SARS-CoV-2- achieved what climate change science and advocacy have not been able to achieve in more than 30 years, i.e. since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was founded in 1988: profound, system-relevant changes were possible in timeframes of days to weeks only. Total global annual Carbon Dioxide (CO2) emissions dropped by about 6% in 2020 as compared to 2019 (IEA, Citation2021). Initial projections even estimated a fall of 8% (IEA, Citation2020), which would have been roughly in line with a pathway to a 1.5 degree Celsius world, if drops in emissions at this scale occurred every year this decade (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Citation2018). This is daunting and frightening, as it shows us how drastic the cuts need to be to safeguard a future in line with the 1.5 degree Celsius target (IPCC, Citation2018), and how far away we are from this goal. The challenges we face to safeguard the world are enormous.

In this essay I argue that COVID-19 is the largest chance that humanity has (had) over the last roughly 30 years to solve the climate crisis. There is a window of opportunity. But it closes fast. The decline in global CO2 emissions in 2020 was mainly due to a fall in transport and the acceleration of the decarbonisation of the power sector. Transport activity will revive. Moreover, initial projection and current data of annual CO2 emissions in 2020 deviate because of the quick recovery of economic activity at the end of last year, leading to global CO2 emissions being 2% higher in December 2020 than in December 2019 (IEA, Citation2021). Nonetheless, I argue that the chance for mutual benefits of a COVID-19 response and the climate crisis is still high. I lay out how we can, according to my view, lower the risk of both, dangerous climate change and pandemics at the same time.

COVID-19 and the climate crisis are intertwined in multiple ways. First, climate change itself increases the risk for infectious diseases by way of global warming. When global temperatures rise, animals who can migrate poleward can do so in order to stay in their preferred, somewhat cooler temperature range. This increases the contact between animals, carrying a risk of germs finding and settling in new hosts (Bernstein, Citation2020). Climate change has already been associated with the diffusion of vector-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever (Giesen et al., Citation2020) and water-borne diseases like Cholera (Christaki et al., Citation2020). Both are projected to further increase with climate change and global warming in the future (Brubacher et al., Citation2020). Epidemiologists note that unless the climate crisis is addressed, further disease outbreaks are likely (Bernstein, Citation2020).

Second, many of the root causes of climate change also increase the risk of diseases. For example, deforestation. In particular when biomass burning and fire clearing are involved it contributes to climate change by releasing carbon that was previously stored in plant material. Deforestation occurs for agricultural purposes, livestock breeding or raw material extraction, with livestock breeding also risking spillover of infectious diseases from animals to humans. At the same time deforestation and other habitat loss leads to the migration of animals contacting other animals and sharing germs (Bernstein, Citation2020).

Third, as mentioned above, the short-term impacts of COVID-19, mainly the lockdowns implemented in many countries, led to a reduction in economic activity, but also energy use and mobility, causing a drastic decrease of GDP and GHG emissions in the short-term.

Fourth, many responses to COVID-19, e.g. the economic recovery packages adopted in Germany, the US and by the European Union, are to some extent dependent on co-benefits for the environment, for example, when electric and hybrid cars are subsidized or more subsidized than petrol-fueled cars.

Fifth, regarding long-term impacts of COVID-19, it is expected that the pandemic will impact the ways we live and work, produce and consume for some more time (Kissler et al., Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2020). Hence, many response measures taken today will impact and at times determine how we as a society, with our living and working patterns, affect the climate in the future. There is the chance to set in motion a more sustainable path of economic and social development, but also the risk of threatening mitigation achievements and initiating new ways of producing GHG emissions. By regarding both climate and COVID-19 as interdependent features of our social and economic lives today, I’m arguing here that addressing both challenges together is possible and should be the post-COVID-19 mandate for planners and planning educators around the world.

In this essay I argue that we can address both challenges, the climate crisis and the pandemic, jointly by focusing on four policy and planning goals: 1) radically re-GREENing the cities, 2) re-adJUSTing inner cities and office spaces, 3) re-STRUCTURing our neighborhoods, and 4) re-MOVing the transportation systems. These four postulations are based on reflections on the impact of COVID-19 on our socio-economic system and way of life, mainly in cities, and on the need to drastically reduce GHGs emissions to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. I also argue – as mentioned above – that the pandemic offers a turning point to kick-start a sustainable development process in harmony and concordance with nature, with a low risk of diseases, and for a climate-safe, i.e. resilient future.

I will structure this essay around two questions: What does COVID-19 mean for local climate change planning? And how can planners and planning educators use the COVID-19 crisis to help accelerate efforts that combat climate change and the risk of future pandemics? This means that I will start by laying out the short- to medium-term impacts and related policy responses of the COVID-19 crisis on the functioning of cities and economies, and evaluate the effects of those on the climate issue. Subsequently, I will give recommendations for planners and planning educators as to how a policy and planning response could secure a healthy, and climate-safe urban living by focusing on the four postulations mentioned above.

The Short- and Medium-Term Impacts of COVID-19 on Our Ways of Life, Functioning of Cities and Economies

Direct short-term impacts of the crisis are related to the millions of people who caught the virus, were health-wise affected, and/ or died from it. As of 1 April 2021, 127,628,928 cases of COVID-19 (in accordance with the applied case definitions and testing strategies in the affected countries) have been reported since 31 December 2019, including 2,791,055 deaths (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [ECDC], Citation2021). This is in itself a traumatizing social and cultural impact, with significant economic repercussions.

For many people across the globe COVID-19 had the following short-term impacts:

Curfews, shutdowns or lockdowns, quarantines, and similar restrictions had been adopted in many countries (Corbera et al., Citation2020). This included the closure of most public places and recreational venues. At the height of the first wave of the pandemic, in March and April 2020, schools, universities and colleges in 167 countries were closed on a nation-wide basis, affecting 1,467,558,839 learners, i.e. approximately 83.3% of the world’s student population (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], Citation2020). Only essential businesses were allowed to remain open; only minimal movement to doctors and grocery shopping was possible.

The labor market responded with layoffs, reduced working hours or home office policies. The ifo Institute in Munich, for example, calculated that across industries, 50% of companies implemented short-time work in Germany. Among the most hit sectors were restaurants and catering (99% of businesses affected), hotels (97% of businesses affected), automotives (94% of businesses), but also aviation (91%), travel agencies and tour operators (90%), (ifo Institute for Economic Research (ifo), Citation2020). People were restricted to their immediate surroundings, neighborhoods, cities, and towns. Global and regional mobility came to a halt or was hugely reduced, particularly public transport and international flight traffic (Hausler et al., Citation2020). For example, 70–90% fewer people used public transport during the lockdown in German cities. Data from Chinese cities shows that private cars, walking, and biking had gained the most share, while bus and subway ridership declined (Hausler et al., Citation2020). Municipal governments reacted with short-term measures, such as converting street lanes into cycle path and neighborhood streets into playgrounds.

This has had major repercussions for how we work(ed), live(d), and move(d) around with more profound changes the longer the pandemic lasts (Nicola et al., Citation2020). At the beginning of 2021, most countries in the Northern Hemisphere are in the middle of their “third wave” (Kissler et al., Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2020). Possible long-term impacts with relevance to planners and planning educators include:

Political: Experts assume that there is likely to be a retreat from globalization (Haley et al., Citation2020). With that, the roles, power and perception of the State may change profoundly. International differences in handling the crisis may also alter perceptions of experts and the role of science in policymaking. If the crisis shows the limitations of science in dealing with these circumstances, including its uncertainties, a shift to a more democratic and participatory form of governance seems possible (Haley et al., Citation2020).

Social: In parallel, there is a potential move towards more regionalism, more community, and community values, at least in some countries and places. Appreciation for nice immediate surroundings has increased during the lock-down. People experienced the value of (private and public) greenery, amenities, and having services nearby. By that, the pandemic may increase community cohesion. Many people also supported their local pubs, bakeries, etc. that were at risk of bankruptcy (Von Beust, Citation2020). Nonetheless, the crisis is likely to put a further strain on social equality, as higher-income workers are more likely to be able to work remotely. People on lower incomes are less often able to work from home, and may in turn be more affected health-wise or, if ill cannot work. Lower paid and service jobs are usually also less secure. Exposure of the society’s fragility will lead to a greater demand for, and also experiments with, wider social safety nets, such as special grants to families and small business holders (such as in Germany) or calls for universal basic income. In the United Kingdom, a public poll found that during the pandemic 51% of the public supported a universal basic income, with 24% unsupportive, and 9% undecided (Stone, Citation2020).

Economic: Scholars expect a lasting interest and trend towards remote working, with subsequent changes to established working models and related urban forms, e.g. entire business districts of large cities, like London (Schulz, Citation2020) and Frankfurt. With employers realizing at least some (mostly financial) benefits of home working, office space demand in cities and inner cities may go down. Moreover, if tele- or remote working becomes more accepted, those who can afford it will possibly consider moving to the suburbs and the countryside (or will be less likely to consider moving from there back to the cities). With longer but fewer commutes the greener suburbs or even countryside around major cities and towns could see a resurgence (Haley et al., Citation2020; Landry, Citation2020). Such developments could affect the inner cities as centers of commerce, trade and interaction (in particular with the parallel rise of the already well-established trend towards online retailing). For example, in the city of Bocholt/ Germany, where they had 100% occupancy of shops in the city center in 2006, there was a 13% vacancy rate in July 2020 (Book & Müller, Citation2020).

For the city, reduced interest in public transportation, parking, and commercial activity may lead to significant drops in revenue, in turn lowering investments and service provision. With that, reduced public transportation may not only harm the environment, GHG mitigation ambitions, air pollution, and public health, it may also lead to a financial or even urban identity crisis. Cities could be at the beginning of a profound restructuring process or use this moment to initiate such catharsis towards sustainability, climate neutrality and resilience. Before moving on to explain how to seize this opportunity, summarizes key short- and medium-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in cities and their consequences for the climate.

Table 1. Selected short-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in cities, and their relation to climate issues and GHG emissions

What All that Means: Transform the City

In the previous section I laid out how the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent socio-economic changes are likely to profoundly affect the socio-economic way of life and functioning of cities – certainly for dense European cities with their commercial centers and generally a large mix of residential and other land uses directly around it. Could this be the end of the city as we know it? Or can the city be transformed to something new, something better, for the environment, the climate, and urban health?

I believe, the COVID-19 pandemic is not the (start of the) end of the city, but it marks a turning point towards a required restructuring towards more healthy, green, and sustainable urban living – and an unprecedented chance for the city and the climate to work in tandem. As Dan Hill says “I have no fear for the future of cities, as long as people are around. The story of humanity is an urban one, a slow 20,000 year drift towards a largely urban condition. A city does the same thing to individualism that a natural ecosystem does to a tree – thriving there is about living well with people who are not like you. Just as a tree revels in those multifarious interdependencies, so we do with cities” (Hill, Citation2020a). Do we dare to set off on this path? And, how can it be done?

This section elaborates on the four postulations of policy and planning goals, which I believe can jointly support solving the climate crisis and the pandemic: 1) radically re-GREENing the cities, 2) re-adJUSTing inner cities and office spaces, 3) re-STRUCTURing our neighborhoods, and 4) re-MOVing the transportation systems.

Re-GREEN Cities

The most important action point for cities after the pandemic, I believe, is the call for a radical re-GREENing. During the lockdowns, people have experienced the value of space, nature and greenery – though often unevenly distributed, which could risk a resurgence of the suburb and outer metropolitan areas. Inner cities can only compete, if they offer the amenities that people are looking for, e.g. more green space and more space in general and their multiple (co-)benefits (Dushkova & Haase, Citation2020; Raymond et al., Citation2017). Such a renaturalisation of the inner cities would, for example, be supportive for binding carbon (climate change mitigation), for lowering urban heat and the urban heat island (UHI) effects, and for lowering impacts of strong rain events and flooding. It would also reduce particulate matter and air pollution. This in turn would reduce respiratory diseases and help protect against serious outcomes of infections like COVID-19. For example, in a study in the USA it was found that exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 mortality (Wu et al., Citation2020), and other respiratory diseases like pneumonia and influenza (Croft et al., Citation2019; Zhao et al., Citation2019) are connected. Similarly in China, studies found that worse air quality may increase transmission of infections that cause influenza-like illnesses (Tang et al., Citation2018), including coronaviruses (Kan et al., Citation2005).

By a reGREENing strategy focused on the centers of cities and towns, these can create livable, amenable inner areas and tackle health and climate issues at the same time. However, such a reGREENing and decentralization is only valuable for climate mitigation aspirations, when combined with a smart and energy-extensive way of moving around/ transportation (see further below).

Re-adJUST Cities

As outlined above, a likely consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is the reduction of demand for retail and office space in (inner) cities. I here argue to use that moment and convert commercial spaces to housing, where needed, which would reduce the strain on many inner cities and lower burgeoning housing prices. Lower-income residents, in particular young people, who are less at risk from COVID-19 and less worried about crime, could suddenly discover that life in big cities is affordable again (The Economist, Citation2020).

Together with more greenery inner cities would become (more) healthy and amenable living places, mostly for low-income residents and young people. Such a strategy could highlight equity and justice aspirations, serving in particular previously underserved communities (Bernstein, Citation2020).

Re-STRUCTURE Cities

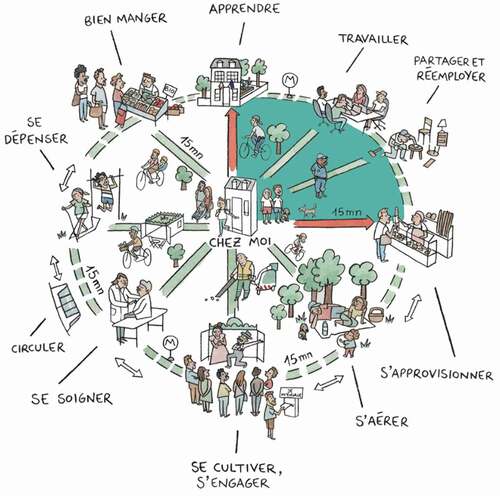

With the developments and actions outlined above, a re-STRUCTURing of previously dense cities becomes likely. The post-pandemic city might change towards a (more) decentralized urban landscape made up of a multitude of nodes, with nodes being self-sufficient neighborhoods or communities. This model is not new, and cities like Berlin/ Germany, Paris/ France, Chengdu/ China (Hill, Citation2020a), Melbourne/ Australia (“20-minute city”), Copenhagen/ Denmark and Utrecht/ Netherlands (Willsher, Citation2020) are noteworthy examples. For example, Berlin, has a neighborhood structure along the so-called “Kiez” vision, with a Kiez being something like a neighborhood around a (market) place or park, and the residential space of roughly 4 by 4 blocks with small streets between larger thoroughfares. This has developed quite ‘naturally’. Berlin is the amalgamation of 96 urban districts, most of which were independent villages centuries ago (Schwientek, Citation2020). Another example is Paris. Parisian mayor Anne Hidalgo in preparing to run for a second term in office, announced the vision called “Le ville du 1/4 heure” (or “The 15 minute city”) (Hildalgo, Citation2020a), marking a major, purposeful restructuring of the city around people-friendly, ecological, stress- and pollution-reduced neighborhoods (see ).

Figure 1. The 15-minute city (“Le ville du ¼ heure”).Source: Hildalgo (Citation2020a)

The central idea is to plan for neighborhoods in which everyone is able to run errands, do spare time activities, enjoy greenery and nature, meet friends, and go to the doctor’s, work and school in a limited time on foot, bike, or public transport. This would support a community feeling and minimize transport time, stress, pollution and emissions (Willsher, Citation2020). The father of the 15-minute city, the Sorbonne professor Carlos Moreno, believes that humanity “must move away from oil-era priorities of roads and car ownership as we move into a post-vehicle era” (Willsher, Citation2020) – bringing us to the transport strategy.

Re-MOVE Cities

Necessarily, such a major urban transformation can only succeed with a transport vision. In Paris, the vision for the 15-minute city is a further development of the previous “Plan Vélo” of Mayor Anne Hidalgo. The Plan Veló has removed space for cars and boosted it for cyclists and pedestrians. Hidalgo has promised to further pedestrianize parts of the capital. She promised 350million Euro to create a bike lane in every street of Paris by 2024, a protected bikeway on all Paris bridges, and 60,000 parking spaces fewer for private cars (Hildalgo, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Reid, Citation2020). By 2024, main roads through Paris will be inaccessible to motor vehicles and “children streets” are planned to exist next to schools during term time (Willsher, Citation2020). Another example of a city with car-free neighborhoods is Tokyo/ Japan, which in parts has very peaceful neighborhoods defined around people and greenery (Hill, Citation2020c). They are not necessarily planed as self-sufficient neighborhoods like the Kiez in Berlin and the 15-minute city in Paris, but allow for movement and interaction of people instead of cars. For example, streets in Tokyo’s neighborhoods are usually only about four meters wide and on-street parking is forbidden (generally in Japan since 1963), car parking is integrated into the buildings. Moreover, there is not only restricted private mobility but also restricted cargo delivery in the neighborhoods. Last (half) mile cargo is delivered with small wagons or bikes (Hill, Citation2020c). Other cities that are experimenting with car free zones are London/ United Kingdom, Utrecht and Amsterdam/ Netherlands, and Barcelona/ Spain. Helsinki/ Finland is attempting to eliminate the need for any city resident to own a private car by 2025 (Eggers, Citation2016). Stockholm/ Sweden has a similar approach (Hill, Citation2020b). Oslo/ Norway has banned cars on some shopping streets since 2015 (Hill, Citation2020b), as has Berlin since 2019 (O’Sullivan, Citation2019). Moreover, Berlin has, like Paris, a new bicycle strategy (Berlin et al., Citation2018). I argue for post-pandemic, self-sufficient neighborhoods to slowly reduce, and finally ban the car from streets and Kiez-areas. Cycling is a transport model for the post-pandemic city, as it lowers contact between individuals, fits a Kiez or neighborhood structure, increases health and well-being, and lowers transport emissions.

However, in order to connect the neighborhoods and Kiez’ areas in the post-pandemic city, public transport is indispensable. Air pollution in cities is at the heart of the problem. For example, in US cities, African American communities are disproportionately exposed to air pollution increasing mortality rates from COVID-19 (Bernstein, Citation2020). Post-pandemic cities need to be less polluted, more livable places for all. We therefore need to make public transport convenient and virus-safe. The convenience could, e.g. be provided by superfast, cheap or free, and safe metro/ underground transport that clusters neighborhoods around the stations (Hill, Citation2020c) – while the longing for convenience and safety also poses the risk of residents to turn to the private car. To prevent the resurgence of the private car, public transport in cities should be free of charge. Luxemburg and Tallinn are leading examples (Hill, Citation2020b). To make it virus-safe, cities and public transport providers need to invest in health and safety, e.g. air ventilation and conditioning technology.

In conclusion, cities are likely to go through fundamental changes in the post-pandemic period. This could be a threat, but also marks a huge opportunity for local climate planning. What we can learn from the pandemic is that the root causes of climate change and those of the pandemic are to a large extent the same. To prevent future pandemics, we can therefore invest in eliminating these joint root causes, such as lowering deforestation, habitat and biodiversity loss. We learn that tackling climate change would also help lower the risk of future pandemics.

What we learn in terms of solutions is that a radical re-GREENing of inner cities could mark the corner stone of an urban response in the post-pandemic period, where a decrease in demand for retail and office space has opened up inner city spaces. Such a strategy would also rely on a re-adJUSTment of offices to lower-income housing, a re-STRUCTURing of our cities into a multitude of nodes and neighborhoods in Kiez pattern or the 15-minute-city, and a parallel re-MOVE strategy for transportation systems.

Building on these themes of decentralized, multi-centered, green, and networked urban areas would leave us with more amenable, low-emission, climate-resilient, and healthy, post-pandemic cities than the current model. If we re-orient our cities around more residential space in inner cities, networks of Kiez neighborhoods, urban green infrastructure and car-free, bicycle-friendly, super-fast and free public transport, we could solve the climate crisis, health risks, and social justice concerns at the same time.

Acknowledgments

I thank Julia Rawlins from Climate-KIC Berlin (till 2020) and Ulrike Herklotz from WWF Germany for inspiring talks.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Diana Reckien

Diana Reckien is Associate Professor at the University of Twente/ Netherlands. Her research and teaching covers the interface of climate change governance and urban research with the aim to contribute to justice efforts. Some of her current research questions relate to how climate change mitigation and adaptation policies interact with equity and justice, and how to set up policies in order to avoid respective negative side-effects. Diana contributes to international assessments like the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6, Coordinating Lead Author (CLA) of the Working Group II, Chapter “Decision-Making Options for Managing Risk”) and the Third Assessment Report on Climate Change and Cities (ARC3.3, CLA for Element on “Equity, Development, and Informality”). She also leads the European Initiative on Local Climate Planning (EURO-LCP).

References

- Berlin, Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Verkehr, und Klimaschutz. (2018). Mobilitätsgesetz: Bedeutungsgewinn für den Radverkehr. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/verkehr/verkehrsplanung/radverkehr/mobilitaetsgesetz/

- Bernstein, A. (2020). Coronavirus, climate change, and the environment – A conversation on COVID-19 with Dr. Aaron Bernstein, Director of Harvard Chan C-CHANGE. Harvard T. H. Chan, School of Public Health, Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/c-change/subtopics/coronavirus-and-climate-change/

- Book, S., & Müller, M. U. (2020, July 27). Wie Deutschlands Innenstädte sterben. Spiegel.

- Brubacher, J., Allen, D. M., Déry, S. J., Parkes, M. W., Chhetri, B., Mak, S., … Takaro, T. K. (2020). Associations of five food- and water-borne diseases with ecological zone, land use and aquifer type in a changing climate. Science of the Total Environment, 728(2020), 138808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138808

- Christaki, E., Dimitriou, P., Pantavou, K., & Nikolopoulos, G. K. (2020). The impact of climate change on Cholera: A review on the global status and future challenges. Atmosphere, 11(5), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11050449

- Corbera, E., Anguelovski, I., Honey-Rosés, J., & Ruiz-Mallén, I. (2020). Academia in the time of COVID-19: Towards an ethics of care. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1757891

- Croft, D. P., Zhang, W., Lin, S., Thurston, S. W., Hopke, P. K., Masiol, M., … Rich, D. Q. (2019). The association between respiratory infection and air pollution in the setting of air quality policy and economic change. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 16(3), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201810-691OC

- Dushkova, D., & Haase, D. (2020). Not simply green: Nature-based solutions as a concept and practical approach for sustainability studies and planning agendas in cities. Land, 9(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9010019

- ECDC. (2021). COVID-19 situation update worldwide, as of week 12. updated 1 April 2021. 01.04.2021. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases

- Eggers, W. D. (2016, June 24). Helsinki wants to eliminate the need for car ownership by 2025. Fast Company. 2016, Access: 31.08. 2020.

- Giesen, C., Roche, J., Redondo-Bravo, L., Ruiz-Huerta, C., Gomez-Barroso, D., Benito, A., & Herrador, Z. (2020). The impact of climate change on mosquito-borne diseases in Africa. Pathogens and Global Health, 114(6), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2020.1783865

- Haley, C., Orlik, J., Czibor, E., Cuello, H., Firpo, T., Goettsch, M., & Smith, L. (2020). There will be no ‘back to normal’. Nesta. https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/there-will-be-no-back-normal/

- Hausler, S., Heineke, K., Hensley, R., Möller, T., Schwedhelm, D., & Shen, P. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on future mobility solutions. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-future-mobility-solutions#[07.07.2021]

- Hildalgo, A. (2020a). Le Paris du Quart d’Heure [Press release]. https://annehidalgo2020.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Dossier-de-presse-Le-Paris-du-quart-dheure.pdf

- Hildalgo, A. (2020b). Ville du 1/4h. Paris en Commun. https://annehidalgo2020.com/thematique/ville-du-1-4h/

- Hill, D. (2020a). 11: Post-traumatic urbanism and radical indigenism. Medium. https://medium.com/slowdown-papers/11-post-traumatic-urbanism-and-radical-indigenism-c2a21dc7ba69

- Hill, D. (2020b). Cities kick out the car: Part 2 of ‘And you may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile’. Medium. https://medium.com/

- Hill, D. (2020c). Tokyo’s model mobility, for cities large and small: Part 3 of ‘And you may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile’. Medium. https://medium.com/butwhatwasthequestion/tokyos-model-mobility-for-cities-large-and-small-part-3-of-and-you-may-find-yourself-behind-56db35cfaaa7

- IEA. (2020). Global energy review 2020 - the impacts of the Covid-19 crisis on global energy demand and CO2 emissions. https://webstore.iea.org/download/direct/2995

- IEA. (2021). Global energy review: CO2 emissions in 2020. IEA Article.

- ifo. (2020). ifo institut: Short-term work reaches almost all sectors [Press release]. https://www.ifo.de/node/55086

- IPCC. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Kan, H.-D., Chen, B.-H., Fu, C.-W., Yu, S.-Z., & Mu, L.-N. (2005). Relationship between ambient air pollution and daily mortality of SARS in Beijing. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences, 18(1), 1–4. http://www.besjournal.com/en/article/id/14a73fdf-d8dd-417a-8ad9-66f2986e2094

- Kissler, S. M., Tedijanto, C., Goldstein, E., Grad, Y. H., & Lipsitch, M. (2020). Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science, 368(6493), 860–868. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb5793

- Landry, C. (2020, June 10). So werden wir leben/Interviewer: M. Wellershoff & U. Knöfel. Spiegel Magazine, Spiegel Magazine. https://www.spiegel.de/panorama/gesellschaft/stadt-der-zukunft-nach-corona-nur-die-jungen-koennen-die-innenstaedte-retten-a-30bc8f65-5bee-4f2f-bf36-e2619d3d424a

- Moore, K. A., Lipsitch, M., Barry, J. M., & Osterholm, M. T. (2020). COVID-19: The CIDRAP viewpoint. CIDRAP, Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/sites/default/files/public/downloads/cidrap-covid19-viewpoint-part1_0.pdf

- Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Sohrabi, C., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., Iosifidis, C., … Agha, R. (2020). The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery (London, England), 78(2020), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018

- O’Sullivan, F. (2019, August 8). Why Berlin’s approach to car bans is a little different. Bloomberg CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-08/berlin-s-popular-shopping-streets-will-go-car-free

- Raymond, C. M., Frantzeskaki, N., Kabisch, N., Berry, P., Breil, M., Nita, M. R., Geneletti, D., & Calfapietra, C. (2017). A framework for assessing and implementing the co-benefits of nature-based solutions in urban areas. Environmental Science & Policy, 77(2017), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.008

- Reid, C. (2020, January 21). Paris to be cycle-friendly by 2024, promises Mayor. Forbes.

- Schulz, B. (2020). Für eine andere Zukunft gebaut. Zeit Online. https://www.zeit.de/wirtschaft/2020-07/london-buero-gebaeude-arbeitsplaetze-homeoffice-produktivitaet

- Schwientek, H. (2020). Berlin – Geschichte des Stadtgebiets in vier Karten 1806 • 1920 • 1988 • 2020. Edition Gauglitz. http://edition-gauglitz.de/berlin-geschichte-des-stadtgebiets-in-vier-karten-1806-%E2%80%A2-1920-%E2%80%A2-1988-%E2%80%A2-2020

- Stone, J. (2020, April 27). Public support universal basic income, job guarantee and rent controls to respond to coronavirus pandemic, poll finds. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/coronavirus-poll-universal-basic-income-rent-control-job-safety-a9486806.html?amp

- Tang, S., Yan, Q., Shi, W., Wang, X., Sun, X., Yu, P., … Xiao, Y. (2018). Measuring the impact of air pollution on respiratory infection risk in China. Environmental Pollution, 232(2018), 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.071

- The Economist. (2020, June 11). Great cities after the pandemic. The Economist.

- UNESCO. (2020). COVID-19 impact on education. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

- von Beust, L. (2020). Hotline für Coronahilfe von nebenan – Spende für deine Nachbarschaft. betterplace.org – Deutschlands größte Spendenplattform. https://www.betterplace.org/de/projects/78125-hotline-fuer-coronahilfe-von-nebenan-spende-fuer-deine-nachbarschaft

- Willsher, K. (2020, February 7). Paris mayor unveils ‘15-minute city’ plan in re-election campaign. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/07/paris-mayor-unveils-15-minute-city-plan-in-re-election-campaign

- Wu, X., Nethery, R. C., Sabath, B. M., Braun, D., & Dominici, F. (2020). Air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States: Strengths and limitations of an ecological regression analysis. Science Advances, 6(45), eabd4049. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd4049

- Zhao, Y., Richardson, B., Takle, E., Chai, L., Schmitt, D., & Xin, H. (2019). Airborne transmission may have played a role in the spread of 2015 highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks in the United States. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 11755. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47788-z