgent in light of populist demonization.

This study extends content analytical research applying paradigm repair to an external, understudied threat to the journalistic institution: anti-media populism (Whipple and Shermak Citation2020). Our results suggest that studies on journalistic responses to legitimacy threats may conceptualize paradigm repair strategies as a spectrum – moving from traditional practices to include unconventional methods against modern challenges like populist hostility. The commonplace and unorthodox strategies validate that paradigm repair and paradigm reconsideration (Vos and Moore Citation2020) aptly capture responses to outside threats. Linked with and attributed to role perceptions, the four strategies provide a baseline for empirical research to test such defensive tactics in contexts where journalists face similar constraints, particularly “insecure democracies” with high media violence (Hughes et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, findings bolster the importance of studying journalists’ views on populism (Stanyer et al. Citation2019), revealing not just problems but also solutions to delegitimizing attacks.

On one end of the paradigm repair spectrum, some Filipino journalists invoked objectivity as the news paradigm’s cornerstone in a customary approach to mend breaches in authority (Cecil Citation2002). This strategy aligns with the professionalism that German and American journalists employed against Lügenpresse and Trump’s attacks (Koliska and Assmann Citation2019; Lawrence and Moon Citation2021). This finding affirms literature on Filipino journalists’ adherence to objectivity (Tandoc Citation2016), consistent with colleagues’ previous appeals to the profession’s values when addressing internal lapses (Berkowitz Citation2000).

Yet, newer strategies indicate that contemporary crises like anti-media populism could push journalists along the other end of the spectrum to devise out-of-the-box responses. Abandoning false equivalence for live factchecks and context exemplifies paradigm reconsideration (Vos and Moore Citation2020) to avoid relaying divisive populist rhetoric. This is an encouraging finding as it shows that journalists even under severe pressure are able to critically challenge assumptions and adapt to shifting contexts. Transparency and debunking misinformation answer scholars’ call for journalists to ethically cover populism to help citizens be free and self-governing (Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2014). Similarly, solidarity with competitors illustrate that paradigm repair binds journalists during crises (Berkowitz Citation2000). As results underscore anti-media populism as a collective challenge to the journalistic community, one practical recommendation is for global press freedom and media development organizations’ campaigns to go beyond focusing on individual outlets like Rappler and provide industry-wide support such as a legal fund for more precarious, under-resourced local journalists.

This study’s primary theoretical contribution is interweaving paradigm repair with role perceptions providing a raison d’être to journalistic strategies whereas previous studies have mostly analyzed these concepts in isolation (e.g., Cecil Citation2002; Weaver et al. Citation2007). Findings illustrate that role perceptions are the why justifying paradigm repair strategies, while strategies are the how operationalizing ideals. Role perceptions are after all rooted in journalists’ values and norms (Hanitzsch Citation2011), impacting on their work. However, results reveal that beyond just shaping the content they produce (Hellmueller and Mellado Citation2015), role perceptions as markers of journalistic identity inform and substantiate journalists’ defensive maneuvers against institutional threats. Facing an existential crisis, journalists return to their professional purpose to determine their mode of defense. In turn, paradigm repair strategies are techniques journalists use to uphold their roles in response to intimidation. Mutually reinforcing, paradigm repair and role perceptions are both legitimacy sources that journalists wield against anti-media populism. This study then advances literature by exemplifying the usefulness of relating role perceptions with the spectrum of paradigm repair strategies. Future studies can apply this integrated framework to journalistic responses to present threats like audience fragmentation and polarization, epistemic relativism (Van Aelst et al. Citation2017), and more citizen-driven forms of “mob censorship” (Waisbord Citation2020).

Results also suggest that roles converge and shift in response to populist disinformation, extending research emphasizing role perceptions’ plurality and sensitivity to contexts (Márquez-Ramírez et al. Citation2020). Some participants’ identification as detached-turned-interventionist watchdogs depicts that roles are fluid and often fused (Weaver et al. Citation2007). In a country where journalists contend with threats on the rhetorical, legal and digital fronts in an already critical press freedom situation, anti-media populism emerges as a contextual factor that could lead journalists to assume a more adversarial role. In this vein, case studies and comparative research can establish whether this is a trend in and across countries led by anti-media populists.

While the study identified journalists’ counteroffensives, the barriers it outlined accentuate caveats against assuming that role conceptions always translate to practice (Hellmueller and Mellado Citation2015). For ABS-CBN and Inquirer journalists, owners’ business interests as organizational influences (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014) constrained performing their watchdog and interpretive roles while Rappler journalists had more agency due to the outlet’s diversified business model. This finding lends empirical support to commentary that Filipino journalists are vulnerable to owners’ editorial intervention due to government pressure (Coronel Citation2020). In media systems dominated by corporate elites, ownership is a vulnerability populists can exploit to weaken accountability journalism. Similarly, the chilling effect causing a lack of industry solidarity exhibits repercussions of Duterte’s divide-and-rule media strategy (Tapsell Citation2021). Implications here are twofold. For research, studies can examine the impact of populists’ friend-foe binaries and pressure on owners to thwart media in similar contexts. For practice, findings emphasize the need for independent, alternative business models, and media development initiatives fostering collaborations like grants for joint investigative reporting.

Overall, journalists’ negative perceptions of Duterte’s attacks ground the hypothesis that populism in government in unconsolidated democracies has detrimental consequences (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2012). For professionals forming a vital democratic pillar, populism in the highest post eroded frail institutions. Participants regarding populism as curtailing press freedom and contravening checks and balances matches European journalists’ view that populism undermines democracy (Stanyer et al. Citation2019). The difference is that moderators like the assaults’ intensity, Duterte’s violent populism, and vicious trolling to silence specifically women journalists arguably led to more adverse impacts in the Philippines, upholding findings on online harassment in other developing countries (Jamil and Sohal Citation2021). Despite seeming similarities, populism then needs to be grounded in socio-political contexts.

Results must be interpreted in light of limitations. First, the qualitative interviews did not determine strategies and roles’ salience in a first attempt to understand journalists’ perceptions. Survey research can fill this gap. Second, strategies’ effectiveness in regaining audience trust is unknown, leaving their usefulness in restoring credibility an open question. Experiments could distinguish which strategies convince which audiences. Third, the study focused on mainstream national journalists but provincial and alternative news practitioners may have different strategies for future research to unpack. Fourth, the study excluded social media analysis. Examining posts would be valuable because journalists may have more space for expression online given company self-censorship. Content and network analysis of anti-press social media messages would point to further interventions. Findings also beg the question of the adequacy of blocking and ignoring trolls for female journalists to cope with relentless online harassment. Therefore, research identifying strategies to combat gendered trolling is critical.

Transferability of findings is another limitation opening up research avenues. Street and legal activism may not apply to other settings given the Philippines’ unique media system and Duterte’s violent populism. Researchers could explore whether journalists in other Global South democracies employ similar strategies. Some roles and strategies may differ in Western Europe with its public service media tradition and well-developed institutions. Yet responses like invoking journalism’s accountability role cut across settings due to paradigm repair’s assertion of journalists’ common professional identity (Vos and Moore Citation2020). Comparative research testing assumptions of populism’s strength vis-à-vis democratic consolidation and populists being in power or opposition would contribute to the populism-democracy debate. Finally, future studies can further analyze the link between paradigm repair and role perceptions. What configurations of strategies and roles are plausible? In what contexts and challenges do these emerge? How do journalists mix and match these depending on the need?

Despite these shortcomings, this study contributes to both journalistic research and practice by informing the global discussion on responses to attacks from populist politicians, and best practices of reporting populist communication. The strategies and roles detailed here can form building blocks for a journalistic toolkit of re-legitimizing counterstrategies to the anti-media populist playbook often cited in literature. This research demonstrated the democratic relevance of going beyond typologies of populists’ tactics to whack the watchdogs but also learning how the watchdogs bite back with their clarion call to #DefendPressFreedom.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (128.2 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Balod, H. S. S., and M. Hameleers. 2019. “Fighting for Truth? The Role Perceptions of Filipino Journalists in an Era of Mis- and Disinformation.” Journalism, 1–18. doi:10.1177/1464884919865109.

- Beiler, M., and J. Kiesler. 2018. “Lügenpresse! Lying Press! Is the Press Lying?” In Trust in Media and Journalism: Empirical Perspectives on Ethics, Norms, Impacts and Populism in Europe, edited by K. Otto, and A. Köhler, 155–179. Wiesbaden: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-20765-6_9

- Beiser, E. 2020, October 28. Getting Away With Murder. Committee to Protect Journalists. https://cpj.org/reports/2020/10/global-impunity-index-journalist-murders/.

- Berkowitz, D. 2000. “Doing Double Duty: Paradigm Repair and the Princess Diana What-a-Story.” Journalism 1 (2): 125–143. doi:10.1177/146488490000100203.

- Bhat, P., and K. Chadha. 2020. “Anti-Media Populism: Expressions of Media Distrust by Right-Wing Media in India.” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 13 (2): 166–182. doi:10.1080/17513057.2020.1739320.

- Borden, S. L., and C. Tew. 2007. “The Role of Journalist and the Performance of Journalism: Ethical Lessons from “Fake” News (Seriously).” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 22 (4): 300–314. doi:10.1080/08900520701583586.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bulut, E., and E. Yörük. 2017. “Digital Populism: Trolls and Political Polarization of Twitter in Turkey.” International Journal of Communication 11 (25): 4093–4117. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6702/2158.

- Cecil, M. 2002. “Bad Apples: Paradigm Overhaul and the CNN/Time “Tailwind” Story.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 26 (1): 46–58. doi:10.1177/019685990202600104.

- Chua, Y. 2020. Philippines. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/philippines-2020/.

- Coronel, S. 2020. “Press Freedom in the Philippines.” In Press Freedom in Contemporary Asia, edited by T. Burrett, and J. Kingston, 214–229. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429505690

- Cottle, S., R. Sambrook, and N. Mosdell. 2016. Reporting Dangerously: Journalist Killings, Intimidation and Security. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-1-137-40670-5

- Egelhofer, J. L., L. Aaldering, and S. Lecheler. 2021. “Delegitimizing the Media? Analyzing Politicians’ Media Criticism on Social Media.” Journal of Language and Politics 20 (5): 653–675. doi:10.1075/jlp.20081.ege.

- Egelhofer, J. L., and S. Lecheler. 2019. “Fake News as a Two-Dimensional Phenomenon: A Framework and Research Agenda.” Annals of the International Communication Association 43 (2): 97–116. doi:10.1080/23808985.2019.1602782.

- Farhall, K., A. Carson, S. Wright, A. Gibbons, and W. Lukamto. 2019. “Political Elites’ Use of Fake News Discourse Across Communications Platforms.” International Journal of Communication 13 (23): 4353–4375. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10677.

- Fawzi, N. 2019. “Untrustworthy News and the Media as Enemy of the People?: How a Populist Worldview Shapes Recipients’ Attitudes Toward the Media.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (2): 146–164. doi:10.1177/1940161218811981.

- Fawzi, N. 2020. “Right-Wing Populist Media Criticism.” In Perspectives on Populism and the Media: Avenues for Research, edited by B. Krämer, and C. Holtz-Bacha, 39–56. Nomos. doi:10.5771/9783845297392

- Freedom House. 2018. Attacks on the Record. https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2018/attacks-record.

- Gelfert, A. 2018. “Fake News: A Definition.” Informal Logic 38 (1): 84–117. doi:10.22329/il.v38i1.5068.

- Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co.

- Hameleers, M. 2020. “My Reality is More Truthful Than Yours: Radical Right-Wing Politicians’ and Citizens’ Construction of “Fake” and “Truthfulness” on Social Media – Evidence from the United States and The Netherlands.” International Journal of Communication 14 (18): 1135–1152. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/12463.

- Hameleers, M., A. Brosius, F. Marquart, A. C. Goldberg, E. van Elsas, and C. H. de Vreese. 2021. “Mistake or Manipulation? Conceptualizing Perceived Mis- and Disinformation Among News Consumers in 10 European Countries.” Communication Research, 1–23. doi:10.1177/0093650221997719.

- Hanitzsch, T. 2011. “Populist Disseminators, Detached Watchdogs, Critical Change Agents and Opportunist Facilitators: Professional Milieus, the Journalistic Field and Autonomy in 18 Countries.” International Communication Gazette 73 (6): 477–494. doi:10.1177/1748048511412279.

- Hellmueller, L., and C. Mellado. 2015. “Professional Roles and News Construction: A Media Sociology Conceptualization of Journalists’ Role Conception and Performance.” Communication & Society 28 (3): 1–11. doi:10.15581/003.28.3.1-11.

- Horbyk, R., I. Löfgren, Y. Prymachenko, and C. Soriano. 2021. “Fake News as Meta-Mimesis: Imitative Genres and Storytelling in the Philippines, Brazil, Russia and Ukraine.” The Journal of the Aesthetics of Kitsch, Camp and Mass Culture 5 (1): 30–54. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:aalto-2021112410434.

- Hughes, S., C. Mellado, J. Arroyave, J. L. Benitez, A. de Beer, M. Garcés, K. Lang, and M. Márquez-Ramírez. 2017. “Expanding Influences Research to Insecure Democracies.” Journalism Studies 18 (5): 645–665. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2016.1266278.

- International Criminal Court. 2021, September 15. Situation in the Philippines: ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I Authorises the Opening of an Investigation. https://www.icc-cpi.int/Pages/item.aspx?name=PR1610.

- Jagers, J., and S. Walgrave. 2007. “Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium.” European Journal of Political Research 46 (3): 319–345. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x.

- Jamil, S., and P. Sohal. 2021. “Reporting Under Fear and Threats: The Deadly Cost of Being a Journalist in Pakistan and India.” Journal of Russian Media and Journalism Studies 1 (2): 5–33. http://worldofmedia.ru/volumes/2021/2021_Issue_2/.

- Koliska, M., and K. Assmann. 2019. “Lügenpresse: The Lying Press and German Journalists’ Responses to a Stigma.” Journalism, 1–18. doi:10.1177/1464884919894088.

- Kovach, B., and T. Rosenstiel. 2014. The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. New York: Three Rivers Press.

- Krämer, B. 2018. “Populism, Media, and the Form of Society.” Communication Theory 28 (4): 444–465. doi:10.1093/ct/qty017.

- Krämer, B., and K. Langmann. 2020. “Professionalism as a Response to Right-Wing Populism? An Analysis of a Metajournalistic Discourse.” International Journal of Communication 14 (23): 5643–5662. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/14146.

- Lawrence, R. G., and Y. E. Moon. 2021. “We Aren’t Fake News: The Information Politics of the 2018 #FreePress Editorial Campaign.” Journalism Studies 22 (2): 155–173. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1831399.

- Márquez-Ramírez, M., C. Mellado, M. L. Humanes, A. Amado, D. Beck, S. Davydov, J. Mick, et al. 2020. “Detached or Interventionist? Comparing the Performance of Watchdog Journalism in Transitional, Advanced and Non-Democratic Countries.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (1): 53–75. doi:10.1177/1940161219872155.

- Mazzaro, K. 2021. “Anti-Media Discourse and Violence Against Journalists: Evidence From Chávez’s Venezuela.” The International Journal of Press/Politics, 1–24. doi:10.1177/19401612211047198.

- Mudde, C. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 541–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x.

- Mudde, C., and C. R. Kaltwasser. 2012. “Populism and (Liberal) Democracy: A Framework for Analysis.” In Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy?, edited by C. Mudde, and C. R. Kaltwasser, 1–26. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139152365.002

- Nobel Peace Prize. 2021, October 8. The Nobel Peace Prize 2021. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2021/press-release/.

- Ong, J. C., and J. V. A. Cabañes. 2018. “Architects of Networked Disinformation: Behind the Scenes of Troll Accounts and Fake News Production in the Philippines.” University of Massachusetts Amherst Communication Department Faculty Publication Series 74: 1–74. doi:10.7275/2cq4-5396.

- Panievsky, A. 2021. “The Strategic Bias: How Journalists Respond to Antimedia Populism.” The International Journal of Press/Politics, 1–19. doi:10.1177/19401612211022656.

- Posetti, J., S. Nabeelah, D. Maynard, K. Bontcheva, and N. Aboulez. 2021. The Chilling: Global Trends in Online Violence Against Women Journalists. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/publications/thechilling.

- RSF. n.d. Philippines. Accessed 26 March 2022. https://rsf.org/en/philippines.

- Shoemaker, P., and S. D. Reese. 2014. Mediating the Message in the 21st Century: A Media Sociology Perspective. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Smith, G. R. 2010. “Politicians and the News Media: How Elite Attacks Influence Perceptions of Media Bias.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (3): 319–343. doi:10.1177/1940161210367430.

- Stanyer, J., S. Salgado, G. Bobba, G. Hajzer, D. N. Hopmann, N. Hubé, N. Merkovity, et al. 2019. “Journalists’ Perceptions of Populism and the Media: A Cross-National Study Based on Semi-Structured Interviews.” In Communicating Populism: Comparing Actor Perceptions, Media Coverage, and Effects on Citizens in Europe, edited by C. Reinemann, J. Stanyer, T. Aalberg, F. Esser, and C. H. de Vreese, 235–252. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429402067

- Tandoc, E. C. J. 2016. “Journalists in the Philippines.” Worlds of Journalism Study. https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/30119/1/Country_report_Philippines.pdf.

- Tandoc, E. C. J., K. K. Sagun, and K. P. Alvarez. 2021. “The Digitization of Harassment: Women Journalists’ Experiences with Online Harassment in the Philippines.” Journalism Practice, 1–16. doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1981774.

- Tapsell, R. 2021. “Divide and Rule: Populist Crackdowns and Media Elites in the Philippines.” Journalism, 1–16. doi:10.1177/1464884921989466.

- Thompson, M. R. 2021. “Duterte’s Violent Populism: Mass Murder, Political Legitimacy and the “Death of Development” in the Philippines.” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 1–26. doi:doi:10.1080/00472336.2021.1910859.

- Van Aelst, P., J. Strömbäck, T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. de Vreese, J. Matthes, D. Hopmann, et al. 2017. “Political Communication in a High-Choice Media Environment: A Challenge for Democracy?” Annals of the International Communication Association 41 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551.

- Vera Files & RSF. 2016. Media Ownership Monitor Philippines. https://philippines.mom-rsf.org/fileadmin/rogmom/output/philippines.mom-rsf.org/philippines.mom-rsf.org-en.pdf.

- Vos, T. P., and J. Moore. 2020. “Building the Journalistic Paradigm: Beyond Paradigm Repair.” Journalism 21 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1177/1464884918767586.

- Waisbord, S. 2020. “Mob Censorship: Online Harassment of US Journalists in Times of Digital Hate and Populism.” Digital Journalism 8 (8): 1030–1046. doi:10.1080/21670811.2020.1818111.

- Waisbord, S., and A. Amado. 2017. “Populist Communication by Digital Means: Presidential Twitter in Latin America.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1330–1346. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328521.

- Weaver, D. H. 1977. “The Press and Government Restriction: A Cross-National Study Over Time.” Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) 23 (3): 152–169. doi:10.1177/001654927702300301.

- Weaver, D. H., R. A. Beam, B. J. Brownlee, P. S. Voakes, and G. C. Wilhoit. 2007. The American Journalist in the 21st Century: U.S. News People at the Dawn of a New Millennium. New York: Routledge.

- Whipple, K. N., and J. L. Shermak. 2020. “The Enemy of My Enemy is My Tweet: How #NotTheEnemy Twitter Discourse Defended the Journalistic Paradigm.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 97 (1): 188–210. doi:10.1177/1077699019851755.