How to plan for urban development in pluralistic societies, where the interests of diverse social groups inevitably collide? This is one of the most fundamental and difficult questions that planning theory has sought to address over many decades. A definitive answer may never emerge, but in this reflective piece we argue that the last few decades of planning in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) offer especially instructive lessons on the topic. Once the global center of authoritarian state socialism and the command economy, CEE societies have been transitioning into pluralist democracies for thirty years. This transition penetrated all areas of social life: politics, economics, culture, as well as urban and regional development (Stanilov, Citation2007; Tsenkova & Nedovic-Budic, Citation2006). Centralized planning, which guided CEE’s development through the post-WW2 decades, was immediately abandoned after the “velvet revolutions” of 1989. Furthermore, socialist planning gave all planning a bad name (Daskalova & Slaev, Citation2015; Hirt, Citation2005; Nedovic-Budic, Citation2001) and in the 1990s, most cities in CEE ceased to engage in planning altogether (Hirt & Stanilov, Citation2009). In Bulgaria, the country we use as our example, not a single major city adopted a new master plan between 1989 and 2003. The idea that planning is a negative socialist legacy began to fade away in the early 2000s. An important factor in planning’s cautious revival since then has been the accession of several CEE countries to the European Union, as new member states were expected to adopt basic EU planning principles (Anderson et al., Citation2012).

CEE cities may be especially revealing cases in how planning could and should (not) work. In the last decades of the 20th century, these cities moved from one extreme to the other: from being highly and only centrally planned in the 1980s to being market-driven and not planned in the 1990s. Neither of these extreme models, we argue, worked very well, and planners in CEE have been searching for new, better, more flexible ways of planning ever since. The “new” (revived) planning system of the 2000s faced difficulties unknown under state socialism. Democracy meant that social groups could coalesce, articulate, and defend their interests in opposition, not only to each other, but to government planners in ways that were impossible in the past. Planners were ill prepared for this new reality. There was little agreement on what the post-socialist planning model should be and how it should be theoretically justified. In this paper, we argue that a successful contemporary planning model must be decentralized and stem from a clear recognition of the pluralistic structure of today’s CEE’s societies.

We make this argument by exploring the evolution of planning in Bulgaria’s third largest city and “Sea Capital,” Varna (population 440 K), which is located at the northern part of Bulgaria’s Black Sea shore. Varna’s region includes invaluable and unique natural and archeological assets. It is a well-known European tourist site, as well as a national industrial center. We first define what we mean by “centralized’ (top-down) and “decentralized” (bottom-up) planning,Footnote1 acknowledging that in reality all forms of planning fall somewhere in between. Next, we study the planning of Varna and its region in three stages: the 1980s, the 1990s, and the early 2000s. Finally, we discuss what planners in other contexts can learn from Varna’s planning travails. Our conclusion is that decentralized planning is better not only because it is inherently more democratic. Decentralized planning is better than its centralized predecessor because, by taking into account the functioning of markets and the necessity of navigating plural interests, it produces better results.

Key Theoretical Concepts

For the purposes of this paper, we contrast two basic types of planning (centralized vs. decentralized) in two basic types of society (homogeneous vs. pluralistic) acknowledging, again, that all forms of planning and society fall somewhere between the two idealized extremes.

Consider, first, planning in a hypothetical, non-pluralist, socially homogeneous society. Such a society may never have existed, yet during the period of state socialism (1945–1989), the countries in CEE and the USSR claimed to have achieved it by eliminating classes and therefore, class-based interests and conflicts.Footnote2 The idea was that since the socialist state owned a very high share of land, real estate, and means of production, it could ensure the just and wise distribution of material resources to all people – more so than in any society where private property and “free markets” dominate the scene. Because citizens of socialist countries had similar material resources, they belonged to the same class and had similar interests and preferences (Barnard & Vernon, Citation1977).Footnote3 The idea of social homogeneity justified the single-party political system that existed in socialist states. The public interest was assumed to be universal and unanimously agreed upon (Pannekoek, Citation1947); hence, competing political parties were unnecessary. The power center of society – the central government with its many local agencies and well-trained technocrats – knew very well what the public interest was. Therefore, planning conducted in a centralized, top-down fashion was good enough for everybody (Tinbergen, Citation1964). Bottom-up, decentralized, citizen-driven planning efforts were, in this system, deemed redundant.

In pluralist societies, which today are typically market economies, of course, none of the above applies. In such societies, most property is owned by private individuals and entities, although public property may, too, be widespread (e.g. infrastructure). The private ownership of land, real estate, and production forms the basis of decentralized market relations, whereas resources owned by public entities are typically managed in a more centralized fashion (Moroni, Citation2018; Moroni & Cozzolino, Citation2019; Slaev et al., Citation2019). Markets and planning are inevitably and constantly interacting (Lai, Citation2016, Slaev, Citation2017) and should be considered complementary mechanisms of social coordination (Alexander, Citation2014; Bertaud, Citation2004). Yet, the dominance of private ownership means that different groups have very different access to material resources, and therefore espouse different, often conflicting views. To identify a common public interest is a challenging, if not impossible, task.Footnote4 Hence, to succeed, planning must be, to a significant degree, decentralized and responsive to markets, much as markets must be responsive to planning to succeed.Footnote5

In short then, we define centralized planning as planning whose goals are defined by the center of power (government and its planners) and decentralized planning as planning whose goals are defined by multiple social groups through a relatively decentralized process. We apply these concepts to an empirical case. Based on the case, we propose that while centralized planning may “work,” to an extent, in relatively homogeneous societies, in pluralistic societies – planning must be decentralized to succeed. Among its other benefits, we argue, decentralized planning “cooperates” with markets (which are typical of, although not synonymous, with pluralist societies) better, likely producing better results for both planning and markets.

Key Empirical Sources

Our empirical study focuses on Bulgaria and, specifically, the city of Varna, where planning methods changed from highly centralized to mostly decentralized, following the growing pluralism of Bulgarian society in the aftermath of state socialism. The country (re)established a multi-party system in 1990. Quickly thereafter, most land, real estate, and means of production were either restituted or privatized, leading to a sharp stratification of society and a diversification of public life (Hirt, Citation2012, Mizov, Citation2008). Public planning of any type nearly ceased in the 1990s. It regained legitimacy after the chaotic 1990s and was reinstituted in the 21st century in the form of numerous national laws and city and regional plans and strategies. Bulgaria entered the EU in 2007, which further strengthened planning practices in the country.

We study Varna’s planning in three stages: the socialist 1980s, the post-socialist 1990s, and the early 2000s. Sources include the main planning documents of the city and its region as well as evidence of the plans’ implementation (or lack thereof) from the National Statistical Institute, media and other sources. We interviewed five prominent planners including the leaders of the teams which elaborated two of the plans, as well as three representatives of the municipal government, and three leaders of major environmental NGOs which were very active during the preparation of the latest master plan of the city.

We seek to distinguish between centralized and decentralized planning in Varna by exploring whether, how, and to what extent planning has been in line with the preferences of local citizens and other stakeholders. When planning reflects only the vision of central authorities but pays little attention to the preferences of local stakeholders, we consider it centralized. When it reflects the preferences of local stakeholders, we consider it decentralized. We further discuss the relationship between planning and the market and specifically, whether planning “learns” from market signals, failures, and successes.

Case Study

Socialist Planning

Through the socialist period, three goals dominated Varna’s planning. First came the quick resolution to the housing problem, which existed because of the high rates of industrialization and urbanization: in four decades (1945–85), Varna’s population had grown four-fold. Like other large socialist-era urban centers, Varna adopted a single strategy to solve this problem: prefabricated construction technologies. As these technologies needed vast vacant lands, all new housing construction from the late 1960s took the form of prefab estates located in the urban periphery. The second major goal was to boost Industrial development. This goal was also typically socialist: the massive state investment in heavy industry (in Varna’s case, chemical industry) was seen as necessary to out-compete the West. In Varna’s region, four large chemical plants were built by the mid-1970s. These were located at the western end of Lake Varna, in the neighboring municipality of Devnya, forming “The Valley of the Great Chemistry.” The third major goal was the development of tourism. Bulgaria’s Black Sea Coast was known as the “Red Riviera” – the summer holiday center of the Eastern Bloc. Two big sea resorts were developed east of Varna in the 1950s and the 1960s: Zlatni Pyasatsi (Golden Sands) and Drujba (Friendship), later renamed St. Constantine and Elena (). With 70 hotels and almost 15,000 beds, Golden Sands was the country’s second-largest resort and it was full of international tourists, bringing in “hard” currency, every summer. Yet, planners certainly gave international tourism lower priority compared to industry.

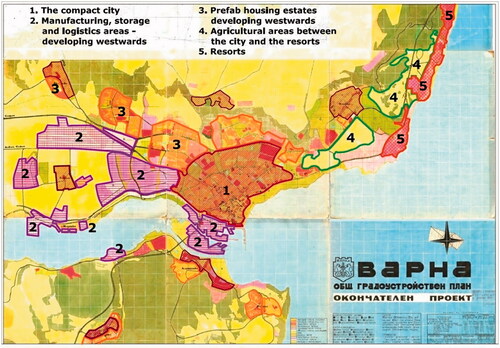

Varna prepared a General Urban Development Plan (GUDP) in 1982 (). This plan had goals and strategies typical of socialist Bulgaria and the rest of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) at the time. First, to solve the housing problem, the plan directed the expansion of prefabricated housing. All new housing estates were to be located westwards of the city to accommodate the workers of the chemical plants, which were on the west side. Second, the GUDP aimed to facilitate further heavy industrial development – from the port at the mouth of Varna Lake, along its banks, to the west, again closer to the chemical plants. The plan barely dealt with tourism and recreation. It allocated no new lands for tourism; instead, the large areas between the already-existing resorts and the city were reserved for agriculture.

The Post-Socialist 1990s

The fall of socialism was accompanied by a massive decline in virtually all sectors of the Bulgarian economy, especially heavy industry (Mihov, Citation1999). In the “Valley of the Great Chemistry,” three of the large chemical enterprises were nearly bankrupt before they were privatized by foreign companies, from Belgium, Italy, and the USA. It took the new owners several years to revive production.Footnote6

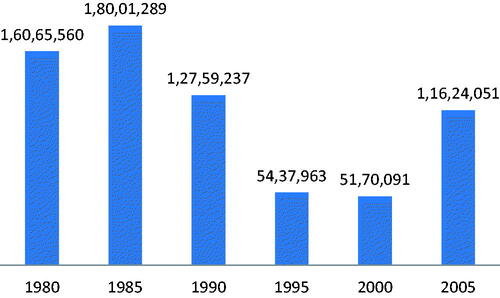

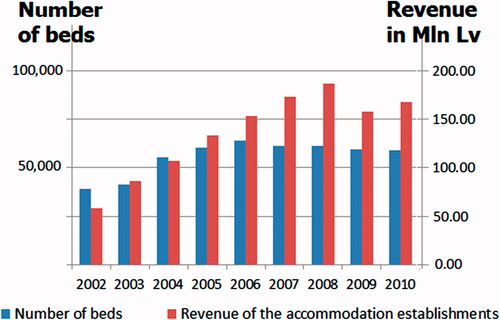

Tourism went downhill as well. From 1985 to 1995, the number of nights spent by foreign tourists in Varna’s tourist establishments dropped by 67%; nationally, it dropped by 70% ().

The housing sector, too, transformed. The big construction enterprises that had built the prefabricated estates in Varna (and all Bulgarian cities) were quickly dismantled. Numerous small private companies using traditional brick construction took their place. The traditional technologies were by far more suitable for small, centrally located in-fill urban lots, rather than vast empty lands in the urban periphery. Thus, after a brief sharp decline, housing growth in Varna resumed but, for the first time in decades, in the city center. In the mid- and late 1990s, the construction boom in Varna’s center was driven by local demand. In the early 2000s, a second wave of new construction began, this time sparked by high foreign demand for holiday properties along the Bulgarian Black Sea coast.

Through the 1990s – when planning in Bulgaria was considered retrograde and no city engaged in master planning – one exception stood out. This was the 1995–96 comprehensive Territorial Planning Scheme (TPS)Footnote7 for the Bulgarian Black Sea coast, funded by the World Bank. The TPS focused on tourism. More than ever during socialism, the growth potential of the tourism sector in Bulgaria was recognized. Tourism, rather than industry, was seen as a potential “locomotive” to pull the nation’s economy forward.

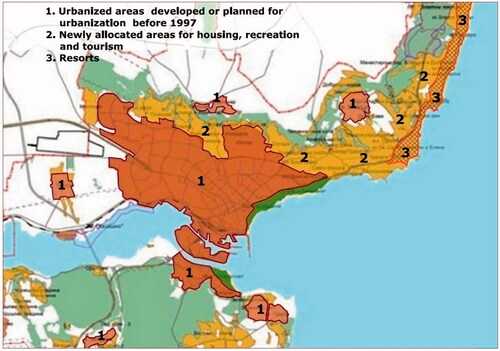

Between 1996 and 1998, the TPS was followed by Territorial Development Plans (TDPs) of all individual Black Sea municipalities. Varna’s TDP was prepared in 1997 () with a focus on tourism. As the two interviewed leaders of the team elaborating the plan explained,Footnote8 this represented a 180-degree turnaround in planning emphasis. Whereas the 1982 plan ignored tourism to promote manufacturing and, to a lesser extent, agriculture, the 1996–98 plan ignored manufacturing and agriculture to promote tourism. The agricultural territories between the city and the resorts on the east side were re-allocated for tourism, recreation, and housing. The TDP, thus, became the first plan of Varna to forego westward expansion and promote the city’s north-eastern, eastern, and southern areas – all closer to the sea. The plan called for major improvement in the quality of tourist facilities and services (Matev & Assenova, Citation2012). It recommended a small number of new hotels and the renovation of existing ones. It was the planners’ belief, as interviewees attested, that moderate lot coverage and generous open spaces, combined with higher quality of buildings and landscapes, would make Varna’s region more attractive to Western tourists.

But the planners’ vision was not implemented. As it turned out, the numerous private landowners in Varna had views on development and open-space preservation quite opposite to those of the planners. As the then-Chief Architect of the city and, later, Deputy Mayor from 2000 to 2010,Footnote9 recalled in an interview, the government was under “massive pressure” by landowners lobbying the Municipal Council to sharply increase the permissible intensity of construction and, thus, allow for greater private profits. Caving under this pressure, only two years after the TDP’s adoption, in 1999, Varna adopted a new planning ordinance: “Specific Rules of Property Development in Varna Municipality.” The Rules nominally kept the same land-use designations as the TDP but overruled the TDP’s recommendations for moderate lot coverage and generous open-space preservation. The Rules permitted building heights and floor-to-area ratios several times greater than those in the TDP. Supported by an active coalition of landowners and developers, the Rules became the key administrative instrument guiding Varna’s growth in the next dozen years. They facilitated the ensuing boom in the construction of new hotels and holiday apartments, driven by the high demand for Bulgarian holiday properties by foreign buyers in the early 2000s.

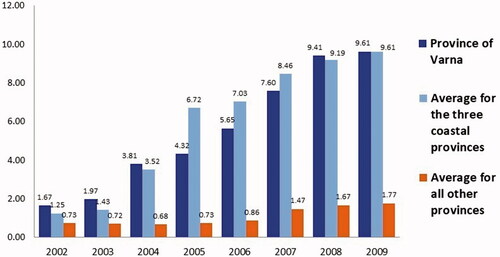

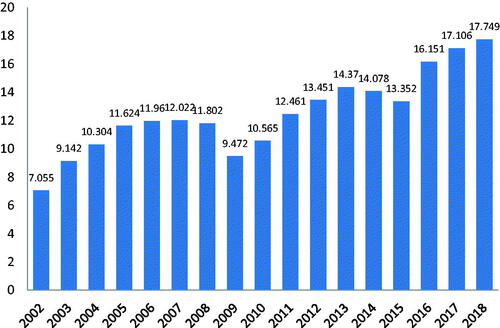

The planning documents of the late 1990s had a significant impact on Varna. The growth in tourism envisioned by Varna’s TDP became a reality, but the planned improvements in quality did not materialize. From 2002 to 2006, the number of hotels and other tourist accommodations grew 3.55 times and the number of beds 1.75 times in just four years. The growth in revenues received by tourist establishments was similarly high (). The increase in construction of holiday homes was even more dramatic. In Varna’s province, the number of newly built homes grew almost seven-fold between 2002 and 2009. The rate of construction of homes per person in the three coastal provinces (including Varna’s) was 5.42 times higher than in the rest of Bulgaria ().

One could say, then, that the tourism sector did play the role of a “locomotive” pulling other economic sectors forward, as planners had hoped in the aftermath of socialism. In 2005, the sector generated 4.5% of Bulgarian GDP, but its total contribution to the economy, including indirect contribution to sectors like agriculture and construction, was 15.9% (Anderson et al., Citation2012). In 2007, tourism and the sales of holiday homes comprised 78.7% of all direct foreign investment in the Bulgarian economy (BNB (Bulgarian National Bank), Citation2009). Yet, most of this growth came at the expense of green spaces in cities such as Varna and their vicinities.

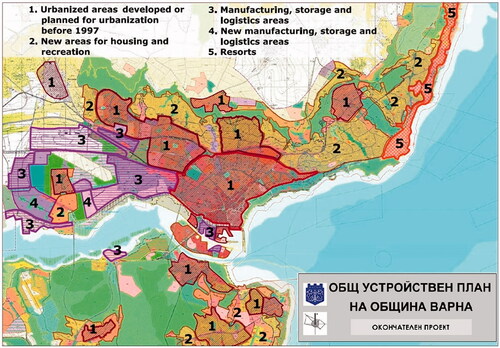

The 2012 General Urban Development Plan

The 2012 General Urban Development Plan in 2005, Varna began its first master plan since 1982: the new General Urban Development Plan (GUDP). The preliminary draft was completed in 2007. It took five more years to adopt the final version (), because of major disagreements between different interest groups.Footnote10 Landowners and developers wanted intense new construction everywhere, but environmentalists and many residents preferred more open space. On several occasions, conflicts sparked between municipal executives and environmental NGOs. Municipal planners had to seek a compromise. The GUDP adopted high-intensity construction standards in Varna’s central areas, much as the Specific Rules from 1999 had allowed. But, it decreased the permitted intensity of construction in many areas designated for tourism, outside the city proper, as the 1997 TDP had proposed, thus echoing the TDP’s overall goal for qualitative, rather than quantitative improvement in tourism. Areas for tourism and housing were increased by 1639 ha and those for public green space (forests and urban parks) by nearly 900 ha.Footnote11

Diagram 1. Number of nights spent by foreign tourists in Bulgarian tourist accommodation establishments (NSI Citation2012a).

Diagram 2. Growth in the number of beds and revenues received by tourist accommodation in the Province of Varna, 2002–2010 (NSI Citation2012a).

Diagram 3. Number of newly completed housing units in the Province of Varna per 1000 of population, compared to the average for the three coastal provinces and the average for all other (non-coastal) Bulgarian provinces (NSI Citation2012b)

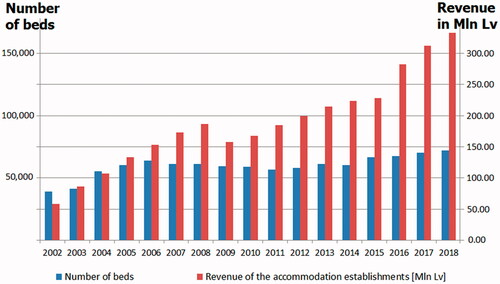

In the meantime, the rates of construction varied following global economic realities. The Global Recession that started in 2007–08 slowed all growth in Bulgaria, as elsewhere. Growth resumed in 2011. The rates of housing construction, including that of tourist establishments, remained lower than during the earlier construction-boom years (NSI, Citation2012a). Yet, revenues in the tourist sector grew substantially, almost doubling between 2009 and 2018 (). We seek to explain this seeming contradiction at the end of the next section.

Diagram 4. Millions of nights spent by foreign tourists in Bulgarian tourist accommodation establishments between 2002 and 2018 (NSI Citation2012b).

Discussion

In this section, we evaluate whether Varna’s planning from 1982 to 2012 has decentralized. We ask:

To what extent have planning goals been defined by the center of power and to what extent by residents and stakeholders?

To what extent has planning “cooperated” with the market, especially in the latest plan?

The Switch from Centralized to Decentralized Planning

Varna’s 1982 GUDP is a clear example of the top-down, centralized approach. Planning was dominated by priorities typical of socialist governments across CEE: heavy industry and prefab housing estates. Whereas the intent behind those priorities was benevolent – to spur economic growth and provide mass housing – the solutions incorporated no local preferences whatsoever. Boosting heavy industry by designating massive industrial territories was a universal approach in socialist Bulgaria; as one of the country’s most prominent planners noted: “in some cases, we planned industrial zones bigger than the cities that they were adjacent to.”Footnote12 In Varna’s case, although four large chemical plants were already situated in neighboring Devnya, the 1982 GUDP allocated more land for industry and directed all future housing westward – closer to Devnya’s chemical plants. There is no evidence that people in Varna desired to live in prefabricated housing by the polluting chemical plants. On the contrary, a traditional preference of Bulgarians at the time (as well as Southeastern Europeans generally) was to be in city centers (see Slaev et al., Citation2018). But planners in 1980s Varna never studied local public opinion, nor considered local, or foreign for that matter, tourist demand. Bulgarian sea resorts of the 1980s were coveted by both local and foreign, mostly Eastern-Bloc, tourists. But planners reserved the large eastern territories of Varna around the seaside resorts for agriculture. According to Ivanova (Citation2019), the number of hotels and tourist beds that existed in the 1980s met only about half the tourist demand.

Compared to the 1980s, the 1997 TDP was an important step away from the centralized method. The leaders of the planning process, interviewed here, clearly stated that tourism became top priority. The TDP directed Varna’s development north-east, east and south – certainly areas the local population and tourists preferred. Yet, planners’ long experience in ignoring public opinion persisted. The authors of the TDP believed that moderate new development and open-space preservation are the good goals (which they may be); the right, “professional position.” But the “non-professionals,” local landowners and developers, had different ideas in mind. At every turn, they asked for amendments, way exceeding what the TDP permitted. As an interviewed planner, who turned into a politician, explained, landowners’ pressure on the Municipal Council was so heavy that the planners accepted defeat of their “professional position” by adopting the 1999 Specific Rules and Norms and increasing permitted new development many times beyond what they had argued for just two years earlier. The 1999 Rules, one may say, were the culmination of the zeitgeist of the first post-socialist decade: to seek immediate economic growth and accommodate private-sector demands, regardless of long-term environmental harms that were well recognized by the professional community (e.g. see Holleran, Citation2017). The Rules provided a powerful impetus to the intense development that characterized the next decade. But they certainly did not reflect the interests of all citizens. Environmentalists and many regular citizens of Varna were against this intense, space-consumptive growth. With time, enthusiasm for this type of growth subsided. By the early 2000s, the views of environmentally minded NGOs and citizens, dissatisfied with the loss of green space, became increasingly popular in the media and broader society (Georgiev, Citation2013; Nikolov, Citation2012).

As citizens and groups in Bulgaria became more vocal about their interests, the process of plan adoption became much more difficult. Whereas previous plans moved toward adoption quickly, the 2012 GUDP of Varna took five years. If we compare the standards in the 2012 GUDP with the 1999 Rules, we can see that planners navigated competing viewpoints, and sought compromise – a process which took the unprecedented five years. The GUDP prescribed high-intensity development in central urban areas, pleasing central-city landowners, but in many areas in Varna’s vicinity new development was restricted, reflecting the interests of environmentalists. This time, planners had to conduct public discussions, according to the National Spatial Planning Act, which was revised repeatedly between 2007 and 2012 with stricter requirements for citizen hearings. According to the interviewed planners, half a dozen meetings were held at the city level and about a couple of dozen in individual city districts. Planners’ comments indicate that they did not like the “interference” by non-professionals. But they learned to live with them, realizing, as Varna’s current Chief Architect said, that compromise was necessary to pass the plan.Footnote13

In the meantime, Bulgaria passed stricter national environmental standards (e.g. in areas protected by the EU’s environmental network Natura 2000). These standards favored the environmentalists’ position on restricting new development in open spaces. Landowners continued to vocally express their pro-development views in public discussions when their properties were affected by the plan. But the environmental organizations were active and vocal as well and had more significant public backing.

According to interviewed leaders of environmentalist NGOs, they used four main channels to work towards their goals. First was participation in the public discussions. Second came social networks and media. Third, they took disputes to the courts. Finally, they organized public protests to protect open space. The most prominent example was when a powerful private company bought a large lot from the municipality in Varna’s “First Alley,” by the iconic Sea Garden. The company intended to develop the lot but was faced with mass protests, which halted the process, at least temporarily.

Interaction between Planning and the Market in the 2012 GUDP

The 2009–2012 global crisis popped the real estate bubble in Bulgaria and helped set realistic market values. It was also a major factor in slowing down tourist-oriented construction in urban environments and their previously pristine surroundings. Construction rebounded after 2012, but at a lower rate.

Yet, the slowdown in new tourist development did not translate into a slowdown in tourist revenues. allows us to draw a comparison between trends in the construction of new facilities and trends in tourism revenue in Varna province. We distinguish three periods. In the first period, 2002–2008, tourist revenues grow alongside a rapid increase in the number of new hotel beds. At the peak of the economic crisis, 2009–2011, a slight decrease in the number of bedsFootnote14 leads to a decrease in revenues. In the third, post-Recession period, 2011–2018, however, the number of tourist beds increases only slightly, yet revenues increase significantly. It seems then that during the first period, the increase in tourist revenue came from intense new development. The tourism and construction businesses earned high profits. One could say that citizens benefited from job provision and economic growth, but they suffered as green spaces were consumed and the natural environment deteriorated. In the third period, the rapid increase in revenues was realized at a lower environmental cost – less new land consumed. Perhaps the growth in revenues was the result of the general improvement of market conditions, perhaps it was the result of the better functioning of facilities built in the first period. One way or another, however, during the last period planners understood they cannot force open-space preservation onto reluctant local landowners, who were seeking to maximize their profits. Planners also learned they could not bypass environmental NGOs.

Diagram 5. Comparison between the rates of growth in revenue of accommodation establishments and the rates of change in the number of beds in the province of Varna, 2002–2018 (NSI, Citation2012a, Citation2012b).

Conclusions

In this commentary, we studied Bulgaria’s Sea Capital Varna over thirty years to better understand how planning can and should evolve as societies become less centralized and more pluralistic. We relied on limited data from local and national statistical sources, the provisions of planning documents, interviews with key participants, and evidence of plan implementation from media sources and our own long-term observations. Regardless of these limitations, we believe the study demonstrates the relevance of decentralized planning to pluralistic, market societies. In Varna’s case, the 1997 TDP failed because it adhered to the centralized, “professional” approach. Varna’s myriad landowners and market players defeated it and had their interests promoted by the Specific Rules of 1999. In a second turnaround, residents and environmentalists raised their voices more loudly after 2007 and the result was the 2012 plan, which yielded something to both landowners and environmentalists. A better balance between planners’ goals and those of stakeholders was established as a result of the active participation of environmentally minded citizens, as well as the sobering effect of the economic crisis. This balance seems to have improved the long-term performance of the leading sector of Varna’s economy, tourism. Thus, decentralized planning coordinated with the market better than its centralized predecessor.

This story is not rosy. Even with planners’ current – and modest – levels of success, the substantial environmental damage that has already occurred along Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast is irreversible in many locations. Still, the story is positive insofar as it shows that markets and planning – two institutions inherent to modern democracies – can mutually benefit from deeper interaction. We cannot claim that decentralized planning in pluralistic societies is necessarily “right”: its success, we assume, depends on the institutional framework, and the development of institutions is a slow and difficult process. What kind of institutions we should strive for is a question for another, much larger project. And while the high performance of decentralized planning is not guaranteed, we suspect that it will perform well in the long term, if democratic institutions in CEE continue to develop. Perhaps an important part of democratic development is to further examine how planning and markets may benefit from each other.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the editors for their thoughtful comments. We also thank Dr. Umit Yilmaz and Dr. Julie Steiff for their input on the early drafts.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aleksandar Slaev

Aleksandar Slaev is Professor of Urban and Regional Planning at Varna Free University and lecturer in Financing Urban Development at the University of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geodesy, Sofia; His research interests include planning theory, market-planning relationships, decentralized methods of planning, environmental protection, and payments for ecosystem services. Email: [email protected]

Sonia Hirt

Sonia Hirt is Dean and Hughes Professor in Landscape Architecture and Planning at the College of Environment and Design at the University of Georgia, USA; Her research interests include post-socialist urban planning, comparative urbanism, land-use regulation, and public/private spaces. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 By “decentralized planning,” we mean planning that engages decentralized agents (residents, stakeholders, groups). Thus, our use of the concept is different from the other legitimate and popular use of the term to signify the decentralization of planning powers from higher-tier to lower-tier governments. We use “decentralized planning” interchangeably with “bottom-up planning” and “centralized planning” interchangeably with “top-down planning,” acknowledging here that the terms may be more complex.

2 The truth, of course, was that CEE socialist societies were never homogeneous: there is a huge literature showing that although disparities in access to material assets were smaller than in capitalist nations, they remained a fact of life throughout the socialist period (e.g., see Djilas, Citation1966; Henderson et al., Citation2005).

3 In the Marxist textbook, all interests are material interests (culture was considered a “superstructure”: a consequence of material conditions). If everyone has the same material resources, all other divisions – such as those based on culture, including ethnicity, religion, etc. – are inconsequential. A society in which citizens are economically homogeneous is a society in which citizens have similar interests.

4 It could well be argued that the recognition of societal pluralism has been the key reason for the emergence of alternatives to the traditional, top-down technocratic planning method that prevailed even in western countries prior to the 1960s – alternatives such as advocacy planning (Davidoff, Citation1965), collaborative planning (Healey, Citation1997), communicative planning (Innes, Citation1995), and deliberative planning (Forester, Citation1999).

5 Even classic free-market proponents, such as Hayek (Citation1944), agree that to function smoothly, markets require “certain kinds of government action,” including planning (also Alexander Citation2014; Lai & Davies, Citation2017).

6 The Chlorine and Polyvinyl Chloride Plants, the single plant privatized by a Bulgarian company, never recovered.

7 Under Bulgarian law at the time, a Territorial Development Scheme (or Plan) pertained to a city and its surrounding settlements and territories, whereas a General Urban Development Plan pertained only to the city itself.

8 Arch. Staynov and Arch. Petrovich – the names of the interviewees are revealed with their permission.

9 Arch. V. Zhetchev; name is cited with his permission.

10 The local media included many articles reflecting the debate; for example, the sites sopa.bg, Citation2009 and moreto.net, Citation2012.

11 Interviewed prominent environmentalists considered this increase grossly insufficient. They also have a critical view of the latest GUDP.

12 Arch. I. Nikiforov whose career spans five decades. He led the team preparing the 2012 GUDP. Name is cited with permission. On excessive zoning for industry in socialist-era CEE, see also Bertaud, Citation2004; Hirt & Stanilov, Citation2009.

13 Arch. V. Bouzev; name included with permission.

14 During this time, no new hotels were constructed, and some existing ones operated with reduced capacity.

References

- Alexander, E. R. (2014). Land-property markets and planning: A special case. Land Use Policy, 41, 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.04.009

- Anderson, R., Hirt, S., & Slaev, A. (2012). Planning in market conditions: The performance of Bulgarian tourism planning during post-socialist transformation. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 29(4), 318–334. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43030985.pdf

- Barnard, F. M., & Vernon, R. A. (1977). Socialist pluralism and pluralist socialism. Political Studies, 25(4), 474–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1977.tb00460.x

- Bertaud, A. (2004). The spatial organization of cities: Deliberate outcome or unforeseen consequence? WP 2004-01, Institute of Urban and Regional Development.

- BNB (Bulgarian National Bank). (2009). www.bnb.bg/bnb/home.nsf/fsWebIndexBul?OpenFrameset

- Daskalova, D., & Slaev, A. D. (2015). Diversity in the suburbs: Socio-spatial segregation and mix in post-socialist Sofia. Habitat International, 50, 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.07.007

- Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978187

- Djilas, M. (1966). The new class. Unwin Books.

- Forester, J. (1999). The deliberative practitioner: Encouraging participatory planning processes. MIT Press.

- Georgiev, N. (2013). 200 citizens of Varna protest defending Irakli [In Bulgarian: 200 варненци излязоха на протест в защита на “Иракли”]. Petel.bg. Retrieved January 14, 2013, from, https://petel.bg/200-VARNENTSI-IZLYAZOHA-NA-PROTEST-V-ZASHHITA-NA––IRAKLI––SNIMKI-__29374

- Hayek, F. A. (1944). The road to serfdom. University of Chicago Press.

- Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning: Shaping places in fragmented societies. Macmillan.

- Henderson, D. R., McNab, R. M., & Rózsás, T. (2005). The hidden inequality in socialism. The Independent Review, 9(3), 389–412. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24562283

- Hirt, S. (2005). Planning the post-communist city: Experiences from Sofia. International Planning Studies, 10(3–4), 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563470500378572

- Hirt, S. (2012). Iron curtains: Gates, suburbs and privatization of space in the post-socialist city. Wiley Blackwell.

- Hirt, S., & Stanilov, K. (2009). Twenty years of transition: The evolution of urban planning in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, 1989–2009. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT).

- Holleran, M. (2017). Tourism and Europe’s shifting periphery: Post-Franco Spain and post-socialist Bulgaria. Contemporary European History, 26(4), 691–715. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960777317000352

- Innes, J. (1995). Planning theory’s emerging paradigm: Communicative action and interactive practice. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 14(3), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9501400307

- Ivanova, M. (2019). Turizam pod nadzor [Tourism under surveillance]. Ciela.

- Lai, L. W. C. (2016). As planning is everything, it is good for something! A Coasian economic taxonomy of modes of planning. Planning Theory, 15(3), 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095214542632

- Lai, L. W. C., & Davies, S. N. G. (2017). A Coasian boundary inquiry on zoning and property rights: Lot and zone boundaries and transaction costs. Progress in Planning, 118, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2016.05.001

- Matev, D., & Assenova, M. (2012). Application of corporate social responsibility approach in Bulgaria to support sustainable tourism development. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 14(6), 1065–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-012-0519-9

- Mihov, I. (1999). The economic transition in Bulgaria 1989–1999. INSEAD.

- Mizov, M (ed.) (2008). Социална стратификация и социални конфликти в съвременна България [Social stratification and social conflicts in today’s Bulgaria]. Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

- MORETO.net. (2012). Nature advocates: The comprehensive development plan of the municipality of varna defends land swaps and building in protected areas [In Bulgarian: Природозащитници: ОУП-Варна защитава горските заменки и застрояването на защитените територии]. Retrieved August 21, 2012, from http://www.moreto.net/novini.php?n=182751&c=02

- Moroni, S. (2018). The public interest. In M. Gunder, A. Madanipour, & V. Watson (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of planning theory (pp. 69–81). Routledge.

- Moroni, S., & Cozzolino, S. (2019). Action and the city. Emergence, complexity, planning. Cities, 90, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.039

- Nedovic-Budic, Z. (2001). Adjustment of planning practice to the new Eastern and Central European context. Journal of the American Planning Association, 67(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360108976354

- Nikolov, Y. (2012). A sea of powerlessness [In Bulgarian: Море от безсилие]. Kapital. Retrieved April 20, 2012, from https://www.capital.bg/politika_i_ikonomika/bulgaria/2012/04/20/1812226_more_ot_bezsilie/

- NSI (National Statistical Institute). (2012a). https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/7076/nights-spent-and-arrivals-foreigners-accommodation-establishments; https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/5782/newly-built-dwellings-completed

- NSI (National Statistical Institute). (2012b). https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/5782/newly-built-dwellings-completed; https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/7076/nights-spent-and-arrivals-foreigners-accommodation-establishments

- Pannekoek, A. (1947). Public ownership and common ownership. Western Socialist. Journal of Scientific Socialism in the Western Hemisphere, 14, 132.

- Slaev, A. D. (2017). The relationship between planning and the market from the perspective of property rights theory: A transaction cost analysis. Planning Theory, 16(4), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095216668670

- Slaev, A. D., Kovachev, A., Nozharova, B., Daskalova, D., Nikolov, P., & Petrov, P. (2019). Overcoming the failures of citizen participation: The relevance of the liberal approach in planning. Planning Theory, 18(4), 448–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095219848472

- Slaev, A. D., Nedović-Budić, Z., Krunić, N., Petrić, J., & Daskalova, D. (2018). Suburbanization and sprawl in post-socialist Belgrade and Sofia. European Planning Studies, 26(7), 1389–1412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1465530

- SOPA.bg (2009). General comment on the comprehensive development plan of the municipality of Sofia [In Bulgarian: ОБЩО СТАНОВИЩЕ ЗА ОУП НА ОБЩИНА ВАРНА]. Retrieved October 30, 2009, from http://www.sopa.bg/request.php?1696

- Stanilov, K. (2007). The post-socialist city: Urban form and space transformations in central and Eastern Europe after socialism. Springer.

- Tinbergen, J. (1964). Central planning. Yale University Press.

- Tsenkova, S. & Nedovic-Budic, Z. (Eds.) (2006). The urban mosaic of post-socialist Europe: Space. Institutions and Policy. Physica-Verlag.