Abstract

Objective: This study aims at exploring university students' attitudes towards the application of genomic science and technology (GST) and the rationales behind their judgments. Background: With the rapid advances in GST, its wide application will become common in the near future. Since understanding the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of GST is important for its sustained development, understanding public attitude towards GST application is critical for its acceptance in Hong Kong society. Participants: Cantonese speaking undergraduate and postgraduate students of the University of Hong Kong (HKU-students). Methods: The study consisted of two parts. Part 1 was a survey of 400 HKU-students recruited at the library entrance and the written questionnaires were completed immediately. Part 2 comprised semi-structured interviews of 65 of the 400 HKU-students surveyed in Part 1 and each was interviewed individually. Conclusions: In Part 1, HKU-students had “neutral” responses for most themes, and Part 2 showed that the “neutrality” was primarily caused by opposing opinions of proponents and opponents in each theme. HKU-students had a negative attitude towards human genetic enhancement and were worried about GM food, genetic discrimination, and misuses of genetic information. The study did not support “the deficit model” but confirmed the “particularistic” view that endorsement of a GST application is determined by specific contextual factors.

Introduction

As part of the Human Genome Project (HGP) (1990–2003), the study of the “ethical, legal, and social implications” (ELSI) was included as one of the research targets and a wide range of controversial issues concerning the applications of genomic science and technology were identified and subjected to public discussion (HGP Information 2008). For instance, it was recognized that prenatal diagnosis of genetic diseases followed by termination of pregnancy (TOP) would cause emotional distress to prospective parents (Marteau Citation1993) and doctors (Garel et al. Citation2002); the potential abuse of genetic data by insurance companies and employers to discriminate against those at risk of certain genetic diseases was also revealed (Ness et al. Citation2004). Moreover, genetic discrimination based on family history rather than genetic test results could also happen among family members, friends, and colleagues (Bombard et al. Citation2009). Another important ELSI theme was “informed consent” as related to the clinical uses of GST including prenatal diagnosis (Garel et al. Citation2002) and disclosure of genetic information (Benkendorf et al. Citation1997).

In many countries, large-scale national surveys, such as the EU Eurobarometer series, the UK Human Genetic Commission series and the US Genetics and Public Policy Center series, are regularly conducted. They are based on the conviction that the application of GST should play a role in informing its development (Williams et al. Citation2009). Sharing this view, we aim in the present study to explore the attitude of university students in Hong Kong about the use of GST. University students are chosen as the subjects because first, they are likely to become middle class and have reproductive needs a few years after they graduate, when GST such as prenatal genetic diagnosis, genetic therapy, and genetic enhancement will become popular in Hong Kong and affordable by them. Second, since university students are supposed to have a higher “genetic literacy” (Turney Citation1995), their responses will be more informed and grounded than those of the general public.

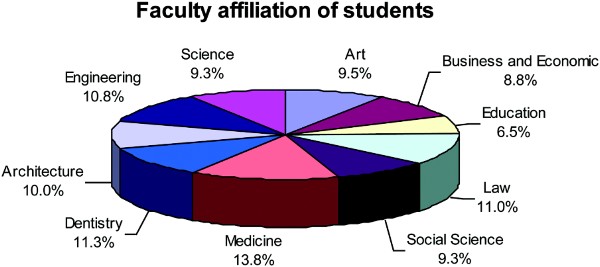

Within the ELSI discourse, there is a debate concerning whether people who are more knowledgeable about science will be more supportive of its development than those who are less knowledgeable. Advocates of “the deficit model” argue that people's conservative attitude towards science and technology is caused by their lack of scientific knowledge. However, others argue that in many cases having scientific knowledge is neither necessary nor sufficient for holding a positive attitude towards scientific development (Sturgis and Allum Citation2004, pp. 55–58, Sturgis et al. Citation2005). In the present study, the subjects, who come from 10 different faculties, are grouped into three streams: (1) Arts and Social Science, (2) Health Science and (3) Pure and Applied Science (). Health Science students are supposed to be most genetically literate whereas Arts and Social Science students the least. We examine whether the students' responses would support the deficit model.

Table 1. Streams and faculty affiliation of 400 HKU-students.

Sample and method

This study consisted of two parts. Part 1 was a questionnaire survey conducted at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) targeting as study subjects both undergraduate and postgraduate students from 10 faculties including Arts, Business and Economics, Education, Law, Social Sciences, Medicine, Dentistry, Architecture, Engineering and Science (hereafter “HKU-students”). Students were recruited on a one-to-one basis outside the university's main library and each was given a written questionnaire that was completed and returned immediately; willingness to participate implied consent. Apart from exploring the students' preferences, we also sought to understand the reasons for those preferences. Therefore, we invited the students to participate in Part 2 of the study, which consisted of one-to-one interviews of about 30 minutes each. Of the 400 students who participated in the survey, 99 students accepted the invitation and 65 interviews (33 males and 32 females, aged between 19 and 24) were conducted successfully from December 2006 to June 2007. Planned, open-ended questions corresponding to the statements in the survey questionnaire were asked. All interviews were conducted in Cantonese, recorded by audiotapes with consent, and then transcribed verbatim by the interviewers. The first 15 interviews also served as pilot studies to gain new ideas on the phrasing of questions, improving the interview guide, developing supporting materials, such as tree diagrams of family members, and facilitating the implementation of subsequent interviews. Transcripts were coded and analyzed using the grounded theory by two trained technicians independently. Keywords or phrases were highlighted line by line. Segments of transcripts were extracted and grouped according to their emergent pattern. A motif was then assigned to each group. Similar or repetitive motifs were condensed or arranged into hierarchical structures, so that one main common motif code could be induced (Charmaz Citation2006). The codes then underwent meticulous comparisons until the two coders reached 100% agreement. The transcripts were then translated into English by one of the technicians. The coded transcripts were analyzed and integrated for presentation. All data collected in Parts 1 and 2 were treated as confidential and anonymous. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster.

Results

In Part 1, 400 “HKU-students,” 49.5% male (n = 198) and 50.5% female (n = 202), were successfully recruited, with 86.8% students being undergraduates and 13.2% postgraduates. Overall, the number of students recruited was fairly evenly distributed among the 10 faculties (see Appendix). shows the students' demographic characteristics; significant differences were noted for students' gender, age, and religion across the three “streams” of students. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize all students' responses in the questionnaire; mean scores of each theme were given from 1 to 5 based on the five-point Likert scale with 1 being “strongly disagree” and 5 being “strongly agree,” and “neutral” set at 3 (). Factor analysis, derived by principal component factor analysis with varimax rotation, was applied to the 24 questions in the questionnaire. Manual adjustment was further made to improve the integrity of subject content of each theme. Five independent themes were identified from 17 questions. They included: (A) Use of GST to prevent disease; (B) GST and negative reproductive implications; (C) Genetic modification of food and other organisms; (D) Human genetic enhancement; (E) Abusive uses of genetic information. The remaining seven questions were treated as independent items. Contents of themes and their related questions and their corresponding Cronbach's alpha are given in .

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of HKU-students who participated in survey.

Table 3. Contents of themes, their related questions and corresponding Cronbach's alpha values, and mean scores of “HKU-students” (n = 400).

Theme A (Use of GST to prevent disease)

HKU-students responded to this theme with “high-neutral” score (mean = 3.22, ), ranging between 2.90 for the use of GST to stop children from inheriting non-fatal birth defects (Q5) and 3.68 to reduce the number of disabled children born (Q3). To explore possible reasons behind the statistical data, students were asked to comment on using prenatal genetic diagnosis (PND) to identify genetic disorders including Thalassemia anemia, Down syndrome (DS) and cleft lip, followed by termination of pregnancy (TOP). Proponents defended their affirmation mainly along utilitarian grounds: “If the disease is really serious, abortion prevents the birth and one fewer life is suffering. I will agree with it.” “Abortion seems to be cruel …, otherwise, the child will add burdens to the society and the medical system, and greatly increase the parents' psychological stress.” Proponents also opined that PND followed by TOP would be a better option than abandoning a defective baby after birth; using GST to identify and prevent disease could provide data for medical research.

On the other hand, opponents relied on the “deontological” premise that “abortion is like murdering” and to reject PND-TOP is “basically about respecting lives.” Besides, “no one has the right to decide life or death” and to choose abortion is to act as “a substitute of God or Nature. It is … a confusion of power.” Furthermore, “if PND-TOP is really put into use [on a large scale] because people want to have better kids, eugenics will happen ….” These opponents also argued that accuracy was not guaranteed in PND and this might lead to unnecessary abortion and some forms of PND were invasive, e.g. amniocentesis that might lead to miscarriages.

Quite a few students were “conditional approvers” for whom the severity of genetic condition is an important consideration for endorsing PND-TOP: “If it is Thalassemia anemia, it is severe … it's better not to give birth. For cleft lip, it is no big problem. So, it depends on the situation.” Actually, only two students approved of PND-TOP for cleft lip. Compared to Thalassemia and cleft lip, Down syndrome (DS) was the most controversial: “I think Down's syndrome is not really a severe disease, and even if someone is born with it, she can still have a very happy life. We should not terminate a pregnancy just because the child may have some cognitive problems.” Particularly, during the pregnancy, “one does not really know how serious [the DS] will be, and if you just abort at wish, you deprive the child's right to live.” A few students were willing to endorse PND-TOP as long as PND would not be compulsory and performed with safety precautions.

In terms of using GST to identify genetic predisposition to chronic diseases such as breast cancer, heart disease and dementia, some interviewees believed that “… when the person knows that she has the gene, and though nothing can be changed, the person can … see if there are other ways to prevent or treat the disease.” Others disagreed because having disease-predisposing genes is not equivalent to having the disease and GST may cause unnecessary anxiety and grief: “I think there is no need to do [the test] because one can't be sure that the disease will definitely develop in the future.” Based on these testimonies, it seems that the “neutral” score in the survey is likely because HKU-students held divergent views rather than an attitude of indifference regarding the use of GST to detect diseases and to abort affected fetuses.

Theme B (GST and negative reproductive implications)

The mean score for this theme was 3.60 (), indicating a general agreement among HKU-students that GST has negative reproductive implications. The responses to this theme were gender-sensitive, with male students having stronger agreement than female students (mean = 3.67 and 3.53 respectively, p = 0.036, ). Specifically, students believed that pregnant women often consented to genetic testing and to TOP without being fully informed (mean = 3.69 for both, ). In the interviews, students were asked if they would reconsider their endorsement of using GST in light of the negative implications including post-PND miscarriages and unnecessary and unjustified PND-TOP. Some students changed their views because “I didn't know that […] PND would increase the chance of miscarriages, I will not agree [with PND] in that case.” “One [miscarriage] in 200 [amniocentesis] is a rather big [number] … I have reservations [about it]” and this “goes against the original purpose of [removing] disabilities.” Nevertheless, a few remained convinced that GST brought more benefit than harm, and some felt that unnecessary abortions and other negative consequences could be avoided if the institution and doctors were more careful.

Table 4. The effects of demographic variables on survey results of HKU-students.

Theme C (Genetic modification of food and other organisms)

HKU-students' mean response for this theme was a lower neutral score of 2.82 () with female students having stronger disagreement than male (mean = 2.69 and 2.95 respectively, p = 0.001, ). In the interviews, proponents of GM food argued that “GM improves food quality,” “helps third world countries to produce more food” and “increases the productivity of poor countries.” But opponents of GM food disagreed because “I read in [a] newspaper that fish genes are added into [GM] tomatoes, but for vegetarians, this is the same as killing [fish], and this is not fair to them.” Also, “GM of living things must have [negative] influence on the natural ecosystem …” and it is an act “against the order of nature.” As for the question why GM plants seem to be more acceptable than GM animals (), those who agreed believed that animals are in a higher order of being than plants as “animals seem to have spirituality” or that “animals are more complicated and genetic modification of animals may carry higher risks.” Those who disagreed believed that “both plants and animals are natural lives” and so one cannot say that “it's okay to modify plants but not okay to modify animals.”

Theme D (Human genetic enhancement (HGE))

The mean response for this theme was 2.11 () indicating that HKU-students strongly disagreed with HGE, and female students had stronger disagreement than male students (2.03 and 2.20 respectively, p = 0.044, ). In the personal interviews, only a handful of interviewees supported HGE with reasons including “HGE can prepare individuals for competition in society” or “it is human nature to prefer more superior qualities” and “HGE may improve people's health and life.” Opponents to HGE provided several strong counter-arguments. First, HGE is a misuse of technology because GST is intended “to improve health but not non-health related human [qualities], and HGE has gone beyond this presumption.” Secondly, “… if HGE becomes widely used, some people who are not [enhanced] may be discriminated and this is unfair.” Thirdly, there is a concern about the loss of individual uniqueness since “… if you modify [genes] to improve [human qualities], then everyone demands the best, then actually everyone becomes the same …” Also, HGE potentially may increase the rich–poor gap since “… only the rich can afford HGE, and the rich children will become smarter, [and] the rich will end up richer, and the poor poorer …” HGE also violates a child's individuality because “an individual is a person …, not a machine that you can do whatever you want … we should not treat [a person] like a robot” and “God … has created everyone to be unique, and we should appreciate these differences instead of making everyone similarly perfect.” Finally, HGE is risky, because “human beings may not be able to control HGE, and there can be severe negative consequences, unknown consequences.”

Theme E (Abusive use of genetic information)

In the survey, HKU-students' overall response was a mild positive mean of 3.26 (), with students agreeing that genetic discrimination would most likely occur in insurance applications (mean = 3.72), less likely in employment (mean = 3.38) and least likely in schools (mean = 2.94). With regard to the possibility of unauthorized access to genetic information (GI) by third parties, the participants held a middle-ground attitude (mean = 3.02).

In the interviews, most HKU-students agreed that unfavorable genetic information (GI) might jeopardize one's insurance applications because “when you purchase insurance … insurance companies will calculate [the premium] according to your risks. If [you are] in the high risk group … they will either charge you a higher premium, or simply reject your application. Similarly, if your genetic test indicates that you have a high risk of breast cancer, they will either charge you more, or reject you. I think this will happen.” A few opined that the exclusion was justified because “if you have disabilities, insurance companies reserve the right not to insure you.” On the other hand, some held that the exclusion policy is unjustified because GI is “part of one's most important personal privacy” and should be protected from access by third parties like insurance companies.

For genetic discrimination in the workplace, some HKU-students thought that it is reasonable for employers to do that because “employers have strong desires to recruit excellent employees … those at the top,” and “if employers know that … the employee may only have several years to live … it's a waste of money to train her … and they won't do it.” Some students believed that employers should not have access to employees' GI in the first place due to the Data Protection Act and Privacy Ordinance of Hong Kong.

Regarding genetic discrimination in school admission, only a few believed that this will happen because of the keen competition between schools in Hong Kong and “schools will selectively pick students with … good genes.” Contrarily, many believed that genetic discrimination in school admission would not happen either because “schools are unlikely to obtain [genetic] information,” or “schools are regulated by the Government … [that] encourages equality.” Still others believed that discrimination should not happen because “genetic information is just a prediction, not that [the child] really has the disease” or if the child actually has a genetic condition, then the school “should devote more time and effort to the child rather than discriminate against the child.”

Students were also quite evenly divided when asked whether GI stored in databanks would be accessed by third parties without the owner's permission (Q22: mean = 3.02, ). Some believed that the data would be accessed by the police or other government agencies secretly for investigative purposes. Others were more confident that this would not happen because of sound existing laws and protective policies. Students also suggested several approaches to protect and store GI: (1) legislation; (2) GI only for research purposes; (3) tighten informed consent requirements; (4) increase public awareness about the social implications of GI; (5) store GI in public or academic institutions such as hospitals, government departments, or universities; and (6) store GI in computers with security devices and managed by special staff.

Theme F (Health and diseases are determined by genes)

HKU-students had a neutral response for this theme (mean = 2.98, ) and the majority of interviewees held that genes only contributed partly to health and disease: “… apart from genes the living environment, personal conduct, diet, or exercise are … influential on personal health and diseases.”

Theme G (GST reduces personal responsibility for health)

HKU-students responded negatively to the theme (mean = 2.35, ). The dominant view was that since GST “has not completely explained how illnesses are related to genes,” it is “premature and unhelpful to blame everything on genes” and because “the body is one's own, to care for it is one's responsibility.” A minority view held that “… people will be less responsible for personal health because they think our medical technology has advanced [to the point that] many diseases can be treated, and people don't care about resting, health or sleeping …” Also, since “many Chinese people think that many things are passed on from previous generations, they will blame [their poor health] on the inheritance [of ‘bad’ genes].”

Theme I (Family members are obliged to share GI with each other)

HKU-students had a neutral response to this theme (mean = 3.02) and the interviews revealed that their opinions were diverse. Family kinship was the most important factor that positively influenced the willingness to share GI, especially with first degree relatives, such as parents, siblings, and children: “My children were born with half of my genes … If I have a [genetic] problem, my children will … have a chance to get my defective genes.” As the “blood tie” gets weaker, sharing GI becomes more hesitant: “I think I will share GI with my siblings, but for cousins I need to consider …”; “the cousins I know very well, I don't mind telling.” The first reason for being more cautious is “because [kinship] comes in different degrees … and if I share my GI with them, it may be disseminated in a rapid and uncontrollable manner that I don't want to see.” Secondly, “if everyone knows that I have a genetic problem, it will affect my relationship with them and they may discriminate against me.” In contrast, many students were indifferent to kinship obligations and defended their reluctance to share personal GI because “GI is my very private information, and I would … not be so willing to share it with others.” Furthermore, “because my parents are old … I don't want them to worry about me. So I won't tell them.” “Besides they don't even know what a gene is.” A few were willing to disclose personal GI “if the disease is severe; but I will hide the less severe ones …”

Theme K (Genomic science ultimately tampers with nature)

HKU-students had a positive response for this theme (mean = 3.89) and most interviewees agreed that GST is tampering with nature mainly because it disturbs “the balance of the ecosystem … which is the result of innumerable years' effort by nature, and GST is changing this equilibrium.” “For example, modifying plant genes to make it more productive is not a ‘natural operation’ … Other things will be affected and there will be a chain reaction.” “The gene database of nature will be interfered with.” Students with a more religious bent simply summarized their attitude: “… Like what Catholics say, everything is produced by God. But if you attempt to change it deliberately, you are destroying … nature.” A minority few expressed that “lots of things tamper with nature, but it does not mean that they should not be done” and “if there is enough regulation, it may not matter much.”

The relation between knowledge and attitude regarding GST

We grouped the students into three streams based on their genetic literacy. Among them, students in the Health Science “stream” were expected to have higher genetic literacy while Pure/Applied Science students were expected to be more knowledgeable in science subjects. However, there was no statistically significant difference among the three “streams” of students in their attitudes towards GST except in Theme C regarding genetic modification of food and other organisms.

In Theme C, there was a significant difference between Arts/Social Science students and Health Science students (2.68 v 3.02, ). If religion produces a conservative and hence negative attitude towards GM food production, one would expect Health Science students to be less supportive of Theme C than Arts/Social Science students since the former had more students with religious beliefs than the latter (48.5% vs. 37.8% ), but our result was the opposite. Plausibly, the difference can be explained by gender since female students were less supportive than male students for this theme (2.69 vs. 2.95, p = 0.001, ), and there were more female students in Arts/Social Science than in Health Science (63.9% vs. 48%, ). But if gender were very decisive, one would expect to see a difference between Arts/Social Science students and Pure/Applied Science students which had the lowest number of female students (32.5%, ). Such a difference was not seen (2.68 vs. 2.87, ).

Table 5. Comparison of the mean scores of the three “streams” of students toward genomic science and technologies (GST).

Perhaps Health Science students were more knowledgeable about and supportive of GM food. They showed more optimism and less concern about the risks of GM food: “I agree with GM food. I found it agreeable after considering the benefits and risks.” “GM food can be introduced to poor countries to increase food production. So I think this is a good thing.” In contrast, the testimonies of Arts/Social Science students displayed a stronger sense of uncertainty and ambivalence as represented by the following students' remarks: “It's difficult to say … GST is a very new and advanced technology. The harm it may bring to us is not foreseeable … So I have a reserved attitude. I think there should be more research in this direction.” Another student concurred: “This topic is huge … and it involves humans … and research is not enough. If we break it down into smaller topics, say like, how to use it, on what diseases, which kind of food it can be applied to and which it cannot, then it's easier to discuss. But as a big topic, there is still not enough research.” It should be added that there were five subjects holding a neutral attitude towards GM food production and none of them were Health Science students. In sum, our study indicates that, in general, knowledge in science and genetic literacy does not appear to have significant impacts on attitudes towards the use of GST except the consumption of GM food. In the latter case, we incline to believe that Health Science students have a more positive view towards non-human genetic enhancement probably because they have more knowledge on the subject.

Discussion

The questionnaire survey of 400 HKU-students in Part 1 of this study yielded largely ambivalent results, with neutral scores (mean = 2.5 to 3.5) found in seven out of 12 themes (A, C, E, F, I, J, and L). The interviews in Part 2 of the present study confirmed that the neutral responses were due to divergence in opinion among students, rather than ambivalence because of inadequate understanding of GST. Since GST is a new and emerging technology that offers both advantages and disadvantages, it naturally invokes ambivalent responses that reflect either individuals struggling to balance the pros and cons of GST, or groups of individuals holding opposing views about GST. Either way, it produces ambivalent responses in quantitative surveys, and it is only in qualitative interviews that the coexistence of approvals and disapprovals, acceptance and rejection of GST are revealed (Furu et al. Citation1993, Jallinoja et al. Citation1998).

GST, disease prevention and abortion (Themes A, B, F, and G)

To use GST to prevent diseases is a controversial subject on which HKU-students responded with ambivalence, and a major reason is due to the so-called “diagnostic–therapeutic gap” commonly seen in medical applications of GST. For example, prenatal diagnosis is an excellent tool for the early detection and prognostication of many hereditary and congenital diseases, yet until fetal surgery and gene therapy become routine medical services, the only available treatment for most prenatally diagnosed conditions is abortion. Our study showed that while most interviewed students were agreeable to identifying fetal anomalies, they were divided about abortion as the means to eliminate the identified “problem.” Some students applied the “utilitarian calculus” and reluctantly agreed with aborting an affected fetus where harms and burdens outweigh benefits, while others rejected abortion for religious, humanitarian, and eugenic reasons. The positions held by these two camps of students were not easily reconcilable. These findings are consistent with an earlier study in Hong Kong that only half or less than half of women attending a prenatal diagnosis counseling clinic agreed that a woman should have the right to an abortion in early (52.5%) and mid-trimester (41.0%) gestation (Leung et al. 2004).

Another reason that may explain the ambivalence in this theme is the lack of universal standards that will guide the use of GST such as PND-TOP. Many students took the conditional position that GST would be acceptable if it could diagnose and prevent serious genetic conditions. But there are potentially thousands of diseases associated with different degrees of genetic abnormalities, and in the present study, HKU-students were unable to agree which of the following three conditions: Thalassemia anemia, Down syndrome, or cleft lip was serious enough to warrant the use of GST. This raises the question as to how “serious” a genetic abnormality has to be before PND-TOP is justified. In a study that surveyed 1264 genetics professionals regarding what genetic conditions were considered “lethal disorders,” “serious but not lethal disorders,” and “not serious disorders,” there were extensive overlaps between the three categories, suggesting that “there [was] not sufficient consensus among experienced genetics professionals to define serious genetic conditions for purposes of law or policy” (Wertz and Knoppers Citation2002, p. 29). Since genetic disorders vary in expression and are perceived differently by individual patients, these genetics professionals preferred to leave to individual patients to decide, with the assistance of doctors, what conditions were considered “serious.” Given this limitation in defining the “seriousness” of a genetic disorder, the subsidiarity principle raises another poignant question: “Are there other alternatives besides PND-TOP to deal with the problems?” This is followed by another question: “Are there ways to reasonably and satisfactorily prevent or control the genetic condition postnatally instead of eliminating the fetus prenatally?” Many HKU-students in our study raised similar questions. Since the subsidiarity principle implies that whenever a medical treatment for a particular genetic condition becomes available, the legitimacy of using PND-TOP also becomes questionable (Pennings and van Steirteghem Citation2004) this contributes to the ambivalence surrounding this theme.

A third factor not intrinsic to the nature or application of GST that might have contributed to the ambivalence in this theme was related to HKU-students' attitude regarding genetic determinism and personal responsibility in health-related matters. HKU-students believed that genes only contribute partly to health and disease and the other important factor is human nurture which includes one's lifestyle, work environment, eating habits, etc. Students also placed strong emphasis on the importance of personal responsibility in one's own healthcare. The influence of these two factors also explained why students were unenthusiastic about using GST to identify genetic predisposition to chronic diseases such as breast cancer, heart disease, and dementia. Many students opined that having disease-predisposing genes is not equivalent to having the diseases which can be prevented or ameliorated by human efforts in discharging personal responsibilities. Whether HKU-students were influenced by the Chinese holistic approach to disease and healthcare which emphasizes self-cultivation, lifestyle modification, and human–environment interaction was not clear and deserves further study in the future. But their cautious approach is in contrast to the widespread enthusiasm Westerners have for genetic testing of a wide spectrum of human diseases ranging from severe genetic diseases to psychiatric conditions and common disorders (Jallinoja et al. Citation1998, Iredale and Longley Citation2000).

Genetic engineering and tampering with nature (Themes C, D, and K)

The conservative attitude HKU-students had towards GST became even more obvious about genetic engineering. Their mean scores for genetic enhancement or modification were all below 3.0 except for transfer of human DNA to other organisms for medical purposes. Although many interviewees acknowledged the values of GM micro-organisms for innovative therapy, and GM crops for improved food quality and national economy, these advantages were outweighed by their concerns with unknown risks and harms. These findings are consistent with previous reports about the conservative attitude towards GM food among Chinese in Hong Kong (Hui et al. Citation2009), Mainland China (Zhang 2005, Wang Citation2003), and Taiwan (Chen and Li Citation2007). Specifically, HKU-students found it completely unacceptable to use GST for human enhancement even if it meant that their children would become more competitive or successful; this response was identical to the responses provided by the Hong Kong general public (Hui et al. Citation2009), and interviewees' testimonies indicated that their rejection of genetic enhancement was related to the deep-rooted Chinese worldview that there is a “natural order” ordained by T'ian (heaven) that human persons should not tamper with (Hui Citation1999). Initially we were surprised to find that HKU-students studying in the top university in Asia and Hong Kong's general public shared the same conviction that genetic engineering offended T'ian, a metaphysical notion that many modern Chinese would hold as superstitious. This puzzle was solved when it became clear that HKU-students understood “nature” not only as T'ian provided by Chinese cultural traditions, but also as the Christian God or the balanced ecosystem in nature, and they believed that modifying crops, meat, and human traits transgresses and disturbs the natural order established by these entities, leading to unpredictable harmful consequences in various forms of natural disasters. This seems to be the prevalent value held by Hong Kong citizens, and until this deeply ingrained cultural belief is fully reconciled with the benefits of GST, it is unlikely that they will be easily persuaded to change their negative attitudes towards GST (Catz et al. Citation2005).

Sharing genetic information with family members (Theme I)

In comparison with some studies in the West (Pentz et al. Citation2005, Stoffel et al. Citation2008), HKU-students were less willing to share GI with family probably because in the former subjects were largely at-risk family members who were prepared to be tested, whereas HKU-students were healthy subjects whose responses were based on hypothetical situations. HKU-students felt obligated to share GI with their parents, spouse, siblings, and children either because of close blood ties or because of sharing the same household, in keeping with other studies (Claes et al. Citation2003). In contrast, they were much less willing to share GI with their grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins, believing that grandparents might be too old to understand GI or too easily alarmed by such news. Generation gap and concern about upsetting others have previously been identified as barriers to GI dissemination (Green et al. Citation1997, Barsevick et al. Citation2008), and for our subjects there was an additional Chinese cultural convention of filial piety which considers it unfilial to alarm senior family members with burdensome and worrisome news. HKU-students' reluctance to inform uncles, aunts, and cousins, etc. was because these extended family members had much less contact with them and their fear of stigmatization or discrimination if the family members were told of the GI. These findings concurred with the barriers to GI communication identified by others (Benkendorf et al. Citation1997, Kenen et al. Citation2004, Stoffel et al. Citation2008). The idea that Chinese people embrace a strong familism that would motivate them to share GI with extended family members was not evident among HKU-students. We speculate that HKU-students were more influenced by modern Western culture of individualism and autonomy that might have diluted the preconceived strong sense of familism.

Abuse of genetic information and public trust (Themes E and H)

HKU-students lacked confidence that GI would be used fairly in Hong Kong and believed that public trust in the protection of genetic privacy and prevention against genetic discrimination was weak (Theme H). They opined that although genetic discrimination was immoral and should be illegal, in reality it had been practiced by insurers and employers, and to a lesser degree by schools (Theme E). Public trust is crucial for wide societal acceptance of GST and its application, and in the present study, HKU-students expressed confidence neither in GST itself nor in the government's ability to prevent abuses of GI. In recent years, it has been recognized that, to enhance public trust in policymaking, public engagement through informal sharing of information, conferences, citizen panels, etc. is more effective than simply inculcating the public with knowledge (Barnett et al. Citation2007). This is something that scientists, medical professionals, and policymakers in Hong Kong should pay due attention to. In recent bioethics discourses, emphases have been put on the “revolutionary” changes of genomic medicine and the ELSI of GST have been relatively overlooked (Wilkinson and Targonski Citation2003, Evans Citation2007). This “triumphalistic” discourse presupposes that genetic testing is accurate, unambiguous, and informative. However, critics have challenged the reliability of genetic testing and questioned the worthiness of the routine applications of GST (Foster et al. Citation2006, Burke and Psaty 2007). It seems that to earn public trust in GST, scientists and policymakers must maintain their integrity in their dissemination of genomic knowledge to the public to truthfully and ethically report both successes and failures. Furthermore, public trust in GST application also depends on the performance of other sectors of a community such as the healthcare profession, government, legislative body, and business firms, rather than relying on the potency of scientists alone (Traulsen et al. Citation2008). Hence, improving the quality of civil services, minimizing the occurrence of errors and misconduct in healthcare services, enhancing self-regulation in business firms, fostering public interest-based legislation, and ensuring effective law enforcement are measures that may increase the public's confidence in GST applications in the future.

The relation between knowledge and attitude regarding GST

Recent studies have indicated that public support of GST does not entirely depend on how much the public knows about GST, and people with more knowledge may be more pessimistic about its future application (Midden et al. Citation2002). While scientific knowledge may influence public attitudes towards the applications of GST, the particularity of each application and the “social location” of the individual also play a role in determining one's attitude (Sturgis et al. Citation2005, Christoph et al. Citation2008). For example, German consumers' acceptability of GM food has been found to depend on factors other than knowledge. These findings suggest that, apart from knowledge, “culture, economic factors, social and political values, trust, risk perception, and worldviews are all important in influencing the public attitude towards science” (Sturgis and Allum Citation2004, p. 58). As we have seen, the data in this study do not support the notion that “to know science is to love it,” i.e. better informed persons are more supportive or less critical of GST applications. Despite this, intensifying the dissemination of scientific and medical knowledge is still desirable, for by exposing people to the benefits and risks of GST they may at least become more competent to make informed decisions.

Conclusion

The current study revealed that HKU-students were ambivalent about the application of GST. The interview findings revealed that the “neutrality” in the survey results was caused by genuine controversies in each theme with substantive reasons provided by the opposing sides. The results of this study emphasize the importance of public consultation before each application of GST is contemplated, so that all possible aspects of the ESLI of the proposal will be adequately represented. This study also revealed that in several themes HKU-students were influenced by deep-rooted values embedded in Chinese cultural traditions, emphasizing that the reception of GST is culturally sensitive. The present study has several limitations. First, we only included HKU-students as the participants and they were elite intellectuals. Their opinions did not fully reflect the views of other sectors of society. A more accurate picture might be obtained by interviewing members of the general public. Second, although the questionnaire in Part 1 was made bilingual (Chinese and English) in order to eliminate racial and linguistic biases, all the HKU-students interviewed in Part 2 were Cantonese speakers. Hence, the voices of non-Cantonese speaking students who had participated in Part 1, if any, were unheard. A more accurate picture might be obtained by interviewing some non-Cantonese students.

References

- Barnett, J., Cooper, H., and Senior, V., 2007. Belief in public efficacy, trust, and attitudes toward modern genetic science, Risk Analysis 27 (4) (2007), pp. 921–933, (doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2007.00932.x).

- Barsevick, A. M., et al., 2008. Intention to communicate BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic test results to the family, Journal of Family Psychology 22 (2) (2008), pp. 303–312, (doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.303).

- Benkendorf, J. L., et al., 1997. Patients' attitudes about autonomy and confidentiality in genetic testing for breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility, American Journal of Medical Genetics 73 (3) (1997), pp. 296–303, (doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19971219)73:3<296::AID-AJMG13>3.0.CO;2-E).

- Bombard, Y., et al., 2009. Perceptions of genetic discrimination among people at risk for Huntington's disease: a cross sectional survey, British Medical Journal 338 (2009), p. b2175, (doi:10.1136/bmj.b2175).

- Burke, W., and Psaty, B. M., 2007. Personalized medicine in the era of genomics, Journal of the American Medical Association 298 (14) (2007), pp. 1682–1684, (doi:10.1001/jama.298.14.1682).

- Catz, D. S., Green, N. S., and Tobin, J. N., 2005. Attitudes about genetics in underserved, culturally diverse populations, Community Genetics 8 (3) (2005), pp. 161–172, (doi:10.1159/000086759).

- Charmaz, K., 2006. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage; 2006.

- Chen, M., and Li, H., 2007. The consumer's attitude toward genetically modified foods in Taiwan, Food Quality and Preference 18 (2007), pp. 662–674, (doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2006.10.002).

- Christoph, I. B., Bruhn, M., and Roosen, J., 2008. Knowledge, attitudes towards and acceptability of genetic modification in Germany, Appetite 51 (2008), pp. 58–68, (doi:10.1016/j.appet.2007.12.001).

- Claes, E., et al., 2003. Communication with close and distant relatives in the context of genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in cancer patients, American Journal of Medical Genetics 116 (1) (2003), pp. 11–19, (doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.10868).

- Evans, J., 2007. Health care in the age of genetic medicine, Journal of American Medical Association 298 (22) (2007), pp. 2670–2672, (doi:10.1001/jama.298.22.2670).

- Foster, M. W., Royal, C. D.M., and Sharp, R. R., 2006. The routinisation of genomics and genetics implications for ethical practices, Journal of Medical Ethics 32 (2006), pp. 635–638, (doi:10.1136/jme.2005.013532).

- Furu, T., et al., 1993. Attitudes towards prenatal diagnosis and selective abortion among patients with retinitis pimentos or choroideremia as well as among their relatives, Clinical Genetics 43 (3) (1993), pp. 160–165, (doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1993.tb04463.x).

- Garel, M., et al., 2002. Ethical decision-making in prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy: a qualitative survey among physicians and midwives, Prenatal Diagnosis 22 (2002), pp. 811–817, (doi:10.1002/pd.427).

- Green, J., et al., 1997. Family communication and genetic counseling: the case of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, Journal of Genetic Counseling 6 (1997), pp. 45–60, (doi:10.1023/A:1025611818643).

- Hui, E., 1999. "A Confucian ethic of medical futility". In: Fan, R., ed. Confucian bioethics. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 127–163.

- Hui, E., et al., 2009. Opinion survey of the Hong Kong general public regarding genomic science and technology and their ethical and social implications, New Genetics and Society 28 (4) (2009), pp. 381–400, (doi:10.1080/14636770903314517).

- Human Genome Project (HGP) Informaton, 2008. Ethical, Legal and Social Issues [online]. US Department of Genome Programs. Available from: http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/elsi/elsi.shtml [Accessed 17 March 2010]..

- Iredale, R., and Longley, M. J., 2000. Reflections on citizens' juries: the case of the citizens' jury on genetic testing for common disorders, Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics 24 (2000), pp. 41–47, (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2737.2000.00122.x).

- Jallinoja, P., et al., 1998. Attitudes towards genetic testing: analysis of contradictions, Social Science & Medicine 46 (1998), pp. 1367–1374, (doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00017-3).

- Kenen, R., Arden-Jones, A., and Eeles, R., 2004. We are talking, but are they listening? Communication patterns in families with a history of breast/ovarian cancer (HBOC), Psycho-oncology 13 (2004), pp. 335–345, (doi:10.1002/pon.745).

- Leung, T., et al., 2004. Attitudes towards termination of pregnancy among Hong Kong Chinese women attending prenatal diagnosis counselling clinic. Prenatal Diagnosis, 24 (7), 546–551..

- Marteau, T. M., 1993. Psychological consequence of screening for Down's syndrome, British Medical Journal 307 (6897) (1993), pp. 146–147, (doi:10.1136/bmj.307.6897.146).

- Midden, C., et al., 2002. "The structure of public perceptions". In: Bauer, M. W., and Gaskell, G., eds. Biotechnology: the making of a global controversy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 203–223.

- Ness, D. L., et al., 2004. Faces of genetic discrimination: how genetic discrimination affects real people [online]. Washington, DC: Coalition for Genetic Fairness; 2004, Available from: http://www.nationalpartnership.org/site/DocServer/FacesofGeneticDiscrimination.pdf?docID=971 [Accessed 27 February 2010].

- Pennings, G., and van Steirteghem, A., 2004. The subsidiarity principle in the context of embryonic stem cell research, Human Reproduction 19 (5) (2004), pp. 1060–1064, (doi:10.1093/humrep/deh142).

- Pentz, R. D., et al., 2005. Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer family members' perceptions about the duty to inform and health professionals' role in disseminating genetic information, Genetic Testing 9 (3) (2005), pp. 261–268, (doi:10.1089/gte.2005.9.261).

- Stoffel, E. M., et al., 2008. Sharing genetic test results in Lynch Syndrome: communication with close and distant relatives, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 6 (3) (2008), pp. 333–338, (doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.014).

- Sturgis, P., and Allum, N., 2004. Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes, Public Understanding of Science 13 (1) (2004), pp. 55–75, (doi:10.1177/0963662504042690).

- Sturgis, P., Cooper, H., and Fife-Schaw, C., 2005. Attitudes to biotechnology: estimating the opinions of a better-informed public, New Genetics and Society 24 (1) (2005), pp. 31–56, (doi:10.1080/14636770500037693).

- Traulsen, J. M., Bjőrnsdóttir, I., and Almarsdóttir, A. B., 2008. I'm happy if I can help: public views on future medicines and gene-based therapy in Iceland, Community Genetics 11 (2008), pp. 2–10, (doi:10.1159/000111634).

- Turney, J., 1995. The public understanding of genetics – where next?, European Journal of Genetics in Society 1 (2) (1995), pp. 5–20.

- Wang, Z., 2003. Knowledge of food safety and consumption decision: an empirical study on consumer in Tianjing, China, China Rural Economy 4 (2003), pp. 41–48.

- Wertz, D. C., and Knoppers, B. M., 2002. Serious genetic disorders: can or should they be defined?, American Journal of Medical Genetics 108 (2002), pp. 29–35, (doi:10.1002/ajmg.10212).

- Wilkinson, J. M., and Targonski, P. V., 2003. Health promotion in a changing world: preparing for the genomics revolution, American Journal of Health Promotion 18 (2) (2003), pp. 157–161, (doi:10.4278/0890-1171-18.2.157).

- Williams, S., et al., 2009. The genetic town hall: public opinion about research on gene, environment and research. Washington, DC: Genetics and Public Policy Center, Johns Hopkins University; 2009.

- Zhang, X., 2005. Chinese consumers' concerns over food safety: case of Tianjin, Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing 17 (1) (2005), pp. 57–69, (doi:10.1300/J047v17n01_04).

Appendix. Distribution of faculty affiliation of 400 HKU students