ABSTRACT

This empirical qualitative study aims (1) to understand the Chinese context in promoting accessible high-quality education for deaf communities and (2) to create an opportunity for deaf experts to contribute to sign language research, instruction, interpreting programmes, and deaf education in China. Using a focus group methodology, we gathered data from 48 participants from four different stakeholder groups (10 teachers, 16 administrators/researchers, 6 interpreters, 16 community members) identifying concerns and solutions to achieving educational access. Video recorded discussions were transcribed, analysed and consolidated into themes. Results show a fragile trust between deaf and hearing professionals, a need for continued investigation on sign language standardisation and preservation, and a desire for worldwide collaboration and inclusion of deaf and hearing scholars in establishing a deaf university in China. This participatory, community-based research method yielded insights toward improving deaf education and sign language training within Chinese special education and toward the design, implementation and establishment of a future university serving only deaf students in China.

This empirical qualitative study aims to understand the Chinese context in promoting accessible high-quality education for deaf communities and to create an opportunity for deaf experts to contribute to sign language research, instruction, interpreting programmes, and deaf education in China. Using questionnaire and focus group methodologies, we gathered data from a total of 48 participants from four different stakeholder groups in China (10 teachers, 16 administrators/researchers, 6 interpreters, 16 community members) to identify concerns and solutions for achieving educational access. Focus group discussions were analysed through the lens of grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014), extracting initial statements and themes from participants’ verbal statements, and creating memos. This process involves the researchers “deriving a general, abstract theory of process, action, or interaction grounded in the views of participants in a study” (Creswell, Citation2009, p. 13), where the refinement and interrelationships of categories of information are compiled (Charmaz, Citation2006; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014). This participatory, community-based research method yielded insights toward improving deaf education and sign language training within Chinese special education and toward the design, implementation and establishment of a future university serving only deaf students in China.

President Xi Jinping has a vision to revitalise the country with the people’s positive attributes and “hard-working spirit” (Xinhua, Citation2019). Inspired by this, deaf Chinese individuals seek to contribute to society by investigating educational matters and introducing deaf perspectives into the larger academic discourse. “Nothing about us without us” is a tenet extrapolated from the disability empowerment movement (Charlton, Citation1998) reiterating the importance of including “the researched” in the research enterprise (Singleton et al., Citation2014). Through this research study, deaf agency and participation is enabled and has the potential to benefit the developing infrastructure and policy designed to meet educational and social needs of all deaf Chinese individuals. These matters have traditionally been on the shoulders of hearing educational leaders who may have little understanding of the deaf experience. This study aims at bringing together deaf Chinese leaders, teachers and community members along with hearing administrators/researchers to engage and exchange valuable insights related to deaf education and sign language access.

Background

According to the Center for World University Ranking report (Citation2019–Citation2020), China is a rising economic giant with 250 universities in the top 2000 in the world. The dedication to improving education for its 1.4 billion citizens has no doubt been a result of the implementation of the National People’s Congress Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China (1986). This law required all Chinese children, including those with disabilities, to receive nine years of education, including six years of elementary school and three of middle school. With 87 million individuals with disabilities in China, comprising 6% of the Chinese population (China Disabled Persons Federation, Citation2018), the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the protection of Disabled Persons (1990) insisted on a collaborative effort from families, schools and professionals to meet the compulsory education requirement for students with disabilities. By 2004, 80% of 20.57 million deaf and hard of hearing Chinese (compared to 93% of the general population) met the compulsory education requirement compared to only 6% in 1988 (DeCaro & DeCaro, Citation2006).

The World Federation of the Deaf (WFD, Citationn.d.) is a global organisation led by Deaf individuals working to ensure equal rights for over 70 million estimated deaf people worldwide. Their vision promotes the human right to sign language for all deaf people. Included in WFD’s strategic focus is inclusive education through sign languages. Within the Chinese context, the compulsory education and special education policies outlined above place deaf children either in regular education or separate schools for the deaf; even so, the majority of these deaf children will not have formal exposure to a signed language in school. For example, by 2006, Chinese officials had established 600–900 residential deaf schools across the nation. However, the majority of the instructional staff are hearing with no specialised training in deaf education, and the language of instruction is uniformly spoken Chinese with little use of signing (Dingqian et al., Citation2019).

The recommendation for inclusive education by the State Education Commission through the Trial Measures for Arranging Disabled Children and Teenagers in Learning in Regular Classrooms was made in 1994 and aimed at integrating children with disabilities into Chinese society. This implementation was not well received by local teachers, who felt students with disabilities were inadequately placed and incapable of progress (Ellsworth & Zhang, Citation2007). Nonetheless, within 10 years, some 65% of students with disabilities were enrolled in regular education classrooms. Placement decisions for deaf students depended mostly on their speech and hearing skills after experimental speech rehabilitation and training programmes; if they were not on par with their hearing peers, they remained in special education programmes. While no precise data is available on the academic and social outcomes of mainstreamed deaf students, the number of residential deaf schools has declined to 437 in recent years (Ministry of Education, Citation2017). Interpreter availability for mainstreamed deaf students is scarce, raising questions with regard to content access and exposure to fluent language models.

Higher education, therefore, remains inaccessible to most deaf students due to them not passing the “gaokao,” a ten-hour long test lasting 3 days. This national test determines university eligibility and selection. In 2014, the Ministry of Education provided accommodations to deaf students by allowing the use of hearing aids, providing extended time, and giving permission to be exempted from the aural section of English exams during the gaokao examinations (Shuo, Citation2018). Sign language accommodations are non-existent for deaf test takers. With so few college-bound students, 25 special education universities in the late 1990s were built to ensure that individuals with disabilities receive tertiary vocational training (Dingqian et al., Citation2019). Tertiary majors for deaf students typically include computer applications, animation, horticulture/gardening, weaving, photography, farming, sewing, woodworking, leather making, food processing, and art (Dingqian et al., Citation2019). No social science, mathematics or economics courses are available to deaf students.

While education is a common right for all Chinese citizens, the incorporation of sign language in general instruction may be downplayed by educational policy makers. Including sign language in deaf education is a shared value for many deaf citizens globally (WFD, n.d.), but initiating this approach within the Chinese context will require a concurrent focus on scaling up sign language instruction for hearing individuals who take primary responsibility in the delivery of deaf education. The academic infrastructure to support these dual tracks (sign language in deaf education and sign language education for educators of the deaf) is presently undeveloped, even though Lytle et al. (Citation2005) made strong recommendations regarding such an infrastructure. Understanding communication and educational accessibility in contemporary China and exploring how programmes could be implemented to achieve similar progress to that made by so many deaf individuals worldwide is the objective of this study.

Deaf education teacher preparation in China

Unlike the specialised deaf education teacher training provided in some countries, special education teacher certification in China covers all disabilities (Deng & Harris, Citation2008). With a dearth of special education training, so-called “qualified” general education teachers are often asked to teach deaf students (Education Law of the People’s Republic of China, Citation1999; Teachers’ Law of the People’s Republic of China, Citation1999). In 2018, of all 9,160,800 Chinese “qualified” teachers, none had training in special education (Dingqian et al., Citation2019). The Special Education Promotion Plan/Enhancement Program of 2014–2016 aimed at popularising the special education field by strengthening the quality and availability of teaching and learning courses. No mention of sign language proficiency requirements for teachers are in place to work with deaf children in China. According to Liu et al. (Citation2013), 73% of teachers of deaf students report that they learned to sign from their students, from colleagues, and from school staff, but not from their university training (Jones, Citation2013). This raises questions about the effectiveness of content delivery without formal sign language training for educators.

The standardisation of Putonghua as a national unified language of instruction across schools in China primarily accommodates the majority Han community. For sign language users, however, standardisation efforts were not based on natural signing used by the deaf; rather, a “signed Putonghua” was developed. In 1987, the official/national Chinese Sign Language (CSL) “Yellow Book” was published by the China Deaf Association in Beijing, with revisions added in 2003. This work aligned the spoken language with certain “equivalent” signs. This initiative brought about drastic linguistic and social challenges for the following reasons: (1) the Yellow Book’s lexical signs were not understood by the majority of deaf Chinese communities (Xiao et al., Citation2015); (2) as illustrated in , there is much diversity of regional sign languages throughout China (Fischer & Gong, Citation2010); and (3) even with the Yellow Book’s availability, deaf children with hearing families still experience language delays and little contact with signing language models.

To evaluate the Yellow Book dictionary and its effectiveness, in Citation2014 a survey was sent out by the National Centre for Sign Language and Braille to 949 Chinese Deaf adults and 2,709 stakeholders. The results showed that 68% of deaf adults did not find sign selections from the Yellow Book helpful, whether the signs were regional or invented, but instead found them confusing. Nonetheless, 63% of deaf adults and 85% of hearing teachers of the deaf expressed support for a national CSL that followed the Chinese written language. As a result of this survey, a taskforce was set up that included a majority of deaf signers, outnumbering hearing committee members. The task force revised the Yellow Book to produce a national dictionary titled “Lexicon of Common Expressions in Chinese National Sign Language” published in 2018, by the China Disabled Persons’ Federation, Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. About 80% of the Yellow Book was revised by the task force, bringing CSL one step closer to a standardisation based on natural sign languages used by Chinese deaf communities. However, learning a sign language requires much more than learning vocabulary or simple phrases; learners must experience the full embodiment of sign language phonology, morphology, syntax and discourse within a well-designed sign language curriculum.

Sign language research, teaching and the interpreter industry

Scholarship in sign language from other countries is providing new platforms for developing and publishing Chinese sign linguistics textbooks. Two textbooks that focused on grammatical structures in natural CSL were published in 2015 by two hearing scholars (Chen, Citation2015; Ni, Citation2015). These linguistic advancements are yet to be officially incorporated within any interpreter or teacher training curriculum.

The interpreting field emerged in China around 2004 with some small training programmes in various regions (Zhengzhou, Nanjing, Yingkou, and Hangzhou), prompting 212 television stations to provide signed TV news for deaf communities across China (Xiao & Yu, Citation2009). While this exciting media initiative appears to raise society’s awareness about sign language and provides deaf students with access to daily news, the signed translation outcomes have, unfortunately, been a huge disappointment to the vast majority of deaf viewers. Most were unable to understand the signed message (Xiao et al., Citation2015; Xiao & Yu, Citation2009). This inability is not due to cognitive limitations of deaf viewers, but rather the syntactic and morphemic distortions of Signed Chinese. Upon graduation from the universities that provide small sign language training programmes, new sign language interpreters realised that they were not being understood by local deaf communities (M. Meng, personal communication, August 17, 2017). Conversely, deaf community viewers began to doubt the validity of their own natural sign language since it was completely different from the signing used by the TV interpreters/signers. Initiatives have been submitted to the government to improve natural CSL proficiency in interpreters in order to enhance the Chinese TV experience of deaf viewers (Xiao et al., Citation2015).

DeCaro and DeCaro (Citation2006) completed a report for the China Disabled Persons Federation that was based on interviews with administrators, teachers, faculty, and community members. The report identified eight recommended areas of improvement: (1) Improve the quality of education, (2) Diversify majors for deaf students, (3) Create access to mainstream courses/programmes, (4) Improve college education, (5) Establish partnerships with employers, (6) Increase opportunities for student leadership development, (7) Improve communication competencies and, lastly, (8) Work to change perceptions regarding deaf persons.

The present study gathers current insights by deaf and hearing Chinese participants who have expertise in sign language research, instruction, interpreter training programmes, and deaf education. These results reiterate the importance of including Chinese deaf experts in policy, design, and implementation decisions. These experts can point us toward the ultimate objective of founding a Deaf University to serve the Chinese deaf community.

Authors’ positionality

The authors’ positionality statement is a reminder of the importance of transparency in research by and with deaf people. This statement is also a reiteration that being deaf does not interfere with the planning or execution of a research study, or with data analysis and interpretation of results. This point is particularly important in China, where deaf researchers are scarce. The authors of this paper are: (1) Jones, a deaf researcher and professor at an American university who has visited China extensively over 13 years to study Chinese deaf education, (2) Ni, a deaf CSL instructor involved with advocacy and interpreter training work in China, and (3) Wang, a deaf Chinese community services director who is involved in setting up video relay services for deaf people in China. All team members were involved in developing and translating questions for the questionnaire and focus group discussions. We collaborated on transcript translation and verification and writing up the manuscript.

Method

This study was initiated in August 2016 and completed in the summer of 2019. The study adopts a community-based participatory research paradigm to “equitably involve community members, organisational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process in which all partners contribute expertise and share in decision making and ownership” (Israel et al., Citation2005). The study was initiated as a result of a community discussion prior to a Language and Deaf Education conference where individuals expressed a need to document deaf and hearing perspectives about deaf education, sign language access and the establishment of a deaf university. The authors proceeded with the implementation and planning of the study through WeChat and video-conferencing. The authors also met to review the questions and its translations. Data was collected from focus group discussions. The analysis and interpretations of findings were shared with the team in both Chinese and English.

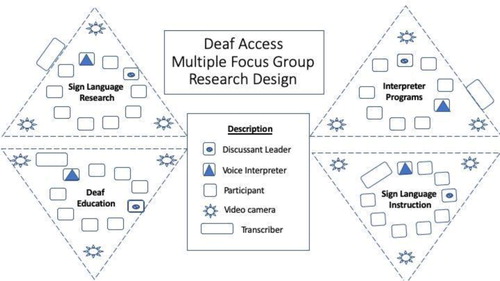

Focus groups were conducted in natural CSL, which allowed deaf professionals to easily engage in academic discussions. Prior to a planned national conference on Sign Language and Deaf Education, 200 invitations were sent to registrants via email asking them to volunteer for the focus group of their choice. A two-hour time slot was allotted for the four concurrent focus group sessions respectively regarding sign language research, sign language instruction, interpreter training programmes, and deaf education. With the approval of the Institutional Review Board from University of California, San Diego, the night before the conference informed consent documents and permission to videotape forms were explained and distributed to all participants. For video identification purposes, upon registering participants received a coloured wristband to represent their profession or status: researcher/ administrator (green), teacher (blue), interpreter (light purple), or community member (burgundy).

Participants, research set-up, and protocol

Forty-eight participants (23 females, 25 males) were involved in this study. In this pool were 29 deaf professionals/paraprofessionals and 19 hearing professionals. Together, these groups of professionals consisted of 6 interpreters, 10 teachers, 16 administrators/researchers and 16 deaf community members. The groups were organised following the topics of sign language research (n=17), sign language instruction (n = 9), interpreter training programmes (n=10), and deaf education (n=12). Three cameras were set up for each focus group to record all signing spaces. A circular arrangement of chairs enabled visual access for all participants. A bilingual voice interpreter was provided for those participants who were not fluent in CSL. A hearing real-time typist transcribed verbatim what the bilingual voice interpreter translated from CSL into spoken Chinese (see ). Each group had a deaf discussion leader who was responsible for facilitating discussion around a set of guiding questions related to past, present and future research in their field; the quality of education; the role of Chinese regional and national sign languages; and barriers and solutions (see ). The following questions were used across all stakeholder groups:

What are the issues and challenges in sign language research, instruction, interpreter training, and deaf education?

What are your views on best practices to ensure sign language and education access?

Table 1. Research questions provided to each focus group.

Table 2. Example of North and South SL lexical and syntactical differences. Image use permission and copyrighted.

The translation process included stages where deaf research assistants transcribed the signed comments into written Chinese, then a trilingual author triangulated the three Chinese translation sources to ensure accuracy and validation. The translation sources consisted of CSL to written Chinese; spoken Chinese recorded from the voice interpreter onsite, and verbatim typed transcripts completed on site. Bilingual research assistants worked with the authors to create an English text translation of the Chinese sources. Areas of uncertainty, especially concerning variation in regional signs, were re-evaluated by the team before a final transcript was produced.

Analysis of data

Transcripts were initially coded following the principles of the grounded theory approach, where statements were analysed and themes extracted (Holton, Citation2007). To make the study more inclusive and accessible to the collaborative team, the analysis was conducted in both Chinese and English. After summarising themes, an across-group analysis was performed to find the most common overarching themes. Once all individual groups had been coded, the within-group themes were brought together in categories to be analysed across groups. presents a coding sample with thematic coding for the Deaf Education Focus Group. We synthesised the within- and across-group themes. Four themes were identified within groups and across groups and are discussed in the following sections.

Table 3. Deaf Education Focus Group Coding sample.

Results

The results were compiled into two sections regarding within- and across-group themes. Each focus group presented its case from the perspective of its field, addressing issues of sign language access, quality and education and reiterating how these themes share a larger framework for a stronger collaborative enterprise. In the following sections, for each focus group category findings are summarised, and themes extracted from each of the four focus groups are described.

Within-groups themes

Sign language research

Data analysis revealed the following themes from the sign language research focus group: (1) a growing awareness of Chinese sign linguistics research; (2) a conflicting focus of research in national CSL versus natural/regional CSL; and (3) research ownership and exchange of knowledge. Each of these themes is discussed in more detail below. The deaf participants’ discovery of sign linguistics as an academic subject catalysed their passion to pursue this field. One participant expressed the transformative experience of this realisation:

We learned Signed Chinese was not good and that natural sign language is authentic. My first thought was that natural sign language lacked detail, but the foreign experts in sign linguistics, who came to our seminar, emphasized that natural sign language is rich in grammatical features. I had no idea, but the good news made me realize I needed to study Chinese sign linguistics. (SL Instructor, Deaf, male)

Hearing researchers do all the sign linguistic research, but lack language competency. They know the theory of linguistics, but not what is unique to natural CSL. They take ASL research and apply it to CSL. Hearing researchers discover a few examples but don’t know there is much more. For example, they found a few classifiers for “car.” There are 6 different ways of demonstrating a “car” classifier. They didn’t know how many handshapes existed in CSL; ASL has 40 handshapes, but here in China we have 110 handshapes. We, deaf researchers, know this. We need to generate our own research and not wait to borrow from Western countries. (Researcher, Deaf, male)

Sign language instruction

It is noteworthy that according to the sign language instruction focus group, sign language instruction targets hearing interpreters and/or teachers who are learning sign language as a second language. An analysis of data gathered from participants in this group yielded two themes: (1) a lack of clarity with regard to which CSL to use for instruction; and (2) a lack of national standards for CSL instructor qualifications.

The first theme stems from the challenge of not having a standardised natural CSL. No unified CSL instructional resources or curriculum exist. One hearing participant raised the following question: “What is CSL? Is it the Yellow Book or is it the natural/regional sign language?” Another hearing participant stated, “CSL is not just the Yellow Book; it includes the unified and local SL.”

The second theme addressed the lack of national standards in CSL in two contexts: standards for sign language teachers (i.e. qualifications or mastery credentials) and learning outcomes or progress levels for students learning to sign. The qualifications and identity of the instructor was an issue for participants:

A hearing instructor’s quality of sign may not be as good as a deaf instructor, but he or she would know the theory of language. A deaf instructor, however, may be fluent in sign language, but would not necessarily have the (theoretical) foundations, nor would he or she have adequate materials to teach. (Instructor, Hearing, Female)

Differing viewpoints on the role of spoken language in a sign language course were addressed. Hearing participants rely on spoken Chinese to understand a deaf instructor’s signing. In countries where formal learning of sign language as a second language is commonplace, immersive language learning is the standard model (Rosen, Citation2010). In fact, many sign language teachers follow a “voice-off” policy. But our participants held steadfastly to their belief that hearing students would not thrive in this kind of immersive sign learning environment. This suggests that second language pedagogical research in China is important, as cultural contexts may differ and warrant a certain instructional approach. The problem is compounded by the fact that there is no formal sign language instructor training programme in China. One deaf participant wished to hone his language teaching skills by completing a CSL teaching specialisation degree. In lieu of formal training, online sharing has become a platform for knowledge exchange. All of the focus group participants agreed to advocate for national CSL proficiency and mastery guidelines for sign language instructors that are similar to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), but tailored to fit the Chinese context.

Another issue identified by participants was the need for a shared curriculum that outlines mastery objectives for sign language learners. What specific sign language skills are expected after one year of CSL instruction? According to this participant, visual vernacular is the foundation of all sign languages:

We need visual vernacular before learning signs. Facial expressions are important. Many interpreters have no facial expressions when they graduate, and they are stuck with signing character for character. When they go out to the deaf communities, we deaf people don’t understand them. (Instructor, Deaf, Male)

Interpreter training programmes

Regarding the interpreter training programme focus group, the following themes were identified: (1) the qualifications of interpreter trainers/teachers, (2) opportunities for professional practice; and (3) the desire for the government to cover the cost of interpreting services at a professional wage.

The participants had conflicting views about teacher qualifications for interpreter training programmes. Deaf participants asserted that deaf instructors are the best teachers, whereas hearing participants valued interpreter trainers with a high level of teaching or interpreting experience. Having community experience and being an excellent sign language model were considered assets in the interpreting field.

As mentioned in another focus group, hearing teachers instructing in Signed Chinese, the purported national standard, are favoured by hearing participants but not by deaf participants. As one female hearing interpreter claimed, hearing teachers would qualify before deaf instructors because of a preferred order to the sign language acquisition process, which is more suitable to a hearing instructor: “In our program, we teach vocabulary, conversation, formal sign language [Signed Chinese], and then natural sign language.” Another hearing female interpreter participant believed mastery of natural sign language was not required for interpreters, but was an optional skill: “Interpreters don’t need to know natural sign language; they can interpret based on the individual’s needs. They are to transcribe into Signed Chinese and if necessary, local sign languages.”

Interpreters in the focus group thought deaf-related conferences were an excellent venue to enhance signing and voicing skills. The speed and heavy content knowledge required by these conferences mean skilled interpreters are needed to keep up, but unfortunately the number of qualified interpreters in China is miniscule. Sign language interpreter salaries in China are extremely low and sometimes non-existent, making the job market undesirable.

Deaf education

In the deaf education group, the following themes were addressed: (1) a lack of language role models for curriculum delivery; (2) a lack of professional training and deaf education resources, and qualifications of school teachers, and (3) a lack of access to higher education for deaf students.

Sign language proficiency in content pedagogy, delivery, and teacher qualifications is of concern, as one deaf participant summarised:

The main challenges currently are (1) limited number of majors, (2) deaf people cannot hear, and (3) there are no deaf teachers in colleges. There are very few qualified sign language interpreters and professional sign language training institutions. Teachers water down the content and do not translate effectively. There are very few deaf teachers, which leads to mental health issues in deaf students because deaf students need communication. I studied in America and was impressed with the number of professionals, teachers and students, all signing everywhere, in the classrooms and in hallways. (Professor, Deaf, Female)

According to a female deaf educator, “the important role of sign language in learning written Chinese is deemed to be the solution … learning Signed Chinese will positively affect the learning of Chinese. We teach the deaf because we think it can raise their literacy skills.” Standards for teacher qualifications rely heavily upon using best practices in teaching, in which deaf individuals have no formal training and are seen as lacking professional expertise. A hearing administrator stated the following:

We can’t hire more than one deaf teacher; we have to wait until the educational policies change. It takes at least 10 years. Deaf teachers at American universities and schools are numerous. In China, it is difficult to make this happen … First, we, as hearing administrators, need to learn on our own how to use the resources effectively. Second, school principals need to include deaf teachers in schools. We need these two steps to launch the third step without obstacles. (Administrator, Hearing, Female)

We need fluent signing deaf teachers as role models for students. There are hardly any deaf students enrolled in special education. I’ve seen some incompetent deaf teachers pedagogically; administrators don’t hire deaf individuals as teachers. The pool of applicants consists of fluent signing deaf individuals whose [written] Chinese is poor, and we have hearing students fluent in written Chinese, but they are poor in CSL. I believe natural sign language and [written] Chinese are equally important skills for a teacher to have. (Educator, Deaf, Female)

Across-group themes

Having summarised the themes within focus groups, this section of the paper addresses shared themes across groups with a view to the current situation and moving forward to an improved platform for a future deaf university. The following common themes were drawn from within focus groups and shared across groups: (a) deaf and hearing collaboration, trust and ownership; (b) involving deaf communities in sign language standardisation and regional sign language research through tertiary education; and (c) research and training of professionals using outside resources to solve local challenges.

Deaf and hearing collaborations between professionals to strengthen trust and ownership of services

In synthesising and interpreting the underlying themes, we identified issues of trust between deaf and hearing professionals that lie in longstanding cultural misconceptions of what is possible for deaf children (Yang, Citation2006). Historically, deaf individuals were destined to complete only manual labour training in vocationally oriented tracks. Ironically, sign language research is suitable for deaf individuals who wish to become sign linguists, but opportunities to enroll in higher education are not available. Without accessible teacher training programmes for deaf people and without sign language proficiency among hearing teachers and interpreters, how can deaf professionals achieve the level of trust required for collaboration with hearing professionals? Deaf Chinese people often assume that hearing people know more regarding academic content knowledge and pedagogical theory. At the same time, deaf people carry self-doubt about their own rich sign language and even in their own intellectual abilities. The issue of trusting non-signing hearing professionals was raised by a deaf participant, who questioned whether a hearing researcher could investigate a language they do not use or understand and be viewed as a field expert. This argument raises issues regarding qualifications. Without a well-founded sign linguistic training course in higher education, hearing professionals will not master sign expertise nor gain practical experience in the language.

Involving deaf communities in standardization and regional sign

Language research through tertiary education

The frequent discussions about sign language standardisation versus regional sign languages requires the time and place to critically evaluate the fields of sign language research and instruction, and the language of instruction in deaf education. Accessible tertiary education for deaf learners is a stepping stone toward enhanced sign language research and instruction, and deaf education. The tension between establishing a national/natural CSL and preserving regional sign languages also involves the need to provide a language-rich environment for deaf students with an available sign language (see Disabled Persons Federation and China Association for the Deaf and hard of hearing, Citation2003; Yang, Citation2011). A standardisation process needs a commitment to a dynamic language environment in which multiple ways of signing are respected, and teachers, interpreters, and students constantly work to achieve comprehensible input and output? As the focus group discussions revealed, hearing and deaf participants are keen on preserving and maintaining both a common natural sign language across China and the regional dialects.

Training of professionals: outside mentoring but Inside problem solving

The issues of training and resources were raised in all focus groups. The hearing and deaf participants who had study-abroad experiences benefited from professional development for research, sign linguistics, standardisation guidelines, interpreter expertise and bilingual deaf programme development. The participants referred to European models. The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR, Citation2020) is a promising model that has provided support to a wide range of European sign languages. Whether or not it is possible to preserve regional sign languages alongside a standardised CSL, issues remain regarding the efficiency of service systems which can provide interpreters who can communicate with deaf communities in hospitals, universities, and the public sector. Many of the recommendations by stakeholders included soliciting the assistance of deaf expertise from abroad through lectures, conferences and textbooks. By using outside resources and expertise, the Chinese are more attuned to their historical and situational challenges. Deaf Chinese people are ready to contribute problem-solving strategies, but several participants shared that deaf people face challenges to being included in the national discourse surrounding sign language, deaf education, and interpreter training and provision.

Recommendations for a deaf Chinese university

An additional survey was sent out to all participants prior to the focus groups, which will not be fully examined due to the scope of this paper, included one question related to establishing a national deaf university. A majority of survey respondents (44 out of 48) called for deaf experts from around the world to participate in infrastructure and curriculum design, and in ensuring the accessibility of visual resources and services, and instruction and evaluation services that will assist in coordinating this national effort. The following is a list of recommendations from our stakeholders regarding the structure of a national bilingual Chinese deaf university:

A centralised Chinese Sign Linguistics centre where both national and regional sign languages are valued.

An academic think tank where issues, concerns, and problem-solving strategies are shared and implemented through a modelling approach, or on an experimental basis.

A research and dissemination centre focusing on deaf education, interpreter training, and sign language research across all regions of China.

A rigorous academic and research-focused education where visual learning is the mode of knowledge exchange.

Study-abroad opportunities for deaf students to further learn sign linguistics, deaf culture, and sign language and educational research methods.

Bilingual teacher training programme to attain language and content competency for elementary and secondary school instruction.

Discussion

In the context of China, recognising cultural and linguistic diversity within deaf communities is necessary in order to develop a high-quality and sustainable sign language-based infrastructure. The diversity of deaf communities is embodied through alternative ways of experiencing language, culture, and cognition through visual channels (Holcomb, Citation2010).

From the findings of the focus group discussions in this study, it is clear that deaf individuals in China do not receive an adequate education, nor do they have access to qualified teachers and interpreters, a language-rich content curriculum, deaf role models, or higher education (see Yang, Citation2011). The recruitment of deaf professionals for these fields requires access, time, trust, and training. Investing in CODAs as experienced interpreters will enhance communication and strengthen trust between deaf and hearing professionals. Investing in tertiary education that is accessible to deaf students will enable them to critically engage with colleagues in designing best practices.

Deaf expertise has yet to be fully realised in China. Without educational, social, or employment opportunities, or a platform to exhibit the cultural and linguistic wealth of deaf citizens, their expertise remains hidden to the public (Yosso, Citation2005). The involvement of deaf communities in building a deaf university will build confidence in deaf people’s own funds of knowledge and contributions. The opporutunities for contributions would stimulate reflective intellectual discourse which are needed especially given the fact that Deaf Chinese individuals display a lack of critical thinking styles (see Cheng et al., Citation2014). By filling teaching and administrative positions, deaf Chinese community members will construct a larger cohesive deaf ecosystem. In other parts of the world such as the United States and Europe, research on sign linguistics, deaf culture, deaf history, deaf bilingual education and interpreter education is led in part by deaf scholars. Interactions with deaf role models will strengthen deaf students’ language skills and cognitive development. History shows us that when deaf people share their unique knowledge, experience, and expertise, advances are made in terms of sign language proficiency guidelines, sign linguistics research, bilingual teacher instructional strategies, and signed literature and poetry (Andrews et al., Citation2015; Bauman & Murray, Citation2010; Kusters et al., Citation2017).

Establishing cross-cultural exchanges of expertise between deaf and hearing communities does not come without resistance or ambivalence. For successful collaboration to occur, it first requires building levels of cognitive-based trust as well as affect-based trust. Cognitive-based trust is the “confidence built on perception of other’s reliability and competence” (Chua et al., Citation2012). Affect-based trust is the ability to allow oneself to be vulnerable to sharing mutual connections without being judged or taken advantage of. Hearing individuals need to trust deaf people’s sign language knowledge and contributions on an intellectual level. Investing in deaf researchers in sign linguistics increases the reliability, generalizability, and application of ethical principles in research with deaf scholars (Kusters et al., Citation2017).

Sign language standardisation and dictionary work are ongoing challenges faced by other Asian countries (e.g. Indonesia, India, Cambodia, Nepal). In these contexts, sign language work must benefit deaf communities by protecting and preserving regional sign languages (Moriarty Harrelson, Citation2019; Palfreyman, Citation2019). Article 21 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities refers to involving organisations of deaf people who are actively consulted in issues concerning their lives, including their native languages. Each country has unique challenges, and therefore it is wise to evaluate language ideologies on a case by case basis. Recommendations to improve training and qualifications for teachers and interpreters can be met by training deaf instructors of sign linguistics and pedagogy, and by including deaf Chinese scholars in the planning and development of research and education for deaf individuals. The establishment of a deaf university as a central headquarters for research and training can make these initiatives a reality.

This study’s relatively small sample size indicates the need for more studies with a larger, nation-wide sample population. A demographic analysis could better account for diverse socio-economic statuses and regional or urban/rural population factors. Including both deaf and hearing professionals in this research endeavour will allow for a balanced perspective in determining the steps for future policy decisions. In the focus groups in this study, two-hour discussions could not adequately cover the depth and breadth of current issues. For example, the groups’ discussion of deaf education focused only on the tertiary level and did not address deaf education from an early age. Therefore, more focus groups in specialised educational settings are recommended.

Conclusion

A unified yet diverse Chinese deaf community can be a source of strength for the nation while contributing to a cohesive, industrious and collaborative enterprise to produce materials and infrastructure for the people. A cross-cultural collaboration between hearing teachers and deaf sign language experts will enable knowledge exchange. Further research on this collaboration and the impact of deaf communities’ involvement in professional development will enhance university contexts and other professional venues.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Ailong Love Deaf Association for providing the space to set up the focus groups during the conference, the Yantai volunteers for typing verbatim the focus groups, to David Huang, Qi Chen, Fanfan Li, Lihuan Zhou for their Chinese/English translation services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gabrielle A. Jones

Gabrielle A. Jones, Assistant Professor in Education Studies, University of California San Diego, Director of the MA-ASL programme, a bilingual teacher credential programme. Formerly an elementary and middle school teacher of the deaf, she mentored in-service and pre-service teachers. Her PhD studies at the University of Illinois in Educational Psychology in Cognitive Science, Teaching and Learning involved doing research investigating Chinese reading instruction in deaf classrooms and how teachers map language to print. She published in the area of Chinese Deaf sociocultural learning, Chinese Deaf Teachers and research ethics. Currently a visiting professor at the ZhongzhouUniversity of Engineering and Technology since 2018.

Dawei Ni

Dawei Ni, born in Qingtian, China, is currently a Lecturer in Sign Language Linguistics and Interpreting at the University of Applied Sciences in Landshut Hochshule, Germany. He completed two Masters in Social Work in Vienna, Austria and in Sign Linguistics in Hamburg, Germany. He has done extensive interpreting and advocacy work in Austria, Germany, Indonesia, Switzerland and China related to sign languages including Chinese Sign language, interpreting, Deaf culture and sign linguistics.

Wei Wang

Wei Wang, born in Beijing, China, formerly the Director of Video Production Centre for Hand Voice Information Technology in Zhuzhou for three years, helping with establishing Video Phone relay services to the Deaf in China and distributing educational news to the Chinese online platform. Graduated from American University gaining a Masters in Producing for Film and video and a Masters of Fine Arts in Film and Electronic Media. She worked for Visual Language and Visual Learning (VL2) a Scientific Centre of Learning at Gallaudet University in Washington D.C as a media specialist for seven years.

References

- Andrews, J., Byrne, A., & Clark, D. (2015). Deaf scholars on reading: A historical review of 40 years of dissertation research (1973–2013): Implications for research and practice. American Annals of the Deaf, 159(5), 393–418. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2015.0001

- Bauman, H.-D., & Murray, J. J. (2010). Deaf studies in the 21st Century: ‘Deaf-gain’ and the future of human diversity. In M. Marshark & P. E. Spencer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education (pp. 210–225). Oxford University Press.

- Centre for World University Ranking Report. (2019–2020). https://cwur.org/2019-2020.php

- Charlton, J. (1998). Nothing about us without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. University of California Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pnqn9

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Chen, X. (2015). Zhonguo Shouyu Dongci ji Leibiaoji Jiegou Fangxiaoxing Yanjiu [A study of Directional Verbs and Classifier Construction in CSL]. Hunan People's Education Press.

- Cheng, S., Zhang, L. F., & Hu, X. (2014). Thinking Styles and university self-Efficacy Among deaf, hard-of-hearing, and hearing students. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 21(1), 44–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/env032

- China Disabled Persons’ Federation, Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. (2018). Lexicon of common expressions in Chinese national SL. Huaxia Press.

- Chua, R., Morris, M., & Mor, S. (2012). Collaborating Across Cultures: Cultural Metacognition & Affect-Based Trust in Creative Collaboration Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1861054

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications.

- Council of Europe. (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing. https://www.coe.int/lang-cefr

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- DeCaro, P., & DeCaro, J. (2006). Postsecondary education for deaf people in China: Issue, roles, responsibilities and recommendations. Report to the China Disabled Persons Federation. https://www.pen.ntid.rit.edu/pdf/chinarpt06.pdf

- Deng, M., & Harris, K. (2008). Meeting the needs of students with disabilities in general education classrooms in China. Teacher and Special Education, 31(3), 195–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406408330631

- Dingqian, G., Ying, L., & Xirong, H. (2019). Deaf education and the use of sign language in Mainland China. In H. Knoors, M. Brons, & M. Marschark (Eds.), Deaf education beyond the western world: Context, challenges and prospects (pp. 285–306). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190880514.001.0001

- Disabled Persons Federation and China Association for the Deaf and hard of hearing. (2003). Chinese sign language (3rd ed.). Huaxia Publishing House.

- Education Law of the People’s Republic of China. (1999). Chinese Education and Society, 32(3), 19–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932320319

- Ellsworth, N., & Zhang, C. (2007). Progress and challenges in China’s special education development: Observations, reflections, and recommendations. Remedial and Special Education, 28(1), 58–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325070280010601

- Fischer, S., & Gong, Q. (2010). Variation in East Asian SL structures. In D. Brentari (Ed.), Sign languages: A Cambridge Language Survey (pp. 499–518). Cambridge University Press.

- Holcomb, T. (2010). Deaf Epistemology: The deaf way of knowing. American Annals of the Deaf, 154(5), 471–478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.0.0116

- Holton, J. A. (2007). The Coding process and Its challenges. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage handbook of grounded theory (pp. 265–289). Sage Publications.

- Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J., & Parker, E. A. (2005). Methods in community-based participatory research for health. Jossey-Bass.

- Jones, G. A. (2013). A cross-cultural and cross-linguistic analysis of deaf reading practices in China: Case studies using teacher interviews and classroom observations. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign]. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/44319/Gabrielle_Jones.pdf

- Kusters, A. M. J., De Meulder, M., & O'Brien, D. (Eds.). (2017). Innovations in deaf studies: The role of deaf scholars. Oxford University Press.

- Liu, Y., Gu, D., Cheng, L., & Wei, D. (2013). Survey of SL use in China. Applied Linguistics, 2, 28–32.

- Lytle, R. R., Johnson, K. E., & Hui, Y. J. (2005). Deaf education in China: History, current issues, and emerging deaf voices. American Annals of the Deaf, 150(5), 457–469. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2006.0009

- Ministry of Education. (2017). Curriculum program for compulsory education in deaf schools. http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/cmsmedia/image//UserFiles/File/2008/04/28/2008042821/2008042821_785324.doc

- Moriarty Harrelson, E. (2019). Deaf people with “no language”: Mobility and flexible accumulation in languaging practices of deaf people in Cambodia. Applied Linguistics Review, 10(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0081

- National Centre for Sign Language and Braille. (2014). The use of SL and braille in China. Commercial Press.

- Ni, L. (2015). Study of Verbs in CSL. Shanghai University Press.

- Palfreyman, N. (2019). Variation in Indonesian sign language. A typological and sociolinguistic analysis. De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501504822

- Peng, Z. (2018). What is CSL? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oA6enRyzv9A

- Rosen, R. S. (2010). American sign language curricula: A review. Sign Language Studies, 10(3), 348–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/sls.0.0050

- Shuo, Z. (2018, June 7). Changes help more disabled students to take the gaokao. China Daily. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201806/07/WS5b188768a31001b82571e9b2.html

- Singleton, J. L., Jones, G. A., & Hanumantha, S. (2014). Toward ethical research practice with deaf participants. Journal Empirical Research Human Research Ethics, 9(3), 59–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264614540589

- Teachers’ Law of the People’s Republic of China. (1999). Chinese Education and Society, 32(3), 19–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932320319

- World Federation of the Deaf. (n.d.). https://wfdeaf.org

- Xiao, X., Chen, X., & Palmer, J. (2015). Chinese deaf viewers comprehension of SL interpreting on television. Interpreting, 17(1), 91–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.171.1.05xia

- Xiao, X., & Yu, R. (2009). Survey on SL interpreting in China. Interpreting, 11(2), 137–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.11.2.03xia

- Xinhua. (2019, March 19). Xi stresses ideological and political education in schools. http://www.china.org.cn/china/2019-03/19/content_74586886.htm.

- Yang, J. H. (2006). Deaf teachers in China: Their perceptions regarding their roles and the barriers they face. [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Gallaudet University].

- Yang, J. H. (2011). Social situations and the education of deaf children in China. In G. Mathur & D. J. Napoli (Eds.), Deaf around the world: The impact of language (pp. 467–486). Cambridge University Press.

- Yosso, T. A. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1361332052000341006

- Zheng, P. (2018). What is CSL? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oA6enRyzv9A.