ABSTRACT

Public libraries are more than information providers; they increasingly serve as key social infrastructures. Financial pressures, decreasing membership and digitalisation require libraries to reinvent themselves as primarily spaces of an encounter. This paper focuses on the retooling of small public libraries in the Netherlands as social infrastructure and the formal and informal library practices (‘infrastructuring’) that are required for the library to function as space of encounter. The paper reports on an in-depth, single-case study based on 15 years of volunteering, participant observations, repeated interviews with staff and informal conversations with patrons. By examining the multi-purposed features of a single site, we illustrate how the library, as an exemplary public space, is being retooled by both staff and patrons. While encounters mostly seem to occur within rather than between groups, there are many meaningful acts of kindness between different people. Though the library is undeniably a social infrastructure, the paper also shows how difficult it is to document, let alone practice this social function.

Resumen

Las bibliotecas públicas son más que proveedoras de información; cada vez más sirven como infraestructuras sociales clave. Las presiones financieras, la disminución de la membresía y la digitalización exigen que las bibliotecas se reinventen a sí mismas como principalmente espacios de encuentro. Este artículo se centra en la remodelación de pequeñas bibliotecas públicas en los Países Bajos como infraestructura social y las prácticas bibliotecarias formales e informales (‘infraestructuración’) que se requieren para que la biblioteca funcione como espacio de encuentro. Informa sobre un estudio de caso en profundidad basado en 15 años de voluntariado, observaciones participantes, entrevistas repetidas con el personal y conversaciones informales con patrocinadores. Al examinar las características multipropósito de un solo sitio, ilustramos cómo la biblioteca, como espacio público ejemplar, está siendo remodelada tanto por el personal como por los usuarios. Si bien los encuentros parecen ocurrir principalmente dentro de los grupos y no entre ellos, hay muchos actos significativos de bondad entre diferentes personas. Aunque la biblioteca es indudablemente una infraestructura social, el artículo también muestra lo difícil que es documentar y practicar esta función social.

Résumé

Les bibliothèques municipales sont plus que de simples pourvoyeurs d’informations ; elles font de plus en plus fonction d’infrastructures sociales essentielles. Les pressions financières, la baisse du nombre d’adhérents et la numérisation forcent les bibliothèques à se réinventer et devenir essentiellement des espaces de rencontres. Cet article s’intéresse au rééquipement des petites bibliothèques municipales des Pays-Bas afin de les transformer en infrastructures sociales et aux pratiques formelles et informelles (« l’infrastructuration ») nécessaires pour qu’elles puissent fonctionner en tant qu’espaces de rencontres. Il traite de manière détaillée d’une seule étude de cas, en se fondant sur quinze ans de bénévolat, des observations de participants, des entretiens répétés avec le personnel et des conversations informelles avec les utilisateurs. En examinant les caractéristiques polyvalentes d’un emplacement unique, nous illustrons la façon dont la bibliothèque, en tant qu’espace public emblématique, est rééquipée par son personnel autant que par ses utilisateurs. Tandis que les rencontres semblent se produire principalement au sein de groupes plutôt qu’entre eux, il y a beaucoup d’actes de gentillesse entre les gens. Bien que la bibliothèque soit sans aucun doute une infrastructure sociale, cet article démontre aussi à quel point il est difficile de documenter, si ce n’est de mettre en pratique, cette fonction sociale.

Introduction

‘To restore civil society, start with the library,’ sociologist Eric Klinenberg (Citation2018b) argues in the New York Times. He postulates that libraries have not become obsolete or irrelevant, but instead are being starved for resources and overburdened by visitors and activities. In other words, they are neglected at precisely the moment when they are most necessary. Libraries not only serve as repositories of newspapers, magazines and books facilitating the free exchange and formation of public opinion (Vårheim et al., Citation2019), but increasingly also as spaces of an encounter across cultural, ethnic, generational and social lines (Aabø et al., Citation2010; Audunson, Citation2005; Chen & Ke, Citation2017; Corble, Citation2019; EBLIDA, Citation2020; Engström & Eckerdal, Citation2017; Hodgetts et al., 2008; Peterson, Citation2017, Citation2021; Robinson, 2020; Smith, Citation2012; Williamson, Citation2020), providing access to networks, cultural capital and interpersonal care (Aabø & Audunson, Citation2012; Griffis & Johnson, Citation2014; Johnson, Citation2010; Leorke & Wyatt, Citation2019; Vårheim, Citation2014). Hence, Klinenberg (Citation2018b, emphasis added) concludes: ‘If we have any chance of rebuilding a better society, social infrastructure like the library is precisely what we need.’

The term social infrastructure refers to geographic spaces that play a crucial role in the social life of cities, such as parks, schools, community centres and also libraries (Latham & Layton, Citation2019, p. 2): ‘More than just fulfilling an instrumental need, they are sites where cities can be experienced as inclusive and welcoming.’ As such, libraries can also serve as ‘diagnostic windows in society’ (Mehta, Citation2010: 16) or ‘a barometer of place’ (Robinson, Citation2014: 13), telling bigger stories about the health of cities and nations, perhaps especially in times of crisis (Corble & Melik, Citation2021). Nevertheless, though extensively researched within library and information studies (see Vårheim et al., Citation2019 for an overview), with a few notable exceptions (e.g., Peterson, Citation2017, Citation2021), public libraries have rarely been examined as public spaces by social scientists (Robinson, 2020). Aptekar (Citation2019, p. 1217) therefore argues that ‘expanding the study of public libraries beyond the field of library and information studies is much needed to create a fuller portrait of contemporary city life.’ Vårheim et al. (Citation2019) concur that more empirical studies on libraries and their public sphere roles are needed, particularly research that moves beyond the Anglo-Scandinavian hegemony, and that provides insights into the ways in which libraries are responding to changes in terms of digitisation, aging and migration.

In this paper we aim to do exactly that, by critically assessing the retooling of small public libraries in the Netherlands as they shift from information providers towards becoming vital social infrastructures. We investigate to what extent the library serves as a public space where encounters between people with different social, economic, and cultural backgrounds potentially take place, but also question what being a social infrastructure actually entails. In other words, we do not take the socio-cultural role of the urban infrastructure of the library for granted, but rather try to look beyond the actual ‘taking-place’ of encounters within the library space (e.g., Aabø et al., Citation2010; Audunson, Citation2005; Hodgetts et al., 2008), and also highlight the practices of designing and staging such encounters (Wilson, Citation2017). Accordingly, we focus on the library as social infrastructure as well as the formal and informal library practices (or infrastructuring) that are required to retool the library as exemplary space of encounter.

Contemporary libraries increasingly offer a wide-range of ‘non-book-based services’, including art classes, homework assistance, language instruction, cultural events, craftwork, meditation and yoga classes (Barniskis, Citation2016; EBLIDA, Citation2020; Lenstra, Citation2017, Citation2019; Robinson, 2020). Arguably, this transition towards becoming a social infrastructure is what society needs, but also what is necessary for the library itself to avoid becoming extinct. Shrinking subsidies, changing demographics, decreasing membership and the rise of digital technologies all combine to force libraries to reinvent themselves: as community centres, innovation labs and makerspaces (Klinenberg, Citation2018a; Leorke & Wyatt, Citation2019; Norcup, Citation2017). The COVID-19 pandemic has further aggravated the precarious situation of many libraries and continues to trigger other library transformations (Corble & Melik, Citation2021; EBLIDA, Citation2020).

The Netherlands provides an illustrative case of the library in transition. Faced with massive cuts in financial support from the state, but also declining patronage in many localities, many libraries across the country have been forced to close down leaving a social void in many communities long accustomed to its presence (Council for Culture, Citation2020; Van Mil et al., Citation2019). At the same time, there is evidence of large libraries becoming the new urban ‘hotspots’, often part of multifunctional flagship projects, while smaller libraries – such as the one we studied – are showing themselves capable of retooling their roles as social infrastructures (Van Melik, Citation2020).

We proceed by combining insights from library and information studies (LIS) with social geographical literature on encounters and public space, to investigate how staff and patrons retool the library as a social infrastructure. Below, we first theorise the library as a social infrastructure. We then continue by introducing our methodology, based on a single-case study of a local library in a small town in the Netherlands, where one of the authors has volunteered for over 15 years. Drawing on three vignettes, we tease out three ways in which the public library is being retooled as a social infrastructure by both staff and patrons. Our findings illustrate how facilitating social encounters has become one of the library’s principal functions, though often in a ‘shared but customised’ way favouring specific rather than general interests. Reframed as community librarians, the roles and practices of staff also continue to evolve, with an increasing emphasis on emotional labour and communal engagement. Many meaningful encounters occur in the library, but as socio-economic circumstances continue to change, it remains an ongoing challenge to maintain and legitimise the library’s social value.

The library as social infrastructure

Once the exclusive domain of universities, or a private asset only the elite could enjoy, libraries have long been central to the planning of urban landscapes (Leorke & Wyatt, Citation2019). Indeed cities across the industrialised world provide access to public libraries, just as they do to schools, concert halls or green space. Libraries have instantiated all that is public in the best sense of the word: free and available to all at the point of entry, and offering a variety of free services whose ostensible purpose – chief among them unimpeded access to the printed word – is to serve the greater good. Barniskis (Citation2016, p. 104) observes: ‘libraries remain the least-mediated institutions in terms of the economic, political, religious, or pedagogical agendas, with an obligation to minimise the filters between people and the information they seek. Such open space is rare in our society.’ Libraries also are perhaps one of the last remaining spaces not dominated by corporate influence; as Smith (Citation2012) puts it: ‘the only thing left on the high street that doesn’t want either your soul or your wallet.’ Of course there are communal – usually non-profit – organisations working with local libraries to promote literacy and community involvement. But one is unlikely to see corporate logos prominently on display, or indeed profit-driven motives anywhere in a public library.

Moreover, access to the public library continues to be largely unhindered (Aptekar, Citation2019). Visitors are generally free to go about their business in myriad un-prescribed ways, at least insofar as they respect certain rules of conduct (Hodgetts et al., 2008). Funded and maintained by the (national, provincial or regional) state but especially local tax revenues, they are free and open to all (though some locations may require modest subscription fees to check out library materials). Libraries are also generally more inclusive than many other public spaces and, owing to the presence of trained staff, are generally oriented toward welcoming people from all backgrounds. These characteristics of being open, accessible and inclusive to all make libraries exemplary public spaces (Aabø & Audunson, Citation2012; Peterson, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2012).

As such, the library is not just a ‘Habermasian’ information infrastructure facilitating literacy (Vårheim et al., Citation2019) but also a vital form of social infrastructure that contributes to the social life of cities (Klinenberg, Citation2018a). In other words: they are not just lieux du livre (places of books), but also lieux du vivre (spaces of living) (EBLIDA, Citation2020, p. 22). Social infrastructures are ‘networks of spaces, facilities, institutions, and groups that create affordances for social connection’ (Latham & Layton, Citation2019, p. 3). Libraries can be regarded as a social infrastructure for the wide-range of ‘non-book-based services’ they offer, including homework assistance, voter registration and language instruction (Barniskis, Citation2016; EBLIDA, Citation2020).

In public libraries in the US and UK, these services also extend to aiding the homeless, many of whom benefit from the chance to meet up with friends or talk with library staff, or simply enjoy the heat or air-conditioning (Brewster, Citation2014; Gunderman & Stevens, Citation2015; Hodgetts et al., 2008). Some urban libraries even staff a full-time social worker to help patrons find appropriate forms of government assistance such as housing, job assistance and drug counselling (Dawson, Citation2014). Other population groups use libraries for a wide variety of pedagogical and literate activities (e.g., children’s story time, language instructions, computer classes, reading groups and book discussions) (Williamson, Citation2020), but also increasingly for social activities, such as knitting (Robinson, 2020), yoga, and fitness classes (Lenstra, Citation2017, Citation2019). So while libraries are perhaps best known for being quiet public spaces, these examples illustrate how many libraries in fact are a vibrant hub of social activity and interaction, facilitating the potential for sustained and enduring encounters.

As a social infrastructure, stimulating encounter has arguably become the library’s principal raison d’être. However, the encounter is ‘a conceptually charged construct that is worthy of sustained and critical attention’ (Wilson, Citation2017: 451). Encounters are often assumed to have positive effects, such as those described in Allport’s (Citation1954) ‘contact hypothesis’ or Pratt’s (Citation1991) ‘contact zone’. Both theories suggest that contact between different groups – labelled ‘rubbing along’ by Watson (Citation2006) – has the potential to reduce prejudice and promote social cohesion. Provided that certain facilitative conditions are met, encounters can certainly have a transformative capacity (Norcup, Citation2017). Wilson (Citation2017) therefore argues that encounters are not just any form of meeting, but interactions between differences that also have the potential to make a difference.

However, encounters with different others are by no means a guarantee of a positive outcome (Merry, Citation2013; Valentine, Citation2008; Van Melik & Pijpers, Citation2017). Encounters in themselves can just as easily provoke discomfort, misunderstanding and even hostility. Accordingly, certain conditions conducive to favourable contact will need to be met, such as the recognition that others are worthy of respect, an openness to difference and a willingness to listen. Yet even when these conditions are met, it is notoriously difficult to scale these up beyond the encounters in question (Wilson, Citation2017). This is because encounters in public space are often fleeting, ephemeral, or unfocused (Goffman, Citation1963), resulting in ‘parallel lives’ (Spierings et al., Citation2016; Valentine, Citation2008) and merely ‘co-presence’ rather than ‘co-mingling’ (Goffman, Citation1963). Irrespective of one’s personal view, it is doubtless the case that encounters – including those in public libraries – can also be experienced negatively.

The outcome of social infrastructures in terms of their proposed encounters is therefore not a foregone conclusion. In addition to this disclaimer, it is also important to emphasise that public libraries’ role as social infrastructure does not evolve ‘naturally’, but needs to be actively performed by a network of stakeholders, including (local) governments, librarians and patrons. Encounters do not just spontaneously emerge, but are designed and staged to a certain extent (Wilson, Citation2017). Rivano Eckerdal (Citation2018) uses the term ‘librarising’ to describe the continued adaptation of libraries to changing circumstances, patron need and technological developments. They do so not just defensively in response to external threats or fiscal deficits, but also with aspirations to innovate and foster community life. This ongoing performance of ‘maintenance work’ including stimulating encounters could be labelled as ‘infrastructuring’ (Korn et al., Citation2019). Conceptualising the public library as a social infrastructure therefore requires not only researching it as a place of encounter, but also investigating the practices of infrastructuring performed to retool the library as a social infrastructure.

Methodology

Our empirical study is situated in a public library in a small town, near the City of Utrecht, almost exactly in the centre of the Netherlands. It is open 4 days/25,5 hours, per week. During opening hours, at least one paid staff member and one or two volunteers look after the library. Six of these opening hours are classified as self-service, illustrating what Engström and Eckerdal (Citation2017) regard as a popular trend of keeping libraries open beyond normal business hours. The studied library is part of a regional multidisciplinary organisation, including six libraries, a theatre, and an arts centre. It is located in a community centre, which also includes two primary schools, a day care centre, and a music school. It is positioned in close proximity to the town centre in a fairly homogenous (white, middle to upper class) environment.

The first author, Rianne, has been working as a volunteer at this library since 2004, developing close relationships with both staff and visitors. Although this long-term engagement started with a social rather than research objective in mind, it gradually evolved into a research project. For the first few years she volunteered on Saturdays (10 am to 2 pm), every other week. Due to other obligations, this is now reduced to one Saturday every 2 months, taking occasional extra shifts when needed. This paper is primarily based on her volunteering experiences in 2019, during which she had both formal and informal conversations with staff and patrons, and conducted participant observations (see ). However, as we aim to research how the library is retooled as a social infrastructure over time, we will also incorporate her earlier (2004–2018) and later (2020–2021) experiences of working at the library, briefly reflecting how COVID-19 has impacted the library.

Table 1. Overview of volunteering-as-fieldwork at library in 2019.

provides an overview of the fieldwork conducted at the library in 2019. Staff at the library consented to participating in the research. Rianne conducted about 30 hours of participant observations as a volunteer and acted as an observing participant in two social activities organised at the library (having informal conversations with 13 participants). Detailed fieldnotes were written at the end of each volunteering shift and attended activity, describing conversations with staff and visitors in a chronological manner. We also interviewed the library’s director and studied the library’s annual report of 2018 to investigate official policy plans.

Repeated interviews (in total 8) with the two managers Anne and Linda gave us an opportunity to investigate how they try to retool the library as social infrastructure through their daily practices. These interviews took place extemporaneously ‘on the job’ during the library’s opening hours. Such unstructured interviews, also known as informal conversational or ethnographic interviews, might be seen as ‘random’ and ‘nondirective’, but they can be very helpful in developing a better understanding of the respondent’s social reality without having a priori defined questions or hypotheses (Zhang & Wildemuth, Citation2017). We particularly valued the combination of having these repeated conversations while working alongside the managers, as this allowed us to compare their sayings and doings. A disadvantage is certainly that conversations could not be audiotaped and literal quotations are therefore limited. Nevertheless, detailed fieldnotes written after each conversation still provides rich qualitative data. In respect of the anonymity of the library and its staff and visitors, all names are pseudonyms.

We believe that this mix of research methods, facilitated by the researcher’s volunteering activities, provides an immersive, empirical overview of the reproduction of the library as a social infrastructure. Vårheim et al. (Citation2019, p. 96) demonstrate that library studies are often theoretically based, with only half of the publications providing empirical evidence. Surveys are a popular research method, questioning either patrons (Aabø et al., Citation2010; Chen & Ke, Citation2017) or professionals (Audunson & Evjen, Citation2017; Barniskis, Citation2016; Lenstra, Citation2017). Observing activities occurring in the library is also a common method, often in combination with patron interviews and/or policy analysis (e.g., Aabø & Audunson, Citation2012; Aptekar, Citation2019; Given & Leckie, Citation2003; Peterson, Citation2017). Both surveys and observations provide detailed information on patronage use, but little on the meaning of the library in the lives of people. This requires – as we have done – an extensive stay of the researcher ‘where the action’ is, for example, through volunteering. This is done relatively limited in library studies, with some notable exceptions (e.g., Aptekar, Citation2019; Williams, Citation2018).

Volunteering can result in rich descriptions of, and personal narratives about the social phenomenon under study, but of course the close relationship between the researcher and the researched also may result in a researcher’s bias (Corble, Citation2019). Moreover, the researcher’s presence may also influence the phenomena under observation. We tried to mitigate these hazards by having repeated conversations with staff from the studied library as well as research colleagues as a constant way of checking and balancing our analytical biases.

Another potential concern is that volunteer services are often being conducted at one or few locations, and as a result may be very idiosyncratic. Our single-case study might indeed not be representative for the entire Dutch library landscape, with central libraries in big cities transforming into new urban hotspots, while smaller branches in small to medium-sized towns and cities are struggling with decreasing funding and patronage (Van Mil et al., Citation2019). While most studies understandably focus their attention on large libraries as social infrastructures and showcases of pluralism and encounters with ‘otherness’ in multi-ethnic urban centres like Vancouver, Toronto, New York, Oslo, London, Glasgow, Sydney or Rotterdam (Aabø & Audunson, Citation2012; Aptekar, Citation2019; Given & Leckie, Citation2003; Johnson, Citation2010; Peterson, Citation2017, Citation2021; Robinson, 2020; Williamson, Citation2020), we believe our understanding of libraries as social infrastructures will be further enhanced if we also look at smaller libraries in ‘not-so-urban’, more homogenous, contexts. Here, encounters between difference do not necessarily occur along the lines of race or ethnicity, but rather along the lines of age, health and other personal characteristics. Our case study only represents this latter category. Be that as it may, we share the view of Yin (Citation2014), who argues that single cases are appropriate to analyse cases that are typical, revelatory and longitudinal. Indeed, it is precisely the paucity of such non-urban public libraries in the literature that we consider them more than worthy of investigation.

Three vignettes

Rianne started volunteering at her local library in 2004, when she was looking for opportunities to meet new people after moving to a suburban town of about 15,000 inhabitants. The manager at the time warned Rianne that she would not meet many people ‘of her own age’ (early twenties) in the library as both co-volunteers and visitors were (and still are) generally much older. Nevertheless, over the years her volunteering resulted in becoming acquainted with a large variety of visitors though most of these (intergenerational) encounters resulted in ‘fleeting’ or ‘unfocused’ interactions (Goffman, Citation1963) rather than lasting friendships, or meetings outside the physical confines of the library. Nevertheless, these fleeting relations were valuable, as recognising familiar faces from library visitors increased her feelings of belonging and being part of the local community (cf. Peterson, Citation2017; Williamson, Citation2020).

It was interesting to observe how Rianne’s goal to become a volunteer (i.e., to meet other people) eventually became the library’s main objective. The current manager calls this the transition ‘from a books library to a people’s library’ (Interview Anne), which echoes the official policies formulated in the Annual Report (2018). Over the years, Rianne witnessed how the library has changed from a predominantly silent place where one might browse through books or the newspaper, into a social infrastructure full of activities, such as I-pad courses for the elderly, storytelling for toddlers and weekly meetings of the local knitting club. This transition was further facilitated by the library’s move to a new community centre in 2016, allowing for more space for these social activities and encounters.

Gradually, these social activities became the library’s core business, rather than merely providing access to books and other sources of information. The Annual Report from 2018 indeed emphasises that the library aims ‘to enlarge the self-reliance and creativity of citizens.’ Below, we provide three empirical vignettes to illustrate the library as a social infrastructure. Though each vignette accurately describes an actual person, each also serves as a typology of sorts inasmuch as each profile also coincides with a ‘type’ of library user.

Anti-loneliness lunches

Since 2019, library staff organises a joint lunch meeting every Wednesday called ‘Guest at the table’ (GATT). Visitors bring their own food; coffee and tea are provided. Occasionally, a guest speaker gives a brief talk about a certain topic such as a particular hobby, expertise or journey, after which the group continues discussing the theme. As such, GATT shows resemblance to Tischgesellschaften (table societies), such as coffee houses where people meet to discuss issues of common interest (Vårheim et al., Citation2019). In case there is no guest, the visitors talk about the news or a topic specifically suggested by the staff: ‘we want to uplift the spirits’ (Interview Linda) and avoid the likelihood that visitors – almost all elderly and suffering from health problems – only talk about their physical problems.

On average, 6 to 14 people attend these lunch meetings. According to managers Anne and Linda, this small size is the activity’s strength; it results in people having real conversations instead of merely attending a lecture. With a larger number of visitors, ‘it would not be possible to create a sense of security and to give everyone the floor’ (Interview Linda). Interestingly, GATT is attended by relatively many men as opposed to other group activities in the library as well as the pool of volunteers, which – as is common in public libraries – are largely dominated by women (Norcup, Citation2017).

Bart is one of these male visitors of GATT. He frequently visits the library to read the newspaper and talk to people, including staff. On one occasion, he approached the information desk, asking Rianne ‘can I briefly discuss what happened today?’, after which he elucidated all of his activities in great detail. Bart is what Linda in one of our conversations defines as a ‘sender’; people who come to the library to share their stories at great length because they do not have other people to talk to. Bart in fact inspired Linda to set up the weekly lunch meetings, as this now offers the opportunity for people like him to also share their stories with other people. When Rianne attended one of the GATT lunches, the purpose and value of this social activity indeed became very clear:

There is no guest talking about a topic today, instead the group (6 participants) discusses all kinds of themes. I am amazed how well-read and informed they are; knowledgeable about current affairs but also literature classics. Bart immediately starts talking, about his visit to a museum and a particular writer he loves. It is difficult to follow his argumentation and to interrupt him; he seems happy he has someone to lecture to. After half an hour, another visitor finally takes over and expresses his amazement regarding Prince Andrew’s interview on his connections to Jeffrey Epstein. In the remainder of the lunch meeting, the group discusses themes as varied as sweating when lying, strikes in health care, and irritating voices in audiobooks. (Fieldnotes)

Organising such encounters within the library does not have the purpose of educating the visitors; according to the managers, the meetings are primarily intended to reduce loneliness although they are not officially framed and advertised as such. Visitors are mainly older and/or disabled people, often single or widowed and suffering from chronic loneliness. After each session, visitors can write down their experiences in a ‘guest book’. One participant wrote down how she explicitly came to meet other people. Therefore, GATT confirms the library’s potential as a social infrastructure to contribute to the well-being of people as ‘therapeutic landscape’ (Brewster, Citation2014), supporting mental health and reducing isolation (Barniskis, Citation2016).

Library as gateway

In addition to the weekly GATT launches, there are a variety of other activities held at the library, such as information sessions or consultation hours organised by the municipality, police or the Senior Activities Foundation about issues like dementia and digitalisation. A yoga teacher recently taught a short yoga class to toddlers linking easy physical exercises to stories in their picture books. Manager Linda emphasises that she wants to create the image that the library is available for such activities, by offering space and refreshments.

One frequent user is the local knitting club, which convenes every Wednesday morning for 1,5 hours in the library. Since its foundation in 2015, a club of about 10 elderly women assembles in the library; a phenomenon that can also be observed in libraries elsewhere (Robinson, 2020). The members do not need to pay rent, only a small contribution for coffee or tea. Rianne joined the knitting group during one of their meetings:

The club works diligently on all kinds of knitwear projects, while simultaneously having many conversations. Briefly interrupting her knitting, Rose proudly shows me a picture of herself volunteering as storyteller, a gift she had just received from the library managers. The picture and story-telling activity seem very important to her. She explains how she herself had learning difficulties in the past and that she had always wanted to engage with children, but never got the opportunity to do so in her private and professional life. The library managers asked the knitting group if someone would be interested in becoming a storyteller volunteer. Rose hesitated at first, but now expresses with tears in her eyes how happy she is being offered the opportunity to do what she had always wanted. (Fieldnotes)

Rose’s story illustrates how the library can empower its visitors in multiple ways, not only by providing access to information as often discussed in the literature (Ingraham, 2015), but by becoming a ‘gateway to valuable forms of sociality’ (Robinson, 2020, p. 13), allowing patrons to develop certain skills and self-confidence, like the capacity and courage to read stories. For Rose, this library activity therefore not only provides an opportunity for intergenerational encounters (Vanderbeck, Citation2007), but also for individual empowerment (Norcup, Citation2017).

Library as learning space

We have seen how the library functions as a therapeutic landscape of (intergenerational) encounters and individual empowerment for vulnerable, often elderly population groups. However, the library managers also want to cater to other user groups, such as young people. Anne started working at the library in 2017 as ‘employer visitor service’ (medewerker publieksservice), which implies she runs the library during opening hours (together with volunteers), but also arranges all kinds of activities for youth, such as storytelling sessions and ‘scavenger hunts’ during the annual ‘Children’s books week’.

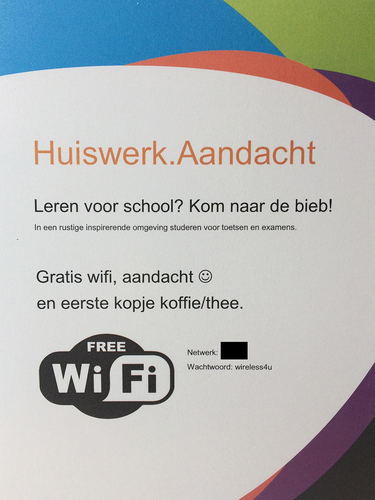

Following the library’s mission to increase visitors’ self-reliance (Interview director), Anne invests a lot of time and ‘instructional work’ (Julien & Genuis, Citation2009) to turn the library into a space for learning (Norcup, Citation2017). Posters in the library – designed by Anne – aim to attract youth (see ): ‘Studying for school? Come to the library! Free Wi-Fi, attention ![]() and a first cup of coffee/tea.’ During one of our repeated interviews, she describes how at one occasion she could even assume the role of economics teacher – for which she is actually trained:

and a first cup of coffee/tea.’ During one of our repeated interviews, she describes how at one occasion she could even assume the role of economics teacher – for which she is actually trained:

Over our coffee break, Anne relates an anecdote about a teenager who recently came to the library to study for her economics exam. In addition to providing Wi-Fi and a cup of refreshment, Anne could also help this particular student with the content of her exam material. After the exam, the teenager returned to the library to proudly share her results. Anne exactly recalls her grade: ‘a 8,4 [on a scale of 1 to 10]!, she says with a big smile. (Fieldnotes)

Figure 1. Offering more than a quiet place to study: Poster in library announcing ‘Free wifi, attention and a first cup of coffee/tea’. Source: Anne.

This anecdote illustrates that Anne’s job is highly relational and requires emotional labour (Julien & Genuis, Citation2009), or in Anne’s own words: ‘simply being a human, and caring like a mother’ (Interview Anne). This resonates with Barniskis (Citation2016, p. 114, emphasis added) findings on reframing roles of librarians, whose ‘duties [are] shifting from information experts, or collectors and organizers of materials, to community advocates, teachers, and as match-makers for people to meet one another and new ideas.’ Anne and Linda also closely collaborate with youth workers operating in town, for example, to organise monthly activities at the library for ‘loitering youth’.

However, despite the inviting posters, it is rare to see teenagers studying in the library. In contrast, many gamers, often boys, come to the library to play games at one of the four computers. Staff and volunteers often have to be the stereotypical ‘shushing librarian’ (Given & Leckie, Citation2003, p. 381) and ask them to lower their voices in the frenzied socialising of their gaming. However, instead of interpreting this as a problem, Anne tried to find a solution to accommodate both these gamers and other visitors. She did not want to ask the boys to leave, as she hopes that ‘being surrounded by books will eventually turn them into enthusiastic readers’ (Interview Anne). Although this hope might seem both quaint and naïve, Barron (Citation2021) confirms that spaces like the library can be meaningful throughout people’s life-courses, and that pleasant experiences or associations in the past can mediate positive and active engagements with that place in the future.

Therefore, Anne invited the gaming youth to jointly brainstorm about ways to reduce possible nuisance to other visitors. Together, they formulated some ‘codes of conduct’, including the use of a registration list, a maximum duration of 30 minutes, and a maximum of two children behind each computer. Being involved in setting the rules made the children both more familiar and compliant with the rules. When one of them came to sign the registration list during one of the Rianne’s volunteering shifts, he even proudly announced: ‘I made these rules’ (Fieldnotes). This example shows how the library is not just co-used but also co-produced, and that it indeed serves as space for learning, not just by offering access to books or study places, but by simply offering a listening ear.

Retooling the library

The three vignettes illustrate how the studied library has been retooled into ‘a place of encounter where people can enter without any obligations, conditions or thresholds to develop themselves […] of course people still go to the library to change books, but that is a moment of social encounter too’, as the Annual Report stipulates. However, we need to carefully assess this transition from information to social infrastructure as it comes with a number of challenges. Below we highlight three.

Customised inclusion

The library has the potential to facilitate meaningful encounters with unfamiliar others, where ‘meaningful’ implies sustained and enduring contact with different others from diverse backgrounds (Robinson, 2020). Even in a small, fairly homogenous Dutch town, the library indeed serves as a social infrastructure of great importance serving a diverse public ranging from lonely elderly individuals, to women who enjoy knitting together (Robinson, 2020), to studying teens and gaming youth. Patrons of our library mostly differ in generational terms, with the majority of visitors being either children or older people – providing the possibility for intergenerational contact (Vanderbeck, Citation2007). In many ways the library is inviting and inclusive (Peterson, Citation2017): a shared public space, not limited to paying members, that opens up opportunities to meet, interact, learn from one another and build alliances, as the GATT initiative illustrates.

However, it is probably not helpful to lean too heavily on modal auxiliary verbs such as might or could, let alone to romanticise libraries in this way. Our observations reveal more ‘co-presence’ than ‘co-mingling’, with different user groups seemingly having little focused interaction. This results in a paradox of ‘shared but customised’ public space favouring specific rather than general interests: doing homework, gaming, knitting, or simply reading the newspaper. These different actors assembling at the library also have very different interests and agendas. When certain groups ‘occupy’ the library, which Brown describes as the bodily ‘taking’ of space’ (Brown, Citation2012, p. 816), this potentially hampers others from using it, or could result in conflicts over use, like the knitting club inhabiting part of the library on Wednesday mornings, or the noisy gamers potentially irritating those trying to study.

Over the years the library in our study most definitely became more ‘noisy’, with sometimes-animated conversations during lunch meetings and at the computer consoles, in addition to regular audible conversations between staff, volunteers and visitors. As such, our library departs from other library studies, which – perhaps stereotypically – depict them as quiet spaces (Chen & Ke, Citation2017; Given & Leckie, Citation2003; Peterson, Citation2017), where ‘talking can take place, and certainly does, [but] it is not the main activity’ (Aabø & Audunson, Citation2012, p. 148). In our studied library silence has become the exception rather than the norm.

According to the library’s director this mix of users and increased activity calls upon the staff ‘to continually reconsider, renegotiate and reimagine what the library space ought to be’ (Interview director). Yet it is important to remember that even this level of vigilance will not produce completely satisfying outcomes for everyone, given the variety of ways in which the library means different things to different people. As social infrastructure, the library might therefore not cater to everyone equally. In our view, this does not disqualify it as an exemplary public space; notwithstanding their image as being open and accessible to all, no public institution will completely succeed in meeting the needs of everyone.

Reframing librarian roles

Retooling the library from information to social infrastructure also implies changing ‘librarising’ or ‘infrastructuring’ practices concerning how the library is best organised. The two managers – Anne and Linda – have completely different tasks compared to the manager 15 years earlier. Anne’s vignette illustrates that she performs an increasing amount of emotional labour (Julien & Genuis, Citation2009), instead of merely being an information provider. This includes taking time to talk to vulnerable patrons like Bart, organising social activities such as GATT, and collaborating with other (care) organisations. As such, Anne and Linda mostly act as social workers, although they are not trained as such, and officially, do not offer care. Their role is only ‘to refer people with problems like loneliness to other (care) organisations’ (Interview Linda). Anne is currently taking a course entitled ‘community librarian’, but this is not comparable to the profession of social work.

Moreover, these social activities can only be performed if the managers have time to do so and are not completely occupied with the daily management, including the tedium of shelving books and other materials. The latter is currently performed by a pool of 13 volunteers, who are very important for the library’s functioning, as also emphasised in the Annual Report: ‘they [the volunteers] are very important for our staff because they [staff] can realise all the projects that we try to initiate. That would not be possible if you have to hire professionals!’ Yet, this dependency on volunteers is a precarious situation that might very well decrease in the future: ‘the question is – with rising pension ages – [whether] there will be enough volunteers in the future to support all of our [social] activities.’ Without this pool of volunteers, permanent staff have only limited options to do the infrastructuring work required to retool the library as a space of care and community.

In addition, without wishing to downplay the library’s social activities, its continued transformation in becoming a vital piece of the social infrastructure should be seen against the background of broader changes in today’s neoliberal society, in which responsibilities for, but also expressions of, care are constantly shifting. As (elder) care in general becomes more privatised and hence difficult to access, the library increasingly is becoming a place of refuge and community for vulnerable people, of whom the elderly are but one obvious example. Aptekar (Citation2019, p. 1205) accentuates this point: ‘while themselves under assault, libraries often compensate for the decline of other social services.’ In one of the interviews, Linda also expressed some frustration that the library is only financed to organise activities for ‘stumpers’ (zielenpoten), and believes it should organise more than lunch meetings and knitting activities in order to truly function as a social infrastructure for the entire community.

Performance measurements

Neoliberal pressures certainly play an important role in the library’s performance as social infrastructure (Corble, Citation2019; Klinenberg, Citation2018a). Ever since Rianne started working as a volunteer in 2004, she has been hearing warnings that the library would cease to exist in ten years’ time. This sense of impending doom was not entirely unwarranted; the two other library branches in town were forced to close their doors. Since the new ‘library law’ of 2015, responsibility for funding and managing libraries has shifted from the national to municipal level (Van Mil et al., Citation2019). According to the interviewed director, about 80% of the library’s revenue is derived from municipal subsidies; the remaining 20% comes from membership fees. Since the number of paying members (exempting children and youth) is declining – both at our local library and nationally (Van Mil et al., Citation2019) – libraries are becoming increasingly reliant on government subsidies, and ‘forced to demonstrate their value to the public to earn the financial and intellectual support’ (Chen & Ke, Citation2017, pp. 45–6).

However, it is difficult to demonstrate and legitimise the social value of the library beyond its assumed role as an information infrastructure. As Barniskis (Citation2016, p. 1150) observes, ‘the role of the library as a provider of media still holds significantly more weight, in terms of dollars spent today, than the provision of creative spaces and programs.’ The changing purpose of the library is stressed in the Annual Report, but the management still struggles with how to account for these less tangible assets. The report uses a number of performance measures to outline the library’s activities (see ). By not only stressing membership and item check-outs but also (the growth of) the number of visitors and activities, it becomes clear that the library is more than an information infrastructure only used by members.

Table 2. Metrics in the annual report assessing the library’s functionings.

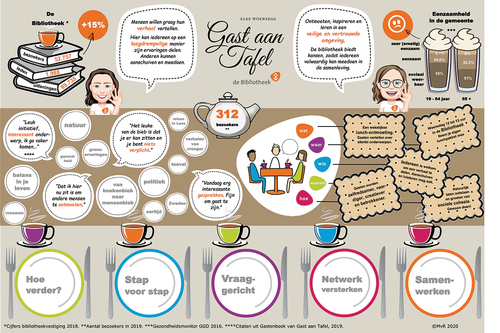

Nevertheless, the real impact that mental comfort and a sense of community offer cannot be reflected in the official annual reports to the government, whose assessment leans almost exclusively on quantitative measures (Lenstra, Citation2017). In our library, Anne and Linda have therefore started using the guestbook circulating at the end of each GATT meeting as a way to collect visitor experiences. Linda also developed an infographic in which she combines quotes from the guestbook with quantitative data, to visualise the added value of this activity (see ). Nicolini (Citation2007) describes this as ‘trails of accountability’, where the infographic, guestbook notes and tables in the annual report are used to legitimise new infrastructuring practices in an organisationin this case, organising social activities. Turning the library into a social infrastructure hence not only requires staff to increasingly perform emotional labour (Julien & Genuis, Citation2009) but also to become bookkeepers of social activity.

[ and about here]

Conclusions

Public libraries are social infrastructures that contribute something important to public life (Klinenberg, Citation2018a; Latham & Layton, Citation2019; Robinson, 2020; Van Melik, Citation2020). Not only do they provide access to information, increasingly they also attend to social capital and care. As such, they offer possibilities for meaningful encounters with different others (Peterson, Citation2017, Citation2021). In contrast to previous studies focussing on libraries in multi-ethnic metropolises, we have investigated the different kinds of encounters occurring in a small, suburban library in a more homogenous (white, middle class) context, and how these are retooled by both staff and patrons. This active process of performing as a social infrastructure can be labelled as ‘librarising’ (Rivano Eckerdal, Citation2018) or ‘infrastructuring’ (Korn et al., Citation2019) the library.

Our findings show that a variety of patrons find their way to the library, but seemingly interact within their own bubbles. Gamers ordinarily seek out gamers, knitters typically seek out knitters, and elderly patrons, too, are more likely to assuage their loneliness in the company of similar others. The studied library is also very much of a gendered space, largely dominated by women, at least in terms of staff and volunteers – with the exception of the GATT lunches. According to De Backer , this dearth of interaction between groups is ‘not necessarily a negative thing, but rather an expression of the indifference to diversity that is in fact rather typical for public space’ (De Backer, Citation2021, p. 496) Truly serving as a social infrastructure and accommodating different activities and users is therefore a complex – and perhaps even impossible – endeavour.

Yet while we observe separate groups with seemingly limited connections between them, there is certainly also evidence of meaningful encounters across or between difference. Rose’s vignette illustrates how (intergenerational) contacts in the library have provided her with moments of sociality, but also helped her develop skills and self-confidence. Similarly, the GATT lunches facilitate important encounters between the older visitors, on the one hand, and invited guests and staff on the other, which help the former to bridge ‘empty moments’ during the day (cf. Van Melik & Pijpers, Citation2017). The example of the GATT group willingly listening to Bart’s stories for more than half an hour illustrates the small acts of respect and openness to difference that occur within the library. Encounters between difference therefore not only occur along lines of race or ethnicity but also along lines of age, health or other personal characteristics (cf. Peterson,).

In short, the importance of the library as a social infrastructure is undeniable, but our study also suggests that the actual ‘taking-place’ of meaningful encounters is difficult to arrange (or to ‘infrastructure’) in public spaces like the library, despite the considerable emotional labour invested by staff and volunteers (Julien & Genuis, Citation2009). Moreover, the true value of social activities is difficult to quantify and document, let alone to practice with ever shrinking budgets. However, the social value of libraries is increasingly acknowledged, especially when many of them were closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic – libraries continue to face challenges to communicate and legitimate their indispensable social impact.

The COVID-19 crisis has and will continue to affect the public library as social infrastructure. The pandemic has resulted in many libraries – including our case – being temporarily closed, only to be reopened under strict regulation, often only allowing certain activities (borrowing books, solitary studying) or a limited number of patrons (members only), and prohibiting most if not all social activities (Corble & Melik, Citation2021). Consequently, library services were being stripped back to the bare functional minimum of ‘click-and-collect’, or in the words of manager Linda: ‘back to being a book-borrow-factory’ (Interview Linda). It is very likely that some of the social activities that were organised before the pandemic, such as GATT, will cease to exist even after social restrictions are lifted. The knitting club had already dissolved in the course of 2020, after the fieldwork was finished. Norcup (Citation2017) illustrates the difficulties of maintaining such social activities in the long run under ‘normal’ circumstances, let alone in times of a pandemic. In a similar vein, librarians’ infrastructuring practices have changed from organising lunch meetings and helping with homework to sterilising baskets and offering online assistance (Corble & Melik, Citation2021).

On the other hand, if the pandemic has taught us anything, it is that we so desperately need robust public institutions, and not only in the domain of public health. Our study has demonstrated how times of (economic) crisis have led not to the obsolescence of a revered public institution, but rather to calls for its transformation: whether it be redevising the roles librarians are called upon to play, or the performance assessments used to ‘measure’ the social utility of the public library in an age of inexorable state divestments.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Anne and Linda, the library director and all patrons participating in this research for sharing their time and stories.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aabø, S., & Audunson, R. (2012). Use of library space and the library as place. Library & Information Science Research, 34(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2011.06.002

- Aabø, S., Audunson, R., & Vårheim, A. (2010). How do public libraries function as meeting places? Library & Information Science Research, 32(1), 16–26.

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Aptekar, S. (2019). The public library as resistive space in the neoliberal city. City & Community, 18(4), 1203–1219.

- Audunson, R. (2005). The public library as a meeting-place in a multicultural and digital context: The necessity of low-intensive meeting-places. Journal of Documentation, 61(3), 429–441.

- Audunson, R., & Evjen, S. (2017). The public library: An arena for an enlightened and rational public sphere? The case of Norway. Information Research, 22(1), 1–13.

- Barniskis, S. C. (2016). Access and express: Professional perspectives on public library makerspaces and intellectual freedom. Public Library Quarterly, 35(2), 103–125.

- Barron, A. (2021). More-than-representational approaches to the life-course. Social and Cultural Geography. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019

- Brewster, L. (2014). The public library as therapeutic landscape: A qualitative case study. Health & Place, 26, 94–99.

- Brown, K. M. (2012). Sharing public space across difference: Attunement and the contested burdens of choreographing encounter. Social and Cultural Geography, 13(7), 801–820.

- Chen, T., & Ke, H. (2017). Public library as a place and breeding ground of social capital: A case of Singang Library. Malaysian Journal of Library and Information Science, 22(1), 45–58.

- Corble, A. (2019). The death and life of English public libraries: Infrastructural practices and value in a time of crisis. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London. http://research.gold.ac.uk/26145/ .

- Corble, A., & Melik, R. V. (2021). Public libraries in crises: Between spaces of care and information infrastructures. In R. Van Melik, P. Filion, & B. Doucet (Eds.), Global reflections on COVID-19 and urban inequalities: Public space and mobility (pp. 119–129). Bristol University Press.

- Council for Culture (2020). Bibliotheekstelsel staat onder druk. https://www.raadvoorcultuur.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/02/10/bibliotheekstelsel-staat-onder-druk. Accessed February 21, 2020.

- Dawson, R. (2014). The public library: A photographic essay. Princeton Architectural Press.

- De Backer, M. (2021). “Being different together” in public space: Young people, everyday cosmopolitanism and parochial atmospheres. Social and Cultural Geography. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019

- EBLIDA (2020). Think the unthinkable: A post COVID-19 European library agenda meeting sustainable development goals (2021-2027). http://www.eblida.org/Documents/Think_the_unthinkable_a_post_Covid-19_European_Library_Agenda.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Engström, L., & Eckerdal, J. (2017). In-between strengthened accessibility and economic demands: Analysing self-service libraries from a user perspective. Journal of Documentation, 73(1), 145–159.

- Given, L. M., & Leckie, G. J. (2003). ‘Sweeping’ the library: Mapping the social activity space of the public library. Library & Information Science Research, 25(4), 365–385.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Behavior in public places: Notes on the social organization of gatherings. The Free Press.

- Griffis, M. R., & Johnson, C. A. (2014). Social capital and inclusion in rural public libraries: A qualitative approach. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 46(2), 96–109.

- Gunderman, R., & Stevens, D. C. (2015). Libraries on the front lines of the homelessness crisis in the United States. http://theconversation.com/libraries-on-the-front-lines-of-the-homelessness-crisis-in-the-united-states-44453. Accessed 14 November, 2019.

- Hodgetts, D., Stolte, O., Chamberlain, K., Radley, A., Nikora, L., Nabalarua, E., Groot, S., & Ingraham, C. (2015). Libraries and their publics: Rhetorics of the public library. Rhetoric Review, 34(2), 147–163.

- Johnson, C. A. (2010). Do public libraries contribute to social capital? A preliminary investigation into the relationship. Library & Information Science Research, 32(2), 147–155.

- Julien, H., & Genuis, S. K. (2009). Emotional labour in librarians’ instructional work. Journal of Documentation, 65(6), 926–937.

- Klinenberg, E. (2018a). Palaces for the people: How to build a more equal and united society. The Bodley Head.

- Klinenberg, E. (2018b). To restore civil society, start with the library. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/08/opinion/sunday/civil-society-library.html Accessed 14 November, 2019.

- Korn, M. Reißmann, W., Röhl, T., Sittler, D. (2019). Infrastructuring publics. Springer VS

- Latham, A., & Layton, J. (2019). Social infrastructure and the public life of cities: Studying urban sociality and public spaces. Geography Compass. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12444

- Lenstra, N. (2017). Movement-based programs in U.S. and Canadian public libraries: Evidence of impacts from an exploratory survey. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 12(4), 214–232.

- Lenstra, N. (2019). Yoga at the public library: An exploratory survey of Canadian and

- Leorke, D., & Wyatt, D. (2019). Public libraries in the smart city. Palgrave.

- Mehta, A. (2010). Overdue, returned, and missing: The changing stories of Boston’s Chinatown branch library. Doctoral thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Merry, M. S. (2013). Equality, citizenship and segregation. Palgrave.

- Nicolini, D. (2007). Stretching out and expanding work practices in time and space: The case of telemedicine. Human Relations, 60(6), 889–920.

- Norcup, J. (2017). ‘Educate a woman and you educate a generation’: Performing geographies of learning, the public library and a pre-school parents’ book club. Performance Research, 22(1), 67–74.

- Peterson, M. (2017). Living with difference in hyper-diverse areas: How important are encounters in semi-public spaces? Social and Cultural Geography, 18(8), 1067–1085.

- Peterson, M. (2021). Encountering each other in Glasgow: Spaces of intersecting lives in contemporary Scotland. Tijdschrift Door Sociale En Economische Geografie, 112(2), 150–163.

- Pratt, M. (1991). Arts of the contact zone. Profession 33–40.

- Rivano Eckerdal, J. (2018). Equipped for resistance: An agonistic conceptualization of the public library as a verb. Journal of the Association of Information Science and Technology, 69(12), 1405–1413.

- Robinson, K. (2014). An everyday public? Placing public libraries in London and Berlin.

- Smith, Z. (2012). The North West London blues. https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2012/06/02/north-west-london-blues/ Accessed 11

- Spierings, B., Van Melik, R., & Van Aalst, I. (2016). Parallel lives on the plaza: Young women of immigrant descent and their feelings of social comfort and control on Rotterdam’s Schouwburgplein. Space and Culture, 19(2), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331215620994

- Valentine, G. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133308089372

- Van Melik, R. (2020). Van boekenbieb naar volkspaleis [From library of books to palace for the people]. Geografie, 29(3), 22–24.

- Van Melik, R., & Pijpers, R. (2017). Older people’s self-selected spaces of encounter in urban aging environments in the Netherlands. City & Community, 16(3), 284–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12246

- Van Mil, B., Mulder, J., Uyterlinde, F., Goes, M., & Koning, R. (2019). Evaluatie Wet stelsel openbare bibliotheekvoorzieningen. KWINK groep.

- Vanderbeck, R. (2007). Intergenerational geographies: Age relations, segregation and re- engagements. Geography Compass, 1(2), 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00012.x

- Vårheim, A. (2014). Trust in libraries and trust in most people: Social capital creation in the public library. Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 84(3), 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1086/676487

- Vårheim, A., Skare, R., & Lenstra, N. (2019). Examining libraries as public sphere institutions: Mapping questions, methods, theories, findings and research gaps. Library & Information Science Research, 41(2), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2019.04.001

- Watson, S. (2006). City publics: The (dis)enchantments of urban encounters. Routledge.

- Williams, M. J. (2018). Urban commons are more-than-property. Geographical Research, 56(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12262

- Williamson, R. (2020). Learning to belong: Ordinary pedagogies of civic belonging in a multicultural public library. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 41(5), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2020.1806801

- Wilson, H. F. (2017). On geographies and encounter: Bodies, borders, and difference. Progress in Human Geography, 41(4), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516645958

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

- Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. M. (2017). Unstructured interviews. In B. M. Wildemuth (Ed.), Applications of social research to questions in information and library science (pp. 239–247). Libraries Unlimited.