Abstract

In 1999, a small group of genomic entrepreneurs and local politicians started mobilizing the idea of founding a national genomics institute in Mexico. Approximately four years later, and after 18 months of congressional debate, the Mexican National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN) was established by presidential decree. As scholars, we are interested in how the call for a high-tech, high-cost genomics institute was able to gain political traction in a country, where many people struggle to secure access to even the most basic level of health care. Those behind the establishment of the INMEGEN used what we call technologies of bioprophecy to present it as a modernizing institution that would move the nation into the “new world order” by bringing not only biological and economic health, but also scientific prestige to Mexico.

Introduction

In 1999, a small group of genomic entrepreneurs and local politicians started mobilizing the idea of founding a national genomics institute in Mexico. Approximately four years later, and after 18 months of congressional debate, the Mexican National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN) was established by a presidential decree. As scholars, we are interested in how the call for a high-tech, high-cost genomics institute was able to gain political traction in a country where many people struggle to secure access to even the most basic level of health care.

Shedding light on such issues requires a form of enquiry that examines emerging scientific ventures vis-à-vis the broader political agendas of the nation states in which they are embedded. We combine an analysis of techno-scientific imaginaries with examinations of what we characterize as bioprophecy: a mixture of discursive and bioeconomic technologies of future telling designed to give national biotech projects their political appeal. If the imaginaries concept can be used to demonstrate how national interests are incorporated into techno-scientific projects, through the notion of bioprophecy, we highlight how human actors employ tactics to align their work with such interests. Those behind the INMEGEN present it as a modernizing institution that would move the nation into the “new world order” by bringing not only biological and economic health, but also scientific prestige to Mexico.

In this article, we follow a growing body of literature that demonstrates how imagined forms of life and social order describe and prescribe futures while giving shape and meaning to the present (Marcus Citation1995; Fujimura Citation2003; Fortun and Fortun Citation2005; Jasanoff and Kim Citation2009). Among this corpus of works are studies illustrating that “third world” nations are increasingly looking to biotechnology, especially genomics, as cornerstones for national development (Rajan Citation2006; Benjamin Citation2009; Jasanoff and Kim Citation2009; de Vries and Pepper Citation2012). Other work has explicated how emerging assemblages of governmental, private, and academic actors have the possibility to transform the significance of a population's biological substance into something of a patrimonial good imbued with social, political and economic value (Rabinow Citation1999) to the point that it can recalibrate national identity with a deep biological basis (Fortun Citation2008).

These studies both add to and complicate the work of Benedict Anderson (Citation1991) who provides an historical account of the rise of the modern nation as an inherently imagined social, cultural, and sovereign community. It is an “imagined community” because it is not based on actual everyday contact between its members, but is produced through history and political technologies such as the census, the museum and mapping.Footnote1 It is through these technologies that nationalistic pride, political projects, and the rights and responsibilities of citizens are produced. How do these accounts aid our task, that of answering how a high-cost, high-tech institution gained political backing?

In order to provide a conceptual link between scientific and political agendas, Jasanoff and Kim (Citation2009, 120) offer the notion of “national sociotechnical imaginaries,” which they describe as “collectively imagined forms of social life and social order reflected in the design and fulfilment of nation-specific scientific and/or technological projects.” In tracing the development of the INMEGEN, we argue that analysis of such imaginaries calls for a critical examination of the temporal aspects of contemporary rationality. Not only are they future orientated, imaginaries are inherently political and emerge at the nexus of science and statecraft. Meditating on the calls by locally based scientific experts for a state fostered search for genomic medicine in Mexico, we develop the imaginaries concept in light of critical scholarship on time, temporality, and prophecy (Luhman Citation1998; Guyer Citation2000, Citation2007). This involves analysis of how imaginaries are coproduced (Jasanoff Citation2004) by scientific and political projects as they feedback into each other. Furthermore, we demonstrate how the group of genomic entrepreneurs behind the INMEGEN were able to “fix” their projects to national goals by bringing possible futures into the present.

Bioprophecy: fixing the future in the present

In Observations on Modernity, the sociologist Niklas Luhman (Citation1998) asks “In what way does the future manifest itself in the present?” Rather than trying to offer a concrete answer, Luhmann reflects on key understandings of this relationship as they changed from antiquity to the present. In doing so, he describes a transition from authority (under the gods) to what he calls a “politics of understanding” (1998, 67). This movement coincided with the birth of “modern” society as an unfinished project in which “much of what we know of the future depends on the decisions we must make now.” These understandings are similar to imaginaries in that they do not provide strong policy agendas but rather fix reference points. The “problem of modernity,” according to Luhman (Citation1998, 69–70), thus exists “in the dimension of time”:

In the dimension of time, the present refers to a future that only exists as what is probable or improbable. Said another way, the form of the future is the form of probability that directs a two-sided observation as something more or less probable or more or less improbable, with a distribution of these modalities across everything that is possible.

Similarly, anthropologists have become interested in emergent temporal modes as they exist in political and scientific culture. In her article “Rationality or Reasoning?” anthropologist Jane Guyer (Citation2000) emphasizes the import of three general moves within economics for understanding the contemporary relationship between these two forms of decision-making. These are

a turn from an analytical to a normative orientation, a channeling of all questions through the increasingly powerful mesh of statistics and mathematics, and the formation of links to various bodies whose main purpose is not to understand the present and the past for theoretical and comparative purposes but to build the future. (Guyer Citation2000, 1012, emphasis added)

The increasing interrelation of science and capitalism has produced new, promissory modes of future-oriented speculation (Cooper Citation2008; Helmreich Citation2008). Writing on this relation, scholars have identified how “economies of hope,” with their material, economic, and affective basis come to steer the “possibilities inherent in the science of the present” (Novas Citation2006, 1). Through the notions of biocapital (Rajan Citation2005, Citation2006) and biovalue (Waldby Citation2002), others have highlighted how the dynamic interaction between markets and biotech enterprise comes to afford new value to human biological substances. In private genomics, for example, speculation may be produced through a particular “epistemic rationality” in which the elucidation of futures becomes central to the making and placing of value in the present (Rajan Citation2005, 24). While these studies highlight how market dynamics have emphasized the speculative dynamics of various biotechnical enterprises, following Guyer our goal is to examine the role of contemporary economic rationality in laying the political foundations for Mexico's national genomics institute. The lead up to the founding of the INMEGEN demonstrates how emergent modes of rationality gave ground to imagined futures.

In a country where people often struggle to claim even the most basic level of health care, demonstrating the importance of genomic medicine for public health was both a necessary and major act in the push for the INMEGEN. Below we show that plotting what the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (for example, 2006) has called a future “bioeconomy” was central to establishing the INMEGEN because it provided a rational basis for creating the genomics institute. Here, imagined futures were produced alongside models of the future that were embodied in graphs and images. This work translated genomic visions into mobile and politically legible resources in the form of statistical projections that fitted snugly into Mexico's continued national project: it promised to help move the country into development, allowing it to achieve “modernity” through “genomic sovereignty.” In meditating on the emergence of the INMEGEN and the imaginaries surrounding it, we present two primary observations that can be condensed into the concept of bioprophecy.

First, the production of those imaginative resources used to relate the INMEGEN to the public good involved (perhaps even depended upon) the use of specific technologies of future telling. Moreover, the genomic imaginaries that motivated and were coproduced with the INMEGEN Feasibility Study (see below) where shaped by a priori decision-making practices. Modeling the future through economic predictions provided a rational ground upon that in itself called for action: the models. The predictions helped to provide a link between the health of individuals, the racialized “Mestizo” population, and ultimately the future of the nation. With the possibility of further exploitation leading to biological, economic, and political degradation, genomic medicine was not targeted solely at sick bodies; it was targeted at a weakening and at risk Mexico.

Second, an examination of the ways in which scientific projects are solidified, mobilized, and coproduced with imaginaries opens up new avenues for thinking about the nature that time and temporality are given in political cultures and state practices. The tellings and imaginings in and around the Feasibility Study brought the future as a set of possibilities into Mexico's scientific and political present. The economic forecasts provided a specific rationality that is given its flavor in the way that it establishes a link between the future and the present as much as through the outlining and weighing up of benefits and costs. This link is by no means teleological. Rather, it reveals a specific rendering of contingency in which both the future and present are splintered, multiple, and in need of ordering and arrangement. Moreover, what was at stake in this future/present was the very health of the nation. This is what the Mexican Congress was dealing with when they were lobbied by the genomic entrepreneurs behind the INMEGEN.

Seeking modernity in the “bioeconomy”

Since 2004, the INMEGEN has been carrying out broad scale research into the genetic structure of the “Mexican genome” with the aim to produce medicine tailored to local health problems. Making sense of the uptake and political appeal of having a national genomics institute in Mexico requires understanding the larger political, medical, and genomic milieu in which it was proposed. When characterizing the history of Mexican identity and nationalism, social scientists and public intellectuals often note the paradox that has emerged throughout Mexico's modernization project (see Lomnitz 2002). In particular, they reference and trace the emergence of a political desire to move the nation into “modernity” without sacrificing those invented traditions that form the basis of Mexican nationalism. How is Mexico to follow in the footsteps of other countries while preserving its own cultural and political identity? Social diagnosticians such as the public intellectual Roger Bartra (Citation1992) have pointed out that a possible approach for characterizing the Mexican present is by highlighting the mix of a particular form of social and political chaos and aspirations toward a modernity always beyond the nation's reach. And as anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz (2002, 114–117) has argued, in this context the focus on and toward achieving modernity has moved the notions of “progress,” “democracy,” and “development” to the forefront of the political arena.

At the level of the Mexican nation state, science is viewed as a development tool (Fortes and Adler-Lomnitz Citation1990; Lomnitz 2002). The Mexican state has implemented various bureaucratic and legalist initiatives designed to order science in accordance with national interests. While Schwartz-Marín (Citation2011; Schwartz-Marín and Restrepo Citation2013) has provided an in depth account of the reforms related to the INMEGEN, Taylor-Alexander (Citation2011, Citation2013a, Citation2013b) has demonstrate how bioethics has emerged as a tool for ordering science and globalization in Mexico. In both of these cases, a number of paradoxes remain, especially the desire to build relations with foreign enterprises while solidifying Mexico's individuality and sovereign status. Moreover, what is at stake is the transformation of Mexico into a primary producer rather than consumer of global capital, as is often perceived as the status quo amongst Mexican scientists and politicians.

In the realm of public health, the Mexican government has faced a number of epidemiological juxtapositions as part of its constitutional duty (Article 4) to uphold “the right to the protection of health” for its citizens. The main issues are how to account for the continued prevalence of “old” infectious diseases in rural parts of the country and the growth of chronic health conditions such as diabetes and hypertension alongside these areas and in population dense urban centers. For example, while epidemiological projections present diabetes as the nation's foremost health problem, when compared to Chiapas, the poorest state in the country, the prevalent illnesses are totally different. The double epidemiological burden demands that Mexico (and other “developing countries”) adapt to the challenges of chronic and very costly disease and at the same time take care of infectious diseases commonly related to poverty. The interest in addressing this prolonged and polarized epidemiological burden was one of the priorities of what was known as the neo-sanitarian (i.e. neo-liberal) health movement in Mexico of which the future INMEGEN director Dr Soberon and then (2000–2006) current Mexican minister of health Dr Frenk were leading figures.

The mobilization to establish a national genomics institute emerged vis-à-vis local health problems, including spiraling health care and social security costs faced by the Federal Government, as well as the broader international milieu of genomic research. This milieu included a number of important projects, many of which have been framed vis-à-vis what the OECD as part of its “International Futures Program” calls the new “bioeconomy.” That is, “the set of economic activities relating to the invention, development, production and use of biological products and processes … [that] could make major socioeconomic contributions in OECD and non-OECD countries” (OECD Citation2006). As a number of scholars have noted (Hardy et al. Citation2008), calls have been made to ensure that “southern” nations are not excluded from the emergence and capitalization of this new “bioeconomy.”

The push for the INMEGEN emerged in a context of emerging scientific disparities and “bioeconomic” possibilities. The International Haplotype Mapping (HapMap) project had excluded researchers in various nations, especially in countries with large population diversity such as Mexico. The related emergence of public health genomics and its advocates promised an alternative to the notion of “individualized medicines” that underlie the work of “northern” genomics institutions and pharmaceutical companies (Hardy et al. Citation2008). These companies have an increasing interest in the “ethnic” drug market, and so often wish to patent particular genes or related findings that could be used for pharmaceutical development (Rajan Citation2006; Hardy et al. Citation2008; Fortun Citation2008; Benjamin Citation2009). It was in this context that collaboration between academic, government, and private institutions in Mexico emerged, which resulted in the publication of the IFS (Citation2001). This study, along with the initial report emphasized both the future costs and consequences that would plague Mexico if it did not participate in the “genomics revolution” and enter into the “new world order of health care” (Jiménez-Sánchez Citation2004, 26).

Imaginaries and (bio)economics

Sociotechnical imaginaries are not fixed and because of this are often at the center of political and cultural practices designed to stabilize them according to the interests of various actors.

S[cience] & T[echnology] policies thus provide unique sites for exploring the role of political culture and practices in stabilizing particular imaginaries, as well as the resources that must be mobilized to represent technological trajectories as being in the “national interest.” (Jasanoff and Kim Citation2009, 121)

Importantly, the idea of a “Mexican Genome” itself emerged through the political lobbying carried out by the working group. It was not until after the working groupFootnote2 approached the Mexican Congress with the INMEGEN proposal that the results of the Human Genome Project were made public. What gave credence to the idea that there was such a thing as the “Mexican Genome” was the unique relation between Mexican national identity and the history of ethno-racial admixture, mestizaje, which was given a new meaning in the context of population genomics (see below).

With the state being the primary provider of health care to the Mexican population, genomic medicine held out the promise of decreasing not only national rates of disease and mortality but also the size of the always-stretched federal healthcare budget. Genomics was presented as a way to improve the health and vitality of the population, cut health expenditure, fuel economic growth, improve infrastructure, and ultimately aid national development. Moreover, the study highlighted the potential of genomic medicine to transform Mexico into a knowledge-based economy, using genomics as its strategic platform to reach a bioeconomy by 2030. A number of hopes and fears surrounded and were imbued in the visions of the future provided in the feasibility study and the later working program. Here, the genome of the Mexican population was afforded a new value due to the promise held out by genomic medicine, a promise that, it was argued, needed to be capitalized upon.

Two seemingly contradictory fears were present in lobbying activities surrounding the INMEGEN. These emerged in and alongside the discourse of “genomic sovereignty”: first was the fear that if medicines targeted and tailored to the genetic structure of the Mexican population were not developed in Mexico they would not be developed at all; second was the fear that such therapeutics could be developed and patented outside of Mexico, which would continue the nations dependence upon (and its being held at the whim of) multinational pharmaceutical companies. Thanks to such visions of risks, and possible lost opportunities, Mexican DNA emerged as a public good in need of sovereign protection, and the genomics imaginary emphasized national development and sovereignty:

Mexican migratory history and its complex ethnic composition, make it impossible to import the genomic knowledge of Mexicans, and its future medical applications … If in any case it is possible to import this knowledge, it would only make Mexicans more dependent on foreign countries. If developed internally, it would generate huge healthcare savings, and even better, it would become the seed for an economy based on knowledge. (Jiménez-Sánchez Citation2002a in Schwartz-Marín and Silva-Zolezzi Citation2010, 496)

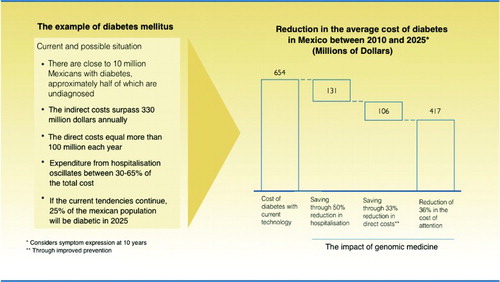

Prophetic and politically legible technologies were used to “fix” the INMEGEN to the interests of the Mexican state, allowing it to gain political traction. Science studies scholars have noted that the potency of scientific images stems both from the prestigious networks in which they are produced and the expertise of those who speak for them. In various public forums, experts are seen to act like ventriloquists that merely convey the “objective” truth inherent within the image itself (Dumit Citation2004; Latour Citation2004) rather than as actors imbuing it with meaning. The entrepreneurs behind the INMEGEN presented genomic projections as “objective” images that outlined possible bioeconomic futures. One graph was used in the feasibility study, the working report, and many other contexts that where witnessed during the fieldwork carried out by Schwartz-Marín. It exists as more than a suitable example of how the Mexican genomic imaginary was co-produced alongside broader sociotechnical imaginaries ().

Figure 1. The example of diabetes mellitus: reduction of the mean costs of diabetes in Mexico between 2010 and 2025.Source: Jiménez-Sánchez (Citation2004, 20); adapted/translated by Taylor-Alexander.

According to Taracena and Jiménez-Sánchez (Citation2005), the methodology applied in this analysis is represented in :

considers the comparison between the total cost of creating the INMEGEN against the cost of not doing so; defined as the financial burden that represents to the Health System posed by the treatment of the two most common diseases in Mexico: diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension; functioning on the assumption that genomic medicine will allow for the identification of the predisposition or resistance to illnesses. The economical evaluation was made under the calculus of the Present Net Value, and the Annual Equivalent Cost, for a horizon of 10 years, as a first exercise, which was later extended to a period of twenty-five years, by the solicitude of the Secretary of Treasury and Public Credit.

The image thus compares the total cost of producing the INMEGEN against the savings produced in treating two diseases of sanitary priority in the country. It was used to show Mexican Congressmen that such an investment was not only based on moral and scientific urgency, but also on a good cost-saving opportunity strategy. In doing so, it helped to inspire national authorities that have historically invested little in Science and Technology. The graph was a prophetic resource that became a central political asset in a context, where the future needed to be mobilized in order to act in the present. In this respect, one of the leading neo-sanitarians, and also genomic entrepreneur, Dr Frenk, relayed in an interview that they had to be a bit “deterministic on the presentation of the graphs and the economic benefits of genomics in order for the congress to have a clear picture of the importance of these topics.”

These promises of public health were most visible in the INMEGEŃs feasibility study (2001, 25), which circulated the promise of decreasing by 36% the total cost of diabetes mellitus. The Congress took the good news of a technology that could help them decrease the expenses of health without further examination of its premises, making a heavy investment in the INMEGEN. Moreover, the economic analysis on which this graph was produced derives from the very premises put forward by the international epistemic community; it is a self-referential tool to look toward a desired future. This graph projects a future that is as much the product of international organizations' projections of knowledge on the issue area and a future bioeconomy (WHO Citation2002; OECD Citation2006), as an ad-hoc visual tool to assert the need for present, urgent action.

The graph was one of many resources that were produced as a means of stabilizing the importance of genomic medicine for Mexico's national development. Other resources were previous scientific findings, publications by international organizations and universities calling for genomic institutes in developing countries. Most importantly in this vision of risk and opportunity was the focus on the threat to Mexico's genetic patrimony (a problematic concept in its own right cf. Schwartz-Marín Citation2011; Schwartz-Marín and Restrepo 2013) if the “Mestizo genome” were to be patented and repackaged as drugs that the nation's citizens would ultimately have to purchase from foreign companies:

A Mexican genomic platform is considered key to discouraging non-Mexican research and development of Mexican-specific products and services. Anecdotal reports indicate that U.S. field workers have, in the past, collected blood samples from Mexican indigenous populations and taken the samples back to the United States. Presumably, polymorphisms could be identified and genomic-specific medicines made and sold at U.S. prices. If this were to happen, Mexicans would likely not be able to afford the drugs, thereby worsening economic and inequity problems that already exist. (National Academic Press Citation2005, 10–12)

Establishing the INMEGEN thus inter alia involved both imagining and plotting possible futures. The above graph plotted a “deterministic” picture of two futures – one with and the other without the INMEGEN – in a context where the future/present, the temporal imaginative space in which action needs to be taken, was splintered and multiplied. As we noted above, Mexican public intellectuals have characterized the nation's socio-political state in terms of a chaotic state of affairs. This can be seen in the continued political corruption as well as the exploitation of Mexican individuals and institutions by foreign actors. In this rendering, the Mexican present needs to be ordered to reach the Modernity that has for so long remained beyond arms reach.

In Congress: disputed science, truthful economics and past plundering

Few within the Mexican Congress disagreed with the need for a Mexican program on genomic research. Though there was not a complete acceptance of the notion of “genomic sovereignty” or the “Mexican Genome.” Rather, it was the language of economics that underpinned the importance of the INMEGEN. Being able to negotiate inside the Mexican Congress was the product of a long, informal process of lobbying, by those heading the effort, with academics and policy-making peers, bureaucratic bodies, health authorities and all kinds of groups interested in genomic science. Documents available from this initial period are scarce, and remain scattered around many desks, except for the published articles, which are a synthesis of the most relevant premises of the IFS (2001).Footnote4

Through their continuous engagement with policymakers and strategic audiences, Jimenez Sanchez and those working with him had the opportunity to survey opinions on their project, and the possible objections that could be raised against them (CPMG Citation2003). During the initial years of promotion (1999–2001), they identified two principle challenges: to show that genomic medicine was not a high-end enterprise, meaning that it could be directed to address the country's most pressing health needs regardless of socioeconomic status; and to convince decision-makers not to free-ride (to use rational choice language) on the emerging scientific field that was globally framed as an international public good (UNESCO Citation1997; Frenk Mora Citation2001). This article has been dedicated to unpacking the tactics used to address these issues. Interestingly, it was the scientific, rather than the economic, presumptions underlying these strategies that gained critical attention.

In 2001 when the first statement on Mexican Genetic Uniqueness appeared on a written document (IFS 2001), the Human Genome Project was not yet finished. By 2002 when the “Mexican Genome” appeared in a public document (the IFS has remained out of public scrutiny), the HGP data were still not available to produce any genetic comparison, not even a very general one also because launching such comparison was precisely what was at stake. Nevertheless those behind the INMEGEN could publish the next phrase without generating scientific or political controversy:

Mexico has a population of unique genomic makeup as a result of its history. As of February 14, 2000, Mexico had a total of 97,483,412 inhabitants, occupying the 11th place among the most populated nations on earth, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 1.58%. The vast majority of the Mexican population emerged from a mixture between Meso-American native groups and Spaniards. (Jiménez-Sánchez Citation2002b, 32)

In the 18 months of lobbying in the Congress, many of those who were amongst the supporters of the Consortium Promoting Genetic Medicine, interrogated the existence of a “Mexican Genome” and the need for its sovereign protection, and yet when selling the project to Congressmen they all cooperated and silenced their critiques (see Schwartz-Marín and Restrepo 2013). The questionable science surrounding the creation of the INMEGEN was overshadowed by a dominant, near unquestionable narrative of exploitation and missed opportunities embodied in US–Mexican relations. This history provided the evidence necessary for the production of a new, high-cost enterprise in a context where the science underlying the Consortium's push was speculative at best. In this way, the past, specifically a Colonial past was mobilized to fix the future. The future was brought into the present, thanks to economic modeling, supported by the idea that time and history repeat itself, an argument that iteratively mobilized previous experiences of dispossession: “ we have to avoid that this national resource becomes appropriated and used in an almost exclusive fashion by foreign researchers as has happened before in archaeology, botany or zoology” (IFS 2001, 25). The cultivation of Barbasco for the production of synthetic steroids by the Syntex pharmaceutical company (see Laveaga Citation2009) was another highly cited example of a missed opportunity for progress that figured prominently in the new discourse of genomic sovereignty.

The logic was simple: in order to avoid missing yet another historical opportunity to achieve modernity, Mexicans needed to seize the bioeconomic assets latent in their own bodies and ancestral origins, and the way to do it was through genomic medicine. So, despite strong disagreements around the existence of a Mexican Genome, the coalition of scientists that pushed for the creation of the INMEGEN found in the sovereign protection of the Mexican Genome a strategic vehicle to make their project be heard clear and strong. Inside the Congress, what slowed down the negotiation was not disagreement amongst scientists, but fierce opposition coming from the Catholic Church, who thought that genomic medicine was a plan devised to massively clone babies, to serve as spare parts for ill person in wealthier countries.

In many ways, the major setbacks, as well as the most promissory arguments in favor of creating the INMEGEN had nothing to do with genomic medicine, but with the imaginations of possible futures that strategic audiences were able to mobilize inside the Congress or in mass media. In regard to the coalition of genetic scientists and medics who pushed for the INMEGEN, who were cooperating not because of shared scientific imaginaries (as a matter of fact most of them were deeply skeptical of the Mexican Genome) but because of shared economic imaginaries which gave special weight to biomedical science as a tool for progress and prosperity. As Dr Elias – pioneer of human genetics in Mexico – who after the creation of the INMEGEN became one of the most public critics of the Mexican Genome (during the congressional negotiations he was aligned and supportive of INMEGEN's advocates) explained that: he was not in favor of “sovereignty over genes, which was something irrational, he was in favor of “sovereignty over biomedical innovations” in order to avoid the practice of getting the patent and knowledge from Mexico and then moving to another country to enjoy the benefits (see Schwartz-Marín Citation2011; Schwartz-Marín and Restrepo 2013) ().

Figure 2. Reduction in the costs of the clinical assays with new biologically validated pharmaceutical products (in millions of dollars).Source: IFS (2001, 12); adapted/translated by Taylor-Alexander.

Not only did the INMEGEN provide a way to tackle the most pressing health problems of the nation, but a pathway to more fruitful and cheaper clinical trials. This was supposed to be achieved by reducing the number of patients, chemical compounds and time needed to do a clinical thanks to new genomic technologies that could, in principle, make the validation of biomedical innovations much more targeted and refined. Having a roadmap of Mestizo difference, did not only avoided possible colonial futures, but opened unprecedented ways to boost biomedical innovation, with the added advantage of having a flexible public institute that could deliver these economical benefits in the form of start-up, as well as public health interventions or products.

Such was the importance of the bioeconomical futures (graphically modeled either as new possibilities for clinical trials or public health interventions) for the stabilization of genomic medicine in Mexico, that many years after the negotiations inside Mexican Congress, the former Director of Research of the INMEGEN, Dr Max (Pseudonym), continued to state that a concrete way to claim sovereignty was by developing clinical trials, that by law needed to be designed, taking into account the biogenetic specificities of Mexicans (such as diet, genetic structure, response to alcohol etc. …; SM, Fieldnotes, December 2008). Again the national research on Mexican genetic “uniqueness” served the purposes of a future-oriented economic rationale:

Having created a national institute gives us advantages, we can easily move in the public field, and also in the private … there is new legislation on the international sphere, in different countries, these are establishing that if someone wants to introduce a new medication in the market, there should be genomic studies based on the populations of the market the company wish to enter into (Dr Max, int. 2008 Head of Research, INMEGEN)

Coda: fixing the future

Understanding how the INMEGEN gained political backing in a context of large health disparities involves an examination of Mexico's own political imagination and history. Aspirations toward modernity and development continue to play a central role here. The scientific imaginations of the likes of Drs. Jimenez-Sanchez and Frenk Mora where undoubtedly shaped by these nationalistic concerns as they worked to create a place for genomics in Mexico's national future. The resources that they deployed to do so, the economic predictions and bioprophetic graphs in particular, provided a legible technology that allowed the establishment of the INMEGEN as a rational political act.

The forms of social life and social order that were reflected in the imaginaries surrounding the INMEGEN highlighted security and risk, danger and desire. The primary actors involved in the push to establish the INMEGEN suggested that without immediate action, genomics would become another area in which the patrimony and life itself of the Mexican population could become dependent and exploited by its northern neighbors. They presented both statistical and discursive models before the Mexico Congress through which two probable futures were outlined. The INMEGEN Feasibility Study brought together a number of various resources that delineated a desirable picture of the future. It demonstrated, or better created, the need to work through these possible futures in the present. Here, the “bioeconomy” existed as much as an OECD buzzword as a set of politically legible and mobile resources embodied in graphs that were given meaning by the discourse surrounding them.

The significance of bioeconomic forecasting exists in more than the meaning that they are given through the contexts in which they are produced because they ultimately come to influence the trajectory of the projects that they are used in. Throughout this article, we have demonstrated that the particularities of the movement to establish the INMEGEN were themselves co-produced by the meeting of national and scientific imaginaries alongside the Mexico's particular epidemiological scenario. A primary role of economic models was to fix the future in the present – a present in which the future emerged as a double-sided coin to be stabilized as the opportunities that it presented flipped through time. In this case, fixing the future in the present took the form of establishing a political issue that needed to be grappled with by the Mexican Congress.

In other words, the simultaneous mobilization of graphic and discursive resources was central to the establishment of the INMEGEN because it helped turn genomics into an issue of national import. Prophetic graphs became a political technology of national significance. They mapped out the contingent nature of Mexico's genomic future, and in doing so turned the nation's scientific and political elites into both cartographers and creators of what Luhman (Citation1998) calls the “future/present.” Genomics was presented as a cure to the nations ills: by reducing costs associated with treating emergent epidemiological problems money saved could be used to treat infectious diseases; meanwhile the sovereignty and patrimony of the Mexican nation could be secured in the face of a global genomic regime.

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard Tutton and the rest of the team at New Genetics and Society as well as the three anonymous reviewers who provided invaluable commentary on an earlier version of this article. Samuel Taylor-Alexander thanks Sheila Jasanoff at the Program on Science, Technology, and Society at the Harvard Kennedy School, where some of the initial ideas for this piece were workshoped. Working with Ernesto has been a great pleasure. Ernesto Schwartz-Marín thanks all the people at the INMEGEN, who provided him with important documents and shared their time, especially Dr Irma Silva-Zolezzi, M.A. Alberto Arellano as well as Dr Julio Frenk Mora who gladly accommodated time for interviews in their busy schedule.

Notes

1. See also Simpson (Citation2000) on “Imagined Genetic Communities.”

2. An initial working party with members Mexico's National Autonomous University (UNAM), the privately backed Mexican Health Foundation (FUNSALUD), and health ministry was later formalized into the INMEGEN working group. This collaboration later expanded to include the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT).

3. Recent scholarship has highlighted the emergence of “Genomic Sovereignty” in Africa (de Vries and Pepper 2012).

4. See the published articles of Jiménez-Sánchez, from 2002 to 2005; the extremely redundant statements in the articles make it simple to follow the basic rhetoric of genomic medicine in Mexico. Three articles were written for the specific purpose of communication and lobbying (see e.g. Jiménez-Sánchez, Valdes Olmedo, and Soberon Citation2002a, Citation2002b).

References

- Anderson, B. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Bartra, R. 1992. The Cage of Melancholy: Identity and Metamorphosis in the Mexican Character. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Benjamin, R. 2009. “A Lab of Their Own: Genomic Sovereignty as Postcolonial Science Policy.” Policy and Society 28 (4): 341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2009.09.007

- Cooper, M. 2008. Life as Surplus: Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- CPMG. 2003. Consorcio Promotor de la Medicina Genomica discuss the pertinence of the laws and final meetings before the INMEGEN is accepted by the Congress. Meeting in what are now the offices of the CNB in Pichacho-Ajusco. Unpublished document.

- Dumit, J. 2004. Picturing Personhood: Brain Scans and Biomedical Identity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Fortes, J., and L. Adler-Lomnitz. 1990. Becoming a Scientist in Mexico. Philadephia: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Fortun, M. 2008. Promising Genomics: Iceland and deCODE Genetics in a World of Speculation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fortun, K., and M. Fortun. 2005. “Scientific Imaginaries and Ethical Plateaus in Contemporary U.S. Toxicology.” American Anthropologist 107 (1): 43–54. doi: 10.1525/aa.2005.107.1.043

- Frenk-Mora, J. 2001. México en el umbral de la era genómica. Impacto en la salud pública. Mexico City: FUNSALUD. Accessed September 9, 2013. http://www.funsalud.org.mx/quehacer/conferencias/eragenomica-abr20/frenk.pdf

- Fujimura, Joan. 2003. “Future Imaginaries: Genome Scientists as Sociocultural Entrepreneurs.” In In Genetic Nature/Culture: Anthropology and Science Between the Two-Culture Divide, edited by H. Goodman, Deborah Heath, and M. Lindee, 176–199. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Guyer, J. 2000. “Rationality or Reasoning? Comment on Heath Pearson's ‘Homo Economicus Goes Native, 1859–1945’.” History of Political Economy 32 (4): 1011–1015. doi: 10.1215/00182702-32-4-1011

- Guyer, J. 2007. “Prophecy and the Near Future: Thoughts on Macroeconomic, Evangelical, and Punctuated Time.” American Ethnologist 34 (3): 409–421.

- Hardy, B., B. Seguín, F. Goodsair, G. Jimenez-Sanchez, P. A. Singer, and A. S. Daar. 2008. “The Next Steps for Genomic Medicine: Challenges and Opportunities for the Developing World.” Nature Reviews Genetics 9 (Nature Supplements): S5–S9.

- Helmreich, S. 2008. “Species of Biocapital.” Science as Culture 17 (4): 463–478. doi: 10.1080/09505430802519256

- IFS (INMEGEN Feasibility Study). 2001. “Estudio de Factibilidad para el Establecimiento y Desarrollo del Centro de Medicina Genómica.” UNAM, SSA, CONACYT, FUNSALUD.

- Jasanoff, S, ed. 2004. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. New York: Routledge.

- Jasanoff, S., and S. Kim. 2009. “Containing the Atom: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and Nuclear Power in the United States and South Korea.” Minerva 47 (2): 119–146. doi: 10.1007/s11024-009-9124-4

- Jiménez-Sánchez, G. 2002a. Hacia el Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica, Informe de Actividades, Consorcio Promotor del Instituto de Medicina Genómica. Mexico City: Fundación Mexicana para la Salud.

- Jiménez-Sánchez, G. 2002b. “Áreas de oportunidad para la industria farmacéutica en el Instituto de Medicina Genómica de México.” Gaceta Médica de México 138 (3): 291–294.

- Jiménez-Sánchez, G. 2004. Programa de Trabajo para dirigir el Instituto Medicina Genómica 2004–2009. www.inmegen.gob.mx

- Jiménez-Sánchez, G., J. Valdés Olmedo, and G. y Soberón. 2002a. Desarrollo de la medicina genómica en México. Este país. 139, octubre, pp. 17--21.

- Jiménez-Sánchez, G., J. Valdés Olmedo, and G. y Soberón. 2002b. Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica. Este país. 141, diciembre.

- Latour, B. 2004. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Laveaga, G. S. 2009. Jungle Laboratories: Mexican Peasants, National Projects, and the Making of the Pill. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lomintz, C. 2002. Deep Mexico, Silent Mexico: An Anthropology of Nationalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- López Beltrán, Carlos. 2011. “Genómica Nacional: el INMEGEN y el Genoma del mestizo.” In Genes & mestizos: genómica y raza en la biomedicina mexicana, edited by J. López, 99–142. Mexico City, Mexico: Ficticia Editorial.

- López Beltrán, Carlos, García-Deister Vivette, and Rios Sandoval Mariana. 2014. “Negotiating the Mexican Mestizo: On the Possibility of a National Genomics.” In Mestizo Genomes: Race Mixture, Science andNation in Latin America, edited by Wade, et al. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Luhman, N. 1998. Observations on Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Marcus, George, ed. 1995. Technoscientific Imaginaries: Conversations, Profiles, and Memoirs. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- National Academic Press. 2005. An International Perspective on Advancing Technologies and Strategies for Managing Dual-Use Risks (Report of a Workshop). Washington, DC: National Academic Press.

- Novas, C. 2006. “The Political Economy of Hope: Patients’ Organizations, Science and Biovalue.” Biosocieties 1 (3): 289–305. doi: 10.1017/S1745855206003024

- OECD. 2006. International Futures Programme, The Bioeconomy to 2030: Designing Agenda. Paris: OECD.

- Rabinow, P. 1999. French DNA: Trouble in Purgatory. Chicago., IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Rajan, K. 2005. “Subjects of Speculation: Emergent Life Sciences and Market Logics in the United States and India.” Americal Anthropologist 107 (1): 19–30. doi: 10.1525/aa.2005.107.1.019

- Rajan, K. 2006. Biocapital: The Constitution of Postgenomic Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Schwartz-Marín, E. 2011. “Genomic Sovereignty and the ‘Mexican Genome’: An Ethnography of Postcolonial Biopolitics.” PhD Thesis, EGENIS-ESRC Centre for Genomics in Society.

- Schwartz-Marín, E., and E. Restrepo. 2013. “Biocoloniality, Governance, and the Protection of ‘Genetic Identities’ in Mexico and Colombia.” Sociology, 47 (5): 993--1010.

- Schwartz-Marín, E., and I. Silva-Zolezzi. 2010. “The Map of the Mexican's Genome” Overlapping National Identity, and Population Genomics.” Identity in the Information Society 3 (3): 489–514. doi: 10.1007/s12394-010-0074-7

- Scott, J. C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New York: Yale University Press.

- Simpson, B. 2000. “Imagined Genetic Communities: Ethnicity and Essentialism in the Twenty-First Century.” Anthropology Today 16 (3): 3–6.

- Taracena, E., and G. Jimenez-Sanchez. 2005. INMEGEN, innovación en la ciencia de la vida aplicada en la salud. Mexico City: IPADE.

- Taylor-Alexander, S. 2011. “Surgical Citizenship and Ethical Subjects: Reconstructing the Body Politic in Mexico.” PhD Thesis, Department of Anthropology, The Australian National University.

- Taylor-Alexander, S. 2013a. “On Face Transplantation: Ethical Slippage and Quiet Death in Experimental Biomedicine.” Anthropology Today 29 (1): 13–16. doi: 10.1111/1467-8322.12004

- Taylor-Alexander, S. 2013b. Bioethics in the Making: The Beginnings of Face Transplant Surgery in Mexico. Science as Culture. doi:10.1080/09505431.2013.789843. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09505431.2013.789843#.UjzydRaw06c

- UNESCO. 1997. “Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights.” UNESCO’s 29th General Conference, Paris, France, November 11.

- de Vries, J., and M. Pepper. 2012. “Genomic Sovereignty and the African Promise: Mining the African Genome for the Benefit of Africa.” Journal of Medical Ethics 38 (8): 474--478.

- Waldby, C. 2002. “Stem Cells, Tissue Cultures and the Production of Biovalue.” Health 6 (3): 305–323.

- WHO. 2002. Genomics and World Health: Report of the Advisory Committee on Health Research. Geneva: WHO.